Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis patients suffering from headaches due to repeated frontal sinusitis episodes are commonly seen in ENT practice. Acute inflammatory exacerbation of the frontal sinus is a risk factor for intracranial and/or intraorbital complications, such as brain abscess.Reference Fokkens, Lund, Mullol, Bachert, Alobid and Baroody 1 Inflamed, thickened mucosae and mucopurulent secretions in the frontal sinus and the presence of frontal recess cells narrow the frontal drainage pathway. This can consequently block drainage, thereby contributing to frontal sinusitis pathogenesis. Topical and/or systematic pharmacotherapy using antibiotics and corticosteroids is recommended to manage the inflammation. Surgery is indicated for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis who are refractory to topical and medical treatments. The best option is functional endoscopic sinus surgery to pneumatise and drain the frontal sinus, which involves enlarging the frontal sinus drainage pathway. Three procedures were described by DrafReference Draf 2 : type I, simple drainage; types IIa and IIb, extended drainage; and type III, endonasal median drainage. The FESS procedure can be performed when the frontal sinus drainage pathway is difficult to identify due to osteoplastic obliteration, and has therefore expanded the range of indications for endonasal frontal sinus surgery. Where type III drainage is technically impossible or has failed, external surgery is indicated. The frontal sinus is one of the most anatomically complex and inaccessible parts of the sinonasal area.Reference Chen, Wormald, Payne, Gross and Gross 3 Frontal sinus surgery must therefore be performed using angled endoscopes by proficient, experienced surgeons. However, there is always a risk of injury to adjacent tissues, such as the base of the skull, orbit and anterior ethmoidal artery, which may result in serious intracranial and intraorbital complications. To perform frontal sinus drainage safely, full anatomical knowledge of the sinonasal area, especially the frontal recess cells and the frontal sinus border area, is necessary.

The number of patients with eosinophil-dominant (i.e. eosinophilic) chronic rhinosinusitis is increasing.Reference Tokunaga, Sakashita, Haruna, Asaka, Takeno and Ikeda 4 The most effective therapeutic strategy is usually to combine topical and/or systemic corticosteroids and endoscopic sinus surgery. In such patients, computed tomography (CT) images show opacification of the posterior ethmoid sinus and the olfactory cleft at an early stageReference Ishitoya, Sakuma and Tsukuda 5 ; in contrast, the maxillary sinus predominates, extending to the anterior ethmoid sinus and frontal sinus, in non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis.Reference Zinreich, Kennedy, Rosenbaum, Gayler, Kumar and Stammberger 6 Therefore, differentiating eosinophilic from non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis is critical to an analysis of pathogenesis.

This pre-operative radiological study aimed to assess the anatomy of frontal recess cells in chronic rhinosinusitis patients.Reference Kuhn 7 Cells within the frontal recess that strongly influence frontal sinusitis development were identified and associations of frontal sinusitis with eosinophilic vs non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis were determined.

Materials and methods

Patients

A case series study of 93 patients (186 sides) who underwent primary sinonasal surgery at Hyogo College of Medicine between April 2015 and March 2016 was performed. In all, 64 male and 29 female patients with a mean age of 49 years (range 13–83 years) were included. The presence of cells and their opacification (i.e. inflammation) status were investigated bilaterally in the frontal recesses of all patients. Patients with tumour-associated disease, trauma or history of any sinonasal surgery were excluded. The study conformed to the regulations of the ethics committee of Hyogo College of Medicine (approval number 1512).

Eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis was diagnosed according to the criteria of the Japanese Epidemiological Survey of Refractory Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis.Reference Tokunaga, Sakashita, Haruna, Asaka, Takeno and Ikeda 4 A total score from four items of at least 11 points was necessary for diagnosis: bilateral lesions (3 points); nasal polyps (2 points); ethmoid sinus dominant or pansinusitis on CT (2 points); and the percentage of blood eosinophils – more than 2 per cent and up to 5 per cent (4 points), over 5 per cent and up to 10 per cent (8 points) or over 10 per cent (10 points).

Patients were divided into three groups: an eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group (n = 32, 64 sides), a non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group (n = 49, 98 sides) and a control group without sinusitis (n = 12, 24 sides). Patients in the eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis groups underwent endoscopic sinus surgery, and those in the control group underwent septoplasty and inferior turbinate surgery under general anaesthesia.

Radiological analysis of the frontal recess and frontal sinusitis

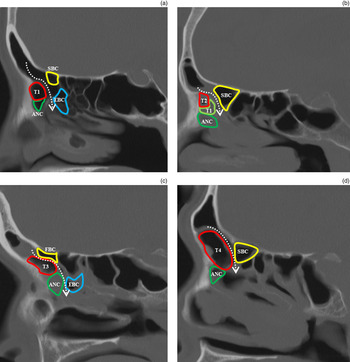

Kuhn's classification of frontal recess cellsReference Kuhn 7 (Table I) was used by three rhinologists to determine the presence and degree of opacification of agger nasi, types 1–4 fronto-ethmoidal, ethmoidal bulla, suprabullar and frontal bulla cells on pre-operative sinonasal axial, coronal and sagittal CT images (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Sagittal sinonasal computed tomography scans showing identification of frontal recess cells. Fronto-ethmoidal cells are classified as (a) type 1 (T1), (b) type 2 (T2), (c) type 3 (T3) and (d) type 4 (T4). Dotted arrows indicate the frontal sinus drainage pathway. ANC = agger nasi cell; EBC = ethmoidal bulla cell; SBC = suprabullar cell; FBC = frontal bulla cell

Table I Frontal recess cell types in the anterior ethmoid sinus

The severity of chronic rhinosinusitis was assessed on sinonasal CT images using the Lund and Mackay scoring system and a scoring system previously reported by the present authors.Reference Lund and Mackay 8 , Reference Tsuzuki, Hinohira, Takebayashi, Kojima, Yukitatsu and Daimon 9 Opacification (indicating inflammation) of the maxillary, frontal, anterior and posterior ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, and olfactory clefts was scored as: 0, not opaque; 1, partially opaque; or 2, completely opaque. Opacification of the ostiomeatal complex was scored as: 0, not opaque; or 2, opaque. Thus, the maximum possible total CT score was 14 points per side. Frontal sinusitis was defined as partial (1 point) or complete (2 points) opacification of the frontal sinus.

Relationships between (1) the presence of frontal recess cells (anatomical factors) and frontal sinusitis development and (2) opacification of frontal recess cells (inflammation) and frontal sinusitis development were evaluated.

The relationship between frontal sinusitis and the anterior–posterior diameter of the frontal ostium was investigated (Figure 2a). For this, the anterior–posterior diameter was defined as the shortest distance between the most prominent portion of the frontal beak and the posterior table of the frontal sinus. Effects of laterality on the anterior–posterior diameter of the frontal ostium and the relationship between the anterior–posterior diameter and frontal sinusitis were investigated.

Fig. 2 (a) Sagittal sinonasal computed tomography image showing the anterior–posterior diameter of the frontal ostium (indicated by the dotted arrow). (b) Graph showing the mean anterior–posterior diameters for the right and left sides (error bars represent standard deviation (SD)). (c) Graph showing individual and mean ± SD anterior–posterior diameter values in frontal sinusitis and non-frontal sinusitis patients. NS = not significant

Statistical analysis

Associations of the presence and opacification status of frontal recess cells with frontal sinusitis were analysed using χ2 tests. Results between groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated. All p values are two sided and p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stat Flex version 6.0 software (Osaka, Japan).

Results

Presence of frontal recess cells and frontal sinusitis

Frontal sinusitis was observed in 42 per cent of sides (78 out of 186; Table II). Computed tomography showed partial and complete opacification of 53 per cent (41 sides) and 47 per cent (37 sides) of frontal sinuses, respectively. Agger nasi cells were observed in 99 per cent of sides (184 out of 186). Fronto-ethmoidal cells were noted in 38 per cent of sides (71 out of 186): 20 per cent of cells were type 1 (38 out of 186), 1 per cent were type 2 (1 out of 186), 15 per cent were type 3 (28 out of 186) and 2 per cent were type 4 (4 out of 186). Ethmoid bulla cells, suprabullar cells, and frontal bulla cells were identified in 100 per cent (186 out of 186), 69 per cent (128 out of 186) and 16 per cent (29 out of 186) of sides, respectively. The presence of frontal recess cells was not significantly associated with frontal sinusitis development.

Table II Presence of frontal recess cell and frontal sinusitis

CI = confidence interval; ANC = agger nasi cells; FEC = fronto-ethmoidal cells; EBC = ethmoidal bulla cells; SBC = suprabullar cells; FBC = frontal bulla cells

Anterior–posterior diameter of the frontal drainage pathway and frontal sinusitis

The anterior–posterior diameter of the frontal ostium was significantly larger on the left side (8.57 ± 2.35 mm) than on the right side (8.03 ± 2.48 mm; Figure 2b). There was no significant difference in anterior–posterior diameter between patients with (8.31 ± 2.22 mm, 78 sides) and without (8.28 ± 2.55 mm, 108 sides) frontal sinusitis (Figure 2c).

Comparisons among patient groups

Frontal sinusitis was significantly more common in the eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group (81 per cent, 52 out of 64 sides) than in the non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis (27 per cent, 26 out of 72 sides) and control groups (0 per cent; Figure 3a). The frontal sinus score was significantly higher in the eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group (1.22 ± 0.75, n = 64) than in the non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group (0.38 ± 0.68, n = 98). The total CT score was also significantly higher in the eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group (8.8 ± 3.1) than in the non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis (2.9 ± 3.1) and control (0.0 ± 0.2) groups (Figure 3b).

Fig. 3 (a) Graph showing the proportions of each patient group with frontal sinusitis. (b) Box and whisker plot showing computed tomography (CT) scores in each patient group. Mean ± standard deviation values are shown. ECRS = eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis

Opacification of frontal recess cells and frontal sinusitis

In the eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group, the proportion of agger nasi, type 1 fronto-ethmoidal, and suprabullar cells showing opacification was 96 per cent (50 out of 52 sides), 100 per cent (8 out of 8), and 95 per cent (35 out of 37), respectively. The presence of opacification was significantly associated with frontal sinusitis development in this patient group (Table III). In the non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group, the proportion of ethmoid bulla, agger nasi, type 1 fronto-ethmoidal and suprabullar cells showing opacification was 85 per cent (22 out of 26), 92 per cent (24 out of 26), 100 per cent (7 out of 7) and 73 per cent (11 out of 15). The presence of opacification was also significantly associated with frontal sinusitis in this patient group (Table IV).

Table III Frontal recess cell opacification and frontal sinusitis in the eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group

*Data show opacification / presence (%) for each cell type. CI = confidence interval; ANC = agger nasi cells; FEC = fronto-ethmoidal cells; EBC = ethmoidal bulla cells; SBC = suprabullar cells; FBC = frontal bulla cells

Table IV Frontal recess cell opacification and frontal sinusitis in the non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group

*Data show opacification / presence (%) for each cell type. CI = confidence interval; ANC = agger nasi cells; FEC = fronto-ethmoidal cells; EBC = ethmoidal bulla cells; SBC = suprabullar cells; FBC = frontal bulla cells

Discussion

A radiological investigation into the presence of frontal recess cells in the region of the frontal sinus drainage pathway and their percentage opacification in pre-operative CT scans of patients who underwent sinonasal surgery was performed. Relationships between these measures and frontal sinusitis development were assessed.

Agger nasi cells and ethmoid bulla cells were detected in more than 98 per cent of patients, and the proportions of fronto-ethmoidal (38 per cent) and frontal bulla (16 per cent) cells were similar to those previously reported.Reference Han, Zhang, Ge, Tao, Xian and Zhou 10 – Reference Krzeski, Tomaszewska, Jakubczyk and Galewicz-Zielinska 16 The most commonly identified cells were fronto-ethmoidal (71 sides), type 1 (54 per cent, 38 out of 71) and type 3 (39 per cent, 28 out of 71) cells, whereas type 2 (1 per cent, 1 out of 71) and type 4 (6 per cent, 4 out of 71) fronto-ethmoidal cells were rarely seen. The proportion of images showing suprabullar cells (68 per cent) was higher in the present study than in previous studies (range 11–40 per cent).Reference Han, Zhang, Ge, Tao, Xian and Zhou 10 – Reference Lai, Yang, Lee, Lin, Chu and Wang 14 The presence of fronto-ethmoidal (types 3–4), suprabullar and frontal bulla cells is reported to significantly influence frontal sinusitis development.Reference Meyer, Kocak, Smith and Smith 17 , Reference Lien, Weng, Chang, Lin and Wang 18 As frontal bulla and types 3 and 4 fronto-ethmoidal cells grow into the frontal sinus and narrow the frontal sinus drainage pathway, these cells may physically block passage through the frontal ostium. In contrast, DelGaudio et al. and Eweiss et al. reported that fronto-ethmoidal cells do not influence frontal sinusitis development.Reference DelGaudio, Hudgins, Venkatraman and Beningfield 19 , Reference Eweiss and Khalil 20 The present study similarly found that the presence of frontal recess cells is not a significant influence on frontal sinusitis development. It is possible that frontal sinus pneumatisation is maintained when the frontal sinus drainage pathway is narrowed and is only prevented by complete obliteration of the pathway. To investigate this possibility, frontal sinus drainage should be studied at the cellular level, for example by assessing ciliary function.

In the present study, the mean anterior–posterior diameter of the left frontal sinus was larger compared with the right frontal sinus, as previously reported.Reference Gotlib, Kuzminska, Held-Ziolkowska and Niemczyk 21 This is because the right hemisphere of the human brain continues developing until a later growth stage compared with the left, thus reducing the final size of right frontal sinus. There was no significant difference in frontal ostium size between patients with and without frontal sinusitis in this study. Therefore, frontal sinusitis may be caused by inflammatory changes in frontal recess cells rather than changes in frontal ostium size.

Inflammatory opacification of agger nasi, suprabullar and type 1 fronto-ethmoidal cells significantly influenced frontal sinusitis development in both eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis patients (Tables III and IV). Consistent with this finding, DelGaudio et al. proposed that mucosal inflammation is a major contributory factor in the pathogenesis of frontal sinusitis.Reference DelGaudio, Hudgins, Venkatraman and Beningfield 19 Most cases of non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis (primarily affecting the maxillary sinus) show initial inflammatory changes and impaired ventilation in the anterior sinonasal area.Reference Bolger, Butzin and Parsons 15 In contrast, most cases of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis (primarily affecting the ethmoid sinus) show initial inflammatory changes in the posterior sinonasal area, such as the posterior ethmoid sinus and olfactory clefts.Reference Ishitoya, Sakuma and Tsukuda 5 Bilateral pansinusitis was predominant in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis patients, whereas partial sinus opacification was predominant in non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Although the mean total CT score was significantly lower in the non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group than in the eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group, ethmoid bulla cell opacification in the non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis group significantly influenced frontal sinusitis development. These data suggest that thickened mucosae and secretions due to inflammation of frontal recess cells (agger nasi, type 1 fronto-ethmoidal, ethmoid bulla and suprabullar cells) may block the frontal sinus drainage pathway and consequently influence frontal sinusitis development, even if the sinonasal area is only partially inflamed. For surgical management of frontal sinusitis, it is particularly important to remove these inflammatory cells to enlarge the frontal sinus drainage pathway.

There is a need to plan and perform safe and adequate sinus surgery for frontal sinusitis. This is difficult because the frontal sinus is one of the most anatomically complex and inaccessible parts of the sinonasal region for FESS.Reference Chen, Wormald, Payne, Gross and Gross 3 The present radiological study identified critical sites for FESS in the frontal sinus. A comprehensive understanding of the anatomy of the frontal sinus drainage pathway based on CT could help pre-operative planning. However, as frontal sinusitis is caused by various factors, including anatomical variation and mucous membrane inflammation, larger multidisciplinary studies aimed at defining the factors influencing this disease are required.

-

• Acute inflammatory exacerbations in the frontal sinus are a risk factor for intracranial and/or intraorbital complications

-

• Inflamed, thickened mucosae and mucopurulent secretions in the frontal sinus and frontal recess cells narrow the frontal drainage pathway

-

• This study analysed frontal recess cells in pre-operative radiological images of chronic rhinosinusitis patients

-

• The presence of frontal recess cells did not significantly influence frontal sinusitis development

-

• Opacification of agger nasi, suprabullar and type 1 fronto-ethmoidal cells significantly influenced frontal sinusitis development in both eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis patients

-

• A full understanding of the frontal sinus drainage pathway is required for surgical management of frontal sinusitis

Conclusion

Frontal sinusitis is caused by inflammatory changes in frontal recess cells. Complete removal of inflamed agger nasi, type 1 fronto-ethmoidal, ethmoid bulla and suprabullar cells is important for the surgical management of this condition. A full understanding of the anatomy of the frontal sinus drainage pathway is also required.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Ms Y Kida and Mrs M Tanide. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI; numbers JP25462671 and JP16K11220), the Practical Research Project for Rare/Intractable Diseases from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and Grants-in-Aid for Researchers, Hyogo College of Medicine, for 2015 (to KT) and 2016 (to KH).