The attorney prodded the witness with questions. Repeatedly, he pressed the corporate official from the Tin Processing Company to explain how employees at the firm’s plant in Texas City, Texas were segregated. That the production areas were integrated went without saying, so the lawyer inquired instead about virtually every other physical space in the plant, including the cafeteria, first-aid room, parking lot, time-clock room, and the bathhouse. He wanted to know whether all of the firm’s workers had equal access to these spaces or whether, instead, some used separate facilities. In response, the official insisted that no provisions were made for segregating any of the plant’s seven-hundred-odd employees.Footnote 1

This exchange unfolded at a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) hearing in 1951. Throughout it, neither the attorney nor the witness mentioned race. Rather than racial segregation, they were discussing workplace divisions that split the workforce at Tin Processing Company along another dimension: skilled workers versus their unskilled and semiskilled coworkers. The skilled craftsmen at the plant were fed up with the Oil Workers International Union (OWIU), an industrial union affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). As a result, they wanted to leave the OWIU and form their own separate bargaining units. Those new, much smaller bargaining units would be a part of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) craft unions, which historically represented skilled craftsmen, such as the Carpenters and Boilermakers. The key issue was wages. Like thousands of other similarly situated workers across the country, the craftsmen at Tin Processing sought an end to the steady decline in the wage premium they had historically enjoyed over their less skilled coworkers. In order to wrest control of the collective bargaining process from the OWIU, and in the process regain control of their wage demands, they sought what midcentury observers of the nation’s wage structure—from labor lawyers to labor economists, from rank-and-file union members to the editorial board of the New York Times—referred to as “craft severance.”Footnote 2

With his queries about segregation at the plant, the OWIU’s lawyer in Texas City was satirizing the craftsmen’s petition for craft severance. As a vehicle for his satire, he resorted to a reductio ad absurdum argument: if the skilled craftsmen at Tin Processing had interests so distinct from those of the other blue-collar workers in the plant—so distinct that they deserved separate union representation—did they not also deserve a separate place to park their cars, punch their time cards, eat their lunches, wash up after work, etc.? In a Texas courtroom in 1951, the message implied in invoking segregation was hard to miss: were the craftsmen so deluded as to suggest that the differences between them and their union brethren were akin to the differences between whites and African Americans? The lawyer’s absurdist rhetorical flourishes notwithstanding, the economic security of the plant’s unskilled and semiskilled workers was at stake. Harnessing the bargaining power of the plant’s skilled craftsmen was key to gaining leverage in contract negotiations with plant management. A favorable ruling on the craft severance petition would deprive the plant’s laborers and operatives of that leverage and without it, a decade of extraordinary wage gains might come to an end.

The craft severance movement is an unknown episode in U.S. history that nonetheless provides valuable insights into our current era of elephant charts and hockey-stick inequality graphs. The sharp reduction in occupational wage differentials during the 1940s from which those unskilled and semiskilled workers benefited, a phenomenon Claudia Goldin and Robert Margo termed the “Great Compression,” was nothing less than a watershed moment in American political and economic history.Footnote 3 By elevating the wages of tens of millions of Americans who did unskilled and semiskilled work, the Great Compression helped create some of the key features of Golden Age political economy, including an expanding middle class and robust economic growth based on stimulating mass purchasing power.

A quarter century after Goldin and Margo’s pathbreaking work, the Great Compression is the subject of renewed scholarly interest. The new studies that are emerging comprise one small part of a fast-expanding scholarly literature on economic inequality in the twentieth century, a field headlined by the scholarship of Thomas Piketty.Footnote 4 Using newly available, more detailed datasets, Taylor Jaworski and Gregory Niemesh replicated some of the research undertaken by Goldin and Margo. They confirmed one of the most important conclusions reached by Goldin and Margo: the 1940s were the key decade in terms of wage compression. The story of the 1950s was, in fact, the widening, not narrowing, of wage differentials.Footnote 5

What caused the Great Compression? There are few more politically potent questions one could raise about modern U.S. history. For decades, the most widely-accepted explanation has been that the origins of the flatter income distribution lie partially in National War Labor Board wage controls.Footnote 6 More significant, in the postwar period, compression was sustained by the rising number of high school and college graduates, an increase that drove down the income premium those workers had historically enjoyed.Footnote 7 In this account, policies explicitly intended to raise the wages of the country’s least paid workers, including state-supported collective bargaining, had a marginal impact, especially after 1945. The latest scholarship on the Great Compression advances new interpretations of its causes. In contrast to the earlier emphasis on fluctuations in the supply of educated workers, the most recent research points toward an alternative, institutionalist account of the Great Compression. Using new data sources on union membership for the midcentury period, including better direct measurements as well as proxies for union density, three recent studies buttress the institutionalist account.Footnote 8 Together they make a compelling case that the gains of the least-paid workers during the Great Compression can be attributed to the effects of collective bargaining.

This article builds on the institutionalist interpretation by making the case that the bargaining-unit policies pursued by the National Labor Relations Board, the kind in contention at Tin Processing, also help explain both the beginning and the end of the Great Compression. The evidence used is qualitative; no precise statistical correlation between NLRB bargaining-unit policy and changes in the nation’s wage structure is offered. Instead, the case made is largely circumstantial: the wage structure and bargaining-unit policy shifted relative to each other just as one would expect them to if they were causally connected. In the era when the NLRB strongly favored industrial bargaining units, wage compression happened fastest; when, in the late 1940s, the NLRB changed course and began to grant more craft severance petitions, wage compression eventually slowed; by the mid-1950s, as board policy stabilized somewhere in between the craft and industrial unions’ preferred policy, the nation’s wage structure also found its own angle of repose. Moreover, the behavior of the union members and policymakers involved suggests that their actions were, in fact, motivated by a desire to change the wage structure. In other words, in ways we have not recognized, the Great Compression was not an accident.

The skilled craftsmen at Tin Processing certainly did not think it was an accident. In part, they blamed CIO unions like the OWIU. But they understood that industrial unions’ wage program was made possible by New Deal labor policy and they understood that the mechanism for carrying out that policy was NLRB bargaining-unit determinations. So craft unionists also directed their ire at the NLRB and, more specifically, at section 9(b) of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. That provision empowered the National Labor Relations Board to determine whether “the unit appropriate for the purposes of collective bargaining shall be the employer unit, craft unit, plant unit, or subdivision thereof.” By giving the NLRB the prerogative to decide the appropriate bargaining unit, the Wagner Act changed the basic relationship between the federal government and workers, but also between workers and their unions. Prior to 1935, craft unions effectively selected their members by declaring certain kinds of work and workers to be within the union’s exclusive jurisdiction. The Wagner Act inverted that relationship: unions were now agents of workers who selected the union of their choosing via election.Footnote 9 Crucially, whether the eligible voters in that election included every worker employed by a company, every worker in a plant, or just a couple craftsmen was up to the NLRB.

The board’s appropriate bargaining-unit policy, which at first glance appears to be a highly technical aspect of collective bargaining, in fact reflected what one labor relations expert called New Dealers’ “totally different conception of the wage contract.”Footnote 10 That new conception was based on using collective bargaining as a tool to increase workers’ income and therefore their buying power. And the appropriate bargaining-unit determinations were a crucial means of delivering that Keynesian stimulus. The premise behind that policy was simple: skilled workers had more power than their unskilled and semiskilled brethren. The scarcity of their skills, their greater ability to disrupt production by going on strike, and their vastly greater experience with collective bargaining—all of these factors meant that skilled workers’ inclusion in industrial unions would enhance those unions’ bargaining power. As a result, one of the crucial ways the NLRB supported industrial unionism, and thereby boosted the nation’s aggregate purchasing power, was by lumping in skilled workers in with unskilled and semiskilled workers, thereby using the greater bargaining power of the skilled workers like a fulcrum to raise the wages of all industrial workers. The NLRB’s early bias toward industrial bargaining units worked exactly as the Wagner Act’s architects intended: unskilled and semiskilled production took advantage of both their own greater voting strength within the union and the skilled workers’ greater leverage vis-à-vis their employers to vote themselves bigger pay increases than the raises granted to skilled craftsmen.

By revealing the connections between New Deal labor policy and the nation’s wage structure, the craft severance movement enhances our comprehension of the New Deal order. The concept of a New Deal order has had a strange career of late, appearing more tenuous and evanescent even as its accomplishments seem more remarkable and substantial. In describing the state of the field, Meg Jacobs has written that “in some ways, the New Deal state was more expansive and enduring, yet in others it became subject to challenge much earlier than previous scholars realized.”Footnote 11 The craft severance movement corroborates this interpretive shift. When Congress passed the Wagner Act and FDR signed the legislation into law, they made an even more ambitious departure from existing federal policy regarding collective bargaining than scholars have recognized. Not only did they offer unprecedented federal support for workers’ collective bargaining rights, they effectively made collective bargaining policy an adjunct of wage policy. Conferring on the NLRB the power to designate the appropriate bargaining unit, and therefore to provide much-needed support to industrial unions in their battles against existing craft unions, was the vital institutional innovation that linked collective bargaining policy and wage policy. In the “us versus them” paradigm of collective bargaining, Congress in essence empowered the NLRB to define “us.” This was New Deal experimentation at its boldest and most provocative.

This feature of New Deal wage policy elicited a backlash, not just in Texas City, but all over the country. As economist John Winfrey observed more than half a century ago, “It takes little imagination” to understand why craft workers grew tired of seeing their bargaining power used to create leverage for other workers’ wage increases.Footnote 12 This article documents that backlash as it unfolded in two places from 1935 to 1955: first, in Washington, where New Deal Democrats, reactionary southern Democrats and their Republican allies, and union leaders and NLRB staff members fought to determine the board’s appropriate bargaining-unit policy; second, in a major manufacturing center, the petrochemical and metalworking industrial complex that was centered on Houston and stretched south to Galveston and east along the Gulf Coast to Port Arthur, where workers both took an active part in shaping NLRB policy and made the most of existing board policy. In doing so, it delves into aspects of New Deal labor policy that have largely escaped the attention of scholars for half a century. In a narrow sense, what emerges is an up-close examination of midcentury collective bargaining practices.

More broadly and more significant, the story of the craft severance movement provides a window into the social conflict that accompanied the deep and thorough politicization of the nation’s wage structure that began in 1933. Indeed, while the outcome of the thousands of appropriate bargaining-unit hearings held by the NLRB would turn on narrow, technical questions of administrative law, each hearing also posed an urgent political question: Was the base of political support for New Deal labor policy, especially support for industrial unions, broad enough to sustain it? This question was especially urgent during the 1940s as the New Deal’s “radical moment” came to an end and FDR and the Democratic Party shifted their attention from economic reform to wartime mobilization?Footnote 13 On the answers to this question hinged the future of NLRB support for industrial unionism and the experiment in federal wage policy that it represented. In courtrooms all over the country, from the Wagner Act’s passage in 1935 until the AFL-CIO merger in 1955, the fate of that experiment was determined one NLRB craft severance hearing at a time.Footnote 14

The craft severance movement emerged because the 1940s were a singularly bad decade for the nation’s skilled craftsmen. Like scheduled depreciation on a piece of capital equipment, the human capital of skilled industrial workers steadily lost value in the 1940s. The craft severance movement demonstrates that many skilled workers believed that depreciation was politically imposed, and therefore politically reversible. The National War Labor Board, while it was operative from 1941 to 1947, sometimes took an egalitarian approach to setting wages. Its influence abated, however, after 1945 and then ended altogether with the closure of its successor agency in 1947. Wage compression, however, continued even after the NWLB had been mothballed.

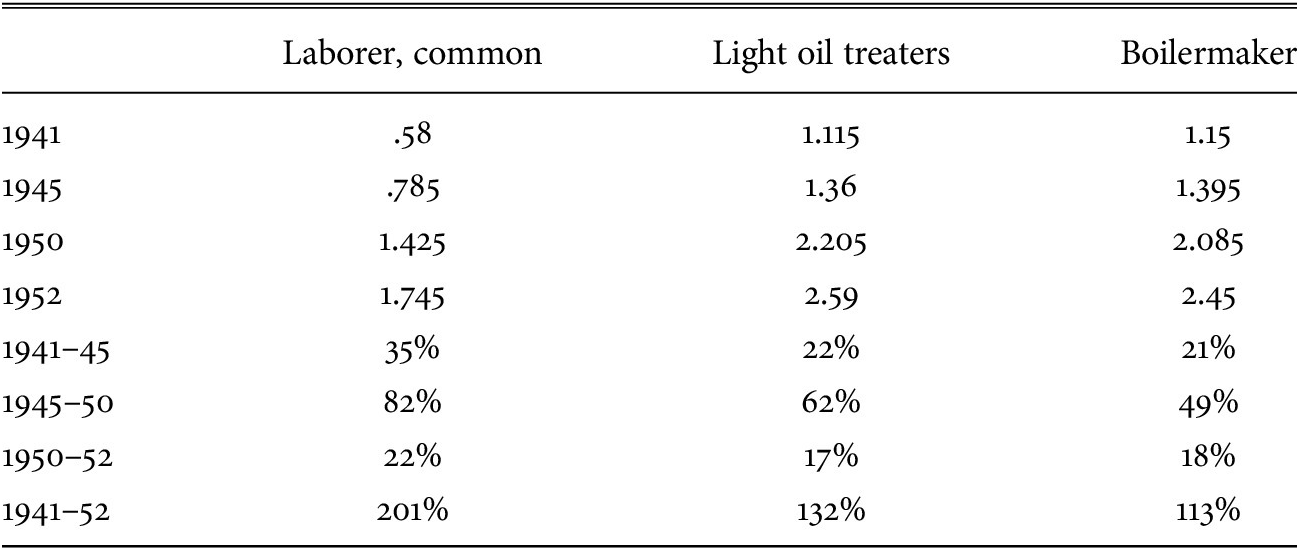

It happened, in fact, at an especially fast pace from 1945 to 1949.Footnote 15 There was variation from industry to industry, but the overall pattern was clear.Footnote 16 From 1929 to 1949, in nine basic industries, eight saw significant wage compression; the exception, the construction industry, was organized almost exclusively by craft unions.Footnote 17 From the 1930s into the postwar era, unions consistently negotiated wage increases in absolute rather than percentage terms. These across-the-board wage increases, in which all members of a bargaining unit received the same cents-per-hour increase, meant that unskilled and semiskilled workers gained ground steadily on skilled workers. In one city, unskilled workers went from earning 48.3 percent as much as skilled workers in 1940 to 60.9 percent in 1948.Footnote 18 The wage increases negotiated at the Sinclair refinery in Houston are also illustrative of national patterns. In the 1940s, craftsmen’s wages increased more slowly than semiskilled production workers and much more slowly than unskilled laborers. After 1950, the pattern changed markedly. Wage gains for all occupational groups were clumped together at around 20 percent (Table 1).

Table 1. Base wages of hourly workers at the Sinclair refinery in Houston

Source: Paper, Allied-Industrial, Chemical and Energy Workers International Union Collection, Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

Resistance to wage compression unfolded at two levels: at the policymaking level, especially in Washington, where NLRB doctrine evolved, and at the grassroots level, in the nation’s industrial workplaces, union halls, and labor lawyers’ offices, where union members drafted their NLRB petitions and fought among themselves for control of collective bargaining policy. The constant struggle to redefine bargaining-unit boundaries reflected the promise and perils of industrial unionism under the Wagner Act: industrial bargaining units created by the NLRB were akin to political units, especially polities that redistribute the earnings of one social group for the benefit of needier citizens. But unlike a state, with more or less fixed boundaries, a bargaining unit was perpetually unstable. Like a political party gerrymandering district boundaries, or a corporation establishing an offshore entity in order to evade its home country’s tax collectors, unionized workers continually sought to redraw the boundaries around them.

Reimagining and contesting boundaries was what skilled workers did when they filed “craft severance” petitions with the NLRB. Quite often, the workers who sought severance were skilled maintenance workers in a large factory, such as electricians, boilermakers, bricklayers, machinists, and carpenters. Rather than being mixed in with unskilled and semiskilled production workers, the maintenance workers sought the right to join craft unions and bargain separately from laborers and factory operatives. At stake in these attempts by skilled workers to “sever” themselves from the body politic of their current trade union was nothing less than the economic security of millions of workers.

Squarely in the middle of these disputes, serving as judge and jury on these basic issues of distributive justice, stood the National Labor Relations Board. The disputes were in every obvious sense private: the contending unions were private organizations and the wage income at stake was paid by private firms to private citizens. However, because the Wagner Act empowered the NLRB to decide the complex and highly contentious question of which workers belonged together in a bargaining unit, the federal government was thoroughly intertwined in them. As a result, redrawing the boundaries of worker solidarity, as craft severance petitions asked the NLRB to do, was fundamentally an exercise of political power, in which workers harnessed the power of the federal government to achieve their own ends.

The NLRB grappled constantly with the question of defining the appropriate bargaining unit, just as the National Labor Board had before it.Footnote 19 Already beset by intense opposition to its very existence from employers, putting the NLRB in charge of determining the appropriate bargaining unit ensured that the board would also encounter opposition from craft unions. For the labor movement, divided starting in 1936 into the AFL and the CIO, appropriate bargaining-unit policy was arguably the most divisive issue. It was nothing less than an existential question for both the AFL and the CIO.Footnote 20 As a result, at times it was the most critical and contentious issue before the board, even more so than thwarting employers’ unfair labor practices. According to one scholar, of all the heated issues the NLRB faced, bargaining-unit policy was “the subject area most charged with political controversy.”Footnote 21

The board tilted toward the CIO and industrial units in its early years.Footnote 22 The most outspoken advocate of industrial unionism on the board, Edwin Smith, wrote that he believed that industrial bargaining units must win out over craft units “if labor is to receive the full benefits of collective bargaining which the Act has guaranteed it.” Smith made clear that wage policy was one of the principal reasons for his bias in favor of industrial bargaining units. “The craft organizations,” he explained to another board official, “will build themselves up on the basis of persuading the employees in the respective crafts that if they break away from the industrial union and set themselves up as separate crafts they can get better terms than the industrial unions had so far gotten them. This process, of course, would gradually and certainly destroy the industrial union. [Craftsmen] are therefore in a favorable position, by separate dealing to extract a higher wage. It is apparent that their unique economic power would make their adherence to the industrial union of greater assistance to all employees.”Footnote 23

For Smith and likeminded contemporaries, appropriate bargaining-unit policy was, first and foremost, wage policy. John Dunlop, a federal labor mediator during World War II and one of the preeminent postwar labor economists, shared Smith’s perspective. In 1944, he observed that “a small group of strategic workers… can obtain very much higher rates than they could with a larger unit covering the whole enterprise.… The larger the bargaining unit, the more relative rates are apt to depend on the internal politics of trade unions. The formulation of public policy on the bargaining unit can afford to pay much more attention to the impacts of the size of the unit on the level and structure of wages.”Footnote 24

The attempt of New Dealers to use collective bargaining to shape the wage structure was, as Smith and Dunlop recognized, bound to generate conflict. Skilled craftsmen might have most of the bargaining power vis-à-vis management, but they were often outnumbered in their union. The tensions this created were intrinsic to industrial unionism. As a result, an industrial bargaining unit’s voting majority, comprised of unskilled and semiskilled workers, could use the leverage held by a minority to win collective bargaining concessions for the majority. Moreover, they could accomplish this while shortchanging the skilled workers whose collective bargaining leverage helped make the gains possible in the first place.

To resolve these tensions, the NLRB had a wide array of options. At one extreme, it could reject all craft severance requests, thereby protecting industrial unions’ ability to win big wage increases for most of their members. At the other extreme, the board could grant severance to every group of craftsmen who sought it. The political struggle over which of these two paths, or one of the countless paths that lay between them, the NLRB should follow determined the course of the craft severance movement.

Over the course of its first several years, the NLRB lent considerable support to CIO unions. Compelling skilled workers to be part of industrial bargaining units, as the board did hundreds of times in its early years, was not just a major CIO victory and a fundamental departure from the pre–Wagner Act status quo: it validated the CIO’s entire organizational model. In the late 1930s, the board occasionally made modest concessions to AFL unions. In 1937, it allowed skilled craftsmen the option of forming separate bargaining units, though only in fairly limited circumstances.Footnote 25 CIO advocates like Edwin Smith lamented that the ruling came “at the expense of entirely disregarding the interests of the majority.” Footnote 26 AFL leaders, however, were not mollified by a change that fell far short of the craft severance policy they sought.

A board ruling in 1939 set off even more alarms among AFL leaders.Footnote 27 By making industrial bargaining units presumptively appropriate in those places where workers had already voted to establish them, the ruling threatened to freeze in place the board’s pro-CIO bias. The leadership of the AFL was furious, so much so that it withdrew support for the administration’s wage and hour legislation and opted not to endorse the New Deal at the federation’s convention in October 1939.Footnote 28

That was, in some respects, the high-water mark for NLRB support of the CIO. In 1940, the Smith Committee investigations put the board on its heels, ultimately leaving it in the words of its principal historian, “a conservative, insecure, politically sensitive agency preoccupied with its own survival.”Footnote 29 The AFL, with the help of the incipient Republican–southern Democrat conservative coalition, used them to attack NLRB favoritism toward the CIO.Footnote 30 The federation’s representatives repeatedly returned to the problem of industrial bargaining units in their testimony; AFL president William Green called it an issue of “of transcendent importance.” Indeed, in order to secure favorable modifications to the all-important bargaining unit policy, Green supported other statutory changes that he believed would be detrimental to organized labor. Over the course of the hearings, the AFL and its allies succeeded in making the appropriate bargaining-unit issue so politically sensitive that the NLRB’s attorney expressed a desire to be rid of it altogether, notwithstanding the loss of power and prestige that would mean for the board.Footnote 31

The AFL’s efforts were rewarded. The Senate passed legislation that effectively removed the board’s discretion in determining the appropriate bargaining unit and made its unit determinations reviewable in federal court; the House Labor committee supported a bill focused even more heavily on the bargaining-unit determination question. Although neither bill became law, the AFL had other tools available. They threatened congressional action to lower the board’s budget. Most important, the Smith Committee’s investigations left public esteem for the board much diminished and made retaining the existing board membership a political nonstarter for Roosevelt.Footnote 32 Roosevelt, acting on the long-standing wisdom that personnel is policy, obliged the AFL and set the stage for a policy reversal by appointing new board members the federation supported. One of the new members, William Leiserson, made clear both the far-reaching importance of the bargaining-unit question and his opposition to the NLRB’s historic bias in favor of the CIO: “If the Board presumes to say that one unit is superior to another [the NLRB] is in effect determining the structure and form of labor organization in the country.”Footnote 33

Beneficiaries of a tailwind generated by the Smith Committee hearings, disgruntled skilled craftsmen, conservative-minded NLRB members, and conservative congressmen became mutually indispensable partners in restoring the bargaining power of organized labor’s historic elite. At the grassroots, craftsmen filed petitions with a board that was slowly becoming more receptive to their perspective. Conservative congressmen, whether Republicans or southern Democrats like Howard Smith, served two vital functions. They lobbied the Roosevelt administration to appoint more conservative members to the board, and they kept pressure on the board with the constant threat of investigations and statutory change.

Over the next several years, their combined efforts slowly bore fruit. In three cases in 1942, the board retreated slightly from its pro-CIO stance, giving more latitude to craft severance petitions with each small step backwards.Footnote 34 Change came at a halting, erratic pace in part because after 1940, board doctrine in many areas, including bargaining-unit decisions, was unstable because the members of the board could not form a governing majority.Footnote 35 Nonetheless, through the end of the war and into the postwar era, the board gave encouragement to skilled workers seeking craft bargaining units. In the words of a former board chairman, during the years 1944 to 1947, “there was substantial reconsideration and modification of policy in regard to the severance of craft groups when they requested it.”Footnote 36 The U.S. Supreme Court fortified the NLRB’s doctrinal evolution by ruling that the board enjoyed a wide degree of latitude in defining the appropriate bargaining unit.Footnote 37 The most important casualty of the board’s ideological shift was the presumption that industrial units were appropriate once established, including in plants with a robust tradition of industrial unit bargaining.

If board members looked to the election returns for encouragement to undermine a cornerstone of New Deal labor policy, they found it. Just days after the GOP recaptured Congress in November 1946, the NLRB announced another shift toward the AFL’s position on craft severance. The pro-craft severance trend continued into early 1947 with more cases that favored the AFL. Neither the AFL nor GOP congressmen were appeased.Footnote 38 When Republicans set about remaking U.S. labor law to their liking in 1947, they targeted the industrial unions of the CIO that they rightly associated with the left wing of the Democratic Party and socially progressive policies like wage compression. House Republicans favored a craft severance policy that would have dramatically constricted the board’s discretion and compelled it to presume that a request for a craft unit election was valid. It was the Senate’s language on the appropriate bargaining-unit question that passed, however, which in the words of one senator “did water it down a bit.”Footnote 39 The resulting section 9 (b) (2) of the Taft-Hartley Act did not require the NLRB to create a craft unit whenever workers requested one. Instead, Congress stipulated that the board was not allowed to make a prior bargaining-unit determination the exclusive basis for denying a craft severance petition. Past rulings, in other words, could be pertinent but not controlling. While the board retained wide latitude in appropriate bargaining-unit cases, Congress had imposed a small but meaningful limitation.Footnote 40

The effects of every shift rightward in bargaining-unit policy mattered more and more each year. In the 1930s, the board was primarily a forum for adjudicating employer-worker conflicts. In its first five years, “C” cases, also known as unfair labor practice cases because they centered on employers’ violations of workers’ rights, accounted for the lion’s share of the agency’s case load, peaking at more than 80 percent in 1935–36. During the 1940s, the board shifted its attention to “R” cases, which entailed running representation elections, including elections to resolve AFL versus CIO bargaining-unit conflicts. As the board ruled on more bargaining-unit disputes each year, each doctrinal innovation ramified through a growing number of related cases. In 1941, for the first time, “R” cases accounted for most of its work. By 1945, the board heard more than three times as many “R” cases as “C” cases.Footnote 41

As the board decided a growing number of cases involving interunion disputes, AFL unions began winning more elections and getting the smaller bargaining units they favored. From 1940 to 1945, CIO unions won more elections than AFL unions did in every year except one; the CIO’s advantage was small but noteworthy, roughly 15 percent in a typical year. In 1946 and 1947, the federations essentially tied. By contrast, from 1948 to 1955, AFL unions won more elections every year than did CIO unions, often twice as many. Critically, as the two federations’ fortunes shifted, so did the size of the bargaining unit. From 1935 through 1943, the number of voters in NLRB elections averaged 334 as CIO unions consistently won much bigger bargaining units than their AFL adversaries, peaking at more than four times larger in 1940. In stark contrast, from 1944 through 1951, the era when the AFL began winning more elections, the average was 137 voters per election. Moreover, in 1943–44, when workers sought craft units, the board granted a craft-unit election in almost three out of four cases and AFL unions won roughly 80 percent of those elections. They often accomplished this despite the opposition of employers: in roughly 70 percent of the cases where they weighed in, employers favored an industrial unit.Footnote 42 Employers understood, and feared, the effects of craft severance on the wage structure. They even had a term for it: the “whipsaw” effect. Once management conceded a wage increase to one group of workers, another group would immediately push management to grant them similar concessions; this process could go on indefinitely as each wage increase fed demands for further increases. In a workplace with several bargaining units, the opportunities for “whipsawing” the wage structure multiplied.Footnote 43

In the postwar era, despite the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 and ongoing employer opposition, unions continued to win a large number of elections. From 1949 to 1953, unions won more board elections than they had in their best years during World War II. But as the dwindling size of the bargaining unit suggests, they were winning different kinds of elections. After the Taft-Hartley Act, fewer AFL v. CIO conflicts involved competing over the same, larger group of workers; instead, they increasingly involved AFL unions seeking to represent a different, smaller subset of workers than their CIO rivals. And when AFL unions requested the smaller craft unit, the resulting elections were more likely to result in union representation. AFL unions also became the aggressors: after Taft-Hartley, they were typically the party seeking to “raid” a CIO union, whereas previously CIO unions were more likely to be the petitioning party.Footnote 44

With a flood of craft severance petitions coming in, with both the Supreme Court and Congress giving them more doctrinal elbowroom, the NLRB set about formalizing the criteria by which it would assess the petitions. Officially, the members of the NLRB considered wage levels irrelevant to the question of craft severance. A petition would neither be accepted nor rejected on the basis of its hypothetical impact on the wage structure. Wage differentials, wage compression, wage premiums, wage policy—the board very seldom mentioned any of these terms in the orders they issued in response to craft severance petitions. This was politically prudent: wage-setting was not part of the board’s purview and any intimation that it was doing so would invite criticism and controversy.

Integration of production was one important criterion the board did rely on. In a series of cases, the board ruled that in certain industries, operations were so thoroughly interconnected that separate craft units, each with the right to strike, would pose a more or less constant threat to industrial peace because any one of them could shut down an entire factory and throw everyone else out of work.Footnote 45 CIO unionists spelled out plainly the cascading effects of a work stoppage by craftsmen. They insisted that craft units’ destabilizing effects made them incompatible with the board’s charge to promote labor peace. Craftsmen, ironically and disingenuously, denied the strategic importance of their work. In truth, the leverage their strategic position gave them was often an unspoken premise behind skilled workers’ bids for craft severance: by exploiting their own power vis-à-vis management, they could get a better deal than they could within an industrial union, where their leverage was used primarily on behalf of their unskilled and semiskilled union brethren. The NLRB dealt with the integration of production issue regularly, most notably in 1948, when it made clear it would cast an especially skeptical eye on craft severance petitions in highly integrated industries.Footnote 46 With few industries meeting the board’s criteria, however, that ruling proved to be a fairly narrow exception to the overall trend toward granting craft severance.

The “true craft” criterion was the most important litmus test the board applied to craft severance petitions. In applying it to a petitioning group, the distinction the board made was between true craftsmen, who deserved the opportunity to bargain separately, and impostors, whose skills, training, and bargaining history did not entitle them to that privilege. When the group was what the board called a “dissident faction,” i.e., a group that lacked “true craft” characteristics and instead was aiming to get a better deal for itself, its request for an election would be denied.Footnote 47 With this premise established, defining what constituted a distinct craft became the board’s major challenge. Over time, the board refined the true craft test, making it stricter in some instances and more lenient in others. Regardless, once the board gave it doctrinal form and substance, it was what mattered: if skilled workers wanted control over their collective bargaining demands, they had to meet those specific criteria.

Distinctions between craft workers and everyone else hinged on the tiniest details.Footnote 48 When electricians at Hughes Tool petitioned for severance from an industrial unit, they adduced highly specific evidence of the distinctive nature of their work and training: the partition that separated their workspace from other employees’ work areas; the role of the U.S. Apprentice Training Service in supervising their training; the exclusion of two men employed as helpers from their proposed bargaining unit; even the special stencil used to mark their tools. On the basis of this evidence, the board ordered an election that the IBEW local won in a landslide.Footnote 49 The length of time it took to train for a job was another important criterion. During a wartime dispute, the crane operators at Houston’s Sheffield steel mill sought separate representation by the Operating Engineers. A representative from the incumbent industrial union, the Steelworkers, pointed out that the training time on one type of crane used at the mill was as little as two to three weeks. That information, along with other factors, convinced the board to deny the petition.Footnote 50 Because of requirements like these, when unskilled workers tried their hand at craft severance, they got nowhere. At the Sinclair refinery in 1951, the AFL-affiliated Hod Carriers Union sought permission to form a unit of unskilled workers as part of an effort by several AFL locals to break up an OWIU industrial unit. The NLRB granted every petition for a craft-unit election except that proposed by the Hod Carriers.Footnote 51

The true craft test amounted to an evasion, specifically an evasion of the board’s ongoing role in politicizing the nation’s wage structure.Footnote 52 By imposing such specific requirements on petitioning unions, the board tried to present craft severance as a policy tool that allowed craft workers to protect their “craft identity.” The simple truth was that just about every petitioning group was ipso facto a “dissident faction,” that is, workers seeking greater leverage in collective bargaining. It was also the case that some of those groups conformed closely to long-standing traditions of what defined a craftsman. But few, if any, petitioned the board because their “craft identity” was under assault. In fact, one of the board’s litmus tests for “craftiness” was that the petitioning workers had maintained their craft identity even while part of an industrial bargaining unit. By definition, craft severance was not a means of restoring a lost craft identity.

It was the extremely neat and politically convenient congruence between those two categories, i.e., between “dissident factions” angry about wages and workers whose training and work arrangements were essentially those of traditional craftsmen, that allowed AFL craft unions to use NLRB bargaining-unit elections to reshape the nation’s wage structure more to their liking. As had been true in the 1930s, money, more so than matters of identity, was at stake in appropriate bargaining unit policy.

If NLRB officials and petitioning unions talked incessantly about industrial peace and “craft identity,” what reason is there to think craft severance was really about wages? The answer is straightforward: unions’ behavior. As one CIO official described the economic motivations behind craft severance petitions, “[AFL unions] will come around and say to the pipefitters: ‘You men are only getting $1.80 an hour or $2.00 or $2.20 an hour. That is ridiculous. The plumbers here doing pipefitting work are making $3.50. You join our union and you will get it, too.’”Footnote 53 The experience of workers at International Harvester’s McCormick Works illustrates the relationship between wage differentials and NLRB bargaining-unit decisions. After the CIO-affiliated Farm Equipment Workers Organizing Committee organized the plant in 1936, across-the-board increases in absolute, not percentage, terms quickly reduced wage differentials between unskilled and skilled workers. In 1941, however, the plant’s pattern makers voted to join the AFL-affiliated Pattern Makers League after the NLRB granted them a craft severance election. Almost immediately, the skilled workers “succeeded in pushing the pattern shop/common labor rate to its highest point in [plant] history.”Footnote 54

The pattern makers’ collective bargaining outcomes contrast sharply with those of a second group of craftsmen, millwrights, who remained part of the industrial bargaining unit. During World War II, with the NWLB controlling wage differentials, the wage premium enjoyed by the two groups of craftsmen moved in tandem. After wartime wage controls lapsed, however, the pattern makers used the autonomy their craft bargaining unit gave them to negotiate an increase in skill-based wage differentials. Meanwhile, the millwrights, still members of the larger industrial bargaining unit, lost ground relative to their unskilled coworkers.

By the late 1940s, at McCormick Works and in thousands of other workplaces, skilled craftsmen were like an irredentist movement reclaiming lost territory. A more detailed examination of the industrial complex that stretches from Galveston to Beaumont helps capture the scope, timing, and objectives of the craft severance movement. Over the course of the 1940s, skilled industrial workers in southeast Texas, as with their counterparts around the country, both helped effect the policy shifts in Washington and benefited from those changes as they occurred. From 1935 to 1940, skilled workers did not file many craft severance cases, in part because there were still relatively few industrial units for craftsmen to sever themselves from. During World War II, the volume of cases spiked dramatically, but the board continued to reject more than a third of the petitions. Between the end of the war and 1950, by contrast, the proportion of denials dropped to less than 10 percent of the total number of petitions filed (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Historical trends in craft severance.

To appreciate what was at stake for industrial workers in these fast-proliferating craft severance disputes, consider the cafeteria staff at the Firestone plant in Port Arthur, Texas. In 1944, the plant’s blue-collar workers were poised to vote on their preferred union representation.Footnote 55 But rather than a single election, nine separate elections were imminent. In eight, an AFL craft union opposed the OWIU, a Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) industrial union, for various fractions of the plant’s maintenance and production workers. If the OWIU won all eight, it would be able to bargain on an industrial basis for those workers. In the ninth, the OWIU ran unopposed to be the representative of the cafeteria workers.

The cafeteria workers were, in effect, served up as leftovers in a battle between the OWIU and eight AFL craft unions. The AFL unions had no interest in representing them. The OWIU stood ready to bargain for them, but they understood, as did all parties concerned, that a bargaining unit comprised of only the cafeteria workers would have been an untenable situation. On their own, the cafeteria workers lacked the leverage needed to win a good contract. For those familiar with collective bargaining dynamics in modern industrial plants, whether they were detractors or defenders of the CIO, this was industrial unionism’s worst-kept secret: the nation’s industrial workers were not equally powerful, even if the voting structure of their unions did not reflect that.

As a result, the OWIU sought instead to represent all of the plant’s workers in a single, industrial bargaining unit with the cafeteria workers only a small part of a much larger whole. The stakes were high. Despite being arguably the plant’s least powerful contingent of employees, the cafeteria workers could anticipate strong wage increases if they belonged to a single bargaining unit represented by the OWIU. On the other hand, under the same scenario, skilled workers could expect to see their power in the union diminished by the much larger number of unskilled and, especially, semiskilled workers who comprised the bulk of the plant’s workforce. With reduced power came a loss of bargaining strength and slower wage growth.

All over southeast Texas, disgruntled craftsmen rejected this outcome. In ingenious ways, they fashioned craft units that ensured craftsmen had what they lacked in CIO unions: a voting majority. In many cases, this meant constructing the smallest possible bargaining unit. Even a unit comprised of all the workers practicing a craft—the obvious choice if protecting craft identity were the issue at stake—was sometimes not small enough. Craftsmen split into still smaller units as they sought the bargaining-unit size and composition that optimized their leverage against management. In many instances, a craft union sought multiple separate bargaining units in a single factory, all represented by the same union local. The workers involved were distinguished not by the craft they practiced but by other factors, especially the department in which they worked. In one extreme case of this broader pattern, the Pipefitters sought no fewer than six separate bargaining units at a Phillips refinery. At a Firestone plant, two sheet-metal workers petitioned for their own unit. Already part of an AFL-affiliated craft union, they requested craft severance from a craft union. Petitions like these put the lie to the NLRB’s contention that protecting craft identity, not restoring wage differentials, was the primary issue at stake as workers sought the advantages of craft unit bargaining.Footnote 56

The tensions among and within craft unions were also apparent in the ubiquitous intra-AFL squabbles over the proper bargaining unit. At Southern Acid, the AFL-affiliated Operating Engineers favored an industrial unit, while other AFL unions intervened to split the plant up into multiple units. There was so much disagreement, however, among the craft unions that they could not come up with a coalition that would rival the Operating Engineers; some wanted the Metal Trades Council to represent them, others preferred the Labor & Trades Council, and the electricians wanted a separate unit. Similar conflicts at Goodyear Tire and Rubber led the president of the Houston Labor and Trades Council to request intervention by the international office. In another instance, the Painters complained that other craft unions “have been guilty of individual certification or individual petitioning for their crafts in many of these plants, leaving the rest of the plants to fall in the hands of the C.I.O. or company unions.” At the Abercrombie and Harrison refinery, an attempt at a joint bargaining arrangement was derailed by disputes among the participating AFL unions over a range of issues.Footnote 57 The difficulties craft unions had working together made clear that each sought maximum bargaining power for its members, not the defense of traditional craft prerogatives.

Craft unions’ approach to including unskilled and semiskilled workers in their craft bargaining units is revealing. When they believed common laborers were an unsavory appetizer they had to swallow to get to the tasty main meal—NLRB certification as the proper bargaining agent—they included them. They did so, however, with the crucial proviso that craftsmen would retain a voting majority. At the Sinclair refinery, the IAM petitioned in 1944 to represent employees in the refinery’s garage. Men working as porters, greasers, truck washers—more or less the human “rubbish” Daniel Tobin infamously denounced as unfit for AFL membership—were part of the Machinists’ proposed unit. Under duress during cross-examination, the IAM representative conceded that it was “pretty generally true” that the IAM excluded unskilled workers. He also, however, stated that they were agnostic on the issue: they would include the unskilled workers in the proposed bargaining unit, or exclude them according to the wishes of the board.Footnote 58

Racism was almost certainly a significant factor motivating skilled workers to leave industrial unions in southeast Texas. Roughly 95 percent of skilled industrial workers in southeast Texas were white in 1950. By contrast, slightly more than half of the unskilled laborers in the three main industrial sectors examined here were African American, and it was unskilled workers in these plants who benefited most from wage compression.Footnote 59 As Judith Stein observed, “The virtue of any industrial union is that those with the most bargaining power help those with little, who are usually unskilled laborers. This truth had racial implications in the South because the workers with the least bargaining power and civil rights in the society were black.”Footnote 60 The facts on the ground bore out this logic: the 1940s, the period when industrial unions expanded their membership dramatically, were a singularly positive decade for black male industrial workers in terms of wage increases.Footnote 61 Craft severance, in other words, undermined the wage gains of African American workers more than it did those of white workers.

But in the 1940s, restoring lost wage premiums, not fighting against racial justice, was the craftsmen’s principal concern as they filed craft severance petitions.Footnote 62 Since nearly half of the unskilled laborers and nearly all semiskilled workers were white, the diminished industrial units craftsmen left behind were still comprised overwhelmingly of white workers. As craftsmen appreciated, because white semiskilled operatives had most of the voting power in contract negotiations, even if every African American and Latino worker were excluded from the bargaining unit, wage contracts with compressive tendencies would continue to be ratified. Rather than racial privilege, craftsmen focused on a single criterion in drawing their bargaining units: ensuring skilled workers had the voting majority in whatever bargaining units they created, even if it left other white workers behind in industrial units, bereft of the bargaining power the skilled workers had imparted. Moreover, craftsmen’s fissiparous tendencies often did not abate even with the formation of bargaining units comprised only of white craftsmen. Rather, white craftsmen constantly sought not just to bargain separately from black and Latino workers, or even from white unskilled and semiskilled workers, but from other white craftsmen.

From the welter of bargaining-unit disputes, a pattern emerges: craftsmen endeavored, using any means available to them, to maximize their own collective bargaining leverage. Skilled workers spoke the language required by the NLRB about their craft identity. But their actions reveal that bargaining outcomes, not identity, motivated them. Wage data suggest that craftsmen’s careful policing of bargaining-unit boundaries paid off. In other words, whether craftsmen were represented by an AFL craft union made a difference. At the General Tire plant, which was represented by a consortium of AFL unions, skilled workers enjoyed a significant wage differential over unskilled laborers. In 1947, IBEW-affiliated electricians, for example, received 19 percent more in hourly wages than pumpers, a semiskilled production job, and fully 105 percent more than laborers. By comparison, at Crown Central, a refinery represented by the OWIU, skilled craftsmen earned only 3 percent more than pumpers and 59 percent more than laborers.Footnote 63

Whether looked at from the perspective of the NLRB’s offices in Washington or the cafeteria of a Texas oil refinery, the craft severance movement helps us better understand the midcentury era’s remarkable egalitarianism. In particular, it helps explain whether the Great Compression, especially its timing, can be attributed to institutions intended to alter the distribution of income in society or if, instead, it was the product of market forces, specifically a growing supply of skilled workers that reduced the wage gap between them and the least paid. Put differently, did the income distribution that prevailed in the United States for roughly a quarter century come about because social groups understood their economic interests were in tension and then used institutions to resolve that tension through an intensely political process? Or was it a benevolent but largely unintended consequence of predistribution factors, in particular increased educational attainment?

Recent studies have suggested that institutions, especially unions, deserve more credit for launching and sustaining the Great Compression than they have received. The story of the craft severance movement supports the intuitionalist account. It also complicates it. It suggests that union structure mattered and, consequently, specifying a union effect on the wage structure is insufficiently precise. Instead, in assessing the impact of collective bargaining on midcentury wage structures, a distinction should be made between craft and industrial unions. Moreover, because after 1935 union structure was to a large degree a function of NLRB appropriate bargaining-unit determinations, the craft severance movement suggests that shifts in bargaining-unit policy should be evaluated as part of a comprehensive account of the effects of collective bargaining on wage differentials. It is possible that the relevant distinction may prove to be less between unions that were nominally craft or industrial and more between NLRB-designated craft and industrial bargaining units. Taking into account changes in NLRB policy means, in turn, also taking into account the rightward turn in American political culture of which those policy changes were a part. Finally, the craft severance movement suggests that organized labor had a role not only in initiating wage compression during the 1940s but also in ending it. By the end of the decade, industrial unions were on the defensive, not just because of stiffened resistance from employers but also from counterattacks by workers seeking craft severance. The success of those counterattacks helps explain the end of wage compression in the 1950s and suggests that the income distribution cannot be changed in significant and durable ways without precipitating intense social conflict.

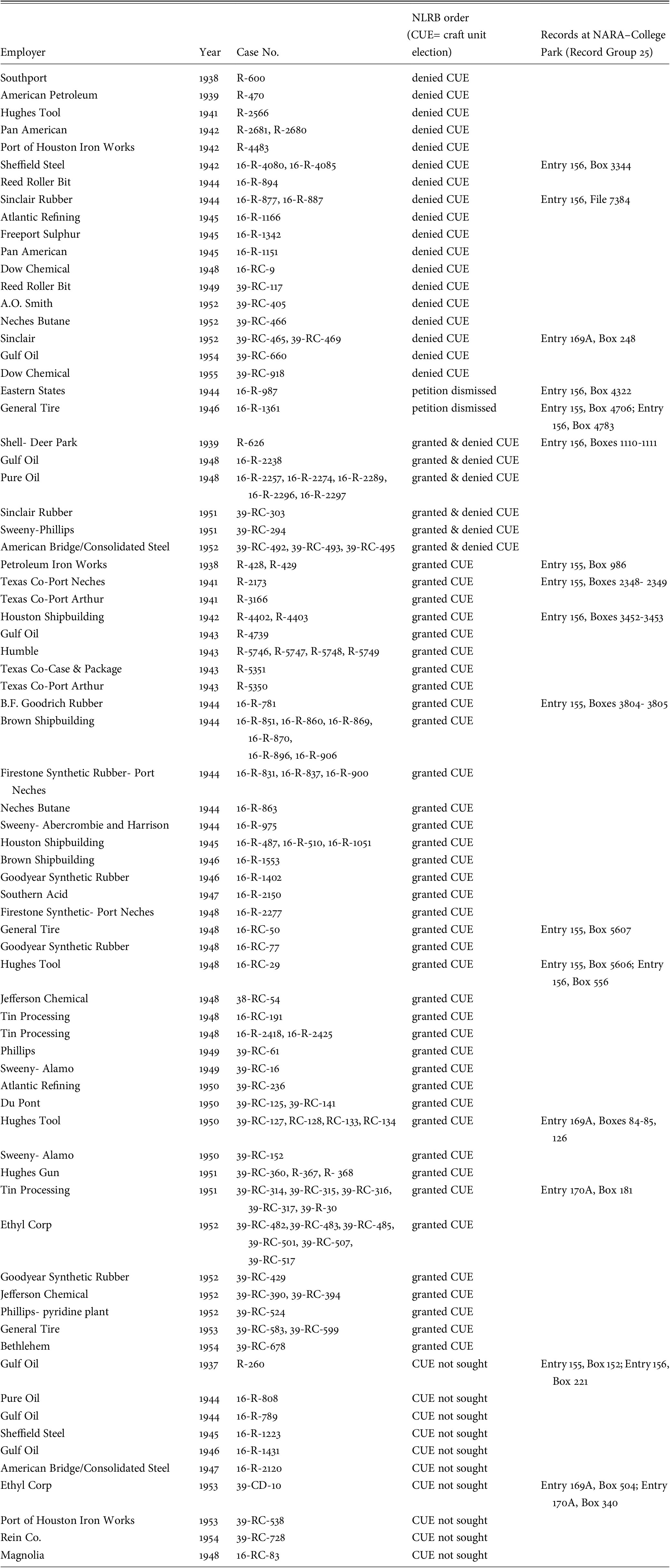

Appendix

The conclusions in the article were drawn from an analysis of 116 NLRB cases. Each case relates to craft bargaining units. The cases are from the Gulf Coast industrial complex, which is bounded by Houston and Freeport to the west and Port Arthur to the east. In each case, the NLRB issued its order between 1935 and 1955.

This list is the result of an effort to identify as many of the craft severance cases that emerged from that region during those two decades as possible. It is not, however, exhaustive. There may be dozens, or possibly even hundreds, more cases that meet the search criteria. Compiling a fully comprehensive set of relevant cases is not possible given how the NLRB records are organized and how the texts of the opinions were written. For example, used as a search term in the NLRB’s online database, “craft severance” does not generate a complete list of the cases in which craft severance was involved because the board did not always use that phrase in its orders even when craft severance was the issue at hand. Most of the cases listed below were located instead by searching an online database of board decisions (located at nlrb.gov) using the names of firms known to the author to be doing business in southeast Texas in this era.

For some entries, multiple NLRB case numbers are listed. This reflects a common NLRB practice. Because each craft union seeking a craft unit at a given workplace typically filed a separate craft severance petition (e.g., one petition for Boilermakers, one for Pipefitters, etc.), multiple craft severance petitions were often filed at the same employer at roughly the same time. In those circumstances, the NLRB often assigned each petition its own case number but clustered the cases together as one large dispute, held a single hearing, and issued a single order that addressed each petition filed.

Alternatively, the board also sometimes used a single case number in situations where multiple groups of craftsmen each sought to create their own craft bargaining unit at a workplace. This is reflected in the set of cases where the outcome is designated as “granted and denied.” In a number of those cases, the board assigned a single case number even though multiple craft unit elections were sought.

For some of the cases, the National Archives hold additional relevant NLRB records, including case files, dockets, and hearing transcripts. For disputes where such materials have been located and consulted, the location within the NLRB record group is listed.