Local leaders in China are not elected but are promoted by their seniors within the Party committee at the next upper level. The exact formula for political appointment remains opaque, leading to intense scholarly debate about the factors behind the country's political selection. Most notably, the extent to which economic performance affects the selection outcomes has been hotly debated. Some empirical studies show that economic performance, measured by local economic growth, is a significant predictor of the promotion prospects of local leaders.Footnote 1 Many believe that intense interjurisdictional competition between local leaders over economic performance underpins China's long-running growth of the past three decades.Footnote 2 Daniel Bell has gone the farthest by claiming that China's performance-based cadre evaluation system is a manifestation of meritocracy that presents an alternative political model to liberal democracy.Footnote 3 On the other hand, Pierre Landry and colleagues challenge this meritocracy argument by showing that economic performance matters only to the selection of low-ranking officials.Footnote 4

In its simplest sense, meritocracy refers to a system that promotes competent individuals to powerful positions.Footnote 5 Merit can be measured through examinations and performance assessment. Many organizations choose to rely on long-term observation and training because short-term performance has more variations that may limit its ability to generate reliable signals about one's potential. In the context of the Chinese political selection, it takes decades for an official to reach the upper echelons of the party-state. Short-term performance does not necessarily have irreversible impacts on a leader's overall political career. Extant works, however, predominantly rely on short-term political turnover to gauge the effects of economic performance. In particular, they uniformly adopt the same approach: they collect the biographical data of local cadres who occupy a specific leadership position and then examine their promotion outcomes upon the completion of their leadership term. Findings based on this single-step career outcome, we argue, are unable to support or reject the performance-based argument.

A proper way to evaluate the meritocracy argument would be to examine whether competent officials are eventually promoted to important positions under the selection mechanism, not whether they can be promoted at a certain point of their political career. For this reason, we propose a new measure of political promotion to re-evaluate the meritocracy argument: the length of time until promotion. China's cadre management system vigorously enforces age restrictions on promotions.Footnote 6 The rule on eligibility stipulates that each administrative rank is associated with a certain upper age limit. Once cadres exceed that age limit, they cannot be promoted to a higher level. A key implication is that speedy promotion is a necessary condition for cadres rising to top political positions. If the system of political selection in China rewards those who spur local growth, this would entail two necessary conditions. First, there is a generally negative correlation between economic performance and the time it takes for local leaders to gain promotion. Second, the cumulative time-reduction effect of economic performance will help competent local leaders to break the age restrictions on promotion.

Applying the “time-until-promotion” measure to analyse the career development of four types of local leaders (namely, county chiefs, county Party secretaries, prefecture mayors and prefecture Party secretaries), we find little support for the meritocracy argument. In particular, even county leaders with a performance ranking consistently in the top 5 per cent would not be able to overcome the age ceiling at the level of prefecture vice-mayor (or at the administrative rank of deputy bureau director, fu ting 副厅). This indicates that the system of cadre promotion in China may fall short of the meritocratic principle considered in the extant literature, as officials judged to be competent according to their economic performance are not more likely to be promoted to leadership positions at the next upper level.

Our time-until-promotion measure allows us to not only re-evaluate the importance of the performance-based thesis but also unravel some cogent factors that affect cadre promotion. In particular, we find that the level of economic development in a territorial unit is a strong predictor of the time it takes cadres’ to gain promotion. Interestingly, its effect is moderated by administrative ranking; leaders of economically developed counties experience a significantly shorter time until they are promoted, while the time it takes for leaders of economically developed prefectures to win promotion is generally longer.

We propose a structural explanation for this curious pattern. As mentioned, cadre training plays an important role in China's political appointment system. A crucial training ground for local cadres is their regular job ranking and position, from which they gain leadership experience and the requisite skills for leadership positions at higher levels. The training value of their position, however, varies widely across territorial units owing to the difference in their administrative rank and level of economic development: low-ranking leadership positions in developed regions provide an excellent training ground for local cadres, while high-ranking leaders who occupy positions in economically important regions are expected to have sufficient experience to lead, rather than receive on-the-job training. Seen in this light, the political selection of China's local cadres is better characterized as hierarchical segmentation rather than interjurisdictional competition.

The Conventional Approach to Measuring Political Selection and its Problems

A dominant view in studies of the political selection of local officials in China holds that job performance is a crucial selection criterion. Because economic development is arguably the single most prominent national policy in the reform period, good performance often refers to the ability to generate local economic growth. In particular, all local cadres are evaluated on five aspects: moral quality (de 德); organizational ability and leadership (neng 能); industriousness (qin 勤); policy accomplishment (ji 绩); and integrity (lian 廉).Footnote 7 Economic growth is an integral part of the assessment item “policy accomplishment,” which is considered to be a top priority, or “hard target,” which local officials are obliged to fulfil.Footnote 8

This approach is especially popular among scholars of the Chinese political economy. Some argue that sub-national leaders in China are engaging in a yardstick competition over economic performance.Footnote 9 Li-An Zhou compares the cadre promotion system to tournaments in sports.Footnote 10 The performance-based argument has inspired a large number of empirical studies. Hongbin Li together with Zhou find that the promotion of provincial leaders is positively correlated with provincial GDP growth.Footnote 11 Cai Vera Zuo also shows that economic performance is positively related to the promotion of prefecture Party secretaries.Footnote 12 Zhiyue Bo finds that good economic performance decreases provincial leaders’ probability of political termination rather than increases their chance of promotion.Footnote 13 Analysing the career of prefecture-level officials, Landry finds that mayors with good performance are more likely to be promoted, while those with bad performance are not punished in the form of demotion.Footnote 14 He argues that this reward-only mechanism not only stimulates those ambitious officials but also helps to stabilize the bureaucracy.

Some dispute the effect of economic performance on the promotion prospects of provincial officials. Ran Tao and colleagues conduct similar empirical tests to those run by Li and Zhou but fail to find any significant effect.Footnote 15 Sonja Opper, Victor Nee and Stefan Brehm's study finds no evidence in support of the performance-based argument in a sample of provincial leaders.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, Pierre Landry, Xiaobo Lü and Haiyan Duan together suggest that the importance of economic performance in cadre evaluation varies according to administrative level.Footnote 17 In particular, they argue that low-ranking cadres pose limited political threats to central leaders, who would then judge the former by their performance rather than their loyalty.

We contend that the reason for the contradictory findings is related to the problems with the existing measure of political promotion. An intuitive test of the meritocracy argument is to examine the relationship between local cadres’ economic performance and their probability of gaining promotion. Extant studies uniformly adopt this approach. In particular, they often focus on a specific leadership position, such as county Party secretaries or provincial governors, and then model the political promotion of these cadres as a binary outcome; that is, either promotion or no promotion upon the completion of their leadership position terms. With this binary outcome based on a single career step, researchers then analyse factors that affect the probability of promotion. Intuitive as it is, this “single-step” approach overlooks the multiple roles that local cadres simultaneously play: in addition to serving as economic agents with a duty to accomplish tasks handed down from the central government, local cadres are also state bureaucrats.

As part of the state bureaucracy, the vast majority of these local officials’ careers are more mundane than is depicted in the literature. For one thing, the cadre management system provides formal and informal guidelines regulating the appointment, transfer, removal, promotion and retirement of cadres. For instance, since the 1980s, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has implemented the “one level down” system in which the appointment of local officials at each level is controlled by officials of the next upper level.Footnote 18 The CCP also issued the retirement rule in the mid-1980s which stipulates that male cadres at the sub-provincial levels must retire at the age of 60 (55 for female cadres).Footnote 19 Career stability is the rule rather than the exception. Like state bureaucracies in other countries, gradual advancement along the career ladder is often expected when a cadre continues to meet basic job expectations.

The bureaucratic nature of local cadres makes the single-step, dichotomous measure of political promotion unfit for testing the meritocracy argument for three reasons. First, when job promotion is the rule rather than the exception, the dichotomous measure of political promotion is at best a poor indicator of cadres’ economic performance, as many mediocre cadres will also be promoted. The potential measurement problem is compounded by the fact that the country as a whole has experienced rapid economic growth during the reform era, which is the period of analysis of most existing works. If most subnational units recorded positive growth and most subnational leaders were eventually promoted, it is not difficult to find a positive relationship between the two phenomena, even though they may be causally unrelated.

The second reason against the use of a single-step, dichotomous measure is that it ignores the time factor behind political promotion in China. As mentioned above, the CCP's cadre management system vigorously imposes age restrictions with a rule known as the “Age of Ineligibility for Promotion,” which stipulates that positions at each administrative rank must carry an upper age limit.Footnote 20 For example, if a cadre at the level of deputy minister exceeds the age of 58, then he or she would have no chance of being promoted to a higher level. But, if cadres sit the regular term of office (five years) at each point during their career trajectory, they will only reach deputy minister rank at the age of 60 at the earliest.Footnote 21 This suggests that those who make it to the top must have sidestepped the usual term of office for at least some of their prior positions. In other words, they must have been promoted at a faster rate than average cadres in order to beat the age ceiling.

With the imposition of age restrictions on promotion, career success is determined by how fast one is promoted rather than by whether one is promoted at all. Under such circumstances, using the dichotomous measure for testing the meritocracy argument is problematic. Suppose that there are two local leaders. One is ineligible for promotion owing to age, while the other still has a long way to go. If their Party senior decides not to promote either of them, they would receive the same coding under the single-step measure of promotion, but their actual career outcomes would be markedly different: the cadre who has hit the age ceiling will find his or her career has stalled, while there are still plenty of opportunities ahead for the other cadre.

The third reason, which is closely related to the second, is that meritocracy and job transfers are not mutually exclusive. In large organizations, be they in the public or private sector, it is not uncommon to have internal job transfers. In fact, many organizations utilize internal transfers as part of their on-the-job training programmes to identify and groom future leaders.Footnote 22 By gaining exposure to the work environments of different departments, an employee can develop a more comprehensive view of the organization, which may be regarded as an essential quality for a top manager. In other words, internal job transfers may well be a characteristic of a meritocratic system. When the single-step dichotomous measure is used to evaluate the meritocracy argument, however, there is an implicit assumption that under a meritocratic system, competent officials cannot experience frequent job transfers. This assumption is unrealistic in the context of China's political selection, because training by internal transfer is a key feature in China's cadre management system.

There are two short-term programmes that cadres can apply for: temporary visits (canguan fangwen 参观访问) and provisional duty transfers (guazhi duanlian 挂职锻炼). Temporary visits involve touring government and Party units in other regions. For provisional duty transfers, cadres are sent to take up a position in a different unit for a short period of time (typically one year). For example, the Sichuan provincial government in 2015 announced its intention to send 10,000 cadres from 88 poor counties to participate in provisional duty transfers in developed areas within the next five years.Footnote 23 These programmes are intended to furnish cadres with the experience necessary for making important policies related to economic reforms, balancing urban–rural development and maintaining social stability in a complex environment.Footnote 24

In addition to these short-term exchanges, it is not uncommon for sub-national cadres to “tour” different localities and departments throughout their political career. The CCP actually places a strong emphasis on leaders’ exposure to the grassroots, which can sometimes be a prerequisite for promotion. For instance, only cadres with prior work experience in more than two different positions at the level of division head (zheng chu 正处) will be considered for positions at a higher level.Footnote 25 For higher positions such as prefecture mayors, which are at the rank of bureau director (zheng ting 正厅), it is common for candidates to have held various positions at the level of deputy bureau director prior to their promotion to mayor. The state media also from time to time highlight top leaders’ ample experience at the grassroots level, perhaps with a view to emphasizing how qualified they are to represent the people despite the fact that they are not popularly elected.

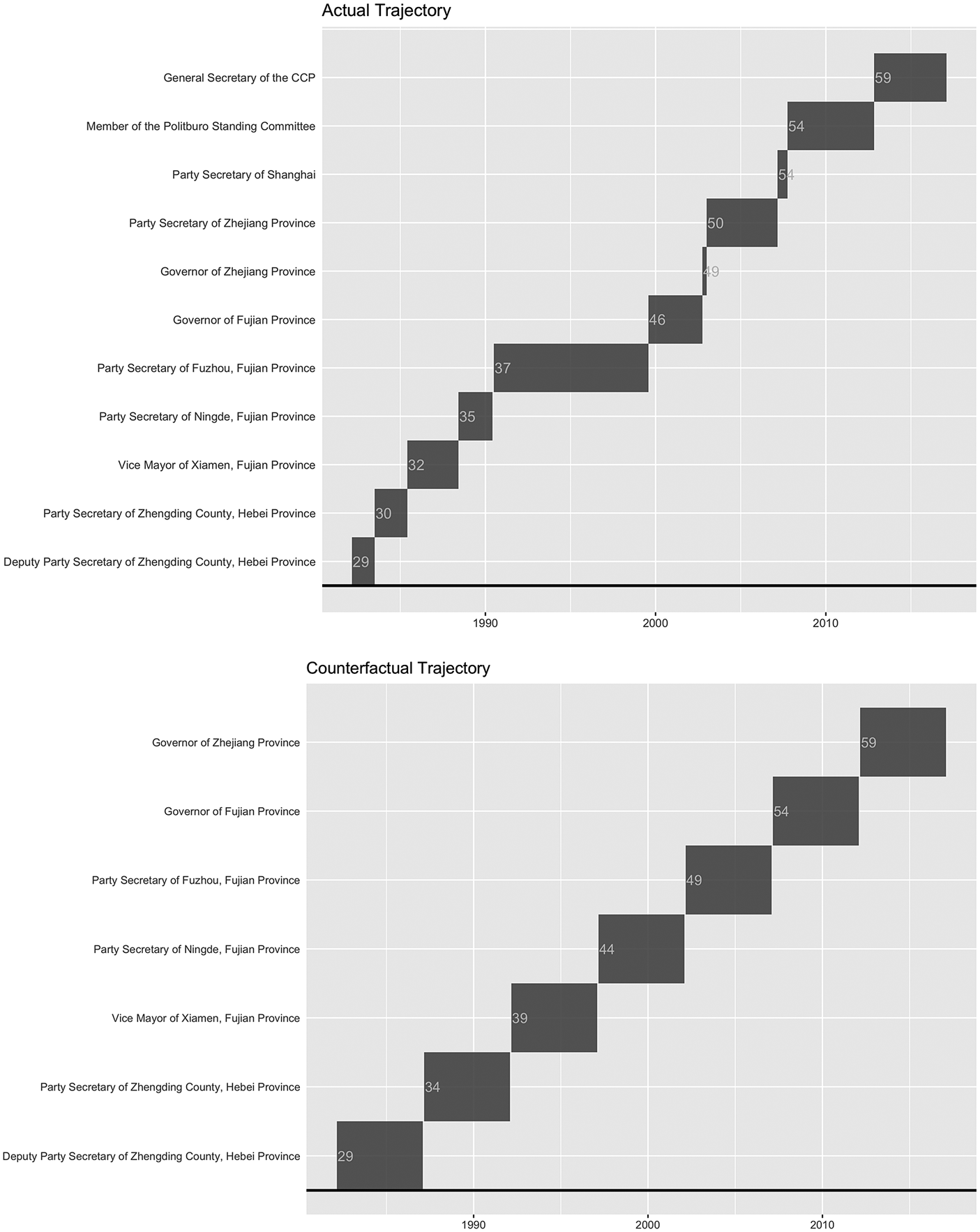

The career trajectory of Xi Jinping 习近平 is a case in point. As may be seen in the upper panel of Figure 1, Xi worked in four different provinces prior to becoming a member of the Politburo Standing Committee. Interestingly, using the single-step, dichotomous measure for political success, Governor Xi of Fujian province would be classified as a loser, because upon completion of this post, he was transferred to another position of the same administrative rank.

Figure 1: Career Trajectory of Xi Jinping: Actual vs Counterfactual

Notes:

The number shown in each bar is Xi's age when he took up the specific office.

A New Approach to Measuring Political Selection

As the ultimate winner in China's political selection race, Xi's career trajectory actually provides important insights into how to improve the existing measure of political promotion. Most notably, his political ascendancy is considered to be fairly rapid. On average, he spent only 36.7 months in each position prior to becoming the general secretary of the CCP, whereas the nominal length of tenure for each position is five years. Without such speedy promotions, Xi would not have been able to reach the highest office of the Party, owing to the age restrictions on promotion. The lower panel of Figure 1 shows a counter-factual career trajectory for Xi. Had he duly fulfilled the regular term in each office, he would have only been appointed governor of Zhejiang province at the age of 59.

Xi's example highlights the importance of the age of ineligibility for promotion in determining how far a cadre's career can go. This age restriction is arguably intended to enhance meritocratic selection. In the early 1980s, the CCP saw an urgent need to rejuvenate its senescent local cadres and so abolished the system of lifelong tenure and established the rule on mandatory retirement age.Footnote 26 To ensure that senior cadres do not occupy the same position for too long, thus impeding the upward mobility of younger cadres, the CCP has also taken steps to regulate the upper age limit for political promotion. For instance, in 2006 the Central Organization Department issued its “Opinions on further strengthening the construction of county-level Party and government chief teams” (guanyu jinyibu jiaqiang xian (shi qu qi) dangzheng zhengzhi duiwu jianshe de yijian 关于进一步加强县(市、区、旗)党政正职队伍建设的意见). The document suggests that county Party secretaries should be around 45 years of age and that talented county leaders could be identified as future prefectural leaders.Footnote 27

We take advantage of the age of ineligibility for promotion to re-evaluate the effects of economic performance on political selection in China. If economic performance plays a significant role in meritocratic selection, this would allow us to derive two distinct empirical implications. The first is that there is a generally negative relationship between economic performance and length of time until promotion. The reason is that those who are able to spur growth should be rewarded by speedy promotion. If this is not the case, the growth-promoters will eventually reach the cut-off age for promotion in the same way as other cadres, implying that their upward mobility will soon be blocked.

The second implication following on from the meritocracy argument is that the effect of economic performance on cadres’ length of time until promotion is large enough to help high performers overcome the age ceiling. In other words, even if the relationship between economic performance and length of time until promotion is negative and statistically significant, this is not sufficient to show that performance matters. Only when the effect size is sufficiently large such that it can significantly reduce cadres’ time until promotion can we confirm the claim that meritocratic selection is based on local economic performance.

Table 1 provides a concrete example to illustrate our point. The first column in the table shows a possible career path for local cadres. Suppose a local cadre managed to become a county chief at the age of 44, the median age of county chiefs in our data. Assuming that he or she is subsequently promoted to county Party secretary, the promotion is likely to occur at the age of 47.6, because the average length of tenure for county chiefs is 42.6 months. At this “young” age, the age ceiling is still a distant event. For county leaders, who belong to the administrative rank of division head (zheng chu), the age restriction for promotion is 52. Suppose that this cadre is further promoted after serving an average length of tenure in each position rank.Footnote 28 He or she will fall into the age trap during service as a prefecture vice-mayor as the cadre can only complete his or her term in office at the age of 57, which is two years beyond the age allowed for the promotion of cadres at the rank of deputy bureau director (fu ting). We call this age gap the “time deficit.”

Table 1: Typical Career Trajectories for Local Cadres

Source:

Authors’ calculation.

Notes:

The median age of county chiefs in our data is 44. “Time deficit” refers to the difference in months between the age leaving current position and the age when ineligible for promotion.

If economic performance can reduce the time it takes for local leaders to get promoted, we would then expect to see that the time earned by performing well should pay off the time deficit. How high local leaders can rise as a result of good economic performance is an empirical question that we will investigate.

Data and Operationalization

We collected the biographical data for four local leadership positions: county chiefs, county Party secretaries, prefecture mayors and prefecture Party secretaries. In China, Party secretaries are considered to be more politically powerful than government leaders of the same administrative rank, because the CCP leads the government. Party secretaries are always the first-in-command (yibashou 一把手) at all levels of governments.Footnote 29 Prefectures are the next administrative level above counties. In 2016, there were 2,851 counties and 334 prefectures. The four leadership positions are hierarchically ordered. Appendix A, which is available in the online supplementary material, provides detailed information on our data sources.

Our dependent variable of interest is the time it takes to be promoted. A job change is classified as a promotion if the cadre moves to a position of higher administrative rank in a given year. For example, the possible promotion prospects for a county Party secretary include vice-mayor of a prefecture government, member of a prefecture Party standing committee, vice-chairman of a people's congress or people's political consultative conference at the prefecture level, or head or deputy head of a provincial department. The variable “time until promotion” is measured by the number of months that a local leader occupies the position before a promotion occurs.

Descriptive statistics

We first examine the frequency of single-step promotions of the four leadership positions. To ensure comparability, we exclude right censored cases – namely, local leaders who have yet to experience any job change at the end of the period of analysis.Footnote 30 As may be seen in Figure 2, promotion in a single career step is the rule rather than the exception. Of all the leadership positions, only prefecture Party secretaries are more likely to not be promoted than promoted, although the difference between the two outcomes is statistically negligible. For other leadership positions, the rate of promotion is approximately 60 per cent. In particular, more than 70 per cent of county chiefs are eventually promoted to a higher position. The result may not be surprising, considering that these local leaders are state bureaucrats who should face less job insecurity than elected officials.Footnote 31

Figure 2: Promotion by Leadership Type

Notes:

The data include only cases where a job change was observed.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of time until a job change for these local leaders. Two points are worth noting. First, although the regular term of office for a Party secretary is five years (or 60 months), the actual length of tenure varies widely. A sizable portion of local leaders experienced a job change within three years. Second, promoted leaders generally did not stay in the office for a shorter period of time than the non-promoted ones, although the difference is far from significant. If one considers speedy promotion as a reward for demonstrated competence, the figure then indicates that the “time reward” that the promoted leaders enjoy is next to nothing.

Figure 3: Time until Job Changes by Leadership Type

Notes:

The data include only cases where a job change was observed.

We next examine the economic performance of these local officials. We focus on an economic quantity, average annual GDP growth rate, denoted by ![]() $\bar{g}$:

$\bar{g}$:

where git is the locality's growth rate under the leadership of local leader i in the year t of his or her tenure and Ti is the total number of years spent in the leadership position before a job change occurred.

Figure 4 provides a quick summary of the relationship between economic performance and time until promotion. A striking feature of these graphs is that the slopes are all positive, suggesting that competent leaders, as measured by their ability to deliver a high average growth rate, are promoted more slowly than the less competent ones. The result is clearly at odds with the meritocratic argument. It is also worth noting that there is little difference between promoted and non-promoted leaders.

Figure 4: Relationship between Time until Promotion and Average Growth Rate by Leadership Type

Notes:

The data include only cases where a job change was observed.

The figures in this section provide only a basic overview of the key variables. Many potential confounding factors are left uncontrolled for. We present more rigorous statistical analyses in the next section.

Estimation strategies

Our unit of observation is individual local leaders. Unlike previous studies, which focus on factors that contribute to the occurrence of promotion, we are more interested in finding out why the time it takes to be promoted varies widely among local leaders. For this reason, we model time until promotion, our dependent variable of interest, as a function of economic performance and other covariates at the individual or sub-national levels. We use four different estimation strategies to evaluate the impacts of economic performance on time until promotion to ensure that the results are not peculiar to a specific estimation technique. Appendix B in the online supplementary material provides a detailed description of these estimation strategies.

To reduce omitted variable bias, we control for education, ethnic minority status, gender and province of birth for local leaders (for summary statistics of all variables, see Table 2). A number of variables may also affect the time it takes for a local leader to gain promotion. The first is the age at which he or she assumes office. If the leader is approaching the cut-off age for promotion, the chances of moving up are likely to decline drastically. In addition, to capture the potential effect of factionalism, we include a variable, locally promoted superior, which assigns a value of “1” to local leaders being promoted by a locally promoted Party senior and “0” otherwise. This is based on the assumption that locally promoted bosses would have stronger local ties, which in turn influences their propensity to promote local leaders.Footnote 32

Table 2: A Summary of All Variables

Notes:

Some counties experienced redistricting. As a result, a few observations record an extremely high GDP growth rate after being merged with other counties. Average annual GDP growth is therefore winsorized by removing extreme observations at the 1st and 99th percentile.

The intensity of peer competition may matter. As Lü and Landry argue, both low and high degrees of competition may undermine local officials’ incentives to perform.Footnote 33 Following their suggestion, we model the intensity of competition with the number of counties (prefectures) within a prefecture (province). We also control for its squared term to capture any potential non-linear effects of competition. Another potentially important variable, appointed after 2012, is assigned a value of “1” for cadres appointed to the current position after 2012 and “0” otherwise. This variable aims to capture systematic variations in cadre promotion, if any, before and during the Xi era. Finally, we control for the average national GDP growth rate during a local leader's tenure in order to isolate the effect of individual economic performance from a national trend.

Empirical Results

We run two regression specifications with each estimation strategy. The first one includes only covariates at the individual level, while the second specification incorporates higher-level factors. Because the four estimation strategies involve different statistical and modelling assumptions, the effect size and the sign of the coefficients are not directly comparable. In particular, the Cox proportional hazards (CPH) models are estimating hazard ratios: a positive coefficient indicates a higher rate of observing the event (i.e. promotion).

Is economic performance negatively correlated with the time it takes to gain promotion?

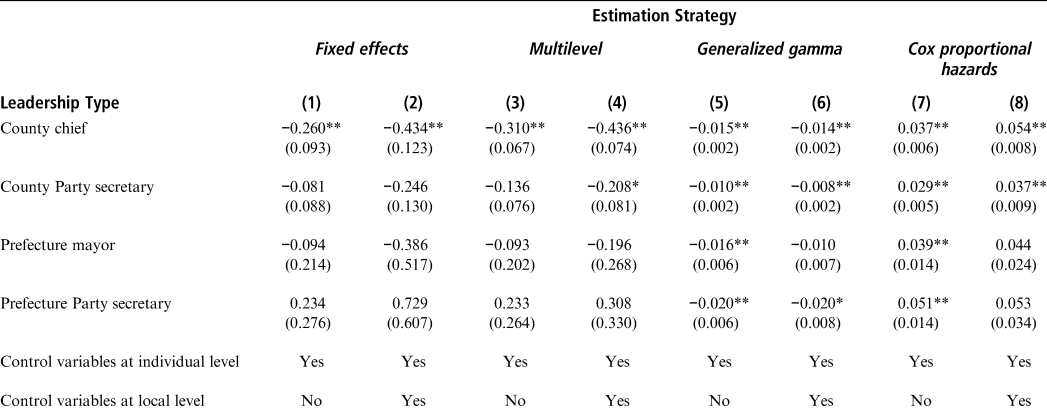

Table 3 presents the results related to the four types of local leadership positions. Note that each coefficient shown in the table is an estimate on the variable of interest, economic performance, which comes from a unique regression specification using the estimation strategy labelled in the top row on a specific leadership sample defined in the first column.

Table 3: Effects of Economic Performance on Time until Promotion

Notes:

Each estimate is a coefficient on the variable of interest “economic performance” in a unique regression specification. Economic performance refers to average annual GDP growth rate (![]() $\bar{g}$). Standard errors are in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

$\bar{g}$). Standard errors are in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

First, consider county leaders. Consistent with our expectation, the coefficients on the variable of interest are all negative in fixed effects, multilevel and generalized gamma models, suggesting that better economic performance does lead to faster promotion. The coefficients under the CPH models are positive, indicating that promotion is more likely when local cadres are able to deliver a higher average growth rate. Note, however, that the coefficients are not statistically different from zero when estimated by the fixed effects and multilevel models with the sample of county Party secretaries. The result implies that conditioned on promoted cadres, better economic performance may not accelerate the time it takes to get promoted. In the sample of county chiefs, however, the coefficients on the variable of interest are statistically significant across all specifications. Their effect sizes are also larger, providing suggestive evidence that economic performance matters more for the promotion of county chiefs than for the promotion of county Party secretaries.

As for the prefecture leaders, we are unable to find compelling evidence that economic performance is negatively correlated with the time it takes for prefecture leaders to gain promotion. In particular, for prefecture Party secretaries, the sign of the coefficient on the variable of interest is actually positive in the fixed effects and multilevel models, although the estimates are not statistically different from zero. On the other hand, while the coefficient based on the generalized gamma model is negative, indicating that economic performance is associated with faster promotion, it is not statistically significant in the full CPH specification, suggesting that the evidence is weak for the performance-based argument. In the sample of prefecture mayors, none of the coefficients on the variable of interest is statistically significant in any of the full specifications. In fact, their signs are not even consistent with some estimation strategies.

Taken together, we find stronger evidence in the county-level data to support the claim that economic performance is negatively correlated with the time it takes to be promoted. In other words, if economic performance has any effect on helping cadres avoid the age trap, the effect is more likely to manifest itself at the county level.

Can high performers overcome the age ceiling?

To answer this question, we need to first distinguish between average and high performance. We define “high performers” as local leaders who are able to achieve an average annual GDP growth rate two standard deviations above the mean, while “average performers” are simply those with an economic performance at the sample average. It is important to note that even average performers are able to deliver an average annual GDP growth rate of about 14 per cent; the rate for high performers is approximately 30 per cent. We choose two standard deviations as our benchmark for a practical reason. The ratio of prefectures to counties is approximately 1:8.5. If economic performance is the sole criterion for political selection in China, a county leader has to have a performance ranking in the 88th percentile in order to be promoted. Although the outcome of political selection may not be determined solely by economic performance alone, if a county leader managed to put him or herself in the 97th percentile (i.e. two standard deviations above the mean), he or she should stand a high chance of being promoted to the prefecture level.

How much does performance matter? Based on the generalized gamma estimates from the previous section, we compute the expected length of time until promotion for both average and high performers. The results are displayed in Figure 5. There is a distinct difference in time until promotion between average- and high-performing county chiefs: high performers are promoted approximately ten months faster than the average performers. For other positions, the difference is less striking. In fact, there is an overlap between the 95 per cent confidence intervals of average and high performers, indicating that many high performers are promoted no faster than their mediocre colleagues.

Figure 5: Expected Time until Promotion by Economic Performance and by Position

Notes:

The expected time until promotion is estimated based on the full generalized gamma models. To illustrate the effect of economic performance on time until promotion, we chose two performance levels for comparison: average and high. An average performance refers to the mean of the variable of interest (i.e. average annual GDP growth rate) across all cadres holding the same position, while a high performance refers to a performance level two standard deviations above the mean. Other covariates are set at their median value. The error bars contain 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Even if the difference in time until promotion for an individual position is unremarkable, its cumulative impact may be substantial. To compute the cumulative effect of economic performance, we compare the simulated career trajectories of average and high performers. The top panel of Figure 6 shows how far average performers can go before hitting the cut-off for promotion. The numbers used to create this simulated trajectory come from Table 1. In particular, we assume that the average performers become county chiefs at the age of 44, which is the median age for county chiefs in our data. We also assume that the time the average performers spend in each position rank is identical to the average length of tenure of the underlying position.Footnote 34

Figure 6: Simulated Career Trajectories

Notes:

The vertical dashed lines denote the ages when deemed ineligible for promotion associated with a captioned administrative rank. Unrealized career paths owing to the inability to overcome the age trap are highlighted in grey.

As may be seen from the figure, the position “prefecture vice-mayor” is probably the highest point of the political career for average performers, who would not be able to overcome the age ceiling associated with the administrative rank of fu ting (deputy bureau director). What about high performers? As may be seen from the bottom panel of Figure 6, assuming that high performers also become county chiefs at the age of 44, their career outcome is ultimately identical. Although it takes a shorter time for high performers to be promoted from the positions of county chief and county Party secretary, the time earned by delivering impressive local growth remains insufficient for overcoming the age ceiling set for fu ting cadres. The results in Figure 6 clearly indicate that the cumulative impact of economic performance at the level of county and prefecture on local leaders’ long-term political careers is fairly limited. Even if leaders are able to achieve an average annual GDP growth rate of 30 per cent throughout their time at the county level, their careers will likely stop at the position of prefecture vice-mayor. Our finding helps to explain why prefecture Party secretaries are seldom promoted from the county level in practice.Footnote 35

A caveat is in order. The findings above do not imply the impossibility of local leaders being promoted beyond the administrative rank of fu ting by relying solely on economic performance. In theory, if high flyers can consistently maintain a stellar performance even at the township level, they may then earn extra time, so that they could start as a county chief at an age earlier than 44. That extra time may in turn help them to overcome the age restriction for promotion associated with fu ting cadres. Although we are unable to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the effect of economic performance on the promotion of township leaders with the current data, it is instructive to examine how common it is for “young” county leaders to be promoted from townships. If most of them have leadership experience at the township level, we would then have reason to believe that the effect of economic performance begins to accumulate from at least township level. On the contrary, if most of them lack township leadership experience, this would imply that even if township leaders are able to reduce the time it takes to gain promotion by delivering growth, the time reduction is unlikely to carry over into the county level. As shown in Appendix C (online supplementary material), only 6.1 per cent of these county chiefs and 8.1 per cent of these county Party secretaries are promoted from township leaders. These low rates provide suggestive evidence that economic performance at the township level has limited influence over local leaders’ long-term political careers.

Structural determinants of time to promotion

Our time-until-promotion measure helps us not only to re-evaluate the importance of economic performance but also to unravel factors contributing to rapid promotion. We regress cadres’ length of time until promotion on key demographic variables and characteristics of their territorial units. The results are presented in Table 4. Two variables are consistently strong predictors of time until promotion: education and log GDP per capita. The former variable has the expected effect, as the CCP endeavours to promote highly educated cadres.Footnote 36

Table 4: Determinants of Time until Promotion

Notes:

All regression specifications are analysed with generalized gamma. The dependent variable is time until promotion. Standard errors are in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

The other significant variable, log GDP per capita, reveals more interesting patterns. For county chiefs and county Party secretaries, the coefficient on log GDP per capita is negative, while for prefecture mayors and prefecture Party secretaries, it is positive. The results imply that at the county level, economically developed territorial units are associated with rapid promotion, and the obverse is true at the prefecture level. It is worth emphasizing that the coefficients are of substantive significance – at least a great deal more significant than cadres’ economic performance. For example, consider two county chiefs. One leads a county with an average level of economic development, while another leads a county with log GDP per capita one standard deviation above the mean. All else being held constant, the latter is likely to be promoted 6.21 months sooner than the former. But for prefecture mayors, those who lead prefectures with a log GDP per capita one standard deviation above the mean would serve about seven months longer than those who lead prefectures with an average level of economic development.

The effect of log GDP per capita on time until promotion, which is both statistically and substantively important, suggests that scholars who study China's political appointments should accord attention not only to cadres’ individual characteristics (for example, economic performance) but also to structural factors such as the intensity of peer competition and administrative ranks.Footnote 37 Extant theories, however, fail to explain the mixed effects of log GDP per capita, as shown in Table 4. In particular, if log GDP per capita is a proxy measure of economic importance and if rapid promotion is desirable, we would then expect that those who head economically important territorial units are promoted faster than those who do not. In short, current theories are unable to explain the opposite signed coefficients on log GDP per capita at different administrative levels.

We propose a more nuanced explanation for the divergent time-until-promotion patterns for county and prefecture leaders. As mentioned, the CCP utilizes on-the-job cadre training to groom cadres for leadership positions. Territorial leadership positions can be mapped on a train-lead continuum, depending on two factors: administrative rank and the level of economic development. On the one hand, lower-ranking positions (i.e. county level) allow room for cadre training, while cadres who hold high-ranking positions (i.e. prefecture level) are expected to lead rather than undergo training.Footnote 38 On the other hand, developed regions are not only economically significant but also associated with a high training value. As mentioned, cadre training aims to cultivate political leaders who are able to manage economic development, which is an overarching national policy. Work experience in developed regions should be highly valued.

These two factors together contribute to the hierarchically segmented time-until-promotion patterns in the following way. Leadership positions in developed counties come with the highest training value because of their low administrative ranking and useful work experience. Turnover in these positions tends to be more frequent, and hence there is a shorter time until promotion.

By contrast, positions at higher administrative levels (i.e. prefectures) require higher leadership qualities. Those who fill these positions are expected to be experienced and skilful rather than needing further training. In the current context, the strategic importance of these high-ranking positions is further enhanced by the level of development of territorial units. As in all organizations, fewer people are qualified for high-ranking jobs than for low-ranking ones. For this reason, turnover in these positions is likely to be less frequent, and hence there is a longer lead time until promotion. Table 5 provides a summary of our argument.

Table 5: A Two-factor Model for Variations in Time until Promotion across Territorial Units

Discussion

There is a long-standing scholarly debate about whether China employs a meritocratic system to select its local officials. Local leaders’ merit is commonly judged by their ability to deliver a high GDP growth rate within their jurisdiction, as economic growth has been a top national priority during the reform era. Proponents of the meritocratic system line substantiate their argument by demonstrating that economic performance is a strong predictor of the career success of local leaders. In this article, we argue that previous studies rely on a naïve measure of career success that actually fails to test the meritocracy argument, partly because the career success of individual local cadres, who are part of China's gigantic state bureaucracy, is seldom determined by a single promotion, or the lack thereof.

We evaluate the meritocracy argument by examining whether the system is able to sort competent leaders, as defined by their ability to deliver high GDP growth within their jurisdictions, into leadership positions at higher levels. By analysing the time it takes for four types of local leaders to be promoted, we find that the cumulative effect of economic performance – namely, the time saved by performing consistently well – is fairly limited; even high performers will not be able to break the age ceiling that traps their mediocre counterparts.

Our findings shed new light on the meritocracy debate. If one follows the conventional approach to defining merit as the ability to deliver local growth, our findings clearly indicate that political selection in China is far from meritocratic, for it fails to sort local leaders with demonstrated ability to promote growth into leadership positions at a higher level. However, merit is likely a multi-dimensional concept. Showing that economic performance plays an inconsequential role in the political selection of local leaders does not necessarily imply that the system is not meritocratic; it may only signal the inadequacy of the conventional understanding of merit. As we point out in the previous section, the majority of promising young county leaders are not promoted from township leadership positions. The findings suggest that scholars of political selection should accord more attention to the selection mechanism of non-territorial leadership positions.Footnote 39 The obsession with local territorial leaders in the literature is therefore unwarranted.

Equally unwarranted is the negligence of structural factors behind political selection. Existing studies mainly deal with individual cadres’ characteristics. If the CCP does indeed try to groom future leaders, it is worth examining how its “training programme” is run. As shown in our data analysis, we find that the length of time it takes for cadres to win promotion systematically varies across administrative ranks and levels of economic development, suggesting structural differences in the training value of territorial units. In addition, given the close linkage between growth potential and the level of development, the strong correlation between time until promotion and the level of development calls into question the common assumption that economic growth within a local leader's jurisdiction can signal his or her own ability. It is plausible that cadres who are able to deliver stellar economic performances were assigned to lead fast-growing territorial units in the first place.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741020000284.

Acknowledgements

Research for this project was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number 17CZZ050). We would like to thank Lianjiang Li, Vivian Zhan, Youxin Lang and two anonymous reviewers for advice on earlier drafts of this article. We are also grateful to Li Yalan and Zhang Ruichi for their research assistance.

Conflict of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Yu ZENG is an assistant professor in the department of public administration at Southeast University, China. His research focuses on political selection, political cycles and judicial politics in China.

Stan Hok-Wui WONG is an associate professor in the department of applied social sciences at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. His research interests include political selection in China, public opinion and electoral politics.