Introduction

Acute mastoiditis remains the most common intra-temporal complication of acute otitis media,Reference Mattos, Colman, Casselbrant and Chi1 with an incidence of 0.12 per 1000 child-years.Reference Thompson, Gilbert, Long, Saxena, Sharland and Wong2 Because of the constrained anatomical boundaries in the middle ear and mastoid air cells, suppuration under pressure can cause bony trabecular destruction and abscess formation. Infection can subsequently spread intracranially, into the neck, or systemically, leading to sepsis, with all such outcomes having potentially devastating consequences.Reference Kullar and Yates3

Management depends on patient presentation, but may include: medical management with intravenous antibiotics; or surgical management such as incision and drainage of the abscess, myringotomy alone, cortical mastoidectomy alone, or myringotomy and mastoidectomy together. Intracranial spread of infection may confer long-term neurological morbidity, and neurosurgical intervention may occasionally be required to prevent or minimise the impact of these complications.Reference Psarommatis, Voudouris, Douros, Giannakopoulos, Bairamis and Carabinos4

Whilst management algorithms have been suggested,Reference Psarommatis, Voudouris, Douros, Giannakopoulos, Bairamis and Carabinos4,Reference Quesnel, Nguyen, Pierrot, Contencin, Manach and Couloigner5 no formal guidelines for the management of acute mastoiditis exist within the UK. Furthermore, given the relatively low incidence of disease, there are few studies with sufficient power to determine optimal management. The rise in antimicrobial resistance and the advent of low radiation dose imaging are also presenting new challenges and opportunities in managing this disease.

We herein characterise the management of acute mastoiditis at our centre and present an algorithm for the management of acute mastoiditis in children.

Materials and methods

Patients were identified using clinical coding data from Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals. Children (aged 18 years and under) diagnosed with acute mastoiditis between 2010 and 2017 were included. The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals include the Freeman Hospital and Great North Children's Hospital, which are tertiary referral centres for paediatrics and paediatric otolaryngology in North East England. The study was registered as an audit with the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Data were collected retrospectively from electronic patient records using a proforma. Data were anonymised and held in accordance with the Caldicott Principles. The data recorded included: patients’ demographic details; length of hospital stay; investigation findings, including modality and timing of imaging; treatments, including details of surgery; microbiology findings; complications of disease; and follow-up duration. Inclusion criteria included any paediatric patient admitted with a clinical diagnosis of acute mastoiditis. Cases with incidental inflammation of the mastoid on imaging were excluded.

Results

Fifty-one cases of acute mastoiditis were identified in 47 patients, but 2 cases were excluded because of the presence of cholesteatoma. No cases were known to be associated with a malignant lesion. Median patient age on admission was 42 months (range, 2 months to 18 years; Figure 1). The median length of hospital stay was 4 days (range, 0–27 days). The number of admissions ranged from 2 to 11 admissions per year, but there was no clear trend over the seven years studied.

Fig. 1. Age of patients at time of admission.

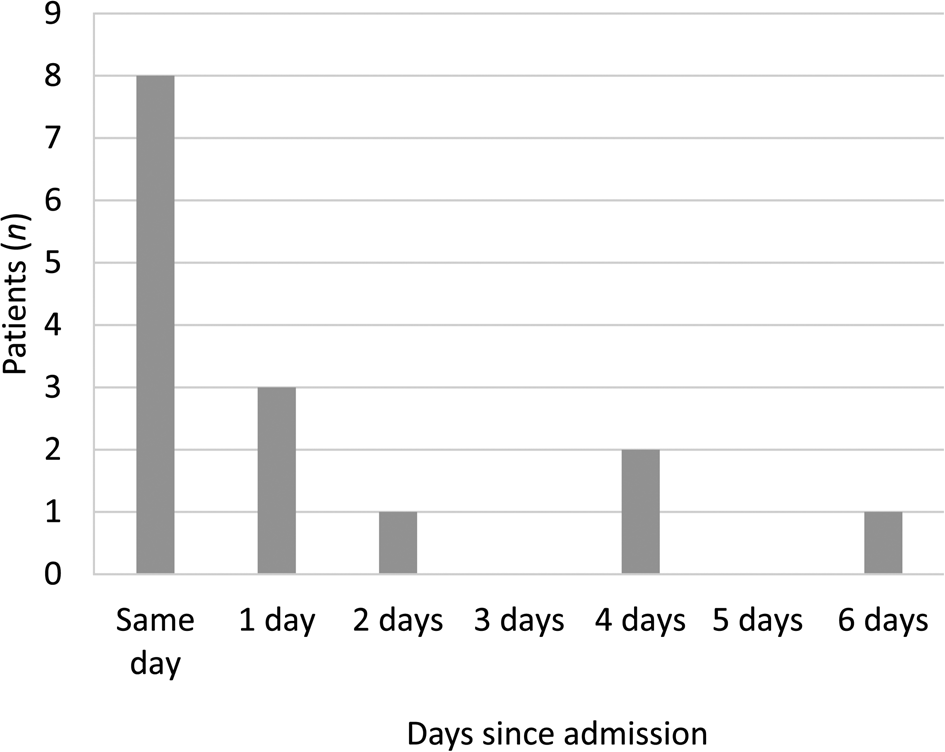

Imaging was conducted in 15 out of 49 cases (30.6 per cent); this consisted of computed tomography (CT) alone (10 of the 15 cases), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) alone (1 case), both CT and MRI (3 cases), or ultrasound alone (in 1 case where CT was not tolerated). This often occurred the same day (in 8 of the 15 cases) or within 3 days (12 cases) of presentation (Figure 2). In all patients who underwent imaging with MRI in addition to CT, this was because of identified or suspected intracranial complications.

Fig. 2. Timing of imaging.

Disease-related complications were common, occurring in 32.7 per cent (16 out of 49) of all cases. Notably, these included sigmoid sinus thromboses (6.1 per cent; 3 out of 49), extradural abscesses (4.1 per cent; 2 out of 49) and abducens nerve palsy (2.0 per cent; 1 out of 49). A full list of identified complications is shown in Table 1. No fatalities occurred in this series. Of the patients who underwent surgery, one developed a wound infection, which resolved with antibiotics. Another case worsened despite grommet insertion and the patient underwent a cortical mastoidectomy. The same patient continued to deteriorate and was taken to the operating theatre for a third time for a revision mastoidectomy, before subsequently improving.

Table 1. Summary of complications of acute mastoiditis

CN = cranial nerve; IJV = internal jugular vein

Microbiological data pertain to swabs taken from the external auditory canal or those taken intra-operatively. We were unable to consistently differentiate from the records whether swabs were taken from the external auditory canal or intra-operatively and therefore pooled the results. The most commonly isolated bacteria were native skin flora (4 out of 49), Streptococcus pyogenes (3 out of 49) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3 out of 49); however, many cases grew a combination of bacteria (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of microbiological swab data

MRSA = Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

All patients received antimicrobial therapy. The selection of empirical antimicrobial therapy was variable (Table 3). Most frequently, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav) was started, either alone (14 out of 49; 28.6 per cent), or in combination with dexamethasone, framycetin sulphate and gramicidin (Sofradex®) drops (5 out of 49; 10.2 per cent). Sixteen out of 49 patients (32.7 per cent) were recorded as having received ear drops, started on admission.

Table 3. Empirical antimicrobial therapy selection

Surgical intervention of any kind occurred in 29 out of 49 cases, most commonly cortical mastoidectomy with (9 out of 29) or without (9 out of 29) myringotomy and grommet insertion. Other procedures included incision and drainage (6 out of 29), myringotomy and grommet alone (2 out of 29), or combined approaches with neurosurgical input (3 out of 29) (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Management options undertaken. I&D = incision and drainage; combined neurosurg input = combined approaches with neurosurgical input

The time until follow up in clinic after discharge was variable. Many patients (22 out of 49) were seen within three weeks after discharge, and the majority (38 out of 49) were seen by four months following discharge.

Discussion

These data present a contemporary summary of the presentation and management of acute mastoiditis in children attending a large tertiary referral centre in North East England, covering a population of approximately three million people.6 We found that acute mastoiditis afflicts a vulnerable patient population, but the incidence of disease remained stable throughout the timeframe examined. This stability in incidence matches the findings from large studies of primary care databases in the UK between 1990 and 2006.Reference Thompson, Gilbert, Long, Saxena, Sharland and Wong2

Our incidence of 49 cases over seven years is slightly higher than that recently presented by a similar centre located elsewhere in the UK.Reference Attlmayr, Zaman, Scott, Derbyshire, Clarke and De7 Our patient population also has an older median age and a wider range than described in studies conducted elsewhere in the UK,Reference Attlmayr, Zaman, Scott, Derbyshire, Clarke and De7 but is within the range described by international studies.Reference Quesnel, Nguyen, Pierrot, Contencin, Manach and Couloigner5,Reference Luntz, Brodsky, Nusem, Kronenberg, Keren and Migirov8,Reference Palma, Fiumana, Borgonzoni, Bovo, Rosignoli and Martini9 The average length of stay was similar to that seen in a similar UK centre,Reference Attlmayr, Zaman, Scott, Derbyshire, Clarke and De7 but was typically less than that seen in international series.Reference Quesnel, Nguyen, Pierrot, Contencin, Manach and Couloigner5,Reference Luntz, Brodsky, Nusem, Kronenberg, Keren and Migirov8,Reference Palma, Fiumana, Borgonzoni, Bovo, Rosignoli and Martini9 The retrospective nature of the study precluded specifying the diagnostic criteria used in each case, but each patient received a clinical diagnosis of acute mastoiditis from an experienced ENT surgeon.

Imaging of any modality was performed in approximately one-third of our population, which is similar to the rate reported in a recent UK series,Reference Attlmayr, Zaman, Scott, Derbyshire, Clarke and De7 and is within the ranges typically described in international series.Reference Groth, Enoksson, Hermansson, Hultcrantz, Stalfors and Stenfeldt10,Reference Laulajainen-Hongisto, Saat, Lempinen, Markkola, Aarnisalo and Jero11 The use of ionising radiation in children is an area of public health concern; children are both more radiosensitive than adults and have more remaining years of life in which to develop a radiation-induced malignancy.Reference Brenner and Hall12 In particular, CT imaging confers a considerably larger dose of radiation than conventional radiography. Indeed, a large retrospective cohort study following up over 178 000 cases of children and young people estimated that an excess of 1 additional case of leukaemia and 1 additional case of a brain tumour occur per 10 000 head CT scans requested in children;Reference Pearce, Salotti, Little, McHugh, Lee and Kim13 therefore, this is rightly an area of concern. It is likely that the risks of intracranial complications of acute mastoiditis outweigh the risks of radiation-induced malignancy; therefore, in cases where such complications are strongly suspected, it seems reasonable to perform imaging.

In recent years, there have been substantial technological advances in cross-sectional imaging, including low radiation dose protocols for indications other than mastoiditis, which do not seem to negatively affect diagnostic quality.Reference Morton, Reynolds, Ramakrishna, Levitt, Hopper and Lee14 There has also been a rise in the popularity of cone-beam CT in head and neck imaging, as yet more often performed for rhinology and facial trauma than mastoiditis.Reference Stutzki, Jahns, Mandapathil, Diogo, Werner and Güldner15 However, cone-beam CT offers distinct advantages in terms of short scanning time and lower radiation doses than conventional CT,Reference Fan, Xia, Wang, Zhang, Liu and Wang16 and therefore may have a role in temporal bone imaging in children with mastoiditis.

Our series revealed that just under one in three patients (32.7 per cent (16 out of 49 cases)) experienced a complication of acute mastoiditis. This figure is higher than that reported in some series,Reference Groth, Enoksson, Hermansson, Hultcrantz, Stalfors and Stenfeldt10,Reference Laulajainen-Hongisto, Saat, Lempinen, Markkola, Aarnisalo and Jero11,Reference Anthonsen, Høstmark, Hansen, Andreasen, Juhlin and Homøe17 but is in keeping with others.Reference Mattos, Colman, Casselbrant and Chi1 The most common complication was sigmoid sinus thrombosis, which occurred in 6.1 per cent of cases (3 out of 49 cases). This might represent an under-estimation of complications, as only a proportion of patients in this series underwent imaging. Patients also underwent heterogeneous treatments, so it remains unclear to what extent treatment options influenced rates of disease complications; this would be a valuable topic for future studies.

Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae were frequently detected in microbiology culture samples, sometimes in combination with other bacterial species, but to a lesser extent than described in other international series.Reference Laulajainen-Hongisto, Saat, Lempinen, Markkola, Aarnisalo and Jero11,Reference Niv, Nash, Slovik, Fliss, Kaplan and Leibovitz18,Reference Croche Santander, Porras González and Obando Santaella19 The lower prevalence in our series compared to international comparisons may reflect the high levels of pneumococcal and haemophilus vaccination in our population. Other species including P aeruginosa were also frequently detected in our population, and have also been commonly detected in other series,Reference Butbul-Aviel, Miron, Halevy, Koren and Sakran20 but could represent contamination from the external auditory canal. We identified S pyogenes as a frequently implicated pathogen, which is in keeping with existing literature.Reference Obringer and Chen21 The sensitivity testing was notably variable across cases. This precludes drawing firm conclusions about antimicrobial prescribing recommendations; rather, we would recommend that all cases be discussed with a microbiologist based on local patterns in antimicrobial prescribing and resistance.

Our population revealed a high proportion of ‘no growth’ samples. There are several possible reasons for this. Firstly, these data were taken from swabs both intra-operatively and from discharge in the external auditory canal (the latter of which may increase the diversity of bacterial species, thereby reducing the chances of detecting one dominant pathogen). We were unable to consistently differentiate from the records whether swabs were taken from the external auditory canal or intra-operatively, and therefore pooled the results. Secondly, we could not determine the timing of initial administration of antimicrobial therapy, which may well have occurred prior to sampling, thus reducing the probability of recovering causative bacteria. These both represent limitations to our study.

Another limitation to this study is its reliance on clinical coding data, which may result in some cases being missed, particularly mild cases that may have been coded with an alternative diagnosis. The absence of data, given the retrospective nature of the study, is a further limitation.

As patients were admitted under different ENT surgeons, the threshold for operative intervention will be subject to some variation. However, overall, the proportion of cases proceeding to mastoidectomy in our series was similar to previous reports from other centres internationally.Reference Quesnel, Nguyen, Pierrot, Contencin, Manach and Couloigner5,Reference Laulajainen-Hongisto, Saat, Lempinen, Markkola, Aarnisalo and Jero11 Although few other large series have reported how many of their procedures involved combined approaches with neurosurgical input, we noted a fairly high proportion (3 out of 49; 6.1 per cent) of cases requiring this in our population.

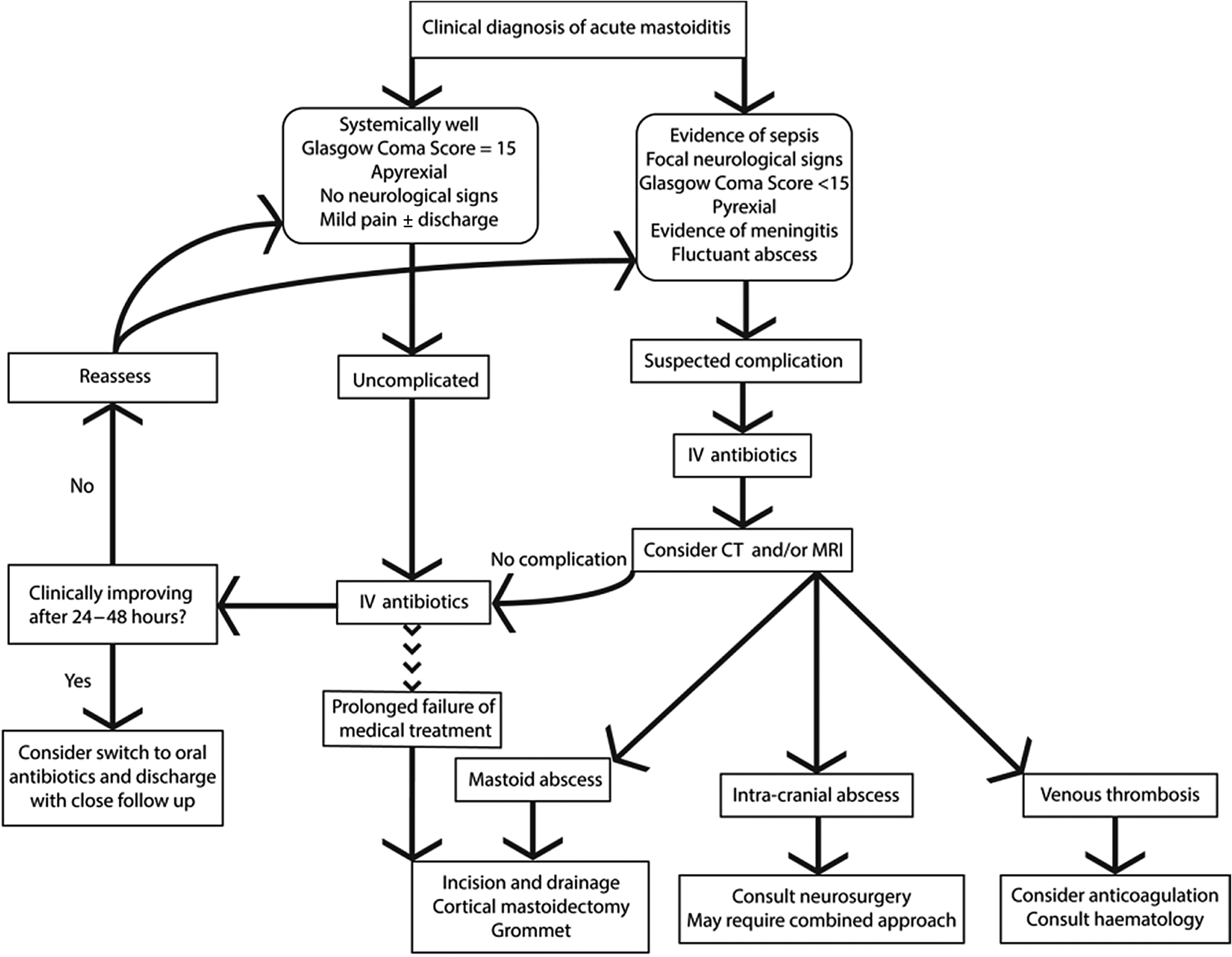

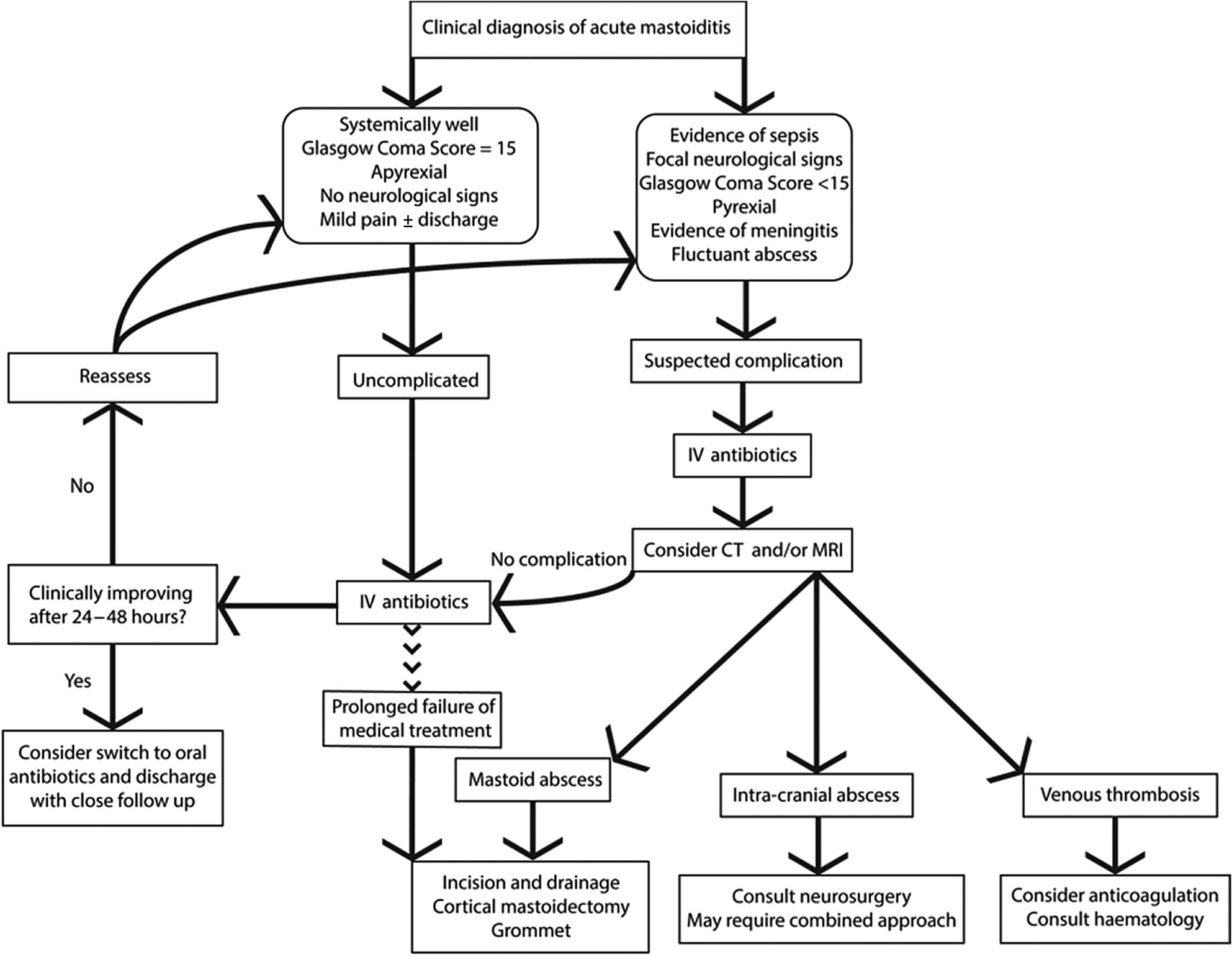

In the absence of formal national guidelines, and based upon author opinion, we propose one possible ‘good practice’ algorithm to guide the management of acute mastoiditis in children (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Proposed algorithm for management of acute mastoiditis in children. IV = intravenous; CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

As demonstrated in our series, many children have good outcomes with medical management alone. However, the threshold for surgical management needs to be commensurate with the clinical presentation. Specifically, in cases where surgical complications are clinically or radiologically apparent (e.g. subperiosteal or intracranial abscess), emergency surgical management requires consideration. Furthermore, in cases that do not initially warrant urgent surgical intervention, but where significant improvement is not seen within 24–48 hours with medical management alone, or if deterioration occurs during any time, cross-sectional imaging is often necessitated to confirm the diagnosis and is potentially valuable for surgical planning. Invariably, all cases require close clinical monitoring and follow up.

The management of acute mastoiditis complications often requires cross-specialty advice. For example, the role of anticoagulation for sigmoid sinus thrombosis in acute mastoiditis is controversial at present; however, the literature seems to suggest that on balance it is likely to do more benefit than harm in an otherwise healthy patient, but that the opinion of haematologists should be sought for each case.Reference Mather, Musgrave and Dawe22 Discrete lesions such as temporal lobe abscesses require discussion with neurosurgical colleagues, and may warrant a combined approach to simultaneously treat the mastoid and the intracranial abscess.

Where there is not a substantial improvement with medical treatment alone, the patient should be considered for a cortical mastoidectomy, myringotomy and grommet insertion. This simultaneously helps eradicate an infective nidus, and permits microbiological sampling to inform an effective antimicrobial strategy.

Following discharge, we recommend that all patients are closely followed up in an out-patient setting to ensure no recurrence of symptoms. One patient in our cohort experienced symptom recurrence. We further recommend formal assessments of hearing as standard in light of the risks posed to hearing by infection itself, the potential use of ototoxic antimicrobial therapy, and operative intervention if required.

As mastoiditis is an uncommon disease, devising appropriately powered studies to define optimal management is challenging. Collaborative multicentre studies are required to pool data, in order to build on our proposed management algorithm and enable the creation of contemporary, evidence-based management guidelines. There is also an urgent need for further bench-to-bedside translation of knowledge studies for the development of novel therapeutic compounds and biomarkers, in anticipation of increasing antimicrobial drug resistance.

Conclusion

Our data broadly mirror those published by other UK centres, particularly in terms of frequency of imaging and surgical intervention, but suggest a relatively high rate of detection of intracranial complications. S pneumoniae was relatively rare in our series compared to international data, which may reflect a high rate of pneumococcal vaccination in our population.

• Acute mastoiditis afflicts a vulnerable patient population; its management is variable and no national UK evidence-based guidelines exist

• Important factors in management, such as imaging technology and disease microbiology, are rapidly evolving, raising questions about contemporary management

• The literature to date, particularly from the UK, consists of small studies insufficiently powered to provide a robust evidence base

• This study, the largest UK series of acute mastoiditis, provides detailed descriptions of management and outcomes

• An algorithm to guide management of acute mastoiditis in children is provided

• Collaborative working is proposed for a sufficiently powered multicentre study, to enable creation of evidence-based guidelines

Larger systematic reviews exist, which provide wide-ranging data on the topic internationally;Reference Loh, Phua and Shaw23 however, at present there are no national UK guidelines to support clinicians in their decision-making, nor is there consensus regarding the minimal outcomes to be reported in case series of acute mastoiditis. With the recent introduction of low radiation dose CT scanning, and the dynamic global changes in microbiology and antibiotic resistance, there is an increasing need to work with multiple centres, in order to pool data and establish contemporary, evidence-based national guidelines, so as to assist clinicians with decision-making regarding children with acute mastoiditis.

Competing interests

None declared