On November 9—the day after the 2016 presidential election—headlines such as “White evangelicals voted overwhelmingly for Trump, exit polls show” in The Washington Post and “Evangelicals back Donald Trump in record numbers, despite earlier doubts” in The Wall Street Journal ran in newspapers all around the country. These articles note that just over 80% of self-identified white evangelicals—who have long been considered values voters, dedicated to bringing personal morality into the public sphere—supported the thrice-married, casino-owning candidate who frequently uses foul language, had a series of religious gaffes while campaigning, and was caught on tape denigrating women. The high level of support Trump received from white evangelicals set off a torrent of discussion among academics, religious leaders, journalists, and average Americans about who evangelicals are (Keller Reference Keller2017; Smietana Reference Smietana2017; Barna Reference Barna2018), how pollsters should classify evangelicals (Boorstein Reference Boorstein2016; Kidd Reference Kidd2016; Djupe, Burge, and Lewis Reference Djupe, Burge and Lewis2017; Fea Reference Fea2018), whether the term “evangelical” has lost its religious meaning (Merritt Reference Merritt2015; Bruinius Reference Bruinius2017; Reference Bruinius2018; Kidd Reference Kidd2016; Wehner Reference Wehner2017), and why white evangelicals supported Trump despite his shaky religious and moral footing (Prothero Reference Prothero2016; Mansfield Reference Mansfield2017; Posner Reference Posner2017; Cox Reference Cox2018; Jelen and Wald Reference Jelen, Wald, Rozell and Clyde2018). The aim of this paper is to offer some answers to these timely questions that have been extensively debated and discussed but, to date, have not be adequately addressed.

This paper proceeds as follows. The next section offers a brief overview of recent, and ongoing, debates surrounding white evangelicals' political attitudes and behaviors. Importantly, the political science, sociology, and religion literatures offer multiple ways to conceptualize and measure evangelicalism. These different strategies, in turn, give rise to the possibility that our understanding of evangelical public opinion would change with different definitions of who is and who is not an evangelical. In particular, survey results may vary when using a belief-based definition of evangelicalism, in which holding certain beliefs is the defining feature, rather than the standard self-identification question. This paper then introduces two data sources that help answer three specific questions. First, is there belief-based variation in evangelical support for Donald Trump? The data show that, among self-identified white evangelicals, holding evangelical religious beliefs is strongly associated with Trump support in the general election, even after taking partisanship and ideology into account. In contrast to claims that traditional evangelicals—those holding specific religious beliefs commonly associated with evangelicalism—would not support Trump, the data show that nominal evangelicals—those who call themselves evangelicals but do not hold beliefs commonly associated with evangelicalism—were the most likely to support Clinton or a third-party candidate. That said, the data show that Trump's successful bid to win the Republican nomination occurred, in part, due to Trump's ability to secure support of nominal evangelicals in the primary election. In other words, both nominal and traditional evangelicals helped Trump ascend to the White House.

Second, does the 2016 election represent a special case of evangelical behavior or is the election indicative of a broader trend in evangelical electoral support? Data from the 2012 presidential election suggest that, when faced with a different sort of non-traditional Republican nominee for president (in this case, a Mormon), white evangelicals looked and behaved similarly to 2016. Together, these results show that while devout evangelicals may have been uncomfortable with the last two Republican nominees, they were nonetheless staunch supporters of the Republican standard bearer in the general election.

And third, why did white evangelicals support Trump at such high rates? This paper offers negative partisanship as one explanation for the electoral results. While evangelical Republicans' levels of religiosity or faith are relatively uncorrelated with evaluations of Trump in 2016 and Romney in 2012, there is a strong negative correlation with Clinton and Obama evaluations. These findings both show that the Republican Party has benefited from devout evangelicals' negative affect toward recent Democratic candidates and also call into question claims that enthusiasm for Trump is weak among traditional or believing evangelicals, despite high levels of electoral support. All told, the empirical results offer insight into an often-discussed, but poorly understood, religious block that makes up the single largest Republican constituency.

Who are Evangelicals?

Even before the election, religious leaders, journalists, and academics were wondering about these rank and file evangelicals who appeared so enthusiastic about Donald Trump. Russell Moore, the president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention and an outspoken critic of Donald Trump, questioned whether evangelical Trump supporters were “real” or whether they were just claiming to be evangelical. After all,

At least in the Bible Belt, someone may claim to be an evangelical who's drunk right now and who hasn't been to church since someone took him to vacation Bible school back in the 1980s. And so that's not a useful category. What's useful is finding out whether or not people are actively following Christ, whether they're church attenders, for instance (quoted in Gjelten Reference Gjelten2016).

And in order to explain how Trump was winning over self-described white evangelical Christians during the primaries, Albert Mohler, the President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, responded that perhaps there are not as many evangelicals in the United States as previously assumed:

We have taken comfort in the fact that there have been millions and millions of us in America. And a part of that evidence has been the last several election cycles, with the evangelical vote being in the millions. And now we're having to face the fact that, evidently, theologically defined—defined by commitment to core evangelical values—there aren't so many millions of us as we thought.

Scholars have echoed Moore and Mohler's sentiments. Kidd (Reference Kidd2016), a religious historian, argued that “…in American pop culture parlance, ‘evangelical’ now basically means whites who consider themselves religious and who vote Republican.” According to Kidd, modern political polling has helped the term “evangelical” lose its meaning by letting survey takers decide how they affiliate religiously. In doing so, many who claim to be evangelical on a survey may not understand what the term means. Instead, “They figure ‘I'm conservative [another ill-defined term] and a Protestant, therefore I am an evangelical.’ Or maybe they think, ‘Well, I watch Fox News, so I must be an evangelical.’ Or, ‘I respect religion, and I vote Republican, so I must be an evangelical’” (Kidd Reference Kidd2016). George Marsden, professor emeritus of history and scholar of evangelicalism similarly voiced how the term “evangelical” has become muddled, particularly in survey research: “You have all sorts of people who say, ‘I guess so.’ That makes it seem that the group of evangelicals are bigger than they actually are. And it also invites all sorts of people who aren't very deeply religious to say that they are in this cultural group” (quoted in Bruinius Reference Bruinius2018).

There is social science research suggesting that these claims have merit. Evangelicals and Republicans have become closely linked in recent years (Hout and Fischer Reference Hout and Fischer2002; Patrikios Reference Patrikios2008; Putnam and Campbell Reference Putnam and Campbell2010), with some Americans now viewing the once-separate labels as a single, fused identity (Patrikios Reference Patrikios2013). Moreover, this close association that some people hold between evangelical and Republican identification can have important religious consequences. Scholars have shown that the current political environment, in which conservative Christianity and the Republican Party are tightly intertwined, has shaped Americans' levels of religiosity (Margolis Reference Margolis2018a), willingness to identify (or not) with a religion (Hout and Fischer Reference Hout and Fischer2002, Reference Hout and Fischer2014; Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Layman, Green and Sumaktoyo2018; Margolis Reference Margolis2018b), decisions to disaffiliate from church (Djupe et al. Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Sokhey2018), and choices about whether to self-identify as a born-again Christian (Egan Reference Egan2018). This growing area of research demonstrates that partisan identities, coupled with the political environment in which partisans finds themselves, can profoundly impact their involvement in, identification with, and views of the religious sphere. This raises the possibility that individuals respond “yes” to the standard survey question that asks whether they are an “evangelical” or “born-again Christian” in order to signal something about their political outlooks even if religious leaders, like Moore and Mohler, and religious scholars, like Kidd and Marsden, would not recognize these individuals as evangelicals.

A testable hypothesis from these claims emerges in which nominal or cultural evangelicals rallied around Trump while more traditional evangelicals supported another candidate. This might have occurred on account of traditional evangelicals protesting Trump's candidacy, Trump supporters adopting the evangelical label despite not holding evangelical views, or both.

If religious leaders and scholars think there are nominal evangelicals within the evangelical ranks, who exactly are, as Mohler calls them, these “theologically defined” evangelicals? Religious scholars and leaders have long emphasized that there is more to being an evangelical than simply adopting the label or belonging to a specific church. Instead, evangelicalism is about holding a specific set of beliefs, often about the Bible, Jesus, the afterlife, and the desire to spread God's word to others (Bebbington Reference Bebbington1989; Marsden Reference Marsden1991; Noll Reference Noll2001; Merritt Reference Merritt2015; Smith Reference Smith2016; Keller Reference Keller2017; Kidd Reference Kidd2016). British historian, David Bebbington, developed the most common definition of evangelicalism in his 1989 book Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s. And while there is not universal agreement on a single definition of evangelicalism, Bebbington's identification of four main characteristics of evangelicalism (biblicism, crucicentrism, conversionism, and evangelizing) is commonly cited among historians, scholars of religion, and journalists. Admittedly, certain doctrinal beliefs associated with evangelical Christianity apply to many religious denominations—both Christian and non-Christian; however, the combination of the ideas and concepts produces “something that is unique” (Fea Reference Fea2018). Using a definition meant to distinguish believing or traditional evangelicals from nominal or cultural evangelicals, according to these scholars and leaders, would change our understanding of evangelical public opinion and might show that evangelical support for Trump is less impressive than previously thought.

Fortunately, social scientists and polling firms have spent the past four decades operationalizing these overarching definitions in order to identify evangelicals on public opinion surveys. In particular, there are three broad ways that social scientists identify evangelicals in survey research. First, evangelicalism can be thought of as a group identity or identification with a social movement (Smith Reference Smith1990; Wilcox, Jelen, and Leege Reference Wilcox, Jelen, Leege, Leege and Kellstedt1993; Hackett and Lindsay Reference Hackett and Lindsay2008), and usually relies on a self-identification measure. A second way to classify evangelicals is based on their membership in a specific religious family that is generally thought to adhere to evangelical theology. This perspective emphasizes that belonging to a religious community and interacting with other community members produce a set of shared experiences and outlooks that can affect partisan loyalties and political attitudes, similar to identification with and membership in other social groups that exist in society (Wald and Smidt Reference Wald, Smidt, Leege and Kellstedt1993; Smidt, Kellstedt, and Guth Reference Smidt, Kellstedt, Guth, Smidt, Kellstedt and Guth2009; Smidt Reference Smidt2013). This strategy requires asking multiple questions about church affiliation and then classifying respondents into a religious tradition using a coding scheme that relies on denominations' official doctrines and theology (Smith Reference Smith1990; Kellstedt et al. Reference Kellstedt, Green, Guth, Smidt, Green, Guth, Smidt and Kellstedt1996; Steensland et al. Reference Steensland, Park, Regnerus, Robinson and Wilcox2000; Green Reference Green2010). Most social scientists use one of these two ways to classify evangelicals in surveys.Footnote 1

A third way of classifying evangelicals relies on adherence to a set of beliefs. Two large religious research organizations use a series of belief statements to identify evangelicals. George Barna, founder of the Barna Group, created an “elaborate set of belief affirmations” (Hackett and Lindsay Reference Hackett and Lindsay2008: 503) meant to identify evangelical Christians. The Barna Group (2016) has been using the nine-item measure for over 30 years. And in 2015, LifeWay Research, in conjunction with the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), created a four-item battery for survey researchers interested in evangelical public opinion. The logic behind measuring beliefs is simple. Evangelical Christianity is associated with specific religious beliefs and tenets. It therefore makes sense, according to proponents of this strategy, to identify evangelicals based on the beliefs a person holds rather than on what church a person goes to or whether a person adopts a particular label.Footnote 2 In fact, neither the Barna Group nor NAE/LifeWay classification schemes include measures of self-identification or denominational affiliation.Footnote 3

In addition to discussions about how best to identify evangelicals on a survey, social scientists have repeatedly argued that there are many dimensions to religion, and scholars miss important nuance when they treat members of the same religious tradition as a monolithic group.Footnote 4 For example, work by Guth et al. (Reference Guth, Kellstedt, Smidt and Green2006), Green (Reference Green2010), and Guth and Bradberry (Reference Guth, Bradberry, Box-Steffensmeier and Schier2013) show how traditionalist evangelicals—defined as evangelicals who hold certain traditional beliefs and participate frequently in their religious communities—voted for Republican presidential candidates at a much higher rate than centrist and modernist evangelicals in the 2000s. Although the exact measurement strategies differ across studies, the same picture emerges: more devout evangelicals are more steadfast supporters of the Republican Party. Green (Reference Green2010) shows that a similar relationship appears when looking at issue positions. More devout evangelicals differ from their less devout counterparts on social issues, such as abortion and gay marriage; foreign policy, in this case, support for the Iraq War; and other domestic policies, such as attitudes about health care.Footnote 5

This literature, which shows there is a lot to gain from looking at variation within religious groups, also presents an alternative hypothesis to the one previously laid out. If more traditional evangelicals have been shown to support Republican candidates and conservative policy positions over time, this should lead us to expect more of the same in 2016: more traditional evangelicals—those who hold beliefs closely tied to the core tenets of evangelicalism—should support Donald Trump in the general election at higher rates compared to their evangelical counterparts who hold fewer beliefs.

The two research areas both present plausible hypotheses about how our understanding of evangelical electoral behavior might change once public opinion scholars take beliefs—a defining feature of evangelicalism—into account. On the one hand, if Republicans adopted the evangelical label as a way to signal something about their cultural or political outlooks or if devout evangelicals protested Trump's moral failings by not supporting him, then nominal evangelicals—those holding very few beliefs commonly associated with evangelicalism—may represent Trump's main base of support. On the other hand, traditionalist evangelicals—those holding many of the beliefs commonly associated with evangelicalism—by virtue of supporting Republican candidates and conservative policies in the past, may have remained in the Republican camp in 2016 despite Trump's character issues.

A similar logic applies to the 2012 general election. There was a great deal of speculation about whether evangelicals would vote for Mitt Romney on account of his Mormon faith (Becker Reference Becker2012; Hagerty Reference Hagerty2012; Mooney Reference Mooney2012). While white evangelicals eventually stood strongly behind Romney (Pew 2012), we do not know if there is variation in support among evangelicals. It is possible that nominal evangelicals were unbothered by Romney's Mormonism, particularly if their Republican partisan identity encouraged them to identify as an evangelical, while traditionalist evangelicals could not get behind him. If this were the case, differing views of authority and compromise (Hunter Reference Hunter1991) might explain less devout evangelicals' willingness to support a candidate from a non-traditional religion while more devout evangelicals were unwilling to do so. Conversely, traditionalist evangelicals, due to their strong Republican attachments and conservative policy positions, may once again be solidly supportive of Romney despite concerns surrounding his faith.

Winning the general election is only one part of the story, however. The literature gives us little guidance about what to expect in the primary elections. While it is possible that traditionalist evangelicals supported Trump and Romney in the general election simply on account of their Republican label, both primaries were awash with potential candidates who had better “religious credentials” relative to the eventual nominees. Here, we might expect that devout evangelicals supported Trump and Romney in the primaries at a lower rate than their less devout counterparts. In other words, nominal evangelicals may have been instrumental in earning Trump and Romney the Republican nomination in back-to-back elections.Footnote 6

A final way to explore the role of beliefs among evangelicals is to test to what extent Republicans who preferred a nominee other than Trump in 2016 (Romney in 2012) rallied around Trump (Romney) once he became the candidate. It is possible that devout evangelicals came around most strongly for Trump due to the fact that they are more politically conservative than less devout evangelicals (Guth et al. Reference Guth, Kellstedt, Smidt and Green2006; Green Reference Green2010). Conversely, traditionalist evangelicals who opposed these non-traditional candidates in the primary—by virtue of the strict views of moral authority and uncompromising worldview (Hunter Reference Hunter1991)—may have been the least likely to come to support the nominees in the general election. The data, which I describe below, will help adjudicate between these possibilities.

Data

2016 SSI Study

The first data source is a large national survey of 2,000 American adults as well as an additional oversample of 500 white evangelical respondents. The sample comes from Survey Sampling International (SSI) and the survey was in the field just a few weeks before the 2016 presidential election, between October 10 and 18.Footnote 7 The survey asks respondents about their religious beliefs and practices; political attitudes, preferences, and behaviors; and politically relevant social–psychological measures. First, respondents answered an evangelical self-identification question using the same question wording as Pew and the 2016 exit poll: “Would you describe yourself as an evangelical or born-again Christian?”Footnote 8 Second, respondents answered a series of questions about their religious affiliations, including their denominations or the churches they attend. These responses then became the basis for classifying respondents as evangelical using the Steensland et al. (Reference Steensland, Park, Regnerus, Robinson and Wilcox2000) coding scheme. And third, respondents reported their levels of agreement with seven statements that are similar, but not identical, to the Barna Group's classification scheme of evangelicals. These statements measure respondents' views about: the Bible; sharing religious beliefs with others, otherwise known as evangelizing; how one achieves eternal salvation; whether Jesus Christ committed sins during his life, the importance of religious faith in daily life, whether the Devil is real or a symbol of evil, and belief in God. The full question wordings are available in Appendix A.Footnote 9

The analyses that follow rely on an additive belief scale based on how many of beliefs respondents accept (either somewhat or strongly). Individuals can therefore have a belief score ranging from 0 (agree or agree strongly with none of the statements) to 7 (agree or agree strongly with all of the statements). This strategy, which allows me to look at variation in beliefs among those who call themselves evangelicals, differs from the Barna Group's classification strategy which identifies evangelicals as those who strongly adhere to all the beliefs.

Operationalizing belief as an ordered scale rather than an all-or-nothing classification has both theoretical and empirical justifications. From a theoretical standpoint, the goal of this paper is not to claim that the Barna Group's classification scheme is how scholars should identify evangelical Christians in surveys. It is easy to debate whether the Barna Group asks all the necessary and sufficient questions needed to identify an evangelical. Moreover, it is certainly the case that some of the Barna Group's measurement strategies—such as agreeing with the statement that faith is an important part of one's life and agreeing that God exists—are not unique to evangelical Christians and are statements with which many nominal evangelicals agree. Instead, the goal of the analyses is to look at how holding a greater number of or fewer beliefs corresponds to different political outlooks.Footnote 10 From an empirical standpoint, an additive scale offers additional information that a closed classification scheme cannot. An additive scale, for example, can show whether increasing the number of beliefs corresponds to linear changes in political attitudes or whether there are thresholds above or below which self-identified evangelicals hold similar political views. And by having a diverse set of beliefs—some of which are overwhelmingly accepted by evangelicals and non-evangelicals alike while others are more specific to evangelical theology—it is possible to uncover previously unknown political trends within this large bloc of American voters.

A detailed analysis and discussion validating the additive scale is available in Appendix A. The section asks and answers a series of questions about the data and shows that: white self-identified evangelicals hold religious beliefs associated with the Barna Group's conception of evangelicals; non-white evangelicals look similar to white evangelicals in the number of average beliefs; white non-evangelicals, who are nonetheless Christian, do not hold many of the religious beliefs asked by the Barna Group to identify evangelicals; self-identification and denominational measures of evangelicals yield similar distributions of religious beliefs; Republican evangelicals hold, on average, a greater number of religious beliefs than Democratic evangelicals; and the religious belief scale correlates with other measures of religiosity in expected ways.

2012 Barna OmniPoll

The second data source is a nationally representative survey of 1,021 American adults. The Barna Group commissioned Knowledge Networks to run the study between February 10 and 18, 2012.Footnote 11 The survey does not ask the Pew version of the evangelical self-identification question and instead asks whether respondents have “ever made a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in your life today?” Respondents also answered a question aimed at measuring denominational affiliation as well as a series of questions tapping into religious beliefs. While the Barna question wording differs slightly from the SSI survey wording, the religious belief questions measure the same general beliefs and ask about the same topics as the SSI survey. There is one additional question, which asks respondents what they believe happens after they die, that is part of the battery that Barna uses to identify evangelicals but did not appear in the SSI survey. The exact wording for all the question is available in Appendix A. Just as in the SSI survey, the individual items can form an additive scale of religious beliefs, ranging from 0 (holds none of the beliefs) to 8 (holds all of the beliefs).Footnote 12 The survey—which took place at the beginning of the 2012 Republican presidential primary season—also measures political preferences, including electoral support and evaluations of politicians.

The next section explores how variation in beliefs among white evangelicals corresponds to electoral support.

Evangelicals Supported Trump in the General Election

Undergirding, sometimes implicitly and other times explicitly, critiques about evangelical measurement lies the claim that traditional or believing evangelicals would not support Trump. According to this narrative, it is the nominal, cultural, or political evangelicals who overwhelmingly supported Trump and produced the 80% statistic in exit polls that has gripped the attention of so many. On its face, this assertion is plausible. After all, many self-identified evangelicals do not hold all the beliefs commonly associated with evangelicalism meaning that there are enough nominal evangelicals within the evangelical subsample to skew the survey results. And recent research highlights that individuals may think or act religiously as they are politically. The data should be able to show if nominal evangelicals—those who do not hold many of the religious beliefs—represent Trump's main base of support.

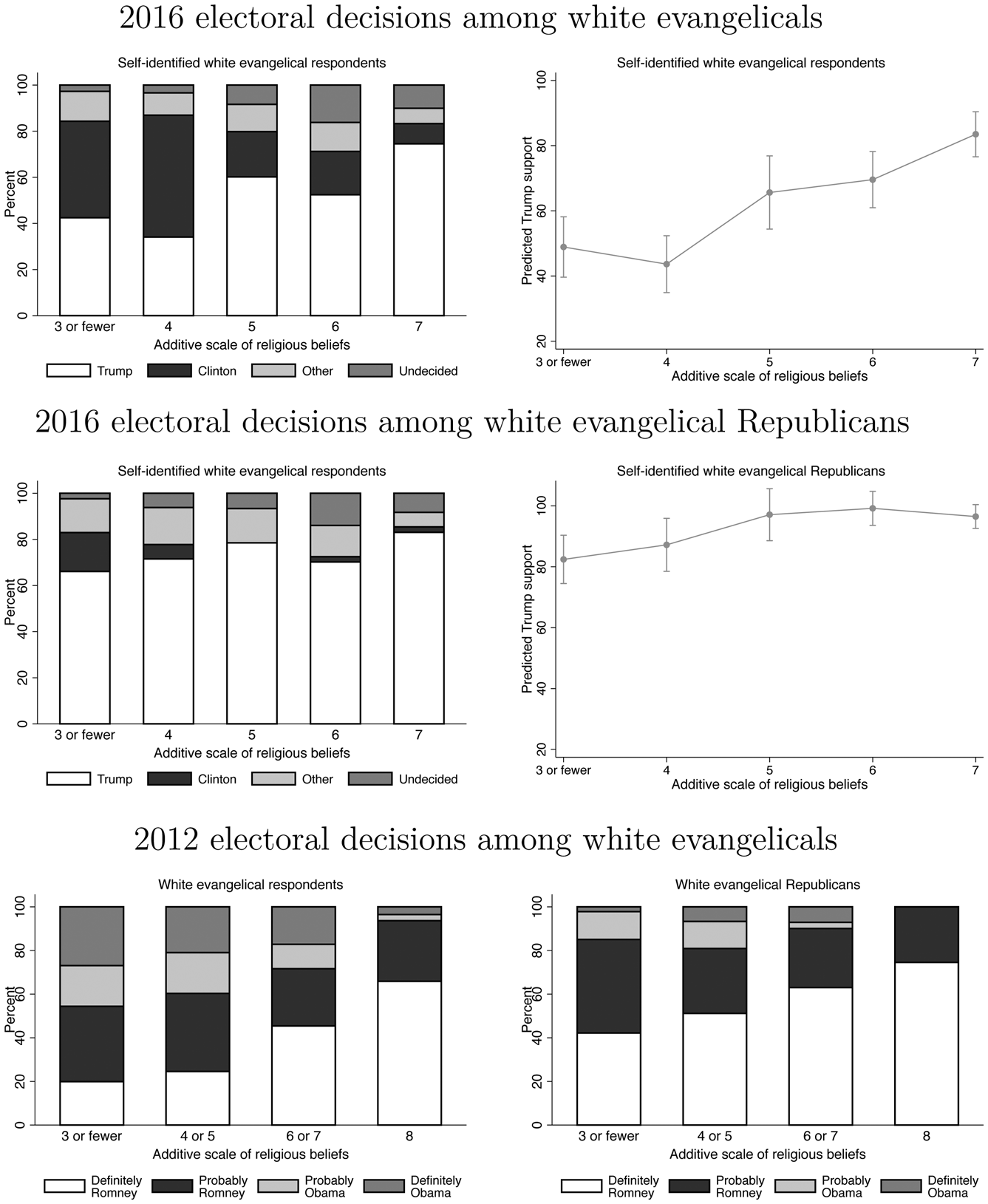

Figure 1 presents four panels testing this possibility. The top-left panel shows white self-identified evangelicals' weighted responses to a question asking who they planned to vote for in the upcoming election, separated out by how many beliefs they held. The least religious category includes those white evangelicals holding zero, one, two, or three evangelical beliefs to account for the small number of evangelicals who hold so few beliefs.Footnote 13 The white boxes with black outlines represent the percentage of respondents who report that they plan on voting for Donald Trump. Support for Donald Trump increases alongside holding a greater number of religious beliefs. The black boxes represent the percentage of respondents who report that they plan on voting for Hillary Clinton. Here, the trend reverses itself: the share of Clinton support decreases among evangelicals as the number of religious beliefs held increases. Evangelicals holding a greater number of beliefs, therefore, are more likely to vote for Trump and less likely to vote for Clinton relative to their more nominal counterparts. The top two boxes in the bar chart represent support for a third party candidate (light gray) and undecided voters (dark gray). The third party candidates include Jill Stein of the Green Party and Gary Johnson of the Libertarian Party.Footnote 14 While support for third-party candidates was generally small, ranging between 7 and 13%, rates of third-party support were actually slightly higher among those holding fewer evangelical beliefs. Looking at the white evangelical population as a whole, therefore, there is no evidence that more traditionalist evangelicals were more likely to abandon Trump in favor of a third-party candidate. That said, there is some evidence that evangelicals holding a greater number of beliefs were more likely to report being undecided just a few weeks out from the election. For example, just 3% of evangelicals holding three beliefs or fewer were undecided, whereas 16% of evangelicals holding six beliefs and 10% of evangelicals holding all seven beliefs reported being uncertain about their upcoming vote choice. While there are numerous reasons why a person could be uncertain about his or her vote choice—deciding between Trump and Clinton, deciding between Trump and a third-party candidate, deciding about whether to vote at all, and deciding whether to share his or her decision with a survey researcher—these raw data offer some suggestive evidence that perhaps evangelicals holding a greater number of religious beliefs were conflicted in the lead up to the election. The top-right panel of Figure 1 shows the predicted electoral support for Trump versus Clinton based on the number of religious beliefs held after taking other demographic, socio-economic, and religious variables into account. Support increases steadily, with evangelicals holding all seven of the religious beliefs in the survey showing the highest rates of Trump support.

Figure 1. Religious beliefs correlate with electoral decisions.

The first set of analyses exclude political variables in order to show basic relationships in the data, but we know that partisanship is the strongest predictor of vote choice (Lewis-Beck et al. Reference Lewis-Beck, Norpoth, Jacoby and Weisberg2008), evangelicals are disproportionately Republican, and evangelical Republicans hold a greater number of beliefs on average than evangelical Democrats.Footnote 15 The political composition of evangelicals, therefore, might explain the first set of results. The middle panels of Figure 1 present replicated analyses for white self-identified evangelical respondents who also identify as Republicans. A smaller, but still sizable, increase in Trump support emerges when looking at the Republican subsample. Whereas 66% of white evangelical Republicans holding three beliefs or fewer—those who we might safely categorize as cultural or nominal evangelicals—reported that they would vote for Trump, 83% of those holding all seven beliefs did so. The middle-right panel presents the predicted levels of support for Trump versus Clinton among Republicans after taking socio-demographic traits, other religious behaviors, and political ideology into account. These results show that, even after accounting for other correlates of vote choice, Trump support is lower among evangelical Republicans holding four beliefs or fewer and that two-party support caps out among evangelicals holding five, six, or seven beliefs. The results, presented in full in Table B2 in the Appendix, show that the gap between evangelical Republicans holding a greater number of beliefs and a fewer number of beliefs is statistically significant.Footnote 16

These data contribute to our understanding about evangelicals' role in the 2016 election in two ways. First, these results go against the narrative that believing or real evangelicals would not support Trump. When looking at beliefs, which represent the core underpinnings of evangelicalism and the (proposed) measurement strategy of religious (scholars) research firms, there is a strong relationship between religiosity and Trump support even after controlling for partisan identification and ideology and in analyses that look at Republican identifiers only. Instead of finding evidence that real evangelicals—based on their beliefs—disassociated themselves from Trump, the results trend in the other direction: a deeper commitment and more adherence to the beliefs is associated with more support for Trump in the general election. As such, these data do not suggest that many non-religious Republicans or Trump supporters adopted the evangelical label for political purposes, rather they corroborate work showing that traditionalist evangelicals are stronger Republican supporters than their less devout counterparts. And second, these findings build on previous empirical results showing that evangelical support for Trump existed among both frequent and less frequent church attenders (Grant Reference Grant2016; Newport Reference Newport2016; Djupe, Burge, and Lewis Reference Djupe, Burge and Lewis2017). While church attendance is uncorrelated with Trump support among evangelicals—a result the SSI data show as well—it would be a mistake to infer religiosity had no association with white evangelicals' political decision making in the 2016 election.Footnote 17

The next step is to see whether this relationship between beliefs and support for Trump is generalizable beyond 2016. If these findings are specific to the 2016 election, then scholars have more work to do when it comes to explaining why evangelicals were so drawn to Trump, or so opposed to Clinton. But it may also be the case that religious evangelicals represent an extremely loyal Republican constituency in the face of non-traditional candidates of various stripes. Data from the 2012 presidential election indicate that the answer is the latter. I use data collected by the Barna Group before the 2012 presidential campaign season got underway to replicate the previous findings. These results, presented in the bottom panels of Figure 1, rely on a question that asks respondents to state their preference in a hypothetical race between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. While this turned out to be the choice on offer in the 2012 election, the Republican nominee had not yet been selected when respondents answered the question. Here, the response options were: definitely Romney, probably Romney, probably Obama, and definitely Obama. The raw results for the full sample of white evangelicals (left-bottom panel) show a similar pattern to the 2016 results. For these analyses, I collapsed the religious belief categories to ensure there are enough respondents within each category; however, the trends are similar when using the full belief scale. As the number of beliefs held increases, rates of “definite” and “probable” support for Romney increase and rates of “probable” and “definite” support for Obama decrease. And once again, these results do not appear due to partisan differences among evangelicals of varying levels of belief. A similar trend appears among evangelical Republicans in which 100% holding all eight Barna beliefs reported that they would vote for Romney compared to 80% of evangelical Republicans holding three beliefs or fewer (bottom-right panel). These trends hold in models that control for socio-demographic predictors associated with political and religious attitudes (results available in Appendix C).Footnote 18

Taken together, these analyses illustrate that devout evangelicals, those holding a greater number of religious beliefs, were not just more likely to support Trump in 2016 but appear to represent a steadfast bloc of support in the face of non-traditional Republican candidates. In stark contrast to the claims that evangelicals who hold traditional evangelical beliefs would not support Trump, traditionalist evangelicals represent Trump's most loyal supporters, and this support goes above and beyond what partisanship would predict. While these results tell us something important about the general election, the next section explores what happens when partisans have multiple co-partisans from which to choose.

Primary Support and Rallying Around the Candidate

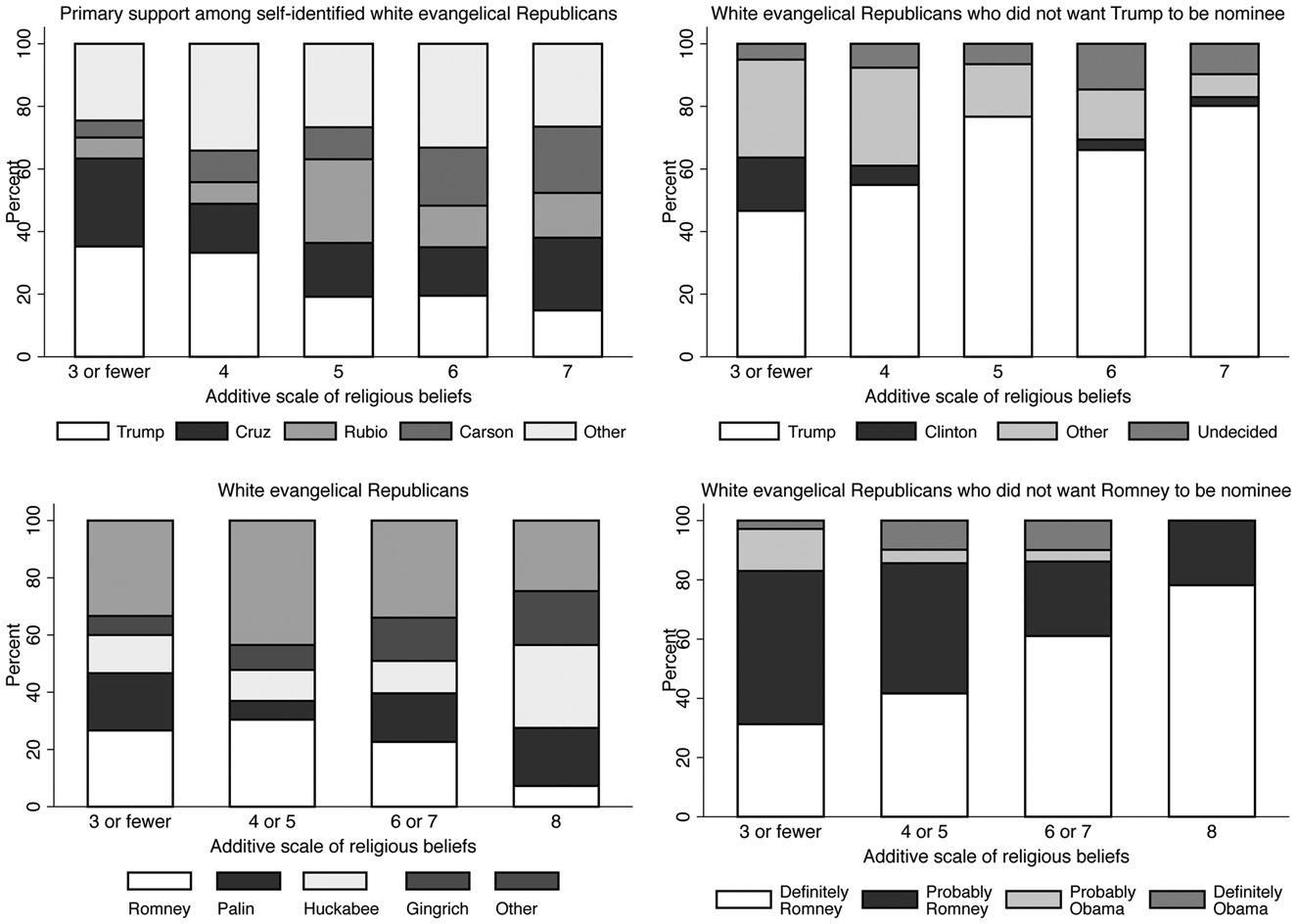

Did real evangelicals want Trump to be the nominee? The 2016 SSI survey asked Republican respondents about their preferred Republican nominee for president. Unlike the previous results, holding a greater number of religious beliefs is correlated with less support for Trump in the primary. The top-left panel of Figure 2 presents the distribution of primary support among self-identified white evangelical Republicans. Trump's support at the primary stage decreases as the number of beliefs held increases. Thirty-four percent of white evangelical Republicans holding three beliefs or fewer and 38% of white evangelicals holding four beliefs reported wanting Trump to be the nominee. In contrast, only 18 and 14% of white evangelical Republicans holding six and seven beliefs, respectively, reported wanting Trump to be the nominee. This is the first piece of evidence in support of the claim that less devout evangelicals were crucial to Trump's victory. These results comport with others who have shown that Trump was not the first choice of religious evangelicals—usually defined by church attendance (Douthat Reference Douthat2016; Guerra Reference Guerra2016; Miller Reference Miller2016)—and offers credence to the critiques that evangelical support of Trump during the primaries was overblown.Footnote 19 Importantly, however, primary support for Trump was slightly lower among nominal evangelicals—those holding three beliefs or fewer—than white non-evangelical Republicans (34 versus 42%). Table B4 shows that the raw trends remain in models that include control for demographics and outlooks that may correlate with holding religious beliefs and primary support.

Figure 2. Religious beliefs correlate with primary support and rallying around the nominee.

How did white evangelical Republicans who preferred that someone other than Trump become the nominee behave in the general election? Trump may have faced an electoral problem if devout evangelical Republicans who preferred another nominee decided to stay home or vote against Trump. But, among those who did not want Trump to be the nominee, it was the more devout evangelicals who rallied most strongly around the Republican candidate. The top-right panel of Figure 2 shows raw levels of reported support for Trump in the general election among evangelical Republicans who wanted someone other than Trump to be the nominee. While it is important to interpret the results at the bottom end of the scale with caution as they have relatively small sample sizes, collapsing the bins so that the categories are four or fewer, five or six, and seven produces the same trends. And once again, Table B6 shows that the gaps remain in models that include control variables.Footnote 20

The bottom panels of Figure 2 return to the 2012 poll conducted by the Barna Group. The bottom-left panel presents the distribution of primary preferences among white evangelical Republicans, separated by the number of beliefs held. Similar to the 2016 results, there is not unified evangelical support around Romney to become the nominee, and support for Romney was particularly low—less than 10%—among those who the Barna Group would classify evangelicals (holding all eight beliefs). These results comport with journalistic accounts of evangelicals being uncomfortable with Mitt Romney's Mormonism, especially early in the primary season (Goodstein Reference Goodstein2012; Reynolds Reference Reynolds2012). Despite this initial skepticism, evangelicals—particularly evangelicals holding most or all of the religious beliefs that make up the Barna Group's classification scheme—overwhelmingly supported Romney in a mock election against Obama (bottom-right panel). In fact, 100% of evangelicals holding all eight beliefs reported that they would vote for Romney, either definitely (approximately 80%) or probably (approximately 20%). In contrast, roughly 18% of those we might consider to be nominal evangelicals—those holding three beliefs or fewer—reported that they would vote for Obama in the general election despite these respondents both identifying as evangelicals and Republicans.Footnote 21 By way of comparison, 22% of white Republicans who do not identify as evangelicals and preferred a different Republican nominee reported that they would vote for Obama (either “definitely” or “probably”) in the hypothetical election. Once again, nominal evangelicals—those holding three beliefs or fewer—look similar to their non-evangelical Republican counterparts when it comes to supporting a Republican candidate who was not their first choice. More devout evangelicals, on the other hand, coalesced around Romney. These results are robust to the inclusion of demographic and religious control variables (presented in Appendix C).

Three consistent trends emerge when looking at the Republican primary process. First, identifying as an evangelical in general, and holding evangelical beliefs in particular, is correlated with wanting more traditionally “religious” candidates. Neither Donald Trump nor Mitt Romney are candidates whose superficial profiles would make them obvious candidates for evangelical support, and this becomes evident in competitions in which there are religious alternatives. In 2016, devout evangelicals reported wanting Ted Cruz, Ben Carson, or Marco Rubio, while a plurality of devout evangelicals in 2012 reported wanting Mike Huckabee—the Baptist minister—to be the nominee, with some evangelicals supporting Sarah Palin and Newt Gingrich as well. Second, white evangelical Republicans who hold a greater number of evangelical beliefs are more likely to rally around their party's nominee than evangelicals who hold fewer beliefs or non-evangelicals. And third, this result is not merely a phenomenon from 2016. Finding similar results using the 2012 Omni Poll indicates that these traditionalist evangelicals can be counted on to support the Republican Party regardless of how the primaries play out.

Having shown that incorporating religious beliefs adds nuance to our understanding of evangelical electoral support, the next section pivots to explore one explanation for why this relationship exists.

Why Did White Evangelicals Support Trump?

Trump's large base of support from white evangelicals produced many headlines, leading many to wonder how religious Christians could endorse Trump's personal behaviors by voting for him. On the one hand, the explanation is incredibly straightforward: about 90% of white evangelical Republicans voted for Trump and this is roughly the same percentage of non-evangelical Republicans who voted for Trump. In other words, Republicans voted for the Republican candidate. Jelen and Wald (Reference Jelen, Wald, Rozell and Clyde2018) make this point when writing about evangelicals in the 2016 election; partisanship is a strong social identity that is closely tied to evangelicalism, another strongly held identity. As such, it should be wholly unsurprising that white evangelicals supported Trump in the presidential election. This partisan explanation, which satisfactorily describes evangelical support for Trump at the aggregate level, ignores the discussions and critiques surrounding how scholars, pollsters, and journalists measure, classify, and identify evangelicals. Additionally, the partisanship-is-powerful account alone cannot explain why devout evangelical Republicans are more supportive of Republican candidates than Republicans holding fewer religious beliefs or Republicans who do not identify as evangelical.

To better understand why—even among Republicans—it was the most religious evangelicals who were also the most supportive of Trump's candidacy, I test whether negative partisanship and affective polarization explains white evangelicals' continued support for non-traditional or controversial Republican candidates. The affective polarization explanation—in which partisans have come to increasingly dislike and distrust members of the opposing party (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016)—hinges on the idea that, for example, evangelicals may not like Trump but they voted for him because Hillary Clinton, was an unpalatable alternative. This justification of support is far from a ringing endorsement of Trump. Instead, we could interpret it as a begrudging acceptance in the face of a terrible alternative. This explanation builds on the earlier findings that traditionalist evangelical Republicans were more likely than nominal evangelical Republicans and non-evangelical Republicans to support both Trump and Romney. These religious evangelicals may have disliked certain aspects of the candidates' personal profiles, but voted for them anyway because they felt like they had no choice.Footnote 22

The left panel of Figure 3 presents the relationship between number of religious beliefs held and favorability ratings of Donald Trump (black circles) and Hillary Clinton (gray squares). The black circles and solid confidence intervals represent the average predicted feeling thermometer scores, which range between 0 and 100, for Trump as a function of beliefs held, controlling for socio-demographic characteristics. Traditionalist evangelicals—those holding all seven beliefs—give an average feeling thermometer score that is about 8 points higher than evangelicals holding three or fewer (p-value < 0.05). The black open circles and dashed confidence intervals represent the results from a similar model using the Republican subsample. In this case, traditionalist evangelical Republicans held slightly more negative evaluations of Trump than evangelicals holding three beliefs or fewer; however, this gap is not statistically significant at conventional levels (difference = −7; p-value = 0.12). Among both the full and Republican subsample, there appears to be a relatively weak correlation between number of beliefs held and evaluations of Donald Trump in 2016.

Figure 3. Religious beliefs correlate with out-party evaluations.

The solid gray squares with dashed confidence intervals and open gray squares with dotted confidence intervals present the same relationships, but using Clinton feeling thermometer scores. Looking first at the solid gray squares, which represent predicted feeling thermometer scores in models that include all evangelicals, an increase in the number of beliefs held corresponds to a sharp drop in evaluations. Whereas individuals who hold three or fewer or four beliefs have an average feeling thermometer score of 48 and 53, respectively, the average feeling thermometer score for Clinton is only 20 among the most devout evangelicals (difference between most and least devout = −28; p-value < 0.01). The open gray squares replicate the results among Republican identifiers. Here, the starting point among nominal evangelicals is unsurprisingly lower than the full sample (33 and 29 for the first two groupings); however, the steep decline remains as the number of religious beliefs increases. The average feeling thermometer score is about 12 among those at the most devout end of the spectrum (difference between most and least devout = −21; p-value < 0.01).

The weak relationship between beliefs and feelings toward Trump contradicts an important claim that white evangelicals will “hold their noses” and vote for Trump (David Brody, national correspondent for the Christian Broadcasting Network, quoted in Johnson Reference Johnson2016).Footnote 23 If this were the case, we would expect devout evangelicals to register their dissatisfaction with Trump despite their plan to vote for him. Instead, we see relative stability in evaluations across the board. Conversely, devout individuals may have been driven to support Trump, in part, due to their extreme dislike of Clinton. Even among the Republican subsample and in models that include control variables, a persistent evaluation gap emerges in which more devout evangelicals view Clinton more negatively than their more nominal counterparts. Negative partisanship may have kept traditionalist evangelicals steadfastly in the Republican camp.Footnote 24

Once again, replicating these analyses during a different election offers necessary context for the 2016 results. Perhaps religious beliefs are strongly and positively associated with evaluations of a different non-traditional Republican candidate. If this were the case, the weak results previously described may actually indicate a tepid reaction to Trump among devout evangelicals as their evaluations of the Republican presidential candidate was lower in the 2016 election than in 2012. Similarly, it is possible that the negative evaluations of Clinton were specific to Clinton and do not generalize to other Democratic candidates. The right panel replicates the evaluation results using the 2012 Barna Group Omni Poll. Here, the dependent variable is a four-point favorability rating of Mitt Romney (black circles) and Barack Obama (gray boxes) that ranges between 0 (very unfavorable) and 100 (very favorable). Once again, there is relative stability in evaluations of Romney based on religious beliefs; however, beliefs have a strong correlation with evaluations of Obama, both in the full evangelical sample (solid gray boxes) and the Republican subsample (open gray boxes).Footnote 25 Despite including demographic controls in both models and looking specifically at Republicans in the latter model, a large evaluation gap between more and less devout evangelical persists.

These results show us that the 2016 evaluation findings seem to be part of a broader trend rather than unique to the 2016 election. In both the 2012 and 2016 elections, evangelical Republicans held similar views of their own party's candidates, regardless of their levels of beliefs, while evaluations of the Democratic Party's candidates declined precipitously as the number of beliefs held increased. These results highlight that negative partisanship—feelings of dislike toward the political out-party and its candidates—exists in spades among white evangelical Republicans and may help explain Republican candidates' high levels of support among this group.

These findings, which add important insight into why devout evangelicals may support non-traditional Republican candidates, contribute to a large body of research exploring the determinants of Trump's electoral appeal. Attitudes about gender roles, sexism, and race (Van Assche and Pettigrew Reference Van Assche and Pettigrew2016; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018; Valentino, Wayne, and Oceno Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018); views about social structures, hierarchy, and obedience (Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene, Federico and Millerforthcoming; MacWilliams Reference MacWilliams2016; Van Assche and Pettigrew Reference Van Assche and Pettigrew2016; Choma and Hanoch Reference Choma and Hanoch2017); feelings of political efficacy (Hetherington Reference Hetherington2015; Friedman Reference Friedman2016); populist attitudes (Groshek and Koc-Michalska Reference Groshek and Koc-Michalska2017; Norris and Inglehart forthcoming; Tesler Reference Tesler2016); and holding Christian Nationalist beliefs (Whitehead, Perry, Baker Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018) have all been shown to be important determinants of the 2016 vote. These findings show that negative partisanship, which has been repeatedly documented in the general public (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2017), also plays a particularly important role in understanding evangelical public opinion: more devout evangelicals, even after taking partisanship and ideology into account, are more likely to hold negative evaluations of out-party candidates relative to their less devout counterparts. One implication of these results is that evangelical Republicans are unlikely to ever abandon the Republican candidate, as their dislike for Democratic candidates—and possibly the party as a whole—keeps them squarely in the Republican camp.

Conclusion

Evangelical Christians represent an important political bloc and have received extensive attention from politicians, the media, and academics. Some thought that the 2016 election, with the unlikely Republican nominee, would change the electoral landscape with evangelical Christians taking a stand against Donald Trump by abstaining, voting for a third-party candidate, or even crossing party lines to vote for Hillary Clinton. But none of those things happened, and Trump continues to enjoy high levels of approval among white evangelical Christians despite low rates of support overall (Burton Reference Burton2018a; Reference Burton2018b). This paper explores variation in evangelical electoral support and public opinion with the purpose of understanding what explains white evangelical support for Donald Trump.

The empirical results show that more devout or traditionalist evangelicals were more likely to support Trump in the general election compared to less devout evangelicals. These findings both help to adjudicate between conflicting expectations and add to the body of knowledge about evangelicals' role in elections. While there is a growing body of research showing that political affinities can shape reported religious identities (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Layman, Green and Sumaktoyo2018; Djupe et al. Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Sokhey2018; Margolis Reference Margolis2018a; Reference Margolis2018b) and a chorus of critiques that evangelical support for Trump came largely from nominal or non-believing self-identified evangelicals (Gjetlen 2016; Kidd Reference Kidd2016; Bruinius Reference Bruinius2018), the data do not show evidence of this. Instead, the evidence corroborates work showing that traditionalist evangelicals are more loyal to the Republican Party relative to more centrist or nominals evangelicals (Guth et al. Reference Guth, Kellstedt, Smidt and Green2006; Guth and Bradberry Reference Guth, Bradberry, Box-Steffensmeier and Schier2013). While there are numerous legitimate critiques of the self-identification evangelical survey question, the question does not produce an overestimation of Republican support among white evangelicals. On the contrary, if holding certain beliefs became part of the evangelical definition, as the NAE proposes and as other religious historians and scholars suggest, evangelical support for recent Republican candidates would be even higher.

The primary results, however, showed important variation among self-identified evangelicals: less devout or nominal evangelical Republicans were more likely to support Trump in the primary. Even in models that control for other religious measures, political ideology, and social traits and predispositions that are correlated with Trump support, the most traditionalist evangelical Republicans supported other Republican candidates while more nominal evangelical Republicans threw their support behind Trump from the very beginning. It is possible that Thomas Kidd and George Marsden's claims that these individuals adopted the evangelical label for political reasons have merit, although additional research is necessary to demonstrate whether this occurred. That said, more devout or traditionalist evangelicals came around most strongly for Trump, even after preferring another candidate to be the nominee, compared to their less devout counterparts who initially supported another Republican candidate. Moreover, similar trends appear when looking at a different set of candidates during the 2012 election. The results, therefore, are not simply the result of the idiosyncrasies surrounding the 2016 election but are instead part of a broader pattern.

The paper then evaluates one claim associated with why evangelicals supported non-traditional candidates, like Trump and Romney, while continuing to take seriously how the measurement of evangelicals might shape the results. I find that negative partisanship, an important predictor of electoral behaviors in recent elections, varies systematically among self-identified white evangelicals. While negative partisanship represents only one of many explanations for Trump's electoral success, the findings illustrate important correlational differences in outlooks based on religious beliefs. Moreover, these results further corroborate the notion that it is important to look at variation within religious traditions and groups (Smidt, Kellstedt, and Guth Reference Smidt, Kellstedt, Guth, Smidt, Kellstedt and Guth2009) rather than to paint members with the same brush. Future research exploring religious variation on other politically relevant attitudes, beliefs, and traits would shed further light into how evangelicals think and act politically.

Importantly, this research does not weigh in on how evangelicalism should be measured on surveys, although this represents an area ripe for future research. Instead, the paper focuses on understanding whether and how incorporating religious beliefs into the definition, would change political scientists' understanding of evangelical public opinion. In particular, the additive scale of beliefs offers a useful strategy for scholars who are interested in incorporating religious beliefs into analyses of white evangelicals but do not want to adhere to an all-or-nothing classification scheme, like the Barna Group and LifeWay Research do. This strategy also allows scholars to uncover important differences within this politically important religious group.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048319000208.