Preamble

The fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1722 cast the Iranian borderlands in the South Caucasus adrift and prompted Peter the Great to advance into the Caspian littoral. A year later, the Ottomans also took advantage of the disorder and sent their troops into eastern Georgia, and the rest of the South Caucasus. The two belligerents almost went to war against one another, but, after mediation by the French, agreed, in 1724, to divide the region. Russia obtained the coastal strip from Darband (Derbent) to Lankarān (Lenkoran), while the Ottomans took over the remaining area.Footnote 1

By 1735, however, Iran, under the leadership of Nāder (shah after 1736) had restored the borders of the former Safavid realm. Following Nāder’s assassination in 1747, Iran experienced what some historians refer to as a fifty-year period of internal anarchy. This was especially evident in the borderlands of the South Caucasus, where the Georgians and local khans competed for territorial gains. In the absence of a central authority in Iran, King Erekle II, the ruler of eastern Georgia (the kingdom of Kʿartʿlo-Kakhetʿi), and the khans, district āqālars (grandees) and soltānsFootnote 2 tried to maintain their newfound autonomy by making alliances with or against their neighbors. The region was soon divided into the semi-independent khanates of Ganjeh (Ganja), Iravān (Yerevan/Erivan), Nakhjavān (Nakhichevan), Qarabāgh (Karabagh), Shakki (Sheki), Shirvān, Darband, Qobbeh (Kuba), Tālesh (Talysh) and Bādkubeh (Baku), as well as semi-autonomous districts, such as Qazzāq (Kazakh) and Shams al-Din (Shamshadil), Shuragel, Elisu and Jar-o-Taleh (Jar-o-Belokan) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. South Caucasus in 1800.

Source: Tsutsiev, Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, 14.

The chaotic situation in Iran, as well as the inability of the Ottomans to challenge Russia, prompted a number of Russian statesmen, led by Gregory Potemkin, to urge the Russian empress, Catherine II (r. 1762–96), to agree to a bilateral treaty of friendship (the Georgievsk treaty of 1783) with King Erekle. In exchange for Russian protection, Erekle, who feared a renewal of Iranian suzerainty, abjured his loyalty to Iran. Russia guaranteed Georgia’s territorial integrity and the continuation of the Bagrationi dynasty in return for having a voice in the conduct of Georgian foreign affairs.

Despite pressure from a number of her advisors, Catherine refused to get involved in the quarrels among the Muslim khans in the South Caucasus, who sought to keep their domains and revenues at any cost. The situation changed drastically after 1794, when Āqā Mohammad Khān Qajar consolidated his position as the new ruler of Iran. Angered by Erekle’s “betrayal” and learning of the independent actions of the khans of the South Caucasus, he invaded the region in 1795. Most of the region either submitted or was looted. Āqā Mohammad then proceeded to Tiflis, the capital of Erekle. After intense fighting, Erekle fled and Āqā Mohammad Khān’s army plundered the city for two weeks, killing many and taking thousands of women and children as slaves.

Catherine, who viewed the attack on Georgia as a direct insult to Russia, ordered Valerian Zubov, the brother of her then favorite, Platon Zubov, to invade the South Caucasus, march into Iran, depose Āqā Mohammad Khān and replace him with his brother, Mortezā-Qoli Khān, who had sought refuge in Russia. Āqā Mohammad Khān’s campaign in Khorasan and Zubov’s promise to keep any khan who submitted to Russia in his post convinced the khans to either, in the case of the khans of Iravān and Nakhjavan, open negotiations with the Russian commander or, in the case of the khans of Darband, Qobbeh, Badkubeh, Shakki, Shirvān, Qarabāgh and Ganjeh, to submit to Russia. However, Catherine’s death in November 1796 put an end to the Russian campaign. Her son, Tsar Paul (r. 1796–1801), recalled the Russian army and dismissed the Zubovs.

Now crowned shah, Āqā Mohammad returned to the South Caucasus in the spring of 1797. All the khans either submitted, fled, or were ousted. But his assassination in June 1797 once again plunged the region into a brief period of uncertainty.

Prelude to War

The political situation in Iran soon stabilized, when Bābā Khān, the nephew of Āqā Mohammad Shah, overcame his rivals and ascended the throne as Fath–ʿAli Shah (r. 1798–1834). The new shah sought to reassert Iranian sovereignty over Georgia and the khanates across the Aras (Arax) River. For the next several years, however, the shah did nothing more than send messages to the Georgian princes and the khans, soltāns and Āqālars of the South Caucasus reminding them that they were subjects of Iran.Footnote 3

Meanwhile, following the murder of Tsar Paul, his son, Tsar Alexander I (r. 1801–25), not only reinstated his grandmother’s generals, but also her final plan for the Caucasus. On 12 (24) September 1801,Footnote 4 the tsar issued an imperial proclamation annexing eastern Georgia to the Russian Empire. A year later, on 20 September 1802, the tsar, displeased by the mismanagement of the Russian governor of Georgia, General Karl Knorring, and his deputy, Peter Kovalenskii, recalled them both and appointed a Russianized Georgian prince,Footnote 5 Lieutenant-General Paul Dmitrievich Tsitsianov,Footnote 6 not only as the commander-in-chief and governor of Georgia, but also the inspector of the Caucasian Line, military governor of Astrakhan and chief of the Caspian flotilla.Footnote 7

Tsitsianov arrived in Tiflis on 13 February 1803 and, following the tsar’s instructions, exiled the entire Georgian royal family to Russia.Footnote 8 Having been given full authority over the Caucasus, Tsitsianov, who was among the officers who had accompanied Valerian Zubov during the 1796 campaign, wished to complete the latter’s unfinished mission—that is, to bring back the khanates that had accepted Russian suzerainty in 1796 and expand Russian rule from the Caspian to the Black Sea.

Several days after his arrival, Tsitsianov began to send letters to some of khans of the South Caucasus reminding them of their submission to Russia in 1796.Footnote 9 He also began making preparations to advance toward Ganjeh and Yerevan, while, at the same time, seeking to bring some of the principalities of western Georgia under his control and to secure Georgia from Lezgi raids. Lezgi tribesmen had settled in Jar-o-Tale and, further east, in Elisu (see Figure 1) and, throughout the eighteenth century, had raided Georgian villages. Between April and May of that year, Major–General Vasilii Semenonich Guliakov and Prince Luarsab Orbeliani reported to Tsitsianov that they had subdued the Lezgis in a number of campaigns, and that the latter had agreed to be subordinate to Russia and to pay tribute.Footnote 10

Feeling secure from the west and the north, Tsitsianov now looked to the east and south. Ganjeh’s close proximity threatened Tiflis. In fact, it had served as a direct route for Āqā Mohammad’s invasion in 1795. The governor of Ganjeh, Javād Khān Qajar, who had guided the Iranian army to Tiflis in 1795, had submitted to Zubov in 1796, and had renewed his loyalty to Iran in 1797, realized his precarious position and sent a friendly message to Tsitsianov soon after the latter’s arrival in Tiflis. On 9 March, Tsitsianov replied stating that he had received Javād’s envoy, Gorgin Beg, and was pleased that the khan had indicated a desire for union, peace and friendship between the two neighboring states. Nevertheless, he asked that, in order to show his loyalty and good intentions, Javād send his eldest son, Ughurlu Āqā, to remain as a well-treated hostage in Tiflis. He dispatched Gorgin Beg with a gift of ten arshins each of velvet and satin.Footnote 11

Meanwhile, Tsitsianov put pressure on the notables of Qazzāq and Shams al-Din, the districts adjacent to Ganjeh (see Figure 1), to refute their allegiance to Ganjeh and Iran and to become subjects of Russia.Footnote 12 Aware of the absence of a large Russian force and artillery needed to start a major war with Iran, Tsitsianov, like Zubov, planned to use threats and promises to convince the khans of the South Caucasus to switch their allegiance to Russia. In exchange for swearing loyalty to the tsar, the khans could remain in charge of their khanates, keep their estates, collect the revenues and administer justice. In exchange they would be required to send an annual tribute to Tiflis, house and feed a Russian garrison, and send a family member to Tiflis as a well-treated hostage at Russian expense.

Learning that Tsitsianov planned to place Ganjeh under Russian suzerainty, Javād Khān sent an urgent message to Fath-ʿAli Shah and began to fortify the city.Footnote 13 The shah, who was busy attacking Mashhad, sent his private attendant and gholām, Saʿid Khān Dāmghāni, on a speedy horse to inform Javād Khān of his imminent arrival with an army.Footnote 14

Although by the end of summer Tsitsianov had brought Kazakh and Shams al-Din under his control and had secured his invasion route, he did not have a sufficient force to attack Ganjeh and was forced to await the arrival of two more regiments—the Sevastopol Musketeers and the 15th Rifle (Jäger) Regiment—in order to move on Ganjeh. The Sevastopol Musketeers arrived on 23 November and set up camp ten versts from Tiflis, on the plain of Kartizkar.Footnote 15 On 24 November, the 15th Rifle Regiment was still seventy versts from Tiflis. Both regiments were exhausted from traveling through mountain roads in bad weather conditions.Footnote 16 The number of the Sevastopol Musketeers had been reduced from three to two regiments due to illness; there were also not enough horses for three regiments. Tsitsianov thus ended up with two battalions of young and inexperienced recruits, who, according to him, were tired after marching only fifteen versts. As to the 15th Rifle Regiment, he decided to leave it behind.Footnote 17

In the end Tsitsianov’s forces consisted of six battalions and three squadrons:Footnote 18 two battalions of the Sevastopol Musketeer Regiment; two battalions from the 17th Rifle Regiment, stationed at Shams al-Din; one battalion of the Caucasian Grenadier Regiment; three squadrons from the Narva Dragoons Regiment; two companies belonging to the main battalion of the 17th Rifle Regiment; and the remaining two companies of the same battalion which were to join him after their return from Vladikavkaz where they had gone to escort the Georgian Queen Darejan.Footnote 19

The army was to gather on 2 December in the village of Soqānlu, fifteen versts from Tiflis. 3 December was designated as a rest day; they were to move on 4 December. After a six-day march the troops reached the Zagial (Zaghali) village in Shams al-Din where, on 10 December, they were joined by the two battalions from the 17th Rifle Regiment.

On 10 December, Tsitsianov sent a letter from his camp to Javād Khān, which read:

Having arrived within the borders of Ganjeh I wish to relate my reasons for coming here. First and foremost: Ganjeh and its environs from the time of Queen TamarFootnote 20 belonged to Georgia and was lost due to the weakness of the Georgian kings. Since the Russian Empire has placed Georgia under its rule and protection it could not leave Ganjeh in the hands of foreigners. Second: Upon my arrival in Georgia, I wrote to you asking you to send your son as securityFootnote 21 [and to secure our friendship], but you answered that you feared Iran’s ruler. You totally ignored the fact that six years before you had accepted Russian protection, and that Russian troops were in the fort of Ganjeh. Third: Merchants from Tiflis who were robbed by your people did not receive any compensation from your high-ranking person [the khan]. For these three reasons, I, with my troops, am on my way to take your city. However, following European custom and not wishing to shed blood I ask you to surrender the city and demand that you answer in two words—that is, will you surrender it or not? You must realize that since my troops have already crossed into your domain, there can be no other discussion except your voluntary surrender, after which you shall witness the benevolence of my sovereign, His Imperial Majesty.

If you do not wish to do so, then you must await the same misfortune that befell Izmail,Footnote 22 Ochakov,Footnote 23 WarsawFootnote 24 and other cities. If I do not receive an answer by noon tomorrow then the battle shall commence and you shall witness the force of my fire and sword and shall know that I keep my word.Footnote 25

Javād Khān’s reply was as follows:

I have received your letter which stated that Ganjeh belonged to Georgia in Queen Tʿamar’s time. No one has heard this claim; in fact, Georgia was ruled by our ancestors, ʿAbbās-Qoli Khān and others. If you do not believe this, ask the old men of Georgia whether ʿAbbās-Qoli Khān was the governor of Georgia or not. He built mosques and shops [which are still standing] and granted various honors (khalʿat) to the Georgians. The border of Ganjeh and Georgia has been established since the time of Erekle Khān. Despite our historic claim [to Georgia] we have never mentioned this. If we were to state that our fathers had been the vālis (viceroys) [of Georgia], no one would agree to return it [Georgia] to us. As to your statement that six years ago we handed the fortress to the Russian king, it is true, for at that time the Russian ruler controlled all the Iranian [provinces in the South Caucasus]. We agreed to accept the orders of the Russian ruler, who was also in control of Georgia. We are still in the possession of the [Catherine’s] writ that named us the beglerbegi (governor) of Ganjeh and not a subject of Georgia. However, at the time when we accepted the suzerainty of the Russian ruler, the shah of Iran (Āqā Mohammad Khān) was in Khorasan and we could not reach him [ask him for help]. Now thanks to Allāh, the Iranian shah is nearby and his gholām has arrived with the news that the Iranian army is on its way. You also stated that Georgia belonged to the Russian king and that I had no right to confiscate the goods of its merchants. You are correct. But when you had first arrived in Georgia and I wrote to you and asked you to return Nasib [Beg],Footnote 26 our subject who had turned against us and had usurped the goods of our merchants [from Shams al-Din], I was sure that you would return both him and the stolen goods, but you did not do so. I confiscated the goods of the people of Ganjeh and Shamkhor and not those belonging to Georgians. If you are threatening to do battle with me, I am ready. If you are proud of your cannons, I have cannons as well. If your cannons are one ārshin wide, mine measure four ārshins. Victory is in the hands of Allāh. Are you sure that your troops are braver than the [Iranian] qezelbāsh?Footnote 27 So far you have dealt with your own kind [Europeans] and have not faced the qezelbāsh. From the moment you came to Shams al-Din and have subjugated our subjects, we have made preparation. If it is war you want, you will get war. As to your words that misfortune will befall us, it was your misfortune to leave Petersburg, and you shall experience another misfortune here.Footnote 28

Tsitsianov arrived in Shamkhor on 11 December. On 12 December, he issued a proclamation to the Armenians in the khanate of Ganjeh, promising them the protection of the Russian emperor. He added that their lives and property would be safeguarded, they would be free from their Muslim oppressors, and they could settle in any part of Georgia. He concluded by stating that Georgia was now under Christian rule; it did not belong to any meliksFootnote 29 or other landowners, and they could live as state peasants.Footnote 30

The Siege

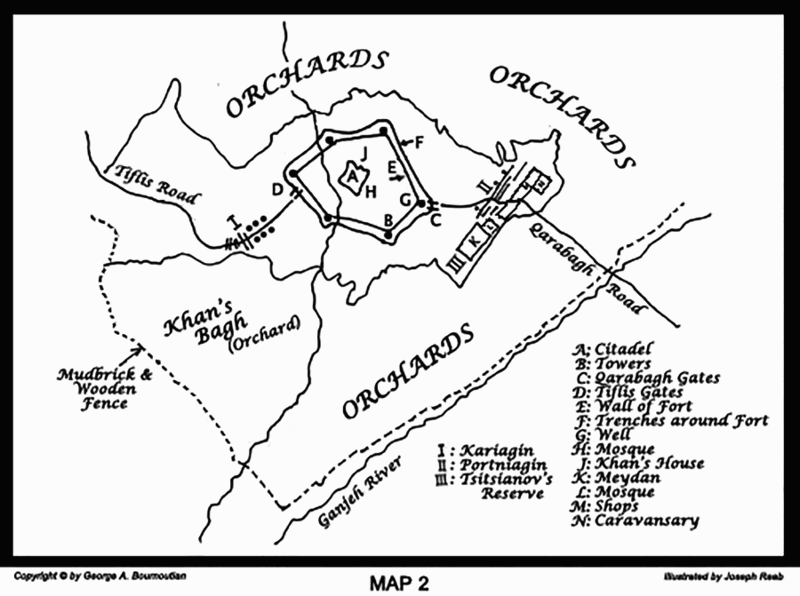

On 13 December, Tsitsianov ordered his troops to cross the Kochkhor stream. The next day (14 December), not having the plan of the city of Ganjeh and its surrounding terrain, he went to personally reconnoiter the land. He also wanted to occupy the large and thick orchards that surrounded the fortress (see Figure 2). He took the TatarFootnote 31 light infantry of Major-General Portniagin,Footnote 32 together with one squadron of the Narva Dragoons, two battalions of the 17th Rifle Regiment commanded by Colonel Kariagin,Footnote 33 the Caucasian Grenadiers commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Simonovich,Footnote 34 and seven field guns. Upon reaching the orchards, and realizing that the fortress was not visible from there, Tsitsianov decided to occupy the orchards. He divided his troops into two groups: The first was composed of the Caucasian Grenadiers with the light infantry and two field guns, under the command of Simonovich; the other was composed of two rifle battalions, a dragoon squadron and five field guns and light infantry under his own command. The first he sent to the main Tiflis road, while he, together with the second group, went to the right of that road to the khan’s orchard.Footnote 35

Figure 2. The Siege of the Ganjeh Fortress

Source: Dubrovin, Zakavkaz’e, 230–31.

The Russians met fierce opposition in the orchards. Mud-brick walls and fences forced the Russians to face gunfire. Despite all this, in two hours the Russians managed to almost clear the thick orchards of all enemy forces and reach within one and a half versts of the fortress. The enemy withdrew into the fort, having lost 250 men, most to Simonovich’s units. Some 200 Shams al-Dinlus and 300 Armenians, who were kept in Ganjeh by force, surrendered to the Russians.Footnote 36 The Russian losses amounted to seventy dead and thirty wounded.

That same day the batteries were set under cover and the rest of the 2nd battalion joined the troops. The next day (15 December) the two squadrons of dragoons and the rest of the battalion joined. The fortress was surrounded and the bombardment began. Tsitsianov felt that Javād Khān, faced with fire and siege, would falter from fear and surrender the fort; especially since each day people fled the fort and reduced its garrison.

On Wednesday 21 December Tsitsianov sent another message to Javād Khān, which read:

Prince Tsitsianov, leading the glorious Russian army, commander-in-chief of Georgia, Astrakhan and the Caucasus, chief of the Caspian flotilla, holder of many medals and cavalier orders, etc., is, following the European custom, once more asking the high-ranking Javād Khān of Ganjeh if he is willing to surrender the fortress to the Russian commander or not? The answer must be given tomorrow morning. To assure the safety of the messenger, he has to have a white cloth attached to a pole.Footnote 37

Javād Khān, in order to gain time and hoping for the arrival of the shah’s army, replied that since the next day was Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath,Footnote 38 he could not send a courier. But on Sunday he would dispatch a man with conditions. He added that if Tsitsianov’s offers were favorable he would also reply in a favorable manner.Footnote 39

Javād Khān’s reply did not satisfy Tsitsianov. He sent another message, which read:

Prince Tsitsianov informs the high-raking Javād Khān that he has received his letter and that he is not proposing conditions; rather, from the kindness of his heart he advises the following: TomorrowFootnote 40 [23 December] we celebrate the birthday of His Imperial Majesty, the most benevolent emperor. If the high-raking khan sends the keys to the city with his son, Hoseyn-Qoli Āqā, who will stay with us as security, to the commander of the Russian troops, then the high-ranking Javād Khān will witness the generosity handed to him by our benevolent Sovereign.

If this is not done by noon tomorrow, then war will commence and the commander of the Russian troops swears by the living God that the storm will bring rivers of blood of the unfortunate, who although of different faith, he would still pity because of his humanity.Footnote 41

Javād Khān continued to delay, and a few days later asked that Tsitsianov send a Kazakh named Mahmad (Mohammad), but Tsitsianov refused and on 7 January 1804 sent another message, which read:

Prince Tsitsianov, lieutenant-general, etc. has received the letter from the high-ranking Javād Khān of Ganjeh, in which he asks for us to dispatch a Kazakh named Mahmad. We reply that there are many Mahmads among the Kazakhs, thus we do not know which Mahmad is needed. The high-ranking khan is well aware of the conditions of the Russian commander. Furthermore, all proposals must be in writing and not verbal. In conclusion, we add that no one in the world has heard that Russian troops, after besieging a fort, [ever] retreated without its surrender or storming it. Surrender will bring prosperity, while resistance will shed blood. God will show in whose hands Ganjeh will remain.Footnote 42

Javād Khān kept on asking for Mahmad the Kazakh, and on 9 January Tsitsianov once again sent a message, which read:

For the past three days you have asked us to send the Kazakh Mahmad for your reply. I inform you, in the name of his father, that there are many Mahmads. Do not send any more such requests. I have concluded that I have to explain my feelings to you. My faith disdains your Asiatic pride, which will result in spilling human blood, and because I do not wish to have that blood on my conscience, I, according to European custom, state that those under siege can ask for a truce and those who have laid siege can agree to a time period. During that time neither side can fire on the other, while each side sends its proposals [for surrender]. After that, either war commences or the city is surrendered. I witnessed this protocol during the siege of four fortresses. After this proposal God will see if I am at fault for shedding blood on the day of storming the fortress. I expect an answer to this today.Footnote 43

The next day, the khan asked if he could send Mirzā Mahmad-Oghli and added that Tsitsianov’s conditions were such that no one could accept them. Furthermore, since Tsitsianov’s messages were so severe, he had to expect the same type of a reply. He concluded with the following:

You write that you will storm the fortress; we have ways to resist that and, relying on God, do not worry. You have written that during negotiations your rules forbid the firing of weapons, but according to our custom, when the enemy is this close, one can fire its cannons and firearms. You also write that during the storming of the fort human blood shall be spilled. That will be your sin. If you do not attack your blood will not be spilled, but if you attack then it will flow; both the blood and the sin is yours. You state that by Christian law spilling blood is a sin. But according to our Muslim law, when someone attacks by force and blood is spilled then there is no sin in retaliating. You have asked that I answer today; you can make such demands from your servants. I am not afraid of anyone. I shall answer when I wish to do so. Your envoy is a Qarabāghi who is afraid to return. I am sending you my reply with another man.Footnote 44

While all these messages were being sent the situation in the fort was desperate. The garrison needed firewood and although there were enough provisions, there was no barley for the horses. The water canals, which the Russians could not take, were piled with corpses and disease was spreading. Tsitsianov’s own troops suffered from the lack of drinking water and his supplies, enough for two weeks, were dwindling. He threatened that he would take the city and the khan would suffer a shameful death. Javād Khān replied that he would fight and die on the ramparts.Footnote 45

On 10 January Tsitsianov sent a fifth and final message, which read:

I gather from your reply that you have no intention of surrendering the fortress. I am sending you, for the last time, the conditions of surrender that will be acceptable to my liege, His Imperial Majesty and to his army. Your request that I do not attack and that by European custom I should not spill blood cannot go without a reply. I shall never send the Kazakh Mahmad to you. All messages will be relayed by prisoners and not through the major who was previously sent to you. The reason is that there have been cases in Persia [Iran] where an envoy was not treated in the same manner as in Europe and Turkey [Ottoman Empire]. When I ask for a swift reply it does not mean that I consider the receiver my servant, it is but a part of human courtesy. When I reply to your letters that same day, then you also must give me the same courtesy, which is not my custom but the custom throughout the world. I await your response to the following conditions by noon tomorrow:

(1) Javād Khān of Ganjeh and all the citizens of Ganjeh will become the subjects of His Majesty, the Russian emperor.

(2) The fortress will be emptied of all troops and be handed over to the Russian army.

(3) Javād Khān of Ganjeh, as a Russian subject, will keep his post as governor and will pay 20,000 rubles a year in tribute,Footnote 46 which he has to pay for the year 1804 upon the signing of the agreement.

(4) The Russian garrison in Ganjeh, as well as the Russian troops stationed in Shams al-Din will receive annual provisions and fodder amounting to 2,605 Ganjeh taghār sFootnote 47 of wheat; 243½ taghārs of buckwheat; 601½ taghars of barley, which in local prices are valued at four rubles per taghār for wheat; six rubles for buckwheat; two rubles and 40 kopeks for barley. The said grain must be weighed and recorded by the Russian commandant of Ganjeh.

(5) The khan shall have no authority over the province of Shams al-Din and its inhabitants. They shall be, as they are at present, under the administration of Georgia.

(6) In order to show his loyalty, the high-ranking Javād Khān must hand over his son Hoseyn-Qoli Āqā as security to the commander-in-chief of Georgia to remain in Tiflis, where 10 rubles a day will be allocated for his livelihood in comfort.Footnote 48

The Storming of the Fortress

The siege had lasted a month. Javād Khān, still hoping for the arrival of the approaching Iranian army, led by ʿAbbās Mirzā, refused to accept Tsitsianov’s final and, frankly, impossible terms to continue in his post as a Russian subject.

Several days later, Tsitsianov held a war council composed of one general, two colonels and one lieutenant colonel. They decided to storm the fort in the early morning of 15 January.

Major-General Portniagin was instructed to lead the storming of the fort at 5:30 am and was told to move into position half an hour before the attack under the cover of darkness in total silence, together with the posts of Captain Chuiko the quartermaster. The Russian standards were to be taken to the square near the mosque outside the fort (see Figure 2). The Cossack line surrounding the fort had to remain at their posts and had to move forward once the bombardment began. The rest had to remain in reserve hidden from bombs and bullets.

The troops were divided into two columns: The first, composed of two battalions of the 17th Rifle Regiment, under their commander Colonel Kariagin, were to go left and attack the Tiflis (also called the Citadel) Gates. This column was to falsely convince the defenders that it was the main point of attack. The second, which consisted of the Grenadier battalions, the Sevastopol regiment, the battalion of the Caucasian Grenadiers under Lieutenant-Colonel Simonovich, and 200 special dragoons under the general command of Major-General Portniagin; were to go to the right and attack the Karabagh or Upper Gates under the artillery fire of Second-Lieutenant Bashmakov (see Figure 2).

The battalion of the 17th Rifle Regiment of Major B’elavin, with Tsitsianov himself, was held in reserve and stationed itself at the meydān (square) across the Karabagh Gates, the center of the attack. In front of the Tiflis Gates, the battalion of the Sevastopol Musketeer regiment was stationed to stop the exit of the enemy and, if need be, to come to the aid of the forces leading the storming of the fort.

The entire artillery consisted of eleven field guns, three of which were three-pound cannons, which were kept with the reserves along with 100 Cossacks. Finally the Tatar cavalry, which was unreliable in its loyalty, was to join the attackers. The line around the square and the orchards was to be held tight. Strict orders were given to safeguard the women and children and no looting was to be permitted. Tsitsianov appointed special guards to oversee this after the taking of the fort.

The troops reached their post by the earthen redoubts quietly at 5:30 under the cover of darkness, in order to place ladders against the walls. The maneuver was so successful that the defenders only realized it and opened fire when the Russians had reached some 100 feet from the wall and had begun to climb up the ladders. The defenders threw rocks, fired guns and threw nafta fireballs.

Colonel Kariagin, although he was to stay in place and feign an attack, heard the drum rolls of Portniagin’s troops and, seeing some of them climbing to the top, took advantage of the chaos and ordered that ladders be placed on his side as well and reached the ramparts before Portniagin’s forces. Taking the tower and its cannons, Kariagin dispatched Major LisanevichFootnote 49 with a battalion to take hold of two other towers. According to the Russians, Javād Khān was killed defending one of the towers and Lisanevich then managed to open the gates.Footnote 50

Second column, led by Major-General Portniagin, did not have similar success at first. The terrain at the breach was not suitable and Javād Khān had placed his main defenses by that gate. Portniagin, therefore, abandoned the breach and decided to ascend the ramparts using ladders. After he reached the top, the rest of the troops followed and managed to take hold of three other towers. After taking over all the towers the troops descended by long fourteen-arshin ladders into the city by the stone wall, which was four sazhen tall, despite the heavy fire directed at them from the bottom.

A terrible sight was to be seen in the city. Tatar infantrymen and cavalry sought the khan’s headquarters and began to loot.Footnote 51 Women were running out and screaming in the streets; the troops were clearing the streets of defenders. Both sides fought mercilessly. A son of Javād Khān, Hoseyn-Qoli Āqā, was killed in the process.

The entire attack took some one and a half hours. By noon everything was quiet and the city was covered with corpses. The next day, 16 January, only some 500 local Muslim fighters, who had taken refuge in the mosque, remained. No one knows if they wished to surrender or not. However, an Armenian told the Russian soldiers that there were some Lezgis among them. That was the signal (to the Russians, many of whose comrades had died fighting the Lezgis), to kill everyone in the mosque.Footnote 52

Ironically, none of the Iranian primary sources mention the long negotiations during the month-long siege. They relate the entire episode in less than half a page, and state only that Javād Khān made a number of sorties and fought bravely against the Russian guns, that Nasib Beg and some Armenians left the field of battle and joined the Russians, and that Javād Khān was forced to go back into the fort to defend it. In the end, they relate, the disloyal Armenians of Ganjeh aided the Russians in capturing one tower, whose defenders were slacking. After that the Russians entered the city, and murdered and looted for three hours. A great number of people were killed,Footnote 53 the blood of the dead was described as flowing in waves. After that they drove the Muslims out and populated the city with Armenians.Footnote 54

Tsitsianov’s official report to St. Petersburg paints a very different picture. The enemy dead totaled 1,500; and a total of 17,224 (8,585 men and 8,639 women) were taken prisoner.Footnote 55 The Russian dead amounted to three officers and thirty-five soldiers, while fourteen officers and 192 soldiers were wounded.Footnote 56 It proudly adds that not one of the 8,600 women who were taken into the fortress from the surrounding villages, to assure the loyalty of their men, was molested, and that not one child was killed—a claim that is very difficult to believe, since other sources list the Muslim dead as being between 1,750 and 3,000.Footnote 57

The Russians captured nine bronze field guns, three cast iron cannons, six falconets, eight flags, fifty-five puds Footnote 58 of gunpowder and a large supply of grain.Footnote 59

In order to signal the permanent annexation of the city, Tsitsianov asked the tsar’s permission to rename the city in honor of the emperor’s wife Elisaveta Alexeevna—Elisavetpol.Footnote 60 Ganjeh and the rest of the territory of the khanate became known as the Elisavetpol District and was annexed to Georgia. The tsar awarded Tsitsianov the rank of general of infantry and the medal of St. George 2nd class.

According to Russian accounts, Tsitsianov ordered that 900 rubles be allocated for the khan’s family, for them to have a house in the main square, some carpets, four chetverts Footnote 61 of wheat and twenty chetverts of rice and the same amount in millet.Footnote 62 The main wife of the khan, Begum, who was the sister of Mohammad-Hasan Khān of Nukha (Shakki), asked Tsitsianov to be allowed to go to her brother, who had sent a similar request to the Russian commander. Russian historians claim that she was permitted to leave and add that Tsitsianov’s benevolence and generosity made the Russians look very good in the eyes of the Asiatic throng.

The news of the destruction of Ganjeh, the death of Javād Khān Qajar, his son and many Muslims caused an uproar in the Iranian court. On 11 March, Fath-ʿAli Shah gathered his army and summoned tribal forces from the provinces to his camp at Soltāniyeh. In April of that year the shah and ʿAbbās Mirzā crossed the Aras River into Nakhjavan and moved toward Iravān to face Tsitsianov, who was sending similar threats to Mohammad Khān of Iravān.Footnote 63 The large Iranian army forced the Russians to retreat with great losses. This first armed conflict with Russia started a ten-year struggle, better known as the first Russo-Iranian War (1804–13). Thus, Tsitsianov’s reckless ambition forced St. Petersburg into a long war with Iran (and soon the Ottoman Empire, 1806–12) at a time when Napoleon threatened Russia and the rest of Europe.

Aftermath

Over the next three years, Tsitsianov, despite his unsuccessful attack on Iravān, not only brought most of the western Georgian principalities and the district of Shuragel under Russian control, but signed treaties with the khans of Sheki, Shirvān and Karabagh, by which, in exchange for retaining their khanates, they swore allegiance to Russia, paid an annual tribute, permitted a Russian garrison in their main city, and sent hostages to Tiflis (see Figure 1).Footnote 64 On 20 February 1806, after making a similar arrangement with the khan of Baku, Tsitsianov was shot outside the gates of that city by one of the khan’s attendants.

Greatly admired by all nineteenth-century Russian historians, Tsitsianov has also been described, by revisionist historians, as a bombastic and self-serving soldier, who saw Asians, and especially Iranians, as loathsome and treacherous.Footnote 65 One Iranian chronicler describes him as the one who “shed the blood of innocent people, which flowed like a flood,”Footnote 66 while the local Turkish-speaking population, in a play on words on his title of “inspector (of the Caucasian Line),” referred to him as ishpokhdor (“his deeds resemble excrement”).Footnote 67

If one is to accept the veracity of Tsitsianov’s letters to Javād Khān, he did everything to avoid bloodshed in Ganjeh. However, some modern western historians point out that Tsitsianov, having laid a month-long siege, had no wish to lose face and retreat without taking Ganjeh, the strategic proximity of which endangered Tiflis. In addition, Javad had to be punished for his role in guiding Aqa Mohammad to Tiflis. He thus proposed impossible conditions. His small army could not face the approaching large Iranian force.Footnote 68 His financial and military resources could not sustain a major war in the South Caucasus. If Ganjeh surrendered, he would feel secure to attack Yerevan, as well as gain much needed cash and provisions. However, if he took Ganjeh by storm, he would demonstrate the might of the Russian army and frighten the khans of Shakki, Qarabāgh, Shirvan and Bādkubeh into accepting Russian suzerainty (as they did indeed).Footnote 69 His letter to Count A. Vorontsov, dated 15 January, clearly states that the raising of Ganjeh had not only put the fear of Russia into the “Asiatics,” but would facilitate the trade between Georgia and the Caspian Sea.Footnote 70

In retrospect, Tsitsianov was neither the great humanitarian portrayed by his Russian contemporaries nor was he the terrible ogre painted by the Iranian chroniclers. In fairness, except for the campaigns against the Lezgis, Ganjeh, and in his failed attempt to take Yerevan, Tsitsianov did manage to peacefully and without any significant bloodshed bring the khans of Shakki, Qarabāgh, Shirvān and (temporarily) Bādkubeh into the Russian orbit. The khans swore loyalty oaths to the tsar, permitted a Russian garrison to be stationed in the center of their khanates, sent hostages and paid a total of some 25,000 gold rubles (75,000 silver rubles) in annual tribute to Tiflis, which refilled the almost empty treasury of Georgia. In exchange, the khans remained in their posts, collected the revenues and oversaw the administration of their domains for the next fourteen to seventeen years.Footnote 71 One can state categorically that Tsitsianov, despite all his faults and short-lived command, played, in the long run, a major role in the Russian conquest of the Caucasus.

Finally, objective historians have to note that Fath-ʿAli Shah did not possess the military prowess of Āqā Mohammad Khān. Aside from making threats, he did nothing between 1801 and 1803 to push the Russians out of the South Caucasus. The shah’s main concern was to keep his throne, his large harem and his revenues. The Iranian army, under the command of the fifteen-year-old Crown Prince ʿAbbās Mirzā was not prepared to face the more modern Russian armies and, if not for Russia’s struggle against Napoleon, Iran would have lost the “First Russo-Iranian War” long before its conclusion in 1813. Moreover, there was no territorial or religious unity, or ethnic/national identity, among the numerous khans of the South Caucasus. Their main interest was to keep their individual posts and revenues. Thus, with few exceptions, they accepted Iranian or Russian suzerainty—whichever suited them best.