The campaign for family allowances in interwar Britain has primarily been understood as a movement concerned with the alleviation of child poverty and the struggle for women's equality. It drew the core of its support from socialists, feminists, liberals and other assorted ‘progressives’. However, as the literature on this much-studied campaign also shows, family allowances were discussed, debated, and at times defended by participants in the eugenics movement.Footnote 1

It is not entirely surprising that certain ‘progressive’ causes found a sympathetic hearing within the eugenics movement. Historians have long dismissed the notion that eugenics in early twentieth-century Britain was the sole preserve of the ultra-conservative right wing. The ideal of scientifically managed racial betterment appealed to thinkers across the political spectrum, whilst in the 1930s the Eugenics Society – the institutional centre of the British movement – became increasingly involved in leftist-tinged discussions over social reform and state planning.Footnote 2 However, recognition that the eugenics movement had a ‘progressive’ streak goes only so far in explaining how and why the issue of family allowances made its way onto the Eugenics Society's agenda.

From the mid-1920s through the mid-1930s, statistician and geneticist R.A. Fisher (1890–1962) was the most vocal supporter of family allowances within the Eugenics Society's ranks. A ‘progressive’, however, he was not; Fisher supported family allowances despite – not because of – the policy's ramifications for the causes of feminism and social justice. His support, as we shall see, was grounded in his rather idiosyncratic theorizing on the causes of national and racial decline. He appropriated the proposal of paying parents for dependent children, refashioning it as a potential means of stimulating reproduction among the eugenically ‘desirable’ middle and upper classes.

Fisher's name crops up occasionally in the historiography of the family allowances movement, identified as a notable supporter, though his specific reasons for and methods of promoting family allowances are usually left unexplored. Similarly, while historians interested in Fisher's scientific contributions have frequently reflected upon his support for eugenics more generally, there remains much work to be done in examining the specifics of his proposed interventions and his attempts at publicizing them. This essay deepens our understanding of Fisher's particular brand of eugenics by studying in detail how it was that he landed on family allowances as his preferred solution to dysgenic demographic trends. I then chart his struggles to find a sympathetic audience for his ideas, both within the Eugenics Society and beyond. In so doing, I highlight tensions in the aims of the parties involved, and clarify Fisher's standing with respect to the so-called ‘reform eugenics’ movement – a more scientifically sophisticated and progressively oriented strand of eugenical thinking which came to displace the more scientifically naive and politically reactionary ‘mainline’ eugenics movement of the 1910s and 1920s.Footnote 3 Fisher, a first-rate scientist and critic of some favoured mainliner methodologies, has often been lumped in with the ‘reformers’.Footnote 4 We will see, on the contrary, that Fisher's eugenical theory of civilizational decline was subjected to coordinated reformist attacks, and that the society's practical and political reorientations under the leadership of reform eugenist Carlos Blacker figured centrally in Fisher's retreat from the Eugenics Society through the latter 1930s.

Finally, and crucially, this essay challenges some long-held ideas regarding the reception, reading and influence of Fisher's 1930 ‘classic’, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. The book is renowned for its mathematical reconciliation of natural-selection theory with the new Mendelian genetics, for its pioneering analyses of evolution as a population-genetical phenomenon, and for its formative role in establishing the so-called ‘modern synthesis’ in evolutionary studies. Less celebrated are the book's final five chapters, in which Fisher sets out at length his theorizing on eugenics and the causes of racial decline. Fisher's latter-day scientific followers habitually downplay the significance of these chapters, and while historians of science often comment upon their presence within Fisher's masterwork, we know little about their reception and influence. The second half of this essay recovers the important role of The Genetical Theory and its ‘human’ chapters within Fisher's continued campaign for eugenic family allowances.

A marriage of convenience? Fisher and family allowances

Eleanor Florence Rathbone (1872–1946) was already a seasoned women's rights campaigner by the time her book The Disinherited Family: A Plea for the Endowment of the Family appeared in 1924.Footnote 5 Undeterred by defeat at the polls in the 1922 general election, she pushed once again for a national scheme of family allowances, a cause she had championed without success throughout the war. For Rathbone, allowances paid to mothers for each dependent child promised to combat poverty, whilst diverting national wealth into the hands of newly enfranchised women. Motherhood was vital work and should be remunerated accordingly.

Figure 1. Eleanor Florence Rathbone, 1930s, addressing a crowd at Trafalgar Square, London. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

As well as considerations of equality and social justice, Rathbone grounded her plea for family allowances in a probing economic analysis of extant wage systems. The way most organizations paid their employees, she pointed out, rested on the fallacious notion that wages should be set at a level appropriate for supporting the hypothetical ‘normal’ family. In reality, the number of dependents for whom wage earners had to provide varied widely, and thus so did a family's necessary expenditure. The well-intentioned principle of ‘equal pay for equal work’ resulted in bachelors with surplus wages burning holes in their pockets, whilst their colleagues struggled to adequately clothe, feed and educate their large families. Family allowances represented a fix which would distribute wealth equitably to account for the needs of dependent offspring, at once lifting millions of children out of poverty and ending the waste of paying for bachelors’ ‘phantom’ families.

Rathbone expected that her proposals would meet stiff resistance, and duly devoted a chapter of The Disinherited Family to anticipating and disarming ‘[t]he case of the opposition’. Eugenic circles threatened to be especially unsympathetic; those committed to racial advancement, Rathbone reasoned, might well (mis)understand her proposals as further inducements to overzealous breeding among ‘undesirable’ classes.Footnote 6 It will have come as a pleasant surprise, then, when a lengthy and largely positive review of The Disinherited Family appeared in the July 1924 number of the Eugenics Review, the official organ of Britain's national Eugenics Society.Footnote 7 The reviewer was a certain R.A. Fisher, a statistician of growing renown based at Rothamsted Experimental Station in Hertfordshire.

Fisher's admiration for Rathbone's book certainly did not stem from any feminist convictions. On the contrary, he complained of the book's suffragist ‘aroma’ and the ‘sex antagonism’ which left its author apparently unable to quote ‘a male opinion civilly, however closely his conclusions may agree with her own’.Footnote 8 Despite his obvious distaste for her style, Rathbone's proposals struck Fisher as being of the utmost eugenic importance. He would spend the next couple of decades attempting to bring colleagues, friends, politicians and the general public around to this same view.

Understanding why it was that Fisher was so taken with the idea of family allowances requires familiarizing ourselves with his particular, even idiosyncratic, brand of eugenics. Fisher had been a mathematics undergraduate at Cambridge when the 1911 Census drew fresh attention to Britain's ‘inverted’ birth rate, and, like many eugenists of his vintage, he was deeply concerned by the observation that the rapidly reproducing lower classes seemed to be contributing more than their share to the national stock. The reason Fisher and his eugenist peers found this demographic fact so worrying was their dual assumption that desirable moral and intellectual qualities had a significant hereditary component, and that these heritable traits were to be found disproportionately among the middle and upper classes. Unless the imbalance in the reproductive rates of the different classes could somehow be redressed, the quality of Britain's population was doomed to inexorable decline.Footnote 9

First in a 1912 address to his fellow undergraduate members of the Cambridge University Eugenics Society, and routinely thereafter, Fisher insisted that investigating the ‘cause and cure’ of the dysgenic birth rate was the eugenist's most pressing task.Footnote 10 Though a satisfactory ‘cure’ long eluded him, Fisher was soon convinced that he had isolated the underlying ‘cause’. The germ of the answer was to be found in the writings of the father of the eugenics movement, Francis Galton. In his Hereditary Genius, published in 1869, Galton had discussed at length the peculiar phenomenon of the extinction of hereditary peerages. Examining the lineages of notable families, he observed that male peers would often choose for a wife a wealthy heiress, presumably enticed by the promise of financial security. If these wives brought fortune, they all too often failed to produce a family. The very fact that these women were heiresses was a strong indicator that they sprang from unhealthy and infertile stock, which in turn explained why such unions were themselves so routinely childless. For Galton, the situation was disastrous: the inherited ability carried by distinguished men was being continually lost through their fruitless marriages to congenitally infertile women.

Fisher took Galton's theory of heiresses and generalized it, to explain not only Britain's inverted birth rate, but also the periodic collapse of all great civilizations throughout recorded history, from the Babylonians to the Romans.Footnote 11 Fisher's central Galtonian assumption, quite unorthodox among his peers, concerned the heritability of fertility. Most thinkers, in explaining the differing reproductive rates between social classes, cited divergences in environment and custom. Fisher, meanwhile, attributed the phenomenon to ‘nature’, rather than ‘nurture’. For him, fertility, just like any other trait, had a strong heritable component. From the physiological capacity of one's reproductive organs to the temperamental factors influencing the age one chooses to marry (earlier couplings create larger windows for childbearing) – all of these contributors to one's fecundity were, at least in part, inherited. The proximate cause of the comparatively low birth rate in society's upper strata was a preponderance in those classes of inherited factors making for low fertility.

Next, Fisher had to explain why it was that heritable reproductive capacity had come to be so tightly correlated with social position. His reasoning was that, under the conditions of modern society, those from small families – that is, those who were biologically relatively infertile – enjoyed a social and economic advantage. Parents with fewer children could afford to give a better start in life to the ones they had. At the same time, where small families were concerned, inherited wealth quickly became concentrated in the hands of fewer heirs. All of this led to greater upwards social mobility for those from small families. Through this process of ‘social selection’, the heritable factors making for relative infertility rose up through society's ranks and, through intermarriage, became coupled with the factors underlying eugenically desirable qualities such as intelligence and moral virtue. Over generations, the ‘natural endowments’ of the brightest and the best would be effectively bred out of the population. The result would be a terminal decline in the innate ‘quality’ of the population.

Fisher set out his theory of the cause of the dysgenic birth rate in various speeches and writings throughout the 1910s and early 1920s, but was never able, to his own satisfaction, to devise a practical eugenic solution to combat the damaging social selection of infertility.Footnote 12 It was obvious to him that some means was required of eliminating the ‘social advantage’ enjoyed by small, and infertile, families. Already in place was a system of income tax relief for middle-class families with children, and Fisher and the Eugenics Society lobbied government through the 1920s to increase the generosity of the scheme.Footnote 13 More, though, needed to be done, and reading Rathbone's Disinherited Family in 1924 convinced Fisher that family endowment, properly designed and implemented, was the most promising way forward. Payments to parents for each dependent child – either through a state scheme, or more realistically through equalization pools organized by individual employers or industries – could effectively equalize living standards with respect to family size, and thus remove the present premium on infertility, leaving innate ability as the sole determinant of social promotion. The steady, indirect sterilization of the eugenically worthier classes would be halted.

There was a problem, however, namely the ‘weakness of Miss Rathbone's eugenical interests’. The design of her scheme was based not upon the principles of racial improvement, but upon ideals of ‘social justice’ and ‘democratic sentiment’, leading her to suggest that allowances be fixed at the same absolute level for all earners, regardless of salary.Footnote 14 Fisher insisted that, in order to be truly eugenically effective, allowances should instead be proportional to income. He reasoned that higher earners – who also tended to be more eugenically desirable – spent more on the rearing of each of their children. The better-off must therefore be given a more generous allowance per child in order to offset their higher expenditures. Only in this way could the economic disincentive to childbearing be mitigated throughout all levels of society.

Keen to put the eugenic case for family allowances before the Eugenics Society, Fisher arranged for Rathbone to address a members’ meeting on 12 November 1924. Fisher's review of her Disinherited Family gave Rathbone fair warning that a eugenical audience might prefer to hear of proportional, rather than flat-rate, schemes. Though it clearly pained her to effectively bake class inequality into her proposal, she conceded in her speech to the society that, so long as there existed ‘exaggerated differences in the standard of life of different occupational classes’, family allowances must be ‘so graded as to bear a reasonable relation to the standard of life of the parents’.Footnote 15 Despite this concession, her address met a frosty reception. Discussants questioned the wisdom of paying allowances directly to the mother – a move which risked eroding the father's ‘sense of responsibility’ and his ‘social dignity’ – whilst some accused Rathbone of harbouring ambitions to turn Britain into a ‘socialistic State’.Footnote 16

The principal worry, however, was the potential for family allowances to stimulate a breeding boom at a time when many eugenists felt that the country, and the world, was already dangerously overpopulated.Footnote 17 A good number of the Eugenics Society members in Rathbone's audience that evening were also active in the Malthusian League (f. 1877), an organization which advocated birth control and family planning as means of keeping the population in check.Footnote 18 ‘There is one way and one way only to reduce misery’, explained one commentator on Rathbone's paper, ‘and that is to reduce the population’. Pro-natalist policies such as family allowances were simply out of the question. Fisher scrambled to Rathbone's defence, suggesting that only the fertility of the more desirable classes would be appreciably boosted, whilst attempting at length to dismiss the very notion that Britain was overpopulated.Footnote 19 His protests were in vain; when the issue of adopting an official position on family allowances came before the next month's Eugenics Society council meeting, it was decided to ‘express no opinion’ on the matter.Footnote 20

The Eugenics Society largely steered clear of the issue of family allowances throughout the 1920s, preferring to concentrate its lobbying efforts on the campaign for voluntary sterilization of the mentally ‘unfit’.Footnote 21 The fruits of Fisher's persistent pressure were meagre. In 1926, the society published a statement of its practical policy, which included a brief comment on family allowances. The clause simply stated the society's belief that within any family allowance scheme implemented by government or industry, ‘the benefit recovered per child should be directly proportional to the scale of earnings of the parents’.Footnote 22 Given fundamental internal disagreements over the eugenic worth of the proposal, the society's leadership would not sanction a more active role in the ongoing campaign for family allowances.Footnote 23

This inaction left the field clear for Rathbone's own Family Endowment Society (FES) to dictate the terms in which family allowances were presented to the professions, politicians and the public. The FES had roots in the suffragist, feminist and socialist movements, and whilst the demographic of its membership broadened through the 1920s, the political flavour remained decidedly left of centre.Footnote 24 FES members envisioned family allowances chiefly as a tool of female emancipation, and as a means of alleviating poverty through the equitable redistribution of wealth. It was imperative for Fisher that this vision of family allowances be combated. If the socialists succeeded in shaping the narrative and claiming family allowances for their own cause, then eugenists would have ‘lost the first round’. ‘Perhaps it is inevitable that we should lose this round’, Fisher conceded to his friend and fellow eugenist Major Leonard Darwin, ‘but you must excuse me for fighting against it’.Footnote 25 In his effort to steer the conversation towards racial betterment, Fisher joined the FES, attended its meetings and even delivered papers at its conferences.Footnote 26 Unsurprisingly, his insistence that allowances be proportional to income, with higher earners receiving larger payouts, garnered little support among FES members. The FES nevertheless welcomed him in, being no doubt glad to be able to advertise the authoritative support of one of the country's leading statisticians.Footnote 27 There is little evidence, however, that Fisher's presence within their ranks did much to sway the FES from its egalitarian ambitions.

By the latter 1920s, then, Fisher was convinced that he had identified both cause and cure of the dysgenic birth rate. What he lacked was a sympathetic audience. His insistence that allowances be graded in proportion to salary left him at political cross-purposes with the FES, whilst many Eugenics Society members harboured neo-Malthusian reservations regarding any intervention which might exacerbate the ‘population problem’. The meetings and publications of these societies provided him a platform, but lack of space meant that any attempt to put forth his arguments was necessarily compressed, and easily drowned out by dissenting voices. A change in approach was needed, and as the decade came to a close, Fisher opted to set out his theory of civilizations at length, with a mind to publication as a book.

The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection

Published in the spring of 1930 by the Clarendon Press at Oxford, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection brought together a decade or so of Fisher's mathematical attacks upon various problems at the interface of genetics and evolutionary theory. According to long-established narratives in the historiography of modern biology, The Genetical Theory was instrumental in bringing to an end the drawn-out squabbles of Mendelians and biometricians, demonstrating once and for all the complementarity of Darwinism and the new science of genetics. At the same time, it convinced the biological community of the virtues of turning the tools of mathematics and statistics upon the study of evolutionary processes, and helped set in motion the so-called ‘modern synthesis’ in evolutionary studies.Footnote 28 By the end of the century, Fisher's book was widely considered to rank among the most important in the history of evolutionary theory.Footnote 29

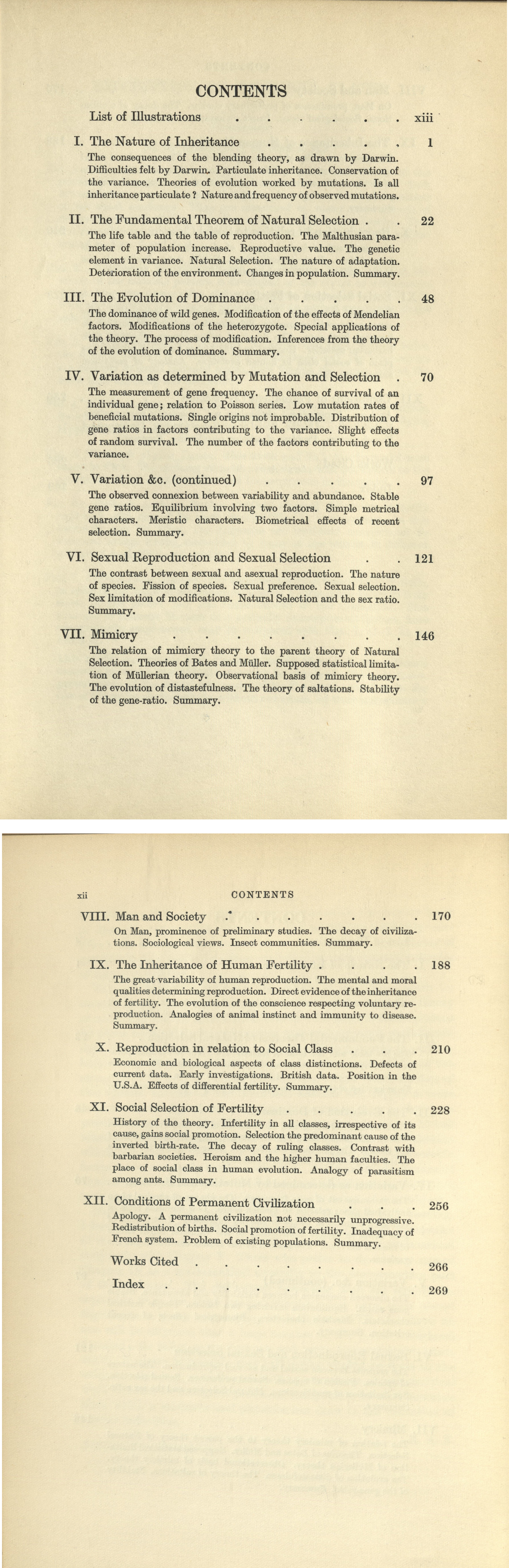

Writing in the year 2000, following the publication of a variorum edition of The Genetical Theory by Oxford University Press, population geneticist James F. Crow stressed the book's continued relevance at the cutting edge of scientific research. ‘Most of the book’, he judged, ‘can be read now, 70 years later, with great profit’.Footnote 30 A lot hangs on ‘most’. The Genetical Theory's enduring legacy is built almost exclusively on the content of its first seven chapters. Modern commentators – true-blue Fisherians included – tend to agree that the book takes a sharp downward turn at around page 170, where Fisher's discussion turns from birds, butterflies and populations of hypothetical gene pairs vying for statistical supremacy to the subject of man (see Figure 2). It is here, in the closing five chapters, that Fisher takes the opportunity to set out his eugenical theory of civilizations in greater detail than he ever has before, with whole chapters dedicated to demonstrating both the heritability of human fertility and its unequal distribution throughout the social scale. Finally, in Chapter 12, Fisher outlines his proposed solution – a system of graded family allowances designed to eliminate the social advantage of small families, bolster the breeding of the professional classes and thus prevent the slow degradation of the national stock.

Figure 2. Contents pages of R.A. Fisher, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930.

The significance of Fisher's decision to include this eugenical material is a matter of long-standing and continuing controversy among historical commentators upon The Genetical Theory. Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, historians and sociologists of science have argued that these chapters reveal deep ideological motives which drove and shaped Fisher's research into genetics and evolutionary theory.Footnote 31 Meanwhile, Fisher's disciples and admiring students have consistently downplayed the importance of eugenics in their hero's intellectual ontogeny, dismissing or excusing The Genetical Theory's final section as an unfortunate irrelevancy.Footnote 32 In general, then, historical attention to these chapters has centred upon the question of what their very presence reveals about the ideological purity, or otherwise, of Fisher's vaunted contributions to modern biology. By contrast, questions pertaining to the reception, circulation and influence of these eugenical chapters among the book's early readers have barely been broached. In the absence of careful scholarship, moreover, Fisher's followers and defenders have been free to assert, based upon little more than anecdotal evidence, that readers of this ‘great’ book have always ‘largely ignored’ its closing chapters.Footnote 33

Whilst modern readers may well pass over the final chapters in embarrassment or indifference, the same was certainly not true for many of the book's earliest readers.Footnote 34 Far from being ‘ignored’, the human chapters were avidly read and widely discussed. Our standard histories straightforwardly present The Genetical Theory as a revolutionary contribution to evolutionary and genetical science. At the same time, however, it was both intended by its author and understood by its readers as a significant intervention in political, economic and eugenical debates over the state and fate of modern civilization itself. The book provided Fisher with a new and authoritative platform. Through it, he communicated his eugenical ideas to new audiences, and even managed to convert some influential figures to his cause. As ‘campaign literature’, then, The Genetical Theory enjoyed moderate success, even if the vision of eugenic family allowances set out in its final chapter would never be realized.

Reading the chapters nobody read

Given genre conventions at Fisher's time of writing, his decision to include his eugenical theory at the end of a technical tome on the mathematics of natural selection and genetics was not all that unusual. Indeed, it was standard for biological texts in this period to close with prescriptions for the human species, and Fisher insisted in the book's preface that his ‘deductions respecting Man are strictly inseparable from the more general chapters’.Footnote 35 There were potential tactical advantages too; folding his eugenical theory into a scholarly work – and no publisher possessed greater scholarly credentials than Oxford's Clarendon Press – promised to add authoritative weight to his discussion. Fisher's authorial decision was nevertheless a risky one. The risk did not lie, as we might imagine, in the potential for this political material to undermine the perceived objectivity of the preceding ‘scientific’ chapters. Indeed, not one of The Genetical Theory's early reviewers begrudged Fisher the opportunity to meditate on the practical applications of his work to human problems. Rather, the risk posed by the book's arrangement was that the ‘human’ portion might simply fail to reach its intended audience. At 17s. 6d., The Genetical Theory was relatively expensive, and learned books, especially those strewn with mathematical formulae, did not tend to sell well. Readers with active interests in the dysgenic birth rate who, however, did not move in specialist biological circles – readers whom Fisher was keen to reach – might not think to give this seemingly arcane book their attention.

On this score, early reviewers of The Genetical Theory in the scientific and popular press did Fisher a favour. Most gave fair warning of the daunting mathematics early on, but all tended to agree that even the ‘general reader’ would find much of value towards the end. The reviewer for Discovery – a short-lived interwar popular-science magazine – emphasized that ‘any educated person’ would be able to follow the final chapters. Zoologist Peter Chalmers Mitchell, writing in the Times Literary Supplement, explicitly advised non-mathematical readers to ‘turn to the last five chapters of the book’, which another reviewer agreed ‘can certainly be read with profit apart from the rest of the book’.Footnote 36 There is good evidence to suggest that several readers followed such advice. Copies of The Genetical Theory which resided in the libraries of the Eugenics Society in London and the Station for Experimental Evolution in New York State, for instance, both bear traces of narrow and focused readings. In each, the human chapters are peppered with marginal notes and pencilled underlinings, while the earlier pages remain relatively unmarked.Footnote 37 Contra the suggestions of Fisher's late-century followers, The Genetical Theory's early readers did not stop reading after seven chapters. At times, they did the opposite – bypassing the earlier more demanding part and beginning with Chapter 8.

Even so, the ‘English reviews’ did not by Fisher's reckoning give enough attention to The Genetical Theory's human part. ‘I do not think they are wrong scientifically in stressing the purely biological parts’, he wrote to geneticist J.B.S. Haldane in late 1930, ‘for these constitute the scientific foundations of the rest’. He felt, however, that ‘the human inferences, if well founded, are of such practical importance that they will certainly be the ultimate centre of interest’. His hope was that Haldane might provide a corrective by ‘putting down something on Man in particular, since a great deal of what I have written, believing it to be a single and coherent argument, has never been criticized, and therefore presumably not followed’.Footnote 38

Haldane was in some ways an unusual choice. While his name and his pen carried weight, his political distance from Fisher was already significant and growing rapidly. Though not yet a fully fledged Marxist, he had by 1930 already thrown off the respectable liberalism of his youth and begun dabbling with socialism.Footnote 39 This much showed when he eventually got round to penning an essay review of Fisher's book for the Eugenics Review. Whilst full of praise for the volume as a whole, he foresaw a ‘good deal of opposition’ to the policy lessons which Fisher chose to draw from his analysis of the differential birth rate. Chapters 8 to 11, we recall, pointed out the social advantages enjoyed by the hereditarily infertile and thus, in essence, exposed the ‘dysgenic’ tendencies of the very structure and organization of modern Western civilization. Where one went from here was then a question of one's attitude to large-scale social reform. Fisher, conservative in his politics, set out in Chapter 12 proposals which would both stimulate a ‘favourable birth-rate’ whilst also, and crucially, being compatible with ‘the economic organization of our own civilization’.Footnote 40 So long as its wage system was properly modified to eliminate indirect incentives towards childlessness, it was entirely possible, Fisher maintained, for a hierarchical class-structured, capitalist society such as Britain's to avoid biological degeneration.

For Haldane, what was required was not small-scale tinkering designed ultimately to preserve the status quo, but rather urgent and wholesale societal reform. Not only was Britain's politico-economic system unjust and inefficient; it was also, as Fisher's dissection of the causes of the inverted birth rate had now demonstrated, inherently dysgenic. ‘If you convince me [on man]’, Haldane quipped in private correspondence, ‘I shall have to become an extreme form of socialist’. He continued his provocation in the pages of the Eugenics Review, writing,

Indeed, if his [Fisher's] biological facts are correct it is probable that a socialistic state in which no wealth was inherited would be more eugenic than our present society, and it is a little difficult to see why Dr. Fisher's economic views are not even more radical.Footnote 41

A few months later Haldane's sister, the author Naomi Mitchison, would turn Fisher's analysis against him in a similar way, remarking that his ‘difficult but thrilling book on Genetics’ represented ‘the best argument for the socialist state which I have yet seen’.Footnote 42

Fisher had to some extent foreseen such politically motivated critiques. ‘Naturally’, he explained to his ally Major Leonard Darwin in March 1931,

finding class differences to be an essential feature of the dysgenic process in civilized life, I have tried to conceive the possibility of biologically progressive societies in which class distinctions were unknown. At every point this seems to lead to an impasse. Man's only light seems to be his power to recognize human excellence, in some of its various forms. From this it follows that actions, powers, and functions cannot be of equal value. Promotion must be a reality, and the power of promotion a real wealth, whether we call our potentates kings or commissars. I do not believe that political capital of any sort can fairly be made out of my book; politically biased people will, I think, merely find it inconsistent, and these must be the great majority of readers.Footnote 43

It was no surprise that Haldane, ‘politically biased’ as he was, had found the book ‘inconsistent’ and plundered it for ‘political capital’. That his response was predictable, though, was no comfort, and Fisher complained angrily to the editor of the Eugenics Review about Haldane's ‘malicious intention’ to ‘split the eugenic movement’.Footnote 44 Though never ‘split’ as such, the movement would be steadily transformed throughout the 1930s, as the Eugenics Society bent to pressure from critics of traditional eugenics, including some prominent voices in Britain's increasingly influential scientific left.Footnote 45 Next I examine the fate of Fisher's family allowance proposals through the first half of the 1930s, against the backdrop of these ongoing reorientations of the eugenics movement. We will see that, notwithstanding some initial interest from within and without eugenical circles, his campaign struggled to gain ground.

‘There should be a bowdlerised edition for statesmen’: The Genetical Theory as campaign literature

Despite Haldane's attacks, Fisher's eugenical theory quickly acquired some prominent converts. Having devoured The Genetical Theory within a fortnight of its publication, the biologist Julian Huxley – an old friend of Haldane's from Eton and Oxford – was quickly won over by the book's human portion. When Huxley's former student Carlos Blacker was appointed general secretary of the Eugenics Society in late 1930, Huxley wrote to him to express his wish that the society ‘go v. carefully into the thesis in Fisher's book's last chapters, &, if it agrees with it, to come out hot & strong’.Footnote 46

A few months later, Huxley went public with his endorsement. In a long article on ‘The vital importance of eugenics’ published in the widely circulated American monthly Harper's Magazine, he devoted several pages to a detailed digest of The Genetical Theory's later chapters.Footnote 47 Like Haldane, Huxley recognized that Fisher's analysis revealed the inherently dysgenic tendencies of Western societies. His politics, however, were more moderate than his friend's, and he stopped well short of calls for radical reform. However ‘desirable’ it might be as an ultimate goal, he told readers, revolutionizing the ‘whole economic and social system’ could not happen overnight. The dysgenic birth rate, on the other hand, was an urgent problem requiring urgent treatment. Eugenists must therefore unite behind ‘some remedy which will work within the limits of our existing system’. Fisher's scheme of weighted family allowances struck Huxley as the most promising remedy available.Footnote 48

Fisher was mightily pleased when by chance he encountered the Harper's article during a North American lecture tour in summer 1931. For one thing, it reassured him that Huxley had not been irredeemably corrupted by his friendships with Haldane and Lancelot Hogben, another ‘red’ biologist.Footnote 49 Moreover, Huxley's growing profile as a popular writer and public intellectual made him an especially valuable ally. This value was soon in evidence when Huxley included his glowing assessment from Harper's Magazine in his latest book. Like his other books, What Dare I Think? sold heavily. Published in the autumn of 1931, it had shifted over three thousand copies by Christmas.Footnote 50 What was more, Julian Huxley was not the only famed writer who took to digesting The Genetical Theory's later chapters for a general audience; nor even was he the only Huxley to do so. His brother Aldous, the novelist and satirist, was similarly convinced of the importance of Fisher's eugenic theory and wrote regularly on the subject in popular magazines. Thus readers of the Weekend Review learned how Fisher's work showed that ‘a society that measures success in economic terms must fatally and inevitably eliminate all heritable ability above the normal’. Writing for the daily morning newspaper New York American, Aldous quoted The Genetical Theory at length before throwing his weight behind Fisher's suggestion of a ‘system of liberal family allowances’.Footnote 51

A year on from The Genetical Theory's publication, Fisher began to feel hopeful that his eugenic ideas might gain wide acceptance. Thanks to the Huxleys’ powerful pens, the arguments of the final chapters were enjoying significant airtime in the popular press. In September 1931, Fisher returned to Britain from his North American lecture tour to news of better-than-expected first-year sales, and that same month read a glowing review of The Genetical Theory in which popular-scientific writer J. Arthur Thomson suggested, ‘There should be a bowdlerised edition for statesmen’.Footnote 52 Indeed, there seemed to be no better time to push for eugenically minded reform. In October, Ramsay MacDonald's National Government achieved a landslide general election victory. The Labour Party – wherein lay much of the parliamentary opposition to eugenics – was decimated, leaving the ostensibly more amenable Conservative Party as comfortably the largest party in the House of Commons with 470 seats. This new government would surely waste little time in restoring the ‘cuts’ made by the second MacDonald administration amidst the ruin of the Great Depression, and Fisher was among those hoping they would do so on firmly eugenic principles.Footnote 53

As the dust settled, Fisher wrote to congratulate his old university friend Derrick Gunston, who had secured his Gloucestershire seat with a thumping majority. In reply, Gunston, who had served with Fisher on the Cambridge University Eugenics Society's council, expressed his hope that, through the current parliament, ‘many of the dreams which you and I dreamed at Cambridge will at long last be realised’. Encouraged, Fisher sent along some of his articles on family allowances and alerted Gunston to his ‘more or less unreadable book’. Some reviewers of The Genetical Theory, Fisher explained, ‘suggest that I ought to supplement it by an edition more intelligible to politicians. I shall not attempt that, however, until I know more clearly what difficulties people like yourself see ahead’.Footnote 54

If he was to force eugenic family allowances onto the parliamentary agenda, Fisher would need the Eugenics Society to throw the full weight of its lobbying powers behind him. However, there was still much scepticism within the executive council regarding the eugenic worth of family allowances. In June 1932 they appointed a subcommittee, with Fisher as chair, to ‘study Family Allowances and to make a recommendation thereon to the council’.Footnote 55 If, as seems likely, this was a delay tactic aimed at putting off the need to adopt a firm position on the matter, it turned out to be a masterstroke. The subcommittee dithered for months over producing a pamphlet setting out the eugenic virtues of Fisherian graded family allowances, their progress hampered by a bitter power struggle between Fisher and Carlos Blacker, the society's general secretary.Footnote 56

When a bloated seventeen-page draft pamphlet was finally completed in spring 1934, the society's council refused to sanction its publication. Instead, at the recommendation of population scientist Alexander Carr-Saunders, the Eugenics Society opted to change course and commission a series of ‘purely factual’ reports on existing family allowance schemes at home and abroad.Footnote 57 In autumn 1934, a new subcommittee for ‘Positive Eugenics’ was assembled under Carr-Saunders's chairmanship to organize the project and disseminate its results. The research itself was outsourced to David Glass, a promising young social scientist at the London School of Economics.Footnote 58 Fisher was effectively sidelined, his ambitions of lobbying the government on family allowances quashed, or at least indefinitely delayed.

Fisher had observed close at hand the society's readiness to campaign forcibly – if unsuccessfully – for legalizing eugenic sterilization, meaning that he was all the more disappointed when it failed to ‘come out hot & strong’ for his own pet proposals. His frustrations came close to the surface in an address to the society's annual meeting in 1935. ‘Only by framing legislative proposals as in the advocacy of voluntary sterilization’, he urged, ‘and by preparing ourselves to mobilize our political influence, can the Society, I believe, achieve aims which deserve to be called practical’.Footnote 59 The moment, however, had passed. As Richard Soloway has observed, under Blacker's 1930s leadership the society shifted its focus steadily away from lobbying government and industry, and increasingly towards the ‘serious study of social and biological population problems’.Footnote 60

This reorientation of the society's aims was in no small part a response to vocal criticism of the eugenics movement from the likes of Haldane and Lancelot Hogben, whose 1931 book Genetic Principles in Medicine and Social Science was interpreted by many as an all-out attack on the very idea of eugenics.Footnote 61 Part of Blacker's appeasement programme involved encouraging the study of ‘the eugenic or dysgenic tendencies of different types of social structure’, a subject which, at Blacker's urging, Huxley tackled in his invited Galton Lecture at the Eugenics Society's annual meeting for 1936.Footnote 62 Huxley used to the lecture to urge the society to re-evaluate its long-standing and unthinking commitment to the predominance of ‘nature’ over ‘nurture’. Social reform, he argued, was an essential first step towards the eugenic improvement of the population, and this for scientific rather than sentimental reasons. As the central role of ‘environment’ in biological development became better understood, it occurred to Huxley that entrenched social inequalities would tend to mask and obscure the existing variation in a population's biological worth. Only in a more egalitarian social environment, where all were given the opportunity to develop to their fullest potential, could the eugenist be sure that they were selecting from the innately superior examples of the human species.

This address, titled simply ‘Eugenics and society’, has become synonymous with the new ‘reform eugenics’ which dominated the society's activities from the mid-1930s. It is also illustrative of a shift in Huxley's political and scientific thinking, which saw him, through the mid-1930s, adopt an increasingly critical stance towards the rigid racial and class-based categories and thinking which pervaded contemporary biological and eugenical discourse.Footnote 63 Fisher's eugenic scheme was among the casualties of this change in perspective. A convinced hereditarian, Fisher's biology and his eugenics left little room for the importance of ‘environment’, and Lancelot Hogben had already attacked the genetic determinism inherent in the methods employed by Fisher in The Genetical Theory's early chapters.Footnote 64 Now Huxley turned the ‘environmentalist’ critique upon the book's eugenical portion. Whereas five years earlier Huxley had endorsed proportional family allowances as a necessity for combating the dysgenic birth rate, he now read the later chapters of The Genetical Theory as exposing the urgent need to overhaul the structure of an essentially dysgenic society. ‘[S]o long as we cling to a system of this type, the most we can hope to do is to palliate its effects as best we may … As eugenists we must therefore aim at transforming the social system’.Footnote 65 As Haldane and Mitchison had pointed out some years earlier, The Genetical Theory was nothing if not a powerful argument for socialism.

Fisher, disillusioned with its direction under Blacker, had already begun to withdraw from active participation in Eugenics Society matters by the time of Huxley's Galton Lecture.Footnote 66 His retreat from the society did not, however, signal the end of his campaign for eugenic family allowances, as he increasingly took to the pages of the daily newspapers to air his views.Footnote 67 What he read in those same papers gave him hope that all was not lost. From around the middle of the decade, the widespread neo-Malthusian fears of overpopulation which had proved such an obstacle through the 1920s were replaced with a veritable ‘depopulation panic’ sparked by Britain's steadily falling birth rate.Footnote 68 Amid a clamour for pro-natalist policies, family allowances were widely touted as an efficient means of boosting breeding, and of solving many of the challenges facing Britain's industrial ills. Though Fisher's main concern was with the quality, rather than quantity, of the population, he nevertheless sensed the opportunity. In November 1938 he wrote to his publishers at the Clarendon Press to explain his feeling that The Genetical Theory's later chapters ‘possess, now, rather more popular interest than they did when they were written’, and to enquire as to what might be done to capitalize on this change of circumstances. As he explained, ‘the prospect of selling, for the next nine years, some thirty copies of the remaining stock, annually, does not go far to meeting my desire to make these ideas more widely known’.Footnote 69

Angling after a reduction in the book's pricing, Fisher wondered ‘whether any better use could be made of my material than merely to sell the remainder of the edition at its present rate’. Kenneth Sisam, who had overseen the initial publication process, assured Fisher that no such discounting could ‘alter its character as a learned book rather than one for a wide public’. Sisam also ruled out Fisher's second suggestion of a straight reprint of just the human chapters, as ‘to sell a piece of an existing book is a very difficult process’. He suggested instead that a thorough rewriting of the relevant chapters in an essay-like form, suitably remodelled to reflect ‘the new purpose and audience’, would ‘probably be well worth undertaking’.Footnote 70 Fisher, it seems, had been hoping for a more straightforward path of action, and hardly jumped at the prospect of the extra work. When a colleague of Sisam's pressed him on the matter several months later, Fisher admitted that he had ‘not given further thought to it’. At the end of July 1939, they determined to delay further discussion until the return of Sisam, who was away on holiday. A little over a month later, Britain was at war, and the question of republishing a revised version of The Genetical Theory's later chapters was quietly dropped.Footnote 71

Beveridge and what might have been

Whilst the outbreak of war put paid to any tentative plans for a reissue or rewrite of The Genetical Theory's final chapters, it also created the conditions under which family allowances would finally pass into official government policy. In 1945, the British government set about enacting the recommendations of William Beveridge's famous report, Social Insurance and Allied Services. Published in the winter of 1942, the report is widely understood by historians as the blueprint for the post-war British welfare state.Footnote 72 A system of ‘children's allowances’ was one of its headline proposals. Though Beveridge was sympathetic to the eugenics movement, the scheme he outlined was aimed principally at the alleviation of the poverty which fell so heavily upon families with children. His was a flat-rate subsistence-level scheme, funded through general taxation. In other words, it was antithetical to Fisher's proportional scheme aimed at boosting births in the eugenically desirable classes.

Shortly after the publication of Social Insurance and Allied Services in November 1942, Beveridge accepted an invitation from the Eugenics Society to deliver the Galton Lecture for 1943, on the subject of ‘Eugenic aspects of children's allowances’.Footnote 73 Though long estranged from the society, Fisher nevertheless caught wind of Beveridge's impending address and took the opportunity to send him offprints of some old articles on family allowances. Reading them persuaded Beveridge to acquire and read for the first time The Genetical Theory. He was convinced by the arguments in its later chapters, making ‘very great use’ of them in preparing his address to the Eugenics Society.Footnote 74

As his audience at the Eugenics Society would have known, Beveridge had not necessarily based his report on eugenic principles. It recommended a flat-rate allowance of eight shillings per week per dependent child, funded through taxation, which the government looked likely to put into practice (though at the lower rate of five shillings). Whilst this might go some way to battling poverty, even the full amount would ‘not go far enough from the eugenic point of view’. This much was clear once one understood Fisher's theory of the social selection of fertility, which Beveridge duly summarized for his listeners. Once flat-rate subsistence allowances were in place, the next step – ‘and an essential one on eugenic grounds’ – must be to ‘supplement’ them with further measures which would remove the premium on infertility throughout the social scale, and not just in its lower reaches. Having familiarized himself with the arguments put forth in The Genetical Theory, Beveridge now had ‘a eugenic reason for giving more money – as much as he could – for children of the more wealthy classes’. In other words, a graded scheme was required.Footnote 75

Of course, this realization came too late to influence the composition of Beveridge's report, which was already being debated in Parliament. Eugenic ‘supplements’ to his scheme for children's allowances were never suggested, and certainly not implemented.Footnote 76 Whilst it is tempting to speculate about what might have happened had Beveridge read The Genetical Theory even a few months earlier, we cannot know if doing so would have affected the recommendations he made in his 1942 report. And even if Social Insurance and Allied Services had pushed a Fisherian proportional system of allowances, it is difficult to imagine the post-war Labour government implementing a scheme which paid more to those already better off.Footnote 77

More instructive than the counterfactual, arguably, is the actual. Beveridge did not read The Genetical Theory until prompted to do so by its author in early 1943. This might strike us as surprising given his long-standing commitment to family allowances; a commitment so deep, indeed, that he introduced a scheme for the staff at the London School of Economics, where he was director from 1919 to 1937. Like Fisher, Beveridge had been ‘converted’ by reading Rathbone's The Disinherited Family in 1924, and shortly thereafter he joined the Family Endowment Society, where the two men would have rubbed shoulders and shared the speaker's podium at meetings.Footnote 78 As we have seen, moreover, following The Genetical Theory's publication in 1930, Fisher's eugenical ideas were discussed widely in print by some influential writers. Nevertheless, Beveridge wrote and spoke in early 1943 as though Fisher's treatment of the subject in The Genetical Theory's closing chapters was entirely new to him. Here, perhaps, we see Fisher's decisions on how to promote and publicize his ideas coming back to bite him. It appears that, by effectively burying his discussion of family allowances at the end of a scholarly tome on the mathematics of selection, he harmed his chances of reaching some sympathetic and highly influential readers. The same goes for his decision to pass up Kenneth Sisam's 1938 proposal to rewrite and republish The Genetical Theory's human chapters as an extended essay. Had he done so – had he in effect followed J.A. Thomson's suggestion and prepared a ‘bowdlerised edition for statesmen’ – then his ideas might have become known to the likes of Beveridge far sooner.

Conclusion

Beveridge's 1943 Galton Lecture would turn out to be something of a last hurrah for Fisherian family allowances. His proportionate scheme – premised upon larger payouts to wealthier families – had proved itself a hard sell, politically, through the interwar years. In the post-war era, as Britain's newly elected Labour government set about redressing social inequality and building the modern welfare state, it became an outright impossibility. Following one final attempt in 1943 to push eugenically minded family allowances onto the agenda for post-war reconstruction, Fisher brought his two-decade campaign to a close.Footnote 79

His broader theory of the social selection of fertility fared only a little better in the long run. Fisher was enticed into a rare and revealing reflection on the fate of this theory when, in 1951, an old university friend who was rereading The Genetical Theory's closing chapters inquired to what extent ‘the Scientific Public’ had embraced his conclusions. ‘To individuals’, Fisher responded, ‘what I have written has certainly carried conviction. Others like Haldane and his Communist friends obviously feel that my ideas were dangerous to the cause and should be ignored or undermined in various ways’.Footnote 80 In fact, his ideas were not entirely ignored. They attracted a certain amount of attention from post-war demographers and practitioners of the nascent field of social-mobility studies, though most would soon come to agree that Fisher's writings on human societies had been discredited by new data on the factors affecting social mobility. Through mid-century, references to Fisher's theory of civilizations dried up, as hereditarian approaches to understanding the distribution of human fertility were almost wholly dismissed in favour of social, cultural and environmental accounts.Footnote 81

Nowadays, The Genetical Theory is chiefly remembered for the achievements of its early chapters, which helped lay the foundations of modern population genetics and evolutionary theory. Scientists no longer take seriously the arguments developed in the book's final chapters, and their chief relevance today is as illustration and reminder of Fisher's deep eugenical commitments – commitments which, it is commonly held, were important in shaping Fisher's science ‘proper’. But as we have seen, throughout the interwar period and in the context of Fisher's decades-long campaign for eugenic family allowances, The Genetical Theory's human chapters enjoyed a significant life of their own – almost, but not quite, in a literal sense.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my PhD supervisor, Greg Radick, for his encouragement and enthusiasm, and to Niamh Gordon for reading (several) earlier versions of this essay. Thanks to the editorial team at the BJHS for their wisdom and patience, and to two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions, which helped clarify and strengthen the argument. Thanks also to Cheryl Hoskin and her team at the University of Adelaide Special Collections for their assistance during my research visit to the Fisher Papers, which was generously funded by the British Society for the History of Mathematics, the British Society for the History of Science, and the Royal Historical Society. The research for this article was undertaken during my doctoral studies at the University of Leeds, where I was supported by a Leeds 110 Anniversary Research Scholarship.