Intervals are really musical ideas

That Igor Stravinsky would eventually be attracted to serialism is not surprising, given his conviction about the role of intervals in generating musical ideas. Reacting to those who criticised his adoption of the twelve-tone technique, Stravinsky once commented to Milton Babbitt, ‘There’s nothing to it; I’ve always composed with intervals.’ Babbitt later referred to this quote as ‘something of a witticism, but what it did show, much more than a witticism, was how profoundly this is an interval kind of sequence and not just a pitch-class syntax – fundamentally and centrally an interval syntax’ (Reference Babbitt, Dembski and StrausBabbitt 1987b: 20, 188 n. 12).

Stravinsky’s intrigue with intervallic patterns is significant in some of his earlier works – particularly in the treatment of the motivic networks that he established to support the narrative in passages of Firebird (1910) and Perséphone (1934). As I have written previously in Multiple Masks (Reference CarrCarr 2002), the abbreviated symmetrical form of the immortality motive from Perséphone is 4–9 [0167] in the Allen Forte pitch-class set taxonomy (its longer five-note form becomes 5–7 [01267]). By creating a symmetry among statements of the immortality motive in which the exact order of intervals is retained while producing twelve different pitch classes, Stravinsky may have unknowingly been anticipating his own serial technique in later years. He was also working – consciously or unconsciously – with a motivic technique similar to that which he previously established in the ‘Carillon’ section of Firebird, whose motive, 6–7 [012678], contains Perséphone’s immortality motive (both the five- and four-note versions) as a subset.

Cantata (1952) and Septet (1952–3)

In order to set the stage for a discussion of Stravinsky’s compositional process for In memoriam Dylan Thomas, his first composition to utilise serial technique exclusively, it is useful to establish the context for his choice of the text, and the influence or assistance of Robert Craft on Stravinsky’s path to serialism (Reference CraftCraft 1992: 33–51). It was on 8 March 1952 during a motor trip to Palmdale with Craft himself and Stravinsky’s second wife, Vera, that Stravinsky said ‘that he was afraid he could no longer compose and did not know what to do. For a moment he broke down and actually wept’ (Reference CraftCraft 1992: 38–9). Then, Stravinsky mentioned that the Schoenberg Suite op. 29 that he had observed a few weeks prior in rehearsal and performance made a ‘powerful impression’ on him. Webern’s Quartet op. 22 also happened to be on the programme. On hearing Stravinsky’s desire ‘to learn more’, Craft suggested that Stravinsky should re-orchestrate the String Quartet (referring to Concertino (1920)). Following this advice, Stravinsky completed the re-orchestration in 1952 as Concertino for 12 Instruments (Reference CraftCraft 1992: 39), which would be premiered on 11 November 1952 with Stravinsky conducting the Los Angeles Chamber Symphony Orchestra. This programme also included the premiere of Cantata (1951–2), significant because the compositional techniques used in Cantata predicted those of In memoriam Dylan Thomas.

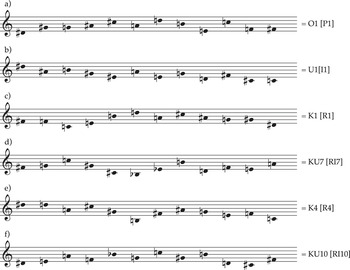

In Figure 11.1, notice one of Stravinsky’s initial flirtations with serial procedures: overlapping entrances of the six-note prime (or basic) set and its variants (retrograde, inversion, and retrograde inversion) (cf. Reference MasonMason 1962). This forms the basis of what I will refer to as Stravinsky’s use of ‘serial variants’, as demonstrated on a sketch page (seen in Figure 11.2), labelled ‘cancricans’ [sic] (unless otherwise noted, all sketches discussed in this chapter, are housed in the Stravinsky Collection at the Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel, for whose permission to reproduce them we are grateful). This technique is predictive of one discussed later found in In memoriam Dylan Thomas and can also be seen in Three Songs from William Shakespeare, for mezzo soprano, flute, clarinet, and viola, premiered on 8 March 1954 at the Monday Evening Concerts in Los Angeles, conducted by Craft.

Figure 11.1 Cantata, ‘Ricercar II’, overlapping sets

Figure 11.2 Cantata, sketch page showing serial variants

Some insights by Lawrence Morton about Cantata provide a reminder of the intricacies of Stravinsky’s use of the models of Bach as a basis for his own canonic structure of ‘Ricercar II’:

The whole thematic material, an eleven-note phrase is first made familiar by the tenor in four versions: direct, inverted, in cancrizans (backward), and retrograde inversion (backward and upside down). Then the four versions are presented in various combinations by the voice and the oboes. Separating the canons is a ritornello.

Tovey once pointed out that in formal Baroque polyphony (canons and fugues as typified by the work of Bach) the contrapuntal combinations will work automatically if they will work at all. This is not true of Stravinsky’s canons. He constantly alters the time values of the notes of his theme; he displaces individual notes by an octave, he employs such devices as augmentation and diminution simultaneously within a single voice in a single statement of his theme. Not one of his combinations works automatically; each is a fresh invention, each poses a new problem and earns a new solution. In this sense, his canons are truly marvelous in their ingenuity, whereas ingenuity is the one quality that cannot be attributed to classical Baroque polyphony.

Morton also points out the structural delineations of the choral Prelude, Interlude, and Postlude in Cantata, all of which are strophic settings of the traditional ‘Lyke-Wake Dirge’, which describes the stations of the soul as it travels to purgatory. Little did Stravinsky or Morton know that the format for Cantata would resurface in his memorial for Dylan Thomas.

Septet (1952–3)

The ‘unity’ that prevails in Septet represents a continuation of Stravinsky’s approach to Cantata that is part of a new beginning of his compositional process. With this work, Stravinsky adopted Schoenberg’s idea of serialism on his own terms – Stravinsky did not make all notes equal in his adaptation of serialism as Schoenberg had done. In Paul Hume’s review of the premiere performance of Septet in the music room of Dumbarton Oaks (conducted by Stravinsky) on 24 January 1954, he refers to the ‘central germinal idea of the opening movement’ as generating the entire score (Reference HumeHume 1954). Stravinsky used baroque forms in Septet just as he had in Octet (1919–23), which was also included on the 1954 programme together with Histoire du soldat (1918). A manuscript page of the initial row table, used as the basis of Septet, was reproduced in Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents (Reference Stravinsky and CraftStravinsky and Craft 1978: plate 14). Serialism may have been so appealing to him because it enabled him to unify his melodic and harmonic ideas, just as he had endeavoured to do in Firebird.

In memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954)

When Stravinsky collaborated with literary figures, his musical settings often reflected the poetic form of the text as it did with André Gide’s for Perséphone. At other times, Stravinsky would take liberties with poetic metre of the libretti, such as Jean Cocteau’s for Oedipus Rex (1926–7) or W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman’s for The Rake’s Progress (1947–51) and one by Auden discussed later in this chapter, Elegy for J.F.K. (1964).

Another phase of Stravinsky’s approach to text setting would be in, as Robert Hatten described it, ‘his close musical approximations of both prosody and poetic form in his setting of Dylan Thomas’s villanelle, “Do not go gentle [into that good night]”, a poem that exists for its own music rather than as something written with musical setting in mind’ (personal correspondence, 24 May 2018). Craft recounts that Stravinsky began his setting of that villanelle in early March of the year following Thomas’s death. Stravinsky then completed the surrounding prelude and postlude later in March and in June, respectively. Perhaps he had meant to set the text as the entire piece, but then when he had scheduled the first performance for the new Monday Evening Concert series, Craft informed him that Heinrich Schütz’s Fili mi Absalom (for bass voice and four trombones) would also be on the programme. Likely inspired by the Schütz piece, Stravinsky then added the Dirge-canons for string quartet and trombones (Reference CraftCraft 1992: 58), and it is possible that the fact that Schütz studied with Giovanni Gabrieli may account for the antiphony between the trombones and string quartet that shows up during Stravinsky’s Dirge-canons. This is also strongly suggested by the opening rhythmic motive being the opening motive used in canzona (long – short – short), such as the one found in Canzona septimi toni for eight parts by Gabrieli from the collection Sacrae Symphoniae.

In total, there are eight pages of sketches for In memoriam, one of which contains a fragment that may have been Stravinsky’s earliest musical sketch for the work (cf. Reference CraftCraft 1992: 59). Looking at the top right corner of Figure 11.3, it is interesting to compare how Stravinsky chose the retrograde written in his own hand on the second line of the sketch before going to the top line for the pitches of ‘meteors’. These are specific pitches that Stravinsky would use in the published version for this line. Stravinsky labels these five notes as the theme. In the final published outcome, Stravinsky adds two pitches (B♭ to B) to the opening line of the text, therefore creating an overlap between two serial forms (I and R) of the theme.

Figure 11.3 In memoriam Dylan Thomas, diplomatic transcription of sketch page

The most fascinating aspect of these sketches is the evidence they provide for how Stravinsky was inspired by four-note patterns and used layering techniques to assemble cadential blocks from these patterns. As he was layering the serial variants, he introduced octave displacement and intervallic inversion for dramatic purposes, namely, by inverting an anticipated ascending minor second to a descending major seventh, and by displacing an ascending minor second to an ascending minor ninth. This compositional technique enabled Stravinsky to enhance the musical meaning of words, such as ‘dying of the light’ (D – ↑ D♭ – C – E♭ – E).

Another notable technique using the five-note series and its variants is the manner in which Stravinsky treated the intervals – a minor third, surrounded by two minor seconds that encompass a major third. He uses these intervals as an opportunity for further painting the text and typically has one of the two minor seconds change direction to produce a descending ‘sigh’ figure.

Canticum Sacrum ad honorem Sancti Marci nominis (1955) and Threni (1957–8)

Both premiered at successive Venice Biennale Festivals starting in 1956, Canticum and Threni share the distinction of being the first works in Stravinsky’s serial period to use biblical texts in Latin.

Stravinsky created a musical symmetry in Canticum that reflects the architectural design of Venice’s Basilica of Saint Mark, as well as a compositional process that juxtaposed that which was familiar to Stravinsky – eighteenth-century contrapuntal textures – with that which was still new to him – twentieth-century serial techniques. In fact, Canticum was the first of his works to contain a movement based entirely on a tone row. However, diatonic passages nevertheless remain present, as does evidence of the influence of Gregorian chant.

The setting of ‘Caritas’ in the third movement (bb. 116–29) serves as a microcosm of Stravinsky’s genius in combining contrapuntal models and dodecaphonic serial techniques. By using various forms of a twelve-tone row with the original (prime) form announced by the tenor on C♯ in b. 116, answered in the next bar by the trombone (prime, in augmentation) a semitone lower on C, the alto in the next bar on D (inversion), and two bars later, expanding even further upwards by semitone in the soprano line on D♯ (prime).

According to Craft, the idea of separating the entries of canonic voices by a semitone in this canon was likely influenced by a similar practice of separating canonic subjects in Webern’s Variations op. 30 (Reference CraftCraft 1956). Webern, however, initially limited these entrances by semitone to only two voices (opening measures: A, B♭, D♭, C and B♭, B♮, D, C♯), whereas Stravinsky adds not only a third but even a fourth, designing multiple entrances circling around C♯ (first down to C, then up to D, then further up to D♯). One has only to look at a transcription of a short musical sketch – possibly in Stravinsky’s hand – catalogued at the PSS. This sketch was acquired by the PSS from the Craft collection, and it was found with the orchestral score of the aforementioned Webern Variations. This suggests that Stravinsky studied the Webern score closely enough to jot down the serial variants. In fact, Craft writes that when Stravinsky was in Baden-Baden and ‘a recording of Webern’s orchestra Variations was played for him, he asked to hear it three times in succession and showed more enthusiasm than I had ever seen from him about any contemporary music’ (Reference CraftCraft 1992: 38).

What is even more remarkable is that the intervallic structure of the previously mentioned four-note motive in Webern’s Variations (A, B♭, D♭, C) coincides with the intervals produced by four of the five notes in the inversion of the theme in Stravinsky’s own analysis of In memoriam, which also resurfaces here in Canticum, as well as in Agon, and is pitch-specific with the Webern motive, then transposed up a semitone to B♭. Later in op. 30, Webern wrote several statements of this four-note motive on different pitches, starting in the Coda at b. 146, and it appears that Stravinsky circled some of these statements in his copy of the orchestral score.

Christina Thoresby, in her review of Canticum, wrote that Stravinsky was overheard telling a reporter after the premiere about the importance of mathematics in relation to the piece. Thoresby also noted that ‘after hearing it repeatedly at rehearsal and in performance it seemed to one listener to blend marvelously with the mathematics and metaphysics of the great Basilica’ (Reference ThoresbyThoresby 1956). Craft seems to all but confirm the influence of Webern in ‘A Concert for Saint Mark’ for The Score in December 1956, particularly in relation to ‘the structure of a canon such as the one in “Caritas” which ends like the last movement of Webern’s Opus 31, and which resembles a canon in the Webern Variations for Orchestra in that each entrance is at the semitone’ (Reference CraftCraft 1956).

Stravinsky also transcribed Bach’s organ work Canonic Variations on ‘Vom Himmel hoch da komm’ ich her’ (1956) for chorus and orchestra during this time. The performance forces are almost identical to those for Canticum, as it was conceived as a companion piece for the concert in which Canticum was premiered. The accompanying instrumental canons are of far greater interest than the choral element in this work, as the voices merely sing the unharmonised chorale melody.

Agon (1953–7)

A microcosm of Stravinsky’s metamorphosis from neoclassicism to serialism, Agon was begun in December 1953, but its composition was interrupted by both In memoriam and Canticum before it was eventually completed on 27 April 1957. Owing to the duality of Stravinsky’s compositional techniques at play in Agon, it remains the clearest lens through which to see his serial method develop. Roman Vlad highlights Stravinsky’s repeated use of the same six-note series from the second dance, ‘Double Pas-de-Quatre’ (for eight female dancers, approx. bb. 81–95) (Reference VladVlad 1978: 200). Stravinsky uses the hexachord in three successive transformations, each at different pitch levels, but all based on the same intervallic patterns, and all of which utilise the set 6z44 [012569]: the flutes in b. 81, the violin in b. 84 (inverted), and the flutes in b. 93 (retrograde inversion). Disregarding the actual appearance order of the intervals in the hexachord, these three statements are an excellent example of Stravinsky’s serial treatment of a hexachordal motive in the context of a neoclassical ballet. Following Vlad’s observations, the principal motives continue in the following section (‘Triple Pas-de-Quatre’, bb. 96–121) and are ‘presented mostly in their mirror’. Allen Forte continued to analyse Stravinsky’s explorations with serial transformations in the later sections as well, particularly ‘Bransle Simple’ (bb. 278–309) and ‘Bransle Gay’ (bb. 310–35).

Of special interest is the way that Stravinsky interchanges the minor ninth interval with its inversion in a short section (bb. 452–62) of the ‘Pas-de-Deux’ (complete from bb. 411–519). It is here that Stravinsky created a series involving twelve different pitches that he introduced through the sequential repetition of a given tetrachord. In addition, he created an imitative texture that enabled him to use one of his favourite baroque models as structural inspiration for his serial experimentation in Agon. Even more remarkable is the strong relationship that the intervallic design of the fugal subject has with the inverted thematic motive of In memoriam, completed during Agon’s fractured compositional period.

Threni: id est lamentationes Jeremiae prophetae (1957–8)

For this work, Stravinsky was inspired by Ernst Krenek’s setting of Lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae [Lamentations of the Prophet Jeremiah], written in the early 1940s, but not published until much later in 1957:

For both composers their settings of the biblical Lamentations represents an important landmark in the development of their serial procedures. For Krenek it was his development of the technique of transposition-rotation which he used compositionally in Lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae. For Stravinsky it was that Threni was his first completely twelve-note work and one in which he began to explore some of the serial procedures that were to become hallmarks of his compositions from Threni on – the precedent for some of which can be found in the works of Krenek, Lamentatio being the first and most significant.

Among the documents at the Stravinsky archive for this work, there is one page in Stravinsky’s hand that provides four forms of one twelve-tone series. In addition, there are sixty-six pages of sketches – some of which will be discussed below in relation to Stravinsky’s compositional process – and other examples that appear elsewhere in research published by David H. Smyth and Joseph N. Straus (Reference SmythSmyth 2000; Reference StrausStraus 2001 and Reference Adorno1999b).

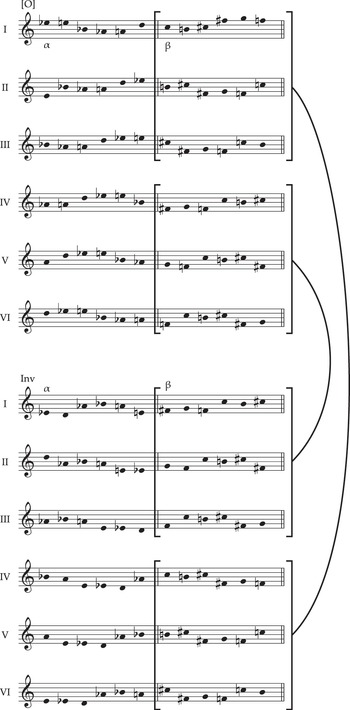

In an article published in Melos, Vlad presented three of the four basic initial row forms, plus three transpositions (see Figure 11.4) (Reference VladVlad 1959: 36). For clarity, his original abbreviations appear (O, U, K, KU) along with their equivalents (P, I, R, RI, respectively). Stravinsky labels his integers using 1–12, instead of the more traditional 0–11, in both his initial row table and also when he is annotating specific passages in his musical sketches. Krenek and Vlad also used this approach, so consequently, this discussion of Threni will use the same 1–12 numbering system.

Figure 11.4 Vlad’s chart of various forms of Threni row

Vlad was invited to write the programme notes for the premiere, and both those and his later observations add a special dimension to the context of Stravinsky’s compositional process for Threni. For example, Vlad recounts that because two forms of the row (both a prime and inversion) appear simultaneously at the start of the piece, he asked Stravinsky which form constituted the original (or prime):

Stravinsky explained to me later that the first thematic idea for the entire work … consisted of the phrase (bars 6–18) in which the soprano soloist announces the beginning of the Lamentations of the Prophet Jeremiah. … This explanation on the part of Stravinsky is important, in my opinion, not so much in regard to the identification of the series (in fact Stravinsky suggested that I should stress the mutual relationship between the various basic forms of the serial cluster rather than which came first) as indicating the spontaneity and the thematic concreteness of the musical idea on which the work is built up.

Figure 11.5 illustrates the two simultaneous forms of the row and the so-called ‘original’ in bb. 6–18, with row labels corresponding to Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.5 Threni condensed orchestral score, bb.

One of the most fascinating examples of Stravinsky’s simultaneous statements of the row begins in b. 6 where P1 is stated contrapuntally with I1, with surrounding statements of R1 in the first oboe and RI7 (a tritone away) in the trombones, thus enabling R1 and RI7 to both start on F♯. By sharing the full statement of RI7 among three trombones, Stravinsky achieves a pointillistic texture that is both reminiscent of baroque texture and lightly treading towards Klangfarbenmelodie. This is also the case with the last three notes of RI when they move from the first oboe to the clarinets (bb. 14–15, sounding G, G♯, D♯) and in the English horn (bb. 17–18, the last three notes of R4, sounding E, F, C). These three-note cadential patterns help to unify the conclusion of this introductory section that ends in b. 18.

The technique also prefigures Stravinsky’s reordering of rows by the displacement of three-note patterns from the end to the beginning so that the order of pitches reads 10–12 followed by 1–9. This can be seen in the unbarred four-part vocal canon in b. 189 and is also noted in red pencil by Stravinsky on the corresponding sketch page for this section. Also found there is a rhythmic discrepancy – he doubles the durations from crotchets in the sketch to minims in the published score. Perhaps this was to make this unmetered section appear closer to the centuries-old settings of Latin masses, and also to emphasise the syllabic rhythm of the Latin text ‘Re/cor/da/re pau/per/ta/tis [remember poverty]’ (slashes indicate syllables).

Stravinsky also provides a helpful guide for the analysis of this phrase by writing ‘RI’ in a box next to the Bass I entrance. Above that on the sketch page, Stravinsky writes the canonic imitation of Bass I for Tenor I (RI11). For the remaining voices of the canon in the published score, Stravinsky then uses RI10 starting in the original order of 1–3 (D♯, E, A) for Basso II and imitated in Tenor II in the same original order (B♭, B, E). The interesting phenomenon is that the intervals of this (0,1,6) trichord are prominent throughout the various forms or variants of the row for Threni and resounds as the main musical idea for this work (Reference VladVlad 1978: 212).

Clare Hogan concludes:

In many ways Threni can be viewed as an exploration of what were, and continued to develop as, characteristically Stravinskian serial techniques. The overall formal structure is basically determined by the text within which Stravinsky’s serialism operates. As is true of some of the movements of Canticum Sacrum and Agon, purely musical points of reference are often created by the predominance of the prime forms of the series, and the transpositions throughout the work are frequently limited for the purpose of exploiting similarities between rows and row-segments.

In the 30 September 1958 European (Rome) edition of the of The New York Herald Tribune, Peter Dragadze wrote:

‘Threni’ is a vast work lasting some 35 minutes, in which Stravinsky without any hesitation completely abandoned himself to a pure serial dodecaphonic technique of composition familiar to us through the Webern and Schoenberg schools, but bound together with that infallible ‘scientific’ genius which has allowed Stravinsky, and only Stravinsky, to produce in 1958 a musical conception already considered démodé by leading contemporary musicians.

Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–9)

In a letter of 8 May 1958 addressed to Paul Fromm (of the Paul Fromm Music Foundation in Chicago), Robert Craft wrote:

Mr. Stravinsky went out to Krenek’s for dinner the other day and I am happy to say that those two composers now get on very well. Stravinsky is really very fond of Krenek, respects him enormously, and is really glad to learn the kind of things that everybody can learn from Krenek. Krenek also couldn’t have been nicer.

While it is true that this meeting with Krenek coincides with the time that Stravinsky was working on Movements, it cannot be assumed that this was on the agenda during their meeting, though one sketch page contains an annotation in handwriting that seems to not be that of Stravinsky.

In December of that same year – when Stravinsky was in New York to conduct the city’s premiere of Threni – Stravinsky spoke with great enthusiasm to Milton Babbitt and Claudio Spies about his compositional process for Movements and showed them ‘all of his notes, alphanumerical as well as musical, pertaining to the Movements … and proceeded, as if to restore for himself and convey to us his original, unsullied (by actual, approximate performance) image of his creation, a creation that clearly meant crucially much to him’ (Reference Babbitt, Haimo and JohnsonBabbitt 1987a: 16).

The materials that Stravinsky showed to Babbitt and Spies during this meeting in New York are almost definitely among the numerous manuscripts and other documents at the Stravinsky Archive. Included in that collection are two pages of row tables, and fifty-four pages of sketches in Stravinsky’s hand, making it possible to observe Stravinsky’s early (if not earliest) examples of constructing rotational arrays based on hexachords created for Movements. Exactly where Stravinsky’s compositional process began for this work is difficult to say, though from some of his musical sketches, it is likely that he was thinking of a network of motivic ideas based on a series of intervals that provided him with the most possibilities, particularly those that included tritones.

The opening two bars of Movements are based on two hexachords at the top of the table, shown in Figure 11.6. Stravinsky disperses the pitches of the first hexachord among various instruments simultaneously – flute, trumpet, violins, and piano – whereas the pitches of the second hexachord are confined to the piano. The instrumentation of the first hexachord is suggestive of the artistic technique of pointillism (see Reference CarrCarr 2014: 144–5). The succession of intervals and pitches of hexachord Oβ is the same as those of the inversion at β (I3). Hexachords Oα and Oβ share the same three tritones and would be categorised as 6–7: [012678]. More fascinating is the outcome of Stravinsky’s application of hexachordal rotation to Oβ (hexachord 6–7, see Figure 11.7) that yields pitch specific replications under inversion (in different sequence) – evidence of the symmetry of the original intervallic profile of hexachord 6–7.

Figure 11.6 Movements, original (prime) row, split into hexachords α and β

Figure 11.7 Movements, diplomatic transcription of sketch page, annotated with rotation of hexachord 6–7

Stravinsky has left several musical sketches that help to explain his compositional process for Movements – one among them that shows Stravinsky’s experimentation with various transpositions of hexachord β – primarily in inversion of V that is labelled by Stravinsky as ‘Riv V’. He also uses other forms of this series, as he formulates his ideas for the section beginning at b. 27. It is possible to observe how he used compound intervals to enable pitches of a given motive to move between different instruments. Rather, it seems possible that Stravinsky was inspired by Webern, not only through an apparent close study of Webern’s transcription of the ‘Ricercar’ of Bach’s Musical Offering among Stravinsky’s notations at the Stravinsky archive, but also through his close association with Robert Craft.

In the sketch titled the ‘1st Interlude’ – the title did not carry over into the published score, though the music does as bb. 43–5 – Stravinsky indicated two hexachords: one of them the Retrograde of Oβ (Riv. β on the sketch) and the other the Retrograde of the Inversion of Oα (Riv. Inv–α on the sketch), transposed down a minor third and reordered. Both the handwriting and authorship thereof are unclear; they may, in fact, be Krenek’s annotations on Stravinsky’s music.

Stravinsky’s next level of sketching for this ‘interlude’ adds barlines (though these are also changed in the published score) and instrumentation. Stravinsky’s handwritten numbers from the previous sketch mentioned above also remain. The outcome at the foreground level is linear, which could justify Stravinsky’s poetic licence to change the order of pitches in the hexachord – in fact, Massimiliano Locanto, in his analysis of this same sketch, justified the reordering of pitches on the basis of the vertical function of the intervals (ic5) (Reference LocantoLocanto 2009: 242). Stravinsky eventually returns to one of his traditional techniques – block form – in what is initially called ‘4th Interlude’ (bb. 137–40 in the published score). Whereas he freely moved the hexachords between instruments in the ‘1st Interlude’ in a Webern-esque fashion, he now restricts melodic hexachord statements to individual instruments.

Movements represents a turning point in Stravinsky’s serial compositional process. In a review of the world premiere in the New York Herald Tribune (11 January 1960), conducted by Stravinsky at Town Hall in New York City, Jay S. Harrison wrote:

Igor Stravinsky, in his Movements for Piano and Orchestra has reached a point of no return … The work … is the most radical of his career, and is by implication, one of the most extreme therefore in the whole history of music. It pursues the course undertaken by the composer upon his acceptance of the 12-tone technique, with the significant difference that in his latest piece, he has by-passed all of his predecessors much as he did many years ago with the first performance of Le Sacre du Printemps.

A Sermon, a Narrative, and a Prayer (1960–1)

Whereas Threni was written using Latin texts from the Old Testament, the first two of the three movements of Sermon are from the New Testament and now in English: (1) a sermon from the epistles of St Paul; (2) the stoning of St Stephen (from the Acts of the Apostles); (3) a setting of poetry by Thomas Dekker. Given the uncertainties that occur in human life throughout history, particularly in times of war, disaster, and plague, the belief that humanity is saved by faith and hope becomes a source of consolation. Though it uses the Christian Bible as a lens, the spirit of universality is reflected throughout the piece.

In his article ‘Stravinsky’s New Work’, written in anticipation of the premiere of the work in Basel, with Paul Sacher conducting on 23 February 1962, Colin Mason put the piece in perspective with Stravinsky’s other works as follows:

Conforming to the pattern of Stravinsky’s works in recent years, it is musically (and serially) easier to come to grips with than his most recent instrumental work, Movements. All four forms of the basic 12-note series are used thematically throughout, and the vocal writing is in the euphonious contrapuntal style of the canons in Threni.

The design of the twelve-note series for A Sermon is highly intervallic in nature, and one is immediately struck by Stravinsky’s abiding interest in the ordering of these intervals – in this case, the opening instrumental prelude (bb. 1–11) foreshadows the poetic meaning of the text that appears in the next section. Following the analytical insights of Colin Mason, the annotations on the score of this prelude indicate two statements of the twelve-note series by the bass flute, a segment of the row in retrograde inversion and then a statement of the retrograde by the bass clarinet. Looking further at the series apart from the score, there is evidence that Stravinsky reordered intervals to echo the intervallic patterns that he used elsewhere when he was negotiating similar patterns from In memoriam Dylan Thomas (Reference MasonMason 1961: 6). Other possibilities are that the influence of the motives in Webern’s Variations op. 30 and Agon were still reverberating in Stravinsky’s musical imagination.

In his book Stravinsky, Roman Vlad reminds us of comments that Stravinsky made in conversation with Craft, having to do with the connection between chromaticism and pathos. About this, Vlad writes, ‘The quality of pathos in the cantata is that of a work in which the ultimate experience of human life is distilled’ (Reference VladVlad 1978: 231).

Variations: Aldous Huxley in memoriam (1963–4)

Containing just 141 bars of music, Stravinsky’s Variations for orchestra lasts slightly over five minutes, yet contains a web of complex serial techniques. Without question, while endeavouring to incorporate his own voice into his compositional process for Variations, Stravinsky benefited from his associations with Krenek, Babbitt, and Spies, while downplaying the work of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern.

Stravinsky’s approach to serialism in Variations strays from formulaic construction, incorporating short musical blocks that expand, following traditional variation technique. In at least one case, he even follows the model of a Bach fugue. Among his many manuscript pages for this piece, several larger ones are meticulously constructed and also heavily annotated in order to identify the occurrence of each row segment. It is not, however, readily apparent who wrote in the annotations to label the occurrences of the row forms in multiple colours in order to track the serial construction.

An exemplary point of baroque and twelve-tone juxtaposition involves his labelling of ‘fugato’ found on the manuscript page corresponding with b. 101. This is immediately preceded by a vertical hexachord distributed in the low strings, bassoons, trombones, and horns in bb. 99–100. Merely looking at these few bars, and indeed, virtually any part of the score, it appears that Stravinsky’s penchant for block form – hearkening back to the Rite of Spring – continues to play out in Variations, just as it will in his Introitus: T.S. Eliot in memoriam (1965).

Abraham and Isaac (1962–3) and Elegy for J.F.K. (1964)

Both of these works demonstrate Stravinsky’s penchant for versification and also happened to be programmed together at a performance on 6 December 1964 at Philharmonic Hall in New York City. The premiere of Abraham and Isaac, the text of which is in Hebrew, had been given six months prior (23 August) in Jerusalem, Israel, and Stravinsky’s preoccupation with syllabification was evident enough that even the review by Moshe Brilliant noted it, quoting Stravinsky as saying that he had ‘studied every syllable of the Hebrew text with the aid of scholars and composed the work accordingly’ and that ‘it could not be sung in any other language’ (Reference BrilliantBrilliant 1964).

Details of the collaboration for Elegy for J.F.K. can be examined in correspondence at the Paul Sacher Stiftung. With an explanation for the syllabic structure of his text, W. H. Auden wrote to Stravinsky and explained that he wrote the text in the poetic form of haiku, so that though the number of syllables in individual lines might vary, the total syllable count in each stanza would always remain at seventeen. It is debatable whether or not Auden’s specific use of haiku had an effect on Stravinsky’s compositional process for Elegy. His primitive ideas were written in a pocket-sized sketchbook that Craft said Stravinsky carried around in the last years of his life. It would appear that Stravinsky first set the last line of the first verse (‘The Heavens are silent’) to an oscillating two-note pattern that had occurred to him while on a flight from Los Angeles to Cleveland. He commented on this to a reporter from the New York Times, in an interview published on 6 December 1964, when asked about composing Elegy: ‘Melodic ideas came to me immediately, but the first phrase I was certain would never come unglued.’ Stravinsky considered those two oscillating notes as a ‘melodic-rhythmic stutter’. It is uncertain if he used scansion marks in his text analysis, as his setting of the text is, for the most part, straightforwardly syllabic.

Both works use serial techniques, though these are more pervasive in Abraham and Isaac. For this work, there exists a musical score partially annotated by Stravinsky himself, at the Paul Sacher Stiftung, demonstrating, for instance, his unique ordering of the notes for the hexachord in the first six measures, labelled 0β and starting on the second note of the hexachordal series instead of the first. He signed this score on 3 March 1963. A primitive sketch for these opening measures shows Stravinsky’s early ideas for the pitch material – before he had made final decisions on metric and rhythmic aspects of these patterns. His ideas about intervallic patterns were almost final, even at this stage. There are, too, row tables in Stravinsky’s hand that become the basis of his experiments with vertical constructs to establish the work’s harmonic language. The most curious aspect of one of these formulations occurs in a ‘block sketch’ on a sketch page that may very well be in handwriting that is not Stravinsky’s, as they are written in the duration of semibreves and, perhaps more telling, appear to be written in ink. Stravinsky tended to use filled-in noteheads during sketching and usually did so in pencil, not in ink. The paradigm in the sketch clearly anticipates the material in bb. 229–39. In fact, Stravinsky encircled six block harmonies implied by the verticals from the sketch on his copy of the piano reduction of the score that he notated in part.

Stravinsky’s musical experimentation with serialism in the Elegy is less complex in terms of serial techniques when compared with Abraham and Isaac, although Stravinsky was attentive to the syllabification of Auden’s poem in the form of a haiku. The following fragments in Figure 11.8 show a transcription of the musical sketch for the opening line ‘When a just man dies’ for the sake of comparison with the published version. The fact that Stravinsky originally wrote without barlines might seem unusual until a comment Stravinsky made in the New York Times interview, mentioned above (p. 199), published the day of the New York City performance (6 December 1964):

‘I wrote the entire vocal melody first, and only later discovered the relationships from which I was able to derive the complementary instrumental counterpoint. Schoenberg composed his Fantasy in the same way, incidentally, the violin part first, and then the piano.’ The reporter then asked Stravinsky, ‘Would you describe the music as “12-tone”?’ Stravinsky responded, ‘I wouldn’t though a series is employed. The label tells you nothing; we have no organon any more and card-carrying 12-toners are practically extinct. Originally, a series, or row (the horizontal emphasis of that word!) was a gravitational substitute and a consistently exploited basis of a composition, but now it is seldom more than a point of departure. A serial autopsy of the “Elegy” would hardly be worth the undertaking, in any case, and the only light that I can throw on the question of method is to say that I had already joined the various melodic fragments before finding the possibilities of serial combination inherent in them which is why the vocal part could begin with the inverted order and the clarinet with the reverse order – that is, because the series had been discovered elsewhere in the piece. There is virtually no element of predetermination in such a procedure.

Figure 11.8 Elegy for J.F.K., diplomatic transcription of sketch page

Introitus: T.S. Eliot in memoriam (1965)

Stravinsky’s use of block form as a compositional technique continued to evolve over the next two decades, and, when T. S. Eliot passed away in 1965, Stravinsky responded that same year by writing Introitus: T.S. Eliot in memoriam, a deeply expressive work of grief upon the loss of his friend, featuring once again a male chorus. This work is illustrative of Stravinsky’s use of serialism for expressive purposes; the combination of twelve-tone technique and the unusual instrumentation creates a heart-wrenching effect. Stravinsky writes that: ‘The only novelty in serial treatment is in chord structure – the chant is punctuated by fragments of a chordal dirge’ (Reference StravinskyStravinsky 1982: 66). This results in a texture that echoes the use of harmonic stasis as accompaniment to chant-like melodies. A performance of Introitus by the choir of Westminster Abbey was part of the ‘Homage to T.S. Eliot’ that took place at the Globe Theatre in London on 13 June 1965.

The first page of the sketch score, found at the Paul Sacher Stiftung, shows the evolution of his compositional process with sound blocks, the distinctive and regularly recurring ‘chordal dirge’ that is a trademark of the work. The combination of percussion instruments that Stravinsky used in Introitus serves as an evolutionary extension of the ritualistic profile that defines the Rite, while simultaneously reflecting the influence of the Rite on his process for an intensely personal epitaph.

Requiem Canticles (1965–6)

Requiem Canticles (1965–6) was commissioned by Princeton University in honour of a major benefactor in 1965, and Claudio Spies was instrumental in coordinating the details of the first performance at Princeton in 1966. Documents in the Claudio Spies collection at the Library of Congress confirm that he was in close communication with both Craft and Stravinsky concerning the serial analysis of the work, and he published a detailed analysis the following year, illuminating both the inter- and intra-symmetry of its nine sections.

It is notable that many of Stravinsky’s serial compositions are emotionally charged works. Though it was a serial composition, the chromatic beauty of Stravinsky’s interval-based writing is still plainly audible. Spies notes as much, saying that the ‘Lacrimosa’, of all the movements, is the ‘most meticulously and ingeniously organized’, and that it is ‘a paragon in this serene and deeply moving composition’ (Reference SpiesSpies 1967: 120–1). Stravinsky himself would pass away just five years after the premiere of Requiem Canticles. A performance of this work, conducted by Craft, at San Giovanni e Paolo in Venice before the composer’s body was taken to its final resting place at San Michele, made for a fitting musical epitaph. Requiem Canticles is written in the same Stravinskian language as his prior works, merely using a different vocabulary, tying together elements of all his stylistic periods and all of his characteristic instrumental and choral tendencies into a singular work of great brevity, yet packed with religious piety and intense emotion.