Background

High-stakes treatment decisions are frequently made in the Emergency Department (ED), highlighting the importance of introducing goals of care conversations into the emergency visit (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Newman and Lasher2013; Grudzen et al., Reference Grudzen, Richardson and Johnson2016). Yet, such conversations often do not occur in EDs (DeVader et al., Reference DeVader, Albrecht and Reiter2011; Lamba et al., Reference Lamba, DeSandre and Todd2014). There is a critical need to improve the frequency of these conversations, so that ED providers can align treatment plans with patients’ goals, values, and priorities.

To provide language for clinicians to ask patients about these domains, Ariadne Labs created the Serious Illness Conversation Guide (Ariadne Labs: Serious Illness Program, 2019). Programs leveraging the Serious Illness Conversation Guide in other care settings have demonstrated improved frequency, quality, and timing of conversations, but the Guide has not been studied in the ED setting (Bernacki et al., Reference Bernacki, Paladino and Neville2019; Paladino et al., Reference Paladino, Bernacki and Neville2019).

The profession of social work, which has long been integrated into hospital and home-based palliative care, employs a holistic approach to patient care that positions social workers to be successful in assessing the complex landscape of patients’ individual, family, and sociocultural needs (Cicely Saunders, Reference Cicely Saunders2001; Bosma et al., Reference Bosma, Johnston and Cadell2010). No published program to date, however, has leveraged ED social workers for Serious Illness Conversations in the ED.

The original Serious Illness Conversation Guide was designed for use upstream for advance care planning, when patients are feeling well, and was not initially intended for use when patients are acutely ill, as in the ED. It is, however, open-source and intended for adaptation as has been the case in other care settings (Bernacki et al., Reference Bernacki, Paladino and Lamas2015b, Reference Bernacki, Paladino and Neville2019; Cauley et al., Reference Cauley, Block and Koritsanszky2016; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Koritsanszky and Cauley2016; Lakin et al., Reference Lakin, Block and Andrew Billings2016, Reference Lakin, Koritsanszky and Cunningham2017; Lamas et al., Reference Lamas, Owens and Nace2017a, Reference Lamas, Owens and Nace2017b; Mandel et al., Reference Mandel, Bernacki and Block2017; Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Greenwald and Caponi2017; Gace et al., Reference Gace, Sommer and Daubman2020).

Understanding the unique ED environment, and the distinct skills that ED social workers bring to these conversations, we set out to adapt the Serious Illness Conversation Guide for use in the ED by social workers.

Methods

We undertook a four-phase process for the adaptation of the Serious Illness Conversation Guide for use in the ED by social workers.

In the first phase, our institution's existing Guide, which had been modified from Ariadne Lab's original open-source Guide and was intended for use in the primary care setting (Figure 1), was tested by three ED social workers in a simulated conversation. The simulated conversation was observed by two palliative care social workers: an emergency physician with focused palliative care training and an internist who leads the local efforts related to generalist palliative care communication training. It was followed by a facilitated discussion about the experience of using the Guide, the unique practice environment of the ED, and the skill sets of the social workers as it related to the Guide's use.

Fig. 1. Original Serious Illness Conversation Guide.

In the second phase, specific adaptations of the Guide were collected from all present at the simulation and iterated on until a draft was established. The draft was then reviewed by a palliative care physician, and a second round of revisions was undertaken by the entire study team.

In the third phase, the adapted Guide was pilot tested. This was first done by the three ED social workers in a second simulated conversation. Real-time changes to the Guide were made. This was followed by a third and fourth simulated conversation with two of the ED social workers and a patient representative.

Lastly, the guide was deployed in the ED and tested with 10 ED patients over four weeks. Each week the study group met to debrief on the Guide's use and the social worker's experience with facilitating these discussions in the ED. This resulted in additional changes being made to the Guide.

This study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board.

Results

During each phase of the Guide's adaptation, changes were made to reflect both the environment of care (ED) and the clinicians (social workers) that would be using the guide.

Phase 1

The results of the simulation exercise leveraging the existing guide resulted in robust discussion around the following themes: (1) framing the conversation to take into account the acute uncertainty of the emergency visit; (2) more social work role — appropriate language related to assessing prognostic awareness and sharing worries; and (3) the need to create language that would equip social workers to navigate conversations related to resuscitation preferences (code status) which they have not traditionally been involved in.

Phase 2

In this phase, discussion focused on:

(1) The creation of a standardized introduction for social workers, including adaptations contextualizing the social worker's role and framing the conversation (changing the language from asking permission to “talk about what is ahead in your illness” to instead “Can we take a step back and take a look at the bigger picture?”).

(2) Cognizant of the diagnostic uncertainty that is often introduced by the emergency visit and the scope of practice of the social workers, changes were made to the section which had been designed to help clinicians’ share medical concerns with patients. Instead of prompting the social worker to share a specific worry about the patient's future clinical trajectory, this section was adapted to instead explore and reflect the patient's worries.

(3) In the section that had been designed to help clinicians explore what is important to patients, a series of example phrases were modified to help facilitate the exploration of values that might inform resuscitation preferences. Specifically, new language was added to respond to patients that expressed interest in avoiding intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Phase 3

Active testing of the Guide in Phase 3 with a patient representative led to substantive changes related to how the social workers assessed the patient's illness understanding and address resuscitation.

The illness understanding question (“What is your understanding of your illness?”) was modified to contain two parts. The first part probes the patient's understanding prior to the acute visit (“What's your understanding of your health?”). The use of the word “health” rather than “illness” was intended to prompt the patient to discuss how they were prior to the ED visit. The word “health” was also noted to be more holistic, positive, and better aligned with the social work role. The second part probes the patient's understanding of the acute situation (“What's your understanding of what's going on right now?”) The two-part approach helps the patient more clearly articulate their baseline health in addition to changes which may have precipitated the ED visit.

The role of the social worker related to resuscitation preferences was also further clarified during this phase of development. It was decided that the social worker role had two parts: (1) to understand and document patients’ goals and values that might inform later medical decision-making and (2) to identify patients who have had a conversation about CPR and have established preferences. Learning about previous CPR conversations and established preferences was distinguished from having a conversation about future preferences for CPR, which was identified as beyond the role of the ED social worker.

Phase 4

Initial piloting of the Guide with patients in the ED during Phase 4 resulted in two final changes to the Guide. The first was in response to a recognition that in the ED, patients were acutely focused on the medical presentation that brought them to the hospital. As a result, social workers reported a narrow focus to the question “what's your understanding of your health,” and an inability to elicit a broader response about patients’ perception of their overall health. This acute focus was also true for the question about hopes. To shift the focus of the conversation beyond the acute setting, the illness understanding language was changed to “what's your understanding of your health generally.” Similarly, the hopes question was prefaced with “Beyond what's happening today, … ”.

Lastly, it was noted that some patients struggled to understand the questions related to hopes and worries. In speaking with practitioners using the guide in other settings, it became clear that examples could help to cue the discussion. The result was the insertion of prompts to help the social workers provide examples to patients if they did not offer hopes or worries when initially asked.

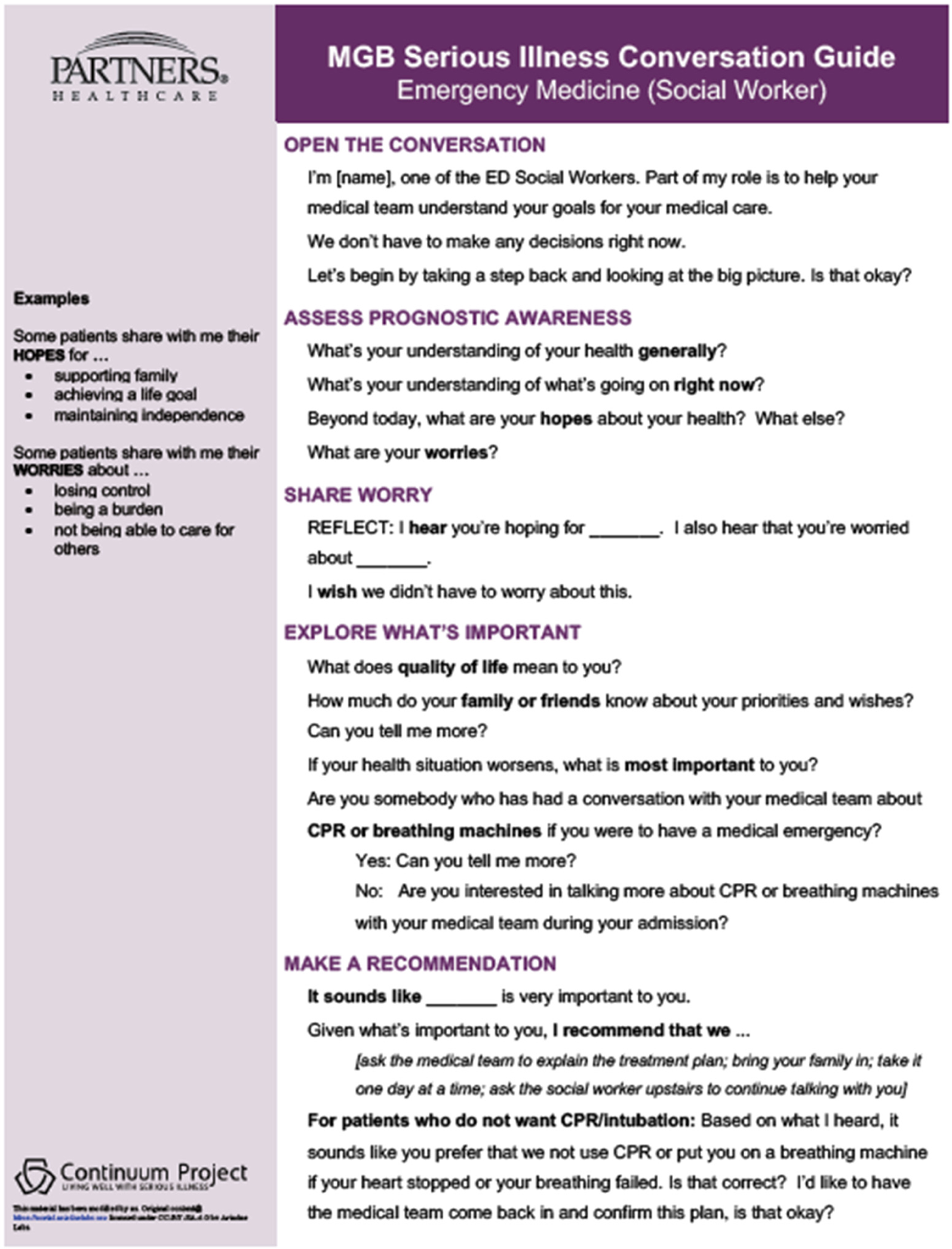

The finalized guide appears in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Adapted serious illness conversation guide for use by social workers in the emergency department.

Discussion

In this focused effort to adapt the Serious Illness Conversation Guide, we undertook a structured four-phase approach to adapting a tool that has been widely used to guide conversations about goals and values in primary care (Lakin et al., Reference Lakin, Block and Andrew Billings2016, Reference Lakin, Koritsanszky and Cunningham2017), inpatient general medicine (Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Greenwald and Caponi2017; Gace et al., Reference Gace, Sommer and Daubman2020), emergency surgery (Cauley et al., Reference Cauley, Block and Koritsanszky2016; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Koritsanszky and Cauley2016), inpatient and outpatient oncology (Bernacki et al., Reference Bernacki, Paladino and Lamas2015b, Reference Bernacki, Paladino and Neville2019), long-term acute care (Lamas et al., Reference Lamas, Owens and Nace2017a, Reference Lamas, Owens and Nace2017b), and in patients with renal failure (Mandel et al., Reference Mandel, Bernacki and Block2017).

The content of our adapted Guide is meant to reflect the unique practice environment of the ED and advanced communication skill set that social workers bring to this work. Specifically, the adapted Guide focuses on eliciting hopes and worries, moves away from a focus on discussing prognosis, and ensures that, for patients who have specific preferences regarding their care, including life-sustaining treatments, that these are captured.

The original Guide was developed through a comprehensive convening at Ariadne Labs (Bernacki and Block, Reference Bernacki and Block2014; Bernacki et al., Reference Bernacki, Hutchings and Vick2015a). As such in approaching our work, rather than spending significant time convening experts to adapt the Guide through review and discussion, we instead chose to begin with a simulation exercise involving the existing Guide. This experience yielded important insights about the challenges inherent in the Guide and framed the discussion of the unique considerations related to needed adaptations for use in the ED and by social workers. Furthermore, although the structured review of the Guide that followed and iterative rounds of review in Phase 2 yielded important insights, it was not until we pilot tested the adapted guide with a patient representative and then ED patients that the most substantive changes were made. This insight into the role of formally building simulation and testing early into the adaptation process is important.

Although, at the outset of this work, we had laid out general goals for the adapted Guide, it was not until the third phase of the Guide's adaptation that we revisited these goals and made them more explicit. This process of clearly articulating both what the goal was (to better understand and document patients’ goals and values and to identify patients who have already had a code status conversation) and what it was not (being used to share prognostic information or make recommendations) was crystalized through the simulation with a patient advocate. This insight into the role of the patient perspective is also important.

Ultimately, the content of the modified Guide differs in some overt (removing prognostic disclosure, explicitly asking about previous CPR conversations) and some subtle (frame shifting from a discussion of illness to a discussion of health) ways from the original Guide. These changes allow the Guide to more accurately respond to the acute uncertainty created by an emergency visit and to the clinical practice of ED social workers.

We recognize several limitations in our work. First, we restricted the scope of this study. We set out to adapt the Serious Illness Conversation Guide, but not to test its feasibility or acceptability in the ED environment. As such, although we have a prototype we do not have insight yet into its ability to be successfully deployed. The group that gave input, although representing all stakeholders, was small and largely made up of clinicians with a deep commitment to this work. The three ED social workers engaged in the study, although with no formal background in palliative care, volunteered to participate and, as such, may not be a representative sample of ED social workers. The same is true of the ED, internal medicine, and palliative care physicians involved.

Significance of the work

This brief report presents an adapted Serious Illness Conversation Guide for use in the ED by social workers. This Guide may provide a tool that can be used to increase the frequency and quality of serious illness conversations in the ED. Future work will need to focus on field testing the guide and should focus both on the feasibility of having these discussions in the ED environment, by ED social workers, the acceptability to both patients and the clinicians having the discussions, and, ultimately, the impact of these discussions on patient care.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.