TOWARD AN EMPIRICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF THE DEFAULT

Though widely employed in linguistics, the notion of the default has not been as well defined as that of (un)marked. Markedness pertains to cross-linguistic conceptual values in oppositions such as singular/plural (number), active/passive (voice), present/past (tense) (Croft, Reference Croft2003:111). Typological approaches have made headway in operational criteria of markedness in showing measurable properties of the unmarked member of a grammatical category (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985:50–58; Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1966:25–55; but see Haspelmath, Reference Haspelmath2006). Unmarked as opposed to marked grammatical values tend to be expressed with fewer morphemes, often as a zero morpheme. They have at least as many morphological distinctions; for example, the singular in English third person personal pronouns has three genders—he, she, it—whereas the plural has one form—they. Unmarked values also have greater distributional potential, as in constructions that occur with the English active voice but not the passive, and, most fundamentally, they are more frequent (Croft, Reference Croft2003:110–117).

The notion of the default has been applied to both grammatical meanings and forms. Default meaning (interpretation) may pertain to a language-particular form (Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:11) or to a cross-linguistic category; for example, the default aspectual meaning of present tense is habitual/generic/stative, whereas of past it is perfective (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151–153). In this article, we are interested in default as applied to a form (expression). In his typological study of tense and aspect systems, Dahl (Reference Dahl1985:19) extended Comrie's (Reference Comrie1976:11) discussion of the default of a given form's meanings to competing forms, distinguishing default from unmarked as follows. Whereas (un)marked status shows up in formal coding—the member of a grammatical opposition encoded with fewer morphemes, most clearly, the zero-coded form—a default expression is the one whose meaning “is felt to be more usual, more normal, less specific” than that of the alternative form (emphasis added). Default status pertains to language-particular forms competing within a functional domain, such as past tense, in a particular speech community. If markedness of a grammatical value is manifested in formal properties, then, in a complementary fashion, default status of an expression is manifested in functional range. For example, it has been argued that in southern European languages “imperfects” rather than “preterits” are the default past expression, because they may be used for not only the imperfective but also the perfective aspect (Thieroff, Reference Thieroff, Werner and Leonid1999; cf. Jakobson, Reference Jakobson1971[1957]:137).

However, we lack empirical tests for this determination. What does a default expression look like in actual language use? In this article, we will show how distribution patterns afford an empirical characterization of a default expression and that default status provides a gauge for advancing grammaticalization. We show, furthermore, that indeterminate reference is a defining component of the default and a locus of change.

Our object of study is the Spanish Present Perfect haber ‘have’ plus Past Participle form. The Present Perfect in most Peninsular varieties (Spain) is involved in an active grammaticalization process, such that both the Present Perfect (1a), henceforth PP, and the Preterit (1b), indicated by PRET in the examples, function as past perfectives (e.g., Pérez Saldanya, Reference Pérez Saldanya, Luis and Bruno2004:205).Footnote 1

(1)

a. ayer he comprado un aire acondicionado y me da calor (BCON014B) ‘yesterday I bought (PP) an air conditioner and I'm getting heat [from it]’

b. Estas son prácticamente igual que las que compramos ayer (CCON013C) ‘These are practically the same as the ones we bought (PRET) yesterday’

How can we determine which of the two forms, the PP or the Preterit, is the default expression of past perfective tense-aspect in this variety?

How does a form that used to be a perfect become the default past perfective exponent? Perfects are relational, signaling a past situation that is related to (the discourse at) speech time and is therefore currently relevant, whereas perfectives report an event “for its own sake” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:54). The change from perfect to perfective use is a generalization of meaning, with loss of the specification of current relevance occurring as speakers aim to frame what they are saying “as though it were highly relevant to current concerns,” which leads to overuse and semantic bleaching (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:86–87, emphasis in original; cf. Dahl & Hedin, Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:391; Haiman, Reference Haiman and William1994; Schwenter & Waltereit, Reference Schwenter and Waltereit2006).

The most widely held view of this process is that perfects gradually move back in temporal distance (see Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1989] for an extensive discussion of this view). In the particular case of the PP in Spain, Schwenter (Reference Schwenter1994a:89–90) showed that the distribution of the PP and Preterit follows a hodiernal ‘today’ vs. prehodiernal ‘before today’ distinction. It is assumed that the PP generalizes from perfect to hodiernal perfective uses and thence to increasingly remote past time situations (e.g., Berschin, Reference Berschin1976; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:101–102; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983; Schwenter, Reference Schwenter1994a, Reference Schwenter1994b; Serrano, Reference Serrano1994).

We will tackle these two questions by employing the variationist comparative method (Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2001:88–102; cf. Tagliamonte, Reference Tagliamonte, Peter, Jack and Natalie2002). Linguistic change is reflected synchronically in dialect differentiation (D. Sankoff, Reference Sankoff and Newmeyer1988a:147); in particular, dialect differences can reflect different degrees of grammaticalization or even different grammaticalization paths (Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán2001:16, cf. Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte1999; Torres Cacoullos, Reference Torres Cacoullos, Gabriele and von Colbe Valeriano2005). In contrast to Peninsular Spanish varieties, in Mexico the Preterit is more frequent than the PP (e.g., Moreno de Alba, Reference Moreno de Alba1978). We will compare the linguistic conditioning of PP and Preterit variation in Peninsular and Mexican data to identify the default past perfective form in each variety.

Our goal is to contribute to a characterization of the notion of the default in empirical terms. Distribution patterns provide evidence for the PP becoming the default exponent of past perfective in Peninsular Spanish. The default expression is the one that is preferred in the most frequent and, crucially, the least specified contexts. The results also suggest a somewhat different trajectory for perfect-to-perfective grammaticalization than the commonly assumed route via remoteness distinctions. The PP's shift to perfective can be found clearly in temporally indeterminate (lacking specific temporal reference) past contexts.

THE PERFECT

Throughout this article, we distinguish between cross-linguistic categories, such as perfect, perfective (denoted by lower case), and the language-specific instantiations of these cross-linguistic categories (denoted by capitalization). In Spanish, the past perfective form is traditionally called the Preterit(e) (pretérito), which is contrasted with the PP, a diachronically younger construction whose terminology in Spanish has varied somewhat according to different grammatical traditions (pretérito perfecto, antepresente, etc.).

Dahl (Reference Dahl1985:132), employing what he termed a “typological questionnaire,” identified a cross-linguistic category called “perfect” centered on four prototypical uses, which Comrie (Reference Comrie1976:56–61) had earlier referred to as distinct types of perfects. The questionnaire items (also used later by the EUROTYP project; see, e.g., Dahl [ed.], Reference Dahl2000) are given in English in Figure 1; the nonfinite verb in capital letters is the target form that respondents were asked to supply in their native language(s).

Figure 1. Uses (types) of perfects (Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:132; cf. Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:56–61).

A defining meaning component of perfects cross-linguistically is current (or present) relevance of a past situation (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:61; Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:52; Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:134; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983:194; Li et al., Reference Li, Thompson, Thompson and Paul1982). Although this concept is mainly left at an intuitive level in the literature, it can be discerned in the four types of perfects presented in (2), each of which (again, intuitively) relate a situation located either wholly or as initiating in the past to utterance time in some fashion. As argued by Dahl and Hedin (Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:391), current relevance is a graded concept. Moreover, the criterion for determining relevance need not be a condition on the world, as in a tangible “continuance of a result,” but rather a condition on the discourse. In other words, speakers present the consequences of a past event as important to what they are saying (Dahl & Hedin, Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:392; cf. Li et al., Reference Li, Thompson, Thompson and Paul1982).

How then is perfect different from perfective? Perfective aspect conveys strictly that the situation is viewed as bounded temporally; thus, cross-linguistically it is used for narrating sequences of discrete events in the past (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:54; Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:5; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983:194; Hopper, Reference Hopper and Talmy1979). Perfects differ from perfectives in that they express detachment from other past situations; hence, perfects are not used for the foregrounded events in sequenced narratives (Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:139; Lindstedt, Reference Lindstedt and Östen2000:366).

The inherent boundedness of the perfective as opposed to the comparatively greater aspectual flexibility of the perfect is also seen in concert with negative polarity. In Mexican Spanish, for instance, a negated PP implies the possibility that the situation can still be realized, whereas the Preterit signals that the situation will never happen (e.g., Company, 2002). In (2), there are co-occurring linguistic and contextual indices of this meaning difference, though presumably the forms themselves convey it. With the PP (2a) an appearance of the person in question is eventually made (as made explicit by ahora sí salió ‘now he did come down’), but with the Preterit (2b), the woman's act of understanding can never be realized because she is a character in a movie.

(2)

a. hace veinte años que yo tengo amistad con la familia y jamás ha salido a la sala, y ahora sí salió (MexCult, 132)

‘I've visited the family for twenty years and he never has come (PP) down to the living room, and now he did’

b. esa tipa nunca entendió el amor de ese muchacho (MexCult, 409)

‘[about a character in a film] that woman never understood (PRET) that young man's love’

Despite such apparently clear meaning differences in some contexts, however, it is common cross-linguistically for forms or constructions that express perfect meaning to extend into the realm of pasts or perfectives (and, concomitantly, relax the prior constraints on perfect meaning, such as current relevance) (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:81–87; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983:195–199). This diachronic process in the Romance languages has been referred to as “aoristic drift” (Squartini & Bertinetto, Reference Squartini, Bertinetto and Östen2000:404), though as Dahl (Reference Dahl1985:139) notes, “the nature of this process is not clear.” One of our goals is to gain detailed insight into the synchronic workings of this drift in Spanish, by comparing two dialects that are known to be different with regard to PP-Preterit distribution, Mexican and Peninsular.

THE PRESENT PERFECT (PP) IN TWO SPANISH VARIETIES

Mexican varieties

At least since Lope Blanch (Reference Lope Blanch1972 [1961]), the standard analysis of the Mexican PP has been that it expresses durative aspect in describing situations initiated in the past that continue up to utterance time. Likewise, Moreno de Alba (Reference Moreno de Alba1978:57) pointed out that the difference between the PP and Preterit in Mexican Spanish is “esencialmente aspectual” (essentially aspectual), because the Preterit expresses perfective aspect whereas the PP overwhelmingly (90% [364/404]) refers to durative or repeated situations. Company (2002:62) distinguished between an “antepresente” (prepresent) value of the PP denoting an action that initiated and concluded in the past but is stipulated to be close to utterance time and a “pretérito abierto” (open preterit) value denoting an action initiated in the past whose effects, from the speaker's perspective, continue up to and possibly beyond utterance time (i.e., an unbounded, durative situation). This is a “pragmatic” use characteristic of Mexican varieties that contrasts with the purportedly “referential” use of the PP predominating in Peninsular Spanish.

Such analyses would place the Mexican PP at a developmental stage prior to the Peninsular PP. In Harris's (Reference Harris, Martin and Nigel1982) stages for Romance past tenses shown in Figure 2, the Mexican PP is situated at stage 2, which is characterized by the inclusive meaning of the perfect, in which situations commence in the past but are viewed as still ongoing at speech time. In terms of Dahl's uses and Comrie's types of perfects (Figure 1), the Mexican PP is a continuative perfect or a perfect of persistent situation.

Figure 2. Developmental stages of Romance PP and Preterit (cf. Schwenter, Reference Schwenter1994a:77, adapted from Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983; Harris, Reference Harris, Martin and Nigel1982).

This characterization of the opposition between the Mexican PP and Preterit appears to be corroborated by examples that make the continuing persistence of the past situation explicit. In (3a) with the PP, the doctor has attended to the person in question in the past and he continues to do so in the present; in (3b), the speaker self-corrects from the PP to the Preterit because, as he explains, the situation does not continue up to the present. (By contrast, in the Peninsular Spanish example (3c), there is an explicit indication [ahora ya nada ‘now nothing’] that the situation encoded in the PP does not persist in the present.)

(3)

a. Lo ha atendido, y lo sigue atendiendo (MexPop, 346)

‘He [the doctor] has treated (PP) him and he continues treating him’

b. en mi casa también yo lo he visto. Bueno, lo vi, porque también mi abuela ya murió hace unos seis años (MexCult, 366)

‘at my house I have seen (PP) it [the problem] also. Well, I saw (PRET) it, because my grandmother also died about six years ago’

c. Antes […] Ibas aquí, y cazabas […]

Hasta sacabas dinero vendiendo, sí. […]

Mucho conejo se ha vendido aquí.

Sí. Ahora ya nada. (CCON019A)

‘Before […] You went here, and hunted—

You even made money selling, yes. […]

A lot of rabbit was sold (PP) here.

Yes. Now there's nothing.’

Nevertheless, the Preterit may also appear in continuative contexts such as that seen in (3a) with an overt indication that a past situation continues to obtain in the present. In (4), this is explicitly indicated by the adverbial hasta la fecha ‘up until now,’ yet we have not a PP but a Preterit verb form.

(4) Pero ya vi que…que fui más o menos agarrándole a fondo, y le seguíhasta la fecha (MexPop, 230)

‘[Talking about playing the guitar] But I finally realized that … that I was more or less getting it right, and I have continued (PRET) up until now’

Likewise, both the PP and the Preterit may appear in perfect of result contexts, as in (5), where the present state of the speaker's son being fat (5a) and of the building being fully constructed (5b) are made explicit in the accompanying linguistic context (with estar ‘be [located]’ constructions).

(5)

a. ¡Está goldo, goldo, goldo! Ha salido muy sanito, fíjate (MexCult, 408)

‘[about her nine-month-old] He is fatty, fatty, fatty! He has turned out (PP) very healthy, you know’

b. ya levantaron un gran edificio. Ya está toda la estructura (MexCult, 428)

‘they put up (PRET) a big building. The whole structure is already up’

Both the PP and the Preterit are used in recent past contexts, as in (6), about sales on the same day as the speech event.

(6)

a. fíjese que… que vendí p's un poco bien (MexPop, 303)

‘well … I sold (PRET) a fair amount’

b. ahora tamién he vendido muy poco (MexPop, 303)

‘now also I sold (PP) very little’

There is, then, no one-to-one isomorphism (“one form for one meaning, and one meaning for one form” [Bolinger, Reference Bolinger1977:x]) between perfect meaning/function, such as “continuative” or “perfect of result,” and the form, PP or Preterit, that is chosen to express that meaning/function. This lack of isomorphism also extends to the Peninsular situation.

Peninsular varieties

The Peninsular Spanish PP is placed by most analysts at Harris's (Reference Harris, Martin and Nigel1982) developmental stage 3 (see Figure 2), which is characterized by the “current relevance” of the past situation (e.g., Alarcos Llorach, Reference Alarcos Llorach1947; Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983:196). The regional exceptions to this generalization are to be found in Northwestern Spain (e.g., Heap & Pato, Reference Heap and Pato2006), especially Galicia, Asturias and León, and also in the Canary Islands (e.g., Piñero Piñero, Reference Piñero Piñero2000; though see Serrano [Reference Serrano1995–96] for evidence that the use of the PP in Canarian Spanish has more recently been influenced by the Peninsular [Madrid] norm).

The static nature of the four historical stages in Figure 1, however, conceals the dynamic process of change in the development of the Peninsular Spanish PP. Diachronic data show that there has been an increase in the frequency of the PP relative to the Preterit, from 26% (314/1231) in 15th-century to 35% (506/1454) in 17th-century to 52% (540/1036) in 19th-century dramatic texts (Copple, Reference Copple2008). This increase in relative frequency has been accompanied by generalization into new contexts of use as the PP grammaticalizes.Footnote 2

In a fine-grained empirical study of synchronic PP usage in a Peninsular speech community, Schwenter (Reference Schwenter1994a) showed that the distribution of the PP and Preterit follows a strict hodiernal/prehodiernal (today/before today) distinction (cf. Dahl, Reference Dahl, Brian, Bernard and Östen1984), that is, the PP indicates past situations that occurred over the today of speech time. In (7), with a co-occurring today adverbial esta mañana ‘this morning,’ the speaker switches from Preterit to PP. Note that the PP here is pragmatically felicitous in Peninsular Spanish even if the speaker is speaking during the afternoon or the evening, that is, in a temporal period that is nonoverlapping with the one denoted by the adverbial (cf. García Fernández, Reference García Fernández, Ignacio and Violeta1999:3166–3169). Evidence that the PP has grammaticalized as a hodiernal perfective is that it occurs without adverbial specification in hodiernal contexts, indicating that the contextual meaning of a today-past event has been incorporated into the PP form itself (Schwenter, Reference Schwenter1994a:89).

(7) Lo escuchéesta mañana, lo he escuchadoesta mañana (CCON028A)

‘I heard (PRET) it this morning, I heard (PP) it this morning’

The hodiernal perfective has been proposed (Schwenter, Reference Schwenter1994a) as corresponding to an intermediate stage in the gradual process of aoristic drift (Squartini & Bertinetto, Reference Squartini, Bertinetto and Östen2000), albeit one that does not correspond to any of the four stages (Harris, Reference Harris, Martin and Nigel1982) in Figure 2. As noted by Dahl (Reference Dahl, Brian, Bernard and Östen1984:105), such a restriction to hodiernal contexts was also characteristic of the French PP (passé composé) in the 17th century. In the last developmental stage, that of, for example, modern-day French, temporal distance restrictions such as today vs. before today are lost completely, and the PP generalizes to cover all past perfective situations, regardless of their distance from utterance time. In (8), the PP (8b) refers to the same marriage as the Preterit (8a), perhaps with more of a presumed focus on the resulting state than on reporting the spatiotemporally located event; nevertheless, notice that the speakers use the PP for talking about buying the wedding present even after the temporal distance has been specified to September (8d–8e).

(8)

a. —Se casó allí Juan Carlos.

b. —¿Qué se ha casado ya Juan Carlos? No lo sabía, creo.

c. —Sí—. En septiembre. […] Todavía tengo su regalo en casa. No he vuelto a verlo.

d. —¡Ah!, ¿sí? ¿Qué le has regalado?

e. —No—le he comprado una—es que no sé cómo se llama. (BCON048A)

a. ‘—Juan Carlos got married (PRET) there.

b. —Juan Carlos got married (PP) already? I didn't know, I think.

c. —Yes. In September. […] I still have his present at home. I haven't seen him since.

d. —Oh, yeah? What did you give (PP) him?

e. —No, I bought (PP) him a—I don't know what you call it.’

The locus of variation in Spain thus appears rather different from that in Mexico: Peninsular speakers use both forms, PP and Preterit, in (prehodiernal) perfective contexts, whereas in Mexico, the forms seem to alternate in perfect contexts. However, an argument for current relevance is plausible in each case. In the pair of examples in (9), PP and Preterit co-occur with the same temporal adverb ayer ‘yesterday’ and the same verb type ‘(have) bought.’ In (9a), the interlocutors are talking about the new air conditioner producing hot air, a condition on the world or materially relevant, and in (9b), they are talking about the practice of price-gouging, a condition on the discourse, or discursively relevant, in Dahl and Hedin's (2000) terms. Similarly, in (8) above, the PP and Preterit ‘got married’ could likewise be interpreted as perfects of result and hence considered currently relevant: Juan Carlos, after all, is still married.

(9)

a. ayer he comprado un aire acondicionado y me da calor (BCON014B)

‘yesterday I bought (PP) an air conditioner and I'm getting heat [from it]’

b. Estas son prácticamente igual que las que compramosayer. La diferencia, mil, mil cuatrocientas pelas (CCON013C)

‘These are practically the same as the ones we bought (PRET) yesterday. The difference, a thousand, one thousand four hundred pelas [=pesetas]’

It seems, then, that we have before us a rather intractable empirical problem: determining which tokens are aspectually perfective—but not currently relevant—is unverifiable. In (8) and (9), we have no empirically motivated reason to consider the PP more currently relevant than the Preterit, except for the circular argument that the PP signals current relevance. Nor is it evident that the earlier Mexican examples in (6) about sales on the day in question are currently relevant perfects of recent past rather than hodiernal perfectives. Disconcerting though it may be for linguistic analysis, it is not the “best of all possible grammatical worlds,” because rather than symmetry and isomorphy—Preterit for perfective and PP for perfect functions—we have form-function asymmetry (Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983:188). A further complication for the ideal of form-function isomorphism is that besides perfective functions, as in (7)–(9), the Peninsular PP appears in canonical perfect of result contexts, as in (10), where mira ‘look’ indicates the visible result that Vanesa now wears braces.

(10) Mira, la han puesto a Vanesa aparato. (CCON018C)

‘Look, they have put (PP) braces on Vanesa.’

Thus, defining the locus of PP-Preterit variation as the perfect domain in the Mexican case and the perfective domain in the Peninsular case cannot be justified. We would like to get beyond the intuitive characterizations of the Peninsular and Mexican PP that abound in the literature, by examining not only the relative frequency of the alternating forms but also the conditioning of the variability, or the configuration of factors affecting speakers’ choices between forms (cf. Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2001:92). How, then, do we delimit the envelope of variation?

A GRAMMATICALIZATION PATH PERSPECTIVE ON CIRCUMSCRIBING THE VARIABLE CONTEXT

The availability of different forms to serve “similar or even identical functions” as newer layers emerge without replacing older ones is known in the grammaticalization literature as “layering” (Hopper, Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991:22–24). For example, in the English Past Tense, ablaut (snuck) represents an older layer and affixation (sneaked) represents a more recent layer of grammaticalized forms (Hopper, Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991:24); in the English future temporal reference domain, will is the older and be going to the newer grammaticalized form.

Variationists have long confronted inherent variation among different forms in a functional domain, that is, the fact that in a speech community there are “alternative ways of saying the same thing” (Labov, Reference Labov, Winfred and Yakov1982:22). The solution to the problem of form-function asymmetry in morphosyntax (verbal tense, aspect, mood) is the hypothesis that distinctions of grammatical function between different forms can be neutralized in discourse (D. Sankoff, Reference Sankoff and Newmeyer1988a). Although contexts can almost always be found in which different forms have different meanings, there are alternations in which the full accompaniment of meaning distinctions is not pertinent either for the speaker or the interlocutor; moreover, according to D. Sankoff, neutralization of distinctions in discourse is the “fundamental discursive mechanism of (nonphonological) variation and change” (D. Sankoff, Reference Sankoff and Newmeyer1988a:153–154). In a cognitive linguistics framework, a similar idea is Croft's (Reference Croftforthcoming) proposal that language change is possible because of “indeterminacy in verbalization.”

The interpretative component of the variationist method lies in determining the neutralization contexts and defining function (D. Sankoff, Reference Sankoff and Newmeyer1988a:154–155; cf. Labov, Reference Labov, Winfred and Yakov1982:25–26). In some cases, once a functional domain, such as future temporal reference, has been circumscribed, meaning differences within that domain can be operationalized and included as independent variables or conditioning factors (cf. Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán2001:136). For example, the hypothesis that degree of temporal proximity distinguishes go-based future expressions (e.g., English be going to) has been tested by coding for temporal distance (Poplack & Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999; Poplack & Malvar, Reference Poplack and Malvar2007). However, in the absence of co-occurring contextual elements in natural linguistic production, motivations in the choice of an expression such as current relevance are inaccessible to the analyst and their attribution to speakers may be an a posteriori artifact of theoretical bias (Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte1999:321–322; D. Sankoff, Reference Sankoff and Newmeyer1988a:154; cf. Van Herk, Reference Van Herk2002:124–125). Neither, furthermore, can the uses or types of perfect—experiential as opposed to continuative, perfect of result as opposed to recent past—be reliably distinguished beyond ideal examples in a large sample of tokens (cf. Howe, Reference Howe2006; Van Herk, Reference Van Herk2003; but see also Hernández, Reference Hernández2004; Winford, Reference Winford1993).

In grammaticalization, evolving constructions retain features of meaning from their source construction. This is known as the “retention” (Bybee & Pagliuca, Reference Bybee, Pagliuca, Ramat, Carruba and Bernini1987) or “persistence” (Hopper, Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991) hypothesis. In the evolution of linguistic resources, change is gradual, as properties, both semantic and grammatical, persist from the previous stage (Torres Cacoullos & Walker, Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walkerforthcoming). The use of the Peninsular PP as a hodiernal perfective (7) coexists with earlier perfect functions, such as perfect of result (10), which are retained and carried along, as the PP travels the perfect-to-perfective path (aoristic drift [Squartini & Bertinetto, 2000]).

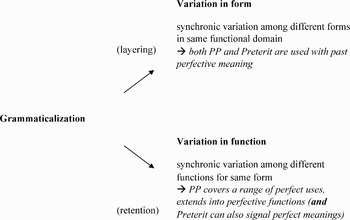

Herein lies the contribution of grammaticalization to the problem of semantic equivalence among tense-aspect-mood forms, part of the extensive literature on whether there can be linguistic variables beyond phonology (e.g., Cheshire, Reference Cheshire, Cornips and Corrigan2005; García, Reference García1985; Lavandera, Reference Lavandera1978; Milroy & Gordon, Reference Milroy and Gordon2003:169–190; Romaine, Reference Romaine1984; G. Sankoff, Reference Sankoff, Bailey and Roger1973; Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán2001:129–130; Winford, Reference Winford1993) (though grammaticalization is certainly not new to variationists; see G. Sankoff's Tok Pisin studies, e.g., G. Sankoff & Brown [Reference Sankoff and Brown1976]). Grammaticalization's retention hypothesis offers fresh insight into the polyvalence in linguistic form-function relationships: there is variation in function—a single form covers a range of meanings—as well as (the more familiar) variation in form—different forms serve the same grammatical function, as in Figure 3 (Torres Cacoullos, Reference Torres Cacoullos2001:459–463). Functional polyvalence makes the semantic equivalence issue moot for grammaticalizing variants. We cannot circumscribe the variable context by grammatical function narrowly, because a single form may cover a range of meanings along a grammaticalization path. Language universals are not so much synchronic grammatical categories such as future, progressive, perfect, but diachronic grammaticalization paths such as motion-verb purpose construction to future, locative to progressive to present, perfect to past, which are stronger cross-linguistic patterns (Bybee, Reference Bybee, Ricardo and Juana2006a).

Figure 3. The variable context for grammaticalizing variants encompassing stages along cross-linguistic grammaticalization paths: linguistic variable = perfect-to-perfective.

Thus, we propose that in the case of variants undergoing grammaticalization, the variable context needs to be circumscribed broadly, to include the stages, or array of meanings, traversed along the grammaticalization path. The Spanish PP covers grammatical territory bordering on resultatives, at one end, and perfectives, at the other. Cross-linguistically, the perfect is an “unstable” category. It tends to become something else, such as a perfective or general past tense (Lindstedt, Reference Lindstedt and Östen2000:366). The Preterit can be used for perfectlike functions, too. Rather than narrow the variable context to a particular grammatical function (meaning, use), such as perfect (of result, experiential, continuative) or perfective, the evolutionary perfect-to-perfective path constitutes the envelope of variation.

This grammaticalization path approach to the variable context is principled and independently motivated, given well-established cross-linguistic evolutionary paths (e.g., Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994; Heine & Kuteva, Reference Heine and Kuteva2002). However, its aptness depends on a study's objectives and must be determined empirically in each case. Our comparative study of dialects to track a change is best served by circumscribing the envelope of variation broadly for both the Mexican and Peninsular varieties. Moreover, it is important that, in these data, the Preterit covers the same uses as the PP (as in (3)–(9), for example), because delimiting the variable context—the context(s) in which a group of speakers has a choice between variant forms—is an empirical question (Labov, Reference Labov, Winfred and Yakov1982:30; cf. Milroy & Gordon, Reference Milroy and Gordon2003:180–183; Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2001:89–91). Note that we take the linguistic variable to be perfect-to-perfective and not perfect-to-past because in all Spanish dialects both the PP and the Preterit are in paradigmatic contrast with the Imperfect, which expresses imperfective aspect (situations viewed without regard to temporal boundaries) (cf. Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:83–85).Footnote 3

DATA

PP and Preterit tokens were exhaustively extracted from an approximately 100,000-word sample of the conversational portion of the COREC Peninsular Spanish corpus (Marcos Marín, Reference Marcos Marín1992) and from similar samples of the Habla culta and Habla popular Mexican Spanish corpora, which correspond to educated and popular speech, respectively (Lope Blanch, Reference Lope Blanch1971, 1976).Footnote 4 Given the relative paucity of references to same-day past situations in the Mexican sample, which consists of interviews rather than conversations, additional hodiernal tokens of both forms (N = 104) were located in the full corpus by searching in the vicinity of adverbials hoy ‘today’ and ahora ‘now’ as well as near otra voz ‘another voice’ and aparte ‘aside,’ which signal a break from the interview format. Some were found fortuitously in quoted speech (appearing between quotes in the transcriptions) or in reference to the immediate surroundings (¿ya me la acabé? ‘Did I finish it?’ [MexPop, 459]) or previous discourse (bueno, es que me dijo usted que ‘well, you told me that’ [MexCult, 74]).

Excluded from the analysis were 175 tokens. These were false starts (11a), interruptions (11b), and other cases of insufficient context (11c) for coding purposes (N = 119). Also set aside were Progressive estar ‘be (located)’ plus gerund forms such as han estado/estuvieron mirando ‘they have been/were watching’ (N = 33); morphologically ambiguous first person plural Preterit or Present forms, for example, en la Copa ustedes van bien. Nosot's apenas la empezamos ‘You're doing well in the Cup. We barely have started/are starting it’ (MexPop, 217) (N = 14); quoted material or metalinguistic comments, for example, ¿Ha pesado o pesa? Es lo mismo. ‘It has weighed or it weighs? It's the same.’ (BCON007B) (N = 4); and a residue of apparent transcription errors (N = 5).

These protocols yielded 1783 Peninsular and 2234 Mexican Spanish tokens. The frequency of the PP relative to the Preterit is 54% (956/1783) in the Peninsular and 15% (331/2234) in the Mexican data. The 15% PP rate is not higher in the Habla culta (162/1087) than in the Habla popular (169/1147) Mexican corpus, as we might expect if the PP is a prestige form (Squartini & Bertinetto, Reference Squartini, Bertinetto and Östen2000:413) (as may perhaps be the case in the Canary Islands, see Serrano [Reference Serrano1995–96]).

(11)

a. Y ahora ha estado—ha estado—o sea le puse esto así, el conector aquí (CCON005A)

‘And now it has been—has been (PP)—I mean I put this like this, the connector here’

b. —La verdad es que ya que te has roto el—

—Sí, ya me he roto el menisco no me voy a operar sólo … (CCON004D)

‘—The fact is that you broke (PRET) your—

—Yes, I have broken my meniscus I'm not going to get operated on only …’

c. No ahora no tiene—me acuerdo estoy allí en—cogí el este—yo le mando la tarjeta, como se manda generalmente vía asociación… (CCON007D)

‘No now it doesn't have—I remember I'm there at—I took (PRET) this thing—I send the card, since it's usually sent by the association…’

HYPOTHESES AND CODING OF TOKENS

Aktionsart verb class

We coded tokens for the four Vendlerian (Vendler, Reference Vendler and Vendler1967) lexical classes of predicate, according to the oppositions stative vs. dynamic, telic vs. atelic, punctual vs. durative. Dynamic predicates involve change or movement, whereas statives do not; telic situations have inherent end points; and punctual situations have no duration (Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:41–51). Stativity distinguishes states; telicity discriminates between accomplishments and achievements as opposed to activities and states; and punctuality further characterizes achievements. The classification is not straightforward, however, because Aktionsart categories are not cut up the same way in different languages (Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:28) nor are they completely independent of morphological aspect. For example, telic predicates with imperfective morphology are said to be “detelicized,” such that escribía su tesis ‘she was writing her thesis’ is “lexically telic but contextually atelic” (Bertinetto & Delfitto, Reference Bertinetto, Delfitto and Östen2000:193).

We coded for Aktionsart independently of aspect by considering the lexical type in the Infinitive (citation) form. The only contextual element we took into account was the presence of objects to code for telicity. For example, comimos en frente (MexCult, 188) ‘we ate in front’ is an activity (atelic), but nos comieron el saco (CCON019A) ‘they ate our sack’ is an accomplishment (telic). We further distinguished between verb-object compounds, such as hacer ejercicios ‘do exercises’ (activity) in (12) and referential objects (tracking Noun Phrases), as in hacer un mantel ‘make a tablecloth’ (accomplishment) in (13) (cf. Thompson & Hopper, Reference Thompson, Hopper, Joan and Paul2001). We assigned most verb types uniformly to one class, but for some frequent verbs, we distinguished different meanings. For example, conocer ‘meet’ a person is an achievement (conocí a varias muchachas [MexPop, 254] ‘I met various girls’), but conocer ‘experience’ a place is an activity (ha conocido […] diferentes lados [MexPop, 255] ‘she has come to know […] various places’). Undoubtedly our classification is not definitive; however, as our objective is the comparison of two dialects, what is most important is that the classification schema be applied consistently (cf. Walker, Reference Walker2001:17–19). We achieved this by combining the data from all the corpora and then coding by verb (lexical) type.

(12) Activity (verb-object compound):

respiré, hice ejercicios y… recibí determinadas instrucciones (MexCult, 382)

‘I breathed, I did exercises (PRET), and … I was given certain instructions’

(13) Accomplishment (tracking NP object):

Te voy a enseñar un—un—un mantel que le he hecho (BCON014A)

‘I'm going to show you a tablecloth that I made (PP) for her’

Because perfect grammaticalization involves extension of the original resultative construction to more classes of verbs (e.g., Dahl & Hedin, Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:393), we hypothesize that if the PP in Spain is at a more advanced grammaticalization stage, it will be subject to fewer Aktionsart restrictions than in Mexico. In particular, achievements, as in (14), should disfavor the PP more strongly in the Mexican than in the Peninsular data.Footnote 5 Punctual predicates have been claimed to be “grammatical” only in iterative contexts such as Juan ha llegadotarde en los últimos días ‘Juan has arrived (PP) late the last few days’ (as opposed to *Juan ha llegadoahora ‘Juan has arrived [PP] now’) in Harris's (Reference Harris, Martin and Nigel1982) developmental stage 2 (continuative perfect) (Squartini & Bertinettto, Reference Squartini, Bertinetto and Östen2000:408, 410).

(14) Achievement (punctual)

a. cuando llegué aquí … ps él estaba trabajando (MexPop, 332)

‘when I arrived (PRET) here… he was working’

b. cuando he llegado de la peluquería, tenía que subir a llamarle (BCON014B)

‘when I arrived (PP) from the hairdresser, I had to go upstairs to call him’

Temporal adverbials

Likewise, if the Mexican PP is a continuative perfect, then “current temporal frame” adverbials referring to periods that extend up to the moment of speech (Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:137) should favor choice of the PP over the Preterit. Such proximate adverbials are ahora ‘now,’ últimamente ‘lately,’ and expressions with proximate demonstratives, for example, esta semana ‘this week,’ este mes ‘this month’ (15). Frequency adverbials, for example, a veces, en ocasiones ‘sometimes,’ cada año ‘each year,’ __ veces ‘__ (number) times’ (16), including siempre ‘always’ and nunca ‘never’ (17) (e.g., García Fernández, Reference García Fernández, Ignacio and Violeta1999:3136; Smith, Reference Smith1991:159) are consonant with both experiential meaning and iterative situations persisting into the present and so should also favor the PP.

(15)

a. Muy nervioso el chiquillo. Ahora se ha calmado bastante. Ya lo ve usted. (MexPop, 346)

‘Very nervous the little one. Now he has calmed down (PP) quite a bit as you can see.’

b. Ya me di cuentahace poco que— (CCON019A)

‘I realized (PRET) recently that—’

(16)

a. Aunque he pasadomil veces por ahí; pero ya ni me he fijado. (MexCult, 428)

‘Even though I have passed (PP) a thousand times by there; but I haven't even noticed.’

b. Yo varias veces subí caminando también por ahí. (MexCult, 436)

‘I several times have gone up (PRET) walking also through there.’

(17)

a. Siempre, toda la vida, ella ha trabajado. (MexPop, 266)

‘Always, all her life, she has worked (PP).’

b. Pero es que es imposible, si nadie me filmó en vídeo, nunca. (BCON043B)

‘But it's impossible, nobody has filmed (PRET) me on video, never.’

In contrast, specific or “definite time” (Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:137) adverbials, such as ayer ‘yesterday,’ calendar dates, clock times, co-occurring cuando ‘when,’ and other temporal clauses (18), should disfavor the PP, as should ‘connective’ adverbials (cf. Bonami et al., Reference Bonami, Godard, Kampers-Manhe, Francis and Henriette de2004; García Fernández, Reference García Fernández, Ignacio and Violeta1999:3188–3192) such as primero ‘first,’ antes ‘before,’ después, entonces, luego ‘afterward, then,’ al final ‘in the end’ (19), because temporal specification or anchoring to another situation presumably detracts from (focusing on the result associated with) a current relevance interpretation (Dahl & Hedin, Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:395; cf. Fleischman, Reference Fleischman1983:199).

(18)

a. porque eso pasóel año pasado (MexCult, 179)

‘because this happened (PRET) last year’

b. Liebres sí se ven algunas. Y zorras- y zorras muchas. Y jabalíes el año pasado han matado uno o dos. (CCON019A)

‘Hares you see some. And foxes—lots of foxes. And wild boars last year they killed (PP) one or two.’

(19)

a. Después nosotros nos jalamos de media cancha para la portería de nosotros; el otro equipo se quedó con el árbitro […] Total, de que al último nos lo anuló. (MexPop, 217)

‘Then we went (PRET) from midfield toward our goal; the other team stayed (PRET) with the referee. […] In the end he cancelled (PRET) it [the goal].’

b. O sea ha esperado a acabar de hablar con Nicolás, lo que había empezado, ha tardado su minuto y luego ya ha cogido la llamada. (CCON016A)

‘I mean he waited (PP) to finish talking with Nicolás what he had started, he took (PP) his minute and then he finally answered (PP) the call.’

In the data, most frequent were specific (N = 27 PP/263 total), connective (N = 21/175), proximate (N = 81/114), and frequency adverbials (including siempre ‘always,’ nunca ‘never’) (N = 79/138). Other cases were duratives such as durante los cinco primeros años ‘during the first five years,’ mucho tiempo ‘for a long time,’ una semana ‘for a week’ (N = 18/73), desde ‘since,’ and hasta ‘until’ adverbials (cf. Bertinetto & Delfitto, Reference Bertinetto, Delfitto and Östen2000:206) (N = 5/46), and occurrence of the token in a cuando clause (13/101). The great majority of tokens, approximately 75% in both the Peninsular and Mexican samples, occur without any co-occurring temporal expression. The co-occurrence of adverbial ya ‘already, finally, now’ was coded in a separate factor group, because ya combines with other temporals, for example, después ya ‘then,’ hoy ya ‘today.’

Noun number

Akin to frequency adverbials is noun plurality, which “reflects multiple instances of the event type” (Langacker, Reference Langacker and Adele1996:301; see also Greenberg [Reference Greenberg and Alan1991] on the relationship between noun number and verb aspect). Plural objects (20) are more congruent with experiential as well as continuative (perfect of persistent situation) uses than singular objects and so should favor the PP.

(20)

a. bueno, yo ya he comprado ya por ahí cadenas de ésas (BCON015B)

‘well, I already have bought (PP) by there chains of that kind’

b. se empezó con el año Beethoven. […] Y ya tocaronvarias sinfonías y varias cosas de él, ves. (MexCult, 422)

‘they started with the Beethoven year. […] And they already have played (PRET) various symphonies and various pieces of his.’

Clause type

If the function of perfects in narratives is to present background information that is relevant to a situation at a given point (Givón, Reference Givón and Paul1982), we expect the PP to be generally favored in relative clauses (21), which encode background information (cf. Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006:130; Hopper & Thompson, Reference Hopper and Thompson1980; but see Fox & Thompson, Reference Fox and Thompson1990:306). In addition, experientials state that a situation “is instantiated during a period of time, rather than introducing an event as a new discourse referent” and this perfect interpretation occurs particularly often in nonassertive contexts, that is, with questions and negated statements (Dahl & Hedin, Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:388; cf. Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:143). Hence, we singled out interrogatives, hypothesizing that yes-no questions in particular (22), which are less anchored temporally than WH (who, what, when, where, why) questions, should favor the PP (cf. Schwenter, Reference Schwenter1994a:89–90). Polarity was coded in a separate factor group (but ultimately not included in the multivariate analysis, see below).

(21)

a. ¿Quiere otra pasta, madre? Este es el vino de Oporto que han traído ellos. (CCON019A)

‘Do you want another pastry, mother? This is the Port wine that they brought (PP).’

b. Yo sólo he visto uno que me salió ahí un día. (CCON019A)

‘I've only seen one that appeared (PRET) there one day.’

(22)

a. ¿Ah, sí? ¿Le ha tocado? (MexPop, 297)

‘Yes? It has happened (PP) to you?’

b. No tiene nada de malo. ¿O sí? ¿Escucharon algo malo? (MexPop, 330)

‘There's nothing wrong with that. Or is there? Did you all hear (PRET) anything bad?’

Temporal reference

If the Peninsular PP has a hodiernal perfective function, then temporal distance should constrain PP-Preterit variation. We distinguished today (hodiernal), yesterday (hesternal), and before yesterday (prehesternal) past situations, as in (23).

(23)

a. Hodiernal (today):

¿Has visto esta mañana el atasco Extremadura (CCON028A)

‘Did you see (PP) this morning the traffic jam [on] Extremadura?’

b. Hesternal (yesterday):

y ayer fuimos Maripi y yo (BCON014B)

‘and yesterday we went (PRET) Maripi and I’

c. Prehesternal (before yesterday):

Ése tendrá unos veinte años, lo compró José (BCON014B)

‘That one must be twenty years old, José bought (PRET) it’

In the three cases in (23), the situations are temporally anchored to past time reference points located with respect to utterance time. We made two further distinctions in this factor group, which we call temporal reference rather than temporal distance precisely because of these two further types. First, there are past situations for which temporal location is irrelevant, which cannot be queried by ¿cuándo? ‘when,’ as in (24)—never matured, frequently invited, often tempted to slap. Irrelevant temporal reference corresponds in many cases to what might be considered perfect (relational link-to-present) uses, but there are perfectivelike cases, such as (24b), where the speaker invited an acquaintance to a meal several times during this person's visit to Mexico. These irrelevant temporal reference contexts turned out to be largely negative polarity (59% [216/368]) (24a), frequency adverbial (22% [82/368]) (24b), and yes-no interrogative (11% [42/368]) contexts (three factors that may potentially co-occur), though close to a third of all irrelevant temporal reference tokens are none of the above (111/368) (24c), in the Peninsular and Mexican data combined.Footnote 6

(24) Irrelevant temporal reference (cannot ask ‘when?’):

a. Hay gente que se muere con noventa años y nunca ha madurado (BCON014D)

‘There are people who die at ninety years old and they never have matured (PP)’

b. lo invitamos a comer muchas veces (MexCult, 184)

[during an acquaintance's visit to Mexico] ‘we invited (PRET) him to eat many times’

c. me da unas contestaciones, que se me ha quedado en la mano la cachetada. (MexCult, 407)

‘she gives me some retorts, that the slap (barely) has remained (PP) in my hand.’

Second, there are past situations whose temporal reference is indeterminate, for which the analyst and possibly the interlocutor cannot resolve the temporal distance of the past situation with respect to utterance time, as in (25). Unlike irrelevant temporal location as in (24) above, one can ask the speaker ¿cuándo? ‘when?’ of what we call indeterminate temporal reference situations to resolve that reference. Indeterminate temporal reference is not particularly skewed with respect to polarity (5% [72/1514] negative), temporal adverbials (1% [18/1514] frequency), or clause type (5% [82/1514] yes-no questions, 5% [72/1514] WH questions).Footnote 7

(25) Indeterminate temporal reference (analyst, possibly interlocutor, cannot resolve temporal distance)

y ahora le he comprado a mi nieto uno. (CCON004C)

‘and now I (have) bought (PP) one for my grandson.’

The proportion of irrelevant temporal reference contexts is virtually identical in the Mexican and Peninsular data, at about 10%. Likewise, hesternal—a scarce 2% of the tokens—and prehesternal occurrences combined add up to about 40% in both data sets. Hodiernal contexts make up 6% and 16%, and in a complementary fashion, indeterminate temporal reference makes up 42% and 32%, in the Mexican and Peninsular data, respectively (Tables 1 and 2), a difference which is at least in part attributable to genre differences (interviews vs. conversations) in the corpora analyzed.

Table 1. Factors contributing to choice of PP over Preterit in Mexican Spanish (nonsignificant factor groups within brackets)

Not selected as significant: Co-occurring ya.

Table 2. Factors contributing to choice of PP over Preterit in Peninsular Spanish (nonsignificant factor groups within brackets)

Not selected as significant: clause type, Aktionsart.

Polarity and subject/object factor groups

Negation is said to atelicize, yielding a continuative (perfect of persistent situation) meaning (e.g., Squartini & Bertinetto, Reference Squartini, Bertinetto and Östen2000:412); therefore, a reasonable hypothesis is that negative polarity should favor the PP, particularly in the Mexican data. Nevertheless, cross-tabulations in both data sets showed that irrelevant temporal distance favors the PP across polarity contexts, while negative polarity favors the PP only in hodiernal contexts in the Mexican data (36% [8/22]). Thus, the appearance of a favoring effect of negation in other studies (e.g., Hernández, Reference Hernández2004; Howe, Reference Howe2006) may well be due to the high proportion of negative polarity in irrelevant temporal reference contexts (in the present data, 50% [216/435], whereas only 4% [152/3578] of affirmative polarity tokens occur in irrelevant temporal reference contexts).Footnote 8

Grammatical person and subject relationship to speaker were coded to investigate the role of subjectivity in speakers’ choice of the PP (cf. Carey, Reference Carey, Dieter and Susan1995; Company, 2002:63). If the PP is more subjective than the Preterit, expressing meanings based in the speaker's internal belief or attitude, then we might expect a higher PP rate in first person contexts. First person singular displays approximately the average PP rate for each dialect (16% [105/674] Mexican, 49% [301/609] Peninsular). In the Mexican data, third person subjects close to the speaker such as family members, about whom speakers are presumably more likely to express their point of view, do not show a higher PP rate (11% [26/237]) than distant referents such as casual acquaintances, those not personally known, or nonspecific subjects (16% [67/418]), as might be expected if the PP constitutes an expression of subjectivity. The highest PP rate is with second person singular subjects and object pronoun clitics (te, le) (26% [49/187] in the Mexican and 81% [116/144] in the Peninsular data); however, second singular largely occurs in questions (62% [116/187] in the Mexican [interview], 45% [64/142] in the Peninsular [conversational] data) and disproportionately in hodiernal contexts (20% [37/187] Mexican, 32% [46/144] Peninsular).Footnote 9

Neither polarity nor subject factors were included in the multivariate analyses presented in the following section. Other factor groups, marginal results for which will be presented below, were object presence and object form (pronominal vs. lexical, definite vs. indefinite) and previous verb form.

COMPARISON OF LINGUISTIC CONSTRAINTS

Tables 1 and 2 show two independent variable-rule analyses (Paolillo, Reference Paolillo2002; D. Sankoff, Reference Sankoff, Ammon, Dittmar and Mattheier1988b) of contextual factors contributing to the choice of the PP in the Mexican and Peninsular data, respectively, using the Windows application GoldVarb X (D. Sankoff et al., Reference Sankoff, Tagliamonte and Smith2005).

Most striking about the Mexican results in Table 1 is the corrected mean of .06 indicating the low overall tendency of occurrence of the PP and the selection as significant (p = .019) of five out of the six factor groups considered. As expected, the PP is favored only in restricted contexts in Mexico. The temporal adverbial factor group has the second highest magnitude of effect (range = 35),Footnote 10 with co-occurring proximate (e.g., ahora ‘now’) and frequency (e.g., muchas veces ‘many times’) adverbials favoring the PP. Plural number favors the choice of the PP (.66), but singular objects do not (.45). Marginal results for separately coded transitivity and definiteness factor groups confirm that it is not the presence of any object that favors the PP, because the PP rate in intransitive predicates, including object-verb compounds such as hacer ejercicios (see (13)), is at the average of 14% (174/1228).Footnote 11 Nor is the plural effect independent of the form of the object (pronominal, definite lexical, indefinite lexical). Rather, plural indefinite full noun phrase (NP) objects show the highest PP rate at 32% (11/34). We interpret this as evidence for experiential use of the Mexican PP, because these NP types tend to denote referents that correspond to multiple verbal situations, as in (26), where what is denoted are instances of listening to different songs.Footnote 12

(26) yo te he oídocanciones tuyas […] muy bonitas, y que por desidia no quieres registrarlas. (MexPop, 238)

‘I have heard (PP) songs of yours […] very pretty ones, that out of laziness you don't want to copyright them.’

Yes-no questions (40/134) and relative clauses (37/174) are favorable to the PP, as predicted. Marginal results indicate that the PP rate is considerably below average (3% [4/117]) in temporal clauses (27), just about average (13% [12/94]) in WH questions (qué ‘what,’ dónde ‘where,’ quién ‘who’) (28), and somewhat higher than average (19% [20/104]) in causal porque ‘because,’ es que ‘it's that,’ como ‘as, since’ clauses (29), which may be taken as harmonic with the “explanatory” sense of perfects (Dahl & Hedin, Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:39; cf. Inoue, Reference Inoue1979; Li et al., Reference Li, Thompson, Thompson and Paul1982).

(27) Y cuando le dije: “Si vale doscientas”, dice: (MexCult, 179)

‘And when I told (PRET) her: ‘It costs two hundred,’ she says:’

(28) Y ¿qué le pasó al muchacho? ¿Por qué está así? (MexPop, 344)

‘What happened (PRET) to the child? Why is he like that?’

(29) A mí no m'engaña nadien, porque yo he visto muchas cos's. (MexPop, 304)

‘Nobody can fool me, because I have seen (PP) many things.’

Furthermore, the Mexican PP is subject to Aktionsart restrictions. It is disfavored by achievement (punctual) predicates (.39), a result consistent with a continuative perfect. Pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference between accomplishments (15% [83/547]) and activities (20% [114/571]) or states (16% [91/567]) (cf. Squartini & Bertinettto, Reference Squartini, Bertinetto and Östen2000:408), nor did the subclass of process (change-of-state) verbs, including verbs of becoming hacerse, ponerse, quedarse plus adjective, which have been associated with resultatives and the perfect of result (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:55, 69; Dahl & Hedin, Reference Dahl, Hedin and Östen2000:390; Hernández, Reference Hernández2004), show a higher than average PP rate (15% [16/108]). The single-most frequent verb type, decir, which makes up about 10% of the data, has a low PP rate of 7% (16/217).

The factor group with the greatest magnitude of effect by far is temporal reference, with a range of 77. Marginal results showed no PP occurrences either in yesterday (hesternal) or before yesterday (prehesternal) contexts, but today (hodiernal) contexts had a below average 10% PP rate. The higher PP rate in today than before today situations is consonant with a current relevance meaning, which should tend to be pragmatically more felicitous the closer to speech time.Footnote 13 These contexts combined make up the specific temporal reference factor, which is the most highly unfavorable (.17) for the PP. Thus, stronger than a temporal distance effect is a temporal reference effect: both today and before today (i.e., specific, past) contexts disfavor the PP, which is most strongly favored when temporal distance is irrelevant (.94), as expected for a perfect. The PP is also favored (.76) in indeterminate temporal reference contexts, in which temporal anchoring, though not necessarily irrelevant, is left unspecified by the interlocutors.Footnote 14

In Peninsular Spanish (Table 2), the corrected mean is .61 with the relative frequency reversed, the PP constituting 54% of the data. Yet despite the rate difference, some of the same constraints hold as in Mexican Spanish. The adverbial and number factor groups are ordered second and third, respectively, as in Mexican Spanish, and show the same direction of effect. The selection of these two factor groups as significant (p = .036) is evidence that the Peninsular PP retains prior perfect functions. Retention (persistence) of earlier meaning features, which is expected in grammaticalization (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:16; Hopper, Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991), is manifested in distribution and co-occurrence constraints (Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte1999; Torres Cacoullos, Reference Torres Cacoullos1999:29–34).

However, other constraints are not operative. There are no Aktionsart restrictions, as the PP rate is virtually identical for achievements (53% [166/316]), accomplishments (55% [311/562]), activities (59% [240/405]), and states (51% [147/289]) (none of these differences achieve significance at the .01 level in chi-square tests). We note that decir, the single-most frequent lexical type comprising 10% of the data, has a relatively low PP rate of 43% (79/182), though not as disproportionately low as in the Mexican data.Footnote 15 Neither is clause type significant: although pairwise (chi-square) comparisons show that the difference between yes-no questions (56/78) and all other clause types combined (776/1485) is significant (p = .0007), the PP rate is the same for WH questions, at 73% (47/64) (30); furthermore, relatives do not have a higher PP rate (see note 19). The loss of clause type and Aktionsart effects indicates generalization of meaning.

(30) Y ¿qué le ha pasado a su marido? ¿un accidente? (CCON018C)

‘And what happened (PP) to her husband? An accident?’

Clear evidence for the PP's advance along the perfect-to-perfective grammaticalization path appears in the temporal reference factor group, which has the greatest magnitude of effect (range = 81), as in the Mexican data (Table 1). Additionally, as in the Mexican data, irrelevant temporal reference contexts are highly favorable to the PP (.94) in the Peninsular data, consonant with retention of perfect functions. However, unlike the former, in the Peninsular data there is a true temporal distance effect, with today (hodiernal) contexts strongly favoring the PP (.93), and before today contexts strongly disfavoring (.13). The near-categorical PP in today contexts (96%), even in the presence of specific clock-time adverbials as in (31), confirms the hodiernal perfective function of the PP in Spain previously noted by Schwenter (Reference Schwenter1994a). In fact, with a co-occurring specific or connective adverbial, the PP rate is not significantly lower than in other hodiernal contexts (87% [13/15] vs. 96% [261/272], chi-square = 2.836653, p = .0921). This near-obligatoriness means precisely that the PP is grammaticalized as a hodiernal perfective, with no necessary pragmatic inferences of current relevance.

(31) le he dicho ahora, a las cinco de la tarde, que le [he] vuelto a llamar o a las cinco y media, ya te digo cuando he llegado de la peluquería (BCON014B)

‘I told (PP) him now, at five p.m., I called (PP) him again or at five-thirty, I tell you when I arrived (PP) from the hairdresser’

Marginal results showed no difference in PP rate between yesterday (hesternal) contexts (10% [4/42]) and the much more numerous before yesterday (prehesternal) contexts (17% [123/738]), as would be predicted by the hypothesis that the PP gradually pushes further back in temporal distance as it follows the presumed route to general past perfective via increasing remoteness distinctions. Nor is the PP rate greater the closer to speech time: situations that we could reliably determine as having occurred within a year from speech time, as indicated by co-occurring adverbial el otro día ‘the other day,’ had virtually the same PP rate, with 8% (3/40), as those occurring during el año pasado ‘last year’ or before, with 11% (4/36). Still, the PP does occur in the Peninsular data at a low but non-negligible rate (16%) in these before today contexts, as in (32)—(32a) ‘yesterday,’ (32b) ‘as a kid,’ (32c) ‘one hundred years ago.’Footnote 16

(32)

a. Estas son prácticamente igual que las que compramosayer. La diferencia, mil, mil cuatrocientas pelas. […] Las que hemos comprado allí son Mora y el dibujo es más bonito (CCON013C)

‘These are practically the same as the ones we bought (PRET) yesterday. The difference, a thousand, one thousand four hundred pelas [=pesetas] […] The ones we bought (PP) there are Mora brand and the design is prettier’

b. ¿cuántos cachetes me han dado a mí de chaval porque siempre con una navajita en la mano (CCON022D)

‘how many slaps was I given (PP) as a kid because always [I was] with a knife in my hand’

c. esto fue una zona—hace cien años ha cambiado el panorama y ahora las gentes apoderadas […] se van a—a la Torre Picasso (CCON004C)

‘this was an area—one hundred years ago the panorama changed (PP) and now the high and mighty […] go to the Torre Picasso’

The PP is used in narrative to express discrete and sequential foregrounded past events comprising the main story line, which is the typical cross-linguistic (past) perfective function (cf. Schwenter, Reference Schwenter1994a:95). In the narrative in (33), the PP co-occurs with connective adverbials a la media hora ‘a half-hour later’ and luego ‘then.’

(33) Hemos venido dos disfrazados con un mono, hemos extendido una escalera y los—hemos extendido la escalera y han subido tres arriba. Han desplegado una pancarta y a la media hora o por ahí pues han llegado los guardias jurados y la guardia civil y los ha sacado a—a palos prácticamente. Vamos que oíamos los gritos desde aquí y les han atizado bastante. Luego nos han tenido aquí un tiempo sin saber a dónde les iban a llevar, hemos estado gritando “insumisión,” “libertad,” “insumisos presos abajo” y ahora por lo visto se les han llevado a la comisaría … (CCON013F)

‘We came (PP) dressed in overalls, we extended (PP) a ladder and them—we extended (PP) the ladder and three went up (PP). They unfurled (PP) a sign and a half-hour later or around there well the security guards and the Civil Guard arrived (PP) and they removed (PP) them—practically hitting them. We heard the yelling from here and they roused (PP) them quite a bit. Then they had (PP) us here a while without knowing where they were going to take them, we were shouting ‘insubmission,’ ‘liberty,’ ‘insurgent prisoners down below’ and now it seems that they have taken (PP) them to the police station …’

Further evidence for the generalization of the PP into perfective contexts comes from the form of the preceding verb. The pattern is the same in both the Peninsular and Mexican data. The PP rate is higher than average with a preceding PP and lower with a preceding Preterit form. This result may be interpreted either as a mere reflection of preferred temporal reference contexts or as a priming effect (e.g., Szmrecsanyi, Reference Szmrecsanyi2006), a hypothesis that we do not pursue further in this article. Important for our purposes is that whereas in Mexico the rate of the PP with a preceding Imperfect (past imperfective) is a scant 3% (4/127), which is only one-fifth of the overall PP rate (15%), in the Peninsular data the rate of the PP with a preceding Imperfect is 27% (20/75), which is fully one-half of the PP average (54%). This disproportionately greater co-occurrence is an indication that in Peninsular Spanish the PP and the Imperfect are in paradigmatic contrast as markers of foreground/background, as in (34).

(34)

a. Sólo había dos y me ha pedido uno Jose (CCON022E)

‘There were only two and Jose asked (PP) me for one’

b. Estaba del revés, tú le has dado la vuelta al chocarte (CCON018B)

‘It was facing the wrong way, you turned it (PP) around when you crashed [into it]’

c. Vamos que oíamos los gritos desde aquí y les han atizado bastante. (CCON013F)

‘We could hear the yelling from here and they roused (PP) them quite a bit.’

The two data sets also differ with respect to a preceding Present (excluding cases of narrative [“historical”] Present). Whereas the PP rate following a Present is 1.2 times greater than the overall average in the Peninsular data, at 65% (88/135), in the Mexican data, at 42% (73/176), it is 2.8 times greater than the corresponding average. The relatively greater rate of PP with a preceding Present form seems consonant with the continuative perfect use of the PP in Mexico.

Finally, we interpret the significant favoring effect of the adverb ya ‘already, finally, now’ in the Peninsular data (.65) as an indication that the PP is becoming the default past perfective expression in this dialect. The adverb ya by itself does not specify a past reference time, but it does indicate that the past situation occurred at some unspecified point before utterance time (cf. Koike, Reference Koike1996:273). With respect to Aktionsart classes, ya in both corpora co-occurs more often with telic predicates: accomplishments (37% [33/89] Peninsular, 37% [63/172] Mexican) and achievements (27% [24/89] Peninsular, 20% [34/172] Mexican). However, the two dialects diverge with respect to ya co-occurrence with the PP. In the Peninsular data, the PP rate is greater for telic predicates (accomplishments and achievements) co-occurring with ya than for those not co-occurring with ya (77% [44/57] vs. 53% [431/813], chi-square = 12.56281221, p = .0004) (35), but in the Mexican data a co-occurring ya does not increase the rate of the PP for any Aktionsart class.

A similar contrast between the two dialects is revealed when examining the interaction of ya with temporal reference. In both data sets, ya appears disproportionately in hodiernal contexts (29% [26/91] Peninsular, 17% [30/175] Mexican).Footnote 17 In the Peninsular data, ya increases the rate of the PP in both hodiernal and prehodiernal contexts. In hodiernal contexts, some variation between the PP and the Preterit remains when ya is not present (95% [248/261] PP), but when ya is present only the PP is found (26/26 PP) (36a). In prehodiernal contexts, there is an even greater disparity between contexts with and without ya, as the PP occurs 43% (10/23) with ya, but only 16% (117/752) in its absence (chi-square = 12.6967249, p = .0004). The Mexican data show a converse effect. In hodiernal contexts, some variation between PP and Preterit is found when ya is not present (13% [14/108] PP), but a co-occurring ya leads to a complete lack of variation in favor of the Preterit (30/30 Preterit) (chi-square = 4.327956989, p = .0375) (cf. García Fernández, Reference García Fernández, Ignacio and Violeta1999:3156; Lope Blanch, Reference Lope Blanch1972) (36b). In sum, the favoring effect of ya in many contexts in the Peninsular data is good evidence that the PP in this dialect is becoming the default past perfective form. In contrast, in the Mexican data, ya co-occurrence was not selected as significant when considered with the other factor groups and the direction of effect, if any, is reversed, because the overall PP rate is lower (10%) with ya than without (15%) (Table 1, note 17).

(35)

a. cuando ya me he dado cuenta ha sido cuando ya está terminado. (CCON022D)

‘when I finally realized (PP) was when it's already finished.’

b. el otro día, en el desfile […] Pero te diste cuenta que llevaban las medias (CCON003A)

‘the other day in the [fashion] parade […] But you realized (PRET) that they were wearing stockings’

(36)

a. y me fui corriendo, corriendo a la caza de Diego al—allí en Alicante. Y ya le he dicho (BCON022B)

‘and I went running, running in the hunt for Diego, there in Alicante. And I already told (PP) you’

b. Se empató también. Nos fuimos a pénaltis. Ya te dije, ¿no? (MexPop, 215)

‘It was still tied. We went to penalty kicks. I already told (PRET) you, right?’

WHAT A PAST PERFECTIVE DEFAULT LOOKS LIKE AND HOW A ‘PERFECT’ GETS TO BE ONE

Emerging from the variable-rule analyses are the similar linguistic constraints as measured by the constraint hierarchies, or the ordering of factor weights within each factor group, holding across the two dialects. Parallel constraint hierarchies show that “the variant under study does the same grammatical work in each” comparison variety (Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2001:93). Nevertheless, they obscure enormous frequency differences in PP use, as reflected in the disparate corrected means: .61 in the Peninsular as opposed to .06 in the Mexican data. To take one obvious example, in both dialects, the PP is favored in contexts of indeterminate temporal reference, with factor weights of .65 (Peninsular) and .76 (Mexican); however, this favoring effect is manifested very differently in usage. The PP occurs 73% in such contexts in the Peninsular data, yet only 20% in the Mexican.

To compare the probability that the PP will occur in a given context while controlling for its frequency of occurrence in that context, we reanalyzed the data according to the combined effect of the corrected mean and factor weight (cf. Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack, Tagliamonte, Philip and Anand1996).Footnote 18 These results, shown in Table 3, allow comparison of factor probabilities across independent runs (Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack, Tagliamonte, Philip and Anand1996:84).

Table 3. Combined effect of corrected mean plus factor weight in Mexican and Peninsular Spanish (nonsignificant factor groups within brackets)

In the Mexican data, the combined input and weight for the PP does not exceed .12 even in the most favorable contexts—proximate and frequency adverbials, plural NPs, yes-no interrogatives, and relative clauses—except for indeterminate temporal reference contexts, where it inches up to .17, and the one context of substantial PP occurrence, irrelevant temporal reference, where it approximates .50. In contrast, in the Peninsular data, the combined input and weight is well above .50 for all factors, except in the presence of a temporal expression other than a proximate or frequency adverbial, where it is .44. The clear exception to this pattern is prehodiernal temporal reference contexts, at .19, which remain the preferred context for the Preterit in Peninsular Spanish.

Figure 4 summarizes the results, comparing the two dialects. For each factor group we indicate whether it is significant in the separate multivariate analysis for each dialect, whether the direction of effect is the same or different, and which form, the Preterit or the PP, is the majority variant in the most frequent or least specified context.

Figure 4. Constraints and rates (relative frequency) in Mexican and Peninsular Spanish.

Two sets of findings emerge from Figure 4. First, in comparing significance and direction of effect, we see that the two dialects have shared linguistic conditioning with respect to some factor groups, but diverge and even contrast with respect to others.

1. Two factor groups, temporal adverbial and noun number, were selected as significant in the variable-rule analyses in both varieties and showed the same constraint hierarchy (proximate and frequency adverbials are favorable to the PP, as are plurals). This shared linguistic conditioning indicates that the PP in Peninsular Spanish retains diachronically older perfect functions.

2. Two factor groups, Aktionsart and clause type, were significant in one variety but had no discernible effect in the other. The disfavoring by punctual predicates (achievements) is an indication of aspectual restrictions on the PP in Mexican Spanish. In contrast the difference between punctual and durative was insubstantial in the Peninsular data. Neither was clause type selected as significant in Peninsular Spanish (although the direction of effect appears the same, yes-no and WH questions have virtually the same PP rate and relatives no longer particularly favor).Footnote 19 This divergence in linguistic conditioning indicates that the Peninsular PP has traveled further along the grammaticalization path toward past perfective.

3. Two factor groups present contrasting constraint hierarchies, ya co-occurrence and temporal reference. In Mexican Spanish, with ya the PP rate is not higher than without ya, but in Peninsular, co-occurring ya favors the PP. With respect to temporal reference, in Mexican Spanish, the PP is most strongly favored in irrelevant contexts and most disfavored by specific temporal reference, which is consonant with experiential and continuative (persistent situation) perfect uses. Irrelevant temporal reference “remains” a highly favorable context in Peninsular Spanish, as the retention in grammaticalization hypothesis (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:16) would predict.Footnote 20 However, specific today contexts are equally favorable, consonant with the Peninsular PP's hodiernal perfective function.

In short, comparison of the linguistic conditioning of PP-Preterit variation in Peninsular and Mexican data shows that even though the Peninsular PP retains canonical perfect functions, it has also generalized to perfective uses.

Second, consider the most frequent and the least specified contexts, which coincide for most of our factor groups: no temporal adverbial, main declarative clauses, singular number. Figure 4 indicates for each factor group the variant with the higher relative frequency in the context that is the most frequent or the least specified. This is the role of the Preterit in all rows of the Mexican column but of the PP in the Peninsular column. Illustrative of the Peninsular PP's default status is (37), referring to a hypothetical situation in a math problem.

(37) Y se ha vendido a diez mil pesetas el quintal. ¿Cuántas pesetas se ha sacado en total? (BCON007B)

‘[a math problem] And it was sold (PP) for ten thousand pesetas per quintal (hundred-weight). How many pesetas were gained (PP) in total?’

We have thus identified the general, or default, past perfective exponent in each variety. Similarly, in Poplack and Malvar's (Reference Poplack and Malvar2007) study of the diachrony of the future temporal reference domain in Brazilian Portuguese, the default variant, the synthetic -rei form earlier in the language's history and the ir ‘go’-based periphrasis today, is the one preferred in “frequent, neutral or unmarked contexts.” In the present-day Spanish of Castellón, Spain, evidence that the default (“unmarked,” in the author's terms) future variant is the go-based periphrasis is that it is favored in “the less marked contexts” such as those without any temporal adverbial (Blas Arroyo, Reference Blas Arroyo2008). These are the contexts we are calling the least specified.