Introduction

Modern investigation of relations between the Late Bronze Age Pharaonic state and the pastoralists who inhabited the Western Desert (commonly referred to as ‘Libyans’; Snape Reference Snape, O'Connor and Quirke2003) has suffered from a near absence of archaeological and textual material produced by these semi-nomadic societies themselves. This, in turn, has prompted scholars to rely on Egyptian textual and iconographic sources to inform about Libyan culture and Egypto-Libyan relations. This enforced focus initially resulted in scholarly dismissals of Late Bronze Age Libyans as culturally inferior to their Egyptian neighbours (Bates Reference Bates1914; Hölscher Reference Hölscher1955). Later researchers attempted to reconstruct Libyan society and political divisions on the shaky foundation of subjective source material, such as depictions of Libyans in Egyptian royal and private monumental architecture (O'Connor Reference O'Connor and Leahy1990 contra Ritner Reference Ritner and Szuchman2009). Attempts to identify settlements of Late Bronze Age Libyans in the archaeological record have been inconclusive, aside from limited evidence of occupation from Bates’ Island and Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. The latter is an Egyptian fortress located 320km west of Alexandria (Carter Reference Carter1963; Hounsell Reference Hounsell2002; Simpson Reference Simpson2002; White Reference White2002).

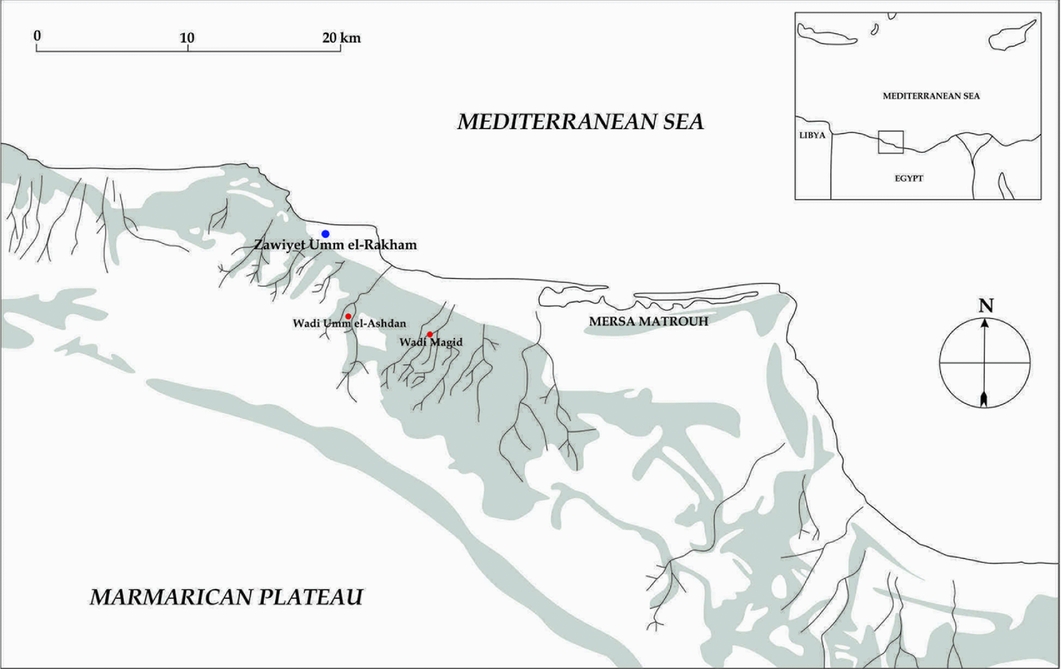

Founded during the reign of Ramesses II and occupied for only a brief period of around 50 years, the fortress of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham (Figures 1–2) has been explored by successive missions, initially led by Alan Rowe in 1946, by Labib Habachi in 1949 and from 1953–1955, and since 1994 by a University of Liverpool mission under the direction of Steven Snape (Rowe Reference Rowe1953, Reference Rowe1954; Leclant Reference Leclant1954, Reference Leclant1955, Reference Leclant1956; Habachi Reference Habachi1980; Snape Reference Snape and Eyre1998, Reference Snape, O'Connor and Quirke2003, Reference Snape2004, Reference Snape, Bietak, Czerny and Forstner-Müller2010, Reference Snape, Förster and Riemer2013; Snape & Wilson Reference Snape and Wilson2007).

Figure 1. Map of the Marmarican coast west of Mersa Matrouh, showing the location of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham and nearby remains of modern embanked fields at Wadi Magid and Wadi Umm el-Ashdan (map by N. Nielsen).

Figure 2. Plan of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham showing the location of the areas under archaeological exploration (S. Snape).

The fortress was surrounded by a mud-brick enclosure wall and housed a temple and a series of private chapels, as well as domestic areas (K and N), storage magazines and granaries (Simpson Reference Simpson2002; Snape & Wilson Reference Snape and Wilson2007). Simpson (Reference Simpson2002) suggests that substantial quantities of ostrich eggs were bartered by local tribes to the Egyptian occupants, possibly in exchange for metal objects, a topic also examined by Hulin (Reference Hulin, Duistermaat and Regulski2011) in relation to evidence of Late Bronze Age metallurgy on Bates' Island. Recent research has focused on the archaeological material found in the site's provisioning zone, area K (Figure 3; Snape 2010; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2016a & Reference Nielsenb; Gasperini Reference Gasperini and Franzmeier2017), including a large assemblage of objects related to the procurement and processing of cereal products. The investigation of this material—in conjunction with textual data from the site—presents a unique source of further information concerning interactions between this sedentary Egyptian enclave and nearby Libyan nomads during the brief occupation of the fort. Complementing this evidence are cross-cultural data concerning nomad-sedentary relations in the Near East and North Africa.

Figure 3. View over the domestic structures in area K, looking south (photograph S. Thomas).

Cereal cultivation and processing at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham

Herodotus claimed that the “eastern region of Libya, where the nomads live, is low-lying, sandy flat land up to the Triton River” (Herodotus 4.191, Strassler Reference Strassler2009: 359), and, therefore, that the nomadic occupants of eastern Libya were sustained entirely by milk and the flesh of their animals (Herodotus IV: 186, Strassler Reference Strassler2009: 358). This claim has, in recent years, been challenged by a number of surveys of the eastern Marmarica region between Mersa Matrouh and Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham (White Reference White, Betancourt, Karageorghis, Laffineur and Niemeier1999: 932; Hulin Reference Hulin2001: 74; Vetter et al. Reference Vetter, Rieger and Nicolay2009, Reference Vetter, Rieger, Möller, Förster and Riemer2013, Reference Vetter, Rieger and Nicolay2014; Rieger et al. Reference Rieger, Vetter, Möller, Barnard and Duistermaat2012). These surveys have helped to create a more nuanced picture of the agricultural potential of the coastal zone and the many wadis that bisect the area. Papyrus Vatican II from the Marmarica region, which dates to the second century AD, lists barley as the predominant cereal, alongside smaller amounts of wheat and beans, vines, olives, figs and dates grown in the area (Johnson Reference Johnson1959: 58–62). Several of these crops, such as barley, olives and figs, remain local staples today (Figure 4). Complementing this textual evidence are a series of Ptolemaic settlements identified in the area south of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham at Wadi Umm el-Ashdan, Wadi Qasaba and Wadi Magid, as well as a widespread network of cisterns, embanked fields and other evidence of ‘water harvesting’ dating mostly to Classical antiquity, spread throughout the surveyed area (Rieger et al. Reference Rieger, Vetter, Möller, Barnard and Duistermaat2012: 166–68; Vetter et al. Reference Vetter, Rieger, Möller, Förster and Riemer2013: fig. 13, Reference Vetter, Rieger and Nicolay2014: 50–53).

Figure 4. View of modern agriculture in wadis to the south of the site, looking south (photograph by S. Snape).

A group of these water-harvesting structures discovered at Wadi Magid, located 8km south-east of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, were dated using optically stimulated luminescence to between 1193 and 1153 BC, making them broadly contemporaneous with the Egyptian occupation at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2011; Rieger et al. Reference Rieger, Vetter, Möller, Barnard and Duistermaat2012: 167). Similar dating methods used at embanked fields in Wadi Umm el-Ashdan, located 2km south of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, provided dates ranging from the First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BC) through to the Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BC) (Rieger et al. Reference Rieger, Vetter, Möller, Barnard and Duistermaat2012: 167). Ceramic surveys conducted by Linda Hulin (Reference Hulin2001: 68) revealed concentrations of Egyptian and Egyptian-style Ramesside pottery in the wadis south of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, close to the areas discussed above. The presence of Egyptian material and Late Bronze Age water-harvesting structures south of the fortress suggests that the Egyptian occupants of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham exploited these fertile zones for agricultural purposes. What is less clear is how Egyptians from the Nile Valley, with an inundation-based agricultural system, acquired the technological expertise and local knowledge of hydrological conditions to irrigate the soil effectively (Rieger et al. Reference Rieger, Vetter, Möller, Barnard and Duistermaat2012: 168).

From the OSL dates provided by Rieger et al. (Reference Rieger, Vetter, Möller, Barnard and Duistermaat2012: 167–68), it is clear that farming in this area pre-dates the Egyptian occupation by several hundred years, from at least the Middle Kingdom onwards. Ethnographic evidence from the Cyrenaica region of Libya highlights the importance of seasonal agriculture conducted by nomadic tribes, a practice that was also described in detail by pre-industrial travellers to the region (Lyon Reference Lyon1821: 44; Behnke Reference Behnke1980: 40–48; Cribb Reference Cribb1991). Similar opportunistic agriculture was probably conducted by the Marmarican nomads during Pharaonic times as a means of supplementing a diet based around herd animals. Such agricultural pursuits would have required knowledge of the hydrological conditions in the eastern Marmarica region; it is therefore possible that the Egyptian occupants at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham relied on information and aid from local nomads familiar with this type of agriculture to farm the wadis to the south of the fort effectively. It is in this context that the following passage from the biography of Nebre, the commander of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, should be viewed:

He made [the Libyans] masters/possessors of settlements, so that they would plant trees; so that they would work many vineyards and [///] in the countryside (Snape & Godenho in press).

The primary archaeological evidence from Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham for the harvesting of cereal products consists of assemblages of flint sickle blades (Figure 5) found in area K, along with a far larger quantity in the magazines located north of the fort's temple (Simpson Reference Simpson2002: 326–27). Storage facilities in the form of three circular granaries (area H) built immediately adjacent to area K were excavated at the site in 2001 (Simpson Reference Simpson2002). Tools for processing cereal products into flour are among the most common small finds recorded from area K, with 36 saddle querns made from the local biosparite limestone, and 22 handstones made from either local limestone or, more commonly, from imported hard stones, such as quartzite and granite. Fifteen domed bread ovens of similar form and size to New Kingdom examples from Deir el-Medina, the Workmen's Village at Tell el-Amarna, and Amara West were also excavated in area K (Bruyère 1937–Reference Bruyère1939: 72–74; Samuel Reference Samuel1999, Reference Samuel, Nicholson and Shaw2000: 566; Spencer Reference Spencer and Müller2015). Only six were found complete, while the remainder showed signs of deliberate removal, probably as the structural layout of the area was changed (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2016b: 55–91).

Figure 5. Examples of tools (a quern, handstone and sickle blades) for processing cereal products found in area K (photographs by S. Snape & N. Nielsen).

Several factors would have determined the extent of land required for cultivation to feed the occupants at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham: population size, calorific requirements and yields for barley and emmer wheat. Using inscriptional evidence found at the site, Snape and Wilson (Reference Snape and Wilson2007: 128) proposed a population of 500 people. An alternative methodology for calculating population size is the dwelling-based estimate championed by Zorn (Reference Zorn1994). With eight excavated dwellings in areas N and K (representing 16 per cent of the fortified enclosure), and an estimated five occupants on average per dwelling (Zorn Reference Zorn1994: 33), a population of approximately 230 is suggested. This is similar to the number of occupants estimated for the Ramesside fort at Amara West (Spencer Reference Spencer, Welsby and Anderson2014: 460). While cereal crops were crucial to the ancient Egyptian diet, other plants (pulses and legumes, for example) provided a portion of daily calorific requirements, as did protein from meat and dairy. On the basis of archaeobotanical and ethnographic data, Padgham (Reference Padgham2014: 21) estimates that cereals (emmer wheat and barley) provided 72.7 per cent of the annual calorific intake of New Kingdom Egyptians, with 55.6 per cent coming from barley bread and barley beer, and 17.1 per cent from emmer bread. With an estimated population of 230, Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham would require 230kg/yr of barley and 56kg/yr of emmer wheat per person. When an additional 10 per cent of the harvest for seed corn and 15 per cent covering loss and wastage are included, this provides a total annual requirement of 66125kg/yr of barley and 16100kg/yr of emmer wheat to supply the occupants at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham.

Using an extensive ground and satellite survey of a 30km east–west by 15km north–south area of land south of Mersa Matrouh, Vetter et al. (Reference Vetter, Rieger and Nicolay2009: 20) concluded that roughly 9 per cent (40.5km2) of this area consisted of potentially arable land. At most, that would provide 4050ha of suitable land in the area surrounding Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. Vetter et al. (Reference Vetter, Rieger and Nicolay2009: 20) proposed that assuming a barley yield of 1T/ha, this area could potentially feed 22000 people. Ethnographic data from similar environments in the Levant, however, suggest that a lower yield averaging 646.7kg/ha is a more realistic figure (Padgham Reference Padgham2014: 132). According to Papyrus Vatican II, the area during the second century AD averaged 570kg/ha for barley and 521kg/ha for emmer wheat (Applebaum Reference Applebaum1979: 99–100). Using these lower yield rates, the occupants at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham would have needed to cultivate 147ha (or 3.63 per cent) of the immediately available arable land to maintain the required supply of cereal products for 230 inhabitants. Any additional grain produced as payment for Libyan assistance in the agricultural process should also be considered. The size of such a Libyan community is impossible to determine with any accuracy, given the dearth of archaeological data concerning Late Bronze Age Libyan communities. Assuming a population approximately equal to that of the Egyptian occupants at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, however, the amount of cultivated land required rises to 294ha (or 7.26 per cent) of the immediately available arable land. This number is broadly comparable to the land required (320ha/7.89 per cent) to sustain the highest estimated population number of 500 (Snape & Wilson Reference Snape and Wilson2007: 128).

Even considering the probability that some of the grain consumed at the site was shipped from Egypt (Snape Reference Snape, Förster and Riemer2013), the archaeological evidence from Wadi Magid and Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham combines to show extensive and well-developed cereal cultivation and processing that was capable of sustaining the settlement and mitigating against delays or missing deliveries from Egypt. The knowledge of local climatic conditions and the hydrological constructions involved in the ‘water harvesting’ required for any local agriculture is, however, unlikely to have come from the Egyptian occupants at the site. Rather, the local semi-nomadic communities probably assisted the Egyptian population with creating and maintaining their agricultural regime.

Nomad-sedentary interactions in Marmarica: cross-cultural perspective

Building on the work of Michael Rowton (Reference Rowton1973), modern scholars have recognised that ‘nomadic’ cultures did not exist insulated from sedentary groups, but chose from a spectrum of more or less sedentary strategies, engaging in agriculture, trade and various crafts, when required to supplement their basic pastoral economy (Szuchman Reference Szuchman and Szuchman2009: 3, see too Finkelstein Reference Finkelstein1995: 37–38). Nomad-sedentary interaction between Egypt and its eastern and southern neighbours has been explored extensively, whereas the interaction between Egyptians and Libyans has been studied primarily on a macro-political level, using Egyptian textual and iconographic source material (Ritner Reference Ritner and Szuchman2009; cf. Spalinger Reference Spalinger1979; Osing Reference Osing, Helck and Westendorf1980; Kitchen Reference Kitchen and Leahy1990; O'Connor Reference O'Connor and Leahy1990). Informal economic relations between communities of Libyans and sedentary Egyptians living in the Western Nile Delta and the Kharga oasis have also only recently been examined (García Reference García2014).

By contrast, pastoral nomadism and its interaction with sedentary communities from various periods has been extensively investigated across the Levant (cf. Cribb Reference Cribb1991; Haiman Reference Haiman, Bar-Yosef and Khazanov1992; Rosen Reference Rosen and Szuchman2009). The categorisation of nomad-sedentary relations in Mesopotamia offers a particularly useful case study (Lönnqvist Reference Lönnqvist, Kogan, Koslova, Loesov and Tischenko2010). Juxtaposing textual and archaeological data obtained from excavations in the area of Jebel Bishri, Lönnqvist (Reference Lönnqvist, Kogan, Koslova, Loesov and Tischenko2010: 132–33) identified nine models by which the Mesopotamian states either interacted with, or attempted to control, the nomadic Amorites (known as mar.tu in the Sumerian record) living on the boundaries of their territory. These models could be broadly hostile (e.g. constructing fortifications against nomadic communities, or launching punitive military expeditions against them; using propaganda or magico-religious methods to control or attack desert environments and their occupants; and forced sedentism), or peaceful (e.g. establishing trade and alliances with nomadic communities; using nomads for labour or auxiliary troops; and engaging in reciprocal diplomatic gift giving).

A study of the source material that details Egyptian interactions with Libyan communities throughout the Pharaonic period suggests that similar methods were employed. The most obviously hostile modes deployed by sedentary communities, such as military aggression, are repeatedly evidenced in the Egyptian source material from the Middle Kingdom by Mentuhotep IV and Senwosret I, in the New Kingdom by Amenhotep III (Urk. IV, 1656; Sethe Reference Sethe1961: 1656), and crucially, in the Libyan Campaign of Seti I, conducted shortly before the construction of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham (Sethe Reference Sethe1929: 3–17; Habachi Reference Habachi1963: 21–23, pl. 5; Oriental Institute Epigraphic Survey 1986; KRI I 20:15–24:5; Kitchen Reference Kitchen1993: 15–24). The portrayal of nomadic societies as embodiments of chaos is similarly evidenced in Middle Kingdom literature, such as the Prophecies of Neferty and the Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Lord of All (Helck Reference Helck1970: 55; Enmarch Reference Enmarch2008: 238). The use of magic to control or hurt nomadic communities was also employed during the Middle Kingdom in the form of the Execration Texts, although the inclusion of the Libyans on this list is probably symbolic (Posener Reference Posener1940: 25; Ritner Reference Ritner and Szuchman2009). More-peaceful interactions were also used by the Egyptian state, such as trade and alliance-building and the inclusion of Tjehenu Libyans as an auxiliary military force during both the Old and New Kingdoms (Urk. I, 98–110; Sethe Reference Sethe1933: 98–110; Urk. IV, 373; Sethe Reference Sethe1961: 373; KRI IV, 18:5–18:9; Kitchen Reference Kitchen2003: 18; Davies Reference Davies1905: pl. XXXI; Sagrillo Reference Sagrillo, Galil, Levinson-Gilbo'a, Maeir and Kahn2012: 441).

The issue of sedentarising nomadic communities, either forcibly or by creating economic incentives, is obliquely referenced during the reign of Ramesses II, specifically on an inscribed block from Suez, on which it is claimed that Ramesses pursued a policy of: “[Resettling the] Libyans in settlements bearing his name, Lord of Crowns, Ramesses II” (KRI II, 406:3). Another Ramesside text further describes how the king “settled the Libyans (Tjehenu) on the ridges” (KRI II, 206:18; Kitchen Reference Kitchen1996: 206). The previously mentioned biography of Nebre, the commander of the fort at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, can be added to this data. Nebre describes the fortress as: “The Town of Ramesses II [. . .] which he built for these Libyan people, who had been living on the desert like jackals” (Snape & Godenho in press).

While states have attempted forcibly to settle nomadic communities throughout history, a more peaceful sedentarisation through the creation of economic incentives is similarly well-attested, including in modern times. An example of this is the Egyptian governmental investments in infrastructure and agricultural projects in the Matrouh region in the 1950s and 1960s, which sought to encourage the local Bedouin to shift their economic focus from herding to agriculture (Abou-Zeid Reference Abou-Zeid1959). Writing during this period, Mohamed Awad (Reference Awad1954) noted the differentiation of nomadism among the communities in the Matrouh governorate. Certain groups led an almost entirely nomadic existence, travelling with their herds between the Western oases and the fertile coastal strip, while partially nomadic groupings lived more permanently along the coastal strip, exploiting it for the cultivation of cereal crops, olives and figs. Awad (Reference Awad1954: 249) notes that many of the wholly nomadic communities maintained kinship bonds with more sedentary populations living on agricultural land, whom they visited in order to sell goods and services (such as aid with the harvest) in exchange for agricultural products. Until recent times, a similar relationship existed between nomadic communities and the sedentary population of the Siwa Oasis (Cole & Altorki Reference Cole and Altorki1998: 143).

Archaeologists working at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham observe a similar economic mechanism regarding the excavation of the site. Local Bedouin, who live on a permanent or semi-permanent basis along the fertile coastal strip where they engage in agriculture, have generally been employed as workmen by the Liverpool mission. If a larger workforce is required, they contact their more mobile kinsmen travelling with their herds, who come to the site to work for the duration of the excavation. Hence, the excavation offers a seasonal economic opportunity, not dissimilar to participation in the cultivation or harvesting of agricultural produce.

Conclusion

The evidence discussed above demonstrates the degree to which the Egyptian occupants of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham relied on local agricultural production. This production, by extension, caused a reliance on local Libyan groupings not just for trade, but also for their knowledge of the local environment and effective farming methods. The participation of some of these local Libyans in the agricultural process itself is further suggested by the biography of Nebre. This interpretation also supports the more active role of Libyan pastoralists in their relations both with Egyptians and the Aegeans on Bates’ Island, with regard to metallurgy (proposed by Hulin Reference Hulin, Duistermaat and Regulski2011).

Encouraging the nomadic communities to rely on sedentary products may have been part of a deliberate policy of ‘soft’ sedentarisation—thereby creating a situation wherein the Libyan nomads were partially or wholly reliant on agricultural produce controlled by the Egyptian occupants at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. An integrated buffer zone against other hostile groupings living farther west, such as the Meshwesh and Libu, could equally be created as a result (Snape Reference Snape, O'Connor and Quirke2003). Another consideration may have been the need to foster and maintain local, mutually beneficial alliances to guarantee the survival of the relatively isolated settlement. Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham evidently served multiple functions. Being heavily fortified and prominently built on a wide coastal plain, it served to demonstrate the power of the Egyptian state. The prevalence of Mycenaean and Levantine imports suggests that it also served as a possible harbour for passing merchant ships (Snape Reference Snape and Eyre1998). The settlement should too, however, be viewed as an economic attractor, which incentivised a more sedentary and—from the point of view of the Egyptian occupants—controlled lifestyle of the Libyan pastoralists.

This policy of interaction and mutual cooperation with local communities is also evident at New Kingdom forts in Nubia, such as Amara West (Spencer Reference Spencer, Welsby and Anderson2014). External factors, such as a possible environmental disaster causing a mass migration of Libyans towards the Nile Valley during the reign of Merenptah (1213–1203 BC), the appearance of the Sea People and the general collapse of the Late Bronze Age international network, naturally affected the successful implementation of this policy and resulted in the abandonment of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, most probably around 1208 BC during the early reign of Merenptah.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Steven Snape for advice and guidance. This article is based on research conducted at the University of Liverpool, which was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.