INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a neuropsychiatric disorder that is characterized by a disturbance of consciousness (arousal and awareness), attention, cognition, and perception (e.g., perceptual disturbances and delusions). Delirium has an abrupt onset and fluctuating course, and it usually has an underlying physiological etiology (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Other frequent symptoms of delirium include various mood changes, sleep–wake cycle disturbances, psychomotor abnormalities, and language abnormalities (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, O'Hanlon and O'Mahony2000).

Delirium has been traditionally classified into subtypes based on either arousal disturbance, or change in motoric activity. Lipowski was the first to identify delirium subtypes based on levels of alertness/ arousal (Lipowski, Reference Lipowski1983). The formal definitions of these subtypes were hypoalert–hypoactive and hyperalert–hyperactive (Lipowski, Reference Lipowski1989), suggesting an early difficulty in separating arousal disturbance from motoric activity in classifying delirium subtypes. By contrast, O’Keeffe and Meagher based their classification of delirium primarily on motoric changes (O'Keeffe & Lavan, Reference O'Keefe and Lavan1997; Meagher & Trzepacz, Reference Meagher and Trzepacz2000; Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, O'Hanlon and O'Mahony2000, Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a, Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b). Researchers later introduced a mixed subtype to categorize delirium with both hypo- and hyperactive symptoms (Koponen et al., Reference Koponen, Partanen and Paakkonen1989; Liptzin & Levkoff, Reference Liptzin and Levkoff1992; Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, O'Hanlon, O'Mahony and Casey1996). Camus et al. (Reference Camus, Burtin and Simeone2000) identified two symptom clusters of delirium: the hypoactive type was characterized by decreased reactivity, motor and speech retardation, and facial inexpressiveness; the hyperactive type was characterized by agitation, hyperreactivity, aggressiveness, perceptual disturbances, and delusions. Ultimately, the current classification favors subtyping by psychomotor behavior into a hypoactive and hyperactive subtype (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a, Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b).

Several studies have previously sought to describe differences in frequency and phenomenology between the subtypes. A review of the major studies evaluating the subtypes of delirium (Stagno et al., Reference Stagno, Gibson and Breitbart2004) found a range of prevalence of 15–79% for the hypoactive type, 6–46% for the hyperactive type, and 11–55% for the mixed type. Because different studies used a variety of definitions for delirium subtypes, it is difficult to compare findings of different authors.

Regarding phenomenology, Ross and colleagues, using an arousal subtype classification, found that perceptual disturbances (i.e. hallucinations) and delusions are significantly more common in hyperactive or “activated” delirium (67% and 50%, respectively) than in hypoactive or “somnolent” delirium (3% perceptual disturbances–hallucinations, 3% delusions, respectively) (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Peyser, Shapiro and Folstein1991). Ross and colleagues confounded arousal and motoric elements of phenomenology, and utilized poor measures of the phenomenology of delirium. No recent studies of phenomenological differences between the subtypes of delirium have been conducted using better measures of delirium phenomenology (e.g., Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale [MDAS]) according to a clear motoric abnormality classification approach. Based on our clinical observation in treating delirium in physically ill patients over the previous decade, we hypothesized that the differences in the prevalence of perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations) and delusions based on delirium subtypes would not be as dramatically different as previously reported (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Peyser, Shapiro and Folstein1991) (i.e., perceptual disturbances and delusions are probably more common in hypoactive delirium than previously documented).

METHODS

Subjects

All participants were Memorial Hospital inpatients receiving cancer care who were referred for delirium management to the Memorial Sloan- Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Psychiatry Service between July and November 2000. Clinical data were recorded in an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved MSKCC Psychiatry Service Clinical Delirium Database. Data recorded included serial MDAS ratings, etiologies of delirium, medications and dosages of neuroleptics utilized to treat the symptoms of delirium, adverse events, and comorbid medical conditions.

The criteria used for eligibility to be considered for the delirium database were broad; patients who met the DSM-IV criteria for delirium were deemed candidates for the database. Exclusion criteria included objections from the patient or family to psychiatric intervention, inability to comply with delirium ratings, and severe agitation interfering with full assessment. All patients and families gave verbal consent to be evaluated and treated for delirium. In patients with limited capacity to provide consent because of delirium, the patient's primary caregiver provided verbal consent with the patient's assent to treatment.

Measures

We conducted an analysis of our delirium database based on the ten MDAS items (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Roth1997). Scale items assess disturbance in arousal (i.e., reduced level of consciousness); as well as several areas of cognitive functioning (memory, attention, orientation, and disturbances in thinking); psychomotor activity (hypoactive, hyperactive, mixed); perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations); delusions; and sleep–wake cycle disturbance. Symptoms are rated as absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) on the MDAS. Delirium subtype classifications were based on motoric activity:MDAS item no. 9 (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, O'Hanlon and O'Mahony2000, Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a, Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b). Because of the ongoing evolution of classifying delirium subtypes, we classified all patients into either the hypoactive or hyperactive subtypes, combining both mixed and hyperactive subtypes and classifying them as “hyperactive.” MDAS scores categorized delirium as follows: mild delirium (MDAS < 16), moderate delirium (MDAS 16–22), and severe delirium (MDAS > 22). The Karnofsky Scale of Performance Status (KPS) was used to indicate physical performance ability (Karnofsky, Reference Karnofsky, Burchenal and Macleod1949).

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the data was performed with the SPSS 16 statistical software package for Windows. The data contained interval, ordinal, and categorical variables. For pairwise comparison of two independent samples on an ordinal data scale we used the Wilcoxon test. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test for three independent samples on an ordinal scale. Categorical data were analyzed using Pearson's χ2; logistic regression analysis was then performed in order to calculate odds ratios (OR). Exact tests were used when applicable.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

We evaluated 100 patients from our delirium database. The mean age of patients was 58.36 years (19–89, SD 16.65). Gender distribution was equal, with 51.5% of patients being male and 48.5% being female. The study population was predominantly Caucasian (67%), but also included African-American (19%), Hispanic (10%), Asian (2%) and other ethnicities (2%). Cancer diagnoses included lung cancer (21%), gastrointestinal cancer (14%), lymphoma (13%), breast cancer (11%), head and neck cancer (6%), ovarian cancer and brain cancer (3%), and other malignancies (27%). Disease stage was classified as metastatic (78.8%), localized (16.2%), or terminal (5.1%). Brain metastases were present in 24%; 18% had a history of dementia. The etiologies of delirium were diverse, including: opioids 63.4%, corticosteroids 30.1%, hypoxia 28%, dehydration 12.9%, infection 41%, and other etiologies 12.9%. Mean delirium severity as measured by MDAS was 19.17 (14–30, SD 3.18). Moderate delirium was present in 70.6% of patients, 16.7% had severe delirium, and 11.8% had mild delirium. The mean KPS score was 35.5 (20–50, SD 7.70).

Hypoactive delirium was present in 53% of patients, and hyperactive delirium was present in 47%. There were no significant differences between delirium subtypes based on age: the mean age in patients with hypoactive delirium was 60.7 (26–89, SD 17.77) years, and the mean age in patients with hyperactive delirium was 55.9 (19–84, SD 15.21) years; or gender: 54.7% of patients were male and 45.3% were female in the hypoactive group, and 46.8% were male and 53.2% were female in the hyperactive group. There was no significant difference between the mean MDAS total scores (reflecting likelihood of delirium diagnosis as well as severity of delirium) for hypoactive versus hyperactive delirium. Mean MDAS scores were 18.67 (14–25, SD 2.98) in hypoactive delirium and 19.70 (14–30, SD 3.38) in hyperactive delirium. There was also no significant difference in KPS between the two delirium subtypes, with a mean KPS of 35.5 (20–50, SD 7.5) in hypoactive delirium and 35.5 (20-50, SD 8.0) in hyperactive delirium.

Phenomenological Differences Between Hyperactive and Hypoactive Delirium Subtypes

Prevalence of Perceptual Disturbances and Delusions Based on Delirium Subtypes

Perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations) were present in 50.9% of patients with hypoactive delirium and 70.2% of patients with hyperactive delirium. Delusions were present in 43.4% of patients with hypoactive delirium and 78.7% patients with hyperactive delirium. Both perceptual disturbances and delusions are significantly more prevalent in the hyperactive subtype of delirium (χ2 3.85, d(f) = 1, p < 0.05, OR 2.27; χ2 12.95, d(f) = 1, p < 0.001, OR 12.95 respectively) (Table 1). When examining individual MDAS items of only moderate-to-severe intensity (Table 2) the differences in prevalence of perceptual disturbances and delusions between hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes of delirium become more pronounced. Perceptual disturbances of moderate-to-severe intensity occurred in 53.2% of patients with hyperactive delirium compared to 17% of patients with hypoactive delirium (χ2 14.56, d(f) = 1, p < 0.001, OR 5.56). Delusions of moderate-to-severe intensity occurred in 38.3% of patients with hyperactive delirium and in 18.9% of patients with hypoactive delirium and (χ2 4.67, d(f) = 1, p < 0.05, OR 2.67). The presence of moderate-to-severe perceptual disturbances and delusions was independent of the presence of moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment in the delirium cohort. The presence of moderate-to-severe perceptual disturbances and delusions was, however, significantly correlated with the presence of moderate-to-severe disturbance of consciousness/arousal (reduced consciousness) (χ2 6.41, d(f) = 1, p < 0.05 and χ2 9.52, d(f) = 1, p < 0.01) and impaired attention (χ2 4.81, d(f) = 1, p < 0.05 and χ2 5.64, d(f) = 1, p < 0.05) in the entire delirium cohort.

Table 1. Presence of delirium symptoms in hyperactive vs, hypoactive subtypes in percentages

*χ2: p < 0.05; ***χ2: p < 0.001.

Table 2. Presence of moderate and severe delirium symptoms in hyperactive vs. hypoactive subtypes in percentages

*χ2: p < 0.05; ***χ2: p < 0.001.

Severity of Delirium Symptoms in Hyperactive versus Hypoactive Subtypes

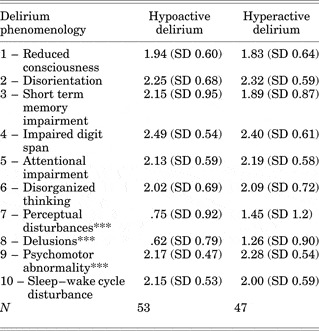

In both subtypes of delirium, the cognitive domains (MDAS item nos. 2–6) were most severely impaired based on mean MDAS item scores (Table 3). There were no significant differences between hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes of delirium in respect to the severity of arousal disturbance, disorientation, short-term memory impairment, attention/concentration deficits, disorganization, and sleep–wake cycle disturbance (MDAS item nos. 1–6 and 10, respectively)

Table 3. Delirium phenomenology in hypoactive vs. hyperactive delirium: Mean MDAS scores

***Mann–Whitney U: p < 0.001.

Hypoactive and hyperactive delirium subtypes differed significantly in the severity of perceptual disturbances (Mann–Whitney U: 821.50, z = −3.07, p < 0.01) delusions (Mann–Whitney U: 763.50, z = −3.53, p < 0.001), and psychomotor abnormality (Mann– Whitney U: 17.00, z = −8.91, p < 0.001) (Table 3). The mean MDAS item severity scores for perceptual disturbances were 0.75 in hypoactive delirium and 1.45 in hyperactive delirium. The mean MDAS item severity scores for delusions were 0.62 for hypoactive delirium and 1.26 for hyperactive delirium. Therefore, perceptual disturbances and delusions are significantly more severe in the hyperactive subtype of delirium.

The severity of perceptual disturbances and delusions within each delirium subtype was independent of overall delirium severity (Table 4). However, severity of the following phenomena (MDAS items) increased as overall delirium severity increased: arousal disturbance, disorientation, short-term memory impairment, concentration and attention impairment, and disorganization, as well as sleep–wake cycle disturbance in patients with hypoactive delirium and psychomotor abnormality in patients with hyperactive delirium. Therefore, the severity of perceptual disturbances and delusions appeared to be independent of delirium severity in both the hyperactive and hypoactive subtype of delirium.

Table 4. Range of severity of mean MDAS items correlated with hyperactive vs hypoactive subtypes of delirium

*Kruskal–Wallis: p < 0.05; ***Kruskal–Wallis: p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the differences in phenomenology between hypoactive and hyperactive subtypes of delirium has great potential in influencing the assessment and management of delirium in the medical hospital. Prior studies by our research group at MSKCC have emphasized the lack of differences in both morbidity and treatment responsiveness to antipsychotic medications between patients with hypoactive delirium and those with hyperactive delirium (Platt et al., Reference Platt, Breitbart and Smith1994; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Gibson and Tremblay2002). This most recent examination of the phenomenological differences between hypoactive and hyperactive delirium, in a cohort of 100 delirious hospitalized cancer patients, sheds new light on misconceptions perpetuated by early studies of delirium subtype phenomenology that suggested dramatic differences, particularly in the area of the prevalence of perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations) and delusions. These early reports (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Peyser, Shapiro and Folstein1991) suggested very low prevalence (~3%) of hallucinations and delusions, therefore resulting in a bias against using antipsychotic medications in the management of the symptoms of hypoactive delirium. The findings of this study dramatically underscore the growing understanding that perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations) and delusions are in fact very common in hypoactive delirium.

In summary, the findings of this study demonstrated that hypoactive delirium is as common as hyperactive delirium (53% vs. 47%, respectively), and that no significant differences between delirium subtypes could be found based on age, gender, level of physical performance, or delirium severity. In both subtypes of delirium, cognitive impairment was the most prominent and severe domain of delirium within our sample cohort, similar to the findings of Meagher (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2007). No significant differences were found between hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes of delirium in respect to the presence or severity of arousal disturbance, disorientation, short-term memory impairment, attention/concentration deficits, disorganization, and sleep–wake cycle disturbance. Most important, we found a much less dramatic difference in the prevalence of hallucinations and delusions between hypoactive and hyperactive subtypes of delirium. Although still more common in hyperactive delirium, perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations) were present in 50.9% of patients with hypoactive delirium, compared to 70.2% of patients with hyperactive delirium. Delusions were also highly prevalent in hypoactive delirium, with delusions present in 43.4% of patients with hypoactive delirium versus 78.7% patients with hyperactive delirium. However, moderate-to-severe perceptual disturbances and delusions remain significantly more prevalent in hyperactive delirium.

Although our study has confirmed certain earlier findings in studies of delirium phenomenology based of subtype, the most novel and clinically relevant new finding is the demonstration that perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations) and delusions are in fact much more prevalent in hypoactive delirium than previously appreciated or reported. Our findings regarding the prevalence of arousal disturbance, disorientation, cognitive impairment, psychomotor behavior abnormality, and sleep–wake cycle disturbance are similar to those of previous studies (Turkel et al., Reference Turkel, Trzepacz and Tavare2006) with respect to moderate and severe symptomatology. Our study shows higher prevalence rates of perceptual disturbances and delusions than Webster's (Webster & Holroyd, Reference Webster and Holroyd2000). Additionally our findings regarding cognitive impairment in the phenomenology of delirium are quite consistent with Meagher's findings (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2007).

This study has several limitations. The design of the study was cross-sectional, therefore the evolution of symptoms over delirium severity could not be determined. Longitudinal studies have suggested that psychomotor abnormalities and sleep–wake cycle disturbances present mainly in the early course of delirium (Fann et al., Reference Fann, Alfano and Burington2005), whereas disorientation, inattention, impaired memory, and sleep disturbances present throughout the course of delirium (Levkoff et al., Reference Levkoff, Liptzin and Evans1994; McCusker et al., Reference McCusker, Cole and Dendukuri2003). Research regarding delirium subtypes has vacillated between using arousal disturbances and psychmotor abnormalities as the basis of subtype classification. This has led to some confusion in interpreting the generalizability and comparability of various studies (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Peyser, Shapiro and Folstein1991; Meagher & Trzepacz, Reference Meagher and Trzepacz2000; Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b). The MDAS (which we used) uses the motoric subtype classification of delirium. Other current researchers approach delirium subtypes by using motoric abnormalities as a basis for subtype classification (Meagher & Trzepacz, Reference Meagher and Trzepacz2000; Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008a, Reference Meagher, Moran and Raju2008b). The MDAS is a widely used rating scale for delirium (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Roth1997; Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Nekolaichuk and Gagnon2000). We analyzed the prevalence of the MDAS items in order to illustrate the frequency of different symptoms in delirium and its subtypes. Although we used item no. 9 (psychomotor abnormality) as the basis for classifying delirium subtypes, we did consider also analyzing the data from this cohort by using arousal disturbance as a basis for subtype classification. We were limited in our ability to do so because the MDAS only allows for rating the severity of arousal disturbance in the negative direction (i.e., reduction in arousal and consciousness) and does not allow for positive direction ratings of hyperarousal or hypervigilance. We are planning to consider adapting the MDAS to allow for such a range of ratings in the future, so that we may examine arousal disturbance and its applicability as a basis for subtype classification.

We should also mention the issue of cognitive deficits as a potential limitation of delirium ratings within the sample. As previously mentioned, patients with cognitive deficits were not excluded from this study. Brain metastases were present in 24% of patients, and 18% had a history of dementia. The effect of these patients on the overall results is likely to be negligible, because excluding patients with cognitive deficits in our sample did not alter the results. Dementia does not appear to alter delirium phenomenology (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Mulsant and Amanda1998; Boettger et al., Reference Boettger, Passik and Breitbart2009). The etiology of delirium in our sample population of cancer patients was multifactorial and included medications with psychotropic effect. Further studies are needed to understand the impact of etiological factors on the presentation of delirium.

In summary, contrary to earlier studies, which indicated extremely low prevalence rates of perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations) and delusion in hypoactive delirium, our study demonstrates that the prevalence of perceptual disturbances and delusions in hypoactive delirium is much higher than previously reported (50.9% and 43.4%, respectively), and is deserving of clinical attention and intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was presented, in part, at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, Miami, Florida, November 14–18, 2008. The authors thank Paul Campion for his editorial assistance. In addition, the authors thank the patients and their families who participated in this study.