Introduction

An informal carer (hereafter referred to as a ‘carer’) is anyone who ‘looks after a family member, partner or friend who needs help because of their illness, frailty, disability, a mental health problem or an addiction and cannot cope without their support’ (NHS England, 2019). Compared with the general population, carers are at an increased risk of developing their own physical or mental health problems (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Onwumere, Craig, McManus, Bebbington and Kuipers2014). Carers specifically of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis (FEP) report chronic distress (Barrowclough et al., Reference Barrowclough, Gooding, Hartley, Lee and Lobban2014), burnout (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Lotey, Schulz, James, Afsharzadegan, Harvey and Raune2017b), report feeling invisible (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Moone and Wellman2005), high levels of stress, and a lack of social support (Sadath et al., Reference Sadath, Muralidhar, Varambally, Gangadhar and Jose2017).

Carers are an integral part of the mental health service system (Worthington et al., Reference Worthington, Rooney and Hannan2016). Economic analyses have estimated that the support provided by carers to those with psychosis is valued at £1.25 billion a year (Andrew et al., Reference Andrew, Knapp, McCrone, Parsonage and Trachtenberg2012). To enable carers to continue caring, NICE (2014) recommend that all carers should be offered a carer-specific education and support programme, and provision of this is monitored via the Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) access and waiting standards (NICE, 2016; SNOMED CT, 2019). Yet, the availability of carer support services has historically been low, largely due to a lack of time and funding (Buckner and Yeandle, Reference Buckner and Yeandle2011; Carers UK, 2007, 2014; Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Glentworth, Haddock, Bentley and Lobban2015). To improve EIP services’ ability to implement and deliver carer education and support programmes in line with the aforementioned standards, it is vital that such interventions make the most efficient use of the available resources.

Studies have shown that psychoeducation is an effective intervention for improving the wellbeing of carers of people with psychosis (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Gillard, Spain, Cornelius, Chen and Henderson2017). The goal of such interventions is to improve the wellbeing of carers, but the target, and thus the hypothesised cause of distress, varies across interventions (Sin and Norman, Reference Sin and Norman2013), e.g. problem-solving (Abramowitz and Coursey, Reference Abramowitz and Coursey1989), stress management techniques (Chien and Wong, Reference Chien and Wong2007), coping strategy enhancement (Szmukler et al., Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese, Maphosa and Staples2003), psychosis symptom management strategies (Tel and Esmek, Reference Tel and Esmek2006) and illness beliefs (Riley et al., Reference Riley, Gregory, Bellinger, Davies, Mabbott and Sabourin2011). The last of these proposed mechanisms has consistently been found to correlate with carer wellbeing. That is, carers’ beliefs that psychosis will negatively impact the family (Addington et al., Reference Addington, Coldham, Jones, Ko and Addington2003), self- and patient-directed blame (Fortune et al., Reference Fortune, Smith and Garvey2005), and feeling out of control (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler, Freeman and Garety2008) were associated with poor wellbeing.

In our previous study, we tested a three-session psychoeducation intervention for carers of people with FEP, targeting less adaptive illness beliefs, such as those related to self-blame and control in relation to psychosis symptoms, and knowledge about the illness and likelihood for recovery (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a). The results from 68 carers revealed significant improvements in all eight target illness beliefs tested, i.e. illness consequences (carers’ belief that psychosis will negatively impact their own and the patients’ lives), blame (carer self-blame and how much they direct towards the patient), illness control (carers beliefs about the degree of control the patient has over their problems), illness understanding (understanding of patients’ psychosis), and coping confidence (confidence in their ability to care for the patient). However, to aid future implementation, it is important to make most efficient use of the limited available resources discussed above while also being of benefit to carers. We therefore developed an abbreviated version of the psychoeducation intervention that can be delivered in a single two-hour session.

The aim of this service evaluation is to evaluate an abbreviated, sole-session version of the psychoeducation intervention, and compare the effectiveness of this intervention with our previously tested, and more intensive, three-session version of the intervention (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a). Within our service, we sought to answer the following questions: (1) does a one-session psychoeducation intervention change illness beliefs amongst carers of people with FEP?; and (2) are the outcomes from the one-session version of this intervention similar to those obtained using the three-session format?

Method

Service evaluation

This service evaluation compared outcomes before and after attending the psychoeducation intervention (i.e. pre–post data collection). Carers attended either the sole- or three-session (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a) version of the psychoeducation intervention delivered via a single NHS EIP service. The present project was classified as a service evaluation by the Central and North-West London (CNWL) NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development team, the CNWL Service Director, and the Borough Lead.

Intervention

The psychoeducation intervention was delivered in an evening group format over either three (original version) (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a) or a sole (abbreviated version) two-hour long session(s). Both psychoeducation packages were devised by a clinical psychologist with BABCP accreditation for cognitive therapy supervision (D.R.), and were delivered by senior clinicians working in the EIPS team (D.R., S.S., S.R.). Using a lecture style format, the intervention aimed to target illness beliefs in the context of bio-psycho-social and cognitive frameworks. Using evidence-based literature, the session(s) focused on understanding what psychosis is, the causes, and available interventions, as well as adaptive caring styles and supporting carer wellbeing. Both the sole-session and three-session versions (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a) of the intervention covered the same topics; but in the sole-session, the information was refined, focusing on only the key messages in relation to each of the topics. In both interventions, carers received copies of the PowerPoint slides, a copy of an information booklet deigned for carers of people with psychosis (Rouf et al., Reference Rouf, Close and Rosen2008), and information about local carer support organisations.

Procedure

Carers were invited to attend the sole session psychoeducation group by a member of the EIPS team. Any carers that expressed an interest in attending were followed up by letter. Carers were asked to complete an assessment before the group (pre-intervention) and immediately after (post-intervention). Assistant psychologists supported carers to complete the questionnaires and ascertain written consent for publication.

Carers

All the intervention attendees were carers of service-users of the Harrow and Hillingdon Early Intervention in Psychosis Service (EIPS) in the Central North West London (CNWL) Foundation NHS Trust. This EIPS is open to people aged 14–34 years who are experiencing first episode psychosis (FEP), with a duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) of less than 12 months.

Sole-session group

A total of 20 carers who between them cared for 16 patients (some patients had more than one carer in attendance) attended the sole-session psychoeducation group. Of these 20, 17 (89%) carers, representing 14 patients, are included in the final analysis: one carer withdrew their data from this publication, and two provided incomplete data.

Three-session group

For the purposes of the between-group analysis, data from our previous study testing the three-session version of this intervention was used (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a). All participants had provided consent for their anonymous data to be shared with other researchers and used for future publications. All carers providing full datasets from this study were included here – this resulted in a sample size of 68 carers.

Measures

The same assessment pack was used in the present service evaluation as was used in the research study investigating the effects of the more intensive, three-session version (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a). The assessment included a brief demographic questionnaire (6 items), and a 10-item illness belief questionnaire (Broadbent et al., Reference Broadbent, Petrie, Main and Weinman2006; Lobban et al., Reference Lobban, Barrowclough and Jones2005). Using visual analogue scales (VAS), anchored at 0 to 100%, carers were asked to numerically specify the conviction of their beliefs. For example: ‘How likely do you think it is that your relative will experience another episode of psychosis in the future?’, with a VAS from 0% denoting relapse impossible, to 100% denoting relapse certain.

Analysis

We did not have sufficient statistical power to conduct significance testing. Instead, we firstly calculated the pre–post effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals to assess the pre–post changes in all 10 illness beliefs amongst those carers who received the sole-session psychoeducation intervention. To calculate these effect sizes, we used a default correlation of r = 0.5 as recommended by Schmidt and Hunter (Reference Schmidt and Hunter2014). Secondly, we calculated the between-group effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals comparing the post-intervention scores from those carers who received the sole-session version and those who received the original three-session version (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a). Where the 95% confidence intervals do not include 0, this indicated that an effect size was significant at the p < .05 level (Field, Reference Field2013). All effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d, and calculated using the syntax produced by Wilson (Reference Wilson2011). The effect sizes are interpreted in line with Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1988) cut-offs (0.2 = small; 0.5 = medium; 0.8 = large).

Results

Sample characteristics

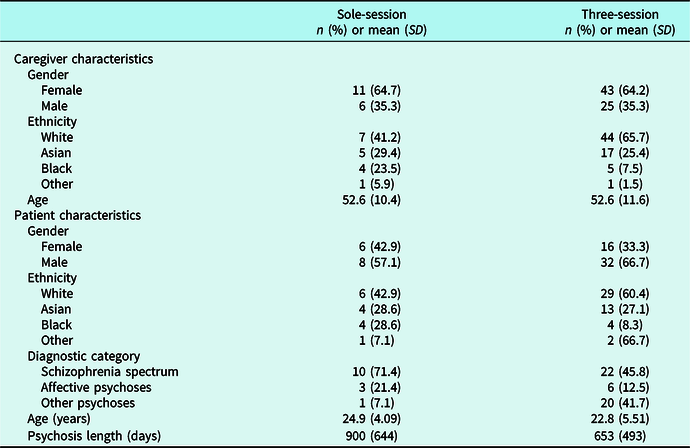

The demographics descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. The carers were mostly White British, female, in their early 50s, and tended to be providing support to a male patient with a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis who had been experiencing symptoms for less than 3 years.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of sample characteristics

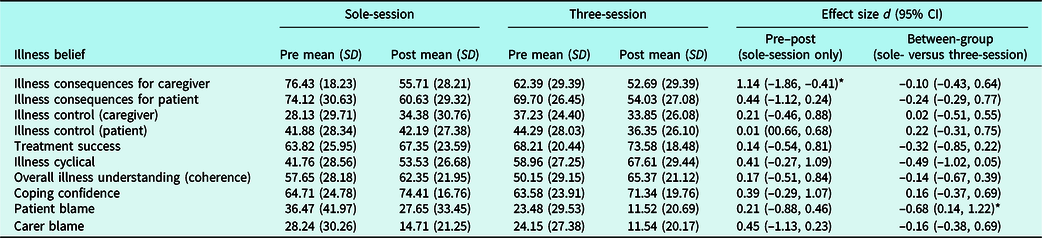

Table 2. Effect sizes of the pre–post changes in illness beliefs for the sole session intervention, and between-group effects of the sole-session versus three-session version of the psychoeducation intervention

d, Cohen’s d; SD, standard deviation; *confidence intervals do not include 0 (i.e. p<.05); the data from the three-session version was collected as part of a separate project (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a,b); effect sizes are coded so that a positive effect size reflects either a pre–post improvement of the illness belief in the desired direction and/or indicates superiority of the sole session version of the intervention over the three-session format.

Pre–post effects of the sole-session intervention

All the illness beliefs improved post-intervention in the desired direction; however, the change in carers’ perceptions of their relatives’ ability to control their condition was minimal. The largest effect size was found in relation to carers’ reduced conviction that any future episodes of psychosis would negatively impact their own life; notably, this was the only large pre–post effect size. We found a medium-sized reduction in carers’ conviction that they were to blame for their relative’s psychosis, and that a further episode of psychosis would negatively impact their relative’s life, as well as a moderate increase in endorsing psychosis as a cyclical condition. All other effects were small. See Table 2 for effect sizes.

Between-group effects of the sole-session intervention versus the three-session intervention

The results of the sole-session intervention were compared with the data collected from a previous study testing a three-session version of the same intervention (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a). All the effects, with the exception of those related to illness control and coping confidence, favoured the three-session version of the intervention over the sole-session version. The largest between-group effect was found in relation to patient blame, whereby those who received the three-session version placed less blame on their relative for their current condition, compared with those who received the sole-session version. Those who received the three-session version compared with the sole-session version, believed more strongly to a moderate degree that psychosis was a cyclical condition. All other between-group effects were small to negligible. See Table 2 for effect sizes.

Discussion

The aim of this service evaluation was to evaluate a sole-session psychoeducation intervention for carers of people with FEP and compare its outcomes on illness beliefs with a three-session version that was previously tested within the same service as part of a separate project (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a). All the illness beliefs changed in the desired direction after carers attended the sole session psychoeducation intervention, with the greatest improvement seen in carers’ conviction that their relative’s psychosis does not necessarily have to negatively impact their own life. The between-group effects comparing the sole-session and three-session versions of the intervention (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a), mostly favoured the three-session version but were also small in size, suggesting that both interventions, irrespective of duration, were associated with a similar magnitude of change. The exception to this finding was that those who attended the three-session version (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a) showed a greater improvement in the ‘patient blame’ and ‘illness cyclical’ beliefs.

Psychoeducation addresses a key unmet need amongst carers of people with FEP, i.e. carers want to learn about psychosis, and what they can do to support their relative (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Moone and Wellman2005). The present intervention aimed to address this need by targeting illness beliefs. All the beliefs changed post-intervention in the desired direction, but varied in the magnitude of change. Two of the beliefs with the greatest change (illness consequences for carer and relative blame) have been found to be core correlates of distress amongst carers of people with FEP (Kuipers et al., Reference Kuipers, Onwumere and Bebbington2010). These beliefs also emerge within qualitative studies where carers were asked to discuss some of the concerns and challenges associated with providing support to someone with FEP. For example, carers frequently report feeling responsible for their relative’s mental health problems, especially during the earliest phases of psychosis (i.e. relative blame) (McCann et al., Reference McCann, Lubman and Clark2011). Future-focused concerns are also prevalent, with many carers reporting their fear of their relative relapsing and the likely negative impact that this will have on their own lives (i.e. illness consequences for carer) (Lal et al., Reference Lal, Malla, Marandola, Thériault, Tibbo, Manchanda and Banks2019). So, although not all the illness beliefs greatly improved post-intervention, it may be that changing these beliefs is sufficient to produce a noticeable impact on carer’s wellbeing. Research is needed to test this hypothesis.

The findings of this service evaluation provide an initial suggestion that reducing the number of sessions does not substantially reduce the effectiveness of this psychoeducation intervention. This result corresponds with findings from a recent meta-analysis of all psychoeducation interventions for carers of people with psychosis that show neither the duration nor the amount of contact time predicted treatment outcomes (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Gillard, Spain, Cornelius, Chen and Henderson2017). Resource-light interventions for carers are beneficial not only to mental health services, but for carers themselves. FEP services are stretched (Adamson et al., Reference Adamson, Barrass, McConville, Irikok, Taylor, Pitt and Price2018) so a briefer intervention for carers may be more feasible for mental health practitioners to deliver. Similarly, a fundamental challenge associated with being a carer is finding time for yourself (Cleary et al., Reference Cleary, Freeman and Walter2006) – so, again, an intervention that requires less of a time commitment may be easier for carers to attend.

Limitations

In addition to the inherent methodological limitations associated with service evaluations, the sole-session sub-sample was small (n = 17), resulting in broad confidence intervals surrounding the effect sizes. Moreover, the sample sizes within the between-group analyses were unequal, and non-randomised. The service evaluation was conducted within a single EIP service, with carers who were largely females defined as being of White British ethnicity. Our sample is arguably limited in representativeness, especially as psychosis is more common amongst Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) communities (Jongsma et al., Reference Jongsma, Turner, Kirkbride and Jones2019).

There is also a likelihood that our findings are susceptible to a selection bias. Feelings of frustration with mental health services can be common amongst carers (Askey et al., Reference Askey, Holmshaw, Gamble and Gray2009), and previous experience suggests that those carers who have difficult relationships with services are unlikely to become involved in projects promoted by clinicians (Hazell et al., Reference Hazell, Jones, Pandey and Smith2019). It may be that the carers who agreed to participate in these psychoeducation interventions have particularly good relationships with their EIP service, and therefore do not represent the most disenfranchised carers.

There are several questions outstanding from the present service evaluation. For example, we cannot make any claims regarding the uptake of this psychoeducation intervention as we did not collect any data on the number of carers who declined to attend. We are also unable to offer any conclusions as to the impact of the post-session handouts (booklet and slides) on illness beliefs, or how use of these handouts may influence the durability of any changes. Finally, in relation to the limited representativeness of our service evaluation, we must verify whether the current content is appropriate for male and/or BME carers – especially as perceptions of psychosis can differ in relation to ethnicity (Islam et al., Reference Islam, Rabiee and Singh2015) and gender (Fortune et al., Reference Fortune, Smith and Garvey2005; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Chawla, Krynicki, Rankin and Upthegrove2014).

Research implications

There are several questions outstanding from the present service evaluation that require investigation as part of a purposive research study. The priority would be to test the effectiveness of the sole-session intervention using a randomised controlled trial design, with adequate statistical power and follow-up assessments to assess the longer-term effects. Ideally this research study would also seek to answer the questions identified above.

The outcome of interest here was illness beliefs – this target is based on evidence demonstrating that less adaptive illness beliefs can predict carer burn-out (Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Lotey, Schulz, James, Afsharzadegan, Harvey and Raune2017b). However, in the present service evaluation we were unable to test this proposed mechanism and therefore cannot make any claims as to the impact of the sole-session intervention on carer wellbeing or distress. Future research studies should therefore also include measures of carer functioning, and wellbeing.

Conducting robust research trials to ascertain the effectiveness of the sole-session intervention should be carried out while simultaneously considering any further barriers to implementation. Focusing on both efficacy and feasibility concurrently will, assuming the intervention is found to be effective, aid dissemination of this learning to EIP services.

Clinical implications

Although family interventions are recommended for those using EIP services (NICE, 2014), there are a number of practical barriers impeding its delivery (Eassom et al., Reference Eassom, Giacco, Dirik and Priebe2014). Psychoeducation offers an opportunity to provide support to carers when family therapy is not feasible or is declined. Moreover, the present findings support the continued delivery of the sole-session psychoeducation intervention within our EIP service. The intervention requires further testing in the context of a research trial in order to support its implementation to other EIP services.

Moreover, the results indicated that for two of the illness beliefs (i.e. ‘patient blame’ and ‘illness cyclical’ beliefs), the improvements were greater for carers who completed the three-session version of the intervention over the sole-session version. These findings suggest that more time is needed to change these beliefs. To improve the efficacy of the sole-session psychoeducation intervention we may need to review the amount of time dedicated to each of the illness beliefs within the sole-session protocol and consider adjustments so that greater weighting is given to the ‘patient blame’ and ‘illness cyclical’ beliefs. However, we will need to evaluate whether such a change would have deleterious effects on conviction ratings of the other illness beliefs.

Conclusion

This initial service evaluation provides tentative evidence in support of a sole-session psychoeducation intervention to improve illness beliefs amongst carers of people with FEP, and that these effects may largely be comparable to a more resource-intensive (three session; Onwumere et al., Reference Onwumere, Glover, Whittaker, Rahim, Chu Man, James and Raune2017a) version of this intervention. These findings require replication within a randomised controlled trial that tests the proposed mechanism of action as well as the durability of any treatment effects.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank Alastair Penman, Krishan Sahota, Lynis Lewis, Mellisha Padayatchi and Emily Hickson for their support in conducting this service evaluation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Financial support

This work was supported by a grant from the North London Clinical Research Network (NOCLOR) awarded to David Raune.

Ethical statements

All authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. No ethical approval was required as the data presented here was collected as part of a routine service evaluation. However, participants were asked to provide consent for their data to be used as part of this publication.

Key practice points

(1) It is possible for key illness beliefs to be improved in a single psychoeducation session.

(2) There are little differences in the benefits obtained for carers of people with psychosis via a single session of psychoeducation compared with those obtained in a more intensive, three-session version.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.