In his speech during the proroguing of the Assembly, His Excellence directed bitter charges at our proceedings, and having accused us in a severe manner before the People, put us in the position of having to justify ourselves before that same People. You have chosen for this justification the voice provided by moderation and the love of harmony. By the siren of the journals, you have spoken on our behalf to the People. Moderation and truth, essential features of any just cause, dictated this Appeal. It will bring light to all of our constituents, if indeed it has not already been viewed by all of them, and will justify our cause among other nations. Hence I have no objection to signing it.Footnote 1

—Jean Dessaules to Jean-Louis Papineau, St. Hyacinth, 12 avril 1827

In the longue durée of petitions and their history in the West, the early nineteenth century represents a high watermark of spatial and numerical proportions. Petitions both mass and individual, both signed and unsigned, across cultures, languages, and geographic space, surged by the tens of thousands and were signed by millions. Their explosion in the context of given social movements is well known. Petition-based mobilizations of the nineteenth-century Atlantic include antislavery in its British, French, American, and other incarnations, including the petitions of free black peoples (Sinha Reference Sinha2016; Carpenter and Topich Reference Carpenter, Topich, Avril and Neem2014); religious liberty, temperance, and other spiritual movements (Szymanski Reference Szymanski2003); labor movements including the mass Chartist petitions of the late 1830s and 1840s (Chase Reference Chase and Chase2015, Pickering Reference Pickering2001); financial politics, including the Bank War in the United States (Carpenter and Schneer Reference Carpenter and Schneer2015); women’s mobilization, particularly in the United States, in the anti–Indian removal and antislavery movements (Carpenter and Moore Reference Carpenter and Moore2014; Portnoy Reference Portnoy2005; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003; Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998; Van Broekhoven Reference Van Broekhoven, Yellin and Van Horne1994); and indigenous activism in North America (Carpenter Reference Carpenter and Parrillo2017; Gohier Reference Gohier2014; Pawling Reference Pawling2010, Reference Pawling2016). Outside of these campaigns, the mass of petitions sent to European and North American sovereigns—kings and queens, legislatures, governors, presidents, bishops, councils and synods, committees, courts and various offices and bureaus—has yet to be documented in a comprehensive fashion. Yet a range of inquiries (Miller Reference Miller, te and Janse2016; Blackhawk et al. Reference Blackhawk, Carpenter, Resch and Schneer2019) suggests that the early nineteenth century saw new peaks of popular petitioning in Britain and the United States.

To a degree little recognized, however, Lower Canada—one of two colonial provinces of British Canada, and that today corresponds roughly with Quebec—lay near or at the epicenter of these upheavals. Possessed of a small population by North American standards (approximately 425,000 in 1827),Footnote 2 Lower Canada hosted political movements of sizable and occasionally violent degrees. And as in nearby Maine, Lower Canadians also petitioned in greater numbers during these years (Watt Reference Watt2006a, Reference Watt2006b). Lower Canada saw one of the continent’s most violent insurrections in the Patriote Rebellion of 1837–1838 (Greer Reference Greer1993), in which a group of Francophone militiamen and habitants (Francophone rural Canadians) raised arms against British troops and were violently suppressed, 365 of them being killed.Footnote 3 Yet in the decades before and after that bloody confrontation, French Canadians signed or marked their assent to petitions by the tens of thousands and effected a measure of change in their institutions as a result.Footnote 4

The historical peak of these petition mobilizations came a full decade before the Patriote Rebellion, in 1827 and 1828, when Francophone Canadians (who called themselves Canadiens) circulated a pair of linked memorials compiling grievances against the colonial governor Lord Dalhousie, and amassed 87,000 names on them. The anti-Dalhousie petition of 1827–1828 received the official assent of as much as one-quarter of Lower Canada’s adult population, a feat all the more remarkable considering that the Canadian population was not concentrated in urban centers but remained spread across hamlets and farming villages, and the complications of traversing many landscapes and waterscapes to visit these populations made canvassing all the more difficult (e.g., there were no signatures from the remote Gaspé peninsula). In five counties, the names of more than one-quarter of the entire population (including First Nations residents) appeared on the anti-Dalhousie petition, and in one county (Trois-Rivieres) more than half the total population (of whatever age) was represented. These numbers are comparable to the height of Chartist agitation in Britain, which happened 10 years later.

No phantom of imagination or activism, the anti-Dalhousie petition of 1827–28 was well known to publics on both sides of the Atlantic. Large parts of it were carried to the House of Commons in 1828, and it was displayed before the provincial legislature in Quebec City as well. It remains today housed at the Stewart Museum in Montréal, Canada, too large and cumbersome to be fully displayed in public. A decade before the explosion of mass antislavery petitioning in the United States, centered upon the 25th Congress of 1837–39 (Carpenter and Moore Reference Carpenter and Moore2014; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003), and a decade before the peak of Chartist petitioning, the anti-Dalhousie petition stands as one of the largest per-capita mass petitions of the nineteenth-century Atlantic world.Footnote 5

The anti-Dalhousie petition was neither a one-off nor inconsequential. Five years before it was drawn up, another petition presenting roughly 60,000 names offered a protest against a proposed union of Francophone Lower Canada and Anglophone Upper Canada that would have erased much of the cultural and institutional distinctiveness of French Canada. Like that 1822 petition, which helped to derail the project of colonial union, the anti-Dalhousie petition of 1827–28 was remarkably effective. A select committee of the British House of Commons in 1828 issued a report largely supporting the Canadien petitioners and, armed with the report, the Crown recalled Dalhousie and replaced him (Atherton Reference Atherton1914: 139; Burroughs Reference Burroughs and Halpenny1988; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 131–33). Other reforms requested by the Canadiens would take more time to come to fruition, but the petition and the committee report had clearly set an agenda for future action and stalled further oppressive measures by Dalhousie and his allies in British colonial administration.

How can we place the explosion of public petitioning in French Canada in historical and comparative context? An initial look reveals a story that upends the customary Anglo-American centrality of petitioning narratives. Why did early-nineteenth-century mass-petition signing arguably peak first not in the English-speaking Old or New Worlds, not in a Protestant milieu, but in a largely Catholic, French-speaking British colony?

The present study only begins to sketch an answer to these questions, and it does so by focusing primarily on the organization of the anti-Dalhousie petition of 1827–1828. We focus upon three dynamics—the broad call for parliamentary democracy (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 94, 136), the organizational and partially linguistic mobilization of provincial interests, and alliance building across Francophone and Anglophone residents as well as urban and rural Canadiens. The anti-Dalhousie petition first gathered so many adherents because they felt that the colonial governor had repeatedly threatened the autonomy of their provincial legislature, to the point of rejecting its speaker and proroguing it in 1827 (ibid.). At a time of growing ethnic, linguistic, and political conflict, Lower Canadians saw in their assembly the true—with Dalhousie as governor, the only genuine—representative of their interests.

Second, the attempt to advance arguments and amass thousands upon thousands of names gestures to the multiple audiences of the anti-Dalhousie petition. Its organizers tried to convince not only the British Parliament but also the far-flung publics of Lower Canada. To accumulate names on paper, the organizers held large assemblies in county seat by county seat, parish by parish, attended by hundreds and occasionally more than a thousand souls. The mass petitions were circulated, explained and signed in French, and their organizers were as likely to call them a requête, a plainte, and an Appel as a pétition (Muller Reference Muller2017).

Third, Lower Canadians tried explicitly to build an alliance with Anglophone residents and merchants who wanted provincial autonomy. They included notable Anglophones among their organizing elites, they gestured to the ideals of the American Revolution, and they structured their signature-gathering efforts in ways that made allied Anglophone Canadians more likely to sign. Canadiens also drew upon Anglo-American precedents in making their case, highlighting the primacy of the lower chamber in the English Constitution, pointing to the American Revolution and even to Bolívarian energies in their justification for constitutional reform (Blanchet Reference Blanchet1824: 11; Harvey Reference Harvey2005).

This mixture of French Canadian, Anglo-American, and revolutionary ideals led rural French Canadians into a heightened attachment to representative institutions in the province and to newly created organizations at the local level. These institutions—the assemblée générale (general meeting), the comté (county), even the paroisse (parish) with its conseils de fabrique (lay church ministries; Greer Reference Greer1993)—attracted growing allegiance from habitants, and Canadiens justified them with ever-greater ferocity, organizing committees at all levels. Petitions defending these institutions against perceived and real threats grew ever more common and strident in the 1810s and 1820s, to the extent that habitants began to organize against the wishes of their own Catholic clergy (ibid.: 60–68). In the 1820s, however, lower Canadians expressed their allegiance to one institution above all others: the province’s lower chamber—la Chambre d’Assemblée (Assembly)—whose existence and functioning became especially important for the idea of popular, geographic representation. The evermore fractured nature of Canadian society pitted these rural habitant communities against bishops, farmers against seigneurs, French against English, Catholic against Protestant, periphery against metropole. The Canadiens adhered to a mix of parliamentary ideals and constitutional principles. The English constitution they defended was, in its ideal type, that of the United Kingdom, but more specifically it was the variant of what they called “the Constitution of this province”—Bas-Canada, namely—one they found superior to all others of the English colonial and postcolonial form, even those in the United States.Footnote 6

A detailed consideration of these petitioning movements permits not only a richer understanding of the petitioning histories of the Atlantic world but also that of Canadian history. What has been rendered elsewhere as a parliamentary crisis (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012), a colonial uprising (Greer Reference Greer1993), or linguistic and cultural conflict (Courtois and Guyot Reference Courtois and Guyot2012; Harvey Reference Harvey2005), can also be interpreted as a form of “democratization by petition,” a movement whose successes were impelled as they were limited by what petitioning could bring them.Footnote 7 That Lower Canada remained a separate province, that its colonial governor was unceremoniously jettisoned, that its lower chamber regained control over revenues in 1831, and that (later) the province did away with the vestiges of feudal land tenure (Baillargeon Reference Baillargeon1967: 80; Michaud Reference Michaud1982), can all be traced in part to Francophone petitioning movements. Our saga of Lower Canadian petitioning in the age of democratization begins with colonial conflict, peaks with the anti-Dalhousie petition, and ends with a brief comparative examination of Quebec in North Atlantic history.

Le Réveil Patriote: The Turn against Imperial Administration

In the wake of the Conquest of 1760 and the American Revolution, Britain’s colonial project in Canada project rested uneasily on the tensions of an enterprise far less attractive economically than initially hoped, a largely Francophone population, and financial constraints that made investment a dubious undertaking (Lawson Reference Lawson1989: 37–41). In ways symbolic and real, Britain quickly gave up the hope of far-reaching colonial development, having passed the Quebec Act of 1774 that returned to French Canadians much of their religious institutions and cherished civil law. After the American Revolution, Britain launched a constitutional reform process that produced the Constitution of 1791. Amending the Quebec Act, the 1791 Canada Act established two provinces, Lower Canada (corresponding largely to areas of French majority) and Upper Canada. Colonial leaders understood that the idea of the Constitutional Act of 1791 was to give Lower Canada to French Canadians and Upper Canada to English settlers (Select Committee on the Civil Government of Canada (hereafter SCCGC) 1829a: 29). It was to Upper Canada where Tories had fled after the American Revolution, and this region was endowed with English common law. Lower Canada retained civil law (including feudal tenure) and Roman Catholic institutions.

The Constitution of 1791 gave Canada its first representative assemblies.Footnote 8 The popular house in Lower Canada was the Chambre d’assemblée colonial (Assembly). Property requirements for the franchise were so low as to distribute voting rights more broadly than in the United States (SCCGC 1829b: 11), and habitants held a forceful majority in elections to the Chambre d’assemblée. The Assembly was accompanied by an upper chamber called the Legislative Council (Conseil législatif), that was appointed from members of the landed elite. The colonial governor (also appointed by the Crown) had an Executive Council at his disposal, whose membership overlapped heavily with the Legislative Council (Greer Reference Greer1993: 113–15; SCCGC 1829a: 3, 29). The Assembly had control over public expenses and control over appointments to the civil list. But the control over public expenses was limited to those revenues coming from laws passed after 1791, particularly for special projects and current expenses (Brun Reference Brun1970: 231). In the case of deficit, moreover, the governor had the ability to dip into the military funds (caisse militaire) without asking the Assembly (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 96). These provisions deeply compromised control of government expenses by the lower assembly, which was so central to parliamentary republics in Britain and the United States.

In the early 1800s, economic, cultural, and international developments combined to stoke both aspirations and tensions in Lower Canadian politics. Canadiens saw revolutionary changes occurring elsewhere in the continent, including mass suffrage expansions and constitutional reform, and the Bolivarian revolutions further south. A long decline in agricultural productivity, which started early in the new century, would reach crisis proportions in the 1830s (ibid.; Greer Reference Greer1993). The economic fates of habitants stagnated while those of seigneurs (French and English) stabilized.

From 1805 onward, Pierre Bédard (an Assembly deputy) established the philosophical and ideological foundations of a provincial movement premised upon parliamentary sovereignty, aspirations of democracy, and Francophone primacy. In the midst of a struggle over taxation, he founded the French language journal Le Canadien in 1806, calling for primacy of the Assemblée in provincial matters. Bédard’s program—one called réformiste in light of its purported fidelity to “true” British constitutional principles—quickly became both inspiration and lightning rod. Bédard championed a strict idea of the constitutional mixed regime and specific proposals to strengthen Lower Canadian popular institutions. Theoretically, he saw in Lower Canada’s institutions a parallel to those of the Crown—the colonial governor corresponding to the king, the Conseil legislatif corresponding to the aristocratic House of Lords, and the Assembly corresponding to the people (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 69–70). In reality, Bédard and his allies understood that the king was in control, but they wanted the Assembly to serve as a check and to keep watch on the colonial government. For this reason, Bédard proposed a provincial minister, who could give to deputies the ability to keep watch over the Lower Canadian executive (ibid.: 70–78). These proposals were greeted with contemptuous opposition by the colonial governor of the time—James Craig. After the publication of a poem considered defamatory, Bédard and two other owners of Le Canadien were arrested in March 1810 and the journal was closed. Bédard would reemerge later in the decade, but his idea of a provincial minister disappeared from provincial debate (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 82).

Bédard’s ideas were reflected in Lower Canadian requêtes and other petitions to the Crown. These petitions played an ever-growing role in the development and expression of institutional theory (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2010). Petitions from Canadiens were sent to the Crown (which from 1810 to 1820, meant the prince regent, later George IV, who acted in the place of his incurably demented father George III) calling for greater power for the Assemblée and less power for the Executive Council and, by extension, the Legislative Council. In a tract believed to have been authored by Bédard—Mémoire au soutien de la requête des habitans du Bas-Canada, à son Altesse Royale le Prince Régent (Reference Bédard, Lamonde and Corbo1814)—Canadien voices called for the reform of the Legislative Council, making it elective. They complained that by taking up the very liberties guaranteed by the charter of 1791 and rendering plaintes and requêtes, they were being flattened (terrassés) and tarred as an illegitimate opposition.Footnote 9 Bédardians argued further that the appointed members of the Legislative Council—the “gens en place”—could not possibly govern with justice the very population from which it derived its taxable resources except by Canadiens, at least in a consultative fashion (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2010).Footnote 10

The man succeeding Bédard as leader of the Parti canadien—Joseph-Louis Papineau—became the unquestioned leader of a movement with hybrid and ambiguous identities—reformist, republican, nationalist. Papineau converted Bédard’s intellectual case into potent popular symbolism and an increasingly democratic ethos. Papineau became Speaker (Orateur) of the Assemblée in January 1815 and more than anyone in the history of the province, he incarnated the nation canadienne and articulated its aspirations and arguments for reform. In the absence of a head of government and elected ministers, the Speaker was the institutional voice of the province’s people, what poet Louis Frechette called the human bullhorn (l’homme porte-voix) who converted the forum into a public display of his own making (la tribune en créneau) (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 109). Papineau’s ascendance also came after the War of 1812, when North American antipathies to many things British were on the rise, and when Lower Canadians viewed arrangements and personalities in the United States with increasing favor (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 89; Lamonde Reference Lamonde2012).

With the appointment of Sir George Ramsay, Lord Dalhousie, as colonial governor in 1820, the stage was set for one of North America’s grand confrontations of the century. Papineau refused Dalhousie’s invitation to sit on the Legislative Council in 1820. Then, quietly in the summer of 1821, Dalhousie and his allies hatched a plan to unite the two Canadas under a system that would have privileged English models of settlement, culture, and law. Anglophone elites saw the plan as a way to circumvent the French-dominated Assembly. In June 1822, a bill was introduced to the Commons to this effect, and later that month the news reached Québec and Montréal, jolting French Canadians and their allies into unprecedented activism.

The proposed union of 1822 provoked the first monster petition of Canadian history, a document signed in total by more than 60,000 subjects and sent to the House of Commons in October. The petitioners advanced a deeply Bédardian argument, claiming allegiance to the Constitution and its provision for popular representation in the provincial Assembly. Like the later Dalhousie petition, the anti-union petition was delivered to the Commons by Papineau and by the printer John Neilson, a critical Anglophone ally of the Canadiens. Subjects supporting colonial fusion subjects signed and circulated a counterpetition of approximately 10,000 signatures, but the unionist project was quietly interred (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 96–97). Although the agitation over the union plan was short-lived, the plan and the caustic nature of Dalhousie’s administration awakened the strongest anti-imperial sentiments in the province since the American Revolution (Buckner Reference Buckner1985: 112–21; Harvey Reference Harvey2005: 10; Manning Reference Manning1962: 151–70; Ouellet Reference Ouellet1976).

The organization of the anti-unionist petition campaign drew on the many templates of organization and attachment coursing through Lower Canada of the 1820s, and it set critical precedents for the anti-Dalhousie monster petition circulated five years later. Canadiens carried out much of the petitioning through committees formed at the county, district, and other levels, relying on comités régionaux and assemblées régionaux.Footnote 11 While serving to manage the petition canvassing effort, these structures attracted fidelities of their own, as representative vessels enjoying local trust. Even as they expressed allegiance to the realm and the British constitution, these gatherings also evoked concepts that that echoed institutions from ancien régime and Revolutionary France and New France—regional assemblies, estates general at the national and regional levels (and the requêtes, plaintes, and cahiers that issued from them).Footnote 12 Popular demonstrations also partook of legislative and republican imagery. At the same time, a popular gathering entitled a grande assemblée aggregated thousands of people on Montréal’s Champ de Mars on October 7, 1822.

Contributing as much as anything to the political efflorescence, Lower Canada witnessed a cultural transformation characterized by changes in education and print culture and a rise in provincial pride (Courtois and Guyot Reference Courtois and Guyot2012; Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: ch. 3; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 100–1). Physicians Joseph-François Perrault and Louis Plamandon founded the Société d’éducation de Québec in 1821, and new schools for secondary education were established. (Francophone physicians would play an important role in the emergence of patriote organization.) A new editor of Le Canadien, Flavien Vallerand, would take up the Bédardian banner, and the newspaper would republish many of the important republican petitions in the decade. An 1824 law established new “écoles de fabrique” in numerous parishes in the province. In Montréal, two leaders of the patriote movement, Augustin-Norbert Morin and Denis-Benjamin Viger, created a new newspaper, La Minerve, which enjoyed a wide readership, and sales of French language volumes, generally, surged in Montréal and Québec. As testament to the impact of these journals, Dalhousie criticized their “democratic” character (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 103–4).

Political tracts and petitions surged and intermingled as part of this cultural renaissance. François Blanchet—a physician and deputy in the Assembly, and an old friend of Bédard—published Appel au Parlement impérial et aux habitans des colonies anglaises (1824), which called for fundamental reform in the parliamentary institutions of Lower Canada, with full Assembly control of public expenses and reduction in the power and executive dependence of the Legislative Council (Blanchet Reference Blanchet1824). Petitions with similar arguments flowed into, and out of (toward Britain), the Assembly.Footnote 13 Blanchet’s pamphlet displayed a hemispheric imagination, expressing and invoking sympathies for Simón Bolívar and movements associated with him, for example. Two years later, Viger published Analyse d’un entretien sur la conservation des établissements du Bas-Canada, des loix, des usages &c de ses habitans (1826). As its title suggested, and in an echo of the 1822 petitions against colonial union, Viger and his allies tied together language, customs (usages), institutions (établissements), and laws (loix).Footnote 14

Dalhousie saw these developments as worrisome and he moved aggressively to counter them. Infuriated by the Canadiens’ analogy between their movement and that for Irish independence, he echoed James Craig’s argument that the parti canadien was engaged in illegitimate, “factious” opposition to the Crown (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 97, 104 fn. 26). John Richardson went further, comparing the Assembly’s activities to those of rebels in the period of Charles I and to those of the Comité du Salut public during the Reign of Terror in revolutionary France (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 83).

Far more contentious than any of Dalhousie’s public arguments were his procedural initiatives before the Assembly. With the plan for colonial fusion abandoned, Dalhousie attempted to press forward with a unilateral program of administrative governance unencumbered by popular resistance. He demanded the Assembly vote appropriations for the entire reign of George IV, rather than sanction spending for a single year or session. In December 1821 he called for the summary approval of his civil appointments. The Assembly passed a more limited budget in 1823, but this was rejected by the Legislative Council. Well beyond Papineau, prominent Canadiens such as Laurent Bédard, Flavien Vallerand, and Francois Blanchet began to defend the authority of the Assembly, especially with respect to control of revenues and control over the civil list (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 84–85; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 97–98). The Assembly elections of 1824 returned an even larger majority for the parti canadien.

Dalhousie returned to Britain in 1824 and his temporary replacement, Francis Burton, comported himself in far more conciliatory manner to the Assembly. Convoking the Chambre in January 1825, Burton struck a set of agreements with Papineau. Together, governor pro tempore and Assembly quickly voted and appropriated spending and slashed the province’s deficit. Dalhousie, learning of these developments from London, was furious that his principles had been undermined through compromise with the Assembly. Upon his return, he declared that the Burton-Papineau compromise of 1825 was invalid and was not a precedent he was prepared to follow in the future.

Confronted with widespread press outrage and an unruly lower chamber, Dalhousie prorogued the Assembly in March 1827 (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 87; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 99–100, 114–15). The prorogation, executed without having consulted London first, further eroded Dalhousie’s legitimacy in Lower Canada and London alike. Prorogation made new elections necessary, and for the assembly elections in the spring of 1827, no question was more important than that of Assembly powers, especially over revenues and appointments.Footnote 15 The elections returned yet another large gain for the Canadiens, and Papineau and his allies felt emboldened. Yet Dalhousie was in no mood to respect the election results for the lower chamber. Blaming Papineau for most (if not all) of his problems, including the growing perception in London that the colonial governor and not the French population was responsible for the colony’s disarray, Dalhousie rejected the Assembly’s choice of Papineau as Speaker (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 114–15). In the midst of these battles, the parti canadien was renamed the parti patriote, and a reform movement became a republican cause (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 87).

The Organization of the Anti-Dalhousie Petition

The idea of a second monster petition in five years might have seemed risky to the Canadiens. Yet Dalhousie’s intransigent and unilateral actions in 1826 and 1827—his rejection of Papineau as Orateur de l’Assemblée and his dismissal of critical or Canadien-allied militia captains in the middle of an election season—combined with the success of the parti canadien in the elections of 1826, left French Canadian leaders furious and seeking drastic action. The decision to send a petition to the Commons, listing complaints against Dalhousie and the lack of separation of powers, was apparently undertaken separately (but without coordination) in both Montréal and Quebec in early 1827 (SCCGC 1829a: 66).

French Canadians were not the only petitioners from Lower Canada in 1827. Petitions from “Townships of the Lower Province” had also been received by the Commons, asking for redress of the grievances of English inhabitants of Lower Canada, including ease of settlement, and for the union of the two provinces under English law (ibid.: 1). The demand for colonial union was unlikely given its rejection in 1822 and 1823, and the House quickly pronounced its disapproval when this was proposed in 1828.

Seigneuries Versus Townships

The more nuanced issues raised by English petitioners concerned the law of property in Lower Canada, which implemented English custom or French custom depending on whether the land was in a township or a seigneurie, respectively. Of far more than legal importance, the contrast and tension between of these sites of property and language acquired growing political, partisan and electoral significance (Greer Reference Greer1993; SCCGC 1829a: 11–40, 49–52).

The seigneuries where French Canadians largely lived were located on narrow tracts of land on either side of the St. Lawrence River, 10 to 40 miles in width. “Behind” those seigneuries, the colony had granted townships, and these attracted English settlers. In the townships land was given by free and common soccage. The seigneuries and townships represented quite different worlds, even though the former had many English speakers and French speakers had settled in the latter. In French civil law—most of it derived from the Coutume de Paris—both the rights and the administration of property differed materially from the common law. The legal distinction shaped gender and family relations. In the French system, marriage established two rights: dower and communauté. Wives were entitled to half of the communauté (i.e., half of the entire personal property of the husband) and half of the real property he had acquired during the marriage. This was a considerably more generous system for women compared to laws governing couverture in the United States, for instance. Under the Coutume de Paris, the wife’s property could not be alienated under any will of the husband (SCCGC 1829a: 23–24). If an English settler died with only personal property, the property would be distributed according to French law (ibid.: 24). These partial advantages for widows plausibly led to widows’ agitation for voting rights in Montréal and Quebec in the late 1820s and 1830s, a movement impelled by petitioning (Bradbury Reference Bradbury2011).

Seigniorial rights were another source of contention, in part because English settlers believed them to retard economic development. Those who lived on seigniorial lands did not have the right of “mutation” (under which settlers could in theory render improvements) without the consent of the seigneur. Under the droit de moulture, inhabitants could neither build their own mill on the seigneur’s property nor take their grain to any mill other than the seigneur’s. So constructed, the droit de moulture provided for a major portion of the seigneur’s revenue (Greer Reference Greer1993; SCCGC 1829a: 38–39).

The legal and political systems governing Lower Canada remained a separate source of frustration for English settlers. To facilitate the efficient transfer and inheritance of property through common law, court records were required to establish land boundaries, improvements, and declension of ownership. In Lower Canada these records were kept in the seigneuries and, for more comprehensive records, at either the seat of administration or the provincial legislature in Quebec. English petitioners from the Lower Canadian townships asked for British courts to be established in the townships. Furthermore, election sites for the townships were located in the seigneuries, leading to negligible township participation in elections to the Assemblée.

The Canadiens were aware of these issues, and support for the seigneurial system was far from uniform. Yet in the 1820s, the primary issues animating Francophone opposition had little to do with defending feudal tenure, seigneurial rights, or marriage systems. The Canadiens’ main concern lay in the behavior of Dalhousie and the institutional framework that left the Assemblée unable to check the government. The ability of the governor to dismiss the people’s choice for Speaker, the proroguing of the Assembly for failure to appropriate funds for the civil list, and Canadiens’ fears that Dalhousie would eventually attempt extract revenues from Lower Canada without Assemblée consent were all perceived as significant grievances by Canadiens.

A further issue was the growth of the Legislative Council. The original 1791 Act gave the Assemblée not less than 50 members and the Council not less than 15. By 1828, the Assembly still had 50 deputies but the size of the Council had nearly doubled to 28 (SCCGC 1829a: 31). As the Legislative Council grew, Dalhousie increasingly filled it with officers from the imperial government. The critical separation between the executive and legislative—a fundamental characteristic of the mixed regime, the British constitution, and the Montesquieuvian ideal—had broken down. The 1827 petitioners complained that

the Legislative Council is nothing other than the executive under a different name, and the provincial legislature finds itself reduced to two branches, the government and the Assemblée, without having the advantage of any middling, mediating branch given to this province; and from this first and capital error a multitude of evils have resulted and continue daily, with no capacity for remedy.Footnote 16

These misgivings had been present for some time, but Dalhousie’s behavior fulfilled the worst fears of the Canadiens. Dalhousie responded to the Assembly elections of 1827 by snubbing the people’s choice of Speaker. Later that year he dismissed a range of militia officers from their posts, largely because of their observed support for the parti patriote (or for Papineau).Footnote 17 Officers in the milice occupied a position of great status, notability, and income, and the militia dated from the pre-Conquest period of New France (Dessureault Reference Dessureault2007: 176–78; Greer Reference Greer1993: 100–7). Some of the officers that Dalhousie sacked had fought in the War of 1812 on the British side (Dessureault Reference Dessureault2007: 190), and many were Anglophone. In a widely distributed declaration of protest, published in October 1827, Thomas Lee accused Dalhousie of trying to embarrass him before his fellow citizens—of unfairly advancing “evil, false and hurtful insinuations”—and of acting in an illegal manner.Footnote 18 Lee’s rhetoric, and that of other dismissed officers such as Renè-Amable Boucher, articulated claims against despotism and arbitrary executive power to Canadiens. These arguments formed part of the culture of written and signed protest that exploded in the fall of 1827.

Dalhousie’s behavior and beyond that, his poor reputation, provided the petitioners with some of their strongest arguments. Papineau and his allies understood that an effective attack on Dalhousie would, by extension, embarrass the Colonial Office and put in doubt the Crown’s colonial project. Accordingly, the petitioners of 1827 blamed Dalhousie for the economic stagnation of the colony, a situation that had attracted the ire of colonial officers in London (Burroughs Reference Burroughs and Halpenny1988; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012). Behind these institutional grievances lay two more metaphysical arguments, both in keeping with the Bédardian reading of the British constitution. First, the governor was neither king nor Parliament. Unlike the king who could do no wrong, the governor could be brought to account for his decisions, not just by the king but by Parliament (Ducharme Reference Ducharme2010: 75). Presenting the governor as fallible and replaceable, and contrasting him with previous, more conciliatory governors such as Burton, enabled the petitioners of 1827 to align constitutional logic with political imperatives. Second, the rejection of Papineau as Speaker and the proroguing of the Assembly provided the petitioners with an opening. For within the British parliamentary tradition, it was the Speaker who represented the lower chamber and therefore the people (or electors), in communicating to the king (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 107–8, 125). In the absence of an Assembly with a Speaker, to what, to whom, could the Governor respond? To what, to whom, could the king and his Parliament respond? The monster petition of 1827 thus occupied a liminal space: it uniquely and powerfully represented the colony of Lower Canada in the absence of a lower chamber and its speaker.

Assemblées Générales and Comités Spéciaux: The Organization of a Monster Petition

Like so many petitions of the early nineteenth century, the monster anti-Dalhousie petition of 1827 was an amalgam of canvassing efforts and even of slightly different prayers. Two different prayers circulated, one in Montréal and Three Rivers (reflecting resolutions adopted in Montréal) and a second in Quebec and county of Warwick (reflecting resolutions adopted at Québec) (SCCGC 1829a: 66–67). John Neilson later reported that “there was no concert” between the Montréal and Québec resolutions (ibid.: 66). Yet contemporaries in London and Lower Canada understood that a centralized, committee-based structure had amassed the tens of thousands of signatures, and that although the Montréal and Québec resolutions differed slightly, they referred to the larger effort as a single petition.

In their organization and their rhetoric, Canadiens drew upon older political languages that incorporated metaphors and terms from the ancien régime of New France as well as the Revolutionary period. For example, organizers and signatories alike often described the monster petition as a requête rather than pétition, which was by this time part of the French political vocabulary (see Agnès Reference Agnès2018; Muller Reference Muller2017). Meanwhile, Englishmen described petitions as “petitions,” sometimes as “memorials” or “remonstrances,” but never as requests. Papineau described the Montréal petition as a requête, even when grievances composed its primary content, and lead organizers of the collection effort, summarizing their 87,000-plus signatures, referred alternatively to “la Requête de Montréal” and “la Requête de Québec.”Footnote 19 In county after county, organizers met by calling an assemblée générale, a term that had more meaning in French institutional history than in English. The assemblée générale was a common meeting in ancien régime France, especially at the provincial level or within estates, dating to the sixteenth century or earlier. Many communautés of the Provence region held assemblées générales, as did the region itself (Busquet Reference Busquet1920; Hildesheimer Reference Hildesheimer1935). In the seventeenth century and afterward, entire estates (such as the clergy in 1682) held assemblée générales (Blet Reference Blet1995). At the end of the ancien régime Jacques Necker and others created assemblées provinciales to act as consultative bodies, and it was no coincidence that post-Revolutionary France created (and periodically recreated) an Assemblée Nationale.

In Lower Canada, anti-Dalhousie petitioners created assemblées générales at the level of the county (comté), sometimes in the district, and other assemblées de la paroisse (parish). The assemblées générales would then appoint a petitioning committee, specifically a comité constitutionnel or, at the parish level, a comité spécial or comité général. In districts of Montréal, the comité constitutionnel was charged with drawing up a prayer and circulating the petition for signatures, while in Quebec a committee was nominated by the assemblée générale of the electors of the city and surrounding towns.Footnote 20

Contemporary descriptions of the petitioning process by organizers and petitioners suggest that the mainspring of the reform and republican movements lay in the assemblées. After the passing of resolutions at Montréal and Québec, anti-Dalhousie petition organizers then proceeded by county. In Comté Richelieu, the assemblée générale appointed a Comité Général, charged with the responsibility to gather both signatures and subscriptions to assist the canvassing effort.Footnote 21 Small towns such as St. Denis recorded assemblées générales of more than 1,000 persons, all free electors and property holders according to the records. Among the top signatories in these petition sheets (later aggregated into the larger petitioning effort) were many physicians. After a preliminary committee read the resolutions, special committees (comités spéciaux) were appointed to gather signatures by parish. Often the parish held another assemblée, such as the one held in the church of Sainte Anne at Yamachiche on New Year’s Day in 1828. Every comité spécial operating at the level of the parish was authorized by the assemblée générale, and every such parish-level effort had been funded by the subscriptions gathered at the assemblées. A rhetoric and a material logic of legitimacy coursed through the efforts that affixed thousands upon thousands of signatures upon the anti-Dalhousie memorial.Footnote 22

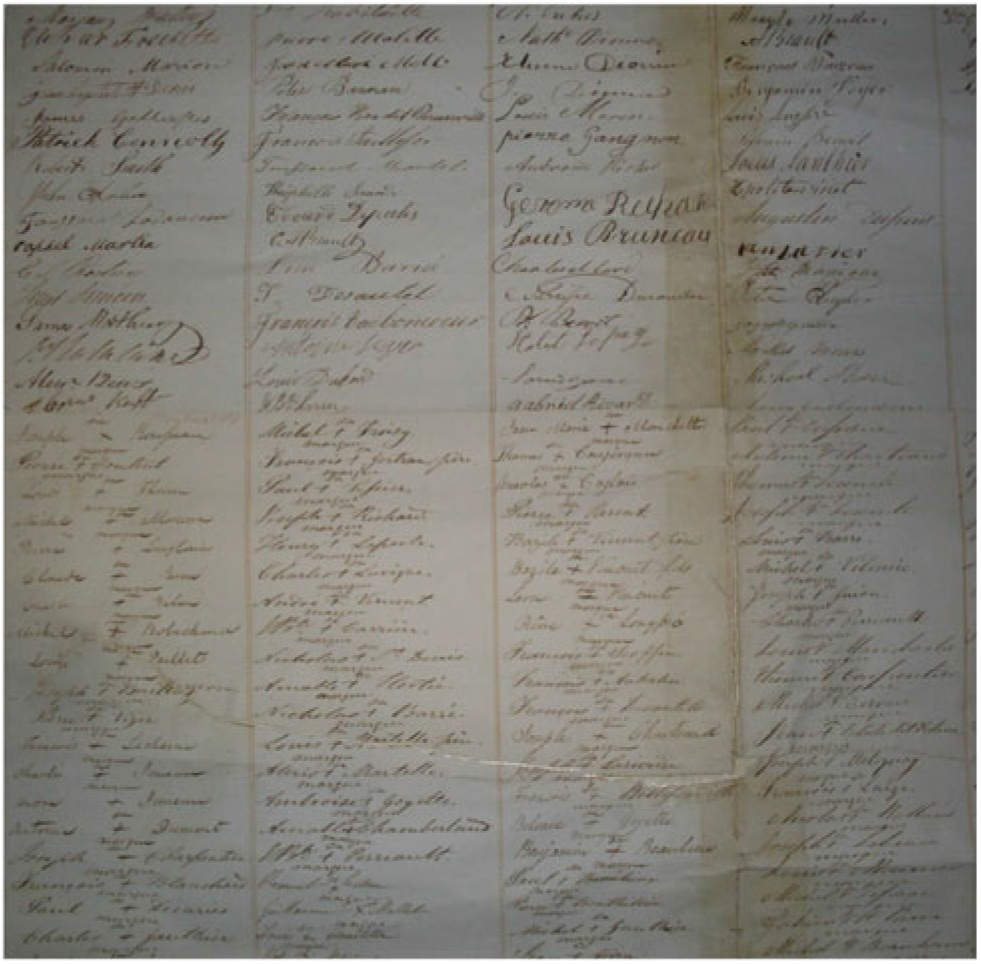

The petitioners of 1827 aimed to impress the Commons with argument and with the heft of signatures. As figure 1 suggests, the petition when amassed and rolled became a formidable, weighty object, displaying thousands upon thousands of names in linear order (figure 2), many signed, many accompanied by marks. Because only part of the petition appears in figure 1, the visual impression made by the petition was at least as large as would appear from the museum display.

Figure 1. Part of the monster petition in display at the Musée Stewart, Montréal.

Figure 2. Signatory list from the 1827 monster petition, Musée Stewart, Montréal.

Signature Patterns in Montréal: A Statistical Sample and Analysis

The vast mass of names affixed to the petition invites both interpretative and quantitative analysis. Examining an unrolled portion of the anti-Dalhousie petition and signatory list that offers 10 pages of signatures from Montréal, we compiled a sample of 1,864 names. The sample demonstrates something of the physical effort of signing and canvassing. Each page has as many as six columns of signatures—figure 2 is cropped to show four of them, across two pages—each of which listed up to 39 names (usually between 33 and 37). Signatures appear to have been entered vertically within columns, and the columns were filled from left to right, meaning that each potential signatory would have been able to view the signatures above and to the left.

The utility of this sample is limited by being from Montréal as opposed to more rural areas where a larger proportion of names were affixed to the petition. However, the Montréal signatures are significant in showing both the French Canadien leadership of the petition, but also the participation of English-speaking Canadians. Using their commercial and marriage networks, the Canadiens recruited English merchants to forge a cross-linguistic coalition in support of their political demands (Bradbury Reference Bradbury2011). To examine the presence of non-French names upon the signatory list, we adopt a measurement strategy based upon French surnames as coded by genealogists. Using the Surname Listing from the American-French Genealogical Society, we coded a name as French if the surname matched that in the society’s list. Surnames not present in this database or that represented clear corresponding Anglicizations (e.g., Connor, Smith, Taylor) were coded as non-French. More ambiguous surnames such as Waller were examined and, in our case, coded as non-French surnames. Being premised upon names, the coding strategy is subject to measurement error, yet the systematic variation of surname clusters across signatory list pages that we observe (see Table 1) suggests that our method is identifying kinship, linguistic, and ethnic networks.Footnote 23

Table 1. Analysis of “top” Montréal sample from anti-Dalhousie petition (sample of 1,864 names)

Source: Signature list from Pétition des comtés des districts de Montréal et des Trois Rivières; numéro d’inventaire 1957.6, Musée Stewart, Montréal. Data entry, coding, and analysis by authors.

Notes: Odds ratios retrieved from fixed-effects logit estimation, with fixed effects estimated for each column (within page) of names. Odds ratios are interpreted as difference from unity (null value), such that (for instance), an odds ratio of 1.02 implies that with every one-name movement down in a given signature column, the odds of a surname cluster increase by two percent.

* Indicates statistical difference from one (null value) at p < 0.10 (two-tailed test).

** Indicates statistical difference from 1 (null value) at p < 0.05 (two-tailed test).

To examine the possible aggregation of signatures and marks by kinship networks, we code surname clusters of surnames within 10 vertical signatures of one another, or 5 vertical signatures (using alternative distance measures yields substantively identical results). We also examine “horizontal” clustering, examining the presence of identical surnames in adjacent columns, within three vertical lines in either direction. For example, if a signatory’s surname appears on line 20 of the 3rd column and a mark or signature by someone with the same surname appears on the 18th through 22nd line of the 4th column, the signature is marked as a “lateral co-sign.” In certain cases, this appears to be one of the only ways in which surname clustering occurred, as there are many cases in which a series of surnames unfolds laterally but not longitudinally on the signatory page, often near the bottom of a signatory page where, one surmises, the organizers had left space at the end of columns and where additional clustered signatures needed to be entered horizontally to fit on the signatory page.

A summary statistical description of the Montréal pages sample appears in Table 1. The first thing to note about the statistical summary is there is considerable variance across pages—some pages have all names signed while adjacent pages have all names with marks, and there are similar discontinuities across page breaks in non-French surnames and in surname clustering. This pattern suggests that each page was likely the result of a separate petitioning and canvassing effort. What remains in the Musée Stewart, as with so many other larger petitioning efforts, is the glued-together composite of a number of separate (albeit orchestrated) petitioning efforts.

Analysis of the signatory lists of the anti-Dalhousie petition reveals important information lurking in the order in which names appear (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2016; Nall et al. Reference Nall, Schneer and Carpenter2018). On the first and second pages of Montréal signatures, English names appeared with higher frequency, and English names appeared higher in columns, plausibly generating further inducement to sign or give a mark of assent for potential Anglophone signatories. For every rank move downward in the sequence of signatures (e.g., 11th to 12th, or 3rd to 4rth) in a column on these two pages, the odds of a non-French name declined by 3 percent. These early pages of the Montréal signatory list were important for attracting Anglophone elites (such as William Galt, owner of a large leather tanning business, the nail manufacturer Thomas Bigelow, Henry Ferns or Thomas Barber, all whom signed near the top of the first full signatory page). As the Table 1 regressions show, moreover, surname clusters tend to appear lower in columns; odds ratios above one indicate a positive association between column order (descent in column) and the odds of a signature being part of a surname cluster. This dynamic likely expresses strategic placement of individual notable names at the top of each column (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2016), allowing families to add collective signatures below.Footnote 24

The Countability of Voice, and Political Opportunities for Women

The era of surging petitioning across the Atlantic world was an age of new voices and their aggregation. Everywhere protestors, lobbies, electors, officials, and petitioners pointed to their numbers as legitimating their cause. Contests between rival petitioners over the signature numbers were struggles over who could claim the greater legitimacy and who could speak in the name of the people. For example, Anglophone proponents of colonial fusion had assembled a signatory list with more than 10,000 names, which was bettered by Canadiens amassing six times as many, which they recognized was instrumental in derailing the union project. Anglophone subjects in Lower Canada argued, of course, that their numbers represented those of the true settlers, and allied with Dalhousie, they set about disparaging Canadien signatures as coming from those who were not the true or authentic settlers in the colony, or by claiming that the total numbers for the 1827 petition were higher than that of the entire (Francophone) colony at the time of British takeover (1763) (SCCGC 1829b: 343, 355).

The battle over numbers and legitimacy played out in the questioning of signatures and their authenticity. Rather than claiming that Francophone signatories carried less weight than English-origin or Anglophone signatories, Dalhousie and his allies scoured the signatory list and sought to gather and report examples of alleged fraud to undermine his opponents. Any signature that seemed copied or sufficiently similar to others nearby, or that was accompanied by a mark, was treated by Dalhousian officials as evidence of fraud, an inappropriate injection of religious affiliation into a constitutional debate, showing people had been unaware of the addition of their names or not fully aware of the petition’s content. As with many monster petitions of the period, not all signatures were in unique manuscript, and this was more pronounced in rural areas where literacy ran lower (Table 2). Yet Canadiens responded by showing that many English names had signed the petition, which was further demonstrated by Papineau’s ally John Neilson in his presentation of presented signature samples to the Select Committee of Parliament in 1829 (Table 2).

Table 2. Signature patterns of the anti-Dalhousie Petition (1827) presented by John Neilson to the House of Commons

In their quest to undermine the monster petition, Dalhousie and his allies uncovered evidence of political awakening across different groups. As they scrutinized the signatures, government officials found that women and children were signing. George Moffatt would write to Dalhousie in 1827 that “A notorious circumstance occurred in Montréal of a whole school of females being marched in files to affix their names to the petition of grievances to the Sovereign.” One Thomas Porteous later testified that “he is enabled from undoubted authority to say, that he verily and firmly believes that little Girls were conducted into Dr. N’s [Neilson’s] house for the express purpose of signing the said Petitions, and that they did actually sign them, as if the Deponent had seen them write their names, and he has further been credibly informed that they were instructed not to sign their Christian names in full but only the initial letters thereof, in order that their sex might not thereby be known.”Footnote 25

The petition signatory list from Montréal includes women’s signatures. Our research on the Montréal sample reveals at least seven female names or signatures from that city: Belonie Goyette dit Sansouci, Serapha Verge, Charlotte Magnonée, Marianne Boulagée, Angélique Lehay, Gabrielle Blais, and another Belonie Goyette. Of these seven names, three are represented by marks. Our sample from Faubourg Saint Laurent includes at least two additional women—Elizabeth Troy and Marie St. Garmin—both of whose names were signed. That women would openly sign in Montréal is not entirely surprising, given that more than 200 women later showed up to the polls for the city’s by-election in April and May 1832 (Bradbury Reference Bradbury2011: 260–75; see also Watt Reference Watt2006a: 123). Furthermore, because many of the signatures on the Montréal petition list only the first initial and last name, we are quite possibly undercounting women’s names on the petition.Footnote 26

Dalhousie’s allies were less concerned about women signing than young women signing, and they eagerly compiled evidence of young boys having signed as well. Reporting what he perceived to be the scandal of four “french Canadian boys” who boasted of having signed a petition to the king, Thomas Porteous reported that the eldest (under 12, he confidently proclaimed) admitted he did not know how to write, but along with his classmates (numbering 30) they had made a cross. Another testimonial reported that a father, learning of his son and classmates signing a petition, asked to have his son’s name erased, but was told that the signatory list had already been sent to regional committees for delivery to the king and House of Commons in England.Footnote 27

It is important to read these accusations of children’s and women’s participation in context, as the complaints of officials seeking to denigrate the legitimacy of the petition. Yet the Canadiens never denied these charges, and the inclusion of women and children points to the wide range of popular participation within the anti-Dalhousie movement. The signatures of schoolchildren also have to be situated within the context of the erection of many Francophone schools as well as Canadien pressure for greater in the province. Overall, the debates of the legitimacy or illegitimacy of signatures suggests the competing frames of legitimacy used by Dalhousian officials and Canadiens in 1827 and 1828.Footnote 28

The evidence adduced for signatures by children suggests the intricate network structures relied upon for petition signing. In Montréal and Québec, Canadien merchants and booksellers played an important role in the display of the petition and the collection of signatures. Many a Montréal signature was affixed to the petition at the bookstore of Edward R. Fabre & Co. of Rue Notre-Dame in Montréal, a seller of books in law, literature, and Catholic theology that sat facing the colonial government’s Palais de Justice.Footnote 29 Dalhousie partisans fumed that the Montréal committee appointed to draw up the petition was “anonymously called” but everyone knew that the meeting occurred at the store of one “M. Quesnel,” probably Jules Quesnel, a Montréal notable, member of the Assembly, and a common participant on grand juries in the province (Addresses 1828: 28–29; Select Committee of the House of Assembly of Lower Canada 1829: 6–7, 189).

Signatures and Marks: The Question of Authenticity

The question of authenticity is relevant not only to understanding Loyalist-Patriote tensions in the 1820s and 1830s, but also in answering the question of whether the anti-Dalhousie petition represented an awakening political consciousness in the province. William Huskisson, who became colonial secretary in September 1827, took the claims of the petition’s prayer seriously, but also remarked that of the 87,000 names on the petition, only 9,000 had truly been signed, an indication of the lack of intellectual development in the province. Elite Anglophones insulted those who signed with a mark by calling them “Knights of the Cross,” a moniker that linked their Catholic majority to their supposed illiteracy (Groulx Reference Groulx1930: 11, Brady Reference Brady1967).

The presence of so many marks in place of self-inscribed signatures represents, in many thousands of cases, the signatory’s lack of literacy (see Watt Reference Watt2006a: 135–38). There remains the real possibility that Lower Canadian elites merely induced illiterate peasants, habitants and other residents to sign something whose content they could not have fully understood. It is, nonetheless, important to place this dynamic in context.

The question of authenticity and representation among those advancing their voice was a common problem in petitioning (Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003), and just as common a problem in voting in the nineteenth century, where studies point to drunken, poorly organized electorates in the United States (Bensel Reference Bensel2004), among other nations. Yet there are some reasons to suggest that the marks reflected a degree of volition. First, petition organizers attested on each page that the marks represented the result of a presentation process in which the language and intent of the petition was explained verbally to those whose names appeared with a mark. The repeated character of this statement, in different handwriting, suggests that organizers and canvassers were at least aware of the norm by which they were obliged to explain the petition’s prayer to those whose names were affixed with a mark. One biographer remarked that even literate Lower Canadians were often permitted their names to be added by mark, as “a very large number of people who truly could sign didn’t want to go to the trouble, and were content to allow another to affix their name” (Gosselin Reference Gosselin1903: 140). The considerable variation in many pages of marks inscribed, moreover, casts doubt on the most extreme explanation that the marks were simply entered by one organizer.Footnote 30

Contemporaries took note, too, of the wide level of political discussion in 1827 and 1828. Jean-Marie Mondelet wrote to Denis-Benjamin Viger in April 1828 that “[a]ll of our residents now take part in public affairs, knowing them and discussing them. This unfortunate crisis in which we find ourselves will at least have the effect of opening their eyes.” Mondelet had been integrally involved in the monster petitioning effort, and as he was expressing these views privately to a fellow patriote it may be suggested that he had little incentive to misrepresent the state of affairs. Another contemporary remarked Lower Canadians of all ages, most notably the young, had become much more radical and that “almost everywhere political galvanization had gained the lead” (Bibaud Reference Bibaud1844: 307). The petition also stimulated further political participation from women. In December 1828, women from Quebec supported a petition for granting voting rights to widows, which advanced an argument for woman suffrage more generally, and the Assembly also debated claims that “the votes of women, married, unmarried, and in a state of widowhood” had been cast that year for the antiestablishment reformer Wolfred Nelson.Footnote 31

The role of local assemblées générales and provincial legislators in organizing the petition also points to a more participatory process, though one in which local notables exercised some leadership, including making speeches. In Montréal, the role of the “Committee of Grievances” and of the assemblées in the petition process, led by Papineau, became etched into popular memory, perhaps more so than the petition (Chapais Reference Chapais1920: 326; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 126). The assemblée générale at Saint Denis gathered at least 1,000 persons, according to contemporary records. Another assembly at the parish of Sainte Anne de Yamachiche—held in the public meeting room of the church, which suggests the possible assent of the priest—appointed a committee of 12 men to gather signatures, charging them with “drawing upon all their forces to gather voluntary subscriptions and signatures to the petition.” In Trois-Rivières, where the names of more than half the population appeared on the anti-Dalhousie petition (see Table 4), the notable lawyer Charles-Elzear Mondelet spoke publicly and was active in the constitutional committee. Provincial deputies at Trois-Rivières (including some of the same members who would organize the anti-Dalhousie petition effort there) had also canvassed for a range of petitions from habitants and parishioners from 1821 to 1829 (Audet Reference Audet1934: 34–42; Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 126). Both the skill of the organizers and the evident mass of meetings and other petitions suggests a widely circulating discourse of politics in the 1820s.Footnote 32

Finally, even given the presence of so many marks upon the petition, there is reason to doubt Huskisson’s estimate, which was not based upon any thorough examination of the entire signatory list but was repeated many times over in the nineteenth century, apparently without verification. The entirety of the petition cannot be examined today as much of it remains rolled; it seems doubtful that entire petition signatory list had been examined by the Colonial Secretary, either. Yet samples presented by Neilson to the Commons in 1828 suggest a rate of names signed at about twice that of Huskisson (Table 3), and when one focuses on Quebec, Neilson reported a names-signed rate of 40 percent. Our own investigation of aggregates from Montréal, Faubourg Saint Laurent and Faubourg des Recollets suggests names-signed rates ranging from 24 to 46 percent of names on the petition. These estimates are, of course, drawn from more densely populated urban towns, with higher education and literacy rates, yet some of locales that supplied the highest rate of names (Trois-Rivières, for instance [see Table 4]) had similar populations.

Table 3. Different estimates of the signing versus marking patterns of the anti-Dalhousie petition, 1827–28

Note: Authors’ sample signature list from Pétition des comtés des districts de Montréal et des Trois Rivières; numéro d’inventaire 1957.6, Musée Stewart, Montréal.

Table 4. Aggregate signature patterns on the anti-Dalhousie petition (1827)

Sources: Population figures and signatures from Report SCLC (1829). Signatures from “Récapitulation des Signatures en date du 6 février 1828,” Appendix 2, Report SCLC (1829). Total listed here is 80,909. The commonly cited total of 87,000 is obtained by the addition of 6,212 additional signatures collected from the districts of Montréal, Trois-Rivières, and Québec between February 6 and 17, 1828.

Patriote Recruitment by Petition

The anti-Dalhousie petition requires interpretation as a bundle of documents, each with multiple audiences. If the patriote organizers’ sole aim was to persuade the Commons or colonial secretary of the authenticity of each name, then the marking pattern makes little sense. Yet if the organizers’ aim was manifold, and included the amplification and circulation of grievances to those who did not read the newspapers and were not hearing from the clergy who tried to maintain a neutrality toward the colonial administration (Greer Reference Greer1993), then the marks represented not legitimacy but an understanding that tens of thousands of illiterates and those who would not bother to sign had at least heard the petitioners’ argument. Because the goal of the petition was in part to inform and mobilize the Lower Canadian populace, local audiences remained as or more important than those in London.

Petition organizers, especially leaders of the parti patriote such as Papineau, Viger, Cuvillier, and others also understood that the canvassing and subscription effort would generate new ties of solidarity at the local level. Coming in the wake of the prorogation of the Assembly, the monster petition served not only to demonstrate the unified voice of an aggrieved people to a British sovereign but also to present a case to the people (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2016). As Jean Dessaules wrote to Papineau in April 1827, the petition was necessary to present an alternative case to the very people before whom Dalhousie had tried to embarrass the Assembly, and the canvassing effort would bring “light” to the Canadiens.Footnote 33

The recruitment value of the petition provides one rationale for why organizers spent so little time circulating the petition in townships. Not only were townships dominated by Anglophone interests, they were also far removed from voting sites and consequently had poor turnouts in elections. Anglophone Lower Canadians were much more likely to turn out to vote in the cities, and the Papineau network did in fact target them for petition signatures. As in 1822, moreover, the townships sent a separate petition to the Commons (SCCGC 1829a: 52). The selective nature of the canvassing effort is difficult to demonstrate with granular quantitative data, but an aggregation of the signatures by comté, presented in Table 4 and analyzed in Table 5, provides a glimpse. Table 4 summarizes the population, township population, and number of monster petition signatures for 81,000 of the 87,000-plus signatures on the petition. For those comtés where names were affixed, township-heavy comtés such as Bedford, Buckingham, and York had lower signature totals as a percentage of population, while nonmetropolitan comtés with little or no township population such as Leinster, Surrey, and Warwick saw more than 3 in 10 residents with their names on the signatory list. (Trois-Rivières, where the names of more than half the population were represented on the signatory list, represented a max of residential patterns, with an industrial center surrounded by seigneuries.) Given the fact that signatures and marks were largely limited to property-owning adult men, these rates are all the more remarkable.

Table 5. Log-log regression of county signature totals upon population and seigneurial composition (coefficients from OLS regression, interpretable as elasticities, standard errors in parentheses)

We present simple regression analyses of these comté-level aggregations in Table 5. The small-sample nature of the comté-level aggregations greatly constrains the inference that we can make. When the logarithm of signatures is regressed upon the logarithm of the explanatory variables, however, the resulting coefficient estimates can be interpreted as descriptive elasticities (percentage change in one variable associated with percentage change in another). The numbers should be regarded as associations only, not as evidence of any causal relationship. Yet two broad patterns emerge. First, the size of the estimated elasticities shows just how heavily concentrated the canvassing effort was in seigneuries. A 10 percent increase in the seigneurial population (controlling for total population) was associated with a 39 percent increase in signatures from that county. Similarly, a 10 percent increase in the fraction of comté population in seigneuries was associated with a 42 percent increase in the percentage of comté inhabitants who had signed the petition. Second, seigneurial residence aggregates are sufficient to account statistically for almost all of the comté-level variation in signature totals (the adjusted R-squareds are at or above .90). The organization of the canvassing effort—outward from metropoles—helps to clarify why petition signatures were low in the English-language townships near the St. Lawrence River seigneuries but also on the Gaspé peninsula, where amongst a large French-language population there were no signatories to the monster petition of 1827–28.

The French-Canadian Petitioning Surge in Historical and Comparative Context

With the petitioning effort of 1827 having amassed some 80,000 signatures, an additional 6,000 to 7,000 names were added in early 1828 and a comité was appointed to deliver the petition to London. Papineau had led much of the petitioning effort but did not sit on the Comité de la pétition de 1828. Instead, three other top players in Canadien politics, Neilson, Viger, and Austin Cuvillier were charged with traveling to London to appear before the House of Commons.Footnote 34

The end of the story is better known than the preceding narrative of the petition. The Commons appointed a Select Committee on the Civil Government of Canada to hear the concerns and complaints alleged in the petition as well as the testimony of the men who delivered it. The petition provided an opportunity to the radical faction of the Whig opposition to attack the government while the Select Committee report disparaged the actions of the Assembly, it reserved far worse criticism for Dalhousie and his colonial policy (Curtis Reference Curtis2012: 61; SCCGC 1829a). Dalhousie was recalled from service in 1828, transferred to India (Atherton Reference Atherton1914: 139; Burroughs Reference Burroughs and Halpenny1988). The Select Committee did not grant all of the Canadiens’ wishes, but advocated for greater power of the Assembly in fiscal matters.

Within a few years, the demands of the anti-Dalhousie movement had received some statutory satisfaction, but had also engendered the perceived radicalization of the Assembly. A key request of the petition was seeking legislative control over the various revenue streams authorized for the colony by the Crown, especially the duties imposed by the 1774 Quebec Act. In 1831, and in response to the report of the “Canada Committee” of 1828, Parliament returned revenues gathered under the 1774 Act to the control of the Lower Canadian legislature. Contemporaries and historians of the ensuing decades generally pointed to the 1828 committee report and to the anti-Dalhousie petition as the basis for the 1831 statute, as well as the Assembly’s acquiescence in funding appointments to the civil list from these revenues (Barrow Reference Barrow1838: 1331–32; Brun Reference Brun1970: 231, 247–49; McLean Reference McLean1898: 743; Tuttle Reference Tuttle1877: 371–72; Walpole Reference Walpole1910: 116–17). As evidence that the anti-Dalhousie petitions had been effective, British members of Parliament soon complained that the 1831 Act had been too generous, and that the patriote faction in Lower Canada had violated “the implied confidence, conditions and expectations on which the Parliament of Great Britain had been induced to pass the Bill which gave the Legislature of Lower Canada control over the whole revenues, always excepting the casual and territorial revenues of the province.” The growing demands of the patriote movement included another mass petition in 1834 (Petition from Lower Canada 1835), as well as the 92 Resolutions the same year, and the global economic crisis of 1837 would eventually combine with these tensions to feed into the Patriote Rebellion (Greer Reference Greer1993).Footnote 35

Monster petitions had, in a span of six years, helped to derail a unionist initiative (thereby preserving Lower Canada as a separate, Francophone jurisdiction), oust the colonial governor, and institute reforms that expanded the power of the Assembly. In the longer run, petitioning can be credited with giving French Canada a modicum of provincial independence (1822, 1828), preserving a minimum of parliamentary sovereignty (1827–28), and abolishing a form of feudalism in the 1840s (Baillargeon Reference Baillargeon1967). As one writer concludes, the debate over Dalhousie provided a formative school in democracy (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 123, 134), and while hundreds if not thousands of the conversations that went into the signing of the monster petition are irrecoverable, it seems an inescapable conclusion that the anti-Dalhousie petition of 1827–28 served something of an educational purpose as well.

Well beyond their effectiveness in British parliamentary politics, the monster petitions had played a role in galvanizing and organizing the Canadien people, through both its rhetoric and organization, and the petitions deserve a book-length study. The rhetoric of the petition’s prayer, which voiced arguments that were clearly repeated and rehearsed in the manifold conversations of its canvassing, the monster petition distinguished itself by its defense of the Lower Canada’s provincial constitution, not just Anglo-American institutions. It was the constitution de cette province, and not the nineteenth-century British constitution, that attracted the greatest fidelity from Canadiens. Even as they took inspiration from the American Revolution and Bolivarian Revolutions to the South, Lower Canadians, like Viger, saw their province as the best of all English colonies present or former, including the United States (Harvey Reference Harvey2005; Viger Reference Viger1826). They directed these energies more than anything else at the preservation of their powers and their identity in the Assemblée.

As the anti-Dalhousie petition’s arguments championed the Assemblée writ large, the massive accumulation of signatures on the petition expressed a form of popular government through assemblées writ small. Authorizing and funding their canvassing effort by assemblées générales, couching their grievances as a requête, canvassing by paroisse and meeting in churches, Lower Canadians revived an older language of politics, one that proclaimed ideals from the French Revolution even as it gestured to institutions and practices of the ancien régime.

For French and English Canadians alike, democracy was a long way off in the 1820s. Yet the contest with Dalhousie had awakened aspirations to parliamentary democracy,Footnote 36 and in the everyday organizing and political assembly that took place throughout the province in 1827 and 1828, rather different facets of incipient democratization appeared: the mobilization of popular voice, the ethic of equality in the identity of names unfolding upon the pages of a mass signatory list, and later petitioning campaigns that included calls for woman’s suffrage almost two decades before a movement would crystallize in the United States. The precise partial contribution of the petitioning effort is impossible to quantify, but the fact that Mondelet could remark in 1828 that “All of our residents take part in public affairs, know them and discuss them” (Gallichan Reference Gallichan2012: 134) marks a level of information and deliberation that simply would not have occurred without the mass petitioning effort.

Considered in comparative perspective, the Lower Canadian monster petition of 1827–28 deserves analysis not just for its size but also for its method of mobilization and signature gathering. The template of metropolitan, elite leadership, followed by assemblée générales at the level of comtés, followed by mobilization at the parish level, produced a hybrid of centralized prayer and decentralized canvass. This hybrid organization may help explain how so many marks and signatures were gathered from a highly rural and nonliterate population. The eruption of signatures and marks from far and wide in Lower Canada was no epiphenomenon of elite lobbying. Patriote leaders saw the petition’s true audience not just as the Commons and the colonial secretary, but as the tens of thousands of Francophone Lower Canadians, along with pivotal Anglophone allies. Further, more granular inquiries of the monster petition and others will help clarify these dynamics, but that will begin only once French-language documents begin to receive due attention in comparative analyses of petitions in Europe and North America. Alongside the Chartist movement, the antislavery movement in the United States, and other initiatives, the Canadien monster petition of 1827–28, along with the antiunion petition of 1822, deserves consideration as among the most vital mass canvassing and petitioning efforts of the global nineteenth century.

Archival Sources

BAnQ: Bibliothèque and Archives nationales du Québec—Archives de Vieux-Montréal, Montréal, Québec

Fonds Jobin

Fonds Comité de Pétition de 1828

LAC: Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Canada

Fonds Dalhousie

Fonds Neilson

Fonds Papineau

Records of the Colonial Office

McCord: McCord Museum of Canadian History, Montréal, Québec

Badgley Family Papers

George Etienne Cartier Papers

McGill: McGill University Rare Books and Special Collections, Montréal, Québec

Thomas Storrow Brown Papers

Special Collection: Seminary of Saint-Sulpice

Special Collection: Records of the Executive Council, Legislative Council and Governor

Musée Stewart, Montréal, Québec, Canada

Pétition des comtés des districts de Montréal et des Trois Rivières; numéro d’inventaire 1957.6