The voter mobilization field experiments literature suggests an automated “chatbot” on a smartphone is unlikely to increase turnout. Chatbots are a communication system where a computer interacts with people in a conversation. And interacting with a computer is, by definition, impersonal. One of the central findings in the burgeoning voter mobilization experiments literature is that impersonal contact has little-to-no effect (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019). Field experiments on mobilization via email rarely find increases in turnout (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019, 105–10; Ladini and Vezzoni Reference Ladini and Vezzoni2019; Nickerson Reference Nickerson2007; cf. Malhotra, Michelson, and Valenzuela Reference Malhotra, Michelson and Valenzuela2012). Automated pre-recorded (robo) calls do not increase turnout (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019, 87–89; Ha and Karlan Reference Ha and Karlan2009; Ramírez Reference Ramírez2005). Online advertising to mobilize voters rarely has an effect on turnout (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019, 115–17; cf. Haenschen and Jennings Reference Haenschen and Jennings2019). However, this paper reports a large field experiment wherein voter mobilization messages delivered via a chatbot significantly increased turnout. Moreover, additional previously unpublished experiments by our partner organization find the effect of chatbot mobilization is statistically significant but smaller in higher salience elections.

The paper begins by discussing how interactivity can lead people to perceive technology-mediated communication similarly to personal communication, and how this perception raises the possibility that chatbots can be utilized to increase turnout. After describing the chatbot used in this experiment, and the limitations on generalizability attendant to this chatbot and experimental population, we report on a field experiment conducted during the Wisconsin statewide election in April 2019. Prior to this 2019 experiment, our partner organization conducted voter mobilization field experiments during the higher salience 2018 general election and 2018 run-off elections. These earlier experiments are described following the results of the 2019 experiment. We conclude by discussing the implications for voter mobilization via technology-mediated communication and directions for future research.

Interactivity Can Make Technology Personal

In computer science, a “bot” (a shortening of “robot”) is any automated software that responds to incoming information or data using pre-determined rules and/or artificial intelligence to select a response. The experiment in this paper examines a simple text-based “chatbot.” Chatbots are a communication system where a computer imitates conversations using natural language when interacting with a person. The chatbot in this paper is distinct from the types of bots designed to manipulate information flows in social media that are top of mind for many political scientists and in popular and media discourse (Lazer et al. Reference Lazer, Baum, Benkler, Berinsky, Greenhill, Menczer, Metzger, Nyhan, Pennycook, Rothschild, Schudson, Sloman, Sunstein, Thorson, Watts and Zittrain2018). Chatbots are ubiquitous in e-commerce, business, education, virtual personal assistants, and other uses, with both text-based interactions (e.g., e-commerce help tools) and verbal interactions (e.g., Siri, Cortana, Bixby, and Alexa) (Ciechanowski et al. Reference Ciechanowski, Przegalinska, Magnuski and Gloor2019).

Research on human–computer interactions suggests chatbot communication may be perceived differently from other technology-mediated communication used in past voter mobilization experiments. If technological underpinnings are the important aspect of chatbots, they present little potential for mobilizing voters. Talking to a computer is, by definition, impersonal, and similar technology-mediated impersonal communication has little-to-no effect in past mobilization experiments (e.g., email, robo calls, and online advertising). On the other hand, if people perceive conversations with chatbots as similar to conversations with people, chatbots may have potential for increasing turnout. Conversations during face-to-face canvassing and chatty phone calls are the most effective forms of communication for voter mobilization (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019).

Research in human–computer interactions indicates that human-to-chatbot conversations have many of the same dynamics as human-to-human conversations. Psychophysiological and survey measures indicate people have positive reactions to interaction with chatbots, with more positive response to simple text-based chatbots than more technologically complex chatbots (Ciechanowski et al. Reference Ciechanowski, Przegalinska, Magnuski and Gloor2019). Experimental evidence also indicates human-to-chatbot conversations can produce emotional benefits similar to human-to-human conversations (Ho, Hancock, and Miner Reference Ho, Hancock and Miner2018). The positive reaction may occur because interaction with a well-executed chatbot closely resembles human-to-human text messaging (Hill, Ford, and Farreras Reference Hill, Ford and Farreras2015),Footnote 1 and text messaging is the forum for a large share of personal conversations with family and friends in contemporary society (Duggan Reference Duggan2012).

The results of voter mobilization field experiments relying on technology that is more likely to be perceived as personal are consistent with this research in human–computer interactions. Text messages have increased turnout in several field experiments, especially when the sender has a prior relationship with the recipient (i.e., “warm” text messages) (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019, 111–13). These text messages differ from a chatbot because they are one-way interventions, not an interactive conversation.Footnote 2 Voter mobilization via social media also increases turnout when messages are delivered in-stream with interactions with friends, and especially when priming people to think about social rewards or sanctions from voting (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012; Haenschen Reference Haenschen2016; Teresi and Michelson Reference Teresi and Michelson2015). The experiments reported in this paper begin to establish potential for a well-executed chatbot to mobilize voters, but additional research is needed to explore different aspects of chatbots and compare chatbots to other forms of communication.

Mobilization Mechanisms in the Chatbot Context

The experiment in this paper deploys message content with a track record of successful mobilization when used in other forms of communication. Chatbot messages could elicit a wide range of psychological mechanisms expected to increase turnout, but it is necessary to first establish whether people can be mobilized by chatbot communication. This approach is consistent with the development of research agendas on other forms of communication for voter mobilization (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019).

The treatment in the 2019 experiment uses three mobilization mechanisms: reminder about the election, information about voting, and planning to vote. First, Dale and Strauss’s (Reference Dale and Strauss2009) Noticeable Reminder Theory suggests simply letting someone know there is an upcoming election can be effective, especially when there is an existing relationship between sender and recipient – as is the case with chatbot users.

Second, prior field experiments using other forms of communication show that providing information about the process of voting can increase turnout (Arceneaux, Kousser, and Mullin Reference Arceneaux, Kousser and Mullin2012; Garcia Bedolla and Michelson Reference Garcia Bedolla and Michelson2012; Bennion and Nickerson Reference Bennion and Nickerson2016; Braconnier, Dormagen, and Pons Reference Braconnier, Dormagen and Pons2017; Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Hill2013; Herrnson, Hanmer, and Koh Reference Herrnson, Hanmer and Koh2019; Mann and Bryant Reference Mann and Bryant2019).

Third, the chatbot treatment also suggests making a plan about voting. The suggestion to make a plan to vote in the treatment lacks the detailed prompting of Nickerson and Rogers’s (Reference Nickerson and Rogers2010) plan making phone call treatment script, but may still have a positive effect on turnout. Furthermore, combining the provision of voting information with suggesting plan making should boost the impact of plan making (Anderson, Loewen, and McGregor Reference Anderson, Loewen and McGregor2018).

Chatbot for Political Engagement

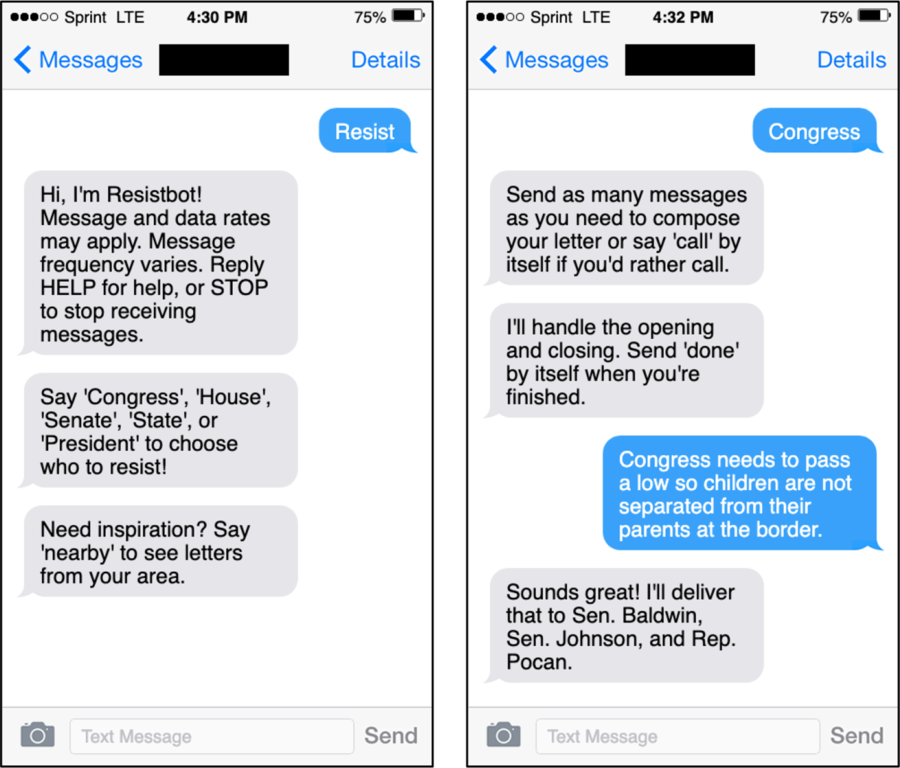

Resistbot is a chatbot that seeks to increase political engagement. Importantly for this study, its primary purpose is not voting participation. Resistbot was created to facilitate contacting elected officials by “find[ing] out who represents you in Congress or your state legislature, turn[ing] your text into an email, fax, or postal letter, and deliver[ing] it to your officials” (Resistbot 2019). Resistbot provides occasional prompts of policies about which to contact elected officials but provides no scripts, so messages to elected officials are original and unique content from citizens (i.e., not form letters). Resistbot was originally created to facilitate opposition to Trump Administration policies but delivers all messages and has extended the service to contact state-elected officials as well as federal-elected officials. The service has facilitated delivery of millions of contacts to Congressional offices and other elected officials by fax, email, and letter (Peters Reference Peters2017; Peterson Reference Peterson2017; Putorti Reference Putorti2017a).

Resistbot users join the service by sending a standard text message with the word “resist” to 50409.Footnote 3 The chatbot responds via text message with instructions on how to send messages to elected officials about policies. The interaction between user and Resistbot is a text message conversation (see examples in Figure 1). By sending a key word plus their message, users can send a message to their elected officials or engage in other actions such as sending letters to the editor to local newspapers, volunteering with political organizations, or obtaining information about voting. Thus, Resistbot users have an established record of interaction prior to and unrelated to the voter mobilization experiment.

Figure 1 Examples of Resistbot Introduction and Message to Congress.

Resistbot users primarily join after learning about Resistbot from word of mouth in social networks or from news media coverage (Putorti Reference Putorti2017b), although some civic and political organizations also promote Resistbot to their members. The Resistbot user dataset has few usable covariates because Resistbot users are not required to provide personal information beyond name and zip code. Therefore, we do not have a clear demographic profile of Resistbot users. However, the paths to joining via social networks, membership in particular organizations, and contemporary patterns of selective media exposure suggest this population is not widely generalizable. Nonetheless, it is an important test of whether interactive technology like chatbots has potential for voter mobilization.

Within the experimental population of Resistbot users in Wisconsin, 45% have used the service to contact an elected official. The remaining users signed up for Resistbot but did not send a message to an elected official, presumably due to the burdens of composing an original message about policy, inadequate feelings of efficacy, or other reasons for political inaction. Among those who have contacted an elected official, 79% have done so only once since joining Resistbot. This level of verified political activity in the experimental population in Wisconsin is higher than self-reported political activity in the general population: in the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, 24% of respondents nationally reported contacting an elected official (Shaffner et al. Reference Schaffner, Ansolabehere and Luks2019); in the 2016 American National Election Study (2019), 24% of respondents nationally reported signing a petition, and 10% reported contacting a member of Congress. Opting to join Resistbot may indicate a high level of political interest, sophistication, and civic capital, which suggests these individuals should be highly likely to vote (Leighley and Nagler Reference Leighley and Nagler2013). If so, voter mobilization will be difficult (Arceneaux and Nickerson Reference Arceneaux and Nickerson2009). On the other hand, the rates of activity on Resistbot do not seem indicative of a highly activist population. By making contacting officials much easier, Resistbot’s facilitation of communication may be attracting citizens with engagement and interest levels closer to the median, instead of activists. If Resistbot users are more typical citizens, it raises the possibility of increasing turnout with mobilization interventions.

Experimental Methodology in Wisconsin 2019 Election

We report on an experiment conducted during the April 2, 2019 Wisconsin statewide non-partisan general election for Supreme Court Justice. The race was closely contested with considerable spending by outside groups. Appellate Judge Brian Hagedorn, a conservative, won by 0.5 percentage points over liberal Appellate Chief Judge Lisa Neubauer (Marley and Beck Reference Marley and Beck2019).

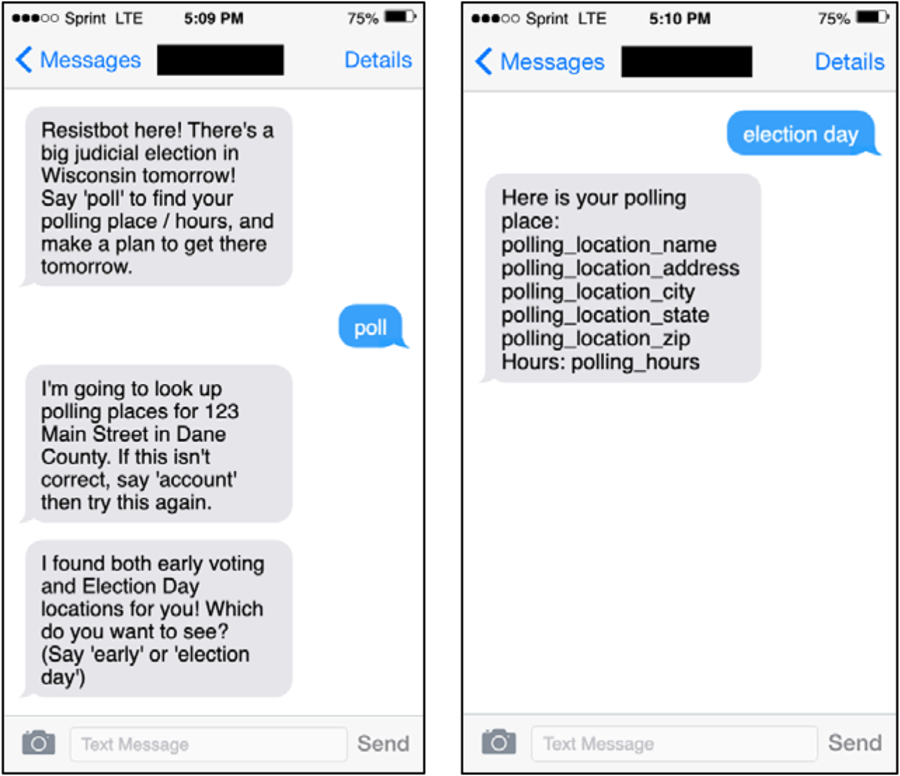

Mobilizing Resistbot users to vote is ancillary to its primary purpose of facilitating communication with elected officials. The treatment was delivered on the day before Election Day. As discussed earlier, the treatment consisted of a reminder about the election (“There’s a big judicial election in Wisconsin tomorrow!”), providing polling place location information, and a suggestion to “…make a plan to get there tomorrow” (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Resistbot (2019) Voter Mobilization Conversation.

For the 2019 experiment, Resistbot randomly assigned each of its 46,069 users in Wisconsin evenly to either the treatment group or the control group (Mann Reference Mann2020). Resistbot used a simple random assignment procedure with a computer-generated random number between 0 and 1, assigning records with values less than 0.5 to the control group and values greater than or equal to 0.5 to the treatment group. The research team was not involved in the random assignment nor development and deployment of treatment.Footnote 4 The randomly assigned groups were archived with a third party to verify data integrity. The analysis below was pre-registered with EGAP prior to obtaining the outcome data.Footnote 5

Following the election, Resistbot sent the data to Catalist LLC, a firm specializing in voter data, for matching to the Wisconsin voter registration list to obtain individual level data on voter turnout in the April 2019 election. Since Resistbot requires only a name and zip code from users, some records lack sufficient identifying information to match to the voter file with an acceptable level of match confidence. Catalist matched 72.2% of the records with a minimum match confidence of 0.67 (full score range: 0–1). The median match confidence score was 0.89 with a skew to higher scores (skewness = −0.72).

Since the research team was not involved in the random assignment procedure, a balance test using available covariates was conducted as an internal validity check. The assignment appears balanced, as expected from random assignment, based on a logistic regression of the treatment-or-control assignment on previous activity contacting elected officials (number of faxes sent, calls made, emails sent, and letters sent), region of Wisconsin (first three digits of the zip code), and successful matching by Catalist: log-likelihood ratio test = 0.184 (among matched records: 0.307). Details of balance check are in the Supplemental Materials.

RESULTS

In the control group, 22.3% of all records voted in the April 2019 election. The mobilization treatment increased turnout by 1.8 percentage points (p < 0.001; SE = 0.4). As pre-registered, Table 1, Model 1, reports the estimated treatment effect without using covariates, and the results are identical when covariates are included (Table 1, Model 2).

Table 1 Treatment Effects on Turnout in Wisconsin 2019 Election

Notes: Standard error in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; ***p < 0.01; ***p < 0.05.

Although not pre-registered, repeating the analysis among matched records produces a higher turnout rate in the control group (31.1%) and substantively similar estimate of the treatment effect (2.2 percentage points, p < 0.001, SE = 0.5; Table 1, Model 3).

Replication in 2018 Resistbot Mobilization Experiments

Prior to this 2019 experiment, Resistbot conducted two voter mobilization experiments in the 2018 general election nationwide and 2018 run-off elections in Georgia and Mississippi. These experiments were designed and analyzed by the Analyst Institute, an organization that “collaborates with progressive organizations and campaigns around the country to measure and increase the impact of their programs.” As expected, the estimated treatment effect was smaller in the higher salience 2018 general and run-off elections when it is more difficult for a treatment to produce a marginal increase in turnout.

In the 2018 general election, Resistbot tested two mobilization treatments among 1,542,909 Resistbot users across all 50 states plus DC (Putorti Reference Putorti2019; Zack, Ferguson, and Cunow Reference Zack, Ferguson and Cunow2019).Footnote 6 Resistbot users were matched to the voter file by Catalist and only registered voters were selected for this experimental population (i.e., similar to the population of matched users in Model 3 rather than Model 1 in Table 1). Turnout in the control group (n = 181,778) was 76.27%. The 2018 treatments began with a pledge to vote request in advance then reminded users to vote close to Election Day (or early voting). Soliciting vote pledges in-person and over the phone has successfully increased turnout (Costa, Schaffner, and Prevost Reference Costa, Schaffner and Prevost2018; Dale and Strauss Reference Dale and Strauss2009; Michelson, Garcia Bedolla, and McConnell Reference Michelson, Bedolla and McConnell2009), but attempting to solicit vote pledges without human-to-human interaction had not been previously tested.

In states with early in-person voting, the message stream encouraged use of early in-person voting during the appropriate period. In states where all voters receive ballots in the mail (CO, OR, and WA), the messages began 2 weeks before Election Day to encourage mailing or dropping off completed ballots. Where pre-Election Day voting was allowed, voters could opt out of Resistbot’s voter mobilization message stream by replying “voted.”

The Voting Information and Pledge treatment (n = 680,434) asked users to pledge to vote and provided information about how to vote. The Resist treatment (n = 680,697) added a frame about why to vote to the first treatment message (“The best way to resist is to vote.”). Both the Voting Information and Pledge treatment (+0.29 percentage points, p < 0.01, SE = 0.10; Table 2, Model 1) and Resist-framed treatment (+0.24 percentage points, p = 0.012, SE = 0.10; Table 2, Model 1) generated statistically significant effects relative to the control group but were statistically indistinguishable from one another.

Table 2 Treatment Effects on Turnout in 2018 Experiments by the Analyst Institute

Notes: Standard error in parentheses. ***p < 0.001; ***p < 0.01; ***p < 0.05. Results from Zack, Ferguson, and Cunow (Reference Zack, Ferguson and Cunow2019).

In the other 2018 experiment, Resistbot sought to mobilize 49,597 users in Georgia and Mississippi for the respective run-off elections after the 2018 general election. The run-off election in Georgia was much lower salience than the 2018 general election, as the highest office on the ballot was Secretary of State. The Mississippi run-off featured a contested race for US Senate but was likely lower salience than the 2018 general election. Turnout in the control group in this experiment (n = 5,838) was 36.4%. In this context, both treatments appear to have a larger effect than in the 2018 general election experiment but a smaller effect than the 2019 Wisconsin election experiment. The Voting Information and Pledge treatment generated a statistically significant increase in turnout (+1.1 percentage points, p = 0.05, SE = 0.56; n = 21,843; Table 2, Model 2). The estimated effect of the Resist-framed treatment was positive but not statistically significant (+0.5 percentage points, p = 0.4, SE = 0.56; n = 21,916; Table 2, Model 2). The Voting Information and Pledge treatment may have been more effective than the Resist-framed treatment (p = 0.08).

DISCUSSION

The voter mobilization field experiments literature suggests chatbots should be ineffective because interaction with a computer is, by definition, impersonal. However, these three experiments establish that encouragement to vote delivered via chatbot can increase turnout. Chatbot mobilization generated increases in turnout in different types of elections, with magnitude of the effect varying across election salience as expected.

While the replication across the three experiments reported in this paper bolsters confidence, more research is needed to understand the possibilities of mobilization with chatbots. Future research should compare mobilization via chatbot with other forms of communication, especially non-interactive text messages, for a better understanding of the possibilities of chatbot mobilization. Future experiments should also examine the impact of message content eliciting different psychological mechanisms, especially since the minor change in framing in 2018 run-off experiment hints at the potential for message content to matter.

Future research should examine different types of chatbots. Each of these experiments was conducted with a chatbot designed to encourage political participation, although voter mobilization is ancillary to the primary purpose of contacting elected officials. Mobilization effects may only occur among people who self-select into using political chatbots. Technical features of chatbots may also condition whether users can successfully be encouraged to vote, especially features shaping whether the chatbot interaction is perceived as similar to personal interactions. Future research could explore whether existing non-political chatbots can increase turnout: Foot-in-the-door strategies beginning with a request to use a chatbot providing non-political utility (information, entertainment, etc.) could build toward voter mobilization. Perhaps widely used virtual digital assistant chatbots like Siri, Cortana, Bixby, Alexa, and others could pro-actively encourage their users to vote on Election Day, similar to Facebook’s newsfeed voter mobilization efforts (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012).

Chatbots are so ubiquitous on smartphones, computers, and other devices in modern life that people treat them as part of their routine social context. Just as encouragement to vote from humans in our lives – whether family, friend, or campaign volunteer – can increase turnout, these experiments suggest encouragement to vote from the chatbots in our lives also has potential to influence voting behavior.

These Resistbot experiments are only a beginning to investigation of the potential for chatbots to increase voter turnout and other political activity, but the findings suggest that scholars of political communication generally and voter mobilization in particular should investigate the potential of chatbots as a path to increase political engagement.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.5