Be sad for a fleeting moment, but rage and rage [against the patriarchy] for a long time! This rage is an individual revolution and the beginning of yours. Even if there is a big wave of backlash against this revolutionary rage, reassure yourself.

—Anonymous Author 1 in the web comic Diary to Escape the Corset (2019)Footnote 1The multiple layers of reality are so overturned that Korean society, which is macho and authoritarian, no longer functions as before. This turbulence that constitutes “the era of feminism” in South Korea results from women's rage, which breaks the silence and resists subjugation. What, exactly, is this rage? It is part of a spectrum of anger, differentiated from other forms, characterized by an intense explosion of control, a discharge of pressure, an instantaneous eruption, and a transgression of barriers. Rage in itself is neither progressive nor conservative; rather, rage embodies deeply internalized patterns of judgment and habit. Even though rage appears to be devoid of judgment, “its patterns can be laid down in childhood, and these habitual patterns may guide behavior, on many occasions, without conscious focus” (Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2016, 263). It is the very detonator of a sociopolitical event and “always contains a cognitive appraisal, even if stored deeply in the psyche and not fully formulated” (263). The explosive and instantaneous aspect of rage seems to be neither well understood nor justified. For a more precise understanding, translation is required. Rage should be considered alongside other modalities of emotion, such as indignation or hatred, which are fully formulated and cognitive attitudes. To achieve consistency and durability, rage can be combined with the axiological values of fairness and unfairness. By forming a connection with rage, other modalities of affect can be more intense and efficient. These modalities are all interdependent. It is essential to consider by whom, with what motives, and in what situations rage is manifested and to what other emotions it is connected.

Martha Nussbaum, in her book Anger and Forgiveness, describes anger as “profoundly flawed” and as having “limited usefulness and normative inappropriateness” (Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2016, 6). This negative qualification of rage does not take into consideration its multidimensional force, which is not limited to a “reactive attitude and feeling” (Strawson Reference Strawson and Strawson1968). Noting the importance of Adrienne Rich's work (Rich Reference Rich1973), Soghra Nodeh and Farideh Pourgiv define women's rage as “a source of energy releasing women from the social norms that are imposed on them by patriarchy throughout history” (Nodeh and Pourgiv Reference Nodeh and Pourgiv2016, 35). Sara Ahmed asserts that rage “is not simply defined in relationship to a past, but as opening up the future” (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2004, 175). Rage is not only reactive but also active. Indignant rage yields creative productivity and rearrangement of the spatial and temporal field to allow for a more just and egalitarian horizon in the future. In other words, rage induces change in the world. The tectonic force of rage rearranges the very structure of daily life and women's habitus in South Korea. To deepen understanding of the dynamic force of indignant rage that characterizes today's feminism in South Korea, it is crucial to highlight its context in Korean society. In the current climate in South Korea, awareness is being raised about the severity of digital sexual crimes, and the popularization of feminism has resulted from the advent of a new generation of feminists since 2015. Without focusing on this momentous period, one cannot understand the ongoing gender issues and the radical changes in Korean society. The renewal of the feminist movement since 2015 that has popularized feminism is a historic event that has created a new form of resistance. After the Korean system of the head of the family was abolished in 2005, a backlash and reactionary discourse ensued that reinforced the ideology of reverse-discrimination against men. Many courses on feminism in universities were no longer being offered. Most people thought that feminism was no longer valid, that all rights had been acquired by women, and that men were the victims of discrimination. In this hostile atmosphere, feminism seemed to be obsolete, and antifeminist tendencies became mainstream. In 2010, Il-Be, an ultra-chauvinist website in South Korea, was created. On this platform, violent prejudice against women spread and circulated rapidly, and rape culture became the engine that strengthened male homosociality.

However, the social crisis resulting from the international spread of a coronavirus known as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, which occurred in May 2015, led to the creation of the feminist website Megalia,Footnote 2 whose recipe for success lay in its strategy of expressing indignant rage by inventing parodic and subversive language caricaturizing Korean sexist culture. Before the emergence of Megalia, cyberspace, which was imbued with machismo, had long been considered abandoned territory by older feminists. Technology used for rapid communication has served as a vehicle for misogynistic terms and sexist humor over which the language of persuasion and reason used by older feminists had no control. This abandonment reinforced increased verbal and physical violence against women. In this context, the new feminist generation, Koreans in their twenties and thirties, decided to experiment using parody aimed at satirizing men's impositions on women and depicting a strange, inverted reality wherein women are custodians of all prerogatives. This subversive language was most effective in bringing forth the absurdity of violence against women and in aiming radical criticism of the gender inequities toward the regime.

In other words, the new South Korean feminist generation has resorted to another modality of resistance, the politics of rage. Instead of using the language of persuasion, charged with sincerity, the young feminist generation has created an innovative strategy combining indignation with satirical humor and rage with cathartic joy. Instead of constantly swallowing rage, the millennial feminist tries to share such rage against social prejudices, because manifesting rage at the collective level has been a crucial turning point in establishing feminist solidarity and defining sexual disparity as a structural and societal problem. This defiant rage, a vehicle for raising awareness about the social injustice of which these feminists are victims, is a way of removing the weight of guilt and self-hatred from women. By exposing the absurdity of the gender regime, millennial feminists release laughter and rage so as not to be overwhelmed by the fear and guilt that gnaw at women. The emotional conjunction between rage and joy leads to an intensely cathartic sensation of liberation and justice.

Since 2015, most young Korean women have incorporated feminism as a means of survival and resistance. However, for the older feminist generation, known as the young feminists, feminism is an ethical-moral discourse based on political correctness, criticism, distancing from power, and sacrifice and care for other social minorities. For the younger feminist generation, known as the hellfeminists,Footnote 3 feminism is a utilitarian and political discourse that enables women to acquire rights, take power, and maintain ambition. This difference of perspective on feminism is the cause of tension between generations of feminists. The Megalia generation is at a pivotal moment in creating a feminist multitude that is no longer a mass to be manipulated by the media or elites. It is this feminist multitude that creates the issues and the discourse known as feminist strategies. For this younger feminist generation, feminism is no longer a noble theory reserved for academics, no longer an activity reserved for professional activists. Instead of stifling rage, since 2015, the new feminist generation has begun to vent its rage on an absurd world.

Rage has a gendered dimension in the sense that the legitimization of men's rage and the delegitimization of women's rage establish the basis of a patriarchal society. Male rage is defined as a positive and productive force, whereas women's rage is frequently seen as unproductive and malicious. As the rage of minorities, such as Muslim affect and American black anger, has been negatively devalued, so has women's rage. In this vein, the pathologization and medicalization of rage are analyzed by Janet Wirth-Cauchon in Women and Borderline Personality Disorder as two narrative devices whose objectives are to “depoliticize women's rage” (Wirth-Cauchon Reference Wirth-Cauchon2001, 169): These ideological devices appear first in “the rhetoric of rage as a natural force or flood” and second in “a displacement of rage from a paternal to maternal source, in which psychiatrists attribute the sources of rage to early mothering while ignoring its sources in women's social relations in patriarchal culture” (169). The first device focuses on the insecure and risky dimension of rage in which the loss of self-efficacy and self-fragmentation takes place. This produces a harmful effect by which the naturalization of repulsion to rage and the prohibition of women's rage as a social taboo are established for a properly functioning society. The second narrative device ignores the structure of the male violence that engenders women's physical and psychological suffering as well as loss of a sense of self. This results in the imputation of guilt to women and the inculcation of self-blame and self-injury to consolidate the self-deprecation and self-impairment that make women vulnerable and keep them in a state of submission. From this perspective, it can be seen that the pathologization of rage is an efficient device of male domination. Such pathologization aims to reverse cause and effect, proposing that rage causes instability in oneself and in society; however, it is essential to consider that women's rage does not cause women's vulnerable status. Rather, the unequal structures of sex, gender, and sexuality cause women's rage as well as the instability of their living conditions.

In this article, first, I will introduce the notional difference between indignant rage and collateral rage as hatred to deepen the notion of rage. Second, I will focus on the defiant and resistant dimension of “Escape the Corset” and the correlation between beauty norms and gender normativity. Third, I will analyze the creative dimension of the politics of indignant rage through three aspects: lexical, axiological, and ontological.

“Escape the Corset” and the Emergence of Women's Rage

In South Korea, “Escape the Corset” began in 2016 and has grown in scope to become a main agenda of feminists in 2018 (Haas Reference Haas2018). It is an attempt by women to take charge of their living conditions and to emancipate themselves from psychological, physical, sexual, and social repression. Korean feminists define these oppressive devices as a “corset.” The corset is more metaphorical than literal in terms of its makeup and its relation to various patriarchal structures that constrain Korean women's minds as well as their bodies. The choice of this term, corset, by Korean feminists efficiently emphasizes the intense degree of the oppression of beauty norms. For Korean feminists, the corset is not a Western and obsolete device but a universal symbol of the cruelty of the male-centered economy of desire in the sense that the corset restricts breathing, breaks women's ribs, and deforms and damages their intestines. From this perspective, corset is an appropriate word to depict the gendered dimension of beauty and the correlation between beauty norms and gender normativity. Korean feminists tend to use foot-binding and corsets as the most representative features of the constriction of women's bodies, and there is no Korean idiom comparable to the term corset to more accurately expose the efficiency of the toxic beauty norms that reinforce the subordination of women by men.

It is worthwhile to trace the genealogy of the corset: It came with the Spanish court in the sixteenth century. Originating in the masculine and military world, the corset was physical and moral armor reserved for nobles. Its initial form was conical and narrow in shape, strongly compressing the floating ribs. The corset aimed at modeling a noble and distinct body, essentially a male aristocratic body that symbolizes the rightness of the soul. A curved shape was considered mean and inferior, whereas a straight shape was sublime and superior. This is a misogynistic point of view in the sense that women in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries tried to imitate the noble and masculine form by erasing the female corporal form. Since the nineteenth century, the shape of the corset has been transformed into that of an hourglass, emphasizing large breasts on a constricted waist, leading to excessive exaggeration of the female body shape. This leads to the hypersexualization of a woman's body. In this sense, the corset is not simply underwear because “dress of an individual is an assemblage of modifications of the body and/or supplements to the body” (Roach-Higgins and Eicher Reference Roach-Higgins and Eicher1992, 1). The corset is a clothing type that indicates the identity of the dominated class and implements “body modifications that can directly put health at risk” (4). In a patriarchal society, a woman's body is regarded as one that endures substantial discomfort and is weakened by pain. In contrast, a body full of health and vitality is the privilege of the masculine and dominant.

In Korean society, beauty is an absolute and ultimate value that is exclusively allowed for and imposed upon women. As a duty and attribute of women, beauty is a gendered value that constitutes the axis of femininity. Beauty norms involve not only a myriad of codes and rules for personal appearance but also multiple codes of attitudes and values. In Korean society, a beautiful woman is synonymous with a docile and harmless woman. Harmless women never hurt men's narcissism and preserve male authority and the male-centered perspective. This kind of woman does not hesitate to inflict much damage on herself and earnestly overlooks her own wants and needs. This phenomenon can paradoxically be explained by the weakening of Korean men's economic status due to “the IMF crisis of 1997” (Cho Reference Cho2009, 160), which undermined male supremacy. As if to compensate, men responded by “doubling down” on the subordination of women. The proliferation of images of harmless, submissive women who are both hypersexualized and infantilized facilitates men's manipulation of women and perpetuates male superiority. The crisis of masculinity reinforces the internalization of toxic beauty norms that contribute to the idealization of a harmless woman. In Korean society, women are valued as desirable for their bodies, which guarantees the exchange value of the female body as capital, or as reproductive capital, cementing patrilineal sustainability.

Korean beauty norms are intrinsically associated with the K-pop culture, Korean pop-idol entertainment, and K-cosmetics and plastic surgery that constitute an enormous K-beauty industry. Korean female pop idols are a unique identification model for girls and women. Most Korean women endeavor to imitate the ideal beauty standards that female pop stars perfectly embody, because the illusion of a good life for women based on the strong combination of beauty and youth is reinforced by K-pop culture. For Korean girls and women, beauty is the only way of attaining, with ease, success and wealth in a society where the pay gap between women and men and the glass ceiling persist. Though Korean male idols with androgynous makeup and dress exist, most Korean boys and men do not consider them to be role models. For Korean men, the path of success and wealth is not guaranteed by physical beauty, but by the acquisition of force and authority that could dominate others. In Korean society, a man who pays considerable attention to his appearance and applies makeup products to his face is seen as an eccentric or effeminized person who could be expelled by the male community. In this Korean context, where there is a strong entanglement between Korean pop-idol entertainment and the Korean beauty industry, the prevailing impact of such entertainment on the Korean people consolidates gender normativity rather than liberates it. In the international context in which the enormous impact of the Korean beauty industry is weakening, and the normativity of masculinity is not predominant, Korean male pop idols are the role model for many fans, and their androgynous makeup could have a liberating effect on international fans. The opposite is true in Korea.

In South Korea, young girls, even before they attend primary school, become the main target of marketing in the cosmetics industry. According to a BBC News feature, “Children as young as three years old are getting involved too” (BBC 2019). The standard of physical beauty is so high for women that parents happily fund cosmetic surgery for their daughters as a reward commensurate with achieving results good enough for admission to university. For young girls, makeup becomes one of the signs of integration into a circle of friends at school; to avoid isolation and exclusion by friends, schoolgirls are forced to buy makeup products and apply them to their faces routinely. For women, facial makeup and thin waists have become matters of social etiquette and signs of self-esteem, “a basic duty for women” (Jo Reference Jo2018). Rigid beauty norms have become a second skin for women. In this context, “Escape the Corset” means no longer staying in the place assigned by society and no longer remaining silent. The perpetuation of self-control through the internalization of social conventions and the laws of the father engender self-denial, loss of self-confidence, and dependence on men, but this protest movement is a break from the practice of typecasting women's bodies.

Let us focus on a recent portrayal of an enraged woman on Instagram (Figure 1). This figure was drawn by a young Korean woman who actively participates in “Escape the Corset” and aims to provide another representation of women involved in the struggle. The straight hair and pale face are considered the ideal features of Korean women. However, the unexpected and shocking aspect of the shaved head and tanned face of the Korean woman depicted in Figure 1 is a movement strategy to break stereotypes about women's appearance. The redness of her frown, the lack of makeup on her face, her wide-open mouth screaming loudly, and her shorn hair bristling with rage collectively show the subversive and creative power of women's rage. In a misogynistic society, women's facial redness is translated as an indicator of sexual arousal or shyness, shame, and childlike naiveté; but in this image, redness is a sign of visceral rage and a statement of revolt that departs from the image of a harmless and docile woman. A wide mouth is suggestive of articulating one's feelings and opinions against society's patriarchal status quo. According to the sexual objectification of women's bodies, all female orifices enable penile penetration and male pleasure. However, her widely open mouth, which seems to scream and affirm her existence, subverts this economy of phallic desire, fights against the hegemonic logic of the world, and insists on a new feminist logic of acting and speaking against marginalization. Her teeth seem ready to tear apart the fabric of a world that allows the exploitation of women. A woman in a rage has shorn hair instead of long, showing her refusal to adopt normative standards of feminine beauty and to be reduced to a desirable body that arouses men's lust. She rejects living like a doll ready to be loved and pampered, or even badly treated, denigrated, and humiliated. This image of an enraged woman clearly shows that indignant rage is a linchpin of creativity, producing a new individual practice of unprecedented epistemological and ontological value to women that includes the ability to think critically, problematize, and maintain a critical distance from the hegemonic limits. Hers is an image of resistance, dignity, courage, and challenge.

Figure 1. An enraged woman (Instagram@nigagara_hwai).

The Notional Difference between Indignant Rage and Rage as Hatred

Rage is an instant explosion that does not in itself contain any value orientation. Its speed and intensity go hand in hand with its ephemeral nature. For the force of rage to persist and contain a moral and social character, it must connect to another modality of emotion. Women's rage, when connected to indignation, carries a sociopolitical sensitivity to justice and parity. Rage, a primary and unmediated force, coupled with indignation becomes a more consistent force and a means of critically evaluating an unjust past and a consideration of a future horizon. “Indignation is defined as a non-primary, discrete, and social emotion, specifying disapproval of someone else's blameworthy action, as it is perceived to be in violation of the objective order, and implicitly perceived as injurious to the perceiver's self-concept” (Miller, Burgoon, and Hall Reference Miller, Burgoon and Hall2007, 819). Rage concomitant with indignation is embedded in a sociohistorical context. It is by this that indignant rage acquires an analytical and ontological dimension that produces a form of constructive intervention in temporality. It has an interpretive force that creates a hermeneutical field to survey society and social life. Indignation without rage cannot have a strong effect, whereas rage with indignation can impart a dynamic force.

In order to better grasp rage coupled with “indignation being the reason for resistance” (Hessel Reference Hessel2010, 11), it is essential to ask: By whom is this indignant rage formed? In what situation was it born? How is it constituted? What type of control is implicated? Indignant rage is an experience of the minority and the oppressed. This indignant rage results from the realization that social minorities have yet to acquire and be assured of fundamental rights. It launches a radical questioning of the world order and a challenge to the dominant class. It is linked to the circumstances of discrimination and exploitation. This situation of iniquity gives rise to indignant rage directed toward putting an end to sociopolitical injustice. In the context of this article, this rage aims to break the psychic control of women imposed to subjugate and deprive them of cognitive capacity and the power to act. The force of rage is exploded and reconfigured by indignation to reveal the absurdity of the established order. This complex effect disrupts the social order, rearranges the politics of the body, and deconstructs the gender regime. Indignant rage drives change and transmutes values. By disrupting the status quo, it is revolutionary. Indignant rage's full realization requires unwavering courage to effect change to existing power dynamics, because it often meets a conservative reaction to dismiss it. Since indignant rage does not depend on the hegemonic tradition of thought and action, it should engage in the creation of new argumentation, and a new semantic and axiological field. Indignant rage requires the epistemic powers of imagination, critical analysis, and creativity.

From this perspective, “Escape the Corset” makes indignant rage concrete and material. The movement embodies a dynamic of women's emancipation intended to end the objectification of the female body as a controllable and acceptable practice defined by the hegemonic norm. Inculcating the standards of beauty and docility in women aims to produce obedient, harmless female bodies that do not compromise the self-love of narcissistic men. In other words, the harmlessness of such a female body, maintained for the benefit of men, is detrimental to women's physical and mental health. The weakening of women facilitates the reign of men. “Like any economy, beauty is determined by politics, and it is the last, best belief system that keeps male dominance intact,” says Naomi Wolf. “The assigning of value to women in a vertical hierarchy, according to a culturally imposed physical standard, is an expression of power relations in which women must unnaturally compete for resources that men have appropriated for themselves” (Wolf Reference Wolf2009, 21). Korean women decided not to be content with the praise of beauty, and instead to offer stubborn resistance to a condition wherein value is monopolized by men.

On the other hand, rage coupled with hatred produces other social phenomena. In order to clarify rage connected to hatred, it is important to ask: By whom is this rage as hatred formed? In what situation was it born? How is it constituted? What type of control is implicated? Rage as hatred is “about status-injury with a narcissistic flavor” (Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2016, 21). In this sentiment, Nussbaum seems to confound rage as hatred with anger. Rage as hatred is an obsession with defending one's social status, and this narcissistic obsession is a privilege and experience of the ruling class and the dominant majority. Rage that is status-focused is combined with hatred that is governed by the desire to “restore lost control” (21). Only the dominant majority has the resources to restore the power to control others; minorities and the oppressed only have the resources to attempt resistance of their control by the dominant. This is why rage as hatred is a conservative force that tends to maintain the established patriarchal order and its efficiency, seeking to control others in order to maintain and strengthen its power. This rage forms within a hierarchical society wherein the demand for equity on the part of the oppressed is increasing. This growth of the minority movement is seen as an unacceptable threat and a disruption requiring intervention so that the law of the strong continues to reign in society. For instance, “that women have in their possession a vast and untapped vitality also explains one of the more baffling phenomena of the backlash—the seeming overreaction with which some men have greeted even the tiniest steps toward women's advancement” (Faludi Reference Faludi1991, 465). The phenomenon of the backlash is a concretization of collateral rage as hatred that aims to hinder any social change and consolidate patriarchal law and traditional values.

Rage as hatred is characterized by the determination that the future is only a reiteration of the past and has no unpredictable dimension. This conservative rage does not require high epistemic ability, but only a renewal of ideological trust in essentialism and chauvinism. Rage as hatred that aims to maintain the status quo targets the oppressed and wants to impose silence and submission. This conservative rage appeals to “common sense” and traditional values that emphasize the functioning of society based on harmony and peace. However, these conditions serve to stifle the possibility of conflict that signals the rise of the minority whose purpose is the restructuring of power relationships. Those who experience rage as hatred do not accept “the change of perspective that implies a true collapse of their world” (Dorlin Reference Dorlin2017, 172). This is because this change in perspective could result in a new distribution of power generated by such a conflict. For Étienne Balibar, conflict is a mark of possibility within politics: “Politics are what gives way to conflict without which it has no emancipation value” (Balibar Reference Balibar2003, 14). In this sense, rage as hatred is an obstacle to the emergence of a new politics and is a kind of “extreme violence that is not so much to destroy peace or make it impossible, as to destroy the conflict itself” (14).

It is crucial to analyze the example of gendered rage in South Korea: Feminist witch-hunts, especially in the video-game sector, have long been regarded as a domain reserved for men and are one of the manifestations of male vitriolic rage. For example, one employee who wore a T-shirt with a feminist message was fired. “The Korean video game company Nexon has made the decision to fire her. Beyond the message on the T-shirt, it is the garment itself that has crystallized the hatred of fans of online games” (Poyard Reference Poyard2016). The outbreak of collateral rage as hatred by the male players aims to reaffirm their power over the one who dares to denounce the prevailing sexism. “These players are tirelessly attacking anyone who posts anything vaguely related to women's rights issues, portraying them as ‘Megalia’ supporters who must be fired” (AFP 2018). In addition, virulent cyber-bullying of female singers and actors who are readers, supporters, or performers of the best-selling book and movie Kim Ji-Young: Born in 82 also shows the harmful dimension of collateral rage, which is an engine for backlash. The great success of this book arouses men's fear of the rise of feminism. This male vitriolic rage as hatred aspires to suppress women's voices to conserve patriarchal law. In this way, rage can be reactive and conservative. This vitriolic rage annihilates the possibility of resistance and attempts “the reduction of individuals and groups to impotence” (Balibar Reference Balibar2003, 7). On the other hand, indignant rage increases the power to exist and act, and realizes the possibility of resistance.

The Defiant Dimension of “Escape the Corset”: New Individual Behavior in Everyday Life and Rage as a Layer of Women's Skin

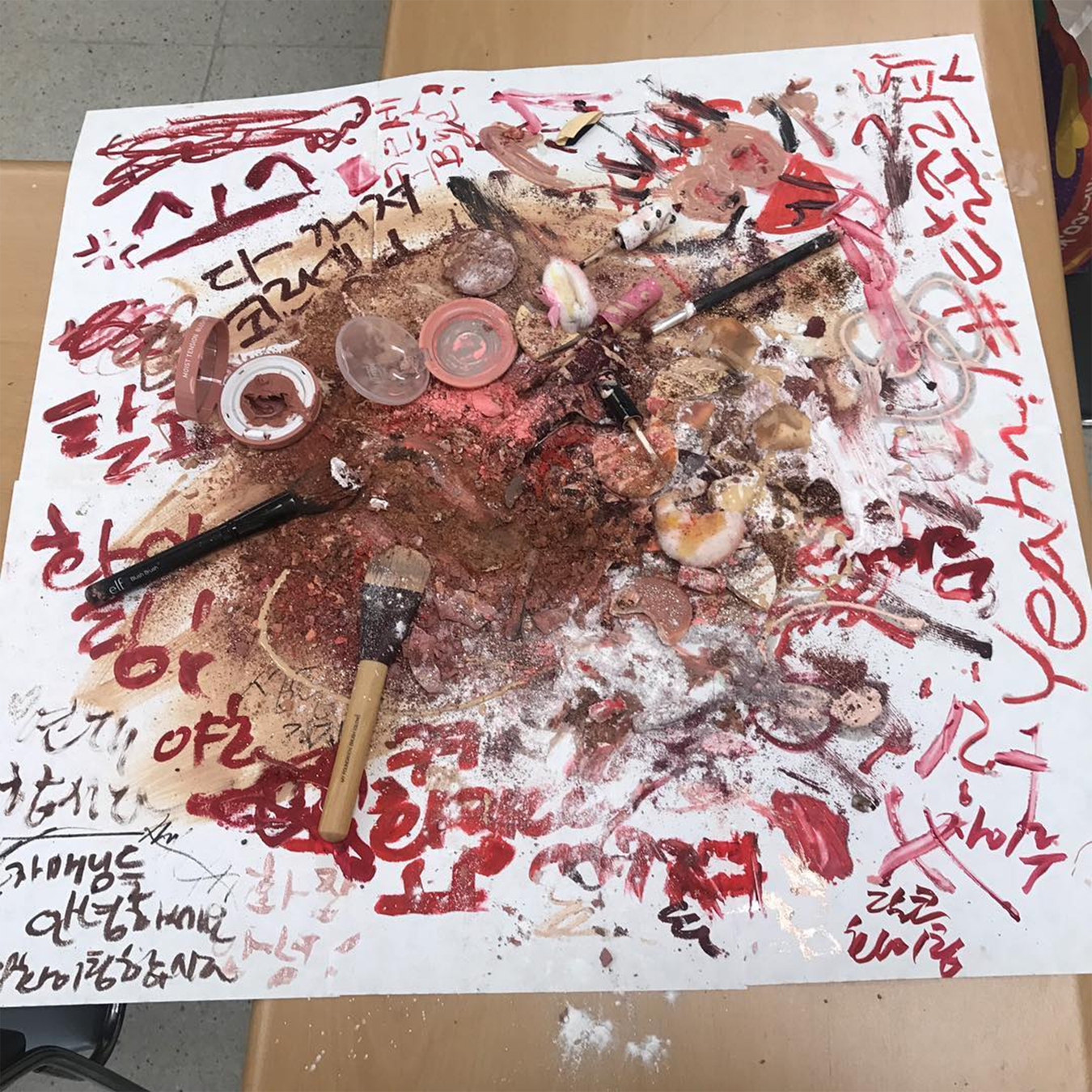

Notably, women are heeding the force of resistance of “Escape the Corset.” Figure 2 illustrates a strategy of feminist sabotage led by anonymous Korean women on social networking services (SNS). They choose Instagram and Twitter, which can guarantee anonymity and maximize the speed of circulating shocking images. By destroying and rendering useless the tools that enhance physical beauty, Korean women dare to break the dictates of beauty. This feminist sabotage, promoted by indignant rage, intends to deconstruct the fantasies of happiness and pleasure purportedly guaranteed by the ideology of beauty and the norm of femininity. Sabotage is “a formula of social combat” (Pouget Reference Pouget1911, 3) and is related to “any act of rendering the work unproductive” (Gide Reference Gide1919, 210). In the selfie culture where one “wants to give them the best version of [one]self” (Bicker Reference Bicker2018), exhibiting well-groomed and well-made-up faces and collecting new makeup products is admirable and a sign of the excellent performance of femininity. For women, caring for their bodies is an eminently important task that determines their value and future. Germaine Greer analyzes the status of a woman as that of a doll: “To her belongs all that is beautiful, even the very word beauty itself . . . she is a doll” (Greer Reference Greer1970, 55). The shocking display of the destruction of makeup products and of women's faces without any makeup and with shaven heads, though, is a rarity in South Korea. Korean women are demonstrating their rage against the imperative to maximize the exchange value of their bodies and internalize the ideology of beauty, which is allegedly both the natural instinct and social duty of women. Korean women have created a field of visibility in which the form of a rebel body proliferates. This feminist movement encourages the practice of indignant rage by denaturalizing this instinct for beauty and dissecting the absurdity of the ideology of beauty that reinforces the subordination of women. “The ideology of beauty,” Wolf writes, “is the last one remaining of the old feminine ideologies that still has the power to control those women” (Wolf Reference Wolf2009, 19).

Figure 2. Makeup products, destroyed by young Korean women carrying out feminist sabotage, posted on Instagram.

The protest movement, or “tal-corset” in Korean, scrutinizes the gendered dimension of the value of feminine beauty that is particular to women. Instead of idealizing and pursuing beauty, the new feminist generation of teenagers and twenty-somethings wants to break the norm of femininity. These young women on whom the beauty norms are most heavily imposed are the protagonists of this movement. For them, the movement aims to change their condition of existence. Destroying makeup products and posting this protest gesture on SNS are considered violent acts that are inappropriate for women and acts of vandalism that harm societal customs. The public reception of such actions includes quite negative actions that exemplify the type of backlash women typically receive from mainstream society. These reactions aim to hinder the emancipation of women and reject “Escape the Corset” (see Yun Reference Yun2019).

Can “Escape the Corset” be called “reverse corset”? This frequent question is based on a fallacy, and it follows the same logic as the ideological term reverse discrimination, which denies the long history of sexual discrimination, structural inequalities, and violence against women. Ignoring the normative force of the imperative of beauty imposed on women, some people devoted to social convention have argued that this movement forces women to abandon their makeup and deprives them of the right to make themselves beautiful. This reversal of the accusation of forcefulness against Korean feminists intends to deny the emancipatory aims of the movement and the revolutionary force of indignant rage. The subtle inculcation of beauty standards for women through the mass media and new media does not seem obligatory but rather projects itself as fun and attractive, whereas demanding participation in the protest movement and the tal-corset exhibition seems crude and rough. Because the protagonists of this movement have neither the predominant power to monopolize the field of visibility nor the authority to define the axiological domain, many people accustomed to absorbing social prejudices devalue the scope of this protest. “Escaping the corset,” launched by the audacity to change the power relationship between women and men and to refuse to become dolls manipulated by men, is what deeply disturbs Korean society and derails the system of male domination.

“Escape the Corset” is a profound way of thinking about the mechanism of taming women with rewards and punishments. Male domination is not only a mode of repression but also one of pampering and pleasure. The very modalities of pleasure, desire, and happiness are also shaped by male-centered parameters. This movement requires a radical rethinking of the female unconscious, women's corporal habitus, and their preferences. It requires amassed psychic energy to reverse an economy of desire and pleasure that had never been doubted. Feminist sabotage aims at proposing another modality of the body and producing another economy of desire and pleasure. Indignant rage is a significant experience for Korean women who resist the patriarchal discourse that has heretofore governed women's existence.

The corset has become a kind of second skin for the female body that sequesters and stifles women's bodies and minds to such an extent that many “Korean women . . . can't leave home without putting on make-up” (Tai Reference Tai2017, and a face without makeup is considered an object of shame that should be covered and hidden from the eyes of others. “Aesthetic surgery continues to be generally understood as a ‘feminine practice’” (Holliday and Elfving-Hwang Reference Holliday and Elfving-Hwang2012, 59). All parts of the female body, even the genital areas, are objects of aestheticization. Instead of the corset being the second skin of the female body, Korean women who are indignant against this male supremacy commit to live and resist as if “rage became a layer of my skin” (Chemaly Reference Chemaly2018, 282).

This rage, which is inextricably connected to women's bodies, can become “an eloquent rage” (Cooper Reference Cooper2018, 6) that reveals political awareness of the unequal situation that threatens women's survival and fundamental rights. Indignant rage is “expressed and translated into action in the service of our vision and our future and is a liberating and strengthening act of clarification” (Lorde Reference Lorde1981/1997, 280). Figure 3 is a feminist manifesto to Escape the Corset written with the devices of the metaphorical corset: These have become the means to advocate women's emancipation. Here, young Korean women encourage other women to take pride in a rebellious body that is impenetrable by the masculine element. They decide to explore this eloquent rage on a handwritten poster, a kind of feminist manifesto, written with makeup products, such as eyeliner, eyebrow pencils, and lipstick. This unpredictable and abrupt change in the use of such corset devices is a subversive action that defies women's recognized domain of thought and action. Korean women decide not to subjugate themselves to the economy of pleasure and desire dictated and manipulated by men. In this way, this makeup powder is a trail signaling the detonation of a feminist revolution.

Figure 3. A feminist manifesto written with eyeliner, lipstick, and eyebrow pencils by the feminist association of Sookmyung Women's University

The Creative Dimension of the Feminist Movement: The Will to Redistribute Power and the Movement's Multidimensional Aspect

The goal of “Escape the Corset” is to destroy the stigmatizing signs of the dominated classes, in whom the value of docility is inculcated, and to break the chain of male domination so that the next generation of women will no longer suffer from male exploitation. This movement is governed by the will to power to become a social prototype that establishes a new economy of desire and meaning. It is not only a movement in the negative sense that seeks freedom from something, but also one that takes power and intervenes in the redistribution of socioeconomic resources. In this sense, “Escape the Corset” is very much related to the project of “the Ambitious Vulva,” the counterpoint to the phallus. The phallus in the Lacanian sense is “a master-signifier” (Lacan Reference Lacan1991, 205) that monopolizes the economy of desire and meaning. To counter the efficiency of the phallus, the ambitious vulva, proposed by a Korean feminist, serves as a deconstruction of the concept of “penis envy” (Freud Reference Freud and Zeitline1940, 171), which condemns the female sex to the status of eternal lacking and inferiority and consolidates male supremacy.

Figure 4 shows the joy of being a girl. This artwork criticizes “the preference for male children due to the strength of the traditional patriarchal family system typical of Confucian societies” such as South Korea's, that long practiced “the selective abortion of female fetuses” (Wolman Reference Wolman2010, 157), and where the photo of a boy proudly displaying his penis is a precious family tradition that emphasizes the importance of the continuity of patrilineality. To counter this obsession with paternal lineage and the superiority of the penis, Korean women dare to lead the Ambitious Vulva project, which states that being a girl is not a fate, nor a curse, but a life of resistance and creation. In Korean society, showing girls’ genitals is considered to risk sexual abuse and is an irreparable shame. Young Korean feminists break this social taboo by drawing artwork that encourages us to think differently and by promoting the Ambitious Vulva project, which is not an imitation of men, nor an identification with the masculine; rather, it puts an end to penis envy, claiming that ambition is not reserved for boys but is a key element to motivate the lives of women plagued by resignation and low self-esteem. The movement proposes that women can supersede men with their abilities and do not need the supreme authority of men's recognition and judgment. Women want to suppress the supreme authority of men by themselves becoming the social prototype of the human. They are not content to become women as confirmed by the authority of men. They try to create another form of the life cycle that is not subjugated by the patriarchal cycle of women's traditional life. The Ambitious Vulva project and “Escape the Corset” have as their common goal the creation of another future for women with respect to their relation to themselves and the world. By launching multiple strategies of resistance, women's rage encounters joy: Women who express themselves and employ their indignant rage feel a cathartic joy that challenges the male value system and uses satirical humor to reveal the absurdity of the patriarchal order. This subversive joy combined with indignant rage results in curiosity for the future and a hope for a more fair and equitable society. “Maintaining the capacity for joy,” Brittney Cooper observes, “is critical to the struggle for justice” (Cooper Reference Cooper2018, 274).

Figure 4. Ambitious Vulva drawn by artist [MicroS] @fff. (Feminism Artist Crew) <fortississimo: Full Fist Feminist >

“Escape the Corset,” motivated by indignant rage, is a mechanism of resistance to what Michel Foucault calls “disciplinary power” (Foucault Reference Foucault2003, 57). “The disciplines,” he writes, “are thus exerted on the bodies in order to make them docile, by assigning them spatially” (Foucault Reference Foucault1975, 173). The corset is the disciplinary device limiting the scope of women's activity and their future. Foucault writes:

In the disciplinary power, the subject-function fits exactly to the somatic singularity: the body, its gestures, its place, its displacements, its force, the time of its life, its discourses, it is all on what comes to apply and exercise the function-subject of the disciplinary power. (Foucault Reference Foucault2003, 57)

The devices of the corset attempt to make a female body that fulfills the function of a sexual object and a doll to handle. “The subjugation thus effected by the disciplines tends to domesticate and produce the individual, by the meticulous and tight regulation of the least of his deeds and gestures,” writes Bertrand Mazabraud. “Each individual thus becomes a kind of well-oiled cogwheel” (Mazabraud Reference Mazabraud2010, 147–48) of the patriarchal system. To no longer be mere cogs in the wheel of society, women must deconstruct the effectiveness of this disciplinary device of the corset, which represents all the microscopic aspects of women's bodies by combining “Escape the Corset” and the Ambitious Vulva project to create a new system of values and change the existing power dynamic.

The Ambitious Vulva project redefines values and attitudes for women and encourages intellectual passion, perseverance, the courage to face challenges, and the maintenance of psychic health in order not to relinquish their power to men. Misogynistic culture reinforces women's physiological and psychic suffering as well as their abandonment of ambition and the confinement of their dreams to romantic relationships and the private sphere as a way of shaping women's docile bodies. This feminist project, however, reconstitutes women's future horizons and explores their infinite capacity. Importantly, “Escape the Corset” and the Ambitious Vulva project do not stem from the neoliberal discourse of self-improvement, which is based on self-profitability and self-exploitation as part of the logic of neoliberal practices of self-government. These strategies of resistance profoundly problematize this discourse of self-improvement.

Neoliberal self-government is essentially male-centered in a Korean society where only boys are encouraged to succeed and obtain positions of power, and where the greatest merit is to be a man. Korean women seek to break this fantasy of a sexist meritocracy. The correlation between neoliberalism and patriarchy has two effects on women: First, it exacerbates women's status as capital in the form of desirable bodies, leading to the sexual objectification of the self, wherein a woman considers her body a natural resource to exploit and a value of exchange in the market economy. This reinforces the performance of hegemonic femininity, the harsh competition for physical beauty, and the formation of “the quantified self” (Swan Reference Swan2013, 85) by which the individual female body becomes a calculable and administrable object and the utilization of female sexuality as if it were a woman's free choice. Second, it is the reinforcement of women's status as capital in the form of reproductive bodies capable of being surrogate mothers for the upper classes. However, “Escape the Corset” and the Ambitious Vulva project virulently criticize this kind of instrumentalization of women's bodies. These discourses are launched with indignant rage, in the sense that Korean women recognize “a resurgence of gender-based discrimination and a widening gender-based wage disparity” (Huh Reference Huh2013, 6), the weak position of women in politics and the economy, and “the low levels of women's participation in decision making” (Hermanns Reference Hermanns2006, 1). Political awareness of the unequal structure of society that limits women's rights and the quality of women's lives is a common point that the feminist project and the movement of the four refusals attempt to critically analyze and overcome.

The movement of the four refusals, known as the 4B movement,Footnote 4 allows for another type of creative refusal by women wherein marriage, romantic relationships, sexual intercourse, and childbirth—all of which endorse the efficiency of the patriarchal structure—become objects of rejection and nonacceptance by women. The 4B movement has feminist implications, whereas the “Three Abandon Generation,” which refers to a generation that gives up courtship, marriage, and children, represents only the defeatism of men. Young Korean men are resigned to the law of the father and are too overwhelmed by despair to challenge the efficiency of the conventional order, but young Korean women dare to make this refusal, which is a voluntary and subversive gesture to abolish the law of the father. Abandonment and refusal have different gender dimensions. “To refuse can be generative and strategic, a deliberate move toward one thing, belief, practice, or community and away from another. Refusals illuminate limits and possibilities, especially but not only of the state and other institutions” (McGranahan Reference McGranahan2016, 319). These four modalities have long been the determinants of women's traditional life. “Saying no is the minimum form of resistance,” writes Foucault. “We must say no and make this ‘no’ a form of decisive resistance” (Foucault Reference Foucault1994, 741). In this sense, the 4B movement denounces the masculine violence behind romantic and idealistic narratives of family and love. The marriage regime and heteronormative relationships between women and men are what naturalize the submission of women to men and justify the exploitation of women's work by men. Love, sex, marriage, and childbirth are tactics to maintain the patriarchal system that guarantees the birth rate (see Maybin Reference Maybin2018). In this sense, these four modalities are devices of the power of “biopolitics” (Foucault Reference Foucault2004), which seeks to control the population through the domination of women's bodies.

Instead of integrating with the order of the father, young Korean women deploy this movement of “creative refusal,” which “is often a part of political action, of movements for decolonization and self-determination, for rights and recognition, for rejecting specific structures and systems” (McGranahan Reference McGranahan2016, 320). This creative and subversive refusal dissects the culture of rape, present even in the context of a couple's relationship,Footnote 5 and denounces the high rate of domestic violence. Korean women rage against Korean men who treat women as sexual objects to be humiliated and as trophies to be displayed among men for obtaining higher rank and recognition among the male community. Indignant rage refines the cognitive and theoretical power of resistance and multiplies the practices of protest. These three feminist movements—“Escape the Corset,” the Ambitious Vulva project, and the 4B movement—aim to create another modality of women's life cycle that no longer depends on men and to invent a new form of a nondocile and resistant body. In the practice of a new modality for the three movements, which function as the fulcrum for a new feminist subjectivity, women stop being obsessed about weight and appearance through “Escape the Corset” and share the recipe to strengthen their intellectual and physical capacities through the Ambitious Vulva project. The 4B movement enables them to pursue a new life path. The women of this movement decide to live either alone or together, in both cases forming a community of women refusing marriage.

Women's rage is not a one-dimensional force, but a multidimensional one, in the sense that the status quo is restructured by the revolutionary force of indignant rage that cultivates a range of strategies of feminist resistance. “Resistance is not only a negation: it is the process of creation: to create and recreate, transform the situation, actively participate in the process, which is resisting” (Foucault Reference Foucault1994, 741). From this perspective, these movements form epistemic and axiological creativity and the ontological-political power of women. Korean women are trying to deploy the politics of rage. As Balibar observes, “[t]he possibility of politics is essentially linked to the practices of resistance, not only negatively, as a challenge to the established order, a demand for justice, but positively, as a place in which active subjectivities and collective solidarities are formed” (Balibar Reference Balibar2003, 7). Indignant rage is an incubation of feminist corporeal agency that undermines the patriarchy.

In this way, Korean women's indignant rage creates a disobedient body that destabilizes both oneself and the order of reality. Women's rage incubates axiological, epistemological power to disrupt the prevailing order of values and meaning monopolized by men and to promote a new form of knowledge and values created by women who do not subjugate themselves to men. Rage is an “ontological violence” (Žižek Reference Žižek2008, 68) that provides access to completely new ways of existing and thinking. Rage as ontological violence serves to manifest sociopolitical struggles and to “develop the un-heard, the hitherto un-said and un-thought” (Heidegger Reference Heidegger2000, 65). In this sense, enraged Korean women intervene in the lexical, axiological, and ontological field. They create a myriad of lexical tactics such as tal-corset in Korean, an ambitious vulva to subvert the phallic economy of meaning, and new practices of self and new forms of women's bodily lives to affirm the potential of another modality of being. Furthermore, the Korean feminist multitude proposes an alternative form of value such as the will for power, curiosity, courage, and spirit of challenge. It turns out that women's rage marks the advent of an unprecedented modality of feminist creative agency.

Subversion and Creation of the Phallic Economy of Desire and Meaning

In this article, I examined women's rage, which has upset the patriarchal, Confucian, and misogynistic society in South Korea. Control of women's bodies is intense and varied, reducing women either to the status of capital as sexually exploitable bodies for the desire of men or as fertile bodies that guarantee patrilineal perpetuation. The effect is so extreme that the oppressive devices of the corset have become the second skin of the female body. In order to break away from this second skin, Korean women are deploying the politics of rage. The politics of rage will be effective only to the extent that a simultaneously instant and intense rage and a persistent and justifiable indignation are maintained. If rage is to become a protective layer of women's skin in connection with indignation, this indignant rage must become an incubator of resistance and creation. Under the pressure of the prevailing ideology of beauty and the glorification of corporal discipline, Korean women are developing “Escape the Corset,” which not only encourages the cognitive capacity to analyze critically the standards of physical beauty, but is also a practice of resistance against the values traditionally assigned to women. Indignant rage is a core of creativity that promises to result in new individual behavior to correspond to this unprecedented epistemological and ontological value attributed to women. Indignant rage aims to change the power dynamic. In contrast, rage as hatred—a conservative rage—annihilates the possibility of resistance and of changing the established order.

“Escape the Corset,” the Ambitious Vulva project, and the 4B movement are motivated by rage as indignation. These three strategies of resistance call into question the phallic economy of desire and meaning, and they foster the creation of the epistemological, axiological, and ontological capacity of women. Indignant rage is a feminist corporeal agent that creates a rebellious body aiming to deconstruct the patriarchal system. The ultimate objective of this politics of rage is to change normative femininity, end the efficient patriarchal structure, and provide us with the unprecedented creative potential to renew our courage and challenge ourselves to think and to act.

Ji-Yeong Yun is an associate professor at the department of Philosophy at Changwon National University, Changwon, South Korea. She received her PhD from the University of Paris I, France. Her research interests include feminist philosophy, new materialist feminism, and anthropocene feminism.