INTRODUCTION

The Vale of York Hoard was deposited c 927–8, or shortly after,Footnote 1 but the date of manufacture of the cup (fig 1) that contained most of the associated metalwork and coins precedes its deposition by some hundred years. It forms a significant new addition to a closely connected group of six other Carolingian silver vessels (some gilded) and the isolated, unprovenanced lid of a seventh, which come from Fejø and Ribe (in Denmark), Pettstadt (in Germany), Halton Moor (in north-western England), Spain (without further precision)Footnote 2 and another recently discovered Viking-period hoard from Dumfries and Galloway (in south-western Scotland). The first five examples, which were produced from the late eighth to mid-ninth century, are related by form, design and a height of between 80–100mm, although there are stylistic differences, while the sixth, which also has a lid, is taller and more flask-shaped.Footnote 3 A further vessel from Włocławek, Poland, is similar, but is later in date and not always regarded as strictly belonging to the group, since, apart from its figural decoration, it has a foot-ring, highly raised roundels on its sides and may originally have had two handles.Footnote 4 The vessels were produced for church and monastic use, not for commercial trade.Footnote 5

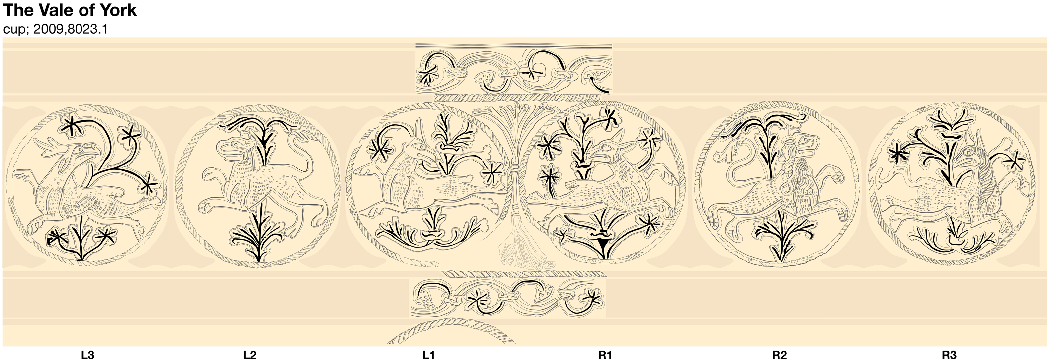

Fig 1. Silver-gilt and nielloed cup from the Vale of York Hoard, showing the stag roundel (L3 in fig 2). Photograph: Saul Peckham, © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

The Vale of York cup may be further related by form and features of its design to a smaller, parcel-gilt cup from Lejre (in Denmark), and to the small, blue-glass-inlaid gold cup from the late Avar-period hoard of Sânnicolau Mare in Romania (formerly Nagyszentmiklós).Footnote 6 The origin of the latter remains uncertain: it may have been produced in a Byzantinising eastern Alpine/upper Italian/south Carolingian artistic milieu, possibly even by a Byzantine goldsmith working at the Avar court.Footnote 7

The cup from Sânnicolau Mare has been variously dated from the late eighth century to c 800 (by Wamers), to the ninth century, or to the second third of that century at the earliest (by Schulze-Dörrlamm);Footnote 8 the hoard itself was deposited most likely around 800, or in the early ninth century. The Vale of York cup is decorated round the sides with six cable-bordered roundels, each containing a single animal chased in low relief and running, or leaping, in front of a centrally placed tree (behind the two felines), or a more bush-like plant (behind the other animals); the roundels are separated by fans of acanthus foliage at either end of vertical stems. The animals’ hair, or fur, is shown by curved rows of punched hatching. Continuous vine scrolls run round the vessel above and below the roundels, demarcated from them by raised and incised cable-patterned borders.

The iconography of the cup has been discussed by Wamers, who considers it highly likely that certain of the animals can be paralleled in illustrations in the Stuttgart Psalter (or perhaps a similar, now lost exemplar) written and probably also illuminated at St-Germain-des-Prés c 820–30, which illustrate Psalm 148 (verses 1–13).Footnote 9 A Christian interpretation is reinforced by other aspects of the design (see below) and, if the cup had been produced as one of a set, the animals may have had further significance as part of the larger group.

THE FORM OF THE CUP

The cup is of globular form with a plain flat base, a short upright neck slightly flared at the junction with the body and a thickened, slightly everted rim that is hammered flat on top (diameter: 120mm [max]; height: 92mm; weight: 370.6g; approximate metal composition [at rim]: 75–8 per cent silver, with copper, zinc and lead).Footnote 10 Traces of mercury gilding were detected on the outside, both in the incisions on the bodies of the animals and on the ground, while the interior is completely gilded. The stems, leaves and grapes of the plant and vine scroll motifs were enhanced with niello inlaid in grooves or dots, but only remnants survive in the upper half of the cup. There is a dent on one side, just above the base.

The cup has no handle, although originally it probably had a lid like those on the vessels from Spain and the Galloway Hoard. The Spanish exemplar is of the same form as Vale of York and is also decorated with vine scrolls, birds and acanthus, but without the encircling roundels, and was probably made around the mid-ninth century in Lotharingia within the circle of the Metz/Reims centres for Charlemagne’s programme of classical renovatio.Footnote 11 The knob of the lid of the vessel from Spain, with its four leaves of acanthus, may be compared with the quatrefoil rosette on the base of a Byzantine, nielloed silver dish dated 527–65 from the Gavar, formerly Novobayazet, region (in Armenia).Footnote 12 Lids were added to western vessels for ecclesiastical use. The unprovenanced, contemporary (or later) lid from another such vessel, decorated with acanthus leaves, huntsmen and animals, is kept in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York).Footnote 13 Indeed, it is surmised by Wamers that the gaze of the six Vale of York animals, particularly of the stag and lion, was focused on ‘the original lid, which may have had a cross-shaped knob for a handle, or some other symbolic, or even figural, depiction of Christ’.Footnote 14

The lids and internal gilding suggest that the group of related vessels may originally have been for liturgical use; for example, as pyxes for containing the consecrated bread of the Eucharist or as containers for chrism or incense, the contents being kept from contact with baser metal by the gilding.Footnote 15 Their later Viking possessors may have been aware of their spiritual significance and reused them as treasured containers for serving out drink; it has been further suggested that they may have discarded the redundant lids and cut them up as hack-silver, reflecting the cups’ change from ecclesiastical to secular use.Footnote 16 There is a patch of slight abrasion on the base of the Vale of York cup, while the exterior gilding is partially missing and may have been deliberately removed for reuse, unless its loss was just through wear and tear or rough cleaning. But it is notable that the gilding on the base of the Spanish cup also appears to have been rasped or filed off.

THE DECORATION OF THE CUP

The animal motifs of the Vale of York cup are presented in a balanced, asymmetrical composition of two groups of three developing to the left and right of, and including, two back-to-back running deer/antelope/unicorns with their heads turned back to face each other (fig 2, L1 and R1).Footnote 17 In the left-hand group the central roundel (L2) encloses a large, leaping feline to left (either a lioness forming a pair with the lion in the central roundel of the right-hand group (R2), or perhaps a pard or panther without distinguishing stripes or spots), which chases a stag in the next roundel to the left (L3). In the central roundel of the right-hand group (R2), a lion chases an equine in the next roundel to the right (R3), which is probably an Asiatic wild ass, or onager, rather than a horse, since the latter does not feature in extant bestiaries before the late twelfth century.Footnote 18 Even when a horse appears in a miniature of the ninth-century illuminated copy of the Physiologus in the Berne Stadtbibliothek), which may date from around the 830s–40s, it is shown with a rider on its back.Footnote 19 The two big cats face forwards, as if to their intended prey, while the other animals face backwards. It may be significant, however, that the former do not pounce on the latter, as distinct from more typical hunt scenes, nor are human figures or hounds depicted.

Fig 2. Rolled-out drawing to show the decorative roundels and representative central sections of the other panels of the Vale of York cup. The numbered letters ‘L’ and ‘R’ beneath the roundels indicate the ordered placing of the latter, respectively left and right of the centre line. Drawing: Stephen Crummy.

The ‘spandrels’ between the roundels are filled above and below with fans of acanthus foliage on long stems. The stems extend between the roundels and are joined at each end by double or triple-ribbed collars, except where the roundels with the stag and onager are closed up.

Round the neck and base of the cup run two bands of vine scrolls with W-shaped, double collars at the nodes with the stems and heart-shaped bunches of dot-punched grapes alternating with lobed leaves. The grapes in the upper scroll are indicated by four or five punched dots, while those of the lower one show six or seven. The bands are demarcated from the roundels by cable-patterned cordons, while a narrower, plain cordon stands between the band on the neck and the rim. Traces of niello remain in the veins of the leaves and in the median grooves in the stems of both the leaves and the clusters of grapes. The use of niello to pick out details in this way is comparable with the cups from Halton Moor and Włocławek (see below).Footnote 20

ORIGINS OF THE FORM

The broad-bellied form with raised neck of the Carolingian group of vessels has no earlier parallels in the West. On the one hand, it may be compared with an early seventh-century Byzantine silver censer from Egypt, except for its foot-ring, while Marschak, on the other hand, indicates Turkic models of similar date.Footnote 21 Wamers has drawn a comparison with certain Byzantine silver and copper-alloy ecclesiastical vessels such as chalices and thuribles of the sixth to seventh centuries, mainly from Italy, Syria or the Syria-Palestine region.Footnote 22 On the whole, though, and significantly lacking the decoration of animals in roundels (see below), they do not appear to provide such close parallels as the Oriental vessels, which are also closer in date to the Vale of York cup. In addition, it seems highly unlikely that church plate would have been traded with the West, whereas at least four secular Oriental vessels do appear to have been. The known vessels are: an ‘Eastern’ (Persian?) silver bowl from Terslev in Denmark; a small undecorated cup from the late tenth-century seeress’s grave 4 at Fyrkat in Denmark, of globular form with collared vertical neck more like a miniature version of the Vale of York cup or an eastern Iranian handled bowl from Azov; a plain copper-alloy bowl originating from the Middle East/Persia or Central Asia (close in form to the eastern Iranian bowl from Azov noted in the next section); and a jug from a cremation grave of the early tenth century from Klinta (in Öland, Sweden).Footnote 23 The original presence of handles on the cup from Włocławek further favours an Asiatic over a Byzantine derivation (see below). The origin of the sets of small silver cups from Fejø, Ribe, Terslev, Lejre and single examples from other sites in Scandinavia is harder to define and they may be locally made, although Russian parallels are noted by Wilson.Footnote 24 Other early Oriental and Islamic types of artefact are known from early medieval Scandinavia.Footnote 25

There are two other vessels to be considered in this context: the Sasanian ‘Chosroes’ bowl of gold cloisonné with rock crystal, glass and semi-precious stone (also known as the ‘Tasse de Salomon’), which dates from the sixth or seventh century and seems likely to have been a diplomatic gift associated with the embassies from the Abbasid court in Baghdad to Charlemagne and Louis the Pious at Aachen at the end of the eighth and early ninth century, if not before; and possibly also the Sasanian silver-gilt dish showing a king hunting on horseback who is probably Yezdegerd iii (632–51), and a carnelian cameo with the head of another king.Footnote 26 Other Oriental metalwork, which certainly reached the West at this time, includes the famous mechanical brass water-clock and two brass candlesticks given by Harun al-Rashid to Charlemagne.Footnote 27

In line with such imports, the prototypes for the form of the Vale of York cup and others in its group appear to be provided by Byzantine-influenced, Oriental silverware in Sasanian and post-Sasanian tradition rather than by Byzantine metalwork per se. It can be seen that the production of metal vessels in Central Asia began to flourish after the Arab defeat of the Sasanids in 642, while traditional Sasanian vessel types still continued to be made by conservative craftsmen in the region of ancient Iran.Footnote 28 For example, although the Vale of York cup never had a handle, its body profile and size may be closely paralleled by one of the three main forms of Oriental silver: the single-handled ‘kantharos’ of Marschak’s School B used in Central Asian and Avar metalware of the seventh to eighth centuries, which in turn appears to have had its roots in Roman silver and shows close links with Sogdian and Central Asian pottery of the end of the seventh/early eighth century. Handled silver cups with globular form and upright necks, with or without foot-rings, like the example from the mouth of the Don noted below, are assigned by Marschak to his School B, which is connected with Sogdiana/Sogdia and its vicinity, the Persian region centred on the city of Samarkand. Sogdiana was an important centre of silver-working in the transmission of types from east to west. The second phase of output from the School dates from the end of the seventh/earlier eighth century, but its first phase appeared already in the sixth century even before the Arab conquest; cf the pottery cups from graves in Russia, Latvia and the example from Hemse annexhemman (in Gotland, Sweden), which were probably imported from northern Iran via Russia.Footnote 29 Indeed, the pottery cups underline the very groundedness of the form in Central Asia, the antiquity of which is demonstrated by comparison with a gold cup with zoomorphic handle of the first century ad from the Khokhlach barrow near Novocherkassk.Footnote 30 Like the cup from Włocławek, the Sasanian silver vessels are provided with handles and some also with a foot-ring.Footnote 31 These parallels have led Skubiszewski to derive the form of the Polish cup from Sasanian models, further comparing the half-animal half-human head in relief, which supported one of its two lost handles, with masks on the pottery of Khotan and the costume of its figures with early Persian dress.Footnote 32 The absence of handles on the Vale of York cup does not therefore present a serious obstacle to the derivation of its form from Central Asia. Indeed, Shetelig observed that the animal panels of the related Halton Moor cup were reminiscent of Sasanian work.Footnote 33

CONTEMPORARY PARALLELS FOR THE FORM

Sasanian and post-Sasanian silverware is especially common in finds from north and south Russia; for example, an eighth- to ninth-century eastern Iranian/Central Asian handled wine-cup with foot-ring from Tomyz’, Kirovskaya obl, and an eastern Iranian handled example without foot-ring from Azov.Footnote 34 The small group of apparently derivative western European vessels, to which the Vale of York cup belongs, was made in workshops of the Carolingian Empire and an artistic ‘homeland’ for it in the region between Lotharingia/West Francia, Saxony and Swabia has been proposed.Footnote 35 Both the Vale of York and Halton Moor cups may have been produced specifically at the monastery of St-Germain-des-Prés (see above).

The closest parallel to the Vale of York cup in both form and design is the silver-gilt and nielloed cup from the Halton Moor Hoard, which is only marginally taller (95mm), is similarly decorated with single animals in roundels and has scrolls round the neck and base with W-shaped collars (although of acanthus rather than vines). Although the Halton Moor Hoard was deposited in the mid- to late 1020s, the production of its cup is contemporary with the Vale of York cup and it was manufactured in a Carolingian workshop during Lennartsson’s phase ii (style group vi) dating from 830/40 to c 900, while Wamers suggests c 820–50 and the second quarter of the ninth century for Vale of York.Footnote 36 As the close similarity of their ornament and motifs strongly indicates, both vessels must certainly have been produced in the same workshop, if not even by the same hand, so may have formed either a non-matching pair, or part of a larger set. The cup from the Vale of York possibly represents loot from a church or monastery in the northern Frankish Empire, which was often raided by the Vikings during the ninth century, or else was surrendered as tribute, and the Halton Moor cup may have been taken from such a location in Normandy.Footnote 37 Webster alternatively argues that both of the cups ‘may have come to England not as Viking loot from raids in northern France, but as part of a set of grand altar vessels brought here in the reign of Alfred or his father’.Footnote 38

The cup from Włocławek, which, like the examples from Vale of York and Halton Moor, is decorated with sprigs of acanthus and scenes in roundels round the sides, is closely connected with the Carolingian group, but is somewhat atypical, especially as its four roundels are raised and the scenes depicted on them and in the intervening spaces form a narrative cycle illustrating events from the life of Gideon. Opinions on its dating vary, although they tend to agree on west Frankish manufacture; Lennartsson includes it with the cups from Spain and Halton Moor in her phase ii (style group vi) dated from 830/40 to c 900, and Wamers has opted for a probable mid-ninth-century date; but the tenth century is suggested by Skubiszewski, who would place it probably before the 970s, relating the style of its distinctive narrative scenes to the lid in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.Footnote 39 Form and bossed roundels apart, the Western style of its decoration, which reflects late and post-Carolingian artwork, especially of the tenth century, is quite independent of Oriental models, except for the elements of Sasanian rather than Carolingian-derived acanthus and the surviving head-shaped support for one of its originally two handles. The scenes from the life of Gideon diverge from the middle Byzantine version of the iconography and are probably drawn directly from a Western illuminated manuscript.Footnote 40 The representation of human figures further distinguishes the vessel from the main group and may be another indication of a late date, in view of which Skubiszewski now considers it unlikely that it would have served as an eucharistic chalice. He ascribes it to a workshop loosely located in the region between Swabia, Franconia, Saxony and Lotharingia, suggesting that it was probably brought to Poland by a missionary from the West in the late tenth century.

TECHNICAL PARALLELS

The techniques of parcel-gilding and chasing in low relief on the Vale of York and Halton Moor cups are both employed on a sixth- to seventh-century Sasanian silver dish from Klimova (in Perm), which has on the base a striding tigress standing in front of a tree that bears a striking resemblance to the big cat/lioness on the former vessel particularly.Footnote 41

ORIGINS AND PARALLELS FOR THE ROUNDEL FEATURE

The animals portrayed on the Vale of York cup, especially the lion(s), stag and deer, are so common in early Asian, classical and late antique art that it is difficult to trace directions of influence. The cup’s portrayal of single animals set against a reduced landscape of a single tree, all enclosed by roundels, however, does appear to be sufficiently distinctive to warrant closer investigation, especially in view of the suggestive parallel observed above in slightly earlier Iranian/‘Sasanian’ silverware. As early as the fourth century ad, a horseman is portrayed in a roundel on a tapestry fragment from Egypt and another on a seventh-century Coptic tapestry roundel, while two birds are shown affronted within a more angular roundel on a Coptic version of a Sasanian fabric.Footnote 42 In the British Museum there is a Sasanian(?) silver-gilt bowl of the fifth to sixth century decorated with five plain-bordered roundels enclosing male heads from the former North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan (the main part of the recently renamed province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).Footnote 43 The circle appears to have had symbolic importance for the Parthians and Sasanians, appearing as pearl collars and diadems on their coins and textiles, while heraldically arranged creatures in repeating pearl roundels were arguably the most influential in weaving history.Footnote 44 Unfamiliar creatures within roundels appeared on figured ‘Sasanian’ silks of around the seventh to ninth centuries and became diffused outside Persia in the eighth and ninth; for example, from Antinoë (in Egypt).Footnote 45 A pair of equines (horses or onagers) and a central tree are shown within a roundel on the sixth- to seventh-century Eastern Mediterranean ‘Dancer’ silk at St Maurice and on another without an intervening tree of the late eighth to ninth centuries from Sens, while the ‘heraldic’ pairing of creatures in mirror image is usual on textiles as a device used for ease of weaving.Footnote 46 In this later period, rows of large, almost contiguous medallions enclosing animal and human figures were popular with silk weavers.Footnote 47

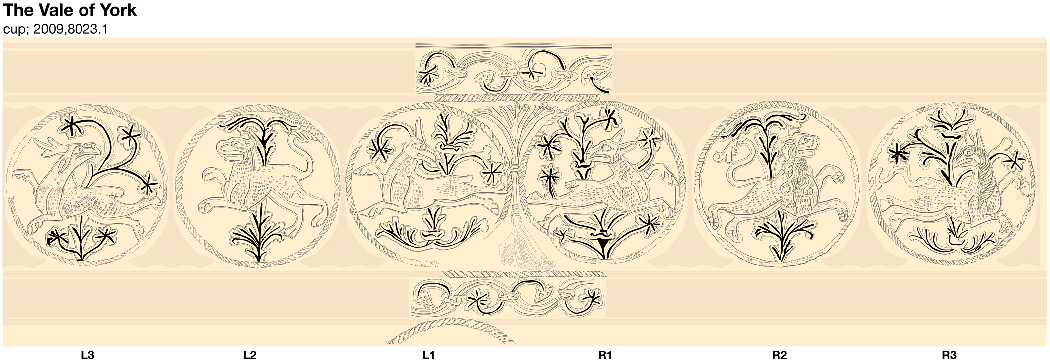

The question of the Asiatic or Byzantine origin of the later textiles has long been controversial, although recent scholarship has again brought the possibility of Eastern-influenced Byzantine manufacture to the fore, as argued earlier by Grabar (see further below).Footnote 48 Brøndsted also concluded from the combined evidence of Persian and Egyptian fabrics and Syrian sculptures and mosaics that the disposition of animals in circles derived from the East (Egypt having come under Sasanian dominion in the seventh century), although the inspiration may ultimately have been classical, as reflected in Roman mosaics.Footnote 49 Skubiszewski similarly proposed an Oriental origin for the form of the roundel compositions in the later metalwork and further noted the inhabited scrolls of Byzantine mosaics, which may assume the form of roundels, as on a mosaic at Madaba in Jordan where two scroll/roundels enclose a hunter and a tiger(?).Footnote 50 Animals standing or lying in front of trees are depicted in medallions inside the bases of Sogdian silver dishes of Marschak’s School B from the later seventh century (for example, from Cherdyn and Volgina, in Perm) and unprovenanced.Footnote 51 But, single animals shown in cable-bordered roundels (although without trees) round the sides of vessels, as on the Vale of York and Halton Moor cups, appear to be a slightly later development, as on the post-Sasanian eastern Iranian/Central Asian eighth- to ninth-century silver cups with and without handles from the mouth of the Lower Don (but shown lying down) (fig 3) and Azov, and on a lamp of the second half of the eighth century from Turusheva, Kirovskaya obl.Footnote 52 It has been suggested that, notwithstanding their iconographic significance, the animal motifs of the Halton Moor cup, the Ada group of manuscripts, the Godescalc Evangelistary (781–3) and several of the animals in the chief manuscripts of the Tours School may be Sasanian in origin, or copied from Oriental carpets.Footnote 53

Fig 3. Silver handled cup from the mouth of the River Don, Russia. Photograph: author.

IDENTIFICATION OF THE PLANT AND ANIMAL MOTIFS

Stylised trees divide the animals in wild pursuit round the sides of vessels from Perm of Marschak’s School A (with Sasanian roots), produced around the mid-eighth century and earlier in Sogdia, or in Sogdian tradition at Merv.Footnote 54 They may represent the sacred ‘Haoma/Hom’ tree of the Persians, which appears on many real or imitated Persian silks at various periods into the Middle Ages.Footnote 55 The acanthus leaves on the Vale of York cup replace the lotus-like leaves of these Oriental vessels, while the palmettes between its roundels are foreshadowed by the palmettes in a similar position on the cup from the mouth of the Lower Don and by the plant motifs on the lamp from Turusheva noted above. These foliate motifs may not, however, be purely ornamental, but, like the vine scroll, may also have had a religious significance; the acanthus plants of the Halton Moor cup have been interpreted as symbolising Christ as the ‘Tree-of-Life’.Footnote 56

Already in the Sasanian period of the fourth to fifth centuries, animals of different species, such as lions and leopards, were being depicted on a series of metal bowls portraying kings hunting wild beasts on horseback.Footnote 57 In addition, tigers, stags and onagers (the latter native to northern Iran) all appear, among other beasts, on Sasanian silver vessels.Footnote 58 The variety of animals depicted on the Berlin hunting plate may be intended to suggest not only a game park, but also, at another level, the Sasanian king’s dominion over different territories, if it is accepted that the animals had particular meaning – for example, the lion as a symbol of Iran.Footnote 59 Lions are also depicted in royal hunt scenes on Persian silk textiles of c 600/earlier seventh century.Footnote 60

In consideration of the parallels for the animals depicted on the Vale of York cup, it seems natural to begin with the lion, as the king of beasts, which also occupies a central position in its group of three (fig 2, R2). For example, a lion is shown attacking a bull on a dish of the end of the seventh/earlier eighth century from Komarovo (in Perm),Footnote 61 while lions attacking stags are an ancient motif, appearing in both Persian and Achaemenid Greek art, and at some stage they entered Byzantine art, perhaps through classical intermediaries; for example, on ‘Hunter’ silks of the eighth to ninth centuries from Reims and the Caucasus.Footnote 62 Lions (or tigers?) are also shown, for example, in two sets attacking other quadrupeds on possibly Sasanian-influenced silks of similar date at Nuremburg and Berlin, while prowling lions appear in roundels on the ninth- to tenth-century Ravenna silk of Byzantine origin.Footnote 63 Parallels can also be observed with Central Asian (Bokharan) and other Byzantine textiles and here the latter appear to have exerted a strong influence on the former from the seventh to tenth centuries.Footnote 64

The lioness, or large feline, depicted on the Vale of York cup (fig 2, L2) may similarly be compared with depictions on silverware and textiles. A standing lioness suckling two cubs in front of a tree is shown on an eighth-century silver dish in late Sasanian tradition from Onoshat (in Perm)Footnote 65 and a tiger is clearly shown in front of two trees on a late Sasanian/Sogdian gilded and nielloed silver dish of the late seventh to eighth century from Russia.Footnote 66 A striding tigress appears on the late Sasanian dish of the sixth to seventh century from Klimova, as noted above, while a striped quadruped, probably also a tiger, is shown on a post-Sasanian dish of the eighth to earlier ninth century from an unknown Russian findspot.Footnote 67

Other big cats feature more in textiles; for example, leopards in pairs on Persian silks of c 600/earlier seventh century, and panthers being attacked by dogs occur on the possibly Byzantine Milan silk of the seventh to eighth century.Footnote 68 It appears, however, that the large feline shown without stripes or spots on the Vale of York cup depicts a lioness paired with its mate in the corresponding opposite roundel.

The motif of stags being attacked by lions has been noted above (cf fig 2, L3), while a stag is depicted alone in front of a tree on the basal medallion of a lost small Sasanian silver bowl from either Volgina or Rozhdestvenskoye (in Perm).Footnote 69

The equine in the opposed roundel on Vale of York (fig 2, R2) is likely to be a wild ass or onager, as suggested above. The attachment plates of most Sasanian ewer handles take the form of onager heads and a king lassoes an onager on a silver-gilt plate from Nizhni Novgorod.Footnote 70 An onager, or perhaps a horse, is depicted in front of a tree on the basal medallion of a Byzantine silver-gilt dish from Sludka (in Kama, Russia), with a control stamp of Justinian i (527–65), which may have been produced in Constantinople, or perhaps Egypt, and resembles certain Sasanian vessels in the style of its composition.Footnote 71 In Byzantine textiles, onagers are shown under attack by lions on the eighth-/ninth-century Milan ‘Hunter’ silk, and a Byzantine copy of a Sasanian/Persian subject shows a king miraculously killing both a lion and an onager with a single arrow.Footnote 72 Horses do seem to be shown on Eastern Mediterranean textiles of the sixth to seventh centuries (for example, drinking at a trough in a pastoral scene on a silk at St Maurice) and a pair of either horses or onagers occur with a central tree motif in a roundel on the ‘Dancer’ silk there.Footnote 73 But in Central Asian silverware, horses are usually with riders, or just saddled or grazing, rather than simply displayed alone.Footnote 74 The identification of the pair of back-to-back deer-like creatures at the centre of the composition of the Vale of York cup is more problematic (fig 2, R1 and L1). The one on the right (R1) has two pointed ears and cloven hoofs, so probably represents a hornless hind, but the animal on the left (L1) may represent a deer, an antelope or possibly even a unicorn. It is a little unclear whether it is shown with one pointed ear springing from the forehead at the front of the head and the other with a rounded tip at the back, because the metal is damaged at the end of the latter ‘ear’, although it does appear to be rounded in the X-radiograph. The animal may be compared with the stag, which is shown with one pointed and one more rounded ear, and all the other animals are shown with both ears. On first impression, therefore, the animal may be identified as a second deer, pairing with the first. On the other hand, it might be suggested that the pointed frontward ‘ear’ is meant to indicate a horn – unless it is shown in profile view with a second horn hidden behind the first, in the same way as only one of the stag’s antlers is shown. If the animal is to be understood as having two horns, it might alternatively represent an antelope, but, if a single-horned creature is indeed intended, it may represent a unicorn (or monoceros).

ORIGINS AND PARALLELS FOR THE ANIMAL MOTIFS

It would thus appear from the above parallels, and from Brøndsted’s study of early medieval animal ornament between the seventh to eleventh centuries, that the animals of the Vale of York and Halton Moor cups are based on Oriental models. The theme of the chase depicted on the former, however, probably derives ultimately from late Roman art, including mosaics and marble furniture, although the exact contribution of antique tradition is difficult to define.Footnote 75 For example, chase and hunt scenes, which are common to both sacred and profane symbolism, are frequently sculpted on marble table tops produced in the Eastern Mediterranean around the late fourth and early fifth century, such as one from Hama, Syria.Footnote 76 The theme is further illustrated by the hunt scenes on Roman silverware, which may include a human element – for example, around the bowl from the Traprain Treasure (in Scotland), on which three groups of wild animals pursue each other, separated by two human heads.Footnote 77 The animal conflicts in Oriental art, however, tend to concentrate more on the physical struggle between the beast of prey and its victim than on the chase. As with the vine scroll, the animal motifs and their arrangement, too, would appear to represent a subtle amalgam of stylistic influences from both Oriental (particularly Sassanian and Persian) sources and from late classical art.Footnote 78

TREE AND ANIMAL COMPOSITIONS

The distinctive superimposition of single beasts on trees placed centrally behind them, as shown on the Vale of York and Halton Moor cups, echoes an ancient form of composition that may perhaps be traced back to Roman mosaics; for example, the boar, bear and elephant in front of trees in the radiating compartments on the Orpheus mosaic from Horkstow, or the stag, lion, leopard, tigress(?), hound(?), horse or griffin, elephant and boar in similar compartments on another Orpheus mosaic from Winterton villa, both in north Lincolnshire and dated to the mid-fourth century ad.Footnote 79 As the depictions of elephants most clearly show, the designs appear to have been taken from copybooks of Mediterranean origin. The placement creates a reduced landscape effect of animal and tree within a unified space, as observed with regard to Sasanian representations, too.Footnote 80 Stags and deer are shown also in scenes in front of a tree or trees, which may have a Christian explanation, in the lateral rectangular panels and three of the lunettes on the Hinton St Mary pavement, although in this case being pursued by hounds.Footnote 81 The late fifth-/early sixth-century mosaic of Leontius at the villa of Awzaʿi (in Lebanon) depicts a leaping lion and bull, each in front of a tree.Footnote 82 Similar compositions appear to occur contemporarily, or slightly later, in metalwork. Lions and leopards pursue and attack stags, rams, etc in front of stylised palm trees around the sides of the late Roman bowl from Traprain Law, mentioned above. A grazing equine is depicted in front of a tree on the basal roundel of the dish from Sludka (in Perm, Russia) (also mentioned above). The control stamp of Justinian i on the dish indicates an Eastern Mediterranean origin for the motif, whether Constantinople, or Egypt. A single running quadruped is portrayed in front of a tree on the base of a late seventh-century Sogdian dish of unknown provenance and inside the bases of slightly later silver Sasanian dishes and Iranian silverware of the eighth to earlier ninth centuries (for example, a tiger in front of a tree and facing a bush with lotus-like leaves or flowers, a tigress in front of a tree facing a bush, or stags in front of trees).Footnote 83 There is a lioness and cubs in front of a tree on the dish from Onoshat and the lion savaging a bull in front of a tree on the dish from Komarovo (see above). A tiger is depicted in front of two trees on a late seventh-/eighth-century, possibly Sogdian, silver-gilt and nielloed dish in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.Footnote 84

On silks of the seventh to eighth centuries of Muthesius’s Zandaniji group 1, lions and rams are shown for technical reasons in facing pairs with trees between them rather than behind (as noted above) – for example, from Huy and Nancy – while facing pairs of equines, but without intervening trees, occur on silks of Zandaniji group 2 of the late eighth to ninth centuries – for example, from Sens.Footnote 85

ORIGINS AND PARALLELS FOR THE VINE SCROLLS AND CORDONS

Antecedents for the vine scrolls in friezes round the necks and bases of the Vale of York and Halton Moor cups can be found in the vine-shoot or acanthus-like palmette friezes found around the necks of eastern Iranian/Central Asian cups such as the example from the mouth of the Lower Don noted above.Footnote 86 But its specific form in Carolingian art, particularly in metalwork, has been derived by Wamers from northern English decoration of the late seventh to eighth century, which was taken to the Continent by the Insular mission.Footnote 87 In a way similar to that by which the vine scroll became blended with the acanthus, it may have been further strongly influenced by the regularised vine scrolls of a type developed in the Eastern Mediterranean region, which is ultimately of late classical origin, although conventionalised by the Eastern sense of style, according to Brøndsted.Footnote 88 The connecting collars of the vine scrolls on the Vale of York cup clearly relate them to the vine scrolls of other Carolingian artwork, while those on the cup from Spain have been compared with examples in manuscripts and ivories produced at the School of Metz.Footnote 89

The Vale of York cup’s plain cordon above the scroll around the neck and the broader, cabled cordon beneath it have been compared with the cordons around the neck of the late eighth-/ninth-century cup no. 19 from the Sânnicolau Mare/Nagyszentmiklós Hoard and the more or less contemporary example from the Halton Moor Hoard.Footnote 90 Similar cordons appear, too, on Oriental vessels.

THE TRANSMISSION OF ARTISTIC MOTIFS FROM THE EAST

Scenes from classical Greek and Roman myths occur in repoussé on certain Iranian silver bowls, which raises the question of whether there was direct Central Asian–Mediterranean contact in late antiquity, or whether the Mediterranean secular elements had already been imported in the Hellenistic, or earlier Roman, period and merely evolved locally in Central Asia, subject to local interpretation and revival of native tradition. Mango concludes that it appears that Mediterranean silver entered Central Asia after the second to third century, during and/or after the fourth century, and it is more likely that the decorative influences were initially from the West to the East, especially as there is only one Sasanian silver plate known from the Roman Empire. As she further observes, it is difficult to imagine the separate, parallel and simultaneous developments of so many features in both West and East.Footnote 91

Byzantine silver reached Central Asia either by a northern route via the steppe, or via Persia acting as a ‘middleman’; or else by a largely dismissed or neglected southern route to India and Ceylon. Egypt or Nubia may have bridged the gap between Mediterranean and Oriental silver down to the seventh century and into the Islamic era.Footnote 92 Byzantine plates with crosses at the centre could have appealed to Nestorian merchants, who carried their version of Christianity from Iran to Middle and Central Asia, then on to China.Footnote 93 One Central Asian imitation of late antique silverware appears to have been traded as far as China; a ewer from Guyuan, from the tomb of a general who died in 569, suggesting direct East Roman–Central Asian contact in the sixth century, possibly in connection with the silk trade.Footnote 94 Jewish merchants, called radhaniyyah in Arabic sources, travelled from the Eastern Mediterranean as far as China – either via India or via Khazar lands across the Caspian to Transoxiana and onwards – probably as much as several centuries before they were first documented c 850, or a little earlier when known as the Radhanites.Footnote 95 International trade and other contacts, such as diplomatic gifts between the Roman/Byzantine Empire and contemporary Oriental civilisations, should also be considered, while it is on record that Sasanian silks were captured by the Byzantines in 628.Footnote 96

Silverware may, therefore, have been used as an export currency by silk merchants; for example, some two dozen pieces of mostly date-stamped Byzantine silver plate of the sixth to seventh century have been found in the Kama region north of the Volga, having originally travelled from the Empire to Central Asia before being taken farther on to Northern Russia in the ninth to tenth century.Footnote 97 Two of them have Central Asian (Sogdian or Choresmian) names scratched onto them. During the sixth to early seventh centuries, Persian silver vessels, too, as well as Persian and Byzantine silver coins, reached the Vyatka-Kama region through trade rather than through non-commercial activities, with the Khazars acting as intermediaries between the Vikings, Finno-Ugrians and the Islamic world in the ninth to tenth centuries.Footnote 98 Noonan connects most of the silver finds from the Kama–Urals with the Fur Route from the north to Central Asia, which most probably existed before the mid-sixth century and entered a new period when West Turkish overlords and Sogdian traders sought to expand the markets for the silk they had obtained.Footnote 99 He sees this as leading to active commerce with Byzantium and making available in Sogdia and Kwarezm the three groups of Byzantine, Sasanian/Iranian and Central Asian silver vessels for export to the north, although the main share of the eastern vessels does not appear to have reached the Ural region until after 800.Footnote 100 The trade in silver is likely to have been favoured by the Abbasid dynasty’s ousting of the Omayyads around 750, followed by the transfer of the capital eastwards from Damascus to Baghdad.

Motifs of Sasanian origin appear to have continued in metalwork for a while after the final Arab defeat of the Sasanian Empire in the mid-seventh century, making them difficult to date precisely, but possibly at least as late as the ninth century, while members of the nobility may have continued to patronise imitations of royal Sasanian plates free from the influences of the conquerors.Footnote 101 In textiles, too (as well as jewellery, ceramics and historiated glassware), the Sasanian royal tradition appears probably to have continued some while after the Islamic conquest, the Arabs taking over Sasanian textile factories and continuing to produce the customary repertoire in Sogdia, itself conquered in the earlier half of the eighth century (Transoxiana, now Tajikistan/eastern Uzbekistan) with Samarkand falling in 712.Footnote 102 As noted above, the animals of the Halton Moor cup may be Sasanian in origin, copied from Oriental carpets.Footnote 103

The ornamental motifs of Iranian and Central Asian metalwork and other luxury goods were widely disseminated in Asia and eastern Europe between the eighth to tenth centuries. They can be paralleled by the designs employed in Byzantine and Central Asian silk weaving, which clearly show mutual influences at work in spite of commercial competition, although the limited survival of the evidence makes it more difficult to identify the direction of flow. There is debate among specialists whether any surviving silks can be identified as specifically Sasanian, although later versions prove the popularity of their style.Footnote 104 For example, the hunter motifs of Byzantine textiles may be based on putative Sasanian prototypes and Sasanian patterns and motifs may have entered the repertoire of Byzantine weavers during the sixth to seventh centuries, when there were significant contacts between the Byzantine and Sasanian empires. Sasanian textiles in the early Middle Ages became a model for the rest of the known world, and materials with animal motifs, generally shown singly, are the most common of all surviving Sasanian textiles.Footnote 105 It seems possible, though, that these weavers looked also to classical motifs and only incorporated Sasanian elements where so desired. In the early ninth century, after the Arab invasions, their choice may also have been influenced by gifts of textiles from the Abbasid rulers to envoys, and the exchange of technical ideas and iconographic themes seems to have continued with little control between the imperial workshops of Constantinople and their counterparts in Central Asia and the rest of the Islamic world.Footnote 106 There is compelling documentary evidence, too, for quite extensive trade, including textiles such as silks, purples and brocades, between the ‘Dar al-Islam’ and Carolingian Europe.Footnote 107

Imperial purple silks that reached the West, where they survive mainly in ecclesiastical treasuries, are likely to have been diplomatic and papal gifts made during the period of close contacts between the Byzantine and German emperors from the eighth to twelfth centuries. Such textiles were then presented in turn by those rulers to churches (for example, the eighth-century hunter silk from Mozac with undoubted Sasanian features such as ribbons tied to the tail of the horse).Footnote 108 The quantities of Byzantine and other Oriental textiles (pallia sirica and ‘Persian silks’) that were imported were huge, according to the surviving inventories and other documentary sources such as the Liber Pontificalis.Footnote 109 These textiles clearly served as models for the decoration of Carolingian and Ottonian manuscripts, while in the medieval period they influenced other media such as wall-painting, mosaics, metalwork and sculpture.Footnote 110 Vikan suggests that Sasanian and early Islamic motifs reached Italy by way of Byzantium.Footnote 111 Commerce may also have played some role. The Jewish Radhanite merchants noted above, for example, established social and cultural relations between Central Europe and Kievan Rus’ and the lands of the Khazars in the Lower Don and Volga, who controlled the trade between Rus’ and the Arab caliphate. Beginning in the mid-ninth century, trading became extensive directly between Carolingian Regensburg and Atil (or Itil), the third capital of Khazaria, rather than via Byzantium.Footnote 112 Farther to the north, the important medieval trade ‘road’ of the Via Regia connected Kiev to the Carolingian centre at Erfurt, as underlined for the ninth century by a stream of Islamic dirhams.Footnote 113 It thence linked onwards to Cologne, Frankfurt am Main and Mainz-Kastel, before branching westwards into France and the Low Countries.

From the eighth century and the beginning of the ninth, the direction of influence as observed in the metalwork was reversed from the East to the West.Footnote 114 It seems likely that the loose network of trade routes known as the ‘Silk Road’, stretching from Constantinople to Syria, would have played an important role in this shift, dominated as it was until the tenth century by the silverware-producing centre of Sogdiana.Footnote 115 Oriental artists and refugees from the Arab invasions working in ‘Syrian’ colonies in France and Italy, whose number was swollen by iconoclastic strife in Byzantine lands between 725–847, may even have produced textiles and small industrial art goods.Footnote 116 Secular Byzantine silverware may have been used as an export currency connected with the silk trade (supra) and, in a similar way, Central Asian models for the Carolingian pyxes could later have been conveyed to the West.

Thus, although classical parallels to the decoration and Byzantine parallels to the form of the Vale of York cup have been remarked above, they are somewhat too early to be regarded as its direct models. It is above all the combination of form, technique and decoration that must be considered as parts of the whole picture, and it is in the chronologically closer Sasanian silverware that all these elements are brought together: the form, parcel-gilding and animals in front of trees within cabled roundels separated by plant motifs.

CONCLUSIONS

As argued above, the Vale of York cup draws on earlier Iranian and Central Asiatic models for its basic shape, the arrangement of cable-pattern roundels enclosing animal motifs placed in front of trees, the selection of species portrayed and the location of a vine scroll pattern round the neck. In addition, the techniques of parcel-gilding of such vessels and chasing in low relief are of sixth- to seventh-century Central Asian origin. There is a good historical context for the transmission of both form and artistic and technical ideas in the diplomatic contacts between the Carolingian and Abbasid courts, and the argument presented above is strengthened by the evidence for extensive two-way trade reaching across Europe and far into Asia at the time. The flight to the West of refugee textile- and possibly metalworkers from the Levant and Orient may also have played a part.

Although the surviving evidence for Oriental vessels occurring in the West is limited as yet, the goldsmith may have had an Oriental exemplar to hand, while it is certain from Carolingian stylistic parallels that the Vale of York cup and the other members of its group would have been manufactured in a Western workshop. The precise location is difficult to identify as yet, although theories suggest one centre somewhere in the region lying between Swabia, Franconia, Saxony and Lotharingia and another in northern France or Normandy. There, the animals and vine scrolls were recast in an entirely Western style, while the element of pursuit from one roundel to the next of carnivores and hunted beasts is more reminiscent of ultimately classical design. As proposed by Wamers, the overall scheme of the iconography of the cup reflects verses of Psalm 148. More specific interpretation is difficult, however, since the cup may have formed part of a set, other members of which may yet be discovered, and for the time being there is no clear, overarching explanation for its symbolism.

More positively, it appears that the selection of the animals on the Vale of York cup was guided by the creatures described in the Physiologus, a contemporary illuminated copy of which exists in the Berne Stadtbibliothek and which probably formed the model for the beasts in the canon tables of the Reims group of manuscripts. The Physiologus would have been well known in ecclesiastical circles, particularly from readings of the works of Gregory and Ambrose. If this hypothesis is accepted, the animals of the cup form a highly significant addition to the few illustrations based on the Physiologus in manuscripts and metalwork that are otherwise known from the early medieval period. In the context of the Vale of York Hoard itself, the cup served as a container for most of the metalwork items and coins and was not cut up as bullion. It therefore appears to have maintained its value as a symbol of status, or even perhaps to have been used as a form of export currency like Byzantine secular silverware (see above).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to his colleague Dr St John Simpson for advice on Sasanian silverware and the reference to the Marschak volume. Further thanks are due to Professor Egon Wamers for advice on the immediate symbolism of the animals; to Professor James Graham-Campbell FSA for commenting on an early draft of this article; to Dr Piotr Skubiszewski and Adam Zapora for the well-illustrated offprints and booklet about the cup from Włocławek and for discussion of continental silver vessel forms and decoration; to Diane Heath for the suggestion that the animals of the Vale of York cup may represent beasts of the Physiologus, in which they are all referenced (pers comm, 5 September 2009), although Professor Jacqueline Leclercq-Marx is more cautious in her advice regarding the symbolism (pers comm, 17 May 2011); to Hero Granger-Taylor for mention of animal motifs on early Byzantine textiles; and to John Ljungkvist for information about Islamic copper-alloy vessels from Viking-period Sweden. The author is indebted to his colleagues Dr Susan La Niece FSA, for reporting on the surface metal analysis of the cup, Fleur Shearman, for the conservation work undertaken for the report to the coroner, Stephen Crummy, for the developed illustration, and Saul Peckham, for photography. The responsibility for any errors is the author’s own.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000358152000013X.