1. Introduction

Proponents of Austin Farrer's solution to the Synoptic problem affirm two theses: (i) Matthew used Mark in composing his Gospel, and (ii) Luke used both Mark and Matthew.Footnote 1 Part of the strength of the view lies in its theoretical parsimony. Unlike its main rival, the two-source hypothesis (2SH), Farrer's position obviates the need to postulate the existence of an independent sayings source (Q) in order to account for the large agreements between Luke and Matthew. One can explain Lukan features by affirming that the evangelist used Mark as his narrative backbone and then drew on Matthean material when he found the latter suitable to his purposes.

A central line of attack against the Farrer hypothesis (FH) is the perceived implausibility that Luke would have organised Matthew's material in the way he allegedly did. Why would Luke, for example, take the elegant, flowing Matthean discourses, cut them up, and scatter some of them throughout his own Gospel? Werner G. Kümmel is perplexed: ‘What could possibly have motivated L[uke] … to shatter M[atthew]'s sermon on the mount, placing part of it in his sermon on the plain, dividing up other parts among various chapters of his Gospel, and letting the rest drop out of sight?’Footnote 2 In light of this type of objection, defenders of the FH have advanced a number of reasons that would make Luke's editing more understandable. Perhaps Luke thought his own configuration was more appropriate; perhaps he had theological motivations for spreading out Matthew's discourses. I lay out a number of these options later in this article.

My objective is to propose a different sort of incentive for Luke's abbreviating Matthew's discourses: his modifications are the result of wanting to bring his Gospel into closer conformity with the literary standards of Greco-Roman biographies.Footnote 3 While the various characteristics of ancient bioi fall along a spectrum, I provide data from seventeen sources which indicate that uninterrupted speeches in ancient bioi had a strong tendency to be shorter – much shorter – than what we find in Matthew, especially relative to the Gospel's length. Moreover, Luke's literary style is widely recognised as the most sophisticated among the Gospels.Footnote 4 It seems reasonable, therefore, to suppose that Luke is bringing his Matthean source, along with the latter's lengthy discourses, into closer adherence to classical standards of Greco-Roman bioi. If this thesis is correct, it represents one further explanation of why Luke had ample reason to modify his Matthean source.

2. Matthew's Numbers and Luke's Modifications

It will help to begin with a more informed exposition of the Matthean passages under discussion. For present purposes, I focus on continuous speeches that lack a change in subject – i.e. discourses that do not include interruptions by Jesus’ disciples, the Pharisees, the crowds and so on. Luke often punctuates Jesus’ speeches with small narrative interruptions such as ‘Then Jesus said …’ or ‘Turning to his disciples, he said …’Footnote 5 Luke's speeches would be much shorter if we were to count these as narrative breaks. In my analysis, however, I overlook such small interruptions and regard the speeches as continuous, barring changes in subjects.

The two longest continuous Matthean speeches occur in Matt 5.3–7.27 and Matt 24.4–25.46. The first of these, the Sermon on the Mount, contains an astonishing 1,933 words.Footnote 6 It is composed of at least twenty-three shorter sections including the Beatitudes and the Lord's Prayer, and each topic flows without transition into the next. The second passage, Matt 24.4–25.46, is slightly shorter and runs at 1,494 words.Footnote 7 Here we have Jesus’ eschatological discourse: the predictions about the temple's destruction, the future persecutions, the parables involving watchfulness and the ultimate judgement by the Son of Man.

Let us consider each section individually and note how, according to Farrer theorists, Luke has modified Matthew. Table 1 details Luke's changes in the Sermon on the Mount. The Sermon on the Mount, as mentioned above, contains 1,933 words. After Luke's changes, his Sermon on the Plain is left with 569 words, only 29 per cent of the length of the original. As Table 1 indicates, the types of modifications come in at least three forms (or a combination of them): direct omission of a particular topic (adultery, almsgiving, oaths), relocation to a different place in the Gospel (the Sound Eye, the passage on worrying) and reduction (the Beatitudes, the Lord's Prayer). Now, in several cases, Luke has introduced new elements into his Sermon on the Plain, but the material he has brought in fits neatly within the context. The woes (6.24–5), for instance, function as antitheses to the remaining Beatitudes and reflect the Lukan emphasis on the reversal of fortunes.Footnote 8 Similarly, Luke imports the saying about the blind leading the blind from Matt 10.14 into Luke 6.39. The reason for the latter is clear: Luke's immediate context contains the pericope about removing the speck from a brother's eye (Matt 7.3–5 // Luke 6.41–2). Even with these additions, Luke's final product is drastically shorter. Much of it is omitted, and much else is shifted to other places.

Table 1. Modifications to the Sermon on the Mount

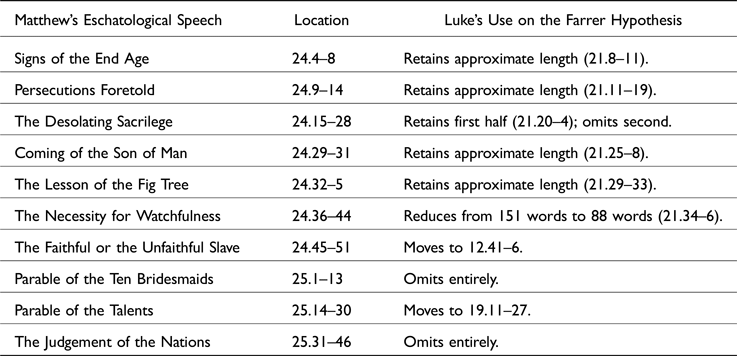

The second major block of Matthean discourse is Matt 24.4–25.46. The Lukan modifications are indicated in Table 2. Matthew's eschatological discourse adds up to 1,494 words, and Luke has reduced it to 30 per cent of its original length, leaving his shorter speech at 442 words. We should note that Luke has for the most part replicated Mark 13 in this section,Footnote 9 and the Matthean additions have been either omitted or relocated. Luke's reduction in this passage, however, should not be attributed to his slavishly following Mark's length. After all, he reduces the length of Markan material elsewhere.Footnote 10 The best explanation is that Luke has intended to shorten and redistribute Matthew's eschatological discourse, and his Markan source delivers a structure of adequate length.

Table 2. Modifications to Matthew's Eschatological Speech

Given that Luke has reduced Matthew in this way, how long are his own speeches? Again, if our word count is based on lack of subject changes, then Luke has five longer discourses. Ordered by length, they are 384 words (Luke 16.15–17.4), 442 words (Luke 21.8–36), 486 words (Luke 17.20–18.14),Footnote 11 569 words (Luke 6.20–49) and 778 words (Luke 15.4–16.13).Footnote 12 Luke's longest uninterrupted speech is therefore roughly a third of Matthew's Sermon on the Mount, and about half of the latter's second longest discourse. Moreover, Matthew and Luke contain roughly the same number of words (18,300 vs 19,400). Relative to these lengths, the Sermon on the Mount constitutes 10.6 per cent of Matthew, and Luke's longest speech amounts to 4 per cent of his Gospel.

3. Attempts to Explain Luke's Modifications

Advocates of the 2SH often interpret the above data as a strike against the Farrer hypothesis. The reasoning proceeds as follows: Matthew's venerated Sermon on the Mount is arranged elegantly; the material it contains fits appropriately in its context. On the FH, however, we must suppose that Luke has undone this sophisticated arrangement, eliminating and/or redistributing the Matthean fragments around his Gospel. And this procedure – the argument goes – is unthinkable. Even as early as 1924, Burnett Hillman Streeter had denounced the idea that Luke had broken up and reappropriated Matthew's Sermon. For Streeter, this idea would imply that Luke took ‘utmost care to tear’ the relevant Matthean pieces out of their ‘exceedingly appropriate’ contexts – a strategy which would be tenable only if ‘we had reason to believe [Luke] was a crank’.Footnote 13 Similarly, Heinrich Holtzmann had characterised Luke's policy as ‘wantonly’ breaking up Matthew's ‘great structures’.Footnote 14 More recently, Graham Stanton has stated that Luke would have ‘virtually demolished Matthew's carefully constructed discourses’.Footnote 15 Clearly, such disapproval is thinly veiled! But is it warranted? The argument hinges, of course, on the supposition that if Luke had known Matthew, he would not have redistributed the material in the way FH theorists envision. And what reason undergirds this supposition? Presumably it is the judgement that Matthew's long, flowing discourses were appropriate, decorous, and fashionable, so that there was no need to alter them.

The easiest way for FH theorists to rebut the above argument is to furnish some possible reasons why Luke would have found his own arrangement preferable. For instance, Luke might have had pragmatic considerations in mind: perhaps he thought that the length of Matthew's discourses made them difficult to read or hear in one sitting.Footnote 16 The sheer range of topics covered in the Sermon on the Mount – more than twenty-three flowing disparate themes – might have been overwhelming. Michael D. Goulder judges: ‘Matthew's Sermon is far too long. Who can take in so much spiritual richness in a single gulp?’Footnote 17 A different response highlights the inherently subjective element in classifying Matthew's grandiose narratives as more ‘elegant’ or ‘appealing’ than Luke's. Appealing to whom?Footnote 18 Perhaps they were not appealing to Luke – perhaps his own arrangement had a greater aesthetic draw.Footnote 19 Indeed, one might equally question whether Matthew's prolonged narratives are superior.Footnote 20

Some have argued, alternatively, that Luke has a discernable method in adjusting the Matthean material. Francis Watson identifies what he calls a ‘simple compositional procedure’ that Luke follows which involves, for instance, juxtaposing large-scale blocks of material and redistributing a significant number of Matthean sayings throughout his own journey narrative.Footnote 21 Another motivation for Luke might have been theological.Footnote 22 Mark Goodacre, for instance, suggests that Luke adopts the Markan motif of the Way of the Lord, a theme which Mark takes from Isaiah.Footnote 23 Theologically, the Way of the Lord provides the narrative structure for Luke, and this structure allows him to distribute Matthean material throughout his own Gospel. All these reasons – pragmatic, aesthetic, procedural, theological – are not mutually exclusive. And the more reasons provided for Luke's modifications, the less weight the objection carries.Footnote 24

In what follows, I advance another reason why Luke reduces and distributes Matthew's lengthy discourses. This reason has to do with the genre of the Gospels. Since the publication of Richard Burridge's book, What are the Gospels?, scholarship has come to (re)recognise that the four canonical Gospels fall under the genre of Greco-Roman biography.Footnote 25 One of the consequences of this shift has been the profitable literary, rhetorical and historical analysis of the Gospels once they are situated against the backdrop of classical works of the same genre, e.g. the Lives of Plutarch or Suetonius.Footnote 26 Part of the ensuing challenge (and charm) is that the generic term ‘Greco-Roman biography’ does not pick out any sort of well-defined essence so that any literary work either has or does not have that essence. Instead, the genre serves to set apart a group of works that share various family resemblances.Footnote 27 This fact allows significant diversity among ancient biographies, and it also establishes a sort of spectrum on which some may be considered more ‘standard’ than others.

The diversity among Greco-Roman bioi also allows one to understand certain variations among the Gospels. While the Gospels share many features, each has its own style and emphases. In comparison with the other Gospels, for instance, Luke more closely corresponds to Greek classical style with respect to its rhetorical and literary construction.Footnote 28 Consequently, some advocates of the FH have suggested that Luke's modifications can be explained in terms of his bringing his Gospel into closer conformity with classical standards suitable to Greco-Roman bioi.Footnote 29 With respect to the Sermon on the Mount, Luke's catalyst for shortening Matthew's lengthy discourses was that he was aware that bioi most often contained shorter rather than longer speeches. Now, clearly, the claim is not that long, uninterrupted speeches were impossible or that ancient biographers never wrote that way. After all, Matthew also fits the description of a Greco-Roman bios.Footnote 30 The claim is rather that among the classical works properly labelled ‘ancient biography’ the speeches were generally much shorter than what we find in Matthew. Luke therefore has precedent for introducing his modifications.Footnote 31

What arguments support the position that Greco-Roman bioi generally favoured shorter speeches? Scholars who have advanced this view have typically adopted what we may call a prescriptive approach. In other words, they point to ancient works that functioned to instruct, guide or prescribe how acceptable classical rhetoric ought to be written. Heather Gorman, for instance, draws attention to Greek progymnasmata, sets of exercises that ancient authors would have used to develop their rhetorical skills. She also touches upon rhetorical handbooks such as we find in Quintilian's Institutio oratoria. Footnote 32 From the progymnasmata and rhetorical handbooks, we learn that ancient authors often focused on three primary ‘rhetorical virtues’: clarity (σαφήνεια), conciseness (συντομία) and credibility (πιθανότης).Footnote 33 Aelius Theon, for example, describes clarity as the quality an author achieves when he or she ‘does not narrate many things together but brings each to its completion’.Footnote 34 Similarly, Theon claims that conciseness involves ‘signifying the most important of the facts, not adding what is not necessary nor omitting what is necessary to the subject and style. Conciseness arises from the contents when we do not combine many things together’.Footnote 35 Gorman believes that all three rhetorical virtues are at play in Luke's Gospel. She argues, moreover, that Luke may be exemplifying the virtue of conciseness or brevity when the Evangelist shortens Matthew's Sermon on the Mount. Luke's editorial activity, in other words, is on display as he makes Matthew's lengthy material shorter, thereby bringing his final product into closer conformity with ancient rhetorical virtues such as those described in the progymnasmata.Footnote 36

Gorman's approach serves as a valuable way of defending the position that Luke's modifications may be in line with his Greco-Roman influence – a view that is often asserted in passing but is generally left unsubstantiated.Footnote 37 There are, however, two drawbacks to this approach. First, it is doubtful that such rhetorical prescriptions, even if authors were familiar with them, were always followed. Modern English students, for example, may learn certain norms or directions for writing a novel; it is doubtful, however, whether those guidelines are always (or even usually) implemented. Second, it is uncertain how the rhetorical virtues described in the progymnasmata would have been applied across different genres and categories. Brevity in a historical monograph, for example, will presumably differ from brevity in a court room speech; and these types will differ from brevity in a Greco-Roman biography. It seems to me, however, that there is a way to strengthen this sort of argument. It involves supplementing Gorman's prescriptive project with a descriptive one: we ought to look into Greco-Roman bioi themselves as our starting points. After examining length of speeches within them, we may then proceed to conclusions about Luke's literary style.

4. Speech Length in Greco-Roman Biographies

As we saw earlier, works within a genre are related by certain family resemblances and thereby fall on a spectrum. Scholars often cite a handful of writings as representatives of the biographical genre. Burridge's volume contains an examination of such works written across a span of 600 years. I take his list as my starting point, and I have added several others.Footnote 38 Table 3 summarises the length of the speeches found within those works.Footnote 39 One conclusion that may be gathered from the data is that speeches generally tended to be quite short. The case of Philostratus’ massive work, Life of Apollonius, appears to be an exception to this rule, and I will comment on it separately. Among the rest of the works, twelve contain either no speeches or speeches that are less than 200 words.Footnote 40 The Life of Aesop, Philo's Life of Moses and Tacitus’ Agricola have speeches that are slightly longer, somewhere between 300 and 600 words. Against this backdrop, we can observe that Matthew's two longest discourses – roughly 2,000 and 1,500 words each – do not fit the general mould. If the above classical works are representative of Greco-Roman bioi, then ancient audiences who were accustomed to hearing/reading works like them would have noted the uncharacteristically long, flowing nature of Matthew's speeches. We need not suggest that Matthew's style would have been met with disdain or adversity; it would simply have been unusual – something unanticipated by audiences.

Table 3. Speech Lengths in Ancient Biographies

1 E.g. Ages. 5.5–6.

2 Att. 21.5.

3 Vita 134–9.

4 Mos. 1.322–7.

5 Agr. 30.1–32.4; 33.2–34.3.

6 Vita 256–8.

7 Ant. 84.2–4.

8 Cat. Min. 45.3–4; 61.2–3; 68.4–5.

9 Pomp. 74.3–4.

10 E.g. Alex. 50.

11 Dem. 20.

12 E.g. Jul. 66.2–3.

13 E.g. Aug. 28.2.

14 Plot. 17.15–40; 19.7–43; 22.13–63. The 691-word section at 20.18–105 is not a speech but a copy of the preface of a different work.

15 Vit. soph. 1.517.

16 Examples of typical speech length: Vit. Apoll. 1.1.1–3, 7.1–3; 4.38.1–5; 5.33.1–5; 6.10.4–6. Speeches between 700 and 1,200 words: 2.29.2–32.2; 5.14.2–17.1; 7.14.1–11. 1,874-word speech: 6.11.2–20. Final apologetic speech: 8.7.1–50.

An analogy might be helpful. Those who enjoy Broadway musicals may be familiar with some of the following: Les Misérables (1980), The Phantom of the Opera (1986), Rent (1996), The Lion King (1997) and Wicked (2003). While these productions fall under the same broad genre, they also show great topical diversity. The subject matters range from struggling peasants during the French Revolution, to competing witches in the land of Oz, to singing animals on the Serengeti. The length of the songs within them vary: while a handful last between 1 and 2 minutes, the majority run around 3–4 minutes. In the Phantom of the Opera, there are a couple of longer pieces lasting ten and eleven minutes – one of which is the concluding piece. Those with a palate for musicals unconsciously carry such expectations as they enter the theatre: songs will generally be shorter. If they go beyond nine or ten minutes, the audience will notice, and they may look for a reason to justify the length.

Our passages in Matthew are analogous to unusually lengthy songs in contemporary musicals. It is not that they are necessarily objectionable or inconvenient: they are just out of the ordinary. Suppose there is a musical that contains a few songs that are untypically prolonged. And let us say a new composer decides to create her own revised version of the musical. It would be entirely understandable for the composer to design her version in a way that accords with more ‘normal’ musical standards. She may do so by shortening the songs, dividing up segments of a piece, casting the segments in different parts, organising the themes differently, and so forth. In fact, this is what happened with the musical Chess. Footnote 41 A similar phenomenon may be taking place as Luke trims and reorganises Matthew's discourses. Thus, from Matthew's 2,000- and 1,500-word speeches, we get Luke's which have 384 words, 442 words, 486 words, 569 words and 778 words.Footnote 42

At this point, one might question whether the last example in the chart, Philostratus’ Life of Apollonius, constitutes a significant obstacle in the present argument. The majority of the speeches in it (at least fourteen) consist of between 300 and 600 words, three of them range between 700 and 1,200 and one consists of approximately 1,900 words. The final ‘speech’ (which is rather a transcription of Apollonius’ defence that is never presented) nears the 6,000-word mark. Before concluding too much from this single work, however, we should keep a couple points in mind.

First, while Burridge includes the Life of Apollonius in his study on biographies, he and others acknowledge that there are significant problems with regarding it as a Greco-Roman bios at all.Footnote 43 Ewen Lyall Bowie maintains that despite the work's title, Vita Apollonii, it is not a Vita in the proper sense.Footnote 44 Part of the problem is precisely its size. Medium-length bioi generally fall within the 5,000 to 25,000-word range ‘at the very extremes’,Footnote 45 and the Life of Apollonius contains an astounding 87,000 words. In fact, its length more closely corresponds to that of a philosophical treatise or a historical work.Footnote 46 But, second, even if we do think that the Life Apollonius is an ancient bios, we may be able to explain its long speeches in terms of its overall length. At 87,000 words, the work is nearly five times longer than Matthew's Gospel. It is not far-fetched to suppose that Philostratus (and others) considered his longer speeches acceptable in light of the enormity of the work itself. And even so, it is astonishing that the longest speeches (excepting the final apologetic transcript), which range from 700 to 1,900 words, are still shorter than Matthew's first major discourse. It seems that the best inference is this: if we consider the Life of Apollonius to be an ancient biographical work, it represents an end of a spectrum – and therefore it should not be considered a core representative of the rhetorical or literary features of other ancient bioi such as the others represented on the chart.

Another way of underscoring the present point is to look at authors who composed works of different genres. An adequate undertaking of such a project would fall beyond the scope of this project, but I will briefly comment on Josephus. As Table 3 indicates, Josephus’ first-century (auto)biography is roughly 16,000 words long, and its longest speech is a hundred words. In this respect, it resembles Plutarch's Cato Minor. When, however, we compare his Life to his other historical works, Jewish War and Antiquities, we discover that the speeches in the historical genre are longer – many times over. Of the two works, Jewish War contains direct discourses that exhibit a higher level of rhetorical sophistication, while the Antiquities’ speeches are less frequent and more casual.Footnote 47 In Jewish War, the length of the speeches of Agrippa, Eleazar and Josephus is 2,157, 1,338 and 1,297 words respectively.Footnote 48 And in Jewish Antiquities, the fourth longest speeches range between 700 and 900 words.Footnote 49 Now, as historical monographs, the two works are much longer than Josephus’ autobiography. But this is precisely the point: shorter speeches are rhetorically more fitting to biographies. That is why Josephus includes short, pithy statements in his Life, but he is at complete liberty to make the speeches in his historical works more than twenty times longer: the longer discourses are fitting to the genre. A comparison with the Gospels is telling: Matthew's 2,000-word and 1,500-word speeches are more akin to those in Josephus’ Jewish War and his Jewish Antiquities. Recognising this, an author such as Luke might consider his modifications entirely appropriate.

5. Counter-examples from Acts?

So far, our discussion has emphasised that attentiveness to genre and word counts is consequential for understanding the Gospels’ speech lengths. As a final point, I will consider a potential response to the above argument. As we saw, advocates of the FH often maintain that Luke has abbreviated and rearranged parts of his Matthean source because he prefers shorter discourses.Footnote 50 One potential objection is to point out that Luke seems to include longer speeches in Acts. Christopher Tuckett, for instance, draws attention to Peter's Pentecost speech, Stephen's 52-verse discourse in Acts 7 and the story of Cornelius’ conversion in Acts 10.Footnote 51 In light of these (alleged) counter-examples, he concludes that the ‘appeal to Luke's desire for brevity thus seems unconvincing’.Footnote 52 The assumption implicit in the argument is clear: if Luke employs longer speeches in Acts, then it is unlikely that he had a concern for brevity in his Gospel. This supposition, however, is questionable on two counts.Footnote 53

First, it overlooks differences in genre. Most scholars regard Acts not as a bios proper but as a work of ancient historiography.Footnote 54 This difference, of course, in no way subverts the unity of Luke-Acts: after all, authors were entirely capable of writing works of different genres (e.g. Josephus), and the borders between genres could be blurred. However, one of the distinctive features that set bioi proper apart from ancient historiographical works was that the former typically focused on a single protagonist while the latter could follow various characters.Footnote 55 So, on the one hand, we should observe that Stephen's speech, the longest discourse in Acts, has 999 words and is longer than any speech in Luke. On the other hand, since Acts itself is not a bios, one should avoid imposing the expectations of the Gospel's speech lengths onto it. Moreover, the presence of multiple characters in Acts provides a partial contextual reason for the length of Stephen's discourse: he has barely been introduced in chapter 6, and readers must go from ignorance to understanding his martyrdom – a task not easily accomplished in a short (e.g. 400–500-word) speech.Footnote 56

Second, it is helpful to examine the lengths of other discourses in Acts before drawing any overarching conclusions. The alleged counter-examples in Acts are not as impressive as Tuckett supposes. The five longest speeches have the following lengths: 361 words (Paul's address to the Jerusalem crowd), 422 words (his defence before Agrippa), 425 words (his speech in Pisidia), 431 words (Peter's Pentecost discourse) and 999 words (Stephen's oration).Footnote 57 The first four are in fact shorter than most of the Lukan discourses.Footnote 58 Stephen's speech is, of course, longer than the rest, but its significance should not be overestimated due to the considerations discussed above.

In sum, the counter-argument from the longer speeches in Acts carries less weight than often assumed. An attentiveness to word counts reveals that most of the speeches are no longer than those found in Luke, and Stephen's speech is easily explained contextually and in terms of differences in genre.

6. Conclusion

The argument I have advanced is part of a cumulative reply to the following objection: it is impossible, unthinkable or unlikely that Luke would have reduced Matthew's long discourses in the way Farrer envisioned. My reply is that Luke had a literary/rhetorical reason for doing so. As the above analysis suggests, the usual expectation for Greco-Roman bioi was for speeches to be relatively short – at least shorter than what we find in a medium-length work such as Matthew. To put the conclusion of the article more generally, we may say that debates about the Synoptic problem might be advanced (i) by the appreciation of the Gospels as bioi, and (ii) by the careful comparison with works of the same genre, especially with respect to word counts.Footnote 59