1. Introduction

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has controlled the House of Representatives, and by extension controlled the Japanese government, almost continually since its formation in 1955–21 of the last 23 elections (91% of the time) to be more precise. Party dominance, the almost constant presence of one large party at the head of government, has become synonymous with Japanese politics, and the LDP is its poster boy. When the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) managed to beat the LDP in 2009, for a moment it seemed that the era of LDP dominance had come to an end. However, by the following election in 2012, the LDP returned to power against a now weak and divided DPJ. To top it off, the DPJ splintered to the point that Japan's party system now has a jumble of small, ineffectual opposition parties, cementing the LDP's dominant position post 2012. While LDP dominance is nothing new to Japanese politics, its resurgence following the DPJ's victory is puzzling. Previous work on LDP dominance points to the LDP's candidates and clientelistic networks as the primary source of its strength (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Rosenbluth and Thies2000; Scheiner, Reference Scheiner2005, Reference Scheiner2006; Reed, Reference Reed2009; Bouissou, Reference Bouissou and Pekkanen2018), but it is well-documented that Japanese politics has shifted to nationalized, party-based, and policy-focused competition (Rosenbluth and Thies, Reference Rosenbluth and Thies2010; McElwain, Reference McElwain2012; Catalinac, Reference Catalinac2016). Reed et al. specifically studied electoral competition in Japan in the wake of the DPJ's victory, finding that from 2005 onward, party competition had taken center stage, circumstances that would at the very least, make the resurgence of candidate-based LDP dominance extremely unusual (Reference Reed, Scheiner and Thies2012). As they put it, ‘one thing we should not expect is a return to single party dominance, either by the LDP or the DPJ’ (p. 375).

If LDP dominance has returned, as it appears to have, it seems highly unlikely that it would be through the old ways of candidate-based clientelism. The literature on Japanese politics has a clear grasp on what has driven LDP dominance in the past, but what of the present? What is driving electoral competition in Japan such that the LDP is dominant once more? I argue that while the loss of the DPJ as a competitive rival has restored some of the importance of candidates, this new period of LDP dominance is still in large part the result of party appeal (or a lack thereof). With the splintering of the DPJ in 2012 and the subsequent proliferation of small, weaker parties, the LDP is perfectly positioned to capitalize on its strengths as the only large party in an electoral system that heavily rewards large parties. Similar to Reed et al., I analyze candidate performance in single-member district races, covering all House of Representatives elections between 2000 and 2017. I examine candidates' vote share and probability of winning an election and, like them, find that from 2005 onward, party affiliation exceeds candidate quality as the more substantial predictor of candidate performance. I find that candidate appeal makes a return in influencing a candidate's chances at the ballot box, but crucially, I find that party affiliation continues to play a substantial role in this new era of LDP dominance even in the absence of a two-party rivalry.

2. LDP dominance then

As I have mentioned, LDP dominance has been the norm in Japan for some time and as such, many scholars have tried to figure out why. The primary explanation for the LDP's success in the past has revolved around candidates. Some scholars offer that LDP candidates were better positioned to navigate the single non-transferable vote (SNTV) system that Japan used from 1947 to 1993 (Hickman and Kim, Reference Hickman and Kim1992; Cox and Niou, Reference Cox and Niou1994; McElwain, Reference McElwain and Pekkanen2018). LDP politicians, using the LDP's monopoly of government to its advantage, erected koenkai, personal networks with clientelistic linkages between candidates and specific groups of voters. These candidates, housed in a decentralized party and focused on building and maintaining koenkai, had massive advantages over candidates from opposition parties (Richardson, Reference Richardson1997; Shinoda, Reference Shinoda2013). The heart of koenkai was pork barrel politics, the fuel that kept the LDP dominance engine running, reaching from national to local government and ensuring that opposition candidates would find it incredibly difficult to work their way in from outside the pipeline (Scheiner, Reference Scheiner2005, Reference Scheiner2006). The personal networks that candidates built and funneled pork into were as expensive as they were extensive, and the LDP's first mover advantage in securing government control allowed it to monopolize government resources to greatly benefit its own candidates (Krauss and Pekkanen, Reference Krauss and Pekkanen2011; Bouissou, Reference Bouissou and Pekkanen2018); essentially, SNTV and the clientelism that flourished within it, created a toxic environment for non-LDP candidates that may not have guaranteed party dominance but certainly fostered it.

Taken together, this literature makes a compelling case for why LDP dominance existed in the first place. Japanese politics valued pork which candidates delivered to specific groups of voters through their personal networks. The LDP was the party with the pork and as such, its candidates held all the advantages.

However, in 1994, Japan replaced SNTV with a mixed-member majoritarian (MMM) electoral system, its advocates hoping to break up the stranglehold of clientelism and candidates. With the old SNTV institutions out of the way, many scholars mused about how Japanese politics would change and whether LDP dominance would dissipate in response (Kohno, Reference Kohno1997; McKean and Scheiner, Reference McKean and Scheiner2000; Wada, Reference Wada2003). Their expectations rested on the premise that Japan now had a system that incentivized party-based, policy-focused competition (Christensen, Reference Christensen1994; Jain, Reference Jain1995), Japan's economy and demographics were creating more independent voters (Noble, Reference Noble2010), and, since MMM uses single-member districts, several scholars invoked Duverger's law to predict Japan would transit specifically toward a predominately two-party system (Thies, Reference Thies, Hsieh and Newman2002; Reed, Reference Reed, Gallagher and Mitchell2005, Reference Reed2007; Jou, Reference Jou2009; Kaihara, Reference Kaihara2010).

In other words, scholars were looking for two things: elections becoming more party-based and the weakening of LDP dominance. Evidence for these changes came slowly. Candidates still carried substantial influence in the immediate aftermath of electoral reform as LDP politicians sought to maintain as much of the ‘old ways’ as possible (Tsutsumi and Uekami, Reference Tsutsumi and Uekami2003). A new opposition party, the DPJ, formed and started gaining some momentum, but the LDP held onto power largely through the strength of its candidates as it had before (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Scheiner and Thies2012). By the mid-2000s, however, several developments in Japanese politics showed signs of the expected shifts in electoral competition.

The first of these developments was the surprise election of Junichiro Koizumi as LDP leader. Once he became prime minister, Koizumi pushed for a series of reforms that would weaken the pipeline of pork fueling the LDP's candidate-centric politics. He was met with considerable opposition from members of his own party which ultimately killed his legislation. Aggravated by these entrenched LDP politicians, Koizumi, called a snap election in 2005, and ran a party-based campaign against LDP candidates. He kicked out several LDP politicians from the party and brought in ‘assassins,’ Koizumi-backed candidates running specifically to oust those who opposed his reforms, in a fight to change the LDP from the inside (Kabashima and Steel, Reference Kabashima and Steel2007). The gambit largely succeeded and the LDP won a substantial number of seats, many of them Koizumi supporters.

Koizumi's fight with LDP politicians was evidence of a movement toward a more centralized LDP, guided by policy and party interests over factional conflict and pork (Christensen, Reference Christensen2006; Noble, Reference Noble2010; Mishima, Reference Mishima2018; Uekami and Tsutsumi, Reference Uekami, Tsutsumi, Harmel and Svåsand2019). The LDP was still the dominant party under Koizumi, but scholars now had substantial evidence that candidates were beginning to take a back seat to party.

As for the evidence of the erosion of LDP dominance, the DPJ's slow and steady rise became the focal point for party system change in Japan. This was punctuated even further by the DPJ's victory over the LDP in 2009, with the largest seat share for one party in Japan's history. So how did the DPJ do it? The DPJ's formation and eventual success was due in large part to the increased emphasis on parties brought about by electoral reform (Reed, Reference Reed, Gallagher and Mitchell2005, Reference Reed2007). The DPJ rallied voters to it by defining itself as an anti-LDP party, without the need to build up a following for each of its candidates individually (Kushida and Lipscy, Reference Kushida, Lipscy, Kushida and Lipscy2013). In other words, the LDP was bested because the appeal of the DPJ as a party was greater than the LDP's appeal.

At this point, scholars' expectations had been fully met. Electoral competition in Japan was becoming more party-focused and it seemed that Japan had transitioned to a predominately two-party system. Reed et al. found that the 2005 election with Koizumi's assassins marked a change in electoral competition that moved attention from candidates to parties, something that held true for the 2009 election as well (Reference Reed, Scheiner and Thies2012).

3. LDP dominance now

While the literature has a thorough explanation for LDP dominance in the past, it is far less clear about the fall of the DPJ and return of LDP dominance from 2012 onward. Has Japanese politics reverted to candidate-based competition or does party appeal continue to be influential even in the absence of a two-party system? Scholars have discussed the DPJ's collapse primarily through party-based explanations. The DPJ attracted candidates and voters primarily with its ‘not the LDP’ messaging, but this resulted in competing policy priorities and a sprawling platform that proved exceedingly difficult to enact (Kushida and Lipscy, Reference Kushida, Lipscy, Kushida and Lipscy2013). When it had difficulty enacting its agenda, the LDP hounded the DPJ, pointing to its failures as evidence of an incompetent party in way over its head (Nihon Saiken Inishiatibu, 2013; Kamikawa, Reference Kamikawa2016). Ultimately, the DPJ party relied heavily on its national image, and when that image faltered, so did the party (Iga, Reference Iga2014).

There is reason to believe that, just as the DPJ's failures were rooted in its (lack of) party appeal, the LDP's return to dominance is based on party as well. While the LDP still has some internal, candidate-based conflict as it did in its early years, its organization has largely adapted to the more party-focused MMM system (Krauss and Pekkanen, Reference Krauss, Pekkanen and Pekkanen2018). Elections have become more nationalized, prime ministers like Koizumi and Abe acted as party leaders with comprehensive agendas, and campaigns continue to a focus on policy even after the DPJ's collapse, something that holds true for all parties (McElwain, Reference McElwain2012; Catalinac, Reference Catalinac2016; Yokoyama and Kobayashi, Reference Yokoyama and Kobayashi2019).

Of course, Japanese elections still involve candidates to a great degree and their influence on recent electoral results is well known (Fiva and Smith, Reference Fiva and Smith2018; Smith, Reference Smith2018; Hijino and Ishima, Reference Hijino and Ishima2021). It could be argued that in the absence of a strong party rivalry, elections would naturally focus back on candidates since the contest between parties is so uncompetitive. Additionally, there is evidence that LDP policies are not particularly popular among voters despite the LDP's consistent success (Horiuchi et al., Reference Horiuchi, Smith and Yamamoto2018), something that candidate appeal may help mitigate. However, even if individual candidate appeal has become more important, this does not erase all the larger changes that have taken place in Japanese politics over the last two decades. Even in the absence of a real competitor to the LDP, party should remain a significant determinant of electoral performance over individual candidate appeal even in this new period of LDP dominance.

4. Candidate quality, party affiliation, and electoral performance

To see the extent to which party and candidate appeal are contributing to LDP success since its return to dominance, I analyze candidate performance in single-member districts for every House of Representatives election between 2000 and 2017. I perform a similar analysis to Reed et al.'s examination of newcomer candidate performance between 2000 and 2009, though I expand the analysis to include every candidate from a major party in single-member districts for all Japanese House of Representatives elections and add the results from the 2012, 2014, and 2017 elections. For 2000 through 2009, the analysis only looks at LDP and DPJ candidates, but for the remaining years, I include the Tomorrow Party of Japan (TPJ), the Japan Innovation Party (JIP), the Japan Restoration Party, and the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) of Japan for the relevant elections.Footnote 1

The most intuitive ways to assess candidate performance in a single-member district are the percentage of the vote a candidate gains and whether the candidate won his or her seat. The former provides more nuance as it distinguishes between close contests and massive blowouts, but the latter is arguably more important as it ultimately decides the composition of the legislature. The two dependent variables should not differ drastically so I will focus on whether a candidate wins his or her seat as full data on candidate vote share are only available through 2014.Footnote 2 Data for this analysis come from the Reed-Smith Japanese House of Representatives Elections Dataset (Smith and Reed, Reference Smith and Reed2018), which contains data at the candidate level for all elections between 1955 and 2014 and from the 2017 UTokyo–Asahi Survey (Taniguchi and Shimbun, Reference Taniguchi and Asahi Shimbun2022), a collaborative survey of all candidates running in the 2017 election conducted by the Asahi Shimbun, a widely circulated newspaper, and Tokyo University.

For candidate appeal, I use a dichotomous measure of candidate quality based on whether the candidate previously held office as a governor, mayor, representative in the House of Councillors (Japan's weaker upper house), or a prefectural assembly member. My measure is analogous to Reed et al.'s measure and falls in line with other analyses examining candidate quality (Jacobson, Reference Jacobson2005; Carson et al., Reference Carson, Engstrom and Roberts2007). If candidate appeal is persuading voters, these candidates, by virtue of their experience and greater name recognition, should have an advantage over those without these qualities. While there are other ways candidates could demonstrate their capabilities to voters, holding former office in what I have listed above is by far the most common. Furthermore, while many candidates have held former office, there are many more who have not, providing plenty of variation for the analysis. Reed et al. found that candidate quality was a significant predictor of a newcomer candidate winning an election in the early 2000s, but that this relationship was replaced by party affiliation from 2005 onward (Reference Reed, Scheiner and Thies2012). Their conclusion was that candidate appeal gave way to party as Japanese politics shifted toward more party-based competition, but they expected party competition to continue rather than LDP dominance to return. I expect that candidate quality will make a resurgence in the absence of strong party competition after the 2012 election, but that it will continue to be less influential than party affiliation.

My measure of party affiliation is also dichotomous as LDP or not LDP affiliated. I include candidates from the LDP and DPJ for the 2000 through 2009 elections. For 2012, I add candidates from the Japan Renewal Party (JRP) and TPJ, DPJ splinter parties. For the 2014 election, I include candidates from the LDP, DPJ, and the JIP, the JRP's more conservative rebrand. The TPJ dissolved by 2014 so it did not contest the election. Finally, in 2017 I analyze candidates from the LDP, JRP, and the CDP, the DPJ having fully splintered by then. LDP affiliation should not significantly correlate with a candidate's probability of winning a seat until 2005, replicating Reed et al.'s results. Once it becomes a significant predictor of winning a seat, it should continue to be a significant predictor all the way through the 2017 election. The coefficient should be positive in all years but 2009 when the LDP was the losing party. Furthermore, if party appeal is the main contributor to LDP dominance, the coefficient should exceed candidate quality's coefficient in 2012, 2014, and 2017. Of course, while it is possible that a positive coefficient means the LDP label itself is a boon for a candidate, it is also possible that not being in an opposition party is what motivates a voter to choose an LDP candidate. Thus, while my analysis indicates whether LDP affiliation correlates with greater success at the candidate level, it is agnostic as to where that success comes from: the LDP's innate popularity or the unpopularity of the opposition.

Apart from candidate quality, Japan, like many democracies, has a substantial incumbency advantage. As a result, incumbents should, on average, perform better than non-incumbents. I include a dummy variable to account for this, considering any candidate that holds office in the House of Representatives going into the election an incumbent. The coefficient for this variable should be positive and significant in every election. Of course, part of the story of incumbency in Japan comes from the tendency for senior politicians to bequeath their seats to a successor, creating political dynasties in the process (Smith, Reference Smith2018). However, in addition to these dynasties becoming less frequent over time, many hereditary candidates are in fact quality candidates, having held office in some other capacity before competing for a seat in the House of Representatives. In addition, hereditary candidates possess the advantages of quality candidates like name recognition and resource access. I count any hereditary candidate (a candidate whose relative either through marriage or blood held a seat in the legislature prior to their own run) as a quality candidate in the analysis.

In addition to these key variables on candidate and party appeal, I include other variables that should also significantly influence how much of the vote a candidate wins. In all the elections that I am studying, either the LDP or the DPJ holds the lion's share of the seats. Candidates that are facing incumbents from these parties are likely to have a harder time winning, so I include a dummy variable to distinguish candidates running in an open race from those facing a strong incumbent. The variable's coefficient should be negative in all years.

There is also the issue of coordination failure to consider. Japan's single-member districts are decided by plurality, making vote splitting potentially costly to a candidate's chances of winning. I measure coordination failure by taking the number of candidates running on the same side as a candidate (the ruling coalition for the LDP and opposition parties for the DPJ) and subtracting it from the number running on the opponents' side.Footnote 3 A negative number indicates that coordination failure is lowering candidates' chances of winning a seat.

Finally, like many other countries, Japan has a consistent divide between urban and rural politics. Particularly for rural areas, clientelism helped candidates hold on to power for decades. To account for the possible influence of urban/rural differences I include a measure of the population density of the district in which a candidate is competing.

Taking these variables together, the model I analyze can be expressed as:

With the primary hypotheses:

H1: LDP affiliation will significantly predict a higher probability of winning a seat in 2012, 2014, and 2017.

H2: Candidate quality will become a significant predictor of a candidate winning a seat once more after the DPJ collapses in 2012.

H3: LDP affiliation will have a larger estimate than candidate quality in 2012, 2014, and 2017.

5. Results and analysis

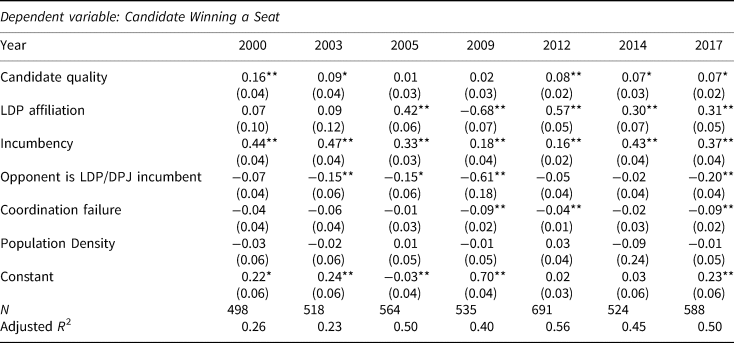

I used probit regression to analyze candidate performance and shown the results in Table 1.Footnote 4 As can be seen in the table, LDP affiliation is statistically significant beginning in 2005 as expected and stays significant from 2012 onward, supporting my first hypothesis. This finding suggests that electoral competition in Japan has continued to be, at least in part, party-based even after the DPJ collapsed.

Table 1. Probit model of quality and party affiliation on winning a seat

Note: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Candidate quality starts as a significant predictor of a candidate's probability of winning a seat in 2000 and 2003, but this fades in the 2005 and 2009 elections just as Reed et al. found. Interestingly, candidate quality becomes a significant predictor once more starting in 2012, supporting my second hypothesis. While I cannot say for certain, I suspect this is the result of a lack of competitiveness between parties, making more room for candidate appeal to factor into voters' decisions.

As for my third hypothesis, the results are not definitive. The point estimate of party affiliation is larger than candidate quality in the 2012, 2104, and 2017 elections, but the confidence intervals overlap in 2014 and are quite close in 2017.

Given the difficulty of interpreting probit coefficients on their own, I also ran the model using ordinary least squares (OLS). While probit is typically used over OLS with dichotomous outcome variables, if the outcome variable is not too clustered around extremes (i.e., almost all candidates are either certain to win or lose), then OLS can reliably provide estimates where the coefficients represent the change in probability (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008; Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2010). Since my data have a range of likelihoods for candidates winning a seat that is sufficient to use a linear probability model, I have provided the results using OLS in Table 2.

Table 2. Linear probability model of quality and party affiliation on winning a seat

Note: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The results from the linear probability model closely reflect the results from the probit model, a sign that the data perform well with OLS. The advantage of the linear probability model is that the coefficients in Table 2 can be interpreted as a change in probability of a candidate winning a seat in response to a unit change in the independent variable. So a quality candidate in 2000 has an increase in his or her probability of winning a seat of 0.16 whereas a quality candidate in 2017 only has a 0.07 increase in the probability of winning.

This model also makes comparisons between coefficient magnitudes possible. Any politician would gladly take a 7–16 percentage point increase in their chances of winning (the range of magnitudes for candidate quality when statistically significant), but this increase pales somewhat in comparison with 30–68 percentage point increase that comes from being affiliated with the LDP. To help visualize differences in the substantive significance between candidate quality and party affiliation, I have plotted the estimates for these variables in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Candidate quality and LDP affiliation on probability of winning.

This plot shows two important takeaways from my analysis. First, candidate quality starts off as significant, diminishes in the wake of big shifts toward party-based competition in 2005 and 2009, and then returns after the DPJ's fumble in 2012. Second, unlike candidate quality, once party affiliation becomes significant, it stays significant all the way through 2017. Its diminished role in more recent elections relative to candidate quality is, again, likely the result of an unexciting field of parties for voters to choose from. Yet its persistent influence on elections even in the presence of LDP dominance reflects just how enduring Japan's shift toward party-focused elections is. Interestingly, 2005, 2009, and 2012 have the largest estimates for LDP affiliation, the respective rise, peak, and decline of two-party competition. The data suggest that, intuitively, when elections revolve around fewer, larger parties, party affiliation becomes more influential in electoral competition.

Another way to assess whether parties or candidates are more important in Japanese elections is to ask voters directly. I have plotted in Figure 2 responses to a series of surveys asking voters to indicate which they found more important – parties or candidates – in casting their vote in a single-member district.Footnote 5 The plot tells a consistent and compelling story that supports my analysis on candidate performance: on average, voters care more about parties than candidates even when they are casting a vote specifically for a candidate. For the first election since Japan adopted MMM, voters indicated that they considered candidates and parties equally important. However, party immediately exceeds candidate by the next election, and this holds true through 2017. The difference between the prioritization of party and candidate again peaked in 2009, the most competitive election with two major parties Japan has ever experienced. Party continues to be important in later elections but has become slightly less so compared with the height of the DPJ–LDP rivalry in 2009.

Figure 2. Voter response to what matters most in casting their vote.

6. Conclusion

The LDP dominates once more through a combination of the return of candidate appeal and, more importantly, through its party appeal. It was far from certain that Japanese politics had fully adapted to party-based elections, especially after its burgeoning two-party system evaporated. Yet the evidence I present here is clear. Candidates' ability to win a seat continues to be dependent on the party even when a competitive opposition is nowhere in sight.

Admittedly, I covered only seven elections and focused primarily on just three (2012, 2014, and 2017). It may be premature to extrapolate from these findings and proclaim that party-focused elections are here to stay, especially when the most recent elections show the relationship between party affiliation and candidate success weakening. However, it is hard to imagine Japanese politics becoming any less competitive than it already is. If party affiliation exhibits statistical significance in 2014 or 2017, there is every reason to expect that it will continue to do so.

This paper answers the question of what is contributing to electoral success after Japan's party system shifted in 2012, and while it establishes party affiliation as a contributor to LDP dominance, it does not explore what it is about the LDP that grants LDP candidates such a consistent advantage. As I said at the outset, my model is agnostic about the LDP having positive appeal, the opposition having negative appeal, or some combination of the two. Being affiliated with the LDP after 2009 helps candidates win seats, even when factoring in candidate-centric advantages like incumbency and candidate quality. Further study is needed to better understand what about the LDP and the opposition as parties that brings voters to choose the LDP election after election in Japan's party-based electoral environment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/TMUQHM

Appendix A

Table A1. OLS model of candidate vote share

Table A2. Comparison of probit results with Reed et al. (Reference Reed, Scheiner and Thies2012) for newcomers only