In this study, samples of organic and conventional bulk milk, destined for the production of Grana Padano cheese, were analyzed at different times between summer 2004 and summer 2005 for CLA level and fatty acid composition. The respective organic and conventional curds and Grana Padano cheeses were also analyzed. The aims of the present survey were to compare the CLA contents of organic milk and milk products with those obtained by a conventional management system and to evaluate effects of the Grana Padano production technology on CLA content.

Conjugated linoleic acids (CLA), a group of conjugated linoleic acid isomers, have been reported to have a wide range of beneficial effects, including: anticarcinogenic, antiatherogenic, antidiabetic and immune stimulatory (Nagao & Yanagita, Reference Nagao and Yanagita2005; Collomb et al. Reference Collomb, Schimd, Sieber, Wechsler and Ryhänen2006). They have also been shown to alter nutrient partitioning and lipid metabolism, and reduce body fat in a number of different animal species (DeLany & West, Reference DeLany and West2000; Dugan et al. Reference Dugan, Aalhus and Kramer2004).

Milk fat, cheese and ruminant meat are an important source of potential anticarcinogens from the naturally occurring CLA. Cis-9, trans-11-octadecadienoic acid is the major isomer (80–90%) (Sehat et al. Reference Sehat, Rickert, Massoba, Kramer, Yurawecz, Roach, Adolf, Morehouse, Fritsche, Eulitz, Steinhart and Ku1999). CLA in ruminant milk arises both directly and indirectly from incomplete microbial hydrogenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the rumen. It is formed in the rumen by anaerobic bacteria as an intermediate in the biohydrogenation of linoleic acid (LA) and from desaturation of vaccenic acid (trans-11 C18:1, TVA) in the mammary gland via Δ9-desaturase (Bauman et al. Reference Bauman, Baumbarg, Corl, Griinari, Garnsworthy and Wiseman2001).

The concentration of CLA in milk has been reported to vary considerably through the animal diet; high CLA values were found with pasture feeding, organic diet and diet supplemented with plant or marine oils (Bergamo et al. Reference Bergamo, Fedele, Iannibelli and Marzillo2003; Lock & Garnsworthy, Reference Lock and Garnsworthy2003; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Liu, Yao, Yuan, Ye, Ye and Wu2005; Shingfield et al. Reference Shingfield, Reynolds, Hervas, Griinari, Grandison and Beever2006; AbuGhazaleh & Holmes, Reference AbuGhazaleh and Holmes2007).

In cheese the CLA content is certainly affected by specific features of the milk used in manufacturing, with special reference to the species and the CLA content of the milk (Prandini et al. Reference Prandini, Geromin, Conti, Masoero, Piva and Piva2001, Reference Prandini, Sigolo, Tansini, Brogna and Piva2007), whereas the role of processing technology on CLA content of cheese is still controversial (Werner et al. Reference Werner, Luedecke and Shultz1992; Shanta & Decker, Reference Shanta and Decker1993; Gnädig et al. Reference Gnädig, Chamba, Perreard, Chappaz, Chardigny, Rickert, Steinhart and Sebedio2004; Bisig et al. Reference Bisig, Eberhard, Collomb and Rehberger2007).

Materials and Methods

Animal feeding and sample collection

Grana Padano is an important PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) Italian cheese produced throughout Northern Italy and details of manufacturing technology are available at website of Dairy Science and Food Technology http://www.dairyscience.info/htm/grana.asp.

The samples of bulk milk, curds and cheese (both conventional and organic) were supplied by a dairy industry adhering the Consorzio per la Tutela del Formaggio Grana Padano (S. Vittoria Soc. Coop. a r.l.) situated in the plain of the province of Piacenza. On the basis of known animal dietary rations, cow daily intakes of CLA precursor fatty acids (α-linolenic and linoleic acids) were estimated using literature data of feed fatty acid composition: corn silage and concentrate (Elgersma et al. Reference Elgersma, Ellen, Van Der Horst, Boer, Dekker and Tamminga2004), fresh alfalfa and alfalfa hay (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Karnati and Eastridge2005), corn (White et al. Reference White, Pollak and Duvick2007) and barley (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Newman, Newman, Jackson and Hofer1993).

In conventional farming system the cows (Italian Holstein) were fed during all year with a mixed ration consisting of corn silage (20–26 kg/head/day), alfalfa hay (4–6 kg/head/day) and concentrates (9–12 kg/head/day). The daily intakes of α-linolenic and linoleic acids were an average of 81 and 217 g, respectively (total CLA precursor fatty acids=298 g).

In organic farming system the cows' feeding was based on alfalfa pasture in late spring-summer and on alfalfa hay in late autumn-winter. The remaining diet consisted of concentrates (3 kg/head/day) and cereals (2 kg/head/day; barley:corn=50:50). The daily intakes of α-linolenic and linoleic acids in the spring-summer periods were an average of 279 and 134 g, respectively (total=413 g), whereas in the autumn-winter periods were an average of 141 and 106 g, respectively (total=247 g).

The samples of conventional and organic bulk milk were collected at monthly intervals between August 2004 and July 2005 (excluding January and March 2005) and were analyzed for CLA content and fatty acid composition. The respective conventional and organic curds, obtained from the coagulation of raw cows' milk by the addition of bovine liquid rennet, were also analyzed both before and after cooking at 53–56°C and as well as the Grana Padano cheeses aged 12 months.

The samples were frozen at −18°C after sampling and defrosted before analysis. All analysis were effected in duplicate and carried out on samples of finely ground cheese and curd.

Chemical analysis

Lipid extraction was performed according to the ‘Röse-Gottlieb method’ (FIL-IDF 1A:1969) for milk samples and in cold conditions in accordance with the modified Folch's technique (Christie, Reference Christie1989) for cheese and curd samples. The lipids were then esterified according to the method described by Bannon et al. (Reference Bannon, Craske and Hilliker1985) with modifications.

CLA and fatty acid methyl esters were quantified using a GC (Varian 3350) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a CP-Select CB capillary column for FAME (100 m×0·25 mm i.d.; 0·25 μm film thickness; Chrompack, Varian, Inc., CA). GC oven parameters, gas variables and fatty acid peak identification were as previously described (Prandini et al. Reference Prandini, Sigolo, Tansini, Brogna and Piva2007).

Milk, curds and cheese CLA content and fatty acids were expressed as g/100 g of total fatty acids, calculated with peak areas corrected by factors according to AOAC 963.22 method (AOAC, Reference Horwitz2000).

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as annual averages. The simple analysis of variance according to the SAS® technique (SAS/STAT, version 8, 2000, SAS Inc., Cary, NC) was effected for fatty acid composition found in the different milk and milk products. The significance of the differences between means was evaluate taking P<0·05 as significant.

Results and Discussion

CLA level in bulk milk, curds, Grana Padano cheese

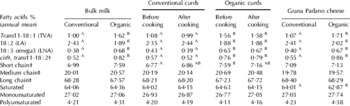

Gas-chromatographic analysis of FAME considered only the cis-9,trans-11 CLA isomer among all isomers of CLA. The cis-9,trans-11 CLA levels were expressed in g/100 g total fatty acids. Table 1 reports the annual average content of CLA in bulk milk, curds before and after cooking to 53–56°C and Grana Padano cheese, produced by conventional and organic system. In the different sampling dates all the organic samples were characterized by higher cis-9,trans-11 CLA levels than those measured in the respective conventional dairy products (data not shown) with statistically significant differences (P<0·05) between the annual means.

Table 1. Partial fatty acid composition (annual mean) and CLA level of conventional and organic bulk milk, conventional and organic curds before and after cooking to 53–56°C, and conventional and organic Grana Padano cheese. Fatty acids are expressed as g/100 g total fatty acids

† Conjugated linoleic acid

‡ Short chain fatty acids (C 4:0 – C 9:0); Medium chain fatty acids (C 10:0 – C 15:1); Long fatty acids (C 16:0 – C 22:6 omega3)

Different letters in the same line correspond to statistically significant differences (P<0·05) between conventional and organic samples of the same type (Bulk milk, Curds and Grana Padano cheese)

No particular variation of CLA content was detected in the conventional and organic curds after the cooking. Furthermore, similar annual means of CLA content were found in the bulk milk and respective curds; only the conventional curds before heat treatment were characterized by an annual average of 18·76% significantly higher (P<0·05) compared with that of conventional bulk milk (statistical analysis not shown).

The annual averages measured in conventional and organic Grana Padano cheese were similar to those of the conventional and organic curds after cooking.

The CLA percentages found in the conventional and organic samples of bulk milk, curds and Grana Padano cheese show negligible effects of cheese cultures, processing conditions and aging period on the CLA level in accordance with Werner et al. (Reference Werner, Luedecke and Shultz1992), Jiang et al. (Reference Jiang, Björck and Fondén1997), Gnädig et al. (Reference Gnädig, Chamba, Perreard, Chappaz, Chardigny, Rickert, Steinhart and Sebedio2004), Nudda et al. (Reference Nudda, McGuire, Battacone and Pulina2005) and Ryhänen et al. (Reference Ryhänen, Tallavaara, Griinari, Jaakkola, Mantere-Alhonen and Shingfield2005). The major contents of CLA measured in milk and milk products obtained from an organic management system, characterized by higher cows' intakes of CLA precursory fatty acids than a conventional management system, were in accordance with Jahreis et al. (Reference Jahreis, Fritsche and Steinhard1997) and Bergamo et al. (Reference Bergamo, Fedele, Iannibelli and Marzillo2003).

These results suggest that the CLA concentration in dairy products depends mainly on CLA content of the milk used in manufacturing. Variation in CLA content in milk has been associated with several factors such as stage of lactation, parity (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Kolver, Bauman, Van Amburgh and Muller1998), and breed (Secchiari et al. Reference Secchiari, Mele, Serra, Buccioni, Antongiovanni, Ferruzzi, Paoletti and Andreotti2001; White et al. Reference White, Bertrand, Wade, Washburn, Green and Jenkins2001). However diet is the most important factor influencing milk CLA concentrations (Collomb et al. Reference Collomb, Butikofer, Sieber, Jeangros and Bosset2002). Some authors reported higher CLA concentrations in the milk of cattle fed with hay or grass (e.g. Lock & Garnsworthy, Reference Lock and Garnsworthy2003; Chilliard & Ferlay, Reference Chilliard and Ferlay2004) and an increase of CLA content was found in cows' milk receiving fibre-rich diets by Dhiman et al. (Reference Dhiman, Arnand, Satter and Pariza1999). Therefore, an organic diet, containing at least 60% of the dry matter of roughage, fresh or dried fodder (EC Reg. 2092/91 and 1804/99), may well improve microbial biohydrogenation, yielding higher concentrations of CLA compared with a conventional diet.

Fatty acid composition of bulk milk, curds, Grana Padano cheese

Also reported in Table 1 are the partial fatty acid compositions (annual means) of bulk milk, curds before and after cooking to 53–56°C and Grana Padano cheese, produced by conventional and organic system.

Bulk milk

Similar contents of short, medium and long chain fatty acids and of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids were detected in conventional and organic bulk milk. The organic bulk milk showed higher percentages of vaccenic acid (TVA=1·62%) and α-linolenic acid (LNA=0·68%) and a lower percentage of linoleic acid (LA=1·89%) with statistically significant differences (P<0·05) versus conventional bulk milk.

Curds

The conventional and organic curds were characterized by a fatty acid composition similar to that of the corresponding bulk milk. A statistically significant difference (P<0·05) was found between mean content of short chain fatty acids in conventional curds (6·77%) and that in organic curds (7·59%) both before cooking. The organic curds showed higher levels of TVA and LNA before and after heat treatment and lower levels of LA in comparison with conventional curds with statistically significant differences (P<0·05). Particular variations of fatty acid composition were not detected in the curds after cooking to 53–56°C.

Grana Padano cheese

No particular variation of fatty acid composition was seen among curds after cooking and respective Grana Padano cheeses except a statistically significant decrease (P<0·05) in the percentage of saturated fatty acids in organic Grana Padano cheese (62·87%) compared with organic curds (64·15%). Furthermore, organic Grana Padano cheese showed a lower content of saturated fatty acids (62·87%) than that of conventional Grana Padano cheese (64·01% with P<0·05). In organic Grana Padano higher percentages of TVA and LNA and lower LA content were detected compared with those found in conventional Grana Padano (P<0·05).

A negligible influence of the milk processing on the fatty acid composition of organic and conventional dairy products was seen. The major contents of TVA and LNA and the minor content of LA found in organic milk and milk products were in accordance with Bergamo et al. (Reference Bergamo, Fedele, Iannibelli and Marzillo2003). In their study, carried out on fatty acid composition and fat-soluble vitamin concentrations in organic and conventional Italian dairy products, organic management resulted in the production of milk containing improved CLA, TVA and LNA concentrations. Therefore, considering the positive effects of these fatty acids on the human health (Nagao & Yanagita, Reference Nagao and Yanagita2005), the nutritional value of dairy foods from cows fed diet with fresh forage and/or hay in an organic system seem to be higher than that of conventional products.

Conclusions

The current study shows that organic milk and milk products are characterized by higher amounts of CLA, TVA and LNA in comparison with conventional milk and milk products. The lactic acid bacteria added to the milk in the production Grana Padano cheese, the processing technology, particularly heat treatment, and the aging do not appear to influence the CLA content in dairy products. Therefore, the animal diet is the factor which most affects the CLA content in milk and the CLA concentration in dairy products depend on the milk used in manufacturing. An organic diet based on fresh or dried forage, that is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, may remarkably improve the CLA yield in milk fat and so increase the nutritional quality of organic dairy products.