Introduction

In the past forty years, much has been written about the history of the evolution of department stores in modern industrialized countries. Most of the works focus on the rise and development of department stores in France, the United States, and Britain from the middle of the nineteenth century to the 1930s. They emphasize department stores both as a central feature of modern consumer culture and as playing a role in modernization, nationalism, mass market development, and consumer society creation.Footnote 1 Benson and Harris focus on entrepreneurs and their families, store managers, and salespersons. The entrepreneurs’ innovativeness and managerial skills greatly influenced their success in the department store business, and entrepreneurial success was also influenced by their families’ support in terms of their ability to supply labor and capital and maintain the store’s image. Store managers modernized their accounting and inventory systems, improved the layout of selling departments, and developed better display methods and fixtures, which curbed the influence of the all-powerful buyers in American department stores. Furthermore, scholars have also attached importance to saleswomen, and emphasized the rise of welfare and training programs, the close relationship between personnel policy and successful marketing, and the opportunities that stores offered employees with regard to other occupations available to them.Footnote 2

Department stores later spread to Russia, Canada, Japan, South America, several British dominions, and China, where they also played a role in urbanization and social modernization.Footnote 3 The literature has noted that department stores in these countries were influenced by the forerunners discussed earlier. Department stores in New Zealand were increasingly influenced by American ideas on salesmanship.Footnote 4 In Japan, department stores were deployed as instruments of westernization and originated much as British department stores had: “both typically grew out of drapery stores and expanded by offering new lines of merchandise.”Footnote 5 In China, the focal country of this study, department stores emerged at the end of the nineteenth century when concessions were established. They were foreign funded and targeted foreigners as customers. Shortly after, Chinese businessmen who returned home from abroad used domestic capital to set up department stores that were based on Western models but followed Chinese business practices and cultural values. However, the political and economic turmoil during the 1920s and 1930s slowed their growth.Footnote 6

After World War II, when department stores in other countries were engaged in continuing their modernization, rebuilding their fashionable reputations, attracting customers, and supporting urban renewal plans, Chinese department stores deviated from this course due to the planned economy system. American department stores began to “fulfil their long-delayed dreams of expansion and modernization,” and the heads of major stores supported urban renewal plans.Footnote 7 Department stores in London invested in visual merchandising to attract customers and rebuild their fashionable reputations.Footnote 8 In China, the planned economy was formed during the first several years of the founding of the PRC (1949). Under this system, instead of operating in the market, the production, distribution, pricing, and investment took place according to state plans. Existing department stores in China gradually transferred to public ownership, and new state-owned stores were set up. These department stores sold a wide variety of items and were the main retail channel for apparel, but they acted as rationing agencies that only satisfied basic living demands, similar to grocery stores. For example, an advertisement indicated that Beijing Department Store (BDS) provided many cheap products (RMB 1 cent) to meet basic needs. Consequently, department stores in China underwent a dramatic change from their initial format, in which they “had based their reputation on providing high levels of service, amenities, and even luxury”;Footnote 9 thus, their modernization was delayed. Chinese department stores had to wait until the planned economy system transformed to a market economy system before they could return to the initial format and fulfill their long-delayed modernization. The transition, which is still ongoing, formally began after the 14th National Congress of the Communist Party in 1992, although it had already commenced in some economic zones and industries, including retail, after the implementation of the reform and opening up measures in 1978.Footnote 10

Scholars have begun to pay attention to the decline of department stores in recent years. “The industry’s pursuit of bigness, consumers’ preference for low prices and mass consumption in the suburbs, and government policies that favoured chains, automobility, and mass discounters” led to the fall of American department stores.Footnote 11 Fujioka focuses on the links between the apparel industry and department stores to study the decline of competitiveness of Japanese department stores. In Japan, wholesalers purchased apparel for department stores between the 1970s and 1980s. “The wholesalers depended heavily on department stores, and this was the competitive advantage of Japanese department stores within the value chain.” However, under globalization, competition between wholesalers for department stores and fast fashion retailers has intensified since the 2000s, subsequently affecting the competitiveness of Japanese department stores. The wholesalers struggled to maintain their contracts with Chinese manufacturers, because these Chinese companies preferred producing large-scale merchandise for fast fashion retailers rather than small-scale, more demanding work for Japanese wholesalers. Some Chinese manufacturers decided to terminate their business with Japanese wholesalers and transferred to new industries, as it was difficult to maintain the low-cost labor force.Footnote 12

The diminishing role of Chinese department stores has also become increasingly apparent in China since the end of the 1990s, as the detailed analysis in the following section will show. However, this aspect has not been considered extensively in prior research. Though some reports in business magazines and journals discuss it, they only list reasons for the decline without any systemic analysis.Footnote 13 The transition to a market economy and the accompanying reforms, which did not occur in other countries, made the context of the decline of department stores in China different. Until the end of the 1990s in China, department stores were still mired in the process of marketization, which made the reduction of state subsidies, restructuring of management, and reforms of the distribution systems focal topics for the whole industry. Retail modernization had just started when new retail business formats, general merchandise stores, and warehouse stores first appeared in China in the mid-1990s. Competition among different retail business formats was nonexistent. Major foreign retailers such as Walmart and Carrefour had been in China for only a few years and began to play a role in the expansion of chain stores. A limited number of retailers forced consumers to accept the given prices and variety due to lack of options. Hence, the notion of consumerism was nonexistent. According to the Chinese Urbanization Report 2012, the rate of urbanization picked up in the 1980s and entered a high-growth period in the 1990s and the 2000s. Thus, suburbanization was absent, and retailers, including supermarkets, chose downtown locations for their stores. Therefore, unlike American and Japanese department stores, transition and reforms were more important factors than consumption, competition, suburbanization, the size of the industry, and globalization in the decline of Chinese department stores.

This paper focuses on apparel retail, which was an important category in Chinese department stores, addressing how and why department stores lost their dominant status in the apparel retail industry in China by examining the history of apparel distribution industry. This study starts by exploring the challenges faced by the apparel sector through an analysis of apparel distribution reforms during the transition. It then examines the way that the primary players—department stores and apparel enterprises—coped with these challenges, as well as the effect these challenges had on the department stores. I use the triangulation method (the method of using multiple data)—an indispensable technique in any historical research.Footnote 14 Therefore, the results of interviews with retail and apparel enterprises and data drawn from corporate history publications, company annual reports, various almanacs, general newspapers, gazettes, business newspapers, and business journals are critical.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows: The first section provides a historical background of the apparel market and department stores. The second section illustrates the evolution and mechanism of apparel distribution systems in order to explore the reasons for the challenges faced by the apparel sector in department stores. The third section analyzes the changes in purchasing patterns of department stores in response to these challenges. The fourth section explores strategy changes in apparel enterprises. The fifth section concludes by discussing the reason department stores lost their dominant status and the structural changes in the apparel value chain.

Evolution of the Apparel Market and Department Stores

The Apparel Industry

The apparel enterprises discussed in this paper comprise two types. The first type undertakes all processes from product planning to sales. The second type emerged in the 2000s. Instead of independently producing apparel, these enterprises entrust production to other manufacturers. This study uses apparel enterprises as a general expression for both types.

As most statistical items in statistical yearbooks lack consistency, I use the gross value of industrial output (GVIO) released between the 1980s and 2000s and the main operating income (MOI) of apparel firms between the 2000s and 2010s to analyze the growth of the manufacturing sector. The Chinese apparel manufacturing industry’s first growth leap was in the 1980s. The GVIO was RMB 15 billion in 1981, and increased to RMB 147 billion in 1990. The industry experienced a high rate of growth in the first half of the 1990s. The GVIO in 1995 was 3.5 times higher than in 1990. This growth slowed in the following five years, but then accelerated again and more than doubled every five years in the 2000s.Footnote 15 Although there was no GVIO calculation in the 2010s, the MOI captured the deceleration in growth in the 2010s. The MOI was RMB 242 billion in 2001, and doubled every five years in the 2000s; however, growth decelerated between 2011 and 2015. The highest annual growth rate was 34 percent in 2003, but it fell to below 10 percent after 2014.Footnote 16

The first growth leap resulted from the emergence of township enterprises (public enterprises). Township apparel enterprises emerged in the second half of the 1980s. Before that time, only state-owned enterprises existed. The emergence of township enterprises arose from the Sunan model of Fei Xiaotong (1984), who participated in policy making as a researcher. Because of the limited agricultural land resources in the Sunan district, he realized that township enterprises were appropriate for that area. However, these township apparel enterprises started to become privatized at the end of the 1980s.Footnote 17

Branding and product diversification by private enterprises caused the continuous increase in the first half of the 1990s. With the expansion of consumer demand and foreign investment, domestic entrepreneurs faced two choices: expand the domestic market or rely on foreign investment.Footnote 18 The former option was easier, as cooperation with foreign firms faced policy restrictions and carried high risk. The domestic firms had different backgrounds; some were apparel or machine manufacturers with public ownership, and the remainder had been small-sized processing plants. They established their own brands, and their emphasis on quality helped them achieve better branding. Furthermore, they diversified apparel products, achieving this through expansion into casual wear.Footnote 19

Foreign and private firms had great impact on the subsequent growth, as they accounted for a major part of the industry’s income. After excluding individual households,Footnote 20 the composition of the operating income of the three main ownership types—state-owned, private, and foreign— indicates this effect. Foreign firms had the highest proportion of income (58 percent) in 2005, followed by private (39 percent) and state-owned firms (3 percent). The proportion of apparel income for state-owned enterprises decreased to 2 percent in 2006.Footnote 21 Although the number of foreign firms decreased from 5,965 in 1995 to 2,864 in 1999, it rose again to 5,906 in 2010. The number of private firms also increased greatly in the 2000s, from 5,925 in 2006 to 9,764 in 2009. The MOI for both showed a high rate of growth. The MOI of foreign firms was RMB 68 billion in 1995, and rose to RMB 105 billion in across the next five years. Steady growth continued, and the MOI reached RMB 446 billion at the end of the 2000s. Private firms had a higher growth rate than foreign ones in the second half of the 2000s, increasing sales volume from RMB 148 billion to RMB 546 billion.

The growth of foreign and private enterprises resulted from policy and system changes. Foreign apparel firms’ entry increased rapidly after the state permitted them to enter all cities in 1992, but most chose to enter through joint ventures in the 1990s. Most of these firms were from Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, but a few European and U.S. firms entered the market, such as DuPont’s and Japan Marubeni Corporation’s joint investment in apparel enterprises in Guangzhou and Forall Confezioni S.P.A’s investment in the Shanshan Group.Footnote 12 China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 promoted the entry of a second group of foreign firms. WTO entry specifically promoted foreign fast fashion brands. Almost without exception, they set up wholly owned proprietorship enterprises, although they all had procurement partnerships with Chinese apparel manufacturers. These foreign fast fashion brands grew to become the main apparel brands in the 2010s.Footnote 23 Meanwhile, the number of private firms increased owing to a complete relaxation of limits on private capital in 1992 and the transition of township enterprises to private enterprises. As shown in Table 1, the transition-type firms became the mainstay of the economy.Footnote 24

Table 1 The eight largest companies by sales volume in China’s apparel industry

Note: This table shows the lists for every decade. As only the 1994 list (in the 1990s) and annual lists after 2006 are available, I chose 1994, 2006, and 2016.

Sources: Almanac of China’s Textile Industry, 1995, 16; China National Garment Association published statistics, accessed November 30, 2018, www.cnga.org.cn/html/zx/hyxx/2016/0630/9394.html,www.cnga.org.cn/html/zx/hyxx/2007/0426/1685.html.

The slowdown experienced by private and foreign firms caused growth to decelerate in the 2010s, as these firms still accounted for most apparel manufacturing output. Although their MOI kept growing, their rate of growth decreased sharply. Since the 1990s, the eight largest enterprises in 1994 and 2006 by sales revenue have been private (Table 1). Of two Sino–foreign joint venture enterprises that appeared in 2016, the Chinese partners were both large-scale state-owned enterprises.Footnote 25

Furthermore, the changes in the apparel market show that both domestic and export markets affected the growth of the manufacturing sector. First, in the domestic market, the total volume of retail sales in apparel in 1992 was RMB 158 billion, and increased to RMB 750 billion in 2006. Although there was no total volume of retail sales between 1993 and 2005, the annual growth rate of sales of large-scale retailers indicates the expansion of the domestic market. The growth rate was 30 percent in 1994, and was maintained at greater than 20 percent in the 2000s. However, the growth of both total volume of retail sales and sales of large-scale retailers has decelerated since 2012, thus slowing down the growth of the manufacturing sector. Second, in the export market, the value of exports was USD 4 billion in 1987 and multiplied five times in the next seven years. This growth slowed down in the following four years, stopped in 1999, and started growing again in 2000. Export value exceeded USD 36 billion in 2000 and increased to USD 130 billion by the end of the 2000s. The value exceeded 20 percent of the global total exports in 2002, and China became the largest exporter of apparel in 2006, with 31 percent of the global total. However, the slowdown in the value of exports caused the deceleration of the production growth in the 2010s.Footnote 26

Apparel Retail Market and Channels

The proportion of spending on clothing by both Chinese urban and rural residents showed a declining trend after 1978. Urban residents spent 15 percent of their income on clothing in 1985, but only 12 percent in 1997, and 8 percent in 2014. Among rural residents, the spending proportion decreased from 10 percent in 1985 to 6 percent in 2010. The decrease in proportion of spending on clothing placed pressure on apparel enterprises and retailers.

Department stores were the main retail channel for apparel since the start of China’s planned economy era and therefore dominated the apparel retail market. Until the early 1980s, department stores were almost the only place to purchase apparel. The state rationed apparel, and apparel enterprises had no autonomy to choose a retail channel. The state distributed apparel to department stores according to local allocation rules.Footnote 27

However, the dominant status of department stores has changed gradually since the end of the 1990s. Department stores accounted for the largest proportion (42 percent) of apparel retail sales in 1998, but this figure began to fall in 1999, dropping to 36 percent in 2003. On the other hand, specialty stores rose in importance in the 2000s, taking the market share of department stores. The share of total apparel retail sales for specialty stores was 13 percent in 1998, increasing after five years to 15 percent and passing 30 percent in 2008, making specialty stores the second-largest retail channel.Footnote 28 According to 2011 data, specialty stores became the top retail channel, with more than 53 percent of total sales that year. In the next five years, the share of both department stores and specialty stores fell, owing to the growth of online stores from 3 percent in 2011 to 26 percent in 2016. The market share of department stores decreased to 25 percent, and the market share of specialty stores decreased to 45 percent in 2016.Footnote 29

In addition to being the primary retail channel for apparel, department stores were also dominant in their relationship with suppliers (agents or apparel enterprises in China). When department stores had strong buying power over suppliers, the Chinese apparel distribution system was characterized by a power imbalance between department stores and suppliers, with a “retailer as the leader” power structure.Footnote 30 Department stores’ strong influence on the decision making of suppliers made them powerful. They demanded admission fees from suppliers, as well as a say in promotional activities. As there was no need to develop a market in the planned economy era, apparel manufacturers lacked the skills and approach to explore the retail channel for marketing their products immediately after the reforms. As state-owned department stores were their only option under the growth-supporting policy at that time, apparel enterprises relied on these department stores. However, department stores had more procurement choices, such as foreign apparel brands. This unequal relationship manifested itself in greater buying power for department stores, a situation that continues even now.Footnote 31 This paper therefore explores both the loss of main retail channel status and the loss of buying power.

Historical Case Analysis of Department Stores

Without exception, the definition of a department store in China is a “general retail format offering a wide range of consumer goods in different product categories and services to consumers by several commodity departments inside a building.” Such stores are generally located in bustling downtowns and major thoroughfares; mainly sell apparel and household items in wide varieties and small quantities with high margins; attach importance to the shopping environment; and provide exchange and return services.Footnote 32

Different from department stores, whose investors were retail firms, Chinese shopping mall investors were real estate investment firms or retail firms. These real estate investment companies generally specialized in operating construction, rental, and sale of real estate. The retailers were mostly firms that had experience operating department stores. These founding firms paid in full for constructing the building, owned it, and took charge of lease and estate management. The shopping malls differed from department stores in their revenue source, which was generally rent collected from the stores.

As already analyzed in the “Introduction,” department stores acted as rationing agencies, and thus some small and medium-sized supply cooperatives, the rationing agencies, fell into the category of department stores in the 1980s. Accordingly, the Almanac of China’s Commerce showed a huge number of department stores. There were 161, 000 stores with more than 500 employees in 1987, spread over 660 cities. This fell to 159,000 in 1990.Footnote 33

In the second half of the 1990s, the existing department stores transitioned to become providers of a high level of services, amenities, and even luxury items, and many new department stores emerged. For example, the Shanghai Almanac shows that the total area of department stores in this city rose by about half between 1996 and 1997 to more than 403,000 square meters.Footnote 34 Department stores experienced high growth from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, with the growth rate of annual sales volume peaking at 52 percent in 2004. However, growth dropped thereafter to 2 percent in 2016 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Change in sales volume of department stores.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, China Statistical Yearbook, 2003–2017.

Lifting the restrictions on foreign and private enterprise entry and China’s entry into the WTO diversified the ownership in department stores from the mid-1990s. Although data on the ownership structures are not available, Table 2 shows that the ownership diversification did not affect state-owned firms, which maintained a strong position in sales volume in the 2000s.Footnote 35

Table 2 The eight largest companies by sales volume in department stores in China

Note: All enterprises were state owned in both 1989 and 1999. Retail enterprises tended to develop multiple retail business formats in the 2000s. The eight largest enterprises in 2009, whose main business was department stores, also did so. However, there are no data showing only their department store businesses, and their sales volume includes other business formats.

Source: State Bureau of Domestic Trade, Almanac of China’s Domestic Trade, 1990, 304; 2000, 689; Ministry of Internal Trade, China General Chamber of Commerce, and China Commerce Association for General Merchandise, Almanac of China’s Commerce, 2010, 168.

Apparel is an important category in department stores. However, in China, it did not gain prominence until the 1980s. Its share of annual department store sales reached 33 percent in 1992 and was more than half of sales in the largest three stores in the same year. This share exceeded 50 percent by the end of the 1990s as stores began to attach greater importance to profit margins than total sales.Footnote 36

To illustrate the evolution of Chinese department stores in the post-reform era, this section offers a historical case analysis of Beijing Wangfujing Department stores (BW, which was called BDS until 1993).The second floor mainly sold apparel and apparel materials, while the third floor was for high-end apparel as well as radios, cameras, and watches.Footnote 37

BDS had diverse procurement sources and offerings because it was the only department store with the autonomy to source externally in the first half of the 1980s, although the merchandise from external sources comprised only 25 percent of sales. Visitors from other cities tended to shop at BDS owing to its variety.Footnote 38

BDS had no independent administrative power in the 1980s, as the local commercial bureau ran BDS. Two reforms changed its status. The managerial decentralization reform between1980 and 1991 gave it more autonomy in two steps. First, the commercial bureau scrapped some restrictions for procurement and delegated the management of the sales floor to BDS to increase the variety of merchandise.Footnote 39 Second, in 1991, BDS became an independent company. After mergers and divisions, it became the Beijing Wangfujing Department Store Group (BWG) in March 1993. Since then, BDS has changed its name to Beijing Wangfujing Department Store (BW), although its signage still reads both “BDS” and “BW,” even now. The second reform, in 1993, related to the company’s shareholding system. BW became a listed corporation that shared profits with employees and granted stock ownership. This motivated employees to boost margins, and BW started to consider marketing, which had been nonexistent in the planned economy era.Footnote 40

The marketing campaign changed the store’s image to a place providing high fashion. The store instituted an annual fashion event after gaining managerial autonomy from 1991. They operated a catwalk to demonstrate that they operated in prestigious brands and trendy fashion.Footnote 41

BDS took advantage of the improved marketing and independent procurement, both of which played a vital role in preserving its competitive edge with individual households in the1990s, after the removal of restrictions on private households. Department stores treated private households that had great initiative in procurement as strong competitors, but the independent procurement resulting from the reforms kept them from losing their merchandise assortment. Furthermore, they had a marketing advantage over individual stores, as individual sellers lacked capital for marketing activities. Consequently, BDS achieved five consecutive years of high growth in sales volume in the first half of the 1990s.Footnote 42

However, the sharp increase in the number of new stores made competition vigorous. BDS decided to increase discount promotional activities to maintain growth. This led to a price war, which resulted in a financial deficit and the temporary closure of BDS. The store reopened after an interior redesign promoting BDS’s return to its image of high fashion. BDS set up a visual planning center, emphasizing the use of shop windows, product displays, and lighting to create an elegant and fashionable shopping environment.Footnote 43

Seeking to gain an edge in procurement, BWG began operating chain stores from 1996. BWG opened stores in Guangzhou, Beijing, Wuhan, and Chengdu in the 1990s, along with more than fifteen other stores across the country.Footnote 44

Competition from new retail business formats in the 2000s and the 2010s threatened BWG. It is difficult to obtain data for apparel sales, but we can observe a decline in total sales for BWG. Sales were RMB 20 billion in 2011, but decreased to RMB 17 billion in 2015.Footnote 45

Evolution of the Distribution System and Challenges for Department Stores

Extant literature has presented two challenges that the apparel category faced in department stores. First, the price of apparel was high but its quality was low.Footnote 46 The poor quality was not limited to workmanship and materials used, but also included lack of fashion or design sense.Footnote 47 Second, the brands and apparel that each department store in a city sold were the same throughout the city—a phenomenon termed homogenization. Footnote 48

We can trace these challenges in price, quality, and product line-up to the entire value chain in the apparel industry, but this study focuses mainly on the fourth stage—changes in distribution of apparel products that the economic transition shaped.Footnote 49 While analyzing these challenges from a distribution viewpoint, this study focuses on two systems that control the fourth stage in China—the agent system and the joint-operation system.

This section analyzes the historical context that shaped the mechanism of the two systems and examines how and why the apparel category of department stores faced challenges. Without a buyer-driven purchasing system, which is common in Western countries, Chinese department stores distributed apparel from apparel enterprises using agents. Therefore, the agents were intermediate distributors, but the three parties had no partnership or capital investment with one another. The joint-operation system determined the procurement of merchandise and the sales mode adopted by department stores. According to this system, department stores and apparel enterprises jointly operated the sales process based on a contract, without creating any joint venture. The agents generally acted on behalf of apparel enterprises to operate joint sales with department stores.

The formation of the two systems resulted from government support for manufacturers’ marketing efforts. During the early 1980s, manufacturers struggled to market their goods themselves. In the planned economy era, the state had a monopoly on the purchase and marketing of goods; therefore, the manufacturers were purely a producing sector with no experience in exploring sales channels and no established relationships with suppliers. This left manufacturers unprepared to develop sales channels after the state granted marketing autonomy to manufacturers in 1978. Developing such channels was especially difficult for apparel manufacturers in the 1980s, because the quantity and diversity of apparel products were increasing rapidly while the state prioritized the development of this industry. Owing to the increasing product quantity and diversity, the commercial sector could make its own purchasing choices. Meanwhile, stores began to consider stock risk and were thus more careful about selling apparel products from just any manufacturer.Footnote 50

Store Operation System: Formation of the Joint-Operation System and Challenges

To support the marketing efforts of the early 1980s, the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Light Industry jointly popularized the Dai Pi Dai Xiao system (wholesale and retail of goods on a commission basis) after 1982. Under the ministries’ direction, state-owned commercial enterprises took commissions to act as selling agents. Some were state-owned wholesale enterprises and institutions, and others were the wholesale departments of retailers, including department stores. The products belonged to manufacturers until sold, and thus the commercial sector bore little risk of being stuck with purchased goods.Footnote 51

In 1982, the emergence of the joint-operation system, Lian Ying Lian Xiao (Lian Ying for short), increased commercial enterprises’ involvement, and enabled them to share profits with manufacturers. A joint team comprising representatives from both commercial enterprises (department stores) and manufacturers (apparel enterprises) discussed how to divide their joint-operation earnings, volumes, varieties, quality, and sales-floor operations. Furthermore, this system enabled commercial enterprise to share in profits, which drove their active sales promotion. Consequently, this system not only expanded manufacturers’ performance, but also was favorable to department stores.Footnote 52

Next, two derivative systems emerged, Yin Chang Jin Dian (providing selling area to manufacturers) and Chu Zu Gui Tai (renting counters), which incurred less risk for department stores than joint operations. Under the first system, stores only provided an area and facilities, while manufacturers dispatched staff to operate the sales floors. Both parties shared the profits. Rental of counters replaced Yin Chang Jin Dian and became the main system between the end of the1980s and the early 1990s as department stores took fewer risks. They rented out counters to manufacturers and, instead of earning profit from sales, earned only rent. The manufacturers could modify the sales floor freely.Footnote 53

However, counter rentals caused mismanagement problems, forcing stores to revert to joint operations. As significant increases in individual vendors at the time threatened the performance of department stores, these stores rented out counters not only to manufacturers, but also to individual vendors. It was difficult to control the purchase channels of individual vendors, who began to sell counterfeit goods. To curb this practice, the government proposed a policy of no counterfeit goods in stores. The Ministry of Commerce eventually banned the system in 1991. This ban made the joint-operation system popular again.Footnote 54

Department stores and apparel enterprises promoted the significant expansion of joint operations from the mid-1990s without government guidance. After more than ten years of operating these systems, manufacturers in various industries gained marketing experience and built relationships with distributors. Therefore, the system became obsolete. Nonetheless, the department stores and apparel enterprises retained it. One account argues that the system benefited department stores by reducing inventory risk during the second half of the 1990s, when the increase in the number of department stores led to fierce competition in apparel retail. Moreover, the entry of luxury brands into China in the 2000s also promoted the expansion. Luxury brand manufacturers generally chose department stores as their retail channel, rather than operating direct-sale stores, because they were unfamiliar with the managerial environment in China. Consequently, more than 90 percent of department stores operated using this system in the 2000s.Footnote 55

Joint operation became normalized during this period. With the enactment of contract law and the requirements involved in selling foreign luxury brands, department stores and apparel enterprises began to make their respective mandates clear through contracts. The parties’ contracts defined operational fields—sales area, contact terms, promotions, management of sales floor and staff, decoration rules, and sales guarantees—more comprehensively than the joint team had done before. Contracts also defined the percentage of monthly revenue department stores could deduct (different between stores, and averaging 25 percent), with the rest being paid out to apparel enterprises and agents. Except for joint operation, department stores had their own separately determined roles (Table 3), which shaped their buying power. They could: (1) provide sales floors and manage the sales shopping environment; (2) choose which brands to stock; (3) supervise the merchandise of each brand; (4) provide a single cashier for all brands; and (5) organize promotional activities uniformly in the whole store and supervise promotional activities organized by apparel brands.Footnote 56

Table 3 Department stores’ participation through store operation mode.

Note: Y, department stores participate; N, department stores do not participate; B, both department stores and suppliers participate.

Source: Li, “Zhongguobaihuodian,” 3.

The joint-operation mechanism resulted in low gross margins for apparel enterprises. Apparel enterprises could receive payment only after department stores deducted their part of the revenue. Moreover, as department stores could decide the entrant brands, display places, and sales patterns, apparel enterprises had to pay an admission fee to enter or maintain a display at a department store. The admission fees were circulation costs for apparel enterprises. For a better location, they had to be able to afford higher admission fees.Footnote 57 This also demonstrated the strong buying power of department stores wielded over apparel enterprises.

The increase in unified promotional activities by department stores also led to the low gross margins for apparel enterprises. Following BDS, Chinese department stores began to focus on reforming marketing and services in the mid-1990s. A great increase in department store numbers in the second half of the 1990s further forced them to improve marketing and services to stand out from the competition. However, the minimal amount of marketing and service that prevailed at that time meant that they could only achieve their goals through deep discounts. Consequently, in addition to clearance sales, department stores frequently organized promotional discounts. For example, the general manager of Nanjing Xinjiekou Department Store identified increased promotion as the principal target for 1999. This phenomenon had become more common as departments stores faced homogeneous competition from brands. When a department store undertook sales promotions, other local stores followed suit to prevent any single department store from attaining larger market share for the same brands. Consequently, the stores lowered prices, and apparel enterprises received lower revenue and so earned lower margins. The China General Chamber of Commerce called for fair promotion at the time, illustrating the extent of unreasonable discounts.Footnote 58

Evolution of Intermediaries: The Agent System and Its Challenges

As the analysis in the previous subsection showed, before the emergence of agent system, state-owned commercial enterprises acted as intermediaries supporting manufacturers through the initial stages of marketing, including via department stores.

In addition to commercial enterprises, the emerging wholesale markets became important intermediaries between manufacturers and retailers. Researchers on intermediary reforms found that the state should promote reduction of the then-existing circulation operated by state-owned wholesale institutions, and that diversity was necessary. Some researchers considered developing a new format, called wholesale markets, to solve the system’s problems. The state adopted their suggestions. Wholesale markets specializing in apparel began to emerge in the late 1980s. These markets were state owned or established by a township under urban planning. Their origins lay in the local bazaars. Both the local textile enterprises and state-owned commercial sectors opened stores and agencies in the wholesale markets for wholesaling and procurement.Footnote 59

The wholesale markets acted on the circulation between manufacturers and department stores, but the emergence of the agent system at the beginning of the 1990s changed and formalized this circulation. The wholesale markets consequently became the intermediaries for individual vendors.

The Ministry of Internal Trade first promoted the agent system in 1994, as a state of undersupply had ended. With this change, retailers and manufacturers struggled to expand sales, and department stores began to trade cautiously with manufacturers to avoid overstocking, which led to strained relations. In this context, the ministry first promoted the agent system. Meanwhile, multiple forums promoted the agent system. For example, in National Agent System Forums in 1995, researchers agreed to utilize the system to improve relations and argued that agents could help exploit channels nationwide. They defined this system as follows: “Agents are entrusted by the vendors to sell products and accept remuneration during a stated period in a stated area; instead of earning the spread, agents earn a commission on the revenue, as specified in the contracts.”Footnote 60

The government and apparel enterprises played an important role in the expansion of this system in the apparel sector and acted to influence transaction practices (agents’ deductions and the flow of money). The initial agents were previously state-owned and private wholesalers, some of which had stores in the wholesale market. The Ministry of Internal Trade and the Ministry of Commerce first directed state-owned wholesalers to become agents and recover from the loss of monopolization after manufacturers gained autonomy in marketing. Meanwhile, apparel enterprises strove to persuade private wholesalers, with whom they had existing long-term trade relationships, to become agents during the second half of the 1990s. For example, Ningbo Shanshan once used the line “be an agent of Shanshan, you will be a billionaire” during China Fashion Week to attract private agents. As an agent could deal with only one manufacturer, those private wholesalers were loath to give up the networks they had so laboriously assembled. Furthermore, these wholesalers could not afford the risk of persuading their clients (retailers) to accept this new system. Apparel enterprises persuaded private wholesalers by allowing them and their clients (retailers) to procure goods without any payment. Under this arrangement, the merchandise belonged to the apparel enterprises all through the circulation until the retailers sold it. This reduced the risk for agents and retailers and, thus, agents could easily build a network with retailers. Furthermore, apparel enterprises allowed agents and retailers to pay the remaining revenue only after they had deducted a part of the revenue as costs and their earnings (Figure 2). Consequently, private wholesalers were more receptive to the possibility of becoming agents, and these transaction practices became a fixed trading discipline. Although agent commissions helped the system expand, they increased the circulation cost, leading to low margins for apparel enterprises. Agent costs accounted for 20 percent of retail prices.Footnote 61

Figure 2: The business framework of agents in China.

Source: Sugino, “Buyer Supplier Channel Networks in China Retail Market,” 118.

The initial agents played a role in establishing the trade rules. Agents normally traded with the retailers with whom they had traded during their wholesaling careers. They had to persuade their old partners by promising to support them in display, delivery, promotion, decoration of sales floors, staff training, and management. Since then, these support activities have become standard practice. Consequently, in addition to helping with procurement of merchandise, the agents also assisted retailers in retail sales. Department stores particularly welcomed agent participation in retail under the joint-operation system. Furthermore, in the department stores, agents not only organized brand promotional activities, but also cooperated with stores for unified promotions and product displays.Footnote 62

High-profile brands developed a tiered agent system. The agents of department store brands shared this feature. Generally, there was a set of three agents (Figure 2)—a general agent, a regional agent, and a local agent. Manufacturers found it difficult to regulate a market that was full of counterfeit goods in the 1990s. Thus, developing local agents was a way to monitor the market and avoid counterfeit goods. In the 1980s, after gaining autonomy in marketing, manufacturers had already set up their own local sales branches. They applied this to the agent system and replaced sales branches with local agents in the 1990s. Furthermore, manufacturers set up regional upstream agents to oversee local agents. This could prevent manufacturers from losing bargaining power with local agents, as local agents would gain power when their networks with local retailers were big enough. The tiers of agents were not necessarily partners in capital or alliance.Footnote 63

The apparel enterprises restricted the circulation areas of the agents. If their numbers and operating areas were not controlled, the agents could exploit retail channels without end, which caused unhealthy competition. Moreover, the emergence of large-scale agents enhanced their purchasing power; thus, manufacturers lost control of the circulation of goods. They always selected one regional agent for a single brand or for all their brands, and one local agent in a city or a province. The regional agents directed only the local agents, and the local agents could exploit only local retail channels; it was prohibited to deal with retailers in other provinces or cities. The local agent adjusted the allocation of commodities among department stores and directed the brands’ promotional activities. Therefore, the presence of only one agent in a local area ensured uniformity of individual products and promotional activities and avoided unfair competition from an oversupply of specific products.Footnote 64

However, the tiered and restricted-area agent system resulted in challenges for department stores. It caused apparel to traverse multiple layers of agents, and, thus, resulted in multiple delivery costs. Moreover, local agents’ uniformity in terms of products and promotions in local department stores prevented differentiation in a city or region. Furthermore, department stores encountered difficulties in expanding nationwide, because doing so required negotiations with several local agents.

In summary, the following five factors led to apparel enterprises’ low profit margins: (1) deduction from revenue by department stores; (2) growing promotional activities by department stores; (3) department stores’ buying power; (4) multiple layers of agents; and (5) deduction from revenue by agents. Low profit margins prompted apparel enterprises to increase the retail price or cut quality. Although product prices were generally high, their quality and design did not match these prices or the level of service provided by department stores. Furthermore, the tiered agents and their restricted circulation areas led to a second challenge: Department stores in a city or a region lacked differentiation in product line-up and promotion.

Changes in the Purchasing Patterns of Department Stores

To cope with these challenges, department stores began to abandon the joint-operation system, but the challenges of implementing new purchase models undercut their ability to maintain their dominant status.

Centralized Purchasing by Domestic Department Stores

Department stores encountered obstacles when they began their nationwide expansion in the second half of the 1990s. As the preceding analysis shows, the agent system was adverse to department stores’ cross-regional expansion. Under centralized procurement, headquarters operated the purchases for all branch stores by omitting the intermediary distribution of agents, and thus avoided repetitive negotiation costs with local agents caused by the restricted-area agent system. BW was the first department store in China to operate centralized purchases in 1996. In the period of preparing for opening its first two chain stores, Guangzhou Wangfujing and Beijing HaiwenWangfujing, the company negotiated with several local agents in Guangzhou and Beijing. To reduce procurement costs, they centralized the system.Footnote 65

The procurement center, located in a newly established retail headquarters, took charge of purchases for each branch store of BW with uniform merchandise quality management. Earlier, the general headquarters operated only one store, BW. However, with the expansion of chain stores and the expansion of other businesses, the businesses managed by the general headquarters had low efficiency, making organizational specialization necessary. The retail headquarters was one of five business divisions established by the organizational reform in 1996. The retail headquarters comprised procurement, delivery, marketing, accounting, and chain store set-up centers for chain store business.Footnote 66

Unimpeded communication regarding procurement demands between the procurement center and each store was necessary, but was difficult to achieve. Centralization meant a loss of autonomy in the entrance and admission fees for store managers and other decision makers in the stores. Thus, they predictably opposed this system and were not in favor of the procurement center. The stores always disobeyed the procurement center’s requirements, and in 1998 BWG was forced to upgrade the procurement center to be a higher-level organization than stores.Footnote 67

Furthermore, apparel enterprises objected to cooperating with centralized procurement, which also impeded centralized procurement. Agents were important business partners for apparel enterprises, which depended on local agents in exploiting channels. However, centralized procurement directly from apparel enterprises without passing through local agents damaged the agents’ interests. Apparel enterprises would have eliminated their dependency on agents if a large number of stores had operated centralized procurement, but only BWG and Dashang Group did so until the 2000s. Accordingly, apparel enterprises could not risk their relationships with agents while only a handful of centralized purchase enterprises existed. This led BWG to focus on persuading apparel enterprises to cooperate with their centralized purchasing in the decade from 2005.Footnote 68 Consequently, department stores lost their dominant status in the relationship with apparel enterprises, but found it possible to increase their buying power as more department store enterprises switched to the purchasing approach.

Department stores could reduce the resistance of operators of each store by organizational reforms, and even the loss of store operators’ autonomy with respect to brands’ entrance was not a problem for newly emerging department stores. However, department stores faced difficulty in obtaining cooperation from apparel enterprises with respect to centralized procurement, because the agent system had become embedded in the supply system and could not be quickly changed or eliminated; this hampered the department stores’ response to the irrationality of the two distribution systems.

Buyer Appearance in Department Stores

In buyer-driven purchasing, which is common worldwide, buyers’ discovery and purchase of products plays an important role in merchandise differentiation and avoids the low profit margins of the joint-operation system.

Since the entrance of Lafayette in 1997, some foreign department stores, such as I.T. (Hong Kong, which entered in 2003), Lane Crawford (Hong Kong, which entered in 2005), and NOVO Department Store (Hong Kong, which entered in 2006), have adopted this system. Department stores in mainland China, such as BW, which had already attempted the buyer system as a part of merchandising in the 2000s, had proprietary trading in apparel, food, accessories, and gifts.

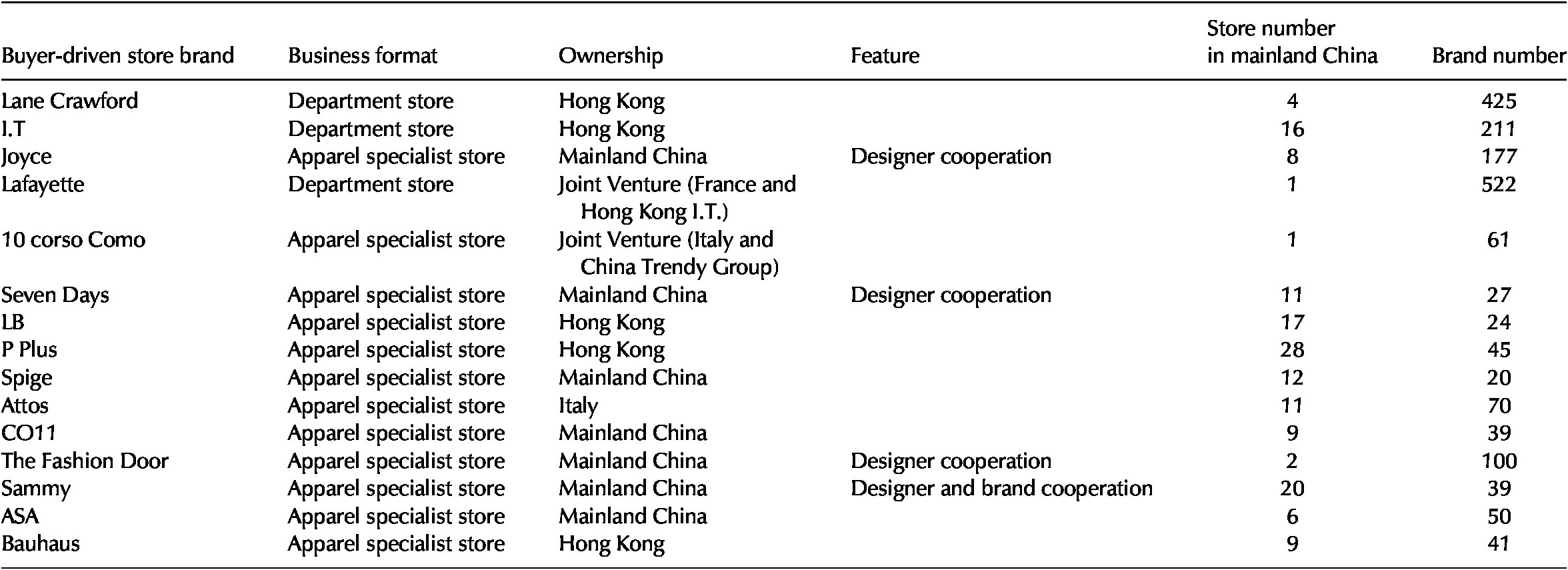

Compared with the smooth expansion of the subsequent buyer-driven specialty stores, multiple shutdowns and reopenings on the part of department stores indicated that they could not compete with the specialty stores. Lane Crawford re-entered six years after its retreat in 2001, as did Lafayette. Average same-store revenue growth rate of I.T was only 0.2 percent in fiscal 2017–2018, although it was the second-largest buyer-driven department store in China. Of the thirty buyer-driven store brands that emerged in China after 2000, twenty were specialty stores (Table 4).Footnote 69

Table 4. Main buyer-driven store brands.

Note: This table shows the fifteen largest buyer-driven stores in China in 2017. This ranking made by ISPO is based on annual sales revenue, store numbers, and brand impact.

Source: International Fachmesse für Sportartikel und Sportmode (ISPO), “Zhongguomaishoudianyanjiubaogao ji 30jiapaihangbang” [Research report of Chinese buyer stores and the ranking], accessed November 17, 2019, www.ispo.com.cn/news/detail/998JWwO.

This competitive landscape indicated that instead of the buyer-driven system in the Chinese market being inadequate, the department stores were not fit for the system; thus, it could not replace the joint-operation system. The accounts of buyer-driven department stores affirmed the system’s superiority to the joint-operation one, but their limited store numbers and short life cycle (as most stores shut down temporarily and reopened) restricted their human resources and curtailed their demand forecasting systems. The literature argued that, without sufficient demand, the buyer-driven talent training and demand forecasting system remained underdeveloped. The domestic department stores that adopted the buyer-driven system began to train their procurement staff and store staff as buyers, but this required time. Moreover, because department stores could choose which brands to stock but not choose individual pieces of merchandise in joint operation, they had little incentive to forecast fashion trends and market demand. Accordingly, they had no basis for analyzing market trends when the system became buyer-driven. Furthermore, few organizations could provide domestic data that were critical for the foreign department stores. On the other hand, the route of buyer-driven specialty stores also demonstrated department stores’ boundedness. The founders of buyer-driven specialty stores, who were also buyers, generally had experience either in apparel sales or design. They had a history with apparel enterprises and knew market trends. Joint-venture store brands, which generally cooperated with domestic apparel enterprises, could also use apparel enterprises’ knowledge of market demand.Footnote 70

The limitations on the number of stores that could be opened by any department store group imposed restrictions on reducing high procurement costs. Buyer-driven department stores had high procurement costs resulting from large varieties of merchandise needing a certain number of buyers. Especially in China, which has obvious consumption differences between provinces, buyer-driven department stores need more buyers to coordinate for different regions, creating high costs. Many merchants and academic observers claim that the high costs made them reluctant to expand their store numbers, which limited their subsequent ability to reduce costs. Meanwhile, specialty stores’ conditions showed the disadvantageous position of department stores; the procurement scale of the former was smaller and did not exceed 100 brands, as listed in the Table 4, and accordingly, their costs were lower.Footnote 71

These advantages promoted the expansion of buyer-driven specialty stores. Like direct-sale stores, they threatened both buyer-driven and joint-operation department stores.

Strategic Changes in Apparel Enterprises

To cope with the challenges of the apparel sector in department stores, apparel enterprises expanded other distribution channels and weakened department stores’ buying power by introduction of a multi-brand strategy and involvement in the capital of department stores.

Diverse Channels: Expansion of Direct-Sale Stores

The entrance of foreign fast fashion enterprises in the 2000s promoted the expansion of direct-sale stores. This resulted in a higher proportion of specialty stores in apparel retail alongside the emergence of domestic fast fashion brands.

Foreign fast fashion brands entered China by opening direct-sale stores from the early 2000s, including Mango (2002), Uniqlo (2002), ZARA (2006), and H&M (2007).They adopted the same retail format as was used in foreign countries, opening direct-sale stores. This format did not suit department stores, and thus the stores opened in shopping malls or as independent retail stores.Footnote 72

Without the limitation of agents and the joint-operation system, fast fashion developed without the problems that had plagued department stores. Without agent control, direct-sale stores eliminated intermediate costs. This also allowed fast fashion enterprises to differentiate the product line-up and promotional activities among their own stores in the same city according to store conditions. Furthermore, without the control enforced by the joint-operation system, the apparel enterprises had greater autonomy in store management and saved on admission fees by avoiding unjustified promotions.Footnote 73

Domestic fast fashion brands emerged at the same time through direct-sale stores. Their emergence was related to these foreign firms. Fast fashion, with its reasonable prices and fashion elements, was a departure from the department stores. Consequently, some existing apparel enterprises realized the advantages of fast fashion and turned to it, as did some newly emerging brands. A typical case was La Chapelle Fashion, the first to make a foray into fast fashion and direct-sale stores in 2002, having distributed its products through agents and joint operation earlier. The owner of La Chapelle was attracted to ZARA’s direct-sale store and fast fashion while he was in Europe, having been troubled at the time by low margins caused by the agents and joint operation.Footnote 74

This affected the status of department stores. With their transformation into fast fashion brands, existing apparel brands withdrew from department stores, adversely affecting product variety in department stores. For example, La Chapelle first withdrew from department stores in metropolises, and then from those in local cities.Footnote 75

Reduced Buying Power: Multi-brand Strategy and Involvement in Department Stores

Chinese apparel enterprises began to develop a multi-brand strategy from 1996. Besides reducing the cost of raw materials and boosting volume growth, this strategy had another aim: increasing their bargaining power with department stores. A multi-brand apparel enterprise stationed more than one brand in a single department store. It could continuously utilize the channels of existing brands while introducing new brands. Based on their higher bargaining power, multi-brand enterprises achieved better deals in terms of discounts and rental conditions. Consequently, apparel enterprises could enter retail stores at lower cost. These practices became a conventional part of trade relationships, and sometimes department stores concluded contracts with apparel enterprises for multi-brand operation. For example, Shanshan Group began exploiting multiple brands in 1996, and La Chapelle Fashion Corporation followed in 2004. The latter developed more than ten apparel brands targeted to women, men, and children.Footnote 76

Apparel enterprises weakened department stores’ buying power through cooperative relationships after 2004. According to an account of the first apparel enterprises to develop such relationships with department stores, apparel enterprises’ expansion in direct-sale stores plunged department stores into a crisis. In this context, department stores permitted the signing of cooperative contracts with large-scale apparel enterprises. At opening, new stores would prioritize cooperative apparel enterprises, and generally promised to ask for no admission fee. The contracts helped apparel enterprises save an admission cost and negotiation time, as they did not have to negotiate with department stores each time they entered a new store.Footnote 77

Furthermore, from the second half of the 2000s, large-scale apparel enterprises provided capital to department stores, aiming to reduce department stores’ buying power. This involved outright purchase or acquisition of shareholdings. For example, Metersbonwe Group, the top seller among domestic apparel enterprises, purchased a department store in Liaoning Province in 2008. Subsequent acquisitions of large-scale retailers highlighted department stores’ loss of buying power. These apparel enterprises gained priority entry to large-scale retailers. Jiangxi Mannifen Garment Company (now Huijie Group), Bosideng International Holdings (China’s largest down-apparel enterprise), and the Zhejiang Red Dragonfly Footwear Company became shareholders of the Dashang Group, which operated department stores in seventy cities in China, in 2010.Footnote 78

Conclusion

This study illustrated how and why department stores lost their dominant status in China’s apparel retail industry. With market reforms since 1978 supporting apparel enterprises’ marketing efforts, the state, apparel enterprises, and the commercial sector promoted the emergence and formation of two systems of apparel circulation: agent and joint-operation systems. However, certain irrationalities of the two reformed distribution systems in turn obstructed the continuous development of department stores and apparel enterprises. Both systems led to low margins for apparel enterprises, prompting them to raise prices and reduce quality. Furthermore, agents’ control on product line-up and promotion led to a lack of differentiation in department stores.

This forced department stores and apparel enterprises to evolve. Although department stores sought to change their disadvantaged status by reforming their purchasing patterns, their unexpandable business scale meant that they continued to face difficulties even after adopting the centralized purchasing and buyer-driven systems. Apparel firms developed diversified channels with the rise of fast fashion in China. These firms also weakened the department stores’ buying power by implementing multi-brand strategies and becoming shareholders of department stores.

Consequently, although department stores were still one important retail channel for apparel enterprises, they had lost their main retail channel status and their former buying power. The rapid expansion of apparel firms’ direct-sale stores reduced the prominence of department stores. Moreover, mutual interdependence of apparel enterprises and department stores negated department stores’ buying power. Eventually, the value chain changed from being driven by department stores to being driven by apparel enterprises.

The unique context made the decline of department stores in China different from those in the United States and Japan. Compared with American department stores, whose decline resulted from changes in consumption, competition with other retail business formats, and the industry’s pursuit of bigness, the irrationalities in the upstream value chain of the apparel industry were important factors in the decline of Chinese and Japanese department stores. The irrationalities of the reformed distribution systems between apparel enterprises and department stores caused the decline of Chinese department stores, while unstable production under globalization affected the competitiveness of Japanese department stores. Consequently, similar to the Japanese department stores, Chinese department stores also lost their competitiveness within the value chain of the apparel industry.

The significant development of Chinese commerce from the 2000s led to further reorganization of the retail industry. In particular, e-commerce has become an important factor for the entire retail industry, making it a crucial topic for further research. The successful development of e-commerce and its role in reorganizing the Chinese retail industry are issues that warrant extensive research to propose a comprehensive history of apparel retailing in China.