If any group of American blue-collar workers has benefited from the growth of trade it is the unionized dockworkers along the US West Coast. It is estimated that more than 40 percent of US imports pass through the Los Angeles/Long Beach port alone.Footnote 1 Container shipping volumes through West Coast ports tripled between 1990 and 2007, growing at an average annual rate of almost 5.4 percent between 1990 and 2010. Over the same period, the total value of US international trade grew at an average annual rate of 7 percent while the US annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 2.5 percent. Employment, hours worked, and real compensation for West Coast dockworkers grew in tandem. When the credit markets froze in 2008, trade financing dried up, leading to a 20 percent decline in the value of US trade and 15 percent drop in West Coast shipping volumes in 2008–2009.Footnote 2 Dock work opportunities evaporated along with trade flows, dispelling any doubts these workers may have had regarding the connection between their livelihoods and international trade activity. In short, international trade is a primary driver of labor demand in West Coast ports.

While international trade may have abetted the offshoring of manufacturing jobs and the decline of unionization more broadly, an external observer could reasonably expect that dockworkers would support trade liberalization. Nevertheless, the powerful and militant International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), which represents these workers, has opposed trade liberalization for several decades.Footnote 3 Examples of union actions around trade issues include its vehement opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA); its shutting down all West Coast ports to protest the 1999 World Trade Organization (WTO) ministerial in Seattle; and its strong public opposition to the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) as well as new bilateral free trade agreements with South Korea and several Central American countries. To add to the puzzle, dockworkers on the US East Coast, organized into a different union—the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA)—have no history of taking public stands on trade issues.

The large literature on trade policy preferences provides several theoretical approaches to this puzzle. By tracing the union's stance on trade over several decades and using an original survey of ILWU members and nonmembers in Los Angeles/Long Beach, Seattle, and Tacoma, we show that the ILWU's behavior and its members' reported policy preferences are inconsistent with the simple myopic self-interest in which workers support policies that will increase demand for their labor. The preponderance of data is also inconsistent with predictions derived from both major classical models of the distributive effects of trade. The union's position is, however, consistent with the union's “corporate culture,”Footnote 4 which emphasizes broad international worker solidarity with the dictum that “an injury to one is an injury to all.” We compare ILWU members' attitudes toward trade to those of nonmembers with otherwise similar characteristics. We also compare new union members with older cohorts. Union members with longer tenure tend to be more likely to have an opinion about trade policy, to favor restrictions on trade, and to oppose NAFTA when compared to similar nonunion members. Members' policy preferences seem consistent with the organization's position and are difficult to explain without recognizing an ILWU-specific socialization or “treatment” effect.

Our findings in this study indicate that it is possible for unionization to induce members to take on a broader class-based perspective. More generally, the political support for trade may depend not just on voters' structural positions in the economy but also on the organizations in which they are embedded. This study contributes to the growing literature on the determinants of citizen support for liberalized trade as well as the literature on the relationship between unionization, public opinion, and political mobilization. An examination of this case provides evidence that it is possible for organizations to encourage behavior that goes beyond myopic self-interest. Indeed, the ILWU case has something to say about the way individuals develop political preferences more generally.

The organization of this article is as follows. In the first section, we briefly document the expansion of shipping through the West Coast ports in recent years along with the benefits accruing to dockworkers in terms of wages and employment opportunities. In the second section, we review the literature on trade, unionization, and public opinion, identifying how our focus on one union can add nuance to our understanding of attitude formation. The third section lays out the basic expectations for union position taking and union member preferences on trade policy under several competing explanations. In the fourth section, we document the ILWU's stance on international trade over a period of six decades, comparing union behavior with the expectations from trade theory. We collect details on the survey instrument and matching procedures in the supplementary materials.

Employment, Compensation, and Shipping Volumes on the US West Coast

Dock work is notoriously variable, oscillating rapidly between periods of slack and high demand. While macroeconomic trends and seasonal swings drive the average employment levels, there is substantial short-term variation around these averages due to things such as production delays, weather, and the skill of ship captains. Time spent in port is expensive for ship owners. Stevedoring companies therefore require a large pool of labor that can be called upon at short notice in periods of high demand. For their part, dockworkers would prefer predictability. To address these competing demands, the ILWU and employers have developed a system of tiered worker classifications and job rotation/work sharing within tiers. Worker classifications are based on job type (clerk, foreman, “walking boss,” mechanic, etc.) and seniority. The most senior workers, enjoying full ILWU membership rights and first dibs on work shifts are referred to as “Class-A.” The less-senior ILWU members are “Class-B.” The “Casual” pool is called upon in high-demand periods. Among the Casuals, the so-called “Identified Casuals” are those with an ongoing relationship with the ILWU; as they accrue more work hours they become eligible for Class-B membership. “Unidentified Casuals” are individuals who might work just a few shifts on the docks.

The ILWU has long maintained a strong commitment to equalization of work opportunities across members, especially within each tier. The ILWU-controlled dispatch system offers shifts to workers based on seniority and past work opportunities. Workers are never obliged to accept a shift. A declined shift simply passes to the next person in the dispatch queue. The southwest quadrant of Figure 1 illustrates the ILWU's commitment to equalization of work opportunity. The collapse in trade and work opportunities at the end of the 2000s did not show up as a drop in the size of the active Class-A workforce, but the proportion of Class-A workers putting in full-time hours or better declined markedly. Rather than push workers off the rolls, ILWU members shared the pain.

FIGURE 1. Shipping volumes, longshore employment, and longshore earnings for the US West Coast and US trade

Notes: Data from the American Association of Port Authorities 2011, Pacific Maritime Association various years, World Bank 2012

Figure 1 displays how demand for dock labor is clearly tied directly to trade volumes. In the upper left panel we display basic indicators about US trade exposure: US trade volumes have increased while average applied tariff rates have fallen. The upper right panel plots shipping volume, measured in millions of twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), and total hours of paid longshore work (for all tiers of longshore workers). Both show impressive, sustained increases from 1995–2007 reflecting the expansion of US trade in the Pacific Rim region, especially with China. The financial crisis of 2008–2009 and ensuing recession induced a pronounced decline in trade and shipping volumes, but hours worked by West Coast longshore workers decreased even more sharply.

The bottom-left panel of Figure 1 provides one picture of the expansion of ILWU membership (and available work) over the past twenty-five years. The solid black line displays the number of active Class-A workers, that is, those working at least one hour in that year. This value remained essentially flat through the 1980s, declined in the early 1990s, and then expanded systematically from 1995 onward. The two lighter lines represent the number of Class-A individuals working full time or better (at least 2,000 hours/year) and those getting consistent overtime work (at least 2,800 hours/year). Both of these values show sustained increases; an expanded workforce and increasing hours complemented growth in trade.

The bottom-right panel of Figure 1 displays the average real earningsFootnote 6 for Class-A workers over time by the same hours-worked divisions we just described. These data indicate that compensation grew along with the size of the workforce, opportunities to work, and international trade. The union's strategic position in the US economy clearly enables it to maintain high wages, but the growing demand for the workers it represents underpins its position. The amount of annual pay ultimately depends on the number of hours worked, and those hours fluctuate with the volume of trade. This growth in real earnings is even more remarkable when we consider that median real wages for American blue-collar workers have been stagnant since the 1980s. By virtually any measure ILWU members have benefited from expanded US trade, especially with the countries of the Pacific Rim. It seems unlikely that ILWU members would expect future trade to harm them given the union's continued strength and long-term contracts with the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA).

It may be argued that the ILWU position on trade is the result of a political compromise within a union whose constituency includes more than dockworkers. The union, itself, recognizes this:

Because the ILWU's membership includes longshore workers who rely on international commerce for employment, sugar workers in Hawaii who need legislative protection from sugar imports, warehouse workers who handle both domestic and international products, and hotel workers whose livelihood rests on a growing global economy, the union has sought to develop a solution to the trade problem that answers all members' concerns.Footnote 7

Nevertheless, the union's Longshore Division remains the heart of the union; all ILWU presidents have come from Longshore. Our survey data look at only longshore workers, which means we cannot assess whether Hawaiian sugar workers are more antiliberalization than those in the Longshore Division.

The Longshore Division itself encompasses both dock labor and workers performing supervisory and clerical tasks, with these groups usually organized into separate locals. With clerical tasks already unbundled,Footnote 8 the clerks face the greatest immediate threat from outsourcing, whether to workers abroad or simply to nonunionized workers in parts of the United States.Footnote 9 Longshore workers still provide services that are nearly impossible to outsource. Although the clerks are a numerically small group,Footnote 10 their vulnerability is clearly part of the ILWU's concerns about technology. It may also spill over into the union's position on globalization, especially NAFTA, but the outsourcing threat is not necessarily about replacement by a worker in a foreign country. Our survey does not include the clerks' locals in Seattle and Southern California, so we cannot evaluate whether clerks are more opposed to globalization than longshore workers.

International Trade and Public Opinion

Since the Great Depression, policymakers and scholars have viewed public acquiescence to free trade policies, especially in the rich democracies, as important for maintaining a stable and growing world economy. Establishing the distribution of public opinion about trade policy and the extent to which individual attributes, cultural characteristics, and various public policies can affect voters' opinions on trade remains a vigorous and contested area of research.

Early work was based squarely in either the industry-based (Ricardo-Viner) or class-based (Stolper-Samuelson/Hecksher-Ohlin) models of trade. Empirical work consistently turns up evidence that more educated individuals tend to favor lower trade barriers, a finding frequently interpreted as consistent with the Stolper-Samuelson/Hecksher-Ohlin model.Footnote 11

Arguments about whether an individual's opinions over trade policy derive from how they earn their income (class-based) versus the industry in which they are employed have given way to more nuanced claims involving sociotropism,Footnote 12 preferences for fairness,Footnote 13 exposure to economic ideas during college education,Footnote 14 risk exposure,Footnote 15 individual risk tolerance,Footnote 16 and survey framing effects.Footnote 17 Directly germane to this article, there is no consistent evidence in this literature that unionization has any relationship with trade opinions one way or another.Footnote 18 Taken together, these papers suggest that, at minimum, trade policy preferences are not easily reducible to the expected income effects anticipated under the classical macroeconomic trade models. Our findings strengthen this conclusion.

A criticism that can be leveled at all these studies, however, is the reliance on the standard national-level survey instruments. While surveys can be powerful tools, it is not always clear what they are tapping with their questions, all the more so when asking respondents to conjure opinions on topics about which they may be ill-informed. When asking about trade protection, tariffs, and various international treaties, it stands to reason that many survey respondents have little knowledge of these issues. Examining the ANES question commonly used to measure American attitudes on trade,Footnote 19 we see that “haven't thought much about it” is the modal response.Footnote 20 Even if respondents are aware of trade issues, there is little evidence that voters consider them salient or important. For example, the Gallup “most important problem” question,Footnote 21 a widely used measure of issue salience, records a negligible number of respondents mentioning trade or the trade deficit as among the most important problems facing the United States in 2011, a period in which economic issues, broadly, were extraordinarily salient.

Then there is the truly enormous literature, going back over six decades in the United States,Footnote 22 looking at the “effect” of unionization on public opinion and voter behavior. American unions, in contrast to some of their European counterparts, are held to be particularly interesting organizations since workers become union members for reasons of employment; they do not sort into unions for political reasons. Relying on interviews and, occasionally, surveys in order to describe the political opinions and activities of union members, early union studies never constructed compelling, rigorous comparisons with nonunionists. Later studies relied on large-scale public opinion surveys to compare the political opinions and behavior of union members versus nonmembers.Footnote 23 Although these studies constructed better estimates of unionization's effect on voter turnout in the United States and other democracies, they had no information on which unions respondents belonged to or their level of exposure. After sixty years of research on American unions, we still lack convincing evidence of whether or how union membership affects political attitudes.

We contribute to both these literatures by focusing on a group of workers for whom international trade is, objectively, intensely salient; their earnings prospects are directly bound up with the volume of international trade, especially in the Pacific Rim. They are already employed and their likelihood of remaining so depends positively on shipping volumes. They tend to live near the docks in the cosmopolitan and outward-facing areas such as Los Angeles/Long Beach/San Pedro, Portland, Seattle/Tacoma, and San Francisco/Oakland.Footnote 24 The level of skill needed to work on the docks has also increased over the years, especially since the advent of containerization in the late 1960s and computerized dispatch and tracking in the 1990s and 2000s. The combination of these factors makes supporting liberalized trade consistent with the dockworkers' myopic economic interests. But almost all these workers are members of one of the most powerful, militant, and socially activist unions in the United States. The ILWU is renowned for its vibrant internal democracy, rank-and-file participation, and the easy recall of its leaders.Footnote 25 The ILWU has long maintained a broad social justice orientation in politics. We argue that the ILWU's stance on trade is consistent with its stated organizational principles and serves to build and enhance the reputational value of the union's organizational culture. Our survey evidence as well as the longevity and consistency of the union's position across leadership cohorts are consistent with the notion that the membership has bought in.

Possible Explanations

We consider two sets of competing explanations for the ILWU's puzzling stance on trade liberalization. The first is composed of arguments relying exclusively on workers' economic self-interest, looking at both simple myopic economic self-interests of longshore workers as well as expectations derived from standard theories of international trade. The second is a more sociological explanation relating stated organizational principles, governance, and member socialization.

Economistic and Trade Theory Explanations

More international trade, especially in the Pacific Rim, presents an immediate increase in the demand for the labor of West Coast dockworkers, clearly serving the workers' myopic economic interests. But more trade may have other distributional consequences. In deriving citizen preferences over trade policy the political economy literature generally relies on one of two foundational models, the Ricardo-Viner or the Stolper-Samuelson/Hecksher-Ohlin.Footnote 26 Both models examine the distribution of income across economic actors as international trade becomes less onerous, whether for technological or policy-related reasons. The primary difference between the two models is an assumption about the ease with which factors of production can be redeployed to different uses as economic opportunities change.Footnote 27 The Ricardo-Viner model assumes that capital (and possibly labor) is fixed in the respective industries or sectors, at least over the short term. The Stolper-Samuelson model assumes mobile factors.

In a Ricardo-Viner world, conflict over trade policy happens along industrial lines. Firms in industries that are forced to accommodate price-competitive imports will generally oppose trade liberalization whereas those who stand to gain through their ability to successfully export will support it. The shipping and distribution industries, such as stevedoring, longshoring, and warehousing, clearly benefit from more international trade.Footnote 28 If labor is assumed fixed in the sense that workers' skills or other attributes are not valued similarly in other industries then workers' interests over trade should be aligned with those of the employers in the industry. In the case of US dockworkers, union representation is an important industry-specific consideration, especially in an era of rapidly eroding private-sector unionization. And since longshore unions on both the East and West Coasts have succeeded in keeping wages relatively high, we argue that, from the perspective of Ricardo-Viner, we should consider labor to be a fixed factor in this situation.Footnote 29 We should then observe the following hypotheses:

H1: Both unions of dockworkers should adopt similar policies over international trade.

H2: Both unions of dockworkers as well as the stevedoring and shipping firms should take pro-trade positions on international trade policy.

At the micro level a Ricardo-Viner approach also predicts that the following hypothesis:

H3: Workers in the shipping/longshore industry should be more supportive of trade liberalization than a sample of workers taken from a variety of industries.

The key distributive implication of the Stolper-Samuelson/Hecksher-Ohlin trade model is that attitudes toward international trade and trade policy should be class-based. As trade between countries expands, production in each country specializes in products that most effectively use that country's relatively abundant factor of production, improving economic prospects for the owners of the relatively abundant factor but harming the owners of the relatively scarce one. In the United States labor is held to be relatively scarce whereas capital and land are relatively abundant. Labor, especially unskilled labor, is therefore expected to oppose trade liberalization. Stolper-Samuelson leads to the following hypotheses:

H4: Both unions of American dockworkers should adopt similar, anti-trade policies.

H5: Dockworkers' unions and stevedoring and shipping firms should take opposing positions on trade policy.

At the micro level, assuming education is a reasonable proxy for skills, Stolper-Samuelson also predicts the following:

H6: The support for trade liberalization among workers in the shipping/longshore industry should be no different than a sample of workers taken from a variety of industries, conditional on education level.

The dominant trade theories share one empirical implication in common, namely that unions organizing similar groups of workers in the same country should take similar policy positions over trade. But the two models make differing predictions about what those positions will be. We also note that it is unclear what the appropriate skill categorization for longshore workers should be. On the one hand longshore work has become more capital-intensive and requires greater skill than in the past. On the other, incoming longshore workers are not required to have any particular level of skill training; virtually all training on the West Coast docks happens on the job or through the union and employer-run programs. Many of these skills are not portable to other industrial settings.

Sociological Mechanisms

The second possible kind of explanation is that the ILWU's behavior is partly a function of its organizational principles. Formal organizations exist because they solve informational and distributional problems associated with collective action under changing conditions.Footnote 30 It is impossible to write organizational constitutions specifying how an organization (or its leaders) will act in all possible states of the world.Footnote 31 All organizations, therefore, rely on a combination of governance rules, stated principles, and norms to enable members and leaders to form expectations about how the organization will behave over time.Footnote 32 As leaders repeatedly make observable decisions and take positions consistent with stated principles, the organization develops a cultural reputation. Both Kreps and Miller emphasize that principled actions or positions apparently contrary to immediate economic interests are particularly important for building and sustaining an organizational culture—so long as organizational performance continues to be strong.

As new members join the union, they will likely view the organization's culture as so many norms of behavior. Initially, we expect that some combination of sanctions and expectations about others will promote compliance. Over time, however, there is the possibility that the members may come to reconsider their beliefs and preferences as a result of their organizational exposure and socialization. In keeping with the “active decision” hypothesis of Stutzer, Goette, and Zehnder,Footnote 33 they may begin to develop new normative motivations as the basis for their compliance. In the ILWU context, members who are asked to form an opinion about issues they had not previously considered—or at least had not considered relevant to their union—can be induced to reconsider their beliefs and preferences in light of the union's performance.Footnote 34

Since its 1937 founding, the ILWU has maintained a vigorous and explicit set of “Ten Guiding Principles.” The most relevant to trade are the following two:

Principle No. 4: “To help any worker in distress” must be a daily guide in the life of every trade union and its individual members.

Principle No. 8: The basic aspirations and desires of the workers throughout the world are the same.Footnote 35

Principle No. 8 is particularly noteworthy in the context of trade because it represents an explicit invocation of class interest in justifying the union's actions and objectives. It is not that the ILWU is eschewing appeals to the members' economic interests. Rather the union is asking them to take a broader, longer-term view in which the members' interests are bound up with the outcomes for other workers, both domestically and abroad.

If the union's trade position is an extension of its organizationally specific “culture” then we should observe the following hypothesis:

H7: Unions in the same industry taking different positions on international trade manifest distinct organizational cultures, especially if the position taken is contrary to immediate economic interests.

Union leaders should justify and explain their position with reference to organizational principles, and we should be able to identify mechanisms and processes of “socialization.” At the micro level, if union socialization induces members to crystallize their preferences as a result of organizational exposure then we should also observe the following:

H8: Union members whose union asks them to form opinions about trade policy should be more likely to report having an opinion on trade.

H9: Workers with more extensive exposure to the union should be more likely to have an opinion on trade policy and more likely to report opinions consistent with the union's position so long as union membership continues to be valuable.

In other words, the organizational culture/preference provocation argument provides a way to accommodate both expressed preferences contrary to immediate economic interest and as well as heterogeneity in behavior across organizations representing the same class of workers in the same economy.

Note that preference provocation does not imply that the members necessarily come to agree with the organization's position. Asking members to formulate opinions can have the effect of revealing heterogeneity within the membership. But, to the extent that the union's principles have coincided with strong union performance in terms of improved wages and working conditions, workers are likely to find the organization's principles more compelling over time. Table 1 collects the hypotheses for ease of reference.

TABLE 1. Hypotheses collected

Other Possible Explanations

There are other possible explanations. First, there may be a postmaterialist effect: the union is successful in raising wages and protecting members and this affords members the luxury of taking principled stands that may be inconsistent with their material interests. Workers with less seniority—the most likely to be forced out of the industry and into a less lucrative position should shipping volumes drop off—will be more supportive of trade liberalization.Footnote 36 While the ILWU's industrial success likely provides it with the resources to take political positions, this explanation is insufficient in three ways. First, it is not obvious that having the luxury of taking principled stances implies that the union would mobilize around trade issues. Nor is it obvious why the union should oppose trade liberalization. Third, senior ILA members (and those of other unions) are also more protected yet they do not behave as the ILWU does. In other words, the postmaterialist “explanation” is really just a renaming of the puzzle.

Conflict over new technology has been a hallmark of waterfront industrial relations for decades. It is therefore possible that the ILWU is rationally fearful that increased trade will interact with exogenous technological change in ways that lead to a substitution of capital for labor. Globalization might then represent a double-edged sword; this certainly appears to be the case for marine clerks, as discussed earlier. But even if such a threat exists, it does not follow that the unions should resist policies that would increase demand for port labor. In any event, since the 1990s increased trade has coincided with both the introduction of labor-saving technologies and an increase in the port labor force and compensation (see Figure 1). Further, the ILWU has a long history of accommodating the introduction of new technology so long as redundant workers are compensated and any new jobs created by the technology remain ILWU-represented positions. None of the union leaders or members we interviewed linked the union's stance on trade with issues of technology or the outsourcing of longshore jobs. Finally, if technology is a concern, then the dockworkers all over the United States face a similar threat, yet, as we discuss, only the ILWU has mobilized against trade liberalization.

Another possible explanation is that members are simply responding to the discourse of salient elites with whom they already agree on some issues.Footnote 37 We believe that this is not the case for the ILWU, or at least not exclusively so, for three reasons. First, given the ILWU's clear benefits from trade, it is not obvious why the elites themselves would ever hold antiliberalization positions for a sustained period of time in the absence of organizational principles. Second, ILWU leaders are subject to extensive democratic and procedural controls, including tying their salaries to the wages of the rank and file. Union leaders are defeated in elections and routinely return to the docks as rank-and-file workers.Footnote 38 These elites are elected by the membership, yet they espouse positions that can be construed as contrary to the members' economic interests, an electorally vulnerable position. Third, if elite opinion were all that mattered then we would expect the union position to vary as leadership cohorts change. The ILWU has seen five union presidents since 1977 yet trade policy has remained broadly consistent since the early 1980s.

Evaluating the Hypotheses

The previous section outlined major explanations for our puzzle and derived observable implications. Here we evaluate the elite- and organization-level hypotheses (H1, H2, H4, H5, H7) by looking at historical data for the ILWU and ILA. We then evaluate the micro-level hypotheses (H3, H6, H8, H9) using evidence from a survey of ILWU members and nonmembers.

ILWU Trade Policy

Historically, ILWU leaders possessed strong normative and political commitments. They proved willing, if necessary, to arouse membership resistance and government punishments, including jail time. Harry Bridges, an Australian national and founding union president, angered some ILWU members by opposing the Korean War, but most rallied to his defense when he was sent to jail for speaking out and supported him during the many trials and threats of deportation as he tried to win American citizenship and disprove prosecutorial claims of Communist Party membership.

In the early years of the union the ILWU supported low trade barriers, but the rationale expressed by union leaders was not one of classical comparative advantage nor was it one of ILWU self-interest. Rather the ILWU's trade stance reflected the leadership's express commitment to broad labor solidarity and support for the communist and socialist regimes in Asia and Eastern Europe.

During his forty-year term as president, Bridges often spoke of trade as a way to increase cultural contact with other nations, particularly with the Soviet Union, China, and Eastern Europe. Between 1955 and 1973, the union passed several resolutions to this effect.Footnote 39 In his column “On the Beam” in the ILWU's official newspaper, The Dispatcher, Bridges occasionally commented on this issue. In 1965, in opposition to the AFL-CIO's position opposing increased trade with China, Bridges wrote:

Any student of history knows that expansion of world trade has always strengthened the cause of peace. It may be true that many wars have broken out in the past over a division of world markets, but even in these cases the aims were to increase trade for one country over another. No reasonable nation ever assumed its capacity to grow and prosper without trade.Footnote 40

Bridges's position is clearly informed by his procommunist political stance. Gene Vrana, former ILWU librarian and director of education, notes: “Bridges supported these policies due to his political convictions and it was easy for the rank and file to get behind him out of self-interest.”Footnote 41

In a 1968 statement before the US House of Representatives' Committee on Ways and Means, the ILWU Washington representative summarized the union's position, noting:

The ILWU supports free trade and urges the opening of markets in Eastern Europe and China as a means of improving our trade balance and helping world peace… Recognizing the frustrating problems in working out agreements, we believe that negotiations, such as those being conducted through GATT, are the answer.Footnote 42

The ILWU's policy shift to an antiliberalization stance did not parallel that in the larger US labor movement. The AFL-CIO opposed the Trade Act of 1969, which the ILWU, in congressional testimony, advocated as “a modest, but vital, step in the direction of freer, expanding trade.”Footnote 43 The ILWU supported and the AFL-CIO, opposed the Trade Act of 1974, which established fast track trade negotiating authority for the US president. However, the ILWU did share the AFL-CIO position on curbing incentives for overseas investments by multinational corporations.

The ILWU's opposition to trade liberalization emerged in the early 1980s probably in response to the increasing prospect of capital mobility and the resulting offshoring of American manufacturing. Its 1988 statement of policy states that

tariffs and quotas are among the least significant factors in international trade. The underlying causes of the [trade imbalance] crisis have yet to receive the public attention they deserve, and tinkering with formal import restrictions by itself will do nothing to resolve this problem. About 30 percent of the trade imbalance has resulted from the US corporations moving their operations to other countries, manufacturing products there, and importing them to the US.Footnote 44

Around this time the union formally voiced its concern to Congress on a number of trade issues. For example, the union wrote to the Senate Finance Committee in 1987 expressing support for a bill that would define denial of workers' rights as an unfair trade practice. The letter states,

For the ILWU the current trade imbalance only confirms what we have long known: that American workers' own well being is inseparably bound up with the progress of our fellow workers abroad. But self-interest is not our only motivation. Just as we reject the callous assumption by some that economic recovery in the United States will require the steady erosion of domestic labor costs … we reject the common assumption that labor rights must be trampled on as they are in many countries for the sake of what is euphemistically called “initial capital formation.”Footnote 45

We note that even in this letter the ILWU's conception of self-interest seems to encompass all American workers, not simply ILWU members.

The debate on NAFTA stimulated further opposition to trade liberalization. In April 1991, the ILWU's International Executive Board raised concerns about “the maquiladora pattern”Footnote 46 in which trade agreements would give companies an unfettered access to easily exploitable populations of workers and resources and then export those products back to the United States, driving down American living standards while failing to protect Mexican workers. In the same month, ILWU President Dave Arian made a speech to the union's Coast Committee, referencing government abuses of the Stevedores Union in Veracruz, Mexico, and linking free trade to the attenuated power of organized labor in liberalizing economies.

In the run-up to NAFTA ratification the ILWU leadership issued several statements opposing the agreement and launched a campaign to convince its members of the deleterious effects of free trade on both American and foreign workers' rights. The “No on NAFTA” petition involved a union-wide effort to secure 10,000 signatures to send to American, Canadian, and Mexican government officials.

Joe Wenzl, a former member of the ILWU's longshore executive committee states, “The vast majority of the ILWU opposes NAFTA and CAFTA. You'll be hard pressed to find a dissenting opinion. NAFTA has become a dirty word to the average longshoremen, same as ‘employer.’”Footnote 47 Vrana confirms, “You won't be able to find any officer who is going to sidetrack this issue. We have a consistent policy of twenty years by the union against free trade and an even longer history of being in favor of worker solidarity internationally.”Footnote 48 Concerns about labor injustices associated with freer trade generally emerged after Bridges's time, but Wenzl states, “The union's position [on trade] is right in line with Bridges's type of thinking. It flows directly from our Ten Guiding Principles.”Footnote 49

The union has never espoused overt protectionism, but it does seek international trade arrangements that codify worker rights. In a speech opposing NAFTA, Arian emphasized, “I would like to point out that our Union has always supported free and fair trade, but the agreement that is being negotiated is neither free nor fair.”Footnote 50

Since about 90 percent (by value) of Canada-Mexico-US trade is over land, the vociferous union position on NAFTA may reflect a perceived threat to maritime work. ILWU members and officials may have feared that as manufacturing expanded in the maquiladora zone, US maritime traffic would be diverted to land routes and Mexican ports.Footnote 51 However, at the time of NAFTA ratification these were not immediate concerns, nor did the union raise diversion of marine traffic in its arguments against the treaty. Even today Mexican infrastructure is still far from presenting viable competition to US ports, although there is a proposal to build a large container terminal in Baja California. At ratification Los Angeles Harbor officials were projecting NAFTA-induced traffic increases.Footnote 52 Indeed, there is little evidence of a net diversion to land-based modes. For example, in 2000 maritime shipping accounted for only 5 percent of US-NAFTA partner trade by value, but more than 32 percent by volume.Footnote 53 Between 1994 and 2001, the percent (by value) of US-NAFTA partner trade going over land actually declined slightly from 91 percent to 89 percent while the percent (by value) of NAFTA-partner maritime shipping increased from 5 percent to 7 percent between 2000 and 2004.Footnote 54

Another basis for opposition, expressed by the Southern California ILWU locals, was the realistic fear that NAFTA would precipitate outsourcing of clerical jobs to Mexico.Footnote 55 The 2012 LA/Long Beach clerks strike cited the continuing threat of job outsourcing to Mexico—and Arizona and Texas. The continued relevance of this threat is a possible reason why NAFTA remains salient to ILWU members fifteen years after its ratification. Nevertheless, the vast majority of longshore workers are not vulnerable to outsourcing. The union's position underscores organizational commitments to its version of worker solidarity, both within and outside the union.

The WTO again raised the issue of US trade policy. In August 1999, in a Statement of Policy on the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Executive Board detailed ILWU plans to demonstrate against the WTO meeting in Seattle. The union stopped work along the West Coast for eight hours on 30 November 1999, the first day of the WTO ministerial. During a speech to protesters, ILWU President Brian McWilliams stated the union's position:Footnote 56

And let us be clear. Let's not allow the free traders to paint us as isolationist anti-traders. We are for trade. Don't ever forget—it is the labor of working people that produces all the wealth. When we say we demand fair trade policies we mean we demand a world in which trade brings dignity and fair treatment to all workers, with its benefits shared fairly and equally, a world in which the interconnectedness of trade promotes peace and encourages healthy and environmentally sound and sustainable development, a world which promotes economic justice and social justice and environmental sanity. The free traders promote economic injustice, social injustice and environmental insanity.Footnote 57

More recently, in December 2010 ILWU President Robert McEllrath sent a letter to Nancy Pelosi, who at that time was Speaker of the House of Representatives, expressing ILWU opposition to the South Korean Trade agreement:

By all accounts, the Korea-United States Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA) will increase trade between South Korea and the United States, which will result in an increase in cargo movement between the two countries. An increase in cargo movement is good for dockworkers. However, this fact alone is insufficient to overcome the vast deficiencies of the KORUS FTA.

The KORUS FTA will cost jobs, lower environmental, labor, food and product quality standards, and empower corporations from the United States and South Korea to challenge public interests in both countries. The labor standards provision of the agreement only provides that each country enforce its own laws to adhere to the core labor standards identified by the International Labor Organization. The United States and South Korea's laws and enforcement in this area are completely inadequate and must be amended prior to the implementation of the agreement.Footnote 58

Although official statements and resolutions put forward by the ILWU international officers largely express these issues in terms of global worker solidarity, local opposition can take a form more protectionist of the American worker. Scott Mason, current president of Local 23 in Tacoma, elaborates his position:

If imports rise faster than exports, Americans workers lose. A net balance that results in a trade deficit affects the whole country. We ship a lot of empty containers and longshore workers are not okay with this. We benefit from both imports and exports and we even benefit from shipping empties, but we're only happy when the balance helps the American worker. We realize that shipping away all of our jobs is not smart in the long run. In Tacoma at the local level, we support Obama's mission to double exports, but not by shipping out empty containers. Of course we are not against all forms of trade, but only when the net effect means we're losing more than gaining.Footnote 59

In interviews with several former and current ILWU leaders, not one reported a change in the position of the union leadership or the rank and file with the collapse of trade in recent years. Rather, there is evidence of confirmation of the union's stance in the conventions and international executive board meetings since the onset of the financial crisis. The 2012 ILWU convention passed a resolution opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, mobilizing members to protest at the July 2012 negotiating round in San Diego.Footnote 60

Discussion

ILWU leaders clearly believe that trade issues are relevant to the union's mission. Consistent with the Kreps-Miller notion of organizational culture, the ILWU leadership regularly invokes the declared principles of the union to justify and explain its stance. Interestingly, these positions, especially since the 1980s, seem to conflict with the myopic economic interests of the members and, perhaps, the leaders as well.

The ILWU's position is clearly contrary to what we anticipate in Ricardo-Viner's world, or, more simply, one in which workers support policies likely to increase demand for their services. A Ricardo-Viner explanation becomes even less tenable given that the ILWU and their employers' were diametrically opposed on NAFTA.Footnote 61 The American Association of Port Authorities (AAPA), the port operators' industry association, repeatedly filed public testimony with both the US Trade Representative (USTR) and Senate Finance Committee strongly supporting the FTAs with Korea, Panama, and Colombia.Footnote 62 Hanjin Shipping, a Korean conglomerate and PMA member with a large trans-Pacific container shipping business, filed a separate comment with the USTR in support of the KORUS FTA. APL, another major trans-Pacific shipper and PMA member, was signatory to the US Chamber of Commerce's US-Korea FTA Business Coalition pro-KORUS public letter to the US Congress.Footnote 63 We found no evidence of any shipping or stevedoring company opposing any recent US trade agreement.

Nor is the evidence consistent with the Stolper-Samuelson logic. The ILWU's shift in trade policy came much later than the AFL-CIO's and well before it became technologically feasible to outsource clerical work. The union has generally not supported increased tariffs or quotas. Its opposition to FTAs has been focused on their catalytic effect on the offshoring of domestic production, often to countries with weak labor protections.

Comparing East Coast (ILA) and West Coast dockworkers' unions provides important evidence against the key predictions derived from myopic economic self-interest, standard trade theory, or even the threat of outsourcing.Footnote 64 Extensive searches in the secondary literature, primary source archives, and the public record turned up no record of the ILA ever taking formal positions on trade policy one way or another.Footnote 65 It certainly was not advocating “fair trade” positions in the Congressional Record, mobilizing its members in opposition to NAFTA, or calling work stoppages to protest the WTO. Whether preferences are industrially derived or class-based we would expect both unions to take similar positions in roughly equal intensity; they do not.Footnote 66

The ILWU's position on trade appears organizationally specific among unions representing American dockworkers. When we consider that the ILA has a documented history of a very different organizational culture, including a tradition of corruption, racketeering, and conservative politics,Footnote 67 the difference in union stances on trade is consistent with H7.

Dockworkers' Attitudes Toward Trade

We contend that members' policy preferences, at least at the margin, are affected by the decisions and information that ILWU membership implies. The mechanisms through which this socialization might take place are several. The union is known for its open, democratic, and highly participatory governance. Members are frequently asked to express their opinions on the union's policies and, once a decision is made, the members are asked to take action. The union members also interact frequently and repeatedly, both on the job and in residential communities. They meet almost daily at the union-controlled hiring hall to pick up shifts, and work itself occurs in “gangs.” Union members are also regularly exposed to union positions and officers at regular meetings, through union-managed training and education programs, and by way of the union newspaper and Internet sites. Extended exposure to a strong organizational culture that repeatedly demands active decisions of the members implies crystallization and, possibly, shifts in members' opinions on the relevant topics.

Research design and matching

We measure dockworkers' attitudes toward trade using an individual-level survey of ILWU members and registered Casuals (both groups subsequently referred to collectively as affiliates) in the longshore locals of Seattle, Tacoma, and Los Angeles/Long Beach.Footnote 68 The survey was conducted from 2006 to 2011. Surveys were administered in a variety of formats. Early surveys were administered over the phone. After some in the union objected to phone surveys, subsequent survey administration occurred on site at the union hall during meetings using pencil-and-paper survey instruments. As a final method, we also conducted a web-based survey for members in the Los Angeles/Long Beach local. Members were encouraged to participate via a raffle of local college football tickets. Over the same period we generated a sample of nonunion members by administering a nearly identical survey using random digit dialing (RDD) into the area codes with geographic coverage containing the most common union member residences areas in each local. In total, we surveyed 675 ILWU affiliates and 604 nonaffiliates.

Some internal union opposition and the dramatic effect of the global economic crisis on dock work availability stymied our efforts to generate either a longitudinal or simple random sample of the union affiliate population.Footnote 69 Our respondents largely selected in to our study, leading us to rely heavily on ex post matching techniques to construct defensible comparisons of ILWU affiliates with nonaffiliates.

Since ILWU membership cannot be considered randomly assigned we follow the strategy proposed in Ho and colleaguesFootnote 70 and use a matching step to “preprocess” our data, selecting a subset of ILWU and RDD respondents that is as balanced as possible on observable “pretreatment” covariates. By discarding observations that do not fit in the range of a balanced distribution of covariates we eliminate approximately 28 percent of our observations but achieve ILWU and non-ILWU groups that are closely balanced on observables.

By matching prior to implementing standard parametric models we reduce the model dependence of our estimated average “treatement effect” of ILWU membership on trade attitudes. We put the “treatment effect” in quotation marks for two reasons. First, we do not observe the “pretreatment” attitudes of ILWU members. Second, as with any matching procedure, we cannot unambiguously rule out the possibility that workers select in to the ILWU for unmeasured reasons that may be correlated with their political attitudes (but see previous section). That said, we are confident that survey respondents (and ILWU members more generally) are not self-selecting in to the ILWU for political reasons, nor are they exiting the union when the union takes political stands with which they might disagree.

In some sense the ideal “control” group would be West Coast dockworkers who are not members of the ILWU. However, there are none; virtually every West Coast dockworker is somehow affiliated with the ILWU. Similarly we might like to use a survey to compare those ultimately chosen to work on the docks with those not selected. Gaining access to ILWU affiliates was quite difficult; gaining access to those not selected to work on the docks proved impossible. A parallel survey with ILWU and ILA affiliates also proved impossible to implement. The RDD strategy combined with matching is the best feasible design, allowing us to construct a defensible set of comparisons even if we are unable to claim to have perfectly estimated the “causal effect” of ILWU membership in this case. That said, our baseline expectation is that dockworkers should be more pro-trade than otherwise similar individuals.

One-to-one exact matching was not feasible with these data. Instead we use genetic matching, as described in Abadie and ImbensFootnote 71 and Diamond and Sekhon.Footnote 72 We allowed up to two RDD observations to be assigned to each ILWU observation. We discard observations for which there is no effective match in both the ILWU affiliate and RDD groups. Pretreament matching covariates are the age, sex, ethnicity, education level, location, and the date the survey was conducted. To avoid problems with posttreatment bias we do not match on the respondents' political party identification or income category because these are arguably effects of increased ILWU tenure.Footnote 73 Similarly we do not include covariates for the mode of survey administration (paper/pencil, phone, web) in either the matching or parametric model since the RDD sample was surveyed exclusively by phone. Balance diagnostics are reported in the appendix.

Although the rate of missingness is low (between 0 and 10 percent for most of our covariates), we impute missing values rather than list-wise delete entire observations. We use Amelia II for R to perform the multiple imputations.Footnote 74

If we perform the matching exercise seperately on each imputed data set, we end up with slightly different sets of matched observations with different weightings. Since the underlying sets of observations then differ, we cannot use the standard algorithm for combining parameter estimates and uncertainty for models fit across imputed and preprocessed data sets. We therefore average across the twenty imputed data sets to generate a single complete data set. We match using the complete data and then fit our parametric models to this single matched data set. This approach does deal with missing data in a principled fashion, but our imputation uncertainty does not propagate through the full estimation process. As a check, we also matched independently on each of five randomly selected imputed data sets and then conducted the analysis. We also simply fit the models using only complete cases; our substantive conclusions remain unchanged under both alternative procedures.

In evaluating the membership's attitudes toward trade we focus on two survey questions: one asking the respondent to declare whether they favor increased restrictions on imports and a second asking their level of approval for NAFTA. We note that the import restrictions question is relatively vague; the ILWU has never favored generic import restrictions. Rather the union has consistently opposed further trade liberalization via specific FTAs as well as the WTO. We expect findings to be stronger for the NAFTA question than for the tariffs question. We measure an individual's union exposure with a series of interaction terms identifying the respondent's seniority rank.

Attitudes on US trade barriers

The first relevant survey question asks respondents their opinion on the US government limiting imports. Our survey uses the same wording as the ANES question commonly used in other studies. The question reads: “Some people have suggested placing new limits on foreign imports in order to protect American jobs. Others say that such limits would raise consumer prices and hurt American exports. Do you favor or oppose placing new limits on imports, or haven't you thought much about this?”

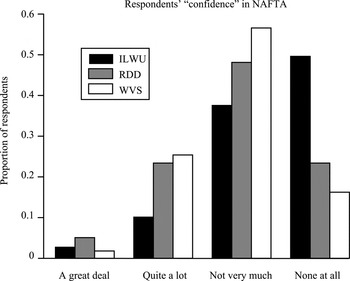

The respondents were allowed to answer “Favor,” “Oppose,” or “Haven't thought much about it.”Footnote 75 Figure 2 displays the frequency distribution of ILWU and RDD responses to this question for both the raw data and the matched set of observations. As a point of comparison we include the ANES 2004 responses as well.

FIGURE 2. Distribution of responses to whether the US government should place new limits on imports

Figure 2 reveals that in the raw data a similar number of ILWU and RDD respondents report holding an overall opinion on this issue in either direction (67 percent and 64 percent respectively). However, conditional on having an opinion, 53 percent of ILWU respondents said they favored new restrictions on imports, whereas 47 percent of RDD respondents chose this category. In the matched data, of those that reported an opinion (approximately 68 percent RDD respondents and 70 percent of ILWU respondents), 43 percent of RDD and 54 percent of ILWU respondents reported favoring increased restrictions (a difference of 11 percentage points as opposed to 6 points in the unmatched data). All groups in our survey are more likely to have an opinion on trade restrictions and to be more likely to oppose trade restrictions than the ANES 2004 sample, though the difference in time and regional specificity of our survey make this comparison less illuminating.

We take the three possible response categories, “Favor,” “Oppose,” and “Haven't thought much about it” to construct the dependent variable for our multinomial logistic regressions. Table 2 displays regression results.

TABLE 2. Weighted multinomial logit on support for import restrictions, matched data

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients that achieve p ≤ 0.05 are indicated in bold. Reference category for geographic area is Los Angeles/Long Beach. Reference category for race includes Asian Americans, African Americans, Pacific Islanders, and those who self-identified as “other.”

Our results indicate that ILWU affiliates are distinguishable from otherwise similar workers, contrary to H6. Consistent with H9, those with the greatest union exposure, Class-A members, are significantly more likely to favor increased restrictions on imports compared to not having an opinion; there is no evidence of a similar effect for less senior affiliates. Holding covariate values at sample means/modes, a Class-A ILWU respondent is 32 percent more likely to favor import restrictions than an RDD respondent. Class-B respondents are significantly less likely to favor import restrictions, perhaps reflecting an increased sensitivity to work opportunities on the docks.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies: women are less likely to express an opinion and are marginally more likely to support restrictions on imports. More-educated respondents are more likely to oppose restrictions on imports. Nevertheless, conditioning on education we still uncover a union seniority effect. We see modest regional variation in trade opinions along the West Coast, with those in the Pacific Northwest less likely to favor import restrictions compared to Southern California.

The presence of interaction terms makes interpretation of results somewhat complicated. To that end Figure 3 presents a ternary plot displaying each respondent's predicted probability for each possible response. Light triangles represent ILWU respondents while dark circles depict RDD respondents. The predicted probabilities for RDD respondents cluster away from favoring import restrictions. ILWU affiliates appear more likely to report favoring increased trade barriers, though there is considerable overlap between the groups in this figure.

FIGURE 3. Interpreting multinomial logit, by union affiliation

This overlap become easier to understand, however, when we consider ILWU affiliates by seniority. Figure 4 highlights the union tenure effect by comparing the predicted response probabilities of Class-A members (solid triangles), Class-B members (crosses), and Casuals as (open circles). Consistent with H8 and H9, Class-A members are clearly separated from both other groups: they are more likely to have opinions and more likely to favor new restrictions on imports than either the Class-B or Casuals. The overlap between the RDD and ILWU affiliate responses in Figure 3 comes from the more junior ILWU affiliates.

FIGURE 4. Interpreting multinomial logit, by union seniority

Since union seniority and age are correlated it may be that we are simply picking up an age cohort effect (even though we condition on age in the model). To test for this we conducted a separate matching exercise in which we matched ILWU union members (Class-A and Class-B) on age and then examined the differences between them. The frequency distribution is reported in the left-hand panel in Figure 5. Even among those of similar age, union exposure affects attitudes toward import restrictions. We also matched Class-A and Class-B respondents on the number of years they report being a registered member of the union (highly correlated with age) and report the distribution frequencies in the right-hand panel of Figure 5. Class-B members who have been in the union as long as Class-A members but have not logged enough hours of work to achieve A-status are less likely to have an opinion on imports as well as less likely to favor increased restrictions.

FIGURE 5. Distribution of responses to whether the US government should place new limits on imports, union member subsets

One plausible alternate interpretation of our findings involves the relative risks of having to find other work. ILWU affiliates are insecure in their employment status, particularly as trade volumes in the ports collapsed in 2008–2009. Their stance reflects their fear that they may be forced to look for work elsewhere in the economy where their earnings prospects might be harmed by trade openness. In our survey we ask respondents whether they are “very,” “somewhat,” or “not worried” about losing their port-related job.Footnote 76, Footnote 77 There is some evidence that those more worried about their port job were more protectionist: 46 percent of those “very worried” favored import restrictions while 33 percent of those who were “not worried” favored restrictions. Looking by union rank, however, we see a different picture. Casuals, whose job status is, by definition, more precarious were almost twice as likely as Class-A to report being “very worried” (26 percent against 14 percent). Of those claiming to be “very worried,” 57 percent (24/42) of Class-A affiliates favored import restrictions against 43 percent of Casuals (19/44). Of those claiming to be “not worried,” 44 percent (47/108) of the Class-A affiliates favored import restrictions against only 25 percent (13/54) of the Casuals. Regardless of the extent to which ILWU affiliates feared losing their port-related jobs, those with greater union tenure were more antiliberalization than newer recruits.

In sum, Class-A members are more likely than Casuals to have thought about whether the US government should place new limits on foreign imports. They are more likely to have an opinion on this issue in either direction but tend to significantly favor increasing import restrictions. Similarly situated respondents in the broader population are less protectionist than their ILWU Class-A counterparts. This pattern is consistent with the notion that organizational participation can dynamically affect individual political preferences.

Attitudes toward NAFTA

The second trade-related question asks respondents their opinion on NAFTA. This question is particularly important for our study since ILWU leadership took a specific position on NAFTA, as opposed to making vague pronouncements about trade or tariffs in general. We would therefore expect member opinions on NAFTA to differ from the broader population more dramatically compared to findings for the import restrictions question just analyzed. The survey question reads: “I am going to name a number of organizations. For each one, could you tell me how much confidence you have in them: Is it a great deal of confidence, quite a lot of confidence, not very much confidence or none at all?—NAFTA.”

Unfortunately, the wording on this question, taken from the US version of the World Values Survey, is vague. Leaving aside the fact that NAFTA is not an organization, the respondent may be unclear whether the question asks him/her to state their level of confidence in whether NAFTA signatories will uphold the treaty or whether they are confident that NAFTA is good policy. Based on conversations with unionists we believe the most common interpretation of the question is the latter. In any event, we have no reason to believe that ILWU affiliates would be systematically more or less confused by the question wording than RDD respondents.

The response distribution based on raw data displayed in Figure 6 makes clear that ILWU affiliates are much more likely than RDD respondents to have “no confidence at all” in NAFTA. The 2006 WVS response distribution (n = 1117) is included here for comparison. The WVS distribution is similar to the RDD sample, increasing our confidence that the RDD sample is providing a reasonable approximation to the broader population in this case. The evidence from Figure 6 is inconsistent with H6: ILWU affiliates differ starkly from the RDD sample in their reported opinions on NAFTA.

FIGURE 6. Distribution of respondents' level of confidence in NAFTA for RDD, ILWU, and 2006 World Values Survey

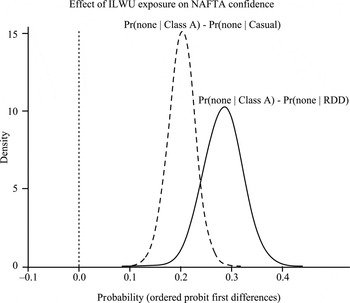

We use the four possible survey responses to construct an ordered dependent variable with larger values representing less confidence in NAFTA. Table 3 displays results from our ordered probit models fit to the matched data.

TABLE 3. Weighted ordered probit on level of support for NAFTA, matched data

Notes: Higher values on the response represent less support for NAFTA. Standard errors are in parentheses. Coefficients that achieve p ≤ 0.05 are indicated in bold. Reference category for geographic area is Los Angeles/Long Beach. Reference category for race includes Asian-Americans, African-Americans, Pacific Islanders, and those who self-identified as “other.”

The coefficient estimates imply that all ILWU affiliates are significantly less likely to express confidence in NAFTA than an RDD respondent. The more seniority, the more marked and significant increase in anti-NAFTA sentiment. To visualize the scale and uncertainty around this implication, Figure 7 plots the difference in the predicted probabilities of having “no confidence at all” in NAFTA for an ILWU Class-A member versus a nonaffiliate (solid curve) and for a Class-A member versus a Casual (broken curve). All other covariates are held at their appropriate central tendencies. The simulation describes the difference between respondents who are both forty-six-year-old white males from Long Beach with college degrees, taking the survey on 7 August 2009. The densities reflect our uncertainty in these differences. As an odds-ratio, the Class-A member is 74 percent more likely than an RDD respondent and 53 percent more likely than a Casual to express no confidence at all in NAFTA.

FIGURE 7. Difference in the predicted probability of having no confidence in NAFTA, comparing Class-A/RDD and Class-A/Casual

Robustness considerations

Our data can partially address two important remaining questions. First, are there unobserved confounders that might be generating our results? Second, have we identified an “ILWU effect” or simply a “union effect?” We describe the results from additional analysis to give some insight here.

To address the first issue, we use the following question from our survey: “Thinking about your family (mom, dad, uncles, aunts, and grandparents), have any members of your family been a member of a labor union?” Out of 557 RDD respondents who answered this question, 58 percent of respondents report having a family member in a union. This question partially addresses the possibility that people who come from union families may be both more likely to become ILWU members and to have systematically different political opinions and behaviors. The question has an obvious drawback that prevented us from including it in the initial analysis: we have no way of knowing whether the respondent's family member(s) joined unions before or after the respondent joined the ILWU. That is, we do not know if this is a “pretreatment” covariate. We also do not know if the respondent was raised in a union family as opposed to simply having relatives in unions (or both). Nevertheless, we repeated the analysis but included this variable in both the matching preprocessing model and the analysis of the matched data.

Results for the import restrictions and NAFTA questions are available in the Web archive. Results for the imports restriction question are nearly identical to those reported in Table 2. Importantly, the “union family member” variable is not a significant predictor of attitudes to import restrictions in the new model. Turning to the NAFTA question, the patterns of sign and significance described in Table 3 remain after matching and conditioning on the “union family member” variable. In this instance those coming from a union family are significantly less likely to express confidence in NAFTA.

To address the “union effect” issue we take advantage of the following question from our survey: “Have you ever been a member of a labor union?” Out of 600 RDD respondents who answered this question, 46 percent report having ever been a member of a union. We cannot match on this variable since all ILWU members will obviously answer “yes.” We therefore subset only the RDD respondents from the matched data that report having belonged to a union and then redo the parametric analysis. Detailed results are available online, but under this specification, the “ILWU effect” remains for both the “import restrictions” and NAFTA questions. We find this striking, in part because non-ILWU union members are likely to find increased trade more threatening to their job security than the ILWU.

Discussion

Our survey findings are largely consistent with the sociological model and inconsistent with the myopic self-interest or trade-theory derived predictions. First, ILWU members with the greatest union exposure are significantly more likely to report strong opinions about abstract trade policy issues than otherwise similar nonmembers. Second, ILWU members appear somewhat more skeptical of trade liberalization compared to matched individuals drawn from nearby communities. Third, ILWU members are significantly more skeptical of NAFTA than either the broader American population or matched nonmembers who live in nearby communities. This discrepancy between the ILWU members' responses to the generic trade restriction question and the NAFTA question closely parallels the ILWU's stated goals and objectives: ILWU leaders have consistently opposed specific free trade treaties while maintaining rhetorical commitment to “fair trade” and expanded work opportunities for the membership. Union members are correspondingly more likely to oppose the only specific treaty we asked about, NAFTA, while having less crystallized opinions about “new limits on foreign imports.”

Also consistent with our argument about the impact of organizational participation over time, Class-A members are more likely to support increased restrictions on foreign imports—a belief that, if put in practice, would directly detract from their primary source of income. In addition, confidence in NAFTA significantly decreases among long-time members in the union compared to incoming Casuals. Indeed, in two of the three surveyed locals there were no Class-A members who reported “a great deal of confidence” in the treaty. Although our research design does not allow us to claim a casual effect of ILWU membership on dockworker attitudes over time, our results do indicate that increased tenure in the union is associated with member beliefs more in line with the union's overarching stance on international trade policy.

Conclusion

We examined the puzzling case of the ILWU—a union that has taken strong and consistent stances against a variety of trade-expanding policies and international agreements even though the union's membership appears likely to benefit from these agreements, at least in the short term. We examined several competing models and examined their empirical implications. In Table 4 we summarize how the empirical evidence presented bears on the proposed hypotheses.

TABLE 4. Hypotheses evaluated

The balance of evidence clearly favors an organizationally specific ILWU effect. The pattern of empirical findings is difficult to reconcile with union members' myopic self-interest or a logically coherent reading of standard trade theory. Findings do coincide with the union's interpretation of their motto, “an injury to one is an injury to all,” as meaning that the union's interests are bound together with the fate of working people the world over.

Our study also presents compelling evidence that unions can affect the political opinions of their members. We found consistent evidence that ILWU members were more likely to have crystallized opinions about trade policy issues and that they were more likely to favor trade restrictions and oppose trade agreements like NAFTA. Those having the longest and most intense exposure to the union differed the most from their non-ILWU matches. Further investigation showed that this difference is not due to an age cohort effect but seems to be directly related to exposure to the union.

The case of the ILWU demonstrates that organizational membership can influence policy preferences, but we now must consider the extent to which our findings are generalizable. There are several reasons to suspect the ILWU case is more widely instructive.

First, the ILWU, while certainly not representative of all unions, is not unique. The Australian dockworkers' union, the Waterside Workers' Federation (later renamed the Maritime Union of Australia) has a similar history of political mobilization around issues and causes far from the members' myopic economic interests, including opposing the Whitlam government's drastic tariff reductions in the 1970s.Footnote 78 Other unions, both in and beyond the anglophone world, have also maintained periods of significant political action beyond their immediate material interests.Footnote 79

Second, port work is not unique in its importance to the economy or in the survival of its unions. The ILWU has a significant strategic position in the world economy, giving it enormous leverage. But the transport sector more generally, extractive industries, the energy sector, parts of the public service, and in this just-in-time economy, workers on the assembly lines of high-demand goods are in similarly strategic positions in the global economy. We might start looking at organizations mobilizing these workers for other types of behavior similar to the ILWU's.

Nonetheless, there are characteristics of the ILWU that make it relatively distinctive, namely its ongoing industrial success and rank-and-file democracy. These attributes suggest possible scope conditions for our argument. Union leaders' calls to mobilize politically around causes that might hurt at the margin would be hard for members to swallow in a union fighting for survival or in a declining industry. Lack of mechanisms for challenging leaders' proposals and creating support for them should make it more difficult to mobilize in contradiction of myopic self-interest. Our research suggests that the combination of industrial success with an extremely open and participatory governance structure are the features most likely to engender contingent consent.Footnote 80 In short, the union's internal governance, external activism, and industrial success all appear to be mutually reinforcing.

Other research suggests that one additional condition may be even more important. The size of the ILWU and its relative uniqueness in the US context limit the actual changes the ILWU can effect in the world. Where unions have been able to affect policy more broadly they tend to be embedded in more encompassing organizational structures that are themselves more closely tied to political actors.Footnote 81 Future research should examine whether union political stances moderate when they are actually in a position to affect policy, for example when labor-based parties come to power after long spells in opposition.

Appendix: Matching Diagnostics

Figure A1 shows the standardized bias for each included covariate before and after matching. Standardized effect sizes are defined as the difference between the treatment and comparison group means, divided by the treatment group standard deviation. The standardized biases for all covariates and the distance measure between groups (as defined through the genetic matching algorithm) are all under 0.1 in the matched data.

FIGURE A1. Balance diagnostics

In addition, the histograms in Figure A2 show the distribution of propensity scores—defined as the probability of receiving the “treatment” given the covariates—in both the matched and unmatched datasets for ILWU (treated) and RDD (control) respondents.

FIGURE A2. Balance diagnostics

Finally, the jitter plot in Figure A3 displays each observation in the matched and unmatched treatment and control groups. The size of each point is proportional to the weight given to that observation. We discard observations in both groups for which there was not a successful match.

FIGURE A3. Balance diagnostics