Introduction

Rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) was the first cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) to be developed (Dryden and Mytton, Reference Dryden and Mytton1999). Albert Ellis began to develop what we now know as REBT in the 1950s, preceding the other CBT approaches that emerged in the 1960s (Ellis, Reference Ellis2004b). The most influential CBT approach to emerge from the 1960s was that of Aaron Beck (Reference Beck1963, Reference Beck1964, Reference Beck1976), which is currently often referred to as mainstream CBT, cognitive therapy (CT) or Beckian CBT (Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007). Today, Beckian CBT (henceforth to be referred to as CT) is generally considered the psychotherapy with the largest evidence base (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck2006; Dobson and Dobson, Reference Dobson and Dobson2009). More recently, third wave CBT approaches have become a major focus in the CBT literature despite the fact that there is disagreement on which therapies to identify as ‘third wave’ (David and Hofmann, Reference David and Hofmann2013), and despite the fact that the theoretical underpinnings and evidence behind some of these therapies is far from solid (Hofmann and Asmundson, 2008; Öst, Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008; Churchill et al., Reference Churchill, Moore, Furukawa, Caldwell, Davies, Jones, Shinohara, Imai, Lewis and Hunot2013).

There is unfortunately little acknowledgement of REBT’s influence on all the CBT approaches that came after it (Ellis, Reference Ellis2004b; Velten, Reference Velten2007), and little awareness of the substantial evidence behind it (David et al., Reference David, Szentagotai, Eva and Macavei2005; David et al., Reference David, Lynn and Ellis2010). The magnitude of outcome research behind CT (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck2006) and the unfolding potential of third wave CBT (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Martins, Almeida and Silva2017) explains their popularity among psychotherapy practitioners and researchers – but far from enough to warrant the manner in which they have outshined REBT in the literature. Ellis (Reference Ellis2001) explored in depth his views on why REBT tends to be marginalized in the literature by examining issues such as his own personal part in this (e.g. highly liberal views on sex, use of foul language to make a point, etc.), the relative lack of outcome research behind REBT, and the notion that REBT can be viewed as outdated simply because it has been around since the 1950s.

Despite being very much a proponent of REBT, and having had great success in applying it to unconventional psychological problems (Al-Roubaiy, Reference Al-Roubaiy2012), I believe REBT has some limitations. However, rather than abandon REBT for other approaches when confronted with these limitations, I chose to incorporate other CBT approaches into my REBT practice to make up for these limitations. I have been using and refining this integrative model in my own clinical practice for the past six years. Based on Norcross’ (Reference Norcross, Norcross and Goldfried2005) classifications of psychotherapy integration, I call this model assimilative integrative rational emotive behaviour therapy.

In this paper, I plan to first explore the limitations of CT and third wave therapies. The objective is not to undermine these CBT approaches, but rather to justify the manner in which I will propose incorporating them into an integrative model later on. After dispelling the mythical superiority of CT and highlighting the limitations of third wave CBT approaches, I plan to demonstrate why REBT is the most theoretically comprehensive CBT approach to date. I will then explore some limitations in REBT theory to justify the proposal of an integrative model that would remedy these limitations by incorporating other CBT approaches into the REBT framework. Psychotherapy integration will then be briefly explored in terms of value and relevance. Finally, I will introduce the integrative model, and demonstrate its use through a brief exploration of a clinical case example from my own practice.

Limitations of cognitive therapy

Aaron Beck (Reference Beck1963, Reference Beck1964) introduced cognitive therapy as a new psychiatric hypothesis which conceptualized depression as a disorder of thinking as well as affect as opposed to the earlier psychiatric conceptualization of depression as simply a disorder of affect. Beck (Reference Beck1976) went on to introduce his content-specificity hypothesis which states that each emotional disorder can be characterized by cognitive content specific to that disorder. CT therapy encourages clients to become aware of the content of their distorted thoughts/cognitions as well as the maladaptive behaviours that might be maintaining a problem. Cognitions are generally classified into negative automatic thoughts, dysfunctional assumptions and core beliefs. Negative automatic thoughts are thoughts or images that occur spontaneously when a person is engaging in negative/distorted appraisals or interpretations in certain situations. Dysfunctional assumptions and core beliefs, on the other hand, are more global and general in nature. Core beliefs or unconditional beliefs are general and absolute statements about the self, others, or life (e.g. ‘I am worthless’, ‘people can’t be trusted’), whereas dysfunctional assumptions or conditional beliefs take the form of if…then theories framed as ‘should’ or ‘must’ statements [Westbrook et al. (Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007), pp. 7–8]. Dysfunctional assumptions in CT are very similar to irrational beliefs in REBT (e.g. ‘I must never fail’, ‘people should be nice to me’).

CT is a highly structured, time-limited and empirical approach that utilizes several methods such as guided discovery, behavioural experiments and exposure to bring about therapeutic change (Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007). In tailoring CT techniques to different types of psychopathology, CT proponents were able produce an abundance of outcome research to support the efficacy of CT for a variety of specific and distinct psychological problems (Dobson and Dobson, Reference Dobson and Dobson2009). For example, in a review of 16 meta-analytic studies, Butler et al. (Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck2006) found large controlled effect sizes for CT for unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder and childhood depressive and anxiety disorders, and medium controlled effect sizes for CT of chronic pain, childhood somatic disorders, marital distress and anger.

The evidence base behind CT utilizes randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as the main research tool, which are often regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for treatment efficacy studies (Arean and Kraemer, Reference Arean and Kraemer2013). The highly structured and manualized nature of CT allowed for the extensive use of RCTs to generate support for CT (Beutler, Reference Beutler2009; Chambless and Ollendick, Reference Chambless and Ollendick2001; Chapman, Reference Chapman2012). Simply put, RCT research involves randomly assigning participants to conditions in which they receive different treatments – under the assumption that any statistically significant difference to emerge between conditions can be attributed to the treatment (Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Christopher Muran, Angus, Hayes, Ladanay and Anderson2010). However, RCTs can only work with highly structured and manualized therapies, and the findings that they can generate can only provide a measure of a treatment’s efficacy, not effectiveness. As Ellis (Reference Ellis2004c, p. 86) notes: ‘When used in an outcome study, the more rigorously manualized a form of therapy is, the less likely, I suspect, it will accurately represent what regular therapists do with that form of therapy’.

Additionally, RCT research fails to consider the impact of common factors (e.g. therapeutic relationship) on outcome (Chapman, Reference Chapman2012; Wampold, Reference Wampold2001). Furthermore, real psychotherapy does not always reflect the protocols that practitioners claim to adhere to, and as Ellis (Reference Ellis2004a, p. 27) notes: ‘Practically all therapists are remarkably different and individualistic in following the form of therapy they claim to practise’. Thus, the very manualized and structured nature of CT, which has allowed it to accumulate so much outcome research, is also one of its major weaknesses as it fails to account for the multi-dimensional complexity of real psychotherapy practice. As Westbrook et al. (Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007, p. 13) note: ‘the evidence for some of the fundamental theoretical ideas of CBT is more patchy than the evidence for the treatment’s efficacy’.

Another limitation in CT lies in its almost exclusive focus on tackling faulty appraisals of reality (or cognitive distortions) as opposed to tackling the beliefs underlying the disturbance/distress. CT tends to focus on distortions of reality in the form of negative automatic thoughts (NAT), which are then linked to the consequent emotional distress and maladaptive behaviour. Beliefs are incorporated in CT but are rarely attended to, as the focus of CT is often on the distortions of reality at the NAT level. Working with the underlying dysfunctional beliefs is rarely a central concept in CT, and CT formulations – that tend to involve feedback loops and safety behaviours among other concepts – rarely incorporate beliefs in the same manner as other approaches such as schema therapy (Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007). This focus on the NAT level limits the exploration of why these NATs are so distressing in the first place, irrespective of whether they represent accurate reflections of reality or distortions of reality. Beckian CT has dysfunctional assumptions and core beliefs, which are similar to REBT’s rational/irrational beliefs; however, as Westbrook et al. (Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007, p. 9) note: ‘Most successful CBT research to date targets NATs’.

For example, for the socially anxious person the pre-occupation with people’s perception of him/her and the possibility of criticism and scrutiny from them lies at the heart of his/her condition. Exploring such a person’s NATs as they enter a social setting can help them to challenge some of the faulty reasoning behind these NATs and can certainly equip such a person with more realistic appraisals in the future. When combined with tackling avoidance and safety behaviours, CT can be very effective in helping such a client overcome his/her social anxiety due to faulty reasoning and cognitive distortions. However, unlike REBT, CT will not tackle head-on the irrational need for acceptance by others (e.g. disputing the irrational beliefs of ‘I must be accepted by others’ and ‘I cannot stand being rejected/criticized by others’). As Westbrook et al. (Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007, p.62) note: ‘almost all the evidence currently available for the effectiveness of CBT is based on working primarily at the level of specific automatic thoughts and their associated behaviours’.

Another problem with CT’s focus on faulty appraisals of reality is that it can potentially invalidate the client’s experiences as questioning the validity behind a client’s perspective can be experienced as implying that ‘you are just imagining this’ or ‘you are exaggerating’. This can be especially problematic when working with clients from marginalized and minority groups whose main presenting problems are psychosocial stressors such as lack of social support, acculturative stress and societal racism (Al-Roubaiy et al., Reference Al-Roubaiy, Owen-Pugh and Wheeler2013, Reference Al-Roubaiy, Owen-Pugh and Wheeler2017). Even if a therapist manages to establish a good working alliance with such a client without somehow invalidating their experiences, CT offers very little in dealing with real psychosocial adversity. For example, biased scanning of social settings by an ethnic minority client continuously looking for racists will cause such a client to perceive a place as full of racists when in fact there might be few or no racists there. Such a client is likely to benefit from CT because he or she needs to understand that his or her perception of a place being full of racists is not rooted in reality. However, what if that place was really full of racists: how can CT address that? Unlike REBT, it cannot (Al-Roubaiy, Reference Al-Roubaiy2012).

However, it should be noted that CT’s utilization of behavioural experiments (BEs) to dispute and correct dysfunctional assumptions and core beliefs is a major component and highly potent ingredient in CT (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackman, Mueller and Westbrook2004; Clément et al., Reference Clément, Lin and Stangier2019). In addition to testing out and changing dysfunctional assumptions/beliefs, BEs contribute to the modification of the underlying cognitive processes that are maintaining the problem (Clark, Reference Clark, Crozier and Alden2001). For example, McMillan and Lee (Reference McMillan and Lee2010) found evidence that BEs focusing on safety behaviours, video feedback and attention manipulation are more effective in the treatment of social anxiety than traditional exposure which mainly focuses on achieving habituation. However, this is not unique to CT because REBT uses behavioural techniques to dispute irrational beliefs as well. REBT clients, for example, can be ‘encouraged to carry out behaviours they consider shameful and embarrassing in public’ (Dryden and Mytton, Reference Dryden and Mytton1999, p. 128) – thereby challenging and changing irrational beliefs such as: ‘I cannot stand to be embarrassed’, ‘I must always be admired by others’ and ‘it would be awful if people thought less of me’.

Taking into account the almost exclusive reliance on RCTs to support the efficacy of CT not its effectiveness; the literature on common factors in psychotherapy and the difficulty in knowing the exact active ingredients responsible for causing the observed therapeutic change; the mismatch between how real psychotherapy looks like versus the highly manualized treatment protocols of CT; the fact that most of the evidence behind CT is limited to negative automatic thoughts and associated behaviours as opposed to the underlying irrational/dysfunctional beliefs; and the problem with focusing almost entirely on faulty appraisals of reality, one can easily see why CT is far from perfect with several clear limitations in theory and practice.

Limitations of third wave CBT

Third wave CBT is primarily represented by acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) since the founder of ACT (Hayes, Reference Hayes2004; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006) started referring to his approach as well as others – such as dialectic behaviour therapy (DBT; Linehan, Reference Linehan1993) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., Reference Segal, Williams and Teasdale2001) – as representative of this third wave revolution. It is important to note that ‘none of the authors of these treatments consider themselves to be part of this third wave movement’ (David and Hofmann, Reference David and Hofmann2013, p. 116). Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006) suggest that CBT can be divided into three generations: traditional behaviour therapy, CBT and the third generation. In promoting ACT, some of its founders (Eifert and Forsyth, Reference Eifert and Forsyth2005; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999; Hayes, Reference Hayes2005) tend to compare ACT with other CBT approaches with a specific focus on presumed weaknesses in these second wave approaches. However, as Hofmann and Asmundson (Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008, p. 2) note: ‘many of these presumed weaknesses of CBT are based on incorrect perceptions about the nature of CBT’.

The general goals of ACT are to foster acceptance of unwanted thoughts and feelings, and to stimulate action tendencies that contribute to an improvement in circumstances of living (Eifert and Forsyth, Reference Eifert and Forsyth2005; Hayes, Reference Hayes2005). More specifically, ACT discourages experiential avoidance (i.e. the unwillingness to experience negatively evaluated feelings, physical sensations and thoughts). There are differences between ACT and CT in the way therapy deals with cognitions. In contrast to CT, ACT does not distinguish between overt behaviours, emotions and cognitions; instead, it subsumes cognitions under the more general term ‘behaviour’ as it is used in behaviour analysis. Therefore, in ACT, behaviour is used ‘as a term for all forms of psychological activity, both public and private, including cognition’ (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006, p. 2). Another major difference between CT and ACT is ACT’s focus on the function of cognitions as opposed to content.

Cognitive function is targeted in ACT by encouraging clients to accept disturbing cognitions and emotions without attempting to change their actual content. ACT views the core of many problems to be rooted in the acronym FEAR, and it employs six core principles to help clients develop psychological flexibility: cognitive defusion, acceptance, mindfulness, observing self, values, and committed action (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999; Hayes, Reference Hayes2005). Mindfulness in itself is a very important concept that we will return to later in this section as it forms the basis for several other third wave therapies. Simply put, acceptance through the use of mindfulness and other ACT techniques is emphasized in ACT as a new and novel revolutionary concept in CBT literature (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006, p. 3) when in fact REBT has been incorporating acceptance into therapy since the 1950s (Ellis, Reference Ellis2005).

ACT also insists that clients have to accept unpleasant emotions even if these distressing emotions are simply the product of faulty reasoning and irrational beliefs. ACT has no answer as to why we have to accept these distressing emotions when there are ways of challenging and changing the cognitions that caused the distressing emotions in the first place. Furthermore, ACT offers very little to clients with perfectionist tendencies and harsh/critical self-talk who are likely to upset themselves about falling short of mastering the concepts they are learning in therapy. As Ellis (Reference Ellis2005, p. 162) notes: ‘Since ACT doesn’t consciously look for, find, and actively dispute clients’ dysfunctional musts about their own therapeutic efforts, I would say that it omits one of the most useful therapeutic methods’.

Another point to consider is that CT and REBT promote adaptive antecedent-focused emotion regulation strategies, whereas ACT promotes response-focused emotion regulation strategies. The cognitive restructuring techniques used in CT, and the disputing of irrational beliefs in REBT, are in line with the antecedent-focused emotion regulation strategies, providing skills that are often effective in reducing emotional distress in similar future situations. Acceptance and mindfulness-based strategies, such as those used in ACT, are only useful for regulating distressing emotions after that which had occurred with little learning experience or change in thought process to avoid similar situations in the future. Research suggests that antecedent-focused strategies are relatively effective methods of regulating emotion whereas response-focused strategies tend to be counterproductive (Gross, Reference Gross1998; Gross and Levenson, Reference Gross and Levenson1997). So, in addition to the therapeutic limitations inherent in abandoning the focus on content of cognitions, the response-focused approach of ACT can actually be unhelpful to clients.

As it can be argued that ‘ACT remains the sole representative of this so-called third wave movement’ (David and Hofmann, Reference David and Hofmann2013, p. 116), I will not be exploring the limitations of other third wave therapies in depth for the purposes of this paper. I will, however, explore the limitations of mindfulness due to its centrality as a concept/intervention in third wave therapies. Kabat-Zinn took the word ‘mindfulness’ from Western Buddhism and created mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). He defined mindfulness as ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally’ (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn1994, p. 4). In manualizing mindfulness, Kabat-Zinn was able to carry out controlled outcome studies using psychological measures of change to create an evidence base for MBSR. This paved the way for others to incorporate mindfulness into their own therapies as Linehan (Reference Linehan1993) did in DBT, in which she uses mindfulness as a way of helping people with borderline personality disorder.

Segal et al. (Reference Segal, Williams and Teasdale2001) later adapted MBSR to create MBCT for the treatment of recurrent depression. Kabat-Zinn’s use of mindfulness in MBSR and the consequent flourishing of other mindfulness-based approaches within CBT can be traced back to two historical aspects according to Dryden and Sill (Reference Dryden and Sill2006) – the existence of a thriving but marginalized Humanistic movement in Western psychotherapy and the assimilation of Buddhist practices in psychotherapy. Both of these historical aspects paved the way for treating feelings and thoughts with the non-judgmental and accepting attitudes that are at the heart of both of these paradigms. Dryden and Sill (Reference Dryden and Sill2006) argue that these ideas were to a certain degree at odds with the scientific symptom-oriented approach, but they had a strong appeal to many people in applied psychology and psychotherapy. This appeal is understandable considering the growing evidence for mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), but it has also led to an excessive reductionism and commodification – appropriately labelled as ‘McMindfulness’ (Hyland, Reference Hyland2016).

It is precisely this over-emphasis on the value and applications of mindfulness that has come to be one of its defining limitations. This excessive focus and exaggerated claims of mindfulness applications can be traced back to the concept’s origins in Western psychotherapy, not just to the recent rise in its popularity. For example, Kabat-Zinn (Reference Kabat-Zinn1990, p. 24) argues that ‘If you experience you can just take in your experiencing. If you think about it, you disturb your direct experience of that moment’. However, as Ellis (Reference Ellis2006, p. 64) notes: ‘REBT wonders whether there is such a thing as direct experience of a sunset (or anything else) without some thought, purpose, and intention’. Similarly, Kabat-Zinn (Reference Kabat-Zinn1990, p. 29) states that ‘We practice mindfulness by remembering to be present in all your waking moments’ (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn1990, p. 29). However, ‘Being mindful all the time goes counter to the fact that our thoughts, feelings, and actions often are designed to switch themselves to non-mindful reactions and habits’ (Ellis, Reference Ellis2006, p. 67). In addition to the problems of exaggeration and excessive application of mindfulness, some research has found mindfulness to be harmful in some cases.

For example, Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Mickes, Stolarz-Fantino, Evrard and Fantino2015) examined the effect of mindfulness meditation on false-memory susceptibility in three experiments and consequently found clear evidence for the unintended consequence of mindfulness meditation in which memories become less reliable. Similarly, a cross-sectional study on the effects of intensive and long-term meditation reported that over 60% of individuals had at least one negative effect which varied from increased anxiety, depression and full-blown psychosis (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro1992). In yet another example, Dobkin et al. (Reference Dobkin, Irving and Amar2012) found that after an 8-week MBSR course, some participants experienced increased stress and depression. In another experimental study, which used the Trier Social Stress Test, Creswell et al. (Reference Creswell, Pacilio, Lindsay and Brown2014) found that a short mindfulness intervention with healthy individuals led to increased biological stress when compared with an active control group. Simply put, individual differences in responding to mindfulness, including the potential for adverse effects, should be considered as a major limitation in theory and practice especially in light of the excessive applications and promotions of mindfulness in the literature.

As for the evidence base behind MBIs, the research remains inconsistent in many ways. For example, two meta-analyses disconfirmed the expectation that continuous practice would lead to cumulative changes, both in emotional-cognitive domains (Sedlmeier et al., Reference Sedlmeier, Eberth, Schwarz, Zimmermann, Haarig, Jaeger and Kunze2012) and in brain structure (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Nijeboer, Dixon, Floman, Ellamil, Rumak, Sedlmeier and Christoff2014). Similarly, when Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Crane, Barnhofer, Brennan, Duggan, Fennell and Russell2014) compared MBCT with both cognitive psychological education (CPE) and treatment as usual (TAU) in preventing relapse to major depressive disorder (MDD) in people currently in remission, they found, among other things, no significant advantage in comparison with an active control treatment and usual care over the whole group of patients with recurrent depression. In another example, a recent comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized trials (Goyal et al., Reference Goyal, Singh, Sibinga, Gould, Rowland-Seymour, Sharma, Berger and Haythornthwaite2014) showed that mindfulness interventions led to: (1) only moderate improvements in depression, anxiety and pain; (2) very small improvements in stress reduction and quality of life; (3) no effect on positive mood, attention, sleep or substance use; and (4) no better outcome than physical exercise and relaxation.

The research behind most third wave therapies seems to be as inconsistent as the research on mindfulness. For example, Hunot et al. (Reference Hunot, Moore, Caldwell, Furukawa, Davies, Jones, Honyashiki, Chen, Lewis and Churchill2013) reviewed three studies, involving a total of 144 people. The studies examined two different forms of third wave CBT, consisting of ACT (two studies) and extended behavioural activation (BA) (one study). All three studies compared these third wave CBT approaches with CBT. The results suggested that third wave CBT and CBT approaches were equally effective in treating depression. However, the quality of evidence was considered by Hunot et al. (Reference Hunot, Moore, Caldwell, Furukawa, Davies, Jones, Honyashiki, Chen, Lewis and Churchill2013) to be of too low quantity and quality to draw conclusions from. Similarly, Öst (Reference Öst2008) explored the efficacy of several third wave therapies through a systematic review of RCTs including ACT, DBT, cognitive behavioural analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) and integrative behavioural couple therapy (IBCT). In total, there were 13 RCTs both in ACT and DBT, one in CBASP, and two in IBCT. Öst (Reference Öst2008) concluded that the third wave treatment RCTs used a research methodology that was significantly less stringent than CBT studies; that the mean effect size was moderate for both ACT and DBT; and that none of the third wave therapies fulfilled the criteria for empirically supported treatments.

Taking into account the theoretically flawed criticisms of CT that ACT founders expressed in promoting ACT; the false assumption that acceptance is a new concept in western psychotherapy when in fact it has been around since the 1950s as a central concept in REBT; the limitations inherent in abandoning the focus on content of cognitions; the problems inherent in the response-focused approach of ACT; the excessive reductionism and commodification of mindfulness (McMindfulness); the studies that show how mindfulness can actually be harmful for some clients; and the limited, inconsistent, and low quality research behind MBIs and third wave CBT, one can easily see that third wave therapies, despite being very promising, are far from being equal to or better than older and more established therapies such as CT and REBT.

REBT’s comprehensiveness

REBT is rooted in the philosophy that people are not disturbed by events per se, but by the beliefs they have of these events (Epictetus, cited in Ellis, Reference Ellis1962). This philosophical stance is the basis for all REBT interventions because the focus of therapeutic change is on the irrational beliefs (IBs) which the client might hold about what he/she is experiencing (A). It is these IBs that are responsible for the consequent (C) dysfunctional emotions and maladaptive behaviours that many people assume are caused by the negative activating events or adversity (A) they experience in life. According to REBT we are all prone to developing IBs which are responsible for many of the unhealthy Cs that people can display (i.e. the maladaptive/destructive behaviours and psychological problems such as anxiety and depression). As Ellis (Reference Ellis2003, p. 205) notes, ‘human disturbance is contributed to by environmental pressures, including our childhood upbringing, but that its most important and vital source originates in our innate tendency to indulge in crooked thinking’.

REBT argues that the causes of unhealthy or maladaptive emotions and behaviours are irrational beliefs, to which we are all prone (Ellis, Reference Ellis1958, Reference Ellis1994). Therefore, the therapeutic dialogue in REBT is between two fellow sufferers where the therapist has the knowledge about REBT’s philosophy (i.e. the ABC model) and is attempting to help the client dispute (D) his/her irrational beliefs and exchange (E) them for the healthier/rational/effective alternatives (Ellis, Reference Ellis2004b, Reference Ellis2005, Reference Ellis2006). This aspect of REBT naturally lends itself to establishing a good working alliance as client and therapist are considered equals in collaborating on helping the client resolve his/her issues – with the simple difference in that the client is the expert on his/her internal world and the therapist is the expert on REBT. Despite objecting to Rogers’ (Reference Rogers1957) notion of the necessary and sufficient conditions for therapeutic change, Ellis (Reference Ellis2003, p. 204–205) acknowledges that effective therapists tend to, among other things: ‘unconditionally accept their clients’, ‘strongly believe that their main techniques will work’ and ‘freely refer to other therapists those they think they cannot help or are not interested in helping’ – thus further grounding REBT in the humanistic as well as the cognitive behavioural paradigms.

Another highly humanistic element of REBT lies in the focus on IBs as opposed to the focus on appraisals of reality. ‘REBT therapists hypothesize that people are more likely to make a profound philosophical change if they first assume that their inferences are true and then challenge their irrational Beliefs, rather than if they first correct their inferential distortions and then challenge their underlying irrational beliefs’ (Ellis and Dryden, Reference Ellis and Dryden1997, p. 25). This theoretical stance in REBT minimizes the chance of accidentally invalidating clients’ experiences and emotions early on in therapy before a strong working alliance is established (Al-Roubaiy, Reference Al-Roubaiy2012). Therefore, unlike CT, REBT is less concerned with As in the form of negative thoughts and environmental/social cues which can be considered cognitive distortions in CT. However, as some therapists might struggle to differentiate between thoughts that should be considered as As and not IBs, DiGiuseppe et al. (Reference DiGiuseppe, Doyle, Dryden and Backx2014) introduced an expanded ABC model to help therapists make this distinction.

In addition to the humanistic and emotionally validating dimensions, REBT includes many concepts that CT lacks and third wave therapies have borrowed and popularized as their own with little acknowledgement of the source (Velten, Reference Velten2007). For example, Linehan (Reference Linehan1993) described the intolerance of emotional upset by clients with borderline personality disorder as I can’t stand-it-itis (a term commonly used by REBT practitioners). Similarly, the notion of acceptance in therapies such as ACT has been around since the 1950s in REBT’s three acceptances (Ellis, Reference Ellis2005, pp. 157–158): unconditional self-acceptance (USA), unconditional other acceptance (UOA), and unconditional life acceptance (ULA). Other theorists have validated key REBT concepts in their work such as Barlow (Reference Barlow1991a,b), who explored how people can exaggerate their emotional disturbance by becoming anxious about their anxiety or depressed about their depression – which is precisely what Ellis’s (Reference Ellis and Bernard1989) concept of secondary emotional disturbance describes. Based on these observations alone, REBT can be considered as more comprehensive than other forms of CBT as it includes a variety of concepts and ideas that are found in bits and pieces in all these other forms of therapy.

As for the evidence base behind REBT, several large-scale meta-analyses have demonstrated that REBT works for a large spectrum of disorders (e.g. Engels et al., Reference Engels, Garnefski and Diekstra1993; Lyons and Woods, Reference Lyons and Woods1991). Similarly, David et al. (Reference David, Lynn and Ellis2010) review the research indicating that irrational beliefs are associated with a wide range of problems in life (e.g. drinking behaviours, suicidal contemplation, life hassles), and that exposure to rational self-statements can decrease anxiety and physiological arousal over time. Some studies have also demonstrated that when faced with negative life events, irrational beliefs can be predictive of psychopathological responses such as depression (Szentagotai et al., Reference Szentagotai, David, Lupu and Cosman2008), while rational beliefs can act as protective buffers against psychopathological responses such as post-traumatic symptoms (Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Maguire, Shevlin and Boduszek2014). However, despite being effective and efficacious as David et al. (Reference David, Szentagotai, Eva and Macavei2005) concluded in a synopsis on the research behind REBT, there was no empirical evidence for the notion that REBT is more efficient than other forms of CBT – which is why I describe REBT as being more theoretically comprehensive than other forms of CBT, not necessarily more efficient.

Limitations in REBT

The first limitation in REBT lies in the fact that it does not attend to activating events’ accuracy as CT does. In CT, negative automatic thoughts (NATs) are similar to activating events (As) in REBT, but unlike REBT’s philosophical conceptualization of As as neutral, CT differentiates between positive and negative thoughts (focusing primarily on the negative in therapy). Therefore, despite REBT’s comprehensiveness and attempts to incorporate inferences (DiGiuseppe et al., Reference DiGiuseppe, Doyle, Dryden and Backx2014), the reality is that REBT does not address the accuracy of perceptions/inferences (i.e. less concerned with perceptions being rooted in reality) as it focuses on the beliefs behind these perceptions/inferences. Even when this element is present in REBT, it does not match the extensive and detailed focus of CT when tackling NATs and all the cognitive distortions that they can reflect (e.g. dichotomous thinking, disqualifying the positive, biased scanning, emotional reasoning, etc.). This focus on NATs is so extensive in CT that ‘almost all the evidence currently available for the effectiveness of CBT is based on working primarily at the level of specific automatic thoughts and their associated behaviours’ (Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007, p. 62). The second limitation in REBT lies in the lack of acknowledgement of the complexity of the emotional dimension. Emotions in REBT are simply seen as Cs that can be healthy or unhealthy depending on the person’s underlying beliefs, but this notion fails to consider the mismatch between cognition and emotion that many people can struggle with (e.g. ‘I understand that I am anxious because of certain irrational beliefs but I still cannot help feeling this way’). This mismatch between cognition and emotion phenomenon, along with a lack of an emotion-regulation dimension in therapy highlights a major limitation in both REBT and CT. However, this limitation is thoroughly addressed in compassion-focused therapy (CFT; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009, Reference Gilbert2010).

The complementary nature of CFT

Paul Gilbert, the founder of CFT, defines compassion as ‘the sensitivity to suffering in self and others, with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it’ (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2014, p. 19). Interestingly, CFT’s theoretical stance of viewing unhealthy emotions such as anxiety as not the client’s fault but still his/her responsibility (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009, Reference Gilbert2010) is very much in line with REBT’s (Ellis, Reference Ellis2003) notion of our natural innate tendency for crooked thinking. CFT acknowledges the fact that adopting rational/healthy cognitions does not automatically transfer into experiencing healthy emotions or avoiding unhealthy emotions. This is especially true for clients with high degrees of shame, guilt and self-criticism. Such clients might have grown up seeking care and getting punished for it and this can make such people anxious as adults when they try to accept themselves and engage in less harsh critical self-talk (Gilbert and Irons, Reference Gilbert, Irons and Gilbert2005; Gilbert and Procter, Reference Gilbert and Procter2006). One major aim in CFT is to provide psychoeducation on three basic emotion-regulation systems: (1) the threat/self-protect system, (2) the drive–reward system, and (3) the affiliative/soothing system. Case formulation in CFT is threat-focused in that it links historical difficulties with current fears and safety strategies, and tends to revolve around the functioning and ‘balance’ of a client’s ‘three systems’.

CFT highlights how many people can become trapped between the threat and reward systems and as a result fall into experiencing high levels of self-criticism and shame (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2014). CFT uses imagery and exercises (e.g. compassionate letter writing, compassionate chair work, etc.) to facilitate ‘compassion as flow’, in which compassion is evoked in three directions: (1) from others to self; (2) from self to others; and (3) from self to self (i.e. self-compassion). CFT uses exercises to access the soothing system through mindfulness, rhythm soothing breathing, and various forms of imagery. CFT is unique in its approach to formulation and intervention, and it has no specific time limitations or restrictions, which has allowed many to incorporate it into their own integrative models with promising results. Tirch et al. (Reference Tirch, Schoendorff and Silberstein2014), for example, integrated CFT with ACT in a new approach they call compassion-focused ACT (CFACT). Similarly, CFT has been integrated into treatment protocols for anxiety disorders (Tirch, Reference Tirch2012), anger (Kolts, Reference Kolts2012), eating disorders (Goss, Reference Goss2014) and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (McFetridge et al., Reference McFetridge2017). CFT’s complementary nature, as well as its unique approach to addressing unhealthy emotions (mainly shame and guilt), makes it an ideal addition to any integrative model that is too cognitive in nature.

CFT has a growing evidence base which points to both its effectiveness with a wide range of mental health problems, as well as its complementary nature as it becomes especially effective when combined with CBT. In a recent systematic review that included 14 evaluation studies, Leaviss and Uttley (Reference Leaviss and Uttley2015) concluded that CFT shows promise as an intervention for mood disorders, particularly for people with high self-criticism. Similarly, Beaumont and Hollins Martin (Reference Beaumont and Hollins Martin2015) conducted a narrative review of 12 studies utilizing CFT for a range of different mental health problems and found CFT to be an effective therapeutic intervention, especially when combined with CBT. Taking into account how: (1) CT is much more thorough than REBT in helping clients identify and change their distorted inferences about reality through the focus on NATs that are not rooted in reality (in REBT terms, As that reflect false inferences), (2) how CFT can fill a void in both CT and REBT when it comes to working with highly self-critical clients with severe shame and guilt, and (3) how REBT is the most theoretically comprehensive form of CBT – it made perfect sense to integrate CT and CFT into a model that places REBT at the heart of assessment and intervention while making use of the complementary dimensions of these other two therapeutic approaches.

Before introducing my integrative model and demonstrating it with a case example, I will briefly explore the value and relevance of psychotherapy integration in general to highlight the need for further attempts at creating integrative CBT models as I genuinely believe that the future of CBT is in psychotherapy integration.

Value and relevance of psychotherapy integration

Many would argue that the future of psychotherapy research and practice revolves around the utilization of the common factors theory (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Miller, Wampold and Hubble2010; Wampold, Reference Wampold2001). Paul Wachtel was among the first integrative psychotherapists integrating in his model psychoanalysis with behaviorism (Wachtel, Reference Wachtel1997). The common factors theory proposes that it is the common components of the different approaches that mostly account for outcome in psychotherapy, and that the components which are considered unique to each approach have but a minor role in the induced therapeutic change (Imel and Wampold, Reference Imel, Wampold, Brown and Lent2008; Wampold et al., Reference Wampold, Mondin, Moody, Stich, Benson and Ahn1997). Since it was first suggested by Rosenzweig in Reference Rosenzweig1936, the concept of the common factors has continued to gain support (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Miller, Wampold and Hubble2010; Hubble et al., Reference Hubble, Duncan and Miller1999; Wampold, Reference Wampold2001). As Cooper and McLeod (Reference Cooper and McLeod2007, p. 135) observe, ‘no single therapeutic approach has a superior grasp of the truth’.

Pompoli et al. (Reference Pompoli, Furukawa, Imai, Tajika, Efthimiou and Salanti2016), for example, performed a network meta-analysis in which they compared eight different forms of therapy and three forms of control conditions to assess the comparative efficacy of different therapies. They included RCTs focusing on adults with a formal diagnosis of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. The review included supportive psychotherapy, behaviour therapy, CT/CBT, third wave CBT, and psychodynamic therapies. Among other things, Pompoli et al. (Reference Pompoli, Furukawa, Imai, Tajika, Efthimiou and Salanti2016) found that: (1) there is no high-quality evidence to support one psychological therapy over the others for the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in adults; (2) although there was evidence for the superiority of CT/CBT, the effect size was often small and the level of precision was often insufficient or clinically irrelevant; (3) psychodynamic therapy showed promising results in terms of both efficacy and low drop-out rates; and (4) the researchers were surprised to find evidence in support of the possible viability of non-specific supportive psychotherapy for the treatment of panic disorder. The results clearly support the common factors theory as no single form of therapy was shown to be above all the rest sufficiently/clearly enough, and as each different form of therapy showed some positive results and promise in varying degrees – including non-specific supportive psychotherapy.

One way of utilizing common factors in therapy has been through the creation of integrative approaches such as those described by Norcross (Reference Norcross, Norcross and Goldfried2005). Norcross (Reference Norcross, Norcross and Goldfried2005, pp. 8–10) describes the following routes to integration: common factors; technical eclecticism; theoretical integration; and assimilative integration. The first route to integration, common factors, ‘seeks to determine the core ingredients that different therapies share in common’; the second route, technical eclecticism, is designed ‘to improve our ability to select the best treatment for the person and the problem’; the third route, theoretical integration, occurs when ‘two or more therapies are integrated in the hope that the result will be better than the constituent therapies alone’; and the fourth route to integration, assimilative integration simply recognizes that most psychotherapists use a single approach as their foundation but end up incorporating different ideas from other approaches as time goes by – a fact documented by several authors in the psychotherapy literature (Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Newman, Borkovec, Holtforth, Maramba, Norcross and Goldfried2005; Jones-Smith, Reference Jones-Smith2016; Stricker and Gold Reference Stricker, Gold, Norcross and Goldfried2005).

Most experienced psychotherapists do not prefer to identify themselves completely with a single approach, but prefer to identify themselves as integrative or eclectic (Feixas and Botella, Reference Feixas and Botella2004). In a recent large survey of over 1000 psychotherapists, only 15% stated using only one theoretical orientation in their practice, and the median number of theoretical orientations used in practice was four (Tasca et al., Reference Tasca, Sylvestre, Balfour, Chyurlia, Evans and Fortin-Langelier2015). Integrative psychotherapy is therefore valuable and relevant; valuable because it acknowledges the common factors theory and relevant because it is reflective of how most experienced therapists practise in real-life clinical settings. Even the founder of ACT, who initiated the third wave CBT movement by rejecting what he described as ‘the mechanistic content-oriented forms of many behavioural and cognitive–behavioural treatments’ (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999, p. 21) has become more in favour of integration/assimilation. As Hayes and Hofmann (Reference Hayes and Hofmann2017, p. 245) note: ‘The metaphor of a “wave” suggested to some that previous generations of work would be washed away, but that was not the intent and that was not the result. Waves hitting a shore assimilate and include previous waves – but they leave behind a changed shore’.

Having explored the over-arching relevance and value of integrative psychotherapy in this section – in addition to the earlier explorations of the limitations of CT, MBIs, third wave CBT and even REBT – I can assert my belief in psychotherapy integration being the future of CBT. In the next section, I will introduce and demonstrate my integrative model.

Assimilative integrative rational emotive behaviour therapy

The model is designed to place REBT at the heart of all theorizing and interventions. CT and CFT are incorporated as additions to complement the core which is primarily REBT-oriented. Based on Norcross’ (Reference Norcross, Norcross and Goldfried2005) classifications of psychotherapy integration, I call this model assimilative integrative rational emotive behaviour therapy (AI-REBT). Simply put, therapy starts with an REBT focus for three to six sessions. The client is educated in the ABC model and introduced to the necessary steps of DE as we explore his/her irrational beliefs and attempt to change them to the healthier/rational/effective alternatives. After this initial phase of three sessions, I begin to introduce the client to CT with its clear focus on identifying and challenging the validity behind NATs, which were deliberately neglected in the previous phase as I was attempting to build rapport by not challenging the client’s perceptions/experiences of reality. Another reason for deliberately neglecting to explore the validity behind some of the client’s NATs in the first phase is to cement the idea that many of these NATs can actually be conceptualized as As in REBT, having no power or influence over the individual unless they trigger certain IBs.

The second phase entails using three to six CT sessions with its defining features (e.g. disputing cognitive distortions; reducing/eliminating avoidance and safety behaviours; engaging in exposure to anxiety-provoking situations, etc.) but it also includes reminders from lessons learned in the first phase in the form of IBs that were identified and disputed using REBT. Essentially, the client learns in the first phase to use REBT’s semantic precision to catch himself/herself in the act of reinforcing IBs which he/she will be reframing semantically in his/her self-talk to cement the neutrality of As, dispute IBs, and exchange them for the rational alternatives in order to experience healthier Cs. In the second phase CT, takes up much of the therapy but REBT is kept alive and done simultaneously, until the client is no longer engaging in avoidance or safety behaviours, and no longer accepting NATs as reflective of reality.

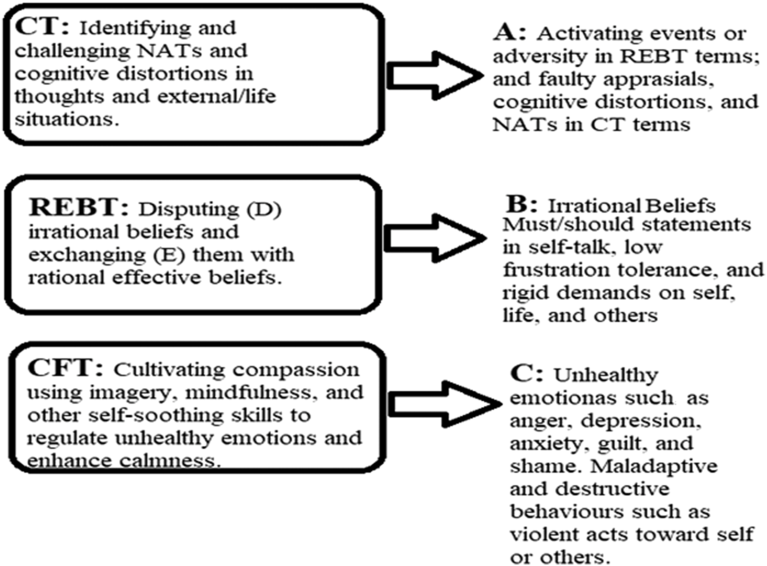

The third phase marks the introduction of CFT with a specific focus on raising the client’s compassion, self-soothing and emotion-regulation capabilities. In typical CFT fashion, we focus on using: psychoeducation (how harsh/critical self-talk, guilt and shame can activate the stress systems and trigger unpleasant emotions such as anxiety and depression, which can override a person’s wish to think rationally due to the ‘better safe than sorry’ threat assessment mechanism); compassionate mind training (cultivating and generating feelings of warmth and kindness towards oneself and others through activities such as compassionate letter writing, compassionate behaviours, and the use of imagery involving the compassionate self); and exercises to rest the mind and body (e.g. mindfulness, soothing rhythm breathing, and simple body scan/relaxation) (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009, Reference Gilbert2010). Depending on the type and severity of a client’s problems, and his/her capacity to utilize CFT concepts, this third phase can take up to six sessions or less. The model is illustrated in Fig. 1, with each therapeutic component targeting one dimension in the ABC model, but understandably there is considerable overlap in which dimensions are targeted by which interventions at any given stage in therapy. The therapy typically starts with three REBT sessions, followed by three to six CT sessions, and finally three to six CFT sessions – while keeping every concept previously learned/applied alive throughout therapy. To further illustrate how the model can be used, a recent case example from my own clinical practice is also presented below.

Figure 1. IA-REBT with its therapeutic components (CT, REBT and CFT) targeting specific ABC dimensions in three phases that can overlap in use of interventions at any given stage.

Case example

Saeed is a 26-year-old Emirati man with social phobia (consent has been granted and the patient’s name and other personal information has been altered to protect his identity). He has been struggling with intense anxiety in social settings since he was 12 years old. The past few years have been particularly distressing for him as his social responsibilities have increased along with the demands placed on him by his family in terms of being a spokesman for the family and representing them in ceremonies and formal occasions. Early on in the first three sessions, we were able to identify Saeed’s main IBs that were responsible for his intense anxiety in social settings; mainly ‘I must be perfect in presenting myself in social gatherings’, ‘it would be awful if I made a mistake by saying something stupid’, and ‘social ceremonies must go well for me’. Saeed was able to see by the end of session 3 that he needed to reframe his beliefs to reflect a preference for doing well socially as opposed to demanding it of himself in the use of the word ‘must’. Similarly, Saeed realized that insisting that social ceremonies always go well reflects IBs and he gradually began to express this need as a preference in addition to trying to adopt the rational beliefs of acceptance of himself in case he does make a mistake (USA) and acceptance of life if the ceremony does go badly (ULA). Saeed was also raising his frustration tolerance by the end of session 3 and accepting that he can tolerate saying something stupid in ceremonies, and that it would be unpleasant but pretty much tolerable as opposed to his earlier awfulizing of such an event. The one aspect that we could not address thoroughly in REBT was his perfectionism and insistence on excelling socially.

In session 4, Saeed was introduced to CT and we began mapping out his NATs (mainly in the form of his self-image as being socially awkward and incompetent), his use of avoidance (mainly declining social invitations), and his use of safety behaviours (mainly minimizing eye contact and keeping conversations short). We began to challenge the validity behind these NATs and experimenting with dropping avoidance and safety behaviours while exploring new ways of interacting with people that do not involve safety behaviours. Saeed was very reluctant to give up some of his safety behaviours as he was convinced that they were helping him. However, he gradually began to realize that minimizing eye contact and keeping conversations short was making him look indifferent to others who usually began to avoid him after a brief interaction not because he is stupid, incompetent, or has nothing to say (basically his interpretation of why conversations do not last) but because of the social signals he was conveying through the use of safety behaviours (a classic example of self-fulfilling prophesies in CT terms).

Saeed could also see by the end of session 9 that many of his previous interpretations of social cues were false, but he was grateful for not being confronted with this early on in therapy as he felt that it would have further reinforced his feelings of inadequacy. Saeed had mastered in these nine sessions key elements from REBT and CT and was: no longer careless with the use of language that can reflect IBs; constantly monitoring his self-talk to identify and challenge any residual IBs; striving towards a more accepting and flexible attitude towards his preferences in social settings; and no longer engaging in safety behaviours or avoidance as he was constantly engaging in graded exposure to socially anxiety-provoking situations. However, Saeed was feeling guilty about being more accepting of possible failures in social settings, and he was feeling ashamed of giving up on the idea of excelling in social ceremonies.

In further exploring what it meant for Saeed to excel in social settings in session 10, it became apparent that he was brought up in an atmosphere of criticism, emotional neglect, and an insistence on perfection at all times (i.e. always presenting a perfect social image to avoid dishonouring the family name). Saeed was even describing to me that he believed his insistence on excelling socially and his fear of being viewed as incompetent were exaggerated and irrational, but he could not help feeling this way. This mismatch between cognitions and emotions, coupled with the elements of self-criticism, shame and guilt was the cue to introduce Saeed to CFT.

From sessions 10 to 15, we focused on cultivating self-compassion by first helping Saaed to understand that it is not his fault (but his responsibility to remedy) how he gets anxious in these situations considering his upbringing and critical/harsh self-talk (which tends to activate the threat systems that override all other systems despite his best efforts). Saeed was also encouraged to cultivate compassion towards himself through activities such as: compassionate letter writing; compassionate behaviours; being mindful of the tone of his self-talk (switching from harsh/aggressive to kind/gentle); and the use of imagery (mimicking compassionate facial expressions and imagining a compassionate self that is capable of soothing him when in need). Saeed was also encouraged to use exercises to rest his mind and body (e.g. mindfulness, soothing rhythm breathing, and simple body scan/relaxation), which he found to be very helpful in reducing his anxiety in social settings and even in helping him relax throughout the day. At the end of session 15 we established that Saeed was now: much less likely to get anxious in social ceremonies; more relaxed and at ease with the possibility of behaving inadequately in these settings; no longer using avoidance or safety behaviours in social settings; and constantly engaging in compassionate self-correction as opposed to harsh self-criticism in his self-talk thereby eliminating the guilt and shame.

Closing comments

Practitioners interested in incorporating this model into their practice can partially rely on the evidence base behind each of the components (REBT, CT and CFT) that make up this integrative model to assert that they are using an empirically validated approach. However, it is worth noting that psychotherapy integration has always presented a challenge for researchers because of the many variables inherent in the process (client factors, therapist factors, therapeutic common/specific factors, etc.), making it impossible to manualize and test integrative approaches to the standards required for formal therapy validation. For proponents of REBT, this model should have a special appeal as it represents an attempt at preserving the legacy of Ellis and other prominent REBT theorists by situating the approach at the forefront of CBT evolution and progress.

Acknowledgements

No advice or support was given in creating this work.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

I, Najwan Saaed Al-Roubaiy, have no conflict of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statement

I, Najwan Saaed Al-Roubaiy, have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA and the BPS Code of Human Research Ethics. No ethical approval was needed because this publication is a practice paper using theory and a case example to introduce, and illustrate the use of, an integrative psychotherapy model.

Key practice points

(1) Using the ABC model of REBT to conceptualize the client’s problems while using CT and CFT in addition to REBT to intervene at each level of conceptualization as opposed to only intervening at B (i.e. beliefs), as is typical in REBT.

(2) Using CT to help clients question the validity of their thoughts and their perceptions of external situations at the level of A in the ABC model (i.e. activating events and adversity in the form of social situations and thoughts).

(3) Using CFT to help clients self-soothe and enhance their calmness when they are experiencing distressing emotional consequences (such as guilt and shame) at the level of C in the ABC model (i.e. emotional and behavioural consequences that arise as a result of harsh/critical self-talk that evokes the threat system).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.