INTRODUCTION

Russia's strategy for regional development has moved towards authoritarianism during recent decades despite simultaneous pressures to modernize economic structures and increase growth in regional agglomerations (Gel'man, Reference Gel'man2016; Klochikhin, Reference Klochikhin2012). Since 2010, the central strategy for regional development has involved a regulated creation of urban agglomerations (Kinossian & Morgan, Reference Kinossian and Morgan2014), legalization of industry clusters (Khayrullina, Reference Khayrullina2014: 91), and the construction of megaprojects, such as the Skolkovo Innovation Center (Kinossian & Morgan, Reference Kinossian and Morgan2014; Klochikhin, Reference Klochikhin2012). However, the results of ambitious development programs have fallen short of estimated performance levels (Khayrullina, Reference Khayrullina2014; Kinossian, Reference Kinossian2017a, Reference Kinossian2017b, Reference Kinossian2018). Overall, the sustainable economic development of Russian regions is disrupted by conflicting decision-making logics in policy programs (Kinossian, Reference Kinossian2013) and the inability of the political system to create favorable institutional conditions for entrepreneurship or address embedded structural problems in the economy (McCarthy, Puffer, Graham, & Satinsky, Reference McCarthy, Puffer, Graham and Satinsky2014). Similarly, authoritarian leadership practices remain embedded in Russian indigenous management styles (Balabanova, Rebrov, & Koveshnikov, Reference Balabanova, Rebrov and Koveshnikov2018; Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2007). These issues are also present in top-down cluster policies, as the projected urban agglomerations lack uniform legal and economic conditions for all participants and contain entry barriers for those who remain outside of the privileged state sector or lack political connections (Kinossian, Reference Kinossian2017a; Kinossian & Morgan, Reference Kinossian and Morgan2014: 15).

In the field of Russian economic geography, the modernization discourse and the initiatives to create innovation-based agglomerations promise a genuine reform of long-standing organizational and institutional practices. In this study, I investigate this mismatch between rhetoric and reality (e.g., Cliff, Langton, & Aldrich, Reference Cliff, Langton and Aldrich2005) and the ways in which the employed methods and strategies in Russian regional policy resemble past Soviet practices in economic geography. Understanding the role of historical background in contemporary economic reform is important since institutional differences in the level of (de)centralization can potentially explain why regional development models in some countries (e.g., China) appear more resilient and reformable than others (Qian & Xu, Reference Qian and Xu1993; Qian, Roland, & Xu, Reference Qian, Roland and Xu1999).

More generally, I aim to extend the theoretical understanding of how past organizational conditions can shape spatial governance structures through imprinted technological paradigms (Dosi, Reference Dosi1982; Zyglidopoulos, Reference Zyglidopoulos1999) and how localized, collective-level (Almandoz, Marquis, & Cheely, Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017) paradigms can dictate management outcomes (Filatotchev, Wei, Sarala, Dick, & Prescott, Reference Filatotchev, Wei, Sarala, Dick and Prescott2020; Geletkanytcz, Reference Geletkanycz1997), such as regional development paths, through regulative and social-normative mechanisms (Scott, Reference Scott2013). In this context, I highlight the role of historical legacy and founding templates as a source of persistent cultural-cognitive imprinting that can influence the development and institutionalization of spatial governance models.

Particularly, my analysis focuses on how the foundational organizational and cultural-cognitive characteristics (e.g., Baron & Hannan, Reference Baron and Hannan2002; Boeker, Reference Boeker1989; Harris & Ogbonna, Reference Harris and Ogbonna1999; Ogbonna & Harris, Reference Ogbonna and Harris2001) associated with the Soviet regionalization model, the territorial-production complex (TPC), developed into a dominant paradigm in the Soviet economic geography collective and how the outcomes of this imprinting process (Simsek, Fox, & Heavey, Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015) have re-introduced reproductive mechanisms into contemporary Russian economic geography and regional policy. My perspective draws on the theoretical work in organizational imprinting (Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcik2013), which provides a useful framework for understanding contexts that have undergone substantial transformations, such as postsocialist countries (Kriauciunas & Shinkle, Reference Kriauciunas and Shinkle2008). Although the negative effects of the Soviet legacy on the development of Russia have been studied extensively at a general level (e.g., Crescenzi & Jaax, Reference Crescenzi and Jaax2017; Hill & Gaddy, Reference Hill and Gaddy2003; Nykänen, Reference Nykänen2019) and in the management sector (e.g., Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011), the role of socialist imprinting in producing and mediating institutional influences in organizational collectives (Marquis Reference Marquis2003; Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009) has remained an understudied topic (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015). In this article, I address this gap and extend the theoretical perspective of imprinting to the field of economic geography.

The results of the study make three contributions to the literature on socialist imprinting. First, I highlight the role of field-level paradigms in directing the institutionalization of spatial governance structures and legitimate templates of action in hybrid organizational collectives. In particular, I demonstrate how the imprinting of socialist technological paradigms can continue to shape organizational collectives after radical environmental changes by maintaining, assimilating, and even amplifying imprinted characteristics through exaptation mechanisms (e.g., Marquis & Huang, Reference Marquis and Huang2010). Second, I propose that the ways in which paradigmatic imprints influence entity behavior can become reproductive if the imprinted entities continue to influence other entities and their configurations by coercive mechanisms (i.e., regional policies) (Scott, Reference Scott2013), thus turning the imprinted entities into imprinters (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015). Third, I highlight how the dynamics of imprinting and centrally imposed models of spatial governance can stand in contrast with regional-level institutionalization processes, contributing to variations in regional resilience and local institutional environments. In addition to these contributions, the article also provides contextual implications for the study of the Russian cross-cultural management environment (Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2007, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011) and the cultural diversity of within-country regions (Minkov & Hofstede, Reference Minkov and Hofstede2012; Peterson & Søndergaard, Reference Peterson and Søndergaard2014; Tung, Reference Tung2008).

The empirical content of this article is based on an extensive review and analysis of 163 articles in discipline-specific academic journals in Russia and the Soviet Union. These data are complemented with related secondary literature on Russian economic geography to construct a qualitative historical analysis (Gill, Gill, & Roulet, Reference Gill, Gill and Roulet2018) of the imprinting process. Methodologically, this ‘history in theory’ approach is valuable because of its potential to inform, guide, and validate constructs in organization theory (Kipping & Üsdiken, Reference Kipping and Üsdiken2014) and situate findings from context-specific qualitative analyses (e.g., Plakoyiannaki, Wei, & Prashantam, Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantam2019) into theoretical models.

The contents of the article are organized as follows. First, I review the existing studies of socialist imprinting and discuss how the study of organizational collectives and paradigmatic imprints contributes to this literature. Then, I present my empirical approach, key concepts and historical analysis, focusing on the imprinting process of the Soviet TPC model and its consequences in postsocialist Russia. Finally, I discuss the theoretical and contextual implications of my study and identify potential topics for further research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Organizational Imprinting in Postsocialist Countries

Organizational imprinting poses a theoretical challenge to the perspective that organizational differences derive from responses to changing environmental conditions (Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe and March1965). Rather, the concept of imprinting suggests that organizations are formed according to specific combinations of available resources during their founding and sensitive periods, and these elements may persist beyond the period of absorption (Johnson, Reference Johnson2007; Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcik2013; Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe and March1965). Marquis and Tilcsik (Reference Marquis and Tilcik2013: 199) define imprinting as a ‘process whereby, during a brief period of susceptibility, a focal entity develops characteristics that reflect prominent features of the environment, and these characteristics continue to persist despite significant environmental changes in subsequent periods’. Following this definition, the authors recognize three general phases of imprinting: First, a temporary restricted period, when organizations are susceptible to environmental influences; second, a powerful environmental impact on the focal entity during such a period; and third, the adoption of developed features during the sensitive period that persist despite substantial environmental changes. The process of imprinting is different from path dependence because of its emphasis on influential environmental conditions, defined periods of sensitivity and stability of acquired features, instead of singular historical events and progressive development towards the historically contingent direction (Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcik2013: 203).

Kriauciunas and Shinkle (Reference Kriauciunas and Shinkle2008) suggest that the process of imprinting is particularly relevant in the context of postsocialist countries, where an adequate and measurable change has taken place in the organizational environment due to a transformation of the political and economic system. At the firm-level, socialist imprints have been shown to adversely impact the ability of firms to adapt to new business environments (Kogut & Zander, Reference Kogut and Zander2000; Maksimov, Lu, Wang, & Luo, Reference Maksimov, Wang and Luo2017; Oertel, Thommes, & Walgenbach, Reference Oertel, Thommes and Walgenbach2016), engage in decentralized decision-making and outsourcing (Davis-Sramek, Fugate, Miller, German, Izymov, & Krotov, Reference Davis-Sramek, Fugate, Miller, Germain, Izyumov and Krotov2017), or change their sets of operating knowledge (Kriaucinas & Kale, Reference Kriauciunas and Kale2006). The key challenge of socialist imprinting for firms and socialist business organizations lies in the difficult adaptation process for new institutional conditions when their operative functions, strategy and resource allocation have developed according to the environmental conditions of the old institutional system (Greenwood & Hinings, Reference Greenwood and Hinings1996; Kogut & Zander, Reference Kogut and Zander2000; Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011; Shinkle & Kriauciunas, Reference Shinkle and Kriauciunas2012). Oertel et al. (Reference Oertel, Thommes and Walgenbach2016) argued that the degree to which firms and organizations experience the transition as ‘radical’ affects their capability to adapt to new conditions. Marquis and Huang (Reference Marquis and Huang2010) also found that this ‘exaptation’ (Andriani & Cattani, Reference Andriani and Cattani2016; Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcik2013), a mechanism by which organizations find their original problem-solving methods useful in new environments, may enable successful adaptation by using old strategies in new contexts without fundamentally revisiting organizational templates or identities. This mechanism may potentially explain why imprinting may result in complex and unpredictable manifestations when the surrounding environment undergoes significant changes (Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcik2013).

At the individual level, the length of exposure to communist ideology has been found to affect individual policy preferences (Alesina & Fuchs-Schundeln, Reference Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln2007; Pop-Eleches & Tucker, Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2014), work behavior and the attitudes of professionals (Banalieva et al., Reference Banalieva, Karam, Ralston, Elenkov, Naoumova, Dabic, Potocan, Starkus, Danis and Wallace2017; Puffer, McCarthy, & Satinsky, Reference Puffer, McCarthy and Satinsky2018), and entrepreneurial risk-taking (Banalieva, Puffer, McCarthy, & Vaiman, Reference Banalieva, Puffer, McCarthy and Vaiman2018) due to slow changes in cultural and institutional codes of conduct, consisting of internalized values, beliefs, and legitimate templates of action. Additionally, imprints deriving from socialist ideology can affect an individuals’ decision-making by filtering information (Marquis & Qiao, Reference Marquis and Qiao2018) or influencing the interaction between politicians and the business sector (Wang, Du, & Marquis, Reference Wang, Du and Marquis2019). These results imply that the role of socialist imprinting is significant in both policy-making and the accumulation and processing of knowledge, leading to the formation of cognitive structures, such as blueprints (Baron & Hannan, Reference Baron and Hannan2002), paradigms (Zyglidopoulos, Reference Zyglidopoulos1999), mental models (Porac, Thomas, & Baden-Fuller, Reference Porac, Thomas and Baden-Fuller1989), and cognitive maps (Suspitsyna, Reference Suspitsyna2005).

Socialist Imprinting in Organizational Collectives

The focus of this article on socialist-imprinted organizational collectives extends the indication that historically imprinted patterns have an influence on social forms beyond formal organizations (Marquis, Reference Marquis2003). Organizational collectives consist of geographical- and/or affiliation-based communities of actors whose membership provides them with social and cultural resources that shape their actions (Almandoz et al., Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017: 192; Brint, Reference Brint2001; Marquis, Lounsbury, & Greenwood, Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011). The distinction between geographical- and affiliation-based communities is that affiliation-based communities are designed and constructed through goal orientation, whereas geographical communities emerge from relationships created by spatial proximity (Almandoz et al., Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017). Following this definition, regionally and nationally bound collectives usually consist of affiliation-based communities, due to increased identification by means of shared living conditions.

In addition to the scarcity of studies on imprinting in organizational collectives (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015), I identify two additional reasons why this topic stands out as a fruitful area in the study of socialist imprinting. First, most of the organizational collectives in socialist countries represent distinct types of ‘hybrid collectives’ (Almandoz et al., Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017) whose actors exhibited characteristics of both geography- and affiliation-based communities. In socialist countries, affiliation-based communities also contain characteristics of geography-based communities because the ideological competition with Western countries at the national level decreased isomorphic learning (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983) and disincentivized field-level networking at the international level (Graham, Reference Graham1990: 60–63; Josephson, Reference Josephson1992). As a result, the hybridity of these communities makes them less exposed to external (cross-cultural) influences that could challenge legitimate templates of action within the community. This also implies that imprinting processes in organizational collectives that consist of hybrid communities are less vulnerable to ‘metamorphosis’ dynamics (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015) caused by exogenous contesting templates.

Second, imprinting acts as an important mechanism in mediating and shaping cultural-cognitive influences and dominant paradigms in different national contexts (Favero, Finotto, & Moretti, Reference Favero, Finotto and Moretti2016; Raynard, Lounsbury, & Greenwood, Reference Raynard, Lounsbury and Greenwood2013). These cultural-cognitive structures are not limited to the agency of individual entities (firms, organizations, individuals) but extend to a supra-organizational level in delimited organizational fields. Communities and organizational collectives play a critical role in mediating cultural values and influencing institutionalization processes through regulative, social-normative and cultural-cognitive mechanisms (Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009; Marquis et al., Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011; Scott, Reference Scott2013). Academic communities are particularly influential in this context as transmitters of knowledge and new ways of thinking into country-specific collectives (Filatotchev et al., Reference Filatotchev, Wei, Sarala, Dick and Prescott2020; Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009; Suspitsyna, Reference Suspitsyna2005). In socialist countries, these prescriptive roles are reinforced because of the centralized control of scientific and cultural organizations (Josephson, Reference Josephson2005; Kornai, Reference Kornai1992) and the interdependencies between economic and administrative organizations (Kornai, Reference Kornai1992; Tsoukas, Reference Tsoukas1994).

Imprinting and Regional (De)Centralization

Cognitive structures and paradigms (Dosi, Reference Dosi1982; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1962) may be utilized to identify societal problems, direct managerial attention, and legitimize templates of action. In the context of regional development, national industrial policies (Swords, Reference Swords2013), and spatial governance models are formalized examples of such templates that reflect and reproduce institutionalized conceptions regarding the degree of centralization and regional autonomy. Hence, the imprinting of such management templates involves not only the cultural-cognitive reproduction of paradigms but also the active dissemination of their prescriptions into the operation and configuration (Zyglidopoulos, Reference Zyglidopoulos1999) of target entities (i.e., regions, industries), which can become imprinted by the paradigm-induced management templates. This is particularly true in those socialist countries where the unitary government type and hierarchical organizational structures (Kornai, Reference Kornai1992; Qian & Xu Reference Qian and Xu1993) render management templates and dominant designs (Porac et al., Reference Porac, Thomas and Baden-Fuller1989; Zyglidopoulos, Reference Zyglidopoulos1999) less reactive to organization- and industry-specific conditions (Kogut & Zander, Reference Kogut and Zander2000). Although management templates may also produce organizational inertia in market economies, the higher levels of local discretion and more decentralized governance structures (i.e., in federal and confederate states) increase the maneuvering space and regional resilience (Hassink, Reference Hassink2011) of private firms and regional authorities.

Hypotheses

In line with the previous discussion, the empirical part of the study focuses on an analysis of the mechanisms by which the legacy of Soviet economic geography has had an impact on the contemporary post-Soviet economic paradigms and regional policies. After an initial survey of the historical development of this phenomenon by reviewing the existing secondary literature from different fields (economic history, economic geography, history of science, sociology, etc.) related to Soviet and post-Soviet regional development, I used two hypotheses to guide the further analysis of the study.

Hypothesis 1: An organizational collective of economic geography consisting of Soviet academics and executive economists in mutually reinforcing roles had a significant role in defining the system of regional planning in the Soviet Union.

Hypothesis 2: The Soviet TPC model played a dominant role in academic discourse, composing prescriptive rhetoric based on formal and theoretical rationalities (Kalberg, Reference Kalberg1980).

The first hypothesis implied that the Soviet spatial governance model did not directly emerge from the ideological roots of socialism but was rather construed and legitimized based on a collective-level paradigm within the specialized professional (hybrid) community. Thus, its conceptual content was not purely ideological but was also characterized by localized and historically embedded (Vaara & Lamberg, Reference Vaara and Lamberg2016) premises regarding centralization, spatial relations, and the functional form of economic structures, of which only the last element was essentially tied to socialism. The latter hypothesis further indicated that the Soviet spatial governance model became an institutionalized template within the localized organizational collective, with the consequence that its impact extended to the operation and configuration of other entities in long-term regional policy. Both of these hypotheses prompted a need to further explore the role of imprinting mechanisms in historical development and assess their potential legacy effects for the post-Soviet context.

METHODS

Data and Methods

To maintain methodological rigor and to remain cognizant of the contextual idiosyncrasies of the Soviet economic system (e.g., Tsoukas, Reference Tsoukas1994), I conducted an analysis based on historical methodology (Gill et al., Reference Gill, Gill and Roulet2018; Kipping & Üsdiken, Reference Kipping and Üsdiken2014). Specifically, this involved taking a critical and triangular perspective on different available data sources, which in the Soviet case are largely problematic due to discrepancies and restrictions concerning archival materials (Kragh & Hedlund, Reference Kragh and Hedlund2015; Markevich, Reference Markevich2005). These constraints encouraged me to follow a history in theory approach, where historical analysis is used to guide and theoretically inform the development and validation of organizational models (Kipping & Lamberg, Reference Kipping, Lamberg, Langley and Tsoukas2017; Kipping & Üsdiken, Reference Kipping and Üsdiken2014).

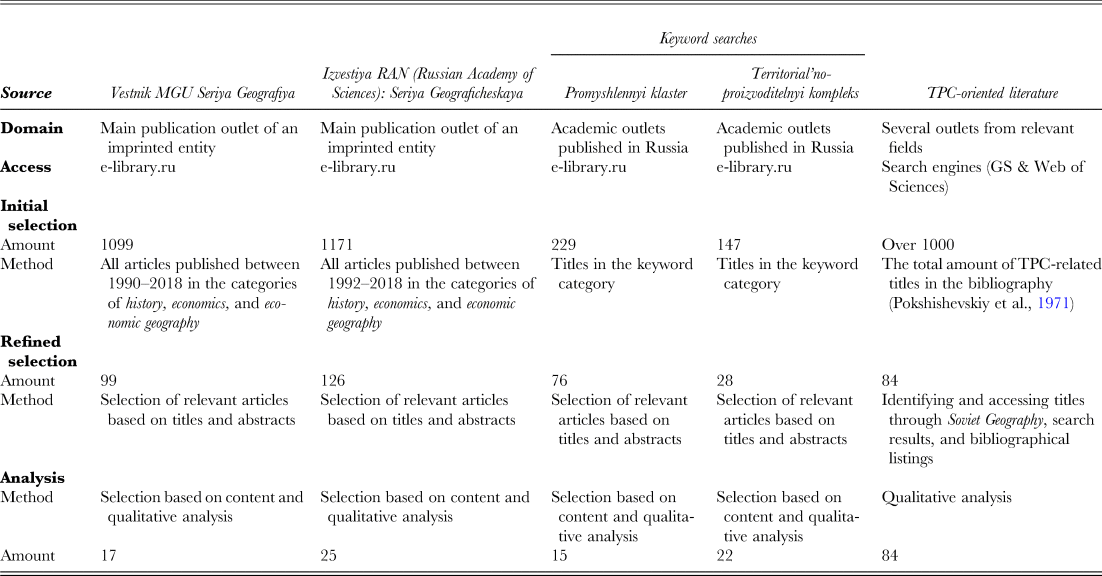

From this methodological position, I initially consulted a theoretical framework of organizational imprinting (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015) to organize the findings from the data (see Table 1) and to inform further steps of the analysis. The contents of these data can be roughly divided into two categories based on a demarcation between the Soviet and the post-Soviet periods. The first one includes sources, which I have used to study the period extending from the 1920s to 1990 to locate the sensitive period of imprint emergence (Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcik2013; Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015) and the institutionalization mechanisms following the maturing and metamorphosis dynamics of the imprinting process. The main body of materials in this section consists of published academic literature concerning TPCs and their role in economic geographical planning. These sources provided an extensive amount of qualitative observations regarding the use of rhetoric and discourses in legitimating organizational templates (Suddaby & Greenwood, Reference Suddaby and Greenwood2005). Overall, the extent of Soviet scholarship on TPCs was considerable. According to Pokshishevskiy, Mints, and Konstantinov (Reference Pokshishevskiy, Mints and Konstantinov1971), a complete bibliographical listing of TPC-related literature published by the Soviet State Institute of Scientific Information contained over 1000 titles, the majority of them published between 1966 and 1971. For this article, I utilized electronic access to the translated Soviet articles published in the UK-based Soviet Geography journal and complementary outlets (identified using search engines and bibliographical listings). These searches produced 84 articles, which I studied in detail, and I have synthesized my findings in the first section of the Results section.

Table 1. A summary of the review method and sources of articles used as data

The second phase of the analysis was to study post-Soviet regional development to evaluate how the TPC imprint evolved and transformed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. To select both relevant and compatible sources of data to study this period, I focused on literature from major institutional outlets in the field of regional economics and economic geography to survey how (and whether) the imprinted paradigms and characteristics associated with the TPC model were used in the post-Soviet organizational collective. The academic publishing system in Russia is strongly concentrated around the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAN) and University-based series of publications, which increases the impact and visibility of published articles among the readership (i.e., members of the organizational collective) and legitimizes certain discursive emphases as a source of collective paradigms. To analyze the level of organizational imprinting, discursive elements, and the conceptual change from the TPC-based paradigm (the Soviet period) towards a cluster-oriented paradigm (the post-Soviet period), I emphasized two geographical journals, Izvestiya Rossiiskoy Akademii Nauk: Seriya Geograficheskaya and Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta: Seriya 5. Geografiya as representatives of two of the most influential academic organizations: economic geographers from Moscow State University and the Russian Academy of Sciences. Between 1992 and 2018, the former outlet published a total of 1171 articles, and the latter 1099 articles in the categories of geography, economics, and history. Based on an iterative analysis of titles and abstracts, I identified as relevant 126 articles from the former and 99 articles from the latter. From among these articles, I selected 25 and 17 for the final phase of the analysis, in which the articles and their discursive elements were studied in detail.

To ensure that the sample of articles represented the relevant research domain of regional economic strategies and paradigmatic change, I conducted additional searches of the Russian electronic library database (https://e-library.ru) using the keywords klaster and territorial'no-proizvoditelyi kompleks, with 229 and 147 initial results, respectively. Out of these, I identified 76 and 28 articles as relevant based on an evaluation of abstracts and titles. I then refined this selection based on article contents, which narrowed the number to 15 and 22 titles for the analysis, complementing the findings from other categories. A total of 163 articles were analyzed. Table 1 presents a summary of the approach and materials used in this study.

Finally, I employed a wide selection of secondary literature (see references) alongside these sources and organized the results within a historical framework according to the criteria of transferability (Gill et al., Reference Gill, Gill and Roulet2018). This phase was important not only for constructing a richly contextualized and sufficiently trustworthy historical narrative of the studied phenomenon but also for presenting the results of imprinting in a comparative format with other studies on socialist imprinting. For the original analysis, this task involved a moderate amount of reanalysis of the collected data and refining of the original findings related to the imprinting analysis. In this respect, I am indebted to the Senior Editor and the anonymous reviewers who provided useful comments and new perspectives to complement the original phase of analysis. This has helped me to develop some of the identified mechanisms and issues related to the imprinting process.

Key Concepts

The hybrid collective of Soviet economic geography as an imprinted entity

The Soviet economic geography collective as a focal imprinted entity consists of Soviet academic and executive communities in the field of economic geography, thus representing a ‘hybrid collective’ due to its affiliation- and geography-based organization. This collective includes top- and mid-level Soviet academics, professionals, and decision makers who actively participated in the creation of regional economic policies in the Soviet Union (Konstantinov, Reference Konstantinov1968). The formal objective of this collective was to develop efficient mechanisms for organizing and coordinating regional economic production that conformed with the ideological and strategic aims of Soviet leadership. This task was divided into executive and academic roles, which were closely related, enabling active links between the theory and practice of economic geography. Throughout the Soviet era, economic geographical activities, consisting of industrial site selection, resource allocation, and industrial and infrastructural investments were coordinated by a centrally planned administrative organization under the control of the Soviet bureaucratic apparatus and the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Dellenbrant, Reference Dellenbrant1986; Kornai, Reference Kornai1992; Zaleski, Reference Zaleski1980). Unlike in market economies, where regional economic development is closely related to the behavior of individual firms, the centralized form of regional planning in the Soviet Union contributed to an organizational management system where the formal models of planning were combined with the informal practices of the socialist economy (cf. Kornai, Reference Kornai1992).

In addition to its executive role, the collective functioned as an academic community in the discipline of economic geography (Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966). The scientific system of the Soviet Union was hierarchical, and resource allocation and academic prestige were nested into central organizations, such as the Soviet Academy of Sciences (Graham, Reference Graham1967; Mirskaya, Reference Mirskaya1995) and Moscow State University. The former acted as a central scientific organization in the Soviet Union under the direct subordination of the Soviet Presidium (Gaponenko, Reference Gaponenko1995). Its dominant role in Soviet nonmilitary science allowed its leading members to operate as academic gatekeepers, maintaining a major influence over the legitimation of scientific paradigms. This effect was significantly reinforced during the Stalin era by the Soviet doctrine, which linked the scientific cognition of facts with the production of value judgments (Allyn, Reference Allyn and Graham1990), dichotomizing scientific theories into stigmatized and orthodox categories (Graham, Reference Graham1967; Josephson, Reference Josephson1992). In addition, the ideological monitoring of science and the dominant use of the Russian language in scientific outlets contributed to the relative isolation of Soviet academic communities from their foreign counterparts (Byrnes, Reference Byrnes1976; Gaponenko, Reference Gaponenko1995; Graham, Reference Graham1978, Reference Graham2001; Josephson, Reference Josephson2005; Rabkin, Reference Rabkin1988; Ransel, Reference Ransel2001; Suspitsyna, Reference Suspitsyna2005). Overall, these conditions strengthened the localization effect (Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009) of the studied collective.

The TPC model as an imprinted technological paradigm

In my analysis, I view the Soviet model of economic regionalization, defined as the territorial-production complex (TPC), as the main source of imprinted characteristics. Specifically, I conceptualize the imprinted content as a distinct type of a ‘technological paradigm’ (Dosi, Reference Dosi1982), which became an institutionalized and dominant template for regional planning in the studied collective.

Dosi (Reference Dosi1982: 148) defined technological paradigms as ‘sets of procedures, or definitions of the “relevant” problems and of the specific knowledge related to their solution’. Technological paradigms are hence prescriptive and direct the means and progress of technical change according to ‘technological trajectories’, which embody and are constrained by the assumptions and cognitive perceptions of technological paradigms (Dosi, Reference Dosi1982; von Tunzelmann, Malerba, Nightingale, & Metcalfe, Reference von Tunzelmann, Malerba, Nightingale and Metcalfe2008; Zyglidopoulos, Reference Zyglidopoulos1999). Like cognitive imprints, the influence of paradigms extends to the content, range and stability of the strategic choices of the imprinted entities (Fauchart & Gruber, Reference Fauchart and Gruber2011; Gruber, Reference Gruber2010; Koch, Reference Koch2011). Although Dosi's (Reference Dosi1982) definition is usually invoked to study groups or clusters of physical technologies (e.g., nuclear technologies), its implicit idea of employing a cognitive blueprint to solve predefined problems makes it feasible to use the concept in a study of Soviet ‘technologies of regional planning’. Importantly, this perspective distinguishes that ‘socialist imprints’ do not merely originate from ideological sources of socialism but also carry legacies of (bounded) management rationalities and past organizational responses to context-specific problems in complex institutional environments. Within the academic community of Soviet economic geographers, the theoretical framework of the TPC model acquired a dominant status as a scientific paradigm (e.g., Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1962). The essence of this view highlighted that regionally delimited production complexes were subject to national level requirements (Saushkin & Kalashnikova, Reference Saushkin and Kalashnikova1960) and composed ‘regionally organized solutions to national level production problems’ (Aganbegyan & Bandman, Reference Aganbegyan and Bandman1984). The employment of the TPC model as a scheme of regional planning, i.e., a technological solution to the problem of spatially organizing industrial production, extended its role to a technological paradigm. Thus, the TPC model effectively prescribed the choices and strategic directions of the technological trajectory in the Soviet spatial organization of production and neglected the development of alternative solutions.

Nikolay Kolosovskiy (Reference Kolosovskiy1969: 142–183) provided the orthodox definition of TPCs, considering them as ‘interdependent (coordinated) combination(s) of production enterprises and lodgings (population centers) either in particular territories (local complexes) or within the economic region or sub-region (regional complexes)’. This conceptualization regarded TPCs as functional units of regional planning, which acknowledged specialization and the associated economic gains of spatial agglomeration as an underlying source of legitimacy. According to Kolosovskiy (Reference Kolosovskiy1961, Reference Kolosovskiy1969), the organization of internal connections, vertical and horizontal linkages and production procedures took place in so-called (energy-) production cycles, which covered the production chain from energy resources to ready-made products. Vertical and horizontal linkages in the TPC production cycle were based on consistently recurring elements of production. From this perspective, the establishment and existence of regional enterprises that did not align with the centrally assigned type of industry specialization was thus delegitimated (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965). External linkages of TPCs were formal and served to connect TPCs with national markets. TPCs could also supply products to the local market according to the criteria of regional self-sufficiency (Karaska & Linge, Reference Karaska and Linge1978: 161). In sum, the TPC theory provided the Soviet collective with a formal and prescriptive methodology to systematically evaluate and develop economic regions, their industrial potential, and the evolutionary stage of development (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965).

RESULTS

Imprint Emergence and Dynamics of TPC Imprint During the Soviet Era

Imprint genesis and the social-normative origins of the TPC model

The period of imprint emergence (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015) and the antecedents of the TPC model imprinting can be traced to the origins of the Soviet economy in the early 1920s and the introduction of the official regionalization scheme in 1922. During this sensitive period, Soviet leaders and political economists faced a colossal and unprecedented management task: to develop and initialize a centrally planned economic system that accorded with the principles of socialism (Barnett, Reference Barnett2004; Erlich, Reference Erlich1960; Nove, Reference Nove1986) in an environment plagued by the devastating effects of the Civil War. As a response to these problems, the newly formed GOSPLAN (State's Planning Committee), under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, put together a scheme of economic regionalization for the GOELRO (State Commission for the Electrification of Russia) program. The GOELRO system consisted of 21 power-producing complexes, which served as a core for local grids and regional industrial concentrations (Coopersmith, Reference Coopersmith1992; Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966). The GOELRO program also set an initial economic blueprint for the industrialization associated with the interwar Five Year Plans (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965), despite the fact that its ambitions to revolutionize the electricity supply of the country fell short of the initial aims (Coopersmith, Reference Coopersmith1992). The subsequent GOSPLAN scheme of regionalization in 1922 explicitly introduced the idea that economic regionalization, i.e., the division of the nation into economic regions for planning and management purposes, outlined and prescribed the creation of economically integrated, centrally coordinated, and industrially specialized production complexes (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965).

These decisions provided the initial ‘motive force’ (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015: 293) for the formation of a hybrid collective of Soviet economic geography and the initial adoption of the TPCs as a fundamental unit of regional planning. Furthermore, these events and the institutionalization of these organizational forms provided a strong social-normative foundation for TPC imprinting. Lenin's active participation in the GOELRO program and his writings on regionalization and industrial production had a seminal influence on the development of Soviet academic discourses, constituting a strong founder effect on the imprinting process (Baron, Hannan, & Burton, Reference Baron, Hannan and Burton1999; Ogbonna & Harris, Reference Ogbonna and Harris2001). His views on the question of industrial location and the socialist forms of industry (Lenin, Reference Lenin1964) and the endorsement of economic geography as a scientific field (Lenin, Reference Lenin and Dalglish1918) were especially important in establishing an orthodox disciplinary discourse in the literature of Soviet economic geography (e.g., Kalesnik, Reference Kalesnik1971; Khrutschev, Reference Khrushchev1971; Pokshishevskiy, Reference Pokshishevskiy1966; Saushkin & Smirnov, Reference Saushkin and Smirnov1971).

The GOELRO program and Lenin's founder influence shaped the imprinting process in two important ways. First, these events instilled economic sciences to a directing role in the adoption of socialist regional policy (Graham, Reference Graham1992: 57) and brought together a community of economists and engineers interested in economic regionalization, marking the genesis of the Soviet economic geography collective. After the GOELRO experience, the collective was also involved in the planning and construction of large industrialization projects in peripheral regions (Holzman, Reference Holzman1957; Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1962, Reference Saushkin1966). Several influential members from this group also participated in institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006) to develop economic geography into a legitimate scientific field. For instance, Nikolay Baransky, a veteran revolutionary and a personal associate of Lenin, was active in setting up the chair of economic geography at Moscow State University in 1929 and becoming the editor of the first dedicated academic journal, Geografiya v Shkole, in 1934 (Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1962). Baransky himself was a firm proponent of the ‘regional approach’ in economic geography, and his criticism of several alternative theoretical views was likely linked to the way in which the Central Committee officially condemned these views as ‘leftism’ in the 1934 decree of the teaching of geography (Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966). Such an outcome during the most extreme years of hardline Stalinist terror (Applebaum, Reference Applebaum2003; Banalieva et al., Reference Banalieva, Puffer, McCarthy and Vaiman2018; Conquest, Reference Conquest1968) was likely to increase the social-normative effect of the inscribed orthodox paradigm within the collective.

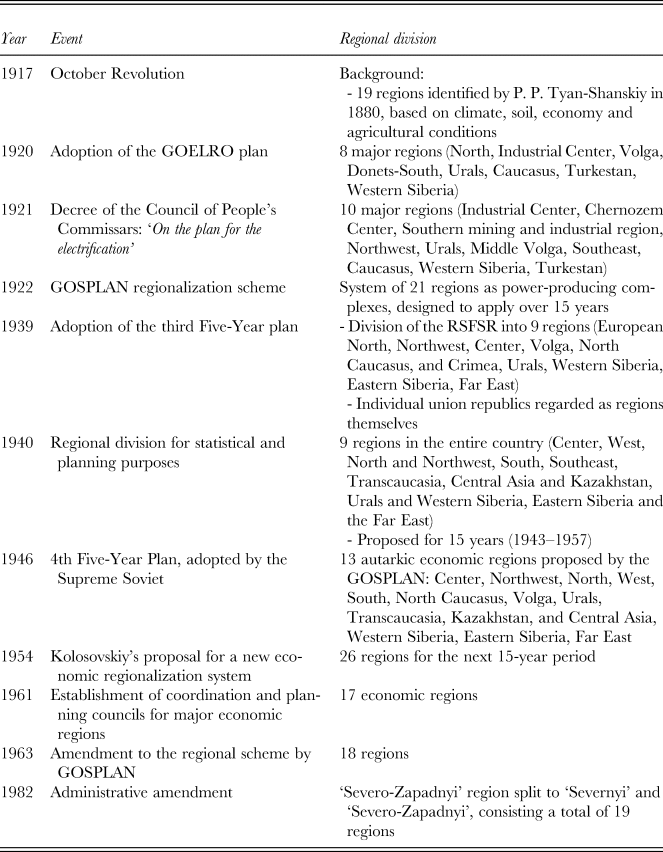

Second, the GOELRO period introduced the conceptual idea of TPCs as an integral unit of Soviet territorial planning (Nikol'skyi, Reference Nikol'skyi1975; Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966). The proposed system of regional power stations was associated with delineation of 8 economic regions (raiony; see Table 2), which represented the first national-level approach to regional economic development (Coopersmith, Reference Coopersmith1992). Although the economic regions were not detached from the prerevolutionary industrial formations, the GOELRO program marked an administrative shift, placing their technological trajectories under the control of central planners. Environmental conditions had a significant role in this part of the imprinting process. At the time, the Bolshevik government had neither established political control over the regions nor had a clear vision of how a planned economic system was supposed to operate (Barnett, Reference Barnett2004; Nove, Reference Nove1986). According to Coopersmith (Reference Coopersmith1992: 188–191), there were several alternatives to undertaking the electrification program and the Bolshevik leaders eventually opted for the method which would most effectively secure the role of the state in coordinating technological development. This objective later guided the consequent GOSPLAN scheme in developing the first regionalization blueprints for planning purposes, establishing a cultural-cognitive doctrine in the TPC paradigm. During the First and the Second Five-Year Plans (1928–37), this effect remained latent as the Soviet industrial policy predominantly emphasized planning by economic sector (Davies, Reference Davies1998; Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965; Zaleski, Reference Zaleski1980). The system of economic regions was primarily an administrative tool for spatial organization and planning of industrial production, with slight modifications to the original GOELRO plan (see Table 2). However, the regional approach to planning received greater official support in 1939 with the Third Five-Year Plan (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965: 469). The outbreak of World War II disrupted ongoing development plans, but the shifting emphasis towards regional planning and the TPCs continued after 1945, setting the stage for imprint amplification.

Table 2. Development of economic regionalization in the Soviet Union between 1917–1990 (Alampiev, Reference Alampiev, Dzieworski and Wrabel1963; Linge, Karaska, & Hamilton, Reference Linge, Karaska and Ian Hamilton1978; Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965; Kuznetsov & Mezhevik, Reference Kuznetsov and Mezhevik2017; Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966)

Imprint amplification and the creation of a technological paradigm

The outcome of these events in World War II affected the Soviet hybrid collective and increased the role of regional planning in central economic policies, amplifying the TPC imprinting from a latent social-normative template into a dominant theoretical framework in the Soviet hybrid collective. Particularly, I distinguish two interconnected lines of development which were linked to the imprinting process: 1) institutionalization of the TPC model into a prescriptive technological paradigm and 2) the consequent TPC policies and the interplay between the center and within-country regions (Peterson & Søndergaard, Reference Peterson and Søndergaard2014).

World War II and the invasion of regions in European Russia increased the strategic concerns of Soviet leadership (Bradshaw, Reference Bradshaw1991; Mellor, Reference Mellor1982; Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966) and led to a regionalization problem in the newly annexed East European territories (Zhirmunskiy, Reference Zhirmunskiy1965). The Fourth Five-Year Plan (1946–1950) included a new regional division that had been prepared by A. N. Lavrishchev (deputy chairman of the GOSPLAN) as a response to the demand for regional autarky and the novel threat of atomic warfare (Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966). Nikolay Kolosovskiy further developed this scheme in his seminal works (Kolosovskiy, Reference Kolosovskiy1961, Reference Kolosovskiy1969), arguing that a formal TPC model would allow the regional economic policy to solve these concerns and to integrate them into the economic benefits of regional agglomeration (cf. Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966). Being a former GOELRO project participant (Kalashnikov, Reference Kalashnikov and Kolosovskyi1969), Kolosovskiy linked TPCs to the original GOSPLAN scheme, considering that the real economic utility of the prior ‘production complex’ concept was limited by the primitive forms of the 1920s planning environment. Despite criticism for overlooking the ‘social dimension of production’ (Saushkin Reference Saushkin1966: 45), Kolosovsky's model received an endorsement from Nikolay Baransky, marking the institutionalization of the TPC model as the dominant paradigm for regional development within the hybrid collective.

In the early 1950s, the GOSPLAN and the Coordination and Planning Councils adopted the TPC model as the main template in the development of economic regions, and the 20th Party Congress in 1956 officially recognized it as the primary unit of Soviet regionalization. This precluded the possibility of considering or developing other types of models for the development or organization of regions, although voicing deviant views or paradigm alternatives became significantly safer after the death of Stalin in 1953. As an overall result, the Soviet economic regions followed a self-reinforcing trajectory (e.g., Sydow, Schreyögg, & Koch, Reference Sydow, Schreyögg and Koch2009) of development towards centrally defined technological trajectories and modes of industrial specialization. This shaped the development of local socioeconomic conditions, such as infrastructure, educational facilities, and the allocation of labor and capital resources (Demko, Reference Demko1987; Hill & Gaddy, Reference Hill and Gaddy2003; Udovenko, Reference Udovenko1978).

By the 1970s, the TPC imprint had amplified into a dominant institutionalized paradigm in Soviet regional planning. Occasional critical notes on the model (e.g., Alampiev, Reference Alampiyev1960; Moshkin, Reference Moshkin1962) had failed to reach sufficient momentum to introduce radical changes to the paradigm, and most scholars maintained the paradigm by developing or reinterpreting theoretical and functional elements of the template (Lis, Reference Lis1975; Privalovskaya, Reference Privalovskaya1979; Probst, Reference Probst1977) without questioning its foundational principles or underlying assumptions (Pokshishevskiy, Reference Pokshishevskiy1979). The Central Committee had officially initiated construction projects of new TPCs in its Basic Guidelines for the Development of the National Economy in 1976–80, which cemented the position of the model as the principal economic geographical model and as a practical planning tool for the rest of the Soviet period (Linge, Karaska, & Ian Hamilton, Reference Linge, Karaska and Ian Hamilton1978). The Soviet articles analyzing the prospects of the TPC plans from this period (e.g., Kosmachev & Losyakova, Reference Kosmachev and Losyakova1976; Shotskiy, Reference Shotskiy1976; Sochinskaya, Reference Sochinskaya1977) reflect a consensus regarding the role of the TPC model as an integral part of the projected technological trajectories.

Despite the role of TPC imprinting in defining the dominant technological paradigm at the central level, the impact of Soviet regional policies on emerging structures and organizational configurations at the regional level was only partial. This was caused by the dual effect of localized ethnic and cultural-cognitive conditions and the role of regions in composing (and thus potentially threatening) the social-normative legitimacy of the communist system. Despite centralized control of the national economic system, Soviet planners were unable to legitimize their social-normative conception of the utility of economic regionalization over ethnic or national boundaries at the regional level. Instead, the regions and national entities (Soviet republics) were occasionally able to resist and influence central policies through informal bargaining procedures (Dellenbrant, Reference Dellenbrant1986; Kornai, Reference Kornai1992) contrary to the aims of the TPC paradigm. Over time, the different perspectives and power politics over conflicting views of development manifested in shifting preferences between different allocation logics (Nykänen, Reference Nykänen2019), contributing to a skewed industrial distribution (Hill & Gaddy, Reference Hill and Gaddy2003; Markevich & Mikhailova, Reference Markevich, Mihailova, Alexeev and Weber2013).

The resilience of regions in resisting central policies originated from the initial imprint environment. The original GOSPLAN regionalization scheme in 1922 had mentioned the role of cultural and technological endowments as the basis of regional division by aiming to develop the assets and working skills of the local population in accordance with regions’ industrial specialization (Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966). Additionally, Soviet leaders recognized that the centralized scheme of regionalization required normative legitimation from regional actors (Harris, Reference Harris1999). Lenin himself considered it necessary to associate the regionalization program with propaganda campaigns to stimulate the interest of provinces to support the scheme (Saushkin, Reference Saushkin1966: 11). This concern became an explicitly stated policy known as the Marxist-Leninist doctrine of regional equality (Baransky, Reference Baransky1956; Dellenbrant, Reference Dellenbrant1986; Lavrishchev, Reference Lavrishchev1969; Rodgers, Reference Rodgers1974). Kolosovskiy's TPC model (Reference Kolosovskiy1961: 5), also included a complementary objective to develop the economic equality of nationalities and national republics in addition to industrial specialization, resource-based agglomerations, and interregional supply networks. The regional equality doctrine contributed to the subordination of the economic coordination of TPC systems to the political relations between the center and regional republics (Dellenbrant, Reference Dellenbrant1986). This problem was rarely acknowledged explicitly in Soviet academic debates (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965). A concrete difficulty for Kolosovskiy and the other economic geographers was that the Soviet government could not use the regionalization schemes to legitimately split the existing boundaries between nationality groups in the Soviet Union, even if the logic of economic linkages and agglomeration gains suggested otherwise (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965: 477). This problem also presented a chance for regional representatives to demand direct investment amendments to the official plans on the grounds of regional equality (Lonsdale, Reference Lonsdale1965) or other regional interests (Harris, Reference Harris1999). According to Dellenbrant (Reference Dellenbrant1986: 74–79), the economic regions had only an insignificant impact on regional policies, whereas the relationship between the administrative center and the republics played a more prominent role. This relationship was also a significant driver of central reforms to tackle the inefficiencies of the industrial management system during the late Soviet period (Berliner, Reference Berliner, Bergson and Levine1983; Conyngham, Reference Conyngham1982; Granick, Reference Granick1959; Grossman, Reference Grossman1962; Kibita, Reference Kibita2013).

Transformation and Imprint Dynamics in the Post-Soviet Era

The radical environmental changes caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the related adaptation process (e.g., Dobrev, Reference Dobrev1999; Oertel et al., Reference Oertel, Thommes and Walgenbach2016) exposed the TPC imprint to a variety of transformation dynamics (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015; Zyglidopoulos, Reference Zyglidopoulos1999). Social-normative and regulatory mechanisms of the TPC system decayed or disintegrated during the collapse of the Soviet Union, while cultural-cognitive influence mechanisms remained inert and continued to shape the activities of the collective. In this section, I analyze the role of the Soviet collapse by discussing the dynamics of the TPC imprint as an academic and executive paradigm of the collective and then reviewing the imprinting impact in Russia's regional development.

Imprinting dynamics in the organizational collective

The post-Soviet transition did not result in the organizational dissolution of the analyzed collective, although its hybrid identity was challenged by the introduction of international paradigms and the reshuffling of community members. A large proportion of academic personnel left for business and emigration (Graham & Dezhina, Reference Graham and Dezhina2008; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, McCarthy and Satinsky2018) due to deep budget cuts in universities and research institutes (Suspitsyna, Reference Suspitsyna2005; Yegorov, Reference Yegorov2009). Suspitsyna (Reference Suspitsyna2005) has demonstrated how difficult the introduction and adaptation of Western economic theories into economic faculties in Russian universities in the 1990s was, where the old Soviet paradigms and teaching traditions blended in with the new practices instead of being replaced entirely. For example, at Moscow State University, the Soviet tradition and routines remained persistent due to their central role in the institution's organizational identity (Suspitsyna, Reference Suspitsyna2005: 63–83). Although the post-Soviet transition lifted the restrictions on international collaboration with Western academic and professional communities, the internationalization of Russian scientific communities has been a slow process (Ransel, Reference Ransel2001). For example, the Russian Academy of Sciences retains a major role in Russian academia (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, Graham and Satinsky2014; Mirskaya, Reference Mirskaya1995), and a large proportion of academic publications are still written and cited in Russian, while the overall research production of Russian universities remains modest (Dezhina, Reference Dezhina2011). The recent sanctioning and closure of internationally oriented universities (e.g., Nechepurenko, Reference Nechepurenko2018) exemplifies the enduring suspicions towards external influences that could challenge the existing templates of action.

The post-Soviet hybrid collective in economic geography has also assimilated Soviet methodology into new paradigms (e.g., Krugman, Reference Krugman1991). This transformation has mainly led to a shift in rhetoric practices, leading to the formal demotion of the TPC template as the dominant model for economic organization and the introduction of alternative concepts, such as ‘territorial organization of industrial production’ or ‘territorial industrial system’. During the early 2000s, Michael Porter's (Reference Porter1998) cluster model began to attract attention among the focal collective (Korabeynikov, Ermakova, & Sinyukov, Reference Korabeynikov, Ermakova and Sinjukov2013; Korolev, Reference Korolev2013; Korzh & Lukyanchikova, Reference Korzh and Lukyanchikova2013). This paradigmatic change has been regarded as both incremental and radical divergence from the TPC-based view. While some scholars are ready to exploit the conceptual elasticity of clusters to consider former TPCs as clusters of the past, others disagree and see fundamental differences between the two models and their content (Korabeynikov et al., Reference Korabeynikov, Ermakova and Sinjukov2013: 56; Pilipenko, Reference Pilipenko2005). Conceptual similarities between Porter's cluster theory and the TPCs have initiated a discourse, in which the Soviet paradigm of territorially grouped business environments is regarded as a precursor of a system of innovative clusters (Afonaseva & Romanenko, Reference Afonaseva, O. and Romanenko2017). Particularly in discussions concerning neo-industrialism, the cluster approach is seen as an option for mature TPC industrial districts (Afonaseva & Romanenko, Reference Afonaseva, O. and Romanenko2017; Shevchenko, Razvadovskaya, & Khanina, Reference Shevchenko, Razvadovskaya and Khanina2016). There are also those who believe that the positive agglomeration effects associated with industry clusters should be credited to Soviet economic geographers (e.g., Adamesku, Reference Adamesku2014) or that reintroducing linkages of the TPC model could benefit regional industries (e.g., Rekord, Reference Rekord2012). Overall, an analysis of contemporary academic journals suggests that the imprinting of the TPC model continues to shape collective-level discourses, molding its frames and cultural-cognitive contents into new theories and technological paradigms. Its influence is waning, however, as the Russian economic geography collective is less constrained by the ‘hybridity’ effect, caused by geographical and political isolation, and more oriented towards developing its theoretical work in new directions (e.g., Kolosov et al., Reference Kolosov, Grechko, Mironenko, Samburova, Sluka, Tikunova, Tkachenko, Fedorchenko and Fomichev2016).

Authoritarian regional policy and imprint exaptation

In addition to the changes in the academic content of the TPC model, its role as an executive tool for regional economic policy has undergone a transformation. When the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, its regional economic system broke down, and the existing industrial networks were disconnected from centralized control during privatization (Pilipenko, Reference Pilipenko2005). The Soviet regional system, based on the production cycles of TPCs, declined heavily when the state-governed interconnections and centrally planned linkages between enterprises and production complexes broke down along with the old economic system (Animiza & Denisova, Reference Animiza and Denisova2014; Chasovsky, Reference Chasovsky2015; Khayrullina, Reference Khayrullina2014; Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011). The associated massive waves of migration caused by the collapse of the Soviet economy had major consequences for several TPC production centers (Abazov, Reference Abazov1999; Korobkov & Zaionchkovskaia, Reference Korobkov and Zaionchkovskaia2004), demonstrating that regulatory and social-normative mechanisms (Scott, Reference Scott2013) were essential in the coercive preservation of the socialist TPC structures.

However, the imprinted role of central coordination of economic agglomerations did not disintegrate with the formal TPC model and change from a unitary to a federal system. Instead, some of the social-normative and regulatory elements associated with centralization have become amplified during the Putin era. I perceive these dynamics to be an exaptation strategy, which reflects the cultural-cognitive persistence of centralization in spatial governance. In regional policy, the Russian central government has reacted to modernization pressures by employing two strategies: a) assimilating the legacy as a component of new development or b) through experimental pilot projects (e.g., cluster programs), which nevertheless conform with norms imposed by the existing organizational and institutional environment (Kinossian, Reference Kinossian2017b; Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011).

Since the early 2000s, the central government has made attempts to regain its dominant role in directing economic development (Kinossian & Morgan, Reference Kinossian and Morgan2014). This change in policy was a response to formalize conditions in the market environment and maintain economic and political stability after the devastating years of Yeltsin's regime. In 2008, the Russian Ministry of Economic Development issued a document containing methodological recommendations for launching cluster policies in the Russian Federation (Animiza & Denisova, Reference Animiza and Denisova2014), and the Government has echoed the need for a cluster-oriented economic policy in its long-term economic strategies (Government of the Russian Federation, 2008, 2011). Although this tendency coincided with worldwide interest in the use of the cluster model in policymaking (Swords, Reference Swords2013), and probably also represents an informal strategy to ensure the vested interests of the leading oligarchs (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2006; Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2007), its adoption as a regional development model in Russia can be seen as an exaptation strategy, where the imprinted content of the past is utilized under new conditions. Parallel to the way in which the Soviet planners created and regulated TPCs, the Russian government has tightened its control of regional authorities in order to control the forms of economic development (Kinossian & Morgan, Reference Kinossian and Morgan2014). In 2013, when the Ministry for Regional Development of Russia (Minregion) introduced a working group to collect ‘pilot project’ bids for the creation of urban agglomerations, 15 of 16 initiated programs were coordinated by regional representatives of the government. Later in 2014, the Minregion was disbanded into new ministries, which bear a distinct resemblance to TPC-era ministerial control (Kinossian, Reference Kinossian2017a). Furthermore, the initiatives of the state to invest in state-managed regional growth in the form of techno-parks and an artificial business environment (e.g., Kinossian, 2013) indicate that imprinted cultural-cognitive paradigms in economic management remain attractive for central economic decision-makers since they maintain the power balance between the state and the regions. For example, in the case of the Skolkovo Innovation Center, the Russian government representatives retain executive decision-making power on the boards of key companies and foundations, while investment funds are allocated through the Federal budget (Kinossian & Morgan, Reference Kinossian and Morgan2014).

A potential explanation for the amplification and exaptation of the characteristics associated with the TPC paradigm lies in the fact that the self-reinforcing regional structures offer few plausible alternatives for a quick local renewal (Hassink, Reference Hassink, Boschma and Martin2010; Hassink, Isaksen, & Trippl, Reference Hassink, Isaksen and Trippl2019) of imprinted industrial specialization. By the late 1970s, preplanning designs for each TPC had been drafted up to the year 1990 (Overchuk, Reference Overchuk1982), and large-scale reforms to the existing system were not possible while the post-Soviet Russian economy was experiencing a massive financial crisis (Marangos, Reference Marangos2002). During the 1990s, the sunk costs of investments in industrial geography and the paralysis of the state in initiating genuine economic reform increased the importance of maintaining schemes of production at the regional level. Although TPC structures are currently being replaced with other forms of urban planning in the European part of Russia, there are still 10 functioning TPC structures in the Siberian peripheral regions (Bezrukov, Reference Bezrukov2014). These localities are generally short of alternative market opportunities or regional renewal strategies and thus serve as enduring reminders of the past regional equality policies and Soviet investment miscalculations (Hill & Gaddy, Reference Hill and Gaddy2003).

DISCUSSION

Theoretical Implications

The results of this study provide three theoretical implications for the study of imprinting and regional development. First, the case of TPC imprinting shows that the hybrid character of collectives can play an important role in their development by gatekeeping external influences and self-reinforcing locally legitimate templates of action (Marquis, Reference Marquis2003). This effect facilitates the development of imprinted characteristics into persisting dominant templates since they encounter less isomorphic pressures (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983) or other external influences that could contest their legitimacy within collectives. The case of TPC imprinting demonstrates that such localized effects can persist in organizational collectives through cultural-cognitive contingencies, even if the social-normative and regulatory influence mechanisms decay or disappear as a result of radical environmental transformations (Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009; Scott, Reference Scott2013). These contingencies are linked to imprinted field-level paradigms (Redding & Witt, Reference Redding and Witt2015; Waeger & Weber, Reference Waeger and Weber2019; Zyglidopoulos, Reference Zyglidopoulos1999), which can cause a slower adaptation of organizational collectives to environmental changes compared to individual organizations or firms (Kogut & Zander, Reference Kogut and Zander2000; Kriauciunas & Kale, Reference Kriauciunas and Kale2006). This observation extends the idea that community-based imprinting of organizational collectives can develop via exogenous imprint conditions, such as shared technological conditions (Marquis, Reference Marquis2003), by emphasizing that these conditions can also derive from endogenous cultural-cognitive sources. The results also demonstrate that the persistence of such elements can also produce amplifying mechanisms, such as exaptation, which in turn may reinvoke the social-normative and regulatory contents of imprinting.

Second, the presented case contributes to the understanding of how paradigmatic imprints can influence regional development structures and centralized coordination in socialist and postsocialist countries. In this regard, the study demonstrates that technological paradigms can consequently shape the patterns of development and institutionalization of technological trajectories by acting as environmental imprinters. This result contributes to imprinting theory (e.g., Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015) by showing that imprinting can shape the behavior of entities in ways which, in turn, define how they impose imprints on the organizational structures and configurations of other entities. The case of TPC imprinting demonstrates such an example of reproductive imprinting effects, as the initial imprinting of the TPC model into the Soviet hybrid collective defined the coordination mechanisms by which the collective imposed imprinting policies on regional entities.

Third, the contrast between the technological paradigm of the Soviet economic geographers and the consequent institutionalization processes at the regional level provides a valuable perspective of the study of cross-cultural and indigenous management (Holtbrügge, Reference Holtbrügge2013), particularly the institutionalization processes between the state and within-country regions (Kaasa, Vadi, & Varblane, Reference Kaasa, Vadi and Varblane2014; Minkov & Hofstede, Reference Minkov and Hofstede2014; Paasi, Reference Paasi1986; Peterson & Søndergaard, Reference Peterson and Søndergaard2014) in authoritarian countries. In the present study, the imprinting of the TPC model in the central-level organizational collective resulted from an organizational institutionalization process, based on founder effects and the guiding and goal-setting criteria of the technological paradigm. At the executive level, this process has produced exaptation strategies to accommodate the balance of imprinted characteristics and transformed organizational goals (e.g., Selznick, Reference Selznick1949, Reference Selznick1957). Instead, the institutionalization process of the centrally imposed TPC policies at the regional level relied on coercive and regulative mechanisms (Scott, Reference Scott2013) that could not entirely replace the pre-existing cultural-cognitive and social-normative institutions (i.e., ethnic boundaries) at the local level. Currently, this has contributed to the tense situation between centralized development strategies and the within-country regions, which may not share the same goals but remain economically tied to the center due to imprints and path dependencies deriving from the coercive socialist economic system. These different institutionalization processes and the ability of some regions to locally resist or influence centrally imposed strategies during the Soviet era may help to explain why some of the former TPC regions have been able to replace imprinted characteristics with local cultural endowments. These results imply that the cultural variation in regions in authoritarian nations may potentially consist of much more complex institutional relationships and bargaining processes compared to countries that tolerate more social-normative and cultural heterogeneity or allow higher degrees of local discretion in economic decision-making (Qian & Xu, Reference Qian and Xu1993).

Managerial Implications

The results of this study also have several contextual implications for Russia's management environment. Below, I discuss these implications for the national level and the regional level, as well as for potential foreign investors.

National level

A complete discarding of technological paradigms is costly because the problem-solving process has to start (almost) from the beginning (Dosi, Reference Dosi1982: 154). Thus, the national level introduction of industrial cluster policy by intermixing the conceptual contents of TPCs and clusters (Korabeynikov, Ermakova, & Sinyukov, Reference Korabeynikov, Ermakova and Sinjukov2013: 56; Pilipenko, Reference Pilipenko2005) may provide short-term solutions for addressing the economic situation in former TPC regions. However, this exaptation strategy will likely sustain some of the imprinted institutional characteristics, particularly at the cultural-cognitive level (Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2007), which makes it unlikely to prove successful over long-term development. This is because these imprinted characteristics originally developed as a response to the founding environmental conditions and hence do not fully address the issues of contemporary or future business environments. Since a substantial reversal towards a unitary economic system based on functional and specialization principles is hardly an option for the Russian economy, exaptation strategies are not economically sustainable, especially if they continue to constrain local initiatives and thus hinder the development of regional resilience (Hassink, Reference Hassink2011).

Overall, the Soviet legacy consists of multiple imprints in the institutional, socioeconomic, and political environment. Recent studies of imprint coexistence suggest that a potential avenue for policymakers would be to attempt conscious strategic management of the existing imprints by actively rearranging imprint mechanisms through prioritizing and suspending their content (e.g., Sinha, Jaskiewicz, Gibb, & Combs, Reference Sinha, Jaskiewicz, Gibb and Combs2020). This management process usually involves strategic agency and organizational learning (Ferriani, Garnsey, & Lorenzoni, Reference Ferriani, Garnsey and Lorenzoni2012; Kriauciunas & Kale, Reference Kriauciunas and Kale2006; Marquis & Huang, Reference Marquis and Huang2010), which in the case of the TPC imprint would include an explicit identification and review of the positive and negative aspects of the imprinted governance model and consequent strategic actions to mitigate the effects of adverse imprint dynamics. However, besides the effects of socialist imprinting, the 1991 transition presents another monumental source of imprinting for Russian government officials, even if it is still too early to fully evaluate the nuances and duration of its impact. Imprinted traumatic experiences caused by this radical institutional change are likely prioritized in the mindsets of the current leadership and thus may contribute to their willingness to avoid risks related to upgrading or suspending the TPC-imprinted spatial governance system. The ‘shock-imprinting’ effects (e.g., Dieleman, Reference Dieleman2011) associated with this period may currently be intensified by cohort effects (Joshi, Dencker, Franz, & Martozzio, Reference Joshi, Dencker, Franz and Martocchio2010) since the generation that now occupies most of the senior management positions experienced the turbulent years of the 1990s during their early adulthood. In this regard, it may take yet another generation for a more complete decay of socialist imprints to take place.

Regional level

Regional level actors consist of local regional authorities and localized entrepreneurs belonging to geographically embedded communities in different regional entities (Marquis et al., Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011). This category varies significantly depending on the degree to which the regionalized structures of Soviet industries still impose path-dependent effects (Schreyögg & Sydow, Reference Schreyögg and Sydow2011) on local development. This problem is particularly topical in monoindustrial urban settlements (Crowley, Reference Crowley2016), which were highly dependent on Soviet industrial plans and TPCs and have scarce local endowments for industrial diversification. Based on insights from path dependence literature (Blažek, Květoň, Baumgartner-Seiringer, & Trippl, Reference Blažek, Květoň, Baumgartinger-Seiringer and Trippl2019; Koch, Reference Koch2011; Sydow et al., Reference Sydow, Schreyögg and Koch2009; Schreyögg & Sydow, Reference Schreyögg and Sydow2011) and building on the notion that the length of exposure to the imprint template prolongs the decay of imprinted characteristics (Alesina & Fuchs-Schundeln, Reference Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln2007; Banalieva et al., Reference Banalieva, Karam, Ralston, Elenkov, Naoumova, Dabic, Potocan, Starkus, Danis and Wallace2017), I predict that a complete detachment from structural elements of the TPC-based regional imprinting will take time. This is because long-term imprints direct sunk costs and self-reinforcing mechanisms in local learning, industry specialization, and the coordination of production (Sydow et al., Reference Sydow, Schreyögg and Koch2009), but also due to the role of TPC imprinting in shaping cultural-cognitive identities of regional communities. Imprinted conceptions of centralization and hierarchical spatial governance may even extend to modernization processes at the intraregional level. In such cases, geographical distance from the administrative centers may facilitate the ability of smaller urban communities to mitigate the effects of centralized coordination and develop the local institutional environment (Zamyatina & Pelyasov, Reference Zamyatina, Pelyasov and Orttung2016).

On the other hand, there are multiple examples of urban regional centers in Russia that have successfully diversified their industrial structure to new sectors (Ivanov, Reference Ivanov2016; Lin & Ivanov, Reference Lin and Ivanov2017; Savelyev, Reference Savelyev2013; World Bank, 2012) and developed their local business environments. The ability to escape the negative outcomes of regional imprinting seems to correlate positively with efficient local educational institutions (Agasisti, Egorov, Zichenko, & Leshukov, Reference Agasisti, Egorov, Zinchenko and Leshukov2020) and knowledge endowments (Crescenzi & Jaax, Reference Crescenzi and Jaax2017; Ivanov, Reference Ivanov2016). The level of regional autonomy in sustaining these agglomerations is likely to determine their success since subordination to authoritarian control will primarily maintain only those business models which do not fundamentally challenge imprinted cultural-cognitive institutions (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Puffer, Graham and Satinsky2014).

Foreign investors