I. Introduction

No corruption scandal is an island. Each situation is most certainly the product of different contributing factors to the emergence of corruption practices. Yet, there are some common traits of corrupt acts, common types of corrupt human behaviour, normative spaces and grey areas in law that are common triggering factors that might allow for corruption. Footnote 1 These and other factors collectively form the always “lubricated” fabric of corruption practices and acts that have occurred over the centuries and that still contaminate modern society.

In today’s highly interconnected world the advent of new digital solutions and emergent technologies is incessantly reshaping the “techno-social systems” which consist of “… large-scale physical infrastructures (such as transportation systems and power distribution grids) embedded in a dense web of communication and computing infrastructures whose dynamics and evolution are defined and driven by human behavior”. Footnote 2 Such techno-social systems are relentlessly developing towards new forms of technology-enabled infrastructures, such as digital platforms, which have the potential to change the nature of (human) interactions. These profound advances are affecting society, human behaviour and the potential regulatory spaces and grey areas and therefore raise pressing questions on how corruption is evolving and adapting to all of this.

Due to the crucial and practical implications of the adaptive nature of corruption within policymaking and regulation contexts, this article thus aims to approach the phenomenon through the lens of complexity theory, in which is seen, in line with Byrne and Callaghan, an “ontologically framework of understanding”. Footnote 3 Consequently, it also seeks to explain the relevance of complexity theory in steering policymaking and risk regulation for preventing corruption. Along these lines, corruption will be regarded – in essence – as a non-linear cause and non-linear effect adaptive problem. This is because the wide set of consequences originating from it, as well as the driving factors behind it, are made up of several independent, non-linear and omnipresent – at different levels – elements.

The article accordingly presents an examination of the functional evolution of corruption practices and explains the main risks by revealing the less obvious links and mechanics lying behind complex phenomena. In highlighting the potential policy implications and regulatory recommendations arising from such a revelation, the analysis builds on the well-known Cynefin framework. This “sense-making” tool provides a valuable support to create a “sense of time and place”Footnote 4 in responding to complexity, helping to assimilate the wide array of issues faced by policymakers in addressing real-world corruption problems. Through the framework, such issues can indeed be orderly disentangled into five contextsFootnote 5 and differentiated by the relative nature of the relationships between “cause” and “effect”. In this respect, Cynefin proves to be an insightful tool for contextualizing the complexity of corruption and for shedding light on some critical issues of the same (eg its perception and its measurement), as well as to the affected confidence.

Building upon a rich foundation of interdisciplinary literature that spans law, economics and sociology, this article moves the policy and regulatory debate surrounding corruption. The analysis proceeds as follows. Section II approaches corruption as a complex phenomenon by providing a comprehensive literature overview. In Section III, complexity theory is further explored in order to develop the methodological premises underpinning our analysis and also to advance anti-corruption policy and regulation. Section IV describes the Cynefin framework and how it could be usefully deployed for the purposes of this analysis. Section V then addresses corruption policy and regulatory objectives vis-à-vis the Cynefin framework domains. Section VI continues to build on Cynefin’s insights and focuses on corruption perception and confidence within techno-social systems. Section VII concludes.

II. Approaching corruption as a complex phenomenon

One of the most enduring debates in all of legal and socio-political thoughts relates to the definition of corruption.Footnote 6 Such long-lasting debate is but a reflection of the struggle in delineating the term itselfFootnote 7 and, most importantly, in capturing the precise contours of the ever-evolving phenomenon it refers to.

Indeed, over time corruption has been differently characterised by scholars on the basis of distinct theoretical and methodological approaches.Footnote 8 Such differences were mainly due to the features of the specific phenomenon of corruption dealt with, such as the personal attributes of the people involved and/or country characteristics.Footnote 9 This therefore entailed a great relevance of psychological, cultural, social and institutional factors,Footnote 10 which, by their very nature, call for case-by-case analysis and ad hoc approaches. Against this backdrop, it comes as no surprise that even the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), which is the first legally binding instrument against corruption, lacks a clear-cut definition of the phenomenon itself.Footnote 11

On top of that, the pace of innovation and technological advancement is prompting new challenges, chiefly respecting the setting or space where corruption spreads out. There is no need, in fact, to stress how much the structures of social and political systems have become “complex,” especially through the disruptive innovation that technological progress has brought.Footnote 12 Rather, it could be interesting to observe these drastic changes in light of the growing attention that the United Nations have recently paid to corruption’s systematic nature and its adaptability vis-à-vis the necessity to develop comprehensive and multidisciplinary approaches to prevent it. On this point, indeed, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has increasingly emphasised corruption as a “complex social, political and economic phenomenon that affects all countries”.Footnote 13

In parallel, the literature has also converged progressively towards a focus on certain characteristics of corruption. The scholarship has indeed been developing a more distinct systemic perspective in the analysis,Footnote 14 in the quest to clearly demonstrate that corruption is a complex phenomenon.

Interestingly, the literature review shows a frequent use of the term “complexity” associated with the analysis of corruption. As a matter of fact, however, complexity has mostly been seen as a sort of obstruction or hindrance to the examination of the phenomenon. Some studies approached complexity as a factor that increases the magnitude of corruption,Footnote 15 without appraising the nature of such “complexity” from a deeper and more comprehensive viewpoint. By way of example, corruption has been indicated as “a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, with a multiplicity of causes and effects, as it exhibits many different forms and functions in very diverse contexts”Footnote 16 (eg as it happens in organisationsFootnote 17 ). Moreover, considering that corruption in organisations is a complex phenomenon, in fact, it has also been also highlighted that controlling corruption becomes “even more complex”.Footnote 18 Finally, complexity has also been associated with difficulties in measuring it: given its “clandestine nature”, indeed, “corruption is intrinsically a complex phenomenon and hard to measure”.Footnote 19

By contrast, other approaches consider corruption rather as an “extremely complex phenomenon, which shows all the characteristic features of complex adaptive systems”.Footnote 20 This perspective incorporates contributions of complexity theory, excluding its connotation as a “complicated problem” and criticising from this standpoint traditional regulatory models that have, in general, “implicitly confused” them. Consistently, Habtemichael and Cloete state that “given the evolving nature of its forms, emergence of a universal understanding of its meaning, its fractal nature (omnipresence at various levels of society and government), non-linearity of its consequences (varying nature of its impact) and the back and forth movement of corrupt agents between various attractors (between betrayal and honesty), corruption is an adaptive complex phenomenon”.Footnote 21 Furthermore, Luna-Pla and Nicolás-Carlock have presented a comprehensive framework based on complex systems science for the analysis of corruption networks.Footnote 22

The contribution of the recent literature seems essential since it tries to overcome the limitations of the traditional approaches to corruption, which proved inadequate to handle the complex nature of the phenomenon.Footnote 23 Despite complexity theory not be defined as “a single coherent body of thought”,Footnote 24 the findings and methodologies arising from it represent “an ontologically founded framework of understanding”Footnote 25 to base the analysis on.

In embracing this canon of literature, this article aims to incorporate the insights arising from the advance of complexity theory into the policy debate surrounding corruption. More specifically, it deals with the various implications arising from the characterisation of the phenomenon as “complex”.Footnote 26 In parallel, we make an attempt to reconcile different strands of literature that could help in approaching questions pertaining to whether and how technology-enabled innovation can be deployed to fight corruption and foster market integrity. Innovation can most certainly contribute in devising instruments that can more adequately cope with a phenomenon that, as highlighted by Transparency International, “can happen anywhere”, “can involve anyone”, “happens in the shadows” and, finally, “adapts to different contexts and changing circumstances”.

III. Complexity theory, social sciences and anti-corruption regulation: charting a course

Oddly enough, there is no consensus on what complexity is. This uncertainty is glaringly due to its very nature.Footnote 27 A multitude of definitions have been proposed, reflecting the specific angle of analysis adopted case by case. Consistently, “the scientific notion of complexity … has traditionally been conveyed using particular examples of real-word systems which scientist believe to be complex”.Footnote 28 So, following traditional practice, Johnson summed up complexity by the catchy example “Two’s company, three is a crowd”, which bluntly shows that complexity can be seen, first and foremost, “as the study of the phenomena which emerge from a collection of interacting objects”.Footnote 29

In this perspective, corruption has been regarded “as a phenomenon that occurs within systems whose structure and dynamics can evolve as a response to changes in its corresponding socio-political and regulation context, with a strong dependence on the interrelation of different factors and actors acting as a whole”.Footnote 30 In our view, such characteristics may assume particular relevance within the anti-corruption regulatory landscape. This is the case since corruption “shows all the characteristic features of complex adaptive systems” and has “direct and important practical implication because as a complex phenomenon, corruption largely resists traditional regulatory models”.Footnote 31

Beyond this general statement, however, it seems crucial to elaborate further on this standpoint of analysis.Footnote 32 Over recent decades, theories and methodological approaches on complexity were in fact understood and implemented over different philosophical, disciplinary and practical lenses.Footnote 33 Complexity theory in particular escalated in the managerial field.Footnote 34 It has indeed been used from “governance and public administration, to health care and service delivery, to education, and to the interface between the social and the natural considered in ecological terms”.Footnote 35 As elegantly presented by Byrne and Callaghan, not only does complexity theory lend itself well to the development of mathematical formulas, but also, most importantly, it may help us tackle the big questions raised in social sciences.Footnote 36 The authors warn that a major criticism stems from the fact that the use of complexity ideas in social sciences is “merely metaphorical,” and yet, at the same time, we all know that “metaphors are what we live by”, as well as models.Footnote 37 Therefore, social sciences benefit from complexity theory not because the latter can show what the truth is, but rather because it can inform the way reality is approached and analysed. For this reason, it is extremely important to be aware that “there are good models and bad models and indifferent models, and what model you use depends on the purposes for which you use it and the range of phenomena which you want to understand …”.Footnote 38

These considerations remind us that complexity theory overtook traditional reductionistic research, which was mainly focused on reducing complex phenomena to elementary pieces.Footnote 39 In fact, over recent decades, the limits of reductionism have become quite evident, especially due to “today’s complexity, globalization and interconnectedness”.Footnote 40 Indeed, as has been properly pointed out in this regard, “complexity science expands on the reductionistic framework by not only understanding the parts that contribute to the whole but by understanding how each part interacts with all the other parts and emerges into a new entity, thus having a more comprehensive and complete understanding of the whole”.Footnote 41

In the ambit of corruption studies, nonetheless, reductionistic approaches still seem to be widely adopted. As rightly observed by Yeboah-Assiamah, adopting traditional reductionistic tools in the area of corruption “would yield futility”; in fact, the complexity of corruption “… suggests that a reductionist approach or adopting piecemeal anti-corruption models will not be effective”.Footnote 42 When dealing with corruption, reductionism could oversimplify what corruption really is and overlook inherent dangers, such as those resulting from the interrelations and interlinkages between corruption and markets. This can increase system fragility,Footnote 43 since the reductionistic approach might obstruct the analysis of contagion and transmission effectsFootnote 44 or, again, the design of effective regulatory models for prevention.

In other words, aligning to what has been observed by Morin, reductionism claims that we are all individuals in society and ecosystem, namely “merely units inside the systems, and … not the connections”. In contrast, “complexity tries to understand the type of connections that are present”.Footnote 45 Looking at complex systems from this perspective changes our understanding of the causes behind corruption and, thus, the contribution that each single factor plays in the system itself. Consequently, for the purposes of this analysis, corruption is regarded as a system.Footnote 46 Namely, corruption is one of the most difficult adaptive systems to manage due to the fact that it involves individuals and their interactions. They cannot be singled out and examined separately from each other to explain the emergence of the collective phenomena that their decisions may originate. The problem is even compounded by the consideration that people generally operate with an understanding of having “free will”, thus making the systems “unpredictable”.Footnote 47 As has been similarly asserted by Caldarelli et al, looking at behaviour in these systems “introduces another source of difficulty, as not all individuals are the same”. Footnote 48 Rightly, the same authors suggest an approach to such intricacies by using the well-established art of modelling in physics in collaboration with the social sciences, thereby invoking collaborations between researchers from different disciplines in the context of today’s massive use of information and communication technologies. On the same point, Bastardas-Boada on the occasion of the Congrès Mondial Pour La Pensée Complexe stated that to gain “an adequate view of the whole and to understand the how and why of the process pursued by the agents in reaching the states that guide their decisions … it will probably be necessary to use computational research together with other types of research that are closer to the changing cognitive and emotional activity of the agents”.Footnote 49

In line with these multi- and trans-disciplinary views, we believe that the insights coming from complexity theory as applied to corruption studies should be accompanied by an attempt to gain a more robust understanding of the policy implication that flow from technology-enabled innovations vis-à-vis anti-corruption regulatory objectives. Policy fails, in fact, particularly “when complex problems are addressed using standard linear and reductionist approaches that presuppose more knowledge and control than is ever possible in such situations”.Footnote 50 Equally, “as the complexity and interaction strengths in our networked world increase, man-made systems can become unstable, creating uncontrollable situations even when decision-makers are well-skilled, have all data and technology at their disposal, and do their best”.Footnote 51

This entry point of analysis adds to the debate revolving around the fight against corruption, especially “in an increasingly interconnected world of techno-social systems”.Footnote 52 As the argument goes, it seems essential to explore empirical sources and data in the context of today’s technological advancements.

IV. Gathering corruption as a whole and its parts: “making sense” with the Cynefin framework

The foregoing discussion pointed out how complexity theory has advanced policymaking when dealing with complex systems like financial markets or highly globalised sectors. This also holds true for corruption, which is an interwoven, multifaceted and adaptive phenomenon that cannot be fully captured by a purely reductionistic and holistic approach. Complexity theory could in fact aid policymakers realise at least two things, which are usefully set forth by the widely known Cynefin framework.Footnote 53 First, complex systems show a great deal of uncertainty, and it is very difficult, if it is even possible at all, to put forward any prediction about the future developments of the matter under scrutiny for policy purposes.Footnote 54 In other words, policymakers and lawmakers are bounded by the unpredictability of complex systems that, by their very nature, are never subject to full control. Second, policymaking should pay much attention to the “micro” and “macro” levels of phenomena alike; that is, to the trees and to the forest, and to how each single tree is contributing to the entire ecosystem.Footnote 55 As such, complex systems instruct policymaking in looking at whether and how individual actions at the micro-level can lead to emergent phenomena (systems) at the macro-level. Such systems are highly dependent on initial conditions that give rise to such emergent phenomena and are always evolving, making them unpredictable over the long term.Footnote 56

Due to these two features, we deem the Cynefin framework, or “sense-making” tool,Footnote 57 a valuable support to facilitating the achievement of the purposes of this research. Cynefin uses “narrative analysis” for dealing with complexity,Footnote 58 and it provides, as asserted by McLeod and Childs, “… a strategic approach to taking action for change” and a “… new construct for re-perceiving the challenge …, favouring the transfer of research into practice”.Footnote 59 The framework, in fact, is rooted in knowledge management and in complexity theory, and it has been developed and applied, over the last two decades, in a wide range of domains, allowing executives to assimilate complex concepts for addressing real-world problems and opportunities.Footnote 60 This framework expressly enhances communications and makes more understandable the operational context, perfectly reflecting the advances in complexity theory, which is “… poised to help current and future leaders make sense of advanced technology, globalization, intricate markets, cultural change, and much more”.Footnote 61 Its aim, or “theme”, as appropriately argued by Browning and Boudès, is therefore identifiable in its ability to create a “sense of place” in responding to complexity, offering different views and narratives about the possible past and future scenarios.Footnote 62

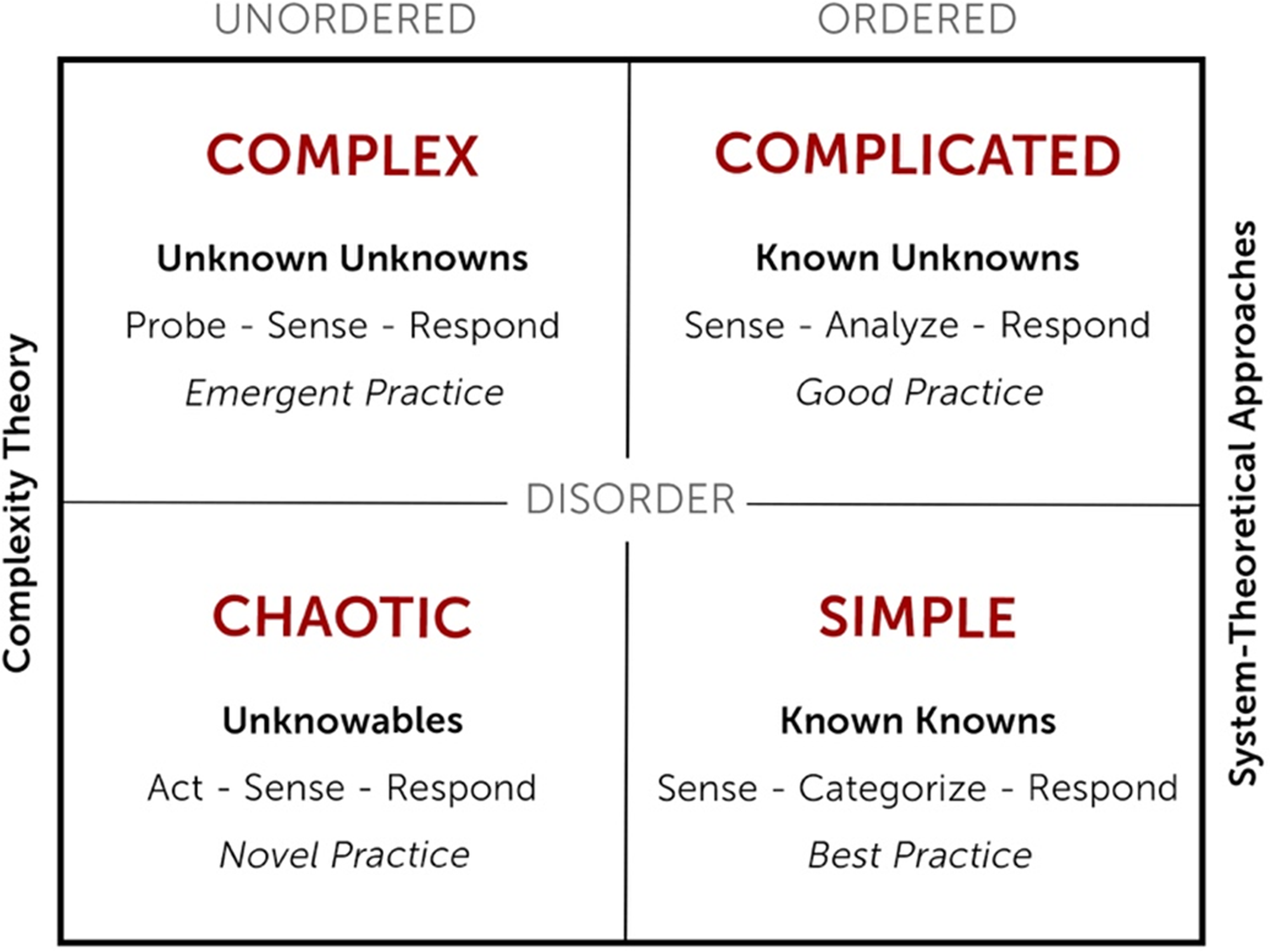

The first version of the framework was displayed in a two-by-two matrix involving “chaos”, “complex”, “knowable” and “known” categories.Footnote 63 Kurtz and Snowden placed the state of “disorder” in the middle of the matrix, which applies when it is unclear which context prevails over another,Footnote 64 such as in the case of interaction or transition between different contexts.Footnote 65 The matrix is based on the idea that the different contexts have blurred boundaries and should not be interpreted as rigid categories.Footnote 66

Other representations of the Cynefin framework provided by Snowden name the four domains “chaotic”, “complex”, “complicated” and “simple”, as shown in Figure 1, where the – very often misunderstood – distinction given by Turner and Baker between the applicability of general systems theory (GST) and complexity theory in the social sciences has also been integrated.Footnote 67 According to the purpose of their study, the authors expressly recommend the implementation of complex adaptive systems (CASs) for addressing today’s complexity in the social sciences, allowing in this way complexity theory to operate in parallel with systems theory. As the authors maintain, “While GST can operate under the principle of system holism from a reductionistic perspective, complexity theory could expand the social sciences by providing a perspective counter to the principle of system holism that incorporates a connectionist approach rather than reductionism”.Footnote 68 In their contribution, the authors identify, indeed, several advantages for the social sciences in incorporating complexity theory as a formal theory. This is also by virtue of the use of the Cynefin framework to display the invoked shift from the complicated domain of GST (right half of the framework in Figure 1) into the one of complexity (left half of the framework in Figure 1) to deal with complex phenomena.

Figure 1. Cynefin framework’s adaptation from Kurtz and Snowden (see Note 53), Snowden and Boone (see Note 53) and Turner and Baker (see Note 35).

It is important to observe that the four domains primarily differ because of their cause-and-effect relationship. The chaotic domain has been associated with the absence of cause-and-effect relationships, whereas the complex domain is characterised by cause-and-effect relationships that are instead understandable “… in retrospect and do not repeat”.Footnote 69 “Instructive patterns, however, can emerge if the leaders conduct experiments that are safe to fail. That is why, instead of attempting to impose a course of action, leaders must patiently allow the path forward to reveal itself. They need to probe first, then sense, and then respond”.Footnote 70 Such a domain is hence the one of “emergence”. By contrast, the complicated domain has been associated with having cause-and-effect relationships, while the simple domain has been characterised by predictable cause-and-effect relationships and, accordingly, “best practice”.

Using the same logic, the Cynefin framework’s dynamism lends itself well to exploring and capturing the conditions – perpetually in flux – of corruption within a policymaking and regulation context.

As has been outlined, we are considering corruption as a non-linear cause and non-linear effect adaptive problem. This is because the wide set of consequences originating from it, as well as the driving factors behind it, are made up of several independent, non-linear and omnipresent – at different levels – elements. Applying the complex domain of Snowden and Boone – “probe, sense, respond” (ie “the leader’s job”) – we obtain a roadmap for the discussion. This sequence, in fact, refers respectively to: (1) the creation of environments and experiments that allow patterns to emerge; (2) the increase of the levels of interaction and communication; and finally (3), the use of methods that can help generate ideas (eg set barriers, stimulate attractors and monitor for emergence).Footnote 71

1. “Probing”

We can preliminarily observe that the application of complexity theory to policymaking shows, as Geyer maintains, that “there is no clear linear policy answer to all situations …”. Beyond creating a stable fundamental order within which individuals can learn, interact and adapt, there is little a state can do with linear certainty.Footnote 72 Mainzer agrees that the economy is a chaotic, non-linear system and that in the long run it is extremely difficult for policymakers to foresee what it is going to become. Nonetheless, he overcomes some of this scepticism by acknowledging the possibility of engaging in “local predictions” that avoid groping-in-the-dark types of exercises.Footnote 73 Planning therefore seems to be viable only over the short term since it is possible, in theory, to anticipate how actors are likely to behave under complex conditions. This is obviously a significant challenge for all-sectors policymakers who are pursuing long-run goals and might be confronted with a high degree of layering of international legal regimes.Footnote 74

2. “Sensing”

We can preliminarily value the levels of interaction and communication. In dealing with corruption, in fact, complexity theory and its policy implications can aid accounting for the ways in which individuals and other agents might be expected to interact within that system and the ways that such interactions on the micro level can lead to major issues at the macro level. Baxter calls for a shift in focus of governance from direction to adaptation.Footnote 75 As described by Chinen, “governance will continue to steer individual and corporate behaviour and to set out the basic structures for interaction but more with a view towards enhancing the resilience of complex social systems and certainly not towards establishing some kind of stasis”.Footnote 76 Miller and Page delved deep into the interaction of economic agents and came to the conclusion that in complex systems the only way to advance the understanding of policy implications lies in paying attention to the networks of communications agents use to interact.Footnote 77 In dealing with corruption, this entails paying attention to international, national and local institutions and other means through which actors and governments interact and develop governing norms within the regulatory landscape.

Helbing has also devoted much of his work to investigating policy engagement with CASs.Footnote 78 Departing from legal and regulatory top-down structures, he advocates for bottom-up mechanisms and for self-organisation solutions. In his own words, “we need to step back from centralizing top-down control and find new ways of letting the system work for us, based on distributed, ‘bottom-up’ approaches”.Footnote 79 This approach is based on the idea that complex systems are better managed from the inside by nudging the development of an assisted self-organisation approach to structuring, regulating and governing CASs.Footnote 80

3. “Responding”

We can preliminarily observe that assisted self-organisation represents a halfway approach between both top-down complexity control (in a “command and control” approach) and unfettered bottom-up self-organisation like free markets. The self-organisation, in fact, steers the management of complex system towards the achievement of the desired outcomes. This assisted self-organisation operates through techniques of influencing complex systems and through an operationalisation of these techniques in information and communication technologies.

Connecting the dots, the three tasks of the complex domain perfectly encapsulate the overall emphasis that the framework puts on understanding how to make sense of the experience in order to act upon it.Footnote 81 According to Snowden, in fact, the sense-making process brings up the three following connected questions: “Do we see the data?”, “Do we pay attention to the data?” and “Will we, or can we get others, to act on the data?”.Footnote 82 These issues appear, undoubtedly, to be of crucial importance not only because the context of anti-corruption is complex and uncertain,Footnote 83 but also because human perceptions and perception-based metrics are commonly used in anti-corruption policies and studies.Footnote 84 In fact, considering the seemingly intractable nature of corruption, Heywood asks how we measure something that is, by its very nature, largely hidden. Nonetheless, he goes on to provide three goods reasons for doing so: “first, it is important to assess the scale of the issue, in terms of its extent, location and trends, so that we know what we are dealing with. Second, we want to see whether there are any clear patterns in order, third, to help identify explanatory variables that will aid our understanding of why and where corruption develops”.Footnote 85

In summary, measuring corruption helps us improve our ability to see where to take action. Thus, in navigating anti-corruption complexity, the Cynefin framework appears – at the intersection of complexity studies and law – to be the right framework to provide meaningful policy insights in order to guide this process. Cynefin’s approach to sense-making, in fact, allows us to better understand the natural behaviour of humans and “… to build systems to build on that understanding”, rejecting the creation of “… an idealistic system based on how things should be, to which human behaviour is then conformed”.Footnote 86

V. Corruption policy and regulatory objectives vis-à-vis Cynefin’s domain

The decision-aiding framework described above has been incorporated into the discussion for several reasons. In providing a new way to approach and assimilate complexity – and complexity perception – of our real world, it orderly sorts the wide range of issues faced by policymakers into five contexts. In doing so, it offers an important distinction based on the relationships between cause and effect, differentiating the issues by their relative nature. This allowed us to contextualise what we previously discussed about complexity, the characterisation of corruption as “complex” and, accordingly, the advance of complexity theory into the connected policy and regulatory debate.

Moreover, since the framework has been conceived to deal with a variety of policy scenarios, its main characteristics have been thoroughly examined so as to foresee whether and how it could be effectively deployed for anti-corruption policy and regulation.

In this respect, Cynefin proves to be an insightful tool – we believe – for shedding light on some critical issues of corruption (ie its perception and its measurement). This, as has been seen, is not only because Cynefin’s approach to sense-making allows for a better understanding of the natural behaviour of humans, but also, in light of the three highlighted issues within its approach, it allows for a better understanding of whether we see data, whether we pay attention to the data and whether we can act – or whether we can get others to act – on the same.

As is well known, in fact, the policymaking process involves collecting as much information on an issue as possible, even though it is impossible to obtain all such information. It would ideally require sifting out all possible scenarios, despite it being impossible to consider all potential outcomes. It would ideally allow for revisions and adjustments any time that these are needed, but – again – it turns out to be impossible to guarantee ways to fix flaws as they come up. Footnote 87 And within anti-corruption, it is well acknowledged that such difficulties in collecting information and in measurement are exacerbated more and more by the very elusive nature of the phenomenon.

Over recent decades, for example, numerous sources of information have been employed to assess corruption and its impact on the environment, helping to delineate, for example, “regulatory, managerial, probing, compliance, promotional and reactive measures” in order to face the phenomenon. Footnote 88 However, as is observed in the Manual on Corruption Surveys, when the measurement of corruption begins, “the difficulty of collecting relevant evidence favoured the use of indirect approaches, in which the measurement is not based on the occurrence of the phenomenon of interest but on other methods of assessment”. Footnote 89 The manual therefore sets out the principal indirect approaches used in the assessment of corruption. It distinguishes between “expert assessments”, where a select group of experts is asked to provide an assessment of corruption trends and patterns, and “composite indices” (ie the application of methodologies to combine a variety of statistical data into a single indicator). Data may derive from evidence-based metrics, even if they generally arise from expert assessments and surveys, as well as from proxy indicators (eg freedom of the press). Footnote 90 Nonetheless, despite the advances in measurement, Footnote 91 such indicators still suffer from serious weaknesses in relation to their validity, relevance and use, as well as the other “perception-based indicators” and “experienced-based indicators”, placed by the Manual into the category of direct methods. Footnote 92

Such challenges relating to collecting and gauging corruption data could effectively be dealt with by drawing on Michaels’ pioneering contribution.Footnote 93 Michaels, in fact, examines how six different knowledge brokering strategies – “informing, consulting, matchmaking, engaging, collaborating and building capacity”Footnote 94 – might be employed in responding to the several environmental policy problems or policy setting recognised in decision-aiding frameworks. In building up her arguments, the author analyses the feasibility of primary knowledge brokering strategies with four different decision-aiding frameworks, comprising the Cynefin framework.

Knowledge brokers are people or organisations that move knowledge around,Footnote 95 creating connections and acting, in substance, as intermediaries between researchers, producers of knowledge and policymakers, who are the prospective consumers of that knowledge.Footnote 96 As Meyer maintains, in fact, knowledge brokers not only move knowledge, but they also produce a new kind of the same: “brokered knowledge”.Footnote 97 Given the above, Michaels, however, specifies that there is no exclusive, ideal form of knowledge brokering within policy development but, rather, a spectrum of strategies for brokering knowledge, from which the six ones discussed in her contribution have been selected, and matched, with the four decision-aiding frameworks.Footnote 98

For example, the author identifies as primary brokering strategies within Cynefin’s domains the following ones: within the simple or known domain, “informing”; within the complicated or knowable domain, “consulting”; within the complex domain, “engaging”; and, finally, within the chaotic domain, “opportunistic entrepreneurship”.Footnote 99 As is seen, in fact, in the ordered domain of known cause-and-effect relationships, the same relationships are linear and empirically proven. Therefore, as argued by Kurtz and Snowden, “consistency” and “efficiency” can be obtained through the incorporation of what is known into structured process like single-point forecasting, field manuals and operational procedures. The decision model is “… to sense incoming data, categorize that data, and then respond in accordance with predetermined practice”.Footnote 100 In the ordered domains of knowable causes and effects, instead, while stable cause-and-effect relationships exist, “… they may not be fully known, or they may be known only by a limited group of people”.Footnote 101 As stressed by the authors, in fact, this is the domain of system thinking, learning organisations or adaptive enterprise, which are too often confused with complexity theory. In this domain, therefore, “experiment, expert opinion, fact-finding, and scenario-planning are appropriate”; the decision model here is therefore “to sense incoming data, analyze that data, and then respond in accordance with expert advice or interpretation of that analysis”.Footnote 102

As the argument goes, it is possible to observe that, broadly speaking, the vast majority of current corruption proxies, indicators, indices and their traditional methods comes within the ordered domains. However, since they intrinsically approach corruption in a standardised and linear fashion, some issues may arise insofar as the domain, as discussed, will tend to be “complex” rather than “complicated” or “simple”. Footnote 103 As was seen in Section III, for example, the unpredictability of such systems is strictly connected to the fact that individuals – who generally operate with an understanding of having free will – cannot be singled out and examined separately from each other to explain the emergence of the collective phenomena that their decisions may originate. In other words, when complex problems are addressed using standard linear and reductionist approaches, serious risks can originate that have the potential, at the bottom, to nullify policy efforts.

Moving to the unordered domain of complex relationships, we finally land on the area where complexity theory studies, as we have seen, how patterns emerge through the interaction of many agents. Here, cause-and-effect relationships are present between the agents, but “… both the number of agents and the number of relationships defy categorization or analytic techniques”.Footnote 104 For these reasons, policymaking should be reluctant to fully incorporate experts’ opinions on historically stable trends and patterns in order to foresee and manage future scenarios. This reflects exactly the situation of corruption in expert assessments where a selected group of experts is asked to provide an assessment of corruption trends and patterns of meaning. Accordingly, the decision model within this domain aims to create “probes” in order to make the patterns or potential patterns more visible before we take any action; then we can sense those patterns and respond “… by stabilizing those patterns that we find desirable, by destabilizing those we do not want, and by seeding the space so that patterns we want are more likely to emerge”.Footnote 105 Here, as we have seen, Michaels identifies “engaging” as a primary brokering strategy that seems very appropriate for bringing about advantages in complex anti-corruption environments. Briefly, the intent of this strategy is to frame the discussion through terms of reference within the decision-making process, involving other parties in the fundamental aspects of the problem. Examples of engaging brokering techniques are, according to the author, “Royal commissions”, “Technical committees” and “Secondments” in order to identify those “… who need to be engaged and how” and to identify and expose decision-makers to “salient, multiple perspectives”.Footnote 106 By contrast, in the chaotic domain, everything changes. Here, there are no such perceivable relations, and the system is “turbulent”; therefore, the decision model aims “… to act, quickly and decisively, to reduce the turbulence and then, to sense immediately the reaction to that intervention so that we can respond accordingly”.Footnote 107

Therefore, as we have discussed, fostering collaborations and unconventional cross-sectional synergies between researchers from different disciplines in the context of today’s massive use of technologies appears crucial and is strongly recommended for gauging and responding to corruption. Similar objectives, however, seem achievable only if strongly supported by international organisations like the United Nations or, in the ambit of the European Union, if promoted by the European Commission. Such initiatives could in fact trigger a process of expansion of the existing methodologies, paving the way to innovative approaches to complex systems that could be valuable to both the system as such and each and every component of such system. Following this multi- and trans-disciplinary view within anti-corruption seems likely to be the best way to provide new perspectives for policymakers and leaders who are called to respond to a phenomenon that evolves at the same rate as today’s interconnected and networked world of techno-social systems, creating uncontrollable and unpredictable situations that exponentially increase their riskiness. Thus, enhancing the technological advancements conjointly with multi- and trans-disciplinary efforts in responding to corruption, as we have expressed, could represent a full-fledged opportunity to devise methodological approaches and instruments that can be more adequately deployed in the context of the times we are living in.

From this perspective, technology should favour the required dialogue addressing, for example, fundamental questions pertaining to corruption measurement and, hence, its perception and the related issues about trust and confidence.

In the next and evaluative section, we will further examine the relationship between the “perception” of corruption and “confidence” in light of technological advancement and complexity. As argued by Clausen et al, there exists a “… quantitatively large and statistically significant negative correlation between corruption and confidence in public institutions”.Footnote 108 This appears, in fact, to be crucial for understanding and controlling corruption, as well as being intimately connected to what is discussed in the final sections of this article. As such, “perception” and “confidence” lend themselves well to providing paradigmatic examples of possible connections between highly contextualised micro-level individual behaviours surrounding corruption and larger regulatory system-wide phenomena.

VI. Corruption perception and confidence within techno-social systems

The highlighted negative correlation that characterises the relationship between corruption and confidence in public institutions deserves to be further analysed for several reasons. The first and most basic of these reasons concerns the relationship between corruption and confidence “per se”. As also observed by Clausen et al, in fact, despite such a negative effect revealing an important channel through which corruption can inhibit economic and social development, it remains relatively under-examined in literature. Footnote 109 A second reason may concern, instead, the relationship between corruption, confidence and the emergence of other outcomes. To this point, the same authors find, for example, “… strong evidence that a lack of confidence in public institutions raises sympathy for violent protest, raises the desire to migrate, and reduces political participation”. Footnote 110

In zooming in on such a negative correlation, however, one of major contributing factors also lies in “perception”. To contextualise this, we still consider – at the risk of some oversimplification – certain findings arising from the mentioned study of Clausen et al that measure corruption and confidence in public institutions by using selected questions of the Gallup World Poll (GWP) survey – the largest (on a country coverage basis) annual multi-country household survey in the world. To create an index of confidence, the authors therefore sum together the responses pertaining to the confidence of respondents about the survey’s questions (a), (b), (c) and (h), which are representative of confidence in public institutions. Footnote 111 As their key measure of corruption, instead, the authors use a different question from the GWP about respondents’ personal experience with corruption. Footnote 112 In addition, as that GWP provides a more generic question about respondents’ personal perception of corruption, Footnote 113 the authors also use this more generic question as another measure. In parallel, the authors illustrate the country-level variation in these two measures of corruption and find that all countries “fall above the 45-degree line”, therefore indicating that “on average” all of the respondents are more likely to answer “yes” to the corruption perception question than to the corruption experience questions. Footnote 114

What consistently emerges from this corruption perception measure, in summary, is the respondents’ exposure to “second-hand” information about corruption activity. Such a “hearsay” effect, in fact, “… might very well artificially amplify the relationship between corruption and confidence in public institutions”, representing the centrality of perception in understanding corruption. Footnote 115 In light of this artificial amplification, the recent upsurge of technological innovations and the social changes they bring with them raise pressing questions regarding the consequences they may have on perception. Governments have indeed started to identify the technological revolution as a way of addressing the empowerment of individuals to participate in society as a whole. A new canon of literature has emerged in relation to e-government and corruption prevention, thanks, for example, to the adoption of artificial intelligence.Footnote 116 E-government is gaining popularity amongst practitioners and researchers due to its potential to increase transparency and combat corruption in government administration.Footnote 117 Some empirical studies in fact showed that, over the last decade, increases in the use of e-government have led to reductions in corruption in non-Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.Footnote 118 Quite importantly, it has been noticed that e-government solutions can lower the interaction between government officials and citizens and hence diminish the discretionary power of officials, which, in turn, minimizes the opportunities for corrupt practices.Footnote 119

Digital technologies and emerging technologies, as a matter of fact, are not only fostering new ways of communication, involvement and cooperation between individuals and society, but they are also modifying the ways under in confidence and perceptions take shape.Footnote 120 It is well known, for instance, that blockchain has been launched as an initiative to regain public trust in traditional institutions and intermediaries by promising, in essence, to revolutionise the myriad of services provided by government agencies at all levels. Footnote 121 The decentralised ledger technology thus not only emerged as a potential solution to the erosion of trust, but, as it happens, it has also effectively and dramatically changed the idea – and perception – of the same. Footnote 122

Overall, emerging technologies therefore have the potential to affect individuals’ perceptions and their confidence. In this respect, coming back to the mentioned centrality of “perceptions” within the study of corruption, Bautista-Beauchense identifies, indeed, the necessity from a theoretical standpoint to develop a conceptual tool for the analysis of corruption perceptions and also to account for contextual norms that adapt flexibly to the changing nature of the phenomenon. The author similarly puts forward the concept of “corruption folklore” to address this gap. Footnote 123 Elaborating on Myrdal’s description of the concept, which refers to people’s “beliefs about corruption and the emotions attached to those beliefs, as disclosed in the public debate and in gossip”, Footnote 124 Bautista-Beauchense proposes to “… take the concept a step further”, arguing that “… folklore is not only constituted of ‘bad guesses’, but rather, a melting pot of facts, rumours, stories, gossip and hearsay. The folklore can be complex and contradictory, as it does not represent a dichotomous understanding of the state of corruption in a given context …”. Footnote 125 Therefore, the same author also specifies that folklore, as fully described in his study, creates somewhat of a “buffer” between perceptions of corruption and agents’ strategies and actions. Thus, in his view, “the key theoretical point is that corruption perceptions create a folklore, not strategies or actions. The folklore influences expected risks and rewards (as the principal-agent theory describes); and the folklore affects the broad understandings and shared expectations provided by the institutional context (as underlined by the collective action theorists)”. Footnote 126

Along similar lines, the link between the findings of the previous sections about the most referred to measures and indices of corruption therefore appears evident. Footnote 127 Likewise, this also holds true for Cynefin’s approach to sense-making, which allows for a better understanding of the natural behaviour of humans and for building systems on that understanding, questioning whether we see data, whether we pay attention to the data and whether we can act – or whether we can get others to act – on the same.

As has been seen, Cynefin could therefore help us to incorporate the complexity of perceptions of modern techno-social systems, guiding policymaking to look at corruption phenomena from different perspectives.

Moreover, as we have already seen, complexity theory emphasises how important the components and their interactions are in the system. Footnote 128 Furthermore, such interactions “… among the system’s constituents are not centrally controlled, but rather local”, Footnote 129 as has been seen, and are not random, since we have “the response time” when investigating the change. Footnote 130 This decentralisation of a system’s constituents aligns with the centrality of perception as well as with the potential stemming from modern technology.

For example, the European Union’s anti-corruption report Footnote 131 of 2014 evaluated the cost of corruption “alone” at about €120 billion per year. To this point, Shalvi highlights that such a report “makes it clear that the costs are not just financial”, even considering that “corruption not only deprives people of economic prosperity and growth, but also jeopardizes their intrinsic honesty”. Footnote 132 Nonetheless, as an extremely stylised example, an increment in dishonesty within a given population can multiply the possibility that corruption scandals will emerge, which will likely in turn make corruption perception grow. Along these lines, as observed by Melgar et al, a “high level of corruption perception could have more devastating effects than corruption itself; it generates a ‘culture of distrust’ towards some institutions and may create a cultural tradition of giving and hence, raising corruption”. Footnote 133 Furthermore, relating to the mentioned “distrust”, as the vast majority of the literature has affirmed, corruption negatively affects “trust” and “confidence” in several ways and, therefore, both foreign direct investment and domestic investment. Footnote 134

As has been shown, corruption lead to a wide array of consequences that impact at the level of perception. In this respect, complexity theory provides an enlightening perspective on such a matter, especially regarding confidence. To this point, Luhman Footnote 135 and De Filippi et al, for example, stress that “interacting with a complex system is likely to require more trust than interacting with a single entity, or with a system made of only a few simple parts. Indeed, lack of trust in any of the constitutive parts of a system might bring people to distrust the system as a whole”. Footnote 136 The same authors therefore state that “the higher the complexity of a system, the longer it will take for concrete expectations to develop about the operations of that system”. Footnote 137

Human perceptions escalate and thus create what could be described as “corruption reverberations” that bounce around the systems. Such reverberations develop and spread over the systems, setting in motion a chain of consequences that call for policy action. Indeed, a loss of confidence brings about systemic risk that has the potential to dramatically undermine the integrity and soundness of the system itself.

VII. Concluding remarks

Technology is reshaping the way interactions take place. Technological advancement will likely morph and manifest in a myriad of media, offering untold conveniences and unknown challenges and creating unappreciated risks and immeasurable opportunities for corruption. In this perspective, emergent technology may play a role in creating considerable rewards for measuring corruption or, better, the perception of it. A theme that is likely to persist is the enduring relevance of the confidence underpinning such interactions. In the end, all humans are moved and tied by an inescapable network of perception mutuality, the fruits of which are relentlessly destined to shape individual and collective behaviour. The greater the number of the components in the systems (bureaucrats, constituencies, individuals, intermediaries), the higher the level of confidence that needs to be built in. The more complex, layered and intertwined the society, the greater the size of the “grey areas” where corruption can emerge in ways that are still to be fully understood. The Cynefin framework could aid policymakers to take a systematic approach and focus on the determinants of corruption as a complex adaptive phenomenon. Cynefin could in fact account for interactions and interrelationships between the different contributing factors, helping qualify the linear or non-linear nature of the relationships between “causes” and “effects”. In increasingly complex techno-social systems, future research could further investigate ways by which to capture the connections between the highly contextualised micro-level individual behaviours surrounding corruption and larger regulatory system-wide phenomena.