Perhaps the world will end at the kitchen table, while we are laughing and crying, eating of the last sweet bite.Footnote 1

The occasion and setting of dining are among the enduring features of Classical urban life, often mentioned by writers and documented by excavated houses and their material furnishings. The popularity of large, prominently situated residential spaces – rectangular or apsidal in plan, often high-ceilinged, with wide doorways, paved floors, and painted walls – attests the spread of Roman traditions of reception to all parts of the Later Empire. Equally distinctive are the accessories of staged hospitality, particularly the stone tabletops that occupied a central place at formal meals. Most of these flat surfaces were cut of fine marble to circular or lunate sigma shape; stood on masonry, metal, or wooden supports; and were surrounded by a semicircular couch, benches, or other kinds of seating.Footnote 2 Despite their importance in Late Antiquity, these specialized household objects today are known mainly by scattered fragments, sometimes more or less whole but usually much less so, and not often found in their original setting.

The presence at Sardis of three substantially complete sigma tables is a noteworthy contribution to domestic archaeology, made more remarkable by their discovery in contexts of intended use. Considering these tables as a group means beginning with an introduction to the site and the houses where they were found during excavations spanning more than 50 years. The functional significance of each table emerges from an assessment of its architectural setting and appointments, and especially the kind of seating used with it. The tables themselves were important household assets that played different roles when moved among rooms within the home; their mobility and value, moreover, underscore the archaeological significance of their discovery in situ, in contexts of unforeseen destruction that were overlooked by later scavengers. In each case, the larger assemblage includes furnishings, glass, ceramic, and metal vessels, and coins that document the room's use at the moment of destruction in the early 7th c. CE. Comparison with artifacts from nearby spaces that saw continued activity establishes a sequence of destructive events – likely earthquakes – that were experienced across the site and to which local inhabitants tried to adjust their lives.

Conviviality and catastrophe

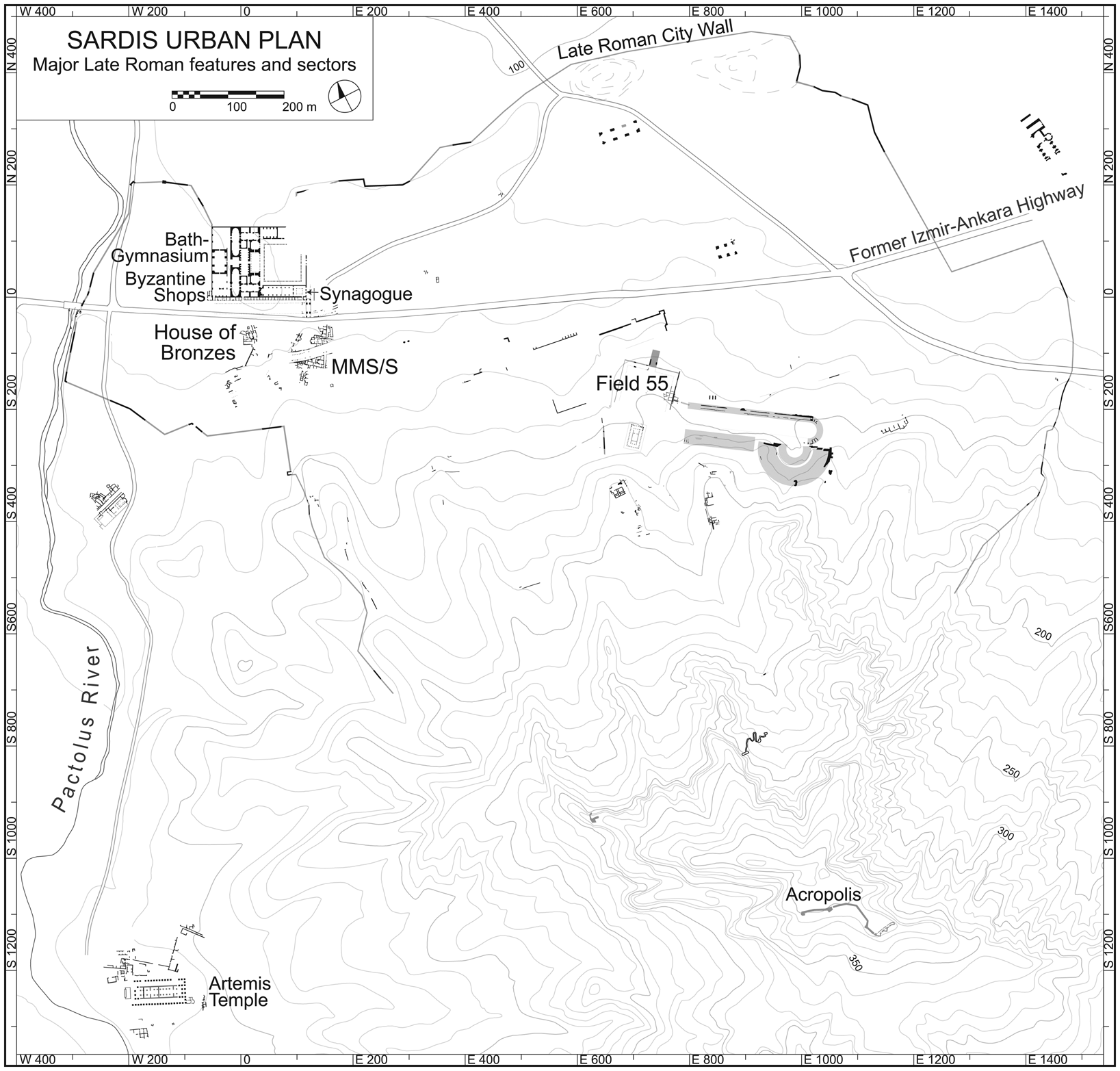

Sardis is the storied habitation center of ancient Lydia, dramatically situated below the Tmolan range some 90 km from the Aegean coast, and the subject of long-term study by the Harvard-Cornell expedition.Footnote 3 Excavations over 60 years have found Roman-era domestic structures across the site, from the acropolis slopes to the urban plain (Fig. 1). These range from modest extra-urban shelters and streetside shops to multi-room complexes of social pretense. Sustained work in the city's western quarter has explored a neighborhood that grew crowded with houses, beginning in the 2nd and 3rd c. CE and continuing through their alteration and abandonment in the 6th and 7th c. CE. Recent excavation near the center of the city has offered a broader perspective of these twilight days of settled life.Footnote 4

Fig. 1. Sardis, plan of site with major Late Roman features and sectors. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Within these houses, the discovery of nearly complete sigma tables distinguishes three rooms from other areas of domestic reception. The three tables were carved of marble and have a squarish lower body with horseshoe-shaped end. All were found on the floor, broken but substantially present, with articulated fragments showing that they shattered in place when they fell. Coins and pottery date to the late 6th and early 7th c. CE, suggesting that the houses were damaged and these rooms abandoned around the same time. In each case, the architectural setting, carved marble surface, and associated objects embody interrelated components of an independent household. Their final disposition preserves circumstances of lesser or greater intentionality on the part of their occupants and the social identity they sought to maintain.

The building known as the House of Bronzes (Sector HoB) was discovered during the early days of the current expedition, some 50 m south of the Bath–Gymnasium in western Sardis (see Fig. 1).Footnote 5 Identified features belong to a rambling residential complex of more than 20 spaces, which incorporated earlier tombs and other features in the 4th and 5th c. CE and which was occupied into the early 600s CE (Fig. 2). While the extent and design remain unclear, the building was probably approached from one or both of the colonnaded streets that ran north and east of the site. From these directions, a long corridor (7) and marble-paved court (15/18) converged near a small vestibule (8) connecting to a large, marble-paved room (5/13). A second large room with tile floor (6) stood on higher ground immediately to the west and was accessible by doorways from north and west, rather than through the damaged east wall. Both Room 5/13 and Room 6 seem to have been suitable places for welcoming visitors, perhaps at different times of day or year. Around these two reception spaces were several smaller rooms of uncertain purpose joined by irregular passages or open spaces. An enclosed yard (31) and possible cistern (38) formed the south edge of the complex.

Fig. 2. House of Bronzes, plan of Late Roman features. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Room 5/13 was the largest and most elaborate part of the House of Bronzes, and in its final form measured 5.5–6.0 m wide and over 10 m long. Thick walls enclosed a spacious interior paved with marble and opus sectile, and with large windows facing east. Opposite the north entrance was a broad alcove or exedra with a raised floor and narrow doorway at the back. Excavation in 1959 found about 40 fragments of a sigma table (identified as the “remains of two arch-like marble slabs”) lying near the front of the alcove (Fig. 3).Footnote 6 The white marble table was a little over 1 m square and had a plain band border surrounding the smooth central surface. A layer of ash and charcoal on the room's floor apparently represented the remains of a supporting wood frame for the table and timbers from the roof. A copper-alloy chandelier or polykandelon lay next to the table, together with an iron campstool and sword. Several late 6th-c. CE coins were found in nearby rooms, along with the copper-alloy objects that gave the complex its name and suggested its use for elite dining.

Fig. 3. House of Bronzes, Room 5/13, final occupation, looking northeast, 1959. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Slightly east of the House of Bronzes are the MMS sectors, where several houses were explored in the 1980s–90s (see Fig. 1). Development of the area in the late 4th and 5th c. CE saw construction of a broad colonnaded street and multiple houses that were occupied through the early or mid-7th c. CE.Footnote 7 In its final form, the MMS/S domus comprised a dozen ground-floor rooms with upper story, with a triangular plan bounded on two sides by the street and a narrow alley (Fig. 4). The presence of earlier features accounts for the unconventional layout and multiple entrances that offered direct access from street portico and alley.Footnote 8 The east half of the complex revolved around a large apsidal room (O), where a mosaic and marble floor, stucco walls, and adjoining spaces created an impressive site of formal presentation. The west half could be visited independently through an asymmetrical marble-paved court (E) with a sizable water tank in one corner. A covered portico along the east and south sides led to another large reception space (D), with a back doorway connecting to a smaller tile-paved room (A) and lower cellar (F).

Fig. 4. MMS/S, plan of Late Roman domus. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Both rooms O and D stand out as carefully designed places of welcome. The 5.4-m-wide apse of Room O provided an ornate stage for the domus owner to appear before his guests. By contrast, the layout of Room D suited occasions for convivial dining. Entered directly from the court, the rectangular space was about 10 m long and 5.25 m wide. The front half of the room was paved with carefully cut slabs of marble; the back half had a slightly raised surface of opus sectile and perforated terracotta tiles. Variegated paintings of marble revetment once covered the walls. Excavation in 1995 found a large sigma table broken into 10 pieces on the dining platform (Fig. 5).Footnote 9 The table was cut of gray marble with prominent veins, nearly 1.3 m square, and enclosed by a stepped border of two flat bands. Here, too, abundant ash and charcoal on the floor probably came from a supporting stand, furnishings, and superstructure. Coins, lamps, and pottery from Room D and adjoining spaces date the latest activity to the early 600s.

Fig. 5. MMS/S Room D, final occupation, looking northwest, 1995. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Field 55 lies over 600 m east of the MMS sectors and includes a terraced temple complex of Early Imperial date that was occupied by houses and shops in Late Antiquity (see Fig. 1). Among these were several taberna-like spaces that stood against the east terrace face and looked toward a nearby road. One room (A) and part of another (B) have been excavated in recent years (Fig. 6). Room A was sheltered on two sides by the terrace and a massive perpendicular wall, the collapse of which accounts for the excellent preservation of its contents. The room measured 4.5 × 6.5 m in plan and in its final form was entered only from its neighbor to the north, with a staircase in the southeast corner rising to an upper level. Excavation in 2015 found a white marble sigma table, shattered in many fragments but substantially complete, near the middle of the packed-earth floor (Fig. 7).Footnote 10 The table was about 1 m square and had a smooth surface enclosed by a flat band border. Ash and charcoal from the supporting frame, possible furniture, and superstructure covered the area. A copper-alloy polykandelon with fragments of small glass lamps lay on the marble surface. Local red-slipped pottery and two copper-alloy jugs found upright in the northwest corner belong to the room's final phase of use. Two other marble surfaces had been propped against the south wall: about half of a second sigma table with beaded border, and two halves of a complete circular platter or tray. A coin of Heraclius dates the room's unforeseen destruction to the early 7th c. CE.

Fig. 6. Field 55, plan of Late Roman rooms A and B. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Fig. 7. Field 55 Room A, excavation plan of final occupation, 2015. (Drawing by C. S. Alexander. © Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Invitation

Each of these three residential buildings preserves a distinct approach to organizing everyday space. Builders of the House of Bronzes and MMS/S domus used a number of familiar design elements, such as painted walls, arched windows, thresholds, floor coverings, and columns, to frame key sites of social interaction.Footnote 11 As in other affluent homes, the owners emphasized important rooms by their central location and large size, considered access, and decorated surfaces. Floors of marble slabs, opus sectile, and mosaic were laid on staggered levels to shape space and guide behavior, particularly on occasions of formal reception and dining. Despite differences in planning and ornament, both HoB Room 5/13 and MMS/S Room D were clearly intended to serve, inter alia, as centers of welcome and social display. Field 55 Room A offered a very different experience. This was a significantly smaller and more secluded space, an isolated retreat approached only through its unprepossessing neighbor, with a floor of packed earth, plain walls, and conspicuous stairway. The simple plan and spartan features recall many of the Byzantine Shops at Sardis and streetside tabernae in other cities, where long rows of nondescript units met basic needs of commerce and light industry as well as domestic shelter.Footnote 12

Spaces for reception and dining have been among the most discussed aspects of Roman houses, probably since the time of Vitruvius. Celebrated forms of banqueting in Late Antiquity are generally thought to have combined architecture, ornament, and furnishing in ways that expressed status hierarchies in the domestic sphere, from imperial palatium to provincial domus.Footnote 13 The traditional emphasis of the triclinium as a place of proper welcome was reinforced in the later 3rd and 4th c. CE by the fashion for languid reclining on a custom-built semicircular stibadium instead of three independent klinai. Reception rooms in a number of elite houses across the Empire were updated around the same time by the addition of an apse facing the entrance from a vestibule or peristyle. The resemblance of the curved apse to circular and lunate tables has been widely noted in identifying such rooms as specialized triclinia for stibadium dining, and, indeed, to be a logical development of the staging of privileged meals in Late Antiquity.Footnote 14 The connection appears most clearly in the few buildings that preserve foundations for both table and semicircular couch, which were sometimes combined with an extravagant aquatic display.Footnote 15 The combination of distinctive features – apse, sigma, stibadium – with images of banqueting in luxury and funerary art has shaped the traditional picture of status dining known from Sidonius Apollinaris (Epist. 1.11.10) and other authors.Footnote 16 How widely such routines were actually observed, however, is far from clear.

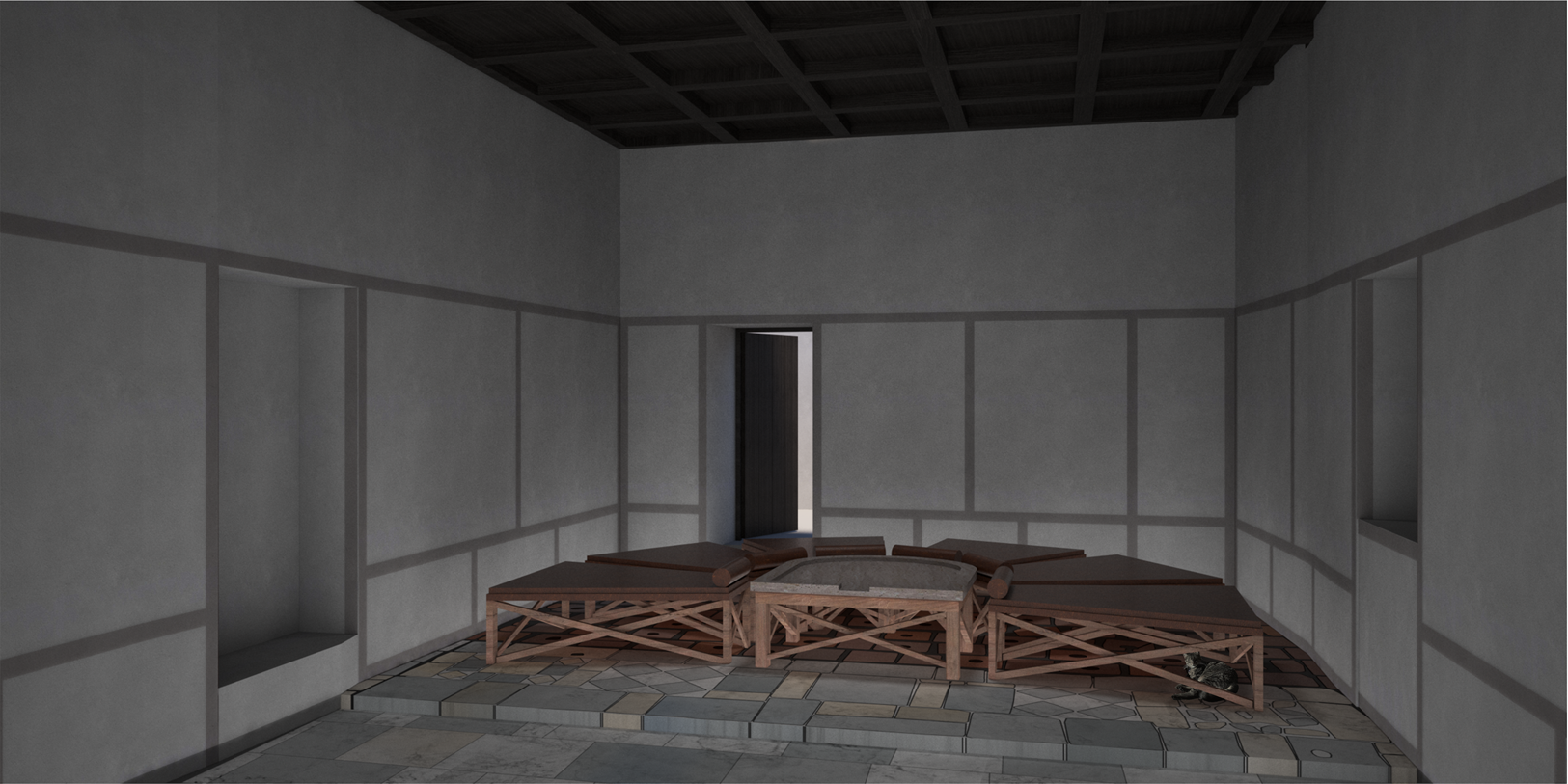

At Sardis, the physical arrangements of stibadium dining can be plausibly recognized in MMS/S Room D (Figs. 8a and 9). This was among the oldest parts of the domus and retained its essential 4th-c. CE features throughout its life. Differences in floor level and materials divided the 5.25-m-wide room into two parts. The 29 m2 entry-level expanse was paved with marble and comprised over half of the interior. The raised dining platform, with its floor of opus sectile and terracotta, covered an area of 23 m2, which seems just large enough to have accommodated a semicircular sectional couch for reclining at its large sigma table. Preserved foundations and floor mosaics at other sites establish the minimum width of a stibadium suitable for five to seven adults as about 4–4.5 m, with 1.4- to 1.5-m-long klinai set radially to a 1.25-m-wide table. Around this construction an additional 0.5–1.0 m of free space was needed for diners and servants to reach their places, making a total banqueting area of 18–24 m2 (Table 1).Footnote 17 The discovery in Room D of table fragments near the middle of the dining platform indicates that this kind of couch was intended to stand behind the opus-sectile border and atop the easily cleaned surface of perforated tiles.Footnote 18 The arrangement for six diners proposed here draws on the 4th-c. CE account of Ausonius.Footnote 19 It is also possible that by the 6th c. CE other forms of seating were being used.

Fig. 8. Distribution of table fragments (shaded area) and restored location with conjectured seating in (a) MMS/S Room D; (b) House of Bronzes Room 5/13; (c) Field 55 Room A. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Fig. 9. MMS/S Room D, reconstruction with table and stibadium on raised dining platform, looking west. (Digital rendering by Sheng Zhao. © Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Table 1. Rooms with substantially complete sigma tables mentioned in text and notes

The raised alcove of HoB Room 5/13 presented a similarly impressive but more challenging setting (Figs. 8b and 10). The main part of the room was paved with marble and opus sectile, with a surface of over 40 m2 representing 80% of the interior. The raised polygonal alcove was set off by flanking piers but was no more than 3 m deep, and so enclosed an awkwardly shaped area of only 10–12 m2. The table would have stood just behind these piers, near the center of the alcove. Without enough space to recline, diners would have sat upright on benches (bisellia) or more likely on folding stools (sellae). The iron frame of one such stool remained on the paved floor; altogether, 10 examples have been found at Sardis, with seat widths ranging from 0.33 to 0.44 m.Footnote 20 Standing about 0.5 m high and arranged at regular intervals, six sellae could have comfortably gathered diners along the 2.4-m-long curved edge of the HoB table. Similar limitations of space appear in nearby houses at sector MMS, where three apses measuring 3.5–3.6 m wide enclosed areas of only 8–10 m2. All of these rooms would have offered an adaptable setting for domestic reception and occasional stage for patron and guests to dine while seated before an invited crowd.Footnote 21

Fig. 10. House of Bronzes Room 5/13, reconstruction with table and sellae in alcove, looking south. (Digital rendering by Sheng Zhao. © Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Field 55 Room A stood apart from these showcases of transactional hospitality (Fig. 8c). The streetside setting, modest size, and functional design belonged to a level of urban life that centered on small-scale agriculture, craft, and commerce.Footnote 22 Similarities with the Byzantine Shops suggest that Room A and its largely unexcavated neighbor may have constituted an independent dwelling, with household activities concentrated on the ground floor, and sleeping quarters and storage on a higher level. The 29-m2 ground-floor area most closely resembles shops E1 and E6, the final arrangement of which included the adjoining rooms E2 and E7. A greater degree of privacy might be expected in those spaces (Room A, shops E1a and E6) that lay farther from the streetside entrance, yet fixtures and artifacts in all three units imply a mix of domestic activities.Footnote 23 The table in Room A probably stood near the middle of the space, about 1.7 m from the north, west, and south walls, and with its straight edge facing the stairs and doorway from Room B. Lacking space or occasion for a traditional stibadium, occupants would have sat on benches or stools around this focus of their domestic world.

The final occupation of these three houses reflects the cumulative means and interests of their owners. All were inhabited over many years, and by the late 500s had seen multiple changes and repairs. The lack of masonry benches or other permanent installations suggests that the use of most spaces varied considerably, perhaps among household members, with time of day and season, and over the years. Portable stone surfaces would have expanded the flexibility of these rooms by being stored elsewhere and brought when needed, to rest on movable supports.Footnote 24 The most elegant options included marble trapezophoroi and metal tripods, but simple wood struts could serve just as well. Little skill was needed to cobble together a plain but sturdy trestle, and two or three could safely support a substantial load (Fig. 11).Footnote 25

Fig. 11. Ad hoc installation of table from MMS/S Room D on three wood sawhorses. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

As for seating, masonry and wood benches were less suited to the curved perimeter of a circular or lunate table than simple chairs or folding stools, particularly when used in a confined area. Such basic forms of accommodation served many everyday needs and their use must have been widespread. Reclining at formal meals had traditionally been seen as an attribute of age, gender, or prominence, but written and pictorial sources suggest that by the later 3rd and 4th c. CE upright seating was becoming increasingly common.Footnote 26 Several houses at Sardis show how the practicality of upright seating could have encouraged aspiring homeowners to create compact yet attractive reception rooms to serve varied occasions while differentiating status in other ways.Footnote 27 Such expedience helped local traditions of convivial dining survive into the 5th and 6th c. CE.

Table arrangement

Marble trays and tabletops are only the best known of Late Roman dining surfaces, which were made in materials ranging from mundane to exotic.Footnote 28 The simple design and minimal decoration of most tables suited their large-scale production in limestones, fine regional marbles, colored breccias, and porphyries.Footnote 29 Flat, squarish slabs were sawn just thick enough to leave a low border around the central surface. Rectangular, circular, and lunate shapes were carved with edges of varied profile: usually a concave or simply molded band, occasionally a beaded or scalloped (polylobate) perimeter, rarely a border carved in low relief. Upper surfaces were smoothed and often polished, with the outer edge and reverse left semi-finished. Despite the superficial familiarity of marble trays and tables, today little is certain about their chronology, morphological development, distribution, use, lifespan, and cost.Footnote 30 Like other significant furnishings, a large, heavy tabletop represented a household's status and wealth. No doubt this would have been a significant investment for many families, but if carefully handled might be expected to last for generations.Footnote 31

The widespread occurrence of myriad fragments makes clear that marble trays and tables found many uses in Late Roman homes.Footnote 32 Trays were generally small, lightweight, and circular in shape, so as to be carried fully laden by a single servant. Larger trays with a raised rim could be balanced on a monopodium or tripod to serve as an occasional place to display prized objects or food. Heavy tables of circular and lunate form were less casually moved and required more substantial support. While some stationary tables may have served as altars in private chapels, their liturgical use in houses is hard to establish.Footnote 33 Decorative and funerary images of guests crowded around large tables illustrate their obvious role in banquets, although it is unclear where and how often this sort of meal took place. Table fragments regularly appear in houses that lack space or facilities for status dining, and in far greater numbers than such occasions would suggest. The mobility of tables among rooms of varied purpose underscores their more prosaic if unremarked roles in daily life: for playing games and working on crafts, preparing food and socializing children, and gathering household members for refreshment and conversation.Footnote 34

Despite their ubiquity in Late Antiquity, few complete examples of trays and tables have been found while excavating houses. The best-preserved specimens come from medieval reuse in cemeteries, churches, and other secondary contexts.Footnote 35 In domestic settings, tables usually appear as random fragments strewn through final levels of occupation.Footnote 36 More complete recovery depends on a room's unexpected destruction and abandonment, without significant scavenging before its controlled excavation. Such circumstances of preservation and recovery are not often met (see Table 1). Among the earliest reported examples is a nearly complete sigma table in red marble found amid the late 6th-c. CE destruction of a commercial or domestic area at Corinth.Footnote 37 Substantial parts of tables with scalloped borders have been found in destruction levels of a residential area at Ephesos, a house at Daphne-Harbie near Antioch, and Areopagos House C in Athens.Footnote 38 Two circular trays were found broken in place in the Emporio Fortress amid debris of the mid-600s CE.Footnote 39 A few such tables come with evidence of their likely architectural arrangement. Most of a sigma table was located near the apse of the Stobi “Casino,” which may once have enclosed a masonry bench.Footnote 40 Two nearly complete lunate surfaces were found in neighboring rooms of the House of the Stag at Apamea in Syria: one in a large rectangular space (A), the other in a smaller apsidal room (F). Signs of burning and lack of permanent support suggest that diners relied on portable seating and supporting structures of wood. The broken but near total recovery of both tables reflects the destruction and abandonment of the complex in the early 7th c. CE.Footnote 41

The three Sardis tables come from comparable scenes of residential wreckage and desertion (Figs. 12–14). The HoB and Field 55 tables were carved of lightly veined white marble and are of similar size, at slightly over 1 m on a side. Both have a plain band border with slightly rounded, tapering sides and are semi-finished underneath. A block-shaped monogram cut into the reverse of the Field 55 table asserts the claim of an apparent owner, perhaps Olympios, to his valued household possession; incised scoring of the upper surface attests hard use over a long life.Footnote 42 The larger MMS/S table was cut from different, strongly veined stone. It has a very thick central surface, parallel sides, and a band border in two steps, as well as distinctive quarry marks on the reverse. On all three examples, the lower border is interrupted by an axial wipe-away set between rounded ends. The recovery of nearly all pieces allows estimates of the original weights, which range from less than 40 kg at Field 55 and about 63 kg at HoB to 150 kg at MMS/S. Two or three servants or slaves would have had little trouble carrying the smaller tables between rooms; however, the considerable weight of the MMS/S table, together with the attendant stibadium, suggests that it was moved less often. Two more examples from Field 55 Room A can be added to this group: most of a delicate sigma table with molded border and beaded rim, and a complete circular tray or table with projecting edge. The thin central surface and expert finish of all three pieces can be distinguished from the larger, heavier tables seen at HoB and MMS/S, and they probably served in more elegant circumstances before ending up in Room A. The surplus furnishings nevertheless figured among the prized possessions of the occupants, who kept them, even when not needed, close at hand (see Appendix).

Fig. 12. S95.4:10295 from MMS/S Room D. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Fig. 13. S09.1:12349 from House of Bronzes Room 5/13. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Fig. 14. S15.34:14329 from Field 55 Room A. (© Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

These are only some of the most complete tables to have been found at Sardis, where the discovery of many more fragments makes clear their popularity in Late Antiquity and challenges in recording today.Footnote 43 Altogether, nearly 60 different examples can be distinguished among the larger pieces, with roughly a third belonging to circular trays or tables and the rest coming from rectangular or lunate surfaces. Parts of about 30 tables were recovered in the 1960s while excavating the Bath–Gymnasium, Byzantine Shops, and Synagogue. None of these are complete and only two are well represented: a sigma table with scalloped border, perhaps from the Synagogue Forecourt, and a circular tray or piatto with beaded rim found in a late room installed in a streetside portico.Footnote 44 The variety of non-joining fragments suggests that most tables were broken elsewhere and their pieces gathered by scavengers rummaging for material to reuse or reduce to lime. A likely goal would have been the large limekiln set up in the nearby Bath–Gymnasium and dated by pottery and coins to the mid-7th c. CE.Footnote 45

The high degree of fragmentation of marble tables may be obvious in the field, but in reports can be obscured by the typological tendency to see the part as the whole and to reconstruct for graphic or visual display what is quite incomplete.Footnote 46 Fine marble tables were particularly subject to repurposing as paving, revetment, or building material, as simple tools or working surfaces, or simply for crushing and burning. The thin recessed surface was vulnerable to cutting, dropping, or striking, and large pieces were easily reduced to tiny scraps. For these reasons, the presence of multiple unrelated fragments probably indicates purposeful but haphazard salvaging following abandonment, in Antiquity or more recent times.Footnote 47 The discovery of a substantially complete table reveals a different story: its breaking in a place where it was being used, and in a setting overlooked by later scavengers.

Things served

The recovery of other artifacts from these three houses reinforces the impression of domestic contexts that were unexpectedly closed and largely forgotten. If marble tables ranked high among a household's possessions while intact, their shattered pieces remained potentially useful for construction or making lime. Metal vessels and tools like those left at HoB and Field 55 continued in demand, if only as easily recycled scrap. The remains of glass, lamps, and pottery had less intrinsic worth, apart from reflecting the resources, tastes, and interests of former occupants – and much later, of archaeologists. The few recovered coins make clear that all three houses were affected by the same disruptive events that have been noted elsewhere at Sardis in the early 600s CE.

Excavation of the House of Bronzes in 1958–59 recovered a striking number of metal objects from floor level in Room 5/13 and nearby spaces. Furnishings of the large room included a copper-alloy discoid polykandelon, censer, and two lock plates, in addition to door fittings, a few tools, and the iron-frame campstool and sword from the alcove.Footnote 48 The celebrated copper-alloy vessels found in nearby spaces 1 and 7 include two cylindrical sheet-metal jugs, two authepsae, two more censers, a cauldron, and an ornate incense shovel.Footnote 49 Tablewares from floor level were scarce and only a few pieces of glass and pottery were saved, along with coins of Tiberius II (struck in 579 CE) and Maurice (587/8 CE).Footnote 50 More westerly parts of the house remained open, if not continuously inhabited, into the early 7th c. CE.

MMS/S Room D and Court E were explored in 1995, with work in neighboring rooms A and F continuing until 1998. Metal objects were limited to iron nails, fittings, and a single projectile point. Ceramics from floor level in Room D were sparse but included two incomplete African Red Slip dishes (forms 103, 105/6), a dish/bowl of LRC/Phocean Red Slip (form 10B/C), and a moldmade figural ampulla.Footnote 51 From a pit and bench in Cellar F came more African Red Slip, Asia Minor Light Colored, and local red-slipped wares, together with fusiform unguentaria, storage jars, and cooking pots.Footnote 52 A dozen coins from this group of rooms date to the reigns of Justin II (565–75 CE), Tiberius II (578–82 CE), and Phocas (602–10 CE).Footnote 53

The 2015 campaign at Field 55 focused on Room A's latest occupation before the collapse of the upper level and surrounding walls. The disposition of artifacts implies that occupants fled suddenly and left behind many domestic goods – and perhaps a member of their household, whose remains were partially reclaimed later. Metal furnishings were abundant and included a copper-alloy polykandelon, an iron lampstand, and two lock plates with keys. Two small copper-alloy buckles of lyriform shape show close contact with civil and military authorities. Copper-alloy vessels included a pair of cylindrical jugs, a ewer, a situla with swing handle, and two shallow pans, one from a balance set.Footnote 54 Evidence for light agricultural work appears in an iron socketed hoe, a billhook or sickle, and a scythe or spokeshave, with small tools, chains, handles, binding straps, fittings, and a large ceramic tub expanding the picture of domestic crafts. Serviceable table pottery was limited to a dish with plain rounded rim, two smaller vessels resembling LRC/Phocean Red Slip form 3, and a pair of cylindrical jugs, all in local red-slipped wares.Footnote 55 Traces of red pigment survived in one of the jugs and a conical ceramic crucible.Footnote 56 Four glass stemmed goblets and a tall-necked bottle may also have been set on the table. The latest coin from this level was a follis of Heraclius minted in 611/12 CE.

In addition to marble tabletops, these three assemblages share several noteworthy features: a copper-alloy polykandelon, cylindrical jugs, and assorted vessels at the House of Bronzes and Field 55; iron tools and agricultural implements at HoB and Field 55; and a few red-slipped table dishes at MMS/S and Field 55. The scarcity of pottery on floors may be disappointing from an archaeological standpoint but is characteristic of high-visibility spaces that were being managed for activity rather than storage. At HoB and MMS/S this suggests the regular cleaning of rooms where formal dining took place intermittently, if not at the moment of their destruction. The larger collection of metal, ceramic, and glass vessels at Field 55 more readily meets expectations of a space where meals were being shared but not necessarily prepared. Coins were scarce in all three contexts, yet each had one or more small-denomination issues with the latest struck within a 25-year span, between 587/8 and 611/12 CE. A similar range of artifacts has been found elsewhere at the HoB, MMS, and Field 55 sectors, and in particularly large numbers in the Byzantine Shops. Excavation between 1959 and 1970 found that this long row of streetside rooms perished in an extensive fire, which left commercial and domestic contents buried under a thick layer of debris. While some of the 30-odd units may already have stood empty and others saw limited salvaging, the latest occupation of most shops can be dated by coins of Heraclius issued between 610 and 615/16 CE. The largely undisturbed contents document a broad horizon of activity around the turn of the 7th c. CE.Footnote 57

Common and divergent aspects of these three domestic contexts touch directly on questions of contemporaneity and cause. It is tempting to ascribe all this damage to a single cataclysm that struck Sardis about 615 CE, such as an unattested Persian raid blamed by early reports for the destruction of the House of Bronzes, Byzantine Shops, and Synagogue.Footnote 58 Recent mapping of widespread structural damage and landform alteration around this time has shifted attention to natural phenomena such as earthquakes, which seem to have presented challenges to urban infrastructure that began earlier and continued over several years.Footnote 59 The few coins found in these three houses give only a general terminus post quem for the destruction of each space: 587/8 CE at HoB Room 5/13, 603–10 CE at MMS/S Room D, and 611/12 CE at Field 55 Room A. The strongest numismatic evidence comes from MMS/S, where six issues of Phocas conclude no later than 610 but perhaps as early as 606/7 CE. The impression that this suite of rooms was closed by ca. 610 CE is reinforced by signs of widespread scavenging and continued occupation in the eastern part of the domus, which remained open after 615/16 CE.Footnote 60 The western and southern parts of the House of Bronzes, which stood only 100 m away, also show signs of reduced activity continuing into the early 610s CE.Footnote 61 A similar sequence of damage, salvage, dumping, and limited reoccupation can be traced at sectors MMS, Field 55, and elsewhere into at least the second quarter of the century.Footnote 62 In each case, isolated clusters of well-appointed domestic spaces were abruptly stricken and left unrepaired by their inhabitants, who retreated to other parts of their houses for a few years before abandoning them altogether. The steady accumulation of evidence suggests that several parts of Sardis experienced significant seismic damage around 610 CE, and this hindered the ability of residents to respond to an even larger event in the years following 615 CE.Footnote 63

Leftovers

The traditions of Classical dining have left a lasting impression on the historical imagination, which has selectively drawn on texts and monuments to shape a composite view of elite social interaction in Roman times. Archaeology's contribution to this normative account has been largely illustrative, informed by aspects of material culture that are usually taken in typological isolation. Recent excavations at Sardis offer an alternative, integrative view of the architectural setting, material furnishings, and domestic artifacts of three fortuitously preserved dining spaces of the Late Empire. In each case, the decisive presence of a nearly complete marble sigma table establishes both the intentional use of a room for serving meals and the lack of significant salvaging after its destruction. Considered together, these exceptional contexts reveal unsuspected complexity and nuance in the experience of everyday life around the turn of the 7th c. CE.

The swift destruction of the three Sardis houses preserved different approaches to meal sharing among families of varied means and standing. The ancient custom of stibadium dining in a dedicated triclinium can still be seen at MMS/S Room D, a luxuriant space that conserved the trappings of an affluent house of the 4th c. CE. The slightly later renovation of HoB Room 5/13 reflects the growing vogue for apsidal rooms among aspirant urban homeowners, who introduced a stage-like alcove where visitors could be received and where guests could be entertained at dinner while seated on folding stools. Both of these rooms were distinguished by their large size, central location, and costly aspect, and with generous area set aside for attendants, entertainers, and hangers-on. This emphasis on public display and controlled interaction contrasts with Field 55 Room A, a spare, taberna-like space in which occupants gathered with less formality around a central table for meals, handicrafts, and other household activities. The limited quantity of domestic debris in these rooms suggests that all were being used and cleaned on a regular basis. In each case, various ceramic, glass, and metal vessels were drawn from the same sources, primarily local and betraying little sense of relative cost or social status. Destruction and abandonment of all three rooms over a few years throw into high relief the selective scavenging and short-lived reoccupation of other spaces, here and across the site.

The fate of the Classical city remains a defining question for the history of Late Antiquity. Early excavators at Sardis saw a thriving provincial capital whose prosperity was cut short by military crisis. A half century later, this narrative can be expanded beyond public buildings to include lives at home, as local residents were progressively overwhelmed by natural disasters and their wider consequences. The final meals celebrated in the House of Bronzes and MMS/S domus mark the eclipse of Classical dining traditions and the complex urban society they defined. The letting go of these imposing spaces in favor of simpler forms of reclaimed shelter, at Field 55 and elsewhere, was among the adaptive compromises with which residents faced the challenge of their times.

Acknowledgments

The Archaeological Exploration of Sardis was begun by George M. A. Hanfmann in 1958 and has continued under the direction of Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr. (1976–2007) and Nicholas D. Cahill (since 2008), each of whom contributed one of the tables discussed here. My thanks to them for years of expedition leadership, to Teoman Yalçınkaya for his assistance in the field (Fig. 11), and to Catherine Swift Alexander (Fig. 7), Brianna Bricker (Figs. 1, 2, 4, 6, 8), Jivan Güner (Figs. 12–14), and Sheng Zhao (Figs. 9, 10) for their interest and visual support.

Appendix: Five marble tables at Sardis

S95.4:10295 (Fig. 12). Lunate sigma table from MMS/S Room D.

Completely reassembled from ten joining fragments and many small chips. W. 1.28 m, l. 1.345 m, border w. 0.075–0.077 m, border h. 0.055 m, surface d. 0.025–0.035 m. Medium-grained light grayish marble with pronounced swirling dark gray veins and visible flaws. Flat surface enclosed by two-stepped band border, interrupted by narrow (0.08–0.12 m) wipe-away at center of straight side; outer wall squared with unevenly finished vertical face, summarily smoothed along straight side. Central surface and top of border polished; bottom and outer edge roughly dressed with point and claw chisels. Downward-facing surfaces encrusted. Total weight 150.1 kg.

S09.1:12349 (Fig. 13). Lunate sigma table from HoB Room 5/13.

Substantially reassembled from many joining fragments. W. 1.115 m, l. 1.065 m, border w. 0.012 m, border h. 0.025–0.035 m, surface d. 0.014–0.022 m. Medium fine-grained white marble with light gray veins. Flat surface enclosed by wide band border, interrupted by narrow (0.08–0.11 m) wipe-away at center of straight side; outer wall slightly rounded. Central surface polished but encrusted; bottom semi-finished with traces of fine chisel marks. Discolored by fire, especially on back, and stained by patches of iron oxide. Total weight 60.5 kg, plus 3–5% lost = approx. 63 kg.

S15.34:14329 (Fig. 14). Lunate sigma table from Field 55 Room A.

Substantially reassembled from many joining fragments. W. 1.005–1.025 m, l. 1.015 m, border w. 0.115–0.120 m, border h. 0.025 m, surface d. 0.006–0.008 m, narrowing appreciably toward left side. Medium fine-grained white marble with very light gray veins. Very thin, flat surface enclosed by raised border with projecting wide horizontal rim with vertical face, interrupted by narrow (0.08–0.11 m) wipe-away at center of straight side; outer wall rounded, smoothed, offset at base. Central surface polished but scored by many irregular incised lines, preserving someone's ill-advised cutting directly on the surface; reverse semi-finished, with wipe-away repeated under rim and box-shaped monogram (Olympiou?) near apex of curved edge. Total weight 37.1 kg + 3–5% lost = approx. 39 kg.

S14.20:14025. Lunate sigma table with beaded rim, from Field 55 Room A.

Two large, non-joining sections of rim, parts of central surface in many fragments. Est. w. 0.89–0.90 m, est. l. 0.94 m, border w. 0.059 m, border h. 0.03 m, surface d. 0.012–0.017 m. Medium fine-grained white marble. Flat surface enclosed by rounded border with beading along outer edge; underside hollowed with squared, vertical face. Central surface smoothed; reverse semi-finished, with distinct chisel marks (claw on bottom, bullnose under border). Edge of long diagonal break very worn, suggesting vertical deposition and exposure to erosion. Partly encrusted and stained by iron oxide. Total weight 16.8 kg + 60% lost = approx. 42 kg.

S15.42:14372. Circular tray or table (piatto) from Field 55 Room A.

Completely reassembled from four joining fragments. Diam. 0.69 m, border w. 0.045 m, border h. 0.055 m, surface d. 0.025–0.030 m. Medium-grained white marble with distinct gray veins. Flat surface enclosed by raised projecting border narrowing to slightly rounded face; outer wall rounded; entire tray rests on a low, narrow foot. Central surface smoothed; bottom slightly hollowed, semi-finished with broad sweeps of claw chisel marks. Total weight 24.1 kg.