Introduction

Self-regulation (SR) refers to the processes that modulate one's reactivity, including either facilitating (e.g., approach) or inhibiting (e.g., withdraw) one's arousal and emotional responses (Rothbart, Bates, Damon, & Lerner, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon and Lerner2006). Over the past few decades, researchers have documented that SR is a key predictor of children's later adaptive and maladaptive functioning (Rothbart, Ahadi, & Evans, Reference Rothbart, Ahadi and Evans2000). For instance, empirical research has identified that children with a greater SR capacity early in life tend to have higher academic achievement, better interpersonal relationships, and are at lower risk for physical and mental disorders (for a review, see Rothbart, Bates, Damon, & Lerner, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon and Lerner2006 ). Recognizing the importance of SR across development, there has been increased research efforts focused on understanding its early development and identifying sources that predict child SR, in order to effectively prevent problematic SR development.

Models of SR typically consider regulation as a dual process. These models distinguish the automatic (reactivity) versus deliberate processes (SR) of regulation, with the former usually being the target of the latter (Nigg, Reference Nigg2017). More specifically, reactivity concerns one's automatic responses to external and internal stimuli changes and is thought to be related to individual differences that are present at birth, thus in part reflecting a relatively stable characteristic of the child (Rothbart, Reference Rothbart, Kohnstamm, Bates and Rothbart1989a, Reference Rothbart, Kohnstamm, Bates and Rothbart1989b; Rothbart & Derryberry, Reference Rothbart, Derryberry, Lamb and Brown1981). In contrast to this automatic process, regulation involves children's deliberate modulation of their reactivity, reflecting in children's ability to voluntarily sustain focus on a task, shift attention from one task to another, initiate action, and inhibit action (Rothbart & Derryberry, Reference Rothbart, Derryberry, Lamb and Brown1981).

The development of SR

The development of SR is thought to follow a nonlinear pattern of growth throughout early childhood, congruent with the early development of some physical and neural systems (Nigg, Reference Nigg2017). Young infants exhibit very little regulatory control (Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart1998), with their early regulation mainly relying on basic orienting capacities that provide a physiological basis for children's ability to modulate attentional activities within sensory-specific areas (Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart2000; Rothbart, Posner, & Kieras, Reference Rothbart, Posner, Kieras, McCartney and Phillips2006). Behaviorally, these orienting capacities have been measured as infants’ sustained attention to and/or interaction with a single object (Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003; Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith1996; Rothbart, Reference Rothbart1981). Both empirical and psychometric studies have shown that orienting capacity assessed during infancy is closely associated with later active and voluntary regulation capacities (Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, Lance, Iddins, Waits and Lee2011; Casalin, Luyten, Vliegen, & Meurs, Reference Casalin, Luyten, Vliegen and Meurs2012; Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith1996; Putnam, Rothbart, & Gartstein, Reference Putnam, Rothbart and Gartstein2008). However, the degree to which infants’ early orienting capacity can maintain their own emotional and behavioral homeostasis is limited. As such, measures of early SR typically also incorporate an extrinsic regulatory aspect, such as soothability. Such extrinsic aspects of SR refers to infants’ ability to regulate when there is external regulation assistance being provided by a caregiver (e.g., picking up the infant, tactile stimulation, rhythmic movements; Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, Lance, Iddins, Waits and Lee2011; Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003; Rothbart, Reference Rothbart1981).

Subsequently, later in the first year of life, infants’ voluntary modulation of their reactivity improves rapidly, along with their physical and neurological maturation as well as the acquisition of new skills to deal effectively with their responses (Calkins & Fox, Reference Calkins and Fox2002). Across this important developmental period, especially toward the end of the first year of life, researchers have observed infants’ increased use of more mature regulation strategies (Calkins & Fox, Reference Calkins and Fox2002; Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009). Specifically, studying the development of regulatory behaviors in 66 infants from 3 to 13 months, Rothbart, Ziaie, and O'boyle (Reference Rothbart, Ziaie and O'boyle1992) found that infants’ use of regulatory strategies became increasingly complex, transitioning from early heavy reliance on orienting, to regulatory attempts involving multiple sensory modalities (e.g., tactile self-soothing, respiration), and also evolved from passive to more active approaches (e.g., body self-stimulation).

Although a general normative developmental pattern of SR has been described, there are also considerable individual differences within such patterns. Rothbart and Derryberry (Reference Rothbart, Derryberry, Lamb and Brown1981) characterized child SR as having a constitutional basis, indicating SR reflects a relatively enduring biologically based aspect of the individual, which is also influenced over time by heredity, maturation, and experience (Rothbart & Derryberry, Reference Rothbart, Derryberry, Lamb and Brown1981; Rothbart, Bates, Damon, & Lerner, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon and Lerner2006). Similarly, developmental physiological studies have suggested early SR development as an outcome of the increasingly focalized and refined neurological system, such as the executive attention network (Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart1998; Rothbart & Rueda, Reference Rothbart, Rueda, Mayr, Awh and Keele2005; Rueda, Posner, & Rothbart, Reference Rueda, Posner and Rothbart2005). In the meantime, such refinement may be altered on a temporary or more permanent basis depending on the environmental input received (Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart2000), especially during early years such as infancy.

Generally speaking, infancy is viewed as a period during which influences on development are particularly strong (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2014; Goodman, Reference Goodman and Calkins2015). With respect to SR specifically, Caspi et al. (Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig, Harrington and Poulton2003) pointed out the plasticity of SR during infancy and early toddlerhood, making this stage of development especially important for investigating environmental factors that may shape the development of young children's regulatory capacity. Kiff, Lengua, and Zalewski (Reference Kiff, Lengua and Zalewski2011) suggested that infancy and preschool years might be a “sensitive period” during which the development of children's regulatory capacity is especially influenced by environmental factors. However, just as this sensitivity allows children's SR to mature in response to their nurturing environmental inputs, vulnerability also arises as some environmental inputs can also harm such growth. One such potentially harmful environmental input is parental internalizing disorder.

Parental internalizing disorder and infant SR

Maternal depression is among the most well researched vulnerability factors for poor SR outcomes in offspring (for a review, see Goodman, Reference Goodman and Calkins2015; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011). Although most of these studies concern SR outcomes in middle childhood to adolescence, there is also evidence showing the impact of maternal depression on SR outcomes early in life. For instance, Feldman et al. (Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009) found that the 9-month-old infants of mothers currently diagnosed with major depressive disorder exhibited poorer regulatory behaviors when compared with those with mothers without a depressive disorder. Similarly, Conroy et al. (Reference Conroy, Pariante, Marks, Davies, Farrelly, Schacht and Moran2012) found that the presence of maternal depressive disorder measured at 2 months postpartum significantly predicted toddler dysregulation at 18 months.

Other studies have examined the association between the maternal history of depressive disorders (as distinct from current depressive disorder) and the development of SR in young children. These studies speculate that adverse infant outcomes may occur as a function of long-term disturbances in maternal behaviors that are associated with their vulnerability to depression, regardless of their current diagnosis of depression (Murray, Reference Murray1992). For instance, Feldman et al. (Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2008) investigated mothers’ history of childhood-onset depression and their young children's emotion regulation at age 4 years. Their results indicated that children with mothers who present with a history of childhood-onset depression exhibit poorer and less effective use of emotion regulation strategies, compared with those children with mothers without a history of childhood-onset depression. Similarly, another study compared the physiological responses of 3- to 5-year-olds following a disappointment task between children of parents with and without a history of depression and concluded parental history of depression was associated with poorer child physiological regulation (Forbes, Fox, Cohn, Galles, & Kovacs, Reference Forbes, Fox, Cohn, Galles and Kovacs2006).

Although the association of maternal depression and child SR has been relatively well studied, the impact of fathers’ depression has been largely overlooked until recently. Nevertheless, it is estimated that 2.3%–12% of fathers experience depression during the prenatal period, with 5.4%–13.6% of fathers experiencing depression in the postnatal period (for a review, see Top, Cetisli, Guclu, & Zengin, Reference Top, Cetisli, Guclu and Zengin2016). The non-negligible prevalence of paternal depression makes it critical to take into consideration the role of both maternal and paternal depression in the development of SR in their offspring. As early as in 1997, researchers have identified that paternal depression can have similar effects on child outcomes as maternal depression (Jacob & Johnson, Reference Jacob and Johnson1997). Recently, Gentile and Fusco (Reference Gentile and Fusco2017) reviewed 23 studies on paternal depression and concluded that paternal depression, just like maternal depression, is associated with an increased risk for a range of developmental, behavioral, and psychiatric problems in infants and toddlers.

More recent research has started to address the impact of maternal anxiety disorder on child SR outcomes. Studying mothers’ depression and/or anxiety during the second trimester of pregnancy, Warnock, Craig, Bakeman, Castral, and Mirlashari (Reference Warnock, Craig, Bakeman, Castral and Mirlashari2016) reported that infants of mothers with depression and/or anxiety were more likely to exhibit atypical SR behaviors. However, when comparing 9-month-old infants’ fear regulation between those with mothers with depression, anxiety, or neither, Feldman et al. (Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009) reported similar fear regulation between infants of mothers with anxiety and those with absence of psychopathology. Studying fathers’ anxiety and infants’ risk of anxiety, as operationalized by infants’ observed behaviors, such as latency of approach to new activities and time spent playing with the same object, Gibler, Kalomiris, and Kiel (Reference Gibler, Kalomiris and Kiel2018) reported that paternal anxiety was indirectly associated with infant anxiety.

Several gaps remain to be addressed in the current literature examining parental psychopathology and child SR. First, there are still relatively limited studies focusing on the infancy and early toddlerhood period of SR development, comparing with research studying middle- to late-childhood SR. Nevertheless, it has been argued that infants’ socio-emotional development, including regulatory capacity, appears most affected by parental depression in the first 2 years of life, as opposed to later years (Cohn & Campbell, Reference Cohn, Campbell, D and S1992; Lengua, Reference Lengua2006; Lengua, Honorado, & Bush, Reference Lengua, Honorado and Bush2007), especially considering that the toddlerhood years are an especially important period for infants to develop their internal and effortful mechanisms of SR (Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, Lance, Iddins, Waits and Lee2011). Therefore, studies that examine the influence of parental depression on SR development in the early years are especially warranted. Second, the majority of these studies focus on specific time points of child SR outcomes – studies concerning the developmental trajectory of SR in early years are scarce. One of the few studies to address this question was conducted by Bridgett et al. (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009), who examined the association between maternal factors and the development of infant temperament from 4 to 12 months. Their results indicated that maternal depression measured 4 months postnatally demonstrated a significant positive association with infants’ negative emotionality at 4 months, as well as nonsignificant trend association with a sharper increase of negative emotionality from 4 to 12 months. Further research studies addressing this question are therefore needed to inform not only the long-term effects of maternal depression on child SR development, but also how early risk factors, such as parental internalizing disorders, contribute to patterns of changes of SR over time, which in turn offers important clinical implication for prevention and intervention. The current study addresses this need by examining the association between parental lifetime and current internalizing psychopathology and the developmental trajectory of SR measured across multiple waves of assessment during the early years.

Further, building upon the literature reviewed above, the current study also aims to expand the scope from parental depressive and anxiety disorder to internalizing disorders that are characterized by affective dysregulation (Krueger, McGue, & Iacono, Reference Krueger, McGue and Iacono2001). We use this conceptualization of parental psychopathology for several reasons. First, the lack of ability to regulate distressing emotions through mental processes is a shared characteristic among several common mental disorders, including but not limited to depressive and anxiety disorders (Taylor, Bagby, & Parker, Reference Taylor, Bagby and Parker1999). Second, developmental psychopathology researchers have long suggested that it is the characteristic of caregivers’ dysregulated emotions as a result of their psychopathology that leads to offspring's SR difficulties, rather than the disorders per se. For instance, examining different presentations of maternal depression, Cohn and Tronick (Reference Cohn and Tronick1989) observed that infants respond differently to subtypes of depression, with infant behavioral dysregulation being the most evident among infants of mothers whose depression is primarily manifested by withdrawn emotions, a clinical manifestation of difficulties regulating affect. The researchers subsequently concluded that infants are sensitive to maternal affect, and that therefore the quality of mothers’ affective regulation may be a more critical factor than the mothers’ diagnostic status on their offspring's regulatory capacity. Third, there is a high comorbidity rate among disorders of affective dysregulation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and this high overlap among disorders of affective dysregulation (frequently labeled as internalizing disorders, Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, McGue and Iacono2001) makes it challenging to investigate the contribution of each psychiatric disorder separately. Last but not least, reviewing studies from multiple disciplines spanning over 75 years on the intergenerational transmission of SR, Bridgett, Burt, Edwards, and Deater-Deckard (Reference Bridgett, Burt, Edwards and Deater-Deckard2015) concluded that there is a positive association between parent and child regulatory capacity. For instance, van den Bergh et al. (Reference van den Bergh, van den Heuvel, Lahti, Braeken, de Rooij, Entringer and Schwab2017) found that mothers’ stress dysregulation was significantly correlated with aberrations in a number of infant neurological indicators of regulatory capacity. However, when examining mothers' effortful control at 4 months postnatal and infants' orienting/regulation developmental trajectory from 4 to 12 months, researchers only found a significant positive association between mothers' effortful control and the intercept of infant orienting/regulation development, but unexpectedly, not the slope (Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, Lance, Iddins, Waits and Lee2011). Given that this study was one of the few studies examining the predictors of the developmental trajectory of child regulation, further work in this line of inquiry is greatly needed.

Moderating role of positive parenting

Despite the evidence of the negative impact of parental internalizing disorder on child SR, protective factors have also been identified. Studies of children being exposed to early adversity, including parental depression, have consistently concluded that positive parental behavior is among the most robust protective factors against negative developmental outcomes (Luthar, Crossman, & Small, Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lamb and Garcia Coll2015; Masten & Barnes, Reference Masten and Barnes2018). Positive parental behavior may be especially critical when child SR is concerned, given that the development of regulatory capacity is closely tied to actions and responses of caregivers (Rothbart, Reference Rothbart, Kohnstamm, Bates and Rothbart1989b). To be more specific, infants have limited SR capacity, which is often insufficient for maintaining their own emotional homeostasis. Therefore, to compensate for this relative lack of self-regulatory capacity, caregivers usually provide external controls on the infants’ behaviors and are sensitive to infants’ distress reactions, which subsequently guide their soothing responses (Rothbart, Reference Rothbart, Kohnstamm, Bates and Rothbart1989b). Beyond the first year of life, infants recognize and start utilizing their caregivers as external sources of regulation and actively participating in coregulatory dyadic processes (Lunkenheimer, Kemp, Lucas-Thompson, Cole, & Albrecht, Reference Lunkenheimer, Kemp, Lucas-Thompson, Cole and Albrecht2017; Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart and Bates1998), marking the continued importance of parents’ sensitivity and warmth towards meeting infants’ regulatory needs. As initially proposed by Kopp (Reference Kopp1982) and corroborated by subsequent studies (Grolnick & Farkas, Reference Grolnick and Farkas2002; Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Dekovic, Reference Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken and Dekovic2008; Masten & Monn, Reference Masten and Monn2015; Tronick & Beeghly, Reference Tronick and Beeghly2011), it is this parent–child coregulatory process that ensures young children's successful transition from external to internal regulation, hence children's self-regulation of emotions and behaviors. Furthermore, a recent study examined the longitudinal development of child executive function, a related construct to SR, and reported that higher quality in parenting predicts a more developmental gain in executive function from 36 to 60 months (Blair, Raver, & Berry, Reference Blair, Raver and Berry2014).

Several studies have also reported the role of positive parental behaviors in buffering against the negative child SR outcomes from parental internalizing disorders. For example, Kaplan, Evans, and Monk (Reference Kaplan, Evans and Monk2008) examined the biobehavioral aspect of SR in 4-month-old infants. Their results indicated that maternal sensitivity significantly buffers the effect of mothers’ mood disorder on the physiological measure of infant SR. Similarly, Thomas, Letourneau, Campbell, Tomfohr-Madsen, & Giesbrecht (2017) of the APrON Study Team reported that maternal sensitivity moderates the effect between mothers’ prenatal internalizing disorder and poor attentional regulatory capacity at 6 months postnatal.

Emerging studies have also reported the effect of fathers’ parental behaviors on infant SR outcomes (for a review, see Stgeorge & Freeman, Reference Stgeorge and Freeman2017) and concluded that fathers can be “just as developmentally supportive as are mothers” (Cabrera & Roggman, Reference Cabrera and Roggman2017, p. 706). For example, Gallegos, Murphy, Benner, Jacobvitz, and Hazen (Reference Gallegos, Murphy, Benner, Jacobvitz and Hazen2017) reported that fathers’ emotional withdrawal during father–infant play at 8 months postnatal significantly predicted worse infant emotion regulation at 24 months. In another study, van Prooijen, Hutteman, Mulder, van Aken, and Laceulle (Reference van Prooijen, Hutteman, Mulder, van Aken and Laceulle2018) reported a moderate positive association between fathers’ emotional availability and the self-control of 2-year-olds However, studies testing the buffering effect of paternal behaviors by directly examining the link between paternal internalizing disorders and infant SR outcomes are still lacking. In addition, similar to other studies on infant SR, the above-reviewed studies mainly utilized cross-sectional research design. Studies are also needed concerning the developmental process (i.e., trajectory) of infant SR.

The current study

The current study investigated the effect of maternal and paternal lifetime and current internalizing disorder on the developmental trajectory of infant SR, and the potential moderating role of positive parental behaviors on these associations. Rather than adopting the traditional psychopathology taxonomies, the current study operationalized parental psychopathology by using the definition of internalizing disorder proposed by the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP; Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby and Eaton2017) model, which allows a better representation of the shared component of affective dysregulation across multiple traditional diagnostic categories. The HiTOP model follows a quantitative psychiatric classification that operates on two levels: first, it constructs syndromes from the empirical covariations of symptoms; and second, it groups syndromes into spectra based on the covariation among them. In the current study, we operationalized internalizing disorders as representing disorders of affective dysregulation and incorporating disorders on the HiTOP internalizing spectra. These disorders share the characteristics of distress (consists of major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), fear (panic disorder, phobic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, separation disorder), and eating pathologyFootnote 1 (bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder). Of note, although there is emerging evidence that mania and bipolar disorders generally relate to internalizing disorders (e.g., Kotov, Perlman, Gámez, & Watson, Reference Kotov, Perlman, Gámez and Watson2015), whether the underlying components of mania belongs to internalizing spectra or thought disorder is still yet clear (Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby and Eaton2017). Therefore, to better focus on the internalized affective dysregulation characteristics of mental disorders, bipolar disorders were excluded from the internalizing disorder code in the current study.

Taken together, we proposed three research questions and corresponding hypotheses. First, utilizing a latent growth approach, we aimed to identify the developmental trajectory of infant SR from 3 to 24 months. Building upon previous theories and studies (e.g., Planalp & Braungart-Rieker, Reference Planalp and Braungart-Rieker2015; Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart1998), we expected to observe an overall increasing trend of infant SR capacity. Second, the current study addressed the impact of maternal and paternal lifetime and current internalizing disorder on the developmental trajectory of infant SR. We hypothesized that both mothers’ and fathers’ lifetime and current internalizing disorder would be associated with poorer infant SR at the initial assessment point (i.e., 3 months), similar to that being reported in the literature (e.g., Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, Lance, Iddins, Waits and Lee2011). Although there are few prior studies investigating the association between parental psychopathology and trajectories of SR development, based on Bridgett et al.'s (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009) findings, we predicted a negative association between parents’ lifetime and current internalizing disorder and the slope of SR development. Third and finally, we examined whether positive parental (maternal and paternal) behaviors moderated the associations identified in the previous research question. We expected to find a protective role of positive parental behaviors, such that both maternal and paternal positive parental behaviors would buffer the negative effects of parental internalizing disorder on the developmental trajectory of infant SR.

Method

Participants

The current study utilized data from the Infant Development Study (IDS). The IDS was a follow-up project from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP). As part of the OADP, the initial pool of participants was a representative community sample of 1709 adolescents (ages 14–18 years at initial assessment) recruited from nine senior high schools in urban and rural districts of Western Oregon. They participated in three assessments from 1987 to 1999. Detailed descriptions of recruitment, sampling, and participation rates at each OADP assessment was reported in Lewinsohn, Rohde, and Seeley (Reference Lewinsohn, Rohde and Seeley1993).

At the Time 3 (T3) assessment point of the OADP, when participants reached approximately 24 years of age, those who had a newborn infant or who became pregnant (n = 122) or whose partner became pregnant (n = 79) over a 3-year recruitment period, and who lived in Oregon and wished to participate, were recruited into the IDS. The participation rate for eligible families was 83%. Those who chose to participate in the IDS were less likely to have obtained a bachelor's degree or higher when compared with the full sample of OADP T3 participants (17% vs. 33%; χ2 (1, n = 930) = 12.8, p < .001). Differences in the IDS participation as a function of other demographic variables at T3 were nonsignificant, and demographic differences between those who did and did not participate were negligible.

At the first IDS assessment, a total of 166 mothers, 152 fathers, and 166 infants participated. Mothers were mainly White (87.5%), the average age was 28.04 years (SD = 2.43), and 41.0% had received at least a 2-year college degree. Fathers were mainly White (88.6%), the average age was 29.7 years (SD = 3.2), and 36.4% had received at least a 2-year college degree. There were roughly equal numbers of male and female offspring (male = 80, female = 86). IDS families brought their children in at ages 3 (Wave 1), 6 (Wave 2), 12 (Wave 3), and 24 months (Wave 4) for questionnaires, diagnostic interviews, and laboratory assessments. Attrition across the four assessment periods was minimal; at Wave 4, 162 (97.6%) mothers, 147 (96.7%) fathers, and 162 (97.6%) children participated. Families participating in the IDS were the focus of the current study.

Measures

Procedure

For IDS assessments, all parts of the assessments (direct assessment, diagnostic interview, observation, and questionnaires) were completed within 1 week before and 1 week after the infant turned the designated age. If necessary, the window of time was stretched to 2 weeks before and after, but only when 1 week was not an option. If the infant was born 3 weeks (21 days) or more before the due date (n = 11, range = 23–90 days, mean = 31.17, SD = 4.90), the due date was used to determine the dates of the assessments.Footnote 2

Assessment of parental psychopathology

At Wave 1 (3 months postpartum), lifetime psychopathology in both mothers and fathers were assessed with direct in-person interviews, utilizing the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM)-IV Disorders – Patient Edition (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1994). The SCID is a widely used semi-structured clinical interview that yields DSM-IV diagnoses for most Axis I disorders. An extensive, multisite, test–retest reliability study indicated that most diagnoses can be derived with adequate reliability (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Gibbon, First, Spitzer, Davies, Borus and Wittchen1992).

Personnel administering the SCID diagnostic interviews were carefully selected and trained. The interviewers generally had master's degrees in a mental health field and received extensive training. Prior to conducting interviews, all interviewers were required to demonstrate a minimum k of .80 for all symptoms across two consecutive interviews and on one videotaped interview of a participant with evidence of psychopathology. Based on a randomly selected subsample (25%), interrater reliability was moderate to excellent: Major depressive disorder (k = .71), anxiety disorders (k = .69), alcohol abuse/dependence (k = .86), and drug abuse/dependence (k = .85). Diagnoses were made using DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria.

Parents’ diagnostic data was then recoded in the forms of dichotomous dummy codes with 0 representing an absence and 1 representing the presence of lifetime psychopathology. As reviewed above, recoding of psychopathology follows the theoretical rationale of the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology model (HiTOP; Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby and Eaton2017). From the HiTOP model, the internalizing spectra was coded and utilized in all following analyses. The internalizing spectra (hereinafter internalizing disorder) shares the characteristics of distress (consists of major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), fear (panic disorder, phobic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, separation disorder), and eating pathology (bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder). The coding of lifetime psychopathology was aggregated into one code of lifetime internalizing disorder, with 0 representing an absence and 1 representing the presence of any of the disorders on the internalizing spectra.

Assessment of self-regulation

Infant behavior questionnaire

The Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ; Rothbart, Reference Rothbart1981, Reference Rothbart1986) is an 87-item, structured parental report questionnaire that has been demonstrated to possess good scale internal consistency and convergent validity with home observations of infant temperament. Mothers and fathers provided separate responses on IBQ regarding their infants’ temperament at Waves 1, 2, and 3 (i.e., 3, 6, and 12 months postpartum). Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) is .77 in the current sample.

The IBQ consists of six subscales: activity level, distress to limitation, latency of approach to novel stimuli, duration of orienting, smiling and laughter, and soothability. Given a higher order scale of orienting/regulatory factor was not constructed until a later version of the IBQ (i.e., IBQ-R, Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003), a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted with the six subscales. The PCA revealed two overarching factors that together explained 51.53% of the variances. The factor that consists of duration of orienting, smiling and laughter, and soothability was utilized to represent child orienting/regulation, explaining 29.14% of the variances. The orienting/regulation score was then constructed by taking the mean of the corresponding scales.

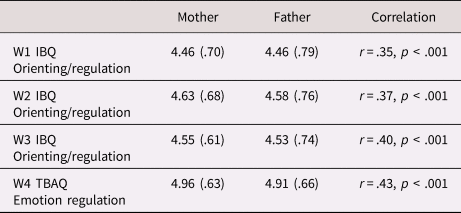

Each child's score for orienting/regulation was created by averaging mothers and fathers reporting on the corresponding IBQ scales. Table 1 summarizes mothers and fathers reporting on each scale, as well as the correlation between mothers and fathers ratings.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlation for mother and father IBQ and TBAQ scales

Descriptive statistics reported in Mean (SD).

IBQ = Infant Behavior Questionnaire; TBAQ = Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire.

Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire

The Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ; Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith1996) is a 108-item parent-report instrument designed to examine temperament-related behavior in 16- to 36-month-old children. The IBQ served as the model for the development of the TBAQ. Both parents completed the TBAQ at Wave 4 (24 months postpartum). Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) is .78 in the current sample.

To represent child regulation capacity, we selected the emotion regulation subscale from a revised eight-scale version of the TBAQ.Footnote 3 Following Goldsmith's (Reference Goldsmith1996) scale construction, the emotion regulation subscale was constructed by taking the mean of the corresponding items, if at least 50% of the scale items have valid responses, with a higher score indicating better regulatory capacity. Sample items included in the emotion regulation scale are: When you removed something your child shouldn't have been playing with, how often did he/she calm down within 5 minutes? Following an exciting event, how often did your child calm down quickly? When you are comforting your upset child, how often does he/she calm down quickly?

Similar to scores from the IBQ, each child's TBAQ regulation score was created by averaging mothers' and fathers' reporting on the corresponding TBAQ scales. Table 1 summarized mothers' and fathers' reporting on each scale, as well as the correlation between mothers' and fathers' ratings.

Parent–child interaction global rating

During parents’ and their infant's first visit to the laboratory (Wave 1), parental behaviors were coded during unstructured parent–child times by raters blind to parental diagnoses. Mother–child behavior and father–child behavior were coded independently. Coding systems were based on those used by Dr Dawson's group (for descriptions, see Dawson, Grofer Klinger, Panagiotides, Spieker, & Frey, Reference Dawson, Grofer Klinger, Panagiotides, Spieker and Frey1992). These consisted of systems designed to assess several dimensions of parent–child behavior during parent–child interaction (Breznitz & Friedman, Reference Breznitz and Friedman1988; Eyberg & Robinson, Reference Eyberg and Robinson1983; Kochanska, Kuczynski, Radke-Yarrow, & Welsh, Reference Kochanska, Kuczynski, Radke-Yarrow and Welsh1987).

Coding of parental behaviors focused on the domains of positive affect and affection, negative affect and negative verbalizations, involvement/engagement, and intrusiveness. Each behavior is coded on a 5-point Likert scale that indicates frequency of the corresponding behavior during interaction. For example, for the aspect of sensitivity, the code of 1 is defined as “Very insensitive. Parent always or almost always fails to respond appropriately and promptly, though occasionally may show the capacity for sensitivity, especially when the infant's affect and activity are not too discrepant with her/his own or when the infant displays great distress. An otherwise appropriate response may be delayed to the point that it is no longer contingent upon the infant's behavior or is discontinued prematurely. The parent's behavior may appear perfunctory, half-hearted, or impatient.” The code of 5 is defined as “Very sensitive. Parent always or almost always responds to the infant promptly and appropriately. She/he is never seriously out of tune with the infant's state, affect, tempo, or signals.”

Videotapes of parents and infants were coded by observers trained to a minimum reliability of κ = .70 and 80% agreement. To eliminate a potential source of bias in coding, the same coder was never assigned to code both parents in a family at the same infant age. Intercoder agreement for affect coding was computed by assigning 20% of videos to more than one coder. Intercoder agreement for parental behaviors during play was κ = .84. Please see Forbes, Cohn, Allen, and Lewinsohn (Reference Forbes, Cohn, Allen and Lewinsohn2004) for more detailed information and description regarding the parent–child interaction global rating and the coding procedure.

In the current study, the following behavioral codes were utilized to represent positive aspects of parental behaviors during parent–child interaction: positive affect (the expressions of positive regards by the parent, including positive affect and/or content of vocalization), sensitivity (parent's ability to perceive and accurately interpret the infants’ signals and to respond to them appropriately and promptly), and warmth (the extent to which the parent expresses affection toward the infant in a pleasurable way). Mothers' and fathers' positive parental behavior measure was represented as latent constructs from these observed behavioral codings of positive affect, sensitivity, and warmth.

Analytical approach

To examine the growth trajectory of young children's regulation development across 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, a latent growth model was computed. The latent growth model was an approach to capture information about interindividual differences in intraindividual change over time (MacCallum & Austin, Reference MacCallum and Austin2000; Nesselroade, Reference Nesselroade, Collins and Horn1991). Model fit was assessed based on a number of model fit indices. Kline (Reference Kline2005) suggested the minimum reporting of the following model fit indices: the model chi-square, the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The model chi-square value is a traditional measure for evaluating overall model fit and assesses the magnitude of discrepancy between the observed covariance structure and the theoretical covariance structure (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1998, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). A nonsignificant difference (p > .05) indicates a good model fit (Kline, Reference Kline2005). The CFI is a revised form of the normed-fit index (NFI), which assesses the specified model by comparing the chi-square value of the model to the chi-square value of the null model, taking into consideration of sample size (Bentler & Bonett, Reference Bentler and Bonett1980; Byrne, Reference Byrne1998). The RMSEA indicates the extent to which the specified model with optimally chosen parameter estimates would fit the population covariance matrix (Byrne, Reference Byrne1998; Steiger, Reference Steiger1990). A general consensus established that CFI values greater than .95 and RMSEA values close to or below .06 indicate very good model fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Finally, the SRMR is the standardized square root of the difference between the residuals of the sample covariance matrix and the hypothesized covariance model (Kline, Reference Kline2005). The SRMR ranges from zero to 1.0 with good fitting models obtaining values less than .05 (Byrne, Reference Byrne1998). Once the best-fitting growth model for regulation development was identified, the latent growth parameters were saved and utilized as dependent variables for subsequent analyses.

For all subsequent main and moderation models, demographically relevant covariates – child gender, mother education level, father education level, and household income – were included in order to control for their possible associations with the primary study variables. Parents’ current internalizing disorder was also entered as a covariate in all models examining the effects of lifetime internalizing disorder. Main effect models with parents’ lifetime and current internalizing disorder and parental behaviors predicting regulation development growth parameters were run. Mothers' and fathers' positive parental behaviors were represented as latent constructs from the observed behavioral codings of positive affect, sensitivity, and warmth. A total number of two main effect models were run, one for lifetime internalizing disorder and one for current internalizing disorder. Each model included all growth parameters as dependent variables, demographic covariates as control variables, and the following as independent variables: mothers' lifetime or current internalizing disorder, fathers' lifetime or current internalizing disorder, mothers' parental positive behavior latent construct, and fathers' parental positive behavior latent construct.

Finally, moderation models examining the interaction between parents’ lifetime and current internalizing disorder and positive parental behaviors in predicting child regulation development were run. Interaction terms between internalizing disorder and positive parental behavior latent construct were created were defined using the XWITH command in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2015) and then included in the moderation models. A total number of two moderation models were run, one for lifetime internalizing disorder and one for current internalizing disorder. For the lifetime internalizing disorder model, the model included all growth parameters as dependent variables, demographic covariates and current internalizing disorder as control variables, and the following as independent variables: mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder, fathers' lifetime internalizing disorder, mothers' parental positive behavior latent construct, fathers' parental positive behavior latent construct, interaction between mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder and mothers' parental positive behavior, and interaction between fathers' lifetime internalizing disorder and fathers' parental positive behavior. The model for current internalizing disorder is similarly defined, substituting the lifetime internalizing disorder with current internalizing disorder.

Results

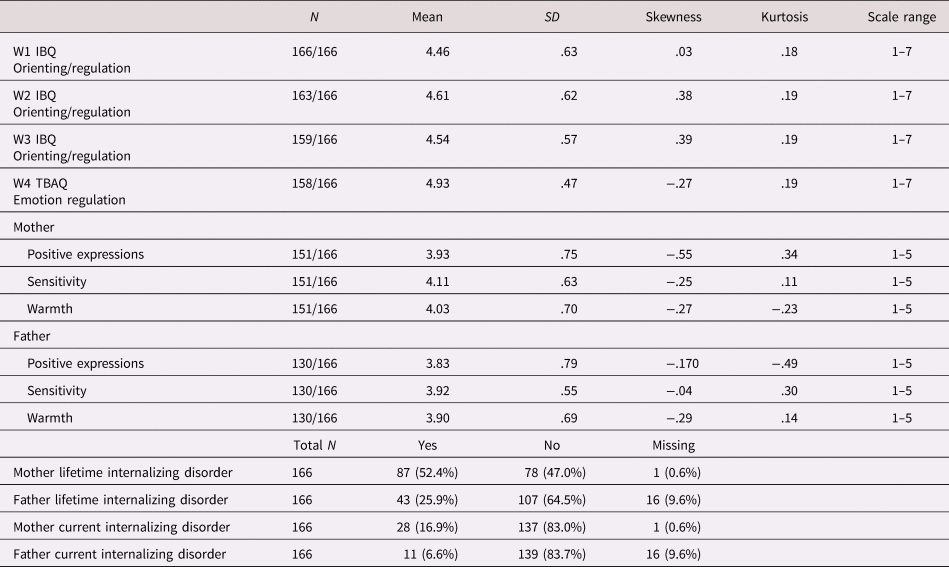

Descriptive statistics and missing data

Missing data analysis was performed in SPSS 24. All other analyses were performed in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2015). Descriptive statistics were presented in Table 2. All continuous variables were normally distributed without identifiable outliers. No data transformation was performed.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for child self-regulation measures, parental behaviors, and parent psychopathology.

IBQ = Infant Behavior Questionnaire; TBAQ = Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire

Missing data for key independent and dependent measures (i.e., mothers' and fathers' lifetime internalizing disorder, child regulation scores at Waves 1 through 4, and parental behaviors) were analyzed. Little's missing completely at random (MCAR) test (Little, Reference Little1988) was utilized to analyze missing data patterns for the key continuous measures (child regulation scores W1–W4 and parental behaviors) in the sample. MCAR test results revealed that, except for child regulation scores (χ2 (14) = 28.53, p = .01), all other variables were missing completely at random (χ2 (73) = 86.28, p = .14). Nevertheless, given that the rate of missingness for child regulation scores at Waves 1 through 4 were all less than 5% (Table 2), mean imputation was conducted (Tabachnick & Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2007).

For categorical variables (i.e., mothers' and fathers' lifetime and current internalizing disorder), a dummy code “missingness” for each variable was created, with participants with missing data coded as 0 and those with complete data as 1 (percentile missing reported in Table 1). Using the “missingness” variable as the grouping variable, independent sample t tests on child SR outcomes were then performed to examine the statistical differences between missing and complete data. The independent sample t test results revealed that there were no significant differences between the two groups of missing and complete for mothers' and fathers' internalizing disorder (ps > .05), indicating mothers' and fathers' lifetime and current internalizing disorder variables were missing completely at random.

As all key variables were missing completely at random or mean imputed, all variables were applied directly into subsequent analyses with the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation approach.

Intercorrelation

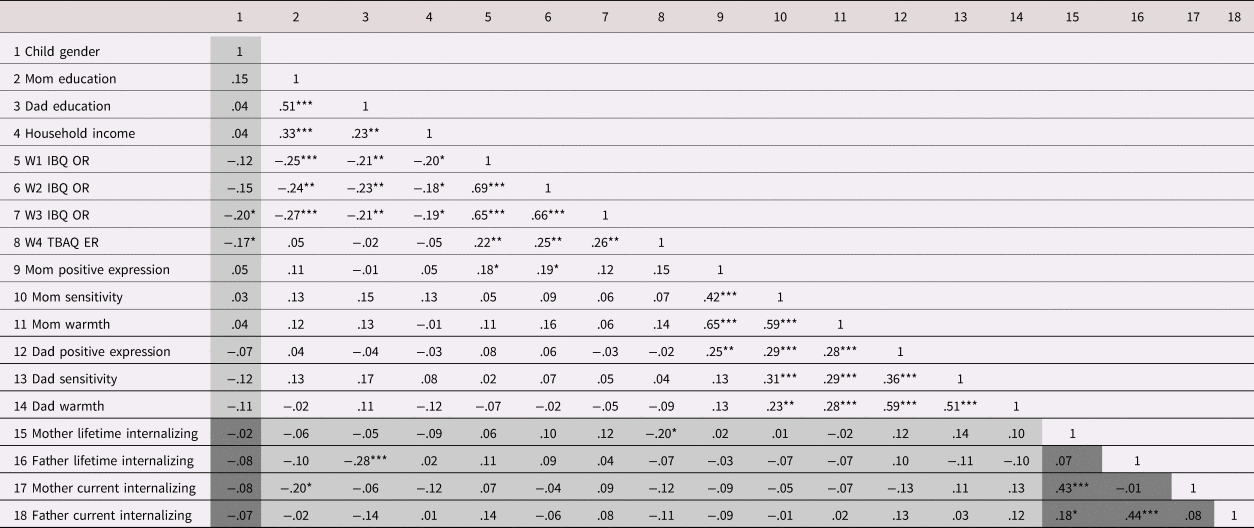

Intercorrelations were examined between control variables (child gender, mother and father education level, and household income), independent variables (parental behavior codes and parents’ lifetime and current internalizing disorder variable), and dependent variables (child regulation measures). Associations between dichotomous variables (child gender and parents’ internalizing disorder) and other continuous variables were run with univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results were presented in Table 3 as Pearson's correlation coefficient r, point-biserial correlation coefficient r, or phi f, as appropriate.

Table 3. Correlation among child self-regulation measures, parental behaviors, and parent psychopathology.

![]() Values presented in Pearson's r

Values presented in Pearson's r ![]() Values presented in point-biserial correlation r

Values presented in point-biserial correlation r ![]() Values presented in chi-square test phi f

Values presented in chi-square test phi f

IBQ = Infant Behavior Questionnaire; TBAQ = Toddler Behavioral Assessment Questionnaire; OR = orienting and regulation; ER = emotion regulation; W1 = Wave 1 at 3 months postnatal; W2 = Wave 2 at 6 months postnatal; W3 = Wave 3 at 12 months postnatal; W4 = Wave 4 at 24 months postnatal.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

As shown in Table 3, child regulation scores across the four assessment waves were significantly associated with each other (ps < .01), indicating a degree of longitudinal stability of the corresponding scales. Subsequent analyses therefore utilized the IBQ orienting/regulation and TBAQ emotion regulation scales as longitudinal representations for the construct of child regulation capacity.

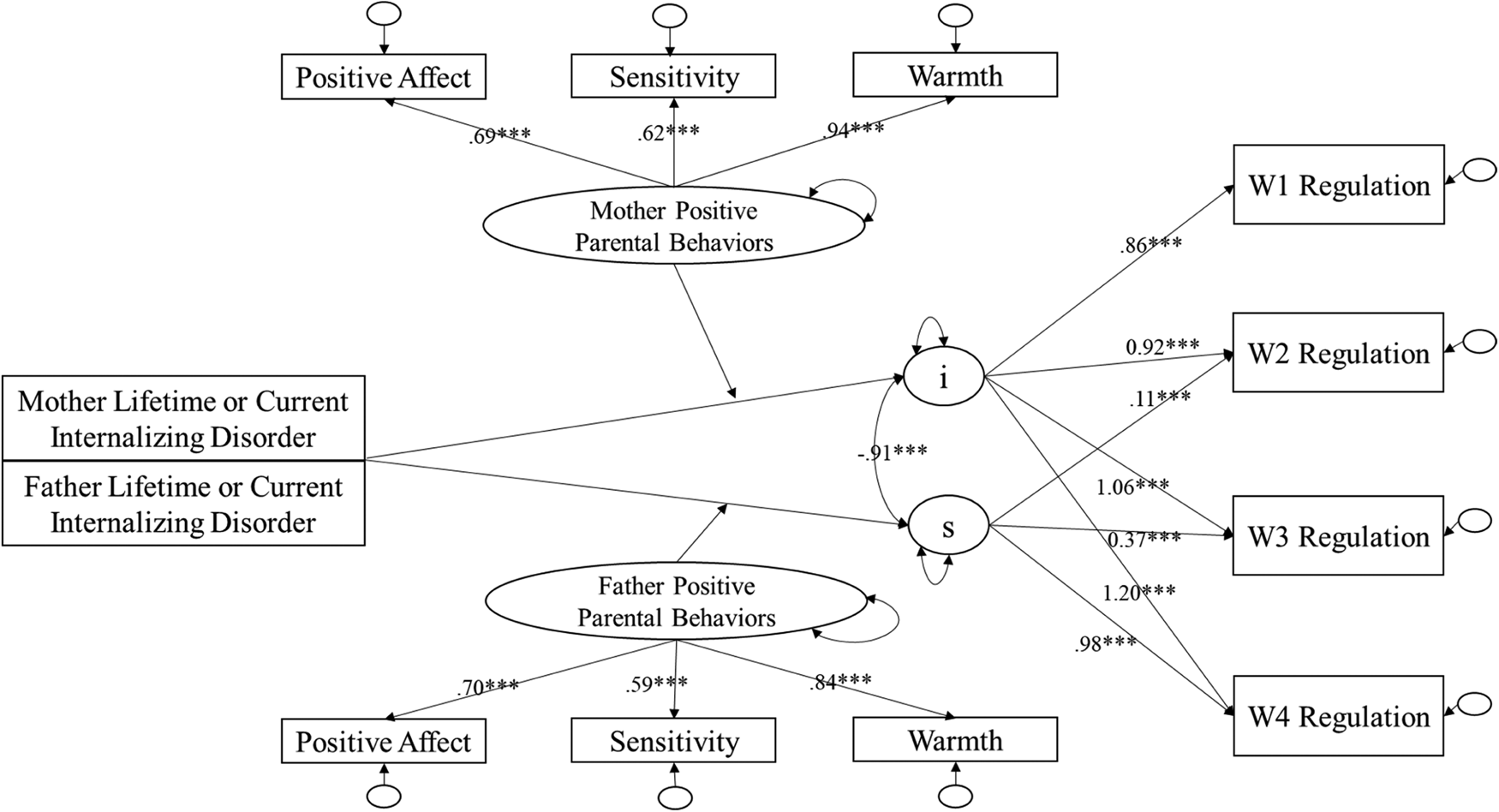

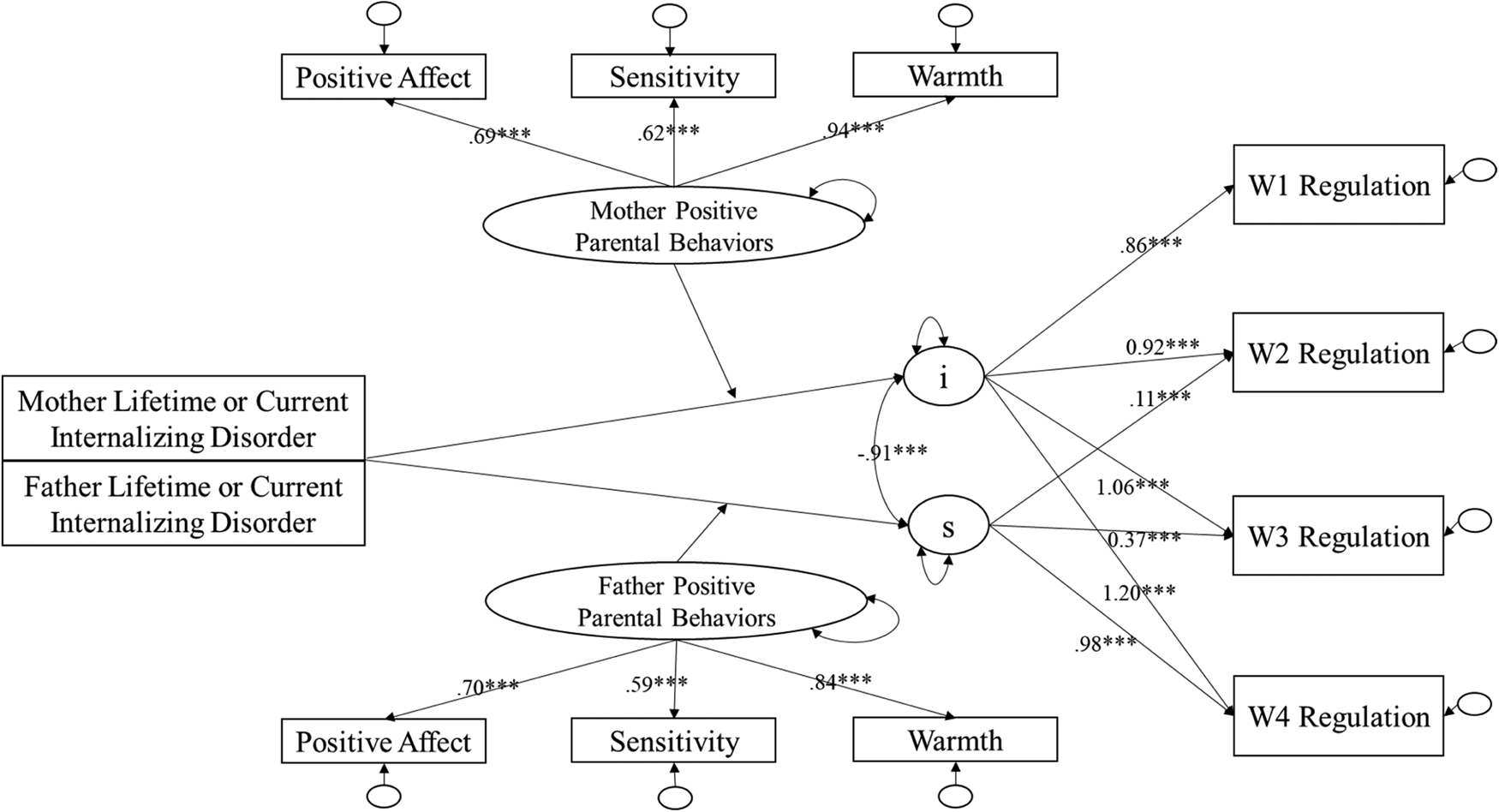

Unconditional latent growth model

An unconditional latent growth model was computed with children's regulation represented by the developmentally appropriate scales (i.e., the IBQ orienting/regulation factor at 3, 6, and 12 months and by the TBAQ emotion regulation scale at 24 months). By default, Mplus fixes the mean of observed measures (i.e., SR measures at W1 to W4) at 0. Mean SR at W1 and W3 were manually specified to be freely estimated to improve model fit. The unequal spacing between assessments were taken into consideration by specifying W1@0, W2@3, W3@9, and W4@21. The unconditional growth model specifying intercept and linear slope demonstrated the best model fit (χ2 (11) = 3.20, p = .36, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .06), comparing with the intercept-only model (Δχ2 (3) = 121.09, p < .001) and intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope (failed to converge). Results of this best-fitting model were shown as part of Figure 2 in the forms of standardized beta path coefficients. The unconditional growth curve for regulation measures are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Unconditional growth curve for child regulation development.

Figure 2. Moderation model: Maternal and paternal lifetime or current internalizing disorder and parental behaviors predict child self-regulation developmental trajectory.

Across the four assessment periods, the latent growth model results demonstrated an overall linear increase in children's regulation scores. The intercept of the growth curve was significantly different from zero (β = 4.55, p < .001) and showed significant variance (i.e., individual differences; β = .32, p < .001). Across the assessment period from Waves 1 to 4, the linear growth slope was also significantly different from zero (β = .02, p < .001) and showed significant variances (β = .001, p < .01). In addition, intercept significantly and negatively associated with slope (β = −.92, p < .001). Although appearing to be a high correlation coefficient, following Muthen's (Reference Muthen2007) suggestion in checking data normality, model assumptions, and model specifications, the correlation between intercept and linear slope was deemed credible. Of note, although centering the growth trajectory at different time points was proposed as an option, to stay consistent with the conceptualization and the current research question, the current study continued to define intercept at W1. From the latent growth model, the latent variables of intercept and linear slope were saved and entered as dependent variables representing children's regulation developmental trajectory in subsequent analyses, with the intercept being interpreted as child regulation at the initial assessment time point (hereinafter as regulation at 3 months), and linear slope as the growth rate of the trajectory (hereinafter as regulation growth rate).

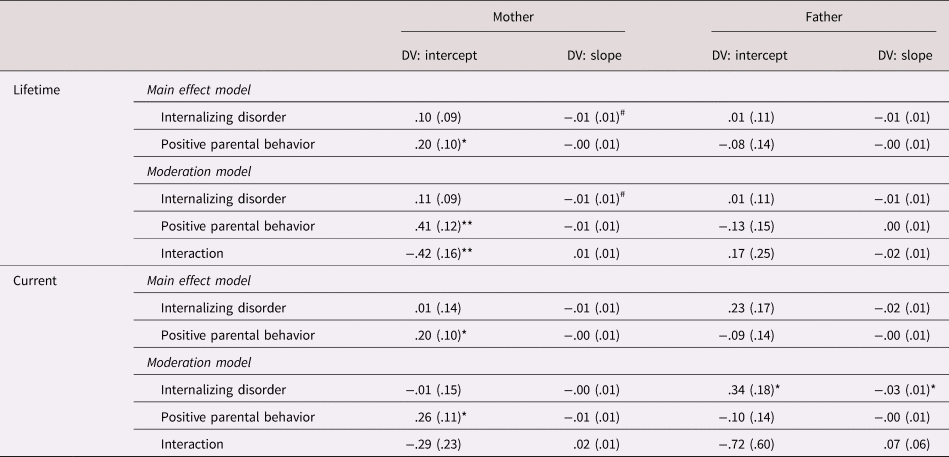

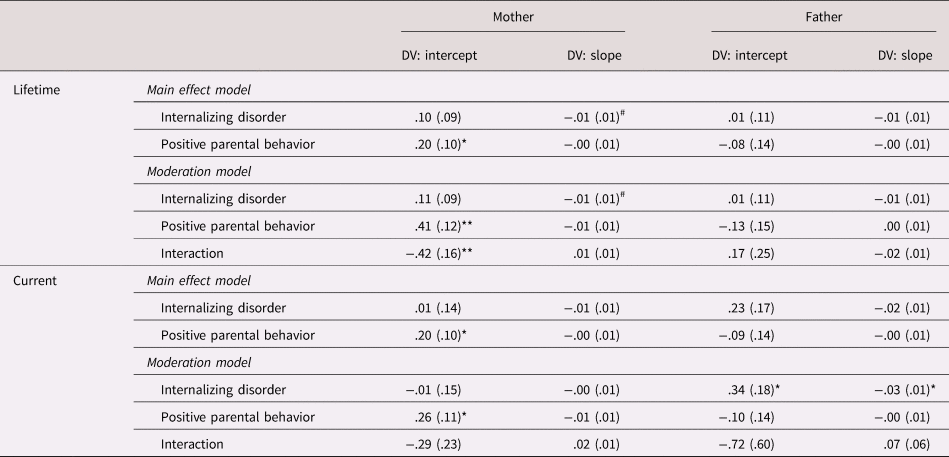

Main effect and moderation models – lifetime internalizing disorder

All main effect and moderation models included demographic covariates of child gender, mothers’ level of education, fathers’ level of education, household income, as well as the main effects of mothers’ and fathers’ current internalizing disorder.

As shown in the top block of Table 4, from the main effects model, none of the estimates on the paternal side reached statistical significance in terms of their association with SR growth parameters. On the maternal side, mothers' positive parental behavior was positively associated with the intercept of the developmental trajectory of child regulation (β = .20, p < .05). This main effect of mothers' positive parental behaviors was subsumed under the significant interaction between mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder and positive parental behaviors (β = −.42, p < .05), indicating a significant moderating effect of mothers' positive parental behaviors on the association between mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder and the intercept of the child's developmental trajectory of regulation.

Table 4. Main effect and moderation model: maternal and paternal internalizing disorder, parental behaviors, and child orienting and regulation development

Interaction = internalizing disorder × positive parental behaviors.

Demographic covariates (child gender, mother education, father education, and household income) included in all models; the lifetime internalizing disorder model also controlled for mothers’ and fathers’ current internalizing disorder.

Statistics reported in unstandardized regression coefficients with standard error shown in parenthesis.

**p < .01 *p < .05 #p < .10.

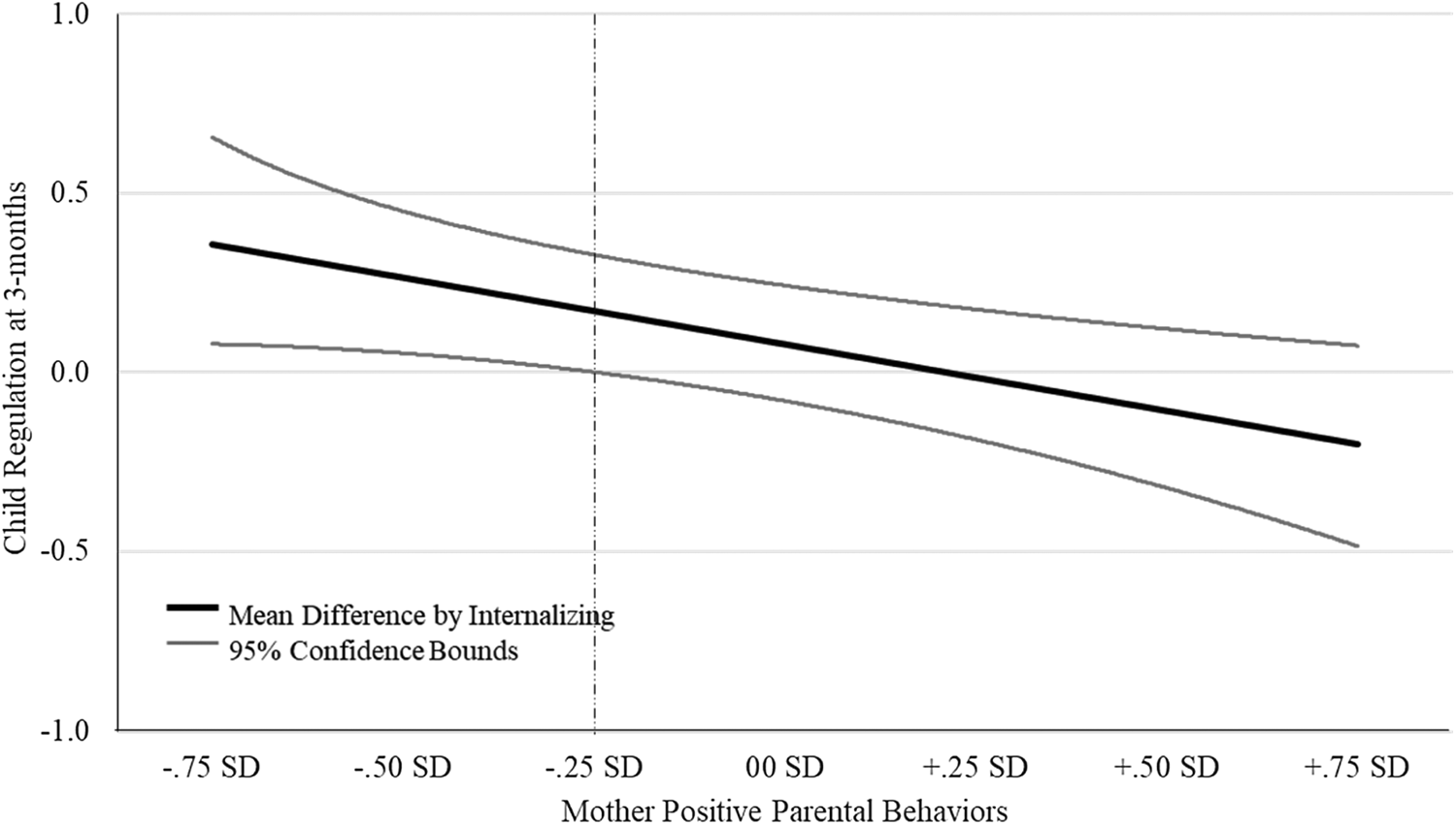

This interaction between mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder and mothers' positive parental behaviors in predicting child regulation intercept is plotted utilizing a mean difference approach (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, Reference Preacher, Curran and Bauer2006), taking into consideration of father's average positive parental and no lifetime internalizing disorder (i.e., father positive parenting = 0 and father internalizing disorder = 0) as well as child gender, mothers' and fathers' education level, household income, and mothers' and fathers' current internalizing disorder. As shown in Figure 3, the magnitude of influence is displayed representing mother's lifetime internalizing disorder has on the relationship between mothers' positive parental behaviors and child regulation at 3-months. The x-axis represents mothers' positive parental behaviors at varying levels, and y-axis represents the differences of regulation intercept between conditions of the presence and absence of mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder. A y-axis value above 0 (i.e., 95% CI above 0) indicates a statistical significance difference of child regulation intercept between mothers with and without lifetime internalizing disorder on the corresponding x-axis value (i.e., mothers' positive parental behavior).

Figure 3. Effect of mothers positive parenting on child regulation intercept differences between conditions of mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder.

The plot indicated that, for mothers who demonstrate positive parental behaviors that are lower than .25 SD below the mean (Figure 3, left of the vertical dashed line), those with a lifetime internalizing disorder have children with higher regulation at 3 months than mothers without a lifetime internalizing disorder. For mothers with positive parental behaviors that are higher than .25 SD below the mean, the effect of mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder does not influence the relationship between positive parental behaviors and child regulation at 3 months.

In predicting maternal effects on child on the slope of regulation development, the main effect model showed that mothers' lifetime internalizing disorder demonstrated a negative association with child regulation linear slope (β = −.01, p = .07). Although not reaching statistical significance according to the conventional criteria, this association demonstrated a medium effect size of Cohen's d = .61 (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992) and therefore is worth noting. This effect was not moderated by mothers' positive parental behaviors (β = .01, n.s.).

Main effect and moderation models – current internalizing disorder

All main effects and moderation models included demographic covariates of child gender, mothers’ level of education, fathers’ level of education, and household income. As shown in the bottom block of Table 4, from the main effects model, none of the estimates on the paternal side reached statistical significance. On the maternal side, mothers' positive parental behaviors again were positively associated with the intercept of the child's developmental trajectory (β = .20, p < .05), with higher levels of positive parental behavior associating with a higher intercept of the regulation trajectory. The interaction between maternal current internalizing disorder and positive parental behaviors did not reach statistical significance (β = −.29, n.s.).

On the paternal side, father's current internalizing disorder was significantly associated with both child regulation intercept (β = .34, p < .05) and slope (β = −.03, p < .05). In other words, children whose father has a current internalizing disorder are more likely to be rated high on the regulation scale at 3 months and demonstrate slower regulation growth from 3 to 24 months. Positive parental behavior did not significantly moderate either of these effects.

Discussion

The current study investigated the effect of maternal and paternal lifetime and current internalizing disorder on the developmental trajectory of infant SR and the potential moderating role of positive parental behaviors. The latent growth model revealed an overall increasing level of SR from 3 to 24 months, with significant individual differences for both the intercept and the linear slope of the SR developmental trajectory. Further, those with a higher SR intercept subsequently experienced a slower growth rate of SR development. Although there was no significant main effect supporting an association between lifetime maternal internalizing disorder and the intercept of the child's trajectory of SR, positive parental behavior was a significant moderator of this association such that maternal lifetime internalizing disorder was associated with higher regulation intercept scores only among those with low levels of positive parental behavior. Mothers’ lifetime internalizing disorder also demonstrated a nonsignificant trend association (albeit with a moderate effect size) suggesting a potential negative association with the slope of SR development. Paternal current internalizing disorder was significantly associated with higher intercept and lower linear slope of the SR trajectory.

The developmental trajectory of infant SR

Consistent with our hypotheses as well as the literature (Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009; Calkins & Fox, Reference Calkins and Fox2002; Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009; Nigg, Reference Nigg2017; Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart1998, Reference Posner and Rothbart2000; Rothbart, Reference Rothbart, Kohnstamm, Bates and Rothbart1989b; Rothbart & Derryberry, Reference Rothbart, Derryberry, Lamb and Brown1981), our latent growth model revealed that infants demonstrate an overall increase in their parent-reported SR scores from 3 to 24 months. Consistent with our hypothesis, significant individual differences in the SR developmental trajectory were identified for both the intercept and linear slope. Such individual differences are consistent with both previous theory and empirical evidence. As Rothbart and Derryberry (Reference Rothbart, Derryberry, Lamb and Brown1981) theorized, child SR, as one of the temperament constructs, has a constitutional basis. In other words, SR reflects a relatively enduring biologically based aspect of the individual, which is also influenced over time by heredity, maturation, and experience. Later empirical studies have also demonstrated such individual differences when studying young children's SR at cross-sectional early developmental stages (e.g., Calkins, Howse, & Philippot, Reference Calkins, House, P and R2004; Johansson, Marciszko, Gredebäck, Nyström, & Bohlin, Reference Johansson, Marciszko, Gredebäck, Nyström and Bohlin2015; Weinberg, Tronick, Cohn, & Olson, Reference Weinberg, Tronick, Cohn and Olson1999) as well as its developmental trajectory during infancy and toddlerhood (Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009; Hendry, Jones, & Charman, Reference Hendry, Jones and Charman2016; Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, Reference Kochanska, Murray and Harlan2000).

Further, our results suggest that children with a higher SR intercept demonstrated a flatter SR development trajectory into 24 months. This result accords with previous findings by Bridgett et al. (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009), who studied infants’ negative emotionality and regulatory capacity from 4 to 12 months of age also utilizing latent growth modeling techniques. Their results revealed a significant negative association between intercept and linear slope for negative emotionality. In addition, they also concluded higher initial negative emotionality scores are associated with a slower regulatory capacity growth rate. Although these results appear to be contradicting typical findings that suggest that higher early SR measures are associated with better later regulatory measures (e.g., Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith1996; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Rothbart and Gartstein2008), it is important to distinguish between studies that examine dependent variables that represent cross-sectional measures of SR constructs versus those (like the current study and the study by Bridgett and colleagues) that model the trajectory, or growth, of SR using growth modeling techniques. With limited available literature, it is not yet clear what the most preferable and/or adaptive pattern of SR growth rate might be. Nevertheless, the two concepts – the level of SR at a certain developmental stage versus the rate of development – should not necessarily be taken as reflecting the same underlying processes.

Parental internalizing disorder and SR development

Next, the current results examined the effects of maternal and paternal internalizing disorder in predicting infant SR development. The current study found a null association between the main effect of mothers’ lifetime or current internalizing disorder and the intercept of the infant SR trajectory. This null finding is surprising and contradicts some previous literature that has observed evidence of such associations between both lifetime history and concurrent disorder (e.g., Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Pariante, Marks, Davies, Farrelly, Schacht and Moran2012; Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Shaw, Kovacs, Lane, O'Rourke and Alarcon2008; Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Fox, Cohn, Galles and Kovacs2006; Goodman, Reference Goodman and Calkins2015; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011). Several reasons may explain the difference between results from the current study and the literature. The SR intercept in the current study represents child SR at a very early developmental stage (i.e., 3 months). It may be that SR at such an age is not sufficiently stable to reflect the impact of maternal internalizing disorder. Relatedly, as young infants still rely heavily on orienting reflexes for their regulatory needs, it may be difficult to distinguish the automatic versus deliberate regulation process with the 3-month SR measure. Another notable difference is that the current study adopted the HiTOP model and grouped together several psychiatric disorders that share the characteristic of affective dysregulation. It is possible that this approach diluted effects that were specific to one disorder (e.g., depression), although the arguments that we presented in the introduction regarding the significance of transdiagnostic features, such as affect regulation, would mitigate against this possibility.

On the one hand, our results revealed that infants with fathers who experience concurrent internalizing disorder were rated higher on SR at 3 months than those with fathers without current internalizing disorder. Although this finding may appear to be counter-intuitive, it is important to consider these findings within the developmental perspective. On the other hand, as discussed above, at 3 months the current SR measures may reflect more rudimentary regulatory capacity (e.g., orienting) than what is measured at a later age. In addition, although it is a strength of the current study to include both mothers' and fathers' rating on child regulation at each measurement point, at 3 months, reporting bias from fathers’ ratings may be possible given the generally lower father involvement in early child-rearing activities than that of mothers. The current results add to the literature on the impact of paternal psychopathology on child development by providing further empirical evidence of such associations and emphasize the importance of investigating the role of paternal psychopathology. In addition, our study extends the literature by identifying the association at an early developmental stage, offering important clinical implications for early identification, prevention, and intervention for infants at-risk for problematic SR development.

When the growth rate of SR development is concerned, our results revealed that maternal lifetime internalizing disorder demonstrated a negative trend association (with a moderate effect size) and paternal current internalizing disorder demonstrated a significant negative association. Several points are worth discussing from this set of results. First of all, these results are comparable with those reported in Bridgett et al. (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009), one of the few studies inquiring the predictive effects from parental psychopathology on the growth trajectory of SR early in life. Their results indicated that, maternal depression measured at 4-months postnatal demonstrated a level trend association with greater increase (steeper slope) in negative emotionality from 4 to 12 months. Although these two studies appear to conclude the opposite effect, it is important to consider the different constructs being measured. That is, the negative emotionality construct measured in Bridgett et al. (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009) aims to represent infant reactivity, or the involuntary control process, and the regulation construct measured in the current study aims to represent the voluntary or effortful process of regulation. Further, several studies have concluded a negative association between early reactivity and regulation (e.g., Kochanska, Coy, Tjebkes, & Husarek, Reference Kochanska, Coy, Tjebkes and Husarek1998; Rothbart & Sheese, Reference Rothbart, Sheese and Gross2007). Taken together, the results from the current study and those of Bridgett et al. (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009) extend the current literature by, first, informing not only the inverse relationship between reactivity and regulation but also the potential opposite rate of growth for early reactivity versus regulation. In addition, these results highlight the importance of understanding the impact of early risk factors on the pattern of changes of child temperament over time.

Second, based on our findings that infants whose mothers presented with a lifetime internalizing disorder (medium effect size) and fathers who presented with a current lifetime internalizing disorder at 3 months postpartum, demonstrated a slower SR growth in the first 2 years of life, the current study offers preliminary evidence that a faster SR growth rate in the first 2 years of life may be the preferred developmental direction. Although we did not directly test the long-term implication of early SR growth rate in the current study, this speculation is consistent with theories that describe the rapid maturation of regulatory capacity during late infancy (Calkins & Fox, Reference Calkins and Fox2002; Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart1998; Rothbart & Rueda, Reference Rothbart, Rueda, Mayr, Awh and Keele2005; Rueda et al., Reference Rueda, Posner and Rothbart2005). This finding is also consistent with those reported in Bridgett et al. (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, Lance, Iddins, Waits and Lee2011), which reported that a faster increase of infant orienting/regulatory capacity (i.e., higher linear slope) predicted higher effortful control at 18 months. Future work is needed to continue to investigate the implication of an early developmental course of SR growth.

Last but not least, our study revealed differential implications of mothers’ versus fathers’ psychopathology on child SR. Unfortunately, the current study has limited data with which to address the possible explanations for these differences, and any such investigation should address this issue not only with appropriate measures, but should also be driven by well-articulated theoretical accounts of potential gender differences in these phenomena. However, the findings do strongly suggest that further research on the differential mechanisms that may be underlie these differences is warranted.

Moderating role of positive parental behaviors

Similar to the differential effects of mothers’ versus fathers’ internalizing disorder on infant SR development, the current study also reveals unique moderation effects of mothers’ versus fathers’ positive parental behaviors. That is, only maternal positive parental behaviors buffered the negative association between maternal lifetime internalizing disorder and infant SR at 3 months. The negative impact of fathers’ current internalizing disorder on both SR at 3 months and SR growth rate did not differ as a function of fathers’ positive parental behaviors.

On the mothers’ side, our results suggest that the presence of mothers’ lifetime internalizing disorder is only positively associated with infant SR at 3 months for mothers who demonstrated low levels (i.e., lower than .25 SD of the mean) of positive parental behaviors. However, as long as mothers demonstrate maternal positive parental behaviors that are above .25 SD of the mean, their lifetime internalizing disorder was not associated with their infants’ 3 months SR. This finding is consistent with both the general notion of the protective potential of mothers’ positive parenting (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lamb and Garcia Coll2015; Masten & Barnes, Reference Masten and Barnes2018) as well as empirical studies suggesting the protective effect of mothers’ positive parental behaviors protecting infants against the negative effect of maternal psychopathology on infant SR (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Evans and Monk2008; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lamb and Garcia Coll2015; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Letourneau, Campbell, Tomfohr-Madsen and Giesbrecht2017). Interestingly, our results identified this moderation effect only for mothers’ lifetime internalizing disorder, but not for concurrent internalizing disorder. Considering the conceptualization of lifetime internalizing disorder as representing mothers’ long-term disturbance of affective dysregulation (Murray, Reference Murray1992), it is also likely that they have more time to recover and are more malleable to changes.

In contrast, Fathers’ positive parental behaviors did not moderate the association between fathers’ internalizing disorders and infant SR. Although emerging literature has pointed out a positive association between fathers’ positive parenting and child SR outcomes (Cabrera & Roggman, Reference Cabrera and Roggman2017; Gallegos et al., Reference Gallegos, Murphy, Benner, Jacobvitz and Hazen2017; Stgeorge & Freeman, Reference Stgeorge and Freeman2017; van Prooijen et al., Reference van Prooijen, Hutteman, Mulder, van Aken and Laceulle2018), there is a lack of studies specifically testing the moderating/buffering effect of fathers’ positive parenting. Nevertheless, several studies have compared the time spent with children by mothers versus fathers and concluded that, compared with fathers, mothers spend significantly more time alone with child and more overall responsibility for childcare activities (Craig, Reference Craig2006; Parker & Wang, Reference Parker and Wang2013). Furthermore, interviewing over 16,000 parents regarding their time spent caring for or interacting with their children in a 24-hour period, the results from Hook and Chalasani (Reference Hook and Chalasani2008) indicating differences between father–child and mother–child time are more prominent for children under 5 years. In the current study, our sample comprises infants and toddlers under 2 years, an age range that typically requires substantial mother involvement. Taken together, father involvement may be limited at this age range and therefore may not be rendering significant moderation effect.

Limitations

Some caution must be exercised when interpreting the findings from the current study. First, the main dependent variable, child SR, was measured via parent report. This method may not adequately and objectively capture the full scope of children's regulatory capacity. Although the current study best accounts for this methodological limitation by taking into consideration both mothers’ and fathers’ ratings of their children's regulatory capacity at each assessment point, it is important to note that parents’ ratings may be confounded by their own elevated psychopathology symptoms. Specifically, some literature has suggested that mothers with elevated depressive symptomatology are more likely to be negatively biased in reporting their children's functioning (Chilcoat & Breslau, Reference Chilcoat and Breslau1997; Najman et al., Reference Najman, Williams, Nikles, Spence, Bor, O'Callaghan and Andersen2000). Relatedly, the current study utilized a different measure of SR at Wave 4 than it did on the previous waves, as different measurement instruments are necessary to validly represent SR at corresponding developmental stage. Although we accounted for this issue by utilizing developmentally appropriate SR measures that are theoretically and empirically validated, with corroborating evidence demonstrating the significant intercorrelations among all SR measures, this change of measurement needs to be taken into consideration when interpreting the change of SR scores from 3 to 24 months.

Second, the current sample consists of 52% and 26% of mothers and fathers, respectively, who endorsed a lifetime internalizing disorder, suggesting that although this current sample was drawn from a community sample, there may have been factors that affected participation that favored high-risk participants. Taking into consideration the rates reported in epidemiological studies (e.g., 20.6% of lifetime major depressive disorder, 31.1% of lifetime anxiety disorder; Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Sarvet, Meyers, Saha, Ruan, Stohl and Grant2018; NIMH, 2017), psychopathology may be over-represented in the current study, and as such replication studies with different samples are therefore encouraged.

Third, the current study investigated parental behaviors as a moderator. In the meantime, literature has suggested parenting as a mechanism through which parental psychopathology negatively impacts child SR outcomes – in other words, parenting may act as a mediator (e.g., Hoffman, Crnic, & Baker, Reference Hoffman, Crnic and Baker2006; Turney, Reference Turney2012). We focused on testing moderation models because we felt that they were most strongly suggested by the current literature, but future research should also directly test mediation models as well. There are certain design criteria that studies should ideally meet when testing mediation models, such as longitudinal separation of the independent, mediator, and dependent variables (Selig & Preacher, Reference Selig and Preacher2009). Relatively few studies directly compare mediation and moderation models so that we can distinguish which model best fits the data. In terms of implications for intervention however, it is important to note that consistent evidence of both mediation or moderation would support focusing on parenting as a salient point of leverage in treatment and prevention programs.

Fourth and finally, although the current study was able to establish a temporal direction between parental internalizing disorder and parental behaviors measured at 3 months in predicting children's SR growth from 3 to 24 months, the same temporal direction cannot be established for SR intercept. To date, research on the directionality of child temperament and parenting practices has been mixed. Some researchers argue that, although parental behaviors influence child outcomes, the child's behavior likewise influence parents as well (e.g., Klein et al., Reference Klein, Lengua, Thompson, Moran, Ruberry, Kiff and Zalewski2018; Lengua & Kovacs, Reference Lengua and Kovacs2005). As reviewed by Bridgett et al. (Reference Bridgett, Gartstein, Putnam, McKay, Iddins, Robertson and Rittmueller2009), most literature examining children ages 0 to 5 years indicated unidirectional effects from children's temperament on parental behaviors. In addition, when early temperamental characteristics such as reactivity are at issue, some research has shown that the effects of parental behaviors on later child regulatory outcomes may partly be moderated by biologically driven levels of reactivity (Hendry et al., Reference Hendry, Jones and Charman2016). These further increase the challenges to disentangle the directionality of associations among parent dysregulation, child dysregulation, and parent–child interactions.

Strengths and implication

In spite of the above-mentioned limitations, the current study contributes to the existing literature on child SR in several meaningful ways. First, despite extensive theory on early SR development, the current study is among very few studies to explicitly examine the developmental trajectory of SR in the first 2 years of life using a within-subject longitudinal design. Such examination of developmental trajectories significantly advances the existing literature that is largely based on cross-sectional analyses on SR outcomes. More importantly, results from this line of inquiry offer insights into how early risk factors might impact the change, or the developmental course of child SR, and therefore provide critical implications for early prevention and intervention.

Second, the sample size (n = 166) provides sufficient statistical power for the research questions of interest in the current study. Relatedly, as Little (Reference Little2013) suggested, longitudinal SEM relies on sample size as well as degrees of freedom. In the current study, for instance, the final moderation model presents with a df of 52 for the model involving lifetime internalizing disorder, corroborating the credibility of our statistical models. Further, it has been suggested that, with a latent growth model, an increased number of measurements typically in turn increase the precision of parameters being estimated (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Bundesen, Olson, Humphreys, Chavda and Shibuya1999). The repeated measurements of SR variables across four assessment time points in the current study therefore suffices such needs. In addition, statistical power is further strengthened by the minimum drop-out rate (retention rate at W4 = 97.60%) and low missing data rate (<5% for the majority of the main study variables) in the current study.