Introduction

Disasters occur when damage and dysfunction from events overwhelm local medical resources. Often, during disasters, children are harmed disproportionately. Although the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires disaster education in pediatric and emergency medicine residencies, there is no standardized, widely-used pediatric disaster medicine (PDM) curriculum. 1 , 2 Components of a PDM curriculum include: (1) preparedness; (2) knowledge of the response system; (3) triage and treatment; (4) mental health; and (5) experiential education.Reference Ablah, Tinius and Konda 3 , Reference Behar, Upperman, Ramirez, Dorey and Nager 4

Triage concepts broaden the scope of PDM. Novice learners can pursue triage knowledge and skills early in PDM training. In normal triage, patients are sorted based on acuity and likelihood of benefiting from treatment. In times of disaster, however, priority is given to salvageable patients who require immediate treatment. This change in priority requires a shift in patient care, and is counter to daily practice. Many triage tools exist to facilitate this shift in care. There are few data to support the superiority of one triage algorithm over another.

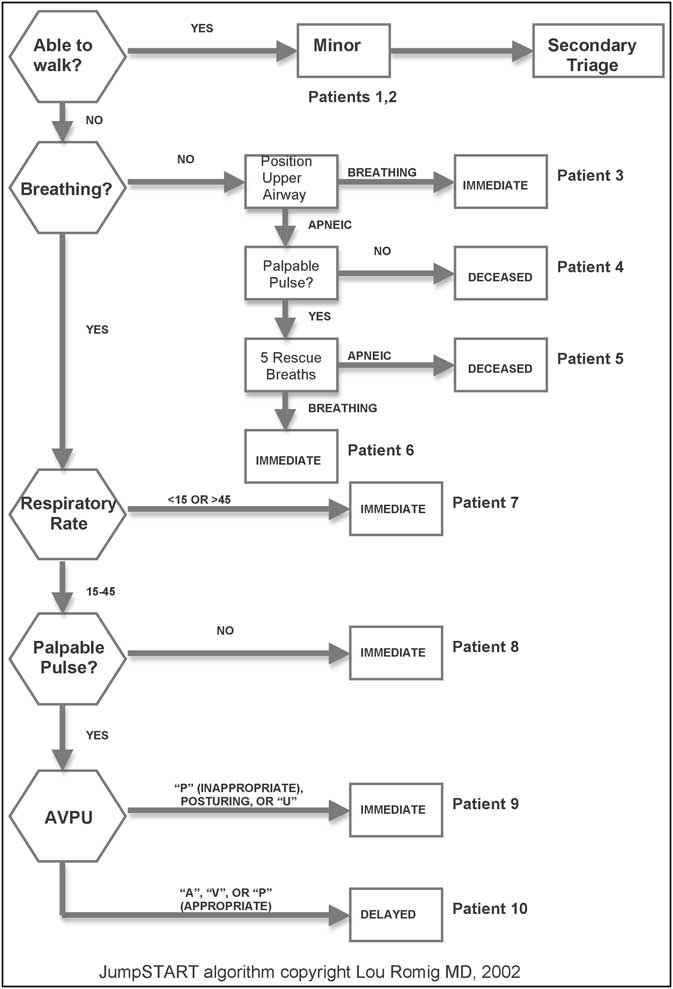

The JumpSTART algorithmReference Romig 5 is used both federally and internationally. The algorithm is simple to learn, and allows for a rapid sorting of victims. The JumpSTART algorithm was the first triage tool designed with consideration of pediatric physiology. Introduced for prehospital use, this algorithm sorts patients into acuity categories: Red (Immediate); Yellow (Delayed), Green (Minor); and Black (Deceased). The tool provides an algorithmic approach to triage, and requires the user to judge a patient's triage category quickly, based on limited clinical data.

Most pediatric residents have little triage experience, yet in a disaster, they will be expected to triage patients arriving at the hospital.Reference Nie, Tang and Lau 6 , Reference Galante, Jacoby and Anderson 7 Disasters are high-stakes but low-frequency events. Pediatric residency training does not provide for experiential learning of disaster medicine, as trainees are not exposed to disaster medicine in the clinical arena. To address this gap in experience, simulation has been reported to be an effective way to learn triage and other PDM skills.Reference Ballow, Behar and Claudius 8 - Reference Timm and Kennebeck 10 Ideally, PDM education should have an experiential component, rather than solely relying on didactic techniques.Reference Kaji, Coates and Fung 11 - Reference Moye, Pesik and Terndrup 13 Additionally, PDM education should be longitudinal rather than a single, stand-alone, educational intervention.

As with other educational techniques, formative evaluation following simulation education is good practice, and enhances learners’ understanding. Structured debriefing helps learners recognize areas in which their performance should be improved, and how their mental models differ from optimal performance.Reference Rudolph, Simon, Raemer and Eppich 14 Structured debriefing is an educational technique used to provide formative evaluation after learners have been observed performing a new skill. Structured debriefing also fosters the process of analogical reasoning, or reflective learning by analogy. Using analogical reasoning, learners analyze a novel situation with comparisons to their prior experiences and education.Reference Gentner 15 The process of structured debriefing and analogical reasoning allows learners to analyze their deficiencies, and leads to improved skill acquisition and retention. In this technique, the learner and the evaluator follow four steps: (1) note gaps between performance and objectives; (2) provide feedback describing the gap between learner performance and optimal performance; (3) discuss the emotional and cognitive reason(s) for the gap; and (4) close the gap through discussion or targeted instruction. The learner then completes additional training, and additional feedback is provided if necessary.

The impact of structured debriefing on triage learning has not been described. The purpose of this study was to measure the efficacy of a multiple-victim simulation in facilitating learners’ acquisition of pediatric disaster medicine (PDM) skills, including the JumpSTART triage algorithm. The hypotheses of the study were: (1) as an intervention, multiple-patient simulation followed by structured debriefing yields a measurable improvement in disaster triage accuracy and simulated patient outcomes; and (2) a novel simulation-based PDM triage curriculum that includes structured debriefing would result in disaster triage skills that are retained for five months.

Methods

Simulations and Scenarios

The PDM triage curriculum included didactic lectures, multiple patient simulations (a school shooting, playground violence, a school bus crash), and a structured debriefing. Moulaged high- and low-fidelity simulation manikins and standardized mock patients portrayed the disaster victims. Victims ranged in age from infancy to school age, with an adult school staff member portraying the ambulatory Triage Level Green patient. The three simulation scenarios each had 10 victims, for a total of 30 simulated victims. Learners encountered a standardized set of patients, but in a different order for each simulation. Each of nine victims represented one of the nine nodes of the JumpSTART algorithm; the tenth victim portrayed a child with special health care needs (CSHCN) (Figure 1). The CSHCN was a wheelchair-dependent, non-verbal male breathing without assistance. A peer or obvious paper sign accompanied the CSHCN, and stated that he was at his baseline level of function.

Figure 1 JumpSTART Pediatric Multiple Casualty Triage with 10 representative simulated patients

Abbreviation: AVPU, audio, verbal, pain, unresponsive

The JumpSTART algorithm was designed for patients ⩽8 years of age. The algorithm was used for all patients, as its variations from the adult START algorithm are minor. The design composition of the victims was vetted by the authors, and by disinterested, independent subject matter experts using a modified Delphi technique. The expected triage category for each of the 30 victims was determined by consensus of the authors and subject matter experts.

Learners and Schedule

The Pediatrics and Combined Internal Medicine/Pediatrics residents at one institution were the learner participants in this study. To assure anonymity, learners were tracked throughout the study with a self-generated, eight-digit, identification code that could not be traced back to the learner. Learners received incentives for completing all aspects of the curriculum and assessment. Incentives included a US $15 Amazon.com gift certificate and a meal at the first learning session, as well as entry into a raffle for an iPod touch (Apple Inc., Cupertino, California USA). Written informed consent was obtained from all learners, and the Human Investigations Committee of the university granted approval for this study.

To allow a high proportion of residents to participate in the training, sessions were planned for six consecutive Fridays from August through October 2009. The pediatric chief residents scheduled learners to leave their daytime clinical responsibilities to attend the sessions in the Simulation Center. Learners visited the Simulation Center three times: (1) a two-hour session consisting of the initial didactic learning, the first simulated disaster as experiential learning, and a structured debriefing; (2) one week later, a 45-minute formative evaluation with a second simulated disaster; and (3) five months later, a 45-minute delayed, summative evaluation with a third simulated event.

Curriculum and Assessment

Baseline triage knowledge was assessed using multiple-choice questions and a survey instrument that have been described previously.Reference Cicero, Blake and Gallant 16 A flow diagram of the curriculum and evaluations is in Figure 2. Of note, the structured debriefing occurred after the didactic session and the first simulation. During the debriefing, learners were encouraged to compare and contrast the simulated patients and their peers’ triage classifications of the patients. Conducting the structured debriefing between the first and second simulations allowed assessment of the learners’ mental models and knowledge gaps, as well as an assessment of the magnitude of improvement in simulated triage performance attributable to the structured debriefing. One week after the structured debriefing, the learners completed the second simulation. The third triage simulation assessed retention of triage knowledge and skills five months after completion of the courses.

Figure 2 Flow diagram of the curriculum and evaluations

Power Calculation and Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was triage accuracy, defined by the learner assigning the correct triage category to the simulated victims. Specifically, the improvement in triage accuracy attributable to the structured debriefing was assessed. In order to detect a 10% improvement in triage accuracy, or one additional patient triaged correctly per 10 disaster victims, a power calculation was performed. Assuming power of 0.8 and α = 0.05, a total of 50 participants allowed the detection of a 10% difference in triage accuracy. 17

Descriptive statistics, including the median and standard deviation of the number of victims properly triaged, were calculated. Additionally, the improvement in triaging patients representing each of the nine nodes of the JumpSTART algorithm (e.g., the number of learners who correctly triaged unresponsive children with normal respiratory and circulation findings) was determined. It was assumed few learners would have prior disaster training or experience, and that the learners’ ability to perform disaster triage was not normally distributed. Therefore, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare scores before and after debriefing. The Wilcoxon signed rank test also was used to compare the triage performance of learners’ post-test simulation and delayed post-test evaluation. Learners served as their own controls. Calculations were performed with Predictive Analytics SoftWare (SPSS, version 18, Chicago, Illinois USA).

Results

In total, 53 of 70 (75.7%) eligible learners (Pediatrics and Combined Internal Medicine/Pediatrics residents) completed the initial didactic learning, the first simulated disaster, and the structured debriefing. The post-graduate year and specialty (categorical Pediatrics or Combined Internal Medicine/Pediatrics) of the participants and all eligible residents are listed in Table 1. Due to scheduling conflicts, there was learner attrition for the post-test and the delayed post-test. The repeat post-test was completed by 50 (94.3%) of the learners who completed the initial didactic learning, the first simulated disaster, and the structured debriefing, and 42 (79.2%) of learners returned for the delayed post-test.

Table 1 Residents participating in the study by residency type and post-graduate year

aIncludes two Pediatrics-Psychiatry Interns

Learner triage accuracy before the structured debriefing, for the post-test, and for the delayed post-test is graphed in Figures 3a-3c. The mean value of the number of patients properly triaged during the pre-test was 6.9/10 (SD = 1.3). The mean value of the number of patients properly triaged during post-test was 8.0 (SD = 1.37, P < .0001). For the delayed post-test, the mean value for triage accuracy was 7.8 (SD = 1.33, P < .0001).

Figure 3a Triage accuracy before the structured debriefing

Figure 3b Triage accuracy one week after structured debriefing

Figure 3c Triage accuracy five months after structured debriefing

In the pre-test, 36 (67.8%) of the learners over-triaged the uninjured CSHCN as Triage Category Red or Yellow. In the post-test after the structured debriefing, 24 (47.1%) of the learners over-triaged a CSHCN and in the delayed post-test, 11 (26.2%) learners over-triaged the CSHCN. Although CSHCN were the most commonly mis-triaged patients in all three scenarios, triage errors decreased as the curriculum progressed.

The second most common trend in triage inaccuracy was under-triage of head-injured, unresponsive patients. During the pre-test, before the structured debriefing, 20 (39.2%) of the learners under-triaged this patient type as a Category Yellow patient, and one learner categorized this non-ambulatory patient as a Triage Category Green. In the post-test after the structured debriefing, 19 (37.2%) of the learners under-triaged the unresponsive, non-ambulatory, head-injured patient, while in the delayed post-test, five (11.0%) of the learners under-triaged (Category Yellow) the unresponsive child with a head injury, while two (4.8%) of the learners declared the patient to be Category Black, despite the presence of vital signs consistent with a Red designation.

Discussion

Two principle findings arise from this study. First, among the 42 residents who completed the entire study, there was sustained, statistically significant improvement in PDM triage accuracy. If simulated triage outcomes are predictive of triage performance during an actual disaster, the curriculum could result in a 10% improvement in triage accuracy. Not only was there an increase immediately after the intervention, but learners also were able to demonstrate competency at a similar level five months after completion of the training. Further, as no educational intervention other than the structured debriefing occurred after the first simulation, much of the improvement was attributable to the structured debriefing. Second, children with special health care needs (CSHCN) and head-injured, unresponsive patients remained difficult for many residents to triage accurately, even after the training.

An important consideration when interpreting the first principal finding is the effects of practice.Reference Talente, Haist and Wilson 18 , Reference McGaghie, Issenberg, Petrusa and Scalese 19 There has been a demonstrated dose-response to simulation education, with improvement in performance resulting merely from repeat exposure to simulation.Reference McGaghie, Issenberg, Petrusa and Scalese 19 There was a risk that the learners’ triage performance would improve because they were returning to the Simulation Center to perform a familiar triage task. To mitigate this risk, children of different sizes were used to represent the nodes of the JumpSTART algorithm in the three simulations. Also, the learners encountered the victims, and the JumpSTART node they represented, in a different order during each simulation. To ensure that any improvement between the pre-test and the post-test could be attributed to simulation and the structured debriefing, no interim educational intervention was provided. Further, skill derived from the practice effect tends to diminish with time,Reference Su, Schmidt, Mann and Zechnich 20 , Reference Berden, Bierens and Willems 21 and performance after courses, such as Pediatric Advanced Life Support, tends to decay after several months.Reference Grant, Marczinski and Menon 22 Thus, the sustained improvement in learner triage performance five months after the training seems unlikely to be due to practice effect.

In regards to the second principal finding, the improper triage of CSHCN and head-injured patients, it is important to consider curriculum and learner factors, as well as the limitations of the study. The difficulty encountered by learners in triaging these patients may lie in the ambiguity of the simulated patients, potentially a limitation of the methods used. For example, when learners adhere to the JumpSTART algorithm, they assess the presence of patients’ pulses and ventilatory rates, which are relatively objective. In patients who are chronically non-ambulatory and nonverbal, it is difficult to determine whether there is an acute change in condition resulting from the event. Care of CSHCN in day-to-day emergencies is challenging,Reference Sutton, Stanley, Babl and Phillips 23 and current PDM strategies may not address adequately the needs of CSHCN. Regarding the head-injured, unresponsive patients of the three simulations, in the pre-test and post-test, the patient was vomiting, while the patient in the delayed post-test was unresponsive. This difference in patient behavior may explain the more frequent mis-triage of head-injured, unresponsive patients in both the pre- and post-tests compared to the delayed post-test. Another explanation is that the curriculum did not emphasize the triage of CSHCN and head-injured patients well enough to ensure proper triage by the learners.

The CHSCN and head-injured patients may have been particularly challenging to the learners for several reasons. They are novel cases within a challenging environment, representing two mental model shifts needed for the learner. The first shift is the use of the JumpSTART algorithm; the second involves the need for mental status assessment in CSHCN and head-injured patients. Mental status is less objectively assessed than ventilatory rate or the presence of pulses. Despite the challenges of CSHCN and head-injured patients, the learners demonstrated improvement in triage accuracy with each simulation. This may reflect that, through analogical reasoning, learners were building an improved mental model of CSHCN and head-injured patient triage.

Limitations

Limitations of the study include the limitations of simulation technology, the use of novel, unvalidated evaluation tools, and “contamination” of learners with PDM education prior to the first simulation. High-fidelity simulation approximates a clinical situation, such as that which may occur during a disaster, but malfunctions (manikins, other hardware, or simulation software), or unrealistic scenarios may thwart learner performance. The simulations were designed to reflect plausible patients encountered during a disaster,Reference Ballow, Behar and Claudius 8 and reflected the JumpSTART tool in the patient design. Further, dedicated Simulation Center personnel ran the simulations for each learner. As learners had PDM triage didactic instruction prior to the first simulation, their performance on the pre-test simulation was likely better than their performance at baseline.

A control group without structured debriefing would have improved the study design and strengthened the assertion that the sustained improvement in learner triage performance was due to the simulation and structured debriefing.

Finally, at the time of this writing, JumpSTART remains the national standard for pediatric disaster triage. Several new algorithms have been suggested, including the Sacco Triage method, which assigns a numeric score to victims using a 15-point scale, and takes into consideration the resource constraints imposed by the disaster.Reference Sacco, Navin and Waddell 24 The author of the JumpSTART algorithm has endorsed the Sacco method on her website. 25 A potential criticism of the Sacco method is that all victims must be triaged before hospital transport decisions are made. Further, when compared to a four-color triage system, a 15-point scale may introduce detrimental complexity at the incident site. Further studies should compare the efficacy of the JumpSTART, the Sacco method, and other triage tools, as well as learner knowledge, skill acquisition, and retention of these strategies.

Conclusion

Structured debriefing leads to significant, durable improvement in residents’ triage accuracy. Structured debriefing is a simple, inexpensive intervention that should be incorporated into pediatric disaster curricula. Further study of structured debriefing in other aspects of PDM, such as treatment and mental health, is warranted.

Abbreviations

- CSHCN:

-

child [or children] with special health care needs

- PDM:

-

pediatric disaster medicine