Introduction

Crustaceans of the genus Artemia, also known as brine shrimps, inhabit saline and hypersaline aquatic environments and are a major component in the diet of flamingos and a number of other waders. During evolution a relationship between these birds, their cestodes and brine shrimps acting as intermediate hosts has been established. So far, larval stages of 17 species of the families Hymenolepididae (n = 11), Dilepididae (n = 4) and Progynotaeniidae (n = 2) have been found in brine shrimps (Schuster, Reference Schuster2018). The role of brine shrimps as intermediate hosts for avian cestodes was examined in Mono Lake in California (Young, Reference Young1952), in the Great Salt Lake in Utah (Redón et al., Reference Redón2015b), Tengiz Lake in Kazakhstan (Maksimova, Reference Maksimova1973, Reference Maksimova1977, Reference Maksimova1981, Reference Maksimova1986, Reference Maksimova1987, Reference Maksimova1988, Reference Maksimova1990, Reference Maksimova1991; Gvozdev and Maksimova, Reference Gvozdev and Maksimova1979), in the Camargue of France (Gabrion and MacDonald, Reference Gabrion and MacDonald1980; Robert and Gabrion, Reference Robert and Gabrion1991), the Odiel Marshes and other salterns in Spain and Portugal (Georgiev et al., Reference Georgiev2005, Reference Georgiev2007, Reference Georgiev2014; Vasilieva et al., Reference Vasilieva2009; Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez2013; Redón et al., Reference Redón2011, Reference Redón2015a,Reference Redónc) and in saline lakes in Algeria (Amarouayache et al., Reference Amarouayache, Derbal and Kara2009). However, such studies had never previously been carried out in the Middle East, and therefore the aim of this paper is to describe the course of parasitism of cestode cysticercoids in brine shrimps in a hypersaline habitat in Dubai over a period of eight consecutive months.

Materials and methods

The habitat

The Godolphin lakes (25°10′31′′N, 55°15′47′′E) in Al Quoz district of Dubai, covering a territory of approximately 2.5 and 2.9 ha, respectively, were created as satellite wetland to attract charadriiform birds. The principles of the lake construction were to dig down to the natural groundwater level, leaving several areas of high ground to form islands as breeding territory for the flamingos and other native shore birds. Hypersaline wells (240 ppt salinity) diluted by treated sewage effluent to maintain the salinity at a level of 70–160 ppt were sources of water supply. In 1998, 17 pinioned greater flamingos (Phoenicopterus roseus) were provided for stocking at the Godolphin lakes. Prior to the introduction of these birds, cysts of Artemia franciscana were distributed among the water body. Adult brine shrimps started to occur in October/November and remained until the water temperature rose above a critical limit of 35°C in June/July of the following year. Shrimps regained life from deposited dry resistant eggs when temperatures fell in autumn. Apart from brine shrimps, birds were also provided with pellets. Up to 250 greater flamingos were regular visitors when the Artemia population was blooming in late winter and spring. Other bird species frequently seen in the habitat were redshank (Tringa totanus), greenshank (Tringa nebularia), common sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos), Terek sandpiper (Xenus cinereus), ringed plover (Charadrius hiaticula), avocet (Recurvirostra avosetta), bar-tailed godwit (Limosa lapponica), common snipe (Gallinago gallinago), red-wattled lapwing (Vanellus indicus) and little grebe (Tachybaptus ruficollis). In terms of biomass predating brine shrimps at times of bloom, occasional huge flocks of shovelers (Anas clypeata) could be seen capitalizing on the seasonal abundance in spring. These flocks can comprise several hundred individuals. Teal (Anas crecca) are also observed in small numbers. Another sporadic visitor, present occasionally but in large numbers during winter months, is the black-headed gull (Larus ridibundus), which can be seen exhibiting feeding behaviour when the Artemia population is in full bloom.

Examination of brine shrimps

Our investigations were carried out at the Central Veterinary Research Laboratory in Dubai between November 2015 and June 2016. At monthly intervals, shrimps were caught by 0.5 mm mesh sweep net and brought to the laboratory, where the crustaceans were killed in boiling water. Randomly selected adult male and female Artemia, in numbers between 202 and 283, were placed in a drop of glycerin on a slide and covered with a cover slip. Glycerin cleared the body content, making helminth development stages visible. Microscopic examination of the slides was carried out at low magnification (40×). Positive shrimps were then dismantled and cysticercoids were studied in a drop of glycerin at higher magnification (100–600×). The cestode larval stages were determined based on colour, shape and size of the cysts; number, shape and length of rostellar hooks; and presence or absence of spines or hooklets on suckers. The total number of host specimens examined during the eight-month investigation period was 1840.

Statistical analysis

Number and species composition of cysticercoids were noted in each individual male and female crustacean, and were recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Prevalence and mean intensity of cysticercoids in shrimps at their 95% lower and upper confidence intervals were calculated using the software package Quantitative Parasitology 3.0 (QP WEB) (Rozsa et al., Reference Rozsa, Reiczigel and Majoros2000).

Temperature data

The mean weekly temperatures between October 2015 and July 2016 measured at Dubai International Airport (15 km from the sampling site) were obtained from the website https://www.wunderground.com/history/airport/OMDB (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Mean weekly temperatures in Dubai between October 2015 and July 2016.

Results

Of the 1840 shrimps examined, 1106 were female and 734 were male. There was always a surplus of 1 : 1.3 to 1 : 2.2 of females in the monthly collected samples except for the month of February, when males dominated slightly. In total, 663 (36.03%) crustaceans were found to harbour cysticercoids, in numbers between one and 16. In most of the catches, female specimens showed higher prevalence compared to males (table 1).

Table 1. Monthly and total prevalence and burdens of cysticercoids in male and female Artemia franciscana from Godolphin lakes in Dubai (95% CI: 95% confidence intervals; n.a.: not applicable, because only one cysticercoid was found in infected shrimps).

In catches between October and February, prevalence data were comparatively low and differed insignificantly. In March there was a distinct increase in numbers of infected hosts, which brought prevalence in male and female shrimps to 59.4 and 72.5, respectively. The highest prevalence and intensity in both sexes was found in May, with prevalence of 68.4 and 69.2%, respectively. A sharp drop of both parameters to 41.9 and 34.0% occurred at the end of the observation period, in June. No shrimps were available in the following months.

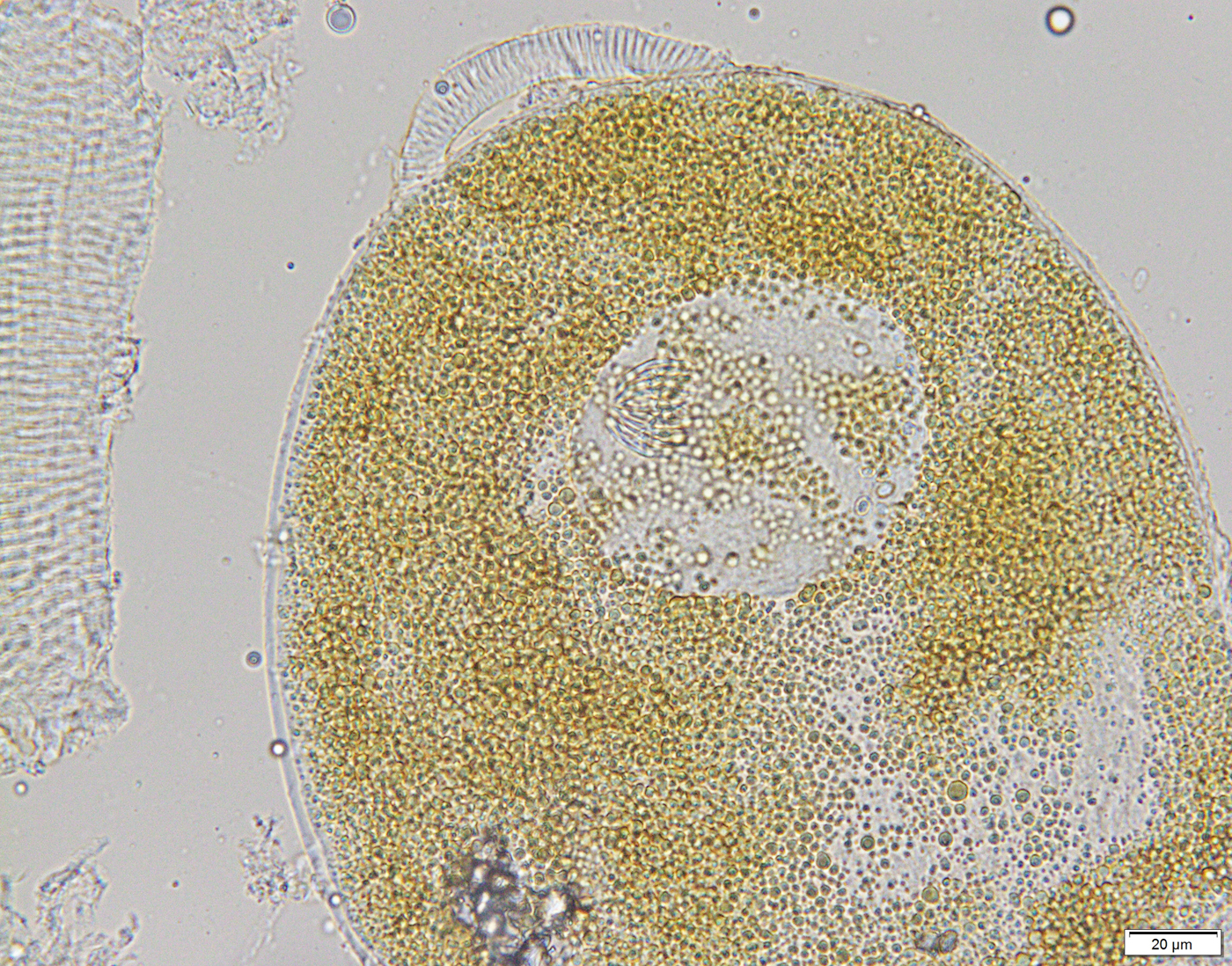

In total, cysticercoids of seven cestodes were identified. These were Flamingolepis liguloides (fig. 2), F. flamingo (figs 2 and 3), Wardium stellorae (fig. 4) and Confluaria podicipina (fig. 5) of the Hymenolepididae family, Eurycestus avoceti (fig. 6) and Anomotaenia tringae (fig. 7) of the Dilepididae family, and Gynandrotaenia stammeri (fig. 8) of the Progynotaeniidae family.

Fig. 2. Female Artemia franciscana, with two Flamingolepis liguloides (big cysts) and one Flamingolepis flamingo (small cyst) located in the thorax.

Fig. 3. Cysticercoid of Flamingolepis flamingo. This cysticercoid possesses an extremely long, thin cercomer.

Fig. 4. Cysticercoid of Wardium stellorae.

Fig. 5. Cysticercoid of Confluaria podicipina. The cysticercoid is surrounded by a thick capsule and possesses a long cercomer.

Fig. 6. Cysticercoid of Eurycestus avoceti mechanically freed from the brown capsule that surrounds the cysticercoid. The suckers are armed with small hooklets.

Fig. 7. Cysticercoid of Anomotaenia tringae. The cysticercoid is surrounded by a brown capsule.

Fig. 8. Cysticercoid of Gynandrotaenia stammeri. The suckers are armed with spines.

Both representatives of the genus Flamingolepis were the most frequently occurring species, and occurred in all monthly catches. A total of 465 crustaceans harboured F. liguloides cysticercoids in numbers between one and ten. The prevalence of F. liguloides varied insignificantly between 3.1 and 8.7% during the first four months of investigation, with a maximum burden of two cysticercoids (table 2). A marked increase of infected shrimps to 46.5% was noticed in March, while in April the prevalence dropped slightly to 34.1%, to reach a maximum value of 63.0% in May. At the end of the observation period, in June, 30.4% of A. franciscana were found to harbour F. liguloides cysticercoids. High burdens of F. liguloides, of five to ten, were seen between March and June.

Table 2. Monthly and total prevalence and intensity of Flamingolepis liguloides in Artemia franciscana collected from Godolphin lakes in Dubai between November 2015 and June 2016 (95% CI: 95% confidence intervals; n.a.: not applicable, because only one cysticercoid was found in infected shrimps).

Flamingolepis flamingo was detected in 196 brine shrimps, in numbers between one and four. Its initial prevalence in November amounted to 10.3% and varied between 2.7 and 5.3% in the following three months, to reach a maximum of 20.3% in March (table 3). The percentage of infected shrimps decreased in April and May, to 15.2 and 15.4%, respectively. At the end of the observation period, the prevalence decreased further to 10.6%.

Table 3. Monthly and total prevalence and intensity of Flamingolepis flamingo in Artemia franciscana collected from Godolphin lakes in Dubai between November 2015 and June 2016 (95% CI: 95% confidence intervals; n.a.: not applicable, because only one cysticercoid was found in infected shrimps).

Of 82 brine shrimps infected with E. avoceti cysticercoids, 71 were collected in March, April and May, when prevalence amounted to 10.9, 8.1 and 12.2%, respectively. The parasite was not detected in samples collected in November and February (table 4).

Table 4. Monthly and total prevalence and intensity of Eurycestus avoceti in Artemia franciscana collected from Godolphin lakes in Dubai between November 2015 and June 2016 (95% CI: 95% confidence intervals; n.a.: not applicable, because only one cysticercoid was found in infected shrimps).

Wardium stellorae infections were diagnosed in 58 shrimps (3.2%), in numbers between one and two cysticercoids, and only between January and June. Most of the Wardium-infected shrimps (n = 50) originated from catches in March and April.

Thirty-one crustaceans (1.7%) contained cysticercoids of G. stammeri. The parasite was detected between January and June, with an intensity of one to two.

Single cysticercoids of A. tringae were found in five shrimps in March. A further finding of 10 cysticercoids in one host was made in May.

A single larval stage of C. podicipina was detected in one brine shrimp in April only.

A total of 510 crustaceans contained one species. Infections with two, three and four species were recorded in 135, 17 and two shrimps, respectively (table 5). The most frequent multiple infections were F. liguloides and F. flamingo (n = 50), F. liguloides and E. avoceti (n = 29), F. liguloides and W. stellorae (n = 23), and F. liguloides and G. stammeri (n = 11). Infections with one and two parasite species occurred in all monthly catches, whereas infections with three and four species were noticed only between March and May.

Table 5. Combination of cestode species in multiple infections of Artemia franciscana from Godolphin lakes of Dubai.

Discussion

Under normal conditions, female A. franciscana are ovo-viviparous, and nauplius larvae usually hatch immediately after placement of eggs, whilst unfavourable conditions (low oxygen, rising temperatures, desiccation of pools) lead to the production of floating, thick-shelled, metabolically inactive brown cysts that can survive for up to two years in dry conditions and hatch when hydrated under optimal conditions (Van Strappen, Reference Van Stappen, Lavens and Sorgeloos1996). This was the case in the examined habitat. During summer months, water levels in the Godolphin lakes were low, and due to high temperatures brine shrimps died out; however, they regained life after replenishment in September. First adult specimens were observed in October and sufficient numbers of adult crustaceans were later available for a period of eight months. In a study on water quality and the brine shrimp population in the Al Wathba Lake of Abu Dhabi, the closest Artemia biotope, at a distance of 120 km, adults of A. franciscana occurred in November and were present until June (Al Daheri and Saji, Reference Al Daheri and Saji2013).

Temperature and salinity are the most important physical factors for survival, growth and reproduction of Artemia spp. A number of experimental studies were carried out to investigate these parameters for different Artemia populations (Wear et al., Reference Wear, Haslett and Alexander1986; Browne and Wanigasekera, Reference Browne and Wanigasekera2000; Baxevanis et al., Reference Baxevanis2004; Agh et al., Reference Agh2008; Castro-Mejia et al., Reference Castro-Mejia2011). During the observation period, salinity in the Godolphin lakes was kept at relatively constant levels between 70 and 120 ppt. The temperature showed larger variation, starting with 29°C in November, dropping to a minimum of 17°C in January, and reaching 36°C at the end of the observation period, in June (fig. 1). The optimal temperature for most of the Artemia populations has been established at c. 25°C (Lenz and Browne, Reference Lenz, Browne, Browne, Sorgeloos and Trotman1991; Van Stappen, Reference Van Stappen and Abatzopoulos2002). Despite optimal physical conditions at the beginning of our observation, cysticercoid prevalence in examined shrimps was relatively low. Their presence probably resulted from infections of the previous month (October). Little experimental work was done to study the life cycle of cestodes in Artemia spp. under laboratory conditions; however, it took 12 to 15 days at a temperature of 22 to 24°C for the development of C. podicipina and Wardium gvozdevi in Artemia salina (Maksimova, Reference Maksimova1981, Reference Maksimova1988).

In autumn, the population of final avian hosts visiting the Godolphin lakes was still low, consisting mainly of pinioned greater flamingos. The cysticercoid prevalence remained at relatively low levels as temperature fell below optimal levels for the crustaceans, reducing their metabolism and food uptake. During the winter months numerous migrating birds, including flamingos, ducks and gulls, visited the ponds, contaminating the water with parasite development stages. Rising temperatures at the end of February increased the activity of brine shrimps again and led to a sharp rise in the number of infected shrimps in March, not only with flamingo-specific larval stages but also with E. avoceti, a cestode that infects avocets and other stilts, with W. stellorae, a tapeworm of gulls, and with A. tringae, which occurs in sandpipers. The percentage of infected brine shrimps decreased slightly in April, reaching maximum values in May. Multiple infections with three and four cestode species were found between March and May at the peak of invasion. The sharp decrease in infected shrimps in June can be explained by stress due to high water temperatures, which led to die-off of heavily infected specimens. Also, there were fewer new infections, because of decreased contamination, as migrating birds and other winter guests had left the habitat. The explanation for increased cysticercoid prevalence in females could be a higher demand for nutrients, related to the production of offspring, and thus a more frequent intake of cestode eggs.

The frequency of cestode species in the examined crustaceans reflects the presence of certain final hosts in the habitat. Flamingos were present permanently and occurred in large numbers during winter months and early spring. This explains the high prevalence of F. liguloides and F. flamingo. Eurycestus avoceti cysticercoids were present in a higher prevalence between March and May, coinciding with the presence of sandpipers. Large flocks of gulls were seen in the late winter months, which were responsible for contamination with W. stellorae.

Artemia franciscana is a native species of North America and is a neozoan species in Europe, Asia and Australia. It is believed to be a major threat to biodiversity of hypersaline wetlands in Mediterranean areas (Amat et al., Reference Amat2005, Reference Amat2007). In addition, Georgiev et al. (Reference Georgiev2007) and Redón et al. (Reference Redón2015a) showed that A. franciscana is much less infected by cestode cysticercoids than the two native species, A. salina and A. parthenogenetica, in the same region. Sánchez et al. (Reference Sánchez2012) examined the infection rates in invasive and native Artemia species in the conditions of sympatry and reported similar results. Our results, however, showed higher prevalence and intensities of cysticercoids in A. franciscana compared to previous publications. One of the reasons for this could be the relatively small size of the habitat and the relatively large number of final avian hosts. Examination of A. franciscana from one of the native habitats in Utah indicated a cysticercoid prevalence of 39.2%, with C. podicipina being the most prevalent species.

A comparable investigation showing seasonally varying infection rates was carried out by Redón et al. (Reference Redón2015a) in the Ebro Delta salterns in Spain. Examination of A. franciscana revealed a relatively low percentage of cysticercoid infections during winter months and high prevalence in summer, when temperature reached ambient values for the crustaceans. Also, in that study female shrimps showed a higher percentage of cysticercoid infection compared to males.

Author ORCIDs

S. Sivakumar https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8959-3532

K. Hyland https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9770-9651

R.K. Schuster https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7421-6777

Conflict of interest

None.