Introduction

In comparison to its well-developed health-care system that provides universal coverage for 99 per cent of the population, Taiwan's publicly funded long-term care (LTC) system has historically been under-invested in and is still in the developmental stage. The term LTC system in this paper refers to the public arrangements that either regulate the private market and providers, provide collective public funds for services, or directly deliver services for those disabled and hence in need of daily living support over an unspecified prolonged period of time (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Llena-Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011). This system may contain both institutional and/or non-institutional (such as community- or home-based) services. Taiwan has one of the most rapidly ageing populations in the world (Lin and Huang, Reference Lin and Huang2016). A national survey in 2010 found that around 12.7 per cent of the older people need some form of LTC service (Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW), 2016: 11). Reflecting the demographic transition and unmet LTC needs, public expectations and demands for LTC system reforms are increasing.

This paper first provides a brief overview of the development of the LTC system in Taiwan. In 2006, an initial reform arrangement was put in place, designed to expire in ten years – the LTC 1.0 Plan. Subsequently, in 2017, a more extensive public framework was put in place – the LTC 2.0 Plan, which expanded the government role in both funding and delivery. The LTC 2.0 Plan seeks to build a tax-funded community-based universal LTC system, modelled after the ideal of the Nordic model. The first purpose of this paper is to present and analyse possible explanations for the changes of the recent LTC system reforms. Then, in the second part, the paper evaluates the potential institutional and socio-cultural tensions that are embedded in the current LTC conditions in Taiwan. The institutional tensions include the conflicts between the existing dominant foreign worker caring model and the LTC 2.0 Plan, and the discontinuity between health and social care governance structure. The socio-cultural tensions include conflicting value systems between the Confucian ethics of Taiwanese society and the communitarianism and universal social citizenship upheld by the LTC 2.0 Plan. The second purpose of this paper is to identify these potential tensions and analyse the possible explanations. The paper concludes with policy implications for the LTC system in Taiwan and other high- and middle-income countries.

As a newly developed non-Western democracy, Taiwan has been seeking to establish modernised welfare arrangements in different policy fields, such as public education, pensions and health care in earlier times, and LTC and child care more recently. On the one hand, the strong economy provides the material conditions for public funding, while the vigorous civil society that developed through the process of democratisation has gradually acquired the capacity to hold the government accountable for people's demand for health and social care (Lin, Reference Lin, Hsiao and Lin2001; Wong, Reference Wong2004; Deng and Wu, Reference Deng and Wu2010). A broader policy implication from Taiwan's experience in implementing National Health Insurance (NHI) suggests that the social health insurance model adapted from Western European countries is a plausible model for a publicly funded health system in a middle-to-high-income East Asian country. On the other hand, the very different socio-cultural context in Taiwan and other newly developed countries, as against that in traditional welfare states in the West, challenges the plausibility of this modernisation project. These features make Taiwan a case that is worth investigating.

This paper utilises both a literature and document review and case studies as the foundation of its research approach. The materials analysed were obtained from a review of official documents, press releases and statistics from related government agencies. Related government agencies from the executive branch include the Office of the President, the Executive Yuan, the MOHW, the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA), the Ministry of Labor and the Ministry of the Interior Affairs (MOI) of the Taiwanese government; those of the legislative branch include the Parliamentary Library and the Laws and Regulations Database. These documents and statistics are primary sources accessed through the governmental agencies’ official websites. The survey data of socio-cultural values was retrieved from the Taiwan Social Change Survey Database, which is operated by the Institute of Sociology and the Center for Survey Research of Academia Sinica in Taiwan. These governmental and survey materials are purposefully chosen for their relevance in terms of the rapidly changing reform and revision agendas of the LTC system. Using these materials from different sources, the paper aims to better identify the potential tensions that are embedded in the LTC reform. Among the materials, the Ten-year Long-Term Care Plan 2.0 Prospectus (MOHW, 2016) is the most important source of the structural and regulatory framework of the reform proposal; its contents are scrutinised thoroughly and compared with other key documents and the existing literature.

The paper serves to summarise the past development of the publicly funded LTC system in Taiwan and advance the future discussion of LTC in Taiwan. By providing design details and ideas for reforms, and analysing the potential tensions that exist under current conditions in Taiwan, this paper can contribute conceptually to the literature in LTC system development and more general welfare policy studies, and practically contribute to the knowledge base of policy planners and reformers in middle- and high-income countries.

A brief overview of the LTC system

For the past few decades, Taiwan has largely depended on the private sector to fund and provide LTC services, while the government mainly served a regulatory and guiding role in the establishment and operating of private LTC institutions. There was no integrated national-level publicly funded LTC financing or delivery system (Chiu, Reference Chiu2001). For most people, their LTC needs were self-funded through personal or family resources. The government, however, had a significant role in opening up the import of foreign labour to supplement the under-developed LTC system. Starting in 1992, the Council of Labor Affairs (now the Ministry of Labor) initiated the foreign worker import project (Lee and Wang, Reference Lee and Wang1996). Ever since then, the self-funded employment of foreign workers from South-East Asia has become the dominant LTC model. The LTC system remained relatively unchanged until 2007.

In 2007, the MOI initiated the Ten-year Long-Term Care Plan (hereafter noted as the LTC 1.0 Plan), attempting to establish a universal community-based LTC system through subsidies from general tax revenues from local and central governments (MOI, 2007; Wang and Tsay, Reference Wang and Tsay2012). However, due to various reasons, including strict subsidy criteria, a shortage of care workers, a limited budget and inflexible service options, the LTC 1.0 Plan was soon found to be ineffective – few citizens were aware of the subsidy programme, and the utilisation of services was much lower than expected (Lin and Huang, Reference Lin and Huang2016; MOHW, 2016). Faced with growing LTC needs and other external pressures, the Department of Health (now the MOHW) assembled the Long-term Care Insurance (LTCI) Planning Team to prepare for establishing a single-payer social insurance system to replace the LTC 1.0 Plan, which had only been planned to be implemented from 2007 to 2016 (Nadash and Shih, Reference Nadash and Shih2013).

The rationale for choosing the LTCI model was straightforward. Considering the successful experience of the social insurance model from the NHI, in terms of securing sufficient funds for universal accessible and quality health-care services with efficient insurance administration and regulation (Cheng, Reference Cheng2015), the planners assumed that once finances for LTC services was secured by the LTCI, the service capacity from private care providers would gradually expand and meet society's LTC needs. The LTCI would be funded by mandatory pay-roll premiums,Footnote 1 which would be identical to the NHI except that the premium rate would be around one-quarter of the NHI. The NHIA, which is the government agency supervised by MOHW that functions as the single-payer insurer of NHI, would also be the single-payer insurer of LTCI. According to the experience of the NHI, this arrangement was expected to maintain low administrative costs for operating the social insurance and grant the insurer a powerful regulatory role in setting rules of interactions between insurance stakeholders. For example, the insurer could use varieties of payment incentives to stimulate the LTC providers’ behaviours in care provision and quality control to conform to MOHW's policy goals.

Under this rationale, the LTCI was put into the reform agenda, and several legal and administrative complementary measures were set up for the implementation of LTCI. In June 2015, the Long-Term Care Services Act was enacted by the Legislative Yuan (the highest legislative body of Taiwanese government, similar to a parliament or congress), setting a regulatory structure for LTC providers and institutions, such as definition of different types of LTC services, business registration and management of LTC providers, the basic physical and human resource criteria of a LTC provider, the local and central governments’ responsibility in registration and regulation, and penalties for violating laws. In February 2016, the Long-Term Care Insurance Act was reviewed and adopted by Executive Yuan (the highest authority of the executive branch of Taiwanese government) and sent to the Legislative Yuan for deliberation and legislation (MOHW, 2017). The NHIA, the would-be single-payer insurer of LTCI, had also started policy communication efforts towards the future stakeholders for the implementation of LTCI. This was the outlook right before the abortion of the LTCI proposal and initiation of the major LTC system reform in 2017: the Ten-year Long-Term Care Plan 2.0 (hereafter noted as the LTC 2.0 Plan) (Tsay, Reference Tsay2016; Executive Yuan, 2017).

The reform of 2017

Initiating the LTC 2.0 Plan

As mentioned in the previous section, the LTCI reform was abruptly aborted. How did this abrupt shift from the social insurance model to the community-based model happen? The answer seems to be political. In January 2016, the ruling Chinese Kuomintang (KMT, or Chinese Nationalist Party) was defeated by the opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in the general election. The DPP won the presidency as well as a majority in the Legislative Yuan. One of the results was that the minister and the advising team of scholars and bureaucrats of the MOHW who supported the LTCI model were replaced. The new team is determined to propose a tax-funded community-based model for LTC, as the previous LTC 1.0 Plan was designed and implemented by roughly the same team in 2007 when the DPP was last held the presidency (the DPP held the presidency from 2000 to 2008; between 2008 and 2016, the KMT held the presidency). The tax-based LTC model was also one of the major platforms proposed by the DPP before the 2016 elections (Tsai, Reference Tsai2015). This explanation reduces the abrupt shift in policy to the different political ideologies/beliefs between the two professional teams affiliated with different parties.

However, beyond this somewhat straightforward explanation, there might be more profound reasons that the new government decided to abort the LTCI and embrace a tax-based system. One might be that it was because the employers and huge companies strongly opposed the LTCI model, as they had little desire to pay for the extra LTC pay-roll premium for their employees. If the new government adopted a tax-based model, then the direct financial burden will be borne by the government (as tax revenues) rather than out of employers’ pockets. Since these companies are the DPP's major constituents, the DPP would have a strong incentive to abort the LTCI reform.Footnote 2 This explanation seems logical as well; however, it is questionable in that these corporations are not only the DPP's constituents, they are also the KMT's major constituents as well. Why would they oppose the LTCI model only under the DPP's ruling but not the KMT (before the General Election)?

Another related reason may be that, culturally, most Taiwanese still perceive that the responsibility of LTC should fall primarily on individuals and families; therefore, the new government does not have any incentive to impose a universal LTCI. Not only the employers would oppose this, but the general public would oppose it as well. It may be the case that familialism has not receded and that LTC remains a private affair in the minds of most Taiwanese (this issue will be analysed in later sections). In brief, the abrupt shift in strategy in LTC reform is complex; a sufficient discussion of it is beyond the scope of this paper and requires further investigation.

In December 2016, the Executive Yuan formally announced the Ten-year Long-Term Care Plan 2.0 Prospectus (MOHW, 2016). The LTC 2.0 Plan expands on the previous tax-based LTC 1.0 Plan (2007–2016), and will continue from 2017 onwards. Although not explicitly stated as such, the LTC 2.0 Plan is considered practically to be part of the narrowly defined welfare system, meaning that only Taiwanese citizens are entitled to the subsidised services provided by the plan. On the other hand, the health-care services funded by the NHI are universal in the sense that all legal residents, regardless of their nationality and citizenship, are eligible (and actually mandated by the law) for participation in the NHI. The difference means that about 688,000 foreign residents living in Taiwan (as of July 2017) (National Immigration Agency, 2017) – immigrant workers, business people, students – will be covered by the NHI – although most of them are unlikely to remain in Taiwan long enough to become old and in need of LTC. In the following two sections, the financing and delivery arrangements of the reform are summarised.

Financing

Different from the LTCI model, which was designed to be based on an independent legal basis (the Long-Term Care Insurance Act), the LTC 2.0 Plan is essentially an administrative project of central and local government; there was no specific law that was explicitly enacted for the plan. As such, there are concerns about its financial viability over the long term. Financial independence that is mandated by a specific law was considered one of the most advantageous features of the social insurance model advocated by the proponents of the LTCI model. They argued that the tax model will suffer from unstable financial sources and hence is harmful for the development of the whole LTC system (Council for Economic Planning and Development et al., 2009; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lin, Wu, Cheng and Fu2013).

To respond to this concern, a first step for the new government was to secure the project's funding. In January 2017, the Long-Term Care Services Act was amended and added articles that list the funding sources for LTC services, including the earmarked tax from 10 per cent of the Estate and Gift Tax and the Tobacco and Alcohol Tax. In April 2017, the Tobacco and Alcohol Tax Act was amended accordingly, raising the tobacco tax 270 per cent (on average from US $0.4 to $1.1 per pack of cigarettes). In addition, according to the Regulation on Central Government Subsidising Local Government, county-level local governments are also obligated to allocate a certain proportion of local tax revenues to fund LTC services. The new plan takes effect in June 2017 and will last until 2026. The projected budget of the LTC 2.0 Plan is around US $540 million in 2017 and this totals US $15.7 billion from 2017 to 2026, as listed in the prospectus (MOHW, 2016).

A potential issue is that the responsibility for funding the plan is not explicitly written in any of the specific laws or regulations mentioned above. The articles in these laws only generally state that these funds should be allocated towards LTC services, but not specifically for the LTC 2.0 Plan. For instance, Article 15 of the Long-Term Care Services Act states that the government should set up a ‘special fund for providing long-term care services’, and that the sources of the fund include earmarked estate and gift tax and tobacco tax. Under current policy, this fund is indeed used on the LTC 2.0 Plan; however, it does not state that the fund should be or must be used on the LTC 2.0 Plan. In addition, as reported in January 2018, the amount of money from the earmarked estate and gift tax and tobacco tax was not as much as expected. The actual amount was only 24 per cent of the expected amount (Chen and Tsai, Reference Chen and Tsai2018). Moreover, the smoking rate is gradually decreasing in Taiwan, from 27 per cent in 2002 to 18.7 per cent in 2012 (from 48.2 to 32.7 per cent for male citizens and from 5.3 to 4.3 per cent for female citizens) (Ministry of Finance, 2014). This public health accomplishment would, ironically enough, make the finance sources for LTC 2.0 unstable. Furthermore, considering that the tobacco tax is a flat tax, it is regressive in nature. This means that members of lower socio-economic groups that tend to smoke more will fund the LTC services more; hence raising the question of unequal allocation of care responsibilities. In short, whether these finance sources would be sufficient for the ten-year-long implementation of the plan remains uncertain.

Another issue is that the expected budget is projected on the assumption that the plan would be effective in preventing the occurrence of disability, so the disability rate and LTC needs would not increase proportionately as the elderly population increases (MOHW, 2016: 166). This is most likely an overly confident assumption.

Delivery

The purpose of the LTC 2.0 Plan is to actualise ideals of ‘ageing in place’ and ‘active ageing’ by building a universal care system with multi-type and continuous services based on ‘the spirit of communitarianism’ (MOHW, 2016: 48). The specific strategies adopted by the plan include expanding the subsidised population, expanding subsidised LTC service types, providing noticeable signs for the LTC providers and simplifying reimbursement processes compared to the LTC 1.0 Plan.

First, the target subsidised population includes those age 65 years or older (55 years or older for Native Taiwanese) with LTC needs as defined by activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) scores or with frailty as defined by the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures frailty index, those age 50 years or older with dementia as defined by Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, and those with disabilities as verified according to the process regulated by the People with Disabilities Rights Protection Act.Footnote 3 The plan is universal, in that every senior and/or disabled citizen could apply for the subsidised services; however, the question remains to what kind of services and to what extent?

The subsidised LTC service types in the LTC 2.0 are many, but with certain limitations. There are different criteria for different items but a common characteristic of all these items is that the subsidised services will only cover either a limited amount of care an individual would need or a limited proportion of an individual's care expenditures. In principle, the LTC 2.0 Plan is universal in terms of funding and subsidy criteria, but citizens with LTC needs still have to pay a significant amount out-of-pocket for the full volume of the services they need.

The A-B-C Community Caring Network will be the basic delivery unit, combining all types of services on a municipally managed community basis. The Level C centres are the smallest ones, which will be built in every third village, providing respite care for family care-givers, delivery of nutritional meals and preventive care to avoid disability or postpone deterioration. The Level B centres will be built in every school district, providing daily life care, home care, small-size multi-function services, group homes or institutional residential care. The Level A centres will be built in every township or district, providing comprehensive LTC services and integrating services provided in the other two levels by mobile care and transport teams circuiting throughout the community. This ideal delivery model is portrayed in the LTC 2.0 Plan (MOHW, 2016: 92–93).

To summarise, the reform proposes a tax-based, universal, comprehensive, community-based LTC system: one that appears to be similar to the Nordic or Scandinavian model (Einhorn and Logue, Reference Einhorn and Logue2010; Vabø and Szebehely, Reference Vabø, Szebehely, Anttonen, Haikio and Kolbeinn2012). However, this is indeed a rather simplistic understanding of the Scandinavian model. In recent years, the welfare systems in Scandinavian countries have also faced external challenges and are under reform (Szebehely and Trydegård, Reference Szebehely and Trydegård2012; Halvorsen et al., Reference Halvorsen, Hvinden and Schoyen2015; Ranci and Pavolini, Reference Ranci and Pavolini2015; Saltman et al., Reference Saltman, Hagen and Vrangbaek2015; Szebehely and Meagher, Reference Szebehely and Meagher2018).

Nevertheless, this simplistic imagination is derived from its specific context. After democratisation, civil society organisations, activists and scholars that were excluded under the authoritarian governance started to have the chance to express their policy stances and influence the policy-making process. One faction advocates building the welfare system after the Scandinavian universal model, demanding that it is the public or society's collective responsibility to secure a universal public provision of health and social care through redistributive schemes and participatory procedures.Footnote 4 These are the spirits and values that are evoked when people think and talk about the Scandinavian model in Taiwan. The prospectus of the LTC 2.0 Plan also explicitly states that the purpose of the project is firstly to ‘build a high quality, affordable, and universal LTC system that upholds a communitarian spirit’ (MOHW, 2016: 48).

The LTC 2.0 Plan could be considered a result of the diffusion of policy innovations, a Western institutional design that is grounded in the East Asian context. It seeks to reform Taiwan's LTC system towards a more comprehensive one, in terms of both the levels of coverage and the share of public expenditure in LTC services. Could a reform modelled after the ideal of the Nordic or Scandinavian LTC model be imported and implemented in Taiwan's specific context? What challenges will it encounter? In the following sections, the paper evaluates several unaddressed institutional and socio-cultural tensions that could be observed from the proposed plan.

Institutional tensions

The dominant foreign worker caring model

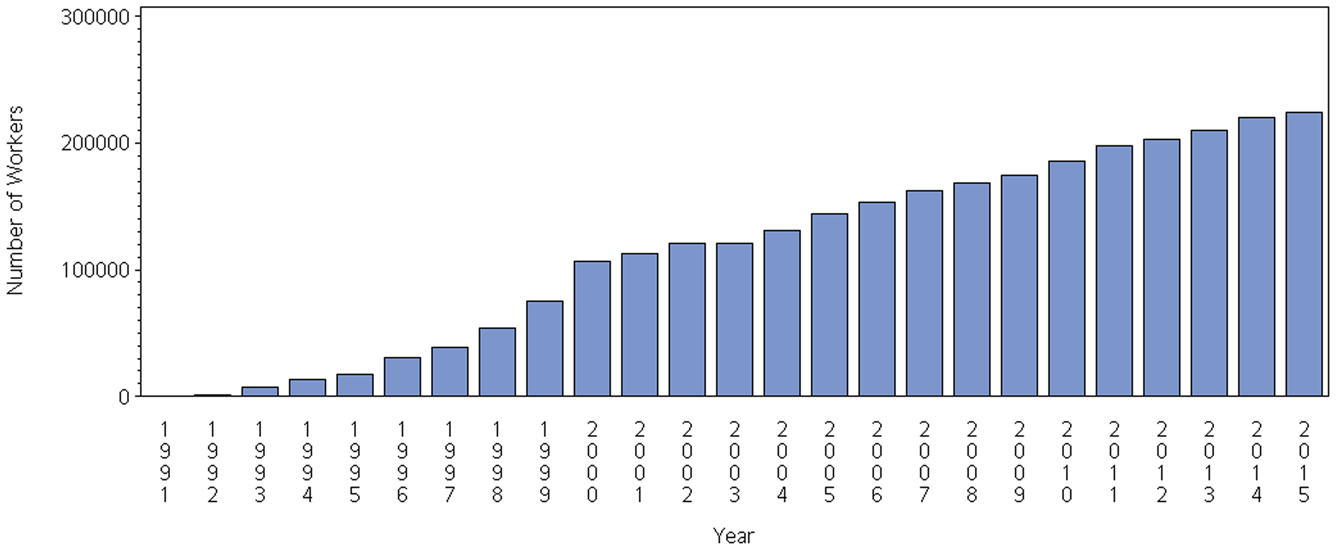

The LTC 2.0 Plan does not fit well with the currently dominant caring model in Taiwan – reliance on privately paid and delivered services provided by around 220,000 foreign workers from South-East Asia, mostly Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam. Any individual who is assessed as disabled according to ADL and IADL scores could be qualified as an employer to hire a foreign LTC worker. As mentioned earlier, the import of foreign labour began in 1992, and the number of foreign workers has grown progressively ever since (Figure 1). These workers come to Taiwan on a regular three-year contract basis, which could be renewed up to three times (at most 12 years). However, these foreign workers are not able to apply for immigration or any other form of permanent residency.Footnote 5 This is the reason why they are termed ‘foreign’ workers, not ‘migrant’ workers (as most of the literature does) in this paper.

Figure 1. The number of foreign workers who worked in the long-term care sector in Taiwan, 1991–2015.

Foreign workers are imported because the cost of their services is much lower than that of Taiwanese care-givers, and also because of the long working hours they can provide (Song, Reference Song2015). In most cases, an in-home foreign LTC worker provides intensive care as needed by his or her (mostly her) employer; the working conditions are often poor and are not protected by the Labor Standards Act (Chen, Reference Chen2015). Hiring a Taiwanese worker to provide the same amount of care loading as a foreign worker would cost the employer 100–150 per cent more. For example, the standard wage for a foreign worker is US $750 per month, while for a Taiwanese worker this would be US $1,640 per month (according to the service price list provided by a non-governmental organisation; Peng Wan-Ru Foundation, 2017). The reform plan would subsidise US $300 per month for one year for qualified employers to hire Taiwanese workers rather than foreign ones (MOHW, 2016: 103). However, in comparison with long-term hiring costs, the effectiveness of this incentive is dubious.

For the LTC 2.0 Plan, these huge numbers of foreign workers are the elephant in the room. The plan neither integrates them into the subsidy scheme, nor addresses how the community model it proposes would compete with the foreign worker caring model in convenience of use and effectiveness of costs. Furthermore, some subsidised items such as skill training for family care-givers are not available for those who have already hired a foreign worker (MOHW, 2016: 82).

Discontinuity between health and social care governance

The discontinuity between health and social care governance is rooted in the divided administrative structure of health and social care in the Taiwanese government (Chiu, Reference Chiu2001; Lin, Reference Lin2014). The predecessors of the MOHW were the Department of Health of the Executive Yuan and the Department of Social Affairs and the Bureau of Children in the MOI. The Department of Health has been the competent authority on public health and medical affairs since its establishment in 1971. On the other hand, the Department of Social Affairs was in charge of means-tested welfare programmes for middle- and low-income older people and other specified sub-groups such as low-income households, victims of domestic violence and abused children. Such was the social care provided by the government before the LTC 1.0 Plan was initiated in 2007. The double-headed development of health and social care administrations was meant to be solved by a central government agencies reorganisation project. In 2013, under the Organic Act for Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Department of Health, Bureau of Children and Department of Social Affairs were integrated and promoted as a second-level executive agency, the MOHW. However, the governance responsibilities of health and social care were still allocated to different departments within the MOHW.

Even after the MOHW was established, the governance of LTC drastically shifted one time in 2016. The LTCI proposed by the KMT administration was planned and developed by the NHIA, which was reasonable because the LTCI was modelled after the NHI. Since the DPP came into office in 2016, the planning and implementation of the LTC 2.0 Plan is the responsibility of some internal divisions of the MOHW and the Social and Family Affairs Administration. As many governmental reorganisation cases have shown, restructuring and renaming the bureaucracy may not necessarily lead to meaningful results, which ought to be the improvement of care outcomes in terms of clinical outcomes, efficiency and client/patient satisfaction (Leutz, Reference Leutz1999). Recently, the MOHW has been restructuring again to establish a new internal division to integrate all LTC affairs that are currently scattered over MOHW's internal divisions and the Social and Family Affairs Administration (Yu, Reference Yu2018).

This discontinuity could cause service discontinuity between the provisions of curative health care and LTC. The curative health-care services have been covered by the NHI since 1995, and community care is covered by the LTC 2.0 Plan starting in 2017. The hospital discharge planning, which is meant to be the nexus between these two systems, was included as a reimbursed item (Code: 02025B) into the Fee Schedule and Reference List for Medical Services of the NHI in April 2016. The NHI reimburses the hospital 1,500 points (around US $45) for each patient per inpatient use for hospital discharge planning services (NHIA, 2017). However, this strategy put more emphasis on the health-care side, while leaving the LTC 2.0 Plan off the table. Any evaluation of the effectiveness of this strategy is not yet available at this moment, but from some preliminary investigations, it appears that current hospital discharge planning is far below expectations (Lee, Reference Lee2017). The discontinuity between health and LTC governance should be monitored closely after the LTC 2.0 Plan is implemented.

Socio-cultural tensions

As Saltman and colleagues have rightly put it, health and social care systems are shaped by the social values that are grounded in the historical and cultural context of a society (Saltman, Reference Saltman, Saltman, Busse and Figueras2004; Saltman and Bergman, Reference Saltman and Bergman2005). For a plan that is adopted from the universal tax-based care model that originated from the Scandinavian context, there are several complications in terms of social and cultural differences that should be noted for it to be implemented in Taiwan.

Conflicting value systems

First, there exist potential conflicts between traditional Confucian ethics and the communitarianism upheld by the LTC 2.0 Plan. Despite the fact that Taiwan has transformed into a modern state after democratisation in the 1990s, traditional Confucian ethics are arguably still the dominant value system. A crucial feature of this system is the differential social order, in which the responsibility of care for a disabled person is mainly shared among an individual's family members or relatives, a moral imperative required by filial piety (xiao, 孝) (Zhang, Reference Zhang2010). The public, either an individual's fellow citizens or the state, does not share this responsibility; hence, a publicly funded system is difficult to justify. The allocation of the responsibility of care is based on private relationships rather than shared equally or reciprocally between people. If the government were to be held accountable for securing public provisions of LTC services, it would be because the virtuous rulers – the ruling party that runs the government – are expected to be generous and benevolent. That is, they should be concerned about people's needs and do their best to fulfil these expectations. According to Mencius, this is called people-oriented thought (minben, 民本思想), a characteristic of a good and just ruler who takes care of his or her people as if they are his or her own children. This metaphor makes the democratic government resemble the king or the emperor in ancient Chinese (Middle Kingdom) political institutions and extends the relationship between family members to resemble the relationship between the ruler and the subjects. The responsibility of care is confined in this family-based relationship.

This understanding of a ‘public’ system is very different from the communitarian and egalitarian values embedded in a publicly funded LTC system modelled after the Scandinavian model, in which the responsibility for care is shared among the democratic citizenry. The services provided by the tax-based LTC system are the common advantages pursued by the fellow citizens together, upholding the notion of reciprocity and solidarity to justify redistribution efforts (Morone, Reference Morone2000; Saltman and Bergman, Reference Saltman and Bergman2005; Einhorn and Logue, Reference Einhorn and Logue2010). Therefore, responsibility as well as the universal entitlement to services is based on citizenship, and the institutional arrangement for the allocation of this responsibility is made through the democratic processes of strong civil society participation and deliberation in a corporatist framework (Einhorn and Logue, Reference Einhorn and Logue2010). Although there are debates on whether the universal Scandinavian model is sustainable in the era of austerity and marketisation (Cox, Reference Cox2004; Szebehely and Meagher, Reference Szebehely and Meagher2018), the relationship between citizens and the state remains the same, as the responsibility of care is equally and reciprocally shared between citizens through the state's good stewardship (Saltman and Ferroussier-Davis, Reference Saltman and Ferroussier-Davis2000).

While the LTC 2.0 Plan makes an explicit claim about its commitment to the value of a universal, community-based model (MOHW, 2016: 48), it will be implemented on a society that has a different value system. Will this be plausible? One response is to argue that traditional Confucian ethics would not necessarily conflict with universal values. It might be the case that Confucianism in modern Taiwanese society has already been transformed in a way that is compatible with democratic governance and the social citizenship (Yeh, Reference Yeh2010). Take the NHI for example. As a social health insurance adopting the principle of solidarity from developed countries, the NHI has been generally perceived as performing well in providing equitable, efficient and quality health services (Cheng, Reference Cheng2015), and has had high satisfaction rates of around 80 per cent in the past decade (NHIA, 2016: 102). If such a publicly funded health system is sustainable, then the LTC 2.0 Plan would have no reason to fail in terms of value differences.

Another response is to dodge this question and argue that, considering the details of the LTC 2.0 Plan, its intrinsic value is not what it explicitly claims in the prospectus. What the plan actually applies is a universal community-based model that aims to provide LTC services supplementary to the services provided by families.Footnote 6 Therefore, the basic unit of care is not communities but families. The state's role is not to secure services based on social citizenship, but rather to intervene in those families that do not have adequate capacity. This interpretation maintains that the responsibility of care is still firstly allocated to families, which is consistent with traditional Confucian ethics. This policy arrangement is similar to those of Southern and Central Europe. For example, in Italy, the public LTC systems are mostly about providing cash benefits for family care-givers. Scholars call this ‘supported familialism’, for under such arrangements, although more public money is invested and the public or the state seems to share more responsibility of care, this does not de-familialise the system to become more egalitarian in terms of equal responsibility among the democratic citizenry; rather, it supports family members ‘in keeping up their financial and care responsibilities’ (Saraceno and Keck, Reference Saraceno and Keck2010: 676).

Understanding of normal functioning and disability

One issue related to the tensions between traditional Confucian ethics and the modern universal care model rests in the contested definition of a core concept for a publicly funded LTC system – disability. Conceptually, citing Kane and Kane (Reference Kane and Kane1987), the LTC 2.0 Plan defines disability through its definition of LTC:

Long-term care is a set care including long-term medical, nursing, and individual and social support provided to a physically or mentally disabled person in a period of time; its purpose is to promote or maintain the bodily function, and to improve independent and autonomous abilities for normal daily life of an individual. (MOHW, 2016: 10)

Operationally, as mentioned above, the plan uses professional clinical scales, such as ADLs, IADLs, the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures frailty index and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, for the verification of people with disabilities as the criteria to determine the levels and amounts of services that could be granted to a client. Both the conceptual and operational definitions adopted by the plan are clearly individualistic and consistent with the social citizenship and the legal system that respect and protect individual rights and autonomy. This individualistic understanding of human needs assumes a value judgement that what is ‘normal’ and should be maintained is the autonomy of life and functioning of an individual, rather than that of any other collective unit such as a family.

Yet within the traditional Confucian ethics value system, the order and stability of a society is maintained through the self-sufficiency of families. A dependent individual who does not have normal functioning would not be an issue as long as his or her daily life could be well taken care of by his or her family. For a dependent elder, the younger family members have the responsibility of care under the principle of filial piety (xiao, 孝); for a dependent youth, the older family members have the responsibility of care under the principle of nurturing (yangyu, 養育). This two-way responsibility is strongest between parents and children, but would also diffuse towards other lineal relatives by blood, such as grandparents and grandchildren, and other collateral relatives, such as uncles/aunts and nephews/nieces. A nationally representative survey administered in 2016 reveals that 88 per cent of Taiwanese agree that men should give living expenses to their parents; 73.4 per cent agree that women should do so; and these results are stable from 2006 to 2016 (Table 1) (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Chang, Liao and Hsieh2017). Traditional Confucian ethics is not only a dominant social value upheld by Taiwanese people, but also a legal obligation. According to the Civil Code, Article 1114, lineal relatives by blood, siblings, and the head and the members of a house have mutual obligations to maintain. If the obligation is not fulfilled by one of the parties, the others could make a complaint against him or her in civil court.

Table 1. Social values regarding maintenance obligations in Taiwan, 2006 and 2016

Source: Data are adapted from the Taiwan Social Change Survey Project 2016 (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Chang, Liao and Hsieh2017).

In sum, the family-based collective understanding of human needs assumes a value judgement about what is ‘normal’ and should be maintained that is inherently different from what has been assumed by the LTC 2.0 Plan.

The potential tensions between universalism/social citizenship and Confucian ethics/familial responsibility presented here should not be overlooked. The protection of social rights, what the LTC 2.0 Plan has projected, is more demanding than the protection of civil and political rights for a nascent democracy, for it requires more coercive participation and resource reallocation between citizens.

Discussion and policy implications

This paper provides a brief overview of the developmental history and the financing and delivery mechanisms of the major LTC reform in Taiwan. As a preliminary evaluation, this paper identifies several institutional and socio-cultural tensions of the plan.

Dependence on foreign or migrant workers is not a particular phenomenon in Taiwan. Many developed countries such as Italy, Austria and Germany in Europe (Da Roit and Le Bihan, Reference Da Roit and Le Bihan2010) and Japan and South Korea in Asia have a similar issue (Song, Reference Song2015). The flow of labour in the age of globalisation fills the care gap that is neither covered by the family nor by the state. Both parties may be easily tempted to hand the burden of care to those who are willing to accept the lowest wage while providing the most intensive services. However, the private funds allocated to the foreign workers could crowd out resources for the development of domestic personnel and services, leaving the system more reliant on the supply of those foreign workers. Dependence on foreign workers may also create barriers to Taiwanese workers entering the job market, because when LTC services could be supplied with a low wage level accepted by foreign workers, employers would not have the incentive to raise the wage to the extent that is acceptable for Taiwanese workers, resulting in the ‘segregated labor market’ (Chen, Reference Chen2015). Note that due to the Taiwanese government's active role in regulating the private agencies matching and importing foreign workers, the issue of the grey market of LTC human resources is not as significant as in other countries that also depend heavily on foreign workers in the LTC sector (Da Roit et al., Reference Da Roit, Le Bihan and Österle2007; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Winkelmann, Rodrigues and Leichsenring2015).

In addition to the job market issue, this convenient and financially preferable way of securing LTC needs might also limit people's acceptance of other models of public LTC provision, causing people's suspicious attitudes towards the LTC 2.0 Plan reform. As a study has found, political parties and social welfare organisations that benefited from the foreign worker caring model have formed alliances, opposing the reforms that would jeopardise their interests (Chien, Reference Chien2018). To change this pattern, a transformation of the understanding of responsibility of the care and caring model would be needed. Policy makers may also want to implement stronger communication agendas on diffusing the ideals of the LTC 2.0 Plan – ‘active ageing’ and ‘ageing in place’ – for they are not only more humane and respectful of autonomy, but more importantly, they are less costly.

The discontinuity within the administrative structure seems as though it should be one that is relatively easy to address, but it is not. The competition of powers and the evasion of responsibilities will likely continue between the health administration and social administration authorities. These two are not only administrative authorities; each of them represents a body of professionals and a monopolised field of enterprise. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the dynamic of interests between the two fields. The point here is that from the LTC policy perspective, a balanced interdisciplinary partnership should be built (Hudson, Reference Hudson2002; Lymbery, Reference Lymbery2006), so that the discontinuity of governance will not lead to a discontinuity of care.

The socio-cultural tensions and differences in value systems are the most challenging factor with the LTC 2.0 Plan. The history of comprehensive publicly funded LTC systems in East Asia is relatively short. South Korea, which is also struggling between a Confucian tradition and modern welfarism, adopted a social LTCI plan in 2008. The introduction of Korean LTCI has been perceived as a part of the consolidation of welfare states; hence, increasingly people understand the entitlement to LTC services as a right, and the ‘Confucian legacies might not last long’ (Kim and Choi, Reference Kim and Choi2012: 883). This finding is revealing for Taiwan's LTC reform. It seems that external pressures such as rapid ageing, changing family formations and augmented care needs could eventually drive society to be more willing to accept a different value system. If this is the case, policy makers could take advantage of it and transform the LTC system into one that could relieve individuals from the sufferings of burden of care that bind them in family. In addition, in the existing literature on welfare, debates on the East Asian productivist model could be inspired by the case of Taiwan. The fact that the LTC reform is now led by the MOHW, rather than by economic agencies of the government (like with the national pension and the NHI reforms), shows that Taiwan might have passed through productivist welfare capitalism (Holliday, Reference Holliday2000) or a developmental welfare state era (Lee and Ku, Reference Lee and Ku2007), in which the health and social policies are to serve the purpose of economic development, and moved towards a universal entitlement based on citizenship for the purpose of social protection and even the active redistribution of social risks. It might not yet be the time to ‘discard productivism’ (Holliday, Reference Holliday2005); however, there are signs that East Asian welfare systems are transforming (Choi, Reference Choi2012; Y-M Kim, Reference Kim2008; MMS Kim Reference Kim2016).

The core issue of the LTC reform is how the responsibility of care should be allocated between the state, families and individuals. Policy makers in newly developed countries look after traditional welfare state models and attempt to establish or reform these models accordingly to provide more universal coverage and higher levels of social protection against unmet LTC needs, health-care needs and other needs derived from social risks. However, while LTC system designs could be adopted, the contexts and the embedded norms and values that these innovations rest on will differ among societies. The case of Taiwan analysed in this paper presents a preliminary evaluation of the issue.

Future research is needed to evaluate the influence of the institutional and socio-cultural tensions addressed in this paper. In the following few years, the implementation of the LTC 2.0 Plan and the development of the LTC system in Taiwan will be a focal point of observation. These experiences would be useful for health and LTC policy makers in high- and middle-income countries that are also considering establishing a tax-based universal LTC system, as Taiwan shares similar external pressures with these countries, mostly in terms of a stagnant economy and ageing population which has contributed towards ever-rising demands for care.

Author ORCIDs

Ming-Jui Yeh 0000-0003-0748-9462

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Richard B. Saltman, Chieh-hsiu Liu, Kai-Heng Lin, Ta-Yuan Chiu and Yi-Zhen Wu for their comments.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.