INTRODUCTION

It’s the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic and we’re all worn out. The pandemic has challenged us. It has changed us. It has revealed the fractures and fissures within society that many knew were present but most chose to avoid or ignore. Most of all, it is not over.

This pandemic also has reminded virtually every one of the importance of history—and of understanding past pandemics in particular. Comparisons abound. Historical “lessons” have spread almost as rapidly as the virus. In particular, the 1918–19 influenza pandemic has become a major subject of interest.Footnote 1 So, where do we stand?

In world historical terms we have arrived at an amazing moment: the fastest successful global race to not one but several effective vaccines in human history. Increasing production, distribution, and vaccinations by spring and early summer 2021 made the resumption of some sort of “normal” life seem possible, at least in countries with significant vaccine access. Yet just as optimism was dawning, the rise of the more infectious Delta and Omicron variants combined with the presence of large blocks of unvaccinated people has altered fundamentally the pandemic landscape.

In 1918 scientists and medical professionals searched desperately for an effective vaccine or treatment that might slow the spread and prevent deaths. Trains with prototypes raced across the United States to get needles into arms. But to no avail. In 2020, in contrast, with modern medical knowledge of viruses, DNA, and the human genome, massive scientific efforts paid off handsomely. By late 2020 there were several highly effective vaccines that had been developed across the globe. Yet, despite rising hopes, no scientific miracle seems likely to end this pandemic with ease, just as none emerged in 1918–19.

The causes for pessimism are many: despite modern medical knowledge and a robust public health infrastructure, in fall 2021 the United States tragically surpassed the 675,000 estimated total flu deaths in the 1918–19 pandemic (models suggest the United States will reach one million cumulative COVID-19 deaths early in 2022); too few are being or have been vaccinated, particularly among marginalized groups and the young, in a process that has taken longer than anticipated; in non-industrial, non-Western, non-urban, and less affluent areas, vaccine access had been woeful. Deaths and serious long-term effects that might have been curtailed have not been. Some in the United States and Europe now refer to this as a “pandemic of the unvaccinated,” with serious illness and deaths largely located in populations that have not “had the shot.” The numbers of unvaccinated as well as a vocal but relatively small group of so-called anti-vaxxers, often spreading misinformation and protesting for their individual rights not to be vaccinated, as well as to go unmasked, remains sufficient enough in most places across the United States that curtailing COVID-19 spread has been nearly impossible. Political affiliations and affinities have politicized the pandemic such that science, access, and persuasion have not worked to achieve mass vaccination approaching herd immunity. And it has taken a long time to test the efficacy and safety of vaccines for children under twelve, making the resumption of school, social life, and work all the harder given the large numbers of at-risk people in populations worldwide.

In the United States, more than virtually anywhere else in the world, public health responses to the COVID-19 virus were politicized in new ways, weaponized to reject public health measures from closures policies and social distancing to mask and vaccine mandates. This stands in stark contrast to the 1918–19 flu pandemic, when opposition to public health interventions did not map on neatly to party or region. And this, in turn, has undermined national, state, and local public health efforts to ameliorate suffering and slow as well as prevent infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. Yes, there were pockets of anti-mask and anti-closure policy activism in 1918–19—most famously in the “masked city” of San Francisco with the Anti-Mask League of several thousand people in early 1919, but there was nothing then that resembles what we have witnessed in the highly partisan, organized pushback, protests, and propaganda of 2020–21. The wartime context in 1918 had generated a sort of patriotic language and push for homogeneity that, however problematic, also pressured citizens to conform to public health measures—casting those who rejected wearing masks as “mask slackers,” just as those who dodged the draft for World War I had been labeled and castigated as “draft slackers.”

At the beginning of this pandemic, even for the most expert epidemiologists and scholars of pandemics, it seemed unthinkable that total reported deaths in the United States from COVID-19 would exceed those from the 1918–19 flu pandemic (estimated to be roughly 675,000); that tragic result now will have been long since exceeded by the time this article is published. At the outset of the pandemic in early 2020, many nations and groups had already implemented proactive non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to slow or stop the spread are now being ravaged by new variants of the virus. The 1918–19 flu pandemic was characterized by several unique factors that are quite different from our recent pandemic experience. Two stand out: the flu, particularly in the fall 1918 deadly second wave, disproportionately impacted the healthiest in the population, with at least half of all those killed coming from the eighteen to forty-five age range; and, because it spread so fast and incubated so rapidly (one to four days on average), it burned through populations quickly and brutally. By most social, political, economic, and medical measures, the flu faded into the endemic form of the seasonal flu by 1920–21. People were still infected and dying in large numbers but nowhere near the catastrophic suffering of fall 1918 (in October 1918 alone nearly 200,000 Americans died). So, to many of us who have studied the pandemic of over one hundred years ago, one sad comparison is gradually becoming a reality: it now appears that the coronavirus pandemic, along with public health measures, political and social battles, suffering, and loss, may be with us for longer than the flu was deemed an epidemic in its day. It is clear that, as with the flu in the 1918–19, new variants (be they more or less deadly or infectious) are likely to change the trajectory of this pandemic. Given that insight, an important lesson of past pandemics and their aftermaths is that we can expect the unexpected and therefore should be as vigilant as possible.

As the 1918 influenza pandemic gradually transitioned to become an endemic disease, this shift was reflected in both public health policy and social response to the virus. The flu remained deadly and contagious, but public health interventions lessened in duration and severity. These were relatively short-lived in the fall and winter of 1918–19. Over the following years, public health measures came and went, often pushed by special interests, but starting roughly after the winter season of 1920, when a fourth wave was more deadly than either the first or third waves, influenza became something to be managed and weathered without resorting to emergency public health measures. It became, in short, the “seasonal” flu as we know it, which is the sort of historical observation that prompts many today to ask such deceptively simple questions as the following:

When is a pandemic over? And what comes after a pandemic? Why is it that deadly pathogens seem to bring out the best and worst in us? How do pandemics impact society and have lasting effects?

Such questions helped to generate this roundtable. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread aggressively in the spring of 2020, the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era assembled a roundtable, bringing together scholars from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to talk about how we can think about and teach the history of the 1918–19 pandemic in this current age of COVID-19. Here we build on the work of that earlier roundtable, “Reconsidering the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic in the Age of COVID-19.” In this roundtable we think about how we can understand the effects of the flu on the world at the end of the 1910s. And we consider what effects, if any, that pandemic had in the following decades and into the present.

Our aim for this conversation is ambitious. We hope to have a wide-ranging discussion across eras, nations, peoples, and groups, using numerous lenses of analysis. We want to consider the ways in which the study of the early twentieth century continues to inform our understanding of the world that we live in today. In the case of this roundtable, drawing on the expertise of the scholars involved, we focus especially on religion, inequality, immigration, race and racism, urban history, politics, and comparative international perspectives, as well as themes and insights useful to teaching the 1918–19 pandemic in light of COVID-19.

As before, we came together because we have a sense that a great number of those who work in history and allied disciplines, at colleges and universities, and at the K–12 level at the K-12 level will be continue to teach and think deeply about the flu pandemic. We also aspire for this roundtable to be accessible to a wider public eager to learn more about the legacies of the 1918–19 flu pandemic and to consider how lessons from the past pandemic can help us better understand and navigate the challenges we face today, both in the United States and around the world.

What follows is an edited and annotated version of a conversation that took place over email in summer and into the early fall of 2021. The roundtable is divided into three sections. We start our conversation using our current experiences as a lense through which to reflect on the events in 1918–19. The second section turns to look at “what came next” and the immediate and near-term aftermath(s) of the flu pandemic. The third and final section opens up more to take in the big picture and longer-term consequences and legacies of the 1918–19 pandemic as they have helped to shape the present and provide insights for the future. In this concluding section we also evaluate what we can know from the historical record about a pandemic and the sorts of sources and approaches that are most useful as well as misleading.

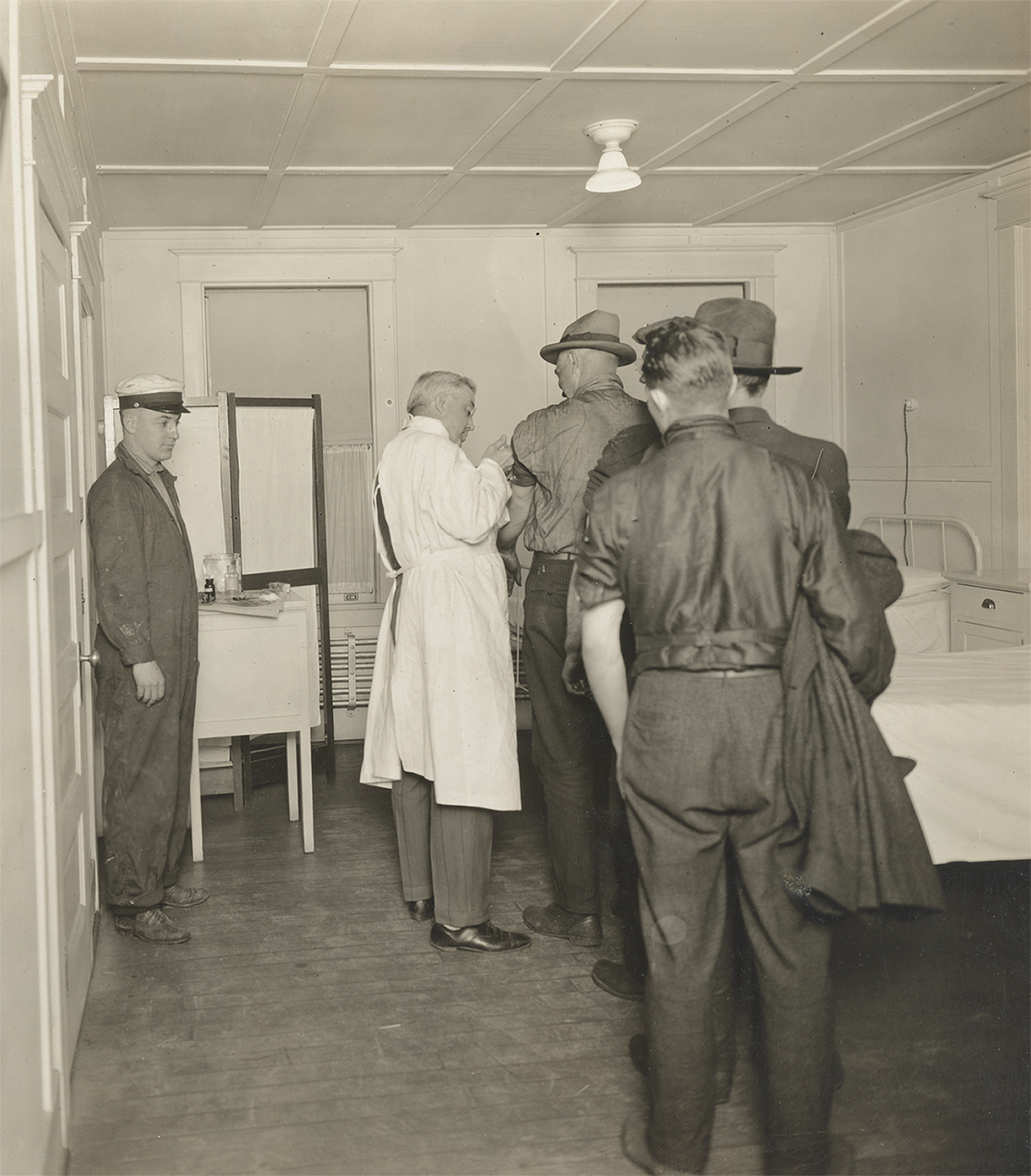

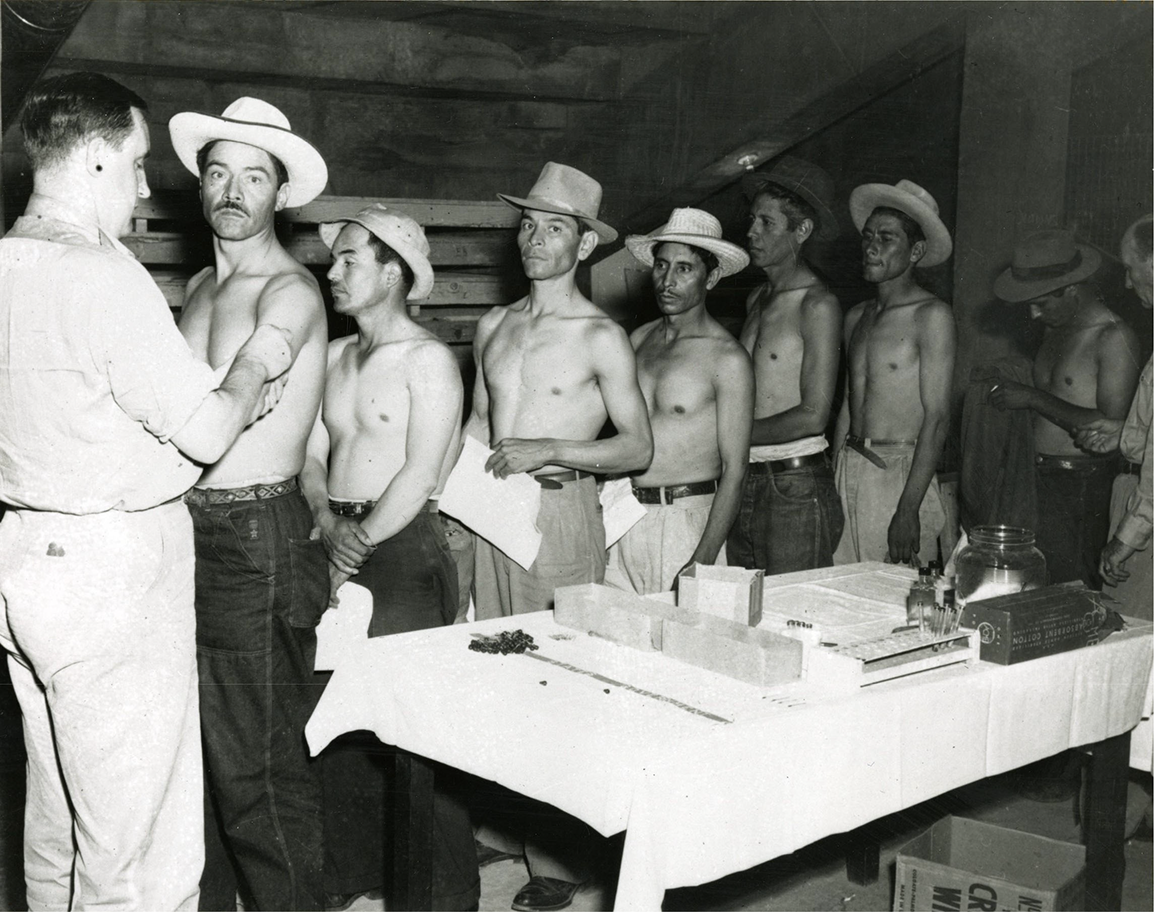

Image 1. “Fighting Influenza in Seattle. Flu Serum Injection, Seattle, Washington,” 1918, Record Group 165 (Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, 1860 – 1952), Series American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs, 1917 – 1918, File Medical Department – Influenza Epidemic 1918, National Archives Identifier: 45499307, Local Identifier: 165-WW-269B-9, National Archives, College Park, MD, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/45499307 (accessed Nov. 2, 2021).

SECTION I: Returning to 1918–19 While Living Through COVID

Christopher McKnight Nichols (CMN): As a scholar who has studied, written, and taught a lot about the 1918–19 flu pandemic, I am struck by how my views about that pandemic have changed in subtle ways by living through nearly two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tom, I’d like to begin with you given all the time you have devoted to researching, teaching, and educating wider publics about the 1918–19 pandemic. How has living through this pandemic changed how you think of the flu pandemic and what came after? To begin our conversation, I hoped you might address what themes you find are most useful in making sense of the complicated history of the 1918 flu pandemic, its effects, and its long-term ramifications?

E. Tomas Ewing (TE): In June 2021, the United States death toll from COVID exceeded 600,000.Footnote 2 These deaths had occurred in approximately sixteen months, beginning in late February 2020. The peak of the deaths occurred in January 2021, with an average of more than three thousand people dying each day from this disease. By late spring 2021, the death rate had decreased significantly, due to widespread vaccinations, but officials were warning that new variants posed threats to the significant minority of the population that remained unvaccinated.

The remarkable toll, 600,000 deaths, had a particular resonance for the history of American epidemics. The best estimate for the number of deaths in the 1918–19 epidemic in the United States is 675,000, as measured by the combined deaths from influenza and pneumonia from fall 1918 to spring 1919.Footnote 3 The number was calculated based on vital statistics reported by the U.S. Census for registration states, with estimates of the likely numbers from states not included in the registration totals. Given that pneumonia was one of the leading causes of deaths in the United States, causing approximately 100,000 deaths each year, the number of excess deaths from these two causes due to the epidemic was probably closer to 600,000, the current total of deaths from COVID-19. Of course, the United States population in 2020 is approximately three times larger than in 1918, so the death rate from COVID-19 is one-third of the death rate recorded during this early epidemic.

The relative impact of the 1918–19 and 2020–21 epidemics have been central to my thinking, writing, and teaching about COVID-19 since it first appeared in late winter 2020. My first public attempt to bring a historical perspective to COVID-19 was given a headline that I now regret: “The First American Cases of Coronavirus Shouldn’t Spark a Panic.”Footnote 4 This article drew upon the historical example of the first American cases of the so-called Russian flu in December 1889 to anticipate similar excitement about the first cases of the novel coronavirus spreading rapidly in Asia and Europe. In this article, I argued that the common pattern of exaggerated attention to the first “local cases” can heighten anxiety and possibly spread unjustified panic. I outlined several lessons from this historical example that should inform responses to COVID-19: the need to be critical consumers of news about cases, the importance of seeking reliable guidance about public health measures, and the imperative to foster empathy for individual victims.

In retrospect, of course, I completely underestimated the actual trajectory of COVID-19 in the United States. If I had anticipated in February 2020 that more than 600,000 Americans would die from this disease in the coming year, I probably would have made a different argument. Instead of cautioning against an overreaction to early reports of COVID cases, I would have emphasized the grave dangers of disregarding public health measures such as social distancing, mask wearing, and restrictions on gatherings in public indoor spaces. In other words, I wish that I had made a scholarly argument about the need to panic, rather than citing historical examples that suggested panic was itself the problem. Rereading this essay more than a year, and hundreds of thousands of deaths later, is an important caution about using historical analogies to make sense of current events and future trajectories.

The muted recognition of the milestone of 600,000 deaths provides some indications of how the toll from this pandemic will be remembered in the future. When the United States reached the milestone of 100,000 deaths in late-May 2020, the print version of the New York Times filled the front page with names of individual victims, with more names on the inside pages. The single headline on the entire page read, “U.S. Deaths Near 100,000, An Incalculable Loss.”Footnote 5 As the United States reached “the toll” of half a million COVID deaths in late February 2021, the New York Times published a graphic on the front page, with a single dot representing each death. The widely scattered dots at the top of the graphic became increasingly concentrated in spring 2020, as the epidemic swept New York City and other localities. For several months, the dots became less concentrated, but at the bottom of the graphic the concentration increased, as the totals rose quickly in the deadliest stages of the pandemic.

By contrast, the milestone of 600,000 deaths prompted more restrained coverage in the same newspaper.Footnote 6 The pace of deaths had slowed, as it took more than four months to reach this milestone, whereas the United States recorded 200,000 deaths in just over two months in the winter of 2020–21. In addition, the urgency associated with the early stages of the epidemic has gradually dissipated, as local, state, and federal agencies have relaxed rules and regulations for personal behavior. The milestone of 600,000 deaths was used by President Biden to urge more Americans to take the most accessible step to end the pandemic: “Please get vaccinated as soon as possible. We’ve had enough pain.”

The diminishing attention to the accumulating toll of the epidemic provides some guidance for anticipating how this experience will be remembered in the future. Rather than using these milestones to mobilize public opinion around the need to sustain these lessons into the future, health officials, for understandable reasons, are looking for ways to reassure the public that the danger is receding. It seems likely that as the epidemic fades into the past, it may have little long-term impact on our thinking about the need for modifying our collective behavior in the face of serious threats to public health. While this outcome is predictable, it is vital that we remember the lessons of this pandemic and use this experience to shape responses to future threats to public health.

Maddalena Marinari (MM): The impact of COVID-19 in the United States looks a lot different when seen through the eyes of immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. While the pandemic appears to be receding across much of the country, it is still taking a huge toll among these communities. As of July 7, ICE detention centers, for example, still routinely have COVID-19 outbreaks because of the low vaccination rates among its populations and the challenges of enforcing public health measures to contain it.Footnote 7 My involvement in documenting the impact of COVID-19 on immigrants and refugees was, in part, a response to the discovery in the spring of 2020 of how little immigration historians had written about the impact of the 1918 flu pandemic on immigrants in the United States.Footnote 8 I found this surprising since, as historian Erika Lee has demonstrated, one of the most persistent myths about immigrants that developed at the end of the nineteenth century and that persists to this day is that migrants bring diseases that threaten immigrant-receiving countries.Footnote 9

By the time the 1918 flu pandemic began, immigrants had already been the subject of large-scale campaigns blaming them for all sorts of diseases. Authorities often justified quarantines, border enforcement, and segregation by citing public health concerns that distinguished between desirable healthy citizens and undesirable diseased outsiders. Starting at the beginning of the twentieth century, many Americans regularly accused Mexicans of being responsible for outbreaks of typhus, plague, and smallpox and of carrying vermin. The Bath Riots of 1917 at the Santa Fe Bridge between El Paso, Texas, and Juárez, Mexico, were in part a response to the immigration authorities’ practice, at the direction of the U.S. Public Health Service, of requiring Mexican migrants entering the United States to strip naked and be disinfected with various chemical agents, including gasoline, kerosene, sulfuric acid, and Zyklon B.

Many Americans also blamed immigrants for outbreaks throughout the country well before 1918. During an outbreak of the bubonic plague in San Francisco in 1900, many blamed Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans and racialized them as a particularly dangerous public health menace. The hysteria led authorities to quarantine Chinatown and halt any movement of people and goods in and out of it. Neighboring states threatened to close their borders. In 1916, immigration authorities washed arriving Mexican migrants’ clothes in kerosene while they showered because they believed that Mexicans were responsible for a typhus outbreak in the United States, even though Mexicans had only been associated with four cases in the previous months. Also in 1916, Italians, the largest immigrant group at the time, came under attack during a polio epidemic that swept the East Coast. While some public health officials in New York City distributed pamphlets printed in Italian to educate about risky health behaviors, others blamed Italian immigrants for spreading the disease and cited their sociability as a broader public health threat. Lastly, many Americans often referred to tuberculosis as the “Jewish Disease” and blamed it on Jewish immigrants because of their supposedly unhealthy lifestyle even though Jewish communities had lower rates of tuberculosis than other communities in the United States. While much of this history is well known to scholars of U.S. immigration, living through the COVID-19 pandemic has made me realize how much we still don’t know about this longer history of identifying foreigners with diseases and of racializing immigrants of color as particularly dangerous threats to public health.

We know even less about what happened to immigrants and immigrant communities during the 1918 flu pandemic and how this experience affected their lives afterward. Many have argued that because over half a million foreign-born soldiers from forty-six different nationalities served in the U.S. military and because influenza took such a heavy toll on the armed forces in the middle of a global war, xenophobes found it hard to blame the newcomers for the pandemic. Still, there were some expressions of what historian Alan Kraut has called medicalized nativism, stigmatization based on a perceived association with disease.Footnote 10 In Denver, for example, Italians were accused of spreading the pandemic because of their unsanitary living conditions and their supposed inability to follow rules.

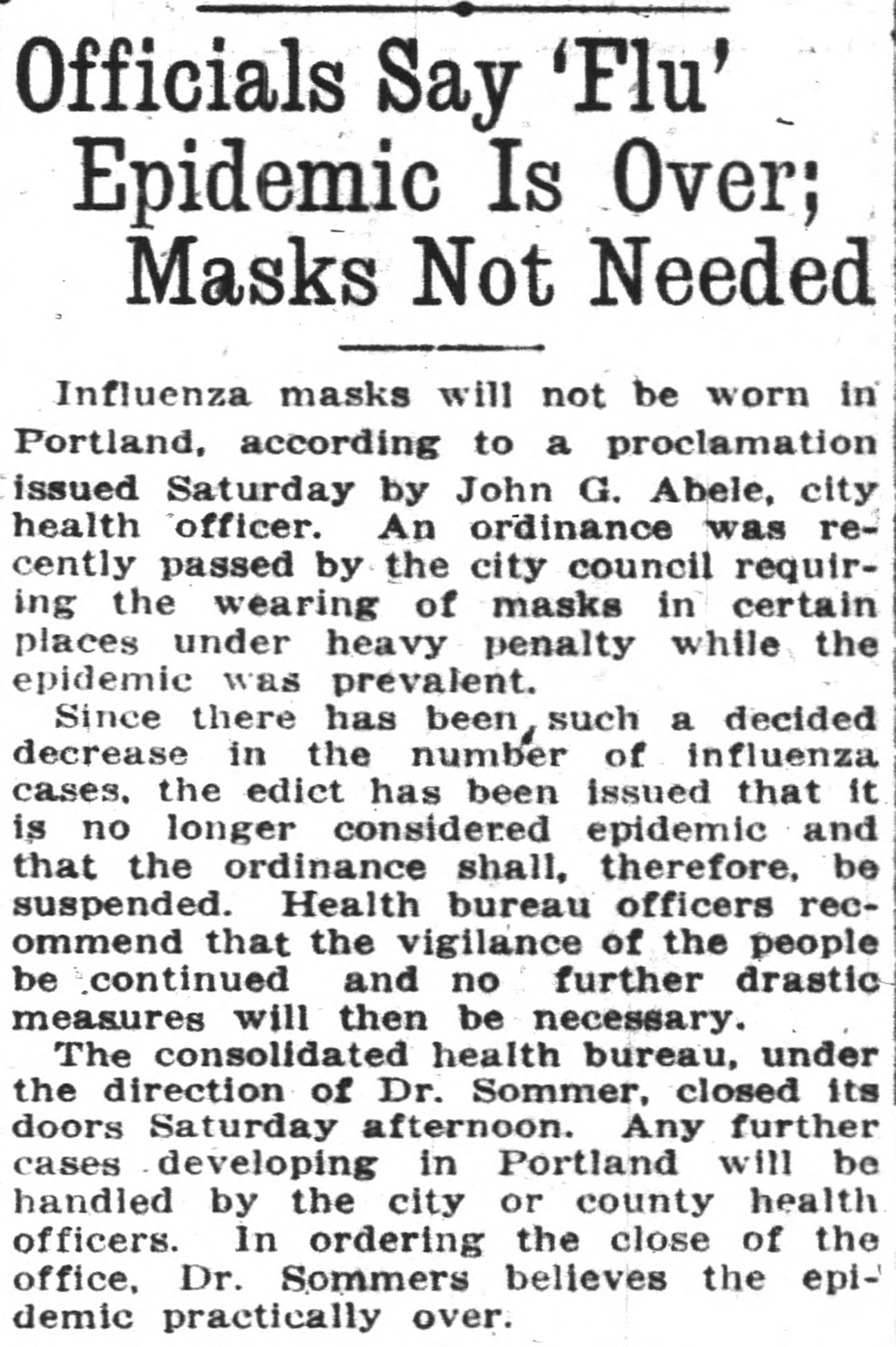

Image 2. United States Public Health Service, “Public Health Service Physicians on Ellis Island in New York Harbor Check the Eyes of Immigrants for Signs of Trachoma,” 1910, HMD Collection PP55755 no. 85 box PHS sub, US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101448074-img (accessed Nov. 2, 2021).

Over the past year, I have had several conversations with fellow immigration historians about how difficult it is to imagine that any of us would study the 1910s and the 2020s without taking into account how the 1918 flu and COVID-19 pandemics affected the lives of immigrants and refugees. When it comes to the 1918 flu pandemic, drawing from my research on the current pandemic, I have often wondered about how many in immigrant communities resorted to home-made remedies because they had little to no access to any kind of health care or because they feared scapegoating or retaliation. I have wondered about how many of them went to work sick because they couldn’t afford to stay home, hid the sick and dead to avoid blame and even violence, or felt abandoned and isolated in their immigrant neighborhoods. Thinking about the aftermath, was the pandemic one of the reasons why immigrant workers went on strike in 1919? On the flip side, how much did the 1918 pandemic influence the drafting and passage of the 1921 and 1924 immigration acts, two of the most draconian immigrations laws in U.S. history? Did eugenicists, many of whom played a critical role in influencing many Americans’ views of immigrants and immigration, use the pandemic to bolster their claims about the public health threat that immigrants posed to the survival of the nation?

Looking ahead at how immigration historians will study the current pandemic, I would hope that they would look closely at how the pandemic has reshaped U.S. immigration policy, challenged ideas of citizenship and belonging among Americans and within immigrant communities alike, and has fueled a resurgence of xenophobic attacks and nativist rhetoric against immigrants. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has also generated a critical debate about health care access and equity and created opportunities for the emergence of multi-racial coalitions to challenge systemic racism. It will be some time before we understand the full impact of the pandemic on immigrant and refugee communities. Given the uneven collection of public health data around race, ethnicity, and immigration status in relation to the pandemic, there is a serious risk that we many never know if we don’t start preserving their stories now.

CMN: I’d like to shift our focus slightly to ask Healan about her response, and specifically to ask the following: What do you see as the historical dimensions of the role of religion in a time of pandemic such as 1918 with the flu and 2020 with COVID-19?

K. Healan Gaston (KHG): One theme common to the contemporary pandemic and the influenza outbreak of 1918–19 is what the Christian Century recently called “the problem of being the church without being together.” How can religious institutions sustain themselves and support their members’ spiritual lives if they cannot host large, in-person gatherings? What kinds of substitutes, if any, can be found for the conventional forms of worship and devotion? How will the disruptions required to prevent the spread of disease reshape religion, in both its public and private dimensions? Such questions, so pressing in 1918–19, have now reemerged, but within a very different cultural and institutional context.

An especially important point of contrast involves the responses of religious leaders to attempts by public health authorities to minimize collective forms of worship in order to prevent the spread of disease. The evidence seems to suggest that religious institutions in 1918–19 were more likely to heed such injunctions—or perhaps less likely to express their dissent publicly—than they are amid the current crisis, when America’s culture wars have fostered widespread distrust of government agencies. This is especially true among evangelical Christians, who have often criticized or simply ignored calls to close their churches’ doors. At the same time, the transition from an era of print media to a digital age has dramatically expanded the possibility for new forms of religious practice by allowing for virtual services. Despite their manifest limits, Zoom and its equivalents have enabled forms of continuity with pre-pandemic patterns that could not be sustained a century ago.

Even so, the hope that religious observance would continue apace was as strong during the influenza epidemic as it is today. Some religious leaders expressed fear that these disruptions would cause spiritual harm, but they generally backed public health measures, often in newspaper articles featuring comments from religious leaders from across the denominational spectrum. The first line of one such article published in Baltimore captured the spirit of the moment in its description of the American people: “Churchless and gasolineless, but, thank Heaven, not Godless!” Although the article lamented the closure of the churches, it simultaneously suggested—in a potent and familiar narrative touting the unique efficacy of voluntarily chosen religion in the United States—that this unprecedented step may have “actually strengthened the religious life of the city.”Footnote 11

Then, as now, commentators insisted that the unprecedented closure of the nation’s religious institutions would not silence the “prayers and hymns of praise, supplication and divine judgment” from the people, which would “ascend from under the rooftree at many a household.” Rather than Zoom meetings, however, such figures looked to private forms of worship in the home as the logical substitute for collective gatherings. As the Los Angeles Times reported, “the preachers believe that the temporary prohibition of the assemblage of people for religious meetings will have the tendency to revive practical home worship, which has become a sadly-neglected function in religious life.”Footnote 12 To encourage home worship, religious institutions relied on local newspapers, denominational publications, and newsletters. One Lutheran pastor even dispatched Boy Scouts from his congregation to each household with precise instructions for the family altar.

Some of the best evidence of the use of print media to encourage and guide home worship comes from Black newspapers, wherein pastors often reached out directly to their congregations. For instance, Frederick H. Butler of Philadelphia’s Zoar Methodist Episcopal Church communicated directly with his parishioners when their church doors closed. “If the ban is not lifted by this coming Sunday,” Butler instructed his flock, “continue the home devotions, not forgetting the confessions of our sins and the plea for pardon; the bereaved families, the sick and suffering and the removal of the malady now afflicting us. And when we are delivered, let none of us again remove or discontinue the family altar.”Footnote 13

Even those Black leaders who worried about the financial well-being of their institutions nevertheless insisted that the pandemic would not impact their congregants’ spiritual health: “The effect of the Epidemic has been severely felt by the churches because the doors have been closed and the members have not been able to assemble for worship,” declared U. G. Leeper. “This may greatly affect the church financially but should not affect the members spiritually. God can be reached anywhere for He is a present help in the time of need.”Footnote 14

Some Black leaders even argued that the pandemic would strengthen the spiritual fiber of family members who could now spend more time together: “The people are enjoying their own Bible the few Sundays that they have not been able to go to church,” observed a pastor. “One little boy said he wanted to hear his mother read about Jesus. Is it the same we learn in our school? This boy is eight years old; his mother is one of the leading church members. She never had time to call her boy and read the Bible to him. This is a good time to get back to the family altar.”Footnote 15

White leaders echoed these sentiments, and some even claimed that the closure had fostered something of a “religious awakening.” In this telling, the disruptions to usual patterns had facilitated “the establishment of new bonds within the family circle, and the beginning of a custom, so wholesome and inspiring that it will be continued even after the churches again throw open their doors and regular services are resumed. … Religious impulses long dormant were stirred and quickened. Indifference gave way to revered meditation. Churchless: yes. Godless? A thousand times no!”Footnote 16

We still have much to learn about how the 1918–19 influenza epidemic reshaped religion, in both its institutional and intimate forms, during the 1920s and beyond. That said, it seems likely that the changes in our own time will differ in significant ways. The possibilities created by the internet have shifted questions about religion’s future onto new terrain. Across various domains, in fact, the need for physical, spatially grounded institutions has been called into question. Brick-and-mortar stores had already faced major challenges prior to 2020; now we are also asking whether we might be able to do without other familiar entities, such as office buildings. A similar set of questions swirls around religious institutions. What is the quality of online worship? Are people more likely to attend religious services if they do not need to commute to them? If virtual services continue, might the tendency of young people to drift away from religious affiliations be reversed? More generally, how will the religious landscape change now that virtual forms of worship can connect people across vast geographical distances, from different parts of the country and even around the world? Will religious organizations find ways of appealing to individuals and families whose views clash with those of the brick-and-mortar institutions in their own geographical locales? The information age presents a series of possible futures that could not have been imagined at the time of the influenza epidemic, even as the imperative to find substitutes for in-person gatherings has recurred.

CMN: David, I’d like to pivot from Healan’s emphasis on the institutional and intimate in the reshaping of religion by the pandemic to explore another crucial lens through which this moment has surprising resonances with 1918 and to the Progressive Era more broadly: inequality. Has living through this pandemic caused you to reconsider inequality—defined as you see it—during the pandemic one hundred years ago? If so, in what ways?

David Huyssen (DH): If anything, living through this pandemic has reinforced my view of economic inequality’s consolidation and recrudescence heading into the 1920s. On the other hand, it has made me cautiously optimistic, by comparison, about the possibilities for redressing long-growing inequalities, including economic inequality, in our own moment—at least on the domestic front.

Both these conclusions may seem counterintuitive in purely economic terms, which is why they offer an object lesson in how misleading economic data can be, absent broader social and political context. Thomas Piketty has shown that the portion of national income accruing to the top decile in the United States actually fell for several years during and immediately after World War I. Both income and wealth inequality, therefore, were shrinking in aggregate terms during the most intense period of the 1918 flu pandemic.

Today, these forms of inequality are exploding, with clear causal connections to the coronavirus crisis. Job and income loss from lockdowns have devastated millions of low-income households. This has led to shocking growth in food insecurity. Census data from January 2021 indicated that twenty-four million adults—more than one in ten in the United States—had not had enough to eat sometimes or often in the previous week. This number had risen by five million from the previous August. Meanwhile the rich are having a Scrooge McDuck moment. Recent Forbes data shows that the wealth gained by U.S. billionaires during the sixteen months following the first lockdown in March 2020 totaled nearly two trillion dollars, a third of their wealth growth since 1990.Footnote 17 By some measures, wealth inequality today has surpassed all U.S. historical highs.

So why was inequality falling then, and rising now? As ever, economic indices are far more accurate as records of past political choices than as indications of those to come. By the time the flu began taking its toll in 1918, the moment for redistributive political action combating inequality had effectively passed. The flu arrived during the second term of a Democratic president who had pledged to address imbalances of wealth and power, and had already been pursuing an ostensibly progressive, interventionist economic agenda for years. Woodrow Wilson had overseen the introduction of a graduated income tax; established the Federal Reserve to reduce dependence on private finance for national financial stability and promote “maximum employment”; created the Federal Trade Commission, which enforced the anti-monopolistic Clayton Antitrust Act; supported the outlawing of child labor (overruled by the Supreme Court shortly thereafter); and endorsed the eight-hour day for railroad employees, among other labor-friendly policies.

As many U.S. labor historians have shown, the U.S. entrance into World War I took this interventionist agenda further still. The requirements of war production impelled state intervention in, and systematization of certain industries, even leading to the effective nationalization of the railroads. After decades of violent industrial warfare and bitter strikes, Wilson’s War Industries Board and National War Labor Board seemed to augur a new age of state mediation in which labor might have a real voice. The U.S. government actually began settling some active labor disputes by forcing employers to raise wages. Many workers—particularly white men in craft unions—saw real benefits in pay and conditions. Hence the surface reduction in income and wealth inequality at the end of the 1910s.

But the flu would also exacerbate powerful forces that cut off such tentative inroads against economic inequality. The pandemic arrived during Jim Crow segregation’s historical high-water mark, wartime jingoism’s exacerbation of xenophobia, and an intensification of both state and non-state suppression—often violent and vicious—of radical working-class collective politics. Wilson had overseen the segregation of federal government employment and (despite personal ambivalence on restrictive immigration policy) whipped up xenophobic fervor through war propaganda. The crystallization of anti-immigrant politics during the war, combined with long-standing xenophobic and racist associations between non-white bodies and disease that Maddalena has already noted, meant that the 1918 flu would have splintered working-class solidarity rather than forging it.

The bitterness of such suffering could only have magnified mutual recrimination within the U.S. working class over the war itself. In an attempt to institutionalize labor as a junior partner within the U.S. government, the president of the conservative craft unionist American Federation of Labor, Samuel Gompers, had made a devil’s bargain by providing a no-strike pledge for the duration of the war and supporting the repression of anti-war elements within the labor camp whom he saw as rivals. These included industrial unionists, syndicalists, anarchists, and Socialists—groups whose activism had been crucial in pushing the Democratic Party toward its anti-inequality measures in the first place. If the war briefly consolidated the immediate effects of such measures, it also invited the political repression of such radicals, especially after the Russian Revolution inflamed American anti-communism. Wilson’s signing of the Espionage and Sedition Acts in 1917 and 1918 codified that repression, and A. Mitchell Palmer’s Department of Justice realized it further through early 1921.

The flu thus ravaged a working class already riven by race, gender, national origin, questions of organizational strategy, and—as Jennifer Fronc has shown—facing an increasingly institutionalized apparatus of state surveillance and repression. Although some laboring Americans had seen benefits from Wilson’s economic policies during the war, they would encounter postwar inflation’s erosion of improvements in pay and availability of work without recourse to the kind of concerted radical collective action that had buoyed them before the war. Disproportionately decimated by the flu, harried by the state, politically betrayed by the mainstream labor movement, and facing employers unleashed from wartime state controls amidst a frenzy of popular anti-radicalism, they would suffer a further explosion of inequality for most of the ensuing decade.

By contrast—and despite the ongoing spike in economic inequality’s indicators—our moment presents a very different political and ideological context. As many other contributors have pointed out, the 1918 flu prefigured the ongoing pandemic in its disproportionate effects on already marginalized and intersecting populations of non-white, immigrant, and working-class people. Widespread awareness of this disproportionate impact in our own moment has helped to spur, at least initially, an intensification of collective social protest and electoral activity demanding urgent and long-delayed action on various forms of inequality.

At the same time, a real sense of universally (albeit not equally) shared hardship has opened up new political possibilities in the United States for coalition building to combat inequality of all kinds. On the prosaic level of redistribution, COVID-19’s sudden devastation of employment generated an unprecedented flurry of applications for unemployment relief in 2020—tens of millions over just a few months—(re-)normalizing the idea that the state should step into the breach for ordinary Americans in moments of economic hardship. Is it coincidental that the Senate runoff campaigns in Georgia, which won the Democrats nominal control of the upper chamber, hinged on the promise of checks from the U.S. Treasury to offset economic damage from the pandemic? Joe Biden’s subsequent $1.9 trillion-dollar recovery package, passed in March 2021 with support from 70% of the American public, contained some of the most aggressive anti-poverty measures since the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 18

It is difficult to imagine much of this happening without either the brute realities of the pandemic or the Republican administration’s abysmal management of them.

CMN: Finally, I hoped to turn to you, Alan, as we broaden out to conclude these opening responses. How has living through this pandemic changed how you think about the flu pandemic, and are there any themes and approaches that haven’t been mentioned yet that you think are most important for us to consider as move next toward examining more closely the aftermath of that pandemic?

Alan Lessoff (AL): I’m operating on the assumption that the coronavirus pandemic of 2019–21 (or ‘22 or ‘23 …) will have a more tangible presence over the next decade than the 1918–19 influenza pandemic had in the 1920s, even though that pandemic was, in relative terms, more devastating. At least this was true as of August 2021, when driven by the Delta variant, coronavirus was accelerating its misery and confusion both in the United States and around the world. Can any of us imagine an analogous roundtable of historians a century from now wondering why societies in different parts of the world during the latter 2020s didn’t experience more argument, turmoil, and conflict as fallout from COVID-19? They might, by contrast, ask why COVID-19 preoccupied the post-pandemic years so much. Nearly every historical treatment of influenza’s aftermath starts from the observation that the response in the 1920s–30s was muted, tacit, and hard to trace, given the upheaval and misery of the event itself.

In framing the matter this way, I mean to differ guardedly from the picture of quickly “diminishing attention” that Tom offers in his last paragraph above. In saying that, I don’t mean to suggest that the aftermath of COVID will see the constructive public deliberation over public health policies and practices that Tom explains that we need. With luck, some of the political fallout of the pandemic might veer toward the reflection—of which David sees signs—on the social and economic disparities and tensions that the pandemic made manifest to anyone paying attention. As David likewise underscores, the pandemic itself worked to make the country’s social divisions more corrosive and more in need of a comprehensive social reform politics. Several features of the Joe Biden administration’s recovery package gave me hope as well, especially the child tax credit. [As I was revising these comments, the news was reporting worrisome signs that congressional Democrats might impose conditions that compromise the universal commitment we need to poor and working-class parents and children.] The political coalition that produced these initiatives is notoriously precarious. It is far from clear that this coalition will broaden and gain momentum.

In imagining what we are facing over the next few years, it’s worth mulling over some possible reasons that the influenza pandemic did not persist as an explicit focus of public discussion in the 1920s. Maddalena points to one likely reason: influenza reinforced rather than overturned a well-established, transnational discourse on disease, infection, uncleanliness, and sanitation, a discourse with myriad social and political implications already. Bubonic plague, to cite one of her examples, showed up off and on in the United States, but it swirled around the world in the 1800s, especially in Asia, an accompaniment to the worldwide swirling of people, which was in turn related to the geopolitics of European empire. The transnational character of Western public health discourse meant that these experiences on different continents shaped U.S. understanding of disease and its association with the migration of suspect or unwanted people. One could build similar accounts about malaria and yellow fever in Africa and the Americas. More directly evident in U.S. discussions in the decades before World War I were, as Maddalena also notes, tuberculosis, typhoid, typhus, polio, measles, and cholera, to name a few.

Later on, I’d like to come back to a number of other social, economic, and geopolitical contrasts between the 1920s and the 2020s. Beyond obvious, present-day factors such as information technology and the present-day institutional structure of medicine and public health around the world, these include the class, ethnic, and regional structures and cultures that characterized the urban-industrial system of the 1920s versus suburbanized, knowledge-and-service economies of the 2020s.

One would be more sanguine about the next decade if coronavirus were to appear in public discussion around the world as an environmental catastrophe, in the spirit of Alfred Crosby. That is, if it prompted more reflection and argument over the world-spanning environmental consequences of the current wave of capitalist globalization as well as the more geographically localized ecological turmoil that urbanization entails. But I don’t see this happening in the United States, Europe, China, or pretty much anywhere, except sporadically. Over the last eighteen months, commentators sometimes have drawn attention to the ways that pandemic manifests environmental degradation and has potential to exacerbate it. But overall, publics and governments around the world seem to be treating the pandemic as an immediate medical and policy problem, while the environmental disasters that accelerated even as the pandemic dominated attention represent long-term concerns to be dealt with later.

Until now, I guess, I’ve concentrated on the second part of Chris’s question, on major themes and approaches that assist in understanding the 1918 pandemic. To address the first part of the question, on the experience of living through a pandemic and its utility in understanding past pandemics, I’m not sure that we should let our experience with coronavirus alter our analysis of influenza and its aftermath in fundamental ways, at least not yet. There’s too much danger in that of a presentist telescoping that will distract us from issues that belong to our time more than to the past and that we need to focus on right now. Historical interpretation of the influenza has developed a lot in the decades since Crosby published the first edition of his book in 1976 and also since John Barry published The Great Influenza in 2004. Nancy Bristow’s American Pandemic, published in 2012, provides a fine overview of the influenza’s social history, ending with an analysis of why the public aftermath of that pandemic was so muted, even though the trauma shaped personal and family experience for decades. These are just a few prominent works already in print before coronavirus prompted a hurried new look at influenza. If we become too preoccupied with how what we have just gone through can prompt reinterpretation of 1918–19, we may well distort that episode by pulling the influenza pandemic too much out of the context of everything else that was going on in that era of world war, revolution, civil war, the collapse of empires, uprising against those empires that survived, ethnonational massacre, and population expulsion. We may also not have fresh eyes for the situation we are now in.

My own experiences over the last eighteen months have changed my outlook on that episode mainly in quiet, melancholy ways that might not stand up to systematic intellectualizing. Above all, it has caused me to reflect on what it means for history and society when millions of individuals, families, and small communities feel lonely in their struggles and suffering. Sometimes a key, underlying meaning of an event—even one as widespread and huge and tumultuous as a pandemic—might inhere in the ways that people experienced it as private turmoil and loss, the ways that they perceived it as upheaval in their own lives, as wreckage for their own family and their own aspirations. This isn’t an especially original point, nor one confined to how people experience and remember disease. There’s long been an undercurrent, for example, among military historians that takes of the side of novelists, playwrights, and memoirists who depict even the collective, public destruction of warfare as having intensely personal meaning for those caught up in it.

Here I am doing what I just warned against: drawing too quick a connection between what I see around me and the mood that prevailed in the influenza’s aftermath. Anyway, for a host of reasons we could examine, people in North America and around the world apparently put the most emphasis on the pain and loss that the flu caused in their own lives, among their own circle of loved ones and friends, and to their own plans and goals. “Though Americans’ public culture embraced an optimistic narrative of recovery and opportunity,” Bristow explains, private narratives “recalled the pain, the losses, and the dislocation,” that influenza left behind. It’s certainly laudable that we want to talk now about what we can learn in a policy and political sense from a public health disaster a century ago. Yet, I think our discussions should also treat as historically significant—as worthy of deference even—that fact that so many people then turned away from public discussion of what they had gone through, that they turned inward about it, that they, as Bristow notes, “considered their own struggles.”Footnote 19

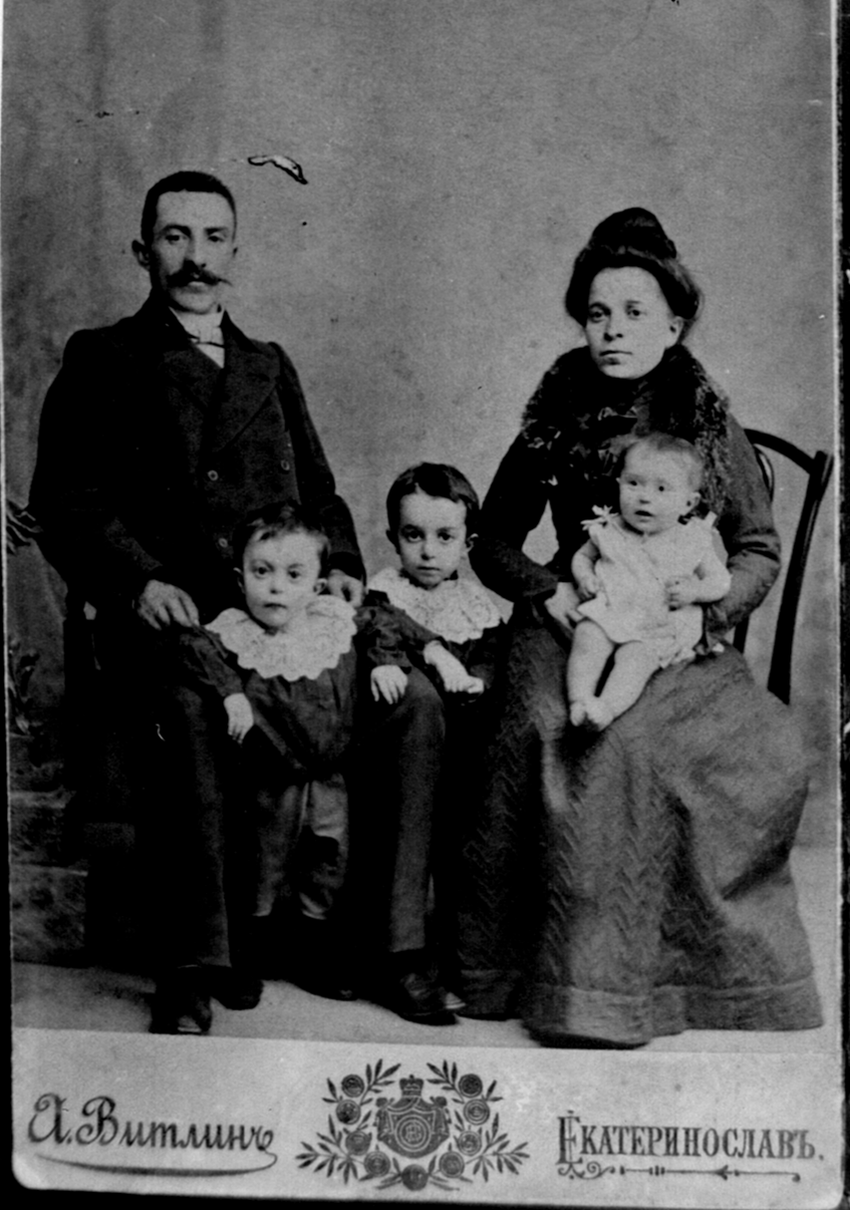

Image 3. “Officials Say ‘Flu’ Epidemic is Over; Masks not Needed.” Oregon Daily Journal [Portland], 10 February 1919, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn85042444/1919-02-10/ed-1/seq-5/ (accessed 2 November 2021).

SECTION II: Immediate Aftermath

CMN: In light of widespread vaccine access and reopening, but also ominous factors such as rising variant spread and infections, today many are asking: What came after the flu in 1918? When and how did that pandemic end and can we draw lines, straight or circuitous, to the events that followed? In other words, how did the 1918–19 influenza pandemic shape the events of the immediate years that followed, say from the 1920s through the 1930s?

AL: An epidemiologist or demographer can apply definitions and benchmarks to trace the end of the influenza pandemic. Publics and governmental institutions treated it as more or less over by mid-1920. Still, many who survived dealt with its effects over their lifetimes, which is especially poignant because of the flu’s virulence among young adults. Right now, we’re only beginning to wrestle with the breadth and meaning of the syndromes that we’re grouping together as “Long COVID.” Many of these cases also concern young adults, even people who did not seem badly affected by COVID when they had it initially.

On a sociocultural and social-psychological level, surely influenza had no clear end. It became, as Bristow and others have stressed, an enduring, quiet factor that showed up over decades in ways that might be hard to define or even identify clearly. To illustrate, I’d like to draw again on a theme introduced by Maddelena, applied to my own family story.

A prize possession in our family is a pair of portraits of two great-great grandfathers on my father’s side, painted from photographs but impressive nonetheless. One of these, Hyman Lessoff, emigrated from the present-day Ukraine early in the twentieth century, I think following his son, whom he had outlived by five years when Hyman died in Brockton, Massachusetts, in 1923. Hyman’s son, my great-grandfather Zalman Ber Lessoff, was born circa 1872 in or near the Ukrainian city of Dnipro. A Russian army veteran, Zalman Ber emigrated in early 1906 “because of the pogroms,” as my grandmother later wrote. According to his passport, he was accompanied by his wife, Rebecca Witken Lessoff, and four of their eventual seven children, including my grandfather Alexander and his twin brother Daniel, born in 1898. One family source Americanizes Zalman Ber’s name as Benjamin, while another calls him Charles Bernard. Family information also differs as to his occupation in his home country, but once in the United States, he worked for a bottle manufacturer and—like his son Alexander a few decades later—he became active in the Boston local of his AFL union.

Image 4. Zalman Ber (Benjamin) Lessoff, Rebecca Witken Lessoff, and their children: (left to right) Daniel, Alexander, and (probably) Reuben. The original photo was taken in Ukraine, c. 1904. Courtesy of Dr. Alan Lessoff.

My great-grandfather died in 1918, around age 46. No family document that I am aware of mentions what he died of. My grandfather recalled this as a profound event that left him and Daniel, both nineteen at the time, responsible for their mother and younger siblings. In the years before my grandfather died in 1985, my uncle (a scientist for the federal government) and I (a history PhD student) interviewed him at as much length as he could put up with. We asked him about as many aspects of his life as we could think of. But I don’t recall either of us asking how his father died. My daughter has continued with family histories that my uncle began but has not to date secured a death certificate for Zalman Ber Lessoff. She has, however, been able to document relatives on her mother’s side of the family—they lived in northern provinces of the Netherlands—who died in the influenza pandemic.

My partner, Katie, an anthropologist, has family stories about an older brother of her father and several other relatives who died in the flu. This was a Polish immigrant family drawn to Wyoming for railroad work. As with my family, the details aren’t nearly as pinned down as other elements of family history and lore. Maybe others in the roundtable could recount similar family stories. These stories are all the more moving because of the missing details.

The flu molded the lives and outlooks of our great-grandparents’ and our grandparents’ generations, aftereffects that endured into our parents’ generation. But it matters from the point of view of historical explanation that this influence hides underneath family lore, that the people involved pushed it into the background without fixing meanings to it that they talked about much. They only sporadically acknowledged how memories and regrets stayed with them. If I had known forty years ago what I know now, I surely would have prodded my grandfather more directly about his father and about the flu more generally. Such guiding and prompting might have introduced, however, the oral historian’s fallacy.

While public discussion of the flu was muted over the next decades, private and family references are everywhere. These are often direct and explicit but also often indirect or implied, as I’ve been suggesting. It would take patience and literary sensibility—along with skills of the cultural anthropologist and social psychologist—to identify and recount patterns in these references. Cultural history has sometimes succeeded in tracing such shifts in sensibility and expression that meant as much to society as more manifest cultural, political, or economic shifts. Given the probable tie between immigration and grief and longing in the influenza’s aftermath, my thoughts went toward what historians have traced with regard to related emotions with which immigrants struggled, such as homesickness and nostalgia.

As they do with the personal experience of war, literature and art might help direct historians toward sensibilities and outlooks that the influenza pandemic left behind. In English-speaking countries, as we know—and apparently in Western languages more generally—literary accounts of the flu are scattered by comparison, for sure, to tuberculosis, with its foundational presence in so much modern literature and art. Crosby and Bristow draw attention to Katherine Ann Porter, Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939); Porter also went through tuberculosis. Bristow also dwells upon my own favorite book about the part of Illinois where I’ve lived these past two decades: They Came Like Swallows (1937), by William Maxwell, the exquisite writer and editor originally from Lincoln, Illinois. The heart of the story is the event that Maxwell returned to throughout his long career as the shaping moment of his life: when as a child he recovered from the flu only to discover that his mother had died. The world, for the boy and his family, has a before and after. Warmth and light have gone, and the father—preoccupied and a little distant to begin—withdraws into himself in grief that he resists admitting. The loneliness that Maxwell evokes is the sentiment that I began with above. It’s a difficult sentiment for historians to maintain, even though so much of our work is solitary. For most of us, history is a way to reach out; it is about the social for most of us, which is why we’re at home with public or collective agendas and wary of the historical force of fragmentary, private experience. Disease often pushes people inward, as anyone who has struggled with serious illness knows.

MM: I agree with Alan that exploring people’s private lives probably holds the most promise for historians interested in studying the impact of the 1918 flu pandemic on daily lives and social relations. Immigration historians have only recently begun to explore the history of emotions when it comes to the immigrant experience. So far, they have focused on exploring how immigrants talked about love, belonging, and nostalgia. We know very little about how health crises shaped migrants’ lives, informed their migration plans, or affected their decisions to return home, settle permanently in the United States, or send for their families. We know more about how a renewed focus on public health converged with calls for stricter immigration laws after 1918.

If xenophobes had been hesitant to blame immigrants for the 1918 flu pandemic, they were not as reluctant to use public health concerns to justify their calls for immigration restriction, deportation, and segregation throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Beginning in 1920, critics of immigration regularly connected their calls for immigration restriction to public health. For example, Harry Laughlin, the superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office, agreed to serve as the eugenics expert for the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization as it considered further restrictive legislation. Representative Albert Johnson, the leading author of the 1924 Immigration Act, appointed him after Laughlin had testified before the committee to discuss his research on how eastern and southern Europe allegedly polluted the American gene pool.

These attacks culminated in the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, which expanded the ban on Asian immigration, introduced a national origins quota system to curtail immigration from eastern and southern Europe, and expanded several categories for exclusion and deportation. Less known are the act’s provisions on seamen amid fears that many of them left their boats upon arrival, remained in the country illegally, and spread diseases undetected. Much of the language of the 1924 act shows a preoccupation with the seamen’s health and their ability to bring in diseases. Seamen were the last remaining group of migrants who were not tightly regulated when it came to health inspections. After the pandemic of 1918, that was no longer an option. The act introduced a provision that stipulated a $1,000 fine to steamship companies for every seaman who failed to have a medical inspection, left the vessel before any required medical treatment, or failed to return home if rejected following a medical inspection. The connection between illegal entry and health remained a constant preoccupation throughout the 1920s. The Immigration Act of March 1929 made unlawful entry into the United States a misdemeanor for first-time offenders and a felony for those who repeated the act. The act had far-reaching consequences. The criminalization of unsanctioned entry empowered social and health-care workers and immigration authorities far from the borderlands to accelerate Mexican deportations and repatriation.

Mexican immigrants bore the brunt of medicalized nativism after the 1918 pandemic. As historian Natalia Molina has shown, health officials used public health concerns—constructed through complex comparisons with Asian Americans, African Americans, and whites—to demean, exploit, and ultimately define Mexicans as dangerous disease carriers. Although the U.S. government had recruited Mexican laborers to fill the labor shortage during World War I and southwest employers regularly employed Mexican migrants throughout the 1920s, they quickly redefined Mexican migrants as unwanted and diseased once the Great Depression began. Throughout the 1930s, immigration officials deported approximately a million Mexicans and Mexican Americans in part on the pretext that they carried diseases and could become public charges. Many Americans ignored the realities that they regularly suffered from disease and injury because of the lack of clean and safe working conditions.

The legacy of the medical nativism underlying these expulsions reverberates to this day. As of July 2021, U.S. border officials have carried out more than 900,000 expulsions of migrants since March 2020 under a Trump-era pandemic policy known as Title 42, a public health order issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which closed U.S. borders to “nonessential” travel indefinitely. Officially enacted to prevent the spread of the coronavirus in border patrol facilities and in the country overall, the policy allows for expulsions that circumvent regular immigration law and deprive migrants of the chance to seek asylum in the United States.

CMN: Maddalena’s comments here help to make a persuasive case that we should be thinking more in global and international historical terms. In that light, Tom, how do you assess the ways in which the 1918 influenza pandemic may have shaped the events of the immediate years and events that followed? And, if it isn’t adding too much, how might that shape your teaching?

TE: During the last eighteen months of the COVID-19 pandemic, I have often been asked why the history of the 1918–19 influenza pandemic is not more widely known and why it has not been learned by more students. In these discussions, I often admit that I didn’t teach about the “Spanish flu” prior to my becoming interested in this topic as a research question. I’ve taught many courses that cover this time period, including modern European history and the twentieth-century world, as well as more thematic topics on modern Russia and Germany, Europe in the interwar period, women’s history in the suffrage era, and the Russian Revolution. In this contribution to the roundtable, I will draw on my experience in teaching these courses to address the question of the significance of the 1918–19 pandemic in European and global history as well as the more-timely question of how living through the COVID-19 pandemic will shape my teaching of these courses in the future.

My first answer to the question of why I didn’t teach about the 1918–19 influenza pandemic is that too many other important events happened in this period of time. A short list of major topics covered in a European history course from 1917 to 1921 include the end of the world war, the peace settlement, the Russian Revolution, women’s suffrage, the efforts to establish a democratic Germany, and the creation of new nation-states in central and eastern Europe. In world history, this same period includes the disintegration of the Ottoman empire, the strengthening of European imperialism in Africa and the Middle East, American intervention in the European war and then renewed isolation, revolutions in East Asia and Latin America, and the early stages of anti-colonial movements, particularly in south and southeast Asia. As I review this list, even with the flexibility to set topics and determine timing (unlike those bound by a standard curriculum), I would have a difficult time omitting any of these topics from my courses in European and world history.

As I think about this question, however, I also realize that the omission of the 1918–19 pandemic reflects my underlying priorities in teaching, which are to emphasize topics that transform historical trajectories. More specifically, I prefer to teach topics that have a direct impact on future trajectories right through to the present. The end of the European War in November 1918, for example, leads to the peace settlement, the rise of dictators, the path to a second world war, the Holocaust, and the post-1945 world order that has direct implications for European unity. The Russian Revolution in 1917 and particularly the establishment of the Soviet Union from 1918 to 1921 led to the division between socialist and capitalist systems that dominated the second half of the twentieth century and persists in the continued struggle between democratic and authoritarian systems around the world. Women’s suffrage, first achieved in Russia and then in major democratic states in Europe and the United States, lays the foundation for decades of struggle over women’s rights that persist in the present. In world history, the decision by the Great Powers in 1918–1921 to deny the demands by anti-colonial movements for participation in the postwar settlement led to the protracted, costly, and incomplete efforts toward national self-determination in the decades to follow. Given recent events in the United States relationship to the world, my teaching often includes discussion of how American involvement in southeast Asia or the Middle East decades later can be traced back to decisions made by European powers after November 1918 to preserve and reinforce their control over non-European peoples.

By contrast, the “Spanish flu” pandemic seemed to have few lasting effects: borders remained the same, political ideas were not transformed, and social trajectories were not affected. The deaths of 50 to100 million worldwide, from this perspective, appeared part of the broader devastation of these years of war, revolution, and famine, but did not deserve attention as a distinct historical event. I don’t think I ever made a conscious decision not to teach about the 1918–19 pandemic; it just never occurred to me that it was more important than the other topics I did want students to understand.

The experience of living through and with COVID-19 will lead to two important ways that I plan to teach about the “Spanish flu” in European or world history in the future.

One approach I will likely take in the future is to compare the human toll of the 1918–19 and 2020–21 pandemics. The best estimates of the global death toll from the influenza pandemic are in the range of 50–100 million deaths. By November 2021, the global death toll from COVID-19 exceeded 5 million.Footnote 20 A simple comparison of total numbers suggests that the Spanish flu was ten to twenty times deadlier than COVID-19. More importantly, the world population is now nearly 8 billion, compared to less than 2 billion at the time of the Spanish flu pandemic, four times larger. The death rate from influenza in 1918–19 was 2,500 to 5,000 per 100,000 population, compared to 50 per 100,000 population in the current pandemic. In other words, the death rate from “Spanish flu” was fifty to one hundred times greater than the death toll from COVID-19. This comparison can serve two purposes: first, to understand the importance of rates as well as totals, and, more importantly, to understand just how uniquely devastating the earlier epidemic was for those who lived at this time.

This attention to numbers will also provide an important way to explore comparisons between regions of the world.Footnote 21 During the 1918–19 pandemic, approximately 10% of all deaths occurred in China, with a population of nearly 500 million, 25% of the world’s population. By contrast, the 675,000 deaths in the United States accounted for just 1% of the world’s total, at a time when the U.S. population of 100 million was 5% of the world’s total. In November 2021, by contrast, the U.S. population of 330 million was still about 5% of the world total, yet the US.’s 745,000 COVID-19 deaths accounted for 15% of the world’s total of 4 million. China’s 4,000 reported deaths from COVID-19 accounted for 0.1% of the world toll, at a time when China makes up nearly 20% of the world’s population.

These contrasts call attention to the second important change in my approach to teaching, which is to emphasize the public health response. Students with direct experience with COVID-19, who will make up most college students for at least the next decade, have firsthand awareness of the failure of American public health to respond to this crisis. The 1918–19 pandemic certainly provides many examples of health officials who underestimated the threat of influenza, neglected or denied important health measures, assigned priority to other outcomes, or simply did not care about the victims (particularly in colonized states). A century ago, however, public health lacked important tools for saving lives through treatment or preventing further spread of the disease. The next time I teach about the Spanish flu in world history, I will certainly draw a contrast between 1918–19, when health officials had many fewer options for preventing the spread of infectious disease; and 2020–21, when tools such as diagnostic testing, therapeutics, and vaccines were either already available or developed quickly. The fact that so many lives have been lost in 2021, especially in the United States, when these tools have been tested and proven to work, is further evidence that understanding pandemics, now and a century ago, requires attention to how human beings understand risk, make decisions, and deal with the consequences.

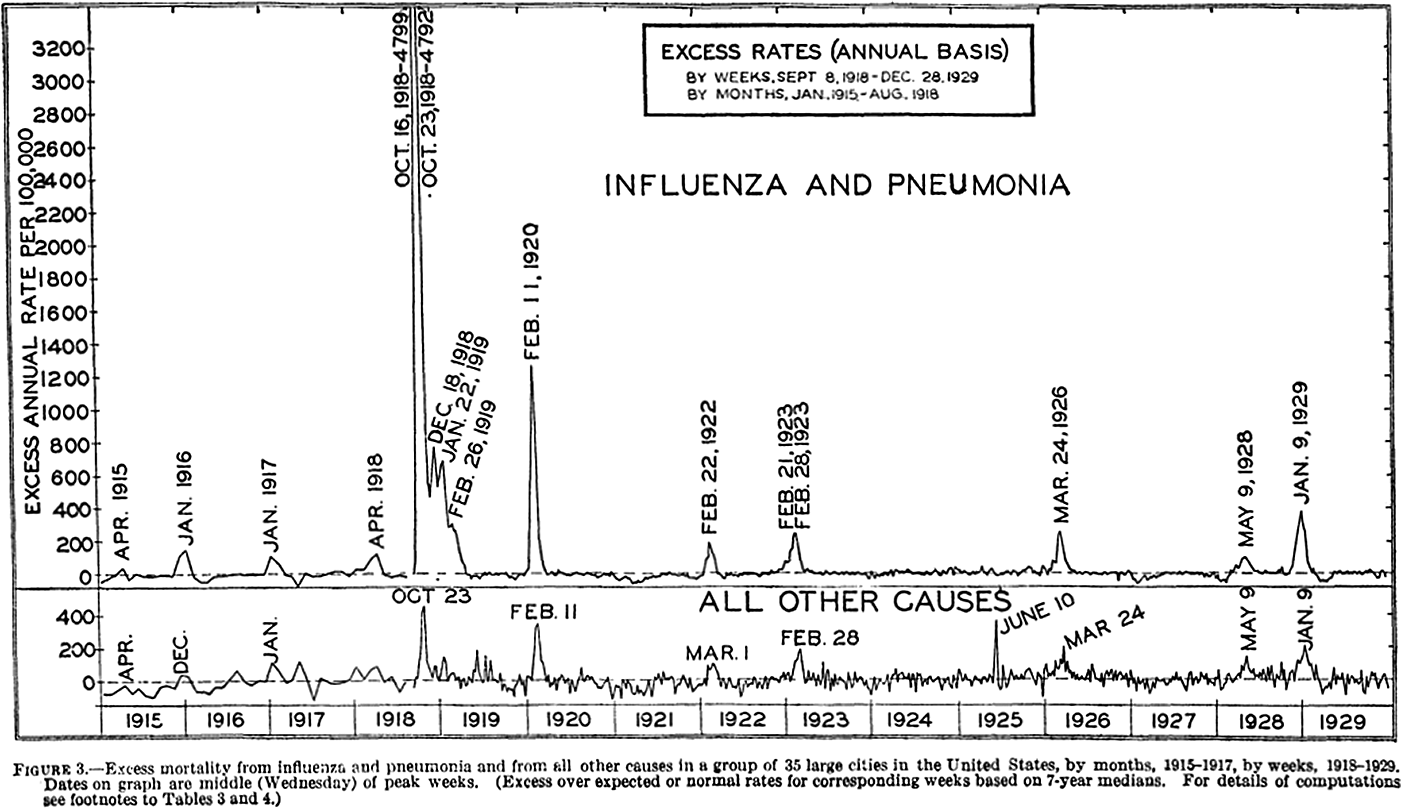

Image 5. “Figure 3” in Selwyn D. Collins, “Excess Mortality from Causes other than Influenza and Pneumonia during Influenza Epidemics,” Public Health Reports, vol. 47, no. 46 (11 November 1932), US Government Printing Office, 2162.

KHG: I appreciate Tom’s reflections on the 1918 pandemic and teaching. Interestingly, my own experience departs rather markedly from his. In my courses that touch on religious difference in the modern United States, the 1918 influenza pandemic has long been a topic of lively discussion. This stems in part from my own scholarly identity as a cultural and intellectual historian who specializes in the religious dimensions of American political culture. In our class discussions, the death of the philosopher Randolph Bourne during the 1918 pandemic illustrates how the loss of a single individual can shape the culture as a whole. Bourne’s vision of a “transnational America” never fails to fascinate my students, particularly given today’s scholarly emphasis on the “transnational” and the ubiquity of the prefix “trans” across American culture as a whole. I ask my students to consider how contemporary discourses about religious diversity and other axes of difference might look today, had Bourne managed to stay alive to promote his ideas. Bourne’s death left Horace M. Kallen as the most visible American proponent of cultural diversity, under the rather different rubric of “cultural pluralism.” What shape might our discourses surrounding diversity have taken if Bourne had survived or Kallen had died of influenza instead?

In countless ways, a single life matters greatly. This is true for ordinary citizens as well as those influential individuals with more power to shape the culture directly. Every day, families across the world are struggling to go on with members lost to, or seriously impaired by, the coronavirus. For those left behind, these terrible divide the world into a before and an after, creating a collective Rubicon of suffering with the power to generate significant cultural and political change, for both better and worse. There is no question that the decimation wrought by today’s pandemic in the United States and around the globe will forever alter the economic, social, cultural, intellectual, and political landscapes in ways we are only beginning to fully discern, and which—as several of my co-panelists have rightly noted—may prove difficult to measure even in retrospect. Loss leaves so much in its wake, and when it occurs on a global scale, it creates vast repositories of anguish, loneliness, anxiety, economic insecurity, and, perhaps most of all, fear. No wonder, then, that so many aspects of life today appear apocalyptic and that scapegoating has become so overt and widespread. We need only look at the noxious synergism of right-wing firebrand Steve Bannon’s cry to defend the “Judeo-Christian West” against the “China virus” with former President Donald Trump’s call to “build the wall,” or the efforts by some Southern conservatives to tie COVID rates to illegal border crossings, to see how the pandemic has reinforced age-old nativist fears of immigrants and contagion.

Meanwhile, the start of the school year has brought America’s long-simmering culture wars into the nation’s classrooms in new ways. For instance, in the state of Tennessee where I grew up, contentious claims about religion and democracy figure prominently in the ongoing debates, especially since Governor Bill Lee’s controversial decision to use emergency powers to prevent mask mandates in public schools. In a part of the state already known for its opposition to teaching about Islam, outrage about critical race theory now commingles with anti-vaccination and anti-mask sentiments. The words of Justin Kanew, a frustrated parent and progressive activist, at a Williamson County school board meeting dramatize the current ferocity and high stakes of our culture wars. Kanew’s daughter had asked why she needed to wear a mask to her new kindergarten class, even though most of her classmates were barefaced. He answered simply, “Because we want to take care of other people.” Kanew continued,

She’s five years old, but she understood that concept, and it’s disappointing that more adults around here can’t seem to grasp it. I asked a pastor friend of mine and he was very clear there’s no actual biblical justification for using the Bible to get out of a mask mandate passed by a majority of this elected board, but thousands are doing it anyway, calling it a religious exemption, which is frankly just sad. Avoiding masks is not in the Bible, but taking care of others is, and now today, we have Governor Lee’s executive order to allow opt-outs, which is government overreach undercutting a local decision. If you only like democracy when it goes your way, you don’t actually like democracy.Footnote 22

With this prophetic stand, Kanew called into question the religious authenticity of those Christian conservatives who profess to love their neighbor but refuse to get vaccinated or wear a mask. (As has been widely reported, white evangelical Protestants resist the COVID-19 vaccine more than any other religious group.)Footnote 23 Such clashes suggest that cultural and political change is already afoot. Just as the slogan “health care is a moral issue” dramatizes the inconsistency of defending the lives of the unborn without supporting universal health care. Kanew’s challenge highlights the hypocrisy of seeking a theologically dubious religious exemption to evade a mask mandate designed to prevent needless suffering and death.

DH: I’d like to return to Chris’ invocation of our effective vaccines—a remarkable medical accomplishment with no corollary in the 1918–19 pandemic—and his questions regarding that pandemic’s “end” and medium-term effects. Thinking in comparative terms with regard to inequality, I tend to gravitate toward two hypotheses about how our outlook differs from the past: one pessimistic, the other optimistic.

The pessimistic hypothesis is that the vaccines will help to manage, but will not wholly solve or eradicate the pandemic, and that the most vulnerable will continue to bear the brunt of its persistence, magnifying inequality of all kinds. One hopes, of course, that vaccines will further reduce hospitalizations and death rates, as they are doing in those areas where vaccination programs have made significant progress. But countervailing dynamics—limited and deeply uneven vaccine access worldwide; vaccine hesitancy in areas where vaccines are available; rampant misinformation; haphazard application of basic non-medical mitigation measures; and precipitous, not infrequently contradictory state policies on reopening—may mean the continued multiplication of coronavirus variants in the months and years ahead.

Such variants, if they come, might not produce further waves of global suffering. After all, there was no effective vaccine for the 1918–19 flu. It “ended” in part by mutating into less deadly variants by the mid-1920 (although as Alan points out, its presence subsisted both epidemiologically and socially long afterward). Unfortunately, estimates of millions dead from the Delta variant in India (in what novelist Arundhati Roy has called the “summer of dying”) and troubling initial research on “Long COVID” among the young—who in most places still lack access to the vaccine as of this writing—do not suggest that trajectory for the novel coronavirus. In this sense, the appearance of the 1918–19 flu’s “natural” dissipation might even offer false comfort, if not an excuse to those in power to refrain from taking politically controversial decisions necessary to protect public health and save lives. I fear a growing chorus advocating that we simply “learn to live with it,” advice that has deeply discriminatory effects for those who lack access to the vaccine or who have untreatable comorbidities.

The more optimistic hypothesis is that despite the pandemic’s obscene exacerbations of inequality, that very obscenity and the public scrutiny it attracts may bolster effective political demands to confront inequality, as I suggested above. In a way, this would echo the 1918–19 pandemic in the United States: a public health crisis that intensified social and political dynamics already in evidence.