INTRODUCTION

On June 16, 2015, Donald Trump descended from his gilded escalator at Trump Tower in New York City and announced his candidacy for president. Cementing his status as a political outsider from the onset of his campaign, Trump, ignoring norms of political correctness and racial political rhetoric, decried immigrants from Mexico:

When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us [sic.]. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people (The Washington Post 2015).

Although Trump was chastised for his rhetoric, he persisted, famously Tweeting an image of himself eating a taco bowl with the caption “Happy #CincoDeMayo! The best taco bowls are made in Trump Tower Grill. I love Hispanics!”, and reportedly encouraging supporters Rudy Giuliani and Jeff Sessions to wear “Make Mexico Great Again Also” hats at a rally in Phoenix, Arizona (Feldman 2016; Trump Reference Trump2016a). The Republican National Committee (RNC) even misprinted signs and buttons that read “Hispanics Para Trump” (Hispanics stop Trump) instead of “Hispanos por Trump” (Hispanics for Trump) (Rupert Reference Rupert2016). Perhaps most infamously, Trump accused a federal judge assigned to preside over a fraud case against Trump University of being biased due to his Mexican ancestry (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2017). Despite expert predictions, Trump went on to win the Republican nomination and the presidency in one of the most surprising elections in American history (FiveThirtyEight 2016). Maybe more surprising though, was that Trump won the presidency with as much as 29% of the Latino vote (Gomez Reference Gomez2016).Footnote 1

Estimates of Trump’s share of the Latino vote range between 18% and 29%, depending on which exit poll one looks at (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Schaller, Segura, Sabato, Kondik and Skulley2017; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Jacoby, Strickland and Rebecca Lai2016; Latino Decisions 2016). And while there was much talk of how a Latino voting surge would block Trump’s path to the White House, many estimates suggest that Trump won as much or more of the Latino vote than the 2012 Republican candidate Mitt Romney (Enten Reference Enten2016; Shepard Reference Shepard2016). This result is perplexing for many observers of Latino politics, as Romney had seemingly reached a low point for Republicans as far as the Latino vote was concerned. Where George W. Bush had drawn as much as 40% of the Latino vote with his progressive immigration policies and respect for the Latino community, Romney drew an estimated 23% with his message of self-deportation (ImpreMedia and Latino Decisions, 2012; Madison Reference Madison2012; Suro et al., Reference Suro, Fry and Passel2005). Romney fared so poorly that the Republican Party ordered an autopsy of sorts in its Growth and Opportunity Project , which critiqued where the party had gone wrong and offered strategies for remaining competitive in the future. Chief among the report’s prescriptions was that it was imperative that the Republican Party change how it engages with Hispanic communities. According to the report, if Republicans wanted to contest the Hispanic vote, they needed to demonstrate that they care about Hispanics, recruit more minority candidates, and champion comprehensive immigration reform.

Clearly, Donald Trump did not adhere to the Growth and Opportunity Project’s suggestions as far as Latinos are concerned. But with all this in mind, how did Trump match or even surpass Romney’s share of the Latino vote despite increasing the racially charged rhetoric specifically targeted at Latinos in general and Mexicans in particular? This paper is the first data-based investigation of Latinos who voted for Donald Trump. It examines which voter characteristics predict Latino support for Trump, whether these characteristics differ from those that predicted support for Romney in 2012, and if Latino predictors of support for Trump differ from those of non-Hispanic Whites. Using data from the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), this paper argues that for Latinos, denial of racism was the strongest predictor of support for Trump above even party identification and political ideology. Additionally, Trump may have only increased the relative strength of denial of racism as a predictor of Latino support for race-baiting candidates, as denial of racism was also the strongest predictor of Latino support for Mitt Romney. Comparisons to non-Hispanic White voters suggest that Latinos are behaving like their White counterparts, for whom denial of racism has also recently trumped party identification and ideology as a predictor of support for race-baiting candidates.

But how could Latinos who deny racism support a candidate like Trump? I argue that the similarities between Whites and Latinos who voted for Trump are no coincidence, as the 2016 presidential election, like California’s Proposition 187 in 1994, which would have prohibited undocumented immigrants from using public services in California, served as a litmus test for Latinos to signal their allegiance to Whites (Basler Reference Basler2008). By denying that racism exists at all in the United States, while at the same time supporting a race-baiting candidate, Latinos could mimic White behavior in an effort to the reduce the social space that exists between themselves and Whites and gain protection from potential discrimination (Basler Reference Basler2008; Gans Reference Gans2012; Murguia and Forman, Reference Murguia, Forman, Doane and Bonilla-Silva2003; Warren and Twine, 1997). For Latinos then, denial of racism serves a measure of a Latino’s desire to achieve Whiteness. When taking these findings into account, this suggests that while Trump’s rhetoric may have reduced his support among Latinos at large, his explicit racial appeals may have played a large role in motivating support for Trump among the subset of Latinos holding disproportionately higher levels of denial of racism.

REVIEWING LATINO VOTE CHOICE

Suggesting that some voter characteristics may motivate Latino vote choice more than party identification fits with the recent literature in Latino politics. Although Latinos have consistently voted for the Democratic candidate in presidential elections, they may be motivated to do so beyond simple partisan attachment (DeSipio Reference DeSipio1998; Rodolfo and Cortina, 2007). Zoltan L. Hajnal and Taeku Lee (Reference Hajnal and Lee2011) found that party identification is declining among Latino and Asian Americans as they are not being incorporated into the American party system. Rather, these voters are identifying as independents. Other research finds that U.S.-born and naturalized Latinos showed only slightly higher levels of non-partisanship than non-Hispanic Whites, and that non-citizen Latinos are about twice as likely as their naturalized or U.S.-born counterparts to identify as non-partisans (Sears et al. Reference Sears, Danbold and Zavala2016). It could then be the case that newer Latino immigrants take time to acclimate to the American political environment before affiliating with a political party. To this point, the literature suggests that among Latinos who have been in the United States for less than twenty years, most identified as non-partisans (Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003).

Turning to other long held predictors of vote choice, political ideology has been shown to be a strong predictor of Latino vote choice in elections where moral issues have been a focal point (Abrajano et al., Reference Abrajano, Michael Alvarez and Nagler2008; Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003), but Hajnal and Lee (Reference Hajnal and Lee2011) argue that the conventional conservative, moderate, and liberal labels may not apply to Latinos. Research on religion and Latino vote choice suggests that denomination and religious attendance are closely tied to ideology and partisanship, as Latino Protestants are more likely to identify as conservatives and hold more conservative views on social issues than Latinos of other religious denominations (Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2014; Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Echevarría and Smith2005). Other scholars find that, relative to Catholics and Latinos of other religious denominations, Latino Protestants and evangelicals are much more likely to identify as Republicans and support Republican candidates (Jones-Correa and Leal, Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001; Kelly and Kelly, Reference Kelly and Kelly2005; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2014).

According to Alvarez and García Bedolla (Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003), Latinos with lower levels of education are more likely to identify as Democrats, although others suggest that education is not associated with party identification and vote choice among Latinos (Uhlaner and Garcia, Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Bowler2005). While income does not appear to be associated with party identification for Latinos (Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003; Uhlaner and Garcia, Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Bowler2005), length of time in the United States is found to shape vote choice, as first- and second-generation Latinos are much less likely to support Republican candidates than third-generation Latinos (DeSipio and Uhlaner, 2007; Nuño Reference Nuño2007). Another consistent finding is that national origin is strongly associated with party identification and vote choice (Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003; Uhlaner and Garcia, Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Bowler2005). Cubans are much more likely to identify as Republicans and support Republican candidates, while Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Central Americans are more likely to be Democrats. To this point, when predicting Republican versus Democratic partisanship among Latinos, research suggests the strongest predictor of identifying as a Republican is being Cuban (Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003).

For those Latinos with low party attachment, it stands to reason that they may look to candidates for cues (Wattenberg Reference Wattenberg1991). The research finds that co-ethnic cues are a strong predictor of Latino vote choice, with low information voters, or those voters who have little to no understanding of politics, being especially receptive to these cues (Barreto 2007, Reference Barreto2010; Nicholson et al. Reference Nicholson, Pantoja and Segura2006). For Latino voters, the presence of a co-ethnic on the ballot functions as a shortcut that helps them judge how well the candidate will represent the interests of their ethnic group (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Pantoja and Segura2006). There are limits to shared ethnicity, however; more educated Latinos are less likely to favor co-ethnic candidates solely because of their ethnicity (Manzano and Sanchez, Reference Manzano and Sanchez2010). Despite their shared ethnicity, Latino Republican candidates in California have not been able to win significant shares of the Latino vote, likely because they are not able to overcome the Republican Party’s past support of the anti-Latino Proposition 187(Michelson Reference Michelson2005). Latino candidates still make up a relatively small share of all candidates in the United States, so enterprising candidates from both parties have had to rely on cross-racial appeals to attract Latino voters.

Cross-racial appeals to Latinos often take the form of Spanish-language radio or television advertisements, which date as far back as Dwight Eisenhower’s campaign (Abrajano Reference Abrajano2010; Collingwood et al., Reference Collingwood, Barreto and Garcia-Rios2014). Jessica Lavariega Monforti and colleagues (Reference Lavariega Monforti, Michelson and Franco2013) found that Latino voters, including Republicans, in Texas generally favor Spanish speaking candidates at the polls. The literature suggests these cross-racial appeals may be effective among Latino voters as they demonstrate the candidate’s respect for the Latino community (Barreto and Collingwood, 2014). Candidates can also demonstrate respect and concern for the Latino community via policy-based outreach, as Obama was able do on immigration and the DREAM (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act in 2012 (Barreto and Collingwood, 2014; Collingwood et al., Reference Collingwood, Barreto and Garcia-Rios2014). The literature on Latino vote choice suggests that racial and ethnic variables may at times trump traditional predictors of vote choice, but little has been written in political science on how denial of racism, and racism in general, among Latinos affects vote choice. In other words, do appeals traditionally designed for racially resentful Whites (e.g., Trump’s rhetoric) also work with a subset of Latino voters who might hold similar beliefs?

EXPLORING LATINO RACISM AND DENIAL OF RACISM

Much of the work on racism and Latinos has explored the effects of White racism on Latinos. This is understandable given that for many Latinos, their experience in the United States has been shaped by racism in one form or another (Brewster et al., Reference Brewster, Foster and Stephenson2016; Florido Reference Florido2017). However, leaving out measures of racism among Latinos when predicting vote choice, particularly Republican vote choice, may limit our understanding of why some Latinos vote Republican, especially when recent work suggests racism was a strong predictor of support for Trump among Whites (Miller Reference Miller2017; Schaffner et al., Reference Schaffner, MacWilliams and Nteta2018).

The literature on Latino racism has largely focused on racial resentment, which has been defined as a conjunction of anti-Black feelings and American moral traditionalism (Carmines Reference Carmines, Sniderman and Easter2011; Kinder and Sears, Reference Kinder and Sears1981). One major theme of this literature is that it questions the emerging Democratic majority posited by John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira (2004). Judis and Teixeira (Reference Judis and Teixeira2004) argued that given current demographic and political trends, the U.S. political arena would eventually be ruled by a multicultural, multiethnic Democratic coalition. However, this emerging Democratic majority depends in part on Latinos not becoming White as Italian and Irish Americans did (Murguia and Forman, Reference Murguia, Forman, Doane and Bonilla-Silva2003). The work of Edward Murguia and Tyrone Forman (2003) recognizes the fact that Italian and Irish Americans may have had an easier path to Whiteness than Latinos given their lighter complexions and European backgrounds, but they did not rule out the possibility that some Latinos may want to become White to escape persecution and racism. Just as Italian and Irish Americans did, the fastest path to Whiteness for Latinos may be to minimize the social space between themselves and Whites and adopt White views of race and racism (Gans Reference Gans2012; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; Murguia and Forman, Reference Murguia, Forman, Doane and Bonilla-Silva2003; Warren and Twine, Reference Warren and Twine1997).

Of course, not every Latino will want to pursue Whiteness given the racism and treatment as second-class citizens many Latinos have experienced (López Reference López1997; Garcia and Sanchez, 2008). At the same time though, given the racial diversity that exists among Latinos, every Latino will not be subjected to the same set of racialized experiences (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003; Sanchez and Masuoka, Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010). Even when Latinos are subjected to racism, research suggests many will deny or explain the racism away (Florido Reference Florido2017; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2008; Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016). In her study of denial of racism among Latino college students, Deyanira Rojas-Sosa (Reference Rojas-Sosa2016) found that Latino students are often hesitant to recognize that they were the subject of discrimination or to qualify experiences as racist. Rojas-Sosa (Reference Rojas-Sosa2016) argued that Latinos, and other minority groups, may deny the existence of racism to not challenge the ideologies of majority groups (e.g., Whites) on issues of race and immigration. Beyond denying racism in their own lives, some Latinos will even deny racism on the part of their countrymen, especially when they are trying to defend their image of the United States as a place that is free of racism (Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016). To this point, Rojas-Sosa (Reference Rojas-Sosa2016) demonstrated that a common strategy used to explain away racism is that society has overcome racism as a social problem. This logic is similar to that of the colorblind ideology, which argues that race no longer has a key impact on the lives of Americans as the United States has transcended racism and become a post-racial society (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017).

Other research also suggests many Latinos and Asians try to deny racism in their lives and treat racism as something of the past (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2008). However, when minorities espouse colorblind ideologies and deny racism, this does not necessarily mean that they are embracing these positions; rather, they may be acting instrumentally as complaining about racism could call attention to their otherness (Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2008). For those Latinos who want to minimize the social space that exists between themselves and non-Hispanic Whites, Herbert J. Gans (Reference Gans2012) argues they can modify their behavior and lifestyle to resemble Whites socially and culturally. This could be adopting White views on racism and society, such as the colorblind ideology, or voting for White candidates who espouse these views, such as Donald Trump (Gans Reference Gans2012).

Research also suggests that for some Latinos, voting for Republican candidates and restrictionist policies is a conscious effort to emulate White behavior in order to achieve inclusion, validation, and protection (Basler Reference Basler2008). Based on interviews with Mexican Americans, Carleen Basler (Reference Basler2008) identifies California’s anti-immigrant and anti-Mexican Proposition 187 as a turning point, which gave naturalized Mexican Americans a chance to align themselves with non-Hispanic Whites against their fellow Mexicans and Latinos in order to obtain Whiteness and the social benefits that come with it. Many Mexican Americans in Basler’s (Reference Basler2008) interviews were afraid or tired of being profiled as undocumented immigrants by Whites, so they voted in favor of restrictionist policies to improve their own standing and signal their allegiance to Whites. Echoing Gans’ (Reference Gans2012) findings, some Mexican Americans told Basler (Reference Basler2008) that by voting Republican, they could distance themselves from Blacks, the reference category against which Whiteness is determined, and further ingratiate themselves to Whites.

THEORY

Trump is just the most recent in a long line of candidates to use dog-whistle politics to provoke racial animus (López Reference López2016). Dog whistles are appeals that may seem innocuous to most individuals while communicating a coded appeal to a specific subgroup. In the case of racial appeals, dog whistles can shield a candidate and their supporters from criticism, as we see when Trump reassures his supporters that he and they are not racist. When Trump was attacked by Romney for his comments about a Mexican American judge, Trump tweeted “Mitt Romney had his chance to beat a failed president but he choked like a dog. Now he calls me racist—but I am the least racist person there is” (Trump Reference Trump2016b). After reported comments about Haiti and African countries, Trump said, “No, no, I’m not a racist. I am the least racist person you have ever interviewed. That I can tell you” (Covucci Reference Covucci2018).

Trump’s rhetoric allows his White supporters to act on their racial biases while denying their own racism, and racism in America at large, in line with the colorblind ideology. For most Latinos, Trump’s rhetoric will signal a threat, which likely increases in-group solidarity and decreases support for Trump (LeVine and Campbell, Reference LeVine and Campbell1972). For Latinos who seek to become White though, Trump’s anti-Latino and anti-immigrant rhetoric signals a litmus test of one’s allegiance to Whites. I predict Latinos who deny racism, as a means to reduce the social space between themselves and Whites (Murguia and Forman, Reference Murguia, Forman, Doane and Bonilla-Silva2003; Warren and Twine, Reference Warren and Twine1997), will support Trump, just as Latinos who voted in support of California’s Proposition 187 did in 1994 (Basler Reference Basler2008). Thus, for Latinos, denial of racism serves as a measure of an individual’s desire to achieve Whiteness (Gans Reference Gans2012; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2008; Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016).

Could cognitive dissonance be at work when Latinos who purport to deny racism support race-baiting candidates like Trump? Based on the work of Gans (Reference Gans2012) and Basler (Reference Basler2008), I argue not, as denying racism while supporting race-baiting candidates is a strategy some Latinos will undertake to climb the racial hierarchy. Like Gans (Reference Gans2012), I argue that to fully embrace Whiteness, minorities will have to adopt commonly-held White viewpoints, such as the colorblind ideology, even in the face of racism, to signal their allegiance to Whites (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017). I contend that in the presence of a candidate like Trump, who made explicitly anti-immigrant and anti-Mexican appeals, Latinos are presented with a choice: they can acknowledge that racism is still a pressing concern in the United States and reject the candidate who engages in race-baiting, or they can deny that racism exists and support the candidate who seeks to defend the racial hierarchy from which they hope to benefit. Beyond voting for party or ideology, some Latinos in 2016 saw Trump as their chance to signal their allegiance to Whites, as Basler (Reference Basler2008) demonstrated was the case with California’s Proposition 187. As one Mexican American told Basler, “voting for 187 was a ‘way to make sure the whites [at his job] knew he was with them’ so they wouldn’t think he was ‘some Mexican traitor who felt sorry for the wetbacks’” (2008, p. 148).

What then, is driving Latinos who deny racism to support a candidate like Trump or policies like Proposition 187? According to research, Latinos may be consciously manipulating their identities to fulfill their social psychological need for protection in the face of a potential threat (Smith Reference Smith1992; Basler Reference Basler2008). Should Whites accept Latinos who deny racism as White, a Latino’s need for validation and inclusion could also be fulfilled (Smith Reference Smith1992; Basler Reference Basler2008). We should not expect most Latinos to deny racism in an attempt to embrace Whiteness, as realistic conflict theory argues that out-group threat and hostility often lead to higher levels of in-group identification (Levine and Campbell, Reference LeVine and Campbell1972). However, among members of stigmatized groups, it is possible that some may attempt to distance themselves from their in-group when facing a threat (Howard Reference Howard2000). This is in line with self-affirmation theory, which argues that individuals are motivated to maintain self-integrity (Sherman and Cohen, Reference Sherman, Cohen and Zanna2006). Indeed, Sherman and Cohen (Reference Sherman, Cohen and Zanna2006) argue some individuals will protect their self-integrity through the affirmation of alternative sources of identity, as the literature shows minorities who adopt Whiteness have done (Gans Reference Gans2012; Basler Reference Basler2008).

Thus, I argue that in the presence of a candidate like Trump, who focused his attacks on Latinos, denial of racism should be a stronger predictor of support for Trump among Latinos than Whites. We can expect this because due to his anti-Latino rhetoric, Trump should be starting at a lower point of support among Latinos relative to Whites, all else held equal. However, Latinos high in denial of racism, which I treat as a proxy for one’s desire for Whiteness, should see Trump as a chance to signal their allegiance to Whites and should be highly motivated to support Trump, as Basler (Reference Basler2008) argues some Latinos did when California’s Proposition 187 was on the ballot.

Following this logic, we should expect Latinos who deny racism to be most supportive of Donald Trump. Latinos who acknowledge racism should then be the least supportive of Donald Trump. While I use Latino support for Trump as my test case, I also argue that denial of racism should be a strong predictor of Latino support for Mitt Romney, although to a lesser degree than Trump given the tenor of Trump’s rhetoric relative to Romney’s. To this point, denial of racism should not be a statistically significant predictor of support for non-race baiting candidates, whether they be Democrats, Republicans, or independents. Finally, although I argue denial of racism should be a strong predictor of non-Hispanic White support for Trump, I argue that denial of racism will be a stronger predictor of Latino support for Trump. Based on my theory, I will test the following hypotheses in this paper:

H1: Denial of racism will be positively associated with support for Donald Trump among Latinos.

H2: Denial of racism will be positively associated with support for Mitt Romney among Latinos.

H3: Denial of racism will be a stronger predictor of support for Donald Trump among Latinos than non-Hispanic Whites.

DATA AND METHODS

To test whether denial of racism is a predictor of Latino support for Trump, I use the 2016 CCES, a nationally representative survey of American adults. The CCES includes 46,289 non-Hispanic White respondents and 7495 Latino respondents. The data were weighted using post-election sample weights, and weights were included in each analysis. The primary dependent variable is the two-party vote for president. This variable includes only those who reported voting in the presidential election and voted for either the Democratic or Republican candidate. Individuals who voted for a candidate other than Clinton or Trump in 2016, or Obama or Romney in 2012, are not included in the main analyses. For the sake of comparison on the key independent variable, the 2012 vote models use a measure of presidential vote choice taken during the 2016 CCES as no measure of denial of racism is available on the 2012 CCES.

The key independent variable measures denial of racism. Denial of racism is measured on a scale made up of three items used by Brian F. Schaffner and colleagues (2018) to measure acknowledgement and empathy with racism. The scale draws largely from the colorblind racial attitudes scale, which measures the belief that race does not affect one’s life chances (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Lilly, Duran, Lee and Browne2000). Colorblind racial attitudes are problematic as race still plays a large role in determining life outcomes (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Lilly, Duran, Lee and Browne2000; Schaffner et al., Reference Schaffner, MacWilliams and Nteta2018). The two items used to measure colorblind racial attitudes are:

1. White people in the U.S. have certain advantages because of the color of their skin.

2. Racial problems in the U.S. are rare, isolated situations.

But a scale of racism that measures only one’s awareness of racial inequality is lacking (DeSante and Smith, Reference DeSante and Smith2016; Schaffner et al., Reference Schaffner, MacWilliams and Nteta2018). Thus, a third item, drawn from the Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites battery (Poteat and Spanierman, Reference Poteat and Spanierman2008; Spanierman and Heppner, Reference Spanierman and Heppner2004; Spanierman et al., Reference Spanierman, Paul Poteat, Beer and Armstrong2006) is used to measure the degree of empathy individuals feel about racial inequalities:

3. I am angry that racism exists.

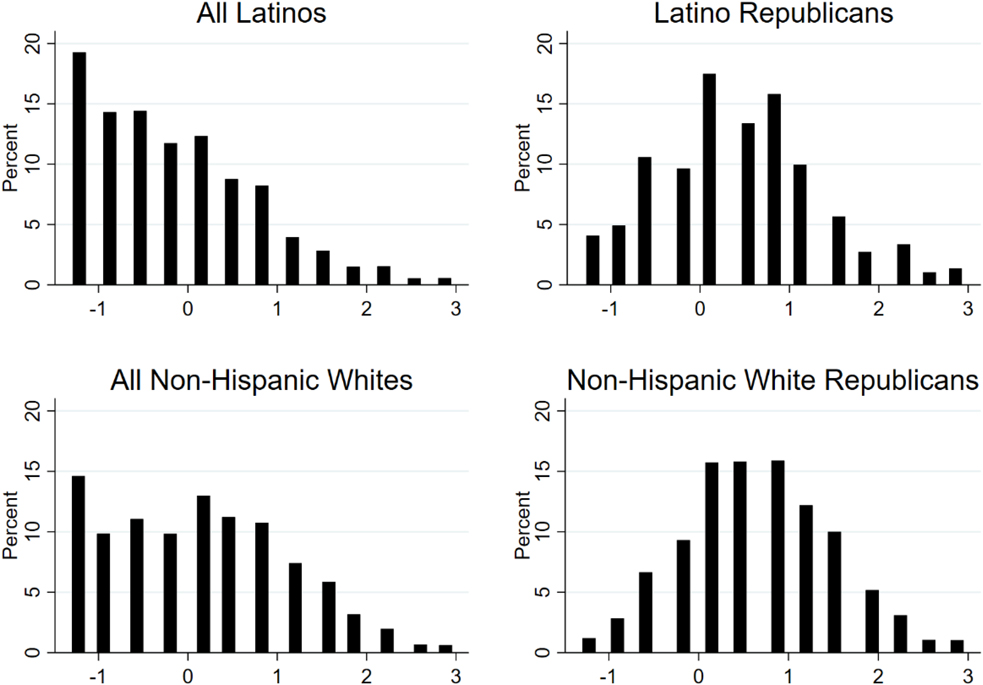

On each of these three items, respondents used a five-point scale to measure how much they agreed or disagreed with each statement (strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree). Responses to these items were scaled and standardized to create a measure of denial of racism with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Negative scores on the denial of racism scale signify that the respondent is more acknowledging of racism, while positive scores signify the respondent is more denying of racism. The denial of racism scale has an alpha of 0.67 for non-Hispanic Whites, and .63 for Latinos. Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses of denial of racism, with all Latinos and Latino Republicans on the first row, and all Whites and White Republicans on the second row. Table 1 shows the average values of denial of racism for Latinos, Whites, Latino Republicans, and White Republicans. As one might expect, Latinos have a lower mean denial of racism than Whites, and Latino Republicans have a lower mean denial of racism than White Republicans. Latinos at large are the only observed group to have a negative mean denial of racism, indicating that most Latinos fall below the mean denial of racism.

Fig. 1. Distribution of Latinos and Whites on denial of racism scale.

Table 1. Average values of denial of racism.

Values are standardized. Standard errors in parentheses.

Figure 1 shows that 40.23% of Latinos are above the mean score on the denial of racism scale, and only 11.58% of Latinos score above one. While only a relatively small number of Latinos will have their vote choice for Trump increased by a significant amount, it is important to examine the power of denial of racism relative to party identification, which the literature tells us should be a strong predictor of support for Trump (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Lewis-Beck et al., Reference Lewis-Beck, Jacoby, Norpoth and Weisberg2008). In the 2016 CCES, only 17.09% of Latinos identify as Republicans. Per the post-estimation simulations in Table 4, a Latino who identifies as an independent has a 31.9% chance of voting for Trump. Identifying as a Republican and holding all other variables at their observed values increases the likelihood a Latino will vote for Trump from 31.9% to 46.6%. If we assume that only 46.6% of Latino Republicans are voting for Trump, that doesn’t account for even one-third of the 30% of Latinos who voted for Trump. Something else beyond Republican party identification must be accounting for Trump’s share of the Latino vote, and I argue that denial of racism is an important part of that explanation.

For those Latinos who score above one on the denial of racism scale, their probability of voting for Trump increases by a minimum of 14.1%; in other words, for these Latinos, their denial of racism has nearly as much predictive power when predicting vote choice for Trump as Republican party identification, as it increases their likelihood of voting for Trump to at least 46%. For those Latinos who score above 1.5 on the denial of racism scale, their probability of voting for Trump increases by a minimum of 22.6%, at which point they become more likely to vote for Trump than Clinton. As a point of comparison, even Republican Latinos are still more likely to vote for Clinton than Trump. To be clear, relatively few Latinos will have their denial of racism increase their likelihood of voting for Trump by a large amount, but per Table 4, only slightly more Latinos will have their vote choice influenced by Republican party identification. So, while denial of racism likely only influenced the vote choice of a relatively small number of Latinos, it is important to remember that only 30% of all Latinos who voted did so for Trump.

The limits of the data prevent a full exploration of what predicts Latino denial of racism, but the available data allow for exploratory analyses. In these analyses, I control for multiple variables given that what predicts denial of racism is an unexplored topic. I control for age, as older adults have been shown to express more prejudice than younger adults (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, von Hippel and Radvansky2009), as well as income, as individuals with higher incomes have been found to have lower levels of prejudice (Carvacho et al., Reference Carvacho, Zick, Haye, González, Manzi, Kocik and Bertl2013). I control for education as well because, while individuals with higher levels of education have been shown to report lower levels of explicit racism, they are more likely to score higher on implicit measures of racism (Kuppens and Spears, Reference Kuppens and Spears2014). While few differences in racial attitudes have been found among White men and women (Hughes and Tuch, Reference Hughes and Tuch2003), I control for gender as there may be differences in Latino denial of racism. I also control for national origin group, using Cuban as the reference category, as the various racial hierarchies that exist across Latin America may influence Latino denial of racism differently for each group in the United States (Telles et al., Reference Telles, Flores and Urrea-Giraldo2015). There may also be differences among national origin groups when predicting support for Trump, as research suggests non-Mexican heritage Latinos supported Trump at slightly higher levels than Mexican heritage Latinos (Garcia-Rios et al., Reference Garcia-Rios, Francisco and Bryan2018).

There may be an immigration gap in how Latinos perceive discrimination, as immigrant Latinos are much less likely to report experiencing discrimination (Florido Reference Florido2017). Neighborhood demographics could also influence one’s denial of racism, as Gans (Reference Gans2012) suggests that minorities who live in mostly White neighborhoods may be pushed to deny racism to not draw attention to their otherness. Research has shown ideological conservatives are more likely than liberals to display racial prejudice (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Phillip E. Tetlock and Kendrick1991), while more recent work suggests a correlation between anti-immigrant sentiment and racial resentment (Ingraham 2018). I control for identifying as Born Again, identifying as Protestant, and religious attendance, as a correlation between religious fundamentalism, and prejudice has been demonstrated (Allport and Ross, Reference Allport and Ross1967; Altemeyer and Hunsberger, Reference Altemeyer and Hunsberger1992; Hall et al., 2010; Hunsberger and Jackson, Reference Hunsberger and Jackson2005). Finally, I control for Republican and Democratic party identification with independents as the reference category given the Republican Party’s history of racial appeals, coded and explicit, dating back to Barry Goldwater (Carr Reference Carr1997; Kousser Reference Kousser2000; López Reference López2015).

Table 2 contains four OLS models predicting denial of racism among Latinos. Model 1, a demographic model, excludes measures of party identification as, although Donald P. Green et al. (2003) argue party identification is a stable construct, I cannot definitively say that partisan identification predates denial of racism in Latinos. In Model 1, being male and older are positively associated with denial of racism. Although Michael Hughes and Steven A. Tuch (2003) found no significant differences between White males and females on the racial resentment scale, it seems that Latino males are more likely to have higher levels of denial of racism than Latino females. While being older is associated with higher levels of denial of racism among Latinos, Model 1 suggests that no relationship exists between a Latino’s immigration generation and their level of denial of racism. This finding runs counter to Adrian Florido’s (Reference Florido2017) work suggesting that immigrant Latinos were more likely than U.S.-born Latinos to deny racism, but there is no clear consensus suggesting that foreign-born Latinos deny racism more than U.S.-born Latinos, as Rojas-Sosa (Reference Rojas-Sosa2016) demonstrates U.S.-born Latinos deny racism as well. Latinos with middle and high incomes are not significantly different than those with low incomes when predicting denial of racism, but not reporting one’s income is positively associated with higher levels of denial of racism. Higher levels of education are negatively associated with denial of racism, which runs counter to Tom Kuppens and Russell Sears’ (2014) work, and being Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Other Hispanic American are associated with lower levels of denial of racism relative to being Cuban American.

Table 2. OLS regression model predicting denial of racism among Latinos.

Robust standard errors in parentheses

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

In Model 2, which controls for ideology and anti-immigrant attitudes, being older is no longer a statistically significant predictor of denial of racism among Latinos, but all the other significant variables from Model 1 retain their significance and previous positive or negative associations. Identifying as a conservative is positively associated with denial of racism among Latinos, while identifying as a liberal is negatively associated with denial of racism. Although the relationship between denial of racism and ideology has not been previously studied, these results suggest denial of racism operates similarly to other forms of prejudice studied in the literature (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Phillip E. Tetlock and Kendrick1991). Anti-immigrant sentiment is also positively associated with denial of racism, which aligns with findings demonstrating a link between racial resentment and anti-immigrant attitudes (Ingraham Reference Ingraham2018). In Model 3, which controls for identifying as Born Again, identifying as Protestant, and religious attendance, all the significant variables from Model 2 retain and their significance and associations. None of the religious controls are statistically significant predictors of denial of racism among Latinos, which runs counter to the literature’s findings that religious fundamentalism is associated with increased prejudice (Hall et al., 2010; Hunsberger and Jackson, Reference Hunsberger and Jackson2005).

In Model 4, which controls for party identification, results are substantively similar to Model 3, although identifying as a Hispanic other than Puerto Rican or Mexican, relative to identifying as a Cuban, is no longer a statistically significant predictor of denial of racism. These results suggest that relative to other Hispanic Americans, those of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent face different, perhaps more racialized, experiences that lead to lower levels of denial of racism. Relative to independent identifiers, being a Republican is positively associated with denial of racism, while being a Democrat is negatively associated with denial of racism. This finding is not surprising given the Republican Party’s history of racial appeals (Carr Reference Carr1997; Kousser Reference Kousser2000; López Reference López2015). I reiterate these models are exploratory analyses, as they lack measures of American identity, Latino linked fate, and skin color, which could potentially play a large role in predicting Latino denial of racism. Future research should investigate the role these variables play in predicting Latino denial of racism.

For the article’s main analyses, I will use logistic regressions predicting support for the Republican candidate for president in a given election. To test alternative hypotheses for why Latinos might support Trump or Romney, I will control for numerous rival explanations based on the literature. Beyond partisanship and ideology, which the literature suggests should be strong predictors of vote choice (Abrajano et al., Reference Abrajano, Michael Alvarez and Nagler2008; Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Lewis-Beck et al., Reference Lewis-Beck, Jacoby, Norpoth and Weisberg2008), I control for income, which the literature argues is not influential for Latinos (Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003; Uhlaner and Garcia, Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Bowler2005). I control for education as there is no clear consensus on the importance of education to Latino vote choice (Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003; Uhlaner and Garcia, Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Bowler2005). As Gans (Reference Gans2012) suggests that a Latino’s local context may influence their desire to support a Republican candidate, I control for region using the four Census regions with the west as the reference category, as well as ZIP Code level demographics based on the 2014 American Community Survey.

As there is a gender gap in partisan affiliation among Latinos, with Latinas being slightly more likely to identify as Democrats than Latinos (Pew Research Center 2018), I control for gender using those who identify as female as the reference category. I control for age and generation as research suggests older, immigrant Latinos are less likely to vote Republican than younger and third generation Latinos (Nuño Reference Nuño2007; DeSipio and Uhlaner, Reference DeSipio and Uhlaner2007). Controlling for national origin, with Cuban as the reference category, is also important as Cubans are more likely than other Latinos to vote Republican (Alvarez and García Bedolla, Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003; Uhlaner and Garcia, Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Bowler2005). As the literature suggests Protestants and Born-Again Christians are more likely to vote Republican than other denominations, I control for these identifiers. I also control for religious attendance, as recent surveys suggest those who attended religious services weekly or more, regardless of denomination, were more likely to vote for Trump than not (Smith and Martínez, Reference Smith and Martínez2016).

I control for political knowledge, as research suggests that for Latinos with lower political knowledge, partisan preferences are particularly important in determining vote choice (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Pantoja and Segura2006). Finally, I control for anti-immigrant sentiment, as Basler (Reference Basler2008) shows that for some Latinos, being anti-immigrant is a litmus test for inclusion into the Republican Party. Beyond these individual controls and alternative explanations, I also test for several interactions with denial of racism. I interact denial of racism and party identification, with identifying an independent serving as the reference category, as being Republican might amplify the effect of denial of racism on one’s support for Trump, while being a Democrat may have the opposite effect. Similarly, I interact denial of racism and anti-immigrant sentiment, as among those who deny racism, those with anti-immigrant sentiments might be even more likely to support Trump given his rhetoric, while those who deny racism but are not anti-immigrant may be less likely to support Trump. Lastly, I interact denial of racism and my three religious measures, as Robert P. Jones (Reference Jones2017) finds that relative to minority Protestants and Evangelicals, White Protestants and Evangelicals perceived much less discrimination against immigrants and Blacks. When taking this finding into account with the literature linking religious fundamentalism and prejudice (Allport and Ross, Reference Allport and Ross1967; Altemeyer and Hunsberger, Reference Altemeyer and Hunsberger1992), it may be the case that religious fundamentalism and denial of racism interact to increase support for Trump beyond only being a religious fundamentalist or racism denier.

Coding for these variables is available in the Appendix. Supplementary models predicting Latino support for various candidates in the 2016 Republican primary use the same control variables.

RESULTS

Table 3 shows the results of a logistic regression predicting Latino support for Donald Trump with coefficients displayed as odds ratios. Despite his anti-Mexican rhetoric, we can see that Trump did not perform significantly worse among Mexicans than other Hispanics. In fact, there are no statistically significant differences in support for Trump among Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Other Hispanics relative to Cubans. Protestant Latinos were about twice as likely as non-Protestant Latinos to vote for Trump, which is consistent with the literature (Jones-Correa and Leal, Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001; Kelly and Kelly, Reference Kelly and Kelly2005; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2014), but Born-Again Latinos are not discernible from non-Born-Again Latinos when it comes to their likelihood of supporting Trump. On the topic of religious attendance, my findings support those of Gregory A. Smith and Jessica Martínez (2016), who found that regardless of religious denomination, higher levels of religious service attendance were associated with an increased likelihood of supporting Trump.

Table 3. The association between Latino denial of racism and the odds of voting for Trump.

Entries are odds ratios derived from a logistic regression with robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

Regarding demographics, neither age nor generation were significant predictors of support for Trump. The lack of predictive power for generation is surprising, as given Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric, one might expect immigrant Latinos to be less likely to vote for Trump thanU.S.-born Latinos. Echoing Carole J. Uhlaner and Flaviano Chris Garcia (2005), I find that education was not a statistically significant predictor of Latino vote choice, and like Alvarez and García Bedolla (Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003) and Uhlaner and Garcia (Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Bowler2005), I find that income is not a statically significant predictor of presidential vote choice. Controlling for environmental effects at the regional level does not produce statistically significant differences, but at the local level, Latinos who lived in ZIP codes with higher concentrations of Whites were slightly more likely to vote for Trump, while those who lived in ZIP codes with higher concentrations of Blacks were slightly less likely to vote for Trump.

On immigration, Latinos who favored deporting all illegal immigrants were nearly three times as likely to support Trump as those who favored any other policy on immigration. Republicans were nearly five times more likely than independents to vote for Trump, while Democrats and ideological liberals were much less likely to vote for Trump. Interestingly, ideological conservatives were not statistically different than moderates when it comes to their likelihood of voting for Trump. As Hypothesis 1 predicted, denial of racism was positively associated with support for Trump, as was the interaction of denial of racism and identifying as Protestant. Protestants who denied racism were more than twice as likely to support Trump as non-Protestants who denied racism, while Born-Again Latinos who deny racism were half as likely as non-Born-Again Latinos who deny racism to support Trump. Interacting denial of racism and partisanship was not a statistically significant predictor of support for Trump, which suggests that a Latino Republican who denies racism is not more likely to vote for Trump than a Latino Democrat or independent who denies racism. This makes sense given recent research demonstrating that racial attitudes and party identification have become conflated for many voters (Tesler Reference Tesler2016).

To examine the relative influence of the predictors, we can look at average marginal effects for the strongest predictors from Table 3. Table 4 shows that identifying as a Republican increases the probability a Latino will vote for Trump from 0.280 to 0.447, an increase of 0.167. Having anti-immigrant attitudes increases the probability a Latino will vote for Trump from 0.29 to 0.384, an increase of 0.094. Moving from the lowest level of denial of racism to the highest level of denial of racism increases the probability a Latino will vote for Trump from 0.139 to 0.897, an increase of 0.757. Clearly, denial of racism is the strongest predictor of Latino support for Trump as moving the variable from its minimum to its maximum more than quintuples one’s probability of voting for Trump.

Table 4. Average marginal effects for selected variables predicting Latino vote for Trump.

Average marginal effects based on model in Table 3 while holding all other variables at their observed values.

While identifying as a Protestant increases the likelihood of voting for Trump by a relatively small 0.058, identifying as a Protestant and moving from the lowest to highest level of denial of racism increases a Latino’s likelihood of supporting Trump from 0.243 to 0.563, an increase of 0.320. On the other hand, identifying as Born-Again and moving from the lowest to the highest level of denial of racism decreases a Latino’s likelihood of voting for Trump from 0.390 to 0.190, a decrease of 0.200. These results suggest that the interaction of denial of racism and identifying as Protestant produce more support for Trump than identifying as Protestant alone, but that increase in support for Trump is still less than the increase from denial of racism alone. Overall, identifying as Protestant or Born-Again reduces the amount of support high levels of denial of racism would engender for Trump, but Born-Again identification is a much more powerful moderator of denial of racism than Protestant identification.

One might argue that the predictive power of denial of racism is being influenced by extreme observations, as relatively few Latinos score above 1 on the denial of racism scale. Thus, Table 4 includes a trimmed range for denial of racism from the 5th percentile to the 95th percentile (Long and Freese, 2014). Footnote 2 Even with outliers removed, denial of racism among Latinos remains the strongest predictor of support for Trump as it increases the probability of voting for Trump from 0.139 to 0.713, an increase of 0.574 when moved from its minimum to maximum values. But while denial of racism may be a strong predictor of Latino support for Trump, was it a strong predictor of Latino support for Romney in 2012?

Table 5 shows the results of a logistic regression predicting support for Romney with coefficients displayed as odds ratios. The results are substantively similar to the model predicting Latino support for Trump, although age and identifying as a conservative, which did not predict support for Trump, are positively associated with Latino support for Romney. Being anti-immigrant and Protestant are positively associated with support for Romney, but to a lesser degree than support for Trump. Identifying as Born-Again is not a statistically significant predictor of support Romney, nor is neighborhood composition. In support of Hypothesis 2, denial of racism is positively associated with Latino support for Romney, albeit less so than with support for Trump; however, none of the interactions of denial of racism and partisanship or religious fundamentalism are statistically significant predictors of support for Romney.

Table 5. The association between Latino denial of racism and the odds of voting for Romney.

Entries are odds ratios derived from a logistic regression with robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

A table showing the average marginal effects for partisanship, denial of racism, and anti-immigrant attitudes for the model predicting Latino support for Romney is available in the Appendix. Identifying as a Republican increases the probability a Latino will vote for Romney from 0.223 to 0.409, an increase of 0.186. Having anti-immigrant attitudes increases the probability a Latino will vote for Romney from 0.264 to 0.307, an increase of 0.045. Moving from the lowest level of denial of racism to the highest level increases the probability a Latino will vote for Romney from 0.185 to 0.515, an increase of 0.302. Trimming the range on denial of racism to look at the range from the 5th percentile to the 95th percentile increases the probability a Latino will vote for Romney from 0.185 to 0.388, an increase of 0.203. Denial of racism has much less predictive power in 2012 than in 2016, but denial of racism still has more predictive power than partisanship in predicting support for the Republican candidate in 2012. When predicting Latino support for Romney, denial of racism is the only variable that, when moved from its minimum to maximum values, makes a Latino more likely to vote for Romney than Obama.

Similar models for non-Hispanic Whites suggest that denial of racism has also supplanted partisanship as the strongest predictor of White vote choice for race-baiting, Republican candidates. Table 6 shows models predicting White vote choice for Romney in 2012 and Trump in 2016. As Table 6 shows, partisanship, ideology, religious attendance, and anti-immigrant attitudes are strong predictors of support for the Republican candidate for president in 2012 and 2016. Denial of racism is also positively associated with support for Romney and Trump among Whites, although it is much stronger predictor of support for Trump than Romney. Although none of the interactions between denial of racism and partisanship or religious fundamentalism are significant predictors of support for Romney, the interaction of denial of racism and partisanship suggest some interesting findings. Relative to independents with high levels of denial of racism, White partisans with high levels of denial of racism are less likely to support to Trump. These findings can be interpreted as denial of racism increasing support for Trump most among non-partisans who, the literature suggests, may rely more on candidate cues than partisanship at the ballot box (Wattenberg Reference Wattenberg1991).

Table 6. The association between White denial of racism and the odds of voting for Republican presidential candidates.

Entries are odds ratios derived from a logistic regression with robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

Table 7 shows the average marginal effects for selected variables from the models in Table 6. In 2012, Republican partisanship increases the probability of voting for Romney from 0.475 to 0.607, an increase of 0.133. Denial of racism increases the probability of voting for Romney from 0.360 to 0.751, an increase of 0.390. Trimming the range on denial of racism to look at the range from the 5th percentile to the 95th percentile increases the probability an individual will vote for Romney from 0.360 to 0.664, an increase of 0.304. For Whites in 2016, Republican partisanship remains relatively stable, increasing the probability of voting for Trump from 0.539 to 0.665, an increase of 0.126. Denial of racism in 2016 increases the probability of voting for Trump from 0.267 to 0.971, a substantial increase of 0.704. Trimming the range on denial of racism still produces a large increase of 0.611 in the probability of voting for Trump, increasing the probability from 0.267 to 0.877. Relative to identifying as an independent, moving the denial of racism scale from its minimum to maximum values for a Republican decreases the probability of voting for Trump from 0.602 to 0.514, a decrease of 0.089. For Democrats, moving the denial of racism scale from its minimum to maximum values decreases the probability of voting for Trump from 0.627 to 0.452, a decrease of 0.174.

Table 7. Average marginal effects for selected variables (Whites).

Average marginal effects based on models in Table 5 while holding all other variables at their observed values.

These findings suggest that from 2012 to 2016, the strength of denial of racism as a predictor of support for race-baiting, Republican candidates greatly increased among Latinos and non-Hispanic Whites. At the same time, the strength of Republican party identification slightly decreased, further demonstrating the importance of denial of racism as a predictor of Latino and White support for Republican candidates. Although data is limited to two elections, the striking difference between the average marginal effects of denial of racism between 2012 and 2016 suggests that as candidates increase their racially charged rhetoric, denial of racism will only increase in predictive power for Latinos and Whites when predicting support for race-baiting candidates. Focusing on Latinos, we can see that in 2012, a trimmed measure of denial of racism was only a marginally stronger predictor of support for the Republican candidate than Republican party identification. In 2016, denial of racism’s strength as a predictor of support for the Republican candidate has more than doubled from 2012; furthermore, as Figure 2 shows, denial of racism is a stronger predictor of supporting the Republican candidate in 2016 for Latinos than for Whites, a reversal from 2012. This finding is supportive of Hypothesis 3, which predicts that denial of racism would be a stronger predictor of support for Trump among Latinos than Whites.

Fig. 2. Average marginal effect of denial of racism (trimmed) on vote choice for Republican presidential candidate in 2012 and 2016.

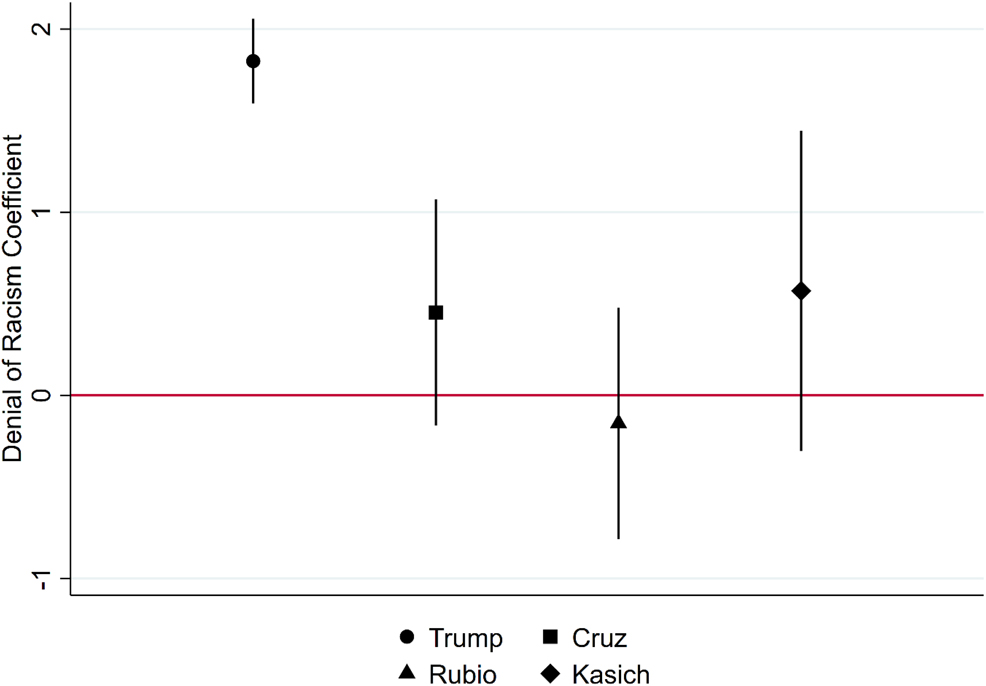

Given that denial of racism is a strong predictor of Latino support for Romney and Trump, one might argue that this would have been the case for any other Republican candidate in an election following the United States’ first Black president. If this is the case, and denial of racism has more to do with support for Republican candidates specifically than race-baiting candidates in general, denial of racism should be positively associated with support for any of the 2016 Republican primary candidates other than Donald Trump. As the 2016 CCES asked respondents who they voted for in the 2016 Republican primaries, I can examine whether this is the case. As a robustness check, I examine whether denial of racism is a predictor of Latino support for any of the other Republican primary candidates in the 2016 CCES. I find that denial of racism is only associated with support for Trump, which fits my argument as well as the findings of the broader literature on racial appeals and denial of racism (Basler Reference Basler2008; Gans Reference Gans2012). Figure 3 presents these results. See Table A3 in the appendix for the full models.

Fig. 3. Association between denial of racism and support for Republican primary candidates among Latinos.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a nationally representative survey, I have shown evidence suggesting that for Latinos, denial of racism was the strongest predictor of support for both Mitt Romney and Donald Trump. When predicting support for Romney, denial of racism among Latinos is only a slightly stronger predictor than partisanship once extreme outliers are removed. However, when predicting Latino support for Trump, the average marginal effect of denial of racism is nearly four times that of partisanship when extreme outliers are trimmed. In fact, excluding interactions with denial of racism, denial of racism is the only variable in my model that increases the probability a Latino will vote for Trump to above 50% when moved from its minimum to maximum. Thus, these findings suggest that Latinos did not vote for Trump despite his racial rhetoric, but because of it.

I also found evidence suggesting that Latinos supported Trump (and Romney to a lesser degree) for largely the same reason non-Hispanic Whites did: denial of racism. Models predicting White support for Trump show that denial of racism had the largest average marginal effect of all predictors, increasing the probability of voting for Trump by 0.378 when moving from its trimmed minimum to its trimmed maximum. At 0.574, denial of racism has a larger trimmed average marginal effect for Latinos than Whites when predicting support for Trump. This suggests that denial of racism is doing much more work for Latinos than Whites when it comes to influencing vote choice for Trump, which makes sense given Trump’s low share of the Latino vote, and the dearth of reasons for a why Latino would vote for Trump.

It may seem counterintuitive to suggest that as candidates deploy racial rhetoric, the Latinos most likely to support them are those who most strongly deny racism. But as the literature suggests, many Latinos who buy into the colorblind ideology and deny racism may be doing so for instrumental reasons (Gans Reference Gans2012; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; O’Brien Reference O’Brien and Odell Korgen2017; Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016). Basler (Reference Basler2008) found that in response to a threat to Latinos in the form of California’s Proposition 187, many Mexican Americans who voted in favor of the restrictionist policy did so in hopes of signaling their allegiance to Whites while separating themselves from other Latinos.

I argue that the 2016 presidential election, in which Trump paved his path to the White House by attacking Mexicans and immigrants, created an opportunity for Latinos to climb the racial hierarchy. Adam Serwer, in The Atlantic, wrote: “Trump’s supporters backed a time-honored American political tradition, disavowing racism while promising to enact a broad agenda of discrimination” (2017). By denying the racism in Trump’s rhetoric, and in the United States at large, Latinos could act like Trump’s White supporters, and join in the aforementioned political tradition, in the hopes of preventing any discrimination aimed at themselves (Basler Reference Basler2008; Gans Reference Gans2012; Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016).

As denial of racism is a new measure, much work remains to investigate its correlates and predictors, as well as to make comparisons to other measures of prejudice. A correlation matrix with denial of racism and other key variables from the models is available in the Appendix and suggests that denial of racism is positively correlated with Republican party identification and negatively correlated with Democratic party identification, although these correlations are both weak. Denial of racism is also positively correlated with Protestant and Born-Again identification, as well as anti-immigrant sentiment, but these correlations are also weak. Tests for multicollinearity were performed on the models in Table 3 and Table 5, and no variable had a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) greater than ten, a commonly used threshold for a high multicollinearity (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2007).

Contrary to the literature on religious fundamentalism and prejudice, (Allport and Ross, Reference Allport and Ross1967; Altemeyer and Hunsberger, Reference Altemeyer and Hunsberger1992; Hall et al., 2010; Hunsberger and Jackson, Reference Hunsberger and Jackson2005), denial of racism interacts with Protestant and Born-Again identifiers in different ways. While Latino Protestants who deny racism were more than twice as likely to support Trump as non-Protestants who deny racism, Born-Again Latinos who deny racism were half as likely to support Trump than non-Born-Again Latinos who deny racism. As these interactions are only significant predictors of support for Trump and not Romney, this suggests that in the presence of candidate who uses racial rhetoric to the degree Trump did, Born-Again affiliation will dampen the support denial of racism would normally engender, while Protestant affiliation will increase support; however, high levels of denial of racism among Protestant and Born-Again identifiers produce less support for Trump than high levels of denial of racism alone, suggesting that religious affiliation has a moderating effect on the support denial of racism creates for Trump. As these interactions are significant for Latinos but not Whites, they suggest that denial of racism, as well as the interaction of denial of racism and religious affiliation, operate differently for Latinos than Whites, and possibly other racial and ethnic groups as well.

I find additional differences between Latinos and Whites when it comes to the interaction of partisanship and denial of racism. While partisanship and denial of racism don’t interact for Latinos in any significant way when predicting support for Romney or Trump, for Whites, both Democrats and Republicans who were high in denial of racism were less likely to vote for Trump than independents who were high in denial of racism. These results suggest that for Whites, affiliation with a major party reduced the support denial of racism generated for Trump. Taking all these findings into account, I believe that for Latinos denial of racism, partisanship, and anti-immigrant sentiment are all separate attitudinal strands. Partisanship and denial of racism fail to produce any significant interactions, as do denial of racism and anti-immigrant sentiment. Denial of racism and religious affiliation may be linked, as the literature on religious fundamentalism suggests (Hall et al., 2010; Hunsberger and Jackson, Reference Hunsberger and Jackson2005), but Protestant and Born-Again affiliation interact with denial of racism in distinct ways. Future research should investigate why some religious affiliations temper the effects of denial of racism more than others.

Although the CCES does not contain measures of racial resentment, we can examine the 2012 and 2016 American National Election Studies (ANES) to see how similarly racial resentment predicts support for Romney and Trump. These models are available in the Appendix and provide substantively similar results despite using racial resentment in place of denial of racism. Footnote 3 While one might argue that these findings suggest racial resentment and denial of racism are measuring the same concept, I contend they are theoretically distinct. Racial resentment has been shown to measure a conjunction of anti-Black feelings and American moral traditionalism (Carmines Reference Carmines, Sniderman and Easter2011; Kinder and Sears, Reference Kinder and Sears1981), while denial of racism is largely based on the colorblind racism scale (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Lilly, Duran, Lee and Browne2000), which measure views on racial inequality. Given that Trump’s attacks were focused on Latinos and not Blacks, Trump likely drew support among racially resentful Latinos largely due to his status as a Republican. If this is the case, Trump should not have received much more support than Romney among racially resentful Latinos, which is unlike the large increase in support this paper suggests Trump received relative to Romney from Latinos who deny racism.

Comparing the 2012 and 2016 ANES and CCES models, the biggest takeaway is that while racial resentment remains a consistent predictor of support for the Republican candidate from 2012 to 2016, the predictive power of denial of racism more than quadruples during the same period. This paper, and the literature on Latino denial of racism (Basler Reference Basler2008; Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016), argue that denial of racism for Latinos emerges in the face of a threat as a means of self-preservation. I contend that the increase in denial of racism’s power from 2012 to 2016, as well as denial of racism only predicting support for Trump in the 2016 primaries and not any other Republican candidates, support the conception of denial of racism as theoretically distinct from racial resentment. While I acknowledge that denial of racism for some Latinos may include adopting or expressing anti-Black sentiment, the literature does not suggest that racial resentment, and anti-Black sentiment at large, are key components of denial of racism (Basler Reference Basler2008; Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016). For a more conclusive comparison, future research should include measures of racial resentment and denial of racism on the same survey.

For those Latinos who deny racism as a means to climb the racial hierarchy, it makes sense that they would vote for Trump regardless of their partisan attachment. But what happens after the racial rhetoric, and the threat it creates, pass? Do Latinos who voted Republican for the first time after Proposition 187 or the 2016 presidential election continue voting Republican? This would be the most likely case, given the Republican Party’s position on racism in the United States and its history of dog whistle appeals (Carr Reference Carr1997; Kousser Reference Kousser2000; López Reference López2015), as well the continued need for Latinos to signal their allegiance to Whites (Basler Reference Basler2008; Gans Reference Gans2012).

While much has been said about Latinos fleeing the Republican Party since its peak among Latinos under George W. Bush, the data show that Republican partisanship among Latinos has remained relatively static since 2007 (Bouie Reference Bouie2016; Lopez et al., 2016; Yin Reference Yin2016). Any Latino Republicans Romney and Trump may have alienated and driven from the Republican Party with their rhetoric could have been replaced by former Democratic and independent Latinos who are attracted by such appeals and the desire for inclusion by Whites. Future research should investigate whether such a switch among Latino voters has occurred.

CONCLUSION

Like other recent work, this research continues to show the relative decline of party identification as an important predictor of Latino vote choice (Collingwood et al., Reference Collingwood, Barreto and Garcia-Rios2014; Hajnal and Lee, Reference Hajnal and Lee2011). Just as scholars of Latino politics have adapted and found new ways to predict Latino vote choice, they must accept that some Latinos will vote Republican, and endeavor to find out why. Rather than simply assuming the Republican Party will eventually be devoid of Latinos in a fashion equivalent to African Americans (Frymer Reference Frymer2010), scholars should further investigate the intersection of Latino perceptions of racism and vote choice, especially at a time when explicit racial rhetoric may be increasing (Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Neuner and Matthew Vandenbroek2018). The dearth of literature in the social sciences on racial attitudes among people of color hurts our understanding of minority vote choice and prevents us from fully understanding why certain groups may seemingly vote against their own interests. As the literature has shown, Latinos can exhibit racism to greater degrees than non-Hispanic Whites in some cases (McClain and Tauber, Reference McClain and Tauber1998). As this work and others have shown, for some Latinos it may make sense to deny racism exists at all in the hope that this will allow to escape discrimination from Whites (Basler Reference Basler2008; Gans Reference Gans2012; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; Rojas-Sosa Reference Rojas-Sosa2016).

Based on the literature, Latinos should be more likely than Asian and African Americans to embrace denial of racism given the phenotypical and cultural similarities between some Latinos and non-Hispanic Whites (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017; Gans Reference Gans2012). Nonetheless, future work should continue investigating denial of racism and racial resentment among Latino, Asian, and African Americans, especially as predictors of support for race-baiting candidates and race-based issues at large. If denial of racism predicts vote choice, might it also predict support for Black Lives Matter, punitive crime policy, or affirmative action?

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X19000328