Introduction

The Middle Draa Project is a diachronic and interdisciplinary investigation of the archaeology and heritage resources of the Wadi Draa in southern Morocco. Despite the fact that it is one of the most important of Saharan oases, the Wadi Draa has not hitherto received much detailed archaeological study and comparatively little has been published on its heritage (see Zaïnabi Reference Zaïnabi2004 and references in following section). The conventional wisdom has been that the oasis only developed in the Islamic period, but the presence of significant numbers of pre-Islamic burials in the valley suggested at the very least a more intensive Protohistoric phase. The initial aims and objectives of the project were thus to investigate the origins of the oasis across the Protohistoric and early Medieval phases, in the context of a preliminary survey of the Wadi Draa – sampling as wide a range of site types as possible and to include representative examples of all periods from prehistoric eras to early modern times. A key desideratum was to establish a baseline on the regional chronology, both through direct study of ceramic material collected from the sites visited, but also supported by a programme of absolute dating of organic materials extracted from walls, surfaces and small sondages at many of these sites.

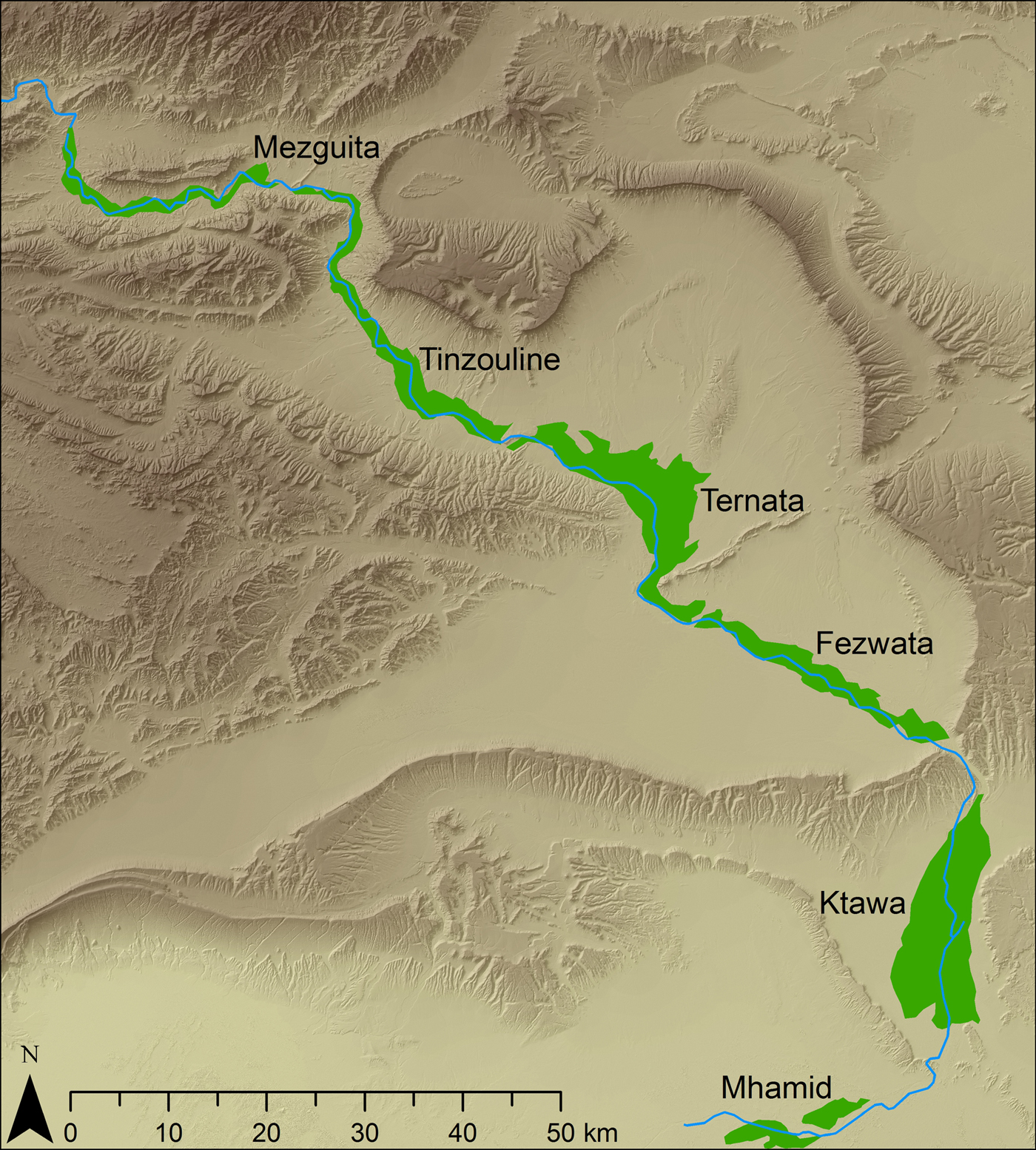

The c.200 km long Middle Draa contains one of the most extraordinary of all Saharan oases, within an overall 900 km long river valley (Jacques-Meunié Reference Jacques-Meunié1982, 142–46; Joly Reference Joly1948; Riser Reference Riser1996). The source of the Wadi lies in the High Atlas above Ouarzazate and for a substantial part of its initial course, running broadly north-west to south-east, the Wadi is a perennial river, fed by snow melt and rainfall run-off from the Atlas ranges (Jacques-Meunié Reference Jacques-Meunié1982, 145). The Middle Draa valley is bordered by mountains on either side (Figure 1). Only after making a turn to run east to west (‘le coude du Draa’), does the Wadi finally disappear underground beyond the final major oasis zone of Mhamid.

Figure 1. The Middle Wadi Draa, indicating the main oasis zones within the valley.

The Protohistoric occupation of the valley has remained shrouded in mystery, in part due to modern colonial-era assumptions about the primitiveness and nomadic tendencies of the early inhabitants (Desanges Reference Desanges1962). The key research questions were prompted by the pioneering work of Youssef Bokbot on the extensive Protohistoric funerary landscapes of the valley (Bokbot Reference Bokbot1991; Reference Bokbot, Gatto, Mattingly, Ray and Sterry2019) and the identification on satellite imagery by Sterry and Mattingly of hill-top settlements along the flanks of the valley. A starting point for the project was to assess whether southern Morocco might yield evidence of precocious and extensive oasis development (and even urbanisation) in the pre-Islamic period akin to the central Saharan civilisation of the Garamantes (Mattingly Reference Mattingly2003; Reference Mattingly2013; Mattingly and Sterry Reference Mattingly and Sterry2013). The wide distribution of burial tumuli and hilltop settlements of several distinctive morphologies throughout the Draa valley encouraged the view that this was a hypothesis that could be tested by closer archaeological examination of these and related sites. This article will focus on the Protohistoric phase, though important results have also been achieved for other periods (Mattingly et al. Reference Mattingly, Bokbot, Sterry, Cuénod, Fenwick, Gatto, Ray, Rayne, Janin, Lamb, Mugnai and Nikolaus2017).

The Middle Draa valley between Agdz and Mhamid is divided into a series of historic oasis zones (Rohlfs Reference Rohlfs2001, 53–59; Zainabi Reference Zaïnabi2004, 17–24): from north-west to south-east these are Agdz/Mezguita (30 × 1.5 km and 16 × 0.5 km palmeries), Tinzouline (20 × 1.5 km), Ternata (20 × 5–10 km), Fezwata (30 km × 3 km), Ktawa (20 × 6-8 km) and Mhamid (20 x 4 km). The largest town in the Middle Draa Valley is Zagora which lies halfway along the Wadi at a strategic mountain pass (Meunié and Allain Reference Meunié and Allain1956). While the great Moroccan centre of early medieval Saharan Trade was c.250 km to the east, at Sijilmasa, (see most recently, Messier and Miller Reference Messier and Miller2015; Capel Reference Capel2016), the Wadi Draa has historically been an important secondary corridor for caravans coming from the south to access the Atlas passes and reach Marrakech (Rohlfs Reference Rohlfs2001). Trans-Saharan trade is therefore another feature of the Wadi Draa story to examine.

The steep escarpments of the Draa valley create several ‘pinch-points’ where access to the next stretch of the valley can be controlled and which effectively divide the oasis into its series of palmerie zones. A key characteristic of the Wadi Draa is thus the presence of a series of natural ‘passages obligés’ along the length of the valley. Our study of these locations has revealed a rich and diachronic range of sites, which quite often included significant fortified structures designed to control/exploit movement and trade and to serve as defensive points for the various oasis sectors. These fortified sites date to Protohistoric, Medieval and Early Modern times.

Little prior archaeological research had taken place in the region. There are a number of well-known rock art sites including a large corpus of horse and rider/hunting scenes with Tifinagh inscriptions close to Tinzouline (for example, Glory et al. Reference Glory, Allain and Reine1955; Pichler Reference Pichler2000; Simoneau Reference Simoneau1972) and recently explored clusters of paintings at Ifrane'n’Taska and Foum Laachar in the Jabal Bani (Moumane et al. Reference Moumane, Delorme, Ewague, al-Karkouri, Gaoudi, Ista, Moumane, Mouna, Oumouss, Lmejidi and Zdaidat2019; Skounti et al. Reference Skounti, Zampetti, Oulmakki, Ponti, Bravin, Tajeddine, Nami, Huyge, Van Noten and Swinne2012). Preliminary satellite remote-sensing by Sterry as part of Mattingly's Trans-Sahara Project located extensive archaeological remains of hundreds of sites including hilltop and oasis settlements, cairn cemeteries of pre-Islamic type, irrigation systems and small dispersed settlements. The majority of sites are located within a few kilometres of the oasis belt, and cairn cemeteries in particular are located closest to some of the most heavily cultivated parts of the Wadi today.

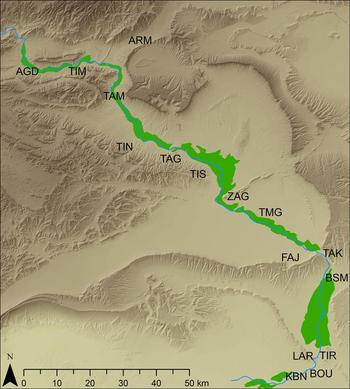

Overall, 364 sites of different periods have been recorded by the survey across 16 sub-areas of the Wadi Draa (Figure 2). Each of our survey sites is designated by a three letter code related to these sub-zones and a three-digit number (thus ZAG001 is the upper citadel on the summit of the mountain of Zagora by the modern town where the mission was based).

Figure 2. The area codes used by the Middle Draa Project mapped in relation to the topography of the Wadi Draa.

Protohistoric sites

Very significant results have been achieved in relation to the Protohistoric period (Figure 3). We have identified many examples of pre-Islamic sedentary sites on defended hilltops, often with defensive walls or enceintes and containing curvilinear enclosures and buildings (see Figure 4 for a sample of plans of sites dated to this period). Similarly located sites with rectilinear ranges appear in general to be medieval or early modern in date.

Figure 3. Protohistoric settlements and funerary zones recorded by the Middle Draa Project.

Figure 4. Comparative plans of Protohistoric hillfort sites.

A classic example of a Protohistoric hillfort is TIN001 (Figure 4), situated on top of the Foum Chenna cliff face that holds a dense concentration of rock art and Libyan inscriptions (TIN012 – see Pichler Reference Pichler2000; Simoneau Reference Simoneau1972). The hilltop site was protected by a series of substantial drystone walls, each with a single gateway. The walled core of the site comprises a series of enclosures and c.8–10 buildings leading off a central street to the highest point of the hill which was left empty (with a possible cairn at the top). There are at least two phases of construction visible: the earliest consists of loosely coursed boulders and the second of drystone slab masonry. A number of horse engravings were found built into the structures of the settlement implying a close relation between the rock art and the people of this site.

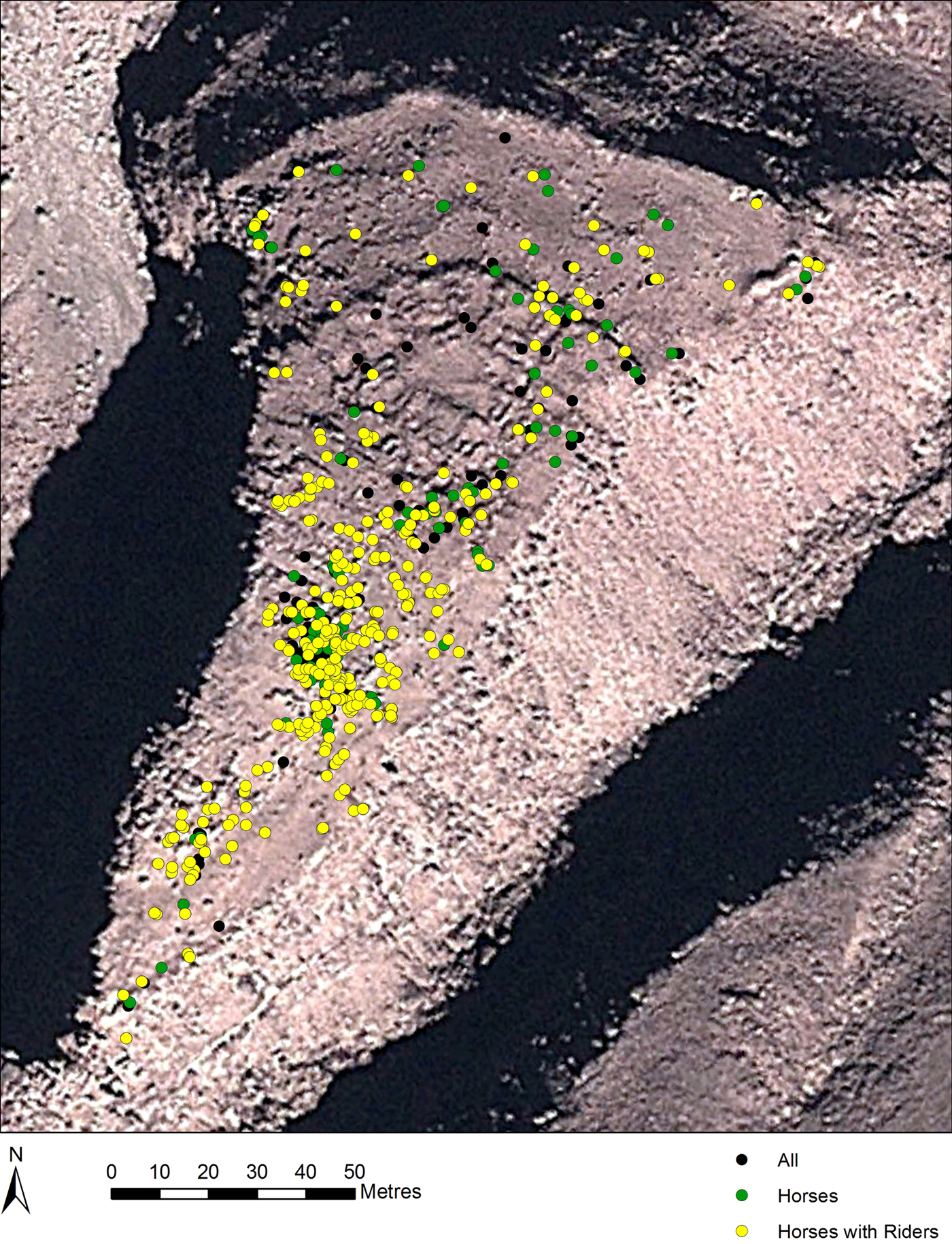

Figure 5. Distribution of rock art images of horses and horses with riders from TIN015.

TIN015 shares some similarities of layout, with a lower outer enclosure (that contained a few vestigial traces of structures), a middle zone entered through a gate in a second wall, where most of the habitation seems to have been concentrated. A central road led up through the settlement to a third area on the highest part of the site that was empty of structures, but which was covered in rock art on natural rock surfaces and many boulders (Figure 5). The vast majority of the images relate to hoses (or to crudely engraved quadrupeds which are thought likely to represent horses).

The highly structured placement of the rock art imagery in relation to both these settlements strongly supports the view that the two activities were at least in part contemporaneous. Both hillforts have produced pre-Islamic AMS dates (see below) and TIN015 has yielded both wheat and barley grains of the fourth to sixth centuries AD. The sites share a consistent handmade ceramic assemblage that is characterised by many cordon decorated jars and an absence of wheelmade or glazed material. Rotary querns are another conspicuous find on these sites.

The characteristic features of these two sites (enclosures, cordon decorated handmade jars, rotary querns and carbonised grain from the fourth to seventh centuries) are also found across the wider group of hillfort sites in the Draa (Figure 4). Two pre-Islamic hillforts have also been examined at Foum Larjam. LAR002 has yielded a series of AMS dates of third to tenth century date (see Figure 4). The site is a fortified hilltop comprising 50–60 rectilinear buildings, mostly constructed directly against the enceinte wall and a further loose scatter of buildings and terraces on the lower slopes of the hill. Access to LAR002 was via a stepped entrance at the north-west end of the enceinte, with an inner wall funnelling passage southwards once inside. The smaller one- or two-room buildings are focused in the northern half of the site and are likely to have functioned as storage units – each could possibly represent a family unit. The site and its immediate environs produced many rotary quern fragments and smooth pebbles used for grinding foodstuffs, indicating a strong association with oasis agriculture (also supported by barley grains dated to seventh century). The bed of the Draa and the nearest potential locations for oasis development are only 1–2 km distant here.

At LAR006 a hillfort of similar appearance to TIN001 and TIN015 was evidently abandoned for habitation and given over to funerary use (LAR005), with distinctive high conical corbels constructed all over the top of the hillfort in the sixth to seventh century if the AMS date is indicative – reusing much stone from earlier enclosures and buildings, which survive as only vestigial traces.

This suggests an engagement with agriculture in this period along the length of the valley. Moreover in four areas, TIM, TAM, TAG and BOU, we have also found evidence of Protohistoric sites located on the terraces directly alongside the Wadi Draa where the medieval oasis developed later. That is further suggestive of pre-Islamic origins for the oasis in the Wadi Draa. Several of these early sites also produced evidence of copper smelting and working, which would also be another benchmark for precocious socio-economic development. The identification of old mine workings, although not yet precisely dated, is another important step in exploring the contribution of the exploitation of metals in the valley (see Rosenberg Reference Rosenberger1970a/Reference Rosenbergerb, for published work on ancient mines south of the Atlas).

The Wadi Draa is notable for the number and density of its pre-Islamic burial monuments, primarily various forms of circular tumuli (for previous work, see Bokbot Reference Bokbot1991; Jacques-Meunié Reference Jacques-Meunié1958). Mapping of these from available satellite imagery had identified a total of at least 5,600 cairn tombs in the Ktawa region alone before the season began. Work was carried out in several zones, primarily LAR, TAK, ZAG and AGD and a more detailed typology of the monuments devised. The circular cairns have been divided into four main types (type 1: low cairn, type 2: mound cairn, type 3: drum cairn, type 4: corbel cairn), with a range of sub-types. The size of the largest monuments is really impressive. Mound cairns can be up to 10 m in diameter and stand up to 2 m high, while the conical corbelled cairns can reach more than 3 m in height and 6 m in diameter.

Some of these cairns are accompanied by small structures or platforms placed on the east side (most commonly to south-east) of the tomb. These are believed to be offering structures on account of the traces of many fragments of small animal bone (some burnt) found in association with some of these. The offering structures were built in a variety of shapes, some rectilinear, other curvilinear. Only rarely were tombs associated with pottery or other material culture (grinding stones were found by some) although almost all have been heavily robbed at some point in the past. Some human skeletal material recovered from a small number of targeted excavations and survey collections have been AMS dated. The dates obtained are in the same range as radiocarbon dates on similar tombs in the Moroccan desert regions (Bokbot Reference Bokbot, Gatto, Mattingly, Ray and Sterry2018; Bokbot et al. Reference Bokbot, Onrunia-Pintado, Rodriguez-Rodriguez, Rodriguez-Santana, Velasco-Vazquez and Amarir2005).

An intriguing locational aspect of the cairn cemeteries is that in several cases they have been built over protohistoric settlements of the types described above. These cairns appear to be of mid-first millennium AD date and only slightly later in date than the settlements although the precise chronology remains to be determined. This is reminiscent of similarly dated practices in Algeria where Saharan cairns were constructed from and on top of the remains of the Roman fort at Ausum and multiple farms in the Aures (Fentress and Wilson Reference Fentress, Wilson, Stevens and Conant2016, 44–45).

During the course of the 2015 season, the project was made aware of the discovery in the BOU area of a series of painted panels in an interior chamber of a large mound cairn (Zaïnabi Reference Zaïnabi2004, 40, for a photograph). The cemetery (BOU057) was relocated in 2016 and test excavations established the existence of painted funerary chapels in at least two very large mound tombs (c.15 m in diameter). The funerary chapels were set into their eastern flank and richly decorated with painted geometric designs and depictions of male and female figures. These figures are similar to those discovered in the famous tumuli with funerary chapels at Jorf Torba in western Algeria (Camps Reference Camps1986; Lihoreau Reference Lihoreau1993; Reygasse Reference Reygasse1950). The similarities in tomb form and decoration suggested a similar date around the mid-first millennium AD and this is now confirmed by two AMS dates. The painted tombs from the BOU area are clearly of high international importance.

Both through these paintings and the engraved horse and rider rock art we have new iconographic information on these societies. There is also the rare opportunity to contextualise rock art in terms of its placement within a settlement (Figure 5).

The overall distribution of demonstrably Protohistoric sites (and sites of suspected Protohistoric morphology) highlights the upper reaches of the Middle Draa as potentially more densely settled in this period (Figure 3). This should not surprise as the river flow is more abundant closer to the mountains and the metallurgical resources are also concentrated close to the river in the northern half of the valley. What is striking though is that even in the most southerly area (LAR/BOU areas), we have evidence for substantial activity in the pre-Islamic era.

AMS (Radiocarbon) Dating

In order to establish a firmer absolute chronology for the Draa valley and to help refine our ceramic typo-chronology, the MDP has embarked on a major programme of AMS radiocarbon dating of sites and structures. So far 87 samples have been submitted for analysis, with all but two returning a meaningful date and of these 31 are broadly Protohistoric (Table 1).

Table 1 Protohistoric AMS dates from the MDP.

Discussion

The first phase of the Middle Draa Project has amply achieved its objectives, in demonstrating the richness of the archaeological heritage of the valley. Sites have been surveyed from all the key areas of the Middle Draa, from the Agdz area to south of Foum Larjam. We have targeted a range of different settlement types, ranging from the large urban centres, to smaller oasis villages, to hilltop sites on the periphery of the oasis, to pastoral encampments and to mining works. We have started to codify the impressive evidence of funerary archaeology for both the pre-Islamic and medieval eras and have made some significant additions to the knowledge of rock art in the region in particular demonstrating an association between the horse imagery and two hilltop settlement in the Tinzouline area.

The most significant result is surely the demonstration that there were sedentary communities engaging in precocious oasis cultivation around the mid-first millennium AD (fourth to sixth centuries AD) at an earlier date than has previously been suggested or evidenced. This not only sheds a new light on the pre-Islamic settlement of the Western Sahara, but also has significant implications for our understanding of the subsequent introduction of Islam, the growth of Trans-Saharan trade and the later rise of the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties in this region (Sterry et al. Reference Sterry, Mattingly, Bokbot, Sterry and Mattinglyforthcoming).

Acknowledgements

The first phase of the MDP was conceived as a three year collaborative study between the University of Leicester and INSAP. The project directors are Youssef Bokbot (INSAP) and David Mattingly (University of Leicester), with Martin Sterry the senior Co-Investigator. Following a reconnaissance visit by these three in January 2015, three seasons of fieldwork took place in November 2015, November 2016 and January 2018. Participants in the fieldwork in addition to the three directors were as follows: Jonathan Adams, Touatia Amraoui, Joseph Bassett, Aurélie Cuénod, Corisande Fenwick, Maria Carmela Gatto, Jason Hagon, Katrien Janin, Andrew Lamb, Rabia el-Mehdaoui, Julia Nikolaus, Nicholas Ray, Louise Rayne, Nichole Sheldrick, Rachael Sycamore, Kevin White and Andrea Zocchi. Funding for the project was provided mainly by the European Research Council (ERC) as part of the wider Trans-SAHARA Project (PI Mattingly), with some additional support from the Endangered Archaeology of the Middle East and North Africa Project (EAMENA, CI Mattingly). Funding for the third season was provided by a British Academy Small Grant with additional support from the University of Leicester. The Society for Libyan Studies contributed funding to support the participation of Libyan archaeologists, but in the event this was prevented by a change in Moroccan visa rules. The project is grateful to Aomar Akerraz, at the time Director INSAP, for his support for the project. We also acknowledge the permissions granted to the project by the directeur du patrimoine culturel, Abdellah Alaoui. Aziz Jilalo of the Zagora Maison de la Culture took a deep interest in our work and generously made available work space for our finds team and a store for our finds and equipment. For the administrative and security clearances for our project, we thank the Governorat of the Province de Zagora, the Colonel Chef du District Militaire de Tagounit, the Ministry of Tourism (in particular Ahmed Chahid et Mahjoub Aarab), the Associations de développement culturel et protection de l'environment de Zagora.