INTRODUCTION

In May 2016, the Tunisian Islamist movement Ennahda announced that it had left political Islam and wished to instead be labeled a Muslim Democratic party. This announcement culminated an ideological transformation of a party that was once an “anti-democratic and illiberal movement […] determined to impose religious law” (Cavatorta and Merone Reference Cavatorta and Merone2013, 858) to one that today accepts democracy and even secularism (see also Filali-Ansary Reference Filali-Ansary2016; Netterstrom Reference Netterstrom2015). Such an evolution is akin to that which led Christian Democratic parties in Europe to “acquire their distinctive character as religiously inspired yet secular parties that fully accept […] parliamentary democracy” (Kalyvas and van Kersbergen Reference Kalyvas and van Kersbergen2010, 189). The case of Tunisia’s Ennahda raises the question: What drives some Islamists to become Muslim Democrats?

The existing literature has put forth three primary explanations for when Islamists “moderate.”Footnote 1 The first emphasizes electoral incentives, drawing on the experience of the Christian Democratic Parties and the median voter theorem (Berman Reference Berman2008; Downs Reference Downs1957; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas1996; Karakaya and Yildirim Reference Karakaya and Yildirim2013; Tepe Reference Tepe2012). The second emphasizes state repression, arguing that Islamists moderate not to gain votes but rather to avoid being repressed (Brown Reference Brown2012; Cavatorta and Merone Reference Cavatorta and Merone2013; El-Ghobashy Reference El-Ghobashy2005; Hamid Reference Hamid2014; Künkler and Tezcur Reference Künkler and Tezcur2018). A final and particularly influential explanation highlights interactions with other political parties, which is thought to increase tolerance and an acceptance of pluralism (Browers Reference Browers2009, Reference Schwedler2013; Clark Reference Clark2006; Schwedler, Reference Schwedler2006, Reference Schwedler2011; Wickham Reference Wickham2004).

In addition to providing a new quantitative test of these hypotheses, this article also posits a fourth explanation: migration to secular democracies. Whether for education or exile, time spent in secular democracies could contribute to ideological change in at least three ways. First, there may be socialization effects of living in such environments, inculcating norms of democracy and secularism. Second, drawing on intergroup contact theory, time abroad may facilitate interactions with individuals of different faiths and thereby elicit more liberal orientations toward non-Muslims. Finally, Islamists living in secular democracies may find that secularism does not mean the violent repression of religion—as it had under their previous autocrats—but instead guarantees that all parties, religious or secular, have equal access to the state. These three causal mechanisms suggest that time spent in secular democracies may have an important effect in diffusing an acceptance of secularism to Islamists.

To test this theory, this article examines Tunisia’s Ennahda, today’s poster child of Islamist moderation. Following the ouster of Tunisian strongman Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, Ennahda swept Tunisia’s first free and fair elections, and headed a coalition government that stepped down following the passage of Tunisia’s 2014 constitution. Contrary to the will of some its hardline activists, Ennahda made critical compromises during the drafting of the new constitution, most prominently its decision to not make Islam or Islamic law the basis of legislation. These compromises were crucial to gaining the support of secular parties, and more generally to the success of Tunisia’s transition to democracy (Brownlee, Masoud, and Reynolds Reference Brownlee, Masoud and Reynolds2015; Hamid Reference Hamid2014; Marks Reference Marks2014).

Internally, however, Ennahda was divided on these compromises. This article uses an original dataset of parliamentary votes to identify which Ennahda MPs supported these compromises, and which did not. Collecting biographical data on each parliamentarian, I find that Ennahda MPs who had spent time in secular (in this case, WesternFootnote 2) democracies were consistently the most supportive of these secular compromises. Of the Ennahda MPs who had either studied or been exiled in secular democracies, more than 90% voted against making the Quran and Sunna the basis of legislation, in favor of preserving freedom of conscience, and in favor of prohibiting religious incitement to violence, compared with just 60–70% of their colleagues who had lived only in Tunisia. Beyond these three important votes, they also held more liberal voting records in general when analyzing all 1700 votes in the parliament in an ideal point analysis. These correlations are robust to the inclusion of a variety of demographic controls as well as several proxies for the existing hypotheses regarding electoral incentives, repression, and interactions with other parties.

To address concerns of endogeneity and explore possible mechanisms, this article then draws on several interviews conducted by the author with Ennahda MPs. These interviews suggest that the patterns in voting behavior were not mere correlations. Ennahda MPs acknowledged that their time abroad has had a causal effect on their beliefs, whether by socializing them into accepting democratic norms and practices, providing them with their first interactions with non-Muslims, or revising their conceptions of what secularism could entail. The voting and interview data thus suggest that migration to secular democracies may be one source of ideological change pushing some Islamists to become Muslim Democrats.

In terms of policy prescriptions, these results imply that scholarships, exchanges, and other opportunities for individuals to visit Western democracies—many of which have recently been cut—may be critical components of the West’s democracy promotion efforts. On the other hand, it is important to acknowledge that the results in the Ennahda case may be a function of the time period in which they visited the West. The post-9/11 backlash against Muslims in the United States and Europe, manifesting itself through increased harassment and hate crimes as well as government monitoring and manipulation, may very well mitigate the previously positive effects of time spent in Western democracies.

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 overviews the literature on Islamist moderation, whereas Section 3 outlines this article’s theory and its mechanisms. Section 4 introduces the case of Tunisia and the use of parliamentary votes, and presents results. Section 5 then addresses concerns of endogeneity and traces out possible mechanisms through interviews. The final section concludes with an eye toward policy prescriptions and future research.

MUSLIM DEMOCRATS

An important facet of democracy in religious contexts is what Stepan (Reference Stepan2000) called the “twin tolerations.” On the one hand, a democracy must tolerate the inclusion of religious actors in politics, allowing them to mobilize voters on the basis of religion and make religious arguments in policy debates. On the other hand, religious groups must tolerate democracy, avoiding actions that “impinge negatively on the liberties of other citizens or violate democracy and the law” (Stepan Reference Stepan2000, 39–40).

Two issues tend to be sticking points in religious parties’ toleration of democracy (Bhargava Reference Bhargava1998; Casanova Reference Casanova1994; Philpott Reference Philpott2007). The first is the notion of popular sovereignty. In a democracy, laws are made according to the ballot box and the popular will, not according to religious texts. There cannot, for instance, be government muftis that strike down laws because of their incompatibility with religion. A second sticking point is religious freedom, whether to practice other religions, different interpretations of the same religion, or no religion at all.

For democracy to survive in religious contexts, religious parties must accept popular sovereignty and religious freedom. Together, these principles form critical components of what many would consider secular democracy (Bhargava Reference Bhargava1998; Kuru Reference Kuru2009). For simplicity, I will therefore refer to these principles jointly as “secular democracy” or “secularism,” although I am cognizant that the term “secular” would not be used in the Middle East given the anti-religious connotations it carries in Arabic.Footnote 3

What factors would lead religious parties to “moderate” and accept these principles of secular democracy? A first set of explanations highlights the experience of the Christian Democratic parties in Europe. Drawing on the median voter theorem (Downs Reference Downs1957) and the moderation of socialist parties (Przeworski and Sprague Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986), Kalyvas (Reference Kalyvas1996) explains the moves of early twentieth century Christian Democratic parties to “deemphasize the salience of religion in politics” as an attempt “to appeal to broader categories of voters and strike alliances with other political forces” (p. 18). “In a process of symbolic appropriation, confessional party leaders reinterpreted Catholicism as an increasingly general and abstract moral concept,” (p. 244) downplaying Catholic doctrine in favor of “Christian values” and “religious inspiration.” “Catholicism was thus drained of its religious content even while being legitimated as a political identity” (p. 244).

While deemphasizing religion to appeal to the median voter may be appropriate for a democratic context, the moderation of Islamist political parties before the Arab Spring occurred in the context of competitive authoritarianism. As a result, scholars of Islamist parties have highlighted that moderation may occur to take advantage of limited regime openings or to avoid repression. El-Ghobashy (Reference El-Ghobashy2005), in her study of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, finds that “parties in electoral authoritarian regimes adapt to fend off state repression and maintain their organizational existence. It is not Downsian vote seeking but, rather, Michels’s self-preservation that is the objective of a party in an authoritarian regime” (p. 391). Similarly, Künkler and Tezcur (Reference Künkler and Tezcur2018) find that in Turkey and Indonesia, Islamist political parties “need to be sensitive to the preferences of […the judiciary and army] to avoid dissolution and military interference. Consequently, parties are more risk-averse and avoid controversial issues.” For Hamid (Reference Hamid2014), it is low levels of repression that breed moderation; for Cavatorta and Merone (Reference Cavatorta and Merone2013), even the high levels in Tunisia forced moderation.

Beyond fear of repression, another pathway thought to lead to Islamist moderation is inclusion. The seminal work behind this “inclusion-moderation hypothesis” is Schwedler (Reference Schwedler2006, Reference Schwedler2011, Reference Schwedler2013), who argues that once included into the formal political arena, Islamists will be forced to interact and work with other parties and individuals of vastly different viewpoints on university campuses, civil society, and electoral coalitions. Mirroring intergroup contact theory (Allport Reference Allport1954), Schwedler (Reference Schwedler2006) argues that these interactions can “reinforce the recognition of multiple worldviews and interpretations of how existing problems may be resolved,” in theory breeding greater tolerance of alternative viewpoints and an acceptance of pluralism (p. 11).Footnote 4

Each of these motives for moderation—electoral incentives, fear of repression, interactions—has been theorized at the party level. However, the mechanisms likely operate at the individual level. Individuals interact with other individuals of differing worldviews. Fear of repression is a psychological process at the individual level, and individual experiences—such as having personally been imprisoned—may heighten the salience of this fear for certain individuals. Electoral incentives would similarly vary based on the characteristics of the district that each individual candidate seeks to represent, with stronger incentives to moderate in districts where the party is weaker.

Despite the mechanisms occurring at the individual level, most of the literature draws on case studies of Islamist parties (the Islamic Action Front in Jordan, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, etc.) or of a handful of individuals at the top of these groups. To truly test these theories, we would need considerable data at the individual level. The Arab Spring has provided a new opportunity on this front, as Islamist parties made significant electoral gains in Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and elsewhere in the region. In Tunisia, for instance, Ennahda won 89 seats in the National Constituent Assembly, enough to conduct a statistical analysis of Ennahda parliamentarians. This article seeks to take advantage of this opportunity to test theories of moderation through individual-level data. Moreover, beyond this methodological contribution, this article also offers another factor that may affect Islamist moderation: migration to secular democracies.

SECULAR DIFFUSION

Recent literature finds that migration to advanced democracies can generate not only economic remittances but also political ones. Spilimbergo (Reference Spilimbergo2009), for instance, finds that countries that send more students to study in the West subsequently have higher levels of democracy (see also Atkinson (Reference Atkinson2010) and Docquier et al. (Reference Docquier, Lodigiani, Rapoport and Schiff2016)). Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2010) similarly find that countries with greater linkages to the West see greater diffusion of democracy. At the individual level, Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow (Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow2010) find that Mexicans who had temporarily lived in the United States or Canada were significantly more tolerant, less satisfied with Mexican democracy, and more politically active than their counterparts who had not traveled abroad. Corroborating these attitudinal results, Batista and Vicente (Reference Batista and Vicente2011) conduct a behavioral experiment to find that Cape Verdeans who had lived in the United States were more likely to demand political accountability at home on their return. Even at the elite level, Gift and Krcmaric (Reference Gift and Krcmaric2017) find that Western-educated leaders are more likely to democratize. Migrants to advanced democracies, whether for work or study, generally develop more positive views of the destination country and of democracy, and are more politically active on their return home (Careja and Emmenegger Reference Careja and Emmenegger2012; Chauvet, Gubert, and Mesple-Somps Reference Chauvet, Gubert and Mesple-Somps2016; Chauvet and Mercier Reference Chauvet and Mercier2014; Dana Reference Dana2017).

Beyond diffusing support for democracy and political participation, I argue that time in secular democracies may also diffuse an acceptance of secularism. In particular, I contend that Islamists who have lived in secular democracies are more likely to endorse popular sovereignty and religious freedom than their counterparts who have not. I posit three mechanisms by which these effects may occur: socialization, intergroup contact, and political learning.

First, Islamists living in secular democracies may be socialized into accepting secular norms. Socialization in foreign countries is especially likely to occur when a migrant’s personal situation has improved, as they implicitly or explicitly credit their new country’s institutions and values for this improvement (Careja and Emmenegger Reference Careja and Emmenegger2012). Chauvet, Gubert, and Mesple-Somps (Reference Chauvet, Gubert and Mesple-Somps2016) contend that “when individuals increase their personal economic resources in migration, they may be tempted to adopt the values and ideas of the country that they perceived as being the source of this expansion” (p. 14). Such comparisons between one’s socioeconomic situation in their home country vs. abroad have also been shown experimentally to impact political attitudes (Huang Reference Huang2015).

For Islamist migrants, the improvement may not only be material but also physical and psychological. Especially for those fleeing repression in their home countries, their newfound freedom in secular democracies should similarly incentivize them to take up the values and norms of their host country. While today, Islamists in the West may be subject to harassment—a topic I return to in the conclusion—the time period that the Islamist leaders in this study had moved to the West (pre-9/11) was generally more permissive and free than their home countries. As a result, they may have been socialized into accepting not only democracy but also secularism.

Second, Islamists living in secular democracies may become more tolerant of non-Muslims as a result of increased intergroup contact. Since Allport (1954), there has been a large literature demonstrating that intergroup contact can reduce prejudice (Pettigrew and Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006), including through field experiments (i.e., Broockman and Kalla Reference Broockman and Kalla2016; Mo and Conn Reference Mo and Conn2018; Simonovitz, Kezdi, and Kardos Reference Simonovitz, Kezdi and Kardos2018). For many Islamists coming from Muslim-majority countries, living in the West provides one’s first opportunity to meet and interact with non-Muslims. In passing, some scholars of Islamism have noted that such interactions may have contributed to greater openness and tolerance. Wickham (Reference Wickham2004), for instance, in her case study of the Wasat party in Egypt, finds that the party’s leader, Abu Ayla Madi Abu Ayla, moderated in part due to his “forty-seven trips abroad, including several trips to Europe and the United States,” which along with his interactions domestically led him to “the recognition that ‘we don’t monopolize the Truth’” (p. 220).

Moreover, one mechanism through which intergroup contact tends to reduce prejudice is through perspective-taking, or putting oneself in the shoes of another. Broockman and Kalla (Reference Broockman and Kalla2016) find that a 10-minute conversation encouraging active perspective-taking can have months-long effects, whereas Simonovitz, Kezdi, and Kardos (Reference Simonovitz, Kezdi and Kardos2018) corroborate these effects through an online perspective-taking game. For Islamists, and Muslims more generally, living in Western democracies tends to provide a first-hand experience as a minority, potentially making them empathize with and more tolerant of minorities on their return home. If briefly imagining oneself in another’s shoes can have major effects, it stands to reason that actually being a minority for a decade or more may also engender similar effects.

Finally, living in secular democracies may trigger political learning about what secularism could entail. For many Islamists, autocrats in their home countries had repressed political Islam under the guise of secularism. In Turkey and Tunisia, among others, autocrats had forcibly secularized their public spheres, repressing public displays of piety such as wearing the veil and suppressing political expressions of faith. Such forced secularism stands in stark contrast to the secularism practiced by most Western democracies, which permit political parties to be inspired by religion and even to make religious arguments in political debates. Although secularism in an authoritarian context often means the repression of religion, secularism, as practiced in these democracies, ensures that all parties (including religious ones) have equal access to the state—what Bhargava (Reference Bhargava1998) calls “principled distance.” Living in certain secular democracies may therefore update an Islamist’s expectations of what secularism will entail for their political future. An important exception is France, which pursues “aggressive secularism” (Kuru Reference Kuru2009). This political learning mechanism may therefore operate more strongly in the other secular democracies.

As a result of socialization, intergroup contact, and political learning, living in secular democracies may drive Islamists to consciously or subconsciously develop more positive attitudes toward secularism. On their return to their home countries, they are likely to hold more secular political attitudes than their peers who had not traveled abroad. Although I make no claim as to how long abroad is “enough,” I hypothesize that on average, the longer Islamists remain abroad the more likely they are to accept secularism.

It is not readily apparent that secularism would diffuse to Islamists living in secular democracies. Islamists, like other religious conservatives, are generally considered more resistant to change than nonreligious actors. Religious principles, especially when textually derived or divinely ordained, are viewed as largely fixed attributes, difficult to compromise over let alone abandon. Moreover, there are notable examples of Islamists who instead became more conservative while in the West. Sayyid Qutb was so shocked by the loose morals he saw in Colorado that he instead moved toward a stricter form of Islamism. Islamists who travel to the West may very well be more conservative than those who remain in their home countries.

In this article, I test whether on average, Ennahda MPs who had gone abroad to secular democracies were more secular or more Islamist than their counterparts who remained in Tunisia. This sample is of course limited in at least three ways. All of the Islamists who went abroad in the sample (a) decided to return to Tunisia on democratization, (b) ran in elections for Ennahda, and (c) won those elections. Each of these limitations could introduce bias: Islamists who radicalized into violent extremism would not appear in this sample nor would Islamists who moderated to the point of joining secular partiesFootnote 5 or remaining abroad. However, it is also a useful sample from the standpoint of assessing the Islamists who come to power upon democratization. Among these Islamists in political office, I contend that time abroad in secular democracies has on average a secularizing rather than Islamizing effect.

ISLAMIST MODERATION IN TUNISIA

Case Selection and Background on Ennahda

The case of Tunisia is a particularly appropriate venue to test theories of moderation. Tunisia has emerged as the single success story of the Arab Spring, an accomplishment in no small part due to Ennahda’s willingness to compromise on a number of difficult issues. As this article will show, one of the critical compromises—accepting secular democracy—was facilitated by a decade-long process of moderation among a wing of Ennahda in exile in Western capitals. With Ennahda now hailed as a model of Islamist moderation, it is critical to understand how it came to be where it is today.

Like elsewhere in the region, Islamism began in Tunisia in response to both domestic and international factors. Domestically, the overtly secularizing reforms of Tunisia’s founding father, Habib Bourguiba—who notoriously drank orange juice on national television during the fasting month of RamadanFootnote 6—unsettled the more conservative sentiments of many Tunisians. Tunisian Islamism also benefited from a broader, regional shift toward political Islam in the 1970s and 1980s following the disillusionment with Arab nationalism with the 1967 defeat to Israel and the inspiration of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. In 1981, preacher and philosophy teacher Rached Ghannouchi established the Islamic Tendency Movement (MTI). Although the Tunisian regime closed any avenues for the MTI’s formal political participation, the movement was able to operate, agitate, and proselytize on university campuses and in civil society (Wolf Reference Wolf2017).

The rise to power of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 1987 initiated a brief liberalization of the regime. The MTI rebranded itself as the Ennahda (Renaissance) movement and fielded candidates on an independent list in the 1989 elections. Threatened by its popularity, Ben Ali soon cracked down on Ennahda, decimating the movement and driving its members into exile, imprisonment, or underground. For the next two decades, Ennahda would remain divided, one wing abroad in Western capitals (“Ennahda fi al-kharij”) and the other in prison or underground in Tunisia (“Ennahda fi al-dakhil”).

Following Ben Ali’s ouster in 2011, Ennahda finally reunited in Tunisia and moved quickly to prepare itself for the 2011 National Constituent Assembly (NCA) elections. Ennahda swept these elections, winning the largest share of the vote with 37% and receiving 89 of 217 seats in the assembly. Ennahda formed a “troika” government with two other parties, Congress for the Republic (CPR) and Ettakatol. In the summer of 2013, following the assassination of two liberal politicians in Tunisia and a military coup in Egypt, the troika government faced massive protests forcing them to step down from power in an agreement brokered by four civil society organizations known as the Quartet. Ennahda remains a powerful political force, helping to form a coalition government in 2015 and lead one today.

During the troika government’s tenure (2011–14), Ennahda made a number of critical compromises in accepting the principles of secular democracy. The first, perhaps the most important, was to not include in the 2014 constitution a reference to shari‘a, or Islamic law, as the basis of legislation. Such a clause would have directly limited popular sovereignty in crafting legislation, contradicting democratic norms. Early in the transition, Rached Ghannouchi, the head of Ennahda who had been exiled in London, assured Tunisia’s secularists and the international community that the first article of the constitution—that the official language is Arabic and religion is Islam—would be left as is; “there will be no other references to religion in the constitution.”Footnote 7

Yet that campaign promise did not sit well with some in Ennahda. In the spring of 2012, conservative firebrands Habib Ellouze and Sadok Chourou, both of whom had spent much of the last two decades in Tunisian prisons, forced an internal debate on the matter. The debate was protracted, reinforcing fears among Tunisia’s secularists that Ennahda harbored a hidden, fundamentalist agenda (Marks Reference Marks2014, 20–2). Although Ennahda’s conservative wing lost that round, they had not given up. When it came time to draft the new constitution, they introduced amendment 42 to article 1, which would have added to the constitution’s first article: “the Quran and the Sunna are the main sources of its [Tunisia’s] legislation.” If a reference to the shari‘a had been ruled out, perhaps a reference to the sources of the shari‘a—the Quran and the Sunna—could gain enough votes.

When it came up for a vote on January 4, 2014, Ennahda MPs were uncharacteristically divided (Figure 1).Footnote 8 Twenty-two of 89 Ennahda MPs (25%) voted for this amendment, whereas 38 stuck to the party line, which was to abstain. Twelve were absent during the vote, whereas another 17 voted no. Although the amendment ultimately failed, it generated important and illuminating internal disagreement that will permit us to separate Ennahda MPs into more secular and more Islamist on the issue of popular v. divine sovereignty.

FIGURE 1. Distribution of Ennahda Votes, Quran, and Sunna as Basis of Legislation January 4, 2014

Additional controversies revolved around religious freedom, the second pillar of secularism. Amendment 62 of article 6, voted down on January 4, 2014,Footnote 9 would have eliminated the constitution’s guarantee to freedom of conscience, commonly interpreted as permitting atheism. As MPs were debating this amendment, Ennahda MP Habib Ellouze called secular MP Mongi Rahoui an “enemy of Islam,” prompting secularists to introduce a new amendment to article 6 prohibiting takfir—the labeling of another Muslim as an apostate, a religious incitement to violence.Footnote 10 This amendment passed on January 5, 2014.Footnote 11 The Ennahda bloc was considerably divided on both of these votes as well (see online appendix).

In short, Tunisia’s National Constituent Assembly (NCA), tasked with drafting the 2014 constitution, was the site of major compromises, including on secular-religious issues. Why did some Ennahda MPs vote in favor of these secular compromises, whereas others did not? In particular, did the Ennahda MPs who had lived in secular democracies vote more secularly?

Dependent Variables

I pursue two strategies to separate Ennahda MPs into “more secular” and “more Islamist.” The first is targeted: to examine just the three major compromises highlighted above, including (1) whether to make the Quran and Sunna the basis of legislation, (2) whether to allow freedom of conscience, and (3) whether to ban the practice of takfir. Case knowledge suggests that these were three of most divisive compromises, and all directly relate to the secular-religious cleavage. I also present a principal components analysis (PCA) combining these three votes.Footnote 12

While these three votes allow us to hone in on the primary issue of interest, they may be biased by idiosyncrasies of these particular votes. The second approach is therefore more comprehensive: to analyze all 1,731 roll-call votes in the NCA to extract an underlying ideal point, or ideology, for each Ennahda MP.Footnote 13 The ideal point approach is similar to that which is used in analyzing the U.S. Congress, and allows us to separate Ennahda MPs as more liberal or more conservative based on their entire voting records. The limitation is that the separation is influenced not only by votes related to secularism, but also other divisive issues for Ennahda, such as transitional justice.Footnote 14 The individual votes and the ideal point analyses are therefore different but complementary approaches to measuring MPs’ ideologies.

For both analyses, my preferred approach is to code an ordinal variable with three voting options: yes, abstain, or no (with absences coded as missing data). While many ideal point models treat abstentions as missing data as well, in our case they are quite informative. Rather than simply meaning “don’t know,” abstentions are meant to signal that: “I don’t fully agree with the position of my parliamentary group,” explained one Ennahda MP. “An abstention sends a message to my parliamentary group that maybe we should discuss a little more about this position.”Footnote 15 Ennahda MP Osama al-Saghir concurred, arguing that an abstention means that “I like the idea but the article as written is not as I think it should be.”Footnote 16 At least in the Tunisian context, abstentions register an intermediary vote between yes and no, and thus provide important information about MPs’ preferences.

For the individual votes (approach 1), I therefore code those MPs voting secularly—i.e., “no” to the Quran/Sunna, “no” to removing freedom of conscience, and “yes” to banning takfir—as a 1. Those voting Islamist are coded as −1, and those abstaining as a 0. As the dependent variable is ordinal, I run ordered logistic regressions using the lrm R function.

In conducting the ideal point analysis (approach 2), I use the ordinal Item Response Theory (ordIRT) model developed by Imai, Lo, and Olmsted (Reference Imai, Lo and Olmsted2016) that permits abstentions as a middle category between yes and no. However, as a robustness check, I also employ the more standard binary model that excludes abstentions, using the “w-nominate” package (Poole et al. Reference Poole, Lewis, Lo and Carroll2011). Unlike ordIRT, w-nominate allows the user to separate MPs along multiple dimensions, and I extract the first dimension on the assumption that the secular-religious cleavage was the primary cleavage during this time (Berman and Nugent Reference Berman and Nugent2015; Brownlee, Masoud, and Reynolds Reference Brownlee, Masoud and Reynolds2015).

The Cost of Voting

The use of parliamentary votes to infer Islamists’ preferences is a break from the literature, which instead measures ideology through public or private statements, such as a party platform, press statement, or private interview with the researcher.Footnote 17 Given the relatively costless nature of these statements, however, one potential problem is preference falsification: especially when Islamists are speaking with the West, they may have incentives to misrepresent their true beliefs to appear more moderate, or selectively omit beliefs that would make them appear hostile. These sources may therefore provide little guidance for how Islamists will actually behave upon coming to power.

These concerns are mitigated when examining parliamentary votes. Votes are not only an actual measure of what Islamists do once in power but they are also costly. Ennahda has maintained the highest party discipline in Tunisia; its MPs face considerable social and organizational pressure to toe the party line. Divergences from the party line carry real consequences, including a lower likelihood of being renominated by the party to run in subsequent elections. They also have a direct, substantive impact on the constitution, laws, and future of the country. As a result, divergences from the party line, whether in a more liberal or conservative direction, likely reflect an MP’s strongly held beliefs and are unlikely to be preference falsification.

To provide evidence of one such cost, I examine whether those who voted against the Ennahda party line on any of the three votes outlined above were less likely to be renominated by the party to run in the 2014 elections. Divergences from the party line were coded as either voting “yes” to the Quran and Sunna as the basis of legislation, “yes” to removing freedom of conscience, or “no” to banning takfir.

Figure 2 finds strong evidence for this proposition. Of the 86 MPs who chose to remain within Ennahda, those who diverged from the party line were 30% less likely to be renominated than those who stuck to the party line (p = 0.0066), even when controlling for a number of demographics (see appendix). Similar results obtain for the ideal point analysis, where more conservative MPs were significantly less likely to be renominated (p = 0.00164, appendix). An interview with Ennahda executive board member and MP Sahbi Atig confirmed that although party lists were drawn up by each governorate level office of Ennahda, the executive board “intervened in four or five governorates” to block certain individuals. Atig in particular mentioned the district of Sfax 2, where the aforementioned MP Habib Ellouz was not renominated.Footnote 18

FIGURE 2. Likelihood of Renomination by Votes on Secularism

Interviews also revealed that MPs knew about this cost ahead of time. In the lead-up to controversial votes, for instance, the Ennahda headquarters had individually called those MPs leaning toward voting against the party line to inform them that they may not be renominated if they do so. MP Mohamed Saidi recalled that: “We were called, we were even threatened, if you vote for this you are killing your political future!”Footnote 19

Given this cost of voting, diverging from the party line likely reflects an MP’s strongly held convictions and preferences, and is unlikely to be cheap talk or preference falsification. Parliamentary votes should thus provide a fairly accurate measure of moderation.

Independent Variables and Descriptive Statistics

Based on the theory of secular diffusion, I hypothesize that Ennahda MPs who studied or were exiled in secular democracies would vote more secularly in the NCA than their counterparts who had not. Data for time spent in secular democracies come from public biographies of the MPs. Each MP submitted a detailed biography to al-Bawsala, a watchdog organization that monitored the parliament.Footnote 20 Each biography was cross-checked with other online sources as well as with the Ennahda headquarters.Footnote 21

Of the 89 Ennahda MPs, 18 had studied or were exiled in secular democracies in the West, including Belgium (1), Canada (1), France (12), Germany (1), Italy (2), and the United States (1). These 18 MPs spent an average of fifteen years abroad, ranging from two to thirty years (see histogram in online appendix), and occurring primarily in the 1990s and 2000s. In addition, nine other MPs had studied or been exiled in other authoritarian regimes in the region (Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, Qatar, and Sudan). These MPs can serve as a placebo demonstrating that it is not traveling abroad that is important but the destination country in particular. The remaining 62 MPs had only lived in Tunisia.

Descriptive statistics provide initial support for the theory. Figure 3 plots the votes on whether the Quran and the Sunna should be a basis of legislation for MPs who have spent time in secular democracies in the West (right), lived in autocracies in the Middle East and North Africa (left), or lived only in Tunisia (middle). Of the 16 who lived in the West and were present for this vote, only one (6%) voted for the Quran and the Sunna to be the basis of legislation, whereas the remaining 15 either voted no or abstained. By contrast, those who only lived in Tunisia (middle) were more conservative, with 32% voting for the Quran and the Sunna. Finally, those who had lived in other MENA countries were the most conservative, with 57% voting for the Quran and the Sunna. In other words, Ennahda MPs who had lived in the West were about 25 percentage points less likely to vote for the Quran and Sunna to be the basis of legislation than their counterparts who had lived only in Tunisia, a difference which a t-test reveals is statistically significant at p = 0.007.

FIGURE 3. Descriptive Statistics, Quran, and Sunna

Similar results obtain for the other two secularism votes. Not a single Ennahda MP who lived in the West voted to remove freedom of conscience, whereas 22% of those who never left Tunisia did so (p < 0.000). Meanwhile, 89% of those who lived in the West voted to prohibit takfir, compared with only 66% for their colleagues at home (p = 0.06).

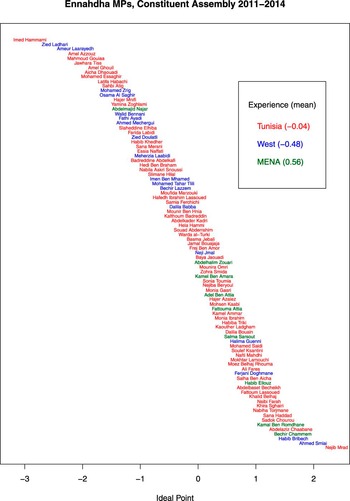

The ideal point analysis mirrors these results. Figure 4 plots the ideal points of the 89 Ennahda MPs from most liberal (left) to most conservative (right).Footnote 22 As can be seen, Ennahda MPs who lived in the West (names in blue) are visually more concentrated toward the left than right, with a mean of −0.48, compared with −0.04 for those who lived only in Tunisia (red) and 0.56 for those who lived in other MENA countries (green).

FIGURE 4. Ideal Points of Ennahda MPs (Left = Liberal and Right = Conservative)

For the purposes of visualization, these descriptive plots presented a simple dichotomous variable of whether an Islamist MP had lived in a secular democracy. However, there is reason to believe that the length of time one stayed abroad may matter as well. On average, the longer an Islamist MP lived abroad, the more likely he or she is to become secular. Accordingly, in the regression models below, I use the length of time, presenting the dichotomous variable in the appendix. The length of time is standardized by dividing by two standard deviations (Gelman Reference Gelman2008).

Control Variables

The introduction of regression analysis to studies of moderation allows us to isolate the link between living in the West and moderation while controlling for a number of covariates. For each dependent variable, I present two models. The first controls only for demographic characteristics: age, gender, level of education, whether they have a theology degree, as well as fixed effects for hometown (coded as coast, southwest, southeast, interior, or northwest) and prior occupation (professor, teacher, lawyer, scientist, business, doctor, government, other, or none).

The second model then adds several variables capturing the existing theories of Islamist moderation outlined in the literature review. To capture the interactions with other political parties that Schwedler (Reference Schwedler2006) highlights in the inclusion-moderation hypothesis, I control for activism, coded as participation in student unions or professional syndicates. To account for the repression that is also thought to breed moderation, I control for whether the MP had ever been in prison. Nugent (Reference Nugent2017), for instance, argues that since Ennahda and secular politicians had both been repressed, their joint experience in jail may breed ideological convergence, moderating Ennahda MPs who had been imprisoned. Finally, to capture the political incentives MPs might have to moderate to appeal to the median voter, I include three additional variables:

1. Ennahda Vote Share: MPs may vote more secular in those districts where Ennahda was weak. Where Ennahda’s vote share in 2011 was low, it would need to reach out to a larger constituency to win reelection, and thus would have more incentives to moderate.

2. CPR Vote Share: Of all the secular parties, the Congress for the Republic (CPR) was the most friendly to Islamism, and indeed included some former Islamists like Imed Daimi among its leadership. CPR’s success in a district may therefore signal a friendly constituency for Islamism even beyond Ennahda’s base. CPR vote share should therefore be correlated with less secularism.

3. Place on Party List (inverted): The lower an MP is on Ennahda’s party list, the more incentive he or she may have to stick to the party line to advance up the ladder. The opposite effect could also occur: Ennahda may have placed them lower down the list precisely because they were known to be less loyal to the party line.Footnote 23 I invert the list so that regardless of the number of seats Ennahda won in a governorate, those at the bottom receive the same low value (1).Footnote 24

4. Electoral District: Finally, I include a dummy variable indicating whether the MP represents a district in the coast or abroad (1), rather than in Tunisia’s interior regions (0), on the assumption that these districts are likely to be more secular. Each of the eight Ennahda MPs representing constituencies abroad (Italy, France, Germany, Americas, etc.) had themselves traveled abroad. Including this control thus demonstrates that the effect of the West is not driven by those representing constituencies abroad.Footnote 25

Several of these variables occur posttreatment, and thus the effect of living in the West may be running through them. For instance, Ennahda may have placed MPs who lived abroad higher (or lower) on the party list or in governorates that were competitive (or uncompetitive). In short, because some of these variables occur “posttreatment,” we may expect the effect of living in the West to weaken; yet, it is important to test the robustness of the results to these alternative, electoral incentive explanations.

Results

Table 1 presents the first dependent variable: the individual secularism votes, including on the Quran/Sunna as the basis of legislation (models 1–2), freedom of conscience (3–4), the prohibition of takfir (5–6), and the principal components analysis of the three (7–8). For each dependent variable, positive values indicate more secular votes.

TABLE 1. Secular Diffusion and Individual Secularism Votes

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

The coefficient of interest is the time spent in the West, which should be positive if the secular diffusion thesis is correct. In all eight models, the effect of living in the West is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01). MPs who had lived in the West voted significantly more secularly, even when controlling for demographic variables and alternative explanations.

Included in all models was also the placebo: those Ennahda MPs who also lived abroad, but in other (authoritarian) Middle Eastern and North African countries. Those elsewhere in the MENA region were no more secular than those who remained in Tunisia, and on the contrary were leaning more conservative.Footnote 26 It is not simply being abroad, but being abroad in secular democracies, that is correlated with secularism.

The electoral incentives also perform well in predicting these secularism votes. Ennahda MPs representing districts where Ennahda and CPR did well, signaling a relatively more Islamist-friendly constituency, voted more Islamist, lending credence to the median voter theorem at the governorate level. Place on the party list also reached significance, with MPs higher on the list voting more secularly.

Other variables attain significance for some votes but not others. Women were more likely to vote against the Quran and Sunna as the basis of legislation, whereas higher educated MPs were less likely to ban takfir. Activism, representing MPs who had been involved in student unions or professional syndicates, was correlated with support for freedom of conscience and banning takfir, but not for the other models. Imprisonment had no effect on these votes.

Table 2 presents the results for the second approach: the ideal points that were extracted from all 1,731 votes in the assembly. The sign is flipped from Figure 4, with positive values now indicating more liberal ideal points. Models 1–2 employ the ordinal ideal point analysis, whereas 3–4 employ the binary version (excluding abstentions).

TABLE 2. Secular Diffusion among Ennahda MPs (OLS)

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

In all four models, the effect of living in the West is again positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05). MPs who had lived in the West held significantly more liberal ideal points, even when controlling for demographic variables and alternative explanations. Overall, having lived in a secular democracy appears to be one of if not the most important predictor of liberal voting records.

For the ideal point analysis, few of the covariates were significant. The only consistently significant covariate was place on the party list, with MPs higher up on the list having more liberal ideal points. Prior activism was correlated with more liberal ideal points in the ordinal model but not in the binary. Imprisonment again had no significant effect. In short, the existing explanations for Islamist moderation—electoral incentives, repression, and interactions with other parties—do a mixed job at best in predicting secularism, at least as measured herein. These results of course do not rule out the potential importance of these factors in moderating Ennahda MPs in other issue areas, for instance, on women’s rights or lustration, but appear to have little effect on breeding an acceptance of secularism.

Tables 5–6 (appendix) demonstrate that results hold when using the dichotomous West variable rather than the length of time spent abroad. Tables 7–8 experiment with separating those who traveled to the West for education from those fleeing repression. Theoretically, the mechanisms should operate for both, although mechanism 1 may be stronger among those fleeing repression (and thus whose personal situation arguably improved more). While the distinction is not perfect (6 MPs did both), we can add both education and exile into the regression. Results are inconclusive: for the ideal point analysis, it is those seeking exile who are driving the secularizing effect of living in the West. However, for the individual secularism votes, those seeking education claim the stronger effect, including significant effects for banning takfir and for the PCA.

In sum, one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of secularism among Ennahda MPs was living in secular democracies, whether for education or exile.

Alternative Explanations

Before demonstrating support for my hypothesized mechanisms, it is important to first address two alternative explanations. First, perhaps Ennahda MPs who had lived in the West became more secular not because of any secular diffusion from these countries but rather because being in the West facilitated meetings and close relationships with Ennahda leader Rached Ghannouchi, who was exiled in London. As a result, these MPs may be voting more secular—i.e., in the way Ghannouchi, as head of the party, wants them to vote—because Ghannouchi has greater personal influence over them.Footnote 27 This explanation, however, would imply that these MPs should across the board vote closer to Ghannouchi and the party line than other MPs, not just on votes related to secularism. To test for this explanation, we can calculate each MP’s overall propensity to diverge from the party line using all 1,731 votes in the NCA. I calculate the party line for each vote as the modal vote (yes, no, or abstain) on each bill. In other words, rather than calculating who is more liberal and more conservative, we can examine who is most likely to diverge from the party line whether in a liberal or conservative direction.

I find that Ennahda MPs who had lived in the West did not vote significantly closer to the party line than MPs who had remained in Tunisia (see figure in appendix). On average, Ennahda MPs broke with the party line 13% of the time. MPs who had lived in the West voted against the party line 12.1% of the time, whereas MPs who lived only in Tunisia did so at 13.7%. This difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.24). We can therefore reject the alternative explanation that Ennahda MPs who lived in the West happened to be closer to the party line or to Ghannouchi than other MPs.Footnote 28

A second and potentially more damaging alternative explanation would be selection bias: perhaps those Ennahda MPs who lived in the West chose to do so because they were already more secular—it was not that they became more secular, but rather they already were. Unfortunately, there are no data on these MPs’ ideological preferences before going abroad to be able to directly test for selection bias. Although we are not able to rule out endogeneity entirely, allow me to address this concern in three ways, each of which has its flaws but together reveal a consistent story.

The first approach is to examine if certain covariates that we expect to be correlated with secularism are associated with going to the West. For instance, we may think that age or education may be correlated with secularism. Similarly, the results above suggest that women may be more secular, whereas in terms of occupation, professors/teachers were leaning more secular.

Beyond these individual-level covariates, we can examine if those who traveled to the West were from more secular districts. We can measure the religiosity of each district in three ways: First, we can use Ennahda’s performance in the 1989 elections, the one time that it was permitted to contest elections under autocracy.Footnote 29 This variable ranges from 0 in multiple districts to 30% in Tunis 2. Second, we can examine the number of mosques per capita in each governorate,Footnote 30 a variable that ranges from 1.9 mosques per 10,000 citizens in Gabes to 11.6 in Monastir. Finally, we can exploit Tunisia’s regional divisions, as citizens from the wealthy coastal regions tend to be more secular (Berman and Nugent Reference Berman and Nugent2015) than their counterparts in the impoverished interior, Northwestern, or Southern regions (Boughzala and Hamdi Reference Boughzala and Hamdi2014).

Table 3, however, does not show evidence of any these selection effects. Ennahda MPs who had lived in the West were roughly the same age, had the same level of education, and were not significantly different in their occupations than those who stayed in Tunisia. Moreover, they were no more likely to hail from the coast or from less religious districts. Where there is imbalance—gender—the results actually cut in the opposite direction. Those who went abroad were more likely to be male and thus less secular. Although these are admittedly crude proxies for secularism, they suggest that the MPs who lived in the West were not demographically likely to already be more secular.Footnote 31

TABLE 3. Covariate Balance among Ennahda MPs

A second approach is to subset the data to a group where going abroad was more plausibly uncorrelated with secularism. In particular, we can exploit the massive political crackdown on Ennahda in 1991, in which all members of Ennahda, whether more secular or more Islamist, faced the prospect of arrest. In a private interview with the author, the director of internal security within the military from 1988–2000 noted that the 1991 crackdown was wide-reaching and indiscriminate, targeting leaders, members, and even sympathizers of Ennahda.Footnote 32 Ennahda claims that 30,000 of its members were imprisoned during this period—the largest crackdown in Ennahda’s history.Footnote 33

Whether an Ennahda member managed to escape arrest during the 1991 crackdown was primarily a matter of chance. Interviews with several of Ennahda MPs are illustrative in this regard. Ennahda MP Mohamed Zrig, who managed to escape from his hometown in Gabes in southern Tunisia to Canada, explained:

[President] Ben Ali wanted to arrest everyone, whether a leader or an average member! You could call it chance or call it circumstance. I, for instance, was not in my house the day they [the police] came for me. It was a holiday but I was still at work. Others were captured at the border, or Libyan officials sent them back to Tunisia, etc. The possibility of being arrested was there for all of us. It was luck.Footnote 34

MP Walid Bennani, from the interior town of Kasserine, who managed to escape to Belgium, likewise attributes his escape to chance:

I took a louage [collective taxi] from Kef to [Sakiet] Sidi Youssef on the border with Algeria. There were checkpoints along the way. I am a believer—if Allah had written about my arrest I would have been arrested. At one particular checkpoint, police were checking every car in front of us. The police even had “wanted” pictures on them. But the driver of the taxi happened to know one of the police officers, and told him yalla, let’s go. It was pure luck that I made it out.Footnote 35

These interviews suggest that whether an Ennahda MP managed to flee or was arrested in 1991 was unrelated to their level of secularism: all were targeted for arrest. To conduct this analysis, I will subset to MPs who were at least 18 years old and in Tunisia in 1991 (78 of 89 MPs), and therefore could have been arrested. The primary independent variable here, Exile in 1991, will lump together all MPs who fled the country, whether going to the West or MENA.Footnote 36 Although escaping Tunisia is plausibly uncorrelated with secularism, where they settled is likely not.

Table 9 (appendix) presents the results. Across all six dependent variables—the two ideal point analyses, the three individual votes, and the PCA—MPs who had been exiled in 1991 voted significantly more secularly than those who remained in Tunisia. This finding is particularly surprising, given that now the reference category includes several MPs who had gone abroad before 1991.

The final piece of evidence against selection bias is the strongest: Ennahda MPs themselves admit that their time abroad had a causal impact on their beliefs. Thus, even if there was some selection bias in who went abroad, there was at least an additional effect of living in the West on their preferences. Although we will hear from more MPs who had gone abroad in the mechanisms section, for now, it will suffice to hear from Mohamed Zrig, who spent 20 years in Canada:

In the 1990s and 2000s, we had different experiences. There was the experience of those in prison and those abroad. Both experiences were very rich. Our brothers who were in prison spent their time studying the history of the movement, its ideology, how it developed. For us abroad, we benefited a lot from the West. I realized how democracy works, how citizens are respected. And in addition, I learned the mechanisms: how to practice democracy, how to practice respect for citizens by the regime, how to apply democracy in reality.Footnote 37

Even those who were imprisoned recognize this ideological moderation among those exiled in the West.Footnote 38 Conservative Ennahda MP Sadok Chourou, who spent almost two decades in prison, affirmed:

It is true that the brothers who were in the Diaspora have been affected by the environment of Europe and America. […] This influence created new intellectual orientations, especially politically with regards to Islamic thought. [Their outlook] has changed dramatically since 1991. […] This has made the movement head in a different direction. Footnote 39

Ennahda MP Habib Ellouze, who also spent two decades in prison, concurred:

Experiences matter. Those in prison were influenced by the prison experience, those in hiding were influenced by that, and those in exile were also influenced. There is no doubt that the latter group had to interact more with Western culture […] and adapted to their ideas. Footnote 40

In sum, even if there was an initial selection effect in who went abroad, Ennahda itself recognizes that its experiences in exile have at least had an additional effect. To see why, and to explore the mechanisms by which this effect occurred, I turn next to several interviews with these Ennahda MPs.

MECHANISMS

To select which MPs to interview, I followed Seawright and Gerring (Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) in choosing “crucial” or “pathway” cases—cases for which, statistically, time abroad appears to have had a major effect. These cases, where the effect size is largest, should be where the mechanisms are clearest.

To determine these crucial cases, I ran the regression predicting Quran/Sunna votes with and without the West variable, and plotted the change in residuals in Figure 5. A positive change is where the model’s prediction of how an MP would vote improved after taking into account whether they spent time in secular democracies. The MPs in the top right, therefore, are those who lived in the West, and for whom that experience appears to have mattered, after controlling for all other covariates.

FIGURE 5. Interviewee Selection Based on Quran/Sunna Vote

I was able to interview five of the 12 “crucial” MPs: Dalila Babba, Meherzia Laabidi, Mohamed Zrig, Walid Bennani, and Osama al-Saghir. In addition, to round out the research, I interviewed 6 MPs who had been in prison, including Mohamed Saidi, Sadok Chourou, Habib Ellouze, Sahbi Atig, Habib Khedher, and Badreddine Abdelkafi. Finally, I also interviewed 10 other prominent Ennahda leaders, including Ennahda president Rached Ghannouchi, former prime ministers Ali Laarayedh and Hamadi Jebali, former ministers Samir Dilou and Rafik Abdessalem, MP and former governor Mohamed Sidhom, political bureau president Noureddine Arbaoui, and Shura Council members Mohamed Akrout, Said Ferjani, and Abdelhamid Jelassi (for details on each interview, see supplementary materials).

These interviews suggest that there were a number of mechanisms by which living in secular democracies produced greater secularism. For some, like Ennahda MP Dalila Babba, who was exiled in France for 20 years, it was intergroup contact that was key:

There was a big difference between those of us who experienced twenty years in the West and the others who lived here [in Tunisia]. The whole world and all of its freedoms were opened to us. We met with other people and the other world! […] For instance, I was involved in religious dialogues in an Islamic Center in Grenoble. Next to us was a Jewish synagogue - our buildings shared a wall! We often had dialogues with Christians, Jews, and Muslims where we interacted, discussed, and came together at the end to realize that all religions have the same core values and are having the same internal conflicts with extremists.Footnote 41

For Babba, therefore, it was dialog with others that bred empathy and understanding toward non-Muslims. For others, it was taking the perspective of a minority. Ennahda MP Sayida Ounissi, who spent 18 years in France, explained:

Growing up in a very secular country when you are a Muslim […] pushes you to think about diversity, about the place of minorities. Probably this is why Ennahda is the most [likely] to think about minorities in Tunisia. […] It was an important moment for us as a political family to be there, in Paris, London, Germany, or Italy. I don’t know if it is determinative of what we are doing now. But it definitely helped us to have this sense that diversity is important and you should listen to the other. And that what the other is doing or saying or believing in is not automatically something bad. We were living in societies where not everyone was thinking or living like us or having the same religion. It definitely had a very positive impact.Footnote 42

These accounts corroborate one mechanism by which living in secular democracies contributes to moderation: interactions with members of other religions. This intergroup contact may push Islamists to become more accepting of religious freedom, and more likely to abandon goals of enshrining Islamic law in the constitution. Yet, there were also other advantages to living in the West beyond these interactions. For Ennahda MP (and Vice President of the NCA) Meherzia Laabidi, who also spent two decades in France, it was their first taste of democracy, socializing them into accepting these norms:

[Ennahda MPs who only lived in Tunisia] will never appreciate it [freedom] like we do because we tasted it. We actually experienced citizenship, experienced democracy, experienced living together with others. We realized the intrinsic and inherent value of these concepts.Footnote 43

Having fled repression in Tunisia, Laabidi saw her personal situation improve, “tasting” freedom and realizing the intrinsic value of this concept. Corroborating Careja and Emmenegger (Reference Careja and Emmenegger2012) and Chauvet, Gubert, and Mesple-Somps (Reference Chauvet, Gubert and Mesple-Somps2016), this personal improvement appears to have increased the socialization effect of living abroad.

Beyond intergroup contact and socialization, a third possible effect of living in the West was political learning: revising Islamists’ interpretations of what secularism can mean. Living in secular democracies—at least other than France—may have taught Islamists that the separation of religion and the state does not mean the repression of Islamists like it had under previous Tunisian autocrats, but rather ensures that Islamists also have a voice. In the foremost biography of Ennahda head Rached Ghannouchi, Tamimi (Reference Tamimi2001) writes that “initially, his critique was radical; it rejected almost everything that came from the West” (p. 35). Ghannouchi rejected Bourguibism, the secular ideology of Tunisia’s first autocrat Habib Bourguiba, “in its totality and could only see its negative aspects” (p. 45).Footnote 44 Yet after living in London for two decades, Ghannouchi realized that “North African secular elites have not pursued the model of their Western inspirers. [… Instead of] the state and religion being separate, […in Tunisia] the state […] monopolizes religion” (p. 113). Ghannouchi now maintains that as practiced in the West, “secularism is not only justifiable but has had positive aspects” (p. 113).

The effect of living in the West on secularism appears to hold even out of sample. Imed Daimi, CPR Secretary-General and President Moncef Marzouki’s Chief-of-Staff, observed that his personal transition from Islamism to secularism, and accordingly his decision to join CPR instead of Ennahda, stemmed from his experience living in France:

Living inside the Arab, Islamic society, we don’t see many differences. The majority of the people think in one way. When I left [Tunisia] and met others [in France], my ideas changed. I preserved my [Muslim] identity of course, but in daily interactions especially with the [French] government, I realized that as a minister, for instance, you must deal with all people. I was affected a lot by its democratic culture and pluralism.Footnote 45

In sum, Ennahda MPs recognize that their time in secular democracies has had a causal impact on their beliefs, and provide support for each of the three hypothesized mechanisms for this effect. In the case of Tunisia, therefore, we see strong evidence of the secular diffusion hypothesis.

CONCLUSION

Leveraging unique voting data and interviews with Islamist parliamentarians in Tunisia, this article contends that one neglected pathway to Islamist moderation may be migration to secular democracies. Through a variety of mechanisms—socialization, intergroup contact, and political learning—an acceptance of secularism may diffuse to Islamists living in secular democracies. As a result, on their return to their home countries, they may be significantly more secular-minded than their counterparts who had not gone abroad. At least in the case of Tunisia’s Ennahda, these Islamists who had lived in secular democracies were the driving force pushing Ennahda to move from an Islamist political party insistent on enshrining Islam in the constitution to Muslim Democrats not only willing but also committed to secular democracy.

Although beyond the scope of this article, Appendix E takes a first stab at testing whether this theory travels beyond the case of Tunisia. Using region-wide survey data from the Arab Barometer, it finds that Islamists who had spent time in the West espoused significantly more secular beliefs than Islamists who had not. These results hold when matching Islamists who had traveled abroad with Islamists who had not on a variety of demographic covariates. Although this test is of course conducted on supporters of Islamist parties, rather than party elites themselves, these results provide at least initial support that the theory may have external validity.

These results highlight a new pathway of Islamist moderation: migration to secular democracies. Two dominant explanations in the literature—interactions with other political parties and repression—appeared to have little impact on whether Ennahda MPs voted for secularism, as least using the proxies herein.Footnote 46 Moreover, the results suggest that the psychological and ideological impacts of living in the West appear to affect Islamist MPs’ voting behavior even when taking into account a number of political incentives, such as appealing to their constituency’s median voter. Of course, it may simply be that these parliamentarians had not yet fully grasped these political incentives just two or three years into democracy. The relative weight of these political interests with each parliamentarian’s past experiences may very well change as parliamentarians get conditioned to playing the political game. But at least in the early stages of a democratic transition, Islamists’ personal experiences may matter as much as their political context in determining their behavior in power.

Beyond their contribution to Islamist moderation, these findings are also important to explaining the Arab Spring’s one successful democratic transition: Tunisia. Although much has been made of Ennahda’s important compromises in the transition, this article sheds light on who within Ennahda supported the major concessions regarding religion and the state. Contrary to existing explanations, it suggests that it was not the wing of Ennahda that was imprisoned but rather the wing of Ennahda that had been in exile that played the pivotal role in compromising with secularists and thereby rescuing the transition at critical moments in the bumpy road to democracy.

These findings may also have implications for one of the Arab Spring’s failed democratic transitions: Egypt. As a result of the July 2013 coup, members of the Muslim Brotherhood have similarly found themselves in prison, underground, or in exile, largely in Istanbul with others scattered in the West. If and when the Brotherhood returns to political life in Egypt, these diverse experiences are likely to have lasting impacts on each individual’s political preferences. These findings would suggest that those members of the Muslim Brotherhood who have found refuge in Western capitals are likely to be most secular-minded on their return to Egypt.

Finally, these findings have important policy implications. They would suggest that opportunities for Islamists to study or find refuge in the West are critical components of the West’s democracy promotion efforts. At a time when scholarships and exchanges for Muslim students are being cut and borders are being closed, these results provide important evidence that exposure to the West may help to moderate Islamists into accepting secular democracy. Although the shock of liberal Western morals occasionally produces greater conservatism, these results suggest that on average, the effect is toward secularism. Of course, it is also crucial to acknowledge that how Islamists are treated in the West is as important as allowing them entry. Socialization effects are strongest where an immigrant’s personal situation has improved in the destination country. If Islamists are instead harassed, spied upon, and repressed in secular democracies, as has increasingly occurred post-9/11, they are unlikely to view secular democracy in a positive light.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000819.

Replication materials can be found on Dataverse: at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VWBTL5.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.