How do local citizens digitally converse in public when confronted with a community’s most contentious divisions—the long-standing conflict between democracy’s definitional demands for racial equality on one hand and the reality of institutionalized white supremacy on the other (Eckhouse Reference Eckhouse2019)? And how well do participants in those dialogues reflect their community’s demographics and politics, especially given race-class political inequities in places sharply segregated along those lines (Michener Reference Michener2016)? These questions test the communicative roots of democracy—whose voices are heard, whether such dialogue enflames or pacifies racial conflict, and how those words strengthen or weaken multiracial democracy (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1983; Mendelberg and Oleske Reference Mendelberg and Oleske2000; Weaver, Prowse, and Piston Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2020).

We examine a critical case involving racial justice protests against racially biased police violence. Baton Rouge reeled in July 2016 after local police killed a Black citizen, Alton Sterling, generating weeks of large protests. Local TV news broadcast the protests unfiltered using the new Facebook Live online video utility as they transpired in real-time. In unmoderated comments appearing below each video, Baton Rougeans, Louisianans, and more distant others affirmed and confronted each, often in violent and racist terms, while watching police arrest and attack peaceful protesters on their screens.

To evaluate democratic representation in this public dialogue and to take measure of its volatile nature, we collected and assessed a representative sample of over 3,000 messages from the full population of comments about the dozens of videos published by all local news outlets. First, we find surprising local representativeness among commenters along demographic and sociopolitical lines compared to local census data and a representative local survey. Second, we document the volume of violent and racist rhetoric in these forums directed at Black community members, threatening core democratic values of non-violence and racial equality. We identify correlates of enflaming and pacifying comments including expressed racial views and demographic factors linked to interpersonal aggression. Finally, we identify commenter and comment attributes that draw positive audience feedback, which depend on sex, education, and local ties, along with violent and demeaning content.

We conclude by considering the broader implications of our findings for contentious communication in a struggling multiracial democracy and discuss the unique value of studying those ancient conflicts in local digital environments. But first, we begin by setting our expectations with a review of research on participatory democracy, racial inequities, the character of racial dialogue, and protest effects.

Voice, Representation, and Violence

Democracy is founded on the principle of equal say in government among all citizens. The communication corollary involves equal voice in deliberations among the governed. These values undergird liberal commitments to free speech and press that are necessary to democratic governance (e.g., Habermas Reference Habermas1962), though European models of democratic speech more fully recognize the destruction unfettered speech can wreak upon democracy (e.g., Citron Reference Citron2017). Rampant structural inequities by race in the United States cause those egalitarian ideals to fall short in all areas, including communication. Local democratic models often involve formal town hall-style deliberation, where proximity and local knowledge enable some direct democracy (e.g., Walsh Reference Walsh2007), but local democratic communication also manifests in impromptu dialogues around events that can bring people together or sow deadly division.

The democratic ideal of equal voice falls short with unequal political participation rates by class, sex, and race, especially in participation beyond voting (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012; Eckhouse Reference Eckhouse2019; Walton Reference Walton1985; Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014). As a result, the voices heard by and reflected in government fail to represent the public (e.g., Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018). Institutional barriers have been the most notable limits to equal participation in the past for Black Americans (Keele, Cubbison, and White Reference Keele, Cubbison and White2021) and women (Corder and Wolbrecht Reference Corder and Wolbrecht2016; McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2013; see also Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014). Black women surmount some of these barriers to participate in politics at high levels as a function of greater social capital (Farris and Holman, Reference Farris and Holman2014).

With the rise of mass Internet use, some people expected a leveling of barriers to political expression, producing greater access to social and organizational tools and thus greater equality of voice as technology changed the way people do politics (Gil de Zúñiga, Molyneux, and Zheng Reference de Zúñiga, Homero and Zheng2014; Turcotte et al. Reference Jason, York, Irving, Scholl and Pingree2015). Yet despite egalitarian hopes, a suite of inequalities reproduces the gaps seen in other domains (Wei and Hindman Reference Wei and Hindman2011). Facebook—the social media platform in our study—is relatively representative in its users compared to others—two-thirds of U.S. adults used Facebook in 2016 compared to less than 30% for Twitter, Snapchat, and Instagram (Pew 2018a). Facebook is also an important site for news and current events—nearly half of U.S. adults get news there, far more than any other social media platform (Pew 2017). Although roughly one in six people say social media has changed their views on an issue (Pew 2018b), social media usage is generally more likely to reinforce views and provide like-minded information than to lead to ideological or attitudinal shifts (Shirky Reference Shirky2011). Thus, social media sites tend to be used more for affiliation and expression than deliberation.

Democracy and Violence

The promises of egalitarian democracy constrain citizens and their government. The democratic bargain is this: citizens agree to non-violence so long as democratic promises are kept; government can expect peace from citizens so long as it guarantees democratic politics including civic equality (Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991). Others have a different balance in mind, imagining the United States as a promised “white man’s republic” (Lynn Reference Lynn2019), with whites deploying non-state violence against government and citizens when they feel their undemocratic power is threatened. Official use of state violence—police, prisons, militias—often served similar aims.

Conventional politics and violence often went together in American history, particularly around the defense of white supremacy. Most notably, whites in Southern states rebelled against the 1860 presidential election, fearing that their loss doomed their hopes of expanding slavery (Kalmoe Reference Kalmoe2020). After the war, white Southerners turned to mass lynching, militias, and Ku Klux Klan terror to stop Black voters and their political allies who kept defeating them at the polls. The white South eventually wrested power from a weary federal government, returning the South to white supremacy for a century of anti-Black authoritarianism and violence that still has substantial vestiges in today’s systemic racial inequities (Cook, Logan, and Parman Reference Cook, Logan and Parman2018; Du Bois Reference Du Bois1997; Foner Reference Foner1988; Keele et al. Reference Keele, Cubbison and White2021; Mickey Reference Mickey2015).Footnote 1 But for as long white people have systematically murdered Black people, organized Black efforts have successfully worked to stymie that violence through public awareness and pressure on government to act (Francis Reference Francis2014).

Past violence still shapes present politics: within the South, places that enslaved relatively more Black Americans have whites who are more Republican and more anti-Black than other Southern places (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018), and places with more lynchings a century ago have more police-involved killings and less Black voter registration today (Williams Reference Williams2020; Williams and Romer Reference Williams and Romer2020). And despite a period of mid-twentieth-century democratization that produced Black enfranchisement and the end of de jure (but not de facto) segregation, whites implemented an increasingly punitive and violent criminal justice system to disempower Black Americans economically, socially, and politically (Weaver Reference Weaver2007).

Violence and threats can move political elites and public opinion toward or away from the goals of groups associated with that violence (Chenoweth and Stephen Reference Chenoweth and Stephen2011; Lyall, Blair, and Imai Reference Lyall, Blair and Imai2013; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018). For example, Wasow (Reference Wasow2020) finds that proximity to violent protests and uprisings in the 1960s increased vote share for Republican “law and order” candidate Richard Nixon, helping him win the 1968 presidential election, while proximity to peaceful protests boosted Democratic vote share. In contrast, Enos, Kaufman, and Sands (Reference Enos, Kaufman and Sands2019) find that violent protests in Los Angeles after the 1992 police beating of Rodney King increased support for change in policing. Reactions to violence during protests also depend on the proportionality of actions by police and citizens. The public looks more favorably on violence in retaliation for violence by the other side, but without that provocation, escalation seems inappropriate (Davenport, Armstrong, and Zeitzoff Reference Davenport, Armstrong and Zeitzoff2016).

Violence affects political participation too. Use of force by police can have a demobilizing effect on local Black political participation (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014), but Black participation in the state violence of World War II and the Korean War mobilized participation in civil rights activism among those veterans in the South (Parker Reference Parker2009).

Talking about White Supremacy

Race is central to political sense-making for most Americans (Hutchings and Valentino Reference Hutchings and Valentino2004), and political communication on race has long featured white supremacist rhetoric (Gates Reference Gates2020; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). The late twentieth century saw the establishment of new norms against explicit expressions of prejudice in public, but those proscriptions have rapidly eroded in recent years as white nationalists became more outspoken in public life and rose to the highest echelons of American government (Hutchings, Walton, and Benjamin Reference Hutchings, Walton and Benjamin2010; Valentino, Neuner, and Vandenbroek Reference Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek2018). As a result, racists today are more likely to forgo the seemingly egalitarian codewords in public settings that they previously used to obscure prejudiced appeals (Mendelberg and Oleske Reference Mendelberg and Oleske2000). Our focus on public racial dialogue supplements research on private and counter-public discussions on police violence and politics generally (Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2006; Huckfeldt et al. Reference Huckfeldt, Beck, Dalton and Levine1995; Walsh Reference Walsh2002; Weaver, Prowse, and Piston Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2020).

Racial discussions are especially fraught in eras when race aligns with partisanship and other social identities, as it increasingly does today (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1990; Jardina Reference Jardina2019; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018; Tesler Reference Tesler2016). Even more than the rest of the country, Louisianans are highly sorted by party and race: in the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey, 74% of white voters chose Republican Donald Trump while 93% of Black voters chose Democrat Hillary Clinton (N=429). The alignment of social and political identities increases political animosity (Mason Reference Mason2018), which creates vectors for mobilizing hostility into political action and violent resistance. Of course, explicit appeals to race can also serve to advance racial justice (e.g., Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2007; White Reference White2007).

Conversations about race serve to clarify identities and interpret politics (Walsh Reference Walsh2007). But rather than facilitating superordinate identities that bond people, interracial dialogue often fuels conflict by emphasizing difference (Mendelberg and Oleske Reference Mendelberg and Oleske2000; Walsh Reference Walsh2007). Digitally distant comments in an online forum may manifest differently than in-person community dialogues, worsening outcomes. Social context and interpersonal relationships shape the expression of racial attitudes and identities in group settings, with in- and out-group environments exerting conformity and social desirability pressures (White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020; Walsh Reference Walsh2002, Reference Walsh2007). Social context also matters for Internet-based racial expressions. For example, white men who challenge racist commenters can reduce the prevalence of subsequent racist comments (Munger Reference Munger2017). Relatedly, using the Internet intensifies disinhibition and validates racist views (Chau and Xu Reference Chau and Xu2007; Erjavec and Kovačič Reference Erjavec and Kovačič2012). Those virtual interactions provide social and psychological reinforcement for extreme views that are less likely in the everyday world.

Hateful and Aggressive Online Rhetoric

In the context of racial justice protests, who is likely to escalate interactions with aggressive rhetoric—including calls for violence—who is likely to deescalate through calls for peace, and who uses racial derogation as a cudgel against their opponents?

We note from the start that, by comparing levels of hostile rhetoric between Black Lives Matter supporters and white advocates of police violence, we do not normatively equate the two. Identical rhetorical forms have very different implications for democracy depending on power disparities between speakers. Put bluntly, extreme vitriol and violent advocacy in pursuit of racial justice and equal rights can be appropriate—even necessary—in a way that advocating violence against racial justice and equality clearly cannot be. Even so, we expect to find that Black Baton Rougeans bore the brunt of online aggression and hate.

Anti-social communication behaviors that portend violence are engrained in many deliberative digital spheres. Marwick and Lewis (Reference Marwick and Lewis2017) document the mainstreaming of violent white supremacist ideologies through cyber-subcultures that adhere to extreme views of freedom of speech. DeKoster and Houtman (2008) note how these online communities construct racist attitudes and social action. More broadly, Ventura and colleagues (Reference Ventura, Munger, McCabe and Chang2021) identify a high rate of toxic and insulting comments on digital live streams of presidential debates on Facebook news pages. Hmielowski, Hutchens, and Cicchirilo (Reference Hmielowski, Hutchens and Cicchirilo2014) examine the normative acceptability of aggression in online political message boards, finding that the prevalence of “online flaming” leads users to accept heightened aggression. Together, these studies capture how insular online communities nurture—or at least ignore—violence at its genesis.

These phenomena are partly due to the lack of effective platform moderation from the top-down (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2018) and from within online communities (Marwick and Lewis Reference Marwick and Lewis2017). In relatively stable social spaces, these field “incumbents” (Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2011) wield immense power to temper behaviors that undermine a coalition’s socio-political goals. Whereas successful traditional movement cultures thrive on self-moderation (Tufekci Reference Tufekci2017), loosely organized online discussions are fundamentally transient, reactive, and volatile. These peculiar power dynamics and minimal social controls online may expose racial justice advocates to immense violence and racial stereotyping.

The study of violent political attitudes and aggressive behavior outside of politics suggests a few trends that seem likely to recur here (e.g., Anderson and Bushman Reference Anderson and Bushman2002; Kalmoe Reference Kalmoe2014; Kalmoe and Mason Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022). In and out of the political domain, men are somewhat more aggressive than women, on average, and people with more education tend to think and act less aggressively than those with less. Young people also tend to behave more aggressively than older people. And, of course, the political targets for aggression depend on underlying political views. Aggression also corresponds with collective power. White Americans have long felt freer to insult, threaten, and attack Black Americans, knowing that the force of law will fall less heavily on them for the same expressions and behaviors (Davenport, Soulle. and Armstrong Reference Davenport, Soule and Armstrong2011). For the same reasons, Black Americans may hold their tongues in the face of white provocation (Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019). These collective differences, shaped by power, lead us to expect more aggressive behavior from white discussants directed at Black targets, especially in extreme forms.

Research Methods

Our study investigates the content and the demographic and sociopolitical representativeness of social media comments on local news live streams of contentious racial justice protests.Footnote 2 Toward that end, we sampled and coded comments posted under Facebook Live videos broadcast by journalists from the city’s major newspaper, The Advocate, and from all four local television network news channels (i.e., ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX) during the July 2016 protests in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.Footnote 3 We documented profile traits of commenters to compare with local demographics and conducted a representative survey of Louisiana and Baton Rouge adults in January 2017 to compare public opinion with the views expressed in comments. We also coded comments for violent, pacifying, and racially degrading content to assess democratically corrosive rhetoric and its correlates—and who is targeted by that wrath.

Our use of untrained coders from the general public (Mechanical Turk Master workers) draws empirical focus to how ordinary people interpret these contentious messages (see e.g., Adams Reference Adams2016; Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Conway, Lauderdale, Laver and Mikhaylov2016; Burleson and Samter Reference Burleson and Samter1985). Scholars taking this approach often rediscover the breadth and diversity of public interpretations that belie neat elite categorization, with the natural consequence that diverse people in the public agree less with each other than academic coders (Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Conway, Lauderdale, Laver and Mikhaylov2016). However, for our analysis, we focus on cases of agreement between ordinary coders, further validated by an expert coder with local contextual knowledge.

The Case: Alton Sterling’s Death by Homicide

Our study focuses on public reactions to protests after police killed Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old Black man living in Baton Rouge, a majority-Black city. On the night of July 5, 2016, Sterling was selling CDs outside a convenience store when two city police officers accosted him while responding to a call that a man had threatened another with a gun. The store’s owner said Sterling was not the cause of the emergency call. Sterling had recently started carrying a gun after other CD sellers were robbed. In violation of department regulations, the officers ran at Sterling with guns drawn and tackled him within seconds of arriving on the scene. As they wrestled on the ground, one of the officers felt the gun in Sterling’s pocket, shouted, “He’s got a gun!” and then shot Sterling six times in the chest. Cell phone videos, surveillance cameras, and police body cameras recorded the whole incident.

Sterling’s killing led to weeks of local mass protests and hundreds of arrests, during a summer filled with similar protests against police violence in several cities. The events in Baton Rouge made international news. Subsequently, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Louisiana attorney general opened civil rights investigations into Sterling’s killing. The American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against the Baton Rouge Police Department for their unlawful arrests of peaceful protesters and journalists recording the protests. Nearly two years after the shooting, the officer who shot Sterling was fired for violating use of force policies. The other officer was suspended for three days. Neither was charged for killing Alton Sterling.

Sterling’s killing joined a long pattern of abuses against Black Baton Rougeans going as far back as anyone cares to look. For example, Baton Rouge police are five times likelier to enforce drug laws in starkly segregated Baton Rouge’s predominantly Black neighborhoods than in white neighborhoods, despite similar rates of drug use (Together Baton Rouge 2017). Louisiana only recently overturned non-unanimous jury laws that have disproportionately incarcerated and disenfranchised Black Louisianans since whites implemented them in the 1890s to reestablish white supremacy under Jim Crow (O’Donoghue Reference O’Donoghue2018).

Facebook Live Comments

Facebook Live is a video application allowing users to stream real-time video content within a social media post on the Facebook platform. The video runs live and then saves, allowing later viewing. Facebook users can post comments, “like,” and share the post during and after the live stream. Several local print and broadcast news organizations in Baton Rouge used the app to supplement their reporting with real-time views of the protests, sometimes with reporter commentary. First, we searched Facebook pages for each local broadcast news channel and the local newspaper in the videos section, focused on July 2016 posts with more than 100 comments. We sampled roughly 100 comments from each of thirty-one videos. Our sample includes 3,170 comments posted by 2,123 unique commenters. From a total population of 119,365 comments, that yields a full-sample margin of error of +/- 1.7%.

Facebook Profile Coding and Mechanical Turk Comment Coding

We coded commenter’s demographic and sociopolitical details using information they made publicly available on Facebook. Profiles can include as much or as little information as users wish, and we face missing data problems on some traits. We recorded profile information for these traits, along with current town, hometown, work and school connections to Baton Rouge, college attendance, and any religious or political views. Only 3% of profiles were deactivated when we accessed profiles two years after the videos posted, and so we lost very little information about commenters in that way. Demographic traits of race, sex, and age were among the most available by explicit listing or via inference from names and profile pictures.

Next, we paid Amazon Mechanical Turk Master workers minimum federal hourly wage to double-code each comment for relevance (86% of total comments; Cohen’s κ = .26) to exclude comments when both coders agreed a comment was irrelevant to the topic of this study. MTurk Master workers then double-coded relevant comments on ten dimensions: intended to reduce conflict; negative about a racial group; insult; view of news; view of police view of protesters; view of Sterling’s killing; whether police should use more or less force against protesters; whether the comment calls for violence, and whether the comment indicates whether the United States has reached racial equality, has gone too far, or more needs to be done.

Interrater reliability between the two coders was “fair” on seven of the 10 traits (.20 < Cohen’s κ <.40) and “slight” on three others (Cohen’s κ <.20), according to the standards suggested by Landis and Koch (Reference Landis and Koch1977). That variation reflects the clear diversity in how the public interprets racial rhetoric in America (Mendelberg and Oleske Reference Mendelberg and Oleske2000) along with the challenge of interpreting brief texts when lacking contextual information (Adams Reference Adams2016). Kappas are also higher when codes are equally probable, which was decidedly not true here. The vast majority of substantive coding categories did not apply to most comments, leading to “unclear” codes for 90% or more of some categories. Analytically, mixed or ambiguous interpretations would mostly reduce the chances of finding significant statistical relationships with other traits in our correlates tests for tables 5–8. The online appendix reports the details of these coder comparisons.

To validate our MTurk-based measures further, we hired a white political communications graduate student who grew up in Baton Rouge. She served as an expert coder on 40% of the comments (random sample), bringing local contextual knowledge to the comments along with academic knowledge of implicit and explicit racial rhetoric. We did not inform her of our expectations, and she had only the comment texts to work with, as the MTurk coders did. We initially coded MTurker disagreement as a partial instance of a comment trait. However, we found that that produced low agreement with the expert coder and much higher frequencies for each trait than the expert coder identified, so we coded the presence of a comment trait only when both MTurkers agreed. That approach produced substantially better reliability levels and aligned the levels of MTurk comment traits with those found by the expert coder.

Thus, our analysis proceeds with this “full MTurker agreement” coding strategy. Expert codes only factor in the main text as reliability tests. The online appendix replicates all the MTurk tests using just the expert codes, producing similar results. Thus, we have high confidence in our measures when both MTurkers agree on the presence of a comment trait. The MTurkers did not agree with each other as often as we would prefer, but their combined judgment produces quite similar conclusion to when we rely on the local expert coder.

Census Data and the Louisiana Survey

We compare the demographics of social media commenters to local and state-level demographics from 5-year census estimates provided in the 2015 American Community Survey. From there, we draw information on race, age, and sex for Louisiana and for the Baton Rouge metro area. Our 2017 representative telephone survey of Louisiana adults (N=1,079) included an oversample of people from three parishes in the Baton Rouge metro area (N=361), with a 19% response rate. We asked several questions on race and policing comparable to the Facebook comment codes. The online appendix gives the sample’s demographic and socioeconomic traits, which correspond well with Louisiana’s and Baton Rouge’s demographics and socioeconomics.

Results on Representation

Representative Voices? Demographics

Our first question is whether these are local voices at all. The answer is a resounding yes, as might be expected with videos from Baton Rouge news organizations, but which wasn’t certain given the reach of the Internet and national interest in these protests. Among those who listed a current city, 45% lived in or adjacent to Baton Rouge and 73% listed a Louisiana city. Adding people who grew up in or near Baton Rouge raises the local total to 54%, and adding native Louisianans who moved outside the state (or who listed no current city) raises the total with a Louisiana connection to 80%. We can’t know whether profiles without place data resemble those listing that information, but it’s a reasonable starting point for a rough estimate. Overall, then, these were predominantly local and state dialogues.

Next, we consider how commenters aligned with local and state demographics. Table 1 gives commenter race, sex, and age and equivalent statistics for local and state populations. We have race estimates for 94% of profiles, sex for 96%, and age for 69%. Age and sex were coded from profile self-reports, and all three were estimated by coders from profile picture and name if not given explicitly. Of course, physical appearances and names may not reflect gender or racial self-identification.

Table 1 Local digital participants and local populations

Note: Facebook profiles among those making relevant comments. BR = Baton Rouge-linked profiles; LA = Louisiana-linked profiles. “LA” excludes Baton Rouge-area comments.

Race and sex among commenters were remarkably similar to local and state demographics overall. The numbers match almost exactly for proportions of white folks, though we also code an “unclear” category with 13%. Black folks were somewhat underrepresented among those with profile pictures of themselves. Women and men also participated in near-equal proportions to local and state statistics. Women were slightly more likely to comment, which may be surprising in a contentious and frequently uncivil comment thread.

Demographics were even closer to local and state proportions among commenters with Baton Rouge or Louisiana connections. What about the intersection of sex and race? Overall, white women comprised 35% of commenters, and 29% were white men. Black women were 14% of commenters, and 6% were Black men. Proportionality would have been around 32% for white men and women and around 15% for Black men and women. Thus, Black men were substantially underrepresented. White women’s elevated participation rates here are in keeping with the group’s historical involvement in upholding white supremacy in informal spaces (McRae Reference McRae2018), while Black women’s participation is bolstered by social capital that partially offsets other disadvantages (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014).

Age matched less with Louisiana populations. Middle-aged adults dominated half the conversation, well out of proportion with their one-third portion of the population. Younger voices were especially absent. However, we should note that our age categories do not align perfectly with the census estimates, and so we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the slippage is due to these binning differences. Overall, we conclude that racial conversations in threads that follow the live protest videos were surprisingly representative of local and state demographics, especially when taking broader national distributions of Facebook users into account (i.e., more women).

Representative Voices? Sociopolitical Views

Next, we consider how opinions expressed in online comments align or diverge from public opinion in the metro area and the state. Public beliefs and social media expressions of beliefs are distinct processes, of course. What people think is not always what they choose to say in public to strangers. Our aim in comparing them is to learn whether the expressive people online closely reflect or substantially distort the impression one gets of public views on these topics. In other words, do the loudest voices reflect the balance of views among ordinary people, or do distortions seen in expressions make audiences think the public is more anti-Black or pro- than they really are? After all, impressions of group opinion have important effects on public attitudes and behavior (Mutz Reference Mutz1998; White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020) and plausibly shape elite behavior too. Comparing closed-ended survey responses to open-ended comments is also challenging given the ways that question formats can affect answers. Nonetheless, we assess the extent to which the balance of made comments reflect or diverge from public opinion.

In particular, we match survey questions and comments about whether Sterling’s killing was justified, support for or opposition to protesters, police, and news coverage of the event, and general views of racial equality in the United States. Comments coded as support for protesters included “#BlackLivesMatter,” “NO JUSTICE NO PEACE,” and “Fuck all y’all racist white ass people.” Comments coded as critical included “#AllLivesMatter” and “You can’t reason with animals.” One comment claiming equal rights had gone too far wrote “White lives matter!” while one coded as “more needs to be done” said “It shouldn’t stop until we get JUSTICE.” Comments advocating for police to use more force against protesters include “Arrest them all!!!” “Fire hose is non lethal but effective,” “BRPD needs to take back our streets by force now!” and “Bring in the National Guard!”

Table 2 presents comment views along with local and state survey responses. Comment percentages indicate when both coders recognized the trait in the comment. We show full sample numbers, the percentages for Baton Rougeans, and the same for non-Baton Rouge Louisianans, given that the local residents comprise two-thirds of Louisianans in the sample (versus 13% by population). The sometimes brief replies naturally do not provide information on each category of views, and so the vast majority of comments give no indication on any given trait. Instead, we care about the balance of positive and negative views among those expressed, relative to survey levels.

Table 2 Local digital views and local public opinion

Note: Facebook profiles among those making relevant comments. “LA” excludes Baton Rouge-area comments. Weighted survey estimates. “Louisiana” excludes Metro Baton Rouge oversample. Metro Baton Rouge N=361, Louisiana (excl. MBR) N=718.

Overall, the balance of online support and criticism for protesters seems to roughly match the metro Baton Rouge balance of opinion in the survey. The survey showed 47% of Baton Rougeans thought the protests justified, and 35% of Louisianans outside the metro area said the same. To compare the comments, we disregard the “no indication” percentages and report the percentages among comments that indicated a view. When expressed clearly in that way, 43% of local comments and 33% of Louisianan comments beyond Baton Rouge supported rather than criticized protesters. Similarly, 68% of Baton Rouge commenters and 45% of Louisianan commenters said police were unjustified in killing Alton Sterling, among those who commented clearly. Conversely, 74% of Baton Rouge comments about police were positive compared to 82% positive among other Louisianans.

Baton Rouge and Louisiana commenters balanced evenly between the two views of police force against protesters, with just over half preferring more force rather than less among those giving some indication. In contrast, the survey found four times as many Baton Rougeans and nearly three in five Louisianans saying they thought police should use less force against protesters versus more—a substantial divergence from social media comments. News media criticism was roughly as prevalent in the comments as in similar survey questions. Finally, online comments lopsidedly proclaimed the need to do more for the country to reach equality—around 80%—even more so that public opinion around 50%. On the other side, beliefs that equality efforts had gone too far were near 15% in local and state comments and survey responses.Footnote 4

Of course, these opinions are pooled in a place that we know is heavily polarized by race, even more so than large nationwide racial divides (Kinder and Winter Reference Kinder and Winter2001), particularly due to the fusion of partisanship and race in the Deep South. What do these views look like when disaggregated by race? Here, we limit the comparisons to comments written expressing a substantive view on the topic (as we did in discussing table 2) for whom we have a racial categorization. For sufficient cases, we show comments just for the Baton Rouge metro area. Table 3 presents the results.

Table 3 Racial gaps in local digital views and local public opinion in Baton Rouge

Note: Weighted survey estimates among those giving substantive answers. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Among Baton Rougeans, we observe substantial gaps by race among commenters and in the local survey, though the directions of those gaps are generally consistent between comments and the survey despite small samples. Racial differences in Facebook comments about Sterling’s death closely match the survey differences in whether the protests are justified. Six in ten Black commenters supported protesters, and 69% of Black survey-takers said the protests over his death were justified. White commenters and white public opinion disagreed, with two-thirds of white commenters and 57% of white survey-takers seeing the protests as unjustified. Black commenters were equally focused on the need for more racial progress (88%) compared to Black survey-takers (86%), while white commenters who explicitly commented on the topic were far more sympathetic about needing more racial justice in Facebook comments (88%) than in the survey (38%). Racial differences on police use of force were more muted among commenters compared to survey-takers, and commenters of both races were more hostile toward local news than survey takers.

In sum, the results indicate a surprising level of rough correspondence between sociopolitical comments from our Facebook sample and the local and statewide survey views, though we remain mindful of the limits in direct comparisons given mode and wording differences. In particular, while demographic categories and overall attitude distributions were generally similar, racial gaps between commenters were more muted than those in the survey, perhaps suggesting the presence of more racially progressive whites in the comments than in the local population. In any case, both the comments and the survey responses broadly confirm large gaps in how local Black and white residents think and talk about racial justice issues in public.

Reesults on Enflaming and Pacifying Rhetoric

We now shift our focus from representativeness to enflaming and pacifying rhetoric, including racial derogation and calls for violence. We illustrate categories with examples, followed by descriptive statistics and multivariate correlates. Our first three categories involve comments advocating violence by people other than police against any target (protesters, police, commenter). The inverse is an explicit rejection of violence. Coders agreed on evaluations for 74% of comments on these violence categories.

For violence against protesters, one commenter wrote “You block my drive home, you are gonna be a speed bump.” Others wrote “Should shoot the pieces of shit” and “You wanna act like pathetic dogs, you should get put down like a pathetic dog.” Then there was “Kill their children,” and “only good ni**** is a dead ni****.”Footnote 5 Adding vilification and dehumanization presumably helped commenters rationalize their calls for murder, consistent with psychology’s mechanisms of moral disengagement (Bandura et al., Reference Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara and Pastorelli1996).

The messages coded as targeting police were generally less evocative. One said “Too many innocent people killed by cops. Time to overthrow them and make them wish they never gotten a job that can allow them to be murders,” and another wrote “Fuck this government. It’s time for a revolution.” Posts about harm against other commenters included “You angry whit bitch, kill yaself. #BlackLivesMatter,” and “Sara, let’s run your hillbilly ass over.” Explicit calls for non-violence included “Baton Rouge, please be safe and peaceful” and many that invoked religious prayers and scriptures, including “praying for peace and justice,” and “blessed are the peacemakers.” Some peaceful language seemed to be about general well-being, while other examples like the following seemed to be motivated by opposition to the protests: “Keep law enforcement safe. Place your power and miraculous love around them in avail of your protection. Please Jesus I pray. Many pray for your peace to come into the world, your world Jesus.”

We also coded comments that “generally seem intended to reduce the conflict,” including appeals for peace. In addition to the explicit non-violence examples provided, many examples are divisive in a way that protesters and their allies recognize, but that others may not, including “All Lives Matter.” Many others are openly supportive of the police in a way that pointedly excludes protesters from a sphere of concern, including “prayers for BRPD” and “Cops Lives Matter.”

We examine four other categories of enflaming comments: insults, negativity toward a specific racial group, calls for more (or less) police use of force, and expressions justifying Alton Sterling’s killing. Insults included “a bunch of jackass on the comments,” “racist cowards behind a keyboard,” and “225 fuck police brpd,” referencing the city’s area code. In sharp counterpoint to some of the “reducing conflict” codes, many other coders recognized “All Lives Matter” as an insult. Infantilization is also frequent—“pull up your pants” and “poor baby”—along with dehumanization, explicit by race or not: “Bunch of ignorant subhumans.” Negativity toward a specific racial group included a range of derogatory and violent statements, including “purge all the blacks,” “should all be locked up in the zoo with the other animals,” and “kill all whites.”

Calls for police violence included “police need to start busting skulls” and “have fire truck spray them.” Calls for less police violence included this mixed message: “All lives matter. Black on black needs to stop. Police and those of authority need not use unnecessary force. If no justice there will not be any peace…” Other cases of “less force” are more general, like “Jesus come get me now. I need some peace and unity,” which sounds like the non-violent and deescalating categories provided earlier.

As before, we combined the two MTurk ratings for each comment into a dichotomous measure for each comment trait—coder agreement on the trait’s presence (1), agreement on absence (0). For the multivariate portion of our analysis, that approach produces conservative estimates, given that any poor coding will add noise to the tests. We also pool any violence advocacy into an umbrella measure and any derogatory comments about either race into another omnibus measure.

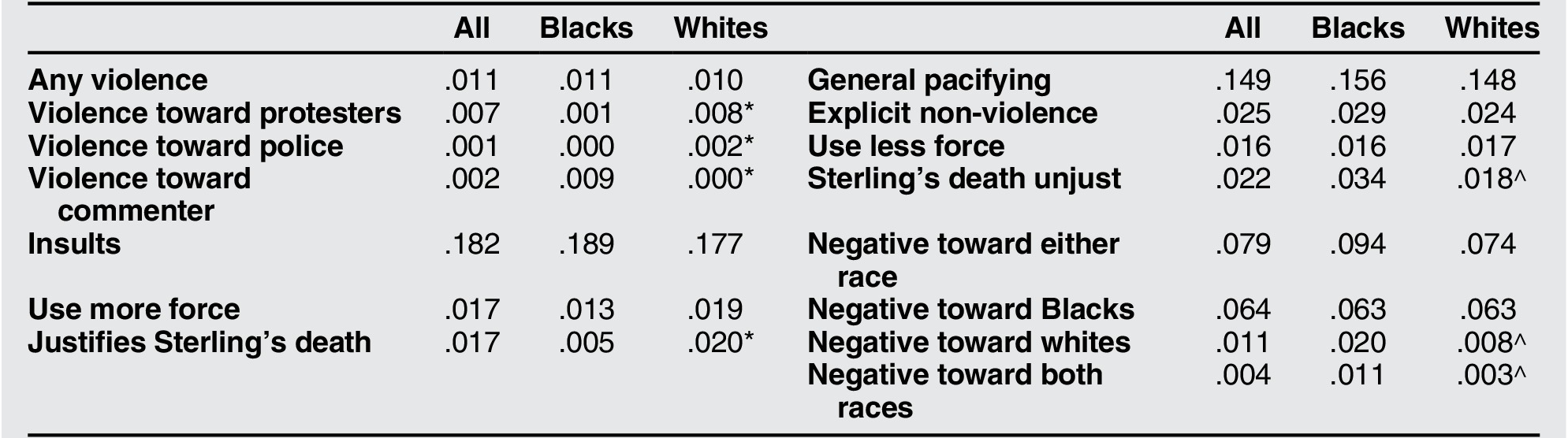

Table 4 presents proportions for each message trait among all comments relevant to the live protests, first for all comments and then by race. Racial differences appear muted here because the vast majority of comments are not related to the particular individual category under analysis. However, several racial gaps are statistically distinct.

Table 4 Proportions of enflaming and pacifying Facebook Live protest comments

Note: Cells present proportions among relevant comments, standard deviations in parentheses. “Any violence” is the sum of the next three categories, as is “negative toward either race.” All N=2670. Blacks N=555. Whites N=1632. White proportions are statistically distinct from Black proportions when indicated by * (p<.05) or ^ (p<.10).

To call these conversations inflammatory is an understatement. Nearly one in five comments contained insults, almost 10% were racially derogatory, 2% called for more violence by police, and 1% called for violence by others. Those latter calls for violence mostly targeted protesters (twenty comments total) rather than police or other commenters (four and five comments, respectively). Thirteen of the violent comments toward protesters were from whites, versus one from a Black commenter; none of the violent comments toward police were made by Blacks. Those violent disparities are far greater than the 3-to-1 ration in white comments versus Black comments. Whites rationalized a legal system of police violence focused disproportionately on their Black neighbors, but they also advocated for vigilante violence against local Black protesters too. That strategy combining legal and mob violence is consistent with a long history of that combination in violently maintaining white supremacy in Louisiana.

The vast majority of negative racial comments disparaged Blacks—7% of all comments, including those against both races. Only 1.5% targeted whites. These results affirm our expectation that Black Louisianans collectively received the brunt of the explicitly racial hostility, targeted by nearly five times as many derogatory comments as those targeting whites. The expert coder found similar levels and racial gaps in comments, but the differences by race were even starker for negative comments toward whites and toward Blacks, views of Sterling’s death, use of police force, and violence toward protesters (refer to the online appendix). Even so, the comments by race show that neither group is monolithic, as we saw in table 2 survey results.

Correlates of Enflaming and Pacifying Comments

Next, we estimate multivariate OLS models to identify the traits that correspond with inflammatory and pacifying comments. Because the frequency of traits is low, we recode our outcomes to be 0 or 100 instead of 0 or 1. This avoids coefficients with several decimal places and rounding that obscures relationships but does not otherwise affect the tests. Thus, if a predictor has a coefficient of 1.0, that equals a one percentage point increase in the rate.

We model comment traits as a function of commenter traits and other beliefs that their comments convey. Naturally, we already know of differences by race that reflect general support for police violence among white Louisianans and Black support for protesters, but we also expect that some commenter and comment traits may operate in opposite directions by race, and so we produce separate models for the two groups. For commenters, we focus on sex, college attendance, marriage status, local residence in or around Baton Rouge, and Christian identification. For example, public profiles avowing Christianity may lead to more calls for peace and non-violence in both races based on scripture and non-violent civil rights activism rooted in the church, or it may produce more militancy among whites in keeping with white Christian commitments to the racial order in the South (Harvey Reference Harvey2016).Footnote 6

For comment traits, we examine insults, racial derogation, and views on the (in)justice of Sterling’s death. We also model comment length, since longer comments have more potential to include content that fits multiple coding categories. We expect insults to correspond with violent advocacy, consistent with general aggression models (Anderson and Bushman Reference Anderson and Bushman2002). We expect racial derogation to correspond with support for force against the derogated group (or its enforcers, the police), and we expect the same given statements about Sterling’s killing. In models predicting violence or use of force, we exclude the other factors directly invoking force to avoid partly tautological estimates. Results were generally similar for additional models estimated separately by race (refer to the online appendix), though we note a few key exceptions below.

We begin with aggressive expressions, presented in table 5. The online appendix includes models for all comments together. For commenter correlates, we find that white women were significantly less likely than white men to express violence toward any target and especially toward protesters. Women of both races were less likely to use insulting language, though the difference is only significant for white women despite the larger magnitude for Black women. White Christians (publicly avowed) were marginally more likely to support violence against protesters, all else equal, while public Christian belief was unrelated to violent rhetoric among Blacks. Black Christians were marginally more likely to deploy insults than other Black commenters, while there was no significant religious difference among whites. Black Christians were also significantly less likely to advocate for more force against protesters. College education and living close to the protests did not have much relation to aggressive expressions.

Table 5 OLS Models Predicting Aggressive Posts by Commenter & Comment Traits

Note: OLS coefficients, robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by Facebook ID. A 1.0 coefficient equals a 1 percentage point change in the rate of the outcome. * p<.05, ^ p<.10 (two-sided)

Attitudes expressed in the comments themselves generally had stronger relationships with aggressive message content than demographic traits, which makes sense. People who made negative remarks about their own racial group were significantly less likely to advocate violence. This held for four of five outcomes among whites and three of five among Blacks. In other words, those cross-pressures seem to have reduced aggressive motivations, consistent with broader theories of political conflict. Insulting comments corresponded with more violence directed against protesters by police and by citizens among whites but not Blacks, and longer comments also tended to include more aggressiveness, especially among whites.

Next, we consider the inverse: comments against violence and the use of force. Table 6 presents the results. We exclude evaluations of Sterling’s killing for the use of police force model for being too close to the outcome. White women were marginally more likely to make explicit calls for non-violence, on average, and they were significantly more likely to make generally pacifying comments. College educated people of both races were less likely to call for less police force, as were Black Christians. Local whites were marginally less likely to explicitly call for non-violence than other whites.

Table 6 OLS models predicting pacifying posts by commenter and comment traits

Note: OLS coefficients, robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by Facebook ID. A 1.0 coefficient equals a 1 percentage point change in the rate of the outcome. * p<.05, ^ p<.10 (two-sided)

Insulting comments were less generally pacifying for both racial groups. Derogating comments against one’s own racial group were associated with fewer calming calls across most of these outcomes, so the reduced aggressive responses among this group are not matched by more calming responses—they are simply less likely to express sentiments in either direction. Derogating comments against any racial group tended to reduce expressions that Sterling’s death was unjust among Blacks and whites. Longer comments were more likely to explicitly advocate non-violence and to call for less use of force by police.

Lastly, we consider racial derogation in table 7. We exclude insults as a predictor in these models because it is too closely related to the outcomes, given that a large portion of insults were racial in nature. Black women were significantly less likely to make negative comments about whites compared to Black men. White women were as negative toward Blacks as white men were. Black Christians were less likely to derogate whites, while white Christianity only expressed less negativity toward both races together. Comments on Sterling’s death predict negative expressions about Blacks—more (less) negative views of Blacks when comments justify Sterling’s death more (less).

Table 7 OLS models predicting racial derogation by commenter and comment traits

Note: OLS coefficients, robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by Facebook ID. A 1.0 coefficient equals a 1 percentage point change in the rate of the outcome. * p<.05, ^ p<.10 (two-sided)

In sum, we find several results supporting our expectations for correlates of enflaming and pacifying comments, though the links often differed by the commenter’s race. Black women were less likely to make aggressive and violent comments, and white women were more likely to write pacifying or explicitly non-violent messages. Public expressions of Christian faith in profiles had a mixed relationship—it increased white support for violence against protesters and Black use of insults, while also reducing racial derogation among commenters of both races. Attitudinal message content predicted aggression, hostility, and de-escalation. In particular, insults corresponded with more white calls for violence against protesters and less pacifying content in Black and white comments.

Results on Social Support through Digital Likes

How did the highly heterogeneous audience respond to these comments? The content that attracts likes from some people might be distasteful to others and a comment could generate a like based on part of its content rather than the totality of its message. As a result, the process by which likes are generated is a bit of a mess. Nonetheless, we seek to identify systematic aspects of comments and commenters that attracted more favorable engagement from the audience.

Of particular interest is how some commenters and comments may gain more social support as a result of their identities, the content of their messages, or some combination. Most obviously, white commenters may receive more likes from majority-white commenters. In a different way, violent and racially derogatory comments may be penalized in the form of fewer likes, but only to the extent those social norms are upheld here (Valentino, Neuner, and Vandenbroek Reference Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek2018)—and, of course, those norms could be unevenly applied.

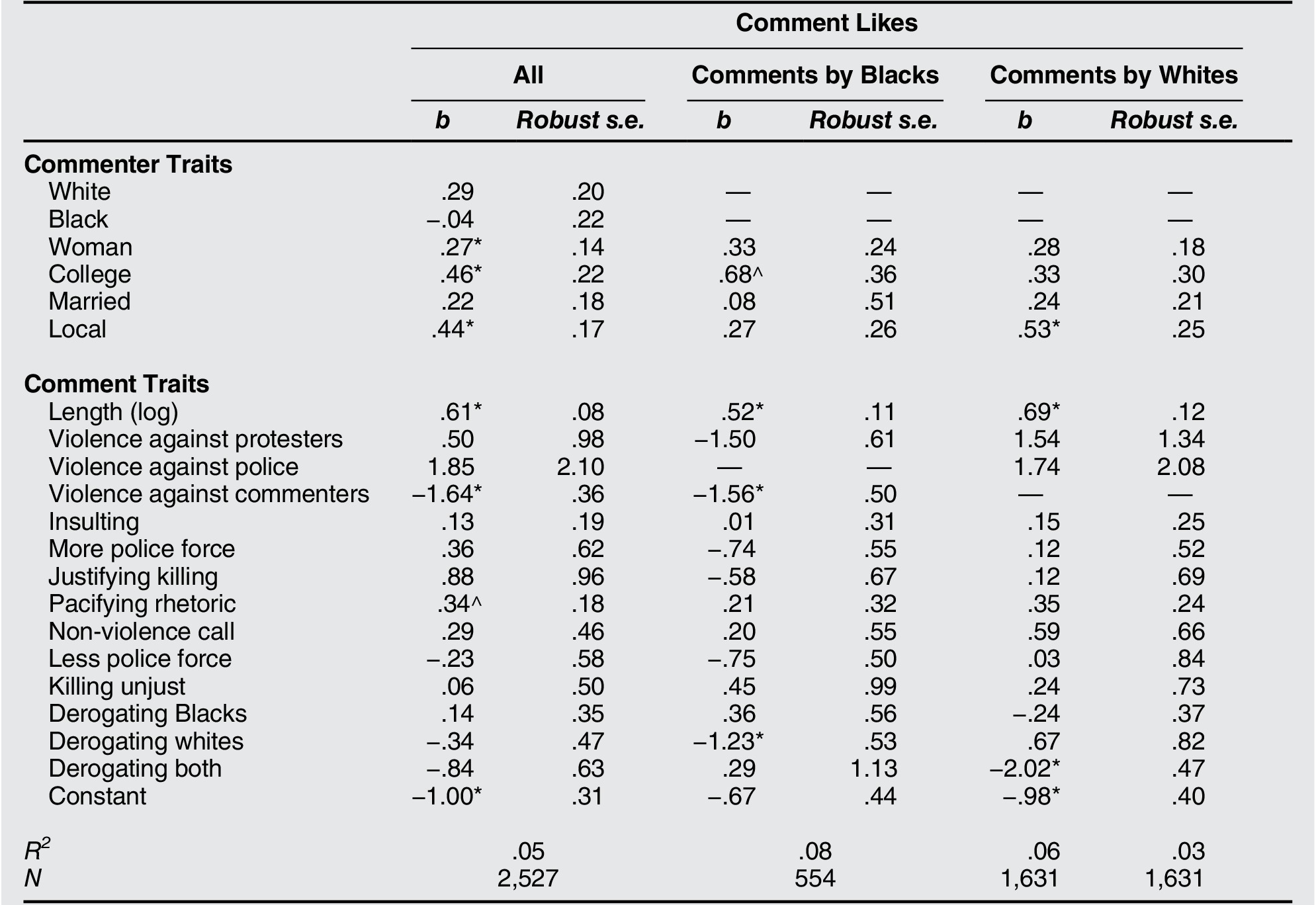

We estimate attributes of messages and messengers simultaneously to avoid misattributing the factors that draw likes to the correlates of predominant factors, but we also present commenter and comment models separately for additional views of the relationships. Likes on relevant comments ranged from 0 to 39, averaging 1.8 per comment. We estimate OLS models with robust standard errors clustered by individual Facebook users in table 8.

Table 8 OLS model predicting “Likes” by commenter and comment traits

Note: OLS coefficients with robust standard errors, clustered by Facebook ID. * p<.05, ^ p<.10 (two-sided)

We begin with visible traits of the commenters inferred from names and profile pictures. Women’s comments were more popular than men’s by about one-quarter point. Education may or may not be reflected in the formal quality of comments, but commenters who indicated they had attended college on their profile received half an extra like in any case. Comments from people who lived in or immediately around Baton Rouge received more likes, too, perhaps because their comments revealed more local familiarity or perhaps their proximity motivated different kinds of comments than non-local people. These patterns are generally similar by race. In contrast, people who listed their relationship status as married were no likelier to receive likes, and the estimate of more likes for white commenters did not reach statistical significance.

Moving to comment traits, we see that longer tweets received significantly more likes. Beyond that difference in form, pacifying comments drew marginally more likes. Violent rhetoric against other commenters by Black people significantly reduced social support by about 1.5 likes, and comments by Black people that disparaged whites received significantly fewer likes too. Comments by whites that disparaged people from both races together, averaging two fewer likes, but white commenters faced no penalty for disparaging Blacks or calling for violence against protesters. In fact, white calls for violence against protesters is estimated as receiving 1.5 more likes, but that difference is not statistically significant.

In sum, while evaluating audience reactions to these messages, we found more positive feedback to comments by women, locals, college graduates, and pacifying comments, and more negative feedback for violent and racially derogatory comments by Black commenters, with no penalty for similar white comments. That partly reflects the demographic balance of participants in the conversation, but it also tells us about how social norms against violence and vitriolic racial language are unevenly policed. While Black commenters were socially penalized for that rhetoric, violent and racist comments by whites received no such penalty. That finding is consistent with recent research finding faltering norms against white expressions of explicit racism (Valentino, Neuner, and Vandenbroek Reference Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek2018). It is fitting that these racial disparities in social policing of discursive norms echo the racial disparity of disproportionate police violence against Black Americans that spurred the protests these locals watched digitally and fought over together.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this article, we set out to learn whether the contentious local online discussion surrounding the police killing of Alton Sterling and subsequent protests reflected the people of the city and state and their substantive views about race and policing. We also sought to document the extent of violent and inflammatory rhetoric that characterized that dialogue, identify its correlates, and analyze audience responses. The descriptive and correlational results illuminate social media functions in local politics, the influence of social position on participation in contentious digital dialogues, and political communication’s dual roles in strengthening and undermining democracy.

With a suite of methods to measure people’s traits and views online and in the community, we found surprising representativeness on most but not all dimensions. In particular, Facebook commenters largely matched local and state publics on race and sex, though not age. However, even the age divergence reflected differences in general Facebook usage nationwide rather than differences in engagement within this domain or locale.

These were local conversations—four in five had local connections—despite the potential for geographically distant participation. Sociopolitical views also seemed to broadly reflect local and statewide attitudes, to the extent we can compare across different expression types in which commenters brought their own frames (Walsh Reference Walsh2002). Overall, we find surprising correspondence between the people and views participating in this highly contentious dialogue and the people and views of the broader community. That result may be partly encouraging for those who worry about local participatory and expressive inequalities in politics by race (Michener Reference Michener2016; Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019; Weaver, Prowse, and Piston Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2020), embedded in broader national conversations on racial inequities and police-involved shootings.

On the other hand, the content of expression matters for democratic norms of non-violence and racial equality and the role of social position in breaking the norms. First, we found a high level of aggressive and threatening content, including open calls for violence, consistent with studies of live digital comments in election contexts (Ventura et al. Reference Ventura, Munger, McCabe and Chang2021). As expected, we also found asymmetries in racial hostility, with derogation against Blacks as a group far more prevalent than derogation against whites. That explicitly racist rhetoric reproduced the same tropes seen in historical manifestations of white supremacist rhetoric, representing Blacks as lazy, violent, and inhuman as part of an ongoing political-economic effort to strip their power—and sometimes kill them to accomplish that end (Gates Reference Gates2020; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). In short, public dialogue in this form exacerbated conflict rather than resolving it (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1983).

Who fans these flames, and who tries to douse the fire? Consistent with aggression research, women were generally less likely to make aggressive, violent, and negative racial comments about opposing groups, and they were more likely to write pacifying messages. Publicly avowed white Christians were likelier to support violence against protesters and less likely to call for less force by police against them. Derogatory racial comments and views about Sterling’s killing predicted aggression, hostility, and de-escalation, and insults corresponded with aggressive content too. Finally, our analysis of digital “likes” showed more support for comments by women, college-educated people, and locals. Pacifying calls were also more popular. Violent and racially hostile comments by Blacks received significantly fewer likes, while similar content from whites went unpenalized in a notable racial disparity in reinforcing social norms against corrosive language.

Our studies reveal a more violent and racially repugnant public dialogue than is commonly seen in political communication scholarship—further still from idealized models of local public discussion. In contrast, these languages are familiar in works focused on white supremacy and racial violence in America, and in the lived experiences of Black Americans. Here, we saw those ancient white claims starkly reproduced in digital form. Far from being outliers, our evidence shows these commenters represented their city and state well. That should motivate a reevaluation of the bounds we ascribe to public opinion, expression, and action. The extremes made visible give no sign that white Southerners (among others) respect democratic norms of non-violence and racial equality in the twenty-first century. Likewise, Black Americans and their allies appear unlikely to quietly tolerate white rejection of multiracial democracy.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722000123.

1. Methods and Robustness Details

Methods Details

2. Facebook Profile Coding

3. Mechanical Turk Comment Coding

4. U.S. Census Data on Louisiana and Metro Baton Rouge

5. Louisiana and Metro Baton Rouge Survey

6. Robustness tests with Local Expert Codes

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University for supporting this project with funds from the William K. “Bill” Carville Professorship. Thanks to Mike Henderson and Martin Johnson for coordinating the 2016 Community Resilience survey in Louisiana, funded by donations to the Manship School. An early version of the representation results was presented at the 2019 Midwest Political Science Association conference. Thanks to discussant Seth Goldman and participants for their feedback.