How important a role did priests play in the Western Rising of 1549? Until the 1970s scholars were confident that they knew the answer to this question. Priests, they agreed, had been pivotal to the insurrection.Footnote 1 It was priests who had encouraged the common people of Devon and Cornwall to rise up against the religious innovations of Edward vi’s Protestantising regime in the first place.Footnote 2 It was priests who had been largely responsible for scripting the series of demands which the commons had subsequently sent up to the government in London as the insurrection gathered strength.Footnote 3 It was priests who had led the protestors into battle against the troops whom the boy-king and his ‘protector’ – Edward Seymour, duke of Somerset – had sent into the West Country to subdue them.Footnote 4 And it was priests, above all, who had suffered at the hands of vengeful loyalists as the rebellion was savagely suppressed by government forces under the command of Lord John Russell towards the end of that fatal summer.Footnote 5

But, in an influential article published in 1979, Joyce Youings challenged the orthodox view, suggesting – partly on the basis of the crucial eye-witness account of the rising penned by Exeter's Tudor chronicler, John Hooker – that ‘contemporary accounts of the large number of priests involved’ in the rebellion had been ‘grossly exaggerated’.Footnote 6 Five years later, Youings returned to the charge: casting renewed doubt on what she now termed ‘the legendary leadership of the … rebellion by … priests’ and repeating the claim made in her previous article that the broad coterie of clerics who had long been thought to have led the rising should, in fact, be ‘narrowed down’ to just ‘one [priest] in particular: Robert Welsh, vicar of [the parish] of St Thomas [near Exeter]’, who, as Hooker records, was hanged by loyalists from his own church tower soon after Russell's forces broke through to relieve the besieged city in August 1549.Footnote 7

Youings's scepticism about the supposed ‘clerical leadership’ of the Western Rising helped to inform the work of a second scholar, Aubrey Greenwood, who, in 1990, completed a splendid PhD dissertation on the petitions drawn up by rebel groups during the so-called ‘commotion time’ of 1549.Footnote 8 In his discussion of the Western Rebellion Greenwood launched a powerful attack on the view of the rising as, au fond, a priestly protest which had prevailed for so long. There was little hard evidence to support the view that West Country folk had been inveigled into rebellion by their priests, Greenwood showed, or that the religious grievances which were so prominent among the rebels’ demands had solely reflected the concerns of their (presumed) clerical authors.Footnote 9 Instead, he argued, the people of Devon and Cornwall had risen up largely of their own volition, in defence of the traditional religious ceremonies which formed such a central part of their daily lives, while ‘the religious grievances in the petitions [had] reflected the views of parishioners as well as priests’.Footnote 10 Having adduced a great deal of compelling evidence in support of these two key points, Greenwood then went on to argue that priests had not served as rebel military commanders, or ‘captains’; ‘that the number of priests involved in the rebellion’ had been ‘exaggerated’; and that the entire ‘notion of priestly leaders was a myth’.Footnote 11

Greenwood has made a vital contribution to the ongoing scholarly debate about the Western Rising, and, as the conclusions of his thesis become more widely known, it seems probable that bald assertions that the rising took place at the direct instigation of conservative clergymen will become far less commonplace in the historical literature relating to the insurrection than they have been hitherto. Nevertheless, it is important not to take such revisionism too far, and while Greenwood has convincingly refuted the old assumption that the rebel rank-and-file were simply puppets dancing to a priestly tune, the jury may still be said to be out on the wider argument which he – and, still more trenchantly, Youings – have advanced to the effect that the number of clergymen involved in the rising has been ‘(grossly) exaggerated’. A profitable way of moving the debate forward would obviously be to re-examine the total number of priests who can be shown to have been killed or executed during the rebellion and its immediate aftermath: not least because it was largely on the basis of the supposedly scant evidence for such killings that Youings questioned the traditional view of the insurrection as one in which many priests had been involved.Footnote 12 The present article will therefore conduct just such an examination. It will begin by reviewing what previous historians have had to say about the killing of priests by loyalist troops and gentlemen during July–September 1549, and will then move on to reconsider what the primary sources reveal about that same grim subject. In the process, the article will not only shed new light on what has been described as ‘the most puzzling of all Tudor rebellions’, but will also produce evidence which tends to undercut previous claims that ‘the weapon of terror … [was] used but sparingly [against conservative priests] during the process of the [English] Reformation’.Footnote 13

I

The modern historiography of the Western Rebellion may be said to begin with the publication in 1913 of Frances Rose-Troup's monumental book on the rising: a work which continues to exert an abiding influence over historians’ views of the emeute to this very day. Rose-Troup explored the question of clerical fatalities during the insurrection in some depth. She was the first scholar to compile a detailed list of those who are known to have been ‘implicated’ in the rebellion, and among the seventy-five names which she amassed were those of fourteen priests.Footnote 14 Rather oddly, Rose-Troup omitted to include the ill-fated Robert Welsh in her list, despite the fact that she had already provided a detailed account of his execution elsewhere.Footnote 15 More oddly still, she also omitted to include Simon Moreton, the vicar of Poundstock, in Cornwall – even though it was Rose-Troup's own shrewd detective work which had led her to conclude that this particular cleric had probably died during the rebellion too.Footnote 16

Rose-Troup had first been put on Moreton's trail by a scathing loyalist reference to ‘the vecare of pomodstoke’, made in a ballad celebrating the rebels’ defeat which was printed in 1549.Footnote 17 Having discovered that the vicar of Poundstock had been regarded at the time as a notorious rebel, Rose-Troup next turned to a manuscript source which was to prove invaluable to her during the course of her research – and which will also be of central importance to the present paper. This was the episcopal register of Bishop John Veysey: a weighty volume which records the admission of hundreds of clergymen to benefices in the diocese of Exeter during Veysey's long episcopate (which extended from 1519 to 1551).Footnote 18 With this volume before her, Rose-Troup was able to discover, first, that one ‘Simon Moorton’ had been admitted to the living of Poundstock in 1534, and, second, that a new incumbent had been admitted to the same parish in January 1550, in the wake of Moreton's death.Footnote 19 It seemed a fair assumption that Moreton was the ‘rebel’ cleric who had been referred to in the ballad, therefore, and that he had died at some point during the rebellion: perhaps on the field of battle, perhaps on a hastily-erected gallows.

Working her way through Veysey's register, Rose-Troup spotted several more intriguing pieces of evidence. First, she noted that another priest whom she knew to have been implicated in the rebellion – Richard Benet, the vicar of St Veep, in Cornwall – had been replaced, like Moreton, by a new incumbent within a few months of the uprising's having been suppressed.Footnote 20 It seemed likely that Benet had perished either during or soon after the commotion, therefore. Second, and more ominous still, she noted that it was specifically stated in the register that a new incumbent had been admitted to another Cornish parish, that of St Cleer, in March 1550 ‘p[e]r attinctura[m] ult[imi] incumbent[tis]’, that is to say, ‘upon the attainder of the previous incumbent’.Footnote 21 To be ‘attainted’ was to be sentenced to death for felony or treason, as a number of rebels had been in 1549, so it seemed almost certain that Robert Royse – whom the register showed to have been admitted to St Cleer in 1547 – had been executed in the wake of the rebellion.Footnote 22 Nor did this exhaust the potential utility of Veysey's register, Rose-Troup realised, for – as well as recording the appointment of new incumbents to the benefices previously known to have been held by the ‘rebels’ Moreton and Benet and by the attainted man presumed to be Royse – the register also recorded the appointment of new incumbents to a number of other benefices in the aftermath of the rebellion: benefices whose previous incumbents might also be suspected to have been slain in 1549, even if there was no hard evidence to prove it. The likelihood of any of these men having been fervent evangelicals who had been killed by the rebels themselves was minimal, Rose-Troup evidently saw, as loyalist polemicists would undoubtedly have rushed to capitalise on any such killings, had they occurred.Footnote 23 At the end of her ‘list of insurgents’, Rose-Troup therefore listed nine parishes which had ‘had new incumbents instituted shortly after the insurrection’, and added that ‘some of … [these men's] predecessors may have been rebels’.Footnote 24

Nowhere did Rose-Troup state precisely how many priests she believed to have been slain in 1549, but at various points in her text she named six such individuals altogether (see Table 1). Four of these were men whom we have already met: Welsh, Moreton, Benet and Royse. The other two – ‘Roger Barret’ and ‘Jo[hn] Tompson' – are clerics whose benefices, if they had any, are unknown and who are both said to have been executed during the rebellion in John Foxe's Actes and monuments, published in 1570.Footnote 25 As a result of her diligent work in the archives, Rose-Troup had managed to recover more information about the priests who had been killed during the rising than anyone who had gone before her – and, in the process, to assemble a body of knowledge which would continue to be repeated, regurgitated and, occasionally, distorted by scholars for decades to come. Nor was it to be long before another historian would follow in her footsteps to the diocesan registry in Exeter.

Table 1. Priests identified as killed in the Western Rising in Rose-Troup, The western rebellion of 1549 (1913)

* ms Rawlinson, C 792, fos 13r–v; Hooker, ‘The description of the citie of Excester’, 1026; DHC, Chanter 14, fo.133v.

† Anon., ‘Ballad on the defeat of the Devon and Cornwall rebels’; DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 134v.

‡ J. Foxe, The first volume of the ecclesiastical history contayning the actes and monumentes of thynges passed in every kynges tyme in this realme, London 1570 (RSTC 11223), 1496; DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 134v.

§ DHC, Chanter 14, fos 123v, 135r.

** Foxe, Actes and monumentes, 1496.

†† Ibid.

Charles Henderson was appointed as a lecturer at University College, Exeter, during the 1920s, and spent much of his tragically short life carrying out intensive research into the ecclesiastical history of Cornwall.Footnote 26 Henderson compiled voluminous notes from the bishops’ registers kept at Exeter Cathedral, and from legal records held at the Public Record Office (now The National Archives) and after his death, in 1933, these notes were deposited at the Courtney Library in Truro.Footnote 27 Here, they were heavily drawn upon by Henderson's friend, A. L. Rowse, as he researched his own monograph Tudor Cornwall, first published in 1941, and reprinted many times since: the book which, after Rose-Troup's, has had the greatest impact on how we see the Western Rising today.Footnote 28

Rowse devoted an entire chapter of his book to the rebellion and this chapter, in its turn, included a short section discussing the fate of ‘rebel priests’: a section which was partly based on Henderson's original research.Footnote 29 ‘Priests who had taken a forward part in the rebellion were specially singled out for punishment’, Rowse began. He had already described the notorious execution of Robert Welsh, and now went on to add – here referring to a recent discovery of his own in the PRO – that ‘we [also] know that the curate of Pillaton [in Cornwall] was hanged by Russell's orders’.Footnote 30 Next, Rowse alluded to three more of the priests whom Rose-Troup had already identified as probably slain in 1549: Moreton, Royse and Benet.Footnote 31 Rowse then moved on to discuss the case of William Alsa, a priest whom Rose-Troup had identified, first, as having been implicated in the rising and, second, as having been the vicar of Gulval, in West Cornwall, but about whose ultimate fate she had apparently remained ignorant.Footnote 32 While trawling though the bishop's register, Henderson had discovered that a new incumbent had been admitted to Gulval, too, in the immediate aftermath of the rising, so Rowse now added Alsa to the roll-call of slain or executed clerics.Footnote 33

So far, Rowse had alluded to each of the four slain priests who had been discussed in detail by Rose-Troup, as well as adding two more of his own to the overall tally: Alsa and the unnamed ‘curate of Pillaton’. He now moved on to remark that ‘in the bishop's register, we find that the vicar of St Keverne was [also] attainted’.Footnote 34 Rose-Troup, too, had noted this entry in Veysey's register, but had assumed that the previously attainted incumbent to whom it referred had been Martin Geffrey: the ‘priest’ of St Keverne who had taken part in the brief insurrection in the far West of Cornwall which took place a year before the Western Rebellion proper, in April 1548, and who had been executed three months later.Footnote 35 Rowse, on the other hand, gave his readers to understand that the ‘attainted’ incumbent of St Keverne was another casualty of 1549. Rowse now concluded his discussion of Veysey's register – and of what it reveals about the fate of local priests – in just the same way as Rose-Troup had concluded her own discussion of the same subject a generation before, observing that ‘a few of the other livings’ where new appointments were recorded in the register in late 1549 and in 1550 ‘may [also] have been … forfeited by rebel priests’.Footnote 36

On this particular question, then, Rowse and Rose-Troup effectively spoke with a single voice, but, on the question of the total number of priests who may be assumed to have been slain in 1549, there was a significant discrepancy between them. For whereas Rose-Troup had identified a total of six such unfortunates, Rowse had identified no fewer than thirteen (see Table 2). In part, this discrepancy arose because Rowse had discovered new evidence – about William Alsa and the ‘curate of Pillaton’ – and because he and Rose-Troup had ascribed the death of the attainted incumbent of St Keverne to different years. The chief reason for the two scholars having arrived at such different totals, however, was the fact that they had read a brief passage in Foxe's near-contemporary Actes and monuments – which names eight priests who had been involved in the rebellion – in quite different ways: Rose-Troup having interpreted it to mean that only two of the priests in question were executed, Rowse, on the other hand, having understood it to mean that all eight of them were.Footnote 37 Thus was engendered the basic confusion over numbers which would continue to dog academic discussion of this subject from 1941 right up to the present day.

Table 2. Priests identified as killed in the rising in Rowse, Tudor Cornwall (1941)

* Foxe, Actes and monumentes, 1496.

† Ibid.

‡ Ibid; DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 133v

§ Foxe, Actes and monumentes, 1496.

** Ibid.

†† TNA, C1/1369/19.

‡‡ DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 134v.

Matters were further complicated by the fact that, while both Rose-Troup and Rowse had provided brief discussions of the individual priests whom they believed to have been killed, neither of them had totted up the total number of slain clerics whom they had referred to at various points in their respective texts. This meant that the many later historians who based their own accounts of clerical fatalities during the rebellion on the original research carried out by Rose-Troup and Rowse were left to add up those figures for themselves, with predictably divergent results. In 1974, for example, David Loades – clearly following Rose-Troup – wrote that ‘one or two clergy, caught flagrante delicto, were hanged on the spot … but … there were no extensive judicial proceedings’.Footnote 38 Three years later, on the other hand, Julian Cornwall – clearly following Rowse – claimed that ‘eight [priests] … were executed … and there could well have been more’.Footnote 39 Several similarly contradictory statements on the same subject could be cited.Footnote 40

Meanwhile, unnoticed by most of those who wrote about the rising during the late 1960s and early 1970s, another historian had entered the lists. In 1963 David Pill submitted his MA dissertation on ‘The diocese of Exeter under Bishop Veysey’: a dissertation which would in time nudge the ongoing scholarly conversation about the fate of ‘rebel’ clergymen in a very different direction. Pill's account of the priests who had ‘suffered at the hands of the executioner’ was largely based on that of Rowse, so it is no surprise to find that the total number of known clerical fatalities referred to in his discussion – eleven – was nearer to the thirteen referred to by Rowse than to the six referred to by Rose-Troup.Footnote 41 What was entirely novel about Pill's argument, however, was the spin which he put on these figures. For, whereas previous writers had implied that the fact that somewhere between six and thirteen priests could be shown to have been killed during the rebellion demonstrated the strength of local clerical resistance to the Edwardian reformation, Pill argued that it demonstrated just the opposite. ‘Considering that there were over 520 parishes in the diocese’, he observed at one point, ‘surprisingly few … [parish priests] took any active part in the [insurrection]’.Footnote 42 In a similar vein, Pill emphasised the fact that ‘only two parish priests’ are specifically mentioned in Veysey's register as having been attainted after the rising, and remarked that ‘while some 1.6% of the population of the diocese lost their lives in defence of the old rites … few of these were priests’.Footnote 43

Pill's dissertation was never published, and was not cited in Youings's article of 1979. Nevertheless, the two scholars had, for a while, been based at the same university, so it seems at least possible that it was Pill's research which had inspired Youings to launch her own, still more forceful, attack on the orthodox view of the rebellion as a priestly protest. Youings began her discussion of this subject by revisiting Rose-Troup's comments about the institutions recorded in Veysey's register, and by declaring that – far from suggesting that appreciable numbers of clergymen had been killed or otherwise displaced from their benefices as a consequence of the insurrection – Rose-Troup's findings showed the opposite. ‘Rose-Troup … searched the diocesan records for instances of institutions to benefices in 1549–50’, Youings wrote, ‘and found very few.’ It was ‘only at St Cleer’, she went on, that Rose-Troup found ‘any real evidence’ in the register ‘of a connection with the rebellion’.Footnote 44 This being the case, Youings observed, ‘one is tempted to conclude … that contemporary reports of the large number of priests involved were grossly exaggerated’.Footnote 45 It was simply not credible to suggest that ‘rebel priests’ had returned to their parishes after the insurrection was over ‘and carried on … unharmed’, Youings concluded, as she brought her own discussion of this subject to an emphatic close, ‘for surely Russell would have dealt sternly with any priests known to have played a prominent part in the rebellion, and if so Hooker, and posterity would have known about them’.Footnote 46

One might well rebut the final part of this argument by observing that Hooker wrote his account of the rebellion for his own reasons, rather than out of any disinterested desire to transmit as detailed as possible a picture of the rising to posterity, so there was no particular reason for him to enumerate the execution of local priests. Nevertheless, Youings's comments have proved influential: helping to inspire Greenwood's work and encouraging several other scholars to suspect that previous estimates of the number of priests slain during the rising had been overblown. In her biography of Edward vi, published in 1999, for example, Jennifer Loach wrote that, while ‘eight priests’ had been ‘condemned [to death]’ in the West in 1549, ‘it seems improbable that all of these sentences were carried out’.Footnote 47 To prove her point, Loach – here, clearly following Youings – observed that ‘Rose-Troup found no evidence for the rapid change-over of parochial clergy … that one would have expected had the executions taken place’.Footnote 48 Youings's intervention may thus be said to have added yet another layer of complexity to the ongoing debate about the true extent of clerical fatalities during the rising: a debate in which there had already been almost as many different opinions expressed as there were scholarly participants involved.

We will never know, of course, precisely how many priests were killed in the South-West in 1549; the surviving sources are simply too scant to allow such a calculation to be made. Nevertheless, it does not seem too optimistic to suggest that – by carefully re-considering the primary evidence which does survive – we may yet arrive at an accurate picture of what a minimum figure for clerical casualties during the course of the Western Rising might reasonably be said to be – and this is what the second part of this paper sets out to do.

II

The first step in the investigation must surely be to re-visit the near-contemporary evidence of the Protestant martyrologist, John Foxe, because it was the sharply differing interpretations put upon his words by Rose-Troup and Rowse which caused them to come to quite different conclusions about the total number of priests who can be shown to have been slain in 1549. So what, precisely, did Foxe have to say upon the matter? Writing twenty years after the rebellion – which he had not witnessed himself, but about which he was evidently well-informed – Foxe believed that priests had played a central role in the disturbances, and he went out of his way to emphasise this point to his readers. Yet the crucial piece of evidence is that which appears in Foxe's account of the rebel leadership, where he declared that:

of Priestes, which were principall sturrers, and some of them Governours of the [rebel] campes and after executed, were to the number of VIII, whose names were Rob. Bochim, John Tompson, Rog. Barret, John Wolcoke, Will. Alsa, James Mourton, Iohn Barrow, [and] Rich. Benet, besides a multitude of other Popish Priestes.Footnote 49

As will immediately be evident to the reader, Foxe's words are highly ambiguous. Does he mean that all eight of the priests whom he describes as ‘principall sturrers’ of the rising were ‘after[wards] executed’, or does he instead mean that only those specific priests who had served as ‘Governours of the campes’ met that bloody end? Rowse took the former view. But Rose-Troup – who had noted that, a little later on in his text, Foxe specifically stated that ‘[John] Tempson and [John] Barret, two Preistes’ were executed, and who also knew, from another source, that both Tompson and Barret had, indeed, served as ‘governors’ of the rebel camps – took the latter view, assuming that Foxe meant that only Tompson and Barret had been killed.Footnote 50 Which historian, if either, was right?

It is tempting to suggest that it is Rose-Troup's view – what we might perhaps term ‘the minimalist’ view – which best reflects the meaning of Foxe's tortuous prose. But in point of fact it is Rowse's view – the ‘maximalist’ view – which seems most likely to be correct, for it is supported by several other pieces of evidence. Entries in Veysey's register strongly suggest that two more of the priests to whom Foxe refers – Alsa and Benet – were indeed killed in 1549, while a recently-discovered manuscript proves, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that a third of the priests whom Foxe names, John Wolcoke, was also hanged by loyalists in the immediate aftermath of the insurrection. If five of the eight priests whom Foxe mentions in the disputed passage can be shown, from independent evidence, to have been slain in 1549, then it is surely more sensible to assume that that passage should be interpreted to mean that all eight of these men had been killed, rather than that just two of them had.Footnote 51

When viewed under the microscope, therefore, Foxe's testimony tends to suggest that more priests were slain in 1549 than some previous scholars have claimed – but of course Foxe's account, first published in 1570, cannot be relied on for a full picture of clerical fatalities during the Western Rising. What do sources written at the time reveal about the way that Edward's government treated ‘rebel priests’? Perhaps the first point to emphasise here is that, even before the rising began, the regime had made it crystal clear that it was prepared to act with extreme prejudice against conservative clerics who were suspected of stirring up dissent among their flocks. As early as July 1548 a London man had given the following account in his private chronicle of the execution of Martin Geffrey, the priest from St Keverne who had been apprehended during the short-lived Cornish commotion of earlier that year: ‘a priest was drawen from the Towre of London into Smythfield, and their hanged, headed and quartered … which was one of the causes of a commotion in Cornewall’.Footnote 52 It is clear, from these words, that the chronicler believed Geffrey to have played a key role in stirring up the trouble in the first place. Obviously, he may only have arrived at this opinion as a result of the regime's own public pronouncements about Geffrey's guilt, but the chronicler's words – and the Crown's harsh actions – make it clear that an atmosphere in which priests could be both blamed and brutally punished for instigating popular disturbances was already beginning to form.

It is striking that, from the moment that they were informed of the major rebellion in the West during the following year, Protector Somerset and his colleagues on the Privy Council laid the blame for the rising squarely at the door of conservative priests.Footnote 53 And the outbreak of further disturbances in Oxfordshire soon afterwards – disturbances in which a number of priests are definitely known to have been involved – can only have confirmed the councillors in the belief that the widespread popular unrest which they were then facing across the south and west of the kingdom was, in large part, clerically inspired.Footnote 54

The council decided that Lord Grey of Wilton – a hardened soldier, who was even then preparing to set off into the West Country at the head of some 1,500 troops to reinforce Russell – should be diverted to deal with the new disturbances.Footnote 55 Grey's treatment of the Oxfordshire rebellion was ‘swift and uncompromising’.Footnote 56 The rebels were crushed, with ‘some slain, [and] some taken’, and exemplary punishments followed, as Grey took advantage of recent proclamations directing that those who participated in unlawful assemblies should be proceeded against according to martial law.Footnote 57 On 19 July Grey ordered the local gentry governors to execute a dozen of the captured rebels – including, significantly, four priests – at various places in Oxfordshire, and gave specific instruction that the vicar of Chipping Norton should be hanged from the steeple of his own church.Footnote 58 (In this, Grey may well have been following the blood-thirsty example of Henry viii, who in 1536 had personally ordered that monks found to have ‘abetted’ the conservative religious demonstration known as the Pilgrimage of Grace should ‘be hanged upon long pieces of timber … out of the steeple’ of their monasteries.Footnote 59) Henry Joyes, the vicar of Chipping Norton, was duly executed soon afterwards, as was at least one other local cleric.Footnote 60 Grey's actions had set a grim precedent – and within days he and the troops who had crushed the Oxfordshire rebels were on their way to join Lord Russell's forces in Devon.

As Grey hastened westwards, damning new evidence linking priests with the insurrection in Devon and Cornwall was about to emerge. In late July the Western rebels – who were then besieging Exeter – composed a fresh list of ‘articles’, or demands, and sent them up to London. Among these articles was one which not only demanded that two of Exeter's cathedral canons – who had been imprisoned in the Tower for their conservative religious views – should be released, but which also stipulated that the king himself should provide these men with ‘certain livyinges’ in the West Country, so that they might ‘preache amonges us our Catholycke fayth’.Footnote 61 It is easy to imagine the privy councillors grinding their teeth in fury as they read these defiant words, which plainly demonstrated the inspiration which the protestors had drawn from the example of the incarcerated canons. Nor was this all, for the new set of articles also supplied irrefutable proof that priests were playing an active role in the rebellion itself. The document was signed by a number of the leading protesters, including four men who proudly, if unwisely, described themselves as ‘the … Governours of the [rebel] Campes’ – and among these last were ‘John Tompson Pryeste’ and ‘Roger Barret Prieste’.Footnote 62

We have met Tompson and Barret before, of course, in the writings of John Foxe – and it seems highly probable that Foxe owed his specific knowledge of the fact that ‘some’ of the priests involved in the rebellion had been ‘Governors of the camps’ to his own perusal of the rebels’ articles. It would have been easy for Foxe to have got his hands on these during the 1560s, for they had been printed in London in 1549 alongside a copy of a letter from an anonymous Devon gentleman serving in Lord Russell's forces who signed himself only as ‘R. L.’.Footnote 63 Both the letter and the original copy of the articles had been sent up to London from Devon on 27 July. The decision had then been taken by someone in authority to publish the two documents together, evidently for propagandist purposes, under the helpfully descriptive title of A copye of a letter contayning … the articles … of the Devonshyre & Cornyshe rebelles. We may presume that this pamphlet was primarily aimed at godly readers in London: many of whom, it may well have been hoped, would not only be shocked by the rebels’ articles, but would also be instructed in the appropriate response to them by R. L.’s furious commentary on the insurgents’ activities. From the point of view of the present article, however, the most significant point about R. L.'s letter is the violent antipathy which it breathes towards priests.

R. L. made it clear, from the very outset, that he blamed clerics just as much as the rebels’ lay leaders for causing the stirs in the first place. In a vivid passage, in which he described how the rebels had argued over precisely which demands should be included in their articles, R. L. next observed that ‘the priestes, they harped all upon a playne songe of Rome’: the word ‘all’ in this passage plainly giving the reader to understand that there were many priests in the rebels’ ranks. R. L. then turned to comment on the Crown's recent suppression of other risings elsewhere, and praised the council for having tempered justice with mercy when it came to punishing the ordinary ‘offendours’. Nevertheless, he went on, ‘to say my mynde … yf the Kynges sworde lighte[d] shorte upon any [during the suppression of these stirs], it was upon … ranke Popish priestes, repynyng against the kynges holsome doctrine’. Having made it crystal clear that he believed that ‘rebel’ priests had got away far too lightly in the wake of the other risings, R. L. finally went on to declare that, if martial law were imposed ‘in every shire’, the current disturbances would swiftly be brought to an end.Footnote 64

R. L.'s letter provides us with one of the few glimpses we have of attitudes towards priests among the West Country gentlemen who had come in to join Lord Russell in East Devon in July 1549. His lapidary words make it clear that, even before Russell was joined by Grey and his men – who had shown no compunction about making a brutal example of rebel clerics in Oxfordshire – there had already been some in Russell's camp who had been advocating similarly radical measures. Nor is R. L.'s letter significant only for what it tells us about his own attitudes, for once the letter and the articles – the first emphasising the crucial role played by priests in the rebel camps, the second demonstrating that several individual priests were acting as ‘governours’ of those camps – had been published, they became one of the chief sources of information upon which other loyalists drew as they developed their own mental picture of the rising.

R. L.’s letter was despatched a day or two before the first major clash occurred between Lord Russell's forces and the Western rebels. Between 27 July and 5 August, however, a series of desperate battles took place in the East Devon countryside, as Russell – his strength now swollen by Grey's forces, and by bands of foreign mercenary soldiers who had been sent down to his aid – pushed slowly westwards towards the besieged city of Exeter. Several thousand protestors were killed in brutal engagements fought at Fenny Bridges, Clyst St Mary and Clyst Heath, and on 5 August the surviving besiegers finally abandoned their camps before Exeter and withdrew to the west, thus enabling Russell to enter the city in triumph on the following day.Footnote 65 The victors swiftly set about the congenial task of punishing the vanquished, and a list of expenses which was compiled by the mayor of Exeter soon afterwards shows that several sets of ‘gallows’ were constructed at this time.Footnote 66 It was almost certainly during this same period that Robert Welsh met his celebrated end. Writing many years later, John Hooker recalled that while Russell was in Exeter, ‘he did greate executions uppon the rebells, [and] namelie uppon a Prieste named Welsh … viccar … of St Thomas neere … Excester who had byn a chiefe Captaine … in this rebellion’.Footnote 67

Hooker described Welsh's last moments in vivid detail, recording that:

the execution of this man was committed to … [a local loyalist] who, being nothing slacke to follow his commission, caused a paire of gallowes to be made, and to be set up upon the top of the tower of the … Vicar's parish church … And, all things being readie … the Vicar was brought to the place, and, by a rope about his middle, drawne up to the top of the Tower, and there in chains hanged in his popish apparell, and had a holie water bucket and sprinkle … a paire of [rosary] beads and such like popish trash hanged about him; and there he … remained a long time.Footnote 68

Why did Hooker choose to include such a detailed account of Welsh's death in his narrative? Possibly it was because he had witnessed the execution himself; possibly it was because Welsh was an Exeter man with whom he had been well acquainted before the rebellion began; possibly it was because – as a stout Protestant – Hooker wished to provide his readers with an especially vivid illustration of the fate which awaited recalcitrant ‘papists’. Possibly it was for all three of these reasons. But it was surely not, as Youings implies, because Welsh was the only priest whom Hooker knew to have been killed by Russell's forces. That Welsh was, on the contrary, just one of many clerics who had lost their lives during the rising is made manifest by a hitherto unpublished letter sent from Exeter on 16 August by John Fry, another local gentleman who was serving in Lord Russell's army. In this missive, Fry began by telling his correspondent of the many captives whom Russell had taken during the recent fighting and then went on to add that: ‘The most p[ar]t of them, & of such other as were taken prisoners have confessyd that the prestes have ben the great occasion of thys comocion; further in every of the said fyghtes ther were dyvers prystes in the fyld fyghtng ayenst us, & some of them slayne at every fyghte.’Footnote 69 Fry's words not only provide further evidence of the fact that local loyalists believed priests to be playing a crucial role in the rebel armies, therefore, they also make it hard to doubt that a significant number of ‘rebel priests’ had already been killed – even though the insurrection was by no means yet wholly suppressed.

Independent evidence survives to show that further killings of priests occurred over the succeeding fortnight, moreover, as Russell's forces first pursued the insurrectionists to Sampford Courtenay, where the rebellion had originally begun, and then – after having crushed the rebels in a last, bloody battle fought there – hunted down the final stragglers. Martial law was now declared across the whole region – just as ‘R. L.’ had urged that it should be a couple of weeks before – and there can be no doubt that, with the normal legal processes suspended, further clerics suffered summary execution at the hands of vengeful loyalists. A subsequent chancery suit, for example, reveals that, on 14 August, a group of North Devon men were ordered to arrest the parson of Bittadon and the curate of Pilton, both of whom were accused of being rebels. The parson was fortunate enough to escape, but the curate – in all likelihood, one Richard Wollysworthye – was captured, and was subsequently hanged in chains at Pilton ‘to the example of all others’, it was later testified, by virtue of a warrant from Lord Russell ‘& by the marcyall lawes’.Footnote 70 (It is worth noting here that Rowse, the first scholar to uncover the documents relating to this case, mis-transcribed ‘Pilton’ for ‘Pillaton’, thus causing subsequent scholars to believe that this particular execution had taken place in Cornwall, rather than in North Devon.Footnote 71)

Recent archival discoveries have revealed, moreover, not only that John Browne, the parson of Langtree – once again, in North Devon – was killed ‘at … [the] commocyon’, but that, ten days after the hanging of the curate of Pilton, a double execution of priests took place at St Keverne in Cornwall: the parish in which the Cornish commotion of 1548 – usually seen as the precursor to the Western Rising – had begun.Footnote 72 On 24 August 1549 Robert Raffe, vicar of St Keverne, and John Wulcoke, vicar of the nearby parish of Manaccan, were hanged by local loyalists as ‘rebellyers’ and their goods were confiscated by the Crown.Footnote 73 This discovery at last enables us to establish the identity of the ‘John Wolcoke’ who was named by Foxe as one of the leading rebel priests – and to verify that Wolcoke was, indeed, executed. It also confirms that Rowse was right to assume that the later reference in Veysey's register to the vicar of St Keverne having been ‘attainted’ was an allusion not to Martin Geffrey, executed in the wake of the commotion of 1548, but to a second priest of St Keverne – in point of fact, Robert Raffe, the incumbent – who had been executed in the wake of the much bigger rebellion of 1549.Footnote 74

Finally, we should note the survival of an intriguing piece of evidence which serves both to confirm the fact of Simon Moreton's execution, first posited by Rose-Troup in 1913, and to indicate that rebel priests continued to suffer public execution in the West until as late as October 1549. Writing in 1753 – and almost certainly drawing on the parish registers of Stratton, now sadly lost – a local antiquary observed that ‘One Simon Mourton, vicar of … Poundstock, was hanged at the market house of Stratton for high treason’ in the aftermath of the rebellion. ‘He was hanged upon the 13th day of October 1549’, the antiquary went on, ‘and buried the 18th day of the same month’, adding, piquantly, that ‘the cross or pedestal whereon he hung is wanting, but the stone in which it was fixed is still to be seen’.Footnote 75 By combining all of this new evidence with that which was gathered by Rose-Troup and Rowse, it is now possible to identify a grand total of fourteen priests who we can be fairly confident were killed during the Western Rising (see Table 3).

Table 3. Priests identified as killed in the rising in the present article.

* See table 1, and Pool, ‘Cornish parishes in 1753’, 502.

† TNA, E 199/6, item 52.

‡ See n. 70 above, and TNA, E 344/19/15, fo. 10r.

§ TNA, E 199/6, item 52; DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 134v.

** TNA, C1 1387/14; DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 133r.

III

As this paper moves towards its conclusion, it is possible that some readers may be feeling a little underwhelmed. Previous scholars of the Western Rising had put the total number of known clerical fatalities during the insurrection at somewhere between six and thirteen; now a careful reconsideration of the evidence has demonstrate that the minimum figure should probably be raised to fourteen. ‘Big deal’, an astringent reader might well be tempted to observe. Yet this advance in historical knowledge – incremental as it may be – is a genuinely important one. The fact that at least fourteen priests can be shown to have been slain during the insurrection makes it clear that Youings – and the other historians who have followed in her footsteps – was wrong to suggest that clerical involvement in the rising had been ‘grossly exaggerated’. And while fourteen dead priests may not sound all that great a number in the context of the terrible mass slaughters of the twentieth century, it is important not to use phrases like ‘only fourteen dead’, for every summary execution is a human tragedy in itself.Footnote 76 Nor should we forget the enormous impact which the public execution of even a handful of priests – their bodies left hanging in chains from gallows, church towers and market crosses across the region – would have had upon the local population, and, of course, upon the clerical population in particular. We need hardly be surprised that there were no more risings in defence of traditional religious practice in the West for almost a century after 1549.

It is vital to stress, moreover, that the figure for the total number of clerical fatalities which has been arrived at here is a minimum, rather than a maximum, one. John Fry's highly revealing letter – a letter which specifically refers to rebel priests having been slain in each of the bloody engagements which took place between Russell and the insurrectionists – strongly suggests that the true number of dead priests was higher still. And, indeed, this story possesses a final grim twist, for if we return to Veysey's register for one last time, and subject it to even closer scrutiny than Rose-Troup afforded it in 1913, we begin to see that she was almost certainly right to suspect that a significant number of the presentations which were made to local parishes after September 1549 had been occasioned by the killing or removal of the previous incumbents during the rebellion.

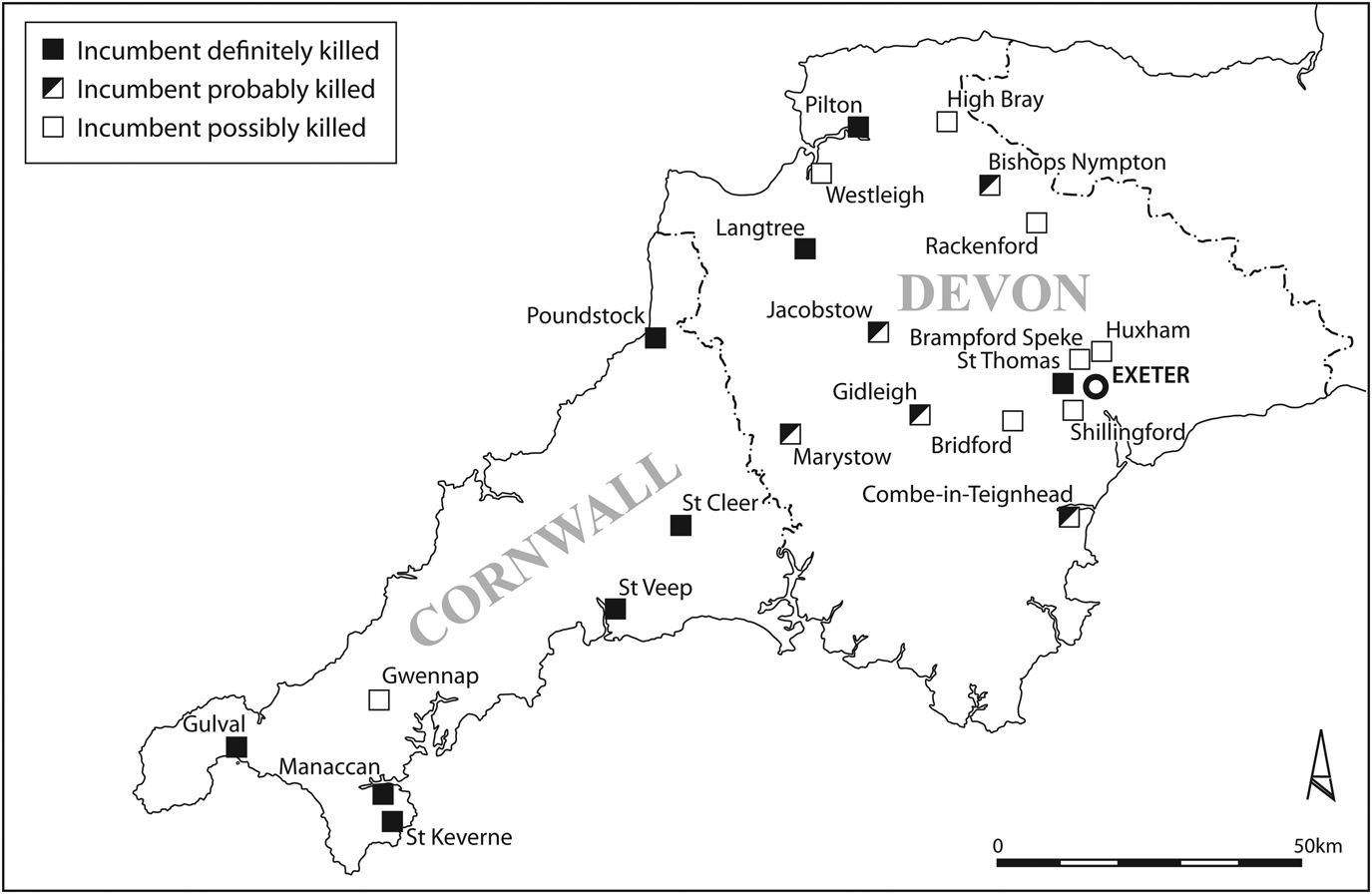

It is true that the register makes only a couple of direct references to deaths which had occurred as a result of the insurrection: those of the vicars of St Keverne and St Cleer. Once we start to read between the lines, however, a far more sinister picture begins to emerge. During the seven-month period between 1 September 1549 and 28 March 1550 the register refers to the appointment of new incumbents at Manaccan, St Thomas and Poundstock, for example: all parishes whose priests are definitely known to have been executed. It also refers to the admission of new incumbents at Gulval, Langtree and St Veep: all parishes whose priests are known to have been involved in the rebellion. In each case, the scribe who compiled the register simply noted that the previous incumbent had died, without specifically stating that the vacancy had occurred as the result either of ‘the natural death’ or of the resignation of the previous incumbent – as had almost invariably been the case whenever new admissions had been recorded in the register during the previous quarter century.Footnote 77 It seems probable that these terse allusions to vacancies having arisen ‘per mortem’ were coded references to the fact that the previous incumbents had been killed during the insurrection, therefore. And if this is indeed the case, then the fact that four more Devon parishes – Gidleigh, Jacobstowe, Combe-in-Teignhead and Maristow – were likewise noted to have become vacant ‘through death’ during this same period strongly suggests that their incumbents had also perished during the commotion.Footnote 78

Figure 1. West Country parishes whose incumbents are either known or suspected to have been killed in 1549.

On 15 March 1550 the bishop's scribe made his second explicit reference to the punishment of ‘rebel’ priests when he recorded that the living of St Cleer had become vacant as a result of the ‘attainder’ of the previous incumbent.Footnote 79 Was it mere coincidence that immediately after this entry a new scribe began to compile the register: a scribe who, on 29 March, recorded the admission of a new incumbent to a living which was ‘iam certo modo vacantem’ [i.e. ‘now, in a certain way, vacant’]?Footnote 80 This conveniently neutral formulation had not been used in Veysey's register before, but over the following year, it was to be deployed again – by now having been still further watered down to read just ‘now vacant’ – on no fewer than fifteen separate occasions.Footnote 81 It is tempting to suggest that the new scribe had resorted to this phrase in order to avoid the embarrassment of having to make further repeated references to ‘rebel’ priests in the register – and that the former incumbents of at least some of the parishes whose ‘vacant’ status were thus referred to had also died as a result of their involvement in the commotion.Footnote 82

The register permits us to identify the priests who had previously been appointed to the benefices described as ‘vacant’ by the new scribe, and, of these sixteen men, nine disappear from the historical record after 1549: Richard Harrys of Brampford Speke; Thomas Bosythyow of Gwennap; Walter Southcott of South Brent and Bridford; Walter Bowen of High Bray; George Sherard of Shillingford; Thomas Martyn of Huxham; Edmund Cryspyn of Westleigh; William Tothecott of Rackenford; and Edward Hill of Bishops Nympton.Footnote 83 Were these ‘missing parsons’ all priests who had been slain during the rising? It is unlikely that we will ever know for sure, but if we conclude, first, that the benefices which the original scribe had noted as vacant ‘through death’ before 28 March 1550 were definitely those of men who had died during the commotion, and, second, that the studiedly neutral phraseology which the ‘new’ scribe began to deploy thereafter was, in some cases, intended to cloak a highly inconvenient truth, then the total number of clerical fatalities – or, at the very least, of clerical fatalities and displacements – which can be either demonstrated or strongly suspected to have occurred as a result of the rebellion at once rises to between nineteen and twenty-seven (see Tables 3 and 4). This is a substantial figure by any estimation: a figure which represents somewhere between 3 and 5 per cent of the total number of parochial clergy in Veysey's diocese, and which suggests that the Western Rebellion probably resulted in the deaths of more clerics than any other Tudor rebellion apart from the Pilgrimage of Grace.Footnote 84 It is also a figure which makes it hard to doubt that – whatever some historians may have argued to the contrary – during the blood-soaked summer of 1549 the parochial clergy of Devon and Cornwall had shown a quite remarkable willingness both to fight, and in many cases to die, in defence of their traditional faith.

Table 4. Priests identified as: (a) probably; and (b) possibly killed during the rising on the basis of the way that new clerical presentations to their former benefices were recorded in the bishop's register, 1549–50

* Admitted in 1516: DHC, Chanter 13, register of Bishop Hugh Oldham, 1504–19, fo. 66v.

† Admitted in 1546: DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 119v.

‡ Admitted in 1541: ibid. fo. 104r.

§ Admitted in 1527: ibid. fo. 32v.

** Admitted in 1540: ibid. fo. 101v.

†† Admitted in 1539: ibid. fo. 96r.

‡‡ Admitted in 1516 and 1509 respectively: DHC, Chanter 13, fos 67v–68r, 28.

§§ Admitted in 1539: DHC, Chanter 14, fo. 97r.

*** Admitted in 1528: ibid. fo. 37r.

††† Admitted in 1537: ibid. fo. 88v.

‡‡‡ Admitted in 1542: ibid. fo. 108v.

§§§ Admitted in 1532: ibid. fo. 60r.

**** Admitted in 1548: ibid. fo. 129v. The fact that Hill's benefice was noted by the scribe to have become vacant ‘per mortem’ may be said to raise the likelihood that Hill was killed in the rebellion from ‘possible’ to ‘probable’.