Introduction

Frontiers may be understood as spatial counterparts to revolutions: the one denotes a perceived break in continuous territory, the other a perceived rupture in time. In recent decades, historians have written of a worldwide military, or ‘gunpowder’ revolution that took place in the centuries following the fourteenth.Footnote 2 Such a notion has in turn prompted several lines of enquiry. Some have tried to locate the moment in time when this revolution occurred in particular regions.Footnote 3 Others have sought to identify and compare the various effects that the advent, spread, and use of gunpowder had in different socio-political environments across the planet.Footnote 4

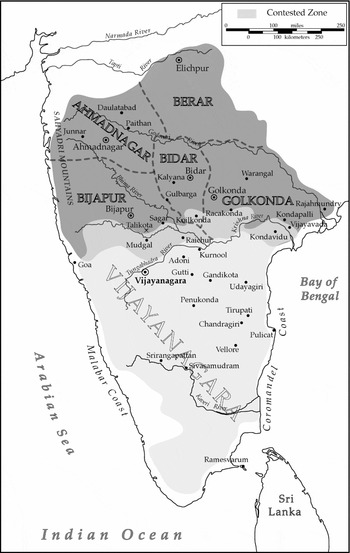

The present essay explores a little-studied event in South Asian history, the Battle for Raichur (1520), with a view to evaluating that battle's relevance both to the idea of the frontier and to that of the military revolution. The city of Raichur occupies the heart of an exceptionally fertile tract in India's Deccan plateau—the so-called ‘Raichur Doab’—which lies between the Tungabhadra and Krishna rivers (see Figure 1, Map). For several centuries before 1520, the Bahmani sultans to the north of the Doab and the kings of Vijayanagara to the south repeatedly fought over access to the Doab's economic resources.Footnote 5 Control of the fortified city of Raichur figured in all of these struggles. The battle in question was also a prelude to the more famous Battle of Talikota (1565), a conflict that permanently reconfigured the geopolitics of the Deccan plateau. One question, then, is temporal in nature: how did this battle stand out in the long-term struggle for control of the Doab, and how might it have figured in a ‘military revolution’ in India? The other question is spatial: in what ways did that battle define Raichur's frontier character?

Figure 1 Map of the Deccan.

Background

The Raichur Doab had been a contested region even before the Bahmani and Vijayanagara states came into being. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the tract lay at the conjuncture of three regional powers—the Hoysala kings of Dwarasamudra, the Yadava kings of Devagiri and the Kakatiya kings of Warangal. In 1294 a subordinate of the last monarch of the Kakatiya dynasty seized the Raichur Doab from Yadava control and built the imposing complex of walls and gates that encircle Raichur's present core. With their massive slabs of finely dressed granite, these walls were, in their own day, considered an engineering marvel; even today, some local residents regard them as the work of gods, not men. They are certainly the most impressive of any Kakatiya fortifications still standing, apart from those in Warangal, the dynasty's capital.

Notwithstanding its strength, Raichur's fort got swept into the general chaos that engulfed the Deccan in the early fourteenth century following invasions by the armies of the Delhi Sultanate. After the collapse of the Kakatiya state in 1323, Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq (r. 1325–51) systematically colonized much of the northern Deccan with settlers transplanted from north India. At the same time, he sub-contracted the governance of much of the central and southern Deccan to local client-chiefs. Administration of the Raichur Doab appears to have been assigned to a chief who, appointed amir (commander) by the Delhi sultan in 1327, led an anti-Tughluq uprising nine years later. This rebel amir was likely Harihara Sangama, a Kannada chieftain known to have been in Tughluq imperial service in the 1330s.Footnote 6 By 1347, when Delhi lost control of all its Deccan possessions to anti-Tughluq rebels, Harihara and his brothers had carved out a new state centred on the city of Vijayanagara, located directly south of the Raichur Doab on the southern banks of the Tungabhadra river.

Raichur, however, did not long remain in southerners' hands. In the confusion surrounding the expulsion of imperial forces in 1347, the Doab apparently fell to the other power that simultaneously arose on the ashes of Tughluq imperialism in the Deccan, the Bahmani sultanate (1347–1538). Ruling from a series of capitals located to the north of the Raichur Doab—Daulatabad, Gulbarga and Bidar—the Bahmani sultans claimed the territory clear down to the Tungabhadra river, which included the Raichur Doab. Yet the fact that Vijayanagara's founders seem to have held the Doab before Vijayanagara's creation formed an important basis for the southern state's repeated claim to the tract. For the next century and a half, rulers of Vijayanagara and the Bahmani sultanate fought bitterly for the control of this agriculturally rich tract. For most of this period, however, the greater part of the Doab remained under Bahmani control, despite major invasions launched by Vijayanagara kings in 1362, 1378, 1398 and 1443.Footnote 7 From 1444, and possibly from as early as 1398, those kings were even forced to make annual tributary payments to the Bahmani treasury.Footnote 8

In 1468 and 1469, capitalizing on new engineering technology imported from north India and the Middle East, Bahmani authorities built an entirely new wall around Raichur's old Kakatiya fortifications, complete with an outer moat, numerous bastions and imposing gates on the city's eastern and western ends.Footnote 9 Ironically, though, by this time the dynasty had begun experiencing crippling factional struggles within its ruling elite. On one side were ‘Deccanis’, or nobles descended from the original north Indian migrants who had settled in the upper Deccan in the 1320s. And on the other were the so-called ‘Westerners’ (gharbian), or immigrants freshly recruited from the Middle East, especially the Persian-speaking world of Iran and Central Asia.Footnote 10 Sectarian rivalries reinforced ethnic and linguistic differences between the two factions, as most Westerners were Shi'i Muslims, and most Deccanis were Sunnis.

By the 1480s and '90s Deccani–Westerner tensions had so intensified that the Bahmani sovereign, Sultan Mahmud (r. 1482–1518), could no longer command absolute loyalty among his most powerful nobles, some of whom began establishing de facto independent states within his domain. One of these was Yusuf ‘Adil Khan, a Westerner immigrant from Iran who, in 1490, carved out a new state of Bijapur from the Bahmani sultanate's western and southern districts, which included the Raichur Doab. Although Yusuf continued to pay formal homage to Sultan Mahmud, his audacious actions alarmed other independent nobles, one of whom sought to weaken Bijapur's position by inviting Vijayanagara's forces to invade Raichur. Accordingly, in 1492 the southern state invaded the Doab and momentarily seized Raichur city, although Yusuf ‘Adil Khan managed to retrieve the fort later the same year. Until as late as 1515, Sultan Mahmud's name continued to appear on Raichur's inscriptions as the region's legitimate sovereign, maintaining the fiction that Yusuf ‘Adil Khan and his successors in Bijapur were merely Bahmani ‘governors’. Nonetheless, Bijapur's rulers from Yusuf on behaved as though they were independent sultans, as indeed later chroniclers styled them.Footnote 11

Despite prolonged northern hegemony over the Raichur Doab, by the first decade of the sixteenth century the balance of power began to tilt towards the south for the first time since 1347. Already, by 1500, the integrity of the Bahmani state had become seriously compromised, and by the second decade of the sixteenth century, the kingdom had disintegrated into five de facto successor states. This meant that any invasion of Raichur from the south would now be met not by the full might of the old Bahmani sultanate, but by the ‘Adil Shahi rulers of Bijapur, who could field armies only a fraction the size of those of its parent state. What is more, Bijapur inherited the same Westerner-Deccani factionalism that had plagued the Bahmani sultanate, which compromised its socio-political cohesiveness.

To the south of Raichur, meanwhile, a vigorous new dynasty of kings, the Tuluva, had arisen in the sprawling metropolis of Vijayanagara. In 1509 Vijayanagara's throne was occupied by the famous Krishna Raya (or ‘Krishna Deva Raya’, r. 1509–29), whose twenty years of rule are widely acclaimed as having seen the acme of Vijayanagara's power and glory. Between 1509 and 1520, while the Deccan north of the Raichur Doab fragmented into five mutually quarrelling states, Krishna Raya conquered and annexed the entire peninsula from the southern edge of the Raichur Doab nearly to Cape Comorin, thereby amassing immense manpower and capital resources available for any effort to regain from Bijapur the control of the Doab.

Another factor tipping the balance of power in Vijayanagara's favour at this time was the advent of the Portuguese Estado da India. A formidable coastal power since 1498, these European newcomers not only sought to monopolize control over the Arabian Sea commerce. Arriving on the heels of Iberia's anti-Muslim reconquista, the Portuguese in India also sought to roll back Muslim states everywhere, and especially the newly emerged Sultanate of Bijapur, which had inherited from the Bahmanis control over a good deal of India's western seacoast in addition to the Raichur Doab. Such objectives naturally inclined the Portuguese to seek allies in Vijayanagara, that being the Deccan's principal non-Muslim power, and to exploit that kingdom's hostility towards Muslim states to its north.

A dramatic step in this direction was taken in 1510, when the Portuguese viceroy and master strategist Afonso de Albuquerque (1509–15), assisted by a coastal warlord loyal to Vijayanagara, seized the port of Goa from Bijapur's Yusuf ‘Adil Khan. ‘With this action in Goa’, the viceroy wrote triumphantly to Portugal's King Manuel,

we can diminish the credit that is enjoyed by the Turks [i.e., Bijapur], and the fear in which they are held, and persuade them [Vijayanagara] that we are men who can do deeds as great on the land as on the sea. . .. [Let us] thus see if I can have them move their armies against the Turks in the Deccan, and desire our true friendship.Footnote 12

The key to Albuquerque's newly acquired leverage over the states of the Deccan interior, both to the north and to the south of the Raichur Doab, lay in those states' dependency on warhorses imported by sea from the Middle East. Before 1510, Bijapur had imported most of its warhorses through its port of Goa, whereas Vijayanagara imported its horses through ports further down the coast, in particular Bhatkal. But after 1510, by negotiating separately with Yusuf ‘Adil Khan and Krishna Raya, by seizing the port of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf (1515) and by deploying his sea power to pressure the merchants of Bhatkal, Albuquerque hoped to drive the entire traffic in warhorses to Goa, and thus through the hands of the Estado.Footnote 13

The Portuguese also introduced new forms of gunpowder technology to the Deccan. The extent of their influence in this regard, however, depends on how one evaluates the state of Indian firearms before their arrival. Gunpowder had certainly been in use in India before the advent of the Estado. We know, for example, that in 1472 Bahmani engineers deployed explosive mines while besieging the fort of Belgaum, an ally of Vijayanagara.Footnote 14 But the move from exploding mines to firing cannon or matchlocks represents a major advance in military technology. Iqtidar Alam Khan has argued that Indians were using cannon cast in brass or bronze and handguns in the second half of the fifteenth century.Footnote 15 But the matter is complicated. The nomenclature of weapons changed over time; few Indian sources are contemporary with the battles they describe; and later sources often used terms anachronistically, projecting the terms of their own day backwards to earlier periods. In view of such considerations, Jos Gommans doubts Iqtidar Alam Khan's assertions respecting a fifteenth-century horizon for the earliest appearance of firearms in India.Footnote 16

Notwithstanding Gommans's reservations, there is evidence that firearms were being used in western India before the establishment of Portuguese power in the region. Gaspar Correia records that in 1502 Portuguese naval squadrons were bombarded from the hilltop overlooking the port of Bhatkal.Footnote 17 According to the historian Firishta, gunners and rocketeers were among the 5,000 foot soldiers that Sultan Ahmad Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar used on a 1504 military expedition into Khandesh.Footnote 18 About the same time, the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema recorded seeing artillery in the port of Chaul, then controlled by the same ruler.Footnote 19 In Bijapur, following the death of Yusuf ‘Adil Khan in 1510, a palace struggle broke out between the royalists supporting the king's youthful son Isma'il and the latter's regent. Both sides in the conflict reportedly used firearms. Firishta speaks of ‘matchlockmen’ (tufangi), and of ‘the fort's large cannon being brought up’ in order to batter down the citadel's walls.Footnote 20 Albuquerque's son noted that when his father took Goa, also in 1510, Bijapuri defenders greeted the invaders with artillery fire.Footnote 21 Later that same year, after first losing and then reconquering the city, Albuquerque captured from Bijapur's defenders a hundred large guns (bombardas) and a ‘large quantity’ of smaller artillery.Footnote 22

It appears, moreover, that many if not most of these weapons were locally manufactured, for when they seized Goa, the Portuguese found that the Bijapuris had already established their own munitions plant there.Footnote 23 In fact, Albuquerque was so impressed with Goa's gun-making tradition that he sent to the king of Portugal samples of the heavy cannon used by the Muslims of that city, together with the moulds from which the guns had been cast.Footnote 24 On 1 December 1513, the Viceroy reported that the matchlocks manufactured by Goa's master gunsmiths were as good as those made in Bohemia; he even sent one of those gunsmiths to Lisbon to work for the Portuguese crown.Footnote 25 Several days later, Albuquerque reported to the king that the Muslim gunsmiths, who had formerly served the ‘Adil Shahis but returned to Goa after the Portuguese conquest, were capable of turning out iron cannon and matchlocks of a higher quality than anything produced in Germany, then considered the source of Europe's finest guns.Footnote 26 From this point on, a tradition of German and Bohemian gun making that had been brought to India by the Portuguese seems to have merged with Turkish gun-making traditions already present in ‘Adil Shahi Goa, producing what has been called an ‘Indo-Portuguese’ tradition of matchlocks. These weapons, evidently superior to anything produced elsewhere in India, would soon spread not only into the Deccan interior but, by the mid-sixteenth century, throughout Portuguese Asia as far as Japan.Footnote 27

These important developments notwithstanding, before 1520 we hear of no major battles in which firearms were used in the Deccan, or indeed, anywhere else in the Indian interior. All this would change with the Battle of Raichur.

The Battle

Krishna Raya of Vijayanagara soundly defeated Isma'il ‘Adil Khan in the 1520 contest for control of Raichur fort and the Doab.Footnote 28 Two original authorities can guide us in reconstructing the contours of the struggle. One is the above-mentioned Firishta, who lived in Bijapur and in 1611 dedicated his monumental Tarikh-i Firishta to Isma'il's great grandson, Sultan Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah II (r. 1580–1627). The other is Fernão Nunes, who around 1531 wrote a chronicle of Vijayanagara kings based on local traditions and his own interactions with the Portuguese and Indians.Footnote 29 There is evidence that Nunes, a Portuguese horse trader who resided in metropolitan Vijayanagara for three years, had been living in coastal India since 1512, in which case he would have heard first-hand reports of the battle shortly after its conclusion.Footnote 30 Or, he might have recorded remembered traditions some eight years later, most likely from participants. It is even possible that he witnessed the battle himself.Footnote 31

Firishta is the less trustworthy of the two sources, not only because he was writing about ninety years after the fact, but because he had the unenviable task of accounting for the crushing defeat of his patron's own forebear. In his version of events, Isma'il ‘Adil Khan in 1520 took an army of 7,000 cavalry, all Westerners, down to the northern shore of the Krishna river in order to recover Raichur and Mudgal from Krishna Raya.Footnote 32 On learning of these manoeuvres, the Vijayanagara king brought up a much larger cavalry of 50,000 to the southern shores of the same river, seizing control of its ferries. Firishta here introduces the factor that doomed Isma'il's enterprise to failure. While the sultan was reposing in his tent soon after pitching camp, a Bijapuri courtier proposed a drinking bout. Isma'il responded enthusiastically and got so thoroughly inebriated that he decided to cross the river and attack Krishna Raya at once. Although his officers pleaded for more time to build sufficient boats and rafts for the operation, Isma'il ignored the advice and, mounting his elephant, rode straight to the river and plunged into the water, ordering his officers and soldiers to follow. On reaching the opposing side, however, the Bijapuris confronted a huge body of cavalry and also, so Firishta writes, cannon, matchlocks and rockets.Footnote 33 Isma'il now found himself trapped between two Krishnas: before him the king of Vijayanagara, and to his rear the swirling currents of the Krishna river. In panic and disorder, the Bijapuris retreated and tried to re-cross the river, in the process losing many men both to drowning and to the arrows and shot of Vijayanagara's pursuing forces. Isma'il, who himself barely survived the debacle, sank into deep remorse for his rashness and swore off wine for good.

Firishta thus framed his story as a morality play, the essential point being that the debacle had been the fault of the wine, or rather, Isma'il's weakness in succumbing to wine at a wholly inappropriate time. Only as an aside does he mention perhaps the most arresting feature of his account, namely, that while Isma'il's retreating men were attempting to re-cross the river, Vijayanagara's forces killed nearly half of Bijapur's army with cannon shot, matchlocks and rockets. We shall bear this in mind as we explore the contemporary, or near contemporary, account of Fernão Nunes.

Nunes's account is far more detailed, less tendentious and, above all, more contemporary with the battle than is that of Firishta. When he assumed the Vijayanagara throne in 1509, writes the Portuguese chronicler, Krishna Raya knew that his royal predecessor Narasimha Tuluva had regretted never having reduced three forts—Raichur, Mudgal and Udayagiri. His opportunity to invade the first two came about ten years into his reign, when he entrusted a Muslim merchant with the sum of 40,000 pardaos to purchase warhorses from Goa. Instead of proceeding to the Portuguese-held seaport, however, the merchant absconded with the money to Bijapur. When the king wrote Isma'il ‘Adil Khan demanding the return of the merchant and the money, the sultan refused to oblige. He even gave the port of Dabhol to the merchant, which so enraged Krishna Raya that he resolved to invade that town. The king's advisors tried to dissuade him, noting that the sum given to the merchant—which would have purchased approximately 120 horses—was too trifling an amount over which to wage a war. But on seeing that the king could not be deterred from invading Bijapuri territory, his advisors counselled invading Raichur rather than Dabhol, since the former city had once belonged to Vijayanagara. Accepting this advice, Krishna Raya in early 1520 moved north with an immense force of 27,600 cavalry and 553,000 infantry. In all, writes Nunes, the army included archers, cavalry using a variety of weapons, matchlockmen (espimgardeiros), swordsmen with shields, war elephants and ‘several cannon’ (allgũs tiros de fogo).Footnote 34

After crossing the Tungabhadra river, the Vijayanagara army camped in the town of Maliabad, an ancient Kakatiya fort situated some ten miles south of Raichur city, and from there it moved on Raichur itself. The city, writes Nunes, was defended with three lines of strong walls of heavy masonry made without lime-mortar and packed with earth inside. Built into the outer walls were bastions positioned so close to one another that men posted on them could hear the words spoken by those on neighbouring bastions. The defenders used matchlocks (espimgardas) and heavy cannon (tiros de fogo grossos), as well as bow and arrow. Along the walls were mounted thirty stone-hurling catapults (trabucos), 200 heavy cannon and many smaller cannon, all the artillery being positioned between the bastions. Garrisoned inside were 8,000 ‘Adil Shahi foot soldiers, 400 cavalry and 20 elephants.Footnote 35

While deploying his forces around the entire fort, Krishna Raya concentrated his main attack on the city's eastern side, probably near the present Kati Gate. Whereas the fort's defenders fired on Vijayanagara's forces with heavy cannon and matchlocks, together with arrows, the besiegers used no artillery against Raichur's walls. Instead, Vijayanagara's commanders offered their men monetary inducements to go directly to the walls and dismantle them with pickaxes, paying them in sums proportionate to the size of the stones dismantled. They were also paid for dragging off the bodies of comrades killed at the base of the walls. In this slow, dreary manner the siege dragged on for three months.Footnote 36

In early May, while the siege was still in progress, Krishna Raya learned that Isma'il ‘Adil Khan had marched down from Bijapur to relieve the embattled fort and was camped on the northern side of the Krishna river. With him were 18,000 cavalry, 120,000 infantry, 150 elephants, and considerable artillery. Suspending the siege of Raichur, the king moved his entire army up to the Krishna river to prevent the ‘Adil Shahi forces from entering the Doab. The battle between the two armies began several hours after dawn on May 19, 1520 when the sultan, having moved his forces to the southern side of the river, fired all his artillery at once into Vijayanagara's massed front lines. When those lines broke and the ‘Adil Shahi cavalry advanced, Krishna Raya became so desperate that he entrusted his ring to one of his pages, instructing him to show it to his queens as a sign of his death. The king then mounted his horse and moved forward with all of his remaining divisions, driving the Bijapuris back towards, and finally into, the Krishna river. Like Firishta, Nunes reports the horrific slaughter that then occurred by the river, in the midst of which Isma'il ‘Adil Khan jumped on an elephant and barely escaped with his life.Footnote 37

It is clear that Isma'il ‘Adil Khan had brought a great deal of ordnance to the battlefield for, as Nunes reports, his retreating army was forced to abandon 400 heavy cannon and 900 gun carriages—implying that he also had 500 small cannon—in addition to 4,000 warhorses and 100 elephants.Footnote 38 In fact, writes Nunes, Isma'il boldly crossed the Krishna river not because he was drunk, as Firishta would later write, but because he was confident that the great strength of his artillery (a gramde artelharya) would give him a quick victory. Indeed, the sultan's opening barrage did give him temporary field advantage. But Nunes does not report that Krishna Raya used artillery in that battle, although Firishta, as we have seen, did make such a claim. Since Nunes wrote much closer in time to the event than did Firishta, it seems reasonable to conclude that if Krishna Raya used firearms at all on this occasion, they did not play a decisive, or even noticeable, role in the battle's outcome.

This inference is supported by Nunes's account of the siege of Raichur fort, an engagement that Firishta does not even mention, in which the Portuguese chronicler describes Krishna Raya's men clawing at the fort's walls with crowbars, rather than bombarding it with cannon. And in his description of Krishna Raya's immense army during its initial march to Raichur, the king is said to have brought along only ‘several’ cannon. All of this suggests that by 1520 cannon were being used in the field—extensively by Bijapur, at best minimally by Vijayanagara—but with only limited effect. Defensively, whereas cannon were mounted on Raichur's ramparts, they had not yet displaced stone-hurling catapults, which were also still present, fixed atop the fort's projecting bastions. In short, cannon appear to have made a noticeable appearance at Raichur, but they were not yet sufficiently effective as to play a decisive role in the outcomes of military engagements. After all, in Nunes's account, Isma'il possessed and used significant firepower in the battle by the Krishna river, yet he still lost that battle.

Having soundly defeated the Bijapuris on the battlefield, Vijayanagara's army returned to Raichur to resume its siege of the fort. At this point a new factor enters Nunes's narrative—the arrival of twenty Portuguese mercenaries who, led by one Cristovão de Figueiredo, had just joined Krishna Raya's forces at Raichur as matchlockmen (espimgardeyros). Noticing how fearlessly ‘Adil Shahi defenders roamed about the fort's walls, fully exposed to the view of the besiegers, de Figueiredo and his men began picking them off with their guns. Nunes remarks, very significantly, that the defenders ‘up to then had never seen men killed with firearms nor with other such weapons’.Footnote 39 What is more, it seems that the fort's cannon proved ineffective against the besiegers, who continued to assault the fort's walls with crowbars and pickaxes as they had been doing before the battle by the Krishna river. The reason the fort's cannon were ineffective, Nunes explains, had to do with how they were mounted. Being placed high on the curtain walls, they could not fire down on those dismantling the walls at their base. And the defenders who tried to fire on them with arrows, matchlocks, or stones were themselves picked off by de Figueiredo's sharpshooters, allowing Krishna Raya's men to continue dismantling the walls relatively unhindered. This operation was so successful that the defenders were forced to abandon their first line of fortification and place their women and children in the city's hilltop citadel.

Several inferences may be drawn from this part of Nunes's narration. First, although the ‘Adil Shahi defenders were using matchlocks to fend off the besiegers, those weapons must have been inferior to those of de Figueiredo and his men if, as Nunes reports, Bijapuri defenders at Raichur had never before been killed by firearms. This is quite possible, given that de Figueiredo would have had access to the superior firearms that were then being produced in the Goa arsenal, ‘without doubt one of the largest arsenals of the world at that time’.Footnote 40 It was here that, during the early decades of the sixteenth century, the Portuguese and Muslim gunsmiths had been exchanging designs and developing the latest hybrid matchlocks.Footnote 41 Second, the inability of Raichur's cannon shot to reach besiegers at the base of the fort's walls indicates that while the defensive use of cannons on forts had certainly reached the Deccan interior by 1520, engineers had not yet learned how to manoeuvre them so as to screen the walls with flanking fire. Being fixed between the battlement's merlons and not mounted on swivels, the cannon would have been immobile and hence quite useless against besiegers beneath them.

A turning point in the siege was reached on June 14 when the governor of the city, seeking a better view of exactly where the Portuguese snipers were positioned, leaned out in front of one of the embrasures and was instantly killed by a matchlock shot that struck his forehead. This snapped the morale of Raichur's defenders, who promptly abandoned the wall. The next day the Bijapuris opened the city gate and filed out, begging for mercy. All that remained now was a formal ceremony of capitulation and a transfer of authority. That came the following day, when Krishna Raya, after performing his customary prayers, rode into the city accompanied by his highest-ranking officers. Along the way, the townspeople stood awaiting him—although, as Nunes remarks, they bore ‘more cheerful countenances than their real feelings warranted’.Footnote 42 Speaking to a gathered crowd, the king generously assured the city's leaders that their property rights would be respected; he even gave them the option of leaving the city and taking their movable property with them.

Before returning to his capital, Krishna Raya lingered in Raichur for some days making arrangements for the city's new administration. Nunes reports that he also repaired the walls that had been damaged during the siege.Footnote 43 This is surely a reference to the new regime's programme of rebuilding the fort's northern walls.Footnote 44 Here they added a new gate, the Naurangi Darwaza, together with three bastions to the west of it, two of them round with projecting bracketed balconies, and one of them square with brackets only on the outer face. In the Naurangi Darwaza, they also built a large inner courtyard whose upper walls contain narrative sculptural panels depicting scenes from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Krishna cycle, and Vaishnava avataras, as well as court scenes from metropolitan Vijayanagara. In all, this gateway complex and the new bastions to its west register a clear and deliberate attempt to stamp a distinctively Vijayanagara aesthetic onto this frontier site, which had for so long been a Bahmani and Bijapuri possession.

Post-conflict Diplomacy

Following Krishna Raya's return to Vijayanagara and the round of festivities that celebrated the king's victories at Raichur, an ‘Adil Shahi ambassador arrived in the capital to negotiate a final settlement between the two adversaries. After keeping him waiting for a month, the king finally admitted the ambassador for a private audience. The latter conveyed an extraordinary request from Isma'il ‘Adil Khan, namely, that should Krishna Raya restore to Bijapur the city of Raichur, together with the artillery, tents, horses, and elephants that the ‘Adil Shahis had lost in the battle, Isma'il would remain the king's enduring and loyal friend.

In response, Krishna Raya agreed to grant all these requests—and even to return Bijapur's highest-ranking officer, Salabat Khan, who had been captured in the debacle by the Krishna riverFootnote 45—on the sole condition that Isma'il first come down to Vijayanagara and kiss his foot. When this response was conveyed to Isma'il, the latter replied through his ambassador that, whereas he was ‘of full mind joyfully to do that which the King wished’, it was unfortunately not possible for him legally to enter another king's sovereign territory. On hearing this, Krishna Raya offered to accommodate the sultan's concerns by meeting him at their common border near the fort of Mudgal. There the sultan could kiss the king's foot. Without waiting for the sultan's response, Krishna Raya proceeded north to Mudgal, accompanied by a formidable army that was doubtless intended to focus the sultan's mind. But Isma'il, who had no intention of journeying to Mudgal or of ever enduring the humiliation of kissing the king's foot, stalled and prevaricated while his messengers notified the king that he was on the way and would reach Mudgal very soon.

However, when it became clear that Isma'il was not going to present himself at the border, Krishna Raya opted for an alternative course of action, namely, of bringing his foot to the sultan, so that the latter could kiss it in his own domain without having to travel anywhere. The king and his army then entered ‘Adil Shahi territory, moving as far north as Isma'il's capital of Bijapur, which the sultan prudently vacated before the king's arrival. With Isma'il absent, Krishna Raya's men proceeded to damage several of the city's prominent houses, on the grounds that they needed firewood. When Isma'il, through envoys, protested this reckless behaviour, Krishna Raya replied that he had been unable to restrain his men from their destructive activities. Meanwhile the sultan, preferring to suffer the humiliation of his capital's desecration than to kiss Krishna Raya's foot, simply avoided his capital as long as the king was in the city. Eventually Krishna Raya, having made his point, returned to his own capital.

Two observations emerge from this discussion. First, Nunes's account of Krishna Raya's overbearing behaviour in the aftermath of the Raichur battle stands at odds with his image in modern scholarship, which tends to revere him as an ideal Indian monarch—heroic, virtuous, pious, and just. Modern scholars have even dignified him with the name ‘Krishna Deva Raya’, even though contemporary sources generally refer to him simply as Krishna Raya. One twentieth-century scholar rejects outright the possibility that, notwithstanding Nunes's testimony, a man as ‘noblehearted’ as Krishna Raya could have demanded that an adversary kiss his foot.Footnote 46 But we need to evaluate the man by accounts of his own day. One might expect that court poets or chroniclers, who had a professional investment in glorifying the court they served, would celebrate, not suppress, the episodes in which their royal patron crushed or humiliated their enemies. But unfortunately, no contemporary poetry concerning Krishna Raya's Raichur campaign survives.Footnote 47 The sole evidence in the matter comes from an outsider, Fernão Nunes, who had spent three years in metropolitan Vijayanagara not as an ambassador, but as a horse trader who would have been in touch with the court's commercial agents. As such, he would not seem to have had any motive either to celebrate or to criticize the king. Besides, balancing the chronicler's matter-of-fact account respecting Krishna Raya's foot are his several references to the king's generosity, such as the latter's generous treatment of Raichur's defeated townspeople. In the final analysis, Nunes's account of the episode respecting Krishna Raya's foot serves to humanize the man, and as such can perhaps provide a much-needed corrective to the king's idealized, cardboard cut-out image found in most textbooks.Footnote 48

Second, and far more serious, Krishna Raya's style of diplomacy in the wake of the Battle for Raichur arguably carried with it the seeds of his kingdom's demise. For the king, while waging his campaigns against Isma'il Adil Khan, had in his service a man who would subsequently display the same high-handed style of diplomacy, which in his case led to the destruction of metropolitan Vijayanagara. This was Rama Raya, an officer who had taken up service with Krishna Raya five years before the Battle for Raichur. The king was so impressed with the officer's abilities that he gave him his own daughter in marriage. After his patron's death in 1529, Rama Raya steadily rose in power, by 1542 becoming Vijayanagara's supreme autocrat, ruling the state through a nephew of Krishna Raya whom he had reduced to a mere puppet sovereign.

For several decades, Rama Raya cynically intervened in conflicts among the northern sultanates. But his manipulative and haughty behaviour finally induced those same sultanates, in 1565, to combine forces and crush him and his army at the Battle of Talikota. The immediate cause of that battle lay in an act that, in its brazen audacity, echoed that of Krishna Raya and his foot. In late 1561, Rama Raya demanded that if his current adversary, Sultan Husain Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar, were to enjoy lasting peace with Vijayanagara, he must first come and eat pan (betel nut) from the autocrat's hand. Unlike Isma'il ‘Adil Khan, who simply vacated his capital to avoid kissing Krishna Raya's foot, Sultan Husain succumbed to Rama Raya's humiliating demand. Determined to avenge this act, Husain took the lead in organizing a coalition of northern sultanates to wage the campaign in which Rama Raya was killed, his army destroyed, and metropolitan Vijayanagara demolished. Whereas no direct evidence proves the point, one suspects that Rama Raya's tactic of humbling his northern adversaries was something he could have learned by observing the overbearing diplomacy of his own father-in-law, Krishna Raya.

Conclusion

The Battle for Raichur originated in a dispute between Vijayanagara and Bijapur over money intended for purchasing warhorses. It then saw the first notable instance of field and siege artillery used in the Indian interior. It effectively ended when the governor of Raichur was shot by a matchlock most likely made in Goa. In several respects, then, the 1520 battle represents a transitional phase in the military history of South Asia. It also played an important role in the diplomatic history of the Deccan.

From a military standpoint, the battle presents what might appear a paradox, namely, that the side that relied the more extensively on firearms not only lost, but lost decisively. In April 1526, just six years after the contest between Isma'il ‘Adil Khan and Krishna Raya at Raichur, one of the most famous battles of Indian history was fought at Panipat, more than a thousand miles north of the Raichur Doab. In that battle, the Central Asian Turkish prince Babur deployed field cannon in defeating the last ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, which led directly to the establishment of the Mughal Empire. Given the significance of the battle's outcome, and the fact that the winning side used cannon, Panipat is sometimes seen as having inaugurated India's ‘Gunpowder Age’.

On the other hand, states usually assimilate new technologies by a gradual process of trial-and-error, in respect to which failures can be as important as successes. It seems certain that a principal cause of Isma'il's crushing defeat by the banks of the Krishna river lay in his gunners' inability to quickly reload and fire successive rounds of shot before being overwhelmed by Vijayanagara's swift and powerful cavalry. Much had to be learned about the manufacture and deployment of field cannon, and considerable practice would be necessary, before this new technology could become truly lethal to opponents who had mastered the tactics and techniques of cavalry warfare. From this point of view, Isma'il ‘Adil Khan's defeat represented a crucial and necessary step towards the full integration of field cannon into South Asian military traditions that theretofore had been dominated by the use of heavy cavalry. In the military history of India, then, the Battle for Raichur may be justly placed alongside Babur's far better known victory at Panipat, rather than omitted altogether.

If Isma'il was the first commander to use cannon in an important Indian battlefield engagement, he was also among the first to mount cannon on the battlements of forts in the Indian interior. But here, too, the technology's very novelty proved its users' undoing, for in 1520 Raichur's system of fortification was very much in a transitional phase of development. Before the city fell to Vijayanagara's army, its defenders were in the process of adopting, however imperfectly, a new technology that would ultimately improve and diffuse throughout the whole of India. Nunes reports that on the city's battlements, several hundred heavy and light cannon were positioned alongside thirty stone-hurling catapults, a device that had been used in Deccani siege warfare for several centuries before this engagement. However, owing to the arrangement of the fort's defences—with the catapults on the bastions and the cannons rigidly fixed in immobile positions between the merlons—Krishna Raya's men were able to dismantle a portion of the city's walls without suffering prohibitively high casualty rates. In effect, ‘Adil Shahi engineers at Raichur deployed the new gunpowder technology in a manner that proved just as disastrous there as did Isma'il's deployment of field cannon by the Krishna river. Given his victories both by the river and at the fort, Krishna Raya could hardly be faulted for not seeing cannon warfare as the wave of the future.Footnote 49

On the other hand, the Vijayanagara king was clearly impressed by the matchlocks used by Cristovão de Figueiredo and his fellow Portuguese mercenaries at Raichur. These men had in all likelihood been armed by the Goa arsenal, which was then producing ‘Indo-Portuguese’ weapons that appear to have been superior to anything then available in India. As Nunes noted, no Muslims at Raichur had ever been killed by such firearms until Krishna Raya's siege of the city. It was thus in the area of matchlock weapons, and not in that of field or fixed cannon, that new gunpowder technology contributed to the outcome of the Battle for Raichur.

The battle was also the first major conflict in the Indian interior in which European mercenaries are known to have participated. We know that European mercenaries and renegades had begun appearing in the service of Indian coastal powers as early as 1502, and that European gunpowder technology diffused into the Indian interior together with European matchlockmen, bombardiers, and cannon founders who sold their services to indigenous states in the interior.Footnote 50 But, as Maria Augusta Lima Cruz notes, in European accounts only those who served armies under Muslim control were understood as renegades.Footnote 51 Thus Cristovão de Figueiredo, otherwise a horse merchant, is described by Nunes as a proud Portuguese fidalgo who boasts to Krishna Raya that ‘the whole business of the Portuguese was war’ and that the greatest favour the king could grant would be to allow him to accompany the Vijayanagara army to Raichur.Footnote 52 Nunes never refers to de Figueiredo and his twenty fellow matchlockmen as renegades (arrenegados). He does use that term, however, in mentioning the fifty Portuguese who fought and died for Isma'il ‘Adil Khan at the battle by the Krishna river.Footnote 53

Finally, we must consider the battle's legacy in defining the Doab generally, and more particularly the city of Raichur, as a frontier zone. The city remained under Vijayanagara's control for only ten years, until 1530 when Isma'il ‘Adil Khan re-conquered the fort following Krishna Raya's death. But during the decade 1520–30, Vijayanagara's governors, architects, and engineers reshaped the city's physical appearance in ways that emphatically asserted the aesthetic vision of its new rulers. From epigraphic evidence we know that in July 1521, about a year after the city's transfer to Vijayanagara's authority, a patron named Kanthamaraju Singaraju dedicated a new temple in the city.Footnote 54 Unfortunately, that structure is not identifiable now. Very much visible today, however, are the structural additions or modifications that Vijayanagara's rulers made to the city's outer walls and gates, and it is in these features that one sees the victors' distinctive imprint. On the fort's northern side, especially, the exterior courses of several bastions are covered with sculptural reliefs bearing motifs identical to those of early sixteenth century metropolitan Vijayanagara. The most spectacular display of those motifs is found in the spacious courtyard that was built into the city's new, northern gateway complex, the Naurangi Darwaza, which combines large and small sculptural reliefs drawn directly from the tradition of metropolitan Vijayanagara.

However, because Vijayanagara's authorities in Raichur restricted their structural modifications to just several segments of an otherwise Bahmani (and ‘Adil Shahi) fort, the overall result is a site in which two very different architectural and aesthetic traditions, the Bahmani and the Vijayanagara, are abruptly juxtaposed, one beside the other. It is, finally, this juxtaposition—a consequence of the 1520 battle—that most tellingly conveys the sense of a city teetering on the edge of two aesthetic worlds.

Acknowledgements

This essay is dedicated to the memory of two good friends and colleagues. One is my teacher, John F. Richards, who passed away on 23 August, 2007. I count myself especially honoured to have been among John's students, and to have benefited from his expertise, his compassionate nurturing, and his high standards of scholarship.

The essay is also dedicated to the memory of Dr. Balasubramanya, with whom Phillip B. Wagoner and I had the good fortune to spend several memorable days at Hampi in June 2005, just four months before his untimely death robbed Karnataka archaeology of yet another of its brightest luminaries. Professor Wagoner and I are grateful to the Getty Foundation for a Collaborative Research Grant awarded for the period 2004–2006, which enabled us to carry out two seasons of exploratory field surveys in India. I also wish to thank Lois Kain for preparing the map of the Deccan plateau that accompanies this essay.