Introduction

According to the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, mothers who experience stress during pregnancy, including socioeconomic (SES) risk and intimate partner violence (IPV), have children who are at increased risk for socioemotional and behavioral difficulties, such as internalizing and externalizing problems. Reference Glover1–Reference Monk, Lugo-Candelas and Trumpff5 Following bioecological models of health and development, Reference Bronfenbrenner and Morris6 such experiences of stress and trauma occur across contexts, ranging from more proximal (e.g., an individual’s direct experience of stress, such as trauma or IPV) to more intermediate stressors (e.g., the effects of SES as a stressor on the family as a whole) to more distal (e.g., living in a high crime neighborhood), yet these multiple contexts are often not examined simultaneously. Experiences across these multiple levels of influence have the potential to impact not only the pregnant mother’s wellbeing but may also have intergenerational effects for their offspring. Reference Messer, Kaufman, Dole, Savitz and Laraia7 Even beyond her experiences during pregnancy, a growing body of research also highlights intergenerational effects of mothers’ histories of experiencing trauma (e.g., physical or sexual abuse), during their own childhoods, on their offspring decades later. Reference Bale, Baram and Brown4,Reference Pluess and Belsky8,Reference Barrero-Castillero, Morton, Nelson and Smith9

A range of maternal stressors and risk factors, occurring across levels of influence, have been implicated in children’s socioemotional and behavioral development, but are often studied in isolation or as part of a more global, cumulative risk score that ignores the independent contribution of different types of stress exposures. Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan10,Reference Evans, Li and Whipple11 In one exception, a recent study examined how multiple maternal stressors, including self-reports of prenatal psychosocial risk (e.g., pregnancy stress, mental health), maternal childhood adversity, and health risk (e.g., pregnancy complications), were associated with poorer infant development at age one. Reference Racine, Plamondon, Madigan, McDonald and Tough12 Despite the advances and novel contributions of recent research, the large majority of these studies still ignore the broader neighborhood context. A growing body of epidemiological and health research indicates that broader neighborhood factors – such as objective measures of poverty or residential stability – are associated with physical and mental health problems. Reference Momplaisir, Nassau and Moore13–Reference Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn15 Fewer studies have looked at the associations between stress related to neighborhood crime – such as violent crime rates as reported by law enforcement agencies – and increased health problems, however growing research suggests a positive association between living in neighborhoods with higher crime and experiencing more mental health problems, including stress, anxiety, and depression. Reference Curry, Latkin and Davey-Rothwell16–Reference Baranyi, Di Marco, Russ, Dibben and Pearce19 Fewer still have examined this association intergenerationally to assess whether these risks are transmitted to offspring in a manner that impacts their wellbeing, Reference Messer, Kaufman, Dole, Savitz and Laraia7 and to our knowledge none have looked beyond birth outcomes. In addition, prior examinations of maternal stressors are limited by their use of predominantly White, middle class samples that might not generalize to more diverse, low-income individuals who often experience greater frequency and elevated severity of community stressors. There is a need, therefore, to simultaneously examine multiple dimensions of maternal stressors – capturing experiences from childhood (e.g., trauma) and pregnancy, and incorporating stressors from multiple contexts (e.g., socioeconomic, interpersonal, neighborhood) – in order to determine the degree to which these stressors have general or specific associations with offspring socioemotional and behavioral difficulties. A number of studies also have found that prenatal programming effects of maternal stress on offspring behavior may differ by sex, however these findings have been mixed and require additional study. Reference Glover and Hill20,Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel and Lahti21

Within the burgeoning prenatal programming research, examination of potentially malleable moderators of the association between maternal prenatal stress and child behavioral health has been limited, Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel and Lahti21–Reference Doyle and Cicchetti23 although extant research is promising. Reference Bergman, Sarkar, Glover and O’Connor24–Reference Lee, Halpern, Hertz-Picciotto, Martin and Suchindran27 More specifically, identifying modifiable environmental protective factors, such as parenting knowledge and social support, that could buffer child health from the risks associated with prenatal stress may inform the development of pediatric screening and intervention efforts designed to protect against the deleterious effects of maternal stress exposures on child health. Reference Treat, Sheffield-Morris, Williamson and Hays-Grudo28,Reference Racine, Madigan, Plamondon, Hetherington, McDonald and Tough29 Parents with more social support (e.g., receiving additional help in the home, being emotionally supported) or greater knowledge of child development may have advantages in managing the struggles of parenting very young children Reference Hess, Teti and Hussey-Gardner30 and be better able to support children’s socioemotional and behavioral development. For example, some studies have found that knowledge of child development was positively associated with parental confidence and responsiveness to offspring. Reference Hess, Teti and Hussey-Gardner30,Reference Ruchala and James31 These may be especially salient protective factors within families experiencing high levels of stressors. However, the few existing intergenerational studies that have explored the protective effects of such factors largely utilize single stressors, limiting understanding of the value of these potential buffers across multiple forms of stress. Further, to our knowledge, none have explored the potential moderating effects of parental knowledge of child development on the association between maternal prenatal stress and child behavioral health.

In a large, diverse pregnancy cohort of mother–child dyads, we examined exposures of maternal trauma during childhood, as well as SES risk, IPV, and neighborhood violent crime during pregnancy in relation to offspring socioemotional and behavioral difficulties at age one. Consistent with the DOHaD framework, it is valuable to elucidate intergenerational effects of maternal stress on offspring development and behavior in infancy and very early childhood, prior to the substantial impact of postnatal environmental factors. Reference Monk, Lugo-Candelas and Trumpff5,Reference Hartman and Belsky32 Based on prior research, Reference Doyle and Cicchetti23,Reference Hess, Teti and Hussey-Gardner30 we also tested whether parental knowledge of child development and perceptions of social support buffered children from these risks. We hypothesized that each type of maternal stressor would be independently associated with higher levels of child socioemotional-behavioral problems. We further hypothesized that prenatal social support and knowledge of child development would moderate these associations, such that greater support and knowledge would buffer against the negative effects of multiple maternal stressors on child functioning. Finally, given the mixed findings from previous studies, we tested whether child sex would moderate the relation between each maternal stressor and child socioemotional-behavioral problems.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The present study utilized data from the Conditions Affecting Neurocognitive Development and Learning in Early Childhood (CANDLE) study, a prospective pregnancy cohort that is part of the ECHO PATHWAYS consortium. Reference Sontag-Padilla, Burns and Shih33–Reference Slopen, Roberts and LeWinn35 Between 2006 and 2011, 1503 women from Shelby county, Tennessee, were enrolled in the study. Inclusion criteria included women between 16–40 years old, 16–27 weeks gestation, low-risk pregnancies, and no preexisting conditions that required medication. Details on study enrollment are available elsewhere. Reference Sontag-Padilla, Burns and Shih33

Data were collected during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, at a home-visit 4 weeks post-birth, and at a clinic visit 1-year post-birth. Of the original 1503 women recruited during pregnancy, 1127 provided child outcome data for the present study at the 1-year clinic visit, which make up the total sample in current analyses. For the retained sample, mothers tended to be older, have higher annual household income, and lived in neighborhoods with lower violent crime rates. The study was conducted at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and approved by its Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent for themselves and their children.

Exposure variables

Maternal childhood traumatic events

Maternal report of childhood traumatic events (CTE) was obtained during pregnancy via the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire, Reference Kubany, Haynes and Leisen36 which assesses whether they experienced any of the following three types of traumatic events before the age of 13: a) physical abuse, b) sexual abuse, or c) witnessed family violence. Each item was answered yes/no, resulting in a summed count ranging from 0–3. Reference Slopen, Roberts and LeWinn35,Reference Adgent, Elsayed-Ali and Gebretsadik37

Socioeconomic risk

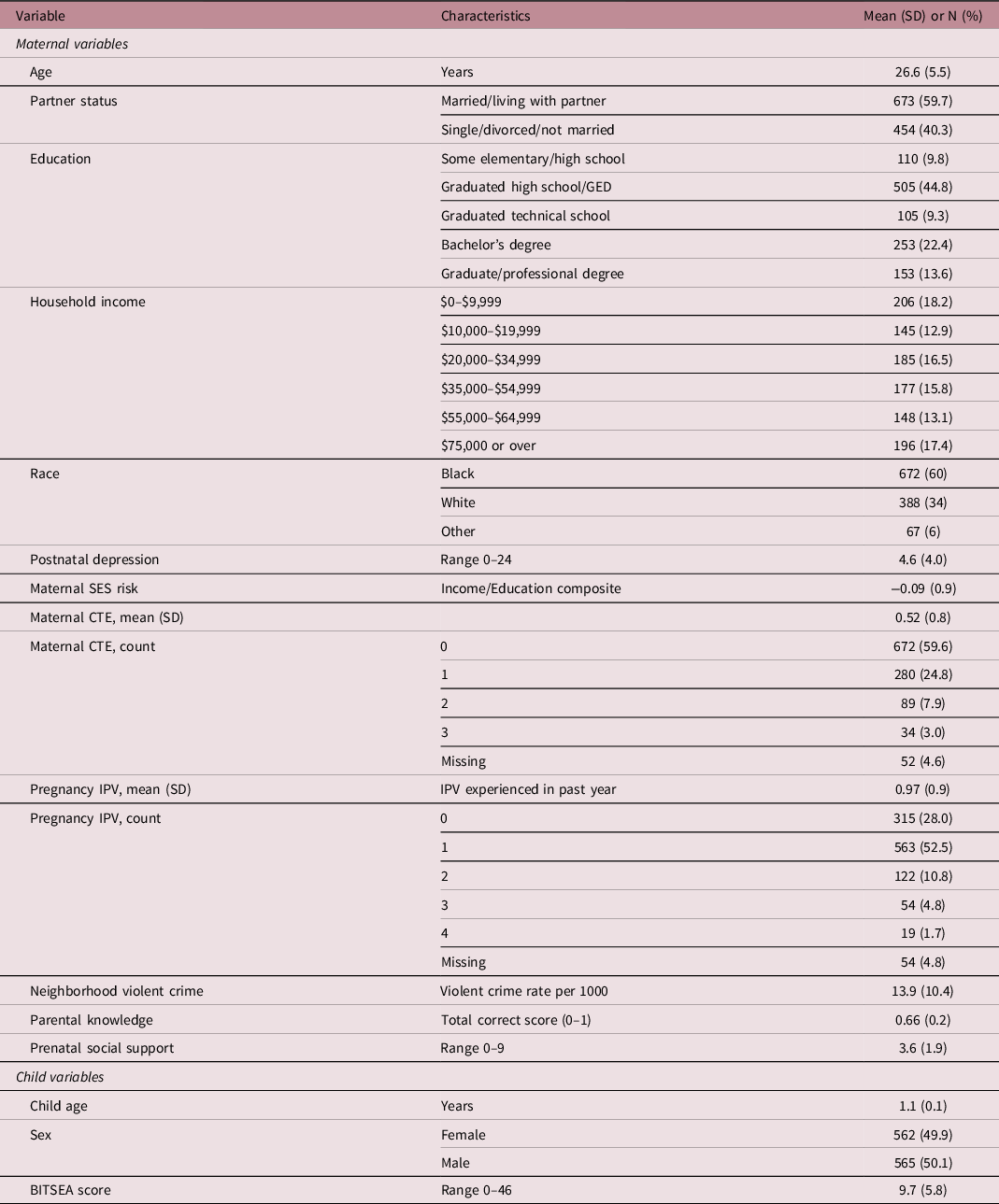

Socioeconomic (SES) risk during pregnancy comprised a composite of education (5-point scale ranging from less than high school to graduate school/professional degree) and yearly income adjusted for household size (11-point scale ranging from <$5,000 to >$75,000; Table 1). Both variables were standardized, then averaged to create an SES composite, which was reverse-scored so that higher values indicated increased risk.

Table 1. Demographic information and model variables (N = 1127)

CTE: childhood traumatic event types; IPV: intimate partner violence; SES: socioeconomic status.

Intimate partner violence

Women reported on their experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) at their third trimester pregnancy visit via the short-form version of the revised Conflict Tactics Scale. Reference Straus and Douglas38 For this study, participants’ indications (yes/no) of whether they had experienced any of four forms of aggression (physical, sexual, psychological, and injury) perpetrated by their partner in the past year Reference Straus and Douglas38 were summed to create a total count ranging from 0–4 (Table 1).

Neighborhood violent crime

To assess a neighborhood-level measure of stress exposure, we used an objective, geospatial index of neighborhood violent crime that was derived from a national register of crime data obtained from Neighborhood Scout. 39–Reference Suplee, Bloch, Hillier and Herbert41 This national database of geocode-linked crime statistics is based on Uniform Crime Reports provided annually to the FBI by a broad range of local law enforcement agencies and includes all known violent crime incidents that occurred within each agency’s jurisdiction. Reference Goldman-Mellor, Margerison-Zilko, Allen and Cerda40,Reference Gove, Hughes and Geerken42 Participant address information was collected during enrollment and subsequently at each study visit (including second trimester, third trimester, 1 month postpartum, and at the 1-year clinic visit). These addresses were then geospatially linked to Neighborhood Scout crime statistics at the census block group level, where incidents of violent crime were partitioned and reported per 1000 residents (range 0.1–50.5). Given the study enrollment period spanned 5 years, and given that births spanned from 2007 to 2012, crime rate statistics were obtained for two different years – 2009 and 2012. For each participant, statistics for the year closest to their child’s birth were utilized. Of note, the crime statistics were quite stable between 2009 and 2012 (Pearson correlation was 0.93). For participants who moved during the study period (about 25% of the sample), a residence-weighted average crime rate was used across all reported residences to most accurately assess the average violent crime rate exposure per participant during the perinatal period.

Moderator variables

Knowledge of child development

The Knowledge of Infant Development Inventory (KIDI) Reference MacPhee43 was administered during pregnancy to assess familiarity with a range of typical developmental norms and milestones. It includes 58 items probing knowledge of physical, cognitive, linguistic, social, and perceptual development from birth to 24 months, such as “babies cannot see or hear at birth” and “one-year-olds know right from wrong.” Women indicated whether they “agree”, “disagree”, or are “unsure.” A total correct score was created (range 0–1), representing the percentage of total correct answers out of 58. Reference MacPhee43 The KIDI has previously shown good internal consistency/reliability and validity. Reference Hess, Teti and Hussey-Gardner30,Reference Macphee44

Maternal social support

Women reported on their social support during pregnancy via the short-form version of the widely used Social Support Questionnaire. Reference Sarason, Sarason, Shearin and Pierce45 Participants indicated the number of people (up to nine allowed) that they could rely on in six different situations during which they might need social support. Counts for these six items were then averaged to create a composite score ranging from 0–9. Reference Sontag-Padilla, Burns and Shih33

Outcome variable

Socioemotional and behavioral health assessment

Child socioemotional and behavioral problems were assessed via the Brief Infant Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) at the age-one clinic visit. The BITSEA is a 42-item parent report screening tool for infants and toddlers. We utilized the Total Problems scale, which combines internalizing, externalizing, and dysregulation problems. This measure has been validated with sociodemographically diverse samples, Reference Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel and Cicchetti46,Reference Briggs-Gowan and Carter47 has demonstrated good internal consistency, and concurrent and predictive validity with measures of functioning later in childhood. Reference Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel and Cicchetti46–Reference Karabekiroglu, Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Rodopman-Arman and Akbas48

Covariates

Several sociodemographic variables were obtained from participants and used as covariates, as they have been shown to be associated with child behavioral health problems and have been commonly used in prior prenatal programming research. Reference Letourneau, Dewey and Kaplan49–Reference MacKinnon, Kingsbury, Mahedy, Evans and Colman53 These included maternal age (years) at study recruitment, marital/partnered status, and race, as well as child sex and age at the outcome (year-one) visit. In addition, we included maternal report of depression symptoms, measured at 4-week post-birth, using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky54 in order to account for the potential influence of postpartum depression on young child behavioral problems, given that postpartum depression can affect as many as one in six mothers. Reference Bauman55,Reference O’Hara and McCabe56

Statistical analysis

We performed three multiple linear regressions with listwise deletion using SPSS version 26 57 to assess the independent association of each exposure variable (CTE, SES risk, IPV, neighborhood violent crime) with child socioemotional-behavioral problems. Results are presented in six models. Overall, missing data ranged from none (mainly demographic information) to 7.9% for one of our covariates (postnatal depression), with most variables having less than 5% data missing. Given the limited amount of missing data, we chose to utilize a complete case analysis approach. Reference Graham58 Model 1 examined the association between all four exposures and child problems. Given the strong correlation between race and other study variables (Table 2), Model 2 added all covariates except for race. Model 3 built on Model 2 by including race. To test moderation, we utilized the SPSS PROCESS macro Reference Hayes59 to multiply each stress exposure by each moderator variable (all variables were standardized prior to interacting), resulting in four interaction terms for both parental knowledge and social support. We then examined the conditional effect of each exposure at varying levels of the moderator. For the tests of moderation, both moderator variables were modeled continuously, with illustrative probing of simple slopes conducted at ±1 SD, per standard practice. Reference Aiken and West60 Model 4 examined parental knowledge by adding the KIDI variable and its four interaction terms to Model 3. Model 5 replicated the Model 4 procedure, but instead examined maternal social support as a moderator. Finally, in Model 6, we tested for potential sex-specific effects of each exposure variable on child socioemotional-behavioral problems by adding four sex-by-exposure interaction terms (one for each exposure) to the fully adjusted model (Model 3).

Table 2. Bivariate correlations between study variables

CTE: childhood traumatic event types; IPV: intimate partner violence; SES: socioeconomic status.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

a Analytic dataset N = 1127.

Results

Sample characteristics

Demographic information of the analytic sample is presented in Table 1. At recruitment, women’s average age was 26.6 years, the median education completed was high school, and approximately 60% of participants were married or living with their partners. Median family income was between $25k–$35k. The analytic sample was 60% Black, 34% White, and 6% other/mixed race. Approximately 36% of women reported experiencing at least one type of childhood trauma (11% experienced two types; 3% experienced three types). Twenty eight percent of participants reported experiencing no form of IPV during pregnancy, 67.2% reported experiencing at least one form, and 17.3% reported experiencing two or more forms. The mean neighborhood violent crime rate in this sample was 13.9 per 1000 residents, which was significantly higher than the 2011 national average of 3.9 per 1000 residents, but consistent with regional rates. On average, the percentage of total correct answers on the KIDI was 66%, which is similar to previous studies with representative samples. KIDI scores were well distributed, with roughly 150 participants (13%) scoring below one standard deviation of the mean, and roughly 200 participants (18%) scoring above one standard deviation of the mean. The mean score on the BITSEA was 9.7; 25% of the sample fell in the child behavior problem range, which is consistent with previous normative samples. Correlations are presented in Table 2. Of note, maternal SES risk was significantly correlated with neighborhood violent crime (r = −0.56, p < 0.001).

Maternal stress exposures and child socioemotional-behavioral problems

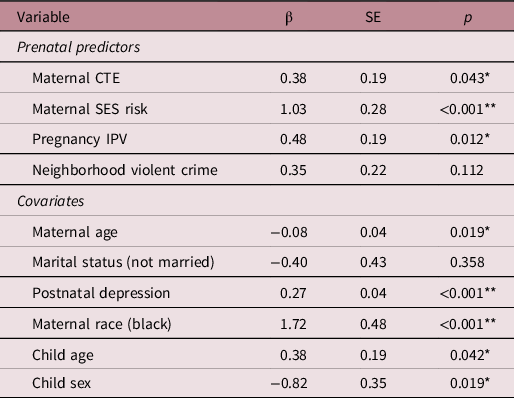

Multiple linear regression models are summarized in Table 3. In the predictor-only model (Model 1), all four maternal stress exposures (CTE, SES risk, IPV, neighborhood violent crime) were significantly associated with child socioemotional-behavioral problems at age one. In Model 2, all four exposures remained significant after including all covariates except maternal race. In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), which included race, maternal CTE (β = 0.38, p = 0.043, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.74), SES risk (β = −1.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI: −1.58, −0.48), and IPV (β = 0.48, p = 0.012, 95% CI: 0.11, 0.86) remained significantly associated with childhood problems (Table 4); however, neighborhood violent crime did not (β = 0.35, p = 0.11, 95% CI: −0.08, 0.79). Collectively, the four prenatal stress exposures accounted for approximately 15% of the variance in child problems (Model 1; see Table 3); the fully adjusted model (Model 3) accounted for approximately 22% of variance.

Table 3. Standardized regression models of maternal multidomain stress exposure associations with child socioemotional-behavioral health problems and tests of moderators

CI: confidence interval; CTE: childhood traumatic events; IPV: intimate partner violence; SES: socioeconomic status.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

a Predictor-only model.

b Partially adjusted model including the following covariates: maternal age, marital status, postnatal depression, child age, child sex.

c Fully adjusted model: Includes Model 2 covariates as well as maternal race.

d Model 4 includes all covariates and the four interaction terms between each stress variable and knowledge of infant development.

e Model 5 includes all covariates and the four interaction terms between each stress variable and prenatal social support.

Table 4. Standardized regression model with full covariates (Model 3) predicting child socioemotional-behavioral health problems

Notes: All variables were standardized in the model. Overall R2 = 0.22; CTE: childhood traumatic events; IPV: intimate partner violence; SES: socioeconomic status.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.001.

Tests of moderation

Moderation tests for parental knowledge (Model 4) revealed that the KIDI significantly moderated the association between both a) maternal SES risk (β interaction = 0.60, p = 0.020, 95% CI: 0.09–1.10) and b) maternal CTE (β interaction = 0.43, p = 0.042, 95% CI: 0.02–0.85) on child socioemotional-behavioral problems. For illustration, Figure 1 shows the interaction with SES risk, with tests of the simple slopes, plotted at 3 levels of the continuous KIDI measure. Reference Hayes59,Reference Aiken and West60 For participants with KIDI scores in the “average” (i.e., mean levels) or “low” range (i.e., −1 SD), maternal SES risk was significantly positively associated with child problems. For participants with KIDI scores in the “high” range (i.e., +1 SD), however, SES risk effects were buffered such that there was no significant association with child problems. Regarding maternal CTE (Fig 2), for participants scoring lower on the KIDI (i.e., −1 SD), children exhibited greater socioemotional-behavioral problems regardless of mother’s history of CTE. In contrast, for participants with KIDI scores closer to or above the mean (i.e., +1 SD), CTE was positively associated with child problems, such that greater knowledge was associated with fewer child problems, and this difference was strongest at lower levels of maternal CTE.

Fig. 1. Maternal knowledge of infant development moderates the association between maternal SES risk and child socioemotional-behavioral problems. Maternal SES risk wassignificantly associated with child problems for mothers with “average” or “low” levels of knowledge, but not for mothers with “high” levels of knowledge.

***p = .001.

Fig. 2. Maternal knowledge of infant development moderates the association between maternal CTE and offspring socioemotional-behavioral problems. Maternal CTE was significantly associated with offspring problems for mothers with “average” and “high” levels ofknowledge, but not for mothers with “low” levels of knowledge.

*p = .05; **p = .01.

Tests of moderation by prenatal social support (Model 5) were not supported (all four interaction terms were not significant). However, the social support-by-pregnancy IPV interaction term and social support-by-SES risk interaction term both demonstrated trend-level patterns (β interaction = −0.35, p = 0.07, 95% CI: −0.73, 0.03; β interaction = 0.38, p = 0.09, 95% CI: −0.06, 0.83, respectively), with simple slopes reflecting a potential buffering effect of social support. Finally, tests of moderation by child sex (Model 6) were also not supported: all four interaction terms were not significant (results not shown).

Post hoc sensitivity analysis

Although we sought to isolate prenatal stress effects by adjusting for postnatal depression, given the possibility that maternal psychopathology might be “on the pathway” from maternal stress to child psychopathology, we performed a sensitivity analysis on our full model (Model 3) by re-running the model without postnatal depression. The three exposures that were previously significantly associated with child problems remained significant: SES risk (β = 1.11, p < 0.001), maternal CTE (β = 0.45, p = 0.017), and IPV (β = 0.72, p < 0.001). Similarly, neighborhood violent crime remained not significant (β = 0.32, p = 0.148). We note that in the present study, maternal postnatal depression was only weakly correlated with maternal CTE, pregnancy IPV, and child socioemotional-behavioral problems (r’s ranging from 0.11 to 0.22; see Table 2). Removing postnatal depression did significantly reduce the overall model R2 from 0.22 to 0.19.

Discussion

Utilizing a large, diverse pregnancy cohort, we examined associations between maternal childhood trauma, multi-level stress exposures during pregnancy, and offspring socioemotional-behavioral problems at age 1 year. We found that maternal childhood trauma exposure, prenatal SES risk, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy were all uniquely associated with young children’s socioemotional-behavioral problems, after covariate adjustment, within a diverse urban southern sample – advancing evidence from extant prenatal programming research. Reference Glover1,Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel and Lahti21 To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to include community-level stressors (neighborhood violent crime) when assessing the intergenerational association of maternal stress and adversity on child development. When directly comparing the four predictors in our full model, maternal SES risk had the strongest association with child problems, followed by pregnancy IPV and maternal CTE. This is consistent with prior findings that highlight the critical importance of income and education (both measures of longer-standing, potentially chronic risk) as strong social determinants of health, Reference Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen61–Reference Braveman, Egerter and Williams64 with the ability to impact the wellbeing of multiple generations. Regarding maternal experiences of IPV during pregnancy vs. her experiences of trauma during childhood, it is possible that the more proximal nature of the former measure of stress (i.e., during pregnancy) – compared to the more distal nature of the latter (i.e., during the mother’s childhood) – could explain the differences in the strengths of these associations, although additional research is necessary. Reference Glover, O’Connor and O’Donnell65,Reference Letourneau, Dewey and Kaplan66 Regarding covariates, maternal postnatal depression had one of the strongest associations with child problems. This is also consistent with a large body of literature highlighting the impact of maternal psychopathology on child development and psychopathology. Reference Monk, Lugo-Candelas and Trumpff5,Reference Madigan, Oatley and Racine67,Reference Glover, O’Donnell, O’Connor and Fisher68

Another novel finding was that maternal knowledge of child development moderated associations between both family SES risk and maternal CTE on offspring socioemotional-behavioral problems. First, greater parental knowledge mitigated the adverse association between SES risk and offspring socioemotional-behavioral problems. Second, more knowledge also buffered the effects of maternal CTE against risk for offspring problems, with this difference being strongest at lower levels of maternal CTE. Third, while two interaction coefficients of social support approached significance, social support did not significantly moderate associations between maternal stressors and child functioning. This might be due to how social support was measured. Previous research suggests that specific domains of support, such as tangible versus informational support, may be more salient for protecting against the deleterious effects of prenatal stress, rather than the broadly defined support measure used in this sample. Reference Appleton, Kiley, Holdsworth and Schell69 Additionally, maternal social support may also be more protective for maternal wellbeing, while factors more closely related to parenting young children may be more buffering for children. In our final test of moderation, we did not find any sex-specific effects of maternal stressors on child socioemotional-behavioral problems for any of the four prenatal stress exposures. As extant findings have been quite mixed with regard to how maternal prenatal stress might differentially impact boys and girls, this is not necessarily surprising. Reference Glover and Hill20,Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel and Lahti21 Given that our large sample size provided adequate power, the lack of sex-specific associations suggest the patterns found in this study at age one are consistent for pregnancies carrying boys and girls.

Another novel finding was the relations observed between objectively measured, geospatially linked neighborhood violent crime, race, and child socioemotional and behavioral problems. Although exposure to neighborhood violent crime during pregnancy was significantly associated with child problems in partially adjusted models, it was attenuated after including race – highlighting the complex, potentially confounding nature of using race as a covariate. Reference Buchanan, Perez, Prinstein and Thurston70 Notably, the average crime rate in Shelby County was significantly higher than the national average. The association between crime rates, SES, and race are consistent with long-standing social inequities, including residential segregation, redlining, and discriminatory policing practices. Reference Zenou and Boccard71–Reference Squires73 Indeed, on average, Black mothers in this sample lived in neighborhoods with violent crime rates nearly three times that of White mothers. The considerable correlation between race and violent crime likely accounts for the loss of predictive value of crime when adding race to the model. We therefore interpret these findings to indicate that broader, community-level factors do indeed pose an increased intergenerational risk to offspring socioemotional and behavioral problems and provide an opportunity for additional programs and intervention efforts. The negative impacts of neighborhood disadvantage, more broadly characterized, on health are well documented. Reference Seeman, Epel, Gruenewald, Karlamangla and Mcewen74–Reference Kohen, Leventhal, Dahinten and McIntosh77 Differential associations between maternal demographic factors, race, and child socioemotional and behavioral problems in the present sample have also been previously documented. Reference Palmer, Anand and Graff78 A smaller body of research also suggests that neighborhood violent crime has health implications for young children. Reference Messer, Kaufman, Dole, Savitz and Laraia7,Reference Theall, Shirtcliff, Dismukes, Wallace and Drury79,Reference Beck, Huang, Ryan, Sandel, Chen and Kahn80 Findings from the present study suggest that greater exposure to low SES and higher rates of neighborhood violent crime during pregnancy, which are disproportionally borne by Black families – largely due to structural racism and long-standing inequities Reference Bailey, Krieger, Agénor, Graves, Linos and Bassett81–Reference Bailey, Feldman and Bassett83 – places children at increased risk for behavioral health problems. We also suggest that additional research is needed to further disentangle the overlap between race and neighborhood inequities – including exposure to neighborhood violent crime – especially when examining potential intergenerational impacts, via maternal experience, on child behavioral health.

Our findings advance the current literature in several ways. First, the large sample size enabled assessment of the unique associations between multiple domains of maternal stress exposure – across both maternal childhood and pregnancy – on offspring socioemotional and behavioral development simultaneously. While previous intergenerational research had analytic models that accounted for roughly 12% of variance in child outcomes at age one, Reference Racine, Plamondon, Madigan, McDonald and Tough12,Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins84 our final models accounted for almost twice as much variance – closer to 23%. This increase might in part be due to the use of multiple measures of maternal stress within one model. Second, this is one of the first large-scale studies examining these intergenerational associations to include a large, lower SES, Black sample – increasing generalizability beyond predominately White, and/or economically privileged samples by including individuals who often experience higher levels of multiple stressors (e.g., discrimination, socioeconomic strain). Third, the identification of maternal knowledge of child development as a protective influence provides evidence for resilience-promoting factors in the prediction of child behavioral health. Findings highlight a viable point of intervention: increasing parental understanding of children’s development and appropriate expectations and responses could mitigate the well-documented association between lower SES, histories of maternal trauma, and greater child socioemotional and behavioral problems. Parents with more understanding of normative development are generally more equipped to navigate the challenges of parenting a child in stressful contexts, which may lead to better child outcomes. Reference Leung and Suskind85 Indeed, such anticipatory guidance has been deemed a critical component of pediatrician visits, and has been demonstrated to help promote resilience in the face of childhood adversity. Reference Combs-Orme, Holden Nixon and Herrod86–Reference Moshofsky and Stoeber88

Although the present study has several strengths, some limitations are noteworthy. First, we measured IPV in the third trimester, assessing violence experienced in the past year. It is possible that some IPV was experienced just prior to pregnancy. Second, our measure of maternal childhood trauma was retrospective, and focused on three main forms of traumatic events (physical abuse, sexual abuse, family violence). Although CTE is a well-documented predictor of later mother and child health, Reference Carr, Duff and Craddock89–Reference Collishaw, Dunn, O’Connor and Golding91 broader measures of maternal childhood adversity, such as the 10-item adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg92–Reference Hughes, Bellis and Hardcastle94 may provide different information, and might account for additional variance in offspring socioemotional and behavioral development. In addition, two of our predictor variables (maternal SES risk and neighborhood crime) were weakly to moderately correlated with our moderator variables – suggesting potential lack of independence. As we were not able to establish temporal precedence between these variables, and neither moderator was strongly correlated with our outcome variable, we did not pursue mediational analysis, however future researchers may want to consider these constructs to advance understanding of mechanisms. Regarding, our measure of neighborhood violent crime, given study recruitment and child births spanned 5 years, we were unable to obtain crime statistics for each year to most accurately approximate this prenatal stress exposure. However, as previously noted, violent crime statistics between 2009 and 2012 were quite stable. In addition, given the mobility of our sample during the perinatal period, as well as the large number of neighborhood block groups with very few individuals, we were unable to model violent crime as a higher-order stress exposure. Thus, our models may have biased estimates of regression coefficients by not accounting for the fact that individuals living in the same neighborhood were exposed to the same levels of violent crime, per our measure, and may have had shared experiences of violence. Future intergenerational studies would benefit from utilizing an approach that accounts for this hierarchical relation (e.g., multilevel modeling, where individuals are nested within neighborhoods) when examining associations between neighborhood-level stress exposures and child behavioral health. Finally, another stressor that is especially salient for sociodemographically disadvantaged groups is discrimination. Reference Acevedo-Garcia, Rosenfeld, Hardy, McArdle and Osypuk95–Reference Phelan and Link98 Although such a measure was not available in the present study, previous findings highlight the potential value of its inclusion in future research. Reference Dole, Savitz, Hertz-Picciotto, Siega-Riz, McMahon and Buekens99,Reference Condon, Holland, Slade, Redeker, Mayes and Sadler100

Conclusion

The present findings highlight the importance of examining intergenerational associations between maternal prenatal stressors and child health from a multi-dimensional perspective, especially within populations that experience higher levels of stressors. Our findings build upon existing research that emphasizes multiple opportunities for intervention in order to break the association between maternal risk and child behavioral health problems. Reference Traub and Boynton-Jarrett101 This includes screening for parents’ exposure to childhood adversity and partner conflict, as well as broader, community-level factors, such as violent crime, during pediatric visits and providing referrals for potential interventions to address these challenges. Reference Earls, Yogman, Mattson and Rafferty102,Reference Jutte, Miller and Erickson103 Furthermore, the buffering effects of knowledge of child development emphasize opportunities that primary care providers have with new parents during the pre- and early postnatal period. In addition to anticipatory guidance, providing accessible resources that increase parents’ knowledge of child development can help protect the future emotional and behavioral wellbeing of children in high-risk environments. Reference Traub and Boynton-Jarrett101,Reference Walker, Wachs and Grantham-Mcgregor104 Findings also suggest that policies and community programs addressing the causes of major stress exposures, Reference Jutte, Miller and Erickson103 and interventions that increase parental knowledge of child development, would further benefit child emotional and behavioral health.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the participation of families enrolled in the CANDLE study, as well as the dedication of CANDLE and PATHWAYS research staff and investigators. We are especially grateful to Maureen Sorrells, Lauren Sims, and Ellen Kersten for their significant efforts overseeing and supporting CANDLE data collection and management.

Financial Support

The CANDLE study was funded by the Urban Child Institute, the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 HL109977) and the NIH ECHO PATHWAYS consortium (grant numbers 1UG3OD023271-01, 4UH3OD023271-03). The present study also received support from the CANDLE Developmental Origins of Health and Disease study from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (award number MWG-146331). Dr Bush is the Lisa and John Pritzker Distinguished Professor of Developmental and Behavioral Health and receives support from the Lisa Stone Pritzker Family Foundation and the Tauber Family Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Policy for Protection of Human Subjects) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.