INTRODUCTION

In today’s international business environment companies are expanding geographically. With globalization, the multicultural work group, or team, comprised of diverse members from different national backgrounds and cultures working together on a common purpose is fast becoming the norm within the organization (Cohen & Bailey, Reference Cohen and Bailey1997; Earley & Mosakowski, Reference Earley and Mosakowski2000; Yukl, Reference Yukl2013). The growth of electronic communication capabilities is supporting virtual teamwork by multicultural teams comprised of members working across locational, temporal, and relational boundaries on a common purpose (Ebrahim, Ahmed, & Taha, Reference Ebrahim, Ahmed and Taha2009; Gera, Reference Gera2013). As organizations increase their reliance on face-to-face and virtual teams for their future success, organizational leaders are concerned with enhancing the effectiveness of their teams (Florida & Goodnight, Reference Florida and Goodnight2005). Research indicates emotional intelligence is essential to team performance (Druskat & Wolff, Reference Druskat and Wolff2001; Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, Reference Goleman, Boyatzis and McKee2002), with emotional intelligence as a significant predictor of team effectiveness in face-to-face teams (George, Reference George2002) and virtual teams (Pitts, Wright, & Harkabus, Reference Pitts, Wright and Harkabus2012). For this article, we investigate emotional intelligence as a strategy to support the collaborative process in face-to-face and virtual teams. We also investigate how emotional intelligence may impact team-based collaboration.

Team-based collaboration encompasses team members working together on a common goal (Slater, Reference Slater2005). Collaboration among team members is an essential factor in leveraging team effectiveness in a variety of common goals (DeCusatis, Reference DeCusatis2008; Romero, Galeano, & Molina, Reference Romero, Galeano and Molina2009). For example, collaboration in face-to-face teams is a predictor of effective innovative and creative team outcomes in undergraduate students (Barczak, Lassk, & Mulki, Reference Barczak, Lassk and Mulki2010) and graduate students working on major team-based class projects (Stavros & Cole, Reference Stavros and Cole2015). Similarly, collaboration in virtual teams is a predictor of effective decision making in teams comprised of US students from different universities (Lin, Standing, & Liu, Reference Lin, Standing and Liu2008) and in teams comprised of US students and Indian students working on a judgment task (Paul, Seetharaman, Samarah, & Mykytyn, Reference Paul, Seetharaman, Samarah and Mykytyn2004). Ferrazzi’s (Reference Ferrazzi2014) review of research on virtual teams suggests virtual teams that are able to collaborate outperform face-to-face teams by as much as 43%.

Research on the effects of collaboration on team effectiveness in face-to-face and virtual teams identifies inclusion, integration and compromise, and open communication as important characteristics of collaboration (Hattori & Lapidus, Reference Hattori and Lapidus2004). Social interactions characterized by open communication and a sense of trust are created through emotional intelligence (Kerr, Garvin, Heaton, & Boyle, Reference Kerr, Garvin, Heaton and Boyle2006). Emotional intelligence refers to a set of emotion processing abilities that lead to improved social interactions – these emotion processing abilities are awareness and management of emotions in self and others (Mayer & Salovey, Reference Mayer and Salovey1997). In teams, emotional intelligence encompasses team members having the capacity to perceive, recognize, regulate, and manage the emotions of themselves and others in the team (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, Reference Mayer, Salovey and Caruso2004). While research points to emotional intelligence (Druskat & Wolff, Reference Druskat and Wolff2001; Goleman, Reference Goleman2006; Jordan & Ashkanasy, Reference Jordan and Ashkanasy2006; Mount, Reference Mount2006; Sala, Reference Sala2006) and collaboration (Hattori & Lapidus, Reference Hattori and Lapidus2004; Romero, Galeano, & Molina, Reference Romero, Galeano and Molina2009; Whitaker, Reference Whitaker2009; Dietrich, Eskerod, Dalcher, & Sandhawalia, Reference Dietrich, Eskerod, Dalcher and Sandhawalia2010) as important factors in team effectiveness, the link between emotional intelligence and collaboration in teams and among team members is less clear (Barczak, Lassk, & Mulki, Reference Barczak, Lassk and Mulki2010).

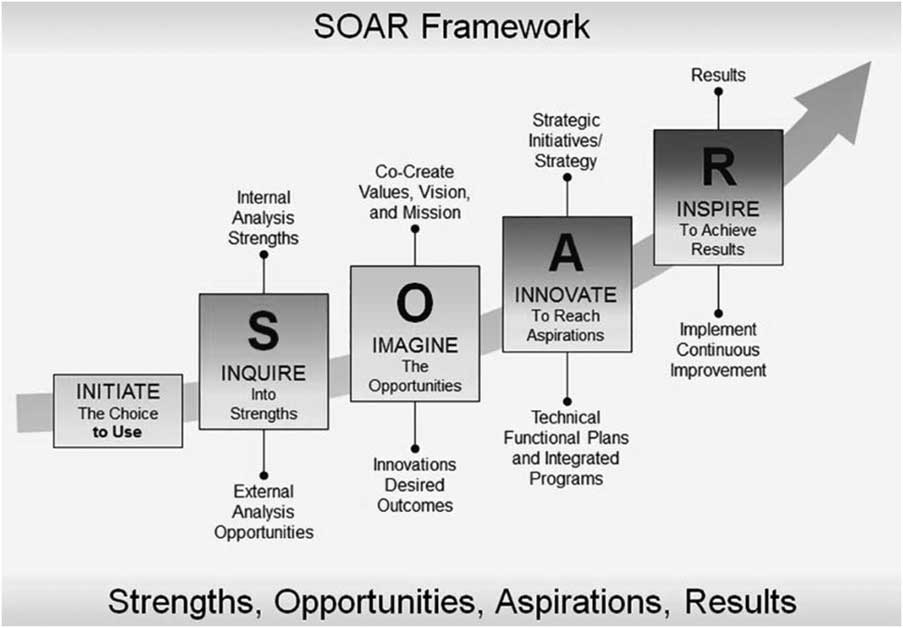

Collaboration is also discussed in the context of strategy and strategic thinking (Gray, Reference Gray1985). Collaboration among team members may be enhanced through the use of collaborative strategies that are positive, inclusive, and supportive of active sharing and exchanging of knowledge (Shaw & Lindsay, Reference Shaw and Lindsay2008). A collaborative strategy that provides a framework for members of a virtual team to approach strategic thinking, planning, and leading from a profoundly positive approach is SOAR (strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results). Growing out of the theory and practice of positive organizational scholarship and appreciative inquiry (AI), SOAR is a positive approach to strategic thinking and planning that allows members of a team to construct their future through collaboration, shared understanding, and a commitment to action (Stavros, Cooperrider, & Kelley, Reference Stavros, Cooperrider and Kelley2007). The SOAR framework provides a flexible approach that invites the whole team into a strategic planning or strategy process by including relevant stakeholders with a stake in the success of the team, including team members, to engage in a generative dialogue to generate new ideas, new innovations, and the best in people to emerge (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, Reference Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros2008; Bushe, Reference Bushe2013; Stavros & Cole, Reference Stavros and Cole2013). SOAR was included in this study to investigate how emotional intelligence may impact collaboration.

The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship among emotional intelligence, collaboration, and SOAR in a sample of professionals who currently work in teams. We focus on understanding the effect that team member emotional intelligence has on collaboration, and we characterize any differences in this effect between team members of face-to-face and virtual teams. We also focus on how emotional intelligence may have an effect on collaboration by studying SOAR as a mediator between emotional intelligence and collaboration. Results of our research have important implications for teams and their pervasive use in business.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES

Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence, the first of three study constructs used in this study, functions as the independent variable in the study model. Emotional intelligence is an evolving extension of the quantitative measures of intelligence, such as the intelligence quotient, referring to the capacity to reason about and tap into emotions for the purposes of knowledge (Goleman, Reference Goleman2006). Emotional intelligence is broadly defined as a construct representing a set of competencies for identifying, processing, and managing emotions (Zeidner, Roberts, & Matthews, Reference Zeidner, Roberts and Matthews2008). The primary theory of emotional intelligence utilized in this study is based on the four emotional intelligence abilities of Mayer and Salovey (Reference Mayer and Salovey1997): awareness of emotions (own and others), management of emotions (own and others), emotional understanding, and emotional facilitation (generation of emotions). These abilities are further refined for understanding how emotional intelligence works in teams by focusing on self- and other-awareness and management of emotions; in the context of teams, emotional intelligence is generally considered to be a value added competency to various aspects of individual and group performance, namely collaboration (Jordan & Troth, Reference Jordan and Troth2004).

Today’s business climate is characterized by limited face-to-face interactions. Each personal interaction that occurs must be as successful as possible. Increasing the value of personal interactions requires more than intelligence, it requires understanding of emotions in leaders and teams (i.e., understanding of emotional intelligence). Research suggests that emotional intelligence has the ability to impact performance outcomes in organizations; in particular those in which successful negotiation, cohesion, and collaboration is desired (Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Garvin, Heaton and Boyle2006). Collaboration is a process of social interaction, where one’s ability to influence the emotional climate and behavior of others can strongly influence performance outcomes. As an emerging leadership attribute, emotional intelligence competency is seen to be increasingly important to an individual’s ability to be socially effective and therefore more adept at enabling successful collaborative outcomes.

Emotional self-awareness improves one’s ability to negotiate, compromise, and seek the best alternatives that yield positive results (Xavier, Reference Xavier2005). Thus, individuals who are emotionally self-aware may have a positive attitude that contributes to effective conflict management and resolution of disagreements. For teams, just as the personal development of emotional intelligence may improve an individual’s ability to manage change, the development of emotional intelligence among team members may improve the team’s ability to manage change. This is especially important because as emotional intelligence competencies assist teams to dispel norms and develop new and more prosperous cultures supporting a common goal, the more effective the team may become.

Emotional intelligence and teamwork

Emotional intelligence has gained popularity as an essential personal factor for effective teamwork as leaders with high emotional intelligence are successful in negotiating and resolving conflict (Blattner & Bacigalupo, Reference Blattner and Bacigalupo2007; Anand & Udayasuriyan, Reference Anand and Udayasuriyan2010). Modern business cultures reflect accelerated changes in work force, impact of technology, industrialization, and globalization. People currently need to function in a world vastly different from that of previous generations. To function effectively in what are now inherently natural collaborative environments, individuals and leaders working collaboratively require emotional intelligence aptitude.

Research suggests that when developing and using talents crucial for organizational effectiveness, managers with high emotional intelligence obtain results from employees that are beyond expectations (Chen, Jacobs, & Spencer, Reference Chen, Jacobs and Spencer1998). Effective managers steer their own feelings, acknowledge the feelings of subordinates concerning their work situation, and intervene effectively to enhance morale. Moreover, close to 90% of success in leadership positions can be attributed to emotional intelligence (Anand & Udayasuriyan, Reference Anand and Udayasuriyan2010). Nwokah and Ahiauzu (Reference Nwokah and Ahiauzu2010: 159) note: ‘Under the guidance of an emotionally intelligent leader, people feel a mutual comfort level. They share ideas, learn from one another, make decisions collaboratively, and get things done as they form an emotional bond that helps them stay focused even amid profound change and uncertainty.’ Therefore, an environment for collaborative success is created when emotionally intelligent leadership is combined with an emotionally intelligent team. Optimizing this relationship for team effectiveness and collaboration necessitates the development of emotional intelligence skills within the collaborative team.

Emotional intelligence and collaboration

Collaboration implies sharing risks, resources, and responsibilities in order to achieve a common goal that would not be possible if attempted individually (Romero, Galeano, & Molina, Reference Romero, Galeano and Molina2008). Collaborative team members integrate themselves into a collaborative culture which comprises an awareness of self and others, seeks a willingness to adapt for the benefit of all, and demonstrates supportive and positive behaviors to enhance the capabilities of others (Romero, Galeano, & Molina, Reference Romero, Galeano and Molina2009). The link between emotional intelligence and collaboration occurs when the emotional intelligence competencies of recognizing, understanding, managing, and using emotional information about oneself and others are displayed by team members (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis2007). Collaboration may be enhanced in teams with emotionally intelligent team members because awareness and management of emotions may enhance group-based emotions that increase collaborative performance (Cameron, Reference Cameron2013). For example, when people are high in emotional intelligence, strong relations with others are formed that support collaboration (Mayer & Caruso, Reference Mayer and Caruso2002).

Team-based collaboration

Collaboration, the second of three study constructs used in this study, functions as the dependent variable in the study model. Team-based collaboration refers to members of a team working together on a common goal (Slater, Reference Slater2005). Characteristics of collaboration include inclusion, integration, compromise, and open communication (Hattori & Lapidus, Reference Hattori and Lapidus2004). Inclusion draws upon the potential and expertise of individuals, the need for attention in managing the complexity of collaboration, and the need for an ongoing commitment to knowledge sharing in the development of collaborative strategies within a team (Shaw & Lindsay, Reference Shaw and Lindsay2008). Integration and compromise involve an active intent to support collaborative strategies through the establishment of a common ground, unified strategies, and integration of ideas (Rahim, Reference Rahim1983a, Reference Rahim1983b). Teams seeking compromise develop supportive and positive behaviors to enhance the capabilities of others and to adapt for the benefit of all (Romero, Galeano, & Molina, Reference Romero, Galeano and Molina2009). Communication involves information exchange for mutual benefit among individuals and teams, aligning of efforts so that more efficient results can be achieved, and sharing of resources to reach compatible goals (Aram & Morgan, Reference Aram and Morgan1976).

The emotional intelligence factors of self-awareness and self-management of emotions correlate with collaboration factors of inclusion, integration and compromise, and communication in collaboration. Awareness and management of others’ emotions is a necessary influence in resolving conflict for the purpose of achieving compromise in a collaborative environment (Mita & Debasis, Reference Mita and Debasis2008). Concern for self and others promotes integration of ideas, open communication of resources, cooperation, and inclusion of all team members focused on shared goals (Romero, Galeano, & Molina, Reference Romero, Galeano and Molina2009). The essence of this study is that teams with team members who are aware of emotions and who manage emotions are teams that will experience positive collaboration. To this end, we expect that there is a significant positive relationship between emotional intelligence and team-based collaboration (see Figure 1, Hypothesis 1a). Further, given the importance of emotional intelligence to the effectiveness of face-to-face and virtual teams (George, Reference George2002; Pitts, Wright, & Harkabus, Reference Pitts, Wright and Harkabus2012) we expect there may be differences in the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration in team members working in face-to-face versus virtual teams (see Figure 1, Hypothesis 1b).

Hypothesis 1a: Emotional intelligence has a positive impact on team-based collaboration.

Hypothesis 1b: Team type moderates the relationship between emotional intelligence and team-based collaboration.

Figure 1 Proposed study model Note. DV=dependent variable; IV=independent variable; MED=mediating variable; MOD=moderating variable; SOAR=strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results.

SOAR

SOAR, the third of three variables used in this study, functions as the mediating variable in the hypothetical model. SOAR is a ‘strengths-based framework with a participatory approach to strategic analysis, strategy development, and organizational change’ (Stavros & Saint, Reference Stavros and Saint2010: 380). SOAR integrates AI with a strategic planning framework to create a transformational process that inspires organizations and stakeholders of the organization to engage in results-oriented strategic planning efforts (Stavros, Cooperrider, & Kelley, Reference Stavros, Cooperrider and Kelley2003). AI ‘is a collaborative search for the best in people, their organizations, and the world around them. It involves the discovery of what gives life to a living system when it is most effective, alive, and constructively capable in economic, ecological, and human terms. AI involves the art and practice of asking unconditional positive questions that strengthen a system’s capacity to apprehend, anticipate, and heighten its potential’ (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, Reference Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros2008: 3).

In contrast to traditional, diagnostic-based approaches to strategic thinking that focus on problems, deficits, and weaknesses, such as the SWOT framework (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats), the SOAR framework is an alternative, dialog-based approach to strategic thinking that emphasizes strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results (see Figure 2). SOAR-based strategic thinking engages organizational members to frame organizational issues from a solution-oriented perspective that is generative and focused on organizational strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and desired results to build a positive future (Stavros & Wooten, Reference Stavros and Wooten2012). As a framework for strategic thinking and planning, SOAR describes the elements and activities that team members, teams, and organizations should follow in their collaborative strategic thinking and planning if they are following a strengths-based approach (Stavros, Cooperrider, & Kelley, Reference Stavros, Cooperrider and Kelley2007).

Figure 2 The SOAR (strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results) framework Source. Adopted from Stavros, Cooperrider, and Kelley (Reference Stavros, Cooperrider and Kelley2007).

The SOAR framework is inherently team-oriented, collaborative and inclusive, and seeks to involve all individuals having a perspective and stake in the organization’s strategic planning initiatives (Stavros & Cole, Reference Stavros and Cole2015). SOAR begins with an inquiry into what works well, followed by the identification of possible opportunities for growth. SOAR enables stakeholders to identify and build on strengths, define specific goals and strategic initiatives, and identify enabling objectives through strategic inquiry with an appreciative intent. When applied to teams and team members, the collaborative process of dialogue and strengths-based information exchange may lead team members to consider positive outcomes that may occur when the team is at its best, and to identify what and where the team wishes to be in the future (Cole & Stavros, Reference Cole and Stavros2016). Table 1 depicts activities within the SOAR framework that act as enablers for the successful interaction of team members (Stavros, Cooperrider, & Kelley, Reference Stavros, Cooperrider and Kelley2003).

Table 1 Strategic inquiry–appreciative intent: inspiration to SOAR

Note. SOAR=strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results.

Team members high in emotional intelligence are likely to contribute to the overall emotional intelligence of the team, recognize their roles in the team structure, are more prone to empathetic behavior, form strong relationships, and enable a cohesive support system in and among themselves. This cohesiveness facilitates trust and innovation, as well as efficient decision making and appears to increase the likelihood of team collaboration, which appears to enhance team effectiveness (Melita Prati, Douglas, Ferris, Ammeter, & Buckley, Reference Melita Prati, Douglas, Ferris, Ammeter and Buckley2003). The SOAR framework has the potential to help team members understand the importance of dialog-based collaboration to develop strategy, measurable objectives and methods to achieve a visionary future based on strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results. The manifestations of SOAR relationships are exemplified in self-reflection, mutual understanding, and a consideration for the collaborative group as a whole. As participants discuss opportunities, shared aspirations, and desired results from a strengths-based perspective, they share a vision for a positive future with energy, vitality, and commitment (Stavros & Hinrichs, Reference Stavros and Hinrichs2009).

We propose that emotional intelligence abilities are closely linked to a SOAR-based pattern of idea exchange and are supportive of the competencies necessary to achieve desired results from a SOAR-based perspective. We also propose that SOAR and collaboration are linked because an effective team is a cohesive group of people who collaborate in support of common aspirations and a common vision (Katzenbach, Reference Katzenbach1998). Accordingly, in our analysis of the emotional intelligence domains and their influence on positive collaboration outcomes, we tested SOAR as a mediator of the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration. One way to investigate the presence of mediators in relationships among variables is to study the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator (Cheung & Lau, Reference Cheung and Lau2008). To this end, we expect a significant indirect effect of SOAR on the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration (see Figure 1, Hypothesis 2). Results of Hypothesis 2 will address how emotional intelligence may have an effect on collaboration.

Hypothesis 2: SOAR mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and team-based collaboration.

METHODS

Research design

We used a quantitative cross-sectional survey design with moderating and mediating variables to evaluate the relationship among emotional intelligence, collaboration, SOAR, and team type (face-to-face vs. virtual). We recruited the study sample from the population of professionals on LinkedIn who are currently working in teams. Invitations to participate were distributed across a wide range of professionals from industry, academia, and government via LinkedIn groups in the following study areas: emotional intelligence, leadership, AI, teamwork and team effectiveness, strategic planning, change management, project management, academia, financial management, general business management, and several industrial organizations. The survey was administered over a 4-week period via the eSurvey website SurveyMonkey and N=308 respondents provided voluntary consent to participate. Research participants in this study were protected according to the federal requirements specified by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Code of Federal Regulations, 45 CFR 46. In accordance with federal requirements, approval to conduct research with human participants was obtained from the Lawrence Technological University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The survey instrument consisted of 68 questions divided into five sections: (1) team characteristics, (2) emotional intelligence, (3) team collaboration, (4) SOAR, and (5) demographic characteristics. One of the questions on team characteristics asked respondents to select the type they are currently working in (face-to-face vs. virtual). Demographic characteristics included participant gender, age, ethnicity, and education level. Emotional intelligence was measured by the 16-item ‘WEIP-S’ (Work Group Emotional Intelligence Profile-Short Form; Jordan & Lawrence, Reference Jordan and Lawrence2009) to establish areas of respondent competency in four emotional intelligence abilities helpful for understanding how emotional intelligence works in teams (Mayer & Salovey, Reference Mayer and Salovey1997): SA=self-awareness; SM=self-management; OA=other-awareness; OM=other-management. Collaboration was measured by the 9-item Team Collaboration Questionnaire, an original measure of collaborative activity among teams, adapted from Aram and Morgan (Reference Aram and Morgan1976) and Rahim (Reference Rahim1983a, Reference Rahim1983b), that measured three factors: IN=integration; CP=compromise; CM=communication. SOAR was measured by 12 items from the SOAR Profile (Cole & Stavros, Reference Cole and Stavros2013, Reference Cole and Stavros2014), a self-report measure of SOAR-based strategic thinking in the four elements of SOAR: ST=strengths; OP=opportunities; AS=aspirations; RE=results. Participants rated both the emotional intelligence and the collaboration items using a 7-point Likert scale (1=‘strongly disagree,’ to 7=‘strongly agree’) and rated items on the SOAR Profile using a 10-point Likert scale (1=‘never,’ to 10=‘always’). Prior to data analysis, scores along the 7-point Likert scale were rescaled to a 10-point Likert scale using the following rescaling method outlined by Dawes (Reference Dawes2008): 1=1.0, 2=2.5, 3=4.0, 5=7.0, 6=8.5, and 7=10. Accordingly, all results reflect emotional intelligence, collaboration and SOAR scored along a 10-point Likert scale.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and general linear modeling-based inferential statistics were conducted in Minitab version 16.2.1; confirmatory factory analysis and mediation path models via structural equation modeling were conducted in Mplus version 7. For each statistical procedure, all available data were used. For all inferential statistics, significance was evaluated at the 95% confidence level, two-tailed tests.

Psychometric properties

The psychometric properties of the WEIP-S, the Team Collaboration Questionnaire and the SOAR Profile were evaluated via Cronbach’s coefficient α test of internal consistency reliability (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951) and confirmatory factory analysis test of construct validity (Lu, Reference Lu2006). Cronbach’s α values of 0.7 or higher served as a reference for acceptable reliability (Hinkin, Reference Hinkin1998). In evaluating construct validity using confirmatory factory analysis, the comparative fit index, root mean square error of approximation, and the ratio of χ2 to the df were examined. Comparative fit index values of at least 0.90, root mean square error of approximation <0.08, and χ2/df ratio <2–1 were indicative of acceptable construct validity (Bentler, Reference Bentler1990; Loehlin, Reference Loehlin1998; Bentler, Reference Bentler2007).

Inferential statistics

Hypothesis testing of Hypotheses 1a and 1b were carried out using hierarchical linear regression of collaboration regressed on emotional intelligence, team type, and an emotional intelligence×team type interaction term. In the regression analysis, age, ethnicity, and education were included as control variables due to their significant distribution in the sample (see Table 2). Hypothesis testing of Hypothesis 2 was conducted using a mediation path model with structural equation modeling to determine if SOAR mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration; a bootstrapped confidence interval for the indirect effect was obtained using procedures described by Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2008).

Table 2 Characteristics of sample by gender, age, ethnicity, education, and team type

Note. Sample frequency is expressed as % of all participants, N=308.

*p<.01; χ2 test for equality of distribution.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the sample

Table 2 reports the demographic characteristics of the sample comprised of frequency analysis and χ2 tests for equality of distribution. The sample (N=308) was essentially equally distributed among males and females. In contrast, age, ethnicity, and education were significantly distributed, with the majority of participants 45–64 years of age (52%), white (77%), and with a graduate education (70%). The majority of participants (62%) reported working in face-to-face teams, and ~38% reported working in virtual teams.

Psychometric properties and intercorrelations between study variables

Table 3 presents Cronbach’s α values for each study variable scale; Table 3 also presents the intercorrelations between the study variables and their constitutive factors. As shown, Cronbach’s α values were all acceptable for internal consistency reliability with values ranging from 0.721 to 0.909 for 13/14 scales. Additionally, tests of model fit for confirmatory factory analysis were supportive of construct validity (see Figure 3). These results support the use of composite variables for emotional intelligence, SOAR and collaboration in tests of Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 2. The intercorrelations between the three study variables (and their constitutive factors) show strong and significant correlations among the study variables. For example, correlations between emotional intelligence and its factors range from 0.66 to 0.79. Collaboration and its factors show correlations between 0.78 and 0.82, and SOAR is correlated with its factors from 0.69 to 0.80.

Figure 3 Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of SOAR (strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results) mediating the impact of emotional intelligence (EI) on team-based collaboration (COL) Note. Figure 1 also shows team type (virtual vs. face-to-face vs. both) as a moderator of the EI–COL relationship. Goodness of fit indices are from the CFA; all factor loadings from the CFA are significant at p<.01. AS=aspirations; CFI=comparative fit index; CI=confidence interval; CM=communication; CP=compromise; DV=dependent variable; IN=integration; IV=independent variable; MED=mediating variable; MOD=moderating variable; OA=other-awareness; OM=other-management; OP=opportunities; RE=results; RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation; SA=self-awareness; SM=self-management; ST=strengths.

Table 3 Intercorrelations between study variables

Note. All study variables reflect measurement along a 10-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s coefficient α for each scale is presented along the diagonal.

AS=aspirations; CM=communication; CO=collaboration; CP=compromise; EI=emotional intelligence; IN=integration; M=mean; OA=other-awareness; OM=other-management; OP=opportunities; RE=results; SA=self-awareness; SM=self-management; SOAR=strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results; ST=strengths.

*p<.05; Pearson’s product-moment correlation.

Inferential statistics

Results for Hypothesis 1a

In support of Hypothesis 1a, the regression of collaboration on emotional intelligence (controlling for age, ethnicity, and education) was significant (see Table 4, Steps 1 and 2). Results found an unstandardized β=0.476, p<.01 for emotional intelligence as a predictor of collaboration. These results suggest emotional intelligence in team members may have a positive effect on collaboration such that, along 10-point Likert scale, each unit increase in emotional intelligence is predicted to increase collaboration among team members by ~0.5 Likert scale units. Emotional intelligence was found to account for almost 25% of the variance in collaboration.

Table 4 Team type as a moderator of the emotional intelligence–collaboration relationship (controlling for age, ethnicity, and education)

Note. See text for coding of variables. Team type was coded 1=face-to-face, 0=virtual.

*p<.01; regression coefficient, change in R 2.

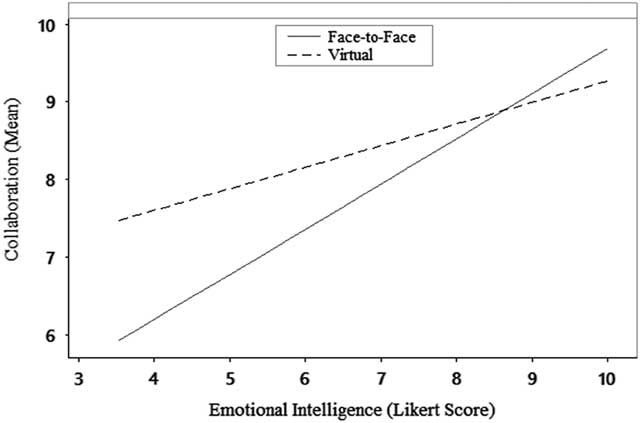

Results for Hypothesis 1b

In support of Hypothesis 1b, the regression of collaboration on the emotional intelligence×team type interaction (controlling for age, ethnicity, and education) was significant (see Table 4, Steps 3 and 4). Results found a significant slope for the interaction term (unstandardized β=0.352, p<.01). The significant increase in R 2 from Step3 to Step 4 (change in R 2 =3.1%, p<.01) suggests participants’ team type (face-to-face vs. virtual) was a moderator of the emotional intelligence–collaboration relationship. As shown in Figure 4, the slope of the emotional intelligence–collaboration relationship for face-to-face and virtual teams is positive; however, the slope is steeper for face-to-face teams than virtual teams. Additionally, mean (SD) emotional intelligence for participants working in face-to-face versus virtual teams=7.42 (1.22) versus 6.80 (1.37), respectively; mean (SD) collaboration for participants working in face-to-face versus virtual teams=8.20 (1.19) versus 8.29 (1.06), respectively. Although the mean scores for emotional intelligence and collaboration were not found to be significantly different according to results of an independent samples T-test (data not shown), the higher emotional intelligence in face-to-face team members compared with virtual team members may have contributed to the finding that emotional intelligence appears to be a stronger positive predictor of collaboration in face-to-face teams compared with virtual teams.

Figure 4 Team type as a moderator of the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration

Results for Hypothesis 2

In support of Hypothesis 2, a significant indirect effect was found between emotional intelligence and collaboration via SOAR (β=0.110, Z=2.444) (see Table 5 and Figure 4). Also in support of Hypothesis 2, a significant indirect effect was found between emotional intelligence and collaboration via three of the four SOAR elements: Strengths (β=0.049, Z=1.966), Aspirations (β=−0.050, Z=2.151), and Results (β=0.043, Z=2.655) (see Table 6 and Figure 5). Taken together, results of the mediation analyses suggest that as SOAR, strengths and results increase, and as aspirations decrease, emotional intelligence has a significant positive effect on collaboration. The finding of a significant mediated path and a significant direct c' path in both mediation analyses suggests the influence of emotional intelligence on collaboration is partially mediated by SOAR. Therefore, emotional intelligence may have some additional effect on collaboration that is not mediated by SOAR (Cheung & Lau, Reference Cheung and Lau2008) (Figure 6).

Figure 5 Test of SOAR (strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results) as a mediator of the emotional intelligence–collaboration relationship Note. DV=dependent variable; IV=independent variable; MED=mediating variable.

Figure 6 Test of strengths (STR), opportunities (OPP), aspirations (ASP), and results (RES) as multiple mediators of the emotional intelligence–collaboration relationship Note. DV=dependent variable; IV=independent variable; MED=mediating variable.

Table 5 SOAR as mediator of the emotional intelligence–collaboration relationship

Note.

a Bootstrap confidence intervals (95%).

b Bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap confidence intervals (95%).

EI=emotional intelligence; IV=independent variable; MED=mediating variable; SOAR=strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results.

*p<.05, **p<.01; 5,000 bootstrapping samples.

Table 6 SOAR elements as multiple mediators of the emotional intelligence–collaboration relationship

Note.

a Bootstrap confidence intervals (95%).

b Bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap confidence intervals (95%).

EI=emotional intelligence; IV=independent variable; MED=mediating variable; SOAR=strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results.

*p<.05, **p<.01; 5,000 bootstrapping samples.

DISCUSSION

Emotional intelligence is an important factor in team performance among face-to-face teams and virtual teams (Druskat & Wolff, Reference Druskat and Wolff2001; George, Reference George2002; Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, Reference Goleman, Boyatzis and McKee2002; Jordan & Lawrence, Reference Jordan and Lawrence2009; Pitts, Wright, & Harkabus, Reference Pitts, Wright and Harkabus2012; Gera, Reference Gera2013). Applied to teams and team members, the SOAR framework of dialogue-based strategic thinking emphasizing strengths, opportunities, aspirations and results is closely linked to emotional intelligence abilities (Stavros & Wooten, Reference Stavros and Wooten2012; Stavros & Cole, Reference Stavros and Cole2015). Emotional intelligence–SOAR relationships are exemplified in self-reflection, mutual understanding, and a consideration for the collaborative group as a whole (Cole & Stavros, Reference Cole and Stavros2016).

Results of linear regression conducted on survey data obtained from 308 professionals actively working in teams found increases in emotional intelligence among team members is predicted to increase team member collaboration. Regression analyses also found emotional intelligence appears to be a stronger positive predictor of collaboration in team members working in face-to-face teams compared with team members working in virtual teams. Results of structural equation modeling-based mediation path analysis found SOAR partially mediates the effect that emotional intelligence has on collaboration, with the SOAR elements of strengths, aspirations, and results serving as partial multiple mediators.

Implications for practice and recommendations

This study has implications for teams and team members, with recommendations to improve emotional intelligence abilities and apply the SOAR framework in teams and team members in order to increase collaboration that may ultimately increase team performance (Melita Prati et al., Reference Melita Prati, Douglas, Ferris, Ammeter and Buckley2003; Xavier, Reference Xavier2005; Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis2007; Cameron, Reference Cameron2013; Cole & Stavros, Reference Cole and Stavros2016).

Research by Mount (Reference Mount2006) supports the role of emotional intelligence to differentiate international capability through teamwork and cooperation, and uncovers the need for organizations to create and sustain emotional intelligence competencies in the complex environment of international business. The culture of international business is emotional: our emotions influence our perceptions and how we interpret and respond to others.

Emotional intelligence addresses several common business issues that managers, executives, practitioners, and consultants face on a daily basis. Research by Sala (Reference Sala2006) links emotional intelligence competency behaviors and workplace performance across common industries, organizations, and cultures. For example, emotional intelligence competencies of awareness and management of emotions in self and others positively impacts team-based collaboration as team members articulate a compelling vision, recognize specific strengths of others, remain positive despite setbacks, and initiate actions to create possibilities.

As noted by Romero, Galeano, and Molina (Reference Romero, Galeano and Molina2008), collaboration implies that team members are working together to accomplish an outcome that is more significant as a team than that which could be accomplished by the individual members acting alone. Study results of testing Hypotheses 1a and 1b suggest collaborative factors of integration, compromise, and communication in professional working in face-to-face and virtual teams are influenced by awareness and management of emotions in self and others. The significance of this implication is important to collaborative teams seeking to gain a competitive advantage within some framework of time, cost, and performance. For example, teams that use emotional intelligence have an advantage in collaboration over teams lacking in emotional intelligence due to team members’ developing awareness and management of emotions in themselves and others (Gohm, Reference Gohm2004).

Organizational leaders and practitioner consultants concerned with increasing team-based collaboration are recommended to increase emotional intelligence abilities in themselves and their collaborative teams. Utilizing a coaching-based approach to train emotional intelligence, leaders and consultants are recommended to help members of face-to-face and virtual teams develop self-awareness, regulate emotions, recognize emotions in others, identify team-based biases and hot button issues, and resolve conflicts in diverse settings (Gardenswartz, Cherbosque, & Rowe, Reference Gardenswartz, Cherbosque and Rowe2009). Coaching that engages team members in discussions, exercises, dialogue, role play, diaries, and one-to-one feedback should be used to train emotional intelligence (Dulewicz & Higgs, Reference Dulewicz and Higgs2004).

Study results found SOAR partially mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration among team members. At the heart of the SOAR framework is an inclusive approach that promotes team members to frame strategy from a strengths-based perspective utilizing the team’s unique strengths, assets, and capabilities (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, Reference Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros2008). The implication of Hypothesis 2 being supported is that SOAR, as a framework for strategy based on the strengths and aspirations of team members, opportunities for team success, and attention to measurable team results, helps to explain how emotional intelligence leads to positive collaboration. Accordingly, SOAR should be considered when seeking to improve collaboration in teams. This implies further that emotional intelligence abilities and their effect on collaboration can be accentuated in individuals and teams competent in SOAR.

Enabling strategic thinking capacity from a SOAR-based framework in team members may provide the best opportunity for emotional intelligence to influence collaboration. Leaders can assemble teams that build on strengths and aspirations of members to identify opportunities and achieve positive results. This positive approach may lead to effective changes in the organization based on images of the best possible future as articulated and visualized by the people who make up the human system of the organization (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, Reference Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros2008). When individuals are working in a team context, especially when collaboration is the desired outcome, team members competent in SOAR will be able to maximize the impact emotional intelligence has on collaboration.

We believe that teams comprised of multicultural members will be more effective if the team members utilize a strategic thinking and planning framework that focuses on generativity (Cole & Stavros, Reference Cole and Stavros2016). Such a strategic thinking and planning framework occurs when teams build capacity from a SOAR-based perspective. SOAR creates a reservoir of positivity, generative action, new ideas, innovations, and the best in people to emerge (Stavros & Hinrichs, Reference Stavros and Hinrichs2009; Stavros & Wooten, Reference Stavros and Wooten2012; Bushe, Reference Bushe2013; Stavros, Reference Stavros2013). Since 1999, SOAR has been used by thousands of organizations on an international basis (Stavros, Reference Stavros2013). A summary listing of types of organizations and locations where SOAR has been applied is presented in Table 7.

Table 7 SOAR’s global growth

Note. SOAR=strengths, opportunities, aspirations, results.

Source. Adapted from Stavros (Reference Stavros2013).

We also believe that teams have interrelated and interdependent parts that make up the whole team. To be highly effective, team members must have the ability to self-correct, and a whole systems perspective indicative of SOAR, AI, and positive organizational scholarship can help team members perceive the team as a complete system in which even small behaviors or changes are generative. Systems thinking in which the team is conceptualized as a learning organization impacted by feedback loops and holistic analysis will help the team make effective decisions (Senge, Reference Senge2006). To increase systems in teams, team members are recommended to utilize the SOAR framework for engaging in a strategic thinking and dialogue process to help shape effective decisions (Cole & Stavros, Reference Cole and Stavros2016). Education and training in the SOAR competencies may be the best approach for team members unfamiliar with SOAR and strengths-based strategic thinking.

Organizational leaders and practitioner consultants are recommended to increase SOAR-based strategic thinking in team members. Utilizing the same coaching-based approach to train emotional intelligence, leaders and consultants are recommended to invite team members from face-to-face and virtual teams to have an open conversation about the strengths of the team climate (‘What is working well for the team?’), ideas for creative solutions or innovations (‘What can team members create together?’), and current possibilities that would benefit from collaboration (‘What do collaborative possibilities among team members look like?’). Next, the SOAR architecture of strengths, opportunities, aspirations and results should be followed to facilitate positive collaborative engagement among team members (Cole & Stavros, Reference Cole and Stavros2016). For example, team members should be invited to engage in a collaborative and inclusive conversation on any individual, team, and/or organizational strengths as they relate to possibilities for solutions or innovations (‘What are the team strengths as they relate to these possibilities?’), opportunities that would benefit from solutions or innovations (‘What opportunities appear for the team?’), aspirations of a future each team member desires for self, others, and the team (‘What vision of the future do I have for myself, for my teammates and for the team?’), and measurable results indicating progress toward a goal or objective that the team member wants to complete (‘What are we trying to achieve?’).

Study limitations and future directions

This study has limitations with respect to the data. First, this study invited participants to provide self-assessment about individual behavior within the context of the team currently involved with. Thus, the unit of analysis was the individual team member. In recognition of the individual team member as the unit of analysis, future research should use the team as the unit of analysis. A second potential of the study data concerns common method bias which may occur when self-report data for the independent variable comes from the same self-report source as the dependent variable. Using techniques described by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), Harman’s single factor test was conducted – results suggest that common method bias did not occur in the study data. Specifically, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the items that measured emotional intelligence and team collaboration, and eigenvalues were found indicative of a multifactorial result. Future research should investigate other methods of emotional intelligence assessment which are not self-report (e.g., 360° assessment instruments, interviews, and other qualitative approaches, etc.). Future research should also measure collaboration among team members by using independent observers. For example, a 360 approach to assess collaboration will provide responses from team leaders, team members, stakeholders, etc. (Toegel & Conger, Reference Toegel and Conger2003).

Regarding emotional intelligence, future research should explore whether some team members use emotional intelligence to manipulate others. For example, the emotional intelligence ability to manage the emotions of others may be used ineffectively or inappropriately for extending one’s agenda over others (Furnham & Rosen, Reference Furnham and Rosen2016). Inappropriate use and application of emotional intelligence abilities would likely come at the expense of the team, potentially failing the keys to positive collaboration (i.e., integration, compromise, and communication). Assessing team member vies on manipulation and its potential impact on collaboration may prove an important area of research.

Another potential limitation in this study is the finding that SOAR was a partial mediator of the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration. The implication of partial mediation is that SOAR-based strategic thinking and planning may be only one of many mechanisms for how emotional intelligence impacts collaboration. For practitioners, identifying additional mediating variables may provide even greater opportunity to maximize the positive impact emotional intelligence has on collaboration. Future research should seek to clarify the distinction between partial and full mediation of SOAR in order to determine if there are other variables that may help to explain how emotional intelligence has a positive effect on collaboration.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the present study support our hypotheses that emotional intelligence is a significant positive predictor of collaboration in team members, and team type moderates, and SOAR partially mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and collaboration. These findings increase our understanding that SOAR, as a generative and strengths-based approach to strategic thinking, planning, and leading, may play an important role in helping both face-to-face and virtual teams increase their collaboration via emotional intelligence. The positive effects of emotional intelligence on team performance are seen when team members experience other team members’ emotions and subsequently gain knowledge and awareness of their own behavior and the emotions that influence successful team behavior, such as, improved emotional regulation during stressful episodes (Jordan & Ashkanasy, Reference Jordan and Ashkanasy2006). Thus, the interaction between team members, the working relationships established in the team, team diversity, and the organizational culture of the team allow the team as a whole to perform at a higher level than the team members would perform alone (Simons, Pelled, & Smith, Reference Simons, Pelled and Smith1999). With continued practice that grows individual emotional intelligence as mediated by the generative and whole systems nature of SOAR, the team will be transformed as a new whole that contains the best of each team member.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the paper. This manuscript is an original work that has not been submitted to nor published anywhere else.

All authors have read and approved the paper and have met the criteria for authorship.