Gustav Jenner (1865–1920) is known to historians as Brahms’s only long-term composition student.Footnote 1 Following an introduction by a mutual friend, Jenner moved to Vienna in 1888 at Brahms’s invitation and was to reside there for seven years (until two years before Brahms’s death), receiving Brahms’s counsel on matters artistic and professional, before leaving to accept a musical appointment Brahms had helped to arrange. To the end of his life, Jenner remained an outspoken proponent of traditional forms and harmonies and of ‘absolute’ music, conservative values no doubt both attracting him to and reinforced by his studies with Brahms. Scholars have recorded (mostly in German) the basic facts of Jenner’s biography and circumstances surrounding his interactions with Brahms and have noted Brahms’s general aesthetic influence on Jenner, but Jenner’s music itself – numerous songs and choral pieces, piano and chamber works, orchestral writing and other pieces – and particularly its relationship to that of Brahms, has received scant attention.Footnote 2 Although Jenner may not rank among history’s most extraordinary or innovative of composers – indeed, he remained strikingly traditional during the era of Schoenberg and Stravinsky – he did manage to achieve a unique status as Brahms’s composition student over a period of some years. Thus further examination of the musical relationship between these two figures should provide insight into not only how Brahms influenced less prominent composers in his circle and of the generation that followed him, but also the extent and nature of Brahms’s direct influence as a teacher.

Given that many readers will be unfamiliar with Jenner, this article begins with a brief overview of his life, studies with Brahms, relevant prose writings and musical output and reception; this is followed by a case study: the first in-depth comparison of Jenner’s only complete orchestral piece, his little-known Serenade in A major (1911–12), with its most obvious precedents, the orchestral serenades of Brahms. Despite obvious stylistic affinities between Jenner and Brahms, it is clear from Jenner’s prose writings that he placed a high value on artistic independence and originality, eschewing slavish imitation. Although a handful of commentators have remarked that in general Jenner’s music was not merely derivative of Brahms, there has been little attempt to explain how Jenner in fact distinguishes himself artistically in his works.Footnote 3 Jenner’s fundamental approach in the Serenade clearly draws much from Brahms, as critics have been quick to point out. For example, after Jenner’s Serenade was performed at a concert of the Marburger Konzertverein on 31 October 1913, one reviewer, despite remarking on the work’s ‘unmistakably modern impact’, pointed to its Brahmsian, ‘simple idyllic character’, ‘pastoral tone’ and small-scale orchestration featuring winds.Footnote 4 In 1977, the long-forgotten Serenade was resurrected for a performance at the commemoration of the 450th anniversary of the Philipps-Universität, prompting Ludwig Finscher to observe that Jenner and Brahms share an avoidance of large gestures, radical formal designs and programmaticism.Footnote 5 And yet there are stylistic discrepancies that arise inherently from differences in the composers’ historical positions and backgrounds, compositional priorities and skill levels. These include Jenner’s greater tendency towards an overabundance of themes rather than making more of less, as well as repetitions sometimes more literal and transitions less smooth than in Brahms. Beyond this, however, some of the differences between the Jenner and Brahms serenades result from deliberate choices on Jenner’s part, seeming to reflect his desire to distinguish himself and a wariness of the inevitable comparisons that would be drawn with the works of his teacher. Heavily valuing his artistic independence, Jenner tends to avoid in his Serenade some of Brahms’s most obviously distinctive compositional choices, and he takes care not to rely too heavily on any one Brahms work or movement as a model for his own Serenade. In Jenner’s work, then, we find the same dual emphasis on musical tradition and artistic independence evident in his studies and his prose writings – and, significantly, in the music of Brahms himself.

Biographical Overview

Jenner’s musical pursuits helped to guide his emergence from relative isolation to the musical centres in which he later studied and worked. Jenner was born Cornelius Uwe Gustav Jenner in Keitum, on the North-German island of Sylt, the youngest of Andreas and Anna Jenner’s three children.Footnote 6 The family was not particularly musical; Andreas came from a Scottish medical family (a physician himself, he was a descendant of Edward Jenner, who had discovered the vaccine for smallpox), and Anna from a family of merchants and seamen.Footnote 7 Due in part to his father’s disapproval of the ardour with which he engaged in musical pursuits, Jenner studied with only a handful of music teachers before encountering Brahms in his twenties. Jenner’s musical education began with piano studies with a teacher named Möllenkamp in Kettwig an der Ruhr.Footnote 8 By c. 1880, Jenner was writing his own music: short piano pieces, choral works and songs that were sometimes performed at the Gymnasium in Kiel where he was by then enrolled; he initially felt it necessary to hide his compositional activity from his family, as Andreas expected his son to follow him into the medical profession.Footnote 9 In 1884, Jenner began piano studies with the choral director at his school, Theodor Gänge; he also took organ lessons with a local teacher, Hermann Stange, whom he quickly outgrew.Footnote 10 In 1886, Jenner began travelling to Hamburg for lessons in composition and orchestration with Arnold Krug.Footnote 11 During the period of his studies with Brahms in Vienna, discussed in more detail below, Jenner spent his required year in military service with a volunteer infantry regiment in Schleswig (1889–1890); during this time, he managed to continue composing, and his first opus, a set of four Lieder, was published by Simrock in April 1890. While in Vienna, he served as Secretary of the Vienna Tonkünstlerverein (of which Brahms was Honorary President), piano teacher, conductor of two women’s choirs and Artistic Director of the Kirchenmusikverein Baden St Stephan (1889–1891).Footnote 12 Through the active support of Brahms and their mutual friend Klaus Groth, in 1895, Jenner was offered and accepted a post as Music Director at the Philipps-Universität in Marburg, where he was to conduct chamber, orchestral and symphonic works for the Akademischen Konzertverein.Footnote 13 In 1900, he received a promotion to the Professorship; four years later, the university awarded him an honorary doctorate. In addition to conducting, Jenner lectured at the university on such topics as Brahms, Bach, Schubert and the Lied, musical form, opera, the history of the orchestra and programme music.Footnote 14 During this period, he authored articles on various musical topics, as well as an extended account of his lessons with Brahms that yields insights into Brahms’s personality, compositional methodology and working mind; this is all the more valuable given that Brahms left little evidence of his compositional process, not writing much on such matters himself and famously destroying early works,Footnote sketches and manuscripts.Footnote 16 Jenner continued at Marburg for the remaining years of his life, raising two children with his wife Julie and helping to establish an important musical culture there as music director, teacher, lecturer and composer.Footnote 17 He is depicted in his maturity in Figure 1.

Fig. 1 Gustav JennerFootnote 15

Studies with Brahms

Jenner was introduced to Brahms through efforts of the latter’s friend, poet Klaus Groth. Jenner had been a schoolmate of Groth’s sons, and Groth had admired his early songs.Footnote 18 In 1887, Jenner sent a number of these to Brahms’s friend and publisher, Fritz Simrock, who showed them to Brahms; Brahms found that their composer was talented but not ready to be published.Footnote 19 Groth then wrote to Brahms, asking him to meet with Jenner and offer some counsel; the two composers met for the first time in late December, in Leipzig, to which Jenner travelled from Kiel expressly to meet Brahms while the latter was there to conduct a performance of his Double Concerto.Footnote 20

Brahms indicated a generally good impression of the works Jenner brought to their initial meeting – a choral setting of Groth’s ‘Wenn ein milder Leib begraben’ with orchestral accompaniment; pieces for women’s chorus; songs and a piano trio – but he did not hesitate to critique. He dismissed the choral music and the larger, more emotional of Jenner’s songs and showered back-handed praise on some of the shorter ones (for example, ‘That could have turned into a good song’).Footnote 21 Most enlightening for Jenner was Brahms’s response to the trio; Jenner writes,

With growing horror I saw how loosely and weakly the parts were joined. … I suddenly realized … that one has not written a sonata when one has merely combined several … ideas through the outward form of the sonata, but that … the sonata form must emerge of necessity from the idea.Footnote 22

In addition, Brahms criticized inactive basslines, weak harmonic choices and other problems, and Jenner found the work’s scherzo ‘transformed into pure nonsense’ before his eyes; Brahms requested he never again write anything of the sort.Footnote 23 Nonetheless, Jenner recognized in Brahms an underlying kindness and was inspired by the glimpse into a realm of compositional insight beyond his own understanding.Footnote 24

It is clear, however, from Jenner’s response to this preliminary criticism that, even during this early period, Jenner placed a heavy value on originality, strove to achieve it in his own works and derived pride when his music was perceived as original. Brahms’s criticism of the scherzo from his piano trio carried a particular sting; Jenner reflected on the movement: ‘I had attempted to be “original”. Following a public performance, my friends in Kiel and, if I remember correctly, even the newspapers had loudly praised the originality of this section’.Footnote 25

Early the next year, following additional correspondence with Groth and Jenner, Brahms invited the young man to Vienna to study. Although it was understood that Brahms himself might offer guidance, the master had arranged counterpoint lessons for Jenner with Eusebius Mandyczewski, his way of initially avoiding a commitment to formally accept a composition pupil of his own, something to which Brahms, not in the habit of doing, clearly did not want to be bound.Footnote 26 (Brahms’s resistance mirrors that of his idol, Beethoven, who similarly refused to take composition students with the exception of Archduke Rudolph.Footnote 27 ) With financial support from friends of Groth, Jenner arrived in Vienna in February 1888 and began meeting with Brahms about his compositions and with Mandyczewski for counterpoint lessons.Footnote 28

Although conservatories had become the mainstay of European musical education, there were certainly other major nineteenth-century composers (some, unlike Brahms, in fact affiliated with such institutions) engaging in free-lance mentoring of young or unestablished composition students, often as a result of some previous social connection or personal contact. Liszt, for instance, adopted teenage Carl Tausig as his protégée in the 1850s; reportedly one of Liszt’s favourite students, Tausig studied with him piano, composition and orchestration.Footnote 29 Mendelssohn, founder of the Leipzig Conservatory, not only privately cultivated young violinist Joseph Joachim, but also corresponded for decades with avocational composer and friend Wilhelm von Boguslawski, providing advice on Boguslawski’s compositions.Footnote 30 Tchaikovsky, formerly of the faculty at the Moscow Conservatory, engaged in a similar relationship with Vladislav Albertovich Pakhulsky, son-in-law of his patron, Nadezhda von Meck. Pakhulsky sent his compositions to Tchaikovsky, and Tchaikovsky wrote back with detailed comments.Footnote 31

Tchaikovsky appears to have been willing to undertake private tutelage of Jenner himself. Shortly after Jenner’s first encounter with Brahms, Jenner was introduced to Tchaikovsky at a party in Hamburg. At Tchaikovsky’s invitation, Jenner brought him the same works he had shown Brahms in Leipzig, but he was struck by the difference in response. Whereas Brahms had focused on structure, Tchaikovsky prioritized overall musical character. Jenner, who clearly wanted challenge and growth, found Tchaikovsky’s approach more encouraging and general, but less demanding and significantly less helpful than that of Brahms; when Tchaikovsky, by that time no longer teaching at the Moscow Conservatory, invited Jenner to travel back with him to St Petersburg, Jenner declined.Footnote 32

Schumann’s writings in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik indicate that he clearly viewed the promotion and encouragement of young composers as one of his missions, and Brahms’s role as mentor to Jenner in some ways of course recalls the relationship of Robert Schumann with Brahms himself decades earlier. During the short period between his meeting Brahms in late 1853 and the mental breakdown that sent him to Endenich in early 1854, Schumann lost no time in doing what he could to facilitate Brahms’s success as a composer, not only lauding him in the journal he had founded, but taking him into his home, encouraging him to embark on symphonic composition and providing other compositional advice, as well as introducing him to prominent musical figures.Footnote 33

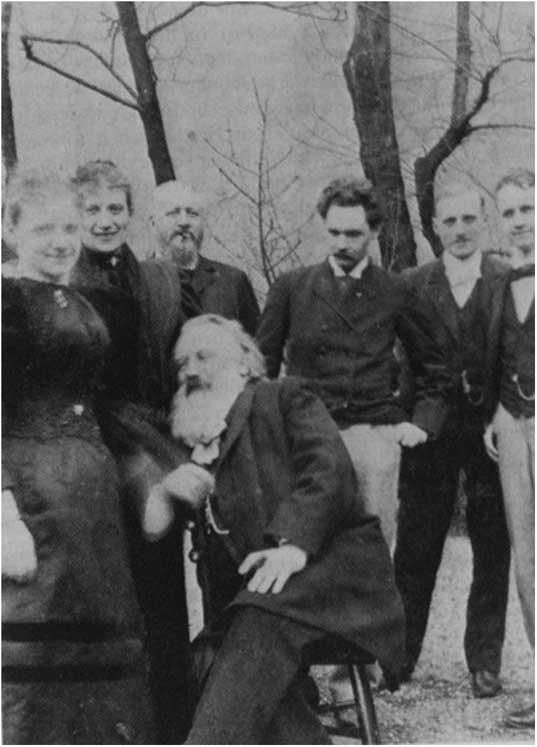

Similarly, Brahms’s personal investment in Jenner encompassed more than musical training. Brahms adopted a fatherly role in practical matters of daily living, helping Jenner find a place to live, lending household necessities and offering financial assistance and access to his personal library.Footnote 34 Brahms interacted socially with Jenner, lunching with him frequently at the Red Hedgehog and often returning there with Jenner and others after attending evening concerts; he also introduced Jenner to colleagues and friends, particularly the Fellingers, with whom Jenner became close.Footnote 35 Surviving photographs of Jenner include a number with Brahms and/or the Fellingers (see Fig. 2).Footnote 36 He also provided Jenner with career advice and opportunities. By 1891, reluctant to end his studies, Jenner had turned down offers of positions as Municipal Director of Music and as Repetiteur with the Wiener Staatsoper, a job that could have put him in line to become Kapellmeister; both offers were the result of Brahms’s connections.Footnote 37

Fig. 2 Brahms (seated) and Jenner (third from right) with friends (standing, L to R: Marie Röger-Soldat; Bertha von Gasteiger; Richard Fellinger, Sr; Richard Fellinger, Jr; Robert Fellinger) in Arenberg Park, Vienna, 26 March 1894Footnote 40

Although Jenner continued to endure sometimes painful criticism from Brahms, this motivated the young man to work harder to hone his skills, and Brahms’s investment in Jenner was clearly rooted in a fundamental belief in his potential, a belief Brahms expressed often in the company of others.Footnote 38 In November 1889, the Tonkünstlerverein, of which Brahms was head, awarded Jenner second prize in the category of work for chorus and mixed voices for his ‘Gute Nacht!’, a six-voice, unaccompanied setting of Eichendorff.Footnote 39 Marie Fellinger repeated to her son, Richard, Brahms’s proclamation that some of Jenner’s songs had brought him great joy, and Richard recalled one occasion on which Jenner arrived at the FellingerFootnote household so delighted with Brahms’s response to his latest work that he had been cartwheeling through the park.Footnote 41

Brahms took the tutelage of his pupil seriously. He insisted on thoroughly examining in advance any works to be discussed during lessons and addressed Jenner’s compositions with him in detail. Footnote 42 He focused on tightly controlled structure, logic and order and did not tolerate the prioritization of such things beneath emotional content. He provided advice on cadences, modulations, basslines and variation form, emphasized the importance of good counterpoint between melody and bass, and expressed his preference that accompaniment be equal to and independent of vocal lines; but he discouraged overly adventurous phrasing and complicated accompanimental parts.Footnote 43 (The Serenade examined below suggests the pupil took these lessons to heart.) In the composition of songs, Brahms preferred shorter pieces, prioritized the formal correspondence of text and music and recommended careful study of Schubert.Footnote 44 Brahms strongly encouraged Jenner in the use of other models as well, including sonatas of Mozart, Schubert and Beethoven – but this was not meant to restrict creative thought; through ‘imitating sonata movements’, Jenner later wrote,

I was supposed to learn that it is something completely different to recreate a form and to create music that is conceptualized and executed in the spirit of a form … . Only he who creates within the spirit of a form creates freely … in the other case form becomes a shackle and degrades into a fixed pattern.Footnote 45

Indeed, Brahms encouraged Jenner’s originality and artistic independence. For the most part, he declined to give specific assignments, allowing Jenner to bring for review whatever he had composed when ready; occasionally, Brahms requested compositions in certain forms (short songs and variations, then sonatas), but even then he permitted Jenner total freedom within those forms and in his choice of texts.Footnote 46 In keeping with a reticence surrounding his own compositional process that is otherwise manifest in his correspondence and destruction of old drafts and unpublished works, Brahms, Jenner claims, never mentioned his own works in Jenner’s lessons, let alone proffering them as models.Footnote 47

PROSE WRITINGS

Jenner’s prose writings (itemized in Appendix 1), published mainly in the first two decades of the twentieth century and including essays on such topics as Brahms, Beethoven, Handel, Bach and programme music, similarly reveal an emphasis on both traditional and originality. If Brahms was aesthetically conservative in comparison to Wagner and Liszt in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, then Jenner, holding many of the same views a generation later, may be considered even more archly so. Well into the twentieth century, Jenner was an outspoken proponent of the classical structures Brahms held dear; his writings frequently refer to the music of Brahms, often linking it to Beethoven (whom he also idolized) and other masters.Footnote 48

Although, like Brahms, Jenner appreciated aspects of Wagner’s work, in both the account of his studies with Brahms and particularly his 1917 essay on programme music he nonetheless expresses the objections typical of his aesthetic camp to the music of the so-called ‘New German School’.Footnote 49 Namely, this music is dependent on extra-musical elements for its coherence and comprehensibility; the extra-musical dictates not only the work’s character (as in Schumann’s short piano pieces, of which Jenner approved), but furthermore dictates its structure, thus undermining the independence of music as a medium of artistic expression.Footnote 50 Jenner takes issue with Wagner’s assertions that the old forms of absolute music had been exhausted and that programme music was the only way forward after Beethoven; this idea is refuted, in Jenner’s view, by ‘Brahms’s very arrival’ and he furthermore distances German musical heritage from the phenomenon of programme music, emphasizing that the latter’s origins are primarily French.Footnote 51

Much as Jenner’s writings stress the importance of tradition, they also prioritize originality; this is especially clear in his article on the influence of Eduard Marxsen on Brahms, his student. After praising Brahms’s originality in the very first sentence, Jenner observes that, if Brahms learned little from his studies with Marxsen (as Brahms himself attested), at least Brahms was spared the plight of being tempted to mimic a more compositionally influential teacher; he comments that Brahms must have been very ‘dependent on himself’, forcing himself to seek his own path.Footnote 52 Men of ‘weaker natures’, he warns, often fail to assert their artistic autonomy, getting ‘caught in the spell of a large, over-towering personality’, on whom they remain dependent; even despite Brahms’s natural independence, for ‘the unhindered unfolding of his individuality’, Jenner writes, there ‘was certainly to be desired no better teacher [than Marxsen]’, who left Brahms free from ‘the danger of imitation’.Footnote 53

Although Jenner points repeatedly to ties between his own teacher and earlier forebears (particularly Beethoven), he is careful to clarify that Brahms does not engage in slavish imitation, nor exhibit a lack of originality by adhering to traditional structures, but rather optimizes time-tested forms. The classical structures, he emphasizes, are ‘living forms’ that provide logical, coherent order within which the composer can create something new, for as Brahms taught him, the form arises organically from the musical materials of individual works as they are created.Footnote 54 In contrast to ‘New German’ composers and like Brahms himself, Jenner views these traditional structures not as obstacles to originality, but as means for original, coherent artistic expression. (There were, of course, many who agreed; well into the twentieth century, composers like Rachmaninoff and Vaughan Williams created new music in traditional forms and language rooted solidly in tonality, and many audiences continued – indeed still continue – to prefer it that way.)

MUSICAL OEUVRE, PERFORMANCE AND RECEPTION

The values of tradition and originality are naturally embodied in Jenner’s musical works as well. In generic representation and overall makeup, Jenner’s output bears some resemblance to that of Brahms. Several works, especially early ones, are lost and thought to have been destroyed by Jenner (just as Brahms destroyed many of his early attempts).Footnote 55 Predominant within Jenner’s surviving oeuvre are songs, of which he wrote over two hundred. Like Brahms, Jenner also composed choral works, including some for women’s choir, vocal quartets, motets and a number of folksong settings, but he avoided writing operas. Among Jenner’s instrumental works are three string quartets and a piano quartet; a trio for clarinet, horn and piano; three violin sonatas, a cello sonata and a piano sonata; canons for piano and one or more strings; piano ballades, variations and dances; and a number of other compositions, as well as cadenzas to piano concertos of Mozart and Beethoven. Like Brahms, Jenner seems to have struggled to compose a first symphony, although with considerably less success in the end, leaving only the two inner movements of an unfinished work composed in Marburg in 1912.Footnote 56 While engaged in this struggle to produce a first symphonic work, both composers turned to the orchestral serenade as a stepping stone.Footnote 57 Although a number of Jenner’s vocal works were published during his lifetime, this was the case for only a handful of the instrumental pieces. Several of Jenner’s works have been published for the first time within the past 30 years, thanks in large part to the efforts of Hans Heussner and the publisher B. Schotts Sohns in collaboration with the Hessische Musikarchiv in Marburg. A number of recordings have been issued as well; see Appendix 2.

Although his music is largely unknown today, it was performed and generally well received during Jenner’s lifetime. The music of his Viennese years was played at private gatherings of Brahms’s circle, and several works were aired publicly (including at the Tonkünstlerverein), especially by performers affiliated with Brahms, including singers Gustav Walter and Hermine Spies, pianist Marie Baumayer and violinist Marie Röger-Soldat.Footnote 58 Jenner’s directorial posts in Vienna permitted him a vehicle for performance of his polyphonic vocal works. His subsequent post at Marburg afforded him ample opportunity to compose for the musicians there, and in the early twentieth century, Jenner’s works were performed in a handful of other cities, including Darmstadt (1905), Berlin (1905), Leipzig (1905), Cologne (1906) and Frankfurt (1905 and 1910).Footnote 59 On the whole, they were well-received, except in Leipzig, where critics with ‘New German’ leanings criticized Jenner’s music so strongly for its conservatism that Jenner was discouraged from further promoting his works beyond Marburg, where they were appreciated.Footnote 60

JENNER’S SERENADE AND THE SERENADES OF BRAHMS

A number of Jenner’s works beg comparison with specific works of Brahms due to shared genre, key and/or text. We focus here on a clear candidate for such comparison: Jenner’s only complete orchestral work, the Serenade in A Major (1911–1912). Brahms’s two orchestral serenades, Opp. 11 (1857–1858) and 16 (1858–1859, with minor revisions (mainly markings) in 1875) are the most obvious precedents for Jenner’s Serenade – not only because of the personal tie between the composers, but also because the genre is one in which only a handful of people had written between the late 1850s, when Brahms revived it, and the time of Jenner’s composition. Serenades written in the intervening period for orchestras comprised of both strings and winds without featured soloists (like the Jenner and Brahms serenades) are few, consisting of far less familiar works by minor composers; examples include three serenades by Ignaz Brüll (Opp. 29 in F major and 36 in E major, both completed by the end of the 1870s, and Op. 67 also in F, published in 1893), as well as Max Reger’s Op. 95 in G major (1905–1906).Footnote 61 Of these, unlike the serenades of Brahms, none shares with Jenner’s serenade its main tonality, and only Brüll’s Op. 29 consists, like the Jenner and Brahms works, of more than four movements.

The gestation of Jenner’s Serenade was roughly concurrent with that of his article ‘War Marxsen der rechte Lehrer für Brahms?’ (1912–1913), in which, as we know, Jenner emphasizes the danger of studying with a well-known teacher whom one is subsequently prone to imitate.Footnote 62 Although concerned on the surface with the influence of Marxsen on Brahms, the article reflects Jenner’s preoccupation with an issue that must certainly have haunted him with regard to the influence of Brahms on Jenner’s own work. In comparing Jenner’s Serenade with the serenades of Brahms, we begin with broad issues and work our way to the more specific. As we will see, Jenner’s Serenade indeed exhibits a strong Brahmsian influence, but Jenner was by no means a stylistic clone of his teacher, and it is clear from his compositional choices that he valued and actively cultivated his individuality.

One distinctive aspect of Brahms’s serenades that likewise characterizes Jenner’s piece is a certain generic hybridity.Footnote 63 Both composers combine elements of the eighteenth-century-style serenade – for example, the basic structure, an aesthetic of simplicity drawing on the pastoral and the use of intimate, chamber-music textures – with characteristics that lend the works symphonic scope. One symphonic characteristic is the full scoring; although Brahms’s Op. 16 is scored more modestly, Jenner’s full ensemble is nearly the same as that of Brahms’s Op. 11, the sole exception being that Jenner opts for two fewer horns, perhaps a function of what was available to him at Marburg. Also symphonic in the serenades are the weighty opening movements, emphasis on extensive development and wide-ranging modulations.

Furthermore, Jenner’s Serenade, like Brahms’s Op. 16 in the same key, consists of five moments – and yet Jenner not only eschews Brahms’s most distinctive orchestrational choices in Op. 16 (namely the omission of violins and addition of piccolo), but also chooses a sequence of movement types and keys distinct from those in either of Brahms’s serenades. I assume basic familiarity with the Brahms works, but for reference indicate their large-scale plans alongside that of Jenner’s Serenade in Table 1.Footnote 64 Jenner’s inclusion of an intermezzo, although not entirely unprecedented in a serenade (see Brüll’s Op. 29/II, which is otherwise not clearly related), distinguishes his Serenade both from those of Brahms and of the eighteenth century, as does the lack of a proper slow movement. Although the intermezzo is Jenner’s slowest movement – in second place, whereas Brahms’s slow movements are both in third – it is not, strictly speaking, slow at all, but rather ‘moderato con sentimento’, with an animato ‘B’ section. Jenner also includes a theme-and-variations movement, which Brahms does not (although Op. 16/III is built on an ostinato), and while variation-based structures are not so unusual in serenades, they are often reserved for slow movements, whereas Jenner’s is allegretto.Footnote 65 Furthermore, Jenner does not emulate Brahms’s decision, in both serenades, to include both minuets and scherzos, but more conventionally chooses one – although his selection, the scherzo, is the less conventional for a serenade.

Table 1 Large-Scale Plans of Jenner and Brahms Serenades

Jenner’s key scheme is distinct as well. It is true that the collection of keys Jenner employs for his movements is almost the same as in Brahms’s Op. 16; both include the major and minor tonic as well as the subdominant. However, while, remarkably, neither contains a movement in the dominant, the rest is largely a function of conventional key relationships, so it is perhaps more significant that Jenner places none of the inner-movement (discretionary) keys in the same order as Brahms. He reverses the keys of the third and fourth movements and selects a second-movement key as diametrically opposed to Brahms’s choice as one can get: F-sharp minor vs Brahms’s C major, a tritone away and in a different mode. Furthermore, Jenner’s second movement has outer sections in F-sharp minor and a middle section in D major, reversing the key scheme of Brahms’s Op. 16/IV, a ‘quasi menuetto’ in D major with a trio in F-sharp minor. The reversal takes on yet another dimension if we consider that the second and fourth movements are reflections across the central axes of the two five-movement works; thus Jenner reverses both the relative roles of the two keys within the movement and the placement of the movement across the central axis of the five-movement sequence.Footnote 66

The juxtaposition of third-related keys in the music of Brahms – especially in tonic–submediant key relationships, as in Jenner’s second movement – has been noted and examined in a number of studies by Peter Smith.Footnote 67 Jenner does not employ tonal pairing here in quite the sense that Smith describes, with the two keys intertwining over the course of the movement as if each is vying for predominance, but rather Jenner assigns each key to its own distinct section of the intermezzo, with neither intruding into the other’s territory.

There is nonetheless something rather Brahmsian about Jenner’s use of third-related keys not only in this second movement, but in the key scheme of the entire work. In his A Major Serenade, Brahms shifts from the tonic key to a third-related key for the second movement. However, whereas Brahms moves up a minor third to C major for this scherzo, Jenner moves in the opposite direction, down a minor third from A to F-sharp minor in shifting to his own second movement. Brahms then returns to A (minor) for his third movement, whereas Jenner continues his shift down by third, placing his theme and variations movement in D major. Thus Jenner’s placement of the intermezzo’s middle section in the submediant key of that movement mirrors the placement of the intermezzo itself in the submediant key of the work as a whole, and, for that matter, the third movement is in a submediant relationship to the intermezzo’s own F-sharp minor. In this way, Jenner’s key scheme is clearly distinct from that of the Brahms serenade with which it shares its primary tonality. However, Brahms’s D Major Serenade, remaining in the tonic for the second movement, moves down by third to B-flat major for the third movement, and then down again by third to G major for the fourth, before returning to the tonic for the penultimate movement and finale. In this sense, Jenner’s tonal scheme, similarly returning to the overarching tonic minor/major key for the last two movements, is remarkably close to that of Brahms’s op. 11. However, this parallel is somewhat obscured not only by the differences in the two works’ tonic keys and numbers of movements, and by the placement of the initial tonal shift in the second movement rather than the third, but also by Jenner’s once again doing the opposite of Brahms, here by moving down by minor third to F-sharp minor for his second movement, whereas Brahms descends from his tonic D by major third to the key of B-flat major for his op. 11/III.

Scholars of Brahms and other composers frequently refer to the work of Harold Bloom in discussing issues of compositional influence, and Bloom’s theory of the ‘anxiety of influence’ certainly seems to apply here.Footnote 68 In doing the opposite of Brahms in certain respects, Jenner may perhaps be understood to deny or conceal the extent of his teacher’s influence.

As one of the fundamental lessons Jenner distilled from Brahms’s teaching was that form – particularly sonata form – should grow organically from the materials, not be imposed upon them or handled inflexibly, it is important to consider how Jenner’s and Brahms’s general handling of motivic materials and sonata form compare in these works. Particularly notable in Brahms’s serenades is the use of sequential repetition as a common means of constructing the basic thematic materials.Footnote 69 In Op. 11/I, for example, the second phrase is a transposed version of the first, sequencing occurs internally at bars 8–10 and 16–18 and, beginning at bar 19, the music is constructed of a series of sequential repetitions of short units. The second theme, starting at bar 112, begins with an ascending arpeggio moving up sequentially by fourths. The closing materials of the exposition, starting at bar 177, likewise begin sequentially. Sequential repetition pervades both of Brahms’s serenades, and the use of this developmental technique in constructing themes facilitates the natural evolution of these themes into transitional and developmental passages, where sequential repetition can continue to be applied to the basic motives, and thus it facilitates the evolution of the motivic and thematic materials into the broader forms.Footnote 70 Jenner also employs this technique, albeit not so consistently. In his first movement, within primary statements of main thematic materials, exact repetition is more (indeed quite) common, whereas sequential repetition is more often reserved for elaborative, transitional and developmental passages. In subsequent movements, however (beginning with the first four bars of the intermezzo, for example), sequential repetition becomes more common as a means of generating the main materials themselves.

Nonetheless, the multitude and brevity of Jenner’s thematic ideas lends the music a restless urgency that contrasts with the more relaxed, expansive feel of Brahms’s serenades. Given the scale of Jenner’s work, it is striking how little time he gives to both the primary and secondary themes of his outer movements, almost immediately introducing thematic fragmentation, modulation and additional motives or themes. By contrast, in Brahms’s sonata and sonata-rondo serenade movements, the first and second theme groups usually begin with two-fold thematic statements, often with variances in orchestration and other elements the second time, but with the thematic idea reasonably intact. (The one exception is at the beginning of Op. 16/I, but Brahms reverts to his usual approach for the second theme.) Jenner may attempt to prove his inventiveness by constantly reworking his materials and introducing new ones, but there is something to be said for the principle that simplicity and making more of less is the mark of a more mature, profound level of skill.

Perhaps excessively aware of Brahms’s advice regarding organicism, Jenner more heavily emphasizes transitional passages and development in non-development sections, including expositions – and yet it seems that he still struggles to make the materials and form evolve naturally as in the music of his teacher. For example, one thing that sets Jenner’s first movement apart from either of Brahms’s opening movements is the degree of disjunction between the first theme group and the transitional material that follows. Jenner creates a stark break in texture, register, dynamic level, melodic content and rhythmic character at the outset of the transition (bar 36), whereas, in both of his opening sonata-allegro movements, Brahms is more subtle, cultivating a sense of flow and continuity between the expository themes. Jenner also appears less concerned than Brahms with the evolution of thematic and motivic materials across movements. He creates no obvious thematic relationships between outer movements, and the recurring rhythmic patterns, such as a variety of ‘long-short-short’ rhythms, are generic. By contrast, in Brahms’s Op. 11, for example, the finale’s second theme is an alteration of the work’s opening, lending a sense of cyclicity to the whole, and characteristic double-dotted rhythms link the third and sixth movements.Footnote 71

Jenner’s sonata forms nonetheless share with those of Brahms several basic features worth noting. Brahms’s opening and Jenner’s outer movements all abandon the second theme in the development section. Their developments sometimes stray quite far harmonically, and that of Jenner’s finale shares with Brahms’s Op. 11/I a particular emphasis on the ‘leading-tone minor’. Both composers abbreviate their first theme groups in the recapitulation. In the initial movements of both Jenner’s Serenade and Brahms’s Op. 11, the first theme groups are halved or nearly so in the recapitulation, and in his ternary-form second movement, Jenner achieves the abbreviation of the first theme in the recapitulation specifically by adopting Brahms’s typical technique of removing the first of the theme’s two preliminary statements. With both composers, second themes are left generally intact in the recapitulation, usually with changes in orchestration or other relatively minor elements. Both composers engage in secondary development in the recapitulation and coda. The opening movements of the two A major serenades have similar proportions (expositions comprising roughly 31.5% of both movements; developments 23.5% and 26.5% in Jenner and Brahms, respectively; recapitulations 25.5% and 27%; and substantial codas approximately 19.5% and 15%). Furthermore, the development sections of both movements (starting in Brahms at bar 119 and in Jenner at bar 95) begin with versions of their respective works’ opening bars in the tonic key, as though initiating repeats of the (unrepeated) expositions. Both developments then make use of similar, distant key areas, including those bearing chromatic relationships to the tonic, particularly the Neapolitan key, B-flat major, as well as A-flat major/minor.Footnote 72 In the recapitulation, Jenner leads his first theme into the unexpected key of B major (starting with the chromatic shift in bars 172–173); Brahms similarly moves at the end of the theme group chromatically from A major through B minor to C major (bars 257–270). In both codas, the first and second themes are fragmented and combined, and there is a temporary departure from the tonic key involving the subdominant.

Nevertheless, in his Serenade, Jenner avoids some of the more distinctive aspects of Brahms’s forms. Jenner’s handling of recapitulations is conventional in that he always begins in the tonic key and states the themes in their original order, whereas in Brahms’s op. 11/I, the first theme group is recapitulated starting in the subdominant, and in the same work’s finale, Brahms recapitulates the second theme before the first. Jenner neither removes nor introduces two-against-three/three-against-four rhythms in his recapitulations, as does Brahms in Op. 11/VI and Op. 16/I. Nor does Jenner emulate the structural idiosyncrasies in Brahms’s handling of dance movements. He does not, for example, provide any paired dances like the trio-less minuets of Brahms’s Op. 11/IV. Furthermore, each of Brahms’s scherzo movements exhibits a unique pattern of section repeats, and Jenner’s is different from all three.Footnote 73 Aside from the lack of repeat of the trio’s second half, Jenner’s scherzo is of textbook form, eschewing the irregularities of Brahms’s Op. 11/II, namely the development of the movement’s opening ‘a’ material at the beginning of the second section (starting at bar 28), before the introduction of contrasting ‘b’ material in the dominant, as well as failure to fully recapitulate the ‘ba’ structure of the scherzo’s second half.

In his finale, Jenner distinguishes himself from Brahms not only by employing sonata-allegro form in place of rondo, but also by deviating from sonata archetype in ways that Brahms’s serenade movements do not (see Fig. 3) The most distinctive aspects of this movement’s structure are double statements of Theme 2 in the exposition and recapitulation, resulting in relative de-emphasis on Theme 1. In Jenner’s exposition, following a fugal transition, the second theme appears, as expected, in the dominant (bars 21–29); this is followed by a substantial passage of new transitional material and, remarkably, a return to the second theme, again in the dominant, for several more bars (bars 43–50). In the recapitulation, the second theme is handled with typical straightforwardness, again appearing twice, now in the tonic both times. Other interesting features not found in the Brahms serenades include the presence of a brief new development theme (bars 102–109), as well as the coda’s beginning with a recollection of a thematic idea introduced in the retransition (bars 190–197).

Fig. 3 Form of Jenner, Serenade, mvt V

Moving from formal issues to other matters, we may observe another quality shared by all three serenades – one hearkening back to eighteenth-century serenade tradition: an emphasis on horns and winds, sometimes in passages with intimate, chamber-music textures. From the outset of Op. 11, these instruments are showcased melodically. Of the work’s six movements, horn solos appear in all but the second and fourth, and thin textures featuring the winds almost exclusively can be heard, for example, in the codas of the first and third movements and throughout the first menuetto. In Op. 16, the winds and brass become, if anything, more prominent and independent and the strings (now without violins) more subsidiary. Jenner likewise emphasizes horns and winds from the start, sometimes in lightly scored passages recalling parallel moments in the Brahms works. Compare, for example, the transition between themes in Jenner’s first movement and that between the refrain and first episode of Brahms’s Op. 16/V, shown in Example 1. Both begin with sudden reductions to two voices each in clarinets and bassoons, which play piano in short, legato units, joined after several bars by homorhythmic strings and one of the two higher wind parts. Generally speaking, however, Jenner’s approach is more comparable to that in Brahms’s Op. 11 than Op. 16 in that the strings remain more balanced with winds and brass.

Ex. 1a Jenner, Serenade, mvt I, bars 36–43Footnote 76

Ex. 1b Brahms, Serenade No. 2, mvt V, bars 54–63Footnote 77

The prominence of horn (including hunting calls) and winds is one aspect of the pastoral, rustic style pervading these works more generally, a style also suggested by drones and open fifths (and the slow harmonic rhythm to which the former sometimes correspond).Footnote 74 Drones in fact appear in each of Brahms’s serenade movements, starting with those in open fifths at the beginning of Op. 11. Although Op. 16 does not begin with drone accompaniment, it does start with a rustic open fifth in clarinets and bassoons. Jenner, too, adopts these features in every movement, also from the first bars.Footnote 75

Several other characteristically pastoral traits are present in the serenades of both composers, even if sometimes manifesting themselves somewhat less extensively or differentlyFootnote

inFootnote

Jenner’s work than in those of Brahms. For instance, passages in parallel thirds are featured in virtually every movement of Opp. 11 and 16, appearing also in Jenner, although less frequently. Another such feature is an emphasis on the subdominant. Although all three serenades contain movements in their subdominant keys, an emphasis on the subdominant in general is more consistent with Brahms, appearing in nearly every movement, often at important structural places, such as the recapitulation of Op. 11/I.Footnote

78

Lilting melodies in triple or compound metres, including especially

![]() or

or

![]() , are also characteristic of the pastoral idiom.Footnote

79

In Op. 16, Brahms employs

, are also characteristic of the pastoral idiom.Footnote

79

In Op. 16, Brahms employs

![]() for the ‘quasi menuetto’ and a lilting

for the ‘quasi menuetto’ and a lilting

![]() in the work’s slow movement; as usual, Jenner eschews Brahms’s more conspicuous choices, instead relegating his own use of triple metre to the commonplace

in the work’s slow movement; as usual, Jenner eschews Brahms’s more conspicuous choices, instead relegating his own use of triple metre to the commonplace

![]() . Interestingly, unlike Jenner, Brahms incorporates dotted and triplet/sextuplet rhythms into every serenade movement not in a prevailing triple metre; thus the lilting, triple feel infiltrates even the duple- and quadruple-metre movements. Even or balanced phrasing, another characteristic pastoral element, is common in Brahms, but in both of his serenades the level of clarity and evenness in phrasing appears correlated with distance from the centre of the work, with the least balance in the innermost movements, helping to articulate a trajectory of increasing tension/instability and then resolution/stability over the course of each work.Footnote

80

On the whole, Jenner’s phrasing is most often balanced; he does not articulate this same clear trajectory.

. Interestingly, unlike Jenner, Brahms incorporates dotted and triplet/sextuplet rhythms into every serenade movement not in a prevailing triple metre; thus the lilting, triple feel infiltrates even the duple- and quadruple-metre movements. Even or balanced phrasing, another characteristic pastoral element, is common in Brahms, but in both of his serenades the level of clarity and evenness in phrasing appears correlated with distance from the centre of the work, with the least balance in the innermost movements, helping to articulate a trajectory of increasing tension/instability and then resolution/stability over the course of each work.Footnote

80

On the whole, Jenner’s phrasing is most often balanced; he does not articulate this same clear trajectory.

Perhaps also connected with the idea of the pastoral is an affinity, in all three serenades, for melodic lines that waver between two adjacent pitches, calling to mind the slow trill of birdsong. This appears in several movements, often at clear structural points, such as beginnings of themes. In Op. 11/I, see for instance the development section (upper strings in bars 249ff, winds at bars 263ff and winds and strings at bar 279–292; Ex. 2a). At the opening of Op. 11/II, strings and bassoons oscillate between octave Ds and Es; this also serves as the basis for the movement’s coda (bars 148–154). The figure, although brief, is highlighted by the unison texture. Despite the E-flat major, full triadic harmony and dotted rhythm, the gesture opening the adagio (Ex. 2b) is similar, is given equal status as head motive and again serves as the basis for material in the last few bars (246ff).Footnote

81

Although the melodic wavering is less extensive in the fourth movement, the gesture to and from an upper neighbour continues to feature prominently (as do oscillating accompanimental figures), for example initiating each of the first three phrases (bars 1, 3 and 5), which are repeated and developed. In Op. 11/V, neighbour-note wavering appears in the first violins at bars 19–22, where the lower-neighbour figure evolves into a more steady oscillation between E and F

![]() . Complete upper neighbours feature prominently throughout the viola accompaniment of the finale’s first episode (bars 71ff, especially from bar 95) and are recalled in the transition (bars 142ff) and elsewhere (see for example bars 171ff and 328ff). A similar tendency is present in Brahms’s Op. 16/I, for example, in the clarinet (bars 71ff) and flute (bars 100ff; Ex. 2c), reappearing with modified orchestration in the recapitulation and coda. In the second movement, written-out trill-like figures appear in the viola between Themes 1 and 2 (see especially bars 22–25), and trills appear in the piccolo in the finale (starting at bar 253 and marking the work’s end). Similarly, Jenner’s opening theme, included below in Example 5, begins by wavering between F

. Complete upper neighbours feature prominently throughout the viola accompaniment of the finale’s first episode (bars 71ff, especially from bar 95) and are recalled in the transition (bars 142ff) and elsewhere (see for example bars 171ff and 328ff). A similar tendency is present in Brahms’s Op. 16/I, for example, in the clarinet (bars 71ff) and flute (bars 100ff; Ex. 2c), reappearing with modified orchestration in the recapitulation and coda. In the second movement, written-out trill-like figures appear in the viola between Themes 1 and 2 (see especially bars 22–25), and trills appear in the piccolo in the finale (starting at bar 253 and marking the work’s end). Similarly, Jenner’s opening theme, included below in Example 5, begins by wavering between F

![]() and E. See also the emphasis on the chromatic E-D

and E. See also the emphasis on the chromatic E-D

![]() motion in bars 18–26, leading directly back into E-F

motion in bars 18–26, leading directly back into E-F

![]() alternation in the oboe. This is recalled in the coda (bars 269–270 in oboes and 289ff in first violins, then bassoons and cellos), which also begins with a similar gesture (bars 241–244), recalling material from the development (bars 113–116).Footnote

82

In Jenner’s second movement, the ‘B’ section begins with a similar semiquaver wavering in the winds (bars 41ff), later moving to strings (bars 61ff; Ex. 3). The opening of the finale features oscillation between G and A in the first full bar. Related, complete lower-neighbour figures occur in several places in this movement and also feature prominently in the third movement, beginning in the main theme.Footnote

83

alternation in the oboe. This is recalled in the coda (bars 269–270 in oboes and 289ff in first violins, then bassoons and cellos), which also begins with a similar gesture (bars 241–244), recalling material from the development (bars 113–116).Footnote

82

In Jenner’s second movement, the ‘B’ section begins with a similar semiquaver wavering in the winds (bars 41ff), later moving to strings (bars 61ff; Ex. 3). The opening of the finale features oscillation between G and A in the first full bar. Related, complete lower-neighbour figures occur in several places in this movement and also feature prominently in the third movement, beginning in the main theme.Footnote

83

Ex. 2a Brahms, Serenade No. 1, mvt I, bars 263–265

Ex. 2b Brahms, Serenade No. 1, mvt III, bars 1–5

Ex. 2c Brahms, Serenade No. 2, mvt I, bars 70–74

Ex. 3 Jenner, Serenade, mvt II, bars 41–44

Another important aspect of Brahms’s style in the serenades – especially Op. 11 – is the way in which this music so clearly draws on that of Haydn and other composers. In combination with the choice of genre itself, as well as the emphasis on the pastoral, common in the eighteenth-century serenade, Brahms’s references to specific earlier works clearly represent Brahms’s intention to invoke his musical heritage. Apart from the oft-remarked ‘Haydnesque’ feel of some of the themes in Op. 11, there are also references to specific works. In particular, it is widely acknowledged that the opening movement alludes to the finale of Haydn’s last symphony (No. 104); given that this was Brahms’s initial attempt at a large-scale orchestral work, Brahms thus appears to take up the reigns where Haydn (symbolic of Brahms’s musical forebears more generally) left off.Footnote 84 Allusions to Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann (and of course the stylistic influence of Mozart) have been cited as well.Footnote 85

While Jenner’s Serenade, too, clearly nods to the past in its generic designation and style, I am not aware that it alludes to any specific eighteenth-century models – although comparison of certain passages of Jenner’s Serenade with specific passages from Brahms suggests, if not deliberate allusion, then at least perhaps an unconscious influence. We have already observed the strong resemblance between parallel transitional passages in Jenner’s first movement and Op. 16/V. There is another potentially meaningful connection between these two movements: the repeated F–E grace-note figure in the oboes at bar 31 in Brahms’s Op. 16 finale and the trill between these pitches in the higher register at the close of the work call to mind the similar gesture with which Jenner opens his Serenade; see Examples 4a–b and 5a. One might almost read the beginning of Jenner’s Serenade as a reference to the close of Brahms’s second and final work in this genre – as though Jenner picks up where Brahms left off, much as Brahms appears to do with Haydn. Both A major serenades begin in ‘cut time’, piano, with clarinet as a featured melodic instrument and a melodic line tracing a gradual ascent from the fifth scale-degree to tonic in the first four bars. In addition, consider, for example, the opening of Jenner’s Serenade in comparison to the beginning of the A minor third movement of Brahms’s Op. 16, shown in Example 5. In both movements, the opening melodies, first heard doubled in the flute and clarinet parts, trace trajectories from the fifth scale-degree, E, to the sixth and back, then down by step to the second scale-degree and up a step to the third, from which both lines launch into upward arpeggiated gestures. And yet if the relationship here is meaningful, it is heavily masked by the differences in mode, tempo, metre and register (and the different positions of the movements within their respective works likewise discourage comparison).

Ex. 4a Brahms, Serenade No. 2, mvt V, bars 31–34

Ex. 4b Brahms, Serenade No. 2, mvt V, bars 389–396

Ex. 5a Jenner, Serenade, mvt I, bars 1–4

Ex. 5b Brahms, Serenade No. 2, mvt III, bars 1–3

There is also some resemblance between the beginnings of this Brahms finale and Jenner’s A minor fourth movement, shown in Example 6. Both start with loud, single-ascending-leap gestures in rhythmic unison to a sustained downbeat note. (The high A to which Brahms leaps is the same pitch from which Jenner’s melody begins.) In each, attainment of the melodic apex is followed, at the end of the next bar, with a dramatic drop to piano and textural thinning. Both composers focus here first on the strings plus one other instrument (clarinets for Brahms and horns for Jenner), but allow the basses to drop out for several bars, and both set into motion here accompanimental figures involving pizzicato repeated notes. Jenner introduces the main melody in the flutes and first violins (bar 8), whereas Brahms’s melody enters in the clarinets, but Jenner’s begins with a gesture that, however generic, nonetheless resembles the one at the opening of Brahms’s rondo: a leap from an upbeat dominant pitch to the downbeat tonic pitch above, a high A.

Ex. 6a Jenner, Serenade, mvt IV, bars 1–12

Ex. 6b Brahms, Serenade No. 2, mvt V, bars 1–6

Further comparison with Brahms’s symphonies and other works and with other serenades of the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries may well prove fruitful. Although this is generally beyond the scope of the present study, one or two possible connections to Brahms’s symphonic repertory deserve mention. The first movement of Brahms’s First Symphony famously incorporates a persistent three-quavers-plus-crotchet repeated-note motive heard most prominently in the development section, in the timpani and other instruments. A similar motive, with a triplet in place of the three quavers, can be heard in the finale of Jenner’s Serenade (bars 181–190; see Ex. 7a–b), again in the timpani. (This figure also appears repeatedly in the low strings in Brahms’s op. 16/V (as at bars 10–18 and 299–303).) The appearance of this rhythm in Brahms’s Symphony has been interpreted widely by scholars and critics as a reference to the ‘Fate Motive’ from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, a work that shares with Brahms’s First a C-minor-to-C-major trajectory. As Jenner grapples with his initial orchestral piece (and, at approximately the same time, his first proper symphony), he thus seems to hearken back to his teacher’s first successful symphonic work and, perhaps, to the simultaneously inspiring and intimidating Beethovenian legacy on which Brahms drew.

Ex. 7a Brahms, Symphony No. 1, mvt I, bars 273–281Footnote 86

Ex. 7b Jenner, Serenade, mvt V, bars 181–190 (continues on next page)

There is also a likeness between the melodically angular opening of Jenner’s F-sharp minor second movement and material from the E minor passacaglia finale of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony as heard most clearly at the beginning of the fourth variation (beginning at Brahms’s bar 33), shown in Example 8. Despite differences in key, dynamic level and orchestration, these

![]() melodies, in similar registers, both include an upward leap of a fourth or fifth from the second to the third beat of the first bar and a single descending step concluding on the downbeat; in both, this initiates a dotted-rhythm ascending leap of a minor third, followed by a most distinctive leap downward by major seventh (enharmonic at first, in Jenner’s case) and then an immediate repetition of the entire motive with some development.

melodies, in similar registers, both include an upward leap of a fourth or fifth from the second to the third beat of the first bar and a single descending step concluding on the downbeat; in both, this initiates a dotted-rhythm ascending leap of a minor third, followed by a most distinctive leap downward by major seventh (enharmonic at first, in Jenner’s case) and then an immediate repetition of the entire motive with some development.

Ex. 8a Jenner, Serenade, mvt II, bars 1–8

Ex. 8b Brahms, Symphony No. 4, mvt IV, bars 33–40

Despite the stylistic conservatism of Jenner’s Serenade for its time (the work was completed in the same year as Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and the year before the premiere of the Rite of Spring), certain aspects of the piece, such as the incorporation of an intermezzo, the elimination of minuets and the weighty finale, suggest an updating of this classical genre. Finscher has commented that Jenner seems to ‘distance himself … decisively from conventional serenade-nostalgia’, particularly in the finale, with its departure from folk-like, light-hearted material in the classical vein; he finds the work exemplifies an ironic distancing from Classicism, and Heussner goes so far as to remark that, in its ‘sonic transparency’, as well as its aesthetic of beauty, sensitivity and vulnerability, the work appeared ‘strangely modern’ in the context of the fin-de-siècle.Footnote 87

Jenner was undeniably influenced by Brahms’s work, but he also demonstrably placed a high value on artistic independence – perhaps one of the very things Brahms found attractive about working with him. And close examination suggests that, while adopting fundamental elements of Brahms’s approach, Jenner’s Serenade also differs in some not-insignificant ways from those of Brahms. Some of the discrepancies naturally result from differences in the skill levels and experience, musical reference points, priorities and inherent natures of the composers, and cannot be assumed the result of deliberate calculation on Jenner’s part. However, roughly concurrently with the composition of this work, Jenner expressed in print a clear wariness of the undue influence of a highly regarded teacher upon his pupil. In keeping with Bloom’s theories about the anxieties surrounding compositional influence, there are choices Jenner makes in composing his Serenade that suggest this concern. These choices manifest as an avoidance of, if not general aspects of the Brahmsian approach, then at least the most conspicuously distinctive aspects of Brahms’s two serenades. Jenner also avoids working too heavily with one particular model, combining elements of Op. 11 and Op. 16; his Serenade resembles one Brahms movement or work in one respect here and another in a different respect there. In not mirroring any one model too closely for too long, the resulting material is more uniquely Jenner’s own. The irony of course is that if Jenner attempts to differentiate himself by avoiding strict imitation of a Brahmsian model, in so doing he nonetheless defines himself and his musical work in terms of their relationship to his teacher. A final irony: in a way, this struggle only deepens Jenner’s link to Brahms, who, in the shadow of Beethoven and other great masters, was famously plagued with his own ‘anxiety of influence’ as he, too, navigated towards a balance between tradition and originality, musical lineage and artistic individuality.

APPENDIX 1

Published Prose Writings of Gustav Jenner

Focused specifically on Brahms (in chronological order):

‘Johannes Brahms als Mensch, Lehrer und Künstler: Studien und Erlebnisse’. Die Musik 2–3 (1902–1903), 171–98, 389–403.

Johannes Brahms als Mensch, Lehrer und Künstler. Marburg, 1905.

[Reprinted in English translation by Susan Gillespie and Elisabeth Kästner in Brahms and His World, second edition, ed. Walter Frisch, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 381–423.]

‘Unvollendeter Kanon von Johannes Brahms’. In Max Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms II/1, 275–80. Berlin: Deutsche Brahms-Gesellschaft, 1908. (pp. 278–84 in 3rd printing, published in 1912.)

[Discussion and edition of ‘O wie sanft’, Brahms’s unfinished canon for four women’s voices, WoO posth. 26]

‘Zur Entstehung des D-moll Klavierkonzertes Op. 15 von Johannes Brahms’. Die Musik 12 (1912–13), 32–7.

[Deals mainly with the compositional history of this concerto]

‘War Marxsen der rechte Lehrer für Brahms?’ Die Musik 12/2 (1912–13), 77–83.

Other musical topics (in chronological order):

‘Beethovens Testament vom Jahre 1802 und seine Eroica-Symphonie’. Dürrs Deutsche Bibliothek 16 (1904), 149–54.

‘Georg Friedrich Händel und Johann Sebastian Bach: Eine Antithese’. Dürrs Deutsche Bibliothek 16 (1904), 143–9.

‘Zur Aufführung der Missa Solemnis von Beethoven’. Oberhessische Zietung (Marburg), 12 February 1907.

‘Unser Gesangprinzip. Rede gehalten auf dem Konvent des S. G. V. Fridericiana Marburg’. Kartell-Zeitung: Offizielles Organ des sondershäuler verbandes Deutscher Studenten-Gesangvereine, 22 November 1912, 184–5.

‘Johann Sebastian Bachs Weihnachstoratorium: Ein Vortrag vor der Aufführung des Werkes in Marburg am 17 Dezember 1911’. Die Christliche Welt: Evangelisches Gemeindeblatt für gebildete aller Stände (Marburg), 12 December 1912, 1186–95.

‘Horatii Carmen Saeculare ad Apolinem et Dianam’. Berliner Philologische Wochenschrift, 29 April 1916, 559–63.

[Review of a 1915 edition of Carl Loewe’s 1845 choral setting of Horace’s Carmen saeculare]

‘Betrachtungen über Programmusik’. Hannoversche Schulzeitung, 24 April 1917, 149–50; 1 May 1917, 159–60; 8 May 1917, 169–71; 15 May 1917, 179–80; and 22 May 1917, 185–7.

[Essay published in several instalments]

APPENDIX 2

Selected Recordings of Jenner Works

Recordings of Jenner’s music appear primarily on small European labels, performed by musicians whose names will be unfamiliar to many in the United States. I include only a sampling here.

Brahms, Johannes. Ein deutsches Requiem, Op. 45. Hersfelder Festspielchor. Jubilate JU 85–197/8. Two 33 1/3 rpm discs. 1987.

[Includes Jenner’s ‘symphonic fragment’.]

Brahms, Johannes et al., Brahms and His Friends. Vol. 1: Cello Sonatas. Peter Hörr and Saiko Sasaki. Divox CDX 29106. Compact disc. 1993.

[Includes Jenner’s D-Major Cello Sonata. Work of Heinrich von Herzogenberg is also included.]

Brahms, Johannes et al., Brahms and His Friends. Vol. 7: Complete Sonatas for Violin and Piano. Rainer Schmidt and Saiko Sasaki. Divox CDX 29806. Compact Disc. 2001.

[Includes Jenner’s violin sonatas]

Hindemith, Paul and Gustav Jenner. Paul Hindemith: Konzert für Violoncello und Orchester Es-Dur, Op. 3; Gustav Jenner: Serenade für Orchester A-Dur. Angelica May and the Orchester des Staatstheatres Kassel, conducted by James Lockhart. Musicaphon BM 30 SL 1711/12. Two 33 1/3 rpm discs. 1977.

Jenner, Gustav. Chamber Music. Martin Litschgi, Nadja Helble and Iryna Krasnovska. MDG Scene 603 1343–2. Compact disc. 2005.

[Includes two of Jenner’s more frequently recorded works, the E-flat major Trio for Clarinet, Horn and Piano and the Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 5]

Jenner, Gustav. Complete Chamber Works. The Mozart Piano Quartet and friends. Classic Production Cpo 999 699–2. Two compact discs. 2002.

Jenner, Gustav. Klavierwerke. Christoph Öhm-Kühnle. Cornetto COR 10017. Compact disc. 2003.

Orgelmusik aus Norddeutschland. Wolfgang Stockmeier. Gema 15988–2. Compact disc. 199-.

[Includes four organ chorales of Jenner]

Romantische Chormusik. Marburger Bachchor. Thorofon Capella CTH 2054. Compact disc. 1988.

[Includes Jenner’s Twelve Quartets for Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass with Piano]