INTRODUCTION

Immigration is the federal government's top funding priority when it comes to law enforcement. In 2012, Congress appropriated $18 billion for immigration enforcement while it appropriated $14 billion for all the other major criminal law enforcement agencies combined (Foer Reference Foer2018). Moreover, the percentage of the population that is foreign-born is higher than it has been since 1910 (Batalova and Alperin Reference Batalova and Alperin2018). Seeded in immigration reforms in the 1980s and 1990s establishing immigrants with criminal backgrounds as priorities for removal, programs leveraging the criminal justice system to identify such individuals have blossomed. These programs, like 287(g), the Criminal Aliens Program and Secure Communities, knit immigration enforcement into the day-to-day activities of criminal justice administration. At present, ICE has 287(g) agreements (which trains local police to act as ICE surrogates) in nearly 80 jurisdictions across 20 states, and Secure Communities (which requires local jails to hold immigrants for 2 days to allow for transferal to ICE custody) is technically implemented across all jurisdictions (Capps et al. Reference Capps, Chishti, Gelatt, Bolter and Ruiz Soto2018; Center 2019).

The threat of detention and deportation faced by non-citizens has negative consequences for mental and physical health, public safety, and civic trust. Collaborative programs operate in conjunction with preemptive policing practices already employed by local law enforcement to target immigrants broadly, irrespective of criminal offense and documentation status. As such, the negative material and civic consequences of punitive immigration policy spill over to those who may not personally be at risk for detention and deportation, but who contend with the consequences of these policies because they threaten a loved one. Scholars refer to experiencing punitive policies vicariously via a loved one as proximal contact and demonstrate its political impact in the areas of criminal justice, healthcare, and welfare (Michener Reference Michener2018; Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007; Walker Reference Walker2014). With respect to immigration, scholars find that among Latinos, proximal contact negatively impacts physical and mental health (Aranda, Menjivar, and Donato Reference Aranda, Menjivar and Donato2014; Pedraza, Nichols, and LeBrón Reference Pedraza, Nichols and LeBrón2017; Vargas, Sanchez, and Valdez Reference Vargas, Sanchez and Valdez2017), and erodes trust in government and belief in the efficacy of political institutions (Rocha, Knoll, and Wrinkle Reference Rocha, Knoll and Wrinkle2015; Sanchez et al. Reference Sanchez, Vargas, Walker and Ybarra2015).

Punitive policies like those governing immigration teach individuals lessons about their worth as citizens, the value of their civic voice, and can make political issues newly salient, shaping opinion toward relevant policy items (Campbell Reference Campbell2003). Scholars find that negative experiences with punitive policies can diminish political participation, especially voting (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Soss Reference Soss1999). Emerging research showcased in this volume highlights that often the lessons learned from interactions with the carceral state regard power (or lack thereof) available to citizens to create change through formal politics, even as citizens develop politicized sensibilities (Weaver, Prowse, and Piston Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2020). At a time when the importance of communities of color at the polls is growing, the consequences of punitive immigration policy could countervail their otherwise growing engagement, particularly among Latinos who are specifically targeted by such policies (Gonzalez-Barrera and Krogstad Reference Gonzalez-Barrera and Manuel Krogstad2018; Israel-Trummel and Shortle Reference Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2019).

Yet, existing research on the consequences of immigration enforcement for participation is mixed. An extensive body of work finds that a threatening policy environment can spur participation, even among those who are not personally threatened by detention and deportation, out of a sense of solidarity, or as work in this special issue demonstrates, via a heightened ethnic identity (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Manzano, Ramirez and Rim2009; Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura Reference Pantoja, Ramirez and Segura2001; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Maltby, Jones and Vannetteforthcoming). At the same time, a punitive immigration environment can also drive vulnerable populations away from engaging with government institutions (Israel-Trummel and Shortle Reference Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura Reference Pantoja, Ramirez and Segura2001; Potochnick, Chen, and Perreira Reference Potochnick, Chen and Perreira2017; Vargas Reference Vargas2015; Vargas and Pirog Reference Vargas and Pirog2016; Watson Reference Watson2014). Indeed, as Filindra and Goodman (Reference Filindra and GoodmanN.d.) write by way of introducing a special issue on the topic, “Immigration policy is multidimensional, exceedingly complex and very consequential for targeted noncitizens, their families and their communities,” and the political consequences of immigration enforcement match policy in complexity (p. 23). This essay therefore considers the following questions: does proximal contact with immigration enforcement impact political participation? If so, by what means? Since what we know about the spillover consequences of immigration policy primarily concerns Latinos, how do these relationships vary among racial subgroups?

While little work on immigration enforcement examines the mechanisms connecting proximal contact to participation, criminal justice research offers insight into the conditions under which contact mobilizes or demobilizes. Scholars theorize that participation outcomes hinge on whether individuals view their experiences as a reflection of a larger set of institutional biases that disadvantage them on the basis of race, or alternatively, as a product of the poor choices of their loved one caught up in the system. Vicarious experiences with punitive policy impart powerful lessons about the nature of government and one's relationship to it, and research in criminal justice demonstrates the voracity of proximal linkages to the system (Walker Reference Walker2014; Reference Walker2016; Walker and García-Castañon Reference Walker and García-Castañon2017). Viewing one's proximal experiences as systemically biased can mobilize (Walker Reference Walker2016), while viewing them as basically just demobilizes (Burch Reference Burch2013; Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014). Building on Walker's theoretical insights with respect to both the importance of proximal contact to political behavior, we argue that as a mechanism to participation, a sense of injustice is a political psychological response to a targeted policy with deeply negative civic and material consequences. As such, it is not limited to criminal justice. We expect that other policies that likewise target groups based on race/ethnicity, like immigration, may also impact participation via a sense of injustice. We anticipate that a sense of injustice arising from proximal contact with immigration enforcement should prompt political mobilization.

The mobilizing effect of a sense of injustice around immigration should primarily hold among Latinos, who have been targeted for heightened scrutiny by immigration agents. However, these effects may also extend to Asian and Black Americans, who in the first case have strong ties to the immigration experience and who in the second case experience targeting by law enforcement more generally. While whites are less likely to have contact with immigration and to view any kind of law enforcement as systemically biased, proximal contact may nevertheless educate them about the nature of the system and they may likewise be mobilized when they view it as unjust.

In order to evaluate our argument, we employ a survey fielded in 2018 with representative samples of Latino, Black, Asian, and white Americans to investigate the relationship between proximal contact with immigration enforcement, a sense of injustice, and political behavior. We leverage an individual-level measure of proximal contact, where respondents were asked whether they have a loved one, such as a friend or family member, who has been questioned by law enforcement about their citizenship status or who has faced detention or deportation. Over-samples of non-white groups permit an investigation of variation in the political consequences of proximal exposure to immigration enforcement across racial subgroups. This is an important opportunity since past research around proximal contact with immigration enforcement has focused primarily on Latinos, and research in criminal justice has largely focused on the Black–white divide or has grouped non-whites. Although we find variation across subgroups in the extent to which proximal contact leads to a sense of injustice, for every group under study having a loved one who has interacted with law enforcement for reasons related to immigration positively and statistically predicts protest behavior. We find evidence that a sense of injustice underlies this relationship among the full sample, and to a lesser extent among white and Asian Americans. Among Latinos and Black Americans, a sense of injustice is associated with protest behavior irrespective of contact, although contact appears to amplify this effect.

This paper's primary contributions are twofold. While scholars have demonstrated that proximal contact with immigration enforcement impacts a variety of social and health-related outcomes, very little research examines political attitudes and behaviors. We theorize and find evidence to support the idea that individuals become mobilized to participate in protests when they view their proximal experiences as a reflection of systemic injustice. Moreover, we find that the positive relationship between proximal contact with immigration enforcement and protest behavior crosses racial boundaries. The second contribution of this paper is an explicit investigation into the effects of proximal contact among racial subgroups. While we might expect effects to hold primarily among Latinos, who are themselves targeted for contact by enforcement officials, we instead find that Black, Asian, and white Americans are likewise mobilized by proximal immigration experiences. In an era characterized by the expansion in scope and voracity of immigration enforcement, understanding the feedback effects of these policies has never been more pressing.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Feedback Effects of Proximal Contact

Interactions with government institutions have political consequences. Scholars argue that a given policy shapes civic attitudes and engagement through its impact on resources important to participation, and the way its structure treats citizens (Campbell Reference Campbell2003; Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004). Punitive policies characterized by behavioral monitoring and sanctions in the form of fines, fees, detention, and in the case of immigration, deportation, erode trust in government and send the message to constituents that their membership in the polity is not valued (Soss Reference Soss1999). Citizens transmit the civic lessons learned in one policy arena to the government more generally, and these effects are evident in the areas of healthcare, welfare, education, criminal justice, and increasingly, immigration (Bruch and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018; Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Michener Reference Michener2018; Pedraza, Nichols, and LeBrón Reference Pedraza, Nichols and LeBrón2017; Soss Reference Soss1999).

Political learning likewise occurs among those who experience the policy vicariously through a family member or loved one, even if they have not personally engaged with the policy. Scholars refer to this as proximal contact, demonstrating that the civic consequences of a given policy extend to whole communities (Burch Reference Burch2013; Walker Reference Walker2014). Developed in the context of criminal justice, proximal contact is understood as, “knowing one or multiple people who have had personal contact but not having personal contact with the criminal justice system…among those with proximal contact, interactions with the criminal justice system are made salient by the strength of the tie to the individual with personal contact” (Walker Reference Walker2014, 810). Conceptually, proximal contact is designed to capture the power of relational ties to shape political outcomes. While all sorts of relationships can teach civic lessons, proximal contact is most politically salient when the connection is familial or to an otherwise important figure in one's life (Walker and García-Castañon Reference Walker and García-Castañon2017). Proximal contact promises to be particularly meaningful in the area of immigration, where interactions with enforcement officers can lead to detention, deportation, and family separation (Sanchez et al. Reference Sanchez, Vargas, Walker and Ybarra2015). The threat of detention and deportation faced by the undocumented leads them to avoid interacting with a whole host of government institutions to reduce the risk of exposure (Pedraza, Nichols, and LeBrón Reference Pedraza, Nichols and LeBrón2017). Threat induced by increasingly stringent immigration policies degrades physical and mental health, and heightened anxieties are felt by their documented loved ones (Aranda, Menjivar, and Donato Reference Aranda, Menjivar and Donato2014; Flores Reference Flores2014; Potochnick, Chen, and Perreira Reference Potochnick, Chen and Perreira2017; Vargas Reference Vargas2015; Vargas and Pirog Reference Vargas and Pirog2016; Vargas et al. Reference Vargas, Juárez, Sanchez and Livaudais2018).

Whether the civically corrosive consequences of punitive policies extend to participation depends on how individuals view their experiences. When individuals view their experiences as unfair and as a product of targeting on the basis of race or ethnicity, they can be politically mobilized (Gamson Reference Gamson1968; Gillion Reference Gillion2013). If, in contrast, they view their negative experiences as indiscriminate or intractable, they may be politically demobilized (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Soss Reference Soss1999). For example, policy feedbacks scholars demonstrate that interactions with welfare, criminal justice, and school discipline diminish voting (Bruch and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018; Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Soss Reference Soss1999). Yet, in instances where individuals connect their personal experiences to a larger collective struggle, they become engaged, and mobilization is likewise evident around welfare and criminal justice (Ernst Reference Ernst2010; Piven Reference Piven2003; Walker Reference Walker2014).

The Feedback Effects of Immigration Policy

These dynamics, where a politicized consciousness derived from negative interactions with policy promotes participation, are present in the area of immigration. A large body of work demonstrates that a threatening immigration environment can spur participation, both electoral and non-electoral (Israel-Trummel and Shortle Reference Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; White Reference White2016). An oft-cited example is mobilization among Latinos in CA in the 1990s in response to xenophobic rhetoric employed by then gubernatorial candidate Pete Wilson (Bowler, Nicholson, and Segura Reference Bowler, Nicholson and Segura2006; Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura Reference Pantoja, Ramirez and Segura2001; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003). Likewise, Latinos of all stripes took to the streets to protest a draconian immigration bill passed by the House and considered by the Senate in the spring of 2006, ultimately killing the legislation (Zepeda-Millán Reference Zepeda-Millán2017).

Recent work suggests more specifically that proximal contact with immigration has a dynamic relationship with participation. Drawing on the Current Population Survey voter supplement, Amuedo-Dorantes and Lopez (Reference Amuedo-Dorantes and Lopez2017) find that punitive immigration policies reduce voting among mixed-status families. At the same time, Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán (Reference Street, Jones-Correa and Zepeda-Millán2017) find that children with undocumented parents are more likely to protest. These patterns are consistent with the behavioral consequences of proximal contact with the criminal justice system. Here, researchers find that even as proximal contact diminishes voting (Burch Reference Burch2013; Walker Reference Walker2014), it can nevertheless heighten participation in activities outside the ballot box (Anoll and Israel-Trummel Reference Anoll and Israel-Trummel2019; Walker Reference Walker2014). Unlike voting, activities like protesting offer an immediate outlet for frustration and fear springing from personal and proximal experiences with immigration enforcement (Gillion Reference Gillion2013). Likewise, the risk of revealing the status of a loved one may direct individuals away from government institutions even as they engage with other types of organizations and activities (Brayne Reference Brayne2014; Pedraza, Nichols, and LeBrón Reference Pedraza, Nichols and LeBrón2017). Researchers point to anger, ethnic solidarity, and political socialization in an era of immigrant activism to explain the mobilizing effect of a threatening immigration environment (Israel-Trummel and Shortle Reference Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Maltby, Jones and Vannetteforthcoming; Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán Reference Street, Jones-Correa and Zepeda-Millán2017). While little research explicitly examines the factors linking proximal contact with immigration enforcement to engagement, the positive association between threat and a politicized identity suggests that it plausibly links proximal exposure to immigration enforcement to heightened participation.

Moreover, researchers do not find that having a loved one threatened by detention or deportation is politically alienating (Rocha, Knoll, and Wrinkle Reference Rocha, Knoll and Wrinkle2015; Vargas, Sanchez, and Valdez Reference Vargas, Sanchez and Valdez2017), even as it shapes policy attitudes (Rocha, Knoll, and Wrinkle Reference Rocha, Knoll and Wrinkle2015; Sanchez et al. Reference Sanchez, Vargas, Walker and Ybarra2015). The policy feedbacks literature suggests that when individuals view experiences with punitive policies as a result of their own poor choices or beyond their ability to affect change (both markers of alienation), they politically withdraw. In contrast, when they view those same experiences as a reflection of a larger set of institutional biases, they may become politically engaged. Thus, existing studies demonstrate patterns consistent with the idea that proximal contact can politically mobilize, based on what we know from the policy feedbacks literature.

The line of inquiry into the mobilizing effect of interactions with punitive institutions has been pursued, in particular, with reference to criminal justice. We therefore borrow from findings around “the closely analogous phenomena of knowing someone who has been incarcerated or had some kind of contact with the police” to shed light on the political consequences of proximal experiences with immigration (Sanchez et al. Reference Sanchez, Vargas, Walker and Ybarra2015, 459). This work finds that proximal criminal justice experiences are positively associated with participation when individuals view criminal justice policy as racially biased and unequally applied (Drakulich et al. Reference Drakulich, Hagan, Johnson and Wozniak2017; Anoll and Israel-Trummel Reference Anoll and Israel-Trummel2019; Walker Reference Walker2014). It is important to note that researchers observe the mobilizing effects of proximal contact with respect to non-voting activities, and that it has no relationship with voting. Following the injustice framework developed with respect to policing, those with a proximal connection to immigration may likewise be mobilized by the perception that enforcement targets individuals based on physical markers like skin color, language, and accent irrespective of documentation status, itself an unobservable characteristic.

The Nature of Race and Injustice

Although scholars have relied on group consciousness, linked fate, and ethnic solidarity to explain the mobilizing power of immigration policy among Latinos, a sense of injustice is distinct from these concepts in ways important for proximal contact. Group consciousness is fundamentally about group solidarity derived from personal experiences with discrimination on the basis of membership in that group. The lessons learned via proximal contact are indirect, and while they are structured by race, they are not bound by racial group membership.Footnote 1 Issues become salient for those with proximal contact when a loved one is threatened, and one need not themselves be threatened in order to be moved by the civic lessons they learn vicariously. That individuals are moved to defend loved ones even when their own well-being is not threatened is universal, even as the likelihood of having proximal contact is structured by race.

Instead of organizing individuals in reference to their racial group, interactions with punitive institutions organize individuals in reference to the nature of the institution. For this reason, rather than leveraging group consciousness scholars turn to perceptions of the institution and the belief it violates democratic norms through the unequal application of policies and procedures, disrespectful treatment of citizens, and unreasonable motives for contact. Criminal justice scholars refer to the belief that a policy violates democratic norms of fairness and equality as procedural injustice (Meares Reference Meares2012; Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003). A robust literature demonstrates the importance of procedural justice to citizens' belief that the law is legitimate, and thus their compliance with the law and cooperation with institutional actors. Examining the political implications of proximal contact thus turns our attention to the importance of lived experience, in addition to histories of group-based injustices.

The group consciousness literature nevertheless offers insight into how we might expect racial subgroups to respond to proximal contact with immigration enforcement. Race structures interactions with law enforcement of all types (Maltby Reference Maltby2017), where whites are much less likely to have any type of contact and more likely to know people who have had positive interactions with the system than are Blacks and Latinos, whose personal and proximal experiences are more likely to be antagonistic (Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017). Moreover, each racial subgroup has very different histories with institutional and social exclusion more generally, and the extent to which individuals view experiences with immigration as systemically unfair should likewise vary.

While interactions with immigration enforcement are not bound by race according to the letter of the law, they are racialized in practice, with Latinos comprising an overwhelming number of deportations in the last several years (Zong, Batalova, and Hallock Reference Zong, Batalova and Hallock2018). Moreover, practices, both written and unwritten, that support targeting individuals based on citizenship status place Latinos squarely in the cross-hairs of immigration enforcement (Israel-Trummel and Shortle Reference Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019). Research demonstrates that Latino group identity is context-specific, becoming particularly salient in reference to immigration, shaping public opinion and spurring political action (Sanchez Reference Sanchez2006; Sanchez and Masuoka Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010). Latinos are both most likely to have a loved one who has had contact with immigration enforcement, those experiences are more likely to be antagonistic than for other groups, and the subsequent mobilizing power of viewing that experience through the lens of injustice should be fairly strong.

Like Latinos, Asian Americans have a strong connection to the immigrant experience, and are the fastest growing immigrant group in the United States. Nearly 60% of those living in the United States are foreign born (López, Ruiz, and Patten Reference López, Ruiz and Patten2017). Comparatively, only 19% of Latinos in the United States were born elsewhere (Flores Reference Flores2017). Like Latinos, they are more likely to have a loved one who has had involuntary contact with enforcement officials, relative to Black and white Americans. Moreover, like Latinos, Asian American pan-ethnic identity is shaped by contextual factors (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008; Masuoka Reference Masuoka2006; Wong, Lien, and Conway Reference Wong, Lien and Conway2005), and evidence suggests Asian Americans mobilized in response to threatening immigration policy in the past (Ong Reference Ong2011; Ramakrishnan Reference Ramakrishnan2005). We might therefore expect Asian Americans to respond to proximal contact with immigration enforcement in ways that are similar to Latinos. Yet, Asian Americans are not targeted in the same way that Latinos are by immigration policy. It may be that a sense of injustice and the belief that immigration enforcement operates to violate democratic norms is less compelling to this group in reference to political outcomes.

We might at first think that Black and white Americans should serve as a sort of placebo test. Proximal contact is theorized to contribute to one's civic education vicariously via the networks in which those targeted by immigration policy are nested. A sense of injustice reflects civic lessons derived from the experience of watching a loved one contend with punitive policy, and once learned compel political action. As noted above, Latinos and Asian Americans have a higher probability of having a loved one threatened by the system relative to their Black and white counterparts, and they may be more likely to view their proximal experiences through the lens of injustice as a consequence. Because they are not specifically targeted by immigration policy, we might not expect a sense of injustice to yield participatory gains among Blacks and whites. We see this dynamic play out with respect to liberal state policies allowing immigrants access to social welfare goods (Condon, Filindra, and Wichowsky Reference Condon, Filindra and Wichowsky2016; Filindra, Blanding, and Coll Reference Filindra, Blanding and Coll2011). Condon, Filindra, and Wichowsky (Reference Condon, Filindra and Wichowsky2016) demonstrate that progressive policies extending access to welfare goods to immigrants heighten the likelihood of graduating from high school among Latino and Asian youth, but not among Black and white youth. However, Condon, Filindra, and Wichowsky (Reference Condon, Filindra and Wichowsky2016)'s inquiry concerns the impact of expanding access to material goods on material outcomes. A sense of injustice is a political psychological mechanism that develops from witnessing punitive policies in action first-hand. Race therefore structures the likelihood that one will be proximally exposed to immigration enforcement and how one interprets those policies, but a sense of injustice is not exclusive to the groups targeted by the policy. Since the expectation is that mobilization is conditional on a sense of injustice, it is incumbent upon us to consider the method and means by which non-targeted groups may nevertheless be moved by their proximal experiences.

Black Americans are not targeted by law enforcement officials for reasons related to immigration. They may nevertheless have Latinos or Asian Americans in their networks who are targeted by immigration policy. Through these relational experiences, Blacks may learn about the racially targeted nature of immigration policy, and may discover a commonality between their own experiences and those had by their loved ones who have been constructed as undocumented. That is, Black Americans may bring a systemic evaluation to bear on immigration policy and practices even as they are not personally targeted by the policy that is unique to this group. As such, it may be the case that for this group, a vicarious experience with immigration is not required to understand racially targeted policies as unjust. Black Americans have a long history of targeting by the criminal justice system, and research demonstrates the powerful mobilizing force of a group-based identity rooted in a history of racial oppression, with which policing is deeply entwined for this group (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981). How should we expect Black Americans' history with institutional racism to map on to immigration enforcement? Social psychologists turn to the concept of racial group empathy. Racial group empathy is developed from personal experiences with discrimination which increase the ability to take the perspective of out-group members, even when group interests may be in conflict (Sirin, Valentino, and Villalobos Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017). Researchers leverage this concept to explain Black opposition to policies targeting Latinos for deportation (Sirin, Valentino, and Villalobos Reference Sirin, Villalobos and Valentino2016a; Sirin, Villalobos, and Valentino Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016b). We might therefore expect that for Black Americans, the belief that immigration enforcement unfairly targets Latinos may itself spur collective action, and proximal contact may not be necessary to make the belief that the system is unjust politically meaningful. Rather than proximity, empathy that manifests as or co-occurs with a sense of injustice may drive participation.

White Americans are least likely to experience immigration enforcement, most likely to view unfair treatment by law enforcement as exceptional (Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010), and are less likely to have antagonistic criminal legal experiences than are Blacks and Latinos (Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017). Nevertheless, although researchers find that whites have a lower baseline level of racial empathy than do Black Americans (Sirin, Valentino, and Villalobos Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017), it may be the case that proximal experiences with immigration educate white Americans and tap a sense of empathy like their Black counterparts. Thus, while they may be less likely to have proximal experiences overall and less likely to view those experiences through the lens of injustice, in the instance that they do interpret those experiences as unfairly biased, they may likewise be politically mobilized.

ARGUMENT AND EXPECTATIONS

This project asks the question: does proximal contact with immigration enforcement impact political participation? We bring together the rich literature on group threat and the growing body of work on the political consequences of proximal criminal justice contact to assess the conditions under which proximal contact with immigration enforcement becomes politically meaningful. We argue that the view that immigration policies and practices are unfairly biased toward Latinos moderates the relationship between proximal contact and political engagement. We anticipate that when individuals view their proximal experiences with immigration enforcement as a reflection of a larger set of institutional biases, they will be politically mobilized. In contrast, individuals who do not view their experiences as unjust should be politically unaffected. Following from findings in the area of criminal justice, which are consistent with the handful of studies examining participation among the children of the undocumented, we anticipate that mobilization will occur outside of the ballot box. This leads to the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 When individuals with proximal contact with immigration enforcement view immigration enforcement as systemically biased on the basis of race or ethnicity, proximal contact will be associated with increasing levels of participation in political activities other than voting.

Hypothesis 2 In the absence of the belief that immigration enforcement is systemically biased, proximal contact will not be associated with political participation of any kind.

Race complicates the relationship between proximal contact and political behavioral outcomes. The mobilizing effect of a sense of injustice springing from proximal contact with immigration enforcement should be strongest for Latinos. Although they are the least incorporated into American politics overall given that a substantial portion of the population in the United States is foreign born, we expect that the model will hold for Asian Americans:

Hypothesis 3 The size of the moderating effect of a sense of injustice on the relationship between proximal contact and participation outcomes should be greatest among Latinos and Asian Americans.

We might also expect the injustice model to hold among Black Americans, who experience institutional discrimination via criminal justice more generally. However, because Blacks are targeted in other arenas and have a strong narrative to explain institutional targeting as systemically unjust, it may not require proximal contact to mobilize this group. They may become politically mobilized by a sense of injustice around immigration out of racial group empathy. This generates the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 Proximal contact and a sense of injustice will be independently and positively associated with participation among Black Americans.

White Americans are less likely to have proximal contact with immigration and are less likely to connect proximal experiences with a larger set of institutional biases, instead viewing instances of unfairness as atypical. Nevertheless, the concept of injustice is designed to reflect that proximal experiences with a given set of institutional biases are not bound by race, even as the practices and policies themselves are racialized. This suggests that although it is unlikely that whites will view proximal experiences with immigration as unjust, when they do they may likewise be mobilized. However, since whites are not personally implicated in and are privileged by immigration enforcement, the size of the mobilizing effect may be relatively modest compared to non-whites. This generates our final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 The size of the moderating effect of a sense of injustice on the relationship between proximal contact and participation outcomes should be smallest among white Americans.

DATA AND MEASUREMENT

In order to evaluate the argument and expectations laid out above, we draw on a cross-sectional national survey of registered voters. We examine the relationship between proximal contact and a sense of injustice and the independent effects of each on political participation. Although we have developed a causal story to explain any association we might observe between proximal contact and participation (pointing to a sense of injustice as the catalyst to act), the use of cross-sectional data precludes a causal analysis absent an exogenous treatment. We might address this limitation through the use of panel data or a repeated cross-sectional design. Unfortunately, the unavailability of data inclusive of both measures of proximal contact with immigration enforcement and indicators of political participation that also include robust subsamples of all four racial groups in question prohibits such an analysis. Therefore, in order to examine the linkages between proximal contact, a sense of injustice, and participation outcomes, we employ a moderation analysis, interacting proximal contact and injustice. This allows us to examine the impact of proximal contact on participation in the presence/absence of injustice, which should reveal patterns that support/fail to support the theory of injustice. In order to assess the robustness of the findings, we further evaluate the sensitivity of the models, conduct placebo tests of the impact of other non-immigration-related variables that might yet prompt participation, examine contextual measures of proximal contact, and employ a matching strategy to compare those with proximal contact to similarly situated individuals without proximal contact.

The survey we employ was fielded during the summer prior to the 2018 election and sampled individuals residing in the 61 most competitive U.S. House districts heading into midterms. The instrument was designed to capture the opinions of potential voters in so-called “swing-districts” around issues related to immigration, and allowed us to embed a battery of questions alongside a variety of other political and demographic indicators. The resulting sample is drawn from 47 states and includes 400 respondents each who are Black, Latino, Asian and Pacific Islander (AAPI), and white, non-Hispanic (n = 1,600).Footnote 2 Those residing in battleground districts are slightly more educated, suburban, and politically moderate than the population as a whole. In order to correct for this, each racial/ethnic group was weighted on age, gender, education, and nativity to bring them in line with Census CPS estimates for registered voters. Data collection was overseen by Latino Decisions, Asian-American Decisions, and the African-American Research Collaborative.Footnote 3

The survey included two variables we use to measure political participation, intent to vote and protest behavior. In order to measure intent to vote, the survey asked respondents, “Thinking about the election for Congress and other state offices in November 2018, how likely are you to vote on a scale between 0 and 10, where 0 means you definitely do not want to vote, and 10 means you are 100% certain you will vote, and 5 means you are 50–50 or a maybe.” Approximately 52% of the sample (unweighted) responded that they were 100% sure they would vote. We therefore created a binary indicator, where those who were 100% sure they would vote are coded as one, and less than 100% is coded as zero. In order to measure protest behavior, the survey asked the following: “In the past year and a half, have you taken part in any political protests, marches, or demonstrations?” The variable is dichotomous, with 16% of respondents indicating they had attended some type of demonstration during the timeframe.

The primary independent variable of interest, proximal contact, is measured via two survey items. The first item asks whether the respondent knows “anyone who has been stopped or questioned by immigration officials, or has faced detention or deportation for immigration reasons?” The respondent could provide a list of restricted possibilities, including (1) “Yes I have been stopped and questioned,” (2) “Yes, someone in my family has been stopped or questioned,” (3) “Yes, someone in my family has been detained or deported,” (4) “Yes, a friend or co-worker has been stopped or questioned,” (5) “Yes, a friend or co-worker has been detained or deported,” and (6) “No, do not know anyone.” Anyone who listed 2–5 affirmatively has been coded as someone who had proximal contact with immigration enforcement. The survey further asked whether respondents “know(s) anyone who is an undocumented immigrant?” The respondent is offered the possibility of indicating that the person they know is a family member, friend, or co-worker.

Conceptually, proximal contact is understood as having a relational connection to punitive immigration policy via a loved one. We operationalize this concept through asking individuals whether they know someone with involuntary contact with enforcement officials, or who is at risk of having this kind of contact. This is a blunt measure of the concept, since we allow for the possibility that one's loved ones could include a friend or a co-worker (in addition to family) and since we include knowing someone undocumented. We do this in order to ensure a robust subsample of those with proximal contact. About 20% of the overall sample know someone who has faced detention or deportation, and an additional 12% know someone undocumented even if they have not had contact with enforcement officials. We replicate the main findings presented in the following paragraphs but broken out among those whose proximal connection is familial relative to those whose connection is not familial, and we compare those who know someone who has faced detention and deportation to those who know someone undocumented. This additional analysis, which largely confirms the findings presented here, is located in Section 8 of the Appendix. Likewise, readers may wonder at the self-reported nature of our measure. We therefore validate whether respondents live in contexts where they may be more likely to experience contact with immigrants or undocumented people, since existing research demonstrates that individuals (especially Latinos) are fairly good at assessing the punitive nature of policy context in which they are embedded (Ybarra, Juarez, and Sanchez, Reference Ybarra, Juarez and SanchezN.d.). In the full sample, contextual measures of immigrant contact, such as percent non-citizen and the rate of deportations in a given county, are positively correlated with self-reported contact. This bolsters confidence in our measure.Footnote 4

The (unweighted) distribution of respondents who have experienced contact, disaggregated by race subsamples, is displayed in Table 1. For the full sample, 33% of individuals have experienced proximal contact with immigration enforcement. Among racial subgroups, 22% of white, 53% of Latino, 31% of Black, and 29% of AAPI respondents reported proximal contact with immigration enforcement.

Table 1. Proximal contact by subsample (unweighted)

Finally, the survey included a battery of questions designed to measure perceptions of injustice (PoI) around immigration enforcement. The series of questions is modeled on a battery developed by Walker (Reference Walker2016) to measure perceived injustice with respect to the criminal justice system more generally. The battery asks respondents to reflect on how frequently law enforcement in their community engage in certain behaviors, including verbal harassment, the use of street stops without good reason, and fair treatment of citizens like the respondent (whatever that may mean). We modified this battery to reflect immigration enforcement specifically, asking the following: “Below are some statements about policing and immigration in your community. Please indicate whether each statement describes how you feel about immigration issues in your community: (1) Various law enforcement officials often stop immigrants without good reason; (2) Law enforcement officials treat people like me fairly and respectfully; and (3) Immigration officials often stop and search people solely because of their race, ethnicity, language or accent for reasons related to immigration.” Responses are coded ranging from zero to three, where zero reflects that the respondent indicates satisfaction with officials' behavior and three reflects dissatisfaction with officials' behavior. Following Walker (Reference Walker2016), we use these items to create an index ranging from 0 to 9, where scoring a nine on the scale reflects a high sense of injustice around immigration enforcement in one's community. We refer to this as the PoI scale. Table 2 illustrates the level of a perception of injustice and the variance across subsamples. On the nine-point scale, the respondents possess a sense of injustice equivalent to 4.83 points (SD = 2.25). Likewise, respondents possess a 3.94, 4.93, 5.61, and 4.86 level of a sense of injustice for the white, Latino, Black, and AAPI subsamples, respectively.Footnote 5

Table 2. Perceptions of injustice index summary statistics disaggregated by sample (unweighted)

Our models include a battery of relevant controls for variables that may impact either contact or participation. These include partisan identification operationalized as binary indicators for whether a respondent reports they are a Democrat, independent or affiliated with an “other” party, with Republicans as the reference category. Data on self-reported age are included as binary indicators for ages 18–29 and 65+. Self-reported income data are included as binary indicators for incomes 20–39, 40–59, 60–79, 80–99, and 100–150k. Education binary indicators for high school and post-high school are included, as are binary variables for whether the respondent is female and whether they are foreign born. We also include binary indicators for various racial/ethnic categories, such as whether the respondent is Latino, Black, or AAPI, with white respondents as the reference category.

ESTIMATION STRATEGY

We begin by assessing the baseline relationship between proximal exposure to immigration enforcement and PoI, employing the following linear model:

where PoIi is the nine-point scale measuring the extent to which survey participant i perceives immigration enforcement to be discriminatory. proximal contacti is the binary indicator for whether survey participant i was proximally exposed to immigration enforcement, and X i is a vector of the control covariates described above. ɛi is heteroskedastic robust.Footnote 6 We estimate models for five different samples: (1) the full sample, (2) Latinos, (3) Black Americans, (4) AAPI, and (5) Non-Hispanic whites. This initial analysis allows us to get a sense of the extent to which proximal contact may indirectly impact participation via a sense of injustice, to the extent that it is statistically related to injustice. It also facilitates an evaluation of the underlying factors that may influence a sense of injustice in addition to proximal contact.

To assess the independent effects of proximal exposure to immigration enforcement and a sense of injustice on political participation, we employ the following linear probability models:

As with estimating equation (1), the models are estimated on the full sample and the racial subsamples. We employ a linear probability model in all specifications as opposed to a logit model despite the fact Protesti and Votei are binary variables due to ease of interpretability. The HC2 robust standard error correction should also resolve the heteroskedastic errors intrinsic to modeling binary outcomes in a linear framework.Footnote 7

Finally, to evaluate the extent to which a sense of injustice moderates the relationship between proximal contact and participation, we employ the following models:

$$\eqalign{{\rm Vot}{\rm e}_i = &\alpha _i + \beta _1{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \times {\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _2{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \cr & \quad + \beta _3{\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _4X_i + \varepsilon _i} $$

$$\eqalign{{\rm Vot}{\rm e}_i = &\alpha _i + \beta _1{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \times {\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _2{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \cr & \quad + \beta _3{\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _4X_i + \varepsilon _i} $$ $$\eqalign{{\rm Protes}{\rm t}_i = &\alpha _i + \beta _1{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \times {\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _2{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \cr & \quad + \beta _3{\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _4X_i + \varepsilon _i.} $$

$$\eqalign{{\rm Protes}{\rm t}_i = &\alpha _i + \beta _1{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \times {\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _2{\rm proximal}\,{\rm contac}{\rm t}_i \cr & \quad + \beta _3{\rm Po}{\rm I}_i + \beta _4X_i + \varepsilon _i.} $$These models explicitly test hypotheses 1 and 2, which anticipate that any positive association between proximal contact and political participation manifests primarily for those respondents possessing a sense of injustice with respect to immigration enforcement practices. Again, these models are estimated on the full sample and racial subsamples, which will help to explicate within-group dynamics that support/fail to support hypotheses 3–5.

RESULTS

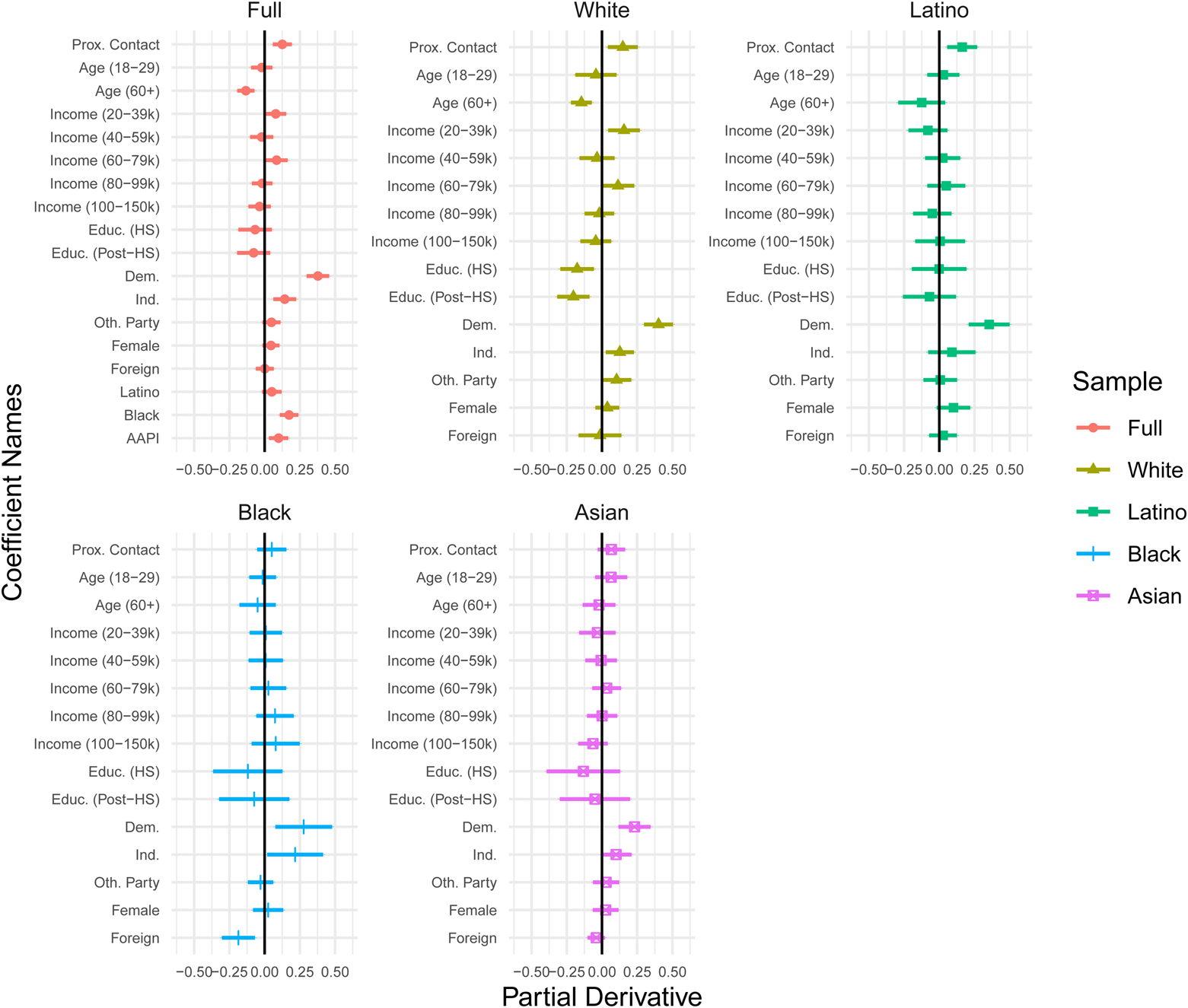

Before we explicitly test our main hypotheses, we show baseline associations suggestive of a mobilizing effect of proximal contact in need of an explanatory mechanism.Footnote 8 First, we describe the association between proximal contact and PoI. Figure 1 illustrates the partial derivatives of proximal contact on PoI subset by race and ethnicity. All variables, both on the right- and left-hand side of the regression, are standardized on the plot.Footnote 9 An increase in one standard deviation in proximal contact with immigration enforcement is associated with a .13 SD increase in the PoI scale in the full sample (on a nine-point scale), a .15 SD increase for the white respondent sample, and a .16 SD increase for the Latino respondent sample. These associations are all statistically significant at p < .05. The partial derivative of an SD increase in contact on PoI for Black and AAPI respondents is .11 SD and .06 SD, respectively, both statistically insignificant.Footnote 10 We can compare the partial derivatives of proximal contact across samples with the effect of other covariates that may be prognostic of the outcome to provide a benchmark for the strength of the link between proximal contact and PoI. The strongest covariate in terms of association with PoI is whether the respondent is a Democrat. An increase of one standard deviation in Democratic identification is associated with a .38, .4, and .35 SD increase in PoI for the full, white, and Latino sample, respectively. This means that the standardized partial derivative of proximal contact is proportional to 34, 38, and 46% of the standardized partial derivative of Democratic identification. This suggests that the positive influence of proximal contact on PoI is quite strong given that Democratic identification is likely a strong predictor of whether a respondent understands the immigration enforcement apparatus as unfair.Footnote 11

Figure 1. Partial derivative plot (outcome: PoI) by subsample (all variables standardized).

Figure 2 illustrates the predicted probabilities of PoI conditional on contact subset by racial group.Footnote 12 Interestingly enough, the predicted probabilities do not suggest significant heterogeneity in the partial derivative across racial subgroups.Footnote 13 With respect to the link between proximal contact and perceptions of a discriminatory immigration enforcement regime, all racial/ethnic subgroups appear to be similarly affected by proximal contact in terms of the marginal change in PoI. Figure 2 further reveals that Black Americans have the highest baseline score on the PoI index independent of proximal contact and even in comparison to their Latino counterparts, which suggests that the statistically insignificant relationship between proximal contact and a sense of injustice for this group is perhaps due to ceiling effects. It further supports findings around criminal justice that Black Americans are more likely to perceive that the criminal justice system discriminates against Latinos more than Latinos themselves (Hurwitz, Peffley, and Mondak Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015). With respect to our theory, this finding supports the idea that Black Americans do not require proximal contact to view immigration enforcement practices as institutionally biased, and that for this group, to the extent that PoI is associated with heightened participation, it may be tapping an underlying sense of group empathy.

Figure 2. Perceptions of injustice index by race and proximal contact.

We next evaluate the independent associations between proximal contact, PoI, and participation (Figure 3). In terms of the association between proximal contact and vote intention, we find no statistically significant association across all subsamples.Footnote 14 Conversely, we find a substantively and statistically significant association between proximal contact and protest behavior. An increase of one standard deviation in proximal contact to immigration enforcement is associated with a .25 SD increase in the propensity to protest for the full sample, a .18 SD increase for the white sample, a .29 SD increase for the Latino sample, .36 SD increase for the Black sample, and a .22 SD increase for the AAPI sample. The predicted probabilities characterize the increase in the original measurements of the independent and dependent variables (Figure 4), where in the full sample, exposure to immigration enforcement shifts one's predicted probability of self-reported protest from 10 to 29 percentage points. The shifts are 8–31, 7–20, 14–42, and 8–25 percentage points among subsamples of Latino, white, Black, and AAPI respondents, respectively.Footnote 15

Figure 3. Partial derivative plot (outcome: political participation) by subsample (all variables standardized).

Figure 4. Political participation by proximal contact and race (panel A = voting outcome, panel B = protest outcome).

The association between proximal exposure to immigration enforcement and self-reported propensity to protest is quite strong and robust. We conduct a sensitivity analysis that assesses how large potential unobserved confounders would have to be to make the association zero between proximal contact and self-reported protest.Footnote 16 We find that a confounder would have to explain 15 times the same degree of variance in the outcome and treatment that the Latino variable explains in the full sample in order to diminish the estimated partial derivative to zero. Given that whether a respondent is Latino is strongly prognostic of treatment and the motivation to protest in response to immigration enforcement, the sensitivity analysis suggests that our results are robust to potential unobserved confounders.

In addition, we allay concerns that the protest item induces measurement error given that it asks respondents whether or not they participate in any protest/demonstration, as opposed to a protest/demonstration related specifically to immigration. First, we show in Section 4 of the Appendix that other motivations for protest are uncorrelated with proximal contact and the protest outcome as a placebo check. Second, we replicate the analysis in this paper amongst Latinos in three additional surveys: (1) the 2010 Pew Hispanic Survey, (2) the 2015 Latino National Health and Immigration Survey, and (3) the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey. The 2010 Pew Hispanic survey includes an item that asks respondents if they participated in protests/demonstrations specifically related to immigration. We find that proximal exposure to immigration enforcement increases the propensity to protest for the sake of immigration by 14 percentage points and the result is statistically significant (p < .001).Footnote 17 The results replicate using a more general protest item in each of the other two surveys.Footnote 18 While these additional analyses are limited insofar as the samples include only Latinos, the finding that proximal contact is associated with protesting specific to immigration and in other contexts both pre- and post-Trump strongly supports the present analysis.Footnote 19

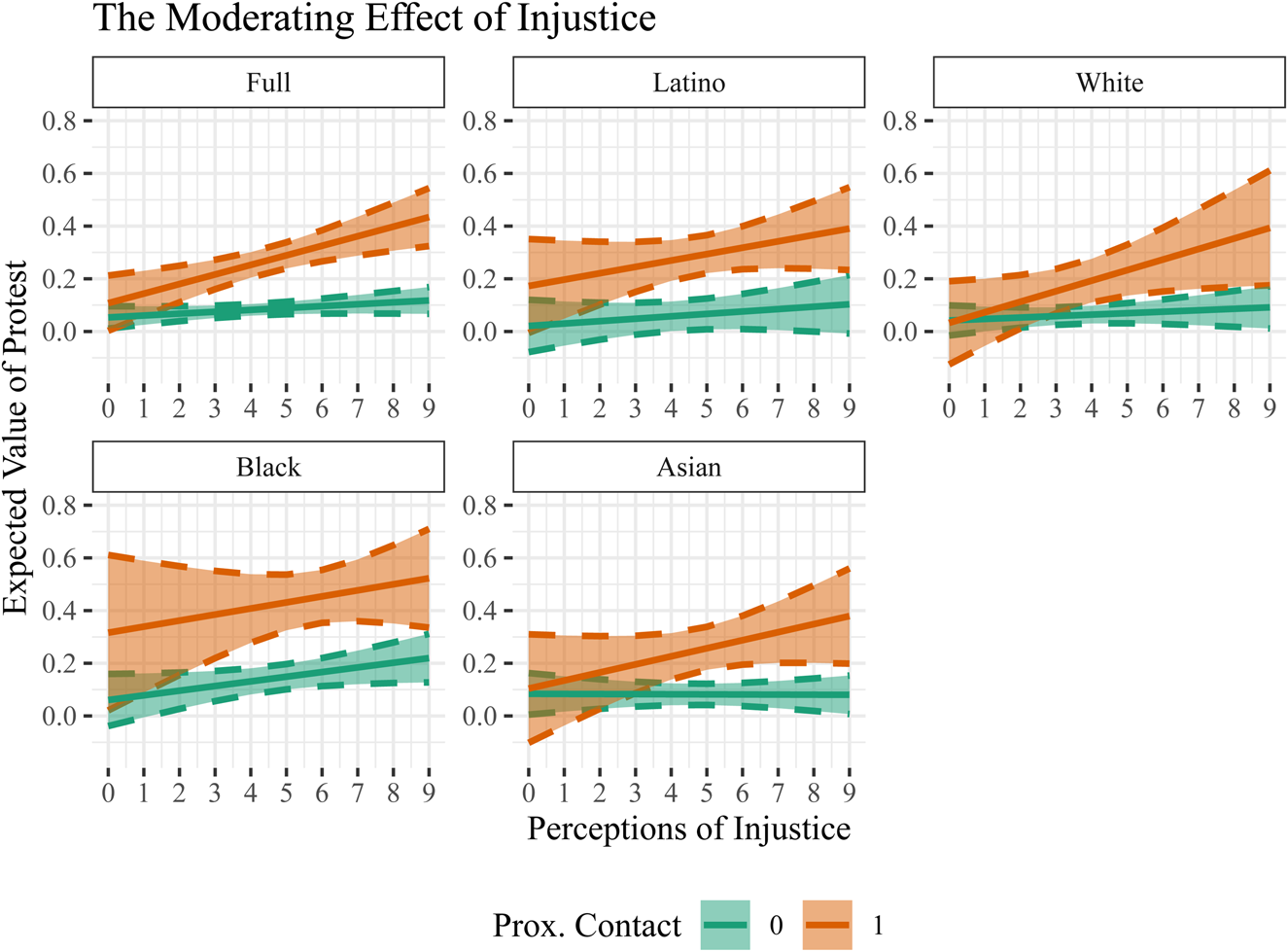

We now turn to an evaluation of the moderating effect of a sense of injustice on the relationship between proximal contact and participation. Since we do not observe any relationship between either proximal contact or a sense of injustice and voting, we limit the moderation analysis to protest behavior.Footnote 20 Hypotheses 1 and 2 indicate that respondents that have experienced proximal contact with immigration enforcement are more likely to politically participate conditional on strong feelings of injustice. As it pertains to protest, we find that in the full sample of the survey, a sense of injustice moderates the relationship between proximal contact and participation. This is supportive of hypotheses 1 and 2, which anticipated that absent a sense of injustice, proximal contact would be negatively or not at all associated with participation (Figure 5). At the lowest level of the injustice scale, among those with proximal contact, the probability of protest is 10.7%. Among those without proximal contact, the probability of protest is 5.3%, and is statistically indistinguishable from those with proximal contact. In contrast, for those exposed to immigration enforcement, moving to the highest level of the injustice scale increases one's expected likelihood of protesting to 43.4 percentage points, compared to those without proximal contact and a strong sense of injustice, who have a predicted likelihood of participating of 12 percentage points. These differences are statistically significant (p < .01).

Figure 5. Pr(Protest) by PoI and race.

These patterns appear to hold descriptively among white and AAPI respondents. Among Latino and Black respondents, it appears that proximal contact amplifies the positive association between injustice and participation that exists irrespective of contact. This is suggestive of support for hypothesis 4, which expected that Black Americans may be mobilized even absent contact, and runs contrary to hypothesis 3, which expected that the injustice model would hold for both Latino and AAPI respondents. Yet, none of these relationships achieve statistical significance at conventional levels among any racial subgroup. This may be a function of statistical power (given that N = −400 for each of the racial subgroups), but triple interactions between proximal contact, a sense of injustice, and race also do not yield substantively or statistically meaningful results.

We subject these relationships to further analysis that accounts for geographic context. We integrated several contextual measures that may be associated with proximal contact in order to validate the use of self-reported proximal contact, which we note above. These measures include county-level removals through Secure Communities, the proportion that are felony criminal removals, the proportion of non-citizens at the zip-code level, and whether one lives in a state with particularly punitive immigration policies. Conditioning on these contextual variables does not substantively alter the conclusions presented here. Likewise, interacting contextual-level variables with proximal contact, a sense of injustice, or an interaction employing all three terms does not yield additional insight. The full analysis of geographic context is located in Section 10.3–10.5 of the Appendix. This could be a consequence of too few respondents in any given geographic unit to conduct appropriate hierarchical analysis. It could also reflect the importance of relational ties, not captured by contextual measures of enforcement, to shaping political outcomes. Local context potentially shapes the extent to which one has proximal contact, whether that contact is viewed as systemically unjust, and whether individuals take the risk of politically engaging as a consequence. Investigating the role of geographic context is an important inquiry, but is beyond the scope of the present analysis. Suffice it to say that subjecting proximal contact relationally conceived to additional analysis through the inclusion of geographic factors lends support for our overall conclusions.

Finally, in addition to the multivariate regression models presented here, we also employ nearest-neighbor matching to reduce model dependency and acquire balance on observed baseline covariates as an additional robustness check.Footnote 21 Under the matching framework, the results are relatively similar (Table 3), if not stronger from a substantive standpoint. Proximal contact is associated with a 24 percentage point increase in the probability of protesting or demonstrating, and the correlation is statistically significant. The second model assesses if PoI continues to have a moderating effect after matching. This appears to be the case, where an increase on the PoI scale increases the marginal effect of proximal contact by .02 (p < .10). The third model also conducts a balance test, regressing treatment status (proximal contact) on the set of covariates that determined the matching algorithm. There is no imbalance after the matching procedure, allowing for a simple bivariate test of the effects of proximal contact on self-reported protest behavior.

Table 3. Post-processed model + balance test

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We began with the question: Does proximal contact with immigration enforcement impact political participation? Given the empirical evidence, the answer is yes, with qualifications. First, proximal contact motivates non-traditional forms of political participation (protesting/demonstrating), but not voting. These results are consistent with previous work that finds that contact with punitive bureaucratic institutions do not change rates of voting (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Huber, Meredith, Biggers and Hendry2015; Israel-Trummel and Shortle Reference Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán Reference Street, Jones-Correa and Zepeda-Millán2017), even as they may compel participation in other forms of non-voting behavior (Israel-Trummel and Shortle Reference Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; Street, Jones-Correa, and Zepeda-Millán Reference Street, Jones-Correa and Zepeda-Millán2017; Walker Reference Walker2014).Footnote 22 Given the data, it is unclear why proximal contact and a sense of injustice are not associated with voting, but it may be due to the method, where self-reports of voting (intent to do so and actually having done so) are threatened by social desirability bias. It could also be that the underlying motivations to vote differ from those to engage in other types of activities, where proximal contact with immigration enforcement compels political organizing around issues related to immigration policies, not politics in general (Walker Reference Walker2014).Footnote 23

Ours is the first analysis to examine the impact of proximal contact in the area of immigration enforcement on political participation. Previous research has examined the phenomena of having undocumented parents, worrying about the deportation of someone in one's network, and having proximal contact with criminal justice more generally. Our findings, that proximal contact is associated with increased protest behavior but not voting, are in keeping with those derived from these closely related and overlapping experiences. A growing body of work demonstrates that the political lessons learned from interactions with punitive institutions extend to those on the periphery of those interactions. We find that this holds in the area of immigration enforcement, and that proximal contact with immigration enforcement functions in ways similar to proximal contact with policing more generally with respect to participation outcomes.

We further sought to examine the extent to which the relationship between proximal contact and participation varies among racial subgroups. We found that the positive association between proximal contact and protest behavior extends beyond Latinos to likewise impact Black, Asian, and White Americans. This represents a significant contribution to existing literature insofar as research on the impact of immigration enforcement on participation primarily examines the behavior of Latinos, and research in the area of criminal justice compares whites to Blacks or groups non-whites. Ours is the first to bring the four largest racial subgroups in the United States into conversation with one another. Moreover, that proximal contact impacts participation for all groups under study suggests an underlying mechanism that is closely related to a politicized racial identity, but which does not quite map on to theories of group consciousness or ethnic solidarity.

We turn to research on criminal justice, evaluations of institutional legitimacy, and their consequences for civic and political behavior for insight. Theories of procedural justice instead direct scholars to examine evaluations of the fairness of the institution under study rather than one's racial identity. To do this, we draw on Walker (Reference Walker2016)'s injustice index developed to assess the criminal justice system, and examined the moderating effect of injustice on the relationship between proximal contact and participation. We found support for the idea that a sense of injustice around immigration enforcement underlies the positive association between proximal contact and protest behavior among the full sample. Those without a strong sense of injustice appear to not be motivated to participate politically in response to proximal exposure to immigration enforcement, suggesting that they may believe that the enforcement apparatus behaved in an appropriate manner that does not warrant a political response.Footnote 24

A number of caveats attend the findings presented here. This paper demonstrates the importance of delineating between plausible individual-level mechanisms that motivate political behavior in response to proximal contact with punitive institutions. Nevertheless, a shortcoming of the analysis is the inability to test alternative explanations, such as perceived discrimination, group consciousness, or linked fate. Instead, we rely on past research and the underlying theoretical conceptions of each, which require membership with one's racial group for the political psychological mechanism to work to promote change in attitudes and behavior. Future work should endeavor to discriminate between a sense of injustice and other individual-level psychological mechanisms that may generate political action in response to immigration enforcement.

Second, although this paper is the first in the area of immigration to compare racial and ethnic groups with large, representative samples, our analysis still suffers from low power. This limitation is exacerbated by our theoretical interest in heterogeneous treatment effects across the distribution of perceived injustice. Future work should prioritize examining differences among racial subgroups in more methodologically principled ways. The tendency to focus on whites versus Blacks or non-whites, or to examine racial subgroups in isolation obscures the unique histories with and relationships to law enforcement that may yield important theoretical insights about the nature of the use of force by the state.

Future work, moreover, should pay stronger attention to causality. For instance, it could be the case that those who already view immigration enforcement as unjust are both more likely to reveal that they have had personal or proximal contact with the system, and to engage in protest behavior. We do our best to account for these possibilities through the use of matching and employing an analysis of sensitivity to omitted variable bias. However, we cannot be certain that we have accounted for all unobserved confounders. Therefore, future work should focus on making apples-to-apples comparisons between individuals exposed to immigration enforcement and those who are not exposed yet operate in the same context and possess the same baseline characteristics. Finally, research in both immigration enforcement and criminal justice should continue to make cross-disciplinary connections. Criminal justice and immigration enforcement are intimately linked. Most tellingly, for example, anti-immigration policy at the federal, state, and local levels often explicitly deputizes local law enforcement agencies to carry out federal efforts to detain and deport migrants. Moreover, immigration officials apply the same set of strategies, designed to predict, preempt, and track potential violators, employed by law enforcement more generally that serves to target individuals based on race, ethnicity, geographic location, and language. Continuing to chart the linkages between criminal justice and immigration enforcement promises to reveal the specific technology of what some have termed, The New Jim Crow.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2020.9.