The life, work and thought of Sir William Jones (d.1794) have been extensively studied and discussed ever since his death and the publication of Lord Teignmouth's (d.1834) Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Correspondence of Sir William Jones and the 13- volume The Works of Sir William Jones, edited by his wife, Anna Maria Jones (née Shipley) (d.1829).Footnote 1 Scholarship on Jones has produced several detailed biographies and analyses of his contributions to the fields of linguistics, the study of Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit and Chinese, and the law, both in England and in India.Footnote 2 Practically speaking for an eighteenth-century judge in Bengal, in order to study such a diverse array of subjects, Jones required physical books. This simple fact has long gone under-acknowledged in discussions of Jones's scholarship.

In his letters, he describes from an early period in his life his desire to acquire a position in the Ottoman Empire or India where he might purchase manuscripts and have texts commissioned with his savings.Footnote 3 In a 1782 letter to Edmund Burke (d.1797), Jones laments his seemingly slim prospect of going to India to take up the judgeship in Bengal.Footnote 4 His sadness stems, largely, from this position being the “golden apple” for which he has seemingly spent many years of his life hopelessly striving.Footnote 5 Yet, despite the fact his letters show that he was very much thinking about the excellent salary he might obtain in India, Jones states that:Footnote 6

I was far from insinuating that gold is by any means my principal object, for I believe that the greatest part of my savings would be spent in purchasing oriental books and in rewarding … the translators and interpreters of them. I should remit part of my fortune in manuscripts instead of diamonds and my university [Oxford] would ultimately have the benefit of them.

Before his journey to India, Jones's letters reveal a man spellbound with the physical study of Arabic and Persian; his letters abound with rich details of manuscripts he either owns or has been able to consult in various libraries and collections, principally the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, his alma mater.Footnote 7 In this letter to Burke, Jones says that he intends for the Bodleian to see the fruit of his manuscript collection. Instead, in 1792 he transferred almost 200Footnote 8 manuscripts in Persian, Sanskrit, Arabic, Urdu and ChineseFootnote 9 to the library of the Royal Society, which then transferred the materials to the India Office Library in 1876.Footnote 10 This was not, however, the full extent of the collection. Jones retained 40 manuscripts (as well as an extensive book collection in European languages), which were then sold at auction in May 1831 and dispersed into different private collections.Footnote 11

In spite of the rich evidence of Jones's reading and scholarship found within his large manuscript collection, there has been a marked paucity of academic study focused on the physical manuscripts in his library. Gillian Evison's study of a small number of Sanskrit manuscripts in the Bodleian library is an important addition to the study of William Jones, providing an outline of how the manuscript collection can shed light on the life, thought and scholarship of the collector.Footnote 12 Beyond that, there are the two catalogues of Jones's manuscripts that are housed in the British Library, which provide some measure of information about the manuscripts, but neither catalogue focuses with any depth on Jones's use of these manuscripts or the methods by which he procured them.Footnote 13 Before these catalogues were written, Charles Wilkins, Jones's friend and fellow Sanskritist, had also drawn up a (very) rudimentary list of Jones's manuscript holdings. However, to date, there has been no study committed to a detailed analysis of Jones as a manuscript collector and the library collection he built beyond these catalogue lists, which themselves do not take into account any manuscript owned by Jones that once formed an integral part of his library but that are not found in the specific collections (RSPA and RST) in the British Library.Footnote 14

Much further work can, and indeed should, be done to situate Jones within his Indian intellectual milieu and to understand how Jones's reading of texts and the ideas that he formed from them, came from physical manuscripts he held between his hands and which had to be sought out, purchased and acquired. The materials and constraints of scholarship were very different in the 1780s and 90s from the modern day. Moreover, any understanding of the history of Arabic and Persian literature in the European scholarship of the time depended, to some extent, on which manuscripts had been available to and studied by previous generations of scholars, these being the resources a budding student of Arabic had at their disposal.Footnote 15 This article and its appendices provide only the most basic level of scholarship on Jones's manuscript collection and await future contributions, which may provide further codicological advancements on the physical manuscripts, as well as insights into Jones as a reader of the manuscripts he collected and the way the reading of the manuscripts he owned informed his scholarship.

Here, however, are the basic facts of how a man from England who wanted to acquire a collection of two hundred or so manuscripts did so. From whom did Jones procure his manuscripts? When did he acquire them? Can we trace the evolution of his scholarship through his manuscript acquisitions or use the manuscripts to advance our understanding of how Jones read the materials at hand and engaged with a literary text culture so different from his own? Upon which networks did he rely for manuscripts to be accessible to him in Kolkata in the 1780s and 90s? From where did these manuscripts come? Who had owned them before Jones, and can we trace the movement of these manuscripts over time?

Before India

The majority of Jones's manuscripts were acquired during his period working in Kolkata as a puisne judge for the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Bengal between 1783 and his death in 1794. Certainly, there were many more avenues for manuscript acquisition open to him in India, where he received books as gifts, bought and commissioned books, and acquired them through the connections and pilgrimage practices of members of his networks. It can fairly safely be stated that Jones came into possession of all his Sanskrit language material whilst in India, given his complete lack of knowledge of the language beforehand.Footnote 16 It has, however, been noted that Jones acquired certain manuscripts before India; for example, his Persian acquaintance Iʿtiṣām al-Dīn (d.circa.1215/1800) gave him one of the two copies of the Farhang-i Jahāngīrī found in his collections, this being BL MS RSPA 21.Footnote 17 Likewise, in his letters, he discusses whether or not he could acquire a copy of Jāmī's (d.898/1492) Yūsuf va Zulaykhā as early as 1771; he was clearly on the hunt for manuscripts from an early period of his career.Footnote 18

BL MS RSPA 107

One of the more unusual manuscripts in the Royal Society-British Library collection of Jones's manuscripts, Jones's copy of al-Mutanabbī's (d.354/965) dīwān (BL MS RSPA 107) was a gift from a man who signed off as ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg (fl.1188/1774), and who wrote the following inscription:Footnote 19

يصل الكتاب إلى بندر أقفرد ويتشرف بلثم أنامل الألحن الممجد حضرة وليام جونس

يَا رِياحَ العَاشِقينَ أَوْصِلْ مُحِبّينا السَلَامَ *** شابَهو الرَيحان وَالأزْهارَ شَماً فيِ الجِناَنْ

إِنْ وَصَلْتُمْ يَا نسِيم الحُبّ مِنَا قُلْ لَهُم *** يَا عَمِيدَ العِلْمِ كْن عَن كُلّ كَرْيِب في الأمانْ

فِي الفَصَاحَة كَالحَرِير في السَّخاوة حاتمٌ *** كَان هَذَا وِلِيام جُونس انَكليزان في العيان

من عند العبد الفقير عبد الرحمن بيك

This book is to arrive at the port of Oxford and is honoured to kiss the fingertips of the most intelligent and glorious Sir William Jones:

From your humble servant, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg.

Jones received the manuscript in 1774 by way of Middleton Howard (d.1791), an acquaintance of Jones, who had received the manuscript from Edward Wortley Montagu (d.1776), the son of the famous author Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (d.1762), in Venice.Footnote 21 In his letters, Jones mentions the manuscript twice, once in a letter to Howard, thanking him for the manuscript and telling him of the verses which he “could not read … without blushing”.Footnote 22 The second letter was sent to Henry Albert Schultens, one of Jones's favourite correspondents with whom he spoke at length about Arabic literature.Footnote 23 In this letter, Jones appended the verses, which he describes as “high-flown”, and acknowledges that the manuscript is “beautiful and very accurate”, but, he says, he fears he shall not have much time to read the poems, as he planned to leave the manuscript in Oxford in order to pursue his legal training and career in London.Footnote 24

Despite saying that he did not have the time to devote himself to Arabic literature in his letters, Jones did in fact read the manuscript at some point after receiving it. Enclosed within the manuscript, there is a large, folded up sheet of paper (Fig. 1) on which he has diligently written out the metre of the different poems in the dīwān in his characteristic, mechanical naskh script.

Jones, it would appear, was rather embarrassed about ʿAbd al-Raḥmān's note, blushing presumably because of the “exaggerated encomiums”, to use John Shore's translation from the Latin, with which ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg praised him.Footnote 26 He states in his note (Fig. 2), dated 3 October 1774, below the Arabic inscription on f.0r that he could “barely translate them without blushing”, again referencing a very physicalised performance of his embarrassment for the presumed future reader of the manuscript, distancing himself from the verses in question.Footnote 27 In any case, Jones's own translation has been lost to time. On the opposite verso side, there is the faintest trace of a capitalised ‘O’ from the ‘Oxford’ found in ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg's inscription (Fig. 2). The page appears torn, although it may be that the page was lost due to wear and tear. The binding, a fragile brown leather and board binding with gilded square decoration, is so fragile and worn that it has completely come away from the manuscript contents, rendering the textblock susceptible to damage.

Fig. 2. The poem of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg and, below, William Jones's translation. The O of Oxford is visible on the preceding torn-out verso side.

Source: British Library MS RSPA 107

Jones suggests ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg was likely one of Montagu's acquaintances from his travels to the Ottoman Empire and was probably someone with whom Montagu had spoken about Jones, given the reference to him by name in the final line of the poem.Footnote 28 ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg is, unfortunately, not easy to trace; the Ottoman administrative title Bey/Beg and the potential connection to Montagu suggest that he might have been a notable of some sort, although even that is hard to prove with any certainty. Where might ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg have lived and from where did the manuscript originate?

Based on previous ownership comments and the colophon, I would suggest that the manuscript originated in Hama, where ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg likely lived. The long colophon tells us that Sayyid Ḥusayn ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥamawī wrote the manuscript at the very beginning of Muḥarram in 1054ah/1644ad.Footnote 29 Whilst there is no indication that the manuscript was specifically written there, the name al-Ḥamawī (from Hama) suggests that it was. This is then supported by two important ownership notices, the first being appended to the colophon and the second being written on f.1r next to the short biographical notice about al-Mutanabbī. The first notice lists the owner as Sayyid Ḥusayn ibn al-Ḥājj ʿAlī al-Ḥaqq from the Awaj, a region near Hama, who acquired the manuscript in Muḥarram 1130/December 1717.Footnote 30 Following on from that, the second notice lists another owner connected to Hama, this being Muḥammad al-Bakrī al-Ḥamawī, the son of Muḥayyid ʿAlī, as the owner in Rabīʿ al-Awwal 1188/July 1769.Footnote 31 These dates provide us with some understanding of the life of the manuscript before it reached Jones. Likely produced in Hama, the manuscript remained there, probably until it reached the hands of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Beg, who does not record his acquisition of the manuscript, but who, given the proximity in dates between the final ownership statement and the date on which Jones received the manuscript, possibly acquired it directly from Muḥammad al-Bakrī al-Ḥamawī.

Unlike most of the books in this collection, this manuscript was an unexpected surprise for Jones. Not given by an acquaintance, the gift exchange also speaks to the emergence of European scholarship on Arabic (and, given Jones's own interest, Persian) literature and the awareness of this scholarship among Arabs and Arabic speakers in the Ottoman Empire, who thought it appropriate to send such students manuscript gifts. This manuscript, a dīwān of al-Mutanabbī, one of the most, if not the most, widely regarded and respected poets in the entirety of Arabic literary history and indeed a local of northern Syria, is perhaps reflective of what an Arab notable, a native of the area, might have thought a European would appreciate or would want or need to read in studying Arabic: that is, one of the greats.

Kitāb al-Ḥamāsah

Among the rest of the British Library collection, there is another manuscript of Arabic poetry which definitively originates from before Jones's journey to India. This manuscript, BL MS RSPA 117, is a copy of Abū Tammām's (d.231/845) Kitāb al-Ḥamāsah, the well-known collection of pre-Islamic and early Islamic poems. Now extremely fragile, the copy was traced from a much older copy of the Ḥamāsah that had been brought to Oxford from Aleppo by Edward Pococke (d.1691), the first Laudian Professor of Arabic at the University of Oxford.Footnote 32 MS RSPA 117 was traced for him, presumably by the “native of Aleppo” that he himself hired whilst at university to tutor him in Arabic, named Mīrzā.Footnote 33

This copy was then used by Jones whilst he was in India as the urtext for his commissioned version, this being BL MS RSPA 106.Footnote 34 Written for him by al-Ḥājj ʿAbd Allāh al-Makkī (fl.1206/1792), a native of the Hijaz, who was residing in India during Jones's sojourn in the nascent British administration, Jones notes (Fig. 3) on f.1v of that manuscript that:Footnote 35

This book was copied from a manuscript on transparent paper traced at Oxford on an inestimable copy of the Ḥamāsah which Pocock had brought from Aleppo and on which he set a high value. I gave ten guineas to the boy who traced it and I value this book at least at twenty guineas. W. Jones 26th Nov 1788.

This ownership note in BL MS RSPA 106 links the manuscripts (117 and 106) together and provides the chain of manuscript editions that resulted in the final, pristine copy that Jones clearly read extensively in his study of Arabic literature, given the vast quantity of marginal notes that show the metre of individual poems, provide translations of certain poems and, occasionally, biographical information about the poets in the anthology.Footnote 36 Equally, the manuscript note serves to link Jones indelibly into a line of scholars who procured manuscripts; like Pococke, Jones is suggesting, he also travelled afar to bring manuscripts back to England and he also deserves to be considered in this lineage of orientalist scholars. His manuscript note performatively ties him into this chain of scholarship.

Fig. 3. William Jones's manuscript note linking this manuscript to Pococke's manuscript.

Source: British Library MS RSPA 106.

Curiously enough, the delicate manuscript, BL MS RSPA 117, which is not available for viewing because of its fragility, appears to be mirrored by another manuscript, now found at the Bodleian Library, under the shelf mark MS Caps OR.b.13-14, purchased by the Hare brothers at the auction of Lady Jones's library along with the Sanskrit manuscripts discussed by Gillian Evison.Footnote 37 This is a further copy of the Ḥamāsah, the individual leaves of which were written on a dark brown paper and have been mounted on card for protection. This manuscript contains the following note on f.1r in the top corner: “I gave ten guineas for this MS, W. Jones”.Footnote 38 The listing of the guinea as the unit of currency is the indication on this manuscript that it was owned or acquired by Jones before India, as during his time in India he purchased books in the standard Indian unit of currency, the rupee, and noted as such.Footnote 39 This manuscript, listed by Evans in the auctioneer's catalogue as lot number 343, is a “curious” specimen, perhaps because of the quality of the dark paper or its pre-Bodleian bound (or, indeed, unbound) state.Footnote 40

Here we have an interesting problem in the collection: did Jones pay the exact same amount of money for two copies of the manuscript or does BL MS RSPA 117 represent a copy of a copy? That Jones owned three copies of the Ḥamāsah, on this count, is perhaps not surprising given the extent of his Arabic poetic and literary collections, of which very few specimens that he bought or acquired willingly include any Arabic poetry beyond the earliest period of Arabic literature. Likewise, for example, he owned several copies of the Muʿallaqāt and various different commentaries on them.Footnote 41 What is surprising about his collection, is that he should have two copies of the same manuscript, purchased for the same amount, both of which are on dark brown paper and come from the same period.

A further question that arises out of the separate existence of these two manuscripts is what their trajectories were within the collection. Jones clearly took BL MS RSPA 117 to India with him, as the manuscript returned to Great Britain in his consignment to the Royal Society, the core block of his library of Arabic and Persian language manuscripts. Bodleian MS Caps OR.b.13-14 may or may not have travelled to India, however. If the manuscript did not journey to India, we might ask where he kept it in England and why. If it did, we might wonder why Jones kept it with him after sending the manuscripts to the Royal Society. These questions are rather difficult to answer; it is likely that Jones kept a single copy of the manuscript because he still wanted to use it or read from it whilst in India after the consignment of his manuscripts were sent to Britain, especially given that he appreciated the Ḥamāsah enough to commission or purchase three separate copies of it, all of which bear reading marks. Jones, we can safely say, liked the text contained within the manuscript: but why choose this one to keep?

Here, just as with the translation of the note in BL MS RSPA 107 above and Jones's gloss of his reception of it, I would suggest we see evidence for Jones the librarian and curator thinking about the future users of the manuscripts. In his letter to Sir Joseph Banks (d.1820) attached to the now untraced Bill of Lading with which he sent his manuscripts to the Royal Society Library, Jones states that the manuscripts should “be lent out without difficulty to any studious men, who may apply for them”. This copy of the text, one of the two fairly poor-quality ones, is certainly not the one to send back to the Royal Society library, should one want a well-curated collection of accessible and useful manuscripts on good quality paper; if he were to keep one of the three, it is axiomatic that he would keep either BL MS RSPA 117 or Bodleian MS Caps OR.b.13-4.

Jones as student, copyist and translator

There are several manuscripts in the John Rylands library in Manchester that were also once owned by Jones, two of which were conclusively in his possession before his journey to India. These two manuscripts, a two-volume copy of Ibn Abī Ḥajalah's (d.776/1475) Sukkardān al-sulṭān and a copy of Saʿdī's (d.691/1292) Būstān, respectively lots 435 and 432* in Evans’ auction catalogue (see Appendix 3), were both, like the majority of Lady Jones's Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit language collection, bought by bookseller John George Cochrane (d.1852).Footnote 42 These manuscripts were subsequently owned by Samuel Hawtayne Lewin (d.1840) and then Nathaniel Bland (d.1865) and are now held respectively under shelf marks Arabic MS 264-5 [94-5] and Persian MS 240.

Jones was himself the copyist of the Sukkardān and notes this in his colophons and on the title page. On f.502r of the first volume, Jones notes, signing himself “G. Jonesius” in Latin, that he finished the first volume (by far the majority of the Arabic text) at Althorpe on 9 December 1766.Footnote 43 As for the second volume, Lord Teignmouth mentions Jones copying out a book about Egypt and the Nile which had been borrowed from Dr Alexander Russell (d.1768) in the summer of 1767.Footnote 44 The manuscript is almost completely translated, again by Jones, as a dual language reader with Arabic on the recto and English on the verso sides. This was part of a project Jones had for the Sukkardān; on f.ivr, Jones writes, “I may, perhaps, be induced, in my declining age, to amuse myself with printing the original of this curious work”. Indeed, this was not Jones's only copy of the Sukkardān and in BL MS RSPA 97, a small manuscript copy missing several folios, which previously belonged to an unidentified Muḥammad al-Birmāwī. Jones also wrote a note indicating his desire to publish the original, stating the manuscript was “for the press” (Fig. 4).Footnote 45

Fig. 4. Jones's note in BL MS RSPA 97, attesting his desire to publish the Sukkardān.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 97.

The two-volume Manchester manuscript is, however, much more than a copy of the Sukkardān; described in detail by Alphonse Mingana, the manuscript also includes Jones's “Keys of the Chinese Language”, various extracts in Persian, Arabic, Turkish and Sanskrit, as well as Jones's translation (in the second volume) of the Hitopadeśa, a collection of Sanskrit fables.Footnote 46 The inclusion of Sanskrit materials, and in particular his own translation of the Hitopadeśa, tells us that Jones took the manuscript with him to India, considering he did not begin learning the language until 1785.

As for the Būstān, it is a copy of Saʿdī's original complete with a Turkish-language translation and commentary of each verse. The manuscript is filled with notes by Sir William Jones and, perhaps most importantly for our purposes, has an ownership note that states that Jones owned the manuscript whilst a fellow at University College, suggesting he owned this manuscript before embarking on his legal career. The manuscript is one of a very small number of physical texts which suggest Jones's interest in Turkish, an area of scholarship that Jones did not particularly pursue.Footnote 47 The manuscript was copied by someone who calls themselves “Ibrāhīm Sarvalī” (ابراهيم سرولي) but if we compare the manuscript with Arabic MS 264-5 (94-5), which Jones affirmatively copied, I would suggest that this name is a falsified version of Jones's own name or merely an alias for him.Footnote 48 Michael Kerney more tentatively suggests that this manuscript was either written by Jones or someone employed by him, presumably because the manuscript includes notes in Jones's hand, and an autograph ownership note.Footnote 49 The “ugly” hand resembles closely Jones's own rough naskh script.

Why these manuscripts did not form part of the Royal Society collection is unclear, although it is likely because, as they were scripted by him, he did not consider them authentic editions to put into a library, or, perhaps more importantly, might not have wanted to lose the valuable intellectual property in his English translation of the Sukkardān, or the Turkish of the Būstān. Indeed, Jones had already come close to suffering intellectual property theft in 1770, when his manuscript of his Persian Grammar was almost poached from underneath him.Footnote 50

In India: purchases, gifts and networks

On his arrival in India, Jones set about procuring the vast majority of his Arabic and Persian language manuscript collection, principally those that reside now in the British Library under the Royal Society shelf marks (RSPA 1-118). There were three main methods by which Jones acquired manuscripts, these being purchasing, receiving gifts and commissioning manuscripts. All of these, in particular his receipt of gifts and his commissions, required a fairly sophisticated network of both British and Arab, Iranian and Indian colleagues and friends. The rest of this article will detail the acquisition of his manuscripts, where possible, and provide further cross-manuscript analysis of Jones's methods of collecting and curating his book collection. Furthermore, several manuscripts will be discussed in depth to illuminate the previous lives of the manuscripts and the hands through which they moved before they reached Jones, to add to the existing scholarship on manuscript culture in the centuries leading up to Jones's arrival in India.Footnote 51

The book market

Perhaps the simplest method of acquiring manuscripts was through purchasing them. In eight manuscripts in the collection, Jones lists the price paid and the date of purchase. On 4 November 1783, only two months after docking in India, Jones purchased six Persian manuscripts, all works of poetry, listed in Table 1:

Table 1. Manuscripts purchased on fourth November 1783 with price paid.

These books all came from the same auction. BL MS RSPA 56 and 57 were bought together in one lot, as Jones notes in his ownership note on f.1r of MS RSPA 56. Looking at the ownership records of these manuscripts, as well as other physical evidence, it is unclear where the books all came from, whether the auction was of one person's library or the libraries of several people. Of these manuscripts, there are some interesting past owners; BL MS RSPA 32, the copy of Niẓāmī's Makhzan al-Asrār, had previously been owned by Muḥammad Qulī Quṭb Shāh (d.1020/1612), one of the rulers of the Quṭb Shāhī dynasty based in Hyderabad (Fig. 5). Dating from 1609, the manuscript's transmission history between Muḥammad Qulī Quṭb Shāh and Jones is untraceable.

Fig. 5. Seal of Muḥammad Qulī Quṭb Shāh.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 32

Among the other manuscripts purchased, BL MS RSPA 29, the Dīvān of Anvarī (d.585/1189), had previously been owned by Thomas Ford (fl.1780), who dated his acquisition to 6 November 1779. Ford was the Persian interpreter for Colonel Grainger Muir (d.1786) of the East India Company; this tells us that the manuscript had been in British hands before the auction at which Jones bought the manuscript. The sixteenth-century manuscript also bears the seal of a Mīr Abū ʿAlī Khān Bahādur from 1172/1758-9, the date of which suggests he was possibly the owner previous to Ford. This person's seal is also present on a manuscript, now in the Eton College Library's Edward Pote (d.1832) Collection, Eton Pote 315, a copy of Amīr Khusraw's Qiṣṣah-’i Chahār Darvīsh.Footnote 54 This latter manuscript was gifted to Eton in 1788 by Pote, who largely acquired his manuscripts from Colonel Antoine-Louis Henri Polier (d.1795), who himself became one of Jones’s friends in India, before settling in France in 1788.Footnote 55 It is unclear exactly how Ford's manuscript ended up in the book market, but it does point to the market selling manuscripts which had been owned by both Indian and European owners beforehand. Unfortunately, Jones did not note his attendance at this auction either in his letters or his notebooks and so the setting is unknown.

Of the other manuscripts in the Jones collection, there were two further purchases which were listed inside the manuscripts, these being BL MS RSPA 31 and BL MS RSPA 51, Niẓāmī's Khamsah and the collected works (Kullīyāt) of ʿUrfī Shīrāzī (d.999/1591) respectively. The latter of these was purchased only eight days after the previous auction for 20 rupees. The manuscript bears no other evidence of Jones's use or reading, although he did have two other manuscripts which included a lot of material by ʿUrfī, suggesting Jones liked the poet (BL MS RSPA 54 and BL MS RSPA 55).

As for BL MS RSPA 31, this is one of two copies of the Khamsah that Jones owned. The other, BL MS RSPA 30, includes a note dated 1790 in Krishnagar, West Bengal, a spot north of Kolkata that the Joneses frequented to escape the city.Footnote 56 Unfortunately, there are no physical indications of how this manuscript wound up in Jones's possession. BL MS RSPA 31, on the other hand, was purchased in April 1788; it is one of Jones's most valuable and beautiful manuscripts, containing 18 miniature paintings, depicting scenes from all five of the texts, although they are principally clustered in the Haft Paykar, Niẓāmī's romantic epic depicting Bahrām Gūr (d.438) and seven princesses who tell seven tales. This particular epic poem also bears the most marginal comments, these ranging from linguistic points to descriptions of the plot, as well as the structure of the narrative. These annotations are too numerous to discuss here and warrant a detailed study to understand Jones's reading practices and engagement with the text. According to two separate ownership statements, the manuscript had previously been owned by a Mīr Muḥammad Bāqir (Fig. 6), who unfortunately did not date the ownership notes, meaning it is difficult to work out exactly which Mīr Muḥammad Bāqir he was.Footnote 57

Fig. 6. Title page and ownership notes on Sir William Jones's copy of Niẓāmī's Khamsah.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 31

The manuscript notes made by Jones reveal further aspects about his acquisition of manuscripts and practices of collection and ownership, as well as his understanding of Persian literary history. On f.1r, (Fig. 6) Jones comments, “I bought this fine copy of Niẓāmī for 100 S.R. the seller having at first demanded 200. 11 April, 1788 W Jones”, and, in Persian, “مالک این کتاب سر ولیام یونس یکی از حاکمان عدالت عالیه پادشاهی در شهر کلکته قیمتش صد روپیه.”. His Persian translates to, “the owner of this book is Sir William Jones, one of the judges of the Imperial High Court in Kolkata, its price being one hundred rupees”.

The two ownership statements are, therefore, somewhat different. Whilst Jones lists the price in both, only in the English statement does he acknowledge having negotiated the seller down to a 50 percent reduction. That the book cost 100 rupees is of course indicative both of its high value, visible in the miniature paintings, and also that Jones was willing to spend large sums on acquiring valuable manuscripts, clearly appreciating the aesthetic and physical qualities of the manuscript, not just the contents of the material inside, especially as this was not his only copy of the Khamsah. Furthermore, the ownership statements tell us about his use of the material within different networks; why should Jones have included an ownership statement in Persian at all? Why did he introduce himself and state his official function in the Persian, as opposed to the English?

In the English introductory note, Jones focuses on the aspect of haggling at the book market, arguing the owner-seller of the manuscript down to half the price originally demanded. This note speaks to Jones's desire to impress upon his contemporaries, and future readers, his success in acquiring materials at good prices, highlighting both a linguistic ability to haggle and engage with local book sellers, as well as demonstrating a kind of pride at having bargained him down, winning the interaction, so to speak. In his Persian note, however, Jones invokes his official and structural positions of power (one of the judges of the high court), presumably to inform the reader who William Jones actually was, but also to impress upon the Persian-speaking reader of the note the position itself and his importance as holder of that position. He does not need to brag to the Persian-speaking reader of his acquisitional prowess at the book-market, for the power-relation expressed through haggling is only invoked to impress Jones's compatriots; rather, he produces his colonial authority, in a method like the seal's impression of ownership on a manuscript, through his ownership note, invoking the official rank of a British official in eighteenth-century Bengal.Footnote 58

The other important manuscript note in this manuscript is on f.411v; it is one example of a type of manuscript note made relatively frequently by Jones in his manuscripts, this being what I shall term the text/author-circle (see Fig. 7 for an example). In this particular version, Jones writes out the names Firdawsī (d.411/1020) – Mavlavī [Rūmī] (d.672/1273) - Saʿdī – Anvarī (d.585/1189) – Ḥāfiẓ (d.792/1390) – Niẓāmī in a sort of circle, with no other obvious indication as to why he has written them in that shape or grouped them together at all; what does group these authors together, of course, is that they are widely deemed to be the luminaries or classic authors of Persian literature. In other text/author-circles, he adds poets, and indeed, texts to this list; for example, in BL MS RSPA 40, the final volume of Jones's commissioned copy of the Mas̱navī of Rūmī, or in BL MS RSPA 61, a copy of Ḥusayn Vāʿiẓ Kāshifī's (d.910/1504-5) Anvār-i suhaylī (the circle which is shown in Fig. 7) there are other circles with more names in them.Footnote 59

Fig. 7. Sir William Jones's circular annotation of a selection of Persian authors and texts.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 61

These text/author-circles appear to be both a vignette of how Jones understands Persian literary history and also expressions of the process of collection. This is most obvious in BL MS RSPA 61, in which Jones notes, alongside the aforementioned poets, other poets, like ʿUrfī and Jāmī, as well as the text, the Ẓafarnāmah. Underneath this circle, he wrote that he possessed all of these, except for Firdawsī. Originally, the Ẓafarnāmah had also not been owned by Jones, but presumably upon receipt of BL MS RSPA 7 from Justice Hyde in 1792, he crossed this note out. Here again, we can see Jones acting like a librarian, diligently taking notes of his collection, assessing what he wants to acquire and also returning to these notes to take stock of his collection moving forward. This is a way of curating a collection and provides textual, codicological evidence of Jones’s intentions to expand his collection in certain ways, in particular following the trends of what is deemed to be the chief texts of Persian literature. Furthermore, it tells us that he did not own a copy of Firdawsī's Shāhnāmah until some time after 1792, otherwise he would have crossed this out as well.

We find a further example of his curatorial intentions in his copy of the Rāg Darpan, BL MS RSPA 71 (Fig. 8).Footnote 60 This time, Jones writes, “To complete the collection of Tracts on Musick: Shemsu'laswat / Sengit Derpent (both from Lac'hnau) / Alshafa of Abu Ali Sina [sic]”. Two of these texts he did eventually buy, being the Shams al-aṣwāt, held under shelf mark BL MS RSPA 70, and a portion of Ibn Sīnā's (d.428/1037) al-Shifāʾ BL MS RSPA 114. Again, here we see Jones as librarian and scholar, actively looking out, as evident in his note about the texts being accessible in Lucknow, for chances to acquire what he understands to be the best texts for a scholar to obtain on a particular subject.

Fig. 8. Sir William Jones's list of musical texts that he hopes to acquire.

Source: British Library MS RSPA 71

This list of texts is also found in his notebook, now housed at the Beinecke Library at Yale University. Jones here lists these texts, alongside another entitled Mirʾāt-i Naghmah, with notes about their translation from Sanskrit, as well as the note, “4 books on music in Shanscrit [sic] at Lucknow?”Footnote 61 After this note, he also writes that the Tuḥfat al-Hind (BL MS RSPA 78) set out the systems of Indian music during the reign of ʿĀlamgīr (r. 1658-1707). As for the Sangīt, Jones notes that it was an “ancient book on music in Shanscrit [sic]” which has been translated into Persian by Ras Baras (fl.1697); later in his notebook, Jones explicitly says that the Shams was a translation of Sangīt Darpan.Footnote 62 However, Shams al-aṣwāt was a translation (and expansion and commentary) of Saṅgītaratnākara by Śārṅgadeva (d.1247), whilst the Sangīt Darpan was a different text authored by Dāmodara (fl.1625).Footnote 63 Among his Sanskrit manuscripts, Jones owned a different musicological work, Saṅgītanārāyaṇa (BL MS RST 16) but it would appear he did not own a copy of Dāmodara's Sangīt Darpan, either in Sanskrit or Persian, or at least this manuscript did not make it into either Wilkins’s rudimentary list of Royal Society manuscripts or Evans’s auction catalogue.

These manuscript notes highlight the limitations of his knowledge of Sanskrit musical works and the history of Indian music, a subject of study about which he became increasingly interested during his time in India, as is evident from the vast number of manuscript notes on the Tuḥfat al-Hind. Furthermore, whilst these notes highlight Jones the librarian and curator who was actively seeking ways to collect manuscripts, here in Lucknow from an undisclosed source, they also underline the necessary limitations of the time on his pursuit of study, namely his limited access to physical manuscripts, which he might use to better inform himself about the field of study at hand.

A European network of collection

There were many well-known collectors of manuscripts that travelled to Asia and brought manuscripts back to Europe to study. These manuscripts now fill the stacks of libraries all over Europe; I have already mentioned several such figures, like Antoine-Louis Henri Polier, Edward Pote and the Russell brothers. Jones's manuscript copies also attest to a lively trade among Europeans, particularly British officials of the East India Company, from within India. Manuscripts were traded as gifts or they were loaned or sent as study materials. There were several men among Jones’s European network whose books were transferred into his personal ownership (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Manuscripts gifted by European acquaintances with the date, if known.

To this we can probably add the following two manuscripts:

Table 2.2. Manuscripts possibly gifted to Jones from his acquaintances.

BL MS RSPA 28, a copy of the version of the epic poem Yūsuf va Zulaykhā attributed to Firdawsī, still bears the just visible traces of previous ownership.Footnote 64 On f.1r, there is a heavily erased seal, which is no longer visible, as well as the autograph of John Shore, also scribbled out. John Shore, the first Baron Teignmouth, and, after 1792, Governor-General of India, was a very intimate acquaintance and later wrote Jones's memoirs. Why his name should be crossed out so strikingly is unclear, especially as his name was not, in fact, crossed out in BL MS RSPA 99; in any case, it is likely the manuscript passed directly between the two men, given two other manuscripts in the Jones collection were also gifted by him.

As for BL MS RSPA 109, it is one of several miscellanies in the Jones collection that are difficult to classify. This one is a collection of Arabic and Turkish love poems, but also includes pages of what appear to be handwriting practice and a number of folios dedicated to glyphs of numbers of more than one digit. The reason why this is a possible gift from John Carnac is that there is a note (Fig. 9) on f.91 which lists the “Eastern Manuscripts of Gen. J. Carnac”. Carnac lived in Mumbai on India's west coast by the time Jones arrived in India, having served for a long time in the army of the East India Company, accompanying Robert Clive to his famous negotiations with Shujāʿ al-Dawlah (d.1188/1775) and Shāh ʿĀlam II (d.1221-1806). Was this manuscript a gift from Carnac? There is every chance of this possibility, as Carnac, like Jones, was a member of the Asiatick Society and is recorded by Jones as transferring six ancient plates he had come across in the area around Mumbai to the Society in 1787.Footnote 65 Equally, the manuscript might have been transferred to Jones's possession in the 1760s, as Carnac was a noted acquaintance of Jones at this time in England.Footnote 66 We cannot prove this, as there is no firm corroborating evidence. However, the existence of the note in this manuscript indicates that Carnac at some stage came into contact with the manuscript and its owner, who used its sheets to detail the manuscripts in Carnac's library. Moreover, the list was clearly written after the manuscript was assembled, as the list is written very specifically within the small margins of the paper.

Fig. 9. A list of the Eastern manuscripts in General John Carnac's library.

Source: British Library MS RSPA 109

Of the definite gifts, some are clearly from close associates of Jones, like John Shore. Francis Gladwin, a long-time acquaintance and co-founding member of the Asiatick Society, was, like Jones, a translator of Persian works, most famously the Gulistān of Saʿdī. Gladwin lent Jones two manuscripts; the first manuscript was his copy of Jāmī's Dīvān, which he gave to Jones only a day after Jones bulk-bought several manuscripts at the aforementioned auction. This period, late 1783, was, in all senses, an intense period of manuscript collection for Jones, as he bought, commissioned and received manuscripts, only two months after alighting in India. Later, Gladwin sent Jones a letter (Fig. 10), now appended into BL MS RSPA 14, in which he gifts Jones the manuscript in question, deeming it “worthy” of his acceptance, and asks Jones if he can tell the Library (presumably the one of the Asiatick Society) to put Jones down for a copy of Gladwin's forthcoming publication of the Asiatick Miscellany (published in 1785-6), narrowing down the timeframe for this gift to before 1785. This manuscript is a miscellaneous collection of short extracts from other texts, all scientific in nature.

Fig. 10. Letter from Francis Gladwin to Sir William Jones concerning the contents of the manuscript in which it is appended.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 14

Among the other manuscripts, Gladwin also appears in BL MS RSPA 13. Ghulām Ḥusayn Ṭabāṭabāʾī (d.circa.1230/1815), Jones notes, wrote this “Free history of the English in India as far as 1782”, and a manuscript copy of it was lent to him by John Shore.Footnote 67 Certainly, the manuscript must have been in Jones’s possession by 1788, for this is when he lent the manuscript to Gladwin, who wrote Jones another letter (Fig. 11), thanking him for some books and noting the return of this manuscript with his observation that the first section, the Muqaddimah, or Introduction, was “copied verbatim” from the Maʾās̱ir-i ʿĀlamgīrī. Jones also notes both his lending the manuscript to Gladwin on 8 March 1788 on f.1v, and also the fact of the introduction's having been supposedly copied from the previous text, according to Gladwin. In a note on f.0v, Jones notes (Fig. 12), “The first part of this book is copied verbatim, says Mr. Gladwin, from [blank] and the Masiri Alamgiri [sic]”.

Fig. 11. Francis Gladwin's note to Sir William Jones pointing out his observations regarding the manuscript.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 13

Fig. 12. Sir William Jones notes Gladwin's observations before the beginning of the textblock.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 13

That Jones recorded this transmission and kept the letter for posterity further speaks to his curatorial attitude towards his manuscript collection. That he notes having lent the manuscript is perhaps unsurprising; one would want to keep track of one's possessions, after all. However, the note about Gladwin's reading of the text resembles the process that I noted earlier in the discussion of his embarrassment about the praise poem in BL MS RSPA 107, wherein Jones guides the future readers of his manuscripts in how they read the text and how they see Jones, the collector. Here his eye is firmly kept on posterity, helping future readers of his manuscripts with pointers and bits of information to help stimulate the broader understanding of Persian historiographical literature from the Mughal period; in other words, Jones is telling the future reader who wrote what. The note works to safeguard the intellectual property of Muḥammad Sāqī Mustaʿidd Khān (d.1136/1723), the author of the Maʾās̱ir, whose work, according to Gladwin, has been cribbed; no future reader should assume that this first part was authored by Ghulām Ḥusayn Ṭabāṭabāʾī, then, but rather be aware of the mixed contents of the manuscript.

Among the other gifted manuscripts, there are those, such as Matthew Day's, the Revenue Chief in Dhaka,Footnote 68 gift of Mihr va Mushtarī, or John Hyde's, a fellow puisne judge, gift of the Ẓafarnāmah, about which we know very little before they were given to Jones. The only indication of previous ownership on the Ẓafarnāmah, for example, is a sales notice on f.106r that names ʿInāyat Allāh ibn Muḥibb ʿAlī as owner of the manuscript in the town of Thatta, now located in the province of Sindh in Pakistan, in the year 1077/1666-7, leaving quite a large gap in the manuscript transmission record and providing no indication of how John Hyde procured it.

By contrast, BL MS RSPA 85 and 86, a large two volume copy of the Hidāyah by al-Marghīnānī, one of the most authoritative textbooks of the Hanafi law code, has a fascinating history of ownership we can trace through the seal record. This was one of at least two copies of the Hidāyah in the Jones collection, the other being Evans lot 195, a printed and translated book.Footnote 69 This two-volume manuscript was acquired by Jones through Henry Vansittart, whose Persian-language seal (Fig. 13) is still visible on f.1r of BL MS RSPA 85. In his notebook, Jones lists the Hidāyah in one of several lists of books he wishes to acquire and notes at some later date above this that “Mr. Vansittart has a good copy”, which we might presume is this copy that Jones then acquired from him.Footnote 70 Vansittart was certainly in the practice of lending Jones reading material, as Jones notes that he lent him a copy of al-Farāʾiḍ al-Sirājīyah.Footnote 71

Fig. 13. The Islamic-style seal of Henry Vansittart.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 85

Vansittart was not the only important owner of this two-volume manuscript of the Hidāyah, bound in a beautiful red leather European-style Indian binding. Rather, this manuscript appears to have been one of a number in the Jones collection that had passed through the imperial Mughal library, or persons and institutions connected with imperial Indian dynasties.Footnote 72 On f.1r, there are seals from men at the courts of both Farrukh Siyar (d.1131/1719) and Bahādur Shāh (d.1124/1712). The seal from the official at the court of Farrukh Siyar (Fig. 14) was erroneously listed by Dennison Ross and Browne as having been that of Farrukh Siyar himself;Footnote 73 however, the seal belongs to someone bearing the name Sayyid [-?]d Khān at the court of Farrukh Siyar.

Fig. 14. Seal of an official at the court of Farrukh Siyar.

Source: British Library MS RSPA 85

Another such example of a manuscript in the collection coming from an imperial source is Jones's Kullīyāt-i Jāmī, BL MS RSPA 46, which includes a note (Fig. 15) from Francis Skelley, the Major of the 74th Regiment of the East India Company forces, whose name is also inscribed on f.1r, which reads:

The Fortress of Bangalor [sic] was stormed and taken by the British troops on the night of the 21st of March 1791—This book (found, the day following, in the palace of Tipoo Sultan [sic]) is respectfully presented to Sir William Jones by his obedient and humble servant Fra. Skelley Maj. 74th Regiment.

This is dated to 22 March 1791 and comes from the camp near Bangalore during the Third Anglo-Mysore War. Tīpū Sulṭān's (d.1213/1799) personal library was not transferred into British hands until 1801, after his death and the end of the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War.Footnote 74 This manuscript, which originated in his palace and now resides in the Jones collection, ought therefore also to be considered as a manuscript from among the library of Tīpū Sulṭān, albeit a manuscript that does not have the same provenance history when it comes to the transfer from Indian to English hands.

Fig. 15. Letter from Francis Skelley to William Jones appended into his manuscript copy of Kullīyāt-i Jāmī.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 46

Francis Skelley, the first Major of the Regiment, died in 1793, during the Regiment's operations against Mysore and Tīpū Sulṭān.Footnote 75 Except for this brief exchange, there is no historical record of Skelley and Jones having been acquaintances; this gift, just like BL MS RSPA 107, Jones's copy of al-Mutanabbī's Dīwān, was based, it would appear, upon scholastic fame. Of course, Jones was a very well-known mind of the late eighteenth century, in particular as regards Persian and Arabic scholarship, being the president and founder of the Asiatick Society and having already published several translations and commentaries on different aspects of Persian and Arabic literature and law. Skelley clearly thought of Jones as someone to whom this beautifully bound, large and extensive compendium of Jāmī's works would be of interest, which tells us that, beyond his fame as a scholar, Jones was also acknowledged as a collector of manuscripts, who might wish to receive manuscripts from across India and beyond.

Perhaps a further example of this renown for collecting manuscripts and books is the unusual acquisition of a manuscript by Jones in 1784, a gift from Francis Light (d.1794) the founder of the colony of Penang. Light had sent Jones a “rare Balinese religious document” according to Garland Cannon.Footnote 76 Written on tree bark, the manuscript was bought at auction by John George Cochrane as Evans lot 455 (see Appendix 3), listed as a Batta Manuscript from Sumatra. Unfortunately, I have been unable to trace the manuscript beyond this sale and so could not say whether the gift was intended for Jones or for the Asiatick Society. However, that Light considered Jones a worthy recipient of this gift in a language that Jones did not study at all highlights his renown as a collector of manuscripts, as someone building a library of manuscript curiosities, as well as acquiring manuscripts for personal scholarship.

BL MS RSPA 9: Reconstructing a manuscript history

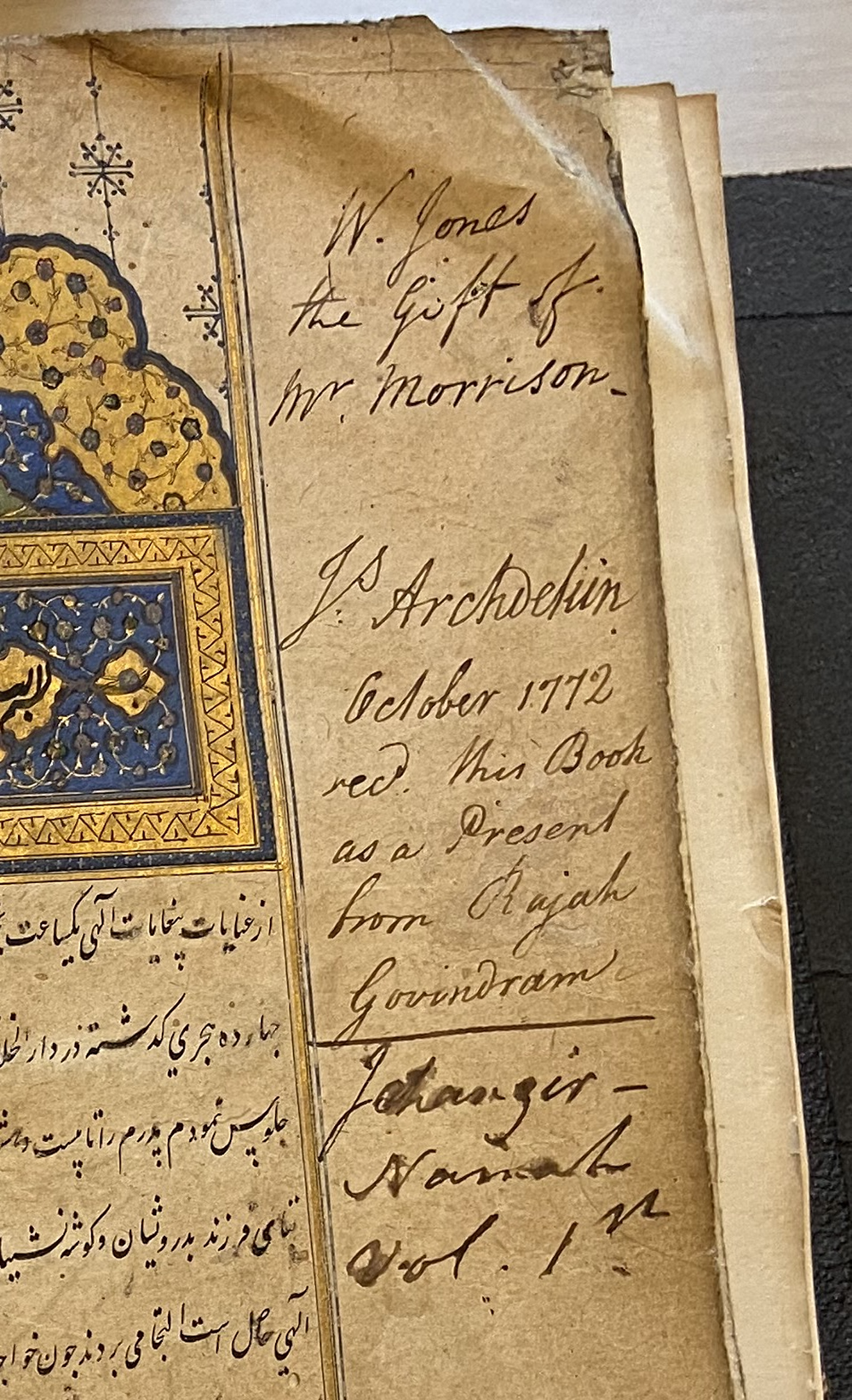

On BL MS RSPA 9, Jones’s copy of the Jahāngīrnāmah, there are two seals (Fig. 16), which bear the dates 1042 and 1045ah (1632-3 and 1635-6ad respectively) only five and eight years after Jahāngīr's (d.1037/1627) death.Footnote 77 Unfortunately, the majority of seals on this manuscript are now partially or wholly illegible.

Fig. 16. Page of seals on Sir William Jones's copy of the Jahāngīrnāmah.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 9

On f.262r, there is a seal and undated ownership note, both bearing the name Rājah Gūbind Rām Bahādur (d.1788) (Fig. 17); the ownership note states that he purchased the manuscript.Footnote 78 This must have been at some point before 1772, for on f.1v, there is a marginal note (Fig. 18) that explains that the same Rājah Gūbind Rām gifted the manuscript to a certain James Archedekin in October 1772. Archedekin is not a well-known figure; he was a salt merchant in Kolkata in the 1770s.Footnote 79 Presumably, the manuscript moved from Archedekin directly to this Mr. Morrison, for he is the one that gifted it to Jones at an undisclosed date. As for Rājah Gūbind Rām, he would later (in 1775) become the ambassador of the Nawāb Āṣaf al-Dawlah (d.1212/1797) of Awadh to the East India Company until his death.Footnote 80 He was a noted ally of the company and had warm relations with Warren Hastings.Footnote 81

Fig. 17. Seal and purchase note of Rājah Gubind Rām.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 9

Fig. 18. Ownership notes on Sir William Jones’s copy of the Jahāngīrnāmah.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 9

Mr Morrison could well be identified as Major John Morrison (d. after 1792), a poorly remembered figure of eighteenth-century Indian history, who came to London in 1773 to strike a bargain on behalf of Shāh ʿĀlam II, acting for him as his “plenipotentiary”.Footnote 82 Certainly, Morrison was acquainted with Jones, for Jones translated the “letter of credence” which was sent by Shāh ʿĀlam to the British government.Footnote 83 If that is the case, Morrison, who left India at the very end of 1772 would have had to have obtained the manuscript almost immediately from Archedekin before giving it to Jones, presumably before Jones travelled to India in 1783. It is worth emphasising in this reconstruction of a possible timeline for the manuscript's transmission between figures, that Jones (unusually) does not note the date of his accepting the gift, meaning that it is very possible that Jones did own the manuscript before his trip, as we have already shown he clearly owned a small collection of manuscripts by that point. Whether or not this timeline is exactly correct, the fact that Archedekin, a salt merchant otherwise seemingly unconnected to the world of scholarship and manuscript acquisition, received this manuscript “as a present” from Rājah Gūbind Rām in the first place speaks to the worth attached to manuscripts as a commodity to be traded as gifts. Why the manuscript was traded, possibly almost immediately, between Archedekin and Morrison is, however, unclear; perhaps Archedekin was not himself interested in manuscripts.

Important to note is that this manuscript may be one of a set, not all of which ended up in the Jones collection. Below Archedekin's note, there is another note, which states this is the first volume of the text; this explains why the manuscript ends “abruptly”, as noted by Dennison Ross and Browne.Footnote 84 As the manuscript contains about half the text, it might safely be assumed there is a second volume of the text that did not make it into Jones's possession. Perhaps it was never owned by Archedekin, or perhaps it was kept by him or by Morrison. Here again we have a further example of the types of limitations placed upon Jones's scholarship by the very physical constraints of working with partial and incomplete manuscript copies of texts.

Gifts to the Asiatick Society

Among Jones’s collection of materials, or rather materials which bear marks of having been used by Jones, there are two manuscripts that were originally gifts to the Asiatick Society, rather than gifts donated to Jones personally, which suggests that Skelley's gift was indeed to Jones as a book collector, rather than to Jones as President of the Asiatick Society. The first, Mīrzā Zayn al-Dīn's Dīvān, has been discussed in detail by James White.Footnote 85 This manuscript, now residing in the John Rylands Library as Persian MS 219, contains a manuscript note in Jones's handwriting that says that the manuscript was presented by the poet himself, who was, incidentally, a personal acquaintance of Jones, to the Governor-General, at the time John Macpherson, on 21 May 1785.Footnote 86

Of the manuscripts sold as part of the personal collection of Lady Jones in 1831 on the other hand, there is one that was actually a gift to the Asiatick Society, this time by Thomas Law (d.1834), himself a member of the “Club” listed by Jones in his notebook.Footnote 87 This manuscript, a copy of the medical encyclopaedia Ẕakhīrah-’i Khvārazmshāhī now listed as Persian MS 192 at the John Rylands library, was not, therefore, a gift to Jones per se. That this manuscript was included in the sale of Lady Jones's library might indicate that what were originally gifts to the Society that were in Jones's personal possession when he died were, perhaps erroneously, shipped back to England with his effects after his death.

This particular manuscript also bears an important testament to the auction of Jones's library, which is worth mentioning here. In this manuscript, and also in Persian MS 187, Jones's copy of Vaḥshī's (d.991/1583) Shīrīn va Farhād, there is a note by Samuel Hawtayne Lewin, whose manuscript collection was largely bought by Nathaniel Bland, and from Bland these two manuscripts wound their way into the John Rylands Collection.Footnote 88 Lewin's note states that he purchased the manuscript(s) in 1831 at the sale of Jones's library. However, in the ledger of sale, kept at the Royal Asiatic Society, the buyer is listed as John George Cochrane.Footnote 89 Cochrane was a bookseller by trade, and later the first librarian of the London Library.Footnote 90 Cochrane must have acted here as a kind of intermediary. Either Cochrane was purchasing the books which were immediately sold to Lewin, or, perhaps more likely given the wording of the manuscript note which suggests Lewin bought the manuscript directly from the auction, Cochrane was working on a commission from Lewin to purchase the manuscripts. This suggests that other manuscripts, listed as having been bought by him, may have been bought instead on commission for other collectors, rendering the task of tracking them down slightly more challenging.

Jones's Indian, Arab and Persian Network

As a puisne judge on the Bengal High Court, Jones was in contact with a vast number of Indian, and indeed Arab and Persian, functionaries of the legal system, namely pandits and mavlavīs, those men tasked with interpreting Islamic and Sanskrit legal sources for the judges.Footnote 91 Beyond this network of court officials, Jones also met and developed personal relationships with many men, about whom he writes notes in his notebook. Sometime it is hard to say for sure if the bare bones of the name given in a manuscript is exactly the same as the name given in his notebook; for example, Persian MS 267, Jones’s copy of Jāmī's Yūsuf va Zulaykhā, sold at the auction as Evans lot 434 (see Appendix 3), and now housed at the John Rylands library, was written by an ʿAbd al-Raḥīm.Footnote 92 This ʿAbd al-Raḥīm might tally with the ʿAbd al-Raḥīm in Jones’s notebook, recommended to him by a Mr G. Williamson.Footnote 93 Two of these men in his circle of acquaintances in particular were important for the transfer of physical copies of manuscripts from their personal collections to the Jones collection: ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān (d.circa.1208/1793-4) and Sayyid Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān (fl.1201/1786-7).

ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān is well known to historians of the East India Company's interactions with Indian officials.Footnote 94 ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān was, according to Jones, “chief magistrate at Benares [Varanasi] skilled in Persian, a good poet [whose takhalluṣ (pen-name) was] khalīl, author of a large work on the lives of the Persian poets from Bahram Gur to Hazein [sic]; a vast collection of 15 volumes in folio”, this being the Ṣuḥuf-i Ibrāhīm.Footnote 95 Later in his notebook, ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān is mentioned as being the host of Ghulām Ḥusayn, the author of Siyar al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn.Footnote 96 Beyond the notebook, Jones mentions ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān in his letters, telling Warren Hastings of a morning spent in his company, wherein his “manners and conversation gave me great pleasure”.Footnote 97

ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān gave Jones his copy of Tuḥfat al-Hind, an encyclopaedic work on Indian music in the time of ʿĀlamgīr, now under shelf mark BL MS RSPA 79. The manuscript bears his seal and then next to the seal on f.1r an ownership note that explicitly references ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān giving the manuscript to Jones in 1784. This book is presumably the manuscript that Jones mentions in his letter to Hastings, “which my ardent curiosity prompted me to run over”. The manuscript is of particular value among the Jones collection because on almost every page there are long annotations in Jones’s hand, attesting to this “ardent curiosity” with which he read the text. We might also presume that ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān gave Jones BL MS RSPA 80, usually entitled Forms of Oaths Held Binding by the Hindus. The manuscript is alleged to have been written by ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān and would have been an important tool in Jones's quest to find forms of oaths upon which (he believed) Hindus would swear and then tell the truth, something about which Jones speaks at length in his letters.Footnote 98

About Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān we know somewhat less; certainly, Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān does not appear to have held any official function in the Indian state apparatus, unlike ʿAlī Ibrāhīm Khān. There is a seal that appears on six manuscripts in the Jones collection (see Fig. 19), bearing the name “Sayyid Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān” in the year 1201ah, corresponding to 1786-7, therefore during Jones's time in India. These six manuscripts are as follows:

Fig. 19. Seal of Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān, Jones's personal acquaintance.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 19

Table 3. Manuscripts bearing the seal of Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān.

This is a varied collection of manuscripts; they date largely from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and cover a wide range of topics and authors. That all the manuscripts bear the same seal from within the time period that Jones lived in Calcutta and, given the personal connection between the two men attested in the notebook and discussed below, it seems likely that Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān collected the manuscripts for Jones, impressing his seal upon them in his role as middleman, or that he gave them to Jones from his personal collection at some point during or after 1786-7. Either way, just as with BL MS RSPA 21, gifted to him by Iʿtiṣām al-Dīn, the personal connection is unattested to by Jones in the manuscripts, notably unlike his modus operandi with the gifts he received from European contacts.

In Jones's notebooks, Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān plays a prominent role among his coterie of local friends and acquaintances, appearing several times. Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān was Jones's Persian munshī, working as his secretary; the son of Nādir Shāh's (d.1160/1747) physician, Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān was one of the first local informants that Jones had about Persian book culture in India.Footnote 99 In the notebook, Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān is also seen recommending men and books to Jones; he recommends, for example, ʿAbd al-ʿAlī and his son, Muḥammad Vāʿiẓ, to Jones for their work in law.Footnote 100 ʿAbd al-ʿAlī, a resident of Hooghly, was apparently “one of the first in India” on matters of divinity and law and “eminent in every branch” of learning.Footnote 101 Likewise, Muḥammad Arshad was recommended to Jones by Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān, because he was a “learned geometrician” who hailed from Delhi.Footnote 102 Jones's scholarship, just as his ability to seek out new contacts among the local Indian academic community, was dependent to a great extent on the operations of acquaintances like Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān, whose own networks and acquaintances are those ones that Jones was able to meet. As with manuscripts, Jones's knowledge of Indian learning was dependent on the limitations of his time and place, in this instance the extent of already existing networks of people engaging in Persian and Arabic literary culture in north-eastern India over an 11-year window.

Of the books that Aẓhar ʿAlī Khān recommended to Jones but did not give him personally, there is also a text Jones calls Ṣaḥīfah-’i Kāmilah, which he praises as “very eloquent” and which William Chambers (d.1793) supposedly owns; this title is later included in his list of “Arabick reading” in the notebook.Footnote 103 This Ṣaḥīfah-’i Kāmilah would appear to correspond to BL MS RSPA 112, Jones's copy of al-ʿĀmilī's (d.1030/1621) al-Kashkūl. Jones's title page of the manuscript reads, “Caschūl: an Arabick Miscellany by Bahaʾu 'ddin al-ʿAamil [sic]”;Footnote 104 on the same folio, Jones has written “al-Ṣaḥīfah al-Kāmilah” (Fig. 20) and underneath written, “An elegant moral work in Arabick”, suggesting this was a name by which Jones knew the text.Footnote 105 The notebooks further attest to Jones's regard for al-ʿĀmilī's work, for the author and his works come up more often than any other non-legal text or writer.Footnote 106

Fig. 20. Sir William Jones annotates his copy of al-ʿĀmilī's al-Kashkūl.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 112

In the same manuscript, he has also noted (Fig. 21) that, “The al-Mikhlāh, by the same author, [was] seen at Lucnow by Ahmed [sic]”.Footnote 107 This Aḥmad also appears in his notebooks, again as a mononym, as one of the 23 mavlavīs attached to the court.Footnote 108 Elsewhere in the notebook, there is also a note about a Muḥammad or Aḥmad mavlavī, of whose name Jones seems unsure, who is the brother of a Majd al-Dīn and who had been the preceptor to Ghāzī al-Dīn (Fīrūz Jang) (d.1165/1752), the son of Niẓām al-Mulk Āṣaf Jāh (d.1161/1748).Footnote 109 Just as with the notes in his notebook and manuscripts regarding the musical tracts he had heard about in Lucknow, here we see Jones noting within the manuscripts themselves the existence of works by the same author, their location and his contacts who have managed to view these manuscripts, possibly with a view to procuring them himself. We might also suggest that it was possibly the same Aḥmad who travelled to Lucknow that saw the musical tracts. This form of manuscript note, whilst uncommon in the Jones collection, does attest to the process of manuscript collection and acquisition and the requirements that the process necessitated, namely the awareness of where copies of each text existed. Furthermore, this type of note attests to both his reliance on his acquaintances and contacts, but perhaps more importantly the difficulty experienced by Jones in acquiring all the books he wanted and the very material limitations that prevented him from expanding his collection, here this being the physical lack of a manuscript copy of the text in the vicinity.

Fig. 21. Sir William Jones annotates his copy of al-ʿĀmilī's al-Kashkūl, noting where he can find al-ʿĀmilī's al-Mikhlāh.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 112

Mīr Ḥusaynī

There are two books in the Jones collection which, to some extent, stumped Dennison Ross and Browne when they were cataloguing.Footnote 110 These are BL MS RSPA 4 and BL MS RSPA 95, respectively entitled Farāyiz̤-i Muḥammadī and al-Maṭālib al-Ḥusaynī[yah];Footnote 111 the two manuscripts were both written on a rough woven paper in the same thick, inelegant nastaʿlīq hand. Al-Maṭālib al-Ḥusaynīyah was authored by Afāz̤ al-Dīn Muḥammad, known as Mīr Ḥusaynī, whilst the other, Farāyiz̤-i Muḥammadī, was authored by Muḥammad Vālī at the request of this same Mīr Ḥusaynī. Both tracts are named after Ḥusaynī and both deal with aspects of Islamic theology and law.

Farāyiz̤-i Muḥammadī, authored in 1193/1779, is a short treatise on Islamic laws of inheritance, a particular interest of Jones's scholarship in India, and is based on al-Farāʾiḍ al-Sirājīyah, a tract on the same subject by Sirāj al-Dīn al-Sajāvandī (d. circa. 600/1203) that was itself translated (and abridged considerably) into English by William Jones in 1792.Footnote 112 Interestingly enough, Jones's library does not include a copy of al-Sirājīyah, but rather three copies of al-Farāʾiḍ al-Sharīfīyah (BL MSs RSPA 1, 2 and 92) by Sayyid Sharīf al-Jurjānī; Jones obviously did have access to al-Farāʾiḍ al-Sirājīyah, and, as already mentioned, Henry Vansittart had a copy of it and lent it to Jones, as is noted in the notebook.Footnote 113 The other manuscript connected to Mīr Ḥusaynī, al-Maṭālib al-Ḥusaynīyah, dated 1199/1784-5, is a very short theological treatise composed of disquisitions (maṭālib) on five aspects of Shia theology, these being: the nature of the divine, the mission of the prophets, the imamate, burial and the Day of Resurrection. This is followed by a conclusion which discusses, among other things, the ten commandments.Footnote 114 Mīr Ḥusaynī's contributions to eighteenth-century Shia thought await further, critical study, as there has been no academic scholarship on either manuscript or text until this point.

Furthermore, this Mīr Ḥusaynī has long remained unidentified. However, on reading Jones's notebooks, there is a character who appears numerous times whom Jones identifies as Ḥusaynī. Could this be the same Ḥusaynī who authored or requested these texts to be authored? The mysterious mononym Ḥusaynī comes to Jones “highly recommended” by his Arabic secretary, al-Ḥājj ʿAbd Allāh al-Makkī.Footnote 115 Ḥusaynī himself recommends that Jones purchase copies of al-Fatāwā ‘l-ʿĀlamgīrīyah, the Sirājīyah and the Sharīfīyah.Footnote 116 Ḥusaynī also appears in the list of mavlavīs of the court.Footnote 117 Furthermore, in a list of “learned men of Calcutta”, Jones lists Ḥusaynī and notes his aptitude for mathematics, law and grammar.Footnote 118 Ḥusaynī was clearly an important and esteemed contact that Jones met with frequently and with whom he presumably discussed both practical matters of book collection (hence the recommendations) and the subject matter of inheritance and Islamic Law (hence the subject matter of the recommendation). Indeed, if Ḥusaynī “greatly” recommended the Sirājīyah and Sharīfīyah to Jones, it is interesting that, if we assume they are the same person, he also, at another time before Jones’s arrival, might have been responsible for having a book composed which is itself based on the Sirājīyah (BL MS RSPA 4).

At this point, we cannot make a positive identification of Ḥusaynī. Jones only identifies him as Ḥusaynī throughout his notebook and does not refer to him in his letters; moreover, Jones does not appear to have read or engaged (in any great detail) with the manuscripts, as they bear no traces of his typical types of marginal note. Complicating the matter somewhat, in the Catalogue Raisonné of the Buhar Library, the authors briefly mention a man called Muḥammad Afāz̤ al-Dīn al-Ḥasanī, who requested that his nephew, Sayyid Qāsim ʿAlī, write a tract on the correct reading of the Qur'an, entitled Ruqʿah-‘i Qārī in 1196/1781.Footnote 119 On the other hand, Brockelmann lists Muḥammad Afāz̤ al-Dīn al-Ḥusaynī, spelt as per Dennison Ross and Browne, and refers to Jones's copy of al-Maṭālib al-Husaynīyah (at the time under shelf mark Ind.Off. RB95) in the section on Indian Shia legal texts in his Supplement to the History of Arabic Literature, written around the same time as the Catalogue of Jones’s works was published.Footnote 120 The author's name is written in the introductory section in BL MS RSPA 95; the name (Fig. 22) is difficult to read for certain, not clearly Ḥasanī or Ḥusaynī.

Fig. 22. The name of the author of MS RSPA 95.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 95

It seems unlikely that there were two men in Bengal in the 1780s requesting Shia theological and legal texts be written with almost the same name down to one letter difference in Arabic script; it would seem more likely that one is a misreading. Following Brockelmann, Dennison Ross and Browne's use of Ḥusaynī, I would suggest that we ought to see these three works, including the one in the Buhar Library, as written by or for this one man, Mīr Ḥusaynī and that this Mīr Ḥusaynī, who flourished in Bengal in the 1770s and 80s, was possibly the Ḥusaynī mentioned in Jones's notebooks, meaning he would have acquired them probably through a personal connection. Given that these two legal and theological texts are totally unknown outside of the Jones collection, and that both manuscripts are of texts which are personally connected to the author and scholar, called in the manuscript Mīr Ḥusaynī, either being authored at his request or by him personally, and, crucially, that both manuscripts are written in the same handwriting, on the same paper, the manuscripts likely came to Jones together from the same source. Could this be the Ḥusaynī from the notebook? Were these manuscripts a personal gift from the scholar and author to Jones? Such a positive identification will, however, require further scholarship to advance our knowledge of this figure and his work.Footnote 121

Other Middlemen

Despite the availability of books at market and among his networks in India itself, Jones also appears to have acquired books from across the Hijaz, Iraq and maybe Iran. In his notebook, Jones makes two important notes regarding his collection practice and his reliance, to some extent, on the pilgrimage and trading practices of Muslim acquaintances, who travelled from India across to Iraq and the Hijaz.

ʿAbd al-Majīd, a merchant and native of Isfahan, is described in a list of his new acquaintances in India, all of whom Jones describes in varying terms, detailing either their profession, how he knows them or their proficiency in Arabic and Persian scholarship. For example, among his other acquaintances, there was a Majd al-Dīn, who has been in the service of Saʿadāt ʿAlī Khān II (d.1229/1814), the brother of Āṣaf al-Dawlah; Diyānat Allāh, “an old man of good character”; and indeed Mīrzā Zayn al-Dīn, “a poet who has written 100,000 couplets”.Footnote 122 ʿAbd al-Majīd was of importance to Jones not just because he was a merchant from Isfahan, but also because he was “going to Basra and Baghdad [and] will buy books for me”.Footnote 123 This note was added later, scrawled above the previous description of ʿAbd al-Majīd in a thinner pen than that used to write the name, telling us Jones wanted to note down the offer made to him to remind him of the potential source of manuscripts.

ʿAbd al-Majīd was, indeed, not the only local acquaintance to travel across swathes of territory, having offered to buy book for Jones. A man called Ḥājī Ghulām ʿAlī, the “preceptor” to Mubārak al-Dawlah (d.1208/1793), then the Nawāb of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, was staying with Mīrzā ʿAbd al-Raḥīm on 19 January 1784, who was one of Jones's acquaintances.Footnote 124 This Mīrzā ʿAbd al-Raḥīm Iṣfahānī had himself been “recommended” to Jones by none other than his acquaintance, ʿAbd al-Majīd.Footnote 125 The recommendation appears to have been for a position of some kind as a mavlavī on the High Court in Bengal, as Jones lists the recommendation among several others after having listed the actual mavlavīs by name.Footnote 126 Ḥājī Ghulām ʿAlī, otherwise it would seem unknown to Jones, offered to procure books for him on his way to Mecca and back again, where he was undertaking his second pilgrimage.Footnote 127

Whether or not these men actually did procure books for Jones is uncertain. Their seals and ownership notes do not appear in any of his manuscripts, nor does Jones note his receipt of manuscripts from these sources. However, as the vast majority of his manuscripts do not have a clear or explicitly referenced passage of ownership, and, perhaps more importantly, as Jones did not note his receipt of any manuscripts from non-Europeans, we might suggest that this was indeed one way in which he acquired manuscripts. Furthermore, the notes above attest to the interlocking nature of his networks in India and his reliance upon them for meeting people and acquiring books. Without ʿAbd al-Majīd there would have been no Mīrzā ʿAbd al-Raḥīm and without him, no Ḥājī Ghulām ʿAlī.

The Seal Record: Previous Owners of Note

Among the Jones collection at the British Library, there are several manuscripts which, although we cannot affirmatively trace Jones's acquisition of them, bear important or notable previous owners and are worthy of a brief discussion here.Footnote 128 Perhaps the most notable of the seals on any of the Jones collection are seals suggesting that BL MS RSPA 94, Jones's copy of Sharḥ ʿAqāʾid al-Nasafī, had previously belonged to a servant of Dārā Shikūh (d.1069/1659) (whose seal is visible in Fig. 23) and was transferred into the Mughal imperial library.Footnote 129 How Jones acquired the manuscript is unknown, but it certainly had passed through illustrious hands on its way to him.

Fig. 23. The seal of Dārā Shikūh's servant, [Muḥ]ammad M[ī?]l.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 94

BL MS RSPA 96, Jones’s copy of a part of al-Masʿūdī's (d.345/956) Murūj al-Dhahab also has an interesting manuscript history. This manuscript, with a beautiful double-page sarlawḥ which notes the scribe as ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sulaymān ibn ʿĪssā al-ʿAqrāwī, presumably from Akre in modern-day Iraqi Kurdistan, and dated to Ṣafar 1075/September 1664, was previously owned by the scholar Aḥmad ibn ʿĀmir al-Saʿdī al-Ḥaḍramī (Fig. 24) according to an ownership note on f.iir.Footnote 130 The manuscript then presumably travelled to India before Jones, as there is a seal from an otherwise unknown Qivām al-Dīn Khān with the date 1176/1762-3 on f.1r.Footnote 131 Among the other interesting seals which indicate previous ownership of manuscripts, there are, for example, two seals on BL MS RSPA 3, Jones's copy of Ashiʿʿat al-Lamaʿāt fī sharḥ al-mishkāt, which come from Ṣāliḥ Khān and Ṣubḥ Khān, both servants of ʿĀlamgīr.Footnote 132

Fig. 24. The scribe's signature and ownership note of Aḥmad ibn ʿĀmir al-Saʿdī al-Ḥaḍramī.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 96

Another curious manuscript of the Jones collection is BL MS RSPA 113, which is covered with seals (Fig. 25), almost all of which, apparently, are from the same man, the author and scribe of the manuscript. This is Jones's copy of Ṭayf al-Khayāl fī munāẓarat al-ʿilm wa-l-māl, authored by Muʾmin ʿAli Khān (fl.1074-1130/1663-1718), otherwise known as Muḥammad Muʾmin ibn al-Ḥājj Muḥammad Qāsim al-Jazāʾirī ‘l-Shīrāzī. Born in Shiraz, Muḥammad Muʾmin grew up in Khuzestan and moved, according to Āqā Buzurg al-Ṭihrānī, to India at the end of Rabīʿ al-Awwal 1102/January 1691, where he took on the name of Muʾmin ʿAli Khān, the name on the vast array of seals on the manuscript (Fig. 25). Carl Brockelmann also mentions Muʾmin ʿAli Khān and this text, with a slightly fuller biographical description of Muʾmin ʿAli Khān in the Supplement, wherein he lists this manuscript along with several other copies.Footnote 133 Furthermore, Alphonse Mingana mentioned another manuscript at the John Rylands Library, Arabic 675 [398], called Khizānat al-Khayāl, which provides some biographical information, namely that he went to India and was appointed by ʿĀlamgīr as the chief tutor to his favourite grandson Jahāndār, later to become Jahāndār Shāh (d.1125/1713). Footnote 134

Fig. 25. A selection of the seals on BL MS RSPA 113 almost all of which refer to the author and scribe of the manuscript, Muḥammad Muʾmin ibn al-Ḥājj Muḥammad Qāsim al-Jazāʾirī ‘l-Shīrāzī.

Source: British Library, MS RSPA 113.