Introduction

It has long been argued that retirement should not be viewed as a single, permanent event but as a process (Atchley Reference Atchley1982). Retirement transitions are diverse, lengthy and fuzzy, and can be marked by interruptions (Kohli and Rein Reference Kohli, Rein, Kohli, Rein, Guillemard and van Gunsteren1991). A small body of work has explored retirement reversals, or ‘unretirement’, commonly defined as a specific sort of bridge job in which individuals return to paid work following cessation of labour force participation at retirement (Beehr and Bennett Reference Beehr and Bennett2015; Maestas Reference Maestas2010). Studying retirement reversals provides a fuller understanding of the late career as well as of potential inequalities occurring at this life stage. Much of our knowledge about unretirement originates from the United States of America (USA), supplemented by studies scattered throughout Western Europe and from Canada. This literature examines unretirement using varying definitions and methodological approaches, making it difficult to compare studies. Nevertheless, a picture is emerging of the nature of unretirement and the processes driving it.

This paper contributes to that burgeoning literature by demonstrating the scale and nature of the phenomenon for women and men in the United Kingdom (UK) for the first time, as well as examining who is most likely to unretire. In particular, we ask whether unretirement is a strategy used by the financially precarious to raise their incomes, and, if not, what might be the implications of unretirement for income inequalities in later life in the UK.

Unretirement: what is known?

Unretirement jobs, like other bridge jobs, have been conceptualised as lying in the middle ground between employment and retirement (Hardy Reference Hardy1991). However, unretirement is distinctive in that there is a gap between jobs rather than a smooth transition from one job to another (Maestas Reference Maestas2010). The gap might appear where individuals have to change employers in order to comply with occupational pension or early retirement rules, because they were otherwise unable to reduce their hours, or because they experienced involuntary retirement (Business in the Community, International Longevity Centre and The Prince's Initiative for Mature Enterprise (BIC, ILC-UK and PRIME) 2014; Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015). Those who unretire may have been unable or did not wish to co-ordinate ending one job with immediately starting the next, but did subsequently return to paid work. People can retire both before and after the state pension age in any particular context; similarly, unretirement is not limited to taking place after the age of eligibility for state pensions.

Rates of unretirement

Returns to work following retirement are common, at least in the USA where most research has taken place (Pettersson Reference Pettersson2014). A recent estimate found that at least 26 per cent of American retirees subsequently unretired over a six-year period since retiring (Maestas Reference Maestas2010). However, study designs in the few European countries where unretirement has been studied (largely Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK) are so diverse that it is not possible to compare unretirement rates.

Concerning the UK, a study of ill-health retirement from the National Health Service reported that 13 per cent of retired employees had taken up paid work within one year (Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams Reference Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams2004). However, this study is of a highly specific population and is not generalisable to the UK population as a whole. Another study of men living in England, using the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, reported a very low unretirement rate of 5 per cent (Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015). However, rather than using an inflow sample, in which people are followed from the moment they enter the retired state, this study employed a stock sample of currently retired people with retrospectively reported retirement dates and determined the proportion of the sample which exhibited unretirement behaviour. There is currently no evidence concerning the frequency of unretirement for the UK as a whole, or for women. Therefore, our first research question is:

• How common is unretirement among retired men and women in the UK?

Predictors of unretirement

In studies from North America and Europe, individuals consistently report diverse motivations for post-retirement employment. Respondents frequently indicate that improving their finances is a primary or important motivation for unretiring (Hardy Reference Hardy1991; Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams Reference Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams2004; Schellenberg, Turcotte and Ram Reference Schellenberg, Turcotte and Ram2005). In addition, financial difficulties/problems are also critical, as is the loss of social contact or daily rhythm upon retiring from paid work (Jonsson and Andersson Reference Jonsson and Andersson1999; Jonsson, Josephsson and Kielhofner Reference Jonsson, Josephsson and Kielhofner2000). Lifestyle factors are also often mentioned by unretiring individuals, such as not enjoying retirement, appreciating the intrinsic aspects of work and having been asked by others to help out (Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams Reference Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams2004; Schellenberg, Turcotte and Ram Reference Schellenberg, Turcotte and Ram2005). In terms of role enhancement theory, which takes the perspective that individuals experience benefits by holding multiple social roles, unretiring may enable individuals to maintain a rewarding work role (Sieber Reference Sieber1974). Retirement reversals are less frequent in the USA among individuals who have secure health insurance, have reached the eligibility age for full social security benefits or have an employment pension (Congdon-Hohman Reference Congdon-Hohman2009; Kail Reference Kail2012; Kail and Warner Reference Kail and Warner2013; Lin Reference Lin2005; Pleau Reference Pleau2010).

Unretirement may represent a means for older people on small pensions, perhaps as a result of interrupted work histories, to achieve a decent income in old age. However, although people often cite financial motivations for unretiring, the evidence from available North American and European studies, including the UK, concerning whether retirees with poorer finances are actually more likely to unretire is equivocal (Fasbender et al. Reference Fasbender, Wang, Voltmer and Deller2016; Han and Moen Reference Han and Moen1999; Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015; Larsen and Pedersen Reference Larsen and Pedersen2013; Maestas Reference Maestas2010; McDonald Reference McDonald1997; Meghir and Whitehouse Reference Meghir and Whitehouse1997). One reason for inconsistencies may be that the category of those who remain retired contains two contrasting groups: individuals who wish to remain retired and those who sought but failed to find post-retirement employment. Hardy (Reference Hardy1991) distinguished these two groups in a study set in Florida, observing that individuals who had wanted to but had been unable to return to work were in a worse financial position than retirees who did not wish to unretire.

Having poorer finances in later life is associated with certain characteristics, such as lower educational qualifications or poor physical health, that make finding a suitable new job more difficult (Larsen and Pedersen Reference Larsen and Pedersen2013; Pettersson Reference Pettersson2014). This may explain why a study examining unretirement in male participants from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing found no relationship between having an inadequate income and unretiring (Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015). Although not looking at unretirement per se, another English study found that those in the lowest wealth quintile were least likely to be in paid work after age 65, an effect which disappeared after controlling for factors which included education and health (Lain Reference Lain and Scherger2015). This result suggests that the poor health and low education levels of those with least wealth may be obstacles to finding paid work in later life. Higher aggregate unemployment has been associated with lower unretirement rates in British men (Meghir and Whitehouse Reference Meghir and Whitehouse1997), which is not surprising in light of the known obstacles facing British older people seeking paid work, such as age discrimination, caring responsibilities or poor physical health (BIC, ILC-UK and PRIME 2014). In addition, if retirees expect to receive only low earnings from their labour, paid work may not be such an attractive prospect, and individuals may prefer to pay the financial penalty of not working rather than experience the constraints of low-paid work (Loretto and Vickerstaff Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2013; Meghir and Whitehouse Reference Meghir and Whitehouse1997).

Factors affecting individuals’ possibilities of finding post-retirement employment are often those which affect whether they are able to find paid work throughout their lives (Hardy Reference Hardy1991). Studies from North America and several European countries, including Denmark, Sweden and the UK, have found consistent relationships between participants’ unretirement behaviour and their gender, age, education level and health status (Cahill, Giandrea and Quinn Reference Cahill, Giandrea and Quinn2015; Fasbender et al. Reference Fasbender, Wang, Voltmer and Deller2016; Griffin and Hesketh Reference Griffin and Hesketh2008; Han and Moen Reference Han and Moen1999; Kail and Warner Reference Kail and Warner2013; Larsen and Pedersen Reference Larsen and Pedersen2013; Lin Reference Lin2005; McDonald Reference McDonald1997; Pettersson Reference Pettersson2014; Pleau Reference Pleau2010; Warner et al. Reference Warner, Hayward and Hardy2010). Specifically, men are more likely to unretire than women, as are individuals who retired at younger ages, are in better health and have more qualifications. Similar results were obtained in the very few UK studies of unretirement; however, the results of one were based on a sample of former national health-care employees (Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams Reference Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams2004) – and, thus, are not generalisable – and the other two studies only included men (Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015; Meghir and Whitehouse Reference Meghir and Whitehouse1997).

Concerning non-financial factors, providing informal care to an elderly, ill or disabled person may be a barrier to taking up paid work following retirement. One possible mechanism might be role strain, in which individuals’ overall role obligations from combining informal care-giving and paid work are perceived as too onerous (Goode Reference Goode1960). Another might be lack of bridging/linking social capital necessary to learn about job opportunities as a result of care-giving limiting individuals to a smaller range of close social contacts (Gonzales and Nowell Reference Gonzales and Nowell2016). Using US data, Pleau (Reference Pleau2010) did not find evidence of competing effects of informal care-giving on rates of return to work following retirement, while Dingemans (Reference Dingemans2016) only found associations in men of care-giving with lower unretirement rates in analyses using data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Another non-financial factor is that spouses may wish to co-ordinate their activities. The decision to unretire is not necessarily taken at an individual level (Loretto and Vickerstaff Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2013): the retired are more likely to take up paid work if their partners are in continuous employment or recently began working (Chandler and Tetlow Reference Chandler and Tetlow2014; Hayward, Hardy and Liu Reference Hayward, Hardy and Liu1994; Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015).

In summary, little is known about the factors which predict unretirement in the UK and, in particular, whether individuals with poor finances are more or less likely to unretire. While one motivation for unretirement behaviour may be financial need, it is possible that those individuals who are most concerned about their finances are not able to find paid work. Since poorer incomes in later life are associated with lower educational qualifications and ill-health over the lifecourse, it is plausible that employment barriers are substantial for those in greatest need of a job (Scherger Reference Scherger and Scherger2015). We anticipate that advantaged retirees will be more likely to reverse their retirement, specifically those who are more qualified and in better health, those with higher pre-retirement earnings and with better subjective finances. Consequently, our research also asks:

• Which factors predict retirement reversals in the UK? In particular, are more advantaged retirees more likely to reverse their retirement?

Gender and unretirement

Not only do women unretire less often than men (Maestas Reference Maestas2010), the factors affecting unretirement may be gendered in that they affect women's and men's unretirement behaviour differently. Concerning marital status, studies in the USA and Denmark suggest that women are more likely to unretire if they are unmarried (Larsen and Pedersen Reference Larsen and Pedersen2013; Lin Reference Lin2005; Pleau Reference Pleau2010). This may be related to economic necessity, particularly for those who divorced or separated at older ages (Hardy Reference Hardy1991; Pleau Reference Pleau2010).

The impacts of financial factors may also be gendered. Studies in the USA and Canada found that high-earning women were more likely to unretire, even though this was not the case for men (McDonald Reference McDonald1997; Pleau Reference Pleau2010). The issue of low earnings from jobs may be particularly pertinent for women: US research has shown that men are more likely to take up full-time post-retirement jobs and women part-time post-retirement jobs, reproducing patterns from earlier in life (Kail and Warner Reference Kail and Warner2013). The associated lower wages from part-time working may reduce the incentive for women to unretire, especially those who received low salaries in their last job, and a more attractive option for partnered women may be to rely on pension benefits derived from a spouse (Finch Reference Finch2014).

To our knowledge, there are no studies examining gender differences in unretirement in the UK. However, variations in unretirement rates are likely, partly as a result of gendered differences in pension provision in later life. For example, a British study showed that, while there was no difference according to marital status for men, never-married women were more likely than their married or formerly married counterparts to have an occupational or personal pension in addition to the state pension (Arber and Ginn Reference Arber and Ginn2004). This difference was partially explained by fewer years spent in the labour market on the part of married/formerly married women, most likely a result of family constraints on their labour market activities. Therefore, our last research question is:

• Do individual characteristics, particularly marital status and financial adequacy, affect men's and women's unretirement behaviour differently?

The UK context

Most research into unretirement has taken place in the USA and continental European countries. However, the UK has a distinctive social policy, legislative and labour market setting that may generate specificities in both the frequency and nature of unretirement (Loretto and Vickerstaff Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2013). Here we outline aspects of the UK context relevant to the period under study of 1991–2015 and the generations born during 1920–1959.

Until 2010, the state pension age in the UK was 60 years for women and 65 years for men. Pensions Acts in 1995 and 2011 have aimed to equivalise gradually women's pension ages to those of men's and to advance pension ages for both genders, but these changes only affect generations born since 1949 (cf. Loretto and Vickerstaff Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2013). Many Britons additionally have occupational pensions and/or private pensions, which are highly diverse in their rules and often allowed members to retire and claim their pensions when they were still in their fifties (Meghir and Whitehouse Reference Meghir and Whitehouse1997; Thurley Reference Thurley2011). Concerning rights to combine paid work with pensions, since 1989, all those above state pension age have had the possibility of working and simultaneously receiving a full state pension, while being taxed on the total income at a rate similar to that of the general working-age population (Disney and Smith Reference Disney and Smith2002; Whitehouse Reference Whitehouse1990). It is only since 2006, however, that those who are eligible have been able to claim occupational pensions whilst still working for the sponsoring employer (Taylor Reference Taylor and Taylor2008). Prior to that, people had to retire in order to claim their occupational pension, even if they had reached pensionable age.

Age discrimination legislation in the UK is weak, which affects possibilities for older workers to remain in and find paid work. For most of the period under study, almost all legislated employment protections ceased after age 65 (Lain Reference Lain2011), although recent age discrimination legislation passed in 2006 and strengthened in 2011 now protects British workers against mandatory retirement ages (Lain Reference Lain and Scherger2015).

Levels of joblessness among Britons aged between 50 and state pension age are relatively high in comparison with other age groups; moreover, unemployment rates in this age group increased during economic downturns in the early 1990s and late 2000s (BIC, ILC-UK and PRIME 2014). Much joblessness is involuntary: one-quarter of jobless older workers would like to have paid work. For those in jobs, over-employment, in which employees preferring to work shorter hours are unable to do so, is reported by nearly 40 per cent of those in their late fifties (BIC, ILC-UK and PRIME 2014). Without flexibility to reduce their working hours, over-employed individuals may retire from work altogether, even though their preference would be to work part-time.

In short, much about the British context – particularly the possibilities for combining paid work with state and occupational pensions – may encourage unretirement. In addition, individuals unable to reduce their hours who subsequently retired from full-time jobs may be open to seeking part-time opportunities elsewhere. However, difficulties in finding work faced by older job-seekers in the UK, exacerbated by the weakness of age discrimination legislation, are likely to depress unretirement rates and limit possibilities for unretirement to the most employable.

Approach taken in this study

Employing an event analytic approach, our study describes the frequency of retirement reversals and how long participants take to unretire. Using a range of indicators which have been found to be important in previous studies, we explore the correlates of unretirement, paying particular attention to gender and financial adequacy.

The definition of unretirement used in our study depends on self-declarations of retirement status, which allows it to be distinguished, as far as possible, from disability and unemployment. With this approach, we aim to assess transitions into and out of retirement that have social meaning for the individual, rather than simply measuring labour market churning or periods of unemployment or inactivity (O'Rand and Henretta Reference O'Rand and Henretta1999: 116). Maestas (Reference Maestas2010) has argued that declarations of retiring coincide with behaviours that mark retirement as a major lifecycle event such as pension claiming, with the proviso that these self-evaluations may also track changes in how participants perceive their activities as well as actual changes in behaviour (Hayward, Hardy and Liu Reference Hayward, Hardy and Liu1994).

Methods

Data

This study uses data from all waves of the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), a multi-disciplinary, longitudinal study of individuals living in private households in the UK which began in 1991 (University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research and National Centre for Social Research 2010). In 2009, BHPS participants were recruited into Wave 2 of a larger household panel called Understanding Society and have been followed up to Wave 6, which is the most recent data release (University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, NatCen Social Research and Kantar Public 2016). Therefore, our study encompasses the period 1991–2015.

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the sample if they: (a) reported being in paid work for at least one wave after age 40; (b) subsequently retired between the ages of 50 and 69 years; and (c) gave information on their labour market status for at least one wave following the wave in which they retired. Therefore, participants included in the analysis provided at least three waves of data, but these did not have to be consecutive waves. We included men and women born between 1920 and 1959 since these cohorts were in their late fifties and/or sixties during part of the period under study. A total of 2,394 participants fulfilled these criteria; of these, 2,046 participants with complete information on covariates made up the main study sample.

Variables

Unretirement

Following Maestas (Reference Maestas2010), we define unretirement as a partial or full reversal of the retirement transition using participants’ self-reports of their labour market status and hours spent in paid work in a normal week. Participants were asked which economic activity best described their ‘current situation’ from: self-employed, in paid employment (full- or part-time), unemployed, retired from paid work altogether, on maternity leave, looking after the family or home, full-time student/at school, long-term sick or disabled, on a government training scheme or something else. Participants were classified as being in paid work if they reported self-employment or employment at the time of the survey. Those who worked for pay in the week preceding the interview or were temporarily away from their jobs were asked to indicate the number of hours they were expected to work in a normal week, excluding overtime and meal breaks. Participants who did not describe themselves as working full-time but indicated hours of work corresponding to 30 hours per week or more were reclassified as full-time workers.

Participants were designated as being fully retired if they reported being ‘retired from paid work altogether’ as their current situation and did not declare any hours of paid work in a typical week. Partial retirement, in contrast, was defined as reporting being retired and simultaneously working for less than 30 hours of paid work in a normal week.

We operationalise unretirement as an event that takes place if a participant: (a) reported being fully retired and recommenced full-time or part-time paid employment in a subsequent wave; or (b) began full-time work following partial retirement in a previous wave (Maestas Reference Maestas2010).

Covariates

The year of unretirement was recorded, in order to control for period effects in the fully adjusted models, since prior research has shown that higher unemployment rates are associated with lower unretirement rates, presumably by making jobs more difficult to find (Hayward, Hardy and Liu Reference Hayward, Hardy and Liu1994; Meghir and Whitehouse Reference Meghir and Whitehouse1997). Participants reported their year of birth, which was used to calculate their age-group at retirement as well as their birth decade. The highest academic educational level that participants ever reported achieving was reclassified into five categories corresponding to: no academic qualifications; CSE (Certificate of Secondary Education) or qualifications below GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education); O-Level, GCSE or equivalent; A-Level or equivalent post-16 qualification; and post-secondary academic qualifications (reference category).

Since research from the USA has found that unretirement often appears to be planned when in the pre-retirement job (Maestas Reference Maestas2010), we used information from participants’ final year in work for covariates indicating participants’ state of finances, health, marital status and informal care-giving. If this information was missing, data were imputed from the next most recent available year in paid work. We used four measures of finances. An equivalised measure of net household income was generated using the square root of household size as the equivalence scale (Levy and Jenkins Reference Levy and Jenkins2012; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development n.d.). Quintiles were generated for this variable at each survey wave, a procedure which adjusts for wave-to-wave inflation. Subjective financial status was measured by a question about difficulty in getting by; the variable was dichotomised into: (a) living comfortably or doing alright (reference category), and (b) just getting by or finding it difficult or very difficult. Housing tenure was recoded into three categories: owned outright (reference category), owned with a mortgage and rented (whether from the local authority, privately or from a housing association). Participants indicated whether they were a member of an occupational pension scheme. Because participants may have been working in bridge jobs in their late career, records of having an occupational pension in a previous job from age 45 were examined, and people reporting such pensions earlier were included in the category ‘membership of an occupational pension from a current or previous employer’. Self-rated health was reported in five categories in both surveys; however, Understanding Society and the 1999 wave of BHPS used different response categories to the other waves of BHPS. In order to harmonise the surveys, responses were dichotomised into: 1 = excellent, very good or good health (reference category) or 2 = fair, poor or very poor health. Whether the spouse or partner was in work was recorded in a five-category variable: married, spouse not in paid work (reference category); married, spouse in paid work; never married; divorced/separated; widowed. Participants indicated whether they were providing informal care-giving, whether within or outside the household, and the number of hours provided. This information was used to create a dichotomised variable of providing care for at least 20 hours per week, and providing less or no care.

Analytic plan

Following descriptive analyses, survival analysis of time to unretirement was performed. The survival analysis was carried out using Cox modelling in Stata 14.1. Because time is recorded annually, a process which generates ties, we used the Efron method for tied failures (Cleves et al. Reference Cleves, Gould, Gutierrez and Marchenko2010: 151).

In survival analytic approaches, also called event-history or duration analysis, time to unretirement for each individual is calculated from the beginning of the risk period, in our case starting from the first year that an individual was recorded as transitioning from paid work into retirement. For some individuals it was not possible to observe their transition into retirement, because they were already retired at the first time-point they were observed. Prior research from the USA and the Netherlands has shown that unretirement usually takes place rapidly following retirement if it takes place at all (Hayward, Hardy and Liu Reference Hayward, Hardy and Liu1994; Kail and Warner Reference Kail and Warner2013; Pleau Reference Pleau2010; Schuring et al. Reference Schuring, Robroek, Otten, Arts and Burdorf2013). Since the rate of unretiring is greatest soon after retiring, and unretirement can be followed by re-retirement, studies examining transition rates back into employment for individuals who have been retired for an unspecified, and possibly lengthy, period of time, will miss such unretirement transitions and report depressed unretirement rates. Following recommendations to eliminate such left-censoring (events occurring before follow-up begins) through appropriate study design (Singer and Willett Reference Singer and Willett2003: 319–20), retired individuals were set aside from the analysis if a transition from paid work into retirement was not observed (see the Data section). It is possible that certain individuals experience more than one retirement and unretirement event. Consequently, the first time that an individual was observed to retire was used, with the proviso that earlier retirement (and unretirement) events may not have taken place within the observation window.

Survival analysis has the advantage of handling non-informative right-censoring: when a participant was not observed for long enough for an unretirement event to be observed for reasons such as random loss to follow-up. Consequently, it is possible to include participants in the analysis who were followed for different lengths of time, as long as they were followed for at least one year after the paid work–retirement transition.

Results show how prevalent retirement reversals were among men and women, at what age they occurred and the shape of the hazard of unretirement. Subsequent analyses indicate the effects of predictors of unretirement transitions. Unadjusted and fully adjusted results for each of the socio-economic, health and demographic factors are presented. Because the period modelled extends to over two decades, non-linear period effects which could confound the analysis were added as power terms in the fully adjusted models.

Two sensitivity analyses were performed. Listwise deletion was used in the main analysis, a procedure which can generate bias if the data are not missing completely at random. Therefore, the first sensitivity analysis consisted of repeating the analyses described above in Mplus 7 using discrete time estimation with full information maximum likelihood estimation (see Table A1 in the online supplementary material). This approach uses all available data and requires the less-restrictive assumption that the data are missing at random (Muthén and Muthén Reference Muthén and Muthén2012). In case of differences in the effects of covariates on unretirement between men and women, interactions between gender and the potential predictors were examined in a second sensitivity analysis.

Results

Descriptive results

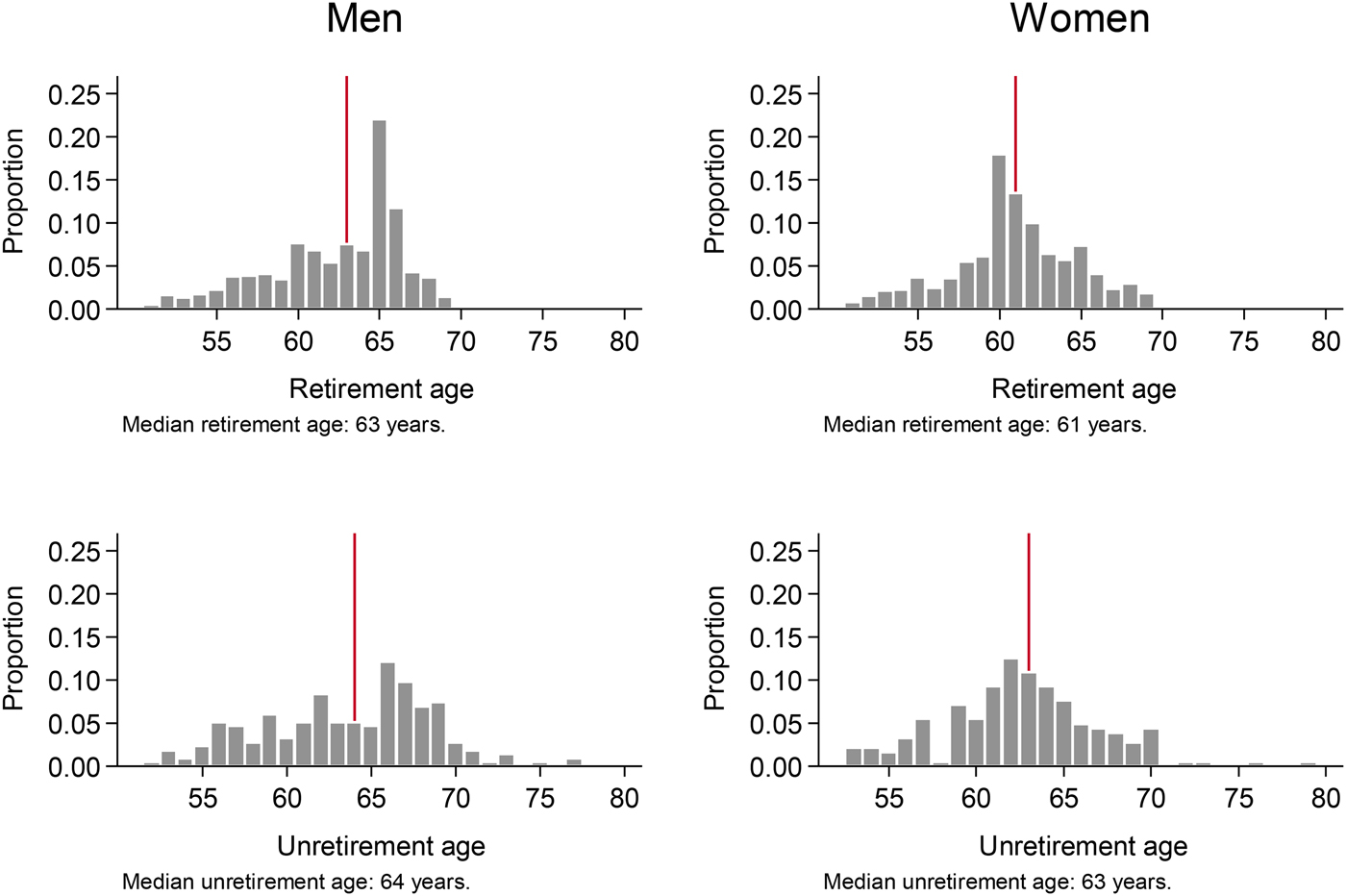

For these cohorts born between 1920 and 1959, for whom a transition from paid work into retirement was observed, the sample median retirement age was 62 years. Men had a modal retirement age of 65 years, the age of men's eligibility for the state pension (Figure 1), and a median retirement age of 63 years. The modal retirement age for women was 60 years, but women in this sample had a median retirement age of 61 years, later than the state pension age for most of the sample of 60 years.

Figure 1. Distribution of ages of retirement and unretirement for British Household Panel Survey participants born in 1920–1959.

Almost half of the sample had no academic qualifications (Table 1). In terms of their subjective financial situation, 75 per cent reported that they were ‘living comfortably’ or ‘doing alright’. While 58 per cent were mortgage-free home-owners, 27 per cent had a mortgage and 14 per cent were renting their home. Just over half were current or previous members of an occupational pension scheme, and most reported good or better health. About 80 per cent were partnered, with similar numbers having a working spouse as having a non-working spouse. About 5 per cent of participants were providing informal care for at least 20 hours per week.

Table 1. Description of the sample participants

Notes: N = 2,046. GCSE: General Certificate of Secondary Education. CSE: Certificate of Secondary Education. Source: Data from Waves 1–18 of the British Household Panel Survey, with participants followed into Waves 2–6 of Understanding Society (authors' calculations).

In total, 398 people were observed to reverse their retirement (215 men and 183 women). Around 9 per cent of retirees unretired within the first year of retiring and, after around 15 years of follow-up, the cumulative proportion who reversed their retirement was about 0.26 (Figure 2). The mean time to unretirement was 2.4 years and the hazard of experiencing a retirement reversal decreased rapidly over time, with few reversals after eight years and none observed after 15.

Figure 2. Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard of unretirement for British Household Panel Survey participants born in 1920–1959.

The median unretirement age was slightly higher than retirement age at 63 years (64 years for men and 63 years for women; Figure 1). Most retirement reversals among women took place after their state pension age.

Predictors of unretirement

Unadjusted and fully adjusted results from Cox modelling of time to unretirement are reported in Table 2. Men were 27 per cent more likely to return to paid work following retirement than women. After adjustment for the other covariates including measures of financial adequacy, education level, health, marital status and informal care-giving, the gender gap remained, indicating that these covariates do not account for the gender difference. Compared to those born in 1940–1949, those born in the subsequent decade were 50 per cent more likely to unretire. Since this association remained the same size after adjustment for other covariates including retirement age, it suggests the possibility of a cohort effect.

Table 2. Unadjusted and mutually adjusted models of unretirement in relation to selected covariates, British Household Panel Survey/Understanding Society

Notes: N = 2,046. CI: confidence interval. Ref.: reference category. GCSE: General Certificate of Secondary Education. CSE: Certificate of Secondary Education. 1. The fully adjusted estimates are additionally adjusted for period as a cubic function in order to account for non-linear period effects. Source: Data from Waves 1–18 of the British Household Panel Survey, with participants followed into Waves 2–6 of Understanding Society (authors' calculations).

There was a graded relationship between educational level and the hazard of unretirement in both the unadjusted and fully adjusted models. Specifically, participants without any qualifications were about 50 per cent less likely to unretire than participants with post-secondary level qualifications, even after controlling for income and subjective financial situation.

Turning to financial factors, perceptions of financial situation were not associated with variations in rates of return to work. Marginally significant differences suggest that those in the highest net equivalised income quintile were more likely to unretire compared to those in the lowest quintile (HR = 1.38, p = 0.056), an association which disappeared after full adjustment. However, housing tenure remained associated with unretirement even in the fully adjusted model, suggesting a role for financial necessity. For instance, those with mortgaged dwellings were 50 per cent more likely to unretire, compared to participants who owned their homes outright. In the fully adjusted model only, renters were more likely to unretire than home-owners (HR = 1.40, p = 0.041). Those who were not members of occupational pension schemes had lower unretirement rates than members (HR = 0.82, p = 0.049), an association which was absent from the fully adjusted model.

Individuals in excellent or good health were around 25 per cent more likely to return to paid work than those reporting fair, poor or very poor health. Compared to those with a partner not in paid work, participants whose partner worked or who had never married were more likely to unretire. Finally, provision of informal care for at least 20 hours per week was not associated with unretirement in either the unadjusted or fully adjusted models.

The first sensitivity analysis, which employed full information maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus in order to use all available data (N = 2,394), generated similar results (see Table A1 in the online supplementary material). In the second sensitivity analysis, no interactions between gender and each of the covariates were significant at the 95 per cent significance level (results not shown).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine unretirement in a general population sample from the UK and, as such, it contributes to a growing body of research examining the nature of labour force participation in later life. Employing survival analysis, we were able to show that retirement is not necessarily a stable state in the UK; to the contrary, a cumulative proportion of around one-quarter of participants in this general population sample who were observed retiring from paid work subsequently reversed their full or partial retirement over the next 15 years. Our approach shows the development of the hazard of unretirement in terms of time since retirement. We found that unretirement rates were highest among the recently retired, and declined over time to become inconsequential within ten years of leaving the labour force.

The rate of unretirement reported in the current paper – around 9 per cent unretiring after one year (cf. Figure 2) – lies in the middle of values obtained from previous studies. It is below the 13 per cent reported by Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams (Reference Pattani, Constantinovici and Williams2004) in their one-year follow-up study of employees taking early ill-health retirement from the British National Health Service. However, the rate we found is higher than the figures observed by Kanabar (Reference Kanabar2015) in a general population sample. Differences may be due to the fact that Kanabar used biennial data to examine unretirement among individuals who often had been retired or inactive for some time and retrospectively reported retirement dates. However, as we and others have found, unretirement tends to take place quickly following retirement, if it takes place at all (Hayward, Hardy and Liu Reference Hayward, Hardy and Liu1994; Kail and Warner Reference Kail and Warner2013; Pleau Reference Pleau2010; Schuring et al. Reference Schuring, Robroek, Otten, Arts and Burdorf2013). Thus, studies which do not follow individuals from the moment of retirement are likely to under-estimate unretirement rates as a result of left-censoring or briefer unretirement spells not being retrospectively reported.

Retirement reversals occurred both before and after the state pension age for men and women (cf. Figure 1). This implies that future research which examines unretirement should not limit analyses to participants who have already reached state pension age. Retirement can take place earlier, particularly since occupational and private pensions may have other conditions of eligibility, or jobless individuals in late career may be forced into retirement because of difficulties in finding another job (Loretto and Vickerstaff Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2013).

Unretirement was more common among certain groups of retirees. Specifically, men were 25 per cent more likely to unretire than women, those with no qualifications were almost 50 per cent less likely to unretire than those with post-secondary qualifications, and participants in excellent or good health were around 25 per cent more likely to unretire than those reporting fair, poor or very poor health. These results are in line with previous research from Canada, the USA, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden (Fasbender et al. Reference Fasbender, Wang, Voltmer and Deller2016; Larsen and Pedersen Reference Larsen and Pedersen2013; McDonald Reference McDonald1997; Pleau Reference Pleau2010; Schellenberg, Turcotte and Ram Reference Schellenberg, Turcotte and Ram2005; Schuring et al. Reference Schuring, Robroek, Otten, Arts and Burdorf2013), and those concerning qualifications and health correspond to previous work on British men (Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015; Meghir and Whitehouse Reference Meghir and Whitehouse1997).

Most financial factors, whether perceptions of financial situation, household income or having an occupational pension, were not associated with unretirement at the 95 per cent significance level. This result is consistent with previous research from England, Germany and the USA (Fasbender et al. Reference Fasbender, Wang, Voltmer and Deller2016; Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015; Maestas Reference Maestas2010). Our null result may reflect countervailing tendencies of a stronger desire for paid work and greater difficulty finding it (sufficiently well-paid) for those facing financial hardship. Some support for this interpretation comes from our observation that participants who held a mortgage on their homes were over 50 per cent more likely to unretire than those who owned their homes outright. Mortgage-holders have an additional substantial outgoing compared to home-owners, which suggests the importance of financial factors. The lifecycle hypothesis of savings and consumption developed by Modigliani and colleagues argues that people begin to run down lifetime accumulated assets at retirement (Jappelli and Modigliani Reference Jappelli, Modigliani and Franco2005). From this standpoint, unretirement behaviour can be viewed as a way to reduce the rate of decumulation at retirement and smooth consumption patterns, particularly, as shown here, in the face of requirements to maintain mortgage payments (Lahey, Kim and Newman Reference Lahey, Kim and Newman2006).

The study also explored the importance of several non-financial factors upon unretirement behaviour. Individuals whose spouse was employed were more likely to unretire, compared to those whose partner was not in the labour force, suggesting that lifestyle considerations, such as co-ordination of retirement timing between spouses, may be important (Dahl, Nilsen and Vaage Reference Dahl, Nilsen and Vaage2003). However, providing informal care for at least 20 hours per week was not associated with unretirement, confirming findings reported by Pleau (Reference Pleau2010).

The finding that men were 25 per cent more likely to unretire than women was robust to adjustment for a range of covariates relating to demographic characteristics, financial need and health. Furthermore, we did not discern gender differences in the associations between unretirement and any of the covariates by including interactions. It is possible that this aspect of the analysis is under-powered (i.e. insufficient sample size) or that gendered unretirement is related to factors not included in the model (Hardy Reference Hardy1991). Women's lower rates of unretirement may be indicative of a weak attachment to the labour force that begins during the child-bearing and child-rearing years and extends into old age – at least, for these cohorts of women (Hardy Reference Hardy1991; Scherger Reference Scherger and Scherger2015). These results warrant further investigation in a larger survey, such as Understanding Society, once more waves of data are collected. Important factors to consider in investigating gender differences in retirement rates include age discrimination, part-time working, caring responsibilities, work–family conflict and earnings.

Limitations

Despite the large size of the BHPS sample, the requirement for a transition into retirement to be observed limited the numbers of eligible participants. In order to maximise the sample size, the effects are averaged over more than 20 years, a period that saw changes in individuals’ labour market prospects, pension legislation and payments. The sample size may have also limited the possibility of discerning small effects of covariates or those which were important over only part of the period under study.

There is a possibility that the complete case results were affected by non-random attrition and non-response. However, our sensitivity analysis using full information maximum likelihood estimation to obtain estimates for individuals with missing predictors, based on the assumption that the data were missing at random, yielded results close to those obtained from the complete case analyses which require the more restrictive assumption that the data are missing completely at random (see Table A1 in the online supplementary material).

This analysis used time-invariant covariates from the last observed year in paid work before retiring. However, as has been argued by Congdon-Hohman (Reference Congdon-Hohman2009), it is likely that these covariates may change following retirement. This may be especially the case for health (Westerlund et al. Reference Westerlund, Kivimäki, Singh-Manoux, Melchior, Ferrie, Pentti, Jokela, Leineweber, Goldberg, Zins and Vahtera2009, Reference Westerlund, Vahtera, Ferrie, Singh-Manoux, Pentti, Melchior, Leineweber, Jokela, Siegrist, Goldberg, Zins and Kivimäki2010) and income, both of which decline with age. Incorporating these time-varying elements in our analysis of unretirement would have enabled us to explore the degree to which unretirement is planned while still in paid work or is a response to shocks (Maestas Reference Maestas2010).

Finally, we cannot be wholly confident of the generalisability of our results to the UK population as a whole because it was not possible to develop appropriate weights with these data for this analysis. In addition, because this study was restricted to participants with a record of employment or self-employment from age 40 onwards, those who transitioned into retirement from unemployment or family care were not included. This limitation is particularly pertinent in the case of women, who have lower participation in paid work in the late career than men (Corna et al. Reference Corna, Platts, Worts, Price, McDonough, Sacker, Di Gessa and Glaser2016).

Future research

Apart from one study of English men (Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015) which examined the characteristics of unretirement jobs, little research has explored the nature of paid work following retirement in the UK. Largely unexplored questions concern how long unretired people stay in paid work before re-retiring; what sorts of jobs they do and how earnings from these jobs compare with pre-retirement work. Specifically, are unretirement jobs of poor quality and low-paying? If so, are these terms acceptable to retirees because they are supplemented by a pension or because working resembles a paid hobby? Or do unretired workers have wages and working conditions resembling those of younger workers?

Other activities may demand the time of retirees, such as volunteering and the provision of formal care. They may compete with or complement paid work (Carr and Kail Reference Carr and Kail2013; Griffin and Hesketh Reference Griffin and Hesketh2008). Related to this, an important issue in post-retirement labour market research is the extent to which individuals who wish to unretire are able to do so (Macnicol Reference Macnicol2015; Moffatt and Heaven Reference Moffatt and Heaven2016). How much choice and control over reversing their retirement do people have? An additional emerging avenue in the unretirement literature is the extent to which individuals’ bonding or bridging social capital assists them in finding post-retirement jobs, and whether having high levels of social capital might compensate for low human capital (Gonzales and Nowell Reference Gonzales and Nowell2016).

Policy implications

One implication of our results is that recently retired people, aged both above and below the state pension age, represent a pool of potential labour, if the right opportunity presents itself. They are a group that should not be forgotten by policies aiming to maintain older people in work (BIC, ILC-UK and PRIME 2015: 9–10; Eurofound 2012). Although the influence of particular policies could not be tested, the results presented in this paper suggest that policies that protect older employees against age discrimination and tackle over-employment (having to work more hours than desired by the employee) by encouraging more flexible working may raise the employment rates of older people both before and after state pension age, by improving their labour market opportunities.

Knowing the determinants of unretirement is helpful in order to understand if and how social policies might alter unretirement rates and inequalities related to unretirement. Specifically, the results presented here demonstrate the importance of maintaining individuals’ human capital (in terms of skills and health) throughout their working lives. Relevant initiatives might include enhancing workers’ access to training, promoting safer workplaces and supporting occupational health.

Evidence presented in this paper has shown the paradoxical role of household finances in unretirement decisions. Financial difficulties, per se, are not sufficient to act as a driver for retirement reversals. Should reliance on earned income in later life increase, new inequalities in later life could be generated between those who find suitable work and those who do not. It has been suggested that unretirement might help boost incomes in retirement and reduce pensioner poverty (Kanabar Reference Kanabar2015). We suggest that unretirement has a tendency to enable those who are already well-favoured to improve their incomes further, whereas those less favoured remain disadvantaged, potentially exacerbating income inequalities in later life.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that unretirement is a common feature of retirement processes in the UK, and is likely to be an important strategy that people may use to manage late working life. However, the evidence that people with more human capital have a higher likelihood of unretiring, rather than those in financial difficulties, suggests that hopes that retirement reversals might be a strategy which enables older people in poorer financial situations to raise their incomes are possibly misplaced. Instead, possibilities to supplement savings or retirement income in later life through unretirement are available to a greater extent to the already advantaged.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X17000885

Acknowledgements

Data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) were supplied by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Data Archive. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analysis or interpretations presented here. Understanding Society is an initiative by the ESRC, with scientific leadership by the Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex, and survey delivery by the National Centre for Social Research. The authors were funded by the British cross-research council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing (LLHW) programme under Extending Working Lives as part of an interdisciplinary consortium on Wellbeing, Health, Retirement and the Lifecourse (WHERL) (ES/L002825/1). L. G. Platts additionally received funding from the Swedish Forskningsrådet för hälsa, arbetsliv och välfärd (2012-1743). D. Worts was also funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number MOP 11952, Principal Investigator Peggy McDonough) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (grant number 435121267 Principal Investigator, Peggy McDonough). Rachel Stuchbury contributed to preparing variables from Understanding Society. The authors thank Christopher Brooks and José Iparraguirre at Age UK for feedback on an earlier version, as well as participants at the British Society of Gerontology conference, the Centre Metices seminar at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, and the Pensions Policy Institute seminar. L. G. Platts conceived the manuscript in discussions with L. M. Corna, K. Glaser and D. Price. L. G. Platts prepared the variables in collaboration with D. Worts and performed the analyses. All authors were consulted in preparing the variables. L. G. Platts drafted the manuscript. All authors commented on drafts and approved the final text. The authors declare no knowledge of conflicts of interest.