INTRODUCTION

‘The challenge of rebuilding regions in an environment of decentralization, pluralism and subsidiarity: the new ‘wickedly’ complex environmental paradigm.’ (Harris Reference Harris2007, p. 294).

Much has been written about governance reform by devolving powers to the local level through decentralization and community-based programmes, recognizing local management institutions, and increasing user participation and shared management responsibilities. This trend is usually traced to the 1980s and the disappointment with the performance of central governments. This was not always so. In the field of international development, for example, central governments were widely seen in the 1950s and 1960s as the main vehicle by which the development agenda would be carried out for the benefit of all citizens (Béné & Neiland Reference Béné and Neiland2004). The situation was similar in the resources area in which management was originally considered as a technical matter. Central governments were seen as the repository of the technical expertise to carry out the various tasks required in management, such as assessment of the status of renewable resources such as forests, wildlife and fisheries, and the calculation of the harvestable surplus, with natural resource professionals acting as independent, objective and efficient arbiters of human-environment relations (Bocking Reference Bocking2004).

By the late 1980s, however, there was a general disillusionment of stakeholders, development agencies and academics in the ability of centralized governments to plan, administer and implement development (Chambers Reference Chambers1983; Manor Reference Manor1999). Similarly, in the resource management area, serious concerns arose with centralized governments regarding their capabilities for the sustainable and equitable management of shared resources, or commons, such as marine and coastal resources, wildlife and forests (McCay & Acheson Reference McCay and Acheson1987; WCED [World Commission on Environment and Development] 1987). There was an increased interest in community-based resource management, and the ability of local, and in some cases traditional, institutions to manage local commons (Berkes Reference Berkes1989; Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990). Hence, decentralization, stakeholder participation and community involvement came to be considered as essential components of development and management.

The logic of this new thinking was compelling: bringing government closer to the governed allowed the people whose livelihoods and well-being would be affected by the decisions to have a say in those decisions. Effective user participation and problem solving at the lowest feasible level of organization, the subsidiarity principle (Kooiman Reference Kooiman2003), came to be considered as part of ‘good governance’. Advocated by Agenda 21 of Rio (1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, see URL http://www.un.org/esa/dsd/agenda21/), the subsidiarity principle was incorporated into Article A of the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 establishing the European Community, such that ‘decisions [are to be] taken as closely as possible to the citizen’ (McCay & Jentoft Reference McCay and Jentoft1996). Hence, by the 1990s, the governance focus had shifted to the local level, with almost all developing countries undertaking decentralization reforms (Ribot Reference Ribot2002). In place of top-down management, principles of ‘grassroots’ or bottom-up planning and management, such as public participation and co-management, became entrenched in various areas of environment and resources in both developing and industrialized countries (see for example Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Nielson and Degnbol2003; Borrini-Feyerabend et al. Reference Borrini-Feyerabend, Pimbert, Farvar, Kothari and Renard2004; Brunner et al. Reference Brunner, Steelman, Coe-Juell, Cromley, Edwards and Tucker2005).

Devolution of previously centralized powers in various areas of resource and environmental management is coming under discussion once again for a different reason: devolution has a mixed record and has not lived up to the original expectations. Devolution in the area of international development has not worked well in many cases (Ribot Reference Ribot2002; Béné & Neiland Reference Béné and Neiland2004, Reference Béné and Neiland2006). Devolution in resource management, in the form of community-based management, has worked in some cases but not in others. For example, the area of community-based conservation is very controversial with respect to whether it has or has not worked and why (Brown Reference Brown2002; Holt Reference Holt2005). Similarly, there is little agreement on whether shared resource management (or co-management) has worked, and on how to document success or failure (Berkes Reference Berkes2009). There is a complexity of factors in each resource management case that influences outcomes, whether the case represents decentralized management, top-down management or market-based management. Rather than dismissing devolution as an objective, attention is shifting to understanding what makes it work, and finding ways in which devolved management can be improved. Research is moving in a diversity of directions, some of the work focusing on management practices and some on theory.

Particularly promising approaches use the classic idea of adaptive feedback and learning-by-doing (Holling Reference Holling1978; Walters Reference Walters1986), combined with participation and co-management (Colfer Reference Colfer2005; Armitage et al. Reference Armitage, Berkes and Doubleday2007). Such approaches call for an interdisciplinary integrated view. They require a combination of approaches and tools from a variety of natural science and social science disciplines to synthesize knowledge and to develop a new resource governance field that has the capability to address emerging issues (Chapin et al. Reference Chapin, Kofinas and Folke2009; Cochrane & Garcia Reference Cochrane and Garcia2009). Such approaches have been developing in recent decades, as it is becoming increasingly clear that resource governance in a climate of complexity and uncertainty simply cannot be addressed adequately by using conventional approaches (Kates et al. Reference Kates, Clark, Corell, Hall, Jaeger, Lowe, McCarthy, Schellnhuber, Bolin, Dickson, Faucheux, Gallopin, Grübler, Huntley, Jäger, Jodha, Kasperson, Mabogunje, Matson, Mooney, Moore, O'Riordan and Svedin2001; Ludwig Reference Ludwig2001) and a single disciplinary perspective (MEA [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment] 2005; Polunin Reference Polunin2008).

Here I review interdisciplinary progress in the devolution of governance. The objective is to identify emerging concepts, approaches and frameworks, and to explore some of the implications and limitations of these approaches. The paper is based on a broad multidisciplinary literature that considers devolution and participation across a range of resources, coastal and marine, forests, protected areas, wildlife, watersheds and wetlands. Following a section on terminology related to devolution and cooperative management, the paper evaluates some of the experience with decentralization and co-management, leading to a focus on adaptive co-management. A descriptive model is used to explore some of the main elements of adaptive co-management, and the conceptual building blocks towards adaptive co-management.

DEVOLUTION AND COOPERATIVE DEVELOPMENT: CONCEPTS AND TERMINOLOGY

I am here concerned with understanding what makes devolution work and finding ways in which cooperative development and management can be improved. Devolution, as an objective, is not likely to be a ‘passing fad’ for two reasons. The first reason has to do with basic democratic principles: people should have a say in decisions that affect their well-being. Involving citizens and user-groups in making decisions and participating in management at the local level seems to be a normative position to which a vast majority of nation states and civil society groups subscribe, at least in theory.

The second reason has to do with the challenges of governance in a world of complexity and uncertainty. Managing ecosystem services and human well-being requires a great deal of information, both social and environmental, and the ability to make trade-offs (MEA 2005). Hence, an interdisciplinary approach is needed to deal with interacting ecological and social systems and their feedbacks, the integrated social-ecological system, to monitor resource availability, make allocation decisions and respond to environmental feedbacks. Social-ecological systems are complex adaptive systems with issues of scale, uncertainty, non-linear behaviour, self-organization and multiple stability domains (Berkes et al. Reference Berkes, Colding and Folke2003; Harris Reference Harris2007). Because of this, it is difficult for any one group or agency to possess the full range of knowledge and skills needed for environmental governance. Rather, the knowledge for dealing with social-ecological system dynamics, resource abundance at various scales, trends and uncertainties, is dispersed among local, regional, national and international agencies and groups.

In environmental governance, decision-making itself tends to be a complex process as well, rarely based exclusively on the recommendations of science. Various political, economic and administrative considerations go into decisions. Further, many contemporary resource and environmental problems are ‘wicked problems’ that do not lend themselves to conventional scientific solutions of the linear positivistic kind (Ludwig Reference Ludwig2001). Rather, they require the deliberative thinking of a wide circle of actors to identify the issue, possible approaches and policy options (Stern Reference Stern2005). Some of these problems, climate change being a key example, even question the established frame of the relationship between the citizen and the nation state (O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Hayward and Berkes2009). Thus, it is not surprising that governments are retreating from the position of the sole decision-maker. Instead, civil society and private actors are often involved in decisions, and the dividing lines between public and private spheres have become blurred, as in public-private partnerships. Such changes in decision-making are captured in the concept of governance.

Governance has been defined in several different ways but generally refers to the whole of public as well as private interactions to solve societal problems and create societal opportunities. It includes the formulation and application of principles guiding those interactions and care for institutions that enable them (Kooiman Reference Kooiman2003; Kooiman et al. Reference Kooiman, Bavinck, Jentoft and Pulin2005). As such, governance is the broader arena in which institutions operate and the various management-related processes take place. Governance includes some of the area previously covered by the terms policy and management. Governance is used as the more inclusive term, followed by policy as the less inclusive, and finally by management as the least inclusive term. Management is about action; governance is about politics, sharing of rights and responsibilities, and setting objectives and the policy agenda (Kooiman et al. Reference Kooiman, Bavinck, Jentoft and Pulin2005; Jentoft Reference Jentoft2007).

Governance is part of the context of devolution, given the growing international interest in a civil society in which the citizens are no longer treated as subjects but participants in governance. Governance emphasizes horizontal processes such as collaboration, partnership and community empowerment, in all areas of resource and environmental management, from fisheries to protected areas. Governance theory recognizes problem-solving and opportunity creation as a joint and interactive responsibility, and notes the importance of all parties (state, market and civil society) in this endeavour. Governance is not considered to be the something that governments do, but a broad responsibility to be shared, hence the expression ‘governance without government’.

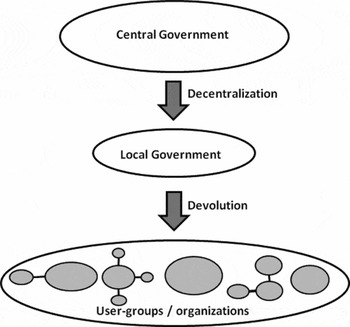

Devolution can be considered as a kind of governance reform, a mechanism to bring citizens, local groups and organizations into the policy and decision-making process. Some commentators use devolution, decentralization and other terms denoting participatory management interchangeably. Others prefer to use the term devolution as a general concept, and instead distinguish between democratic decentralization (any act in which a central government formally cedes powers to actors and institutions at lower levels in a political-administrative and territorial hierarchy) and deconcentration (or administrative decentralization involving the transfer of power to local branches of the same ministry of the central state) (Ribot Reference Ribot2002, p. 4; Larson & Soto Reference Larson and Soto2008). Yet others use decentralization as the umbrella concept and the terms deconcentration, delegation and devolution as different types of decentralization (Colfer & Capistrano Reference Colfer and Capistrano2005). The terminology in this paper follows Brugere (Reference Brugere, Hoanh, Tuong, Gowing and Hardy2006), and distinguishes between devolution (transfer of rights and responsibilities to local groups, organizations and local-level governments that have autonomous discretionary decision-making powers) versus decentralization (transfer of rights and responsibilities from the central to branches of the same government ministry) (Fig. 1). The point is that the effective control of resources used by the people requires the devolution of property rights to their institutions, whether they are customary institutions or local governments elected by them and accountable to them (Agrawal & Ostrom Reference Agrawal and Ostrom2001).

Figure 1 Decentralization and devolution in resource and environmental management. Adapted from Brugere (Reference Brugere, Hoanh, Tuong, Gowing and Hardy2006). In Ribot's (2002) terminology, decentralization (or administrative decentralization) refers to the transfer of power to local branches of the same ministry of the central state, and democratic decentralization is any act in which a central government formally cedes powers to actors and institutions at lower levels.

The terminology of cooperative environmental management also shows some complications and overlaps. Following Plummer and FitzGibbon (Reference Plummer and FitzGibbon2004a), three commonly used terms are associated with cooperative environmental management: partnership, collaboration and co-management. There are many similarities, some differences and considerable overlaps among these terms.

Partnership ‘is a dynamic relationship among diverse actors, based on mutually agreed objectives, pursued through a shared understanding of the most rational division of labour based on the respective comparative advantages of each partner’ (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2002, p. 21). The partnership literature may be divided into three categories (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2002). The normative perspective critiques top-down practice on the basis of equity, empowerment and democracy, calling for local involvement in governance. The second perspective, taken by government and business, uses partnership terminology in advancing neo-liberal policies and programmes in which government responsibilities may be privatized, as in public-private partnerships. The third perspective is instrumental, focusing on the function of partnerships, as in capacity-building (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2002).

Collaboration involves the pooling of resources by multiple actors or stakeholders to solve problems (for example Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990). Although often used as a synonym for partnership, collaboration emphasizes the process of interaction among actors. Central to collaborative interaction are issues of inclusion, power-sharing and joint decision-making, as in collaborative research which denotes an interaction of equals, rather than a subject-object relationship (Davidson-Hunt & O'Flaherty Reference Davidson-Hunt and O'Flaherty2007). Collaborative management is often used as a synonym for co-management. But in some circles, for example in some Canadian Federal government departments, collaborative management is used to denote an informal (non-legal) relationship, whereas the term co-management indicates a formal relationship of power-sharing.

Co-management is the sharing of power and responsibility between the government and local resource users. Most definitions of co-management specify the involvement of government as a counterpart, and a formal arrangement for power-sharing, at least as a memorandum of understanding (MOU). Many cases of fisheries co-management are backed up by law, as in Japanese (Takahashi et al. Reference Takahashi, McCay and Baba2006) and Chilean (Castilla & Defeo Reference Castilla and Defeo2001) coastal co-management examples; some protected area cases are backed up by MOUs (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. Reference Borrini-Feyerabend, Pimbert, Farvar, Kothari and Renard2004). There is no single universally accepted definition of co-management because there is a continuum of co-management arrangements with different degrees of power sharing and joint decision-making (Pinkerton Reference Pinkerton1989; Armitage et al. Reference Armitage, Berkes and Doubleday2007). These arrangements may be about a particular resource, a set of resources, or an area. Characteristically, co-management is a kind of collaboration or partnership that bridges scales, linking two or more levels of governance (Berkes Reference Berkes2009).

Each of these areas (partnership, collaboration and co-management), related to devolving management powers to local-level governments and other institutions, has its distinct but often overlapping technical literature. The mechanisms associated with these various ways to devolve powers, and the case study experience with them since the 1990s have been analysed by a large number of scholars and practitioners. Their experience provides insights for the way ahead.

DEVOLVING GOVERNANCE: DECENTRALIZATION AND CO-MANAGEMENT

Following the period of fiscal crises of the 1980s and the collapse of socialist economies since 1989, the majority of national governments in Africa, Asia and Latin America, encouraged by international bodies such as the World Bank, instituted decentralization reforms in a broad range of areas including development, environmental management, health care and education (OECD [Organization for Economic Cooeperation and Development] 1997; Manor Reference Manor1999). The experience with decentralization in the areas of environment and development has given rise to a large body of literature. According to the review by Larson and Soto (Reference Larson and Soto2008), much of this literature concerns forest resources and is based on the experience with cases from the developing world. Although the decentralization of forest governance has been defined and implemented in different ways around the world, the findings are strikingly consistent in showing a large gap between theory and practice (Capistrano & Colfer Reference Capistrano, Colfer, Colfer and Capistrano2005).

Decentralization reforms were undertaken to achieve participatory development and greater administrative efficiency, with benefits in terms of local empowerment, democratization and accountability, and also perhaps in terms of poverty reduction and resource sustainability (Table 1). The case literature shows that few of these potential benefits have been achieved. Ribot (Reference Ribot2002) pointed out that most decentralization reforms are characterized by insufficient transfer of powers to local institutions. In addition, the phenomenon of ‘off-loading’ is common; local jurisdictions have not been receiving the resources commensurate with their responsibilities (Pomeroy & Berkes Reference Pomeroy and Berkes1997). A great deal of evidence indicates that central governments are a major reason for the failure of decentralization reforms. Central governments use two main strategies to undermine the ability of local governments to make meaningful decisions: limiting the kinds of powers that are transferred, and choosing local institutions that serve and answer to central interests (Ribot et al. Reference Ribot, Agrawal and Larson2006).

Table 1 The gap between the theory and the practice of decentralization. Sources: Colfer and Capistrano (Reference Colfer and Capistrano2005), Ribot (Reference Ribot2002), Béné and Neiland (Reference Béné and Neiland2006) and Larson and Soto (Reference Larson and Soto2008).

At the local level, other forces conspire to frustrate decentralization goals. Uncertainties over the control of resources can precipitate new conflicts, rather than resolving existing ones. Well organized local elites tend to take advantage of the power vacuum while decentralization is in progress and consolidate their controls over resources. This works against equity and poverty reduction goals, and specifically against the well-being of the extreme poor and marginalized groups who tend to under-represented in local decision-making bodies (Colfer & Capistrano Reference Colfer and Capistrano2005; Béné & Neiland Reference Béné and Neiland2006). Lack of representativeness of decentralized bodies tends to work against accountability goals. As Ribot (Reference Ribot2002, p. 1) put it, ‘Transferring power without accountable representation is dangerous. Establishing accountable representation without powers is empty.’ A key recommendation is democratic decentralization, and the need to establish downward accountability of local institutions to the local people (Ribot Reference Ribot2002; Colfer & Capistrano Reference Colfer and Capistrano2005; Béné & Neiland Reference Béné and Neiland2006).

Regarding the objective of sustainable resource management outcomes, the record is mixed. The decentralization reforms of 1991 and 1998 for coastal and marine resources management in the Philippines facilitated co-management in the 1990s and integrated management in the 2000s (Pomeroy et al. Reference Pomeroy, Garces, Pido and Silvestre2010). Based on a tradition of community-based management in the 1980s, decentralization in the Philippines has helped improve fisheries management at the ecosystem and multi-jurisdictional level. Similarly, community-based coastal resource management programmes in the Philippines (and not necessarily decentralization itself) were perceived by coastal populations to be effective in empowerment and participation in management but not to any extent in livelihood improvement (Maliao et al. Reference Maliao, Pomeroy and Turingan2009). However, there are also cases in which devolution can lead to resource depletion, especially where decentralization fragments management responsibility for large resource systems. Jagger et al. (Reference Jagger, Pender and Gebremedhin2005) compared woodlot management in Ethiopia at household, subvillage, village and group of villages levels, and found scale-specific trade-offs between livelihood and conservation objectives. Local levels of management were better for empowerment and income generation, whereas management by groups of villages under local government was more favourable to sustainability.

In an overall evaluation of the decentralization experience, Larson and Soto (Reference Larson and Soto2008) noted that forestry decentralization has generally positive effects if there is user empowerment and downward accountability, and generally negative effects if decentralization fails to address equity concerns and accountability, or results in the extension of state control over local people and resources. In summarizing the findings from a large number of cases, Capistrano and Colfer (Reference Colfer2005, p. 311) emphasized the importance of the time scale for learning, adapting and capacity-building: ‘Decentralization takes time and thus is better implemented gradually, allowing for institutions and stakeholder groups to learn and to adapt. It requires building consensus through an open, transparent and inclusive process; participatory decision-making; institutional, technical and human capacity-building; provision of adequate financial resources and incentives for investment; tailoring objectives to local contexts; and developing the flexibility to adapt to different situations and changing circumstances’.

Further, Capistrano and Colfer (Reference Capistrano, Colfer, Colfer and Capistrano2005) pointed out that successful decentralization has been linked to secure resource tenure and/or traditional rights, and revenue and/or taxation powers of the local institutions to manage resources. The point about resource tenure is particularly interesting and is consistent with commons theory. Commons literature focuses on institutions and the question of who has control over resources (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990; 2005; Dietz et al. Reference Dietz, Ostrom and Stern2003), rather than the processes of decentralization per se. In emphasizing the significance of commons rights, Agrawal and Ostrom (Reference Agrawal and Ostrom2001) argued that decentralization is meaningful and effective only when governments devolve property rights to resources. An illustration is provided by Nagendra (Reference Nagendra2007) who showed that the security of land and resource tenure is important for sustainable resource management outcomes. She used a large data set of cases and 17 potential drivers of change, and found that two drivers, local tenure and local monitoring, were of central importance in achieving forest regeneration in Nepal, a country in which the Community Forestry Act of 1993 handed over access rights and management powers to user-groups in mostly degraded forest areas. Further, using a multi-country data set, Chhatre and Agrawal (Reference Chhatre and Agrawal2008) showed that local enforcement, which is key to commons governance, was closely associated with forest regeneration.

The literature on commons and co-management (which is largely based on commons theory) provides insights on how to proceed from decentralization to devolution of power, toward participatory development and resource management. Early representations of co-management focused on a two-link relationship between the government and local (or indigenous) resource users. Over the years, it has progressively moved from such simple interactions to one that regards multiple linkages and social relationships, in the form of networks, as the essence of co-management (Carlsson & Berkes Reference Carlsson and Berkes2005; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Ahmed, Siar and Kanagaratnam2006). The more detailed case studies of co-management show a wide array of actors and relationships, and illustrate the ways in which these relationships evolve and deal with a series of problems over the years (Armitage et al. Reference Armitage, Berkes and Doubleday2007). Much of this problem-solving occurs through informal learning networks comparable to communities of practice (Wenger Reference Wenger1998) and to ‘skunkworks’, informal social networks used by some organizations for generating innovative thinking (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2008). Various studies have identified the importance of leadership roles and key individuals in these networks (Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Folke and Hahn2004; Seixas & Davy Reference Seixas and Davy2008).

Networks are not only locally based. In the area of governance, they include polycentric networks that can cut across different levels of authority. Governance is said to be polycentric in structure if it has multiple and overlapping centres of authority (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Hahn, Olsson and Norberg2005). Such structures are inefficient in the narrow sense, but they allow for experimentation, and contribute to the creation of an institutional dynamic important for adaptive management. They also connect different levels of governance by providing communication channels for the various parties in multi-level institutions (Wilson Reference Wilson2006). These polycentric and multi-layered institutions improve the fit between knowledge, action and social-ecological contexts in ways that allow societies to respond adaptively to change (Lebel et al. Reference Lebel, Anderies, Campbell, Folke, Hatfield-Dodds, Hughes and Wilson2006).

Participatory development and management often emphasizes community-based institutions. However, purely community-based management has the same weakness as purely top-down government management; they both ignore the multi-level nature of institutional linkages (Dietz et al. Reference Dietz, Ostrom and Stern2003; Armitage Reference Armitage2008). Focusing only at one level, whether local, national or international, is inadequate design for governance policy (Young et al. Reference Young, King and Schroeder2008). A hypothetical coastal resource management case illustrates the linked multi-level nature of resource management at local, regional and national levels (Fig. 2). Local decision-making is obviously important but it is not independent of the other levels. Drivers originating at various levels, as well as at the international level, may have a profound impact on local resources and on local options. For example, the demand created by international sushi markets has led to the serial depletion of local stocks of various sea urchin species from around the world over a 30-year period (Berkes et al. Reference Berkes, Hughes, Steneck, Wilson, Bellwood, Crona, Folke, Gunderson, Leslie, Norberg, Nyström, Olsson, Österblom, Scheffer and Worm2006).

Figure 2 Three levels of institutions for fishery management in a coastal area, with land shown as darker areas. The local level may involve the rules-in-use (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990) of fishing communities, or the local fisher association, or a local/municipal government. Governance needs to address the linked multi-level nature of resource management at local, regional and national levels. Tuna-like pelagic fish passing through the region seasonally may require international-level governance as well.

The complexity of multi-level management and the unpredictability of the outcomes of interlinkages (as in the sushi example) are reasons to incorporate adaptive management into participatory development and resource management. Adaptive co-management merges the principles and practices of co-management and adaptive management (Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Folke and Hahn2004; Armitage et al. Reference Armitage, Berkes and Doubleday2007). Other authors have used the terms adaptive collaborative management (Colfer Reference Colfer2005), and adaptive governance (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Hahn, Olsson and Norberg2005; Brunner et al. Reference Brunner, Steelman, Coe-Juell, Cromley, Edwards and Tucker2005) to capture versions of this idea. Here the emphasis is adaptive co-management and the exploration of how devolution can be examined, starting with decentralization and trying to approach the target of adaptive co-management.

FROM DECENTRALIZATION TO ADAPTIVE CO-MANAGEMENT: A MODEL

Successful devolution of powers, in a way that the practice of decentralization is consistent with theory (Table 1), is certainly possible. Case studies seem to have produced more negative findings than positive, but that has more to do with the political ecology and unwillingness of some of the actors to make it work, rather than some inherent shortcoming of decentralization itself. The following model is roughly based on the conceptual model of Prabhu et al. (Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007) for adaptive collaborative management, and informed by Olsson et al. (Reference Olsson, Folke and Hahn2004), Pahl-Wostl (Reference Pahl-Wostl2009), Plummer and FitzGibbon (Reference Plummer and FitzGibbon2004b), Goldstein (Reference Goldstein2009) and Plummer (Reference Plummer2009).

The model is meant to be explanatory, not for prediction but for exploring plausible building blocks, or some of the key factors and considerations, on how a case might proceed from decentralization to adaptive co-management. It is based on the assumptions that there are no blueprints or packaged strategies that can be used for all cases, and that it is futile to look for some small number of key explanatory factors. Recent reviews (such as Plummer Reference Plummer2009) show that there are many variables that can play important roles. The task therefore is to understand the underlying complexity of cases to develop diagnostic methods (as a medical doctor would) to identify combinations of variables that affect governance (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2007), as done, for example, by Nagendra (Reference Nagendra2007) and Chhatre and Agrawal (Reference Chhatre and Agrawal2008).

There are three phases of the model which Prabhu et al. (Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007) initially based on the three forms of action of Habermas (Reference Habermas1981): (1) communicative action aimed at the generation of understanding, (2) strategic action aimed at dealing with relationships and (3) instrumental action. The model of Olsson et al. (Reference Olsson, Folke and Hahn2004) also has three stages, but the logic is different from Prabhu et al. (Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007), even though many of the elements are similar.

Although the Habermas conceptualization suggests a linear progression from communicative to strategic to material action, the three phases are not meant to be mutually exclusive, but rather overlapping, interconnected and cyclic, with many causal feedback loops among the three phases and within each phase.

Communicative action

The first phase of the model (Fig. 3) is centred on processes of communication aimed at reaching a shared understanding of issues and the creation of a shared vision among stakeholders or group members. It can start with the articulation of goals and objectives for resource use by each stakeholder, and the sharing and clarifying of world views and knowledge. This is not a top-down superficial ‘participation’ process as sometimes organized by governments, but a locally-controlled deliberative process that thoroughly examines the problem (Stern Reference Stern2005). The organization of the deliberative process to think through objectives, and to reflect on the values and the knowledge that pertains to resource management, requires good leadership. It may also involve dealing with conflicts among stakeholders. Informed by their experiences with community forestry projects, Prabhu et al. (Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007) saw the leader as a person who has a clearly articulated vision that is communicated with passion. The leader embodies certain values and can set standards for others; he/she has the capacity to inspire and empower others without telling them what to do.

Figure 3 A conceptual model of how a case might proceed from decentralization to adaptive co-management, through the phases of communicative action, self-organization (strategic action) and joint or collaborative (instrumental) action. Thick arrows show strong interaction. The three phases are not mutually exclusive but overlapping, interconnected and cyclic, with causal feedback loops among the phrases and within each phase. Adapted from Prabhu et al. (Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007) and others (see text).

Effective communication, above all, is a coordination task. There may be multiple perceptions of reality among the stakeholders. Assuming that the governance approach and practice will reflect the world views and knowledge of the participants, the sharing and clarifying of these will help coordinate the group members. It will also set the stage for the co-production of new knowledge that may be needed for management (Davidson-Hunt & O'Flaherty Reference Davidson-Hunt and O'Flaherty2007). In many cases involving aboriginal co-management, the ability to bring together government science and indigenous knowledge is key for co-management success. Different kinds of knowledge may be complementary with respect to scale. For example, the local people may have the best understanding of local forest conditions, but the government agency may have remote sensing data for the larger forest ecosystem. Communicative action can include the ability to forge partnerships to combine complementary knowledge, skills and capacities of different actors at different levels of organization.

The creation of a shared vision is of key importance for at least two reasons. First, the essence of adaptive management is to have an understanding of the system being managed and an explicit vision of the management goals (Walters Reference Walters1986). Second, a sense of purpose and shared meaning provides empowerment. Communicative planning is a search for meaning and vision (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2009). In some situations, a resource crisis is helpful as a trigger to bring management vision into focus, clarify objectives and galvanize action (Seixas & Davy Reference Seixas and Davy2008). It is no accident that some of the most robust cases of co-management were precipitated by crises. For example, the earliest documented fishery co-management arrangement, codified as the Lofoten Act of the 1890s, was the consequence of a particularly intense user-group conflict over cod that the Government of Norway was unable to resolve by top-down measures (Jentoft & McCay Reference Jentoft and McCay1995).

Self-organization

The second phase of the model, strategic action or self-organization, turns visions into plans that can be turned into action. It is about the development of relationships and involves the emergence of communities of practice, the creation of networks and the organization that is necessary for social learning. Wenger's (1998) communities of practice concept, which emphasizes learning-as-participation, is particularly appropriate for describing self-organization that leads to learning. Co-management cases followed through time show that effective cooperation develops through learning-as-participation in a variety of resource contexts, such as wetlands (Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Folke and Hahn2004), fisheries (Napier et al. Reference Napier, Branch and Harris2005), wildlife (Fabricius et al. Reference Fabricius, Koch, Magome and Turner2004); water (Pahl-Wostl et al. Reference Pahl-Wostl, Craps, Dewulf, Mostert, Tabara and Taillieu2007) and integrated management (Pahl-Wostl & Hare Reference Pahl-Wostl and Hare2004). Participatory approaches are central to social learning because they create the mechanism by which individual learning can be shared by the larger group and reinforced. In the process, social learning may proceed from simple single-loop learning to double-loop learning or learning-to-learn (Armitage et al. Reference Armitage, Marschke and Plummer2008).

Participatory learning helps the theory-practice linkage, or praxis, a spiral of action-reflection-action process. This results in the revision of strategic action through feedback learning. Hence, successive loops of learning-as-participation help combine elements of adaptive management with elements of co-management. Each cycle starts with observation and identification of problems and opportunities, leading to action-reflection and further action. Outcomes of successive plans need to be monitored and evaluated, followed by reflection, to lead to the next cycle. Each cycle provides new information for the next iteration, and also serves as a learning step, leading to co-management at successively larger scales over time (Berkes Reference Berkes2009). Such an approach seems to have informed many of the participatory forestry projects of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR; Colfer Reference Colfer2005; Prabhu et al. Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007).

Learning can emerge from the experiences of influential individuals or of the group itself (Agrawal Reference Agrawal2005), and it can also be triggered by action research. Lawrence et al. (Reference Lawrence, Paudel, Barnes and Malla2006) described participatory monitoring in a forest community in Nepal in which monitoring precipitated proposals for experimentation and an examination of the diversity of users’ needs. This, is turn, stimulated a more inclusive and wide-ranging understanding of local biodiversity values and livelihood needs. User-managers can learn, and networks are important as the site of social learning that can turn co-management into a continuous problem-solving process. They are also important for creating or co-producing knowledge (Davidson-Hunt & O'Flaherty Reference Davidson-Hunt and O'Flaherty2007), for combining resource management and development (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Ahmed, Siar and Kanagaratnam2006), and for finding partners for capacity-building that development projects often require (Berkes Reference Berkes2007).

Joint or collective action

Self-organization and strategic action sets the stage for the third phase of the model that is dominated by actions that have material results, such as a healthy ecosystem, livelihoods and human well-being. This phase is characterized by the emergence of new or revised rules-in-use, that is, institutions (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990) as a consequence of communicative action and the building of social relationships and networks. Institution-building goes hand in hand with social capital, a concept that captures four interrelated features: trust; reciprocity; shared rules, norms and sanctions; and connectedness in networks and groups (Pretty & Ward Reference Pretty and Ward2001). Social capital lowers the transaction costs of working together and facilitates cooperation. It gives people incentives to invest in collective activities, with the confidence that others will do so as well. This is a dynamic process: as collaboration becomes widespread, new possibilities come into focus beyond solving the original problem (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2009). Each round of problem solving leads to another. For example, in Lake Racken (Sweden), experience in dealing with lake acidification led to knowledge building and learning on a range of issues, with the group tackling one problem after another over a period of years. Increased learning resulted in a widened scope in problem-solving and increased capacity to experiment (Olsson & Folke Reference Olsson and Folke2001).

Closely related to institutions and social capital is capacity-building. It is a composite variable that has to do with a number of items useful to a group to achieve its goals. The internal relationships and trust can be built locally within the group. The expertise for other kinds of capacity building can be accessed through networks and may often involve multiple partners. For example, a sample of nine UNDP [United Nations Development Programme] Equator Initiative conservation-development projects were found to involve typically 10 to 15 partners, including local and national non-governmental organizations; local, regional and (less commonly) national governments; international donors; and research centres (Berkes Reference Berkes2007). These partners interacted with the community to provide a range of services and support functions related to capacity: raising funds; facilitating self-organization; business networking and marketing; innovation and knowledge transfer; technical training; research; legal support; infrastructure; and community health and social services (Berkes Reference Berkes2007).

All of this capacity-building and institution-building has to take place in an enabling environment, in the political, social and economic context; this is the space available to local actors to practice and develop their approaches (Prabhu et al. Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007). The ability to exercise power is particularly important, and is related to the kinds of powers devolved to the local level (Ribot et al. Reference Ribot, Agrawal and Larson2006). Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) emphasized the rights of resource users to devise their own institutions without being challenged by external governmental authorities, the minimal recognition of rights to organize, as a basic principle of successful commons management. Enabling environments for the successful devolution of powers, or the retention of existing local powers in the Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990, Reference Ostrom2005) sense, are likely to be found in societies with strong civil society traditions.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In trying to make sense of the devolution/decentralization literature and its relationship to co-management, the one clear finding is that most decentralization experiments seem to have failed to meet objectives. This is in part because the list of objectives has grown far beyond administrative efficiency of delivering services closer to the people, to include participatory development and democratization in general, along with empowerment, poverty reduction and resource sustainability. The failure is no doubt also owing to the undermining of decentralization reforms by central governments (no agency likes to give up power) and the ability of local elites to use the reforms to further their own interests (Ribot et al. Reference Ribot, Agrawal and Larson2006; Béné & Neiland Reference Béné and Neiland2006).

Yet, a second general finding is that there is also a great deal of evidence, in some areas and for some resources, that management powers seem to have been successfully devolved to the local level, communities empowered and resource conditions improved. There seem to be a great flowering of a diversity of experiments, such as the community forests of Mexico (Bray et al. Reference Bray, Merino-Pérez and Barry2005), and community-based wildlife management in southern Africa, from early experiences in Zimbabwe to the more recent conservancies of Namibia (Fabricius et al. Reference Fabricius, Koch, Magome and Turner2004). Some of these experiments are not directly related to the decentralization policies of the 1990s, but they do represent successful devolution of powers to the local level, with demonstrable improvements in the resource status as well.

There are other cases, however, clearly linked to the decentralization policies of the 1990s, with demonstrable positive effects on local control and forest regeneration. The two examples used in this review are both based on the International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) data set, collected from multiple countries using a standard set of methods (Nagendra Reference Nagendra2007; Chhatre & Agrawal Reference Chhatre and Agrawal2008). Given the importance of the local context and the many variables affecting the outcome in each case, IFRI studies illustrate the importance of having ‘large-n’ data sets to help eliminate some variables and combine the others in a diagnostic manner to arrive at indicators of successful commons use, both in terms of institutions and resources (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2007).

The present review uses a different way of proceeding. Rather than focusing on indicators, I have attempted to identify some of the major processes in moving from decentralization and devolution to adaptive co-management, chosen because it combines power-sharing with feedback learning. To do that I used the framework or conceptual model adapted from Prabhu et al. (Reference Prabhu, McDougall, Fisher, Fisher, Brabhu and McDougall2007) based on a rich set of community forest management cases. Without trying to account for every possible variable, the model is a useful way of summarizing some of the pre-conditions of devolution; deliberation for visioning; the importance of building social capital, trust and institutions; skills acquisition and capacity-building through networks and partnerships; and the significance of the action-reflection-action process leading to social learning (Fig. 3). For sceptics, there is a body of literature showing that such adaptive co-management is not simply a theoretical possibility, but something that works in a number of resource management situations in both developed and developing nations (Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Folke and Hahn2004; Colfer Reference Colfer2005; Armitage et al. Reference Armitage, Berkes and Doubleday2007; Pahl-Wostl Reference Pahl-Wostl2009).

What are the obstacles that prevent decentralized resource governance from reaching full potential? Any impediment to the various processes in conceptual model (Fig. 3) would consitute an obstacle. Prominent among these are the various actions of central governments and local elites to undermine decentralization reforms (Ribot et al. Reference Ribot, Agrawal and Larson2006). Other than issues of political ecology, two additional factors deserve special comment. One major impediment to the more extensive use of adaptive co-management is lack of appreciation of a multi-level polycentric partnership approach to governance. Since the 2000s, a great deal of attention has been directed at the notion that governance involves a number of institutional levels (Fig. 2), and action at any one level alone is not likely to work (Dietz et al. Reference Dietz, Ostrom and Stern2003; Lebel et al. Reference Lebel, Anderies, Campbell, Folke, Hatfield-Dodds, Hughes and Wilson2006; Berkes Reference Berkes2007; Armitage Reference Armitage2008; Pahl-Wostl Reference Pahl-Wostl2009). Poor conceptual understanding of multi-level institutions is one of the limitations to improved devolution. The architecture of multi-level institutions has only been explored recently (Young> et al. Reference Young, King and Schroeder2008). A second impediment is that professional education and practice in resource and environmental governance areas lag behind interdisciplinary progress and theory development, a subject too large to be addressed in this paper.

The practical implications of the feasibility of adaptive co-management are reflected in some of the emerging literature in environmental management (Chapin et al. Reference Chapin, Kofinas and Folke2009; Cochrane & Garcia Reference Cochrane and Garcia2009) but not (yet) in mainstream environmental management education and practice. However, a number of areas of resource and environmental management, including conservation planning, are taking a second look at devolution and local approaches, not because they have worked well in the past, but because of their untapped potential. For example, Bawa et al. (Reference Bawa, Seidler and Raven2004) argued that the best hope for conservation in a complex and rapidly changing world is to focus on locally driven approaches that (1) draw on local and traditional knowledge and practice as well as science, (2) generate fine-grained and locally adaptive solutions and (3) seek to increase human and social capital as well as natural capital. Initiatives that incorporate participatory approaches, conflict resolution, partnerships and mutual learning can be based on the empowerment of local communities and the strengthening of local institutions (Bawa et al. Reference Bawa, Seidler and Raven2004).

In conclusion, three points may be offered. First, effective devolution and making co-management work takes time (Napier et al. Reference Napier, Branch and Harris2005; Berkes Reference Berkes2009). The focus must shift from a static concept of management to a dynamic concept of governance shaped by interactions, feedback learning and adaptation over time. Partnerships and social learning help respond adaptively to change, and allow social-ecological systems to be resilient in the face of uncertainties in a globalized world in flux (Berkes et al. Reference Berkes, Colding and Folke2003; Folke et al. Reference Folke, Hahn, Olsson and Norberg2005; Armitage et al. Reference Armitage, Berkes and Doubleday2007). Second, sharing of governance responsibilities and ability to learn from experience is not only a concern for local-level or national-level institutions. It is a concern for all resource and environmental management institutions and, more to the point, for multi-level institutions. Governance involves the interaction, not only of many actors, but also of a number of decision-making levels; there is no one ‘correct’ level. Third, user participation and devolution of management powers tend to be associated with societies with democratic traditions and strong civil society. Long traditions of top-down rule are likely to lead to top-down decentralization processes as well, and to the failure of devolution. Democratic institutions develop slowly but can be nurtured and facilitated through local and multi-level capacity-building, institutional development and social capital.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many of these ideas in this paper were developed jointly with the adaptive co-management group (Derek Armitage, Nancy Doubleday, Ryan Plummer and others), the small-scale fisheries project group (Robin Mahon, Patrick McConney, Richard Pollnac and Robert Pomeroy) and the marine resilience working group (Carl Folke, Per Olsson, Jim Wilson, Terry Hughes and others). I thank Melanie Zurba for drawing the figures. My work has been supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and the Canada Research Chairs programme (http://www.chairs.gc.ca).