Entering into Anton Webern’s twelve-tone music and its complex reception history is like entering into combat with the Hydra: cleave off one head of the Webern myth, and two more grow in its place, often swinging at you from opposite directions. Understandings of late Webern range widely, from that of an intrepid pioneer who, invigorated by his amicable rivalry with his former teacher Arnold Schoenberg, like the ‘Sphinx’ paved the way for the post-war avant-garde (Reference Stravinsky and CraftStravinsky and Craft 1959: 79), to a staunch preserver and guardian of the Austro-German musical tradition committed to pouring ‘new’ music into ‘old’ forms (see Reference BaileyBailey 1991); from an abstractionist with affinities with the cubism familiar from the paintings of Paul Klee (see Reference PerloffPerloff 1983), to a composer deeply inspired by the programmatic landscape tropes evoked in so many of the poems that he chose to set to music (see Reference JohnsonJohnson 1998 and Reference Johnson1999); from a frigid and elitist rationalist looking through the falseness of Romantic subjectivity (see Reference EimertEimert 1955: 37), preoccupied by ‘logic’, ‘order’, and ‘comprehensibility’ (see Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963), to a relentless ‘expressionist’ (see Reference QuickQuick 2011; Reference CookCook 2017) and ‘middle-brow modernist’ (see Reference MillerMiller 2020), with a heightened concern for the sensuous, ephemeral, ineffable qualities of music as sound and for whom reportedly ‘knowledge of [the] serial implications was not required for a full appreciation of [his] music’ (Reference StadlenStadlen 1958: 16); or, from a fairly apolitical citizen, to someone who forsook his support for the social-democratic movement as conductor of the Labour Symphony Concerts to become ‘an unashamed Hitler enthusiast’ (Reference RossRoss 2008: 323).

So how, then, to face the Hydra of mythologies surrounding Webern’s twelve-tone work? Taking the view that, as the polemical clamour in the halls of Darmstadt and beyond has long faded away, it is otiose to keep chopping heads in an attempt to kill off the Hydra once and for all, in this chapter I wish to lay down the sword and take a step back from the embattled scenes of the past in search of a broader vantage point. Bringing biographical insights into dialogue with analytical, philological and philosophical perspectives, this chapter argues that the crux in understanding late Webern lies in understanding that the competing, often contradictory images of the composer that have emerged pose no real contradictions after all. Instead, in the same way that the Hydra’s separate heads are essentially connected entities, these different images are best understood as mediated with one another on a deeper level, representing different aspects of one and the same all-pervasive aesthetic concern: musical lyricism.

A critical shibboleth in Webern scholarship, the category of the lyric is notoriously difficult to define. Cutting across different musical styles and genres, the lyric permeates all levels of Webern’s compositional thinking, posing considerable methodological and interpretative challenges. That said, these challenges can be reframed as heuristic opportunities and a chance to rethink the very essence of Webern’s musical imagination. As Reference AdornoTheodor W. Adorno (1999b: 93) once succinctly noted: ‘Webern never departed from [the] idea [of absolute lyricism], whether consciously or not’. In this chapter, I seek to explore, in a perhaps appropriately Webernian manner of ‘six aphorisms’, how the concept of the lyric can be understood to operate in the context of Webern’s twelve-tone music. My aim is thus not to provide a systematic overview of Webern’s late repertoire, nor do I wish to put forward any interpretations of individual works. Instead, I seek to bring into focus and trace out some of the discursive levels of the lyric as a category that arguably, indeed, strikes right at the heart of the Hydra.

Lyricism as Aesthetic Self-Identity

I wish to begin with a rather curious fact: although it seems uncontroversial to regard Webern as a genuine musical lyricist – Adornians might be inclined even to say the most important musical lyricist after Franz Schubert – interestingly Webern only began to brand himself publicly as such when Schoenberg had disclosed to the members of his circle the method of twelve-tone composition in the early 1920s (see Reference HamaoHamao 2011). That Webern would forge a public identity as a musical lyricist while simultaneously developing a new identity as a twelve-tone composer is not a purely historical contingency. At the time Webern started to experiment with Schoenberg’s new method (see Reference ShrefflerShreffler 1994: 285), he was preparing many of his earlier works for publication, following his signing with Universal Edition in 1921, including the Six Bagatelles for string quartet (to become op. 9). The score appeared in print in the summer of 1924, accompanied by an evocative and often cited preface by Schoenberg. In it, Schoenberg, pre-empting potential reservations against the bagatelles’ extreme brevity, asserted that their aphoristic nature is the result of an attempt to ‘express a novel in a single gesture, joy in a single breath’, before concluding that ‘such concentration can only be present in proportion to the absence of self-indulgence’. Built into these lines is an emphatic claim. In juxtaposing the brevity of Webern’s ‘poems’ with the lengths of ‘novels’ (all quotes cited after Reference MoldenhauerMoldenhauer 1978: 193), Schoenberg advocated for an understanding of the bagatelles as valid contributions to the formation of the musical aphorism as a genre in its own right (see Reference ObertObert 2008).

Schoenberg’s preface, albeit itself somewhat elusive and not devoid of inconsistencies (see Reference Schmusch and ObertSchmusch 2012), may have made some impression on the members of the Schoenberg circle, especially on Adorno. In 1926, the year after he had joined the circle as a private student of Alban Berg and Eduard Steuermann, Adorno published a review essay on the premiere of the Five Pieces for Orchestra op. 10, conducted by Webern himself on 22 June in Zurich, which – with explicit reference to Schoenberg’s preface – identified the concern for ‘absolute lyricism’ as the linchpin of Webern’s aesthetic (Reference Adorno, Tiedemann and SchultzAdorno 1984: 513). Adorno’s essay, initially projected as a ‘theory of the miniature’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 35), can thus be read as an attempt to reinforce the interpretative vision proffered in Schoenberg’s preface and to put it on sturdy philosophical legs.

Yet despite this intellectual kinship, Adorno was quite anxious about how Webern and Schoenberg might respond to his essay. This was for a good reason, as glimpses into his correspondence with Berg reveal. Well before the premiere took place, on 25 December 1925, Adorno had shared with Berg that he was keen to ‘measure the tragic depth of his [Webern’s] [aesthetic] position’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 35), which he was later to locate in his essay in Webern’s tendency to contract the dialectical principle into the semblance of immediate expression (Reference Adorno, Tiedemann and SchultzAdorno 1984). (It is quite conceivable that Adorno is here taking his cue from G. W. F. Hegel, who in his Lectures on Aesthetics (Reference Hegel1975: 1133–4, emphasis in the original) discussed the concept of ‘concentration’ as the ‘principle’ for the lyric, admonishing that ‘between an almost dumb conciseness and the eloquent clarity of an idea that has been fully worked out, there remains open to the lyric poet the greatest wealth of steps and nuances’.) When he did not receive any feedback from Berg on this specific matter, Adorno increasingly feared that his critical take on Webern may have led to some serious irritations, possibly alienations between him and the Schoenberg circle. It was thus ‘particularly gratifying’ to him to eventually see that Berg, ever generous in his judgements and support, had only kind and approving things to say about the essay upon its publication. Reading between the lines of Berg’s response indicates, however, that Webern and Schoenberg may have been less enthusiastic. Alluding to past frictions and tensions, Berg warned Adorno that ‘a few words and turns of phrase … will once more cause offence’. In his reply, aiming to smooth potentially agitated waters, Adorno assured Berg that he had ‘increasingly warmed to his [Webern’s] works’ over the course of time and that ‘some of them … truly contain some of the purest, most beautiful lyricism that there is’, before setting great store by the fact that it is ‘precisely’ the ‘forlornness’ so palpable in Webern’s music, both at a ‘private’ and ‘historical’ level, ‘that lends it its radiance’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 57–60). It is in this sense, he implied, that his (few) critical remarks would be misconstrued if taken as self-indulgent cavilling. Instead, his initial instinct to cast Webern’s concern for ‘absolute lyricism’ in an ambivalent – to recall his own choice of wording, ‘tragic’ – light, pace Schoenberg’s much more affirmative interpretation, is undergirded by the hope that his review may actually help bolster (rather than damage) Webern’s reputation. As Adorno once envisioned with confidence, his work on Webern, not despite but because of its critical overtones, would ‘tactically … certainly be of advantage to him [Webern]’ (Reference Adorno, Berg and LonitzAdorno and Berg 2005: 35, emphasis in original).

Indeed, there is good evidence that Webern recognised the ‘tactical’ value of Schoenberg and Adorno’s writings on his aphoristic music and in fact aligned himself with their interpretations in moments where he found himself cast in a defensive position. So, for instance, in a letter to his publisher Emil Hertzka from 6 December 1927, Reference WebernWebern (1959: 15) used an expression that palpably echoes Adorno’s phrase of ‘absolute lyricism’: ‘I know, of course, that my work has very little importance regarded purely commercially. The cause of this lies in its almost exclusively lyrical nature [!] up to now; poems do not bring in much money, but after all they still have to be written.’ And in a letter dated 4 September 1931 to the conductor Hermann Scherchen, Reference WebernWebern (1945/6: 390) launched an apologetic defence of his aphoristic works clearly alluding to Schoenberg’s preface: ‘sometimes it takes a whole novel to express a single thought; and sometimes no less substantial or few thoughts are condensed into a single short poem’.

The striking confidence with which Webern, at this critical stage in his creative development, projected a public image of himself as a musical lyricist opens up some wide-ranging perspectives. Perhaps the question about Webern’s lyrical style is not one of ‘style’ at all, but rather his attitude towards the stylistic means and devices available to him at a given time and the ‘ideas’ he sought to express. In this precise sense, Webern did not compose in a certain ‘style’ – the style of ‘dodecaphony’, ‘free atonality’, or ‘late Romanticism’ – but in the ambit of lyricism. Much of the fascination that thus comes with Webern’s music lies in the sheer plethora of unique strategies that it presents to articulate highly expressive and distinctive physiognomies of the lyric.

Lyricism as Space

For the purpose of studying the ways the category of the lyric has shaped Webern’s twelve-tone thinking, his famous lecture series on The Path to the New Music (1932–3) provides some first insights. Although the lyric finds no mention in it, Webern can be shown to interpret some of the key concepts and ideas therein expounded in a decisively ‘lyrical’ light. To illustrate this issue, Webern’s curious ashtray example, presented in his lecture of 26 February 1932, is a particularly pertinent case in point. Having advocated the view that the ‘urge to create coherence [Zusammenhang] has … been felt by all the masters of the past’ (a view iterated at various stages), Webern (once again) finds himself in a position where he feels pressed to offer an explanation of what the concept of musical coherence means. Not a man of words, Webern, apparently impromptu, seeks to illuminate the issue as follows: ‘An ashtray, seen from all sides, is always the same, and yet different.’ And he adds: ‘So an idea should be presented in the most multifarious way possible’ (Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963: 53).

While one might imagine (with some delight) Webern swirling an ashtray through the air – first holding it up still, before flipping it around again and again – the question begins to emerge what this discussion really reveals about his understanding of musical coherence. Indeed, many of the examples that Webern presents – the treatment of fugal subjects in J. S. Bach’s Musical Offering, the motivic-thematic processes in the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and the developing variations characterising Schoenberg’s First String Quartet op. 7 – suggest a reading of the term that renders it essentially a linear-developmental principle hingeing on the notion of becoming (see Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963: 35, 52, and 58). Positing these examples with respect to Webern’s discussion might thus lead to an expectation that he would describe the ashtray as the subject of an (irreversible) temporal process – for example, by pondering what it would take for it to be transformed into a different object, say, a pile of fragments. This, however, is not the case. Instead, Webern’s discussion implies that it is the observer’s perspective on the ashtray that changes, while the ashtray itself remains the same. Thus, for Webern, the ‘multifariousness’ that he contends should arise from the presentation of a single musical ‘idea’ does not – in contrast to his many music examples – originate from a genealogical but a perspectival mode of musical thinking, a mode of thinking that Reference Ligeti, Metzger and RiehnGyörgy Ligeti (1984: 104) saw as the fundamental crux of Webern’s late aesthetic: the tendency ‘to treat musical time in such a way as to treat it as a spatial phenomenon’.

These nested inconsistencies can also be discerned in other parts of Webern’s lectures, such as in his famous discussion of Goethe’s ‘primeval plant’ (Urpflanze). Enshrouded in some esoteric-philosophical ideas about nature and art’s relationship to it, in Webern’s hands the Goethean primeval plant shines forth as nothing less than a (vexed) mirror of aesthetic self-legitimation. On some level, Webern conveniently exploits the genealogical epistemology built into it, both in historical and musical terms. In particular, he avers that the development of the twelve-tone method is the logical consequence of music history as evolutionary progress, and he moreover contends that the concern of past composers ‘to create unity in the accompaniment, to work thematically, to derive everything from one thing’ breathes new air in the domain of twelve-tone composition. However, in other moments of his discussion he, inexplicitly, reverses this genealogical notion into its opposite, a static one. Insomuch as the twelve-tone technique, as an ‘underlying’ method, always already guarantees ‘unity’ and ‘comprehensibility’, he argues, for instance, it has become possible to ‘treat thematic technique much more freely’, before once more making recourse to Goethe’s primeval plant but now – notably – as a paradigmatic model of structural identity: ‘the root is in fact no different from the stalk, the stalk no different from the leaf, and the leaf no different from the flower: variations of the same’ (Reference Webern and ReichWebern 1963: 40 and 53).

By pointing out these subtle yet fundamental shifts in his explications, I do not wish to suggest that there is anything wrong (or right) with Webern’s discussion. My concern is rather with the ways in which these shifts reveal a constitutive tension in Webern’s musical thinking, one that arguably tends to become all too quickly obfuscated once the categories and ideas expounded in his lectures are taken at face value or considered no more than blueprints of Schoenberg’s theorisation of the concept of musikalischer Gedanke (see Reference Schoenberg, Carpenter and NeffSchoenberg 1995). To rephrase the issue in a heretical way: what would be gained, what would be lost, by taking the sceptical-contemplative view that the late Webern may not have understood himself – or, for that matter, Schoenberg?

Lyricism as ‘Variations of the Same’

In seeking to explore the implications of his ashtray example and his discussion of the Goethean primeval plant, it seems apt to attend to Webern’s ubiquitous use of structural symmetries and permutations. Often couched in terms of a complex dialectic between ‘construction’ and ‘expression’, these salient features in Webern’s music have been the subject of enormous analytical efforts. In the following, I will draw upon two theoretical conceptions of harmonic space – the intervallic and transformational ones – as ways of exploring how Webern’s axiomatic concern for ‘variations of the same’ can be considered in analytical terms.

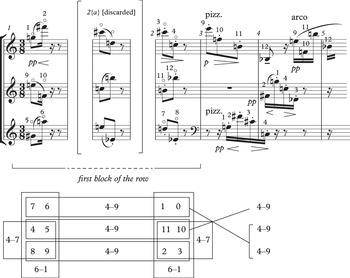

Figure 6.1 presents the opening of the string trio fragment M. 273, Webern’s second fully fledged foray into the ‘composition with twelve notes’ in the domain of instrumental music, drafted in spring 1925 a few months after the completion of the Kinderstück M. 267. These bars set up a ‘traditional’ discursivity that evokes the expectation of a ‘developmental’ motion: a two-bar fanfare-like homophonic ‘introduction’ is eventually broken up and ‘liquidised’ into a quasi-polyphonic presentation of distinct ‘motivic’ gestures. In what sense do these two units ‘cohere’ (zusammenhängen)? At first, this passage seems to instantiate a typical case of ‘developing variation’: the gestures emerging in b. 3 are individuated and timbrally distinct yet still operate within the harmonic and rhythmic scope set out in the opening two bars. More specifically, they are based on the melodic contents articulated in bb. 1–2, in other voices: violin 1 harks back to violin 2; and violin 2 and cello hark back to violin 1. This suggests that, in bb. 3ff., Webern was keen to expand the harmonic-rhythmic world conjured up in the opening two bars in a new textural guise.

Figure 6.1 Webern, string trio fragment, M. 273, bb. 1–5 and 2{a}, accompanied by some analytical annotations, based on a transcription of the manuscripts and sketches as provided in Reference WörnerWörner (2003: 75 and 88); the sources are archived at the Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel

Yet Webern’s sensibilities for variation arguably cut a layer deeper. The opening two bars present two complementary chromatic six-note aggregates, effectively yielding the first iteration of the fragment’s twelve-tone row: G♮, F♯, C♯, C♮, G♯, A♮, D♮, E♭, E♮, F♮, B♮, B♭. As Reference WörnerFelix Wörner (2003: 77–80) has pointed out, this row is fashioned from three consecutive statements of the symmetrical tetrachord 4–9, the constructive significance of which is highlighted by the linear motions of each voice. On the most fundamental level, one can thus understand bb. 1–2 as establishing two diametrically opposing ‘harmonies’: 6–1 (for the sake of simplicity hereafter conceived as the subset 4–1) featuring the maximised semitone (ic1), and 4–9 featuring the maximised tritone (ic6). Approached through the lens of pitch-class set theory, it is thus possible to read both chords as part of a strategy to stake out the full scope of the interval vector space, with 4–7 (in the second violin and cello) acting as the oscillating centre between both poles (Table 6.1). A fingerprint of Webern’s free-atonal and dodecaphonic music, such interval vector space opens up a vast array of possibilities to move, in a Schubertian manner, through ‘variations’, within a defined landscape.

Table 6.1: Interval vectors of the 4-7 tetrachord family, based on Reference ForteForte (1973)

| Forte number | interval vector | interval succession |

|---|---|---|

| 4–1 [0123] | 3 2 1 0 0 0 | 1-1-1 |

| 4–3 [0134] | 2 1 2 1 0 0 | 1-2-1 |

| 4–7 [0145] | 2 0 1 2 1 0 | 1-3-1 |

| 4–8 [0156] | 2 0 0 1 2 1 | 1-4-1 |

| 4–9 [0167] | 2 0 0 0 2 2 | 1-5-1 |

Closer examination of these bars, including Webern’s revision of b. 2{a}, further suggests that the interval vector space may be construed as itself being, rather than the origin, the emergent product of a ‘variational’ process. As the philological reconstruction provided by Reference WörnerWörner (2003: 70–95) reveals, Webern revised b. 2{a} so as to complement the six-note aggregate presented in b. 1 and hence to obtain a statement of the full chromatic scale. This adjustment, however, comes at the price of what seems at first an infelicitous inconsistency: the first trichord in b. 2 changes from 3–3 (used throughout bb. 1 and 2{a}) to 3–2. Yet interestingly enough, when cast in the light of Klumpenhouwer network theory (‘K-nets’), this new chord (3–2) can be interpreted as sharing the same transformational logic as the opening trichord (3–3) from b. 1 (Figure 6.2a). It is, of course, not uncommon that chords with different interval properties feature an identical set of transformations. In this specific context, however, it seems not implausible to ascertain a certain degree of transformational consistency. For instance, the tetrachords 4–1, 4–7, and 4–9 shown in Figures 6.2b and 6.2c can all be construed as hingeing on the same (strongly isographic, <T0>) transformation as said trichords from bb. 1 and 2. This analytical perspective has implications for an understanding of the semitone (ic1) which so conspicuously permeates these bars. While the ‘relational abundance’ of K-nets prompts intricate questions (not least) about the phenomenological viability of K-net-derived analytical insights (see Reference BuchlerBuchler 2007), this perspective renders the semitone conceivable as the ‘identical’ subject of a transformational ‘variation’. Thus what one hears on a material level are de facto actualisations of virtualities, indeed not dissimilar from Gilles Deleuze’s conception of the term as the differential condition of all that which manifests itself as real experience (Reference DeleuzeDeleuze 1997: chapter 4; see also Reference AhrendAhrend 2017: 34–9). Such observations offer some fascinating glimpses into the philosophical and compositional complexities of Webern’s lyrical imagination, suggesting that his concern for ‘variations of the same’ is inextricably bound up with a fundamentally altered conception of musical temporality and phenomenology.

Figures 6.2a, b, c Klumpenhouwer network interpretation of Webern’s string trio fragment M. 273, bb. 1–2 and 2{a}, as defined by Reference LewinLewin (1990) and Reference KlumpenhouwerKlumpenhouwer (1991)

Lyricism as Song

Within the topographies of Webern’s lyrical thinking, the genre of the song marks a particularly intimate place, to the extent that its significance in the context of his adaptation of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone method can hardly be overstated. At the time Schoenberg ‘discovered’ the twelve-tone technique, Webern in fact had been on a long hiatus from the composition of instrumental music. As Anne Reference ShrefflerShreffler (1994: esp. 279) has pointed out, Webern’s decision to exclusively focus on the composition of texted music following the completion of the Three Little Pieces for Violoncello and Piano op. 11 in June 1914 was above all a response to the struggles he felt during these years to compose longer works. When Webern thus turned, in the summer of 1922 with the song ‘Mein Weg geht jetzt vorüber’ op. 15/4, to the ‘composition with twelve tones’, this was not born out of an acute artistic ‘crisis’; rather, the twelve-tone technique primarily served him then as an expressive device, one of many in his toolbox, to convey musically the semantic qualities and envoiced subjectivities he sensed radiating from the poems he chose. (This may help to explain why, baffling to many, Webern’s adaptation of Schoenberg’s technique did not develop in a stepwise, evolutionary fashion but took place over many years with varying degrees of engagement and complexity.)

The fragment M. 276 for a song based on Peter Rosegger’s poem ‘Dein Leib geht jetzt der Erde zu’ allows some insightful glimpses into Webern’s working method at this critical time in the genre of texted music. As its place within the sketchbook (known as ‘Sketchbook i’) reveals, Webern began drafting ‘Dein Leib geht jetzt der Erde zu’ during the summer of 1925, at a time when he was working intensively on songs that were later to become his cycles opp. 17 and 18 (cf. Reference LynnLynn 1992: 76–9; Reference BuschBusch 2020: 211–3); as the instrumentation suggests, it seems in fact probable that the song was initially intended to be included as part of the op. 17 cycle which contains with ‘Liebste Jungfrau’ another song set to a poem from the same source, Das Buch der Novellen i (cf. Reference ShrefflerShreffler 1994: 321; Reference KaiserKaiser 2013: 106–8).

The sketch begins with a melody which is based on all twelve tones of the chromatic scale (Figure 6.3a). In the system underneath, Webern set out a(nother) twelve-tone row (placed in the centre of the sheet) which conspicuously features some of the intervals from the melody (Figure 6.3b): C♯, C♮, B♮, E♭, B♭, A♮, G♯, G♮, D♮, F♯, F♮, E♮ (Figure 6.3c). Webern, then, subdivided the row into three smaller units: two hexachords (as indicated by a double bar line), three groups of four notes (as indicated by two dashed bar lines), and four groups of three notes (as indicated by slurs). In fact, the interval content of the row reveals that it is vertically mirrored. As a corollary to these intervallic properties, the row features three symmetrical tetrachords – 4–1 (B♭, A♮, G♯, G♮), 4–7 (C♯, C♮, F♮, E♮), and 4–9 (C♮, B♮, F♯, F♮) – staking out, once more in the way illustrated in Table 6.1, the entire interval vector space (Figure 6.3d). These observations suggest that Webern did not conceive of the symmetrical dispositions of the twelve-tone row in a vacuum. While it is difficult to ascertain the exact relationship between the melody from the first system and the gestation of the row, it seems not far-fetched to understand the row as the product of a concern to first of all distil some of the intervallic features as borne out by the compositional ‘impulse’ he perceived when reading the poem, and to make these features constitutive for the whole song. In this sense, the ostensibly ‘rational’ construction of the row with all its absorbing symmetrical properties originates from a poetological – ‘irrational’ – place.

Figures 6.3a, b, c, d Webern, ‘Dein Leib geht jetzt der Erde zu’, M. 276: transcription of the sketch of the first melodic idea and twelve-tone row, ‘Sketchbook i’, p. 11, archived at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, accompanied by some annotations highlighting the constitution of the interval vector space as illustrated in Table 6.1

After defining the basic harmonic material, Webern begins with the actual compositional process of the song (as it were). The sketches are complex, showing various drafts for individual passages. However, it is not difficult to stitch the sketches together into what could be considered a ‘complete’ version of the first stanza (Figure 6.4; cf. also Reference AsaiAsai (2021), 144–9). Through this reconstruction, it becomes evident that the musical fabric is fashioned out of two independent twelve-tone tracks (based on the same row, P0), set out in the voice and the instrumental group. This gives the effect that the instrumental group is an iridescent reflection of the vocal line, thereby intensifying the elegiac qualities evoked by the text.

Figure 6.4 Reconstruction (modified transcription) of Webern’s fragment ‘Dein Leib geht jetzt der Erde zu’, M. 276, ‘Sketchbook i’, p. 11, archived at The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Webern begins the compositional process by setting out the melody for the first two lines (which right from its inception seems to be set in stone): ‘Dein Leib geht jetzt der Erde zu, / Woher er ist gekommen.’ Webern is here clearly guided by a concern to use all twelve notes of the row, and to do so in such a way that the twelve notes are distributed equally over the two lines. This concern to map the twelve notes onto the formal structure of the poem, however, may have posed some practical challenges for Webern insomuch as the number of syllables used in each line (eight and seven, respectively) does not match the number of notes reserved for each of them (six). The compositional solution Webern finds is insightful. Rather than ignoring the irregular number of syllables and sticking rigorously to the distribution of one note per syllable, he makes a few adjustments: he repeats the first, second and seventh notes so as to maintain the even distribution of six plus six notes per line. In this way, he aligns the presentation of the twelve-tone row with the predetermined formal structure of the text. Curiously, for the stanza’s third and fourth lines – ‘Der Seel’ wünscht man die ewige Ruh’, / Bei Gott und allen Frommen’ – Webern at first seems to take a more flexible approach. He reserves for the nine-syllable third line the first seven (not six) notes of the row; and for the seven-syllable fourth line he in fact adds one note, setting out the word ‘allen’ as a three-note melisma. As a result, the row is used up before the fourth line has come to an end. But this decision, too, is quite conceivably motivated by a form-syntactical consideration. The notes used for the line’s last word ‘Frommen’ are yet again recruited from the beginning of the row, lending the stanza a framing effect which is possibly intended to contribute to a sense of closure while at the same time offering interlocking options for continuation.

Webern appears to have abandoned his work on the song at this advanced stage. The reasons may remain unknown. It would be his last setting of a poem by Rosegger. He would thereafter devote himself exclusively to the poetry of Hildegard Jone, an artistic connection that would inspire with the Three Songs from ‘Viae inviae’ op. 23, the Three Songs op. 25, Das Augenlicht op. 26, and the two Cantatas opp. 29 and 31, some of his most iconic explorations of the dialectical relationship between vocal expressivity and musical construction.

Lyricism as Silence

The Symphony op. 21, completed in June 1928, three years after the string trio fragment M. 273 and ‘Dein Leib geht jetzt der Erde zu’ M. 276, is commonly considered to mark a sea change in the development of Webern’s late style. Already some cursory glimpses into the field of metaphors that emerged right after Webern’s death may give a taste. In his 1949 monograph on Schoenberg and His School, Reference LeibowitzRené Leibowitz (1949b: 210–7) discerned in Webern’s Symphony a turn to ‘greatest purity’ and an ‘extraordinary economy of means’, identifying in the work’s ‘almost complete immobility’ a tendency towards the ‘emission of isolated tones’. This mode of reception, which would only a few years later inspire Herbert Eimert’s (controversial) coinage of the term ‘pointillism’, was also shared by Reference Adorno and SchwarzAdorno (2015: 18) who, though considerably more sceptical in his philosophical assessment, similarly saw in the Symphony a ‘peculiar [penchant for] simplification [eigentümliche Simplifizierung]’ and sense of ‘utmost demureness [grösste Zurückhaltung]’. How profoundly puzzling and enigmatic Webernians found the stylistic veneer of the post-op. 21 works is perhaps particularly apparent in a fervid exchange between Franz Krämer and Glenn Gould:

Krämer: I was … I was, you know, studying with Webern one … one season, in a class with other people …

Gould [affirmatively]: Hm.

Krämer: … and he was a very shy person …

Gould [affirmatively]: Hm.

Krämer: … as his music is: rather shy.

Gould [sceptically]: ‘Is this shy music?’ [Gould plays the second movement from Webern’s Piano Variations op. 27. When he stops playing both begin speaking simultaneously.]

Gould: ‘It’s not exactly shy music, you know.’

Krämer [inaudible]: … but it’s spare, it’s … it’s … it’s … it’s … I … I’d still call it … rather, rather …

Gould: Well, it’s … it’s reticent …

Krämer: … it’s small …

Gould: … it’s reticent, really.

Krämer: … reticent – and he was very, very reticent. And there is no doubt about that.

Gould: This is shy music … [Gould plays the first movement from Schubert’s Fifth Symphony, bb. 1–47.]

Krämer [interjecting]: Schubert? (Reference Kroiter and KoenigKroiter and Koenig 1959)

Purity, simplification, reticence. Despite the profusion of metaphors used to describe Webern’s ostensibly new lyrical style, there is a shared understanding that the post-op. 21 works evoke a strange sense of silence. Indeed, Webern’s treatment of the rest as a constructive rather than rhetorical device (cf. Reference LoLo 2015; Reference SyroyidSyroyid 2020) was considered such a defining feature of the late works that, in his lectures on ‘Twentieth-Century Tendencies in Music’, held at Columbia University from July to August 1948, Edgard Varèse heralded Webern as ‘the poet of the pianissimo, of mystery and silence’ (typescript, Edgard Varèse Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation). In fact this trope was so pervasive that only seven years later Reference EimertEimert (1955: 36) was able to call it a ‘cliché [Klischeebild]’.

A representative example of the idiolect that has sparked this mode of reception is Webern’s final variation (coda) from the second movement of the Symphony (Figure 6.5a). Built on the basic row and its retrograde, this passage largely comprises individual dyads, melodic fragments, and, indeed, a striking number of rests which are directly tied to the harmonic-formal organisation. Three out of the eleven bars in fact have full bar rests, and the use of compound crotchet rests adds to the scene two more ‘silences’ of roughly the same length. (The sense of ‘symmetrical’ lengths is obfuscated by the change of tempo.) The setting of the row running simultaneously ‘forwards’ and ‘backwards’ corresponds with the symmetrical rhythmic-formal disposition: as shown in Figure 6.5b, the passage is mirrored in b. 94. Fed into such a constructive metabolism, these crotchet and full bar rests can be considered to mark a negative presence. It is in this precise sense that in Webern the ‘silence’, structurally determined, enters the status of ‘material’, and thus is materialised.

Figures 6.5a and b Webern, Symphony, op. 21/ii, final variation (reduction), accompanied by some analytical annotations

Given the tight relationship between rests and harmonic organisation, it is not hard to see why this type of musical thinking was regarded as a precursor to what Reference StockhausenKarlheinz Stockhausen (1959: 12) came to identify as the cornerstone of post-war serialism: the ‘attempt to put the time-proportions of the elements in order, by means of a series’. Any such ‘proto-serial’ interpretation of Webern is not uncontroversial, however. As can be glimpsed in Peter Stadlen’s first-hand account, Webern considered the Symphony by no means a caesura in his development but rather a natural continuation of the expressive idiom that he had cultivated in his previous works. Going into detail about Webern’s disappointment when a performance of the Symphony in Vienna (to which Stadlen had accompanied him) reduced the work to no more than ‘seemingly unconnected little shrieks and moans’, Stadlen reports that the dissatisfied composer, by that time himself a much-celebrated conductor, demonstrated to him how the music was initially conceived – namely, essentially, as a rich discourse of expressive gestures. Stadlen takes this discrepancy as the starting point for a razor-sharp reflection. Relating the difficulties in communicating to the musicians the plasticity of embodiment Webern was apparently hoping to obtain to issues of ‘metrical complexity’, he wrote: ‘not too many things going on at the same time, but too few things at the required time … and so we are robbed of one of the basic prerequisites of all musical understanding: our ability to feel the regular beat of the metre and to relate to it the rhythms we listen to’ (Reference StadlenStadlen 1958: 10–6). Indeed, as Reference BaileyKathryn Bailey (1995) has shown based on a philologically rigorous analysis of the sketches for the Symphony op. 21, the Piano Variations op. 27, and the String Quartet op. 28, there is good evidence that Webern treated rhythm and metre as two fairly independent parameters, to the extent that he, seemingly with ease, could change the metre of whole passages at various stages throughout the compositional process apparently without fearing that these surgeries might interfere with the rhythmic identity of the gestures he sought to express.

These insights, I wish to venture, can be interpreted as bringing yet another lyrical quality of Webern’s ‘silences’ to the fore, one that is less defined by virtue of their (material) ‘presence’ but rather the engendering of what could be termed (phenomenological) ‘presencing’. As suggested in Figure 6.5c, the ‘pulse’ of the Symphony’s final variation, though notated in

![]() , can no less (im)plausibly be heard in

, can no less (im)plausibly be heard in ![]() . This metrical vacillation causes a bewildering effect. While due to the symmetrical setting the final gesture F♮5–B♮2 falls, unlike in the corresponding b. 89, onto the second (weak) beat of the bar, if conceived in triple metre this gesture falls yet again onto the first (strong) beat. In so doing, it insinuates a sense of continuation that never materialises. Couched in Edmund Husserl’s terminology, the consecutive triple-metre pulse can thus be understood as instantiating a trace of ‘retentive memory’ through which, virtually, the final gesture – ‘protentively’ – travels beyond the final bar line. In this sense, the final gesture is at once ‘closing’ the work and staring into the ‘openness’, freezing in this climate of structural ambivalence to a ‘tone-now [Tonjetzt]’ (Reference Husserl and HeideggerHusserl 1964: §§11, 38, and 39) that, ecstatically, seemingly stands outside of time.

. This metrical vacillation causes a bewildering effect. While due to the symmetrical setting the final gesture F♮5–B♮2 falls, unlike in the corresponding b. 89, onto the second (weak) beat of the bar, if conceived in triple metre this gesture falls yet again onto the first (strong) beat. In so doing, it insinuates a sense of continuation that never materialises. Couched in Edmund Husserl’s terminology, the consecutive triple-metre pulse can thus be understood as instantiating a trace of ‘retentive memory’ through which, virtually, the final gesture – ‘protentively’ – travels beyond the final bar line. In this sense, the final gesture is at once ‘closing’ the work and staring into the ‘openness’, freezing in this climate of structural ambivalence to a ‘tone-now [Tonjetzt]’ (Reference Husserl and HeideggerHusserl 1964: §§11, 38, and 39) that, ecstatically, seemingly stands outside of time.

Lyricism as Politics

As deeply fascinating as Webern’s lyrical imagination is on some level, it undeniably also comprises a troubling political dimension. This is perhaps nowhere else more poignantly encapsulated than in his admiration for the poetry of Stefan George. Webern had set several of George’s poems to music around 1907 to 1909, the famous years in which he had embarked upon his self-proclaimed ‘path’ to atonality, and published many of them between 1919 and 1923 as opp. 2–4. Later in his life, Webern seems to have seen his interest in George’s poetry vindicated, through disturbing signs. As Hans and Rosaleen Reference MoldenhauerMoldenhauer (1978: 526–32) were able to reconstruct, in a letter to his friend Josef Hüber in December 1940 Webern heralded George’s poem collections The Star of the Covenant and The New Reich as prophecies of a new social world order that he saw now – at a time the Wehrmacht had invaded Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, and Mussolini’s Italy had occupied parts of north Africa – become reality. And still two years later – following the Wehrmacht’s first setbacks – he evidently turned to George’s poetry as a source for optimism (see also Reference BaileyBailey 1998: ch. 8, esp. 172–3). To be sure, the sources known today indicate that Webern’s views of National Socialism may have been more ambiguous than an isolated reading of his correspondence with Hüber suggests (see Reference KronesKrones 1999). But these biographical documents do raise some far-reaching questions. While Webern’s interest in poetry itself may not have instigated his enthusiasm for the war, it stands to reason that he, personally prone to succumbing to authorities and consistently in pursuit of securities and stabilities in his private life, found in the new-symbolist tropes he felt so drawn to throughout his lifetime a resonance chamber for a type of identity-thinking that retrospectively tallied all too well with Nazi ideology. This renders Webern’s musical lyricism, as little as it seems to have in common with Nazi cultural politics at first glance, politically septic.

The question however of how, if at all, this ideological dimension is manifest in the fibre of Webern’s compositional thinking taps into some formidable methodological challenges. For Reference TaruskinRichard Taruskin (2009: 397; see also Reference Taruskin2005a: 734–41), the case is surprisingly clear. With reference to the heaped occurrences of the B-A-C-H cipher through the technically ‘dehumanised’ String Quartet op. 28, he paints a picture of Webern (alongside Schoenberg) as a relentless ‘chauvinist’ for whom ‘Bach was a third Bach, a national as well as a universal figurehead … [whose] elaboration of the technique of absolute music … vouchsafed German domination’. And he proceeds to cock a snook at Carl Dahlhaus as the key post-Adornian advocate for the concept of aesthetic autonomy, contending with heretic joy that not even Webern’s ‘absolute’ music is unencumbered from ideology.

Once read as calling out large strands of Webern reception for depoliticising the composer, Taruskin’s biting polemical attack, while valuable, arguably throws the baby out with the bathwater. By stripping the concept of aesthetic autonomy from the heuristic potential it holds for understanding the relationship between music and politics, Taruskin’s account may be considered somewhat myopic. As Reference JohnsonJulian Johnson (1999: 223) has argued, ‘art does not offer a critique of society by having nothing to do with it, but by reordering and reformulating social categories in aesthetic form’. With Johnson’s caveat in mind, identifying musical ciphers as if they were traffic signs is in effect to retreat to an essentialist position, one that arguably all too quickly runs aground at the question of how these meanings are negotiated in the individual work. Indeed, as Reference Ahrend, Heister and SparrerThomas Ahrend (2018: 32) has suggested, the musical structures to which Webern’s particular ‘psycho-social disposition’ gave rise are best understood as fulfilling an aesthetic rather than a personal function, and thus ‘dynamised’ in the individual work they may as a matter of fact ‘undermine [their initial status as] merely preconceived representations of order’.

The irony is that Taruskin, if he had been willing to pursue a perspective drawing on aesthetic autonomy, could have found in his arch-enemy Adorno a well-disposed interlocutor. Adorno remained wary of certain aspects of Webern’s aesthetics throughout his lifetime. In particular, in his post-war writings on the composer it becomes palpable how he recoiled from Webern’s late works. ‘The fear that the act of composition might damage the notes leads to a vanishment [of subjectivity] … hardly anything happens anymore; intentions [in the music] scarcely make any impression, and instead he [Webern] sits in front of his notes and their basic relationships with his hands folded as if in prayer’. In my reading, the issue for Adorno was thus not simply that in Webern the rational patina of the twelve-tone method had hardened into the dogma of orders (Gesetze) but, more specifically, that the ‘rich interplay’ facilitated through this hardening produced no musical moments of immanent transcendence (Reference AdornoAdorno 1999b: 101–2, translation amended). What Adorno recognised was rather that the differential relations – Reference WhittallArnold Whittall (1987) felicitously speaks of ‘multiple meanings’ – woven into Webern’s tightly controlled fabric annul any motions of even the slightest dialectical sparkle, into a state of ‘oscillations’ (see Reference Ahrend, Heister and SparrerAhrend 2018: 32). To overstate the issue slightly: in his search for ‘Hegel’ in a desperate attempt to save the dialectic in Webern, Adorno only found that the composer had turned the quasi-Heideggerian vice of tautological ontology into a virtue. Adorno, the Hegelian, captured this critical twist in his own appropriately dialectical terms, as follows: ‘In Hegel’s Phenomenology we encounter at one point the disconcerting phrase “fury of disappearance”: Webern’s work converted this into his angel’ (Reference AdornoAdorno 1999b: 94). Put differently, what made Webern’s ‘absolute lyricism’ so ‘tragic’ for Adorno is that it remains precisely underdetermined as to whether it obsecrates unity (‘variations of the same’) or difference (‘variations of the same’).

There is a remarkable moment in the third movement of the First Cantata op. 29 that allows some deep glimpses into what, in a post-Adornian vein, I like to think of as Webern’s musical obsecration (Figure 6.6). Entrenched in the theosophical discourses of its time (see Reference AbbateAbbate 2018), the text that Webern chose to set – an extract from a (lost) poem entitled ‘Transfiguration of the Charites [Verwandlung der Chariten]’ which Jone had sent to him in early 1939 – casts Apollo’s music for the Gods in the light of solemn metamorphosis. According to Jone’s own interpretation (Reference Jone1959: 7), the ‘Verwandlung’ mentioned in the title rests essentially on three steps: firstly, the text associates Apollo’s music-making with ‘inexpressibly melancholy’, the ‘deities’ of which are then ‘silenced’ and ‘absorbed in … eternal meaning’, before eventually an ‘amazing transformation takes place’ that amounts to a revelation of ‘joyful astonishment’. The final lines read: ‘Charis, the gift of the highest: the grace of mercy glistens! / bestows herself in the darkness of the developing heart as dew of perfection [Vollendung]’. The way Webern musically renders the ‘silencing’ of the ‘deities of melancholy’ is aesthetically insightful. Following a transition played in the strings and harp that unmistakably represents Apollo’s ‘blessed strings’ (bb. 34–8), to the words ‘all the former names have faded away in sounds’ the music eventually bursts out quietly into a fully fledged arrangement, with four different rows running in parallel (using notably all four row types on the same transposition step), played in stretto, and which ‘liquidises’ the two subjects staged in the opening through tightly knit fugal-variational processes (bb. 39–43) (see Reference BaileyBailey 1991: 292–302, 342, 396–7). It is as if Apollo’s ‘sound’ has collapsed onto itself, and we now, in piano, begin to vaguely gain a sense of the ‘former names’ reverberating before they ‘fade away’ into oblivion. This compositional realisation, it strikes me, epitomises the aesthetic model of Webern’s musical obsecration. By literally sounding out the structural-semantic depths of Apollo’s ‘sound’, this passage, highly differentiated, asserts only itself, rendering the notions of transcendence and presence in terms of an ontological double-bind.

Figure 6.6 Webern, Cantata No. 1, op. 29/iii, bb. 34–43 (reduction)

How can this passage be understood in political terms? Webern turned to the composition of the Cantata four months after the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany and apparently found in this text the appropriate missing piece to bring this work to completion. In her contribution to the special Webern issue of Die Reihe, published ten years after the end of the Second World War, Jone invited a reading of the Cantata essentially as an anti-war piece of music, as a piece of consolation and comfort composed during the darkest of times. Recalling how she had heard the Cantata for the first time in August 1940, in the company of Webern and his student Ludwig Zenk, she wrote (not timid about speaking for all three of them): ‘the music, heard by us here in the neighbourhood of the bells, is no other than the sparkle of the grace of Grace, in the midst of the war. We cannot forget the war while listening to the music, but we are given something to take back into the dark with us and to give us light’ (Reference JoneJone 1959: 7). This account seems difficult to square with all the evidence known to us today about the war enthusiasm Webern (and Zenk) harboured at that time (see Reference HommesHommes 2010). Without meaning to perpetuate superfluous speculations over Webern’s intentions, one may wonder whether it is not also conceivable that Webern construed the text in a nationalistic-heroic light and specifically perceived in the ‘former names’ reverberating through Apollo’s ‘melancholic’ sound those not-yet-realised forces that he also perceived in George’s poetic vision. But if that was the case, the redemptive power of transcendence Jone claimed to be inscribed into Webern’s setting would stand revealed as the ultimate terror of presence. Was Webern’s other-worldly lyricism – according to Reference EimertEimert (1959: 32), ‘an outsider’s world in the extremest sense’ – perhaps all too painfully worldly after all?