Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 April 2005

“I can resist everything except temptation.”

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). Lady Windermere's Fan, act 1 (1893).

In October 2000, Bob Freedom retired as the head of the Division of Cardiology at the Hospital for Sick Children, having served 3 five-year terms (Figs 1, 2). He had succeeded the late Richard D Rowe in 1986, carrying forward a tradition of clinical and academic excellence fostered by John Keith, the first head of the division. Bob joined the staff at Sick Kids in July 1974, when Dick Rowe, who had just become the head of cardiology in Toronto, enticed him to leave Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he was the director of the pediatric diagnostic cardiovascular laboratory, and developed the cardiovascular pathology registry. Just prior to moving to Toronto, Dick himself had been the director of the unit of pediatric cardiology at Johns Hopkins, having succeeded Helen Taussig, and recognized early on that Bob was far from the average young paediatric cardiologist just out from training. Indeed, Bob had already published 20 peer-reviewed papers, spanning topics from angiography and clinical outcomes to anatomy. In 1974, he had authored 2 landmark papers on pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum,1, 2 a lesion which would form the basis of a lifelong study, culminating in the appearance of a monograph that remains today the authoritative work on the subject.3

Figure 1. Robert Freedom photographed at the time of his retirement from the Hospital for Sick Children.

Figure 2. Some of Bob's closest colleagues photographed with him at the occasion arranged by the Hospital for Sick Children to celebrate his retirement in 2001. Left to right: David Nykanen, Gordon Culham, Robert, Lee Benson, Shi-Joon Yoo, and Haverj Mikailian.

An idea of his impact on the unit during his time in Toronto can be gauged by the memories of George Trusler, his long-standing colleague in paediatric cardiac surgery. George writes:

“Bob Freedom was a tremendous asset to both cardiology and cardiac surgery. He was a combination of many talents: a brilliant clinician and morphologist, an accomplished speaker, a prolific writer and a prodigious worker. He was in the forefront in studies of cardiac morphology and his wise counsel and superb teaching were of immense value to us as surgeons. He had a remarkable memory and his knowledge of the literature, both medical and surgical, was truly encyclopaedic. Frequently, to contribute to a discussion, he would refer to a paper, often in the surgical literature, and a quote the authors, the journal and even the date of publication as well as the salient content.

Like his predecessors, John Keith and Dick Rowe, Bob was surgically oriented, encouraging advances in surgical methods and often making suggestions to improve operations. The surgeon's friend, he was always supportive and always available to come to the operating room for consultation regarding some unexpected anatomy and its treatment. It was always a pleasure to be with Bob, but particularly at international meetings it was rewarding to see how highly he was regarded and note the recognition it brought to our hospital and city. I consider my association and friendship with Bob Freedom a special highlight of my experience at the Hospital for Sick Children.”

We share these sentiments with regard to association and friendship, not only within the Hospital for Sick Children, but from afar. To return to the beginning, one of us (LNB) had just begun his paediatric residency when, in the second month, he chose to undertake an elective of one month with Gordon Culham who, with Fred Moes, were the 2 cardiac radiologists at the hospital. As such, he followed Gordon around, and attended the now famous morning catheter conferences during which the angiograms taken the previous day were reviewed, the studies for the day presented, and new cases were discussed. Many a fellow has trembled with fright at those presentations, and at the questions asked by the staff, with Bob appearing the most intimidating, but the best to draw out the clinical issues. It was there, in early August 1974, that Dick introduced Bob to the division. Little did the one of us know then that he too, would become a paediatric cardiologist, or that the rather large, heavily bearded, figure to whom he was introduced that day would be his mentor, teacher, colleague, and friend.

Robert Freedom was born February 27, 1941, in Baltimore, Maryland. He moved with his fraternal twin brother, Gary, to Southern California in 1947, where they were raised in Ojai, California for a number of years, completing the early part of their schooling there. Their parents had been divorced shortly after he and his brother were born, and subsequently they had virtually no contact with their father and little contact with their mother. After high school in Beverly Hills, Bob attended the University of California at Los Angeles, completing a course leading to the award of Batchelor of Arts, in which he graduated with honours in 1963. He then attended Medical School, at University of California in Los Angeles, taking a post-sophomore year in pathology. This year, at least to that point, was one of the most exciting times of his life. He had committed himself to the post-sophomore year because he had an interest in neurosurgery. During this time, however, he quickly changed from neuropathology to the study of congenitally malformed hearts. During the year, he was mentored by Arthur Moss, Forrest Adams, George Emmannoulides, and Herbert Ruttenberg, amongst others. Long before he completed this wonderful and stimulating year, he had decided to become a paediatric cardiologist. Before finishing medical school, therefore, he arranged to spend an elective at the Children's Hospital in Boston, studying with Richard and Stella Van Praagh. Having returned to Los Angeles, and graduating from medical school “summa cum laude”, and being accepted in Alpha Omega Alpha, he was accepted for an internship and residency in paediatrics at the Children's Hospital in Boston. Having completed his training in paediatrics, he continued training in paediatric cardiology there, under the guidance of Alexander S. Nadas. Emerging from Boston as a paediatric cardiologist, he was recruited in 1972 by Richard Rowe, then director of the division of paediatric cardiology at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, becoming the director of the diagnostic cardiac catheterization laboratory and being appointed assistant professor of paediatrics at Johns Hopkins. He enjoyed his stay in Baltimore, but when Dick Rowe was recruited to succeed John Keith as director of the division of cardiology at The Toronto Hospital for Sick Children in 1973, Dick asked him to join him in Toronto. Moving to Toronto in the summer of 1974, the rest of his career was dedicated to the Hospital for Sick Children and the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto. Rising through the academic ranks, he was made Professor of Paediatrics in 1980, with later cross-appointments first as Professor of Pathology and then Diagnostic Imaging. He considered it a great privilege to be invited to succeed Dick Rowe (Fig. 3) as director of the division in 1985, stepping down from this position in the fall of 2000 because of serious health issues. His days at the Hospital for Sick Children were filled with patient care, teaching, administration and clinical research. His clinical research focused on the correlation of complex cardiac anatomy with angiography. This interest led to the publication of many peer-reviewed publications and textbooks, his choice of the best of these being listed in the bibliography.1, 3–19 He was honoured to represent the Hospital for Sick Children as an academic “ambassador”, lecturing abroad nearly 200 times. In May 2001, along with Bill Williams as surgical president, he was honoured to be the local medical president of the 3rd World Congress of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery held in Toronto (Fig. 4). Amongst many hospital administrative positions he filled, he was elected by his peers to be president of the Medical Staff, and was the first medical director of the Provincial (Ontario) Pediatric Cardiology Care Network. He was selected for 2 teaching awards while at the Hospital for Sick Children, earned the award given by the Council of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, and was elected to the Order of Ontario. It is difficult to assign priority to the many aspects of his years at the Hospital for Sick Children. Care of patients, recruiting and building the excellent staff of the division of cardiology, and devoting time to the education and mentoring of the numerous fellows in cardiology (Appendix) all warrant special mention. In the fall of 2000, he was granted sabbatical period of one year to write and edit “The Natural and Modified History of Congenital Heart Disease”.20 This large work was published in 2003, being the latest of his 8 textbooks. He resigned from the Hospital for Sick Children in December 2001, after a wonderful and rewarding career in paediatric cardiology, having worked at the hospital for nearly 3 decades. Despite retirement and poor health, he continues to contribute to the literature, with focused review articles and commentaries drawn on decades of clinical experience.21–23

Figure 3. A photograph taken in 1977 of Dick Rowe (left) presenting a demur Bob Freedom with an award from the staff of the catheter laboratory at the annual holiday party of the Division of Cardiology.

Figure 4. Robert photographed in conversation with his old friend Bill Friedman, from University of California in Los Angeles, at the Third World Congress of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery in Toronto, 2001.

Outside of the hospital Bob has many interests, including a passion for reading, and a life-long fascination with the trials and tribulations of Oscar Wilde. Underscoring this fascination, Bob was invited to the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology in Dublin, Ireland, in June of 1998, where he presented an overview of the life and times of Wilde and his effect on western thought, supported by his famous 2 slide carousel talk, all accomplished in 45 minutes! The flavour of the man is, perhaps, best conveyed by a recent interview.

Question: Could you speak a bit about your upbringing, your family, brother and schooling? What was your childhood like? What where your interests during your childhood?

Robert: “My father was a neurologist and my mother a lawyer. They were divorced when my fraternal twin brother, Gary, and I were 2 to 3 years of age. We were born in Baltimore, and my mother practised international law in Washington. After the Second World War, she decided to move to southern California. She told Gary and me that she required a year or so to study for the California bar exam, and that she could not take care of us during this time. We were placed in boarding schools, residential homes, and so on from about 1947 or 1948 until 1956. We hardly saw our mother during those years, just seeing her on an occasional weekend. At the end of 9th grade, we finally moved back to Los Angeles with our mother. The next several years were very difficult for me, at least in terms of my relationship with my mother. My mother never took the California bar, instead working as a legal secretary, and never remarried. I saw my father only once after I finished medical school, but he virtually never acknowledged Gary and me, neither during life nor in his death.”

Question: How did you choose University of California at Los Angeles?

Robert: “Living in Los Angeles, Gary and I both took a test, and we were allowed to attend Beverly Hills High school. The education there was superb, and during the last year of high school, I took courses at University of California at Los Angeles, and obtained my Bachelor of Arts degree, achieving the highest honours with a mixed major in zoology and anthropology. I was accepted by several medical schools and the decision eventuated to either Los Angeles or the University of Chicago. The scholarships and loans were better at Los Angeles, and thus I went to their medical school. I had little time for extracurricular activities, as I always worked after school and during the evening.”

Question: What are the influences in terms of mentors and opportunities that motivated your career?

Robert: “The medical school at Los Angeles had a program that offered the top 3 students a year or so of research between the second and third years, and was selected to take that year. At that time, I was interested in neurosurgery, and I was going to devote that year to study neuropathology. During the first part of the year, I was placed on a rotation with a total of 4 individuals performing autopsies. On this queue, the first 4 autopsies that I performed were on babies or children with congenital cardiac disease. This training was supervised by Harrison Latta, who was a wonderful teacher and mentor. The paediatric cardiologists at the University came to the autopsy room, and I demonstrated the findings. These cardiologists were Arthur Moss, Forrest Adams, Herbert Ruttenberg, Stan Goldberg, and George Emmanoulides. They all took an interest in me, and very quickly I gave up my aspiration in neuropathology to study congenital heart disease. I participated in the cardiac clinics and so on, and was mentored primarily by Arthur Moss, Herbert Ruttenberg, and George Emmanoulides. They were wonderful clinicians, and great and kind and inspiring teachers. I was so inspired by them that when I finished that year of research, I knew that I wanted to become a paediatric cardiologist. It was George Emmanoulides who suggested to me that I take an elective with Dick and Stella Van Praagh, and Alex Nadas, at the Children's Hospital in Boston. I believe it was in 1965 or 1966 that I drove an old battered car from Los Angeles to Boston to take this elective. The time I spent in Boston was one of the most exciting periods of my life, even as a medical student! Dick and Stella were wonderful teachers, and I absorbed so much cardiac pathology from them. I was also inspired by Dr Nadas, an incomparable clinician and teacher. In those years he seemed very stern, and his Hungarian accent was somewhat intimidating.”

Question: Why did you subsequently go to Boston Children's Hospital for your training in paediatrics and paediatric cardiology?

Robert: “I applied for a straight paediatric internship at Boston Children's, and I believe I was the first graduate of the medical school in Los Angeles to have matched there in paediatrics. I took my residency in paediatrics in Boston, applied for the fellowship in cardiology, and was accepted. In my year was Roberta Williams, now chair of paediatrics at the University of Southern California, and Mike Freed, who has remained on staff in Boston since his fellowship. One of my other peers was Charlie Phornputkul, who became dean of the medical school in Chiang Mai, Thailand. I saw Dr Nadas daily, and all of the trainees made rounds with him. He was a superb clinician, and teacher and organizer. He sought the very best from his staff and trainees. But also on the staff of the Department of Cardiology at the Children's Hospital were Donald Fyler, Amnon Rosenthal, and Curt Ellison. I was inspired and motivated by all three of these individuals. I was fortunate enough to have been assigned to the clinic of Dr Rosenthal, and it was there I learned about communications and timeliness, also learning the importance of these aspects from Dr Nadas. They all sought to train the consummate academic paediatric cardiologist. I was so privileged to receive the help from these mentors early in my career at Los Angeles, and then in Boston. Amnon Rosenthal was a wonderful role model, and I so valued his teaching, mentoring, and lifelong friendship. During my final year of training in Boston, the late Dick Rowe came to Boston as a visiting professor. He spent some time on the cardiac ward when I just happened to be the senior ward fellow. We had a great time together, and I was extremely impressed with him as a clinician, teacher, and as a kind and considerate person, almost like the father I never knew. Several months after he returned to Johns Hopkins, he called me, asking if I would like to join his staff in Baltimore as head of the diagnostic cardiac catheterization laboratory. The answer was an immediate YES! After several years in Baltimore, Dick called me to his office, and told me that he was going to leave Hopkins to assume the directorship at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, succeeding John Keith. I felt devastated, until he winked at me and smiled, and asked me to join him in Toronto. I accepted the position in December, 1973, and relocated to Toronto in August 1974.”

Question: You have had a many faceted career as pathologist, angiographer, clinician, and teacher. What has brought you the most satisfaction?

Robert: “As I reach this time of my life, and reflect on my academic career, virtually all components have provided me with great satisfaction and solace. The care of patients, and interaction with their families; education and research, especially the writing of papers and textbooks; and the interface with trainees, all these diverse aspects of an academic career have provided me with tremendous gratification. I am especially enamoured of the role in training role and my interface for nearly three decades with my fellows in the training programme (Appendix). I have been so fortunate to have interfaced with trainees from diverse parts of the world. What unites them all is a great desire to learn, and to assimilate the skills requisite for the contemporary paediatric cardiologist. It has been wonderful to watch the trainees “strut their stuff”! I believe strongly, indeed passionately, in academic renewal. Even before my health started to fail, I had made the decision to leave the Hospital for Sick Children after my 3rd term as head of the division of cardiology had been completed in June of 2001. One of the great rewards of recognition by your peers is the privilege of being invited virtually all over the world to speak at international meetings (Fig. 5), as invited professor, and so on. I found these experiences so rewarding, and the friends I have made in academic medicine so important.”

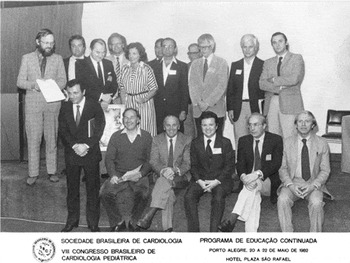

Figure 5. The photograph is illustrative of the faculties that gathered together throughout the World in the 1980s and 1990s to “spread the word” about the diagnosis and treatment of congenital cardiac malformations. In addition to Robert, who is second from the left on the back row, we see on the back row, from the left, Fergus Macartney, then Bob, Billy Kreutzer, Anton Becker, Jane Somerville, Benigno Soto, Valmir Fontes, the late Euryclidies Zerbini, the late John Kirklin, Rodolfo Neirotti, and Carlos Nojek. On the front row, from the left, Ivo Nesrallah, Bob Anderson, Lucio Parenzan, Fernando Lucchese, Francis Fontan and Michael Rigby.

Question: Your publications have focused primarily upon the anatomical substrate for complex congenital heart disorders. What do you consider your most significant contribution to the field?

Robert: “I take considerable pride in some of my publications.”1, 3–20

Bob's contributions are not only reflected in a series of publications or textbooks,1–23 although these have advanced our understanding of clinical paediatric cardiology and the management of complex heart lesions, improving the outcomes for thousands of children. His most significant and longest lasting contribution has been made in the very large numbers of fellows that have had the opportunity to work with him at the Hospital for Sick Children. They have come from every corner of the world, and are a living tribute to his care for children, dedication, and kind heart (Appendix).

As a teacher and mentor, Bob regarded the education of trainees in a most personal way, viewing their weaknesses as a personal failure, and no one took greater pride in their accomplishments. Bob has a photographic memory, and he encouraged everyone to read, and read a lot! Many a time, Bob would quote from a paper 10 or 15 years old, citing correctly the volume, the page number, and the number of patients in a table! A fellow would be assigned to check his references and few if any were wrong. Dick Rowe was always fascinated by the magnitude of his recall, commenting that, when Bob wrote a paper, there was little need for changes, and that the references were typically “right on”. Bob rarely needed the word processors so critical to our current generation of authors. He taught a philosophy that hard work and curiosity were the foundations of an exciting, rewarding, and stimulating career in paediatric cardiology.

As a colleague and mentor, Bob led by example. No one practiced a stricter work ethic, coming in to the hospital at 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning to write the first book on angiocardiography.17 He never discouraged ideas. Whenever we went astray, he always guided the fellows back on track. He viewed his colleagues as equals, and emphasized the importance of each contribution in the care of patients and in the future of paediatric cardiology.

Bob Freedom has a presence that is larger then life (Fig. 6), both physically and intellectually. To those who worked with him, attended his lectures, or just meet him briefly on his many trips, he was, and remains in retirement, supportive, a kind heart, and a unifying force bring together surgery and cardiology to the betterment of the care of patients. Robert has now translocated from Toronto to his retirement cottage in Granville Ferry, Nova Scotia. There, he remains in touch with his colleagues through e-mail, still performing as an outstanding referee and editorialist, and continuing to produce superb and encyclopaedic reviews of the cardiac lesions that retain his fascination.21–23 His achievements in this regard are the more amazing, since his health has been less than optimal since his retirement. His spirits, nonetheless, remain undaunted. We all hope that his retirement will prove to be a long one, and that we will all continue to benefit from his restless pen and tireless brain. We finish with a quotation from his favourite author and one that is equally apposite to the “big man” himself – “I put all my genius into my life; I put only my talent into my works.” (Oscar Wilde [1854–1900], Journal entry, June 29, 1913. Quoted in Journals 1889–1949, André Gide [1951]).

Figure 6. A photograph of Robert taken during one of his visits to London in the early 1990s, with a suitably proportioned crusty friend!

Fellows trained by Robert during his tenure as Head of the Division of Cardiology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto and their country of practice.

1986 Diane Alexander – Trinidad, Donald Arnold – Not known, Toshihiro Ino – Japan, Kazuyuki Koike – Japan (deceased), Michael Vogel – Germany, Lori West – Canada.

1987 Ian Adatia – United States of America, Fadley Alfadley – Saudi Arabia, Michael Guiffre – Canada, Robert Hamilton – Canada, Luba Komar – Canada.

1988 Michael Hofbeck – Germany, Martin Hoskings – Canada, John Smyth – Canada, Jan Sunnegardh – Sweden, Peter Wong – Canada.

1989 David Coleman – Australia, Elizabeth Galanter – Canada, Christine Houde – Canada, Silvana Molossi – United States of America, Evan Zahn – United States of America.

1990 Christine Boutin – Canada, Marc LeGras – United States of America, Valter Lima – Brasil, David Nykanen – United States of America, Charles Rohlicek – Canada, Abdul Samman – Saudi Arabia, Michael Schokking – Germany.

1991 Ruben Acherman – United States of America, Teiji Akagi – Japan, Urs Bauersfeld – Switzerland, Kit Yee Chan – Singapore, Hidemi Dodo – Japan, Felicia Figa – United States of America, Alberto Fin – Brasil, Mark Gelatt – United States of America, Theresa Stamato – United States of America.

1992 Andrew Davis – Australia, David Draper – Canada, Rami Fogelman – Israel, Alison Hayes – United Kingdom, Robert Justo – Australia, May Ling Wong – Phillipines.

1993 Maurice Beghetti – Switzerland, Frank Casey – United Kingdom, Gordon Gladman – United Kingdom, Isabel Haney – Canada, Alan Magee – United Kingdom.

1994 Tiscar Cavalle-Garrido – Canada, Quek Swee Chye – Phillipines, Yuk Law – United States of America, Anil Menon – Canada, Kazuhiko Shibuya – Japan, Roya Shaikholeslami – Canada, Anji Yetman – United States of America, Renato Vitiello – Italy.

1995 Mustafa Abdullah – Kuwait, Riyadh Abu-Sulaiman – United States of America, Carrie Fitzsimmons – Canada, Aijaz Hashmi – United States of America, Kyong-Jin Lee – Canada, Ru-Yan Ma – China, Grace Smith – United States of America, Jarupim Soongswang – Thailand, Roberto Tumberello – Italy, David Wax – United States of America.

1996 Shaul Baram – Israel, Jean-Luc Bigras – Canada, Robert Chen – Canada, Anne Dipchand – Canada, Luc Filippini – The Netherlands, Sean Godfrey – Canada, Joel Kirsh – Canada, Yasuki Maen – Japan, Shunji Nogi – Japan, Caroline Ovaert – Belgium, Kirk Zuffelt – Canada.

1997 Piers Daubeney – United Kingdom, Frank Dicke – United States of America, Umesh Dyamenallahi – United States of America, Thomas Gilljam – Sweden, Edgar Jaeggi – Canada, Henri Justino – United States of America, Peter Kuen – Switzerland, Lynne Nield – Canada, Jaan Pihkala – Finland, Lynn Straatman – Canada.

1998 Aline Botta – Brasil, Myriam Brassard – Canada, Simone Fontes-Pedra – Brasil, Tilman Humpl – Canada, Suzie Lee – Canada, Jane Lougheed – Canada, Carlos Pedra – Brasil, Jennifer Russell – Canada, Rekwan Sittiwangkul – Thailand, Björn Söderberg – Sweden, Andrew Warren – Canada.

1999 Rajesh Bagtharia – United Kingdom, Rejane Dillenburg – Canada, Gideon Du Marchie Sarvaas – The Netherlands, Fraser Golding – Canada, Stéphanie Levasseur – United States of America, Sharifah Mokhtar – Malaysia, Mataichi Ohkubo – Japan, Alejandro Peirone – Argentina, Shubhayan Sanatani – Canada, Min Seob Song – Korea.

2000 Shelby Ahamedkutty – United States of America, Kersten Åmark – Sweden, Catherine Barrea – Belgium, Rolf Bennhagen – Sweden, Vishwanath Bhat – India, Rui Chen – China, Mi-Jin Jung – Korea, Lillian Lai – Canada, Adriana Thomaz – Brasil, Kalyani Trivedi – United States of America, Emanuela Valsangiacomo – Switzerland.

*With members of the Division of Cardiology, The Hospital for Sick Children, The University of Toronto School of Medicine, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

A photograph taken in 1977 of Dick Rowe (left) presenting a demur Bob Freedom with an award from the staff of the catheter laboratory at the annual holiday party of the Division of Cardiology.

Robert photographed in conversation with his old friend Bill Friedman, from University of California in Los Angeles, at the Third World Congress of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery in Toronto, 2001.

The photograph is illustrative of the faculties that gathered together throughout the World in the 1980s and 1990s to “spread the word” about the diagnosis and treatment of congenital cardiac malformations. In addition to Robert, who is second from the left on the back row, we see on the back row, from the left, Fergus Macartney, then Bob, Billy Kreutzer, Anton Becker, Jane Somerville, Benigno Soto, Valmir Fontes, the late Euryclidies Zerbini, the late John Kirklin, Rodolfo Neirotti, and Carlos Nojek. On the front row, from the left, Ivo Nesrallah, Bob Anderson, Lucio Parenzan, Fernando Lucchese, Francis Fontan and Michael Rigby.

A photograph of Robert taken during one of his visits to London in the early 1990s, with a suitably proportioned crusty friend!