1. Introduction

Most dialects of Norwegian and Swedish are characterized by a binary tonal opposition, Accent 1 versus Accent 2, often referred to as tonal accent in English. One of the unresolved questions concerning their diachrony is the nature of the original melodies from which the contrast developed about a thousand years ago. Since no direct evidence is available, these melodies must be reconstructed from the dialectal variation that can be observed today, combined with what can be regarded as plausible tonal figurations at the outset and subsequent plausible tonal changes, based on the uniformitarian principle (Labov Reference Labov1972:275).

Two competing views can be identified. The prevalent view since the turn of the century has been the hypothesis of Tomas Riad (see, for example, Riad Reference Riad1998, Reference Kristoffersen2000a,b, Reference Riad2003a, Reference Basbøll2005, Reference Hognestad2006, Reference Riad2009), which assumes that the melodies that today characterize central Swedish, including the capital Stockholm, are those most resembling what must have been the original phonetic contrast. For reasons that become clear below, I shall refer to Riad’s hypothesis as Type 2 first. Opposed to this is the view that the melodies that characterize more geographically marginal regions such as Gotland and Skåne in Sweden, and different parts of western and northern Norway, are the more archaic varieties (Hognestad Reference Engstrand and Nyström2002, Reference Hognestad2006, Reference Hognestad2007, Reference Hognestad2008, Reference DiCanio2012; Bye Reference Bye2004, Reference Bye2011; Kristoffersen Reference Bye2004; Iosad Reference Iosad2016). This hypothesis is referred to as Type 1 first.

The tonal accent contrast is strictly associated with primary stress. The contrast arose from what appears to have been a noncontrastive, complementary distribution of pitch accents in early mediaeval North Germanic, based on a distinction between monosyllabic and plurisyllabic words (Oftedal Reference Oftedal1952:55f.). This distribution became potentially surface contrastive due to two changes that took place during the mediaeval era, namely, resolution of disharmonic rhymes through syllabification of sonorants and the development of suffixed definite articles (see section 3 for further details).

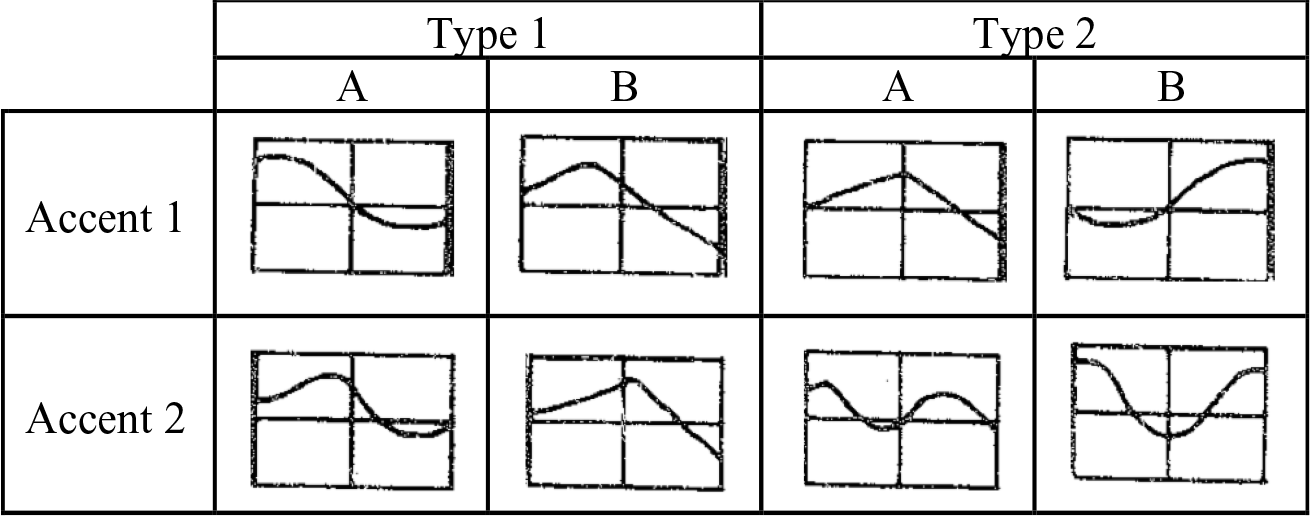

With respect to the phonetic realization of the two accent melodies, two main types can be identified. Based on surveys published by Ernst A. Meyer (Reference Meyer1937, Reference Meyer1954), these types were established by Eva Gårding and collaborators through several publications going back to the 1970s (see, for example, Gårding & Lindblad Reference Gårding and Lindblad1973, Gårding Reference Gårding1977, and Bruce & Gårding Reference Bruce and Gårding1978). Figure 1 shows the F0 contours that characterize the two main types, both subdivided into two subtypes A and B. The vertical line in each small panel represents the division between the stressed syllable and a following unstressed or secondary stressed syllable.

Figure 1. Phonetic realization types (adapted from Bruce & Gårding Reference Bruce and Gårding1978).

The most important difference between the two main types is that Accent 2 has only one peak in Type 1, while it has two in Type 2. The difference between the subtypes is one of timing, in that the (rightmost) peaks occur later in the B-type than in the A-type. This difference in timing also extends across the two main types, in that in the first three subtypes, the (rightmost) Accent 2 peak occurs later than the Accent 1 peak. In the fourth, type 2B, they coincide.

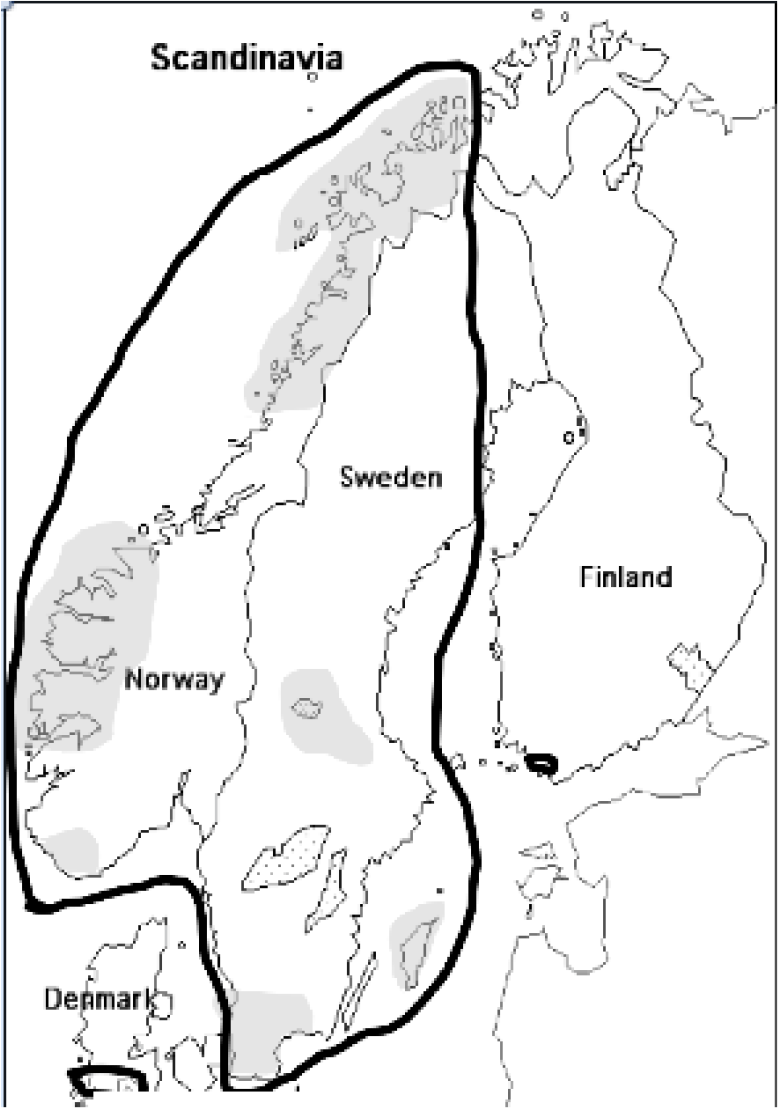

The bold lines in figure 2 show where tonal accents are found in the Scandinavian countries. The main area covers most of Norway and Sweden, while Danish and the Swedish spoken in Finland with a few exceptions lack this feature.Footnote 1 The grey areas on the map show the parts of Sweden and Norway where the Type 1 dialects are spoken. As can be seen, all except one are found along the margins of the larger area where tonal accents are in use. It is the exception, the region in grey in central Sweden, that is the topic of this article. This region constitutes an island of Type 1 surrounded by Type 2 in all directions. Geographically, it is to a considerable extent coextensive with the Dalarna County. The southeastern section forms part of the traditional mining region Bergslagen and is often referred to as Dala-Bergslagen. Dala-Bergslagen is part of the fertile eastern central region of Sweden that also comprises the Uppland region and the capital Stockholm. The upper, northwestern section, often referred to as Dalarna proper, henceforth Dalarna, consists of the two valleys formed by the eastern and western branches of the upper Dala river (Swedish Dalälven). Dalarna is more sparsely populated and dominated by small scale industry, agriculture, forests and lakes, with no major, urban centers. The dialects are counted as some of the most archaic in Scandinavia, especially those spoken around the northern shores and north of the Siljan lake in the East Valley. This area, which today comprises the municipalities Mora, Orsa, and Älvdalen, is traditionally referred to as Ovansiljan, that is, Upper Siljan in English. I continue to use the Swedish term.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of the phonetic realization types.

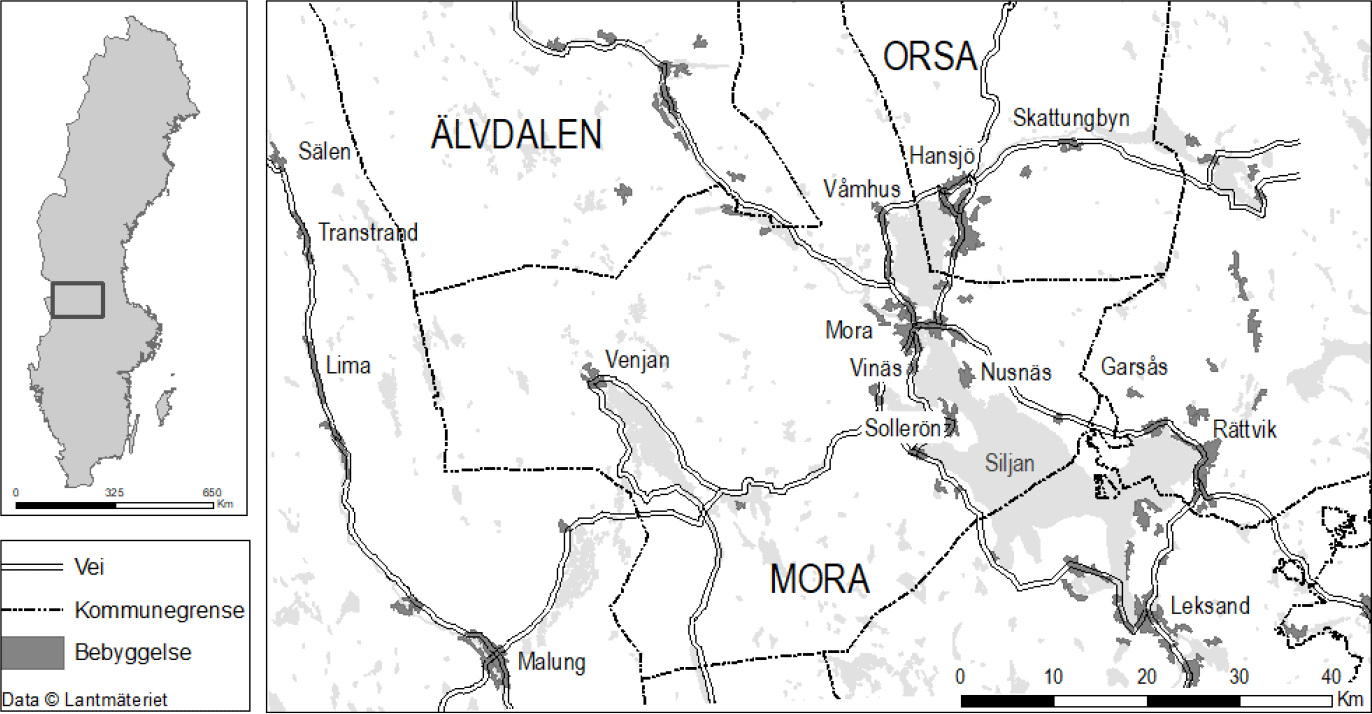

The isogloss delimiting the northernmost Type 1 dialects from the Type 2 dialects in Ovansiljan separates Älvdalen from Orsa and Mora (see figure 3). In the West Valley, the isogloss separates the northernmost Transtrand and Lima municipalities from Malung further south.

Figure 3. Map of Ovansiljan (by Kari Elida Eriksen, University of Bergen).

According to Tomas Riad’s hypothesis concerning the development of the dialect variation depicted in figure 1, subtype 2A represents the best approximation to the original system, from which the other varieties have developed. The areas where Type 1 is found are, in other words, innovating areas, according to this hypothesis. The central point of the present paper is that the Type 1 dialects spoken in the region, except the northernmost communities Älvdalen, Lima, and Transtrand, are unlikely to have developed from a former Type 2 stage, as hypothesized by Riad (Reference Riad1998). On the contrary, I argue that when the available data are put together, a more plausible picture emerges where the southern, Dala-Bergslagen area earlier had a type 1A system, while the northern part until fairly recently lacked the opposition. If this is correct, the accentual contrast has spread northwards as a Type 1 innovation, where the northern dialects in the East Valley are in the process of adopting subtype 1A, while the southern dialects have gradually changed to subtype 1B.

Although one of course cannot know this for sure, I assume that the tonal accent contrast did not arise simultaneously in all the dialects that have the contrast today. Rather it must have developed in a more limited area and spread by diffusion until at some point it came to characterize almost all dialects of Sweden and Norway.

Finally, areas with no tonal contrast are few and far between. In addition to the northernmost areas in both countries, where contact with toneless Finno-Ugric Sás0mi and Finnish may be the cause of the absence, one accentless region in Uppland, Sweden is known from the literature (Riad 2003b). There are also two regions in Norway—one small area in Helgeland on the border between northern Norwegian Type 1 and eastern Norwegian Type 2 areas (Fintoft et al. Reference Bruce and Gårding1978). In addition, toneless dialects are spoken in rural areas surrounding the town of Bergen in western Norway (Jensen Reference Jensen1961, Rundhovde Reference Rundhovde1964:40f., Kristoffersen Reference Iosad2016). To this list the present article adds the village of Våmhus, on the border between Älvdalen and Mora, as can be seen in figure 3, a map of Ovansiljan that shows the locations referred to in the text.

As mentioned above, the dialects spoken in the northern part of the East Valley stand out as some of the most archaic dialects in Sweden. They are in general not understood by speakers from other parts of Sweden, so all dialect speakers are bidialectal between Standard Swedish and the local dialect.

The northernmost Älvdalen variety, by far the best known, now and then attracts popular international attention as “the language of the Vikings.”Footnote 2 However, the dialects spoken in the two municipalities southeast of Älvdalen, Mora, and Orsa, are not very different.Footnote 3 The most important difference is perhaps sociolinguistic. Älvdalen has a very strong language preservation movement, supported by linguists from many parts of Scandinavia and the rest of the world. The corresponding forces in Mora and Orsa are much weaker, and the dialects spoken there do not enjoy the same national and international attention, neither from linguists nor from nonlinguists. Due to this, the varieties spoken south of Älvdalen must be considered moribund, as very few young people today are reported to use the dialect. Instead, they use the regional variety of Standard Swedish.Footnote 4

The rest of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 is a review of the Dalarna part of Ernst A. Meyer’s survey of accent realization in different parts of Sweden in the first decades of the 20th century (Meyer 1937, 1954), and section 3 is a review of the current hypotheses regarding the origin of the tonal accent contrast. In section 4, I introduce the data and methods of analysis. Section 5, which constitutes the main body of the paper, presents the results, starting in the lower parts of Dalarna, south of Ovansiljan, and then going north toward the Type 1/Type2 isogloss between the Mora/Orsa and the Älvdalen municipalities. A discussion of the results follows in section 6, and section 7 concludes.

2. Meyer’s Data from the Early 20th Century and Its Reanalysis

Ernst A. Meyer (1873–1953) can be seen as one of the pioneers within instrumental phonetic fieldwork. By means of an instrument he constructed himself and referred to as Tonhöhenmesser (Meyer 1937:23ff.), he made a series of recordings of speakers of different Swedish dialects, among them a considerable number in Dalarna.Footnote 5 The recordings were made around the time of the First World War. The speakers were all males, most of them born during the final decades of the 19th century. For each speaker, a selection of F0 contours of the test words is reproduced in the book. Meyer then drew stylized contours of the two accents based on the individual F0 tracings. These were collected into a big foldout table at the end of the 1937 monograph and updated in his (1954) part II. The F0 contours in figures 1 and 4 are reproduced from the 1937 table.

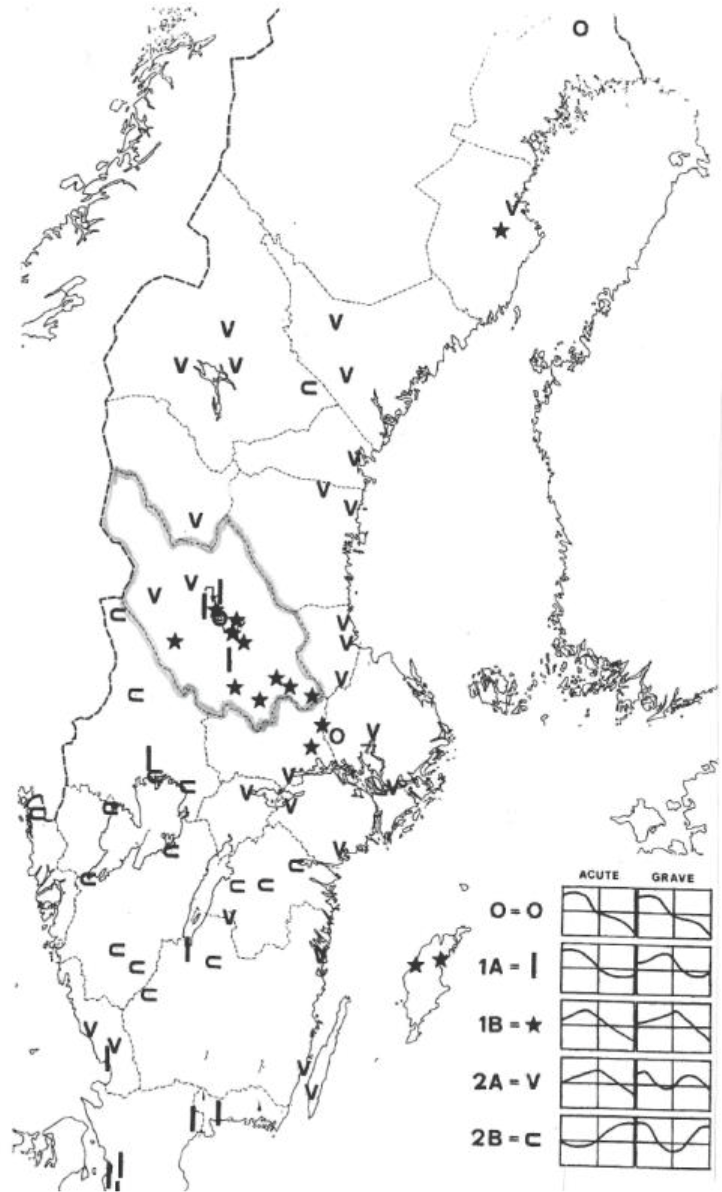

Figure 4. Geographical distribution of accent types in Sweden (from Gårding & Lindblad 1973:48).

Meyer himself identified the two main dialect types and referred to them as having Bergslagen and Svea intonation, which correspond to Type 1 and Type 2 dialects, respectively (1937:231f.).Footnote 6 The terms themselves, along with the A and B subtypes, were, as mentioned above, introduced by Eva Gårding and her colleagues in the 1970s. With respect to Type 1 dialects, they are clearly based on the subdivision Meyer proposed for his Bergslagen type. Based on the stylized Type 1 contours in figures 1 and 4, I classify dialects where the Accent 2 boundary occurs before the syllable boundary as subtype 1A and those where it follows the boundary as subtype 1B.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the accent types across Sweden, based on Meyer’s contours as well as other sources.Footnote 7 The Dalarna County has been delimited with a thick grey line. Each symbol represents a dialect, which in some cases represents more than one speaker. Stars mark subtype 1B dialects and vertical bars dialects belonging to subtype 1A. Among the Type 1 symbols, the B-subtype dominates, but there are three instances of the A-subtype, two of them north of the B-symbols and one further south among them.Footnote 8 The two v-symbols to the northwest represent the subtype 2A Älvdalen dialect in the East Valley and the Transtrand dialect in the West Valley.

An important question is to what extent Meyer’s data are reliable. There can be little doubt that in general, his individual F0 tracings, interspersed within the main text in the 1937 book, can be depended on. However, even if the main difference between the accents emerges clearly when one compares the individual tracings representing each accent, there is variation within each category, in addition to a considerable amount of micro-prosodic noise. One might think that this would make it difficult to determine the exact shape of the averaged contour for each speaker/dialect. However, Meyer is not explicit about how he arrived at these representations, beyond saying that they are typical for each speaker.Footnote 9

Since the timing differences between F0 peaks discussed in this article are small, the question arises whether the categorization into A- and B-subtypes based on Meyer’s idealized contours can be trusted, both with respect to exact timing and to differences between the dialects. In this regard, it is significant that in Dalarna, the two subtypes do not appear at random with respect to geographical distribution. Instead, two out of the three instances of the A-subtype are located in what must be the upper East Valley close to the Type 2 isogloss, while the area to the south with one exception is dominated by the B-subtype.Footnote 10 Meyer (Reference Meyer1937:236) himself is clear about this distribution:

Innerhalb dieses ganzen Gebiets zeigt die Intonation nun aber nicht die gleiche Form, vielmehr gibt sich eine im Ganzen mit bemerkenswerter Stetigkeit von Südosten nach Nordwesten fortschreitende Entwicklung in der tonischen Formung der Akut- wie der Graviswörter zu erkennen.

Within this area the intonation does not manifest itself in the same form. In fact, a continuous development in the tonal shape of the Accent 1 and Accent 2 words can be identified with a remarkable constancy from the southeast towards the northwest.

Another problem with Meyer’s data is that there are two versions of many of his contour pairs, those published in the table at the end of his 1937 book and those in the corresponding table at the end of the 1954 book. The 1954 book appeared posthumously and contains text chapters on the dialects spoken in northern and eastern Sweden, but no further discussion of his Dalarna findings. According to the foreword by the editor, Birger Calleman, the table at the end of the book is based on “… einer unter Dr. Meyers Papieren gefundenen Aufstellung […], mit der Überschrift: Durchsnittsintonationskurven für die verschiedenen schwedischen Sprecher” [… a table found among Dr. Meyer’s papers […] with the title: Averaged intonation contours of the different Swedish speakers] (p. 13).

One example of such lack of correspondence is Malung in the West Valley. In the 1937 table, one speaker is included. The contours show an early Accent 1 peak and the Accent 2 peak just after the syllable boundary. Of the two individual example contours shown on p. 215, both of the infinitive låna ‘to borrow’, the first has the peak at the syllable boundary, the other late in the intervocalic consonant; that is, after the syllable boundary. In the 1954 table, two speakers are included. According to the list of speakers at the end of the table, the first one of these, number 41, is identical with the only Malung speaker represented in the 1937 book. In the 1954 table, his Accent 2 peak is placed at the syllable boundary, not after, as in 1937. The same is true for the dialects of Rättvik and Leksand, in the southern part of the East Valley. Here the Accent 2 peaks are also placed earlier in the 1954 table than in the 1937 table. Since these discrepancies are not commented upon in the 1954 book, it is hard to say why and how Meyer revised his contours. Yet given the 1954 editor’s note cited above, there can be little doubt that the revisions are Meyer’s own, and the most plausible explanation is perhaps that the revisions were based on data not yet analyzed in 1937. I therefore base the analyses that follow on his revised, 1954 contours.

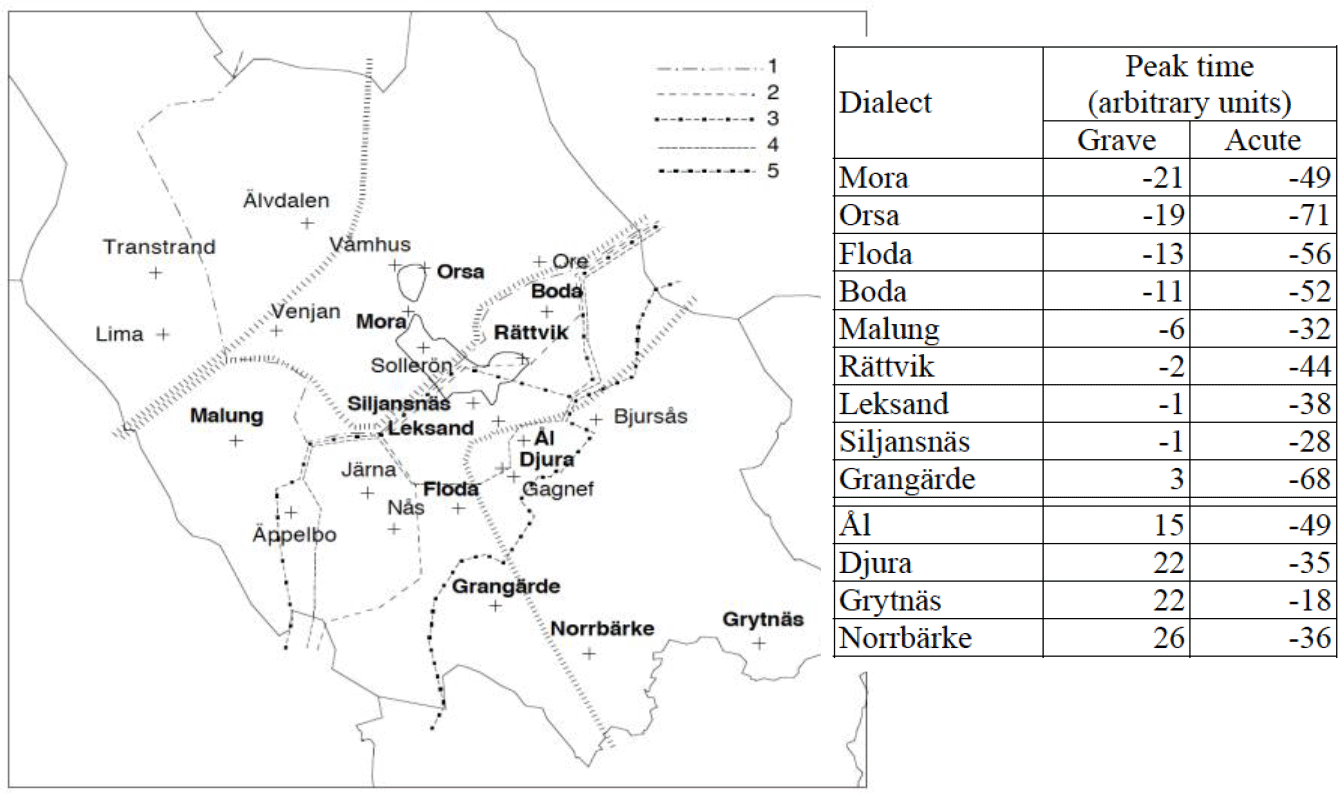

Meyer’s data were reanalyzed by Engstrand & Nyström (Reference Engstrand and Nyström2002). Based on digitized versions of Meyer’s contours from Dalarna, they measured the distance of the Accent 1 and 2 peaks from the syllable boundary. Given the lack of a timescale in Meyer’s representations, the distance was measured in “arbitrary units” (p. 18). The right panel in figure 5 (adapted from Engstrand & Nyström 2002) shows the results for the different dialects. In cases where more than one speaker represented a given dialect, the positions of the peaks were averaged.

Figure 5. Relative timing of accent peaks in Meyer’s idealized accent contours (right panel) with map references (left panel) in boldface.

The analysis of Engstrand & Nyström (Reference Engstrand and Nyström2002), based on the Accent 2 values in the 1954 table, strongly corroborates Meyer’s observation cited above that there exists a gradual development in timing relative to the syllable boundary.Footnote 11 In their own words, “In summary, grave tone-peaks tend to appear later the further south by southeast that we move across the one-peaked dialects on the map” (p. 18).Footnote 12 Based on this, they make the same conjecture as the one the present article is based upon, namely, that the pattern is due to a spreading process from the southeast toward the north and the northwest that manifests itself as an increasing degree of later timing of the Accent 2 peak.

3. The Origin of the Tonal Melodies and the Subsequent Dialect Splits

3.1 The Tonogenesis Hypotheses

Of course, there is no a priori reason to assume that the mechanisms that originally caused the tonal split were the same forces that subsequently drove the dialect splits described in section 3.2. Yet a comprehensive hypothesis that can account for both by invoking the same phonetic driving force can be seen as more ambitious and potentially of greater explanatory power than one where the two are seen as separate and independent processes. In this section, I argue that the Type 1 first hypothesis is comprehensive in the way just mentioned. This wider scope will not settle the issue as to which one of the hypotheses is correct, but as mentioned above, the data presented in this article, in my opinion, support the Type 1 first hypothesis as more comprehensive, covering tonogenesis as well as the dialect splits. In order to contextualize the findings presented in section 5 below, it is therefore necessary to shortly present the two hypotheses.

As already mentioned, Tomas Riad in a series of papers (Riad Reference Riad1998, Reference Kristoffersen2000a,b, Reference Riad2003a, Reference Basbøll2005, Reference Hognestad2006, Reference Riad2009) has argued that the realization pattern closest to the original melodies is that of subtype 2A, with an early and a late peak in focused Accent 2 phrases, and a single peak in Accent 1 (see figure 1 above).Footnote 13 The basic assumption is that the second peak in Accent 2 is the reflex of a tonal marking of Proto-Nordic secondary stress following the primary stress on the (mostly) initial root syllable of a word. Drastic syncopation processes during the pre-Old-Scandinavian stage resulted in all short unstressed syllables being deleted (Haugen Reference Haugen1976:150f.). This latter change again resulted in stress clashes and elimination of secondary stresses immediately following a primary stressed syllable. Crucially, however, the original high tone, according to Riad, must have survived on these destressed syllables, resulting in a double-peaked H*LH contour on plurisyllabic words and a single H*L on monosyllabic words. If this hypothesis is correct, the Type 1 varieties, including the Dala-Bergslagen ones, must have developed from subtype 2A.

In contrast, the Type 1 first hypothesis reconstructs tonogenesis in terms of different timings of an intonational H*L pitch accent in Old Norse: In plurisyllabic words with at least one syllable following the main stress, H* was subject to gradual peak delay, whereas in monosyllabic words, this change was blocked due to lack of space.

Peak delay is a well-known synchronic and seemingly physio-logically based process whereby tonal peaks are often realized later than their phonological affiliation would lead one to expect (Xu Reference Xu1999, Gussenhoven Reference Bye2004:72, 90, Yip Reference Engstrand and Nyström2002:8–10). During the Old Norse period, this process could have led to a perceptually robust pattern of complementary distribution, which became potentially contrastive with the advent of the two changes briefly mentioned in section 1. The first was resolution of disharmonic rhymes in monosyllabic words through schwa epenthesis or sonorant syllabification. The relevant rhymes had a sonorant following an obstruent, as in Old Norse vás0pn ‘weapon’, which in modern Norwegian is pronounced [1ʋoː.pən] or [1ʋoː.pn̩], depending on dialect, and in Standard Swedish [1ʋɑː.pən].Footnote 14 The second was the well-known North Germanic development of suffixed definite articles via cliticization of a formerly morphologically independent determiner. Both these changes resulted in new types of disyllabic words that crucially retained their original monosyllabic accent (Haugen 1976:283f.). As a result of these changes, Accent 1 could now occur in plurisyllabic words that could form minimal pairs with Accent 2 words.

One of the reviewers asks how these new disyllabic words could be exempted from the peak delay rule, since on this view, the language must have had an obligatory rule inducing delayed realization of the H* in plurisyllabic words. Given its status as obligatory, one would expect that newly introduced plurisyllabic words would also be subject to the rule. Here, however, one must take into consideration that probably neither of the two changes were immediately easy to perceive as introducing new environments for the peak delay rule. Sonorant syllabification or insertion of a svarabhakti vowel in words such as [1ʋoː.pn̩]/[1ʋoː.pən] (formerly Old Norse monosyllabic vás0pn) most probably was a gradual and variable phonetic process, where the status of a given realization of a word as mono- or disyllabic often may have been difficult to determine. As long as this indeterminacy persisted, it is likely that words that were subject to sonorant syllabification were treated as underlyingly mono-syllabic and not subject to the rule.Footnote 15

Given that the suffixed definite articles developed from morpho-logically independent determiners, it is highly likely that they went through a clitic stage on their way to suffix status. While most inflectional and derivational suffixes today trigger Accent 2 when added to monosyllabic stems, clitics never do. A case in point based on Norwegian examples is the difference between the preterite of the verb kaste ‘to throw’, /2kast-a/ with Accent 2, and the imperative of the same verb, kast, combined with the eastern Norwegian clitic /-a/ ‘her’, which results in /1kast-a/ ‘throw her’, with Accent 1.

Definite articles with no segmental traces of a plural marker still behave as clitics in this respect.Footnote 16 These include all singular forms irrespective of gender and the plural neuter /-a/, common in most Norwegian dialects. The important point here is that this change in status from clitic to suffix does not leave other overt traces in the surface forms that might lead speakers to reinterpret these forms and change the accent from 1 into 2.

In sum, I contend that Type 1 first hypothesis of how the accentual contrast arose has at least an equal claim to plausibility as Riad’s hypothesis. First, it is based on a common phonetic mechanism, peak delay, which like other phonetic factors causing language change may be active for specific periods of time in a given language. Second, the nature of the two changes that terminated the complementary distribution between mono- and plurisyllabic words can explain why newly introduced plurisyllabic words were not immediately recognized as such and thus were not subject to the rule assigning later timing of the H*, that is, Accent 2.

3.2 The Dialect Splits and Implications for the Present Study

I now turn to the later changes that led to the dialect variation that can be observed today. As with the tonogenesis itself, direct evidence of how accent realization has changed over time is scarce. Recordings only go back to the first half of the 20th century. Consequently, only changes from that time to the present can be charted with a reasonable degree of certainty through comparison of older and more recent recordings from a given area.

As far as I know, only two cases of internal change across generations have been published. Both are from western Norwegian dialects. The first is a change in a Type 1 dialect. Based on two data sets separated by two generations, Hognestad (Reference Hognestad2008, Reference DiCanio2012:262ff.) shows how the southwestern small town Flekkefjord dialect changed from subtype 1A into 1B. This means that the Accent 2 peak that used to be realized late in the stressed rhyme in the speech of the older generation migrated to an early position in the poststress syllable in the speech of the younger generation. At the same time, the Accent 1 peak also underwent delay, but remained confined within the stressed syllable. It is difficult to say whether this is a change driven by internal factors in the dialect or the result of influence from subtype 1B dialects spoken not far from Flekkefjord, but Hognestad notes that this change brings the dialect more in line with other southwestern Type 1 dialects.

In Hognestad Reference Hognestad2006, Reference DiCanio2012 (parts II and III, pp. 256ff.), an even more striking change is described, this time in Accent 1 realization, in the Type 2 dialect of Stavanger. Recordings made in the 1920s (Selmer Reference Selmer1927) show that the peak at that time occurred in the beginning of the stressed syllable. In the 1960s, as contours published in Fintoft 1970 show, the Accent 1 peak had moved to the final part of the stressed syllable. Recordings made by Hognestad himself of speakers born in the 1980s show that by this time the peak had migrated to the poststress syllable. During the same period of time, the Accent 2 melody remained unchanged.

To the best of my knowledge, these are the only examples of intergenerational changes that have been published, in addition to those presented in this article. Both show the same: Diachronic change of tonal accent realization is characterized by a gradual delay of H* tonal peaks with respect to the syllabic-segmental string. These changes are strongly reminiscent of the process which, as I have argued, was most likely the initial step toward the establishment of the accentual contrast—namely, peak delay.

One of the places where the two hypotheses tell different diachronic stories is the lower part of Dala-Bergslagen, where, according to the Meyer 1937, 1954 tables, a subtype 1B dialect is spoken. The Type 2 first hypothesis would have to derive this subtype B dialect from an earlier Type 2 system. By contrast, the Type 1 first hypothesis implies that the Dala-Bergslagen subtype 1B dialect has developed from an earlier system that was close to the original 1A pattern; the process of change was exactly the same as the one described by Hognestad (Reference Hognestad2008, Reference DiCanio2012:262ff.) for Flekkefjord, namely, migration of the Accent 2 H* across the boundary between the stressed and the poststress syllable.

In other words, under the Type 1 first hypothesis, at some point in time a subtype 1A dialect was spoken in the lower part of Dalarna. I further conjecture that the upper East Valley, Ovansiljan, at that time had no tonal contrast. From the lower part, the accent contrast spread northwards; it was first introduced in each dialect as a minimal peak delay in Accent 2 words, copying the accent pattern of the neighboring source dialect.Footnote 17

Once the contrast was acquired, over subsequent generations, continued peak delay in Accent 2 words increased the difference in timing between the two accent peaks. This hypothesis implies that the further up the valleys one goes, the smaller the timing difference between the two peaks will be. It also implies that there may still be dialects to which the contrast has not yet diffused, that is, dialects with no contrast, where all primary stressed syllables are realized with an early accentual peak. In other words, when the accentual contrast spreads northwards, it is introduced as a subtype 1A system with a minimal distance between the peaks. Further peak delay then gradually turns subtype 1A into subtype 1B dialects. Both Meyer’s survey and the Engstrand & Nyström’s analysis discussed in section 2 above support such a scenario.

4. Data and Methods of Analysis

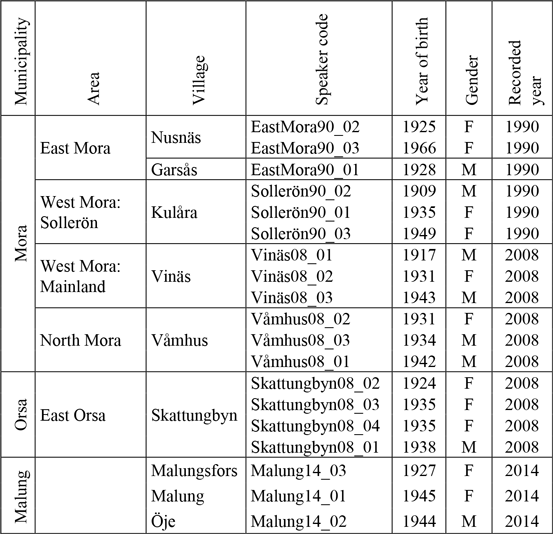

The data consist of recordings of mainly older dialect speakers from the upper eastern and western Dalarna region. Table 1 is a list of the speakers. The recordings were made during three field trips to the area. The first took place in 1990, when recordings were made in Älvdalen, in Sollerön, and in East Mora.Footnote 18 In 2008, I recorded speakers from Vinäs and Våmhus in Mora and Skattungbyn in Orsa. The final field trip, in 2014, took me to Malung, Lima, and Transtrand, the three northernmost communities in the West Valley. Of these, only the Malung recordings are explored in this article. In all the localities, initial contact was made with one person whom I had been referred to as a steady dialect speaker. This person then recruited the others.Footnote 19

Table 1. The speakers.

All the recordings included reading of a set of randomized carrier sentences with target words representing different types of Accent 1 and Accent 2, varying by vowel quantity, segmental material (voiced versus unvoiced consonants following the accented vowel), sentence position (final versus nonfinal), and word length. The structure of the carrier sentence ensured that all the target words were read as focused. Only disyllabic words with intervocalic voiced consonants, mostly sonorants, are used as data in this article. Especially in the earliest recordings, the number of data points for each speaker and each accent is unfortunately lower than it ideally should have been. There is, however, a large degree of consistency across speakers from each location, which to a certain extent makes up for the sparseness of data in these cases.

All the words in the data sets were annotated in Praat as intervals labeled VCV, with the left edge of the interval inserted at the beginning of the stressed vowel and the right edge 75 ms. into the poststress vowel. Figure 6 shows an example, the word koma ‘to come’, as spoken by one of the Sollerön speakers.

Figure 6. Interval annotation in Praat.

The VCV interval is annotated on the second tier. On the bottom tier, the stressed vowel rhyme is annotated as V1. After annotation of each file was completed, numerical data were extracted from the files by means of the Praat script Pitch Dynamics (DiCanio Reference DiCanio2012). For each VCV interval, the script returns, among other values, duration of the interval and the position of the maximal F0 value as a percentage of the duration. This is, in other words, a measure of the timing of the accent peak, which then can be related to segmental landmarks such as the end of the stressed syllable rhyme (that is, the syllable boundary) and the beginning of the unstressed vowel (that is, the VC_V boundary). The reason for only including a fixed part of the unstressed vowel in the interval is that the duration of this vowel may vary considerably. If the whole vowel duration had been included, the position of the peak as a measure of relative timing with respect to the stressed syllable would have been compromised.

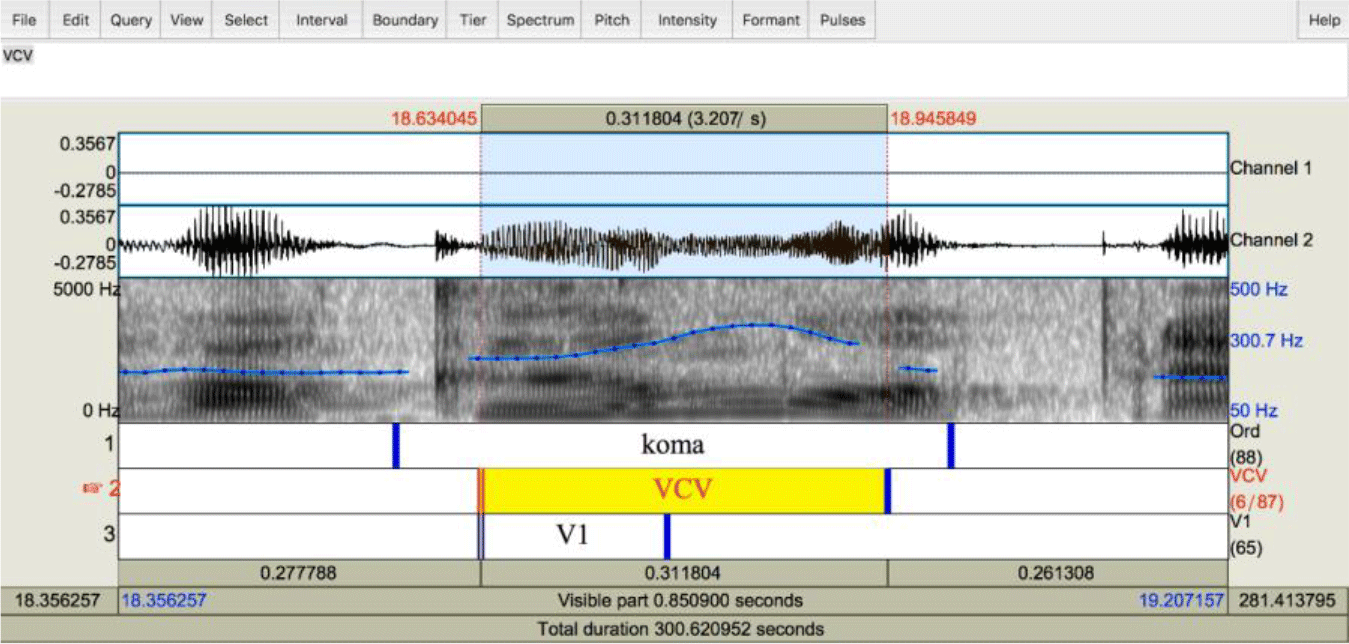

The script also returns F0 values for a number of measuring points that must be defined by the user. By means of these values, individual F0 contours for each word can be generated, and from these averaged contours for each accent type. The top panel of figure 7 shows the average Accent 1 and 2 contours and the distribution of peaks the male Vinäs speaker born in 1943.

Figure 7. Mean contours generated by means of Pitch Dynamics across 50 measuring points (top panel), distribution of peaks (bottom panel).

The most important measure for the purposes of this article is the percentage representing the position of the accentual peak within the VCV interval. As can be inferred from figure 7, the early initial peak of the Accent 1 contour will be reflected in a low average percentage, while the later peak of the Accent 2 contour will be reflected in a higher value. The average positions of the Accent 1 and Accent 2 peaks for this example are 10.2% and 51.8%, respectively (standard deviations 4.7% and 2.8%, p<0.001 by a simple t-test). As can be seen from the distribution shown in the bottom panel, in this very clear case there is no overlap at all between the Accent 1 and Accent 2 scores.

In order to provide measures that are maximally comparable to Meyer’s data, the peak positions were measured relative to the syllable boundary. These measures are easy to extract from words with long vowels, such as /2stiː.na/ Stina (proper name), since the boundary here coincides with the right edge of the vowel. In words with short vowel plus geminate consonant, such as /2tjin.nä/ kinna ‘to churn’, the syllable boundary falls somewhere within the intervocalic geminate, without any clear acoustic feature marking its precise location. In order to include this type in the data set, a way to infer the approximate location of the boundary in a nonarbitrary and transparent way is needed. One possible procedure would be to extrapolate from the duration of the long vowel rhymes and assume that the CVV and the CVC rhymes would have the same average duration as measured in percent of the total VCV duration. A better procedure, which allows one to analyze each CVC token separately, is to assume that the syllable boundary is located at the midpoint of the geminate in each token. This is the procedure chosen here.

5. Results

As mentioned above, Meyer (Reference Meyer1937:236) pointed out that the timing of the Accent 2 peak in his recordings from Dalarna correlated with geography in the sense that the further north a dialect was spoken, the earlier the peak occurred. For the purposes of this paper this means that the further north, the smaller the timing difference between the Accent 1 and Accent 2 peaks. This picture was later confirmed by Engstrand & Nyström (Reference Engstrand and Nyström2002) in their reanalysis of Meyer’s data, as reported in section 2 above.

In this section, I analyze the newer data, in order to i) see to what extent this correlation still holds, and ii) whether the timing of the Accent 2 peak has changed, as hypothesized in section 2 above. Recall that I categorize speakers whose mean Accent 2 peak is timed before the syllable boundary as subtype A speakers, and those whose peak timed after the boundary—as subtype B speakers.

The picture that emerges from what follows can be summarized as follows: In the more southern and southwestern areas, around the southern shore of Lake Siljan, and in Malung in the West Valley, the Accent 2 peak has been considerably delayed, to the point of becoming a clear B-subtype, since Meyer made his recordings. Further north, around the northern shore of Lake Siljan, subtype 1A is still the norm. Here nine out of the ten speakers examined have their mean Accent 2 peak before the syllable boundary. In the northernmost area, along the Type 2 isogloss, there is one dialect where the tonal contrast has only been partially implemented, and one where it is absent. There is, in other words, a clear pattern identical to the one Meyer found two to three generations earlier, with the important addition that in the northernmost part of the East Valley, the tonal contrast has not yet been fully implemented.

5.1. Transition from Subtype 1A to B in the South and West

Fransson & Strangert Reference Basbøll2005 investigate speakers from the communities of Rättvik and Leksand, near the southern shore of Lake Siljan. Their goal was to compare their results with those of Meyer, as digitized and measured by Engstrand & Nyström. The speakers were between 20 and 50 years of age, five from Leksand and six from Rättvik. They pronounced two words forming a minimal pair with respect to the tonal accent distinction; each member of the pair was read at least five times in the same carrier sentence.

In Engstrand & Nyström’s digitization of Meyer’s Reference Meyer1954 contours, the Accent 2 peaks in both communities roughly coincided with the syllable boundary, which can then be classified as an incipient subtype B. The speakers recorded by Fransson & Strangert realized their Accent 2 peak well after the boundary, with a mean of 59 ms. for the Leksand speakers and 67 ms. for those from Rättvik. Fransson & Strangert (Reference Basbøll2005:82) interpret this result in the following way:

Thus, in the light of the varying grave accent peak locations as demonstrated by Engstrand & Nyström (Reference Engstrand and Nyström2002), the southern type of accent realization (represented by Djura, Ål and Grangärde) would have progressed further to the north and north-west.

The “southern type of accent realization” refers to dialects spoken further south, where the Accent 2 peak was realized later in Meyer’s material. It should be noted that Fransson & Strangert also checked their results against the individual contours for the two communities reported in Meyer Reference Meyer1937. While the differences here appeared smaller, this does not change their conclusion. Within the analytical framework of the present paper, it can surely be concluded that the two dialects have changed from incipient subtype B into two clear subtype B varieties through Accent 2 peak delay.

The same development, but perhaps even more dramatic, can be observed in the northernmost Type 1 dialect in the West Valley, Malung. In 2014, I recorded three speakers, one male born in 1944 and two females born in 1945 and 1927. The 1945 speaker (Malung14_01) was recorded twice, reading the same set of sentences both times. Since most of Meyer’s speakers were born late in the 19th century, there are about two generations between the two speaker groups.

The material was a set of scripted sentences where target words were read in prefocal, focal, and postfocal position. The set of words read as focal is the one that is closest to the material used by Meyer and Fransson & Strangert, so I concentrate on this subset of the material here. The Accent 2 part of this subset consisted of three disyllabic words with initial stress and a sonorant intervocalic consonant, each read six times by each speaker.

According to the table in figure 5 above, which shows the results of Engstrand & Nyström’s digitization and analysis of Meyer’s contours, both the Accent 1 and the Accent 2 peaks occurred before the syllable boundary in the Malung contours, by -32 and -6 arbitrary units. These numbers are based on the two Malung speakers represented in Meyer’s 1954 table.

Table 2 shows the position of the Accent 2 peak relative to the syllable boundary for the three speakers compared with the two Malung speakers represented in Meyer 1954.

Table 2. Malung: Accent peak positions relative to the V.CV syllable boundary.

The measurements given for two of Meyer’s speakers are approximations arrived at by dividing the bottom line of each of Meyer’s panels into 20 identical parts, and then magnifying each panel such that each part became equivalent of 5 mm. Based on this scale, the peak positions were calculated by hand. For the three speakers recorded in 2014, the peak position was calculated as explained in section 4. The syllable boundary is set at 100%, such that values below this mark indicate peak positions before the boundary and thus within the stressed syllable. Values above indicate peak positions in the poststress syllable.Footnote 20 While Meyer’s two speakers have their Accent 2 peaks before and at the syllable boundary, the three younger speakers recorded in 2014 all have Accent 2 values far above 100%. For Accent 1, there is no clear differences between the two age groups.

To the extent that Meyer’s two speakers were representative of their age group, these results and the results of Fransson & Strangert strongly suggest that Accent 2 peak delay is an active and ongoing change in the lower part of the two valleys today and that Malung, Rättvik, and Leksand switched from subtype 1A to subtype 1B in the course of about two generations.

5.2. The Subtype 1A Dialects Around the Northern Shore of Lake Siljan

In this section, I consider the timing of the Accent 2 peak in recordings of speakers from three parts of the Mora municipality south of the town of Mora, Sollerön, Vinäs, and East Mora. Engstrand & Nyström’s measurements of Meyer’s contours show that the speakers from the Mora and Orsa municipalities have the earliest realization of the Accent 2 peak of all the Dalarna speakers.

As can be seen from figure 3, Sollerön is a big island off the northeastern shore of Lake Siljan. The three Sollerön speakers analyzed below all come from the village of Kulåra in the southwestern part of the island. The village of Vinäs is on the mainland northeast of Sollerön. I refer to these dialects as belonging to the Sollerön type and to the area as West Mora. The East Mora villages are situated along the northeastern shore of Lake Siljan, opposite of Sollerön. Two of the speakers recorded came from the village of Nusnäs and the third from Garsås, some kilometers further south.

Before discussing the timing patterns in these dialects, one needs to take a closer look at another change that interacted with the tonal accent development, namely, the quantity shift. This is a change whereby all former light stressed syllables in North Germanic are lengthened into bimoraic heavy syllables (see, for example, Kristoffersen Reference Kristoffersen1994, Reference Hognestad2008, Reference Bye2011; Riad Reference Riad1995). In other words, an original CV.CV structure would lengthen into a CVV.CV or a CVC.CV structure, depending on dialect. An example is Old Norse /ko.ma/ ‘to come’, which in the Sollerön type dialects is realized as [2kʉː.mɔ]. The shift is completed in almost all dialects spoken in Sweden and Norway today, but a few relict areas remain. One is the northernmost part of the East Valley, where all of Älvdalen and at least the villages of Våmhus in Mora and Skattungbyn in Orsa have not yet undergone the change. Here the pronunciation of ‘to come’ is [2kʉ.mɔ]. Importantly, all disyllabic words where the lengthening has taken place have Accent 2.

In the dialects discussed in this section, the shift had some unusual effects. As shown in Kristoffersen 2010, it resulted in three distinctive and significantly different accent patterns in the Sollerön type, with an early peak in Accent 1 words, a later peak in Accent 2 words with an original heavy stressed syllable, and an even later peak in the lexical set that underwent the shift. I refer to the two latter types as Accent 2a and Accent 2b, respectively.

A plausible explanation for this development, in line with the analyses offered in Kristoffersen Reference Hognestad2008, Reference Kristoffersen2010, is that when the accentual contrast was introduced into the dialect, the quantity shift had not yet taken place. If one conjectures that the Accent 2 peak delay as measured in ms. was about the same irrespective of the quantity of the stressed syllable, it would have been timed later in the 2b words with respect to the syllable boundary, due to the short vowel and short intervocalic consonant. The Sollerön contours in the final foldout table in Meyer 1937 clearly confirm this. In words with etymologically heavy root syllable, the Accent 2 peak occurs before the syllable boundary. In words with etymologically short vowel, it occurs after the boundary. When the quantity shift hit the dialect, this different synchronization with the syllabic string was maintained, resulting in the present timing differences between the 2a and the 2b sets.Footnote 21

Across the lake, in East Mora, I assume that the same timing difference existed between words with light and heavy stressed syllables: In the former, the Accent 2 peak fell somewhere in the then poststress syllable. This late realization of the peak then seems to have triggered the very common tendency to associate high tone with stress, so that prior to the quantity shift, the word stress in these words shifted to the final syllable.Footnote 22 As interesting and rare as this development may be, the stress shift has made the set of former CV.CV words peripheral as data for the story told in this paper, and they are not considered further.

When Lars Levander wrote his two-volume survey of the Dalarna dialects (Levander Reference Levander1925, Reference Levander1928), the quantity shift seems to have been underway both in East Mora and in Sollerön. In the examples of East Mora 2b forms given in 1925:56, most but not all final vowels are transcribed as long, while those followed by a consonant are still short. In the inflectional tables in 1928:169–253, however, every one of the numerous examples from East Mora with final stress is transcribed with short vowel, irrespective of the presence of a final consonant. In the recordings that I made in 1990, all final stressed vowels were long.

Sollerön 2b-class words are also consistently transcribed by Levander (Reference Levander1928:169–253) with a short root vowel, as can be seen from the inflectional tables. However, this may also be a result of etymologically biased principles of transcription. Elsewhere (for example, Levander Reference Levander1925:66f.) he writes that the vowels are in the process of being changed into “half long” and even long, while at the same time the old pattern is still alive.Footnote 23 Meyer confirms this: In the description of his Sollerön speakers he notes that these vowels have been lengthened, but without showing full length in line with etymological long vowels (Meyer Reference Meyer1937:65, 160).Footnote 24

These observations suggest that the short vowels of the 2b type were in the process of lengthening during the first two decades of the 20th century, when Meyer made his recordings of young men born shortly before the turn of the century. In the recordings I made in 1990 and 2008, these vowels were all long, even in speakers born as early as 1909 and 1917. In the light of the remarks made by Levander and Meyer referred to above, lengthening must have taken place quite recently.

Meyer recorded two speakers from West Mora, LP from Sollerön, born in 1888, and AÖ from Isunda, a village on the mainland between Sollerön and Vinäs, born in 1898. Their scores, based on Meyer’s 1954 contours, have been calculated as described in section 5.1. Results are shown in table 3, where the speakers are ranked by location and then by age. The Accent 2a scores show that almost all the speakers are characterized by a clear subtype 1A system, with the Accent 1 scores falling in the first half of the stressed syllable (<50%), and the Accent 2a scores in the second half (>50%). The only exception is the oldest of Meyer’s speakers, whose Accent 2a score is also below 50%.

Table 3. Accent peak positions relative to the syllable boundary in the East Mora, Sollerön, and Vinäs recordings.

These scores show that the East and West Mora speakers are different from the Leksand, Rättvik, and Malung speakers analyzed above, whose systems clearly belong to the 1B subtype. When it comes to the Sollerön 2b type, however, the peak is realized considerably later than in the 2a type, with four out of six speakers having the peak in the poststress syllable. These dialects can therefore be characterized as a mixed type, with Accent 2 realizations split between 1A and 1B conditioned by the quantity shift.

Another interesting feature, although limited to the Sollerön type, is that among the speakers recorded in 2008 there appears to be a correlation between age and degree of peak delay for both Accent 2a and 2b: The younger the speaker, the longer the delay. The only exception is the tie with respect to Accent 2b between the two youngest speakers from Sollerön. Even if the number of speakers is too low for drawing conclusions, it is tempting to interpret these differences as a reflection of the Accent 2 peak delay gradually progressing through the age groups in these dialects.

However, this age-scaling is not reproduced in the East Mora scores. Here, all three speakers show fairly advanced peak delay, approaching the syllable boundary. The outlier, from this perspective, is the much younger third speaker, 03. Given the age difference and in the light of the results from the other locations, one would have expected a much later Accent 2 peak realization here, that is, a 1B subtype. A fact that should be taken into consideration here is that she did not acquire the dialect primarily in the village. Both her parents were from East Mora. Before the speaker was born, they moved to Falun, a medium-sized town further southeast in Dala-Bergslagen and south of the two valleys. The East Mora dialect was used at home, so that the speaker grew up bilingual, with the dialect used at home and a regional Standard Swedish used, for example, in school. During holidays, which were spent in the village, she used the dialect with others, not only her parents. At 24, when she was recorded, she appeared as a very conscious dialect speaker, aware of its endangered state, and she may have consciously or unconsciously modeled her speech on her grandmother, speaker 02.

5.3. The Northernmost Dialects: Partial and Full Absence of Contrast

I now move to the northernmost part of the Type 1 area, which consists of the part of the Mora municipality north of the town of Mora and the Orsa municipality to the northeast of Mora. To the northwest, Mora borders on the Älvdalen municipality, where the dialect, as noted above, is characterized by double-peaked Type 2 Accent 2.

The earliest descriptions claimed that there was no accent distinction in Orsa and Mora. This was the conclusion of Rydqvist (Reference Rydqvist1868:218), whose work, some years later, was accepted and referred to by Axel Kock (1878–1885:53). Adolf Noreen in his earliest study of the Dalarna dialects also concluded that there was no accent contrast in the northernmost areas south of Älvdalen (Noreen 1881:9). Some years later, however, he expressed doubt about this conclusion (1907:472).Footnote 25 The first to show that there was indeed an accent contrast in Orsa was Johannes Boëthius in his 1918 analysis of the sound system of the dialect. He refers to discussion with and assistance from Meyer, and his description of the realization of the contrast accords well with the contours later published by Meyer.

Meyer did not record any speakers from the northern part of the Mora municipality, but he did record three speakers from Orsa. They came from three different villages, Sundbäck, Vångsgärde, and Skattungbyn, and were born in 1903, 1872, and 1899. Sundbäck and Vångsgärde are located close to each other in the southwestern part of the municipality, not far from the border with Mora and the town of Mora. Skattungbyn is located at the other side of the municipality, near the northeastern border, as shown in figure 3. Meyer’s contours all show the same pattern, early Accent 1 peak, and the Accent 2 peak before, but close to the syllable boundary, that is, subtype 1A, as expected.

In more recent recordings from Orsa no further peak delays compared with Meyer’s contours can be found. Olander (Reference Engstrand and Nyström2002) analyzes three speakers, who, when recorded around the turn of the century, were 68, 68, and 34 years old. This means that the 68-year old speakers were born around 1930, while the 34-year old one was born in the mid 1960s. Olander does not mention what part of the municipality the speakers came from. She does not give a full quantitative analysis of the speakers, but the examples given clearly show that the Accent 2 peaks occur well before the syllable boundary. Olander notes herself that the timing of the peaks is not noticeably different from that shown in Meyer’s contours.

In 2008, I recorded speakers from two locations in this area, Skattungbyn in Orsa and Våmhus in Mora. As already mentioned, Skattungbyn is near the northeastern border of Orsa, far from the main valley and the more densely populated areas around Lake Siljan and Lake Orsa. The speaker recorded by Meyer was born in 1899. In his description of this speaker Meyer noted that the contour of Accent 2 words with long vowels was very similar to the Accent 1 contour in that both were characterized by early peaks. In words with short vowel, both in CV.CV and CVC.CV structures, the peaks occurred later (Meyer Reference Meyer1937:180f.). However, Meyer still claimed that there was a small timing difference between Accent 1 words and Accent 2 words with long vowels. In addition, he claimed that the Accent 2 contours showed a less peaked form than the Accent 1 contours.

The four speakers that I recorded in Skattungbyn in 2008 were born in 1924, 1935, 1935, and 1938. The youngest was male, the other three female. In these recordings, the unusual realization of Accent 2 in words with long vowel found by Meyer is confirmed. In figure 8, the grey line represents words with long vowels that have Accent 2 in other dialects. As can be seen, the contours representing Accent 1 words and Accent 2 words with a long vowel are identical. There are no traces of the lower Accent 2 peak of Meyer’s speaker.

Figure 8. Skattungbyn: Tonal accent contrast, averaged contours for speaker Skattungbyn_02.

This state of affairs, namely, the accent contrast being governed by quantity type, is to the best of my knowledge unique among the tonal dialects of Norway and Sweden. It is, however, found in another geographically peripheral tonal dialect, on the island of Langeland in Denmark, to the south of the regions characterized by stød. According to Kroman (Reference Kroman1947:76ff.), Accent 1 characterizes polysyllabic words with an etymologically long root vowel, while Accent 2, with several segmental exceptions, characterizes words with an etymologically short vowel, including those in former CV.CV structures, which have later been lengthened.Footnote 26

In the data on which the contours shown in figure 8 are based, there is a potential error source that must be cleared away. The long vowel Accent 2 contour is based on several readings of the same word, the female proper name Stina. Quite a few examples show that the accent type associated with proper names may vary by geography. For instance, the names Anna and Sara have Accent 2 in most western Norwegian dialects, while they have Accent 1 in eastern dialects. So even if Stina has Accent 2 in most Swedish dialects, it could exceptionally have Accent 1 in Skattungbyn. This is not the case, however. Decisive evidence is provided by an analysis of accent realization in the conversation between the four speakers that I recorded after the readings were finished. Figure 9 shows the results across the three female speakers. Here, too, the grey line represents words with long vowels that have Accent 2 in other dialects. As can be seen, the results are exactly the same as those ensuing from the analysis of the reading material. I therefore conclude that Accent 2 is limited to words with a short root vowel in Skattungbyn.Footnote 27

Figure 9. Skattungbyn: Tonal accent contrast across the three female speakers, as realized in conversation.

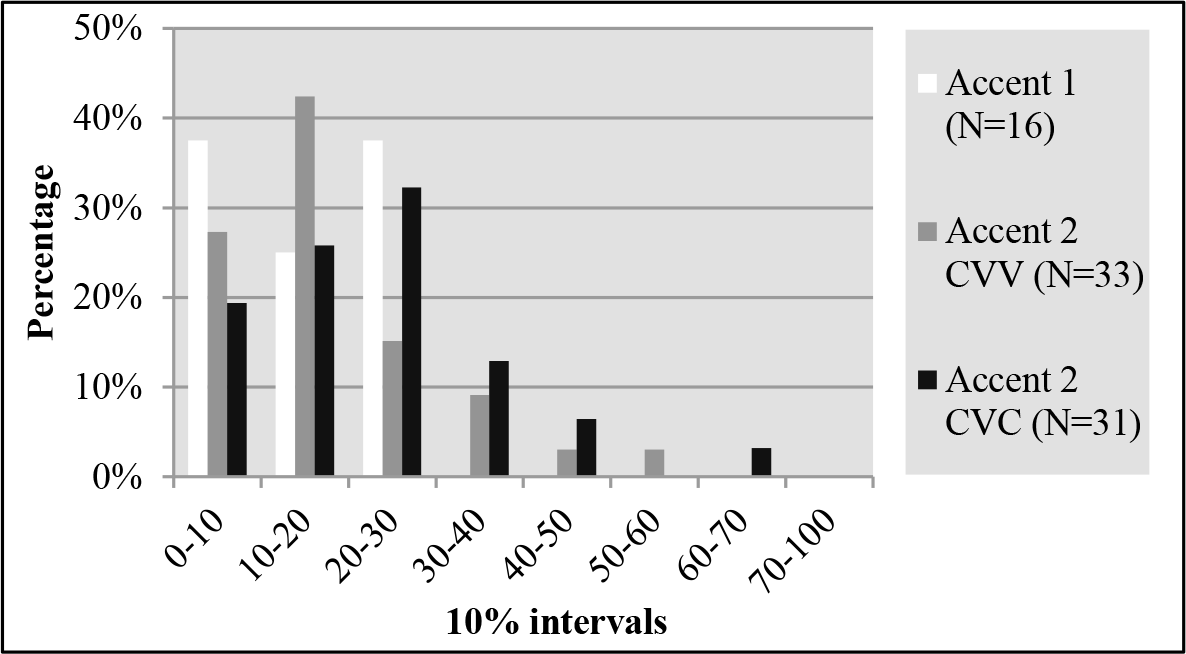

The more detailed timing data for all four Skattungbyn speakers recorded in 2008 are shown in table 4. There seem to be no age-related differences here. However, while two of the speakers, 02 and 03, appear to have no contrast between Accent 1 and Accent 2:CVV, the other two show intermediate values between Accent 1 and Accent 2:CVC, but still much closer to Accent 1. This may be interpreted as an early emergence of the contrast in this environment as well. Even if the averages are based on few tokens, it is all the same suggestive that t-tests for the two speakers with different Accent 1 and Accent 2:CVV averages, 04 and 01, approach significance (p=0.062 and 0.074, respectively). The corresponding values for 02 and 03 are 0.916 and 0.475.

Table 4. Skattungbyn: Average timing of accent peaks in disyllabic scripted words relative to the syllable boundary.

Recall from the discussion of the Sollerön and Vinäs dialects in section 4 above that after the quantity shift, the former CV.CV class showed a later peak than the Accent 2 words with an etymological heavy root syllable. I hypothesized that this was a result of a later timing of the peak relative to the syllable boundary before the shift which had been preserved when the vowel lengthened due to the shift. As noted in section 4, Skattungbyn is home to such a prequantity shift dialect. As can be seen from the rightmost column in table 4, here again the four speakers split into two groups, the same two groups that showed signs of a possible, incipient peak delay in Accent 2 words with long vowels. Two speakers, 04 and 01, also show a marked difference in timing between the CV.CV and the CVC.CV type.

It is tempting to hypothesize that here one witnesses two stages in the acquisition of a Sollerön/Vinäs type system. Speakers 02 and 03 represent an older system, where the peak in CV.CV words is also constrained by the syllable boundary. Speakers 04 and 01 represent a more advanced stage, where words with a long vowel that have Accent 2 have begun showing signs of peak delay, and where the peak in CV.CV words has moved to the poststress syllable. Both of these features can be observed in Sollerön and Vinäs.

At first glance, the problem with this hypothesis is that there are geographically intermediate dialects in Orsa where these two stages have not been explicitly noted (see, for instance, Meyer’s Reference Meyer1937:170–178 description of the two Orsa speakers who did not come from Skattungbyn). However, a closer look at Meyer’s description of the speech of the first speaker (Erik Eriksson from Sundbäck, born in 1885) suggests that there could be a similar stage difference. Meyer states that in the Accent 2 CVV words, “the pitch rises through a little more than half of the vowel (on average 6/10)” (p. 172), while in the CVC type, he states that the syllable boundary falls around 3/5 into the intervocalic consonant, and this is where the peak occurs (p. 173). In other words, in the CVV type, the peak occurs well before the end of the vowel, and thus the syllable boundary, while it falls near the syllable boundary in the CVC type. This is also the case in the CV type (p. 174). This is Meyer’s own interpretations of the relevant contours. (However, upon visual inspection of the same contours as they are reproduced in the text, the difference is not as clear.) In his description of the speech of the second Orsa speaker, Hans Bellin from Vångsgärde, about one kilometer west of Sundbäck, born in 1872, Meyer is vaguer, but it appears that to the extent that there is a difference, it is smaller than the one he describes for Eriksson. In the CVV type, the peak falls on the average at 8/10 of the vowel duration, while in the CVC type, the fall starts “mehr oder weniger weit in den Konsonanten hinein” [more or less far into the consonants] (p. 177).

As noted above, the Skattungbyn correlation between quantity type and accent assignment is a very rare one, only documented in one other dialect, Langeland in southern Denmark. Given that both dialects are spoken at the border between accentual and nonaccentual dialects, this partial contrast dependent on quantity type may be interpreted as a temporal stage between no contrast and the normal state, that is, contrast independent of quantity. From this perspective, it would be interesting to check whether traces of this distinction can be found in the dialects of Sollerön, Vinäs, and East Mora, where the accentual contrast has reached a more advanced state than in Skattungbyn.

Table 5 shows the timing differences between the two syllable types for all the Sollerön, Vinäs, and East Mora speakers, ranked by age within each group. In Sollerön and East Mora, the differences correlate with age, in that the older speakers show a positive difference, that is, a later timing in the CVC type than in the CVV type. In the younger speakers, there is no difference or a weak negative difference. By contrast, in Vinäs no such correlation emerges, but again, it must be pointed out that the number of data points is too small for solid conclusions to be drawn. That being said, a tendency that supports the hypothesis derived from the Skattungbyn results, that Accent 2 was established in words with short root vowel before it spread to words with long root vowel, can also be observed here.

Table 5. Timing differences in Accent 2 words with short versus long root vowel in Sollerön, Vinäs, and East Mora.

In the cluster of villages named Våmhus north of the Mora municipality and bordering on Älvdalen, there is no tonal accent distinction, as first pointed out in Kristoffersen 2017. Since Meyer did not record speakers from Våmhus, this lack of contrast seems to have gone unnoticed until it clearly emerged from the recordings that I made in Våmhus in 2008. Figure 10 shows the average F0 contours of accented disyllabic words classified by accent type, Accent 1, Accent 2:CVV and Accent 2:CVC for one of the three speakers, 02, born in 1931. As can be seen, all three types are realized with an early peak, with no clear timing differences corresponding to the ones found in East Mora, Sollerön, Vinäs, and Skattungbyn. The contours of the other two speakers from Våmhus, 01, born in 1942, and 03, born in 1934, show the same pattern.

Figure 10. Våmhus: Absence of tonal accent contrast; averaged contours for speaker Våmhus_02.

This lack of accentual contrast fits nicely with the pattern described above. Våmhus can now be seen as the logical end point of the gradual decrease in Accent 2 peak delay from south to north. Under this interpretation of the facts, Våmhus is located at the northernmost edge of the Dala-Bergslagen Type 1 area, where the accent contrast has not yet been introduced.

Table 6 shows the average peak timing for the same four categories as analyzed in the Skattungbyn material: Accent 1 irrespective of root syllable quantity, Accent 2 with a heavy stressed syllable and a long vowel (CVV), Accent 2 with a heavy stressed syllable and a short vowel (CVC), and Accent 2 with a light stressed syllable (CV). As with the Skattungbyn results shown in table 4, the timing is relative to the syllable boundary.

Table 6. Våmhus: Average timing of accent peaks in disyllabic, scripted words in Våmhus relative to the syllable boundary.

The differences are very small, with none of the Accent 2 values being very different from the Accent 1 values, as was the case with the CVC and the CV types in the Skattungbyn data in table 4. There are small differences in the right direction, in the sense that the Accent 2 categories for the two male speakers show a slightly later timing than Accent 1.

As with the Skattungbyn data, I have annotated accented words in the recorded conversation of the youngest of the Våmhus speakers, 01.Footnote 28 Figure 11 shows the average contours for this speaker (Våmhus_01), based on the scripted material in the top panel, and on the conversation in the bottom one. Even if the average peak of the CVC type occurs earlier in the conversation material than in the scripted material, the less steep fall in the former suggests a wider distribution of the values.

Figure 11. Våmhus: Comparison of contours derived from the scripted material (top panel) and conversation (bottom panel).

One should therefore take a closer look at the distributions behind the contours as well. Figure 12 shows how the peaks are distributed by category along the percentage scale. There is a clear difference between Accent 1 on the one hand and the two Accent 2 categories on the other, in that the latter shows a much wider distribution, even if the majority of data points here are also found in the lower part of the scale. Between the two Accent 2 categories there is a similar difference, in that the CVC distribution peaks at one interval above the CVV type. It is tempting to interpret these differences as support for a conjecture that at least this speaker shows an incipient accent contrast that seems to be led by the CVC type. Thus, while both the scripted and conversational data show that there is no accent contrast in the Våmhus dialect of the fully developed type seen in the other dialects, the first signs of its appearance can perhaps be observed in 01’s speech.

Figure 12. Våmhus: Distribution of individual peaks in conversation by accent category. Speaker Våmhus_01.

Although not a necessary part of the Type 2 first hypothesis, it is possible to construe an alternative scenario where the Ovansiljan dialects represent the final stage of a change from Type 2 to Type 1. In other words, it is possible that these dialects at an earlier stage had the same system as their northern neighbor Älvdalen. If this were the case, and if the change took place not too long ago, one would expect that generations older than my three speakers, born between 1931 and 1942, would have had a clearer contrast. To check this, I analyzed three recordings provided by the Swedish Institute for Language and Folklore (Institutet för språk och folkminnen) in Uppsala. The speakers, all male, were born in 1860 (recorded in 1935), 1864, and 1873 (both recorded in 1948).Footnote 29 Only Accent 2 words that I recognized were annotated. The results are shown in figure 13. In addition to the three speakers born in the 19th century, I have included the CVC conversation contour for speaker 01, born in 1942, for comparison, copied from figure 11.Footnote 30

Figure 13. Våmhus: Average realizations of Accent 2 words from four speakers born between 1860 and 1942.

No discernible changes seem to have taken place over the generations between the 1860s and the 1940s. The absence of tonal contrast therefore goes back at least to the generation born early in the 19th century. Since the tonal contrast arose during the Mediaeval Age, there is of course still a gap of several hundred years, and one cannot know for sure how accented syllables were realized during this time, neither in Våmhus nor in any other North Germanic variety. However, in the absence of stronger arguments to the contrary, the least radical option is that Våmhus never had such a contrast. The fact that all (or at least most) surrounding dialects today have the contrast is, in my opinion, not a strong argument in favor of Våmhus at some earlier point in time having had one. The more likely scenario is rather the one proposed here, that the other dialects of Ovansiljan at some time in the recent past also lacked the contrast, and that the unusual features in these dialects, as well as the incremental peak delay in dialects further south bear witness to this.

I showed above that there was a small difference in the speech of 01 in the distribution of peaks between the CVC type and the CVV type of Accent 2, and that both differed from Accent 1 (see figure 12 above). If this, as suggested, is an incipient appearance of a contrast, a similar difference in the older data would invalidate this conjecture. I therefore checked whether there was such a difference between the two types in the older material. There was not. No such tendencies can be seen in the distributions of the older speakers born in the 19th Century.

To summarize, two patterns have emerged from the analysis in this section, one solid and, as far as I can see, uncontroversial, based on generational differences, and one more tenuous, based on small age-related individual differences within dialects and small differences between dialects. The first pattern was observed in communities situated in the southern part of the two valleys; it shows that over a few generations, the Accent 2 peak has migrated across the boundary between the accented stressed syllable and the following unstressed syllable. Even if the number of speakers investigated is limited, the pattern is consistent enough for one to believe that it is not spurious.

The second pattern involves smaller differences among the speakers from the more northern villages of Mora and Orsa. There is a greater chance of those smaller interspeaker differences being accidental. However, they are quite coherent from the tonogenetic perspective, which suggests that they might be reflecting an actual pattern. The correlation between peak delay and age in the Sollerön type; the difference between words with long and short vowels in Skattungbyn; the equally weak signs of an emergent accent distinction in Våmhus—all of these features suggest that the accentual distinction is a relatively recent phenomenon in Skattungbyn and the West and East Mora dialects, with at least one Våmhus speaker perhaps representing a very early stage of accent acquisition.

It is harder to decide how recent this phenomenon is. However, given the peculiar development in the West and East Mora dialects contingent on the quantity shift, the tonal accent distinction must have preceded the quantity shift, since the third accent in the Sollerön type and final stress in East Mora most probably was an effect of later timing of the Accent 2 peak in the class with an etymological short root vowel. Since, as argued in section 5.2 above, the quantity shift seems to have taken place during the early decades of the 20th century, the latest possible point in time for the introduction of the accent contrast in Sollerön and East Mora must have been the second half of the 19th century.

6. Discussion

6.1. Diffusion Driven by Peak Delay

The hypothesis that emerges from the results presented in the previous section is that at some point in the past, subtype 1A also characterized the lower part of Dalarna. At that time, the upper East Valley, Ovansiljan, had no tonal contrast. From the lower part, the accent contrast started spreading north; it was first introduced in each dialect as a minimal peak delay in Accent 2 words, modeled on the accent pattern of the neighboring source dialect. Once the contrast was acquired, the difference in timing between the two accent peaks increased over subsequent generations, due to continued peak delay in Accent 2 words. This hypothesis implies that the further up the valleys one goes, the smaller the timing difference between the two peaks will be, which, as I have shown, is exactly the case. By this hypothesis, it does not come as a surprise that there are still dialects near the northern border of the Type 1 area to which the contrast has not yet diffused, that is, dialects with no contrast, where all primary stressed syllables are realized with an early accentual peak.

An important assumption here is that phonetically grounded changes are not automatic; they may emerge and disappear in languages and dialects at different points in time. I assume that when the tonal timing contrast was established and phonologized in North Germanic during the late Mediaeval Age, the two accents emerged as two separate phonological units that subsequently developed independently: Certain changes could happen to one accent without necessarily affecting the other at the same time. For instance, the Stavanger Accent 1 change referred to above left the Accent 2 melody unchanged. In contrast, in Flekkefjord both accents appear to have changed in a kind of chain shift.

Finally, changes may arise spontaneously in a given dialect, which is most probably the case in Stavanger. However, they may also be the result of geographical diffusion, where different sociolinguistic forces may play a role. This may have been the case in Flekkefjord (combined, perhaps, with an activated drive toward delay), with most dialects in the surrounding region appearing to be of the 1B subtype, as noted by Hognestad (Reference Hognestad2008). In Dalarna, the contrast appears to arise in new dialects by diffusion from a neighboring dialect. Once the minimal and perhaps partial accent contrast is established, as seen in Skattungbyn, over time peak delay in Accent 2 words makes it more robust.

6.2. Implications for the Tonogenesis Problem

One of the places where the two hypotheses tell different stories with respect to diachronic roots is the lower part of the Dala-Bergslagen, where, according to the Meyer’s (Reference Meyer1937, Reference Meyer1954) tables, a subtype 1B dialect is spoken. The Type 2 first hypothesis will have to derive this dialect from an earlier Type 2 system. In contrast, the Type 1 first hypothesis implies a simpler story: The Dala-Bergslagen subtype 1B dialect has developed from an earlier dialect that was close to the original 1A pattern by a process that is exactly the same as the one described by Hognestad (Reference Hognestad2008, 2012:262ff.) for Flekkefjord, namely, migration of the Accent 2 H across the boundary between the stressed and the poststress syllable.

A full-scale critique of Riad’s Type 2 first hypothesis as briefly presented in section 3.1 above lies beyond the scope of the present article. However, the results presented in section 5 further support the Type 1 first hypothesis, namely, new examples of change instantiated as peak delay have been added to the cases in southwestern Norway (see section 3.2).

If one assumes that the dialect splits took place through gradual changes in the synchronization between tonal units and the syllabic-segmental string, such a development can in principle follow two distinct paths: Retraction will result in earlier and delay will lead to later realization of the F0 peaks with respect to the syllabic-segmental string. This is not an uncontroversial assumption: Alternatively, two categorically distinct forms—an old one and a new one—may alternate for a time, until the new one supersedes the old one. This is a well-known pattern seen in a great body of sociolinguistic studies. However, as shown in this article, this is not how the North Germanic tonal accent patterns seem to change. Instead, tonal timing appears to change gradually, in much the same way as vowel patterns have been shown to change (see, for example, Labov Reference Labov1994, part B).

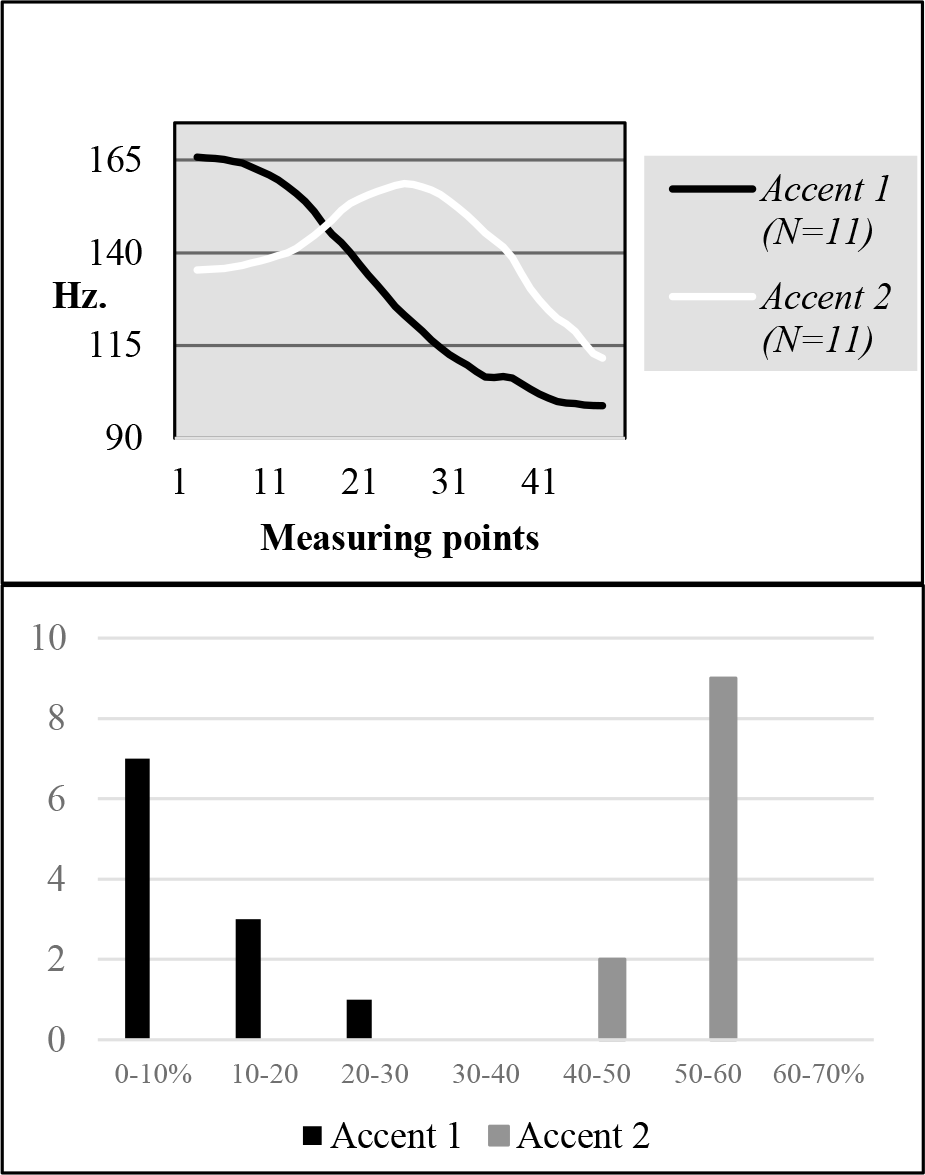

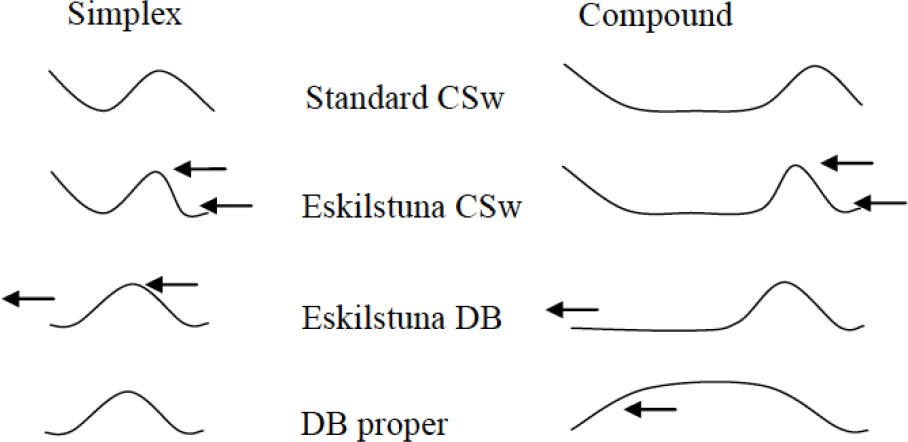

In sections 3 and 5, several examples of change by gradual peak delay were presented. At the same time, no equally well-documented examples of change by peak retraction exist, as far as I know. Yet Riad’s account of how the Dala-Bergslagen pattern developed from central Swedish Type 2A does assume retraction (Riad Reference Kristoffersen2000c, Reference Riad2009). Figure 14, reproduced from Riad 2009:16, shows how the steps are conceptualized that lead from the central Swedish Accent 2 melody to the one found in the lower Dala-Bergslagen area today, both in compounds and simplex disyllabic words. The first step is leftward movement of the final peak under pressure from the final L, which then results in gradual annihilation of the initial peak. Finally, the remaining single peak retracts even further, resulting in association near the stressed syllable. This is the typical form of a subtype 1B variety found in lower Dala-Bergslagen today, and which Riad refers to as “DB proper” in figure 14.

Figure 14. From the Standard central Swedish double-peaked subtype 2A variety to the Lower Dala-Bergslagen subtype 1B variety.

The changes documented in section 5, on the contrary, suggest that DB proper should be seen as the result of the peak delay processes that characterize the Dalarna dialects. The Type 1 first hypothesis, in other words, predicts that the Dala-Bergslagen variety at an earlier stage had a 1A system like the ones found in Ovansiljan today, and that Accent 2 peaks over time have come to be gradually delayed, resulting in a 1B system. This would be a process like the ones that have been documented in the lower part of the valleys in Leksand and Rättvik, as shown by Fransson & Strangert (Reference Basbøll2005), and in Malung, as shown in the present paper.

An interesting question that the present analysis cannot say anything definite about is the diachronic relationship between Dala-Bergslagen subtype 1B and subtype 2A dialects spoken further south toward Stockholm. As shown by Riad (Reference Riad2009), they appear to meet and coexist in the town of Eskilstuna, where the Type 2 forms are often realized with the stød-like final fall that Riad associates with an incipient stød. By this account, the Type 2 realizations are about to give way to Type 1 (see again figure 14 above, where the two patterns are referred to as Eskilstuna DB and CSw, respectively).

Riad’s data, as presented in 2009, are not extensive and systematic enough to settle the question. A substantial and systematic sample of speakers categorized by at least the traditional sociolinguistic factors age, gender, and social background, and possibly different parts of town, would be needed to establish if one variant is in the process of giving way to the other. A quantitative analysis based on methodology—such as, for example, the one outlined in section 4 above—could also establish if the two variants are categorially different or part of a continuum. Only if the latter were the case and the change were in the direction of Type 2, peak delay could be invoked as its possible driving force. If instead there is a retraction process going on, one should perhaps ask if influence from the nearby prestigious Stockholm dialect could be the source of the Eskilstuna Type 2 variant, even if it differs somewhat from the Stockholm dialect with respect to the timing of the final HL fall.