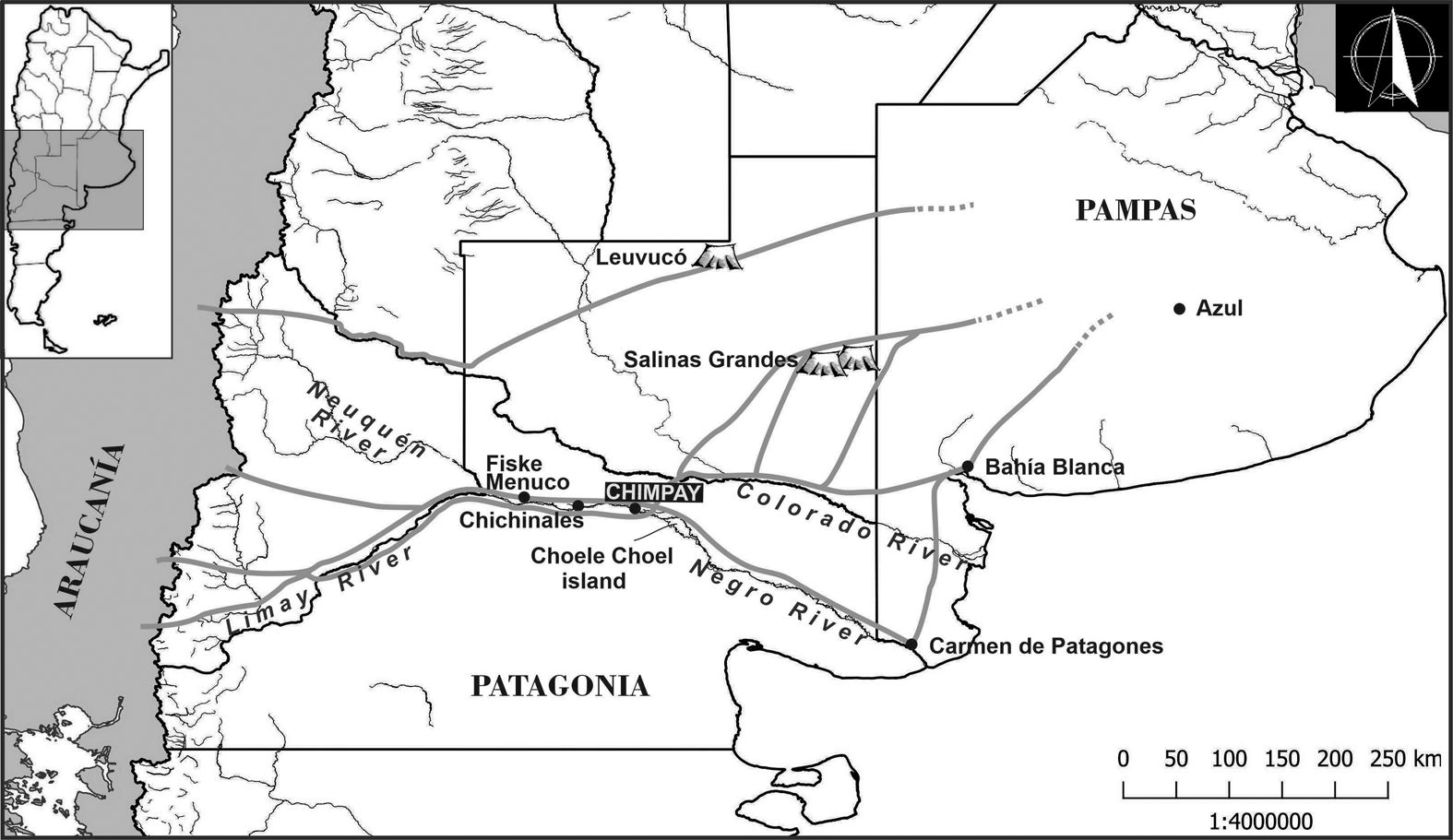

From the middle of the sixteenth century onward, the Spanish presence north of the Biobío River and around the La Plata Basin (the current territories of Chile and Argentina/Uruguay, respectively) fueled significant changes in the lives of Indigenous people, who developed commercial and social ties with Hispano-Creoles but strongly reacted to the domination and occupation of their territories (Bechis Reference Bechis and Bechis2008a; Mandrini and Ortelli Reference Mandrini, Ortelli and Boccara2002; Palermo Reference Palermo1999; Pinto Rodríguez Reference Pinto Rodríguez and Rodríguez1996). Around the eighteenth century, trade networks and mobility deepened the precolonial connections between Indigenous people of both sides of the Andes, from the Araucanía to Buenos Aires (see Figure 1). This complex and dynamic commercial system, based mainly on the traffic of cattle, salt, and Indigenous textiles, continued into the nineteenth century and gave rise to an important Arauco-Pampean-Patagonian sociocultural unit. In Pampa-Patagonia, large cacicazgos (chiefdoms) or confederations consolidated and had a strong relationship with the Argentine state (Bechis Reference Bechis and Bechis2008a; Mandrini and Ortelli Reference Mandrini, Ortelli and Boccara2002). Secured by kinship reciprocity, these chiefdoms’ commercial and political ties connected distant people and places, from the Araucanía to the Pampas. In this scenario, the Indigenous leaders negotiated with the Argentine state on the frontier segments closest to their territory in an effort to ensure the peaceful conditions necessary for commercial exchanges (Davies Lenoble Reference Davies Lenoble2017; de Jong Reference de Jong and Quijada2011; Vezub Reference Vezub2009). Whether these border relationships were characterized by diplomacy or war depended on the political role played by the leading chiefs. On their shoulders rested the management of consensus from their followers, the political dialogue with state officials, and the staging of malones (raids against the Creoles) when diplomatic efforts failed (de Jong Reference de Jong2016).

Figure 1. Main portion of the Arauco-Pampean area with locations mentioned in the text.

As relationships deepened between Indigenous people and Creoles, changing political conditions provided new opportunities for Indigenous leadership, like the institution of “friendly chiefs,” who settled with their tribes on the Buenos Aires border. They were important mediators with Indigenous populations in the hinterland and provided military support to the state on the borders. Their degree of autonomy in the context of the fluctuating balance of forces between the state and independent Indigenous society quickly narrowed from 1870 onward. When the state began to wage military campaigns of occupation in the territories of Pampa and Patagonia, known as the Conquista del Desierto, the militarization of the “friendly Indians” intensified, extending to those “inland Indians” who were taken prisoners and quickly became part of the army or of the National Guard's civil corps. The Indigenous military hierarchies, however, tended to be reproduced inside of the state-organized military bodies, which meant that in this new context the figure of the chief remained significant (de Jong Reference de Jong2014; Literas and Barbuto Reference Literas and Barbuto2018).

There were several leadership ranks within Mapuche society: the main chief (cacique principal), secondary chiefs (caciques secundarios), capitanejos, and mocetones. These leadership positions were obtained by belonging to prestigious parental lineages or performing well in war and in diplomacy on the borders or both. The sociopolitical organization patterns of Indigenous politics, which were tied to authority deriving from prestige rather than power—understood as coercive capability—limited the leaders’ possibility of accumulating wealth (Bechis Reference Bechis and Bechis2008a). However, throughout the nineteenth century, historical documents reflected these leaders having a growing control of different political functions. They became very influential players in the political arena, with the ability to convene great political reunions or parliaments for the discussion of peace treaties, instigate and plan military actions, and dispense justice among the members of their chiefdoms (Jiménez and Alioto Reference Jiménez and Alioto2011).

The centrality of Mapuche leadership permeated the economic, social, and religious spheres. In fact, it often extended to the mortuary ceremonies of the leaders themselves. Descriptions of the burial rituals of some Mapuche chiefs abound in the ethnohistorical record; the rituals’ characteristics depend on the hierarchical place that the deceased occupied. In these ceremonies, the body of the deceased was buried along with his most valuable objects, food, belongings, and sacrificed animals; some sources even refer to the sacrificing of women. Although the sacrifice of women does not seem to be systemic, numerous hints to wives’ place in the wake of their husband's passing raise questions about the dissemination and historical depth of this practice, which González (Reference González1979) referred to as the suttee in the Arauco-Pampean-Patagonian space.Footnote 1 Although there is abundant literature on Mapuche mortuary rites (see Dillehay Reference Dillehay1985, Reference Dillehay2011), the suttee does not seem to have been a widely practiced burial custom in the Araucanía.

From the pioneering paper by González (Reference González1979), some scholars considered the suttee, along with other social and ceremonial/ritual events, as evidence of the transformation of Pampean Indian bands into chiefdoms at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries (Mandrini Reference Mandrini1994, Reference Mandrini2000; Mandrini and Ortelli Reference Mandrini, Ortelli and Boccara2002). Others suggested that sociopolitical complexity among Mapuches remained tied to tribal structures and that the suttee would not necessarily be interpreted as a diacritical of greater social complexity (Bechis Reference Bechis and Bechis2008a). This discussion waned, and perhaps because no new archaeological or ethnohistorical records of the suttee were reported, this issue was forgotten during the last two decades. In this article, we bring the suttee back to the agenda by evaluating a mortuary archaeological context from northern Patagonia.

In the Chimpay archaeological site, a man wearing a military uniform and a woman were buried together along with varied funerary goods. Archaeological analysis suggests that this was a late nineteenth-century Mapuche burial, that the man was probably a chief or a capitanejo, and that the woman appeared to have a prestigious social position (Prates et al. Reference Prates, Serna, Mange and de Jong2016; Serna et al. Reference Serna, Prates and Luna2015). In this article, we aim, first, to validate these preliminary results through the analysis of ethnohistorical information; second, to evaluate the possible motivations for the inhumation of these two individuals in the same burial site, taking into account the suttee hypothesis; and third, to discuss the main implications of our interpretation in terms of Mapuche mortuary practices in Pampas and Patagonia. We do not aim to discuss the suttee as an expression of political centralization because this would require a deeper exploration of the meanings of the Mapuche culture and the contexts in which this burial occurred.

Archaeological and Historical Settings

The Chimpay Archaeological Site

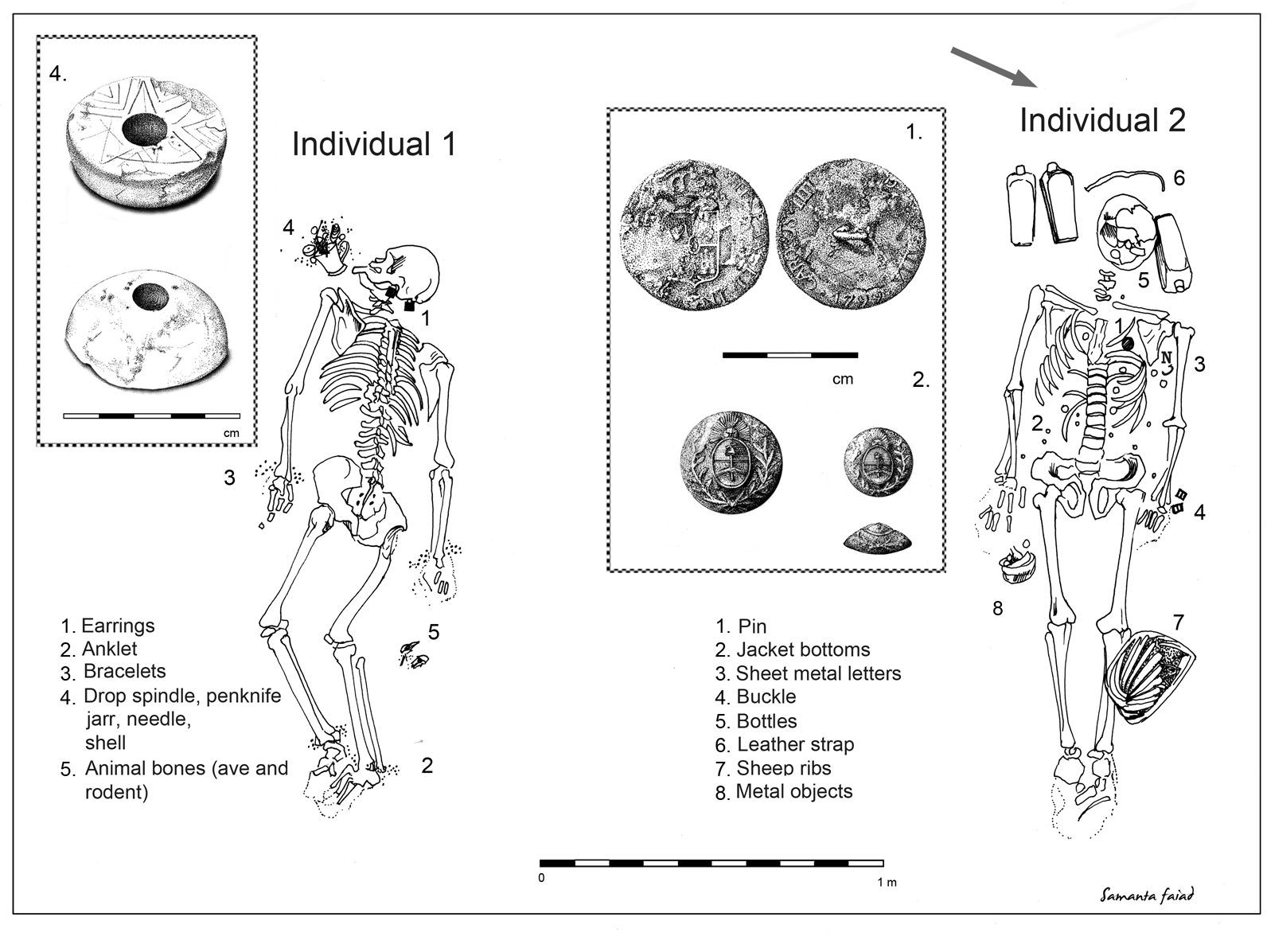

Chimpay is a mortuary site located in the middle valley of the Negro River, in which a double human burial of a man and a woman arranged parallel to one another was found (Prates et al. Reference Prates, Serna, Mange and de Jong2016; see Figure 2). Dental morphological traits and characteristics of the funerary deposit suggest a likely Amerindian filiation for both individuals (Serna et al. Reference Serna, Prates and Luna2015). The man (25–35 years old) is buried on his back, stretched out straight (Serna et al. Reference Serna, Prates and Luna2015), wearing a jacket or a military dolman with buttons that were manufactured by the Argentine army after 1852 and at least until 1881 (Leoni Reference Leoni2009). He is wearing a military hat and a baldric made for a firearm or a sword; funerary goods—three glass bottles, a small metal saucepan, two spoons, undetermined metal fragments, a brooch made of a silver coin from the eighteenth century, and a rack of lamb—are placed alongside him.

Figure 2. Schematic drawing of the double human burial at the site Chimpay (modified from Prates et al. Reference Prates, Serna, Mange and de Jong2016:Figure 2).

The woman (40–49 years old) is buried on her belly, laid out straight with the legs semi-flexed, and with a diverse funerary accompaniment (Serna et al. Reference Serna, Prates and Luna2015). She is wearing a headdress with copper appliqués, trapezoid-shaped copper earrings with an arched filament, bracelets, and anklets. Other goods—including an earthenware jar, sewing supplies (thimbles and a needle), a stone drop spindle, more than 7,000 glass beads, textile fragments, and a pocketknife—are placed alongside her (Prates et al. Reference Prates, Serna, Mange and de Jong2016).

The Negro River Valley during the Nineteenth Century

Chimpay is located close to Choele Choel, an island of the Negro River. This island was a nodal point of the Indigenous routes that connected the Araucanía with the Pampas, which had heavy traffic in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The riverbanks of the Negro River were a part of the roads that led to Buenos Aires and to three military forts: Azul, Bahía Blanca, and Carmen de Patagones (the southernmost stable fortification in Patagonia). The nampülkafe (travelers and merchants) of different regions of the Araucanía—the Huilliches that controlled the Limay and Negro Rivers and the Tehuelches, Pehuenches, Salineros, and Ranqueles—traveled in and occupied this region in different periods. The Choele Choel island provided a spot with exceptional pastureland and water, needed for the rest and recuperation of the horses and cattle being transported (Bello Reference Bello2011). The Argentine state tried on multiple occasions to occupy the island, sending naval expeditions to the Negro River. However, the first attempts of occupation by Juan Manuel de Rosas, between 1833 and 1834, and later in 1868, were fleeting and aroused strong political opposition from the Indigenous people. Eventually, Choele Choel became the meeting place for the army columns that integrated the so-called Conquista del Desierto that in May 1879 carried out the first stage of the conquest by occupying the territories of Salineros and Ranqueles.

In Choele Choel the construction of the Avellaneda Village began in 1879 (Raone Reference Raone1969). Among the subdued groups that began to form military posts along the Negro River—General Roca (Fiske Menuco), Chichinales, and Carmen de Patagones—was settled the tribe of Chief Manuel Namuncurá, son of Calfucurá, which toward the end of 1878 was kicked out of its land in Salinas Grandes and chased by the Argentine army into Chilean territory. After the tribe's arrival in March 1884 in Ñorquín, its chiefs and capitanejos formed the two companies of the Indigenous Squad of Namuncurá, which submitted to state military service between 1885 and 1887.Footnote 2 Namuncurá received the permission of Patagonia's governor Lorenzo Wintter to settle with his people on Chimpay lands in 1884; his son Ceferino would be born there in 1886 (Clifton Goldney Reference Clifton Goldney1964). However, at that time many other Indigenous groups militarized by the state were provisionally located in Choele Choel and its surroundings (Raone Reference Raone1969).

Ethnohistorical Data on Burial Ceremonies among Mapuche Chiefdoms of the Nineteenth Century

Funerary Accompaniments and Sacrifices in the Araucanía

In the early nineteenth century, Indigenous concepts of death and funerary practices in northern Patagonia were similar on both sides of the Andes. This was the result of ties between the populations all around the Arauco-Pampean area that led to cultural homogenization (Mandrini and Ortelli Reference Mandrini, Ortelli and Boccara2002). Death was understood as a trip to Allhue Mapu, a mythical land located to the west across the ocean, to which the dead had to be accompanied by their most precious objects, the ones they used the most during their lifetimes. Nineteenth-century sources indicate that mortuary rituals were linked to the deceased's hierarchic rank and involved the activation of political and parental ties and the spending of resources at different scales. Therefore, the chief's mortuary ceremonies generally differed from those of a cona, or common man—in ways beyond wealth—and probably from the ceremonies of most women.

Mapuche tombs in the Araucanía appear in several forms, from burial urns and canoes to burial mounds (cuel); the mounds are associated with important chiefs, shamans, and wealthy men (Dillehay Reference Dillehay1990, Reference Dillehay2011). According to those ethnohistorical documents that refer to chiefs’ death ceremonies, he was buried both with his most valued objects—silver tools: headstalls, stirrups, and spurs; weapons; and his favorite horse, sacrificed on his grave—and with goods he would need for his journey to the afterlife, including food and drink. These testimonies describe the funeral rites taking days or even weeks of preparation and the summoning of distant relatives to participate. The procession followed ritual greetings between men, and women participated as lloronas (mourners); the men and women walked alongside the body, as it was transported to an open space, or pampa. In that space was conducted a multiday funeral ceremony. During several days of dancing and drinking, the trilla was conducted, in which men on horses rode laps around the corpse and competed in horse races toward the east of the grave. In addition, the most politically important men conducted sheep sacrifices, dripping the blood of the animal's heart in honor of the deceased. A wooden sculpture in human shape with the deceased's attributes accompanied the canoe with his body (Coña Reference Coña1973 [1930]; Gay Reference Gay and Córdova1998 [1837]).

Testimonies on burials of women and men of lower status also describe the accompaniment of the deceased's goods into the grave—in the case of women, their knitting and cooking tools, and a horse was sacrificed if the deceased owned horses when alive (Rehuel Smith Reference Rehuel Smith1914 [1855]). As the Chilean state gained increasing control of the Araucanía between the decades of 1860 and 1880, the resulting Indigenous population's impoverishment fostered the commercialization of their silver ornaments and led to an increase in grave robbing. As a result, fewer silver pieces were included among the grave goods (Flores Chávez Reference Flores Chávez2013).

There are only indirect references to the sacrifice of women as part of funerary rites in the Araucanía. The traveler Edmund Rehuel Smith (Reference Rehuel Smith1914 [1855]:88) wrote that he had heard that “when a distinguished chief dies, one of his women is killed, and she is buried alongside him.” At the end of the nineteenth century, Rodolfo Lenz (Reference Lenz1895–1897) registered a folktale, “The Dead Man's Bride,” in which a woman had such a great longing for her dead husband that the burial canoe was reopened so she could be buried alive alongside him. Although the Mapuche chief Pascual Coña (Reference Coña1973 [1930]) did not allude to the sacrifice of women in his description of traditional Mapuche burial customs, he did mention it in another part of his memoir. He referred to the fact that the big chiefs like Colipí, Marileu, Manguiñ, Ingal, and Neculpan Zúñiga, who each had 20 or more wives, had resorted to this custom. Just before dying, these chiefs said, “I want to take one of my wives with me, the prettiest one; when I'm buried send her to me and throw her to the grave alongside me” (Coña Reference Coña1973 [1930]:190).Footnote 3

Another practice that may have been linked to the death ceremonies of the chiefs was the kalkutun. It was an interpretive system of reality by which the Mapuches explained illness and death as a result of a conscious aggression by the kalku, or witch, who transgressed the bonds of reciprocity and solidarity on which society was based (García Insausti Reference García Insausti2019). The witch was identified and punished as a way to restore the lost balance. The accusation of witchcraft, made by the victim before dying or by the machi (shaman), could fall on a relative, close or distant, or even on the machi who was not able to heal the sick person. According to this recent interpretation, the kalkutun should not be seen as a sacrificial feature in the face of death but as a way to interpret misfortune, compensate for damage, and carry out social prophylaxis (García Insausti Reference García Insausti2019). In 1837, the naturalist Claudio Gay, who traveled through the Araucanía, pointed out that “there is no death of a chief without burning some witches, and sometimes they can burn up to six of them” (Reference Gay and Córdova1998 [1837]:22). The kalkutun was a widespread institution for which there are many testimonies, showing that it was not exclusively related to the funerals of important chiefs (García Insausti Reference García Insausti2019).

Burial Ceremonies and Funerary Accompaniments in the Pampas

Although Mapuche burials in the Pampas were less diverse than in the Araucanía—for example, they did not include burial mounds or burial in canoes—the Mapuches’ ritual practices around death and burial in both areas were similar. Santiago Avendaño, a former captive who lived alongside Ranquel groups between 1842 and 1849, describes the practices regarding death in a part of his memoirs. It deals with the case of a Picunche relative who fell ill and later passed away while visiting the Ranquel toldos (Mapuche settlements) under the leadership of Caniú, who was holding Avendaño captive, in the year 1846; he writes, “He died before noon. He was immediately dressed up in his best clothes, until the corpse got cold. Once it was cold, they carried him on a horse, ahead of the people, to be buried. When they were about to lower him into the grave, they stopped to do an autopsy” (Avendaño Reference Avendaño2000:63).

An autopsy, which consisted of opening the body from the stomach to the left hipbone, following the line of the ribs, shows up in two other burials described by Avendaño in his memoirs. It seems to have been a common practice done to examine the gallbladder and survey its thickness and color:

After a careful exam, everything was put back into the body and, once they had closed it up, it was placed in the grave. . . . Right away they placed a water-filled jar, some cooked meat and all the rest of the luggage alongside him. . . . Each of his relatives and friends, particularly his son, the first of them all, cut down a lock of their hair and tied it with a string, separating each piece. They put it in his left hand, for eternal memory . . .

They made a roof out of strong sticks separating them by about forty centimeters from each other. Then on top of it they placed a piece of horse hide covered with a layer of straw. Lastly, they threw dirt on him. . . . Once the dirt was placed on top of the ceiling, stepped on and secured, they lit a big fire at the head of the grave, which as usual was looking to where the sun hides. . . . For the funeral to be complete, they strangled the horse the deceased held valued the most and after killing him they laid him down as if he was resting [Avendaño Reference Avendaño2000:63–64].

Avendaño was also an eyewitness to the 1847 burial of Manuel Güichal, son of the Ranquel chief Pichuin, which was conducted similarly:

The corpse of Manuel Güichal was dressed in his clothes and mourned at night by all his friends. For this funeral they took the body to a beach that served as a backyard. They laid him, as they do all dead, with the head toward the West; they lit up four big fires, one to the right of the head, one to the left, and two at the feet of the deceased [Avendaño Reference Avendaño2000:71].

In another description of the burial of Pichiquintuí, an Indian woman who died after falling ill, Avendaño refers to a lining or coffin made of hide in which the deceased was wrapped to be transported by horse to the place of burial. While wrapped in this leather lining, the corpse was placed in the pit along with all her attire, as well as objects that she used or that belonged to her in life. The goods, in this case, included “bags with balls of string; a sharpening stone . . . a big knife, a number of blankets, etc.” (Avendaño Reference Avendaño2000:134). The corpse was dressed in formal attire, wearing her beads, and her face was painted red with black tears. Avendaño again mentions the positioning of the corpse with the head toward the west:

It is to be known that the buried are placed in such a way that the head looks toward where the sun goes down. . . . The animals that they bury to put to the deceased's service look toward the West, as evidence of grief, because they say that the Alhuémapú is in that direction and, believing that, they also believe that they're showing them their way to said place by burying them that way [Avendaño Reference Avendaño2000:136].

Guinnard (Reference Guinnard2004 [1863]), who was a captive of the “Poyuches”—probably the Huilliches from the eastern Andes who wandered along the Negro River—also refers to the leather wrapping as a customary way of preparing the corpse:

If they die on the way they are buried quickly and with no ceremony. Those who die inside their tent, with their family, are, on the contrary, buried with a great deal of pomp. They place the corpse, dressed up with his most beautiful ornaments, on the hide of a horse: they put his weapons and most precious objects, such as spurs, silver stirrups, etc., on both his sides, after which they tie up the hide strongly so that the deceased is well wrapped in it, and mount him on his favorite horse [Guinnard Reference Guinnard2004 [1863]:53].

The same elements are reiterated in the testimony of Lorenzo Deus, another former prisoner in 1872, who adds that a big bonfire was lit up over the grave “so that the dead had a way to light up the way on his journey to the other world” (Reference Deus1985:85).

In 1871, the death and funeral of the chief Ignacio Coliqueo (born in Boroa, Chile) and a friendly Indian on the west border of Buenos Aires from 1860 on were indirectly recorded in some military reports and were preserved in the memory of his descendants. Meinrado Hux recorded an account of Coliqueo's burial that mentions he was buried wearing his dress army uniform. In contrast with the burials of the majority of people, who were buried in hides, a wooden box was used for the chief (Hux Reference Hux2009:256), and he was accompanied by his belongings, clothes, and weapons. The deceased and his horses were buried with heads toward the west.

Similar descriptions can be found in military accounts of soldiers who had contact with Indigenous society in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Federico Barbará (Reference Barbará2000 [1879]), who was in the Argentine army, describes the mortuary practices in Salinas Grandes between the decades of 1860 and 1870, referring to the provisions of corn, chicha, and water that accompanied the dead, as well as the sacrificing of the horse most valued by the deceased, a custom that—possibly because of a shortness of horses—was slowly declining in use in the later years of the frontier period.

Estanislao Zeballos (Reference Zeballos2004 [1879]:238–239), Argentine intellectual, traveler, and politician, mentions the Indigenous practice of burying the dead on the sides of dunes or high areas, where the corpses can be seen lying next to each other with the head toward the west, with the only exterior reference being the whitened bones of the sacrificed horses. He also describes the graves as huacas inside the sand, lined with hard wood. He alludes to the hide casket that wraps around the corpses and to the silver elements—spurs and horse ornaments—that characterize these burials, as well as to the frequent inclusion of the dogs that followed their owners in life.

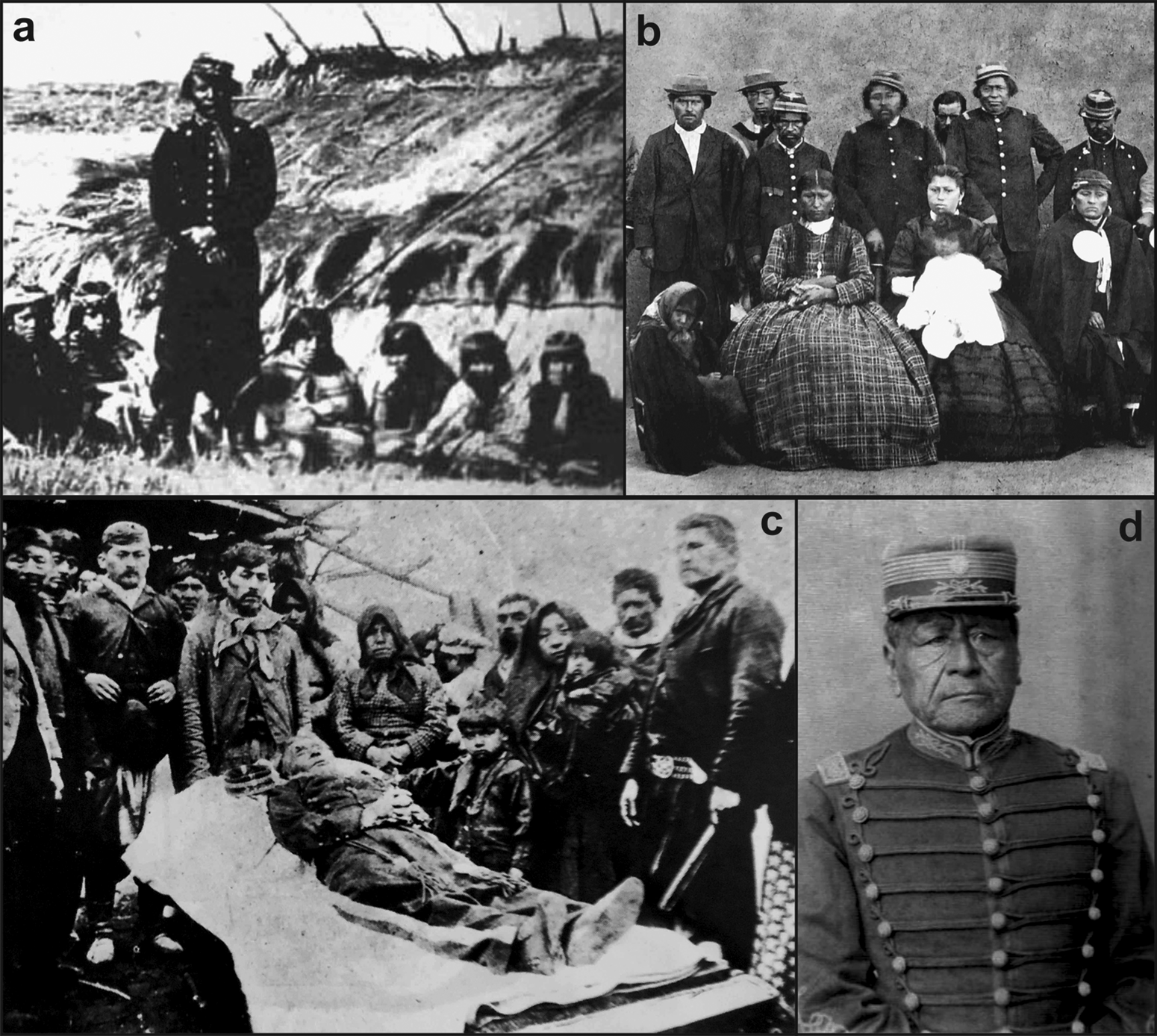

References to the use of military uniforms as the main chiefs’ mortuary clothing are common as well. In the eighteenth century, wearing these uniforms was a sign of prestige and military prowess and success: they could only be obtained by taking them from their original Christian wearer (Alioto and Jiménez Reference Alioto and Jiménez2018). By the middle of the nineteenth century, the chiefs gained access to military clothing when the state bestowed military titles on them in the context of the peace treaties (de Jong Reference de Jong and Quijada2011). These uniforms’ possession marked the position of its wearer as being on the political cusp of the chiefdoms, as illustrated by the numerous photographs from the late nineteenth century; for example, Ignacio, Justo, and Simón Coliqueo (Figure 3b) and Cipriano Catriel, Pedro Melinao, and Manuel Namuncurá (Figure 3d). The photo of Chief Pichihuinca's burial (Figure 3c) shows him wearing a military uniform, as does the testimony collected by Estanislao Zeballos about Calfucurá's grave. The Salinero chief wore a general's uniform, according to Lieutenant Nicolás Levalle, who discovered his burial place in 1878:

The grave was eighty centimeters wide by three meters deep. . . . On the first layer of dirt were the dry bones of a horse. It was the deceased's battle partner, who had been buried with his owner in the same grave. To the right, and close to the bones of the hand, there were two broken swords. On the horse's skull shone the silver headstalls. . . . Among the swords there was a gold ragona . . . . The deceased wore a general's uniform, from the look of the loops in the blouse. . . . The pants had a luxurious golden band. . . . A pair of sea lion hide boots . . . complemented the shroud. At the feet there was another pair of boots, identical to the one worn by the deceased; and there were also around twenty bottles of anisette, caña, gin, aguardiente, pulcú or apple liquor, cognac and water forming a semi-circle. Horse, weapons and drink: everything necessary for the journey to the afterlife [Zeballos Reference Zeballos2004 [1879]:286].

Figure 3. Indigenous leaders wearing military uniforms at the end of the nineteenth century: (a) Cacique Millamain (from 1882); (b) Cacique Ignacio Coliqueo and family (from 1865); (c) funeral of Cacique Pichihuinca (from 1900); (d) Cacique Manuel Namuncurá, who lived in Chimpay between 1884 and 1892 (from 1899).

With the decrease in Indigenous autonomy toward the end of the nineteenth century, a greater number of Indigenous men gained access to military uniforms. However, their use remained a symbol of a high position in the political hierarchy that had been enjoyed by those who were the main leaders during the period of frontier relationships. As shown by the photos of Manuel Namuncurá from the decades of 1890 and 1900, these uniforms were worn when the chiefs engaged in negotiations with state officials for land.

Sacrificing of Women in Funerary Ceremonies

There are fewer ethnohistorical records of women being sacrificed in Indigenous burials in the Pampas and northern Patagonia during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Nevertheless, several documents provide similar clues to those of the Araucanía.

In 1844, Avendaño may have witnessed the burial ceremonies for the Ranquel chief Painé (1780–1844) on Leuvucó (Hux Reference Hux2004). As usual, the chief's corpse was laid out “as it was the custom,” “wearing all his clothes in his resting place,” and the usual funeral was carried out. In this case, the burial was also accompanied by two other practices: the killing of witches considered responsible for the death of the chief and the death of one or more of his wives.

Regarding the second of these practices, from Avendaño's account it can be inferred that the custom was for the first and main woman to accompany her husband to Allhue Mapu. This principle was followed in the case of Painé's death: Calvaiñ, son of Painé, said to the condemned woman, “It is necessary for it to be this way, not because you are a witch. If you were, you wouldn't accompany my father into the pit. You know well that his first woman has to go with him.” The young woman complained, arguing that she was not the first woman and that instead Calvaiñ's own mother had that role. He replied that his mother would be exempted from such a fate, because she was already too old and was no longer residing with her husband (Avendaño Reference Avendaño2004:98–99).

Painé's body was laid into the pit, “wearing his best, his silver spurs next to him, his saddle well wrapped and linked to it his silver stirrups, his llochocón [set of silver veneer], etc.” (Avendaño Reference Avendaño2004:99). The wife was killed with a blow to her head and placed on the pit to the left of her husband. After closing the grave with big sticks and placing hay and dirt on top, the men killed five of the deceased's horses and killed several sheep. Chief Painé's funeral also was the occasion for what seems to have been an exceptional witch slaughtering: 31 according to Avendaño's account and 71 according to other documentation.Footnote 4

As we have seen, the kalkutun integrated the entirety of the Mapuche population's symbolic representations. According to Mapuche understanding in the nineteenth century, death was never attributed to natural causes; instead the harm was caused by someone, frequently a woman, who was accused of being a witch and who was killed to compensate for the damage that she had wreaked. We suggest that the scale of the slaughter of witches that occurred at the funeral of the cacique Painé was linked to the exacerbation of interpersonal conflicts generated by the abrupt economic and demographic changes suffered by the Ranqueles in those years (García Insausti Reference García Insausti2019).Footnote 5

Our examination of the ethnohistorical documents allows us to distinguish the suttee from the kalkutun. This distinction was initially made by González (Reference González1979), who interpreted Avendaño's source as identifying the practice of sacrificing an important man's favorite woman, which he claimed was a case of suttee—making it an index of the political complexity acquired by the Pampa chiefdoms in the first half of the nineteenth century. In contrast to the killing of witches, he claims that suttee would have been fairly localized, with a possible precedent in ancient Araucanía, but was reestablished in the context of the concentration of power and wealth in shaping what he termed the “equestrian chiefdoms” of the Pampas.

Mandrini returned to the issue of the suttee in the Pampas as discussed by González (Reference González1979), interpreting this institution to be among the indicators of a process of social differentiation and power concentration that took place between the second half of the eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth century as part of the consolidation of these chiefdom societies (Mandrini Reference Mandrini1994:273). According to this author, the earliest indicators of the suttee can be found in the accounts of the Jesuits Cardiel and Quiroga of a grave found in southern Patagonia in 1745: it contained a man and two women wearing clothes and ornaments with material characteristics that would link them to the southern Tehuelche people (Mandrini Reference Mandrini2000; see also Lozano Reference Lozano1836 [1745]).Footnote 6

Mandrini also found evidence for the custom of burying the deceased chief's favorite wife alongside him among the Indigenous people to the south of Buenos Aires (the Tehuelches, who were closely related to the Mapuches) in the descriptions written by William Yates (Reference Yates1941 [1820–1821]) and Pedro Andrés García (Reference García and de Angelis1972 [1836]). In both cases, the woman was a part of the group of goods that would accompany the dead man in his journey to the other world:

Chief Pichiloncoy's oldest woman had to be buried alive with her husband, because it's custom that the chiefs who die take a woman, all their goods, property, weapons, jewellery, etc.; the reason is because they believe that the man that stops existing in this world will keep on living in another, imaginary one, and so that he will not be alone, they give him the woman and all his other goods, so that they can emigrate to another country where they will exist for a second time. . . . The china, wife of Pichiloncoy, had already prepared herself to make this journey with her husband, and packed everything for the departure [García Reference García and de Angelis1972 [1836]:147].

Thus, the presence of the suttee in the Pampas and northern Patagonia is tied to a few but clearly described sources. Over the past 20 years, as mentioned there was no substantial progress in the analysis of this practice, considered by González (Reference González1979) and Mandrini (Reference Mandrini2000) to be an attribute of consolidated hierarchical chiefdoms. Bechis was the only one to write about this practice in the first decade of the twenty-first century; referring to the burial of Chief Painé, she interpreted the suttee and the witch hunt as ways for men to demonstrate power over women; in that way, their burials could be seen as practices to strengthen their leadership (Reference Bechis and Bechis2008a, Reference Bechis and Bechis2008b). Most recently, García Insausti (Reference García Insausti2019) modified this hypothesis specifically in relation to the kalkutun, arguing for the difficulty for the leaders of manipulating accusations of witchcraft but keeping the discussion about the suttee open.

The institution of suttee in Pampa and northern Patagonia still requires a deeper analysis to identify its meaning as part of the Indigenous social logic and the specific contexts in which it took place. However, we believe that the journey made here allows us to argue that this practice was linked to three aspects of Indigenous culture: the belief in death as a trip to Allhue Mapu, or land of souls; the asymmetry of gendered power relations in favor of the husband; and the prestigious position of caciques and capitanejos within the Indigenous political-military hierarchy.

Our review of sources produced during the second half of the nineteenth century reinforces the presence within Mapuche society of practices and values associated with the living accompanying the dead on their journey to Allhue Mapu. This conception of death is linked, in all these examples, with another one related to gender that leads women to occupy—voluntarily or not—the place of sacrifice.

After traveling through the territories of Chief Sayhueque, Moreno (Reference Moreno1999 [1879]:134) pointed out that Indian women “frequently look to commit suicide so as to accompany their dead husband,” although “men never imitate them, or at least I have never heard of a single example.” Hux points out that, according to the oral tradition of the descendants of Coliqueo, when this chief died, the custom that forced the wife to accompany her husband on his journey after death was about to be implemented; however, his wife was alerted and managed to escape to the next town of Bragado and so avoided being sacrificed (Reference Hux2009:256–257). There is also a reference from Captain Rufino Solano, who was asked by Calfucurá on his deathbed to take the captive women away before they could be sacrificed (Hux Reference Hux2004).

Discussion

Chronology and Context of the Chimpay Site

The information presented here allows us to link the Chimpay burial with the Mapuche chiefdoms of the nineteenth century—either with the Indigenous population who traveled the path from the Buenos Aires border to the Andes or those who settled in Chimpay during the final stages of the Conquista del Desierto. In the first case, the island of Choele Choel—located 25 km downriver from Chimpay—was the main node of this traffic during the nineteenth century, and the paths were located on both sides of the Negro River. If the second possibility is correct, during the militarization of the Indigenous population in the 1880s, many such groups were provisionally located in the place where the grave was found. Among them, the members of Chief Manuel Namuncurá's tribe remained the most stable between 1884 and 1896. The analyzed documents do not allow us to give more weight to either of the two options.

Mapuche Filiation of the Burial

The features of the burial—the orientation and positioning of the body, as well as the funerary accompaniment—correspond to those of the Indigenous graves described for the Arauco-Pampean region in nineteenth-century sources. Specifically, we are referring to the orientation of the head toward the west, the disposition of the body with the limbs extended, and the presence of three types of funerary accompaniment: clothing and ornaments, objects important to the deceased or useful to demonstrate their position or hierarchy, and—in the case of the man—food and drink. The positioning of the man, with limbs extended and grave goods neatly positioned on both sides of his body, seems compatible with his being wrapped in leather or inside a casket and buried in a pit. In the case of the woman, her positioning is disordered—semi-flexed knees, misaligned shoulders, and rotated neck—and does not seem compatible with a burial in leather wrapping. Yet the analyzed documents suggest the use of this kind of wrapping for transporting the body when the place of death did not correspond to the place of burial. All the described characteristics not only fit well with those seen in other Mapuche burials on Pampa-Patagonia (Casamiquela and Noseda Reference Casamiquela and Noseda1970; Hajduk and Biset Reference Hajduk, Biset and Otero1996; Oliva et al. Reference Oliva, L'Heureux, De Angelis, Parmigiani, Reyes, Oliva, de Grandis and Rodríguez2001) but also differ from those of the graves in the Negro River not linked to the Mapuche chiefdoms, in which bodies are generally flexed and have no funerary accompaniment (Prates and Di Prado Reference Prates and Prado2013).

Hierarchy and Prestige Position of the Buried Individuals

Regarding the hierarchy or social position of the individuals, the man seems to have fulfilled an important political or military role or both—a chief or a capitanejo—which is congruent with the effort to highlight his privileged position through funerary accompaniment, the uniform, and possibly the sword buried alongside him. Generally, only Indigenous political representatives who negotiated treaties with the Argentine government and who were given military positions and uniforms of the national army could have access to this kind of attire. Except for the presence of a brooch made of an eighteenth-century coin—an object that was not a common possession among the Indigenous population—the accompanying goods do not seem to be very costly. This is in contrast to the descriptions in the chronicles, which note the incorporation in the grave of numerous silver objects, especially of the ornaments on the horse that made the deceased's mount such a symbol of prestige. However, and as the sources from the later decades of the frontier interethnic relationships also demonstrate, the relative poverty of the Indigenous peoples and the grave robbing perpetrated by the army that was advancing over their territories led to their not placing those kinds of goods in the graves (Flores Chávez Reference Flores Chávez2013). Other sources also point to the decline in the custom of sacrificing animals during the decade before the state conquest (Barbará Reference Barbará2000 [1879]). If a horse had been sacrificed in Chimpay during the funerary ceremony, there would be no way to prove it, because the bones could have been not preserved in the archaeological record; these animals were normally (but not always; see Casamiquela and Noseda Reference Casamiquela and Noseda1970) left on the surface, next to the grave or on top of it. In the woman's case, and in contrast to what was stated earlier (Prates et al. Reference Prates, Serna, Mange and de Jong2016), a prestigious social position cannot be directly inferred from the grave goods, because burying women with their formal dress and the tools associated with activities linked to her gender was a generalized practice at the time in the region.

Incorporation of the Woman in the Context of the Burial

The incorporation of dead women in the burial ceremonies of individuals who had held a position of military and political command could be related to the sacrifice of one or more wives, so that they would accompany the deceased in his life after death. In the Chimpay burial, the disposition of the female body in close association to the man and to varied grave goods aligns with the documents’ descriptions of the sacrifice of the first (or most valuable) wife of the man, so she could keep him company on his journey to Allhue Mapu (suttee, according to González [Reference González1979]). Accounts of the burial ceremonies of Indigenous leaders of the nineteenth century describe the sacrifice of the deceased's wives so they could be incorporated as part of their belongings, which reflects the strong gender asymmetries in the Mapuche chiefdoms of the nineteenth century. As Goicovich (Reference Goicovich Videla2003:173) points out, women were considered a possession of their husbands. Their value depended on their ability to increase the power and prestige of the husband through the production of a surplus (food, ponchos, drink) to be offered in reciprocity or as gifts. The differences observed in Chimpay in the disposition of the woman in relation to the man—she was lying face down, with no food nor drink offerings, and with her body in a disordered position relative to that of the man—may be linked to her secondary role in the burial ritual and her incorporation as part of the man's funerary accompaniment. It was common for at least some of the wives of Mapuche to be older than their husbands. In some cases, this was because the firstborn inherited not only the position and the goods of his father or brothers but also their women (Bechis Reference Bechis and Bechis2010). In fact, as is concluded from the quoted sources, it was often the oldest or the most precious of the wives who was sacrificed.

Conclusions

We analyzed extensive ethnohistoric information as a means to interpret the mortuary site of Chimpay's archaeological context. Taking into account the geographical and chronological background, we estimate that the burial ritual happened in the context of the nineteenth-century Mapuche chiefdoms; it occurred possibly at the time of the Indigenous settlement of Chimpay, where Chief Namuncurá and his followers were established after he surrendered in 1884. Most of the features of funerary rituals inferred from the site fit well with the customs of the Mapuches living in Pampa, northern Patagonia, and the Araucanía during the nineteenth century. The military attire of the male individual most likely implies that he was a person of high position in the Indigenous military-political hierarchy. Although the funerary accompaniments do not contain objects of much value (such as silver items), this is likely due either to the decadence of the chiefdoms at the time of this burial (at the end of the nineteenth century) or fears that the grave would be looted. The crisis generated by the territorial expansion of the state, the subjugation of local populations, and missionary action did not imply necessarily an immediate termination of all of the Mapuche religious customs. The sacrifice of women during funerary ceremonies of male leaders could have been continued because of the gender asymmetry in favor of males and cultural principles around death in the Mapuche chiefdom. Moreover, as stated by Bechis (Reference Bechis and Bechis2008b), this kind of practice could have been also used by men as a political strategy to demonstrate, validate, and enhance their political leadership. Finally, based on the analysis of ethnohistorical information and considering the geographical, historical, and archaeological contexts of the double burial of Chimpay, we suggest that the suttee (or ritual sacrifice of an individual to accompany or provide service to the deceased in the afterlife) would explain this unusual finding. Although our evidence is not conclusive, we consider that the ritual of the suttee would have been still in practice as an ongoing custom in northern Patagonia during the nineteenth century.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Daniel Cabaza, director of the Museo Paleontológico Municipal de Lamarque, and Tranquilo Zaccaria, owner of the farm where the site of Chimpay is located, for their extraordinary support. Financial support for the research was provided by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT-2014-2209, PICT-2015-3645) and CONICET (PIP-0244/15, PIP-265/15); research permission for doing fieldwork was provided by the Secretaría de Cultura de la provincia de Río Negro.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were presented in this article.