Introduction

The current study focuses on the role of consistency of use of morphosyntactic forms in child-directed speech (CDS) and its influence on acquisition of those forms by children whose first language is Irish, a fast-changing minority language in the context of virtually universal bilingualism (with English). The data for this study were collected within a relatively small geographical area in the west of Ireland in which Irish is the traditional community language. There are several such, mainly rural, areas in the Irish republic (known as Gaeltachtaí,) that are designated as officially Irish-speaking, and are intended to foster the daily use of Irish as a community language. All participants were being brought up within this community and had a local model of spoken Irish. The language in these communities is changing rapidly, and the major driver of this change is close contact with the dominant majority language, English. The changes can be observed from one generation to the next (Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016; Péterváry, Ó Curnáin, Ó Giollagáin, & Sheahan, Reference Péterváry, Ó Curnáin, Ó Giollagáin and Sheahan2014). This situation, although being highly detrimental for the preservation of Irish as a community language, offers a unique opportunity to examine the influence of exposure to specific morphosyntactic forms in CDS on children's use of those forms.

Sociolinguistics in Ireland

Although Irish has primary official-language status in the Constitution of the Irish Republic, and has official-language status in the legislation of the European Union, according to the Irish Census of 2016 (CSO, 2017) less than 40% of people living in Ireland reported that they could speak Irish, and only 4.2% reported that they speak Irish daily. In the Gaeltacht area along the west coast of Ireland, where the data for this study were collected, 66% of people reported that they could speak Irish, while 21.4% speak Irish daily outside the education system. Even in the Gaeltacht areas, children being brought up through Irish are, from very early on, exposed to varied amounts of English through their extended family, community, education, or different services that they attend (Hickey, Reference Hickey2007; Kallen, Reference Kallen2001). The exact age at which exposure to English begins, as well as the amount of exposure to English for children being brought up through Irish, is difficult to establish, mainly because, in addition to systematic exposure for which the onset can be clearly defined, children hear English from birth in non-systematic ways. Likewise, it is not easy to clearly specify exposure to Irish, given the dominant use of English in the general population of Ireland, frequent code-switching in the Irish–English bilingual community, differences in parental use of the language, and variable language use in education (Hickey, Reference Hickey2009; Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016; Péterváry et al., Reference Péterváry, Ó Curnáin, Ó Giollagáin and Sheahan2014).

A brief sketch of the Irish language

Irish is a Celtic language characterised by VSO word order. Grammatical information is expressed using: (a) free morphemes (e.g., archrann ‘on a tree’; igcrúsca ‘in a jar’); (b) suffixes (e.g., nouns: madra – madraí, ‘dog – dogs’; verbs: cuir-im ‘(I) put’; cuir-eann ‘(s/he/it) puts’); (c) preverbal particles plus initial mutation (e.g., cuirim ‘I put’, ní chuirim ‘I don't put’; an gcuirim ‘do I put?’); and (d) suppletion (tá ‘is’; bhí ‘was’). Further, a system of alternation between palatalised and non-palatalised morpheme-final consonants is used to mark case and/or number in nouns (crann ‘tree’ nom.singular, crainn, gen.singular and nom.pl). A further feature of Irish is the use of initial consonant mutations to mark grammatical information such as verb inflection, case, number, and gender agreement with prepositions, articles, and adjectives. Initial mutations include lenition and eclipsis/nasalisation. Lenition consists of a ‘weakening’ of the articulatory force applied to the initial consonant. Eclipsis is the process through which lenis segments become nasalised while fortis segments become lenis. For further examples of initial mutations see Müller, Muckley, and Antonijevic-Elliott (Reference Müller, Muckley and Antonijevic-Elliott2019) and of how they influence counts of mean length of utterance (MLU) in Irish see Hickey (Reference Hickey1991). In common with other literature on Irish, we use spelling conventions to indicate the process of initial mutation, rather than phonemic transcription, since the former is a more reliable and transparent indicator, for non-Irish speakers, than the latter. More detailed descriptions of the specific morphosyntactic forms examined in this study are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Modern Irish has three major spoken dialects – the Ulster dialect in the north, the Connacht dialect in the west, and the Munster dialect in the south – all of which have further dialectal variation. While in the written standard for Irish from 1958 dialectal differences were erased, the 2010–2011 review outlines a ‘dialect-neutral’ standard as well as three alternative dialectal patterns for written Irish. Irish educational authorities explicitly recognise local dialects as the target variety for preschools in Gaeltacht areas (for more details see Ó Murchadha, Reference Ó Murchadha2016).

Acquisition of Irish

Given the VSO word order and its morphosyntactic complexity, Irish is particularly interesting for the study of language acquisition. Based on the grammatical development of three children, Hickey (Reference Hickey1990b) adapted the Language Assessment, Remediation and Screening Procedure (LARSP) for Irish, defining the problem spaces inherent in the grammar of the language and their effect on acquisition. For example, the complexity of Irish inflections at word level and closed-class items were highlighted, while verbal nouns and verbal adjectives were found to be used early, followed by singular and plural articles. O'Toole and Fletcher (Reference O'Toole and Fletcher2012) found that closed-class words, potentially due to their complexity, were acquired when children were at a lower vocabulary size relative to other languages. In addition, despite the VSO word order putting the verb in a prominent position, they observed strong preference for nouns in vocabulary acquisition, similar to other SVO languages. Related to VSO word order, Hickey (Reference Hickey1990a) noticed that children often omitted initial auxiliaries. This pattern was also observed in CDS, both by Hickey (Reference Hickey1990a) and by O'Toole and Fletcher (Reference O'Toole and Fletcher2012). CDS in a mother–child dyad communicating in Irish was examined from a usage-based perspective by Cameron-Faulkner and Hickey (Reference Cameron-Faulkner and Hickey2011), confirming limited use of VSO structure in CDS. Importantly, this study found that structurally similar frames in CDS appeared to cluster into groups according to their communicative intent, indicating that both structural and communicative characteristics of input need to be analysed.

Language change

In the context of acquisition of Irish as a first language (L1) it is important to note that the language has been going through rapid change in the last few decades resulting in a different use of the language by each new generation (Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016; Péterváry et al., Reference Péterváry, Ó Curnáin, Ó Giollagáin and Sheahan2014). A comparison of the Irish spoken by young native speakers with that spoken by the generations of their parents and grandparents reveals significant changes. Examples of such recent changes involve: (1) phonetics (e.g., use of the retroflex [ɻ] instead of the flapped [ɾ] or trilled [r]); morphology (e.g., lack of vocative inflection: Seán instead of a Sheáin); and syntax (e.g., use of direct instead of indirect relative clauses: an fear atá mé ag caint leis instead of an fear a bhfuil mé ag caint leis ‘the man I that am talking to’); (2) non-canonical use or omission of initial consonant mutations (e.g., Gaeilge (nom.singular.fem) maith (nom.singular.masc) instead of Gaeilge mhaith (nom.singular.fem) ‘good Irish’; (3) frequent code-switching into English; and (4) frequent use of loans, idioms, and direct translations from English (Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016).

Bilingual language exposure

Exposure has been defined as “what is observable and measureable in a particular learning context” (Carroll, Reference Carroll2017a, p. 4). The literature also specifies ‘language experience’ (e.g., Paradis & Grüter, Reference Paradis, Grüter, Grüter and Paradis2014) and ‘input’ (e.g., De Houwer, Reference De Houwer, Grüter and Paradis2014; Paradis, Reference Paradis2017). In terms of bilingual language acquisition, it is possible to measure the quantity of exposure to each language specified as the cumulative exposure in situations where the child attends to that language. Quality of input has been defined in terms of different characteristics of the language that children are exposed to. Both quality and quantity of input have been shown to correlate with language performance in bilinguals (for a list of relevant studies, see ‘Supplementary material’ in Paradis, Reference Paradis2017).

Quantity of exposure

The quantity of exposure can be defined in terms of cumulative or relative language exposure variables. While cumulative variables express the absolute length of time a child is exposed to a language, relative language exposure specifies the proportion of exposure for each language (Paradis, Reference Paradis2017; Paradis & Grüter, Reference Paradis, Grüter, Grüter and Paradis2014). Using quantity of language exposure as a predictor of language learning has been criticised, in the sense that crude temporal units are not informative about language input (Carroll, Reference Carroll2017a). Specifying the length of time and presence of interlocutors does not necessarily indicate the type and the amount of communication during that time (De Houwer, Reference De Houwer, Grüter and Paradis2014; Grüter, Hurtado, Marchman, & Fernald, Reference Grüter, Hurtado, Marchman, Fernald, Grüter and Paradis2014). However, a significant number of studies have documented an association between the quantity of language exposure and language performance (Paradis, Reference Paradis2017). For example, several studies reported by Thordardottir (Reference Thordardottir, Grüter and Paradis2014) have indicated that the quantity of language exposure had strong influence on acquisition of grammatical morphology in that children with the lowest amount of language exposure significantly differed in the production of both vocabulary and grammatical morphemes relative to monolingual children and bilingual children with high language exposure.

Previous research suggests that the dynamic in the relationship between language exposure and language performance seems to be particularly sensitive in bilingual communities speaking a heritage or a minority language (Daskalaki, Chondrogianni, Blom, Argyri, & Paradis, Reference Daskalaki, Chondrogianni, Blom, Argyri and Paradis2019; Gathercole & Thomas, Reference Gathercole and Thomas2009; Nic Fhlannachadha & Hickey, Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2017; Thomas, Williams, Jones, Davis, & Binks, Reference Thomas, Williams, Jones, Davies and Binks2014). While most studies have established a correlational rather than a causal relationship between language exposure and performance in bilinguals (see Carroll, Reference Carroll2017a, Reference Carroll2017b, for discussion), it is still important, particularly in the case of heritage and minority languages, to estimate language exposure in quantitative terms.

Measures of quantity of input as defined above are usually obtained using parental questionnaires (e.g., De Houwer, Reference De Houwer, Grüter and Paradis2014; Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Hurtado, Marchman, Fernald, Grüter and Paradis2014), which provide useful information about children's language exposure (Paradis, Reference Paradis2017), but which also have multiple limitations. One of the problems is that language use cannot always easily be categorised as one language versus another (Carroll, Reference Carroll2017a). This can be particularly problematic in the case of minority languages like Irish, where use of code-switching and borrowings is frequent (Hickey, Reference Hickey2009; Ní Laoire, Reference Ní Laoire and Hickey2016; Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016). Further difficulties involve classifying loan words that might or might not be phonetically and grammatically adapted to the language in which the major part of the utterance is produced. Finally, parental ability to accurately estimate the amount of speech they use with their children can be questionable (Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Hurtado, Marchman, Fernald, Grüter and Paradis2014; Weisleder & Fernald, Reference Weisleder and Fernald2013). Nevertheless, parental questionnaires provide useful information about the dynamics of a family environment, such as information about the languages each parent/caregiver speaks and communication patterns at home (De Houwer, Reference De Houwer2007). Furthermore, in some cases parental questionnaires are the most feasible way of collecting information about a child's language exposure (Paradis, Reference Paradis2017).

The current study used parental questionnaires to gather information about the languages parents and other close family members spoke with the children, and to estimate the quantity of language exposure from birth and at the time of data collection, to ensure that all children in the sample had high exposure to Irish.

Input quality

Input quality refers to multiple factors describing the language that children are exposed to: for example, socioeconomic status (SES) and parental education (Golberg, Paradis, & Crago, Reference Golderg, Paradis and Crago2008; Place & Hoff, Reference Place and Hoff2011), native vs. non-native input (Cornips & Hulk, Reference Cornips, Hulk, Lefebvre, White and Jourdan2006; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2013), maternal self-rated proficiency in L2 (Chondrogianni & Marinis, Reference Chondrogianni and Marinis2011), engagement in extra-curricular activities, experience with media, and the diversity of interlocutors in a minority language (Paradis, Reference Paradis2017). Input quality can also be defined in terms of the amount of variation in the forms and use of morphosyntactic categories in the language environment (Gathercole & Thomas, Reference Gathercole and Thomas2009; Paradis, Reference Paradis, Nicoladis, Crago and Genesee2011; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Williams, Jones, Davies and Binks2014). Because the current study focuses on the acquisition of morphosyntax in a minority language that is rapidly changing, the most interesting aspect of the input quality is the consistency of use of specific morphosyntactic forms in the language of the parents’ generation.

Previously, Pires and Rothman (Reference Pires and Rothman2009) examined the influence of specific characteristics of parental language – the use of inflected infinitives – on language acquisition by their children. Comparing Brazilian and European Portuguese, they found that incomplete acquisition alone could not explain heritage speakers’ divergence in using inflected infinitives. They proposed a “missing input competence divergence”, referring to inconsistent use of morphosyntactic forms in the parental language (Pires & Rothman, Reference Pires and Rothman2009, p. 212). Similarly, the current study aims to compare presence of morphosyntactic forms in CDS and children's use of those forms.

Input quality in acquisition of morphosyntactic forms

Studies focusing on acquisition of morphosyntax have looked at factors related to consistency of usage of morphosyntactic forms in the language environment, but also at specific properties of forms such as type and token frequency, form-to-function mapping, and distributional properties of forms. Paradis, Nicoladis, Crago, and Genesee (Reference Paradis, Nicoladis, Crago and Genesee2011) found that production of regular and irregular past tense in English and French, by four-year-old French–English bilinguals living in Canada, was influenced by the type and token frequency of verb forms in each language. These findings were confirmed for English only with older children (Paradis, Reference Paradis2010). Similar results were found for French direct object clitics, also for older children (Paradis, Tremblay, & Crago, Reference Paradis, Tremblay, Crago, Grüter and Paradis2014). All three studies found that token and type frequency, as well as inconsistent form-to-function mapping, influenced the acquisition of morphosyntactic forms. The studies also found an interaction between the quantity of language exposure and the characteristics of the morphosyntactic constructions, in that use of some structures markedly improved with an increase in language exposure.

Rodina and Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2017) investigated grammatical gender acquisition among bilingual Norwegian–Russian children living in Norway, in comparison to monolingual Norwegian-speaking children. In both monolingual and bilingual children, the development of the Norwegian gender system was protracted, irrespective of the bilinguals’ language exposure to Norwegian and Russian. However, in the bilingual children, the quantity of Russian language exposure was a factor in both qualitative and quantitative differences in the acquisition of the (largely transparent) Russian gender system.

Research on Welsh, a minority language with English as the majority language, examined the acquisition of grammatical gender (Gathercole & Thomas, Reference Gathercole and Thomas2009; Thomas & Gathercole, Reference Thomas and Gathercole2007), which is expressed through initial mutations in the noun phrase and is a complex, opaque, and inconsistent system (Ball & Müller, Reference Ball and Müller1992). The studies found that soft mutation, which affects more Welsh consonants and occurs in more grammatical contexts, is acquired earlier than aspirate mutation, which has considerably fewer triggers and affects only a small subset of Welsh consonants (fortis plosives), and is inconsistently used in the adult language. This indicates that form frequency, consistency of applicability across a phonological system, and consistency in the use of morphosyntactic forms in the adult model, all influence acquisition. Both types of mutations were shown to be protracted in development (Thomas & Gathercole, Reference Thomas and Gathercole2007), implying that opacity of morphological paradigms prolongs the acquisition of morphosyntactic forms. Plural morphology in Welsh is another complex morphosyntactic system. The production of plurals in a single-word elicitation task indicated better performance with morphosyntactic forms that employed more overt phonemic changes (such as the use of productive endings, which are much more frequent) than with forms that involved subtle, word-internal phonemic changes (which apply to only a minority of Welsh nouns). As with gender acquisition in Welsh, acquisition of plural is gradual and protracted. Similarly to previous studies, interaction between characteristics of morphosyntactic forms and the quantity of language exposure was observed (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Williams, Jones, Davies and Binks2014).

Although not many studies have been conducted on complex and opaque morphosyntactic paradigms in Irish, the acquisition of gender marking was examined by Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey (Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2017). Similar to Welsh, gender marking in Irish is marked by initial mutation in the noun phrase (Nic Fhlannachadha & Hickey, Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2017; Stenson, Reference Stenson1981). Three types of gender marking were examined: (a) marking gender on a noun following the definite article; (b) gender marking on an adjective agreeing with the gender of a preceding noun; and (c) gender marking by means of initial mutations following the third person possessive <a> /ə/. These three categories of gender marking each have their own pattern of interaction between gender (masculine/feminine), number (singular/plural), and case (nominative/genitive). In addition, not all Irish word-initial phonemes are affected by initial mutation (see Müller et al., Reference Müller, Muckley and Antonijevic-Elliott2019, for further details). Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey (Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2017) found indications of incomplete and protracted acquisition of the Irish gender system, as well as interaction with the quantity of exposure. Participants were most accurate in producing the third person singular possessive with both animate and inanimate nouns, indicating that salience and functional load influenced the acquisition of the morphosyntactic forms marking gender in Irish. In addition to the morphosyntactic characteristics of the gender marking system in Irish, it is possible that, due to rapid language change in recent times, the use of different forms of gender marking in the language community is inconsistent, which would also hinder acquisition of this system. Similar findings were reported by Müller et al. (Reference Müller, Muckley and Antonijevic-Elliott2019), indicating that initial mutations marking particular morphosyntactic forms that were consistently used by parents in their CDS were acquired early, while those used inconsistently by parents were produced by children with less than 30% accuracy and had not improved by the age of five.

Theoretical perspective

We adopt a usage-based perspective where the structure of CDS and what children can extract from it is essential for language acquisition. Language acquisition consists of forming linguistic representations through extracting, storing, and processing lexically based constructions from the language children are exposed to, resulting in a mature linguistic competence conceptualised as a structured inventory of constructions at different level of abstraction (e.g., Lieven, Reference Lieven2014; Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003). Importantly, children are focused on the adult's communicative intentions as they attempt to comprehend the immediate utterance, and communicative function is the main basis for their linguistic generalisations over time. Cameron-Faulkner and Hickey (Reference Cameron-Faulkner and Hickey2011) examined CDS in Irish from the same perspective and found the existence of form–function islands where a frame maps onto specific communicative intent, but also frames that express multiple intents. In addition, structurally similar frames appeared to cluster according to their communicative intent. The study suggests that both the structure of the input and also its communicative intent need to be incorporated into linguistic analysis.

Research questions and predictions

The aim of the current study is to explore the link between the quality of input, defined as consistency and accuracy of use of specific morphosyntactic forms in CDS elicited through parents’ narratives, and their children's production of those forms in the narrative retell. Based on the literature, we expected that grammatical accuracy in children's narratives would be linked to the consistency and accuracy of use of the specific morphosyntactic forms in CDS, but that other factors related to the language structure and communicative function may also play a role. For want of a better term, we define ‘accuracy’ to represent compliance with published descriptions of the regional variety of spoken Irish (De Bhaldraithe, Reference De Bhaldraithe1977; Ó Curnáin, Reference Ó Curnáin2007), which are based on the language as used by native speakers several generations ago. The regional variety of Irish as spoken by the current generation of parents and young children has not been described in detail; thus the use of detailed published description is a pragmatic choice. In addition, comparison with the reference variety also gives important insight into which morphosyntactic features of the language have remained stable across recent generations, and which appear to be changing (see also Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016, for valuable insights). At the same time, we are aware of the importance of comparing children's language to current language use among proficient speakers as suggested by Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey (Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2019).

Method

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee at the National University of Ireland Galway.

Participants

Children

Samples of the language production of seventeen typically developing children aged 3;4–6;4 are analysed in this study (see Table 1). All participants were exposed to the local west of Ireland dialect from birth and had the average cumulative exposure to Irish of 92% (range 60–100%) and the average exposure at the time of data collection of 90% (range 74–100%). The children had no history of attending speech and language therapy and their parents were not concerned about their speech, language, hearing, or cognitive development. The children passed a hearing screening, and achieved a non-verbal score of no less than one standard deviation below the mean on the Core Performance subtests of the WPPSI-IIIUK (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2002), which was administered through Irish.

Table 1. Profile of child participants. The data are a part of a larger study presented in the doctoral thesis of Muckley (Reference Muckley2016).

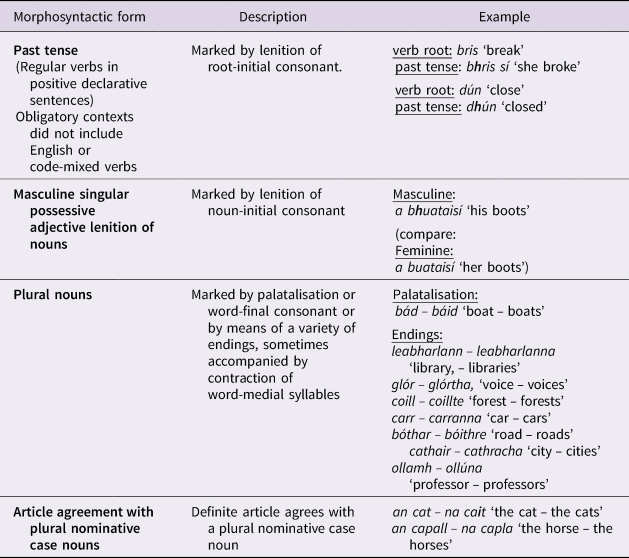

Table 2. Morphosyntactic forms consistently and accurately used by parents

Table 3. Morphosyntactic categories produced inconsistently and inaccurately in the parental narratives

The data presented here are part of a larger study reported in the doctoral thesis of Muckley (Reference Muckley2016) and also by Müller et al. (Reference Müller, Muckley and Antonijevic-Elliott2019). The current study, which focuses on child–parent dyads, includes only those children whose parents also produced language samples. There were no systematic differences in the demographics of the sample of children included in this study relative to the larger sample.

To estimate the quantity of exposure to Irish for their children, parents were asked to fill out two detailed diary-like questionnaires (partly based on Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, Reference Gutiérrez-Clellen and Kreiter2003, and also on Place & Hoff, Reference Place and Hoff2011), one referring to the exposure from birth and the other referring to the time of data collection. In both questionnaires, separate tables were included for parents to provide information on their child's typical weekday and weekend conversation partners. The tables included the following columns: (1) parent-chosen time-frames during the day (e.g., 7am–8am, 2pm–5pm, etc.); (2) child's conversation partners (granny, mom, dad, etc.); (3) information regarding the conversation partner (age, relationship to child, speaker status); and (4) estimated percentage Irish and English spoken by the conversation partner to the child. In the questionnaire referring to past language exposure, parents were instructed to start a new table when there was a change in the child's daily routine (e.g., starting at preschool). Parents were also asked about the amount of time their child spent attending educational facilities and childcare, as well as engaging in different social and other activities, and to specify the language used during that time.

On the basis of the information from the questionnaires, two indicators of exposure to Irish were calculated: (a) cumulative exposure from birth; and (b) current exposure. To estimate cumulative exposure we used a procedure similar to Unsworth (Reference Unsworth2013). First, we estimated the amount of time in educational settings / childcare and at home. All children attended education only through Irish; however, during that time they may have been exposed to variable amount of English through peer interaction. The exposure to Irish at home was calculated on the basis of the conversation partner and the activities. When two or more conversation partners were in the child's company simultaneously, the time was divided equally between conversation partners (Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, Reference Gutiérrez-Clellen and Kreiter2003). For each year, the cumulative exposure to Irish was expressed relative to the number of waking hours on typical days. Current exposure to Irish reflects time at data collection and includes children's language exposure in their home, family, and social contexts, as well as hours spent in formal education, which was through the medium of Irish for all children (however, it is important to stress that great diversity of language exposure in different early educational settings has been documented; Hickey, Reference Hickey2007, Reference Hickey2009).

Adult participants

Sixteen mothers aged 29–43 years (M = 36.39; SD = 4.12), all native speakers of the regional variety of Irish, participated in the study. Only one mother (N) had two children that participated in the study (C17 and C37) (see Table 1). This sample of parents is part of a larger study, reported by Muckley (Reference Muckley2016) and also Müller et al. (Reference Müller, Muckley and Antonijevic-Elliott2019). Four of those parents, whose children did not finish data collection or were excluded due to failing the hearing test, were not included in the current study. In addition, the larger study reported in full by Muckley (Reference Muckley2016) had a broader scope than looking at child–parent dyads and, due to restricted resources, parental narratives were not collected for every child.

Procedure

Narratives from both parents and their children were elicited using wordless picture book Frog, where are you? (Mayer, Reference Mayer1969).

Child narratives

Story retell was used in order to generate longer and more complex narratives than would have been generated through spontaneous story-telling (Merritt & Liles, Reference Merritt and Liles1989; Reilly, Losh, Bellugi, & Wulfeck, Reference Reilly, Losh, Bellugi and Wulfeck2004; Shapiro & Hudson, Reference Shapiro and Hudson1991). At the start of each data collection session the researcher (the second author of this paper) chatted with the child in Irish, in order to establish Irish as the language of interaction and to encourage children to settle in monolingual Irish mode (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean1989). The researcher then told the story, in the past tense, and asked the child to listen and look at the corresponding pictures. She then asked the child to retell the story in his/her own words while looking at the pictures. The researcher encouraged the child to continue telling the story by showing interest through facial expression and when necessary by giving neutral comments such as mmhmm?, agus ansin..? ‘and then?’, and occasionally repeating the final few words of the child's sentences. This procedure was repeated for the second story, custom-made by the second author, illustrated in a 15-page original picture-book. The second story was constructed as a continuation of story 1, but told in the present tense. It also provided the children with the opportunity to produce further examples of grammatical features present in story 1. Script and pictures for the second story are provided as Supplementary material to this paper (available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000919000734>). Each child's narration of the stories was audio-recorded using a high quality Zoom H1 digital recording device. The resercher involved in the data collection is a fluent speaker of the local variety of Irish. She is a speech and language therapist trained in language sample transcription and analysis. The elicitation procedure was standardised in that the resercher always followed the same procedure and told both stories following the scripts.

Parent narratives

Parental narratives were recorded approximately a month later, in the child's educational or childcare setting. At the beginning of the session each parent was given a few minutes to look through the Frog where are you? (Mayer, Reference Mayer1969) picture-book and then asked to tell the story to their own child(ren), who were present in the room. Parents were asked to tell the story in the way they would normally tell a story to their children. Further, parents were advised to allow their children to ask questions, make comments, and generally participate in the story-telling. The parents were asked to begin their story with the words uair amháin bhí ‘once … (there) was …’ or simply bhí ‘(there) was …’ in order to prompt a story told in the past tense. They were asked to tell the story in Irish because our aim was to describe their current use of Irish, and in particular their use of morphosyntactic forms. Therefore, it is possible that code-switching and the use of borrowings in the language sample were not entirely representative of their typical use of Irish (see Hickey, Reference Hickey2009).

Transcription

Inter-transcriber agreement was established by having a second transcriber transcribing six parental narratives (30% of the samples) and 24 of the children's narratives. Agreement was high for both the children's (M = 97.40; SD = 1.77; R = 93.33–100%) and for the parents’ (M = 98.13; SD = 1.33; R = 95.83–99.41%) transcriptions. Percentage of agreement between transcribers was calculated for the whole larger data sample rather than for only the 17 parent–child dyads reported here.

As mentioned earlier, the morphosyntactic forms identified in the parents’ narratives were compared with available descriptions of South Connemara Irish (De Bhaldraithe, Reference De Bhaldraithe1977; Ó Curnáin, Reference Ó Curnáin2007), which were used for the purpose of comparison, and expressed in terms of the proportion of tokens in each category that conformed to those descriptions (see Tables 4 and 5). We use the term ‘accuracy’ here as a pragmatic shorthand for ‘conforming to the reference variety’, but make no prescriptive implications.

Table 4. Comparison of parental and children's performances of morphosyntactic forms that parents produced consistently and accurately. All variables were analysed as the proportion of obligatory context occurring in the narratives.

Table 5. Comparison of parental and children's performances of morphosyntactic forms that parents produced with inconsistent accuracy. All variables were analysed as the proportion of obligatory context occurring in the narratives.

Based on the consistency and accuracy of morphosyntactic forms produced by the parents, forms were categorised into two sets: (a) those that parents used consistently and accurately (see Table 2); and (b) those that parents were not using consistently and accurately (see Table 3). The latter category included inconsistent use, as well as consistent omission of analysed morphosyntactic forms in obligatory contexts (obligatory contexts are, for the purpose of this analysis, defined in terms of the reference variety). All parents participating in the current study used the local west of Ireland dialect, and the observed inconsistencies were not the result of dialectal variations. The two sets of morphosyntactic forms were subsequently analysed in the children's narratives. Only those forms that were used in a sufficient number of obligatory context in parental narratives were included in the analyses.

The following forms were found to be consistently and accurately produced by parents (examples are presented in Table 2):

1. Past tense

In Irish, regular verbs beginning with a consonant are inflected for past tense through lenition of the initial consonant (in non-declarative and negative clauses, preverbal particles are also added). Thus, past tense marking is characterised by the relative simplicity of sound-alteration and at the same time carries a comparatively high functional load, as it can be the only indicator of time reference in a clause. If the initial mutation is omitted, the resulting form is the same as the root form which serves as the second person singular imperative, changing the intended meaning. Therefore, lenition marking regular past tense has specific communicative weight.

2. Possessive determiners

The third person possessive determiners, singular and plural, all have the form a /ə/ and need to be disambiguated for gender and number by initial mutation: the possessive determiner causes lenition of masculine singular, consonant-initial nouns, h-prefix of feminine singular vowel-initial nouns, and eclipsis of plural nouns. Therefore, the initial mutation carries relatively high communicative weight. We focused here on the third person singular masculine, since the other third person categories did not yield sufficient datapoints for analysis in our narratives.

3. Nominative plural of nouns

Noun plural is marked by palatalisation (systematic sound alteration of final consonants) or by means of a variety of endings. Masculine nouns ending in a non-palatalized consonant in the nominative singular create a plural by palatalization of the word-final consonant. Feminine nouns ending in a non-palatalized consonant in the nominative singular add –a in the nominative plural. Other nouns are characterized by a variety of endings, sometimes combined with vowel alterations and/or contractions. This system is relatively complex; however, it has high communicative weight, indicating the difference between singular and plural.

4. Article agreement with plural nouns in the nominative

Irish has no indefinite articles but only a definite article an (singular) and na (plural). The plural article na is followed by the noun in the plural form. Previous research indicated that children who are immersed in Irish L2 through education had a high number of errors related to the use of the definite article in agreement with noun number in a sentence repetition task (Antonijevic, Durham, & Ni Chonghaile, Reference Antonijevic, Durham and Ní Chonghaile2017).

The second set includes those morphosyntactic forms that parents use less consistently and accurately (see further examples in Table 3):

1. Prepositional case inflections directly following a preposition, and

2. Prepositional case following a preposition and an article

The majority of, but not all, simple prepositions in Irish cause lenition when directly followed by a noun (1), but in the variety of Irish under investigation here, eclipsis occurs when the noun is preceded by the definite article (2). However, there are a number of exceptions to this pattern related to individual prepositions (see Table 3). The communicative weight of the mutation is very low, given that the meaning is preserved in the absence of the mutation.

3. Gender marking of nouns in the nominative case following the definite article

The definite article triggers initial mutation on the following noun depending on its gender, case, and number, as well as its initial sound. In the nominative singular case, the initial consonant of feminine nouns is lenited following the article. Masculine nouns in the nominative have no initial mutation/gender marking if consonant-initial, but vowel-initial nouns have a t-prefix following the article. Masculine s-initial nouns have no initial mutations following the article, but feminine nouns have a t-prefix. This form has similar complexity of the inflectional paradigm as the genitive case marking (see below). Gender marking carries low communicative weight and also presents a contrast to English that does not mark the gender of inanimate nouns.

4. Gender marking in the genitive case following the definite article

For the genitive singular masculine, the article triggers lenition on a consonant-initial noun. For vowel-initial nouns there is no initial mutation, while s-initial nouns acquire a t-prefix. In feminine nouns, the article takes the form na and triggers the addition of an h-prefix for vowel-initial nouns, while there is no initial mutation for nouns beginning with a consonant (including s). Similarly to gender marking in the nominative, gender assignment in the genitive has low communicative weight and in addition is an opaque system.

Results

Data analyses involved pairwise comparisons of child–parent dyads for the two sets of mophosyntactic forms: those that were consistently and accurately produced by the parents (see Table 4) and those that were inconsistently or inaccurately produced by the parents (see Table 5). The proportion of instances in which a morphosyntactic form is used accurately is calculated relative to the number of obligatory contexts that each individual had created in their story. In cases where there were no obligatory contexts the value was returned as ‘missing data’ (marked as ‘?’ in Tables 4 and 5). When comparing production of morphosyntactic forms in the parents’ and children's narratives it is important to notice that parents were asked to ‘tell’ the story, and therefore that their choice of morphosyntactic forms was not influenced by syntactic priming from the story told by the researcher. However, in order to encourage children to produce longer narratives, they were asked to ‘retell’ the story previously told by the researcher.

The small number of parent–child dyads and relatively short narratives precluded any elaborate statistical analysis. In addition, in some cases the children did not produce any obligatory contexts for some of the targeted morphosyntactic forms and as a result we could not make any conclusions of how accurately they were using these forms in their daily language.

Examination of Table 4 indicates that there is an overall tendency for children to produce morphosyntactic forms with high accuracy when those forms are consistently accurately produced (a) by their own parent (consistency reflected by the proportion of accurately produced forms for each individual parent), and (b) across parents (consistency is reflected by the standard deviations of the means for each morphosyntactic form).

All parents and all children produced the past tense form with high accuracy (Mparents = 0.99, SD = 0.03; Mchildren = 0.96, SD = 0.05). In the case of the masculine possessive, despite the overall high accuracy (Mparents = 0.97, SD = 0.09; Mchildren = 0.89, SD = 0.19), there were three children, two of them in the youngest age-group, who had somewhat lower accuracy (C5, C6, and C28) irrespective of the fact that their parents used the form with high accuracy. There were two children (C18 and C23) who did not produce any opportunity to use this form. Plural nouns were in the main also produced accurately (Mparents = 0.98, SD = 0.05; Mchildren = 0.82, SD = 0.23), but there were four children who showed lower accuracy in using the form (C7, C33, C34, and C38), despite high accuracy in usage by their parents. With respect to agreement of plural article with plural noun, parents’ productions were uniformly accurate, and the overall accuracy for children was high (M = 0.83, SD = 0.34). Nevertheless, two children showed zero accuracy (C23 and C24) and one child did not produce any opportunities for the form (C18). When looking at variation in accuracy across parents, the standard deviations of the mean parental accuracy for each form indicated that there was almost no variation (SD 0–0.09).

The accuracy of parents’ and children's productions of morphosyntactic forms that were used inconsistently or inaccurately by parents are presented in Table 5. A comparison of the individual dyads indicates that, in those categories where the parents’ usage is variable and their accuracy rate is low, accuracy of the children's productions is also low, and in addition the children produce few obligatory contexts for the categories in question. In spite of this general trend, a few parents were highly consistent in accurately using particular forms (e.g., parents A, E, J, and H using prepositional case inflection following an article). However, their children still produced the same forms with low accuracy. Finally, in the case of genitive case inflections, all children produced a low number of opportunities and so did some parents (N, P, M, and T). High variability across parents in the accurate use of the forms presented in the Table 5 was indicated by the standard deviations of the mean parental accuracy for each form, ranging from 0.20 to 0.37.

Discussion

The main goal of the current study was to examine the relationship between the input quality and the acquisition of morphosyntactic forms in Irish, an endangered minority language. In particular, we focused on the relationship between the consistency and accuracy of use of specific morphosyntactic forms in CDS elicited through parental narratives, and the production of the same forms in children's narratives. It was predicted that children would exhibit a greater degree of accuracy when using the forms that were consistently and accurately produced by parents compared to those that were produced inconsistently or inaccurately. Given the scarcity of research on the acquisition of Irish morphosyntax, and our preference for usage-based accounts of language acquisition, we wanted to explore a range of morphosyntactic functions as used in natural language production which led us to employ a narrative task.

For pragmatic reasons we defined accuracy in terms of conforming to the established accounts of the regional variety of Irish as it was spoken by previous generations (De Bhaldraithe, Reference De Bhaldraithe1977; Ó Curnáin, Reference De Houwer2007). Those sources were used only as a point of reference and without any intention to be prescriptive. Because of the fast-paced language change, there is no detailed description of Irish language as it is currently spoken in the community that could have been used as a reference point (Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016). This situation led us to compare children's productions of morphosyntactic forms to both the available formal descriptions of the reference variety (which we labelled as ‘accuracy’) and to CDS produced by their parents who are proficient speakers of Irish as it is currently spoken in the community. Similarly, Nic Fhlannchadha and Hickey (Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2019) suggested that children's performance in fast-changing minority languages should be compared to the current use of language in the community rather than to “the ideal or formal standard variety” (p. 354).

Analysis of the children's and the parents’ narratives indicated a broad general pattern of high accuracy in the children's use of morphosyntactic forms that were consistently and accurately produced by parents. On the other hand, forms that were inconsistently or inaccurately produced by parents were produced with low accuracy by their children. While not all parent–child dyads showed this pattern for all morphosyntactic forms, the observed exceptions were not systematic in any way. All children participating in the study had high exposure to Irish, all of their mothers were native speakers of the local dialect, and all bar three of the fathers were either native or fluent speakers of Irish. In addition, all children attended education locally through Irish. Therefore, we can assume that the inaccurate use of particular morphosyntactic forms by the children was a consequence neither of their lack of exposure to Irish nor of any dialectal variations.

Furthermore, the variation in accuracy observed across the children was not systematically linked to their age. Although the age-groups were too small to compare using a statistical analysis, observation of Tables 4 and 5 indicated a potential link with age only for ‘masculine possession’ (i.e., possessive determiners). Other forms that parents produced inconsistently or inaccurately were not produced accurately even by the oldest children (aged 6;4), indicating protracted or incomplete acquisition as previously suggested by Péterváry et al. (Reference Péterváry, Ó Curnáin, Ó Giollagáin and Sheahan2014). In the case of ‘masculine possession’, although parents were highly consistent and accurate with this form, younger children showed lower accuracy compared to older children. This could indicate protracted acquisition, which in turn may relate to the nature of naturalistic language production: While the initial mutation accompanying the possessive determiner does indeed disambiguate gender and number, lack of the mutation is not likely to be problematic where the referent is clearly identifiable in the context of an utterance (either at clause level or beyond). Protracted acquisition of grammatical gender in Irish has already been indicated in the study conducted by Nic Fhlannchadha and Hickey (Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2017), which included older children (age groups 6–9 and 10–13 years).

The analysis of the morphosyntactic forms examined in the current study suggests that there might be factors related to the characteristics of the forms or their inflectional paradigms that could have contributed to their inconsistent use. Revisiting Tables 2 and 3 indicates that categories consistently produced by parents in CDS (and which the children have mastered even in the youngest age-group) are characterized by either low complexity or relatively high communicative weight, or a combination of both, while inconsistently or inaccurately produced forms exhibit a combination of high complexity and low communicative weight. For example, the past tense of regular verbs starting with a consonant is marked by the relative simplicity of sound-alterations, and at the same time the form has high communicative weight by identifying tense. This form was produced consistently and accurately by all parents and can be considered to be acquired even by the youngest group of children. On the other hand, gender marking in genitive case nouns following the definite article is considered to be redundant, and there is also clear internal evidence of gradual reduction of this form over time (Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016). The system of case marking across gender is complex and opaque in Irish, with the forms carrying low communicative weight. Additionally, gender marking is contrasted with English, where inanimate nouns are not marked for gender (Ó Catháin, Reference Ó Catháin and Hickey2016). A comprehensive study of the acquisition of grammatical gender using both receptive and productive measures conducted by Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey (Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2017) indicated protracted acquisition of this complex and opaque system. The study examined three types of gender marking (on a noun following the definite article; on an adjective agreeing with the gender of a preceding noun; on a noun following third person possessive which is gender-neutral) and found that participants were more accurate in marking gender on a noun following a third person possessive relative to the other two types. These findings suggested the importance of salience and functional necessity of the form, as marking gender agreement on the possessed noun that follows the gender-neutral possessive signals the gender of the possessor, which can be significant in communication. The study indicated interaction between functional necessity and structural complexity in the acquisition of a complex and opaque morphosyntactic paradigm (Nic Fhlannachadha & Hickey, Reference Nic Fhlannachadha and Hickey2017). The significance of the interaction of structural complexity and functional necessity in the acquisition of opaque and/or complex morphosyntactic paradigms has also been suggested by a number of previous studies (Gathercole & Thomas, Reference Gathercole and Thomas2009; Paradis, Reference Paradis2010; Paradis et al., Reference Paradis, Nicoladis, Crago and Genesee2011, Reference Paradis, Grüter, Grüter and Paradis2014; Thomas & Gathercole, Reference Thomas and Gathercole2007; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Williams, Jones, Davies and Binks2014).

Inconsistent use of certain grammatical features among the parents might indicate either incomplete language acquisition by the parents, or change in use of those forms during the lifetime of the parents, such that parents varyingly adhere to patterns of language use. Language change begins with variation in the spoken language of individual speakers and only continuously occurring variation leads to language change. While external factors such as contact with another language can initiate the change, changes are causally connected to the structural factors of a language (R. Hickey, 2014). We can further hypothesise that parental consistency and accuracy in the use of morphosyntactic forms was also influenced by the interaction of form complexity and communicative weight. Since we defined accuracy in terms of the reference variety (De Bhaldraithe, Reference De Bhaldraithe1977; Ó Curnáin, Reference Ó Curnáin2007), which represents the use of these morphosyntactic forms by previous generations, accurate and consistent use of some of the forms (past tense, noun plural) by the current generation of parents indicates that they are, at present, comparatively stable in the language use of the wider community.

A further factor influencing the production of morphosyntactic forms in children's narratives is almost universal bilingualism with English. Cross-linguistic influence on the acquisition of morphosyntactic forms has been observed in studies employing a sentence repetition task in Irish (Antonijevic et al., Reference Antonijevic, Durham and Ní Chonghaile2017) and other languages (Meir, Walters, & Armon-Lotem, Reference Meir, Walters and Armon-Lotem2016). Close contact with the morphologically simpler majority language English also could have contributed to change in the use of morphosyntactic forms such as, for example, gender marking, given that the gender of inanimate nouns in English is not marked. Finally, factors such as a possible redefinition of certain grammatical features in terms of sociolinguistic factors (for instance, formal versus casual speech) could have further influence on the acquisition of morphosyntactic forms.

In this study accuracy was defined in terms of compliance with the Irish grammar used by older generations. This was done because of the lack of a systematic description of the language currently used in the community of Irish speakers in the west of Ireland. In addition, this pragmatic choice also gave insight into the stability or otherwise of certain morphosyntactic forms in the current generation of parents. The current study is a step towards defining the current use of language in a community of Irish speakers. The significance of this goes beyond linguistic curiosity in that description of the currently used language standards is important when trying to identify and support children who might have developmental language disorder, and avoiding over-diagnosing in this process (for further details, see Müller et al., Reference Müller, Muckley and Antonijevic-Elliott2019).

Our study indicates that in addition to the quantitative measures such as cumulative amount of exposure and exposure at the time of data collection, it is necessary to define the quality of input in terms of consistency of use of specific morphosyntactic forms in CDS. In addition, the process of language change as it relates to the structural complexity of morphosyntactic forms and their communicative weight needs to be taken into account when examining minority and heritage languages.

The results of the current study indicate a link between the input quality, defined by consistency and accuracy in the use of specific morphosyntactic forms in CDS, and the use of those forms in children's narratives. It would be interesting for further research to examine representations of those forms using comprehension tasks, and also to explore the potential discrepancy between linguistic representations and performance.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material to this paper (available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000919000734>)

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the parents and children participating in the study. The study was funded by An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta (COGG).