1. Introduction

In the year 1646, in Nazareth, a girl named Barbara married a Catholic man from Bethlehem, Joseph, also known as ‘the doctor's son’.Footnote 1 Barbara was the daughter of the dragoman (i.e. interpreter and gatekeeper) of the local Franciscan convent, Beniamin alias Gemini.Footnote 2 Like her father Barbara was a member of the Syriac Maronite Church, an Eastern Catholic Church in full communion with Rome. After the wedding, Barbara left Nazareth and moved to Bethlehem – a distance of some hundred and twenty kilometres – with her husband. A few years later, in 1652, the names of Barbara and Joseph reappear in the Franciscans’ sacramental registers on the occasion of the baptism of their daughter Helena. The baptism took place in Jerusalem, although, according to the record, the couple was still living in Bethlehem.Footnote 3

The movements of this young couple may appear unremarkable to a historian of early modern Europe, a context in which people's short-distance mobility has been amply studied.Footnote 4 When seen in the context of current research on Christian migration in the Ottoman Middle East, however, this story turns into an important example of forms of mobility, such as marriage migration and movements between villages, that have so far been scarcely explored. Drawing on the reconstruction of stories like Joseph and Barbara's, this article addresses these forms of local mobility and discusses their role in processes of confession and community building in seventeenth-century Ottoman Palestine.

In the seventeenth century, Palestine and the whole Middle East were predominantly Muslim. The spread of Islam in the area had begun in the seventh century, with the Arab conquest and the defeat of the Byzantines. The life of those Jews, Samaritans and Christians who had resisted the spread of Islam was regulated by the dhimma system.Footnote 5 Under this system, these groups enjoyed a certain freedom of religion, provided that they paid the poll tax and acknowledged the superiority of Islam. Until the sixteenth century, Christians were mostly members of either the Eastern Churches or the Greek Orthodox one, and the only Catholics in the area were foreign merchants. The situation changed with the outbreak of the Reformation in Europe, which pushed the Catholic Church to gain new ground in the Levant. During the last decades of the sixteenth century, missionaries embarked toward Ottoman lands with the aim of encouraging local Christians’ communion with Rome.Footnote 6 In Palestine, Catholicism spread among the local Christian population mainly thanks to the efforts of the Franciscans of the Custodia Terrae Sanctae (The Custody of the Holy Land), discussed below.Footnote 7 This was the name by which the Franciscan Province of the Holy Land was known for centuries.Footnote 8 It had been founded by St. Francis in 1217 with the aim of guarding the Holy Sites and providing spiritual assistance to Catholic pilgrims and merchants residing in the area.Footnote 9 From the last decades of the sixteenth century onwards, the friars began to pursue the ‘reconciliation’ of the local Christians. This process went hand in hand with the building of a Catholic community separated from the Orthodox one. At a time when the Catholic and Protestant Churches in Europe were struggling to build well-defined confessional identities, Rome's priority in the Middle East soon became the construction of a local Catholic identity and the establishment of confessional boundaries between those who were reconciled with Catholicism and the other Christian denominations.Footnote 10 The task was particularly necessary and at the same time challenging in an area such as the Middle East, where many Christian denominations shared sacred spaces, and sacramental sharing (communicatio in sacris) was widespread.Footnote 11

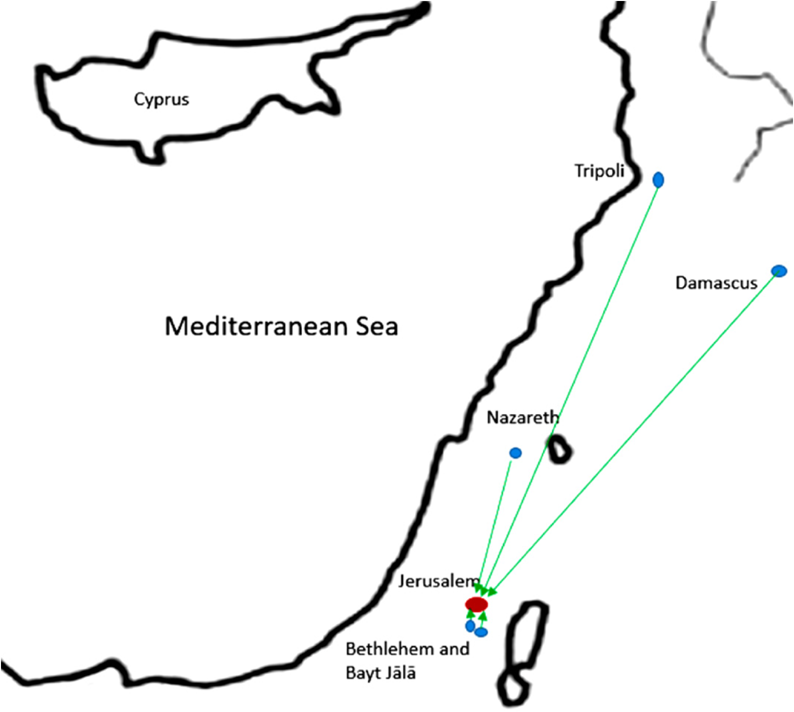

Christian mobility has been amply explored by research on the religious history of the Middle East and on the changes in the presence and distribution of the Christian population from the Arab conquest onwards. These works have uncovered processes of urbanisation involving the Christian population in the whole Middle East.Footnote 12 Similar trends have also been described with specific reference to Palestine, and in particular, to the area around Jerusalem.Footnote 13 The main reason underlying these movements was the desire on the part of Christian minorities to join larger and wealthier communities. The centrality of urban areas – and in particular of Jerusalem – as poles of attraction both at a local and at a regional level is also emphasised in research specifically focused on the Catholic minority. Bernard Heyberger has comprehensively described movements from Damascus and present-day Lebanon to Jerusalem during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 14 Elsewhere, I have reconstructed Catholics’ movements from nearby Bethlehem towards seventeenth-century Jerusalem via an analysis of Jerusalem parish booksFootnote 15 (see Figure 1). But what were the specificities of Catholic mobility in the first phase of the diffusion of Catholicism in the area? How were these characteristics related to the development of a parish system in the area? And what role did mobility play in the development of local Catholic communities separated from the Orthodox ones?

Figure 1. Catholic migration towards Jerusalem in the seventeenth century.

The article approaches these questions through an analysis of Catholics’ movements between Palestinian villages in the seventeenth century. In doing so, it also addresses wider issues to do with the relationship between mobility and processes of confessionalisation. Thus, it contributes to current historiographical debates on the plurality of seventeenth-century Catholicism and on the global Counter-Reformation. Introduced in the late 1970s by Heinz Schilling and Wolfgang Reinhard, the concept of confessionalisation refers to the process by which both Catholic and Protestant churches, in cooperation with the developing states, built clearly defined confessional churches. They did so by fighting against medieval religious practices, enhancing conformity and social discipline among their flocks and fostering the development of strong confessional borders.Footnote 16 Over the years, many aspects of the confessionalisation paradigm have been criticised, such as the alleged uniformity of the early modern confessional churches.Footnote 17 With specific regard to the implementation of the Catholic Reformation (or Counter-Reformation),Footnote 18 studies of various areas have shed light on a variety of local outcomes resulting from numerous factors, such as the distance from Rome of the area in question and the political context.Footnote 19 Thanks to the work of scholars such as Simon Ditchfield,Footnote 20 the scope of this debate on the diversification of seventeenth-century Catholicism has recently acquired a global dimension as scholars have begun to explore the nature and consequences of the Counter-Reformation outside Europe.Footnote 21 This article contributes to this line of inquiry by discussing how the local context shaped the relationship between mobility and processes of confession and community building in seventeenth-century Palestine.

For a long time now, works on the Reformation in Europe have acknowledged a connection between the strengthening of confessional identities and geographical mobility.Footnote 22 Most works on the topic are concerned with long-distance and forced migrations, the integration of refugees and exiles into the receiving societies, and the development of new religious identities among persecuted minorities.Footnote 23 In Palestine, the building of a Catholic identity was entangled with the spread of Catholicism, the growth of a tiny Catholic minority and the establishment of a sacramental system separated from the Orthodox one. In addition, unlike in Europe, in Ottoman Palestine, none of the competing Christian churches was backed by a political power. So, the strengthening of confessional identities did not trigger political persecutions and forced migrations, but it did produce other forms of mobility, mostly within a relatively small area. These movements, aimed as they were at finding a suitable partner or at accessing the sacraments, were similar to those of the early modern European peasantry; yet, they were strongly connected with the processes of confession and community building.

This article reconstructs Catholics’ geographical mobility in semi-rural Palestine, focusing on the area around Bethlehem and relying on data extracted from sacramental records. Bethlehem was one of the largest villages of the district of Jerusalem and according to an Ottoman survey, in 1690–1691, the Christian inhabitants of the village were 650 in number and constituted the majority of its population.Footnote 24 Bethlehem parish records have never been studied systematically, but they are a valuable source for understanding the parish's development and demography, as well as Catholics’ geographical mobility; most importantly, they allow me to see the relationship between the two.Footnote 25

In this case, the use of a micro-historical approach has many methodological advantages.Footnote 26 For example, by unveiling local phenomena that would otherwise elude us, it allows us to test the validity of general paradigms and explore the local manifestations of wider historical events. Indeed, this small-scale analysis sheds light on the existence of unstudied movements between villages, related to the administration of sacraments or the desire to find a suitable partner. Although the dataset is not big enough to allow for statistically significant quantitative analysis, the gathered data do question the centrality of Jerusalem and the importance of urbanisation processes as postulated by previous studies on Christian mobility in the Ottoman Middle East, and they enrich a historiography that has traditionally centred on household and long-term mobility.

Taking an analysis of Catholic mobility as a starting point, the article argues that the movements between villages are consistent with the development of new poles of attraction and the establishment of a Catholic sacramental system resulting from the expansion of Catholicism. The data also strongly suggest that in a context in which confessional identities were being strengthened, and similarly to confessional migration in Europe, local mobility not only resulted from, but also actively contributed to processes of confession- and community-building. Finally, in the wider framework of the current debates on the global Counter-Reformation, this article argues that the local context shaped not only the nature of reformed Catholicism outside Europe but also the relationship between mobility and confessionalisation.

What follows describes the development of the parish of Bethlehem and then discusses two types of mobility: mobility with the aim of receiving sacraments and marriage mobility. Before I proceed, however, let me introduce the sources and the methodology of this research.

2. Sources and methodology: Family reconstruction through the parish book of Bethlehem

The sacramental registers of the parish of St. Catherine in Bethlehem are one of the most complete collections of parish records from Palestine.Footnote 27 The first volume, ‘Registrazioni miste’, records baptisms starting from 1619, and burials and nuptials from 1633 and 1652, respectively.Footnote 28 A second series of books starts in 1669 and extends well into the eighteenth century.Footnote 29

Palestinian parish records furnish more or less the same information as their European counterparts. Sacraments are registered in small paragraphs, each recording the date and the place in which the sacrament was administered; the name of those who received it and usually the name of his/her parents. In addition to this basic information, other data more directly relevant to each sacrament are also recorded, complying with the prescription of the Council of Trent. In the case of baptisms, for example, records often mention the godparents’ names and their birthplace. The libri defunctorum (burial registers) often give details on the age of the deceased and whether or not he/she had received the last sacraments. Following the Tridentine prescriptions, the libri coniugatorum (marriage registers) usually report the names of the two witnesses and of the parish priest who celebrated the nuptials, and any dispensations required for consanguinity and affinity. They also mention the witnesses’ places of origin, and occasionally their family ties to the groom or the bride. Generally speaking, the records became more standardised with the passing of time; nonetheless, the presence or lack of certain details, such as wives’ and mothers’ patronymics or the birthplace of the people mentioned, also varied depending on the parish priest who was in charge of the recording. This also affects the length of the paragraphs, which is usually between four and eight lines. The number of sacraments recorded in each page, therefore, greatly varies as well.

A wide range of different techniques has been used to analyse parish books, such as aggregative analysis of parish registersFootnote 30 and family reconstruction or reconstitution. In order to study individuals’ mobility, this research uses the technique of family reconstruction: the process of linking together (parish) records of baptisms, marriages and burials,Footnote 31 gathered, in this case, from the above-mentioned sacramental registers of Bethlehem and sometimes crosschecked with data extracted from those of Jerusalem and from ‘mixed volumes’.Footnote 32 These record sacraments administered in different parishes and were common before the 1670s, when Catholic communities were few in number.

Many scholars have pointed out the time-consuming nature of family reconstruction.Footnote 33 In the case of Palestinian parish registers, this shortcoming is accentuated by the specific characteristics of Palestinian parish records, as compared to European ones. Firstly, the use of nominal information to link records relating to the same individual, the procedure that characterises family reconstruction, is affected by the lack of surnames. In seventeenth-century Palestine, people were mostly identified by the patronymic (nasab) alongside their given name.Footnote 34 In some cases, however, patronymics are not mentioned. This is especially common with individuals coming from Bayt Jālā and Bayt Saḥūr and might be linked with the small size of these Catholic communities and the fact that they had been in existence for a relatively short time.Footnote 35

Leaving aside the problem of surnames, Christian names, too, may cause problems. The friars used to give converts a new name; sometimes the second name was the Italian or Latin translation of the earlier Arab one, while at other times, it was a name linked to the Catholic European tradition, such as Franciscus. This practice contributed to distinguishing Catholics from the other Christian denominations and was part of a wider process of westernisation of habits, which would become more evident in the following century. Going back to the analysis of sacramental records, the presence of two names is problematic because they were used interchangeably in entries to refer to the same person. In this respect, the entries of Friar Franciscus from the Province of Granada, who was parish priest in the 1690s, are particularly telling, as he often writes down both names. Referring to the daughter of Giamino from Nazareth, for example, he records both Helena and Qudsia as names; in another entry, next to the name Zaituna, he writes the translation Oliva (Italian for ‘olive’).Footnote 36

In addition to those spelling inconsistencies that are common in early modern sources, further problems are created by the fact that the language of the local Christians was Arabic. Some of the names were Muslim, derived from the Qurʾān, such as Gazale,Footnote 37 and even when names were rooted in the biblical tradition, they were Arabic versions of biblical or Christian names, primarily written in Arabic characters. The friars therefore had to transcribe the name in Latin characters, and this process generated ambiguities. Moreover, since many of the Franciscans were Italian, local names were often italianised.

For all these reasons, in most cases, the identification of individuals was only made possible by crosschecking the name of the spouse and some additional information, such as the name of the grandfather or an epithet (cognomen), such as ‘Il Dottore’, or ‘Matar’. Epithets run through family members and allow the reconstruction of family genealogies, but unfortunately, they are common only for those families who had already been Catholic for some generations and – as shown by Jacob Norris – represented the core of the Catholic community in Bethlehem.Footnote 38 This additional information was mostly recorded by parish priests – especially from the 1680s onwards – who probably felt the need to better identify the parishioners. However, sometimes they were clearly added at a later stage, on the left side of the entries.Footnote 39

Leaving aside the difficulties in identifying individuals, the use of the technique of family reconstruction is also affected by the fact that especially in the first decades of the parish's existence the recording is not fully reliable and consistent. Despite these problems, thanks to the information provided by different books, it has been possible to shed light on a number of mobility patterns and to gather some interesting insights on the demography and the development of the Bethlehem parish of St. Catherine.

3. The historical context: the development of the Franciscan parish of Bethlehem

In Palestine, the arrival of the Crusaders and the establishment of the Latin kingdoms in the eleventh century led to the first establishment of a Catholic episcopal hierarchy, with responsibility for the care of souls organised by parishes, which in turn belonged to dioceses. With the fall of the kingdom of Jerusalem (1291), however, this organisation collapsed and the regular clergy left. Since their return to the region in the fourteenth century, the Franciscans had had a few parishes in the Syro-Palestinian region, mostly in places with a well-established presence of European merchants and diplomats. However, because of the lack of local Catholics, and therefore a small number of followers, dioceses were never established again. In the seventeenth century, the progression of the friars’ missionary activity led to the establishment of a complex system for the administration of the cure of souls, whose centre was the convent of St. Saviour in Jerusalem. This process was strengthened by the converts’ adoption of the Latin riteFootnote 40 – prompted by the friars, despite the protests of De Propaganda Fide.Footnote 41 Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Propaganda asserted the legitimacy of Oriental liturgies and rites and prevented those who had been reconciled by missionaries from adopting the Latin ones.Footnote 42 New Catholics would therefore generally become part of the newly established Catholic Eastern Churches, which retained their own liturgical tradition and organisation and were led by local clergy. This was not the case with those reconciled by the Franciscans. In fact, as a consequence of the adoption of the Latin rite, they were instead integrated into a new sacramental system established by the Franciscans.

Those parishes that already existed, which up to then had been almost exclusively devoted to the spiritual care of Catholic foreigners, each acquired a second parish priest in charge of the local, Arab, population.Footnote 43 In addition, new parishes were founded. The parish of Nazareth was created in 1620, and later on, the friars established parishes in Jaffa (1654) and ʿAyn Kārim (1674).Footnote 44 When compared to their European counterparts, Palestinian parishes had some specific features – such as the lack of clear territorial boundaries and the lack of parish fees – which were a consequence of the political and religious context.Footnote 45 Their demographic growth is well documented and has already been studied by scholars, mainly through the reports sent by the Custos (the head of the Custody of the Holy Land) to Propaganda Fide. According to one of these letters, for example, in 1664, the parish of Jerusalem numbered 68 souls, St Nicodemus in Ramla, 60, Nazareth 24 and Bethlehem 128.Footnote 46 By 1702, the number of Catholics in Bethlehem had grown to 325.Footnote 47 More details on the process are provided by parish books. If we consider Figure 2, we can see how the number of baptisms grew in Bethlehem in the course of the century. Until 1669, the yearly average was 5.28 baptisms, increasing up to 14.4 in the years between 1669 and the end of the century. The growth of the Catholic community in the town is confirmed by the data regarding marriages (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Number of baptisms in Bethlehem (1618–1699).

Figure 3. Number of marriages in Bethlehem (1619–1699).

The development of the parish of Bethlehem was completed by the creation of two small Catholic ‘pockets’ in neighbouring Bayt Jālā and Bayt Saḥūr. These both belonged to the parish of Bethlehem (as there was no parish church in either, their inhabitants are mentioned in the Bethlehem sacramental books). According to the books and to the correspondence between the Custodia and Propaganda Fide, the spread of Catholicism in Bayt Jālā started in 1676–1677.Footnote 48 The presence of Catholics in Bayt Saḥūr is mentioned for the first time in a letter to Propaganda Fide in 1692,Footnote 49 but in the Bethlehem parish records, the baptism of a child from the village was recorded as early as 1683.Footnote 50

The parish records also provide evidence of the problematic implementation of reformed Catholicism in Bethlehem. Indeed, the first decades of the existence of the Bethlehem parish were characterised, on the one hand, by difficulties in establishing a Catholic community separate from the other denominations, and on the other by the ongoing development of a parish organisation complying with the prescriptions of the Council of Trent. The latter element is well exemplified by the increasing definiteness of the role of the parish priest over the century. Until the 1670s sacraments were frequently administered by the Guardian of the convent – who would often also retain the office of parish priest – and sometimes by the Guardian of Jerusalem, the Custos. In those cases in which baptisms were administered by other priests, the record says that they had been received in a delegation from the Guardian of Bethlehem. In August 1670, for example, baptisms were administered by the Maronite presbyter Giorgio whom, according to the records, the Guardian had charged with the care of souls during the plague, ‘peste grassante’. In July 1672, baptisms were still administered by Bernardino da Movano, ‘Parish priest and Guardian of this convent of St Catherine’. However, during the 1670s things slowly started to change. According to the book of baptisms in October 1672 Dioniso da Cutro was appointed parish priest by the Custos, Theofilo da Nola.Footnote 51 From this moment on, sacraments were mostly administered by the parish priest, who would also record them. In those cases in which sacraments were administered by another priest, or by the Guardian,Footnote 52 the recording is often followed by the sentence ‘in absentia parochi’ or by a note stating that the parish priest was ill.Footnote 53 In many cases, records also specify that the priest in question had been authorised by the parish priest, and sometimes the records are signed by the latter.Footnote 54 This is remarkable, because up until 1672 authorisations had been given by the Guardian. The definition of the role of the parish priest went hand in hand with a growing formalisation of the recording procedure. Not only did records become more and more standardised and complete: whereas earlier recordings had been filed at a later stage, after the 1670s, in line with the prescription of the Council of Trent, sacraments were registered and signed by the parish priest immediately after administration.

In this first century of its existence, the life of the Bethlehem parish was also characterised by the difficult development of a Catholic community separated from the Orthodox one. In the wake of the confessionalisation processes in Europe, the implementation of confessional boundaries between the newly established Catholic community and the other Christian denominations soon became a priority for the Church of Rome. Nonetheless, it was not easy to accomplish in a context in which Catholic clergy did not have secular power, different denominations competed to gain followers, and sacramental sharing was a well-established practice.Footnote 55

Throughout the seventeenth century, Franciscans, along with other missionaries, struggled to discipline the behaviour of their flocks and to foster the development of a Catholic identity and sense of belonging: returns to one's former church and hidden conversions remained common, with new converts wavering between Catholicism and Orthodoxy.Footnote 56 These widespread practices were encouraged by the friars’ conflicts with the Orthodox religious authorities,Footnote 57 which were particularly harsh in Bethlehem, and by the new converts’ wish to avoid conflict with their former coreligionists. Moreover, despite Rome's protests, communicatio in sacris and mixed marriages were common practices well into the eighteenth century.Footnote 58 Did the features of the newly established parishes outlined here influence Catholic mobility? And if so, in what ways?

Elsewhere I have argued that the spread of Catholicism may initially have strengthened the existing migration flows from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, slowing down the development of a Catholic community in the former.Footnote 59 In fact, both Jerusalem parish records and Franciscan chronicles suggest that especially up to the 1660s the new Catholics moved to the Holy City in order to avoid ‘persecutions’ on the part of the former coreligionists. Such a picture, however, is enriched by the data extracted from the sacramental records of Bethlehem: these suggest that the characteristic features of the local parish life in this period also resulted in other forms of mobility, which were not necessarily permanent.

4. Mobility linked to the receipt of sacraments and the development of new poles of attraction

Parish books suggest that on occasion, in the first few decades, since the spread of Catholicism began, Catholics went to Jerusalem from other places to receive sacraments.

In the 1650s, a couple who lived in Ramla, Deodato filius AbrahamFootnote 60 and his wife Maria, went twice to Jerusalem to baptise their children; in the same period, another couple from the town did the same.Footnote 61 Ramla was located on the road between the harbor town of Jaffa and Jerusalem, at a distance of 38 km from the latter. The local Franciscan house usually hosted pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. In the seventeenth century, the village was inhabited by a small French merchant community,Footnote 62 and, according to Franciscan sources, by Maronite Catholics.Footnote 63

Catholics from Nazareth, too, undertook the journey to Jerusalem (over a hundred kilometers) to receive the sacraments. This is the case with Beniamino f. Giamino, the dragoman of the local Franciscan convent, who had his daughter Tecla baptised in Jerusalem.Footnote 64 In some cases, the trip to Jerusalem may have been necessary because of the lack of a baptismal font. This, however, was not always the case. The first baptism recorded in Bethlehem dates back to 1619, but in the following decades, the children of some couples who lived in Bethlehem were baptised in Jerusalem. I have already mentioned Joseph, the son of the ‘Doctor’, and his wife, who in 1647 had their daughter Helena baptised in Jerusalem, though the same record attests that they were inhabitants of Bethlehem. In 1637, to give another example, Nicholas, the firstborn of Thomas son of Musa and Cara from Bethlehem, was baptised in Jerusalem.Footnote 65 A second daughter of the couple would later be baptised in Bethlehem.Footnote 66 In 1656, the baptism of Philippus son of Michael and Helena, both living in Bethlehem, is recorded in the books of the village but, according to the book, it was administered in Jerusalem by the Guardian of the St. Saviour's convent, Mariano Morone da Maleo.Footnote 67 The reasons why these baptisms were celebrated in Jerusalem may be varied: a short-term migration, the temporary absence of the parish priest or a special celebration in the Holy City. However, it seems no coincidence that such cases were more common before the 1670s, in a phase when parish life was not yet fully organised, with borders between parishes not clearly defined and a lack of appointed parish priests. Accordingly, with the passing of time, such occurrences became less common.

Another reason that might explain why the inhabitants of Bethlehem went to Jerusalem to receive sacraments may be the already-mentioned hostility of the Orthodox religious authorities and the atmosphere of semi-secrecy that characterised the first decades of parish life in Bethlehem. This hypothesis is corroborated by marriage records. In 1646 Maria f. Giorgio, known as Barbon, and Joseph Marangone f. Giob, an Orthodox who was secretly Catholic, got married in Jerusalem, though they were both from Bethlehem.Footnote 68 In 1672, to take another example, Demetri f. Salomone from Bethlehem and Caterina f. Aaiax, from Bayt Saḥūr, ‘belonging to the Greek nation’, got married in Jerusalem.Footnote 69 The reason for these couples’ decision not to marry in their native parish of Bethlehem may have been to do with the spouses’ (formal) affiliation to the Greek Orthodox community. During the seventeenth century, despite the ban imposed by the Roman Congregations, mixed marriages were sometimes tolerated by the Franciscans and other missionaries as a necessary evil. However, they were strongly opposed by the Orthodox religious authorities. Consistent with this opposition, the entry recording the above-mentioned wedding of Demetri and Caterina explains that even though the bans had already been made in June, the wedding had to be postponed to avoid the ‘mutterings of the Greeks’.Footnote 70 In 1673, the nuptials of Giorgio f. Elias with the newly converted Anna, to take another example, took place in Bethlehem, but without bans and in a private house, ‘to avoid scandal’.Footnote 71

The data analysed so far suggest that between the 1620s and the 1670s, the characteristic features of the first phase of the development of a parish system pushed many Catholics to move within Palestine to receive the sacraments. Whether to avoid conflicts with the Orthodox community or because of a loose parish organisation, Catholics from Ramla, Nazareth and Bethlehem went to Jerusalem to get married and to baptise their children, with the Holy City having a central role as a sacramental centre. Contrary to the urbanisation processes described by previous historiography, due to its temporary nature such a form of mobility did not threaten the development of local Catholicism. On the contrary, by allowing the administration of sacraments by a Catholic priest, it helped the growth of a local community separated from the Orthodox one, strengthened confessional identity and encouraged the development of a sense of belonging. In this sense, therefore, this local mobility performed the same function that confessional migration, and the very notion of exile, had in post-Reformation Europe.Footnote 72

The link between Catholics’ movements and the development of a parish system is confirmed by an analysis of how mobility patterns changed in the following decades. Towards the end of the century, the number of Catholics who moved to get married or baptise their children did not diminish, but mobility patterns altered. The importance of Jerusalem as a sacramental centre seems to have decreased, consistent with the increasing organisation of parish life in some places, such as Bethlehem. Further changes resulted from the establishment of new Catholic communities.

Following the spread of Catholicism in Bayt Jālā and Bayt Saḥūr, Catholics from these places begin to appear in the registers of the parish of Bethlehem, where they went to receive the sacraments. The first baptism of a child whose parents lived in Bayt Saḥūr, a little girl, Salayha f. Naslaha, daughter of Masleh f. Nazar and Catherina f. Salem, occurred in 1683.Footnote 73 In the following decade, the 1690s, 12 children of couples living in Bayt Saḥūr were baptised in Bethlehem. In December 1691, the parish priest of Bethlehem baptised three children from three different couples all living in Bayt Saḥūr – Maria f. Ganem, Servus Christi f. Nazar, Issa f. Mansur. Less than a year later, in April 1692, the children of two more couples from the village were baptised in Bethlehem on the same day.Footnote 74 Couples from Bayt Jālā, too, baptised their children in Bethlehem. The first instance occurred in 1676: it is the baptism of the twins Dominicus and Franciscus, sons of Khalil and Helena, inhabitans (degentes) of ‘Botticella’.Footnote 75 More baptisms of children of Bayt Jālā followed.Footnote 76 Records of burials of inhabitants of these two villages also appear in the Bethlehem books: one, for instance, follows the death of a 10-month old girl from Bayt Saḥūr, in 1683.Footnote 77 In all these instances, records correctly state that the Catholics belonged to the parish of Bethlehem, while specifying that they were living in Bayt Saḥūr or Bayt Jālā.

This small-scale analysis reveals the existence of a remarkable level of mobility within the area around Bethlehem, resulting from the spread of Catholicism. It also suggests that in seventeenth-century Palestine the diffusion of Catholicism facilitated the birth of new poles of attraction, in this case Bethlehem, to which Catholic mobility from the neighbouring area was directed. The importance of Bethlehem as a sacramental centre is also testified to by the presence in the town's sacramental books of entries recording the baptisms of children of ʿAyn Kārim. A first entry of the Liber baptizatorum mentions the baptism of Johanes f. Zacharia, born in April 1681. The date of the baptism is not reported, and the record is not signed.Footnote 78 A few years later, another entry mentions the baptism of Johannes f. Michael, administered in 1684 in ʿAyn Kārim by the Guardian of the local convent.Footnote 79 Besides confirming the importance acquired by Bethlehem as a sacramental centre, these entries raise questions about the position of ʿAyn Kārim within the Catholic ecclesiastical organisation and its link with the parish of Bethlehem. Previous scholarship suggested that the parish in ʿAyn Kārim had already been established in 1674; nonetheless, the baptism records rather seem to suggest that in the 1680s, the Catholic community of ʿAyn Kārim depended on the parish of Bethlehem, as was the case with Bayt Saḥūr and Bayt Jālā. This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that the second record mentioned was signed by the Bethlehem parish priest, Michael Rure.Footnote 80

Such a complex situation may have resulted from the very origin of the Catholic community of ʿAyn Kārim. According to the Franciscan accounts, the establishment of the local convent (1676) was followed in 1681 by the arrival of four dragomans with their families, all from Bethlehem. Apparently, their migration was mediated by the intervention of the friars, who experienced difficulties in persuading them to move.Footnote 81 Dragomans were very important figures in Franciscans’ lives in the Middle East. They were the convents’ interpreters and gate-keepers, and they fulfilled many additional functions. In ʿAyn Kārim, besides serving the friars, the newly arrived dragomans and their families also constituted the first nucleus of a local Catholic community. The Bethlehemite origin of the inhabitants of ʿAyn Kārim and the ties with the hometown might explain their presence in the sacramental registers of Bethlehem.

Whereas the inhabitants of Bayt Saḥūr and Bayt Jālā would depend on the parish of Bethlehem for a long time, the parish of ʿAyn Kārim would be fully functional already by the beginning of the eighteenth century. Despite the differences, all these cases strongly suggest that the funding of new Catholic communities led to new patterns of mobility. Research on early modern migration has already shown that migration patterns changed over time and were influenced by numerous factors.Footnote 82 In seventeenth-century Palestine – the evidence suggests – the geography of Catholics’ mobility was shaped by the interaction of the increasing strength of parish organisation on the one hand, and the establishment of new Catholic communities on the other. Whereas towards the 1670s the progress of parish organisation decreased Catholics’ movement towards Jerusalem, the spread of Catholicism in the same period brought about new geographical patterns in the direction of Bethlehem. These findings are confirmed by the analysis of another form of migration revealed by sacramental registers: marriage mobility.

5. Mobility and marriage

Barbara was not the only daughter of Beniamin from Nazareth who married someone from Bethlehem. Her sister Maria, too, married a man from Bethlehem, Musa f. Isa, dragoman of the local convent.Footnote 83 Like her sister, after the wedding, Maria moved to her husband's hometown. She appears in the local sacramental registers first as godmother in 1658,Footnote 84 and again in 1659 for the baptism of her daughter Anna.Footnote 85

European parish books have been amply used to study village exogamy.Footnote 86 Although in-village marriages were generally preferred, marrying outside the village community could be necessary because of narrow marital markets. According to Matthijs Kalmijn, the size of the community, the extent of multiple group affiliation among individuals and the degree of residential segregation played a critical role in determining the opportunities available to prospective brides and grooms.Footnote 87 As for the Ottoman Empire, scholarship on marital preferences and on marriage-related geographical mobility is thin. Existing works suggest a preference for marriages between cousinsFootnote 88 and proximity among the involved families in terms of shared living spaces, culture, class identity and religion.Footnote 89 Nonetheless, exogamous marriages were very common among both the Muslim population and Orthodox Christians. Among the latter, they were encouraged by the rules prohibiting marriages between cousins up to the seventh degree.

As to the newly established Catholic communities in Palestine, the Catholic Church was less strict than the Orthodox ones on this matter, allowing as it did marriage from the fifth degree of consanguinity upwards. However, Rome's opposition to interdenominational marriages made the search for a suitable partner in small communities difficult. Other factors to be considered were the preferences regarding social status and the extent of family ties between the community's members. With regard specifically to Bethlehem, the difficulty in finding a suitable Catholic wife was lamented by the Custos in a letter to Propaganda Fide advocating a more forbearing attitude toward mixed marriages.Footnote 90 Consistently, such marriages are frequently mentioned in Bethlehem's sacramental records.Footnote 91 Even more common were requests for dispensation from the impediment of consanguinity or affinity. According to the Liber Coniugatorum, dispensations were awarded in 36.8 per cent (28 out of 76) of the total number of marriages celebrated in the town between 1672 and 1669 (see Figure 4).Footnote 92 They were granted by the Custos and were usually for a third and fourth degree of consanguinity, and sometimes for more than one side of the family. Finally, some of the inhabitants of Bethlehem married outside the town.

Figure 4. Percentage of dispensations, mixed and out-of-town marriages in Bethlehem (1669–1699).

Like in Europe, out-of-village marriages were celebrated in the bride's parish, but then the couple moved to the groom's.Footnote 93 In 1663, for example, Andrea f. Franciscus from Bethlehem married Elena f. Iamino from Jerusalem.Footnote 94 The wedding was celebrated in the city, but was recorded in Bethlehem, where the couple settled afterwards and had their first son baptised.Footnote 95 More common, according to the records, were marriages between men from Bethlehem and women from Nazareth, where the development of the Catholic community was much slower than in Bethlehem or Jerusalem, and therefore the chances of finding a suitable partner lower. I have already mentioned the case of the sisters Maria and Barbara. In 1663 Giorgio f. Giorgio from Bethlehem married Nassaria from Nazareth, and in 1665 David married Hana f. Michael ‘ex civitate Nazareth’.Footnote 96 In 1665 Maria and Catherina, both from Bethlehem, married two men from Nazareth, Jacob f. Musa and Ebrahim f. Michael.Footnote 97

With Catholicism spreading around Bethlehem during the 1670s and 1680s, Bethlehemite men would frequently marry women from the neighbouring Bayt Saḥūr and Bayt Jālā, both much closer than Nazareth. I have already mentioned the marriage of Demetrius f. Salomon and the newly converted Caterina from Bayt Saḥūr, which was celebrated in Jerusalem in 1672.Footnote 98 To take another instance, in 1694, another convert from the same village, Maria f. Salem, married a man from Bethlehem.Footnote 99 Women from Bethlehem, too, married men from neighbouring places, though instances are less numerous: in 1677, for example, Hanna f. Salomon married Michel f. Issa from Bayt Jālā.Footnote 100 The Registrum Coniugatorum also records marriages between the inhabitants of Bethlehem, and its surroundings, and ʿAyn Kārim. In 1700, Francesco, alias Razggi, f. Giorgio from Bayt Jālā married Elisabetta f. Chalil Macaron from ʿAyn Kārim, where the marriage was celebrated.Footnote 101 Other marriages between Catholics living in ʿAyn Kārim and those of the Bethlehem cluster would follow in the upcoming years, confirming the tight ties between the two Catholic communities.Footnote 102

In a context of competing religions and building of confessional identities, in most cases, out-of-village marriages allowed individuals to find a partner of the same denomination and therefore to avoid mixed marriages. This, however, was not always the case, as according to the Registrum Coniugatorum, not all the spouses from Bayt Jālā and Bayt Saḥūr were Catholic. This may have been the case because, due to the conflicts between the Catholics and the Greek Orthodox community of Bethlehem, mixed marriages were easier if celebrated out of town.

When seen in the framework of previous research on Christian mobility, an analysis of marriage mobility as reported by Bethlehem sacramental registers sheds light on previously unknown forms of mobility between non-urban centres. It also confirms the existence of an intense level of movement within the Bethlehem area. In the context of the ongoing development of Catholic communities in the area, out-of-village marriages were encouraged by the communities’ small numbers and – in the case of out-of-village mixed marriages – by the conflicts with the Greek Orthodox community. At any rate, whether mixed or not, these nuptials contributed to strengthening the Catholic presence in Bayt Jālā and Bayt Saḥūr, especially when they involved Catholic women from Bethlehem, who would move to the husband's hometown.

The data on marriage mobility also confirm what has been said about the change in mobility patterns during the century under consideration. The lack of evidence of marriages between the inhabitants of Bethlehem and Nazareth from the 1670s onwards strongly suggests that such marriages may have been affected by the spread of Catholicism in Bayt Saḥūr and Bayt Jālā. Since Nazareth was 120 km from Bethlehem, it is possible that, given the choice, the inhabitants of Bethlehem were keener to marry within a short distance from their hometown. This would also be consistent with the findings of studies on early modern Europe, according to which most exogamous marriages involved short-distance mobility, that is within 20 km.Footnote 103 However, the presence in the Bethlehem registers of the inhabitants of ʿAyn Kārim, which was closer to Jerusalem than to Bethlehem, reminds us that geographical distance was only one of the factors that shaped geographical mobility, whether to receive sacraments or to find a suitable partner. In fact, the consistent presence of the inhabitants of ʿAyn Kārim in the sacramental records of Bethlehem suggests that mobility patterns also reflect the strength of the network of ties between Catholic communities.

What role did the Franciscans play in the shaping of this geography of Catholic mobility? The arrival in the village of ʿAyn Kārim of dragomans who had been prompted by the friars is not the only case in which Franciscans encouraged and directed the movement of dragomans at a regional and local level. In the 1620s a dragoman from Aleppo was employed at the convent of St. Saviour in Jerusalem. According to the Chronicles, in 1621, the Guardian had turned to the consul of Aleppo for a good interpreter; as a result, Battista was sent to Jerusalem.Footnote 104 Such cases contribute to defining the role played by Franciscans in shaping internal mobility. They also tally with numerous items of evidence concerning friars encouraging converts’ migration from Bethlehem towards Jerusalem, and even across the Mediterranean, in order to avoid returns to the former faith.Footnote 105 In other instances, the friars’ role may have been less direct, for example, that of organising an out-of-village marriage. In any case, mobility seems to have been one of the means by which the friars fostered the development of local Catholicism.

6. Concluding remarks

Starting from an analysis of data extracted from the parish records of Bethlehem, this research has reconstructed Catholics’ movements between villages in seventeenth-century Palestine. As well as revealing previously unknown forms of local mobility, this small-scale analysis has also enriched and questioned well-established historiography on Catholic and Christian geographical mobility in the Middle East and has addressed from a local perspective wider historical events, thus contributing to scholarly debates on the effects of the Protestant and Catholic Reformations outside Europe and on the plurality of early modern Catholicism.

In the context of existing scholarship on Christian mobility, firstly, the data gathered here reveal the existence – alongside traditional long-term household mobility – of short-term movements undertaken to receive the sacraments and to be wed; secondly, from a geographical point of view, they question the centrality of Jerusalem, revealing a substantial level of movement between Palestinian villages and towns. Some of these movements are attested within the Bethlehem cluster, others between Bethlehem and places located further afield, such as ʿAyn Kārim and Nazareth. These forms of mobility, this article has suggested, are tightly related to the ongoing consolidation of a Catholic minority and the development of a Catholic identity and sacramental system, separated from the Orthodox one. Members of small developing communities with a still embryonic parish system moved to receive the sacraments, to avoid conflicts with former co-religionists, and to find a suitable partner. The close relationship between geographical mobility and the spreading and consolidation of religious communities is also confirmed by the changes in mobility patterns. Towards the 1670s, the strengthening of parish organisation reduced the number of people who moved to Jerusalem from Bethlehem and Nazareth to receive the sacraments. These forms of mobility did not disappear, but from the 1670s onwards the greater geographical diffusion of Catholicism added further complexity to the geography of Catholics’ mobility, stemming from the development of other sacramental centres. This is the case with Bethlehem, where people went to receive sacraments both from the neighbouring villages of Bayt Jālā and Bayt Saḥūr and from ʿAyn Kārim (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Catholic mobility between towns and villages in the district of Jerusalem (1670s–1700).

In the following centuries, this process would continue, consistent with the progress of the diffusion of Catholicism. From the 1680s on, the data suggest that the development of new communities led to an increase in short-distance mobility, because long-distance travel was no longer necessary either to find a Catholic partner or to receive sacraments. Concerning marital behaviour, for example, the spread of Catholicism towards Bayt Jālā and Bayt Saḥūr probably contributed to the decreased number of marriages contracted between the inhabitants of Bethlehem and those of faraway Nazareth. Alongside distance, other factors that may have influenced geographical mobility were the ties between communities and the role played by the friars as facilitators of inter-parish mobility. In this respect, the case of ʿAyn Kārim is a conspicuous example, but it is very likely that the friars also shaped the mobility related to the administration of sacraments and played a role in arranging out-of-village marriages. By doing so, and more generally by directing the movement of their followers, the friars facilitated both the spread of Catholicism and the growth of local communities, as well as the development of a local form of Catholicism. In fact, this analysis suggests that while the movements to receive the sacraments and marriage mobility in semirural Palestine were a consequence of the ongoing strengthening of confessional borders between Christian denominations, they also contributed to the development of a Catholic identity and sense of belonging. They did so by lowering the occurrence of mixed marriages, the recourse to non-Catholic priests to administer the sacraments, and therefore sacramental sharing. In so doing, therefore, they contributed to the creation of confessional boundaries.

Set as it is in an ampler range of historiographical inquiries on early modern Catholicism outside Europe, this research strongly suggests that the characteristics of the local context not only shaped the local ecclesiastical organisation but also influenced the relationship between the strengthening of confessional identities and geographical mobility. In fact, in Palestine movements between towns and villages seem to be a local variation of confessional migration, as described by works on post-reformation Europe. In this respect, this research also enriches a historiography mostly concerned with long-distance migration by emphasising the role played by local mobility in processes of confession- and community-building. Finally, from a methodological standpoint, the article shows the importance of microanalysis and of focusing on a small area in understanding geographical mobility associated with religious practices and allegiances.